ABSTRACT

This position paper presents the state-of-the art of the field of workplace commitment. Yet, for workplace commitment to stay relevant, it is necessary to look beyond current practice and to extrapolate trends to envision what will be needed in future research. Therefore, the aim of this paper is twofold, first, to consolidate our current understanding of workplace commitment in contemporary work settings and, second, to look into the future by identifying and discussing avenues for future research. Representative of the changing nature of work, we explicitly conceptualize workplace commitment in reference to (A) “Temporary work”, and (B) “Cross-boundary work”. Progressing from these two themes, conceptual, theoretical and methodological advances of the field are discussed. The result is the identification of 10 key paths of research to pursues, a shared agenda for the most promising and needed directions for future research and recommendations for how these will translate into practice.

Introduction

Organizations need workers who are psychologically attached to their work, both now and in the future (Bakker, Albrecht, & Leiter, Citation2011). However, work is increasingly taking place outside of traditional organizational contexts (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2013). As the context of work is changing it is important that we continue to study how workers’ attachments or bonds with work develop. In this paper, we acknowledge the variety of workplace bonds that workers can develop, such as acquiescence, instrumental, commitment, and identification (Klein, Molloy, & Brinsfield, Citation2012). In light of these developments, in this position paper we ask ourselves how the changing world of work should impact the way we do research on workplace commitment.

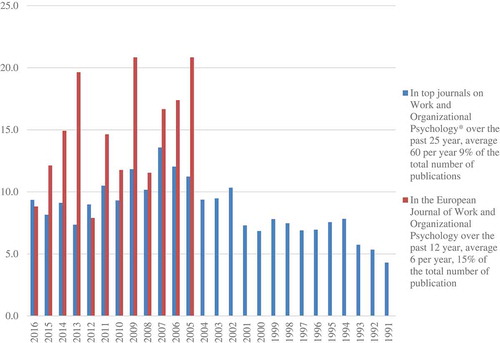

Despite field-level critiques in the form of declarations of irrelevance and conceptual redundancy at the end of the previous century (e.g., Baruch, Citation1998; Cappelli, Citation2000), the commitment literature, as a field, seems alive and healthy, judging from McKinley, Mone, and Moon’s (Citation1999) standards. In their view, a literature is healthy when it shows signs of consistency, scope, and novelty. With regard to consistency, we see that the commitment construct continues to deliver a steady flow of empirical output over the years. A systematic search of papers with commitment as one of the topics in the top ten journals on Work and Organizational Psychology shows a consistent concentration (). Over the past 25 years, workplace commitment is a topic which garners on average 60 publications per year and is responsible for 9% of the total number of papers in the top ten journals on Work and Organizational Psychology, (SD = 2.20). The European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology has published on average six commitment papers per year, 15% of the total number of papers (SD = 4.43) . This proportion of commitment-related publications per year is similar for the Journal of Vocational Behaviour (10 papers, 18%), the Journal of Organizational Behaviour (10 papers, 16%), the Journal of Applied Psychology (13 papers, 14%), and the Journal of Organizational and Occupational Psychology (6 papers, 14%).

Figure 1. Proportion of publications on workplace commitment over 25 years.

* Journals include: J. of Appl. Psy., J. of Voc. Beh., J. of Org. Beh., J. of Pers. & Soc. Psy., J. of Occ. & Org. Psy., Psy Bull., Pers. Psy., Org. Beh. & Hum. Dec. Proc., J. of Occ. Health Psy. and Eur. J. of Work & Org. Psy.

Apart from consistency, for a literature to stay relevant, it also has to demonstrate scope; referring to the range of phenomena the theory can explain (McKinley et al., Citation1999). In this regard, the commitment literature is also healthy, as the literature has evolved to cover an increasingly large number and novel targets of commitment in the workplace (e.g., commitment to the client organization,Swart, Kinnie, Rossenberg, & Yalabik, Citation2014) and has been applied to explain many commitments outside of the workplace (commitment to change efforts, Klein, Citation2014).

The final dimension identified by McKinley et al. (Citation1999) is novelty – strong and original theoretical contributions which provide alternative ways of thinking. With respect to novelty, the commitment literature has also come a long way, and is in the vanguard of new ways of thinking and doing research, as shown in studies taking a person-centred approach (e.g., by using Latent Profile/Mixture Analysis, Meyer & Morin, Citation2016), and studies taking a temporal approach (e.g., by using Latent Trajectory Analysis Solinger, van Olffen, Roe, & Hofmans, Citation2013).

Another aspect of novelty, however, is the craft of conceptually “updating” the commitment construct in light of new approaches and developments happening in its ecological environment. Numerous conceptualizations of commitment exist in the literature, and there is currently debate over how to define commitment. Some scholars believe it is a force that binds an individual to a course of action (Meyer & Herscovitch, Citation2001), while others consider it a particular kind of bond (e.g., Klein et al., Citation2012); or believe that bond to be attitudinal in nature (e.g., Solinger, Hofmans, & Olffen, Citation2015). There is also debate about the dimensionality of the construct (Allen, Citation2016; Klein & Park, Citation2016), and the need for multiple commitment constructs for different targets versus a single, target-neutral perspective. For the past 20 years, the most prominent view of commitment has been the three-component model (TCM) presented by Meyer and Allen (Citation1991). In this model, commitment is defined as “a force that binds an individual to a course of action of relevance to one or more targets” (Meyer & Herscovitch, Citation2001, pp. 301), with that force experienced as one or more mindsets – Affective commitment (emotional “want to” or desire), Normative commitment (“ought to” or obligation), and Continuance commitment (“have to” or cost; Meyer & Allen, Citation1997) (ANC).

The TCM perspective has generated a tremendous amount of research regarding the antecedents and consequences of commitment, but has been criticized for a number of reasons including a lack of theoretical justification for the three mindsets and being overly broad, with definitional overlaps with closely related constructs, and having been based on organizational commitment and needing to be adapted to other commitment targets (Klein & Park, Citation2016; Klein et al., Citation2012; Solinger, van Olffen, & Roe, Citation2008). We do not adopt a particular definition of commitment for this paper but note that in extrapolating current trends to envision the future of workplace commitment, the TCM does not facilitate focusing on more concise, dynamic, and target-neutral perspectives.

Indeed, recent changes taking place in the world of work, including but not limited to the growth in “nonstandard work” (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2013), suggest that the commitment literature still has some significant steps to make in the form of updating our understanding of the construct. The drivers of these changes include the desire to minimize costs and increase flexibility for firms, booms in communicative technologies, market changes, neoliberal economic policies, the importance of knowledge, and networked ways of working that reduce the boundaries and barriers between people, organizations, and other entities (Ashford, George, & Blatt, Citation2007; Kalleberg, Citation2009). In such an ecological context, how people experience work can be expected to become more varied while work in traditional organizational becomes less relevant (Meyer, Citation2009).

It is in this contextual landscape that we start this paper with discussion of two such themes which comprehensively represent the changing nature of the way people work (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2013), (A) “Boundaryless work”, and (B) “Temporary work”. Consistent with Lakatos’ (Citation1970) approach to the development of scientific research programmes, we first consolidate (identifying the “hard core”) and develop an understanding of workplace commitment in relation to these two themes. Then conceptual, theoretical, and methodological advances and directions for future research are developed in the form of “research paths”, that may guide future research to make changes on the “protective belt” through new auxiliary hypotheses (Lakatos, Citation1970). The two themes lead onto section (C) labelled “Into the future of workplace commitment”, in which four themes are explored which push forward current discussions. In this section, our aim is to look ahead in terms of what may be, thereby picturing the future for the field of workplace commitment and offering an active and exciting research agenda for scholars to pursue.

Workplace commitment: from a historical to a contemporary understanding

Much of our historical understanding of workplace commitment draws on a type of employment relationship best explained using Social Exchange Theory (SET) (Blau, Citation1964) and the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, Citation1957). SET views the employment relationship as one in which outcomes are compared with inputs as the basis for an exchange between the organization and employee. Rather than merely a rational or transactional exchange, SET includes emotional investment and attachment through social inducements, such as social support and mutual caring. Thus, because workers feel supported and cared for, a reciprocal process may involve commitment, which is “a volitional psychological bond reflecting dedication to and responsibility for a particular target” (Klein et al., Citation2012, p. 137).

Fundamental changes in the work context weaken the applicability of these social exchange theories. In the light of contemporary work, there are three assumptions about workplace commitment, which are rooted in SET that we will address in this position paper. First, SET is based on cross-context regularity, assuming that the manner in which employees develop bonds with their work is similar and generalizable to all work contexts. We are looking to move away from this perspective of one standardized employee – organization dyadic context by focussing on non-standardized work settings as well as the diversity of experiences of workplace commitments. Second, while SET explanations emerged from a world of solid, stable, and long-term employment (Ashford et al., Citation2007), we unpack how social exchange is different given a shorter time frame. Third, SET assumes the work setting to consist of only one long-term employer for an employee (Ashford et al., Citation2007), whereas in both temporary as well as cross-boundary work the work setting may involve multiple parties with whom a social exchange can take place.

(A) Workplace commitment and “temporary” work

Temporary employment within the context of an organization covers a broad spectrum of arrangements including fixed-term employment contracts, on call employment, temporary agency employment, in-house temporaries, and independent contractors (Campbell & Burgess, Citation2001; De Jong, Citation2014; Gallagher & Sverke, Citation2005). Temporary employment also exists outside the boundaries of an organization in temporary organizations (TOs), this is discussed in more detail in Section C.

(1) Commitment in a temporary work setting: a short-term relationship

Organizational commitment has widely been used as a demonstration or consequence of a successful socialization process (e.g., Lance, Vandenberg, & Self, Citation2000; Vandenberg & Seo, Citation1992) representing an emerging bond between the worker and the organization (Klein et al., Citation2012; Solinger et al., Citation2008). Commitment is viewed as a consequence or outcome of organizational socialization, thus “deeper” workplace bonds of this kind may take more time to develop and change. Contrary to the socialization process, workplace commitment has been predominantly studied as a timeless state and, therefore, we know very little about how commitment evolves over time.

Within the short-term social exchange relationship in a temporary employment setting, workers may be limited in their socialization process and limited in developing commitment. Empirical evidence on the development of commitment over time finds a diversity of commitment processes, providing no particular evidence for an absolute minimum socialization time required for commitment to develop (Solinger et al., Citation2013). Temporary workers, on the other hand, have been found to start experiencing the relational nature of psychological contracts after 6 months (Lee & Faller, Citation2005). At that time, supervisors and co-workers start to offer their full support to the temporary colleagues, which could possibly improve their productivity, trust, and commitment.

In temporary work settings, rather than commitment, work place bonds may also be of another type. With the absence of an organization offering a sustainable work relationship characterized by job security, career development and positive attitudes (Rousseau, Citation1995), the short time frame may accentuate transactional obligations, rather than a relational bond involving reciprocity, mutual trust (McLean Parks, Kidder, & Gallagher, Citation1998), and commitment. This may be comparable to one-off interactions, in which people tend to interact in a more transactional way, whereas in continuing interactions people become more cooperative (e.g., Trivers, Citation1971).

The theorizing behind the expected lower commitment or transactional type of bond of temporary employees compared to permanent employees as outlined above has not always materialized empirically. Indeed, while some studies have found that temporary workers report lower levels of commitment (e.g., Biggs & Swailes, Citation2006; Coyle-Shapiro, Morrow, & Kessler, Citation2006), other studies have found that temporary workers can display similar or even higher levels of commitment than permanent workers (e.g., De Cuper & De Witte, Citation2008; Chambel, Sobral, Espada, & Curral, Citation2013; Haden, Caruth, & Oyler, Citation2011).

Research path 1

It is proposed that in a temporary work setting, workers are more likely to develop transactional types of workplace attachment and develop lower levels of commitment. Further research should examine this proposition, and whether the relationship is moderated by the duration of the contract and the extent to which temporary workers are treated more or less favourably.

(2) Commitment in a temporary work setting: not one organization, not one target

We first discuss commitment to more than one organization as is often the case in temporary work, and, second, the substitution of commitment from the traditionally employing organization to other targets more long term in nature.

Commitment to multiple employers over time

When their assignment ends, some individuals, particularly those with stronger bonds, may retain some of their commitments throughout their transition to a new organization (Breitsohl & Ruhle, Citation2013, Citation2016). These remaining commitments may have implications for commitments at the new organization to the extent they create conflicting demands on the temporary worker (Breitsohl & Ruhle, Citation2013; Klein, Molloy, & Cooper, Citation2009). Temporary workers may comparatively evaluate their consecutive employers, such that commitment to the new organization is formed according to the relative favourability of conditions (Breitsohl & Ruhle, Citation2013).

As a result, when analysing the formation of a specific workplace commitment for temporary workers, research may need to consider both prior and current commitment targets. While conceptual research on workplace commitment is beginning to integrate such interactions (e.g., Klein et al., Citation2016), empirical studies are still rare (e.g., Breitsohl & Ruhle, Citation2016). They are important to study, however, as despite being in the past, they still might influence emotions, cognition, and behaviour (Klein, Brinsfield, Cooper, & Molloy, Citation2016). To detect such influences, early research on commitment introduced the concept of commitment propensity (e.g., Cohen, Citation2007; Mowday, Porter, & Steers, Citation1982). Despite the anticipated usefulness of commitment propensity as a possible explanation for inter-individual differences, conceptual and empirical work on commitment propensity is still lacking (Ruhle, Citation2013). Another approach is the use of experiences related to quondam commitments; that is commitments that no longer exist but were once consequential for an individual (Klein et al., Citation2016). With an increasing number of possible commitments and commitment-related experiences, especially for temporary workers, such interactions may be worthy of further empirical attention.

displays the possible relationships between workplace commitments starting at any point in time (t0). In the case of temporary workers, a specific event such as an assignment transition will likely cause shifts in several of their commitments (t1). For example, commitment to the profession (commitment A) would likely remain unchanged, but commitment to one prior supervisor (commitment B) may remain, becoming a residual commitment, while commitment to the prior project (commitment C) may dissipate, becoming a quondam commitment. Yet, those residual and quondam commitments might still influence current commitments (in t1) as well as the formation of future commitments (t2).

Commitment to multiple targets

An alternative implication of working in a temporary work setting is the substitution of organizational commitment for other targets that may be more long term in nature, such as the job, career, or profession (Cooper, Stanley, Klein, & Tenhiälä, Citation2016). Rather than investing in various transient relationships, workers’ main attention may shift towards securing future assignments through task performance and professional reputation, which further differentiate temporary workers from permanent employees. A recent study comparing commitments of permanent and fixed-term staff, indeed, confirms that temporary staff have a more cosmopolitan commitment profile, including high commitment to the profession and the job and low commitment to the organization and the leader (Cooper et al., Citation2016).

This possible commitment to multiple targets and multiple organizations (Slattery et al., Citation2010) challenges the notion of “commitment to one entity” and raises questions as to whether and what inducements should be provided to temporary workers and by whom. Previous research has suggested that reciprocation by temporary workers is limited to target-specific training (internal to the client) which increased commitment only to that target (Chambel et al., Citation2013). Indeed, general (external) training did not increase commitment to the target offering the training.

Research path 2

Research on workplace commitments in temporary work settings will benefit from explicitly incorporating (1) the commitment history of individuals as well as the quondam and residual commitments to prior targets, and (2) commitments towards multiple targets which may substitute and replace commitment to the temporary employing target.

(3) What are methodological considerations for workplace commitments when work is temporary?

Methodologically, the above discussion on commitment in the context of temporary work suggests that commitment research needs to take into account the temporal dynamics of the construct. To develop such dynamic research, it requires a temporal theory, temporal methods of data collection, and temporal methods of analysis (George & Jones, Citation2000; Ployhart & Vandenberg, Citation2010). Roe (Citation2008) suggests that “the greatest obstacle” to doing this is “a mental one”, as researchers generally think in terms of variables (“what is”) and variation between people, rather than processes (“what happens”) and variation within people (Roe, Citation2008, p. 40).

First, explicit consideration of time in commitment theory is still in its infancy. Some scholars have developed specific commitment time-related constructs, like residual affective commitment (Breitsohl & Ruhle, Citation2013, Citation2016) and quondam commitment (Klein et al., Citation2016), to explore prevalent “temporal” phenomenon that cannot be sufficiently understood with the existing traditional commitment constructs. Interestingly, both concepts refer to the effects of past experiences – commitments individuals continue to have after leaving an organization (Breitsohl & Ruhle, Citation2013), or commitments individuals used to, but no longer have (Klein et al., Citation2016) – on individuals attitudes and behaviours in the present. Researchers might continue along this road when developing and refining commitment theory by specifying new temporal constructs that incorporate the subjective experience of time into their core premises. This will involve studying not only how past experiences preconditions the present, but also how anticipation and expectations of future commitment are embedded in the process. Career dynamics research provides a useful template for considering the temporal perspective of past, present, and future, both within a job over time, as well as across jobs over individuals’ careers (Super, Citation1980).

However, research that includes time-related constructs does not necessarily consider how the phenomena manifest themselves over “clock” time. For example, how long do the effects of residual commitment remain? Is quondam commitment experienced the same way when it results from a decline over 3 months than when it results from a more gradual decline over 2 years, or when it results from an abrupt shock? These questions illustrate the need to consider – not only subjective – but also more objective time dimensions, like the duration of phenomenon, the rate of change over time, the incremental versus the discontinuous nature of change, the frequency, and how these dimensions affect relationships between constructs (George & Jones, Citation2000). Thus, incorporating both subjective and objective time dimensions into theory building efforts is thus critical for the development of the commitment literature.

Second, to test these theories, it goes without saying that longitudinal research is needed. Excellent recommendations for authors wishing to design this type of research are already available (Ployhart & Vandenberg, Citation2010). Third, alongside appropriate longitudinal study design comes the selection of appropriate statistical models for examining dynamic features of phenomena over time. A number of very promising attempts have been made in which commitment scholars have begun to explore intra-individual change in commitment over time using latent growth modelling (i.e., Bentein, Vandenberg, Vandenberghe, & Stinglhamber, Citation2005; Lance et al., Citation2000; Vandenberghe, Panaccio, Bentein, Mignonac, & Roussel, Citation2011) or latent class growth modelling (Solinger et al., Citation2013). Examining how the processes of shaping commitments and its interconnected phenomena evolve over time may also be explored using methodologies that are inductive, interpretive, and qualitative in nature (Moran, Citation2009).

Research path 3

Future theorizing, methodology and conceptualization of workplace commitment needs to consider objective and subjective time dimensions and temporal methods of data collection.

(B) Workplace commitment in “cross-boundary work”

In addition to temporary work arrangements, the current research indicates that there is a growing trend to work, permanently, in cross-boundary contexts (e.g., Cappelli & Keller, Citation2013). Our thinking on alternative or contemporary work arrangements continues to be informed by the work of Pfeffer and Baron (Citation1988), who identified the trend towards “externalized” work arrangements in which workers may cross the boundaries of the organization (Ashford et al., Citation2007). The difference between temporary and cross-boundary has been identified by Marler et al. (Citation2002) who argue that it exists mainly in the perception of the worker, with temporary workers experiencing nonstandard work as marginalizing, while cross-boundary workers experiencing it as liberating, with job security rooted in development of skills.

When the blurring of organizational boundaries in work settings takes place, this changes the role of the organization (e.g., Gallagher & McLean Parks, Citation2001; Kogut & Zander, Citation1996), as well as the role of other potential targets of workplace commitment including the agency (Liden, Wayne, & Kraimer, Citation2003), the profession (Olsen, Sverdrup, Nesheim, & Kalleberg, Citation2016; Wallace, Citation1995), the career (Colarelli & Bishop, Citation1990; Goulet & Singh, Citation2002), and the client (Swart & Kinnie, Citation2014). Research on commitment to multiple targets is not new (Becker, Citation1992; Morrow, Citation1983; Reichers, Citation1985), however, the experience of permanent work in a cross-boundary work setting brings the notion of commitment to multiple targets to another level.

This section starts with section (4) a state-of-the art of commitment in cross-boundary work environments, including a (re-)conceptualization and direction to outstanding questions. Following this section, a series of three specific issues with regard to commitment in cross-boundary work environments are discussed; in section (5) methodological approaches to study multiple commitments, and in section (6) conflicts between multiple commitments.

(4) How should we (re-)conceptualize workplace commitment in a cross-boundary work environment?

With work increasingly taking place beyond the boundaries of the organization, it has been argued that the organization often cannot and should not be the primary target of commitment (Meyer, Citation2009; Reichers, Citation1985). Most research on workplace commitment, however, has been carried out in the context of dyadic employer–employee relationships within the organization (Coyle-Shapiro & Morrow, Citation2006). This is in stark contrast with the experience of cross-boundary contexts where workers frequently interact with a multitude of agents such as clients, other professionals, and teams (Swart & Kinnie, Citation2014) causing them to develop commitments to multiple foci or targets (Becker, Citation1992; Becker & Billings, Citation1993; Cohen, Citation2003).

This notion of the reality of the multiplicity of commitment was further developed into recognition of both internal and external targets (Siders, George, & Dharwadkar, Citation2001) that emerge and may compete as work takes place within and across organizational boundaries (Coyle-Shapiro & Morrow, Citation2006; Klein, Becker, & Meyer, Citation2012). The prior research on the multiple internal targets of commitment is relatively well-developed (Becker, Klein, & Meyer, Citation2009; Vandenberghe, Citation2009). Our understanding of external targets and the interplay between internal and external commitment targets, however, is scarce. This is surprising given that it is so central to the reality of working in contemporary employment settings.

When work takes place across the boundaries of the organization, especially in knowledge-intensive environments, this affects how and with whom employees interact and behave (Swart et al., Citation2014). Within this type of work arrangement, employees engage in work connected to a variety of entities which has been found to lead to commitment to multiple targets including organizations, teams, profession, and clients (Swart et al., Citation2014; Yalabik, Swart, Kinnie, & Van Rossenberg, Citation2017; Yalabik, van Rossenberg, Swart, & Kinnie, Citation2015). Prior research indicates that clients demand commitment for the sufficient delivery of services (Swart et al., Citation2014). The consultant can, for example, commit to her client, her network, and her profession.

Extensive previous work on commitment towards multiple targets in cross-boundary settings adopted the TCM of commitment TCM perspective (Meyer & Allen, Citation1997). We recognize alternative conceptualizations and measurement of multiple targets of commitment (e.g., Klein, Cooper, Molloy, & Swanson, Citation2013; Stinglhamber, Bentein & Vandenberghe, Citation2002) but note the dominance of the TCM, and indeed the recognized challenges of the use of continuance commitment in particular when researching cross-boundary commitment targets, e.g., client commitment (Swart et al., Citation2014; Yalabik et al., Citation2015) and agency commitment (Van Breugel, Van Olffen, & Olie, Citation2005).

It is important to note here that (i) there is a limited understanding of how workplace commitment operates across organizational boundaries, (ii) relatively few studies have looked at multiple targets of commitment across organizational boundaries, and (iii) we also know little about commitment and multiple-target behaviour (i.e., if the consultant is more committed to her client is she likely to engage in creative behaviour for that client at the cost of the employing organization). Some research has begun to unpack this and found that the target of commitment drives behaviour towards that target (Swart et al., Citation2014; Yalabik et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). For example, team commitment impacts upon knowledge sharing with the team (Swart et al., Citation2014).

The field continues to debate about the dimensionality of the commitment construct, and whether commitment can be consistently applied across workplace targets (Klein et al., Citation2013; Klein & Park, Citation2016). The uni-dimensionality of commitment does have the advantage that it is target-neutral (Klein et al., Citation2013) and therefore highly applicable across organizational boundaries. The advantage of this approach is, indeed, its parsimony and comparability across targets. It does have to be noted that there are also advantages of the multi-dimensionality of the measure of commitment, specifically in relation to the TCM. This does strengthen the commitment construct but, at the same time, challenges its applicability across organizational boundaries.

The multi-dimensionality of commitment has been explored within organizations using a person-centred approach (e.g., Meyer, Stanley, & Parfyonova, Citation2012), both by profiling multiple targets (e.g., Morin, Morizot, Boudrias, & Madore, Citation2011) as well as by profiling multiple (TCM) mindsets of commitment (e.g., Meyer et al., Citation2012) but we do need to understand this better in cross-boundary contexts. It is worth noting that using this approach can become cumbersome when considering multiple TCM commitment mindsets as well as an increasingly larger set of commitment targets (Klein & Park, Citation2016). As such, adaptations may be needed when applying the person-centred TCM perspective in cross-boundary contexts. Both camps do recognize the existence and need for assessment of commitment to multiple foci or targets. Indeed, in contemporary work settings, workers are found to have high levels of commitment to a large set of workplace targets (Morin et al., Citation2011; Swart et al., Citation2014).

Research path 4

Future research on workplace commitment in a cross-boundary work settings should recognize (1) the multiple internal and external targets, (2) the variations as to whether all components of the ANC model apply across boundaries, and (3) the complex interplay between multiple targets that are simultaneously held.

(5) How should multiple, simultaneously held commitments be studied?

While commitment to the employing organization may still be relevant (Klein et al., Citation2013), multiple commitments may occur which might be more salient or consequential than commitment to the organization. These commitments towards other agents inside and outside of the organization (Swart & Kinnie, Citation2014) or towards goals (Klein, Wesson, Hollenbeck, Wright, & DeShon, Citation2001), may be more relevant for specific desired behaviours.

With an increasing number of concurrent and consecutive commitments, some of which refer to the same type of target (e.g., multiple organizations), theory on workplace commitments needs to be developed accounting for cross-boundary work settings. Researchers ought to carefully consider and clearly define the commitments that are (less) relevant within a given setting. Extant conceptual work has greatly elucidated relationships between targets of different types with respect to target specificity, proximity, and thus salience (Klein, Molloy, et al., Citation2009, Citation2012). However, we know relatively little about the extent to and the conditions under which commitments to the same target type are compatible or contradictory.

Methodologically, we suggest adopting a “person-centred” approach (most frequently implemented as latent profile analysis; for excellent overviews, see, e.g., Meyer & Morin, Citation2016; Morin, Citation2016). Particularly when the number of commitment targets is high, the person-centred approach can represent systems of variables (vs. individual variables), acknowledging that a population may be composed of subgroups exhibiting different profiles of commitments, but permitting a more “holistic” perspective on individuals’ entire set of commitments (Meyer & Morin, Citation2016; Morin et al., Citation2011). It also tends to be less demanding with respect to interpretation and statistical power compared to modelling higher-way interactions between multiple commitments in a variable-centred (e.g., regression) approach (Meyer & Morin, Citation2016; Morin, Citation2016; Van Rossenberg, Citation2015). This approach has been applied to explore profiles of the TCM mindsets (e.g., Kabins, Xu, Bergman, Berry, & Willson, Citation2016; Meyer et al., Citation2012), and, profiles of commitments to multiple targets (e.g., Meyer, Morin, & Vandenberghe, Citation2015; Morin, Meyer, McInerney, Marsh, & Ganotice, Citation2015; Morin et al., Citation2011).

More specifically, a person-centred approach to multiple commitments may help elucidate the extent to and the conditions under which commitments may be compatible or conflicting (e.g., Cooper-Hakim & Viswesvaran, Citation2005; Meyer & Allen, Citation1997; Reichers, Citation1985). In addition, a person-centred approach may allow for unique insights by addressing questions such as: how many commitments can one have, i.e., can all commitments in a “high” profile (Meyer & Morin, Citation2016; Morin, Citation2016) be high? Or is there a “tradeoff” or “substitution” between commitments, particularly of the same target type (e.g., two organizations; Breitsohl & Ruhle, Citation2013)? Does this depend on the commitment mindset, e.g., are affective commitments generally more compatible than normative commitments? Do subgroups with a greater number of strong commitments behave differently compared to subgroups with fewer commitments? Finally, investigating the consistency of profiles across time (Kam, Morin, Meyer, & Topolnytsky, Citation2016; Meyer & Morin, Citation2016) could reveal whether some types of profiles (i.e., compatible commitments) tend to be more stable, while others tend to “dissolve” (i.e., conflicting commitments).

Research path 5

Research on workplace commitment in cross-boundary work settings will benefit from a person-centred approach, especially when analysing multiple commitments, their demands (compatible vs. conflicting), and transitions.

(6) What are conflicts between commitments?

One consequence of a multi-target research framework is the recognition and study of commitment-related conflict, i.e., a situation where the individual struggles to heed the responsibilities and sense of dedication implied in their felt bonds to multiple targets (cf. Golden-Biddle & Rao, Citation1997; Klein et al., Citation2012; Werhane & Doering, Citation1995). Earlier research often portrayed the targets of commitment as being in conflict with one another by default (e.g., Gouldner, Citation1957; Reichers, Citation1985), however, empirical studies are scarce and inconsistent. Whereas some researchers have found commitments to multiple targets to compliment or work in synergy (e.g., Cooper-Hakim & Viswesvaran, Citation2005; Johnson, Chang, & Yang, Citation2010; Lee, Carswell, & Allen, Citation2000; Swart & Kinnie, Citation2012), others have found that certain targets are often in danger of conflicting (Morin et al., Citation2011). More elaborate theorizing is therefore needed in order to account for these inconsistent findings.

The difficulty in the conceptualization of commitment conflicts stems from the variety of theoretical frameworks drawn on in explaining the complexities. One widely accepted perspective, based on the concept of compatibility, contends that multiple commitments can coexist as long as they are aligned in terms of demands and content (Randall, Citation1988; Vandenberghe, Citation2009). When such alignment is missing, conflict is likely to arise (Johnson et al., Citation2010; Morin et al., Citation2011: Vandenberg & Scarpello, Citation1994). We argue that one way of furthering this conceptualization of commitment conflict is by distinguishing between conflicts caused by incompatible goals, and those caused by incompatible values (cf. Reichers, Citation1985). This distinction has previously been made in the literature on social identity, which increasingly also deals with multiple targets (see e.g., Chen, Chi, & Friedman, Citation2013; Pratt & Foreman, Citation2000). A conflict arising due to incompatible goals implies an individual’s perception that he or she is unable to act in a way that simultaneously benefits two or more targets (Werhane & Doering, Citation1995). A values-based conflict, on the other hand, would imply that two commitment targets are perceived as being incompatible in terms of the norms or ideals they represent (Riketta & Nienaber, Citation2007). The latter type is likely to be perceived as graver, since it is more intimately related to the worker’s identity (cf. Golden-Biddle & Rao, Citation1997). Besides future research looking into these two broad categories of conflict, research will also need to identify the more proximal antecedents, as well as boundary conditions which may cause commitment conflicts to actualize.

Another theoretical lens useful for furthering our insight into commitment-related conflict is Lewin’s (Citation1943) field theory, which has previously been used to explain why commitment is more readily developed to salient, or psychologically proximal, elements of the environment (Klein et al., Citation2012; Vandenberghe, Bentein, & Stinglhamber, Citation2004). Applied to commitment conflicts, it can be predicted that the stress induced by commitment conflict will vary depending on the salience of the targets. For instance, a conflict between two targets that are both psychologically proximal will likely be perceived as more acute and demanding than one that includes distal targets.

To develop policies and interventions that may address such consequences, first a greater understanding of the coping strategies people may adopt to handle commitment-related conflict and their effectiveness is necessary. Coping strategies may include prioritization, i.e., the choice to temporarily act in line with one commitment over another, and reinterpretation (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, Citation1989) i.e., re-evaluating the situation in such a way that the targets are no longer perceived as conflicting. In the case of longer term, values-based conflicts (cf. Magenau, Martin, & Peterson, Citation1988) coping might also involve the complete cease of commitment to one or more targets.

Research path 6

Independent from the level of commitment, commitments to multiple targets can be experienced as conflicting. The conceptualization of commitment-related conflict in future research will need to consider more closely, and distinguish between, drivers, consequences, and coping strategies related to the construct.

(c) “Into the future of workplace commitment”

The two themes (A) temporary work and (B) cross-boundary work have structured our thinking about workplace commitment in contemporary work settings; however, contemporary work frequently includes both elements. In addition, many of the conceptual developments in workplace commitment are neither necessarily unique nor exclusive to either temporary work or cross-boundary work. To open up and progress beyond what we currently know about workplace commitment in contemporary work settings we explore four additional themes. These include: (7) commitment when a work setting includes both cross-boundary and temporary elements, (8) commitment to multiple targets in relation to other types of workplace bonds, (9) commitment without an organization, and (10) organizing commitments to multiple targets.

What is workplace commitment if the work setting is both cross-boundary and temporary?

Workplace commitment studied in a temporary work setting has primarily focused on temporary versus permanent work contracts. Yet these temporary contracts within a (more or less) permanent organizational structure are only one type of temporary work. One potential fruitful direction in the identification of alternative types of temporary work settings is the literature on TOs and projects. TOs are “a temporally bounded group of interdependent organizational actors, formed to complete a complex task” (Burke & Morley, Citation2016, p. 1237). This definition draws on complex tasks and the individual skills required to effectively deal with task complexity and task dependence, including diversely skilled individuals with highly specialized competencies who are unfamiliar with each other’s skills (Burke & Morley, Citation2016). Indeed, previous work shows a relationship between task performance and commitment (e. g. Klein et al., Citation2013; Locke & Latham, Citation2002). Furthermore the dependence between tasks has been related to commitment and performance (e. g. Aubé & Rousseau, Citation2005).

Four types of TO can be distinguished in terms of structure: “temporary organizations within organizations (i.e., intra-organizational), inter-organizational project ventures, project-based organizations and project-based enterprises/firms” (Burke & Morley, Citation2016, p. 1238). provides an overview.

Table 1. Overview types of Temporary Organizations.

Connecting this with what we know about workplace commitment in cross-boundary and temporary settings, we distinguish three dimensions. First, it could be stated that each type of temporary work differs in level of cross-boundary work, with intra-organizational project teams and project-based organizations operating exclusively inside the boundaries of the organization, and inter-organizational project ventures and project-based firms interacting more intensively outside the boundaries of an organization. In this way, the four types of TOs are a combination of temporary work and a particular level of cross-boundary work settings.

Second, within these four types of TO there will be different combinations of targets involved. With work taking place in a temporary and cross-boundary setting, this is likely to increase the complexity of commitment to multiple targets. For example work in a project team in which workers from multiple organizations come together to work for a solution for a client consists of a complex set of commitments to the team, organizations and the client. Third, the degree to which work in relation to each of these targets is temporary in nature will vary. For example, work for an inter-organizational team may be temporary in nature, but combined with a permanent contract with an organization, this may be experienced as job security. Even some occupational fields and jobs can be temporary in nature, with particular jobs disappearing as a result of being taken over by automation (Karmarkar, Citation2004).

The complexity lies in the three dimensions coming together and adding the fourth dimension: the level of change over time. This includes both changes in attachment bonds with different targets over the life-span of a temporary structure, as well as changes in the wider work setting. For example, work for a project-based enterprise may be temporary with regard to the team as well as the organization, however, over time it may still be experienced as secure and long-term in orientation if these collaborations provide ground for long-term professional and career commitment. In this way, the investment lies in building relationships and sustainable careers, which enables workers to stay competitive in the labour market (Greenwood & Empson, Citation2003; Løwendahl, Citation2005).

Research path 7

Four dimensions of complexity in commitments in temporary, cross-boundary projects which should be considered in future research include (a) the extent to which the setting is crossing organizational boundaries, (b) the number and diversity of commitment targets, (c) the level and differentiation of levels of temporariness with targets, and (d) the level of change in commitment targets over time.

How does commitment to multiple targets relate to other types of bonds with multiple targets?

New models and reconceptualizations have been attempting to redress the earlier stretched conditions of commitment through a unidimensional approach (Klein et al., Citation2012) and through a better delimitation of bonds (Klein, Molloy et al., Citation2009; Rodrigues & Bittencourt Bastos, Citation2012). We are, therefore, aware that the organization is not the only kind of target, nor is commitment the only kind of bond that can be developed. However, despite the advancing knowledge on the combination of commitment targets and their influence on different outcomes (Askew, Taing, & Johnson, Citation2013; Becker, Kernan, Clark, & Klein, Citation2015), studies combining commitment with the study of other types of bonds are still rare (for exceptions see; Meyer, Becker, & Van Dick, Citation2006; Riketta & Van Dick, Citation2005).

We should consider two sources here. First, there are other kinds of bonds acknowledged by commitment scholars that may attach the individual to certain targets (i.e., identification, embeddedness and entrenchment towards the organization; entrenchment towards career; embeddedness towards community; compliance towards the leader; engagement towards work). Targets are thus proliferating in other agendas, which is possibly in response to the increasing complexity of the work context plus the improved capacity of new research designs. Despite the lack of clarity caused by this proliferation, and although some of these “new” bonds seem to be yet immature or fashion constructs (Becker, Citation2016), studying the combination of commitment and other bonds towards different targets will add comprehension to the prediction of outcomes.

Identification is one type of bond that should be addressed in more detail as this field has made substantial progress in this respect. Generally defined as “the perception of oneness with or belongingness to some human aggregate” (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989, p. 21), identification can also be directed towards multiple foci (Ashforth, Harrison, & Corley, Citation2008; Riketta & Van Dick, Citation2005). Although conceptually rather similar, research has consistently shown that commitment and identification theoretically (van Dick, Citation2004) and empirically (Van Knippenberg & Sleebos, Citation2006) represent two different constructs. As pointed out by Van Knippenberg and Hogg (Citation2018), while identification denotes the integration of a certain target into one’s self-image, commitment represents an attitude towards that target. Meyer et al. (Citation2006) emphasized that only social targets can become objects of identification, whereas commitments can also be directed towards e.g., tasks, jobs, and visions. Further, according to the same authors, while identifications seem to develop at a largely unconscious level, commitments tend to be the result of a more conscious process.

In recent years, it has been established that organizational commitment often develops following organizational identification, and that identification mediates the effect of e.g., perceived organizational support and perceived prestige on commitment (Marique & Stinglhamber, Citation2011; Marique, Stinglhamber, Desmette, Caesens, & De Zanet, Citation2012; Stinglhamber et al., Citation2015). However, less research seems to have been directed towards the interrelationships of the two constructs for other targets than the organization. For instance, it is unclear whether one identification may induce commitment with several related foci – for instance, with both one’s workgroup and specific tasks – or whether there is strict correspondence of focus (cf. Van Dick, Wagner, Stellmacher, & Christ, Citation2004). More research is thus called for to further clarify the relationship between these two types of bonds.

Second, individual-level/non-work-related targets have been growing in prominence in the context of boundaryless work (i.e., community, family, friends, hobbies, etc.). Relatively neglected in the field of workplace commitment, other areas have been studying different kind of bonds to these targets, including: topophilia, place attachment, place identity, and rootedness by environmental psychologists (Lewicka, Citation2011; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010; Tuan, Citation1974), and child–parent attachment and other affectional bonds in different stages of one’s life cycle by developmental psychologists (Ainsworth, Citation1991). The permeability between personal context and work context leads to a variety of profiles that combine different kinds and nature of bonds towards a set of targets. Scholars may argue that many of these bonds are outside of the commitment field. However, once the area acknowledges the importance of profiles and the existence of competition and complementation among them (Research Path 4), limiting to only commitment profiles seem to be more a matter of convenience than plausibility.

To address this complexity, the field may benefit from interdisciplinary connections requires a better intersection between commitment research and other areas, inside and outside of Organizational Psychology. This may bring about the necessary discussion and development regarding the theoretical delimitation among types of bonds and types of targets. The study of commitment to multiple targets in relation to other type of bonds with multiple targets constitutes one promising avenue for enhancing our understanding of how internal and external context affects commitment.

Research path 8

The study of workplace commitment in a cross-boundary setting will need to more closely consider both multiple targets and multiple types of workplace bonds, (re)connecting with related areas within and beyond organizational psychology.

What is workplace commitment without an organization?

While it has long been established that “the organization” is the primary and most important target of commitment (Klein et al., Citation2009; Mathieu & Zajac, Citation1990), here we extend our previous thoughts on boundaryless and temporary work to consider commitment in cases where there is no organization. This extends our prior work and can be applied to both temporary and cross-boundary work.

Some evidence of commitment without an organization comes from the multiple-target approach where there are many targets of commitment outside of an employing organization (Gouldner, Citation1957; Reichers, Citation1985). Other targets of commitment include professions and occupations (Meyer & Espinoza, Citation2016), individual customers or clients (Swart & Kinnie, Citation2012) and those from other domains of life (Baruch & Winkelmann–Gleed, Citation2002) although admittedly the majority of these multiple-target studies have examined them alongside commitment to a central organization.

Moreover, in the wider psychology literature, bonds of commitment exist independent of organizations; they are the result of evolutionary forces as individuals search for identity, meaning, and ontological security (Meyer, Citation2009; Nesse, Citation2001). It should not, therefore, be too difficult to break out of the organizational mindset and study commitment where there is no organization. This is becoming more important to consider given the aforementioned changes in the workplace and how organization is receding in importance and may not be relevant in many cases (Cappelli, Citation2000; Connelly & Gallagher, Citation2004).

For many alternative or non-standard ways of working there is neither employment nor “organization” in the traditional sense. In most cases this has been replaced with professional contracts and traditional benefits or compensation has been replaced by freedom, mobility, and autonomy. As sharing and collaborative consumption grow, new organizational structures arise with a particular feature: their main activity is not provided by employees nor outsourcing, but by citizens coordinated throughout the acquisition and distribution of resources or services for a fee or other compensation (Belk, Citation2014). Thus, professional contractors have clients rather than employers, and workers from sharing economies are clients rather than employees which reinforces clients as central workplace characters. In turn, organizations and leaders may become less frequent targets of commitment.

In order to discuss commitment without an organization, we now consider what could replace or substitute for commitment to an organization. This has recently emerged as an interesting question in the context of how managers can promote this substitution to targets as the centrality of the organization wanes (Becker, Citation2016; Meyer, Citation2009). Here we take this further and consider how substitution might manifest itself in situations where there is no organization or employer at all. Individuals still need to commit to someone and something such as clients, work or career. Moreover, because of the sharing character of these new economic models, new targets are also likely to grow, such as commitment to the community.

These possible targets of relevance are highly context dependent and could be many and disparate. Thus, rather than listing them, we posit that looking at the nature and characteristics of the targets, and what they can offer in exchange, may be more fruitful. In situations where there is no organization and no employment, many management systems and Human Resource Management practices such as pay and reward, leadership and other established predictors of commitment simply do not apply. However, many of the psychological needs that organizations address still require fulfilment. We therefore argue that any targets of commitment that replace or substitute for the organization will deliver aspects that are lacking such as social acceptance and status, security – both psychological and financial to some extent, development and other social and psychological needs (Nesse, Citation2001).

In the absence of an organization, individuals may seek to construct their own constellations and networks of commitment targets that replace “the organization” not just as the central target but as a target altogether. This further downplays the instrumental nature of commitment that emphasizes limited alternatives and financial losses and, instead is more in line with an institutional approach whereby institutions aside from employing organizations can offer stability and meaning in a world system or at a micro interpersonal level (Scott, Citation2001, p. 48). Ultimately, the discussion on commitment in the contemporary world and without organizations supports the unidimensional model (Klein et al., Citation2012), which in turn enables the target-neutral approach thereby allowing a broader view of commitment without losing accuracy and specificity.

This discussion, and particularly the idea of substitution between targets, is directly related to concepts of basic human needs, such as needs for belonging, affiliation, esteem, security, uncertainty reduction, and meaning (e.g., Glynn, Citation1998; Nesse, Citation2001; Weick, Citation1995), as the basis for the commitment process. Commitment researchers might thus want to return to fundamental questions “What are the basic human needs?” and “What role do they play in the commitment process?” to help develop their theory of commitment. A recent contribution by Michael & Szekerly (Citationin press) shows the relevance and the potential of drawing on the cognitive processes underpinning the development of commitments from childhood. Although there is at this time no agreement among them, some theories of basic human needs have already been developed by social psychologists (Pittman & Zeigler, Citation2007) that might help in this conceptual work.

Research path 9

Future research will need to be cognizant of and further investigate new models of work without an organization as it is plausible that individuals will organize constellations of targets that substitute for the organization and will play a similar role to what has been expected of organizations, in terms of satisfaction of basic human needs.

How can categories of commitments to different targets be developed?

As discussed in the previous sections, the simultaneous commitment to multiple targets has long been recognized, but becomes more important in the contemporary workplace. Klein et al. (Citation2012) noted the need to develop a parsimonious framework for organizing the numerous potential workplace commitment targets. Because of the disjointed nature of the commitment literature, with commitment to different targets studied in different areas using different definitions and measures of commitment (e.g., goal commitment by motivation researchers, escalation of commitment in the decision-making literature, career commitment in the careers literature, etc.), our understanding is insufficient of how commitments to different targets are similar or different from each other, how those multiple commitments are interrelated, and consequently, when they are complementary or competing. Without understanding these critical issues, it is difficult to explain or predict what commitments are most desirable in what contexts, an increasingly important issue for organizations and managers in a changing workplace.

One approach to developing such a typology would be to focus on the objective or phenomenological differences between possible commitment targets. For example some targets are social or interpersonal in nature (e.g., supervisors and co-workers) whereas others are intrapersonal (e.g., ideas, career, and decisions). This distinction could be broadened into a “levels of analysis” perspective (e.g., targets that are intra-individual, interpersonal, groups or units, and organizations). Another relatively objective basis for distinguishing commitment targets is the level of abstraction of the target (Becker et al., Citation2009). A very concrete target (e.g., a goal to finish a report by a deadline) is very specific in terms of what is required whereas more abstract commitments (e.g., to sustainability) are less constraining. The advantage of focusing on objective target features (vs. perceptual features) is that a given target remains relatively fixed on the chosen continua. Yet some targets would remain difficult to categorize. For example, goals can be set at different levels of analysis and span the full spectrum of concreteness, as any particular goal could be very concrete or very abstract. A target like the employing organization can similarly span the entire range of abstraction, depending on the size and structure of the organization. Thus, relying on objective phenomenological differences alone does not sufficiently group or differentiate commitment targets.

A second approach to developing a typology of commitment targets would be to embrace the fact that the different commitment targets may sometimes be congruent and at other times or in other contexts potentially conflicting. Such a typology would likely be based on perceptual target attributes (e.g., salience, psychological distance, and value congruence). This type of framework would allow for the categorization of commitment targets (e.g., what targets are likely to be co-activated) in a particular context (Klein, Solinger, & Duflot, Citation2017), but would not provide a constant set of target categories, as the same target could be perceived differently depending on the situation, individual, or point in time. For example, supervisor commitment could be categorized very differently (e.g., closely aligned with either the organization or the team) depending on the job tasks and structure, individual differences, and the dyadic relationship. Further conceptual development around the formation, maintenance, and dissipation of multiple commitments and their interrelationships, over time is needed to inform such a typology.

A final approach to developing a typology of commitment targets would be to focus on the differences in the operation of commitment across targets. Klein et al. (Citation2012) presented a target-neutral model and definition of commitment but recognized that commitments to different targets may serve different purposes for individuals. In addition, although presenting general categories of commitment antecedents and outcomes, they indicated that variation in the relative importance of those general categories (Aquino & Reed, Citation2002) as well as differences in the specific antecedents or outcomes within those general categories could be expected.

In recent years, commitment scholars have started to study multiple commitment targets in various combinations, however there is simply not sufficient data in the extant literature at this time to draw definitive conclusions regarding specific similarities and differences in the operation of commitment across targets. Future research examining multiple commitments in a comparable manner is a potential avenue for developing a commitment target typology from a grounded perspective, but will require a large number of future studies across a variety of samples and contexts. Ironically, having a typology in place would make this research much more efficient, as it could instead be designed in a confirmatory manner.

Research path 10

A commitment target typology is needed but new theory, or more research evidence from studies examining multiple commitments in a comparable manner, is required to better understand what target commitments operate similarly and tend to be co-activated.

Conclusion

Decades of commitment research has taken place and despite substantial advances the field is currently making towards understanding workplace commitment, the field has been separated and divided in its fundamental understandings. We feel the time is ripe to consolidate some of the understanding on commitment in contemporary workplaces. This position paper has aimed to provide (1) an overview of the areas where we are making progress and (2) indicate where future research and practice should focus on next.

The areas in which progress is made include our understanding of multiple workplace commitments, especially based on various TCM mindsets. However, given the nature of cross-boundary work settings which were discussed in this paper, research on workplace commitment needs to clearly define and select multiple relevant commitment targets. Rather than focussing on the most researched target, the employing organization, it is necessary to include a set of targets most central and relevant to the specific work setting. Latent profile analysis was highlighted as one way to analyse the combination as well as the complex interactions between and across different commitment targets.

A broad range of areas in which research needs to be conducted are presented and discussed in this paper. In general, we seem to have developed our understanding of the dynamics of workplace commitment in cross-boundary workplaces further than understanding temporary work settings. Particularly research on temporary work settings that stretches beyond temporary versus permanent contracts is rare. The initiatives in this paper in the direction of outlining types of temporary work settings is a first step into a systematic study and understanding the complexities and effects of temporary work relations on workplace commitment.

Looking ahead further, a substantial area for future research in the workplace commitment field is to enhance our understanding of how multiple commitments work together. Many of the Research Paths agree steps need to be made into research on how commitments are substituted, conflicting, complementary or working in synergy. An additional area of interest for further research is the potential adverse consequences caused by commitment conflict (Klein et al., Citation2016), as we know that the perception of incompatible demands in the workplace leads to stress in the case of role conflict (Crawford, LePine, & Rich, Citation2010) as well as identity conflict (Fiol, Citation2002).

A final direction for research is looking ahead in ways that work may further change, for this will affect how workers develop attachments to work, including workplace commitments. In this paper, we have explored how temporary and cross-boundary work settings may change commitment and extended this to commitment in workplaces without an organization. For the future of workplace commitment, it is the challenge to persist to integrate research and practice, for this is how studies on workplace commitment can potentially make a positive difference in tomorrow’s workplace.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1991). Attachments and other affectional bonds across the life cycle. In C. M. Parkes, J. S. Hinde, & P. Marris (Eds.), Attachment across the life cycle. New York: Routledge.

- Allen, N. J. (2016). Commitment as a multidimensional construct. In J. P. Meyer (Ed.), The handbook of employee commitment (pp. 28–42). Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781784711740

- Aquino, K., & Reed, I. I. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1423.

- Ashford, S. J., George, E., & Blatt, R. (2007). 2 old assumptions, new work: The opportunities and challenges of research on nonstandard employment. The Academy of Management Annals, 1, 65–117.

- Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34, 325–374.

- Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20–39.

- Askew, K., Taing, M. U., & Johnson, R. E. (2013). The effects of commitment to multiple foci: An analysis of relative influence and interactions. Journal Human Performance, 26, 171–190.

- Aubé, C., & Rousseau, V. (2005). Team goal commitment and team effectiveness: The role of task interdependence and supportive s. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 9, 189–204.

- Bakker, A. B., Albrecht, S. L., & Leiter, M. P. (2011). Key questions regarding work engagement. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20, 4–28.

- Baruch, Y. (1998). The rise and fall of organizational commitment. Human System Management, 17, 135–143.

- Baruch, Y., & Winkelmann–Gleed, A. (2002). Multiple commitments: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation in a community health service trust. British Journal of Management, 13, 337–357.

- Becker, T. E. (1992). Foci and bases of commitment – Are they distinctions worth making. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 232–244.

- Becker, T. E., & Billings, R. S. (1993). Profiles of commitment – An empirical test. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 14, 177–190.

- Becker, T. E. (2016). Multiple foci of workplace commitments. In J. P. Meyer (Ed.), Handbook of employee commitment. Edward Elgar. doi:10.4337/9781784711740

- Becker, T. E., Kernan, M. C., Clark, K. D., & Klein, H. J. (2015). Dual commitments to organizations and professions: Different motivational pathways to productivity. Journal of Management. Published online. doi:10.1177/0149206315602532

- Becker, T. E., Klein, H. J., & Meyer, J. P. (2009). Commitment in organizations: Accumulated wisdom and new directions for workplace commitments. In H. J. Klein, T. E. Becker, & J. P. Meyer (Eds.), Commitment in organizations: Accumulated wisdom and new directions (pp. 419–452). New York: Routledge.

- Belk, R. (2014). You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. Journal of Business Research, 67, 1595–1600.

- Bentein, K., Vandenberg, R. J., Vandenberghe, C., & Stinglhamber, F. (2005). The role of change in the relationship between commitment and turnover: A latent growth modeling approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 468–482.

- Biggs, D., & Swailes, S. (2006). Relations, commitment and satisfaction in agency workers and permanent workers. Employee Relations, 28, 130–143.

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34(2), 193-206. doi:10.1111/soin.1964.34.issue-2

- Breitsohl, H., & Ruhle, S. A. (2013). Residual affective commitment to organizations: Concept, causes and consequences. Human Resource Management Review, 23, 161–173.

- Breitsohl, H., & Ruhle, S. A. (2016). The end is the beginning – The role of residual affective commitment in former interns’ intention to return and word-of-mouth. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25, 833–848.

- Burke, C. M., & Morley, M. J. (2016). On temporary organizations: A review, synthesis and research agenda. Human Relation, 69, 1235–1258.

- Campbell, I., & Burgess, J. (2001). Casual employment in Australia and temporary employment in Europe: Developing a cross-national comparison. Work, Employment and Society, 15, 171–184.

- Cappelli, P. (2000). Managing without commitment. Organizational Dynamics, 28, 11–24.

- Cappelli, P., & Keller, J. R. (2013). Classifying work in the new economy. Academy of Management Review, 38, 575–596.

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283.

- Chambel, M. J., Sobral, F., Espada, M., & Curral, L. (2013). Training, exhaustion, and commitment of temporary agency workers: A test of employability perceptions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24, 15–30.

- Chen, Y. C., Chi, S. C. S., & Friedman, R. (2013). Do more hats bring more benefits? Exploring the impact of dual organizational identification on work-related attitudes and performance. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86, 417–434.

- Cohen, A. (2003). Multiple commitments in the workplace: An integrative approach. Psychology Press.

- Cohen, A. (2007). Commitment before and after: An evaluation and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 17, 336–354.

- Colarelli, S. M, & Bishop, R. C. (1990). Career commitment: functions, correlates, and management. Group & Organization Studies, 15(2), 158-176. doi: 10.1177/105960119001500203

- Connelly, C. E., & Gallagher, D. G. (2004). Emerging trends in contingent work research. Journal of Management, 30, 959–983.

- Cooper, J. T., Stanley, L. J., Klein, H. J., & Tenhiälä, A. (2016). Profiles of commitment in standard and fixed-term employment arrangements: Implications of work outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25, 149–165.

- Cooper-Hakim, A., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). The construct of work commitment: Testing an integrative framework. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 241–259.

- Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., & Morrow, P. C. (2006). Organizational and client commitment among contracted employees. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 68, 416–431.

- Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., Morrow, P. C., & Kessler, I. (2006). Serving two organizations: Exploring the employment relationship of contracted employees. Human Resource Management, 45, 561–583.

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 834–848.

- De Cuper, N., & De Witte, H. (2008). Volition and reasons for accepting temporary employment: Associations with attitudes, well-being, and behavioural intentions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 17, 363–387.

- De Jong, J. (2014). Externalization motives and temporary versus permanent employee psychological well-being: A multilevel analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23, 803–815.

- Dick, R, Wagner, U, Stellmacher, J, & Christ, O. (2004). The utility of a broader conceptualization of organizational identification: which aspects really matter?. Journal Of Occupational And Organizational Psychology, 77(2), 171-191. doi: 10.1348/096317904774202135

- Fiol, C. M. (2002). Capitalizing on paradox: The role of language in transforming organizational identities. Organization Science, 13, 653–666.

- Gallagher, D. G., & McLean Parks, J. M. (2001). I pledge thee my troth… contingently: Commitment and the contingent work relationship. Human Resource Management Review, 11, 181–208.

- Gallagher, D. G., & Sverke, M. (2005). Contingent employment contracts: Are existing employment theories still relevant? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 26, 181–203.

- George, J. M., & Jones, G. R. (2000). The role of time in theory and theory building. Journal of Management, 26, 657–684.

- Glynn, M. A. (1998). Individuals’ need for organizational identification (nOID): Speculations on individual differences in the propensity to identify. In D. A. Whetten & P. C. Godfrey (Eds.), Identity in organizations: Building theory through conversations (pp. 238–244). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Golden-Biddle, K., & Rao, H. (1997). Breaches in the boardroom: Organizational identity and conflicts of commitment in a non-profit organization. Organization Science, 8, 593–611.

- Gouldner, A. W. (1957). Cosmopolitans and locals: Toward an analysis of latent social roles. I. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2, 281–306.

- Goulet, L. R., & Singh, P. (2002). Career commitment: A reexamination and an extension. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 61, 73–91.

- Greenwood, R., & Empson, L. (2003). The professional partnership: Relic or exemplary form of governance? Organization Studies, 24, 909–933.

- Haden, S. S. P., Caruth, D. L., & Oyler, J. D. (2011). Temporary and permanent employment in modern organizations. Journal of Management Research, 11, 145–158.

- Johnson, R. E., Chang, C.-H., & Yang, L. (2010). Commitment and motivation at work: The relevance of employee identity and regulatory focus. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 226–245.

- Kabins, A. H., Xu, X., Bergman, M. E., Berry, C. M., & Willson, V. L. (2016). A profile of profiles: A meta-analysis of the nomological net of commitment profiles. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 101, 881–904.

- Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74, 1–22.

- Kam, C., Morin, A. J., Meyer, J. P., & Topolnytsky, L. (2016). Are commitment profiles stable and predictable? A latent transition analysis. Journal of Management, 42, 1462–1490.

- Karmarkar, U. (2004). Will you survive the services revolution? Harvard Business Review, 100–107.

- Klein, H. J., Becker, T., & Meyer, J. (2009). Commitment in organizations: Accumulated wisdom and new directions. Routledge.

- Klein, H. J., Brinsfield, C., Cooper, J., & Molloy, J. (2016). Quondam commitments: An examination of commitments employees no longer have. Academy of Management Discoveries, 3, 331–357.

- Klein, H. J., Cooper, J. T., Molloy, J. C., & Swanson, J. A. (2013). The assessment of commitment: Advantages of a unidimensional, target-free approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 222–238.

- Klein, H. J. (2014). Distinguishing commitment bonds from other attachments in a target-free manner. In J. K. Ford, J. R. Hollenbeck, & A. M. Ryan (Eds.), The nature of work: Advances in psychological theory, methods, and practice (pp. 117–146). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

- Klein, H. J., Molloy, J. C., & Brinsfield, C. T. (2012). Reconceptualizing workplace commitment to redress a stretched construct: Revisiting assumptions and removing confounds. Academy of Management Review, 37, 130–151.

- Klein, H. J., Molloy, J. C., & Cooper, J. T. (2009). Conceptual foundations: Construct definitions and theoretical representations of workplace commitments. In H. J. Klein, T. E. Becker, & J. P. Meyer (Eds.), Commitment in organizations: Accumulated wisdom and new directions (pp. 3–36). New York: Routledge.

- Klein, H. J., & Park, H. (2016). Commitment as a unidimensional construct. In J. P. Meyer (Ed.), The handbook of employee commitment (pp. 15–27). Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781784711740

- Klein, H. J., Solinger, O., & Duflot, V. (2017). Commitment system theory: The dynamic orchestration commitments to multiple targets. Conference on Commitment, Columbus, OH, October 14-15.

- Klein, H. J., Wesson, M. J., Hollenbeck, J. R., Wright, P. M., & DeShon, R. P. (2001). The assessment of goal commitment: A measurement model meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 85, 32–55.

- Kogut, B, & Zander, U. (1996). What firms do? coordination, identity, and learning. Organization Science, 7(5), 502-518. doi: 10.1287/orsc.7.5.502

- Lakatos, I. (1970). Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes. In I. Lakatos & A. Musgrave (Eds), Criticism and the growth of knowledge (pp. 91–196). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lance, C. E., Vandenberg, R. J., & Self, R. M. (2000). Latent growth models of individual change: The case of newcomer adjustment. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 83, 107–140.