ABSTRACT

The literacy practices enacted in secondary school English classrooms can be influenced by the pressures acting upon teachers and students. Attention can be diverted away from the process of meaning-making when more emphasis is placed upon performance outcomes than on reading processes. This paper argues that digital forms of Interactive Fiction (IF) hold the potential to help teachers and students attend more closely to the process of meaning-making. It also argues that IF’s component parts – passages, choices and links – render it a useful resource for the scaffolding of classroom dialogue. By considering the different ways that IF could influence the choices that individuals make in the classroom, this paper suggests that works of IF could enable teachers and students to engage with texts differently, improving the literacy practices of the students involved.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Walking down a first-floor corridor of the secondary academy where I work, I glance repeatedly through glass walls and into the English classrooms on my right-hand side. In each room between twenty and thirty students sit in rows, facing forwards. A teacher stands at the front. Sometimes, I see students reading from books or from printed resources. However, in every classroom I pass, I notice that the teacher is projecting presentation slides onto the board at the front of the room. These slides feature prescribed lesson objectives, information, images, questions, tasks, model answers and success criteria. Often, identical presentation slides will be used simultaneously in multiple classrooms. All of the lessons I pass progress in linear and predictable ways. By the end of each lesson, I know that students will have engaged to varying degrees with the content and ideas that each teacher chose to share with their class prior to the lesson’s commencement. The teachers are in control.

What does this situation tell us about the literacy practices that we as teachers are enabling our students to adopt? By changing the ‘digital artefacts’ (Hennessy Citation2011) that we project onto the boards of our classrooms, what teaching and learning choices might individuals be nudged towards making, and how might this change the learning that takes place? In particular, how could works of Interactive Fiction (IF) transform classroom literacy practices?

In this article I explore such questions because I have come to see highly predictable, linear English lessons as problematic. If all English lessons are structured in entirely predictable ways, the space for students to make their own choices about meaning can be limited. It can become easier for students to accept the manufactured interpretations their teachers offer than to attempt making reasonable choices about meaning for themselves. In this context, a ‘manufactured’ interpretation refers to one that ‘is imposed on a student’ (Giovanelli and Mason Citation2015, 42). When students do not learn to make meaning from language themselves, replicating instead the interpretations of their teachers, they do not necessarily practice or demonstrate literacy skills that will benefit them beyond the classroom. By focusing all lessons on extracts, quotations, characters, questions and interpretations that are selected exclusively by the teacher, we arguably provide students with few opportunities to make meaning for themselves.

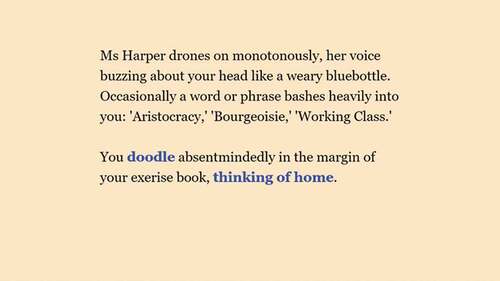

In my opinion, it is possible that collaboratively reading works of IF could help students gain more first-hand experience of meaning-making, helping them develop empowering literacy practices. Imagine, as an example, a class of students collaboratively making meaning from a work of IF that is being projected onto the board. Guided by their teacher, the class discuss potential meanings of a passage (such as the passage displayed in ) before collaboratively deciding which of the available links they want to select in order to progress the narrative. The trajectory of such a lesson is defined, at least in part, by the deliberative choices of the class and not exclusively by the intentions and interpretations of the teacher.

Figure 1. The opening passage from The Doodle (Holdstock Citation2020)

Before continuing, I must clarify what I am referring to when I use the term IF. I subscribe to an open definition of what IF can be: Adapting the words of Maher, I define IF as ‘any form of storytelling which involves the reader or listener’ as a digitally ‘active participant’ (Maher Citation2011). I insert the word ‘digitally’ because I am focusing on works of IF that are read via an electronic device and which are dependent upon digital forms of interaction, usually enacted using a computer mouse or keyboard. Such forms of interaction foreground the active nature of meaning-making because each physically enacted choice transforms the reading experience, changing the quality of the participant’s engagement and highlighting the significance of choice. The financial accessibility of Twine® (a free tool used to create hypertext or Choose-Your-Own-Adventure forms of IF) and its inviting ease-of-use (Kopas Citation2015) have caused me to focus my attentions specifically on works of IF created using Twine®.Footnote1

If such works of IF foreground the active nature of meaning-making, why have I never seen them used in the classrooms of my English-teaching colleagues? One explanation lies in the risk-averse nature of academy cultures. Academies – publicly funded schools that are run by private companies – function in a competitive education marketplace and are not maintained by local authorities. They must therefore manage threats to their own funding, performance and admissions numbers. This can be done by attempting to avoid risky practices. The attempted ‘eradication of risk’ (Biesta Citation2016, 146) can result in an educational environment that allows little space for students and teachers to make and discuss their own choices. By attempting to allay the risk of poor future performance outcomes, academies can shape classroom choices. In turn, the attitudes and literacy practices being adopted in the English classroom can, I argue, be negatively influenced.

Choices in the English classroom

Halliday writes that ‘all human activity involves choice: doing this rather than doing that. Semiotic activity involves semiotic choice: meaning this rather than meaning that’ (Halliday Citation2013, 15). This would suggest that literacy is dependent upon an individual’s ability to make appropriate choices about meaning and expression. By extension, it implies that English teachers should regularly attend to the quality of their students’ semiotic choices. Looking at language from this perspective, an effective communicator might be described as an effective ‘choice architect’ (Thaler, Sunstein, and Balz Citation2013, 428) – one who uses language to ‘nudge’ others towards making particular choices about meaning (Thaler and Sunstein Citation2009). I use the term nudge here to mean ‘initiatives that steer people in particular directions but that also allow them to go their own way’ (Sunstein Citation2017, 61). A critically literate reader will be able to recognise, respect, reject and interrogate the semiotic nudges they encounter.

In this section I shall use the temporal framework for analysing agency put forward by Emirbayer and Mische (Citation1998) to explore the ways that academies such as the one in which I work can influence the choices that teachers and students make in the classroom. By considering the avenues of reflection, projection and choice that are made salient in an academy classroom situation, I shall attempt to identify how teachers and students can be nudged towards or away from certain modes of engagement in the classroom. I use the word mode in a similar way to Wells, who argues that the epistemic mode of textual engagement (viewing texts as ‘tentative, provisional, and open to alternative interpretations and to revision’), gives rise to the most empowering forms of literacy (Wells Citation1990, 369).

Firstly, the reflective element of a teacher’s choice-making process can be influenced by the prioritisation of evidence-based practice over forms of reflection that are more ‘attentive to local circumstance’ (Yandell Citation2019, 434). By emphasising the role of evidence, schools can nudge teachers towards replicating decisions that have worked for others in the past (Biesta Citation2007). This can leave them less open to allowing students to transform the course of the lesson by making their own choices about a text’s meaning. Similarly, many students can find that their personal ‘funds of knowledge’ (Moll et al. Citation1992, 132; Thomson and Hall Citation2008, 87) are discounted and that they are only able to draw upon a limited range of past experiences. This can serve to narrow the range of meaning-making choices available to them because they feel unable to explain their interpretations in terms of their own past experiences. For example, Kulz identifies the ways that ‘middle-class cultural capital is privileged’ in one inner-city academy environment (Citation2018, 6) and how academic success is associated with ‘acting white’ (98). Such a learning environment might not encourage all students to draw upon their own funds of knowledge when making choices about meaning.

Secondly, the projective element of teacher and student agency is informed by cultures of ‘deliverology’ (Ball et al. Citation2012) and ‘performativity’ (Ball Citation2003); pressure to deliver results in the future can influence choices made by individuals in the classroom (Hall and McGinity Citation2015; Berry Citation2012; Biesta Citation2015). For example, individuals might not feel free to facilitate or make authentic choices about meaning during lessons. Instead, as Kulz explores, in academy environments, teaching can become ‘equated with enabling information reproduction for exams’ (Citation2018, 53). Such an approach can prevent students from making their own choices about meaning and nudge them towards relying on safe, ‘formulaic frameworks’ (Bleiman Citation2020, 31) that facilitate manufactured interpretation. For example, Gibbons notes that an increased use of analytical acronyms such as ‘PEE’ or ‘PEEL’ within English classrooms might serve to marginalise ‘student choice, voice and personal response’ (Gibbons Citation2019, 36).

Finally, present-tense evaluative choices can be shaped by the teaching environment. The ‘datafication’ of teaching (Stevenson Citation2017) can render data-driven courses of action more salient. For example, an emphasis on numerical data can encourage teachers to adopt a ‘data-driven’ disposition rather than a learning-driven disposition (Lewis and Holloway Citation2019, 48), influencing the choices they make about how to explore texts with their students. If a teacher knows that a certain manufactured interpretation will help a student achieve a certain grade or lesson objective, they may focus on ensuring that their students can reproduce said interpretation. Where students are concerned, an academy’s data-driven, performative orientation can alter the choices they make about meaning; Xerri has explored how ‘examination pressure’ can encourage a ‘mechanistic’ approach to poetry (Citation2013, 134) that sees students attempt to guess ‘what the teacher already knows is hidden in the text’ instead of engaging personally as readers (136).

Based on the above analysis, it seems that a school’s influence over classroom choices can facilitate the development of ‘performance-oriented’ rather than ‘learning-oriented’ classrooms (Watkins Citation2010, 5). Performance-oriented subjects are more concerned with proving their competence than they are with improving and developing their abilities or ideas. In the context of English, a performance orientation can result in the reproduction of manufactured interpretations and the limiting of opportunities for students to make choices about meaning. This can reduce the amount of epistemic engagement that occurs in the classroom. Moreover, as ‘a performance-oriented school culture is linked with poorer motivation and greater disengagement predicting lower attainment’ (5), such a situation appears undesirable. An environment that imposes fewer performance-oriented influences upon student and teacher choice could help students develop valuable literacy skills.

IF in the English classroom

As IF seeks to make active choice a default (Keller et al. Citation2011) part of the reading experience, I suggest that it can provide opportunities for students to make and discuss choices about meaning, stimulating worthwhile forms of classroom dialogue. As such, a work of IF can become a ‘digital artefact’ that can help create ‘dialogic space’ in the classroom (Hennessy Citation2011, 463). Providing space for students to attempt making their own choices about meaning requires ‘teachers to yield the floor to students’ (Murphy et al. Citation2009, 761) and make ‘space for multiple voices,’ thus moving away from ‘monologic practices’ (Lyle Citation2008, 225). Such open, unpredictable and ‘dialogue-intensive pedagogies can produce sizable gains in students’ literal and inferential comprehension’ (Wilkinson and Binici Citation2015), explaining why trials ‘focusing on cognitively challenging talk’ are producing promisingly positive results (Education Endowment Foundation Citation2020) and why approaches like reciprocal reading are also thought to be beneficial, particularly for disadvantaged children (Education Endowment Foundation Citation2019). Therefore, I seek to align the acceptance of risk and unpredictability that is inherent in the use of non-linear, choice-based texts as classroom resources, with a form of evidence-based practice (in this case, dialogic teaching) in an attempt to conceptualise IF as a resource that could be readily accepted by teachers working in secondary school English classrooms. The reason I see an acceptance of unpredictability as inherent in the classroom usage of IF is because a teacher cannot know which links a given group will select and the reasons they will offer for making said selections.

Compared to other resources and text types, IF could impose different influences upon the choices that teachers and students make, potentially influencing the modes of textual engagement experienced. As works of IF can be fictional but not traditional,Footnote2 projected onto a board but used differently to presentation slides, classified as stories but also classified as games, they occupy and establish a liminal space that could influence behaviour in a variety of ways.

Returning to Emirbayer and Mische’s framework for analysing agency (Citation1998), IF could alter the reflective element of student choice by encouraging students to broaden the pool of past experiences from which they draw when engaging with a text. For example, as works of IF are very often written in the second person (Costanzo Citation1986) and depend upon physically active and deliberate choices to a greater extent than traditional texts, students may feel more personally involved in a work of IF than they might in another type of text and thus be nudged towards drawing upon ‘funds of knowledge’ that are otherwise marginalised (Moll et al. Citation1992, 132; Thomson and Hall Citation2008, 87). This could broaden the range of interpretations that a class will be able to offer, increasing the likelihood of epistemic textual engagement. Similarly, the nature of IF can alter the reflective element of teacher agency. Instead of being preoccupied with imitating other people’s interventions, as can happen when adopting an evidence-based approach (see, for example, Gilbert Citation2018), IF might nudge the teacher towards adapting to the class’s choices and therefore focusing their thinking more upon the learning activity that is taking place.

Likewise, IF could influence the projective element of student and teacher agency. Whereas students and teachers might usually think about present-tense activity in relation to future test performance, the instant feedback that works of IF offer in the form of new passages when a link has been selected could nudge students towards thinking more about the impact of their decisions upon the text and its meaning than about their own future performance in a test. Again, this could result in a shift towards more epistemic engagement.

Additionally, IF could encourage teachers to think on their feet when making moment-to-moment choices about classroom practice; it could nudge them towards adapting to the unpredictable nature of the lesson by altering the tasks, questions and instruction that they enact, rather than thinking exclusively about how best to perform in a prescribed, objective-led and data-driven manner. As such, the IF form could nudge teachers towards attending to the unpredictable and could help them engage in ‘responsive teaching’ rather than test-focused, ‘formative assessment’ (Booth Citation2017). For example, an IF passage that contains a choice of links poses a problem to which there is not necessarily a correct answer: which link shall we select? Such a ‘contestable’ (Reznitskaya and Wilkinson Citation2017, 59) dilemma might nudge teachers away from choosing to offer students judgemental, objective-led forms of verbal feedback and towards making ‘talk moves’ (Michaels and O’Connor Citation2015, 334) that expose the thinking of the students involved. Likewise, student choices and corresponding attitudes could be altered. As IF introduces an element of fluidity into the classroom due to its dependence on the choices of individuals in the class, it could encourage students to engage more personally in the reading process and abandon approaches that situate them as entirely dependent upon their teacher. The salience of choice inherent in IF’s form could nudge students towards making choices about meaning in a more deliberate fashion.

Overall, it appears possible that IF could help shift performance-oriented classrooms towards becoming more learning-oriented by foregrounding the significance of choice and placing less focus upon tests or manufactured interpretations. Also, by foregrounding the significance of choice and creating a space for students to discuss the variety of meaning-making choices available, it could help students to engage epistemically with language. While this perspective might smack of ‘easy optimism’ (Buckingham Citation2003, 314), I feel that these potential benefits render the use of IF in the English classroom worthy of further investigation.

IF as a dialogic teaching tool

IF could be effective at scaffolding worthwhile forms of dialogue. As a form, IF has been used to stimulate collaboration in the classroom. Desilets, focusing on parser-based IF, asserts that IF ‘grows well in the one-computer classroom’ (Citation1989, 75). They note the following:

‘With one student at the computer, typing what a class wants to try and reading the results aloud, and the rest of the class actively engaged in mapping, keeping track of problems, and generating suggestions, interactive fiction can become an engaging experience for groups of almost any size, an experience that involves students in the essential kind of thinking that we call reading’ (77).

Similarly, the Interactive White Board (IWB) has also been used to scaffold dialogue (Mercer, Hennessy, and Warwick Citation2019). The IWB ‘offers the facility for teachers and students to share and discuss ideas on texts in a whole-class setting’ (Mercer, Hennessy, and Warwick Citation2010, 203). A work of IF, projected onto a board, could allow for similar discussions to take place. More specifically, an IWB’s ‘“cover/reveal” facility’ can ‘focus students’ close attention’ onto part of a text, ‘thus scaffolding their learning about it by reducing the complexity of the task’ (204). Similarly, the fact that works of IF are chunked into passages could position IF as an intrinsically scaffolded form. Furthermore, links could intensify this scaffolding effect by focusing student attention on particular keywords or phrases – choices that the writer has made. While this may cause students to filter or skim texts, focusing their attention exclusively on links rather than the whole passage (Sosnoski Citation1999), it also has the potential to be a harnessable scaffolding tool. The choices that classes have to make between links could also elicit the sharing of different perspectives, as different students might want to select different links for different reasons. This could help teachers create a space for dialogue in the classroom.

Positioning IF in this manner – as a tool for scaffolding dialogue – enables me to use Alexander’s Dialogic teaching framework (Citation2020) to explore how a work of IF could be used to scaffold learning in the classroom. For example, outlines the ways that questions or tasks relating to a single passage could be used to stimulate ‘Learning Talk’ amongst students (142). By encouraging students to evaluate, discuss and justify the significance and validity of the choices they are making as they read, a teacher could use IF as a stimulus for purposeful dialogue. They could also encourage students to engage with the work cumulatively and epistemically by using the variety of choices available to the class as a way of encouraging the discussion of contrasting choices about meaning. Furthermore, outlines the ways that IF could help teachers respect Alexander’s dialogic teaching principles (131). For example, the fact that a single work of IF can be re-used across multiple lessons due to the variety of narrative pathways it contains means that conversations and lines of thought can accumulate and be carried across multiple lessons in an intratextual, cumulative dialogue. Also, by helping teachers to foreground the meaning-making choices of their students, IF could help teachers to achieve reciprocity in their approach to meaning-making during lessons. Such assertions, however, require considerable further investigation.

Table 1. Examples of how IF could be used to stimulate ‘learning talk’ (Alexander Citation2020, 142) in the classroom

Table 2. The relationship between dialogic teaching principles (Alexander Citation2020, 131) and the use of IF in the classroom

IF in action

I began this paper with a description of what English lessons often look like in the academy where I work. I shall now describe two different lessons – lessons in which I attempt to bring IF into my classroom for the first time. I shall describe these lessons through reference to my field notes, to feedback that I received from colleagues who observed one of the lessons in question and to transcripts of recorded episodes of classroom talk.

A first attempt

During the first of these lessons, I started to read a work of IF with a mixed ability group of year 7 students. The lesson took place on a cloudy mid-September morning. Due to the Coronavirus pandemic and the need for year group bubbles to be kept separate from one another, I was teaching my year 7 class in the library and not in a classroom. Students were sat behind disorderly rows of green-topped, rhomboid tables and I was stood at the front of the room, confined to an area that was marked out with tape. Projected onto the whiteboard in front of the students was a work of IF: ‘The Doodle’ (Holdstock Citation2020).

I remember feeling nervous and excited. Not only was I using a work of IF in the classroom, but I was using ‘The Doodle’ – a piece that I had written myself. I chose this work of IF because I knew it well and was not worried that we might encounter inappropriate content.

We explored ‘The Doodle’ collectively, engaging in whole class discussion, passage by passage. After reading each passage, I used open questions (akin to the examples provided in ) and follow-up questions to elicit developed verbal responses from students and to encourage them to engage with each other’s ideas. Moreover, during these exchanges we collectively decided upon the link we were going to select. I posed my follow-up questions in response to ideas that students expressed, and the lesson proceeded in a way that was partly defined by student thinking and student choices.

It was clear that students were eager to participate; many hands shot up whenever I asked a question. In particular, when asking which link we should choose in order to proceed and why, students were eager to respond and to offer competing or contrasting opinions. For example, students were keen to voice their opinions on whether we should select the ‘doodle’ link or the ‘thinking of home’ link in the opening passage (see ). Upon reflection, this suggests to me that the presence of choice within IF passages can help to stimulate and support discussion, where discussion refers to the ‘exchanging’ and ‘uncovering of juxtaposing viewpoints’ (Alexander Citation2020, 145). However, it was incumbent upon me, the teacher, to use questioning as a means of transforming this initial discussion into a more deliberative and interactive dialogue that one could characterise as ‘reciprocal’ and ‘cumulative’ (131). The reading activity did feel ‘purposeful’ (131). Not only did we, as a class, seek to uncover fresh parts of the narrative, but the interactions led to students considering the significance of the writer’s language choices, rendering the lesson a somewhat useful addition to the term’s descriptive writing scheme of work.

A colleague who works in the library remarked that there was ‘Good Q&A interaction’, that students were very ‘expressive’ in their answers and that students seemed to be ‘thinking carefully’. A newly qualified teacher who was observing the lesson commented that students gave ‘insightful responses to not only what we were told in the story’ but also in relation to what was ‘yet to come’. This suggests that the teacher observed what Alexander might term imaginative speculation (Citation2020, 144). The teacher also remarked that students seemed to take ‘ownership’ of the story via their ‘decisions’ and ended up analysing language ‘without really knowing it’. Such comments suggest that I had successfully relinquished some control of the students’ reading experience. Finally, the teacher also noted that my use of ‘class discussion with an emphasis on verbal responses allowed students to articulate thoughts and ideas which they may otherwise have struggled to communicate through written tasks’. These remarks suggest that ‘The Doodle’ enabled me to scaffold student thought and talk in a useful manner.

In field notes taken after the lesson, I described the experience as ‘joyous’ and reflected on the ‘rich ideas’ that students had expressed. In particular, I noted that ‘the class talked about the protagonist’s jealousy’ towards another character; I had not predicted that students would bring this up, and I was therefore pleased and surprised that this idea had arisen from our discussions. It suggests that the reading experience was at least somewhat reciprocal, and not entirely monologic. However, I also noted that there were some aspects of the lesson that required further thought:

‘I need to reflect more about how long the passages are, visibility for students around the room and how to hold the attention of students that drift. Also [,] the story was way too long - we were nowhere near finished!’

Upon reflection therefore, it appeared that, as well as the question of how to render discussions more student-led, questions relating to text-length, passage-length, font size, setting and classroom layout required further attention. In addition, at certain moments the attention of some students drifted. It seems possible that this drift was partly due to the fact that the lesson was dominated by teacher-led, whole class discussion, meaning that a limited number of students could participate verbally at any given moment. The fact that I was confined to a teaching space at the front of the room – a situation I was not yet fully accustomed to – may have contributed to my decision not to engage students in more student-led, small group discussion tasks. Moreover, the issues of poor visibility and passage-length may have contributed to students becoming distracted. Similarly, the text’s length may have made holding the attention of all students more challenging.

A closer look

I shall now jump forward in time. It is early December, 2020. I am teaching the same group of year 7s, but in a different classroom. Students arrive to the lesson after breaktime wearing masks and inside social distancing between myself and the students remains obligatory due to the Coronavirus pandemic. I am again confined to a taped-off area at the front of the room, and therefore refrain from greeting my students at the door. It is only the second time that I am attempting to use IF in the English classroom, and I am still nervous.

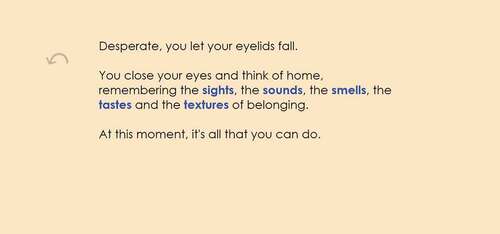

Since half-term, we have been reading and studying Michael Morpurgo’s novel, War Horse (Citation2017). This text has enabled us to think about the impact of World War One, but it arguably privileges an Anglocentric, white, male perspective (Jogie Citation2015). I want to help my students put the novel in context and think about a more diverse range of World War One experiences. Therefore, I have drafted a work of Interactive Fiction for us to read as a class: What Happens When You Close Your Eyes (Holdstock Citation2021).Footnote3 Although I, a white, male teacher, have written this work myself, each of the protagonists within the story is based upon a real-life person or situation that I have researched. For example, the work includes characters inspired by the experiences of Chinese and South African labourers whose stories I first encountered in resources created by Big Ideas Community Interest Company (Citation2018). As such, What Happens When You Close Your Eyes can be considered a work of Interactive, Historical Fiction that features protagonists from a diverse range of backgrounds. The opening passage of this story can be seen in .

Figure 2. The opening passage from What Happens When You Close Your Eyes (Holdstock Citation2021)

As we begin to read the story as a class, we discuss the opening passage:

Teacher (SH): Can we imagine how the character is feeling at this moment?

Sara: Maybe, umm, maybe he’s feeling, um … May- Maybe he’s feeling [inaudible]

SH: Say again? Say again – I didn’t hear you.

Sara: Maybe he’s feeling like really stressed, upset, he probably wants to be with his family.

SH: So stressed, upset, wants to be with his … You think it’s a he? His family?

Sara: It could be any gender, but like … [inaudible]

SH: Brilliant – Okay. Can anyone build on that, telling me why someone might want to be with their family, at a moment? Anil, you had your hand up bud.

Anil: Because, when there was like World War One, they sent people to like different places, um, to the countryside. And he’s probably moved away, and he’s tryna remember – home is London – and he’s tryna remember how London felt.

SH: So it could be – are you referring to evacuees who are sent away?

Anil: Yeah.

In the above extract, I begin by inviting students to engage imaginatively with the text, using a question akin to the imagination question I have exemplified in . SaraFootnote4 infers that the protagonist might want to ‘be with his family.’ At the ‘third turn’ (Alexander Citation2020, 114), I begin mirroring (Rogers Citation1945) her response back to her before querying her thinking (‘You think it’s a he?’). In doing so, I demonstrate to the student in question that I am listening to her in a reciprocal manner. Note that I am querying rather than offering evaluative feedback, so as to adopt a supportive rather than judgemental role. I do this because I am attempting to create a culture of ‘respect and risk-taking’ that will help students ‘feel safe to go public with their ideas’ (Michaels and O’Connor Citation2015, 335). I then open the discussion up to other students to see whether they can ‘elaborate’ or build upon Sara’s contribution (Alexander Citation2020, 111). At this point, Anil connects Sara’s idea about homesickness with his own knowledge, suggesting that students are working reciprocally, collectively and cumulatively in this exchange. He speaks of people who were ‘sent’ to the ‘countryside’ during the war. We have not talked about evacuees as a class, so Anil appears to be making connections between the text we are reading, Sara’s contribution and his own prior knowledge from beyond the secondary English classroom. In this exchange, it is my ‘talk moves’ (Michaels and O’Connor Citation2015, 334) that help render the discussion somewhat dialogic. However, note that we stop to talk at this particular moment in the lesson because the text is broken into passages and requires us to make a choice in order to continue. As such, the work of IF appears to be nudging us towards pausing and considering the potential meanings of the passage.

A few minutes later, we continue our discussion and try to decide which link to select. The choice we make will define how the narrative progresses. As such, students’ verbal contributions have the potential to help shape the text that we are reading. In the below episode, I begin by questioning another student, Joana:

SH: Does anyone else disagree and want to try and convince me that we should select something else other than sights? Joana.

Joana: Er, I think smells, because, er, they could give us some background. Like, for example, we could like smell cooking, like in the kitchen, like family members, so we could also like tell where they’re from.

SH: So if we select smells – that’s interesting – we might find out where the person is from, because … what? Because …

Joana: Because, er, like you could have like traditional cooking.

In this exchange, I seek to open up the discussion by asking students to challenge ideas that have already been shared. My questioning is ‘authentic’ (Reznitskaya and Wilkinson Citation2017, 59), in the sense that I do not have a prescribed answer in mind, and somewhat similar to the discussion question that is exemplified in . Arguably, the contestable dilemma that the passage demands we resolve (which link should we choose?) nudges me towards posing this question; when asking students if ‘we should select something else other than sights’, I am using the choice that the passage provides to initiate further discussion and reflection. Joana’s response can be seen as part of a teacher-led, collective and deliberative discussion; she is offering a counterargument to a preference that has already been stated by another student. Joana, unprompted, makes a connection between ‘smells’, the ‘kitchen’, ‘family members’ and ‘traditional cuisine’. She is exploring ideas that she personally associates with the word ‘smells’ and using these associations to begin making speculations about what might happen if we select ‘smells’. The choice of links contained within the passage in , in conjunction with the question I have posed, encourage Joana to explore the potential significance of an individual word. This suggests that links can serve to focus student attention on particular aspects of a passage and even encourage them to speak about the significance of certain language choices without the teacher explicitly asking them to do so. Moreover, as there is no single correct answer to select, it is possible that the text nudges me, the teacher, to make talk moves at the third turn that catalyse, rather than evaluate, student thought. When I say ‘because … what? Because …’, I am encouraging Joana to elaborate further rather than providing her with evaluative feedback relating to what she has said. It seems possible therefore, looking at this exchange, that IF is shaping my teaching decisions and helping me to avoid relying exclusively on the ‘so-called “recitation” script of closed teacher questions, brief recall answers and minimal feedback’ (Alexander Citation2020, 15).

Conclusions

In this article I have begun to explore the dialogic possibilities for IF in the secondary academy English classroom. Reflecting upon my initial experiences of incorporating works of IF that I have written into my own lessons, I maintain that IF holds the potential to influence the choices that teachers and students make and the literacy practices that they therefore enact. Specifically, I suggest that works of IF could help teachers facilitate dialogic exchanges during which classes collaboratively interrogate the potential meanings of a text. I also suggest that the relationship between IF and the types of choices, questions and talk moves that are made by teachers and students is a topic that is worthy of further investigation. While I acknowledge that this article only begins to explore these ideas in a very specific context and does not examine in detail the challenges that using IF can pose, it seems possible that, by rendering contestable, active choice-making a more salient part of English lessons, IF could help teachers facilitate dialogic and epistemic forms of textual engagement. While I also acknowledge that works of IF might not necessarily become popular teaching resources in their own right, it seems possible, based on this initial research, that experimenting with IF as a teaching resource might help teachers like myself to develop a better understanding of how dialogic space can be created in the classroom and to consider how we can go about incorporating a beneficial degree of unpredictability into our lessons.

Having claimed that IF might help teachers to empower students to draw upon their own personal funds of knowledge, I must also note that I have provided little evidence in support of this claim. While I have shown that IF can enable students to formulate personal responses and tentative predictions, I have not here provided examples of IF enabling students to draw extensively upon knowledge they have accumulated during the course of their own lives beyond the school gates. Moreover, I have not here explored the ways that the choices and links contained within works of IF might constrain, as opposed to support, meaning making and dialogue. The potential disadvantages of using IF are also worthy of further examination.

To interrogate the ideas introduced in this paper, further analysis of classroom interactions and student responses to works of IF encountered in the classroom will be necessary. Moreover, analysis of interactions occurring across multiple lessons that feature the same work of IF could enable researchers to explore the ways that IF (in conjunction with other teacher-initiated interventions) might change the quality of classroom interactions over an extended period of time. Further research could also explore the challenges and opportunities that designing and using works of IF for and in a variety of educational settings might provide. Most interestingly perhaps, research could explore the extent to which IF, by making active choice a default classroom activity, might serve as a beneficial ‘behaviour-change delivery vehicle’ (Gawande Citation2010, 96) that enables teachers and students to adopt a more dialogic stance. In my own context, for example, it will be interesting to observe how, as my research into the possibilities for IF in the English classroom continues, my own teaching practices and the practices of the colleagues with whom I work, begin to alter.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Educational Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London. I am particularly grateful to my supervisors, Dr Vicky Macleroy and Dr Francis Gilbert, for their ongoing support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Samuel Holdstock

Samuel Holdstock is a secondary school English teacher and an MPhil/PhD student, based in London.

Notes

1. For an example of what such a work can look like, read ‘The Doodle’ (Holdstock Citation2020).

2. IF does not fit neatly into traditional categories of fiction; it is neither prose, poetry nor drama.

3. The version of this story that is available online is a redrafted, more up to date version of the original story used in this lesson.

4. Throughout this article I use pseudonyms when referring to students.

References

- Alexander, R. 2020. A Dialogic Teaching Companion. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ball, S. 2003. “The Teacher’s Soul and the Terrors of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 215–228. doi:10.1080/0268093022000043065.

- Ball, S., M. Maguire, A. Braun, J. Perryman, and K. Hoskins. 2012. “Assessment Technologies in Schools: ‘Deliverology’ and the ‘Play of Dominations’.” Research Papers in Education 27 (5): 513–533. doi:10.1080/02671522.2010.550012.

- Berry, J. 2012. “Teachers’ Professional Autonomy in England: Are Neo-liberal Approaches Incontestable?” FORUM 54 (3): 397–409. doi:10.2304/forum.2012.54.3.397.

- Biesta, G. 2007. “Why ‘What Works’ Won’t Work: Evidence-Based Practice and the Democratic Deficit in Educational Research.” Educational Theory 57 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5446.2006.00241.x.

- Biesta, G. 2016. The Beautiful Risk of Education. New York: Routledge.

- Biesta, G. J. J. 2015. Good Education in an Age of Measurement. New York: Routledge.

- Big Ideas Community Interest Company. 2018. “The Unremembered: World War One’s Army of Workers.” Accessed 24th February 2021. https://www.big-ideas.org/project/the-unremembered/

- Bleiman, B. 2020. What Matters in English: Collected Blogs and Other Writing. London: English and Media Centre.

- Booth, N. 2017. “What Is Formative Assessment, Why Hasn’t It Worked in Schools, and How Can We Make It Better in the Classroom?” Impact. https://impact.chartered.college/article/booth-what-formative-assessment-make-better-classroom/

- Buckingham, D. 2003. “Media Education and the End of the Critical Consumer.” Harvard Educational Review 73 (3): 309–327. doi:10.17763/haer.73.3.c149w3g81t381p67.

- Costanzo, W. 1986. “Reading Interactive Fiction: Implications of a New Literary Genre.” Educational Technology 26 (6): 31–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44425198

- Desilets, B. J. 1989. “Reading, Thinking, and Interactive Fiction.” The English Journal 78 (3): 75–77. doi:10.2307/819460.

- Education Endowment Foundation. 2019. “Reciprocal Reading.” EEF. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/projects-and-evaluation/projects/reciprocal-reading/

- Education Endowment Foundation. 2020. “Dialogic Teaching.” https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/projects-and-evaluation/projects/dialogic-teaching/

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What Is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103 (4): 962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294.

- Gawande, A. 2010. The Checklist Manifesto: How To Get Things Right. London: Profile Books.

- Gibbons, S. 2019. “Death by PEEL?” the Teaching of Writing in the Secondary English Classroom in England.” English in Education 53 (1): 36–45. doi:10.1080/04250494.2019.1568832.

- Gilbert, F. 2018. “Riding the Reciprocal Teaching Bus. A Teacher’s Reflections on Nurturing Collaborative Learning in A School Culture Obsessed by Results.” Changing English 25 (2): 146–162. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2018.1452606.

- Giovanelli, M., and J. Mason. 2015. “‘Well I Don’t Feel That’: Schemas, Worlds and Authentic Reading in the Classroom.” English in Education 49 (1): 41–55. doi:10.1111/eie.12052.

- Hall, D., and R. McGinity. 2015. “Conceptualizing Teacher Professional Identity in Neoliberal Times: Resistance, Compliance and Reform.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 23 (88): 1–21. doi:10.14507/epaa.v23.2092.

- Halliday, M. 2013. “Meaning as Choice.” Chap. 1. In Systemic Functional Linguistics: Exploring Choice, edited by L. Fontaine, T. Bartlett, and G. O’Grady, 15–36. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hennessy, S. 2011. “The Role of Digital Artefacts on the Interactive Whiteboard in Supporting Classroom Dialogue.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 27 (6): 463–489. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00416.x.

- Holdstock, S. 2020. “The Doodle.” Itch.io. makingmeanings.itch.io/the-doodle

- Holdstock, S. 2021. “What Happens When You Close Your Eyes.” Itch.io. http://www.makingmeanings.itch.io/what-happens-when-you-close-your-eyes

- Jogie, M. R. 2015. “Too Pale and Stale: Prescribed Texts Used for Teaching Culturally Diverse Students in Australia and England.” Oxford Review of Education 41 (3): 287–309. doi:10.1080/03054985.2015.1009826.

- Keller, P. A., B. Harlam, G. Loewenstein, and K. G. Volpp. 2011. “Enhanced Active Choice: A New Method to Motivate Behavior Change.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 21 (4): 376–383. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2011.06.003.

- Kopas, M. 2015. “Introduction.” In Videogames for Humans, Twine Authors in Conversation, edited by M. Kopas, 5–19. New York: Instar Books.

- Kulz, C. 2018. Factories for Learning. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Lewis, S., and J. Holloway. 2019. “Datafying the Teaching ‘Profession’: Remaking the Professional Teacher in the Image of Data.” Cambridge Journal of Education 49 (1): 35–51. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2018.1441373.

- Lyle, S. 2008. “Dialogic Teaching: Discussing Theoretical Contexts and Reviewing Evidence from Classroom Practice.” Language and Education 22 (3): 222–240. doi:10.1080/09500780802152499.

- Maher, J. 2011. “Let’s Tell a Story Together.” Maher.filfre.net. http://www.maher.filfre.net/if-book/

- Mercer, N., S. Hennessy, and P. Warwick. 2010. “Using Interactive Whiteboards to Orchestrate Classroom Dialogue.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education 19 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1080/1475939X.2010.491230.

- Mercer, N., S. Hennessy, and P. Warwick. 2019. “Dialogue, Thinking Together and Digital Technology in the Classroom: Some Educational Implications of a Continuing Line of Inquiry.” International Journal of Educational Research 97: 187–199. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2017.08.007.

- Michaels, S., and C. O’Connor. 2015. “Conceptualizing Talk Moves as Tools: Professional Development Approaches for Academically Productive Discussions.” In Socializing Intelligence through Academic Talk and Dialogue, edited by L. B. Resnick, C. S. C. Asterhan, and S. N. Clarke, 332–347. Washington: American Educational Research Association.

- Moll, L. C., C. Amanti, D. Neff, and N. Gonzalez. 1992. “Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms.” Theory Into Practice 31 (2): 132–141. doi:10.1080/00405849209543534.

- Morpurgo, M. 2017. War Horse. London: Egmont.

- Murphy, P. K., I. A. G. Wilkinson, A. O. Soter, M. N. Hennessey, and J. F. Alexander. 2009. “Examining the Effects of Classroom Discussion on Students’ Comprehension of Text: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Educational Psychology 101 (3): 740–764. doi:10.1037/a0015576.

- Reznitskaya, A., and I. A. G. Wilkinson. 2017. The Most Reasonable Answer. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

- Rogers, C. R. 1945. “The Nondirective Method as a Technique for Social Research.” American Journal of Sociology 50 (4): 279–283. doi:10.1086/219619.

- Sosnoski, J. 1999. “Hyper‐Readers and Their Reading Engines.” Chap. 9. In Passions, Politics, and 21st Century Technologies, edited by G. Hawisher and C. Selfie, 161–177. Logan: Utah State University Press‐NCTE.

- Stevenson, H. 2017. “The “Datafication” of Teaching: Can Teachers Speak Back to the Numbers?” Peabody Journal of Education 92 (4): 537–557. doi:10.1080/0161956X.2017.1349492.

- Sunstein, C. R. 2017. “Misconceptions About Nudges.” SSRN Electronic Journal 2 (1): 61–67. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3033101.

- Thaler, R. H., and C. R. Sunstein. 2009. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Thaler, R. H., C. R. Sunstein, and J. P. Balz. 2013. “Choice Architecture.” Chap. 25. In The Behavioral Foundations of Public Policy, edited by E. Shafir, 428–439. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Thomson, P., and C. Hall. 2008. “Opportunities Missed And/or Thwarted? ‘Funds of Knowledge’ Meet the English National Curriculum.” The Curriculum Journal 19 (2): 87–103. doi:10.1080/09585170802079488.

- Watkins, C. 2010. “Learning Performance and Improvement.” Research Matters 34: 1–15. https://www.ioe-rdnetwork.com/uploads/2/1/6/3/21631832/c_watkins_learning_performance_improvement.pdf

- Wells, G. 1990. “Talk about Text: Where Literacy Is Learned and Taught.” Curriculum Inquiry 20 (4): 369–405. doi:10.1080/03626784.1990.11076083.

- Wilkinson, I., and S. Binici. 2015. “Dialogue-Intensive Pedagogies for Promoting Reading Comprehension: What We Know, What We Need to Know.” Chap. 3. In Socializing Intelligence through Academic Talk and Dialogue, edited by L. Resnick and S. Asterhan, 35–48. Washington: American Educational Research Association.

- Xerri, D. 2013. “Colluding in the ‘Torture’ of Poetry: Shared Beliefs and Assessment.” English in Education 47 (2): 134–146. doi:10.1111/eie.12012.

- Yandell, J. 2019. “English Teachers and Research: Becoming Our Own Experts.” Changing English 26 (4): 430–441. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2019.1649087.