ABSTRACT

In the English for Academic Purposes (EAP) classroom, speaking is a relatively marginalised learning activity, often employed merely to facilitate transition between activities which prioritise communication skills deemed more important. A significant consequence of this privation is limited practice in situated discourse. This paper presents a theorised account of an instance of situated discourse: Quality Talk in a reading circle within an EAP classroom. With reference to a single dialogic spell unfolding around a specific issue, I examine participants’ verbal transactions and the ways in which these enhance high-level comprehension of text. Overall, this account seeks to highlight the efficacy and affordances of situated discourse as a social mode of cognition in EAP instruction.

Introduction

In the hierarchy of communication skills central to instruction in English for Academic Purposes (EAP), writing invariably occupies the top tier while reading and listening typically vie for second or third place. Speaking, however, is given relatively short shrift in the EAP classroom. A significant consequence of this privation is limited practice in situated discourse, a mode of guided talk within a particular educational context which encourages students to engage in negotiation and joint construction of meaning towards a specified end (Heller and Morek Citation2015; Shea Citation1993). This paper presents an elaborated account of an instance of situated discourse: reading circle participants discussing a literary text in an EAP class. In tracking the verbal transactions which emerge in a single dialogic spell, I advance theorised explanations of their effect on students’ high-level comprehension of text. These explanations are informed, among other considerations, by the efficacy and affordances of such discourse for EAP instruction. To interpret and analyse participants’ verbal exchanges, I draw on key elements of Wilkinson, Soter, and Murphy’s (Citation2010) Quality Talk discussion model.

Quality Talk

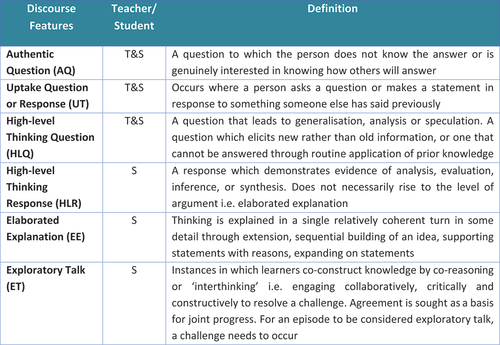

Quality Talk is a multifaceted and thus flexible model for conducting classroom discussion, developed from a sustained collaboration of like-minded researchers in the early 2000s. The original model integrated nine extant approaches to classroom talk, which the researchers had gleaned from a comprehensive meta-analysis of the field (Murphy et al. Citation2009). Quality Talk sought to improve students’ high-level comprehension of text, which the researchers conceptualised as reflective, critical-analytic thinking about, around and with text. This definition of high-level comprehension was based on a taxonomy of discourse features in the form of an analytical rubric which characterised and evaluated the quality of discussions with respect not just to argumentation but to thinking. Key discourse features included authentic questions, high-level thinking questions, and uptake (Nystrand et al. Citation1997); elaborated explanations (Webb Citation1991); extra-textual connections (affective responses, intertextual references, and previously shared knowledge); and reasoning words (Wegerif and Mercer Citation1997). The discourse feature central to this paper is exploratory talk (Mercer Citation2000), discussed below. below presents a summarised version of the analytical rubric adapted for use in the present account. Overall, the basic assumption of Quality Talk is that certain observable, identifiable verbal utterances exchanged in situated discourse can be considered proximal indices of corresponding higher-order cognitive processes such as high-level comprehension and critical-analytic reasoning. Taken together, these discourse features provide a frame of reference which represents Quality Talk in its ideal form.

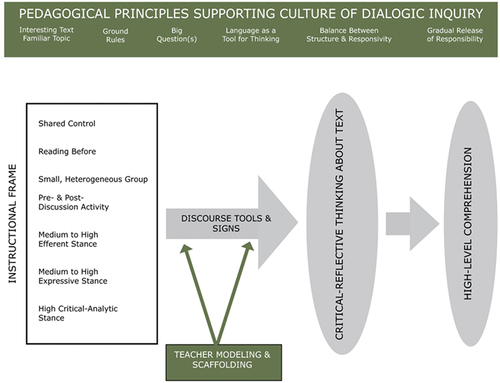

Quality Talk comprises four instructional components: an ideal instructional frame, which provides parameters important for quality discussion; discourse tools and signs, which are discursive elements or features teachers can utilise to both foster and recognise productive talk; teacher modelling and scaffolding, indicating conversational moves to initiate and facilitate talk; and several pedagogical principles, drawn from perspectives on language learning essential for sustaining a culture of dialogic inquiry. below (Wilkinson, Soter, and Murphy Citation2012) illustrates how the four instructional components interact, and how they relate to critical-reflective thinking and high-level comprehension. In summary, the context for Quality Talk discussions is provided by the instructional frame, which is itself subsumed by a broader classroom culture of dialogic inquiry, signified and informed by the pedagogical principles. Together, the context and culture foster the discursive elements of tools and signs, which lead to learners engaging in critical-reflective thinking about and around text. Teacher scaffolding is used to initiate learners into the kind of dialogic productive talk which generates this critical-reflective thinking. Learners’ active critical-reflective thinking, as a result, contributes to their high-level comprehension of text.

Figure 2. Components of the Quality Talk approach.

Quality Talk has been shown by numerous studies to be particularly effective in promoting higher-order thinking as a social mode of cognition (e.g. Davies and Esling Citation2020; Murphy and Firetto Citation2017; Murphy et al. Citation2016; Soter et al. Citation2008). My hope was that the culture of dialogic inquiry enabled by Quality Talk would sustain an atmosphere of critical interrogation (Abrami et al. Citation2008) in the reading circle. Engaging thus would lead participants to wrestle discursively with open-ended issues, ill-structured problemsFootnote1 and authentic contexts thrown up by the texts (Lai Citation2011), which, ideally, would gradually foster an enhanced disposition to critical thinking. Quality Talk is also effective as an analytical instrument and, as such, served as my primary mode of analysis.

Exploratory talk

As noted earlier, an important feature of Quality Talk is exploratory talk (Mercer Citation1995), of which the excerpt under analysis is an excellent example. Exploratory talk ideally construed is a protracted spell of situated discourse which sees participants co-construct knowledge by engaging collaboratively and critically to resolve a challenge. A significant effect of this engagement is individual participants generating reasons to support their thinking. In doing so, participants often make visible the various elements of argumentation employed in their responses as well as the thinking motivating these elements. Exploratory talk results in a sort of collective reasoning or ‘interthinking’, itself characterised by a ‘dynamic relationship between intermental activity (social interaction) and intramental activity (individual thinking)’ (Littleton and Mercer Citation2013, 10; original emphasis). While interthinking is dynamic, mediated by diverse linguistic expression and characterised by viewpoint diversity, it is nonetheless geared towards a specific end, namely a deeper, accreted understanding of the text and the contextual issues arising from both text and understanding. All these features taken together often constitute what I call a transactional dialectic, a dynamic cognitive-behavioural process inherent in text-based situated discourse. Participants’ exchanges in such conditions can range from co-operative to constructively divergent to notably adversarial, yet still be collaborative in pursuing the resolution of an authentic question. In such a vibrant context of interthinking, what often emerges is a much higher level of comprehension among participants than is usually able to be achieved from individual thinking (Moshman and Geil Citation1998).

Approaching the session

The reading circle was an elective class available to interested students in a London university’s International Foundation Programme (IFP). This cohort consisted of nine students, three of whom (Samir, Satya and Kolya) are represented anonymised in the analysed excerpt. The Tuesday morning session was designated the reading circle, where participants would meet each week to discuss a fresh text they had spent the previous week reading. I had two intentions in choosing literary texts as our main resource: to spark participants’ interest by introducing materials and instruction significantly different from the standard instrumental approach to EAP; and to draw them in further using the appeal of personalisation. I hoped that the relative familiarity of the human stories presented in the texts combined with the classroom’s relaxed environment would lead to generative discussion. According to Miller (Citation1995), students’ discursive exchanges about texts which motivate them affectively are able to shape dialogic thinking characterised by ‘self-reflexive strategies and the intellectual disposition to use them’ (para. 6). In short, when participants gathered for a reading circle session, they would arrive with a personal ‘stake in the game’.

Interpreting participants’ discourse

The analysis which follows takes the form of an interpretive and evaluative commentary on participants’ dialogic exchanges in the excerpt, using selected discourse featuresFootnote2 to identify potential instances of high-level comprehension. This interpretation consists both of my initial inferences as participant observer while examining the session in situ and of recursive examination subsequently. My objective throughout was to interpret each speaker’s words as precisely and charitably as I could, attributing what I discerned to be their most authentic intention when speaking. Since participants’ contributions were so diversely expressed, it was necessary to draw on a range of theoretical perspectives – including political philosophy and moral psychology – to interpret the exchanges most effectively. In doing so, I adopted Walton’s (Citation1989) primary tenet in interpreting dialogue: that every argument should be assessed on its own terms, including considerations such as argument type, text type, and contextual particularities. As is evident in the analysis, every statement and response expressed in the excerpt invited such considerations and warranted commensurate interpretations.

The session - My Hobby (Tom Fabian)

This session explored a short story which traces the delusional ruminations of the first-person narrator and protagonist, George Blake, an old man seeing out his days in a residential home. Though he fancies himself a sincere do-gooder, a self-confessed model citizen who had a wife and son he loved, Blake is in fact a narcissistic serial killer: ‘I used to kill in order to help people; it was sort of like charity with me’ (Fabian Citation2017, para. 4). As noted above, the selected excerpt is significant as it represents a model episode of exploratory talk. The analysis which follows therefore explores the range of ways participants co-constructed meaning around issues arising from the text as they interrogated it. The discussion was contentious in evaluating the narrator’s character: was he indeed a ruthless psychopath, or genuinely concerned about the welfare of people who found themselves in unfortunate circumstances they felt unable to manage? Satya had taken a stance at variance with the majority: that Blake was not necessarily a psychopath but rather someone whose behaviour perhaps bore some moral warrant. Given that Blake’s motives may have been sincerely charitable, she contended, his actions could thus be framed as solutions to problematic situations. While Satya’s stance on the issue was clearly tendentious, it nonetheless represented a challenge to the position broadly held by everyone else in the circle, and we felt it worth exploring with a view to resolution.

Samir commences the discussion with a stark expostulatory equation which explicates the grim logic of Satya’s reasoning: ‘if a husband abuses his wife, this guy killing him would solve her problems, right? And then if there’s a hundred problems a day you’d kill a hundred people’ (turn 1). Instead of retreating in the face of Samir’s High-level Thinking Question, Satya counters with the proposition that murder is acceptable if ‘you have a good reason’ (turn 2). The wording of this statement neatly circumvents Samir’s tacit imputation that Satya approves of the narrator’s psychopathy, as the context of the statement suggests it prioritises philosophical over moral considerations. I say ‘suggests’ as it is unclear to me as an observer at this stage whether the ‘good’ in Satya’s comment refers strictly to a philosophical or a moral good. Her general perspective as far as I can tell is philosophical whereas the subject under discussion is definitely moral.

Whatever her intention in making this particular statement in defence of the narrator’s rationale for his actions, by invoking the narrator’s purpose Satya engages a specific kind of argument: reasoning which prioritises purpose can be characterised as teleological. This is an important concept in Aristotle’s theory of justice, set out in his Nicomachean Ethics (Crisp Citation2014). In sum, Aristotle’s teleological account of justice posits that the purpose or telos of a social practice determines what rights or freedoms should be ascribed to the person enacting that practice. The implication is that rights and freedoms necessarily differ between individuals, depending on the social status or worth of the practice in which they are engaged. In turn 2 of the current excerpt, Satya thus presents an instance of teleological reasoning and, in those terms, her argument works. Because of the literal power which consists in the narrator’s role as a murderer, his rights or freedoms prevail over those he kills. The difference on this occasion is that Satya’s argumentative concerns refer not merely to the personal but to a wider sphere, that of public justice.

The rights and duties of an individual are conceptually provisional, as they are contingent on the evolving norms and values of the societies which create and shape them. This is one among several other factors which together inform the subtle complexities of justice. Invariably more complicated are issues of justice involving society at large. While Satya’s argument in defence of the narrator has some merit in the teleological terms considered above, it is generally weak as it is not difficult to argue against her case from a range of alternative philosophical perspectives of justice. It seems appropriate then, given the ancient (Aristotelian) provenance of teleological reasoning, to evaluate Satya’s proposition briefly in terms of a more recent and contrasting account of political philosophy: Rawls’s (Citation1999) justice as fairness. This theory of justice advocates equal basic liberties for all members of society, with the most disadvantaged being afforded maximum benefit where necessary. According to Rawls (Citation2005), there is a basic problem with teleological accounts of justice in a society where, ideally, everyone begins from an original position of equal rights or freedoms. In such a society, ascribing to an individual (in this case, the narrator) the freedom to pursue his telos (murder) will result inevitably in conflict. This is because the exercise of individual freedom to fulfil one’s telos to one’s preferred extent poses an inherent threat to the equivalent rights of other citizens to exercise their own individual freedoms. In the context of such a society, one person’s individual rights are no more important than another’s. And in the context of the story, the narrator’s freedom to pursue his telos and kill another is no more important than the targeted person’s freedom to pursue his telos, whatever that may be, without the fear of it being curtailed. Being murdered would curtail that freedom.

While reasoning of this kind is appropriate and compelling in the purely abstract considerations of philosophy, in the messier domain of moral pragmatics, where personal conviction, emotion and experience hold more sway, the power of such reasoning is rather easily compromised (Haidt Citation2013, Hume Citation(1739) 1969; Skitka Citation2010). Returning to the discussion, Samir’s first reaction to Satya’s move is one of incredulity (turn 3). Nonetheless, he gathers himself to respond with a compelling observation, adducing what he perceives as Hitler’s indefensible reasoning. His point is simple: that in the context of evaluating human social behaviour, ‘not all reasons are good’ (turn 3). In exposing Satya’s shaky rationalising thus, Samir has inadvertently invoked an element of Paul’s (Citation1981) conceptualisation of ‘weak sense’ critical thinking. This is critical thinking employed in a deliberately limited way to defend one’s position at the expense of genuine truth-seeking, which would consist in exposing oneself to the best possible evidence.

Kolya then enters the discussion (turn 4) and starts off by confirming the point Samir has just made. Characteristically, Kolya repeats the opposing position (in this case, Satya’s) before referring to the narrative to introduce a countervailing perspective. In this response he encircles the quoted text with several direct questions which seem in their stridency to come across as explicit challenges to Satya: ‘So what do you think about the last sentence … . What does this mean? … Can you ignore this?’ Unfazed, Satya makes no attempt to evade the textual evidence presented to her: ‘Okay, it means he wants to kill her’ (turn 5). Perhaps to bolster her weakening position, she paraphrases a phrase from the narrative which broaches the possibility that the narrator may have been joking about his urge to resume killing: ‘Because we know he said he doesn’t have fun doing it’. Kolya responds exasperatedly by repeating his previous Textual Reference and attempting to address any outstanding interpretive loopholes. This includes a persuasive rebuttal of Satya’s suggestion that the narrator may have been joking: ‘He’s not ironic here – he means it! Something’s not fun does not always means you don’t want’ (turn 6). Kolya seems with these observations to be simultaneously tying together a clearer understanding of his own quote as well as extrapolating Satya’s Textual Reference to a general knowledge of the real world. This is hard cognitive work.

In an attempt perhaps to mitigate what the narrator says about rekindling his old hobby, Satya’s response in turn 7 is to change tack completely as she brings in the narrator’s age and infirmity. Yet she still seems with this move to be rationalising, by presenting creative scenarios as deflections. Her remarks in this turn are made smilingly, however, perhaps indicating that she is having fun just drawing it out and may be about to concede. My inference of Satya’s behaviour in this instance is informed by the model of rationalisation advanced by D’Cruz (Citation2022), who characterises such cognitive endeavour as a kind of creative accomplishment. ‘Rationalizing’, he argues, ‘is the process of generating and rehearsing narratives that have the credible appearance of genuine deliberation and inquiry but whose narrative arc aims at exculpation or self-justification’ (D’Cruz Citation2022, 107; original emphasis). While rationalising is sometimes done in good faith and often without malicious intent, the reasons adduced for a given position may nonetheless be spurious, offering merely the appearance of relevance to the issue under consideration. At worst, rationalising can be used perniciously and lead to grave consequences, particularly if one is in a position of power. A striking case is that of a certain British politician, who was found to have deliberately misled the House of Commons with ‘his own after-the-event rationalisations’ (House of Commons Committee of Privileges Citation2023, 6). Such diversionary artifice is precisely – though rather less seriously – what Satya seems engaged in here.

Kolya, however, is not distracted and appears in fact to have crystallised his chain of reasoning: ‘But it’s his old hobby. And that shows his intention: people don’t do hobbies they don’t like, so he likes this. He wants to kill people, you know? He enjoys this’ (turn 8). The next four turns are brief Uptake responses, though in a final show of resistance against both Kolya and Samir’s insistence that the narrator must be a psychopath, Satya repeats Blake’s dubious statement that he does not enjoy killing. As she is finishing this remark, she bursts into laughter, literally holds her hands up and relents: ‘I understand, guys … of course!’ Yet even with the deficiencies in her reasoning now exposed, Satya still cannot help but close with a cheeky punchline: ‘But is it wrong?’

At this point however, her train of motivated reasoning, in which she seemed committed to not just sustaining but substantiating her evaluation of the protagonist, appears finally to have terminated. What is clear in Satya’s overall argument is that, however accomplished or creative at spouting reasons one might be, the power of reasoning to justify one’s views on issues of morality, while potentially extensive, is limited (Dunning and Ballantyne Citation2022). Indeed, Mercier and Sperber (Citation2017) point out that in some situations there are very few good reasons to be found for certain moral choices. And sometimes, however one’s choices are rationalised, there are only weak reasons – or even no good reasons at all. At such points, Hauser (Citation2006) argues, we encounter the realm of objective morality. This was one of those instances. Satya did not simply run out of argumentative options; she could well have continued her inventive line of reasoning. But on this issue or, in Walton’s (Citation2006) more accurate terms, under these conditions of dialogue, her reasoning was comparatively weak and this in the end rendered her argument unsustainable.

Assailed from the outset with considerable disconfirming evidence against her entrenched position, Satya nonetheless sought to fend off Kolya and Samir’s evidentiary challenges. Her behaviour can be inferred as exemplifying a defensive posture which Kahan (Citation2012), for example, argues is entirely natural: instinctive defiance is a predictable human response when one is initially confronted with information which contradicts one’s fundamental beliefs. This phenomenon is borne out in Kahan’s theory of identity-protective cognition, as well as in accounts of motivated reasoning and cognitive dissonance reduction (Pinker Citation2022). While it is generally one’s default reaction in such circumstances, resistance to mounting evidence against one’s stance often carries substantial reputational risk. In the face of this risk and of a higher quality argument by her peers which even for her proves insuperable, Satya arrives with gracious reluctance at what Redlawsk et al. (Citation2010) call an affective tipping point. At this realisation she concedes and, on this occasion as is typically the case in our reading circle, collective reasoning prevails. Kolya and Samir’s collaborative delivery of stronger reasons decisively undermine Satya’s solitary efforts at reasoning her way spuriously through an increasingly insupportable case.

Conclusion

The excerpt ends with an observation by Samir which marks exploratory talk as an effective site for situated discourse which leads to interthinking and high-level comprehension. Referring to Satya’s capitulation, Samir comments that he likes ‘The idea that if she know she’s wrong, she’s going to tell you’ (turn 13). This points to a fundamental precept of critical thinking, which is a ‘willingness to reconsider and revise views where honest reflection suggests that change is warranted’ (Facione Citation1990, 28). In an episode bristling with moral and moralistic contentions, with divergent viewpoints expressed and challenged with equal robustness, and where artful goading threatened at every turn to undermine collaborative reasoning, this seemed a reassuring note upon which to conclude our session.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Clifford Kast

Clifford Kast completed his PhD at UCL Institute of Education, where he is now collaborating as an Honorary Research Fellow. He leads the EAP programme at the University of Roehampton, London.

Notes

1. Ill-structured problems are those located in authentic contexts but without a definite answer. The answer depends on the respondent’s ability to make judgements based on reasoning and prior experience (King and Kitchener Citation2004).

2. For the purposes of clarity, the initial letters of the discourse features referred to in the analysis will be capitalised.

References

- Abrami, P. C., R. M. Bernard, E. Borokhovski, A. Wade, M. A. Surkes, R. Tamim, and D. Zhang. 2008. “Instructional Interventions Affecting Critical Thinking Skills and Dispositions: A Stage 1 Meta-Analysis.” Review of Educational Research 78 (4): 1102–1134. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308326084.

- Crisp, R., Ed. 2014. Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Rev. ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- D’Cruz, J. 2022. “Rationalization, Creativity, and Imaginative Resistance.” In Reason, Bias, and Inquiry: The Crossroads of Epistemology and Psychology, edited by N. Ballantyne and D. Dunning, 107–126. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Davies, M. J., and S. Esling. 2020. “The Use of Quality Talk to Foster Critical Thinking in a Low Socio-Economic Secondary Geography Classroom.” Australian Journal of Language & Literacy 43 (1): 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03652047.

- Dunning, D., and N. Ballantyne. 2022. “Introduction.” In Reason, Bias, and Inquiry: The Crossroads of Epistemology and Psychology, edited by N. Ballantyne and D. Dunning, 1–8. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fabian, T. 2017. “My Hobby.” The Strand Magazine. https://strandmag.com/the-magazine/short-stories/my-hobby/.

- Facione, P. A. 1990. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction. Newark, DE: American Philosophical Association.

- Haidt, J. 2013. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. London: Penguin.

- Hauser, M. 2006. Moral Minds: How Nature Designed Our Universal Sense of Right and Wrong. New York: Ecco/HarperCollins Publishers.

- Heller, V., and M. Morek. 2015. “Academic Discourse as Situated Practice: An Introduction.” Linguistics and Education 31:174–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2014.01.008.

- House of Commons Committee of Privileges. 2023. Matter Referred on 21 April 2022 (Conduct of Rt Hon Boris Johnson): Final Report. Fifth Report of Session 2022–23. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/40412/documents/197199/default/.

- Hume, D. (1739) 1969. A Treatise of Human Nature. London: Penguin.

- Kahan, D. M. 2012. “Ideology, Motivated Reasoning, and Cognitive Reflection: An Experimental Study.” Judgment and Decision Making 8 (4): 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500005271.

- King, P. M., and K. S. Kitchener. 2004. “Reflective Judgment: Theory and Research on the Development of Epistemic Assumptions Through Adulthood.” Educational Psychologist 39 (1): 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3901_2.

- Lai, E. R. 2011. “Critical Thinking: A Literature Review.” Pearson Research Reports 6:1–49.

- Littleton, K., and N. Mercer. 2013. Interthinking: Putting Talk to Work. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Mercer, N. 1995. The Guided Construction of Knowledge: Talk Amongst Teachers and Learners. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Mercer, N. 2000. Words and Minds: How We Use Language to Think Together. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Mercier, H., and D. Sperber. 2017. The Enigma of Reason. London: Harvard University Press.

- Miller, S. M. 1995. Vygotsky and Education: The Sociocultural Genesis of Dialogic Thinking in Classroom Contexts for Open-Forum Literature Discussions. Hanover College, OH: Psychology Department. https://psych.hanover.edu/vygotsky/miller.html.

- Moshman, D., and M. Geil. 1998. “Collaborative Reasoning: Evidence for Collective Rationality.” Thinking & Reasoning 4 (3): 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/135467898394148.

- Murphy, P. K., and C. M. Firetto. 2017. Classroom Discussions in Education. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Murphy, P. K., C. M. Firetto, L. Wei, M. Li, and R. M. Croninger. 2016. “What REALLY Works: Optimizing Classroom Discussions to Promote Comprehension and Critical-Analytic Thinking.” Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3 (1): 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215624215.

- Murphy, P. K., A. O. Soter, I. A. Wilkinson, M. N. Hennessey, and J. F. Alexander. 2009. “Examining the Effects of Classroom Discussion on students’ Comprehension of Text: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Educational Psychology 101 (3): 740–764. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015576.

- Nystrand, M., A. Gamoran, R. Kachur, and C. Prendergast. 1997. Opening Dialogue: Understanding the Dynamics of Language and Learning in the English Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Paul, R. 1981. “Teaching Critical Thinking in the Strong Sense: A Focus on Self-Deception, World Views, and Dialectical Mode of Analysis.” Informal Logic 4 (2): 2–7. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v4i2.2766.

- Pinker, S. 2022. Rationality: What it Is, Why it Seems Scarce, Why it Matters. London: Penguin.

- Rawls, J. 1999. A Theory of Justice. Rev. ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rawls, J. 2005. Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Redlawsk, D. P., A. J. Civettini, and K. M. Emmerson. 2010. “The Affective Tipping Point: Do Motivated Reasoners Ever “Get it”?” Political Psychology 31 (4): 563–593. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00772.x.

- Shea, D. P. 1993. “Situated Discourse: The Sociocultural Context of Conversation in a Second Language.” Pragmatics and Language Learning 4:28–49.

- Skitka, L. J. 2010. “The Psychology of Moral Conviction.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4 (4): 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00254.x.

- Soter, A., I. A. Wilkinson, P. K. Murphy, L. Rudge, K. Reninger, and M. Edwards. 2008. “What the Discourse Tells Us: Talk and Indicators of High-Level Comprehension.” International Journal of Educational Research 47 (6): 372–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2009.01.001.

- Walton, D. N. 1989. “Dialogue Theory for Critical Thinking.” Argumentation 3 (2): 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00128147.

- Walton, D. N. 2006. Fundamentals of Critical Argumentation. Cambirdge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Webb, N. M. 1991. “Task-Related Verbal Interaction and Mathematics Learning in Small Groups.” Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 22 (5): 366–389. https://doi.org/10.2307/749186.

- Wegerif, R., and N. Mercer. 1997. “Using Computer-Based Text Analysis to Integrate Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Research on Collaborative Learning.” Language and Education 11 (4): 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500789708666733.

- Wilkinson, I. A. G., A. O. Soter, and P. K. Murphy. 2010. “Developing a Model of Quality Talk About Literary Text.” In Bringing Reading Research to Life, edited by M. G. McKeown and L. Kucan, 142–169. New York: Guildford Press.

- Wilkinson, I. A. G., A. O. Soter, and P. K. Murphy. 2012. “Quality Talk.” http://www.quality-talk.org/.