ABSTRACT

In an increasingly volatile world, staying employable throughout the course of one’s career has become more important than ever. Whereas adaptability appears to be critical to employability, our understanding of the conditions under which employees’ work-related adaptive behaviour renders them employable in the eyes of their leaders is underdeveloped. By taking a person-supervisor fit approach, we argue that leader-rated employability is contingent on the extent to which employee adaptive behaviours are compatible with leader behaviours that either facilitate or constrain adaptability. Based on the Career Roles Model, we propose that exploration career role enactment is positively associated with leader employability evaluations. Furthermore, drawing on supplementary fit and complementary fit theory, we advance competing hypotheses about the moderating roles of leader opening and closing behaviours in the relationship between exploration career role enactment and employability evaluations. Results of a multi-source field study of Dutch leader-subordinate dyads (N = 292) indicate that exploration career role enactment is positively related to leader-rated employability. Moreover, we find support for our complementary fit hypotheses: employee enactment of exploration career roles is positively related to employability evaluations when leader behaviour complements rather than supplements employee exploratory behaviours. We conclude with theoretical and practical implications.

To stay competitive amidst the rapid socio-economic and technological changes of the 21st century, organizations need to flexibly employ those workers who optimally fit their strategic requirements at any specific point in time (Fugate et al., Citation2021). Hence, it has become paramount for individuals to maintain the ability to gain and retain satisfying employment throughout the course of their careers (Fugate et al., Citation2004). Research on employability seems to have converged on the view that employees are largely responsible for managing their own careers to ensure long-term employability (De Vos et al., Citation2021). Factors like human capital (e.g., education, experience, skills, knowledge, abilities), career competences (Van der Heijde & Van der Heijden, Citation2006) and specific attitudes and dispositions (Hall et al., Citation2018) have all been found to increase individuals’ employability. Overall, this body of work suggests that those who are proactively attuned to fast-changing job requirements and are willing and able to adapt to them are more likely to be employable.

Whereas this agentic view identifies adaptability as key to employability (De Vos et al., Citation2020), the overwhelming emphasis on the employee and individual agency ignores the fact that most employees are embedded in interdependent employment relationships (i.e., with current or future employers). One of the consequences of this employee-centric approach is that employability has primarily been assessed via employee self-ratings (Fugate et al., Citation2021). Research findings thus remain mute as to whether and when employee adaptability is positively related to employability in the eyes of their direct supervisors or employers. Yet, whether an individual is employable or not is not only a matter of self-perception, but also hinges on the evaluations of those making hiring, firing or promotion decisions. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the conditions under which employee adaptable behaviour helps them be seen as more employable by relevant others (i.e., employers or their representatives).

In this research, we investigate the relationship between employee adaptable behaviour and leader-ratings of employability. We do so by building on the Career Roles Model (Hoekstra, Citation2011), which contends that people differ in their willingness and ability to act in ways that address the changing demands in their environment (i.e., the extent to which they are adaptable). The model conceptualizes adaptability in terms of a cluster of longer-term broad patterns of behaviour (i.e., exploration career roles) geared towards developing new skills, knowledge and abilities that employees can proactively use to shape their careers. We propose that the extent to which employees showcase adaptability by enacting exploration career roles (focused on seeking out new challenges and experiences, trying new things and taking calculated risks to expand skills) is positively related to leader-rated employability.

Employability evaluations do, however, not only depend on individual employee behaviours, but are also contingent on factors within the immediate work context (Forrier et al., Citation2018; Fugate et al., Citation2021) such as HRM practices (e.g., opportunities for learning and development; Van der Heijden et al., Citation2009) or leader behaviours (Van der Heijde & Van der Heijden, Citation2014). Indeed, perceptions of the likelihood that employees will be able to find or retain a job will depend not only on individual behaviours, but also on the extent to which these behaviours are seen to fit a particular job, leader or organization (Epitropaki et al., Citation2021). We therefore take a person-supervisor fit perspective and propose that leader employability evaluations are contingent on the extent to which employee work-related adaptive behaviours are compatible with leader behaviours that either facilitate or constrain adaptability. Specifically, we investigate leader-employee (mis)fit effects by exploring whether the two types of behaviours associated with ambidextrous leadership (Rosing et al., Citation2011), namely leader opening (aimed at fostering explorative behaviour) and closing behaviours (aimed at fostering exploitative behaviour) interact with exploration career role enactment in predicting leader-rated employability. Using both supplementary fit and complementary fit theory (Muchinsky & Monahan, Citation1987), we test competing hypotheses about the moderating roles of leader opening and closing behaviour in the relationship between exploration career role enactment and leader-rated employability.

We deem our research valuable for several reasons. First, it takes a sorely missing contextualized approach in the study of employability (Forrier et al., Citation2018) by focusing on the interaction between employee behaviours signalling adaptability (i.e., exploration career role enactment) and leader behaviours (i.e., opening and closing behaviours) in co-determining leader-rated employability. In doing so, it underlines the value of incorporating the Career Roles Model, which views adaptability in terms of broader longer-term patterns of behaviour employees use to proactively shape their careers, in the study of employability. Additionally, the role that leader behaviour may play in co-determining leader-rated employability has rarely been scrutinized (Fugate et al., Citation2021), despite being one of the most critical elements in employees’ direct work context (Oc, Citation2018; Yukl, Citation2019). Second, it highlights the potential broader value of taking a person-supervisor fit perspective in the study of employability above and beyond the recently studied (mis)fits in perceived quality of leader-member exchange (Epitropaki et al., Citation2021) or age dissimilarities (Scholarios & Van der Heijden, Citation2021). Ambidextrous leadership (Rosing et al., Citation2011) provides a particularly useful lens since it is a leadership style marked by a behavioural repertoire that either promotes or constrains employee exploration. Third, by focusing on leader-rated employability it moves beyond the currently dominant employee perspective (Fugate et al., Citation2021) in the study of employability.

Leader evaluations of employability

Employability has traditionally been conceptualized as one’s ability to gain and retain satisfying employment throughout the course of one’s career (Fugate et al., Citation2004). A vast majority of research has taken the employee’s perspective and has measured employability via self-reports (see Fugate et al., Citation2021 for a review). Clearly, a focus on how employees perceive their own employability has yielded valuable insights. Yet, it has also limited our understanding since employees are embedded in interdependent employment relationships (i.e., with current or future employers). This implies that their employability is not entirely under their control and that their “chances of a job in the internal and/or external labour market” (Forrier & Sels, Citation2003, p. 106; i.e., their employability) are also contingent on their (current or future) employers. Therefore, it is critical to also consider employers’ (or their representatives’) perceptions of individuals’ employability (cf. Fugate et al., Citation2021).

A focus on leader evaluations of employability is important for several reasons (cf. Guilbert et al., Citation2016). First, leaders – acting as representatives of the employer – usually decide internally on who is hired, retained, promoted or fired and can be instrumental in affecting employees’ chances on the external labour market by serving as referees (Yukl, Citation2019). Second, leaders are internal gatekeepers who either facilitate or hinder access to a variety of organizational resources (Spurk et al., Citation2019) and growth opportunities (Kraimer et al., Citation2011; Sparrowe & Liden, Citation2005) such as access to mentorship and training which have all been positively related to career success (Bozionelos et al., Citation2016, Citation2020). Third, although rare, the few extant studies that have tapped into leader-ratings of subordinate employability suggest that they are consequential for employability-related outcomes. Leader-ratings of subordinate employability have been associated with subjective and objective career success such as salary and promotions (Bozionelos et al., Citation2016; Epitropaki et al., Citation2021), job performance (Bozionelos et al., Citation2020) and job satisfaction (Marzec, Citation2019). Therefore, in this research we will explore factors underlying leaders’ evaluations of subordinate employability.

The career roles model and exploration career role enactment

The Career Roles Model (Hoekstra, Citation2011) is a content model of career development rooted in process-oriented protean career theories (Sullivan & Arthur, Citation2006) which assumes that individuals need to proactively shape their careers and flexibly adapt to external circumstances to ensure continued employability. The model takes a lifespan career development perspective and sees successful career development as a continuous process of adaptation whereby individuals integrate their personal motives with organizational needs (Savickas et al., Citation2009). Importantly, individuals differ in their willingness and ability to act in ways that address the changing demands in their work environment.

The basic premise of the model is that the work environment has become increasingly dynamic as organizations need to continuously adapt and innovate to face rapid socio-economic and technological changes. Consequently, organizations rely on employees to initiate change and adapt to new situations rather than having them perform strictly defined tasks (Grant & Parker, Citation2009). Hence, contemporary careers are difficult to define by how employees perform on a fixed bundle of tasks. Rather, they need to flexibly master a series of diverse and complex tasks which requires them to adopt various work roles throughout their careers. Work roles are broader than tasks and imply a more dynamic and situational use of skills. They consist of a combination of tasks, processes and responsibilities that continuously evolve in response to changing needs and opportunities (Huckvale & Ould, Citation1995). Over time, work roles can solidify into career roles which are broad categories of behaviour independent of specific jobs and levels of functioning. Career roles are “stable and repetitive patterns of functioning in the work context” (De Jong et al., Citation2019, p. 2) that “the person identifies with and is identified with” (Hoekstra, Citation2011, p. 163). They form the building blocks of individual careers and are potentially attainable in most jobs with some degree of autonomy. Individuals tend to have certain career role preferences (i.e., they will gravitate towards certain types of roles based on individual motives) and may (but do not have to) identify with several career roles at the same time (Jansen et al., Citation2006). Importantly, career roles are enacted: individuals perform behaviours characteristic of these roles (De Jong et al., Citation2019; Hoekstra, Citation2011).

The model identifies an overarching cluster of career roles, namely, exploration career roles (a combination of the expert, guide and inspirer roles) which embody adaptability as they focus on developing new skills, knowledge and abilities (Hoekstra, Citation2011). These roles share a common core of “creating variety in experience” (Mom et al., Citation2007, p. 912). Individuals drawn to them adopt a long-term orientation (Tushman & O’Reilly, Citation1996) and engage in behaviours focused on “searching for, discovering, creating, and experimenting with new opportunities” (Mom et al., Citation2007, p. 910) across various domains. This might involve seeking out new challenges and experiences, trying new things and taking calculated risks to expand one’s skills and knowledge base. For instance, those enacting the expert role are eager to explore, solve problems, experiment and innovate (McGrath, Citation2001), generate new insights and learn (Hoekstra, Citation2011; Rosing & Zacher, Citation2016). Those enacting the guide role collectively explore potential avenues for change by openly asking questions and showing support (Hoekstra, Citation2011; Junni et al., Citation2013). Finally, those enacting the inspirer role initiate change (often without a formal position), search for new organizational strategies, norms, routines and inspire others to follow them (De Jong et al., Citation2019; Hoekstra, Citation2011). In sum, individuals enacting exploration roles target variability, exploration and change and showcase adaptability by focusing on developing new skills, knowledge and abilities.

Employability evaluations as a function of exploration career role enactment

The way employees behave is likely to be noticed by their leaders and to influence the impressions they form of them. Indeed, impression formation underpins any social interaction, as individuals need to anticipate what others are like and likely to do (Moskowitz & Gill, Citation2013). Leaders are no different: they categorize employees and their behaviour, form inferences about their qualities and the causes of their actions, generate attributions that explain their behaviour and make predictions about what these employees are like and likely to do. These impressions are largely based on employees’ visible characteristics or behaviours along with the interpretation of information provided by third parties (e.g., what colleagues say about an individual). Hence, the extent to which employees enact exploration career roles is likely to not only shape leaders’ overall impression of them, but also their employability perceptions. The proactivity and exploration typical of exploration career role enactment is likely to render these employees highly visible as stimuli that are new, unknown and different have been shown to stand out and attract attention (Itti & Baldi, Citation2009; James, Citation1890). Thus, explorative behaviours are likely to attract leaders’ attention and affect the impressions they form about subordinate employability.

Additionally, exploration roles embody the types of behaviours currently seen as desirable in organizations (Parker & Bindl, Citation2016); they combine proactivity, flexibility and adaptability (Lent & Brown, Citation2013) with a predilection for tasks that are new, complex and ill-defined (Savickas et al., Citation2009). Indeed, research suggests that organizations count on these types of self-directed behaviours to drive innovation and foster adaptability (Griffin et al., Citation2007) and managers across the world deem resourcefulness, initiating and managing change, and building relationships to be the competencies most important for success (Gentry & Sparks, Citation2012; Hogan et al., Citation2013). Behaviours characteristic of exploratory roles, such as taking initiative, solving problems, suggesting ways to improve things, seizing opportunities and creating meaningful change, signal that employees are willing and able to adapt, learn and act in ways that address the changing demands in their work environment. As such, research shows that managers view employees who are adaptable and willing to learn more positively and provide access to internal growth opportunities, such as high potential training programs (Dries et al., Citation2012). Moreover, explorative behaviour has been positively linked to innovation and knowledge creation (Tuncdogan et al., Citation2015), which have been shown to positively impact promotions and salary increases (Seibert et al., Citation2001), suggesting that leaders deem these individuals employable.

Finally, those enacting exploration roles have been found to invest in building larger and more diverse networks (Morrison, Citation2002), to expend energy on building support among key interest groups (Jelinek & Schoonhoven, Citation1990) and to persuade others to implement new solutions (Dutton & Ashford, Citation1993). Together, these activities enable these employees to pursue higher pay, internal promotions or a move to other organizations (Lee & Meyer-Doyle, Citation2017) as they contribute to building social capital necessary for career success (for a meta-analysis see Ng et al., Citation2005). Since leaders form impressions of their employees based on both employee behaviour and on third party assessments (i.e., the social capital built internally), this line of reasoning further supports our expectation that exploration career role enactment should positively impact leader-rated employability. Thus, we posit:

Hypothesis 1:

Exploration career role enactment is positively associated with leader-rated employability.

Leader opening and closing behaviours as moderators of the relationship between exploration career role enactment and employability evaluations

Employee work-related behaviour signalling adaptability affects their chances of becoming and staying employable (De Vos et al., Citation2021). Yet, whether these behaviours are deemed to be appropriate and desirable by their leaders is likely to also be contingent on the extent to which they are seen to fit a particular job, organization or leader (Epitropaki et al., Citation2021). Assessments of a persons’ employability do not take place in a social vacuum. Rather, they are always embedded in a context which affects how employee behaviours are perceived and interpreted. One particularly important, yet surprisingly underdeveloped approach in understanding how adaptive employee behaviours may affect leader-rated employability is a focus on the extent to which employees’ behaviours fit with their supervisors’ behaviour. The leader is one of the most proximal and critical elements in employees’ direct social work context (Johns, Citation2006) and leader-subordinate fit has been shown to influence leader decisions on promotions and salary (Wayne et al., Citation1999) as well as performance ratings (Fuller et al., Citation2012). Moreover, some preliminary evidence suggests that the level of (mis)fit between leaders and employees, whether that be (dis)agreements on the quality of leader-member exchange (Epitropaki et al., Citation2021) or supervisor-employee age (dis)similarity (Scholarios & Van der Heijden, Citation2021) substantially impacts leader-rated employability and objective career outcomes (promotions and salary). Thus, exploring how the behavioural fit between employees and their leaders may impact employability evaluations seems valuable.

In this research, we take an ambidextrous leadership lens (Rosing et al., Citation2011) since the behaviours associated with this leadership style aim to either facilitate or constrain employee adaptable behaviour and are thus, more or less compatible with exploration career role enactment. Ambidextrous leadership theory builds on the notion that organizations need to develop ambidexterity at the organizational level in order to thrive (March, Citation1991). This implies a need to simultaneously explore new opportunities (i.e., by experimenting and searching for new knowledge) while exploiting existing competencies (i.e., by refining existing knowledge). Indeed, ample research has shown that organizational ambidexterity underpins organizational adaptation, learning, innovation and long-term success (Gupta et al., Citation2006; Junni et al., Citation2013). Within organizations, both roles that focus on exploration (required for innovation and new opportunity development) and roles that focus on exploitation (required for consistency and standardization) need to be performed (Junni et al., Citation2013). Ambidextrous leadership is a leadership style that aims to “foster both explorative and exploitative behaviours in followers by increasing or reducing variance in their behaviour” (Rosing et al., Citation2011, p. 957). To do so, leaders can display two different types of behaviours: opening and closing behaviours (Mascareño et al., Citation2021; Rosing et al., Citation2011). Leader opening behaviours aim to stimulate exploratory behaviour by providing freedom for independent thinking and support in developing new approaches. They include encouraging experimentation, challenging established routines and motivating to take risks. In contrast, leader closing behaviours aim to stimulate exploitative behaviours by restricting freedom and focusing on efficiency. They include monitoring goal achievement, sanctioning errors and taking corrective actions. Whereas in theory, leaders should strive for both exploration and exploitation and engage in both opening and closing behaviours (Rosing et al., Citation2011), in reality, this is not necessarily feasible due to competing demands on limited resources (Gupta et al., Citation2006). Moreover, most leaders tend to emphasize the one over the other depending on the context or their own innate preferences (Havermans et al., Citation2015; Tuncdogan et al., Citation2015).

We take a person-supervisor (P-S) fit perspective (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005) and explore to what extent the level of mis(fit) between employee enactment of exploration career roles and leader opening and closing behaviours impacts leader-rated employability. Specifically, we investigate whether leader opening and closing behaviours interact with exploration career role enactment in predicting leader-rated employability. The basic person-supervisor fit paradigm (Muchinsky & Monahan, Citation1987) suggests that leaders’ perceptions of subordinate employability hinge on the extent to which employee and leader behaviours are compatible. Yet, the meaning of compatibility differs depending on which of the two major person-supervisor fit theoretical traditions (supplementary fit or complementary fit) one subscribes to (Cable & Edwards, Citation2004; Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005). To date, the majority of research on person-supervisor fit has taken a supplementary fit perspective, yet there is no reason to believe that either the supplementary or complementary fit traditions are inherently a superior choice in predicting employability perceptions. Therefore, we advance two competing sets of hypotheses rooted in supplementary and complementary fit theories.

First, in the supplementary fit tradition, compatibility occurs if the employee and the supervisor share similar or matching characteristics (Muchinsky & Monahan, Citation1987). Supplementary fit is conceptualized as leader-subordinate congruence in, for instance, goals (Witt, Citation1998), values (Byza et al., Citation2019) or personality (Xu et al., Citation2019). Theoretically, congruence should positively affect leader or employee attitudes and behaviours because people are more attracted to and inclined to like others which are similar to themselves (i.e., similarity-attraction paradigm; Cable & Edwards, Citation2004). Thus, leaders and subordinates who are similar are more likely to understand and appreciate each other, have higher levels of trust, better communication and more rewarding interpersonal relationships (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005). In support of this tradition, previous research suggests that leader-subordinate similarities positively influence outcomes such as leader decisions on promotions and salary (Wayne et al., Citation1999), performance ratings (Fuller et al., Citation2012) and perceptions of relationship quality (Zhang et al., Citation2012). Consequently, leader perceptions of subordinate employability should be particularly positive if employee and leader behaviours are highly congruent. That is, leader perceptions of subordinate employability should be particularly positive if employees exhibit high levels of exploration career role enactment and leaders display high levels of opening behaviours, as both behaviours imply searching for, discovering and experimenting with new opportunities. In contrast, congruence would be low when employees engage in high levels of exploration career role enactment whilst leaders display high levels of closing behaviours. Leaders displaying closing behaviours focus on promoting exploitative behaviours by establishing work routines and rule adherence. Thus, employees enacting exploration career roles may be seen as acting contrary to leader expectations or even as ignoring leader requirements, which is likely to result in less positive employability ratings. In sum, based on supplementary fit theory we posit that:

Hypothesis 2a.

Exploration career role enactment will be more strongly positively related to leader-rated employability to the extent that leaders display opening behaviours.

Hypothesis 3a.

Exploration career role enactment will be less strongly positively related to leader-rated employability to the extent that leaders display closing behaviours.

In contrast, from a complementary fit perspective, compatibility is achieved if employees and leaders have complementary attributes whereby the strengths of the one compensate for the weaknesses of the other (Muchinsky & Monahan, Citation1987). The premise here is that complementarity leads to a mutually fulfilling relationship which leads to positive evaluations of each other (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005). Although research from a complementary fit perspective is limited, studies indicate that leader-subordinate complementarity positively influences helping and voice behaviours (Kim et al., Citation2017), perceptions of leader openness and receptivity (Grant et al., Citation2011) and leader-member exchange (Marstand et al., Citation2017). This perspective acknowledges that organizations are wrought with inherent tensions (e.g., pursuing exploitation vs. exploration; Gupta et al., Citation2006) and that these tensions can be resolved by having different entities compensate for each others’ strengths and weaknesses. Thus, leader perceptions of subordinate employability should be particularly positive if employee and leader behaviours are complementary. Leader assessments of subordinate employability should be particularly positive if employees exhibit high levels of exploration career role enactment and leaders display high levels of closing behaviours. Employees enacting exploration career roles (focused on discovery and experimentation) could compensate for high levels of leader closing behaviours (focused on efficiency and standardization). Indeed, given the inherent tension between engaging in explorative and exploitative behaviours simultaneously, a complementary relationship where the employee engages in exploration whereas the leader engages in exploitation is likely to be seen as beneficial for the organization at large and translate into positive employability evaluations. Similarly, high complementarity would be achieved when employees exhibit high levels of exploration career role enactment and leaders are weak in displaying opening behaviours. These leaders are also likely to see the value added by adaptable employees who flexibly search for solutions, especially since they are not explicitly encouraged to do so; which should also result in more positive employability perceptions. In contrast, when both employees and leaders are focused on exploration there is little complementarity that can be achieved and leaders should be less likely to see the unique value added by these employees (after all they simply do what is required of them), which should be reflected in lower employability evaluations. In sum, based on the complementary fit perspective, we posit that:

Hypothesis 2b.

Exploration career role enactment will be less strongly positively related to leader-rated employability to the extent that leaders display opening behaviours.

Hypothesis 3b.

Exploration career role enactment will be more strongly positively related to leader-rated employability to the extent that leaders display closing behaviours.

Method

Sample

We collected data from 292 leader-subordinate dyads working in a variety of Dutch for-profit and non-profit organizations (e.g., retail sector, financial institutions, educational and healthcare organizations). Among the subordinates, 64% identified as female, their mean age was 37 years (SD = 13.37) and the majority held either a post-secondary vocational education degree (32.3%) or a bachelor degree or higher (43.3%). On average, subordinates had 17.42 years (SD = 12.46) of work experience and the majority had been reporting to their current leader for more than 2 years (54.3%). Among the leaders, 48.8% identified as female, their mean age was 44.59 years (SD = 11.16) and they had an average work experience of 23.93 years (SD = 10.64). The majority of the leaders held either a post-secondary vocational education degree (26.8%) or a bachelor degree or higher (62.2%).

Procedure

Data were collected as part of a study on supervisor-subordinate relationships and work outcomes. Respondents were approached at work, which in most cases, implied that research assistants visited local organizations and asked employees and/or their supervisors for their cooperation. In other cases, research assistants (first) called or emailed potential respondents, or relied on personal contacts for recruitment. Supervisors and employees interested in participating were provided with separate envelopes containing paper-and-pencil questionnaires with identical numerical codes – which allowed us to match supervisor-employee data. Respondents were asked to complete the questionnaires individually without consulting their colleagues, subordinates or supervisors, and to return them in a separate sealed envelope (to reduce response threat). Sealed envelopes were collected by research assistants or returned by mail. Because respondents often completed the study during work hours, we kept the survey short and to the point. All respondents received information on the voluntary nature and confidential character of the study and were asked to sign a consent form. Study approval from the ethics committee of the university was obtained.

Materials

Exploration career role enactment

Exploration career role enactment was assessed via the 15 items of the exploration roles subscales (expert, guide, and inspirer role; 5 items per subscale) of the Career Roles Questionnaire (i.e., CRRQ-30) validated by Hoekstra (Citation2011). Subordinates were asked to indicate the extent to which each of the statements described their personal role at work during the past year (1 = not at all to 7 = very well; α = .87). Sample items are “Analyse a problem that others find complicated”; “Help other people to realize their goals”; and “Invigorate and provoke others with challenging views”.

Leader opening behaviour

Leader opening behaviour was measured with the 7-item scale developed by Zacher and Rosing (Citation2015). Subordinates were asked to rate the extent to which their leader engaged in opening behaviour (1 = not at all applicable to 5 = very applicable; α = .88). Sample items are “My supervisor allows different ways of accomplishing a task” and “My supervisor encourages experimentation with different ideas”.

Leader closing behaviour

Leader closing behaviour was assessed with the 7-item scale developed by Zacher and Rosing (Citation2015). Subordinates were asked to rate the extent to which their leader engaged in closing behaviour (1 = not at all applicable to 5 = very applicable; α = .82). Sample items include “My supervisor monitors and controls goal attainment” and “My supervisor sanctions errors”.

Employability evaluations

Leader-rated employability was assessed via 10 items of the self-perceived employability scale of Rothwell and Arnold (Citation2007) adjusted to fit other-ratings.Footnote1 Leaders were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with statements such as “This employee could easily retrain to make him/herself more employable elsewhere” and “This employee’s personal networks in this organization help him/her in their career” (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; α = .85).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Confirmatory factor analyses

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to confirm the distinctiveness of our measures (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017) and report the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference tests (Satorra & Bentler, Citation2010). We compared our hypothesized four-factor model (exploration career role enactment modelled as a higher order latent variable consisting of three sub-components: expert, guide, and inspirer roles; leader opening behaviour, leader closing behaviour and leader-rated employability) with a three-factor model (by combining leader opening and closing behaviour into one factor) and a one-factor model (by combining all items into one factor). The four-factor solution was superiorFootnote2 (χ2(691) = 1257.26, p < .001, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .86, TLI = .85, SRMR = .07) to the other factor solutions (three-factor solution: χ2(699) = 1984.59, p < .001, RMSEA = .08, CFI = .67, TLI = .66, SRMR = .09; ΔX2 = 446.62 Δdf = 3, p < .001; one-factor solution: χ2(702) = 2863.51, p < .001, RMSEA = .10, CFI = .45, TLI = .42, SRMR = .11; ΔX2 = 1172,89, Δdf = 11, p < .001).

Descriptive statistics

The means, standard deviations, and correlations between the variables are presented in . Exploration career role enactment correlated positively with leader opening (r = .44, p < .01) and closing (r = .16, p < .01) behaviour and, as expected, with leader-rated employability (r = .38, p < .01). Moreover, leader opening behaviour positively correlated with leader closing behaviour (r = .18, p < .01)Footnote3 and with leader-rated employability (r = .44, p < .01).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the study variables.

Hypotheses testing

We conducted a hierarchical regression analysis in which leader-rated employability was predicted by main effect terms for our predictor variables (exploration career role enactment, leader opening and closing behaviour) at Step 1 and the two interaction terms between exploration career role enactment and leader opening and closing behaviour at Step 2. Following Cohen et al. (Citation2003), our predictor variables were centred, and the main effect and interaction terms were based on the centred scores.Footnote4

Step 1 explained a significant proportion of variance in leader evaluations of subordinate employability (see ). In line with Hypothesis 1, exploration career role enactment positively predicted employability evaluations, b = .21, SE = .05, p < .001, 95% CI [.11, .32]. We also found leader opening behaviour to be positively related to employability evaluations, b = .38, SE = .07, p < .001, 95% CI [.25, .50]. More importantly, Step 2 explained an additional significant proportion of variance in leader-rated employability and revealed that the relationship between exploration career role enactment and employability evaluations was moderated by both leader opening (b = −.13, SE = .06, p < .05, 95% CI [−.24, −.02]) and closing behaviour (b = .20, SE = .06, p = .001, 95% CI [.08, .33]).

Table 2. Summary of hierarchical regression analyses predicting employability evaluations.

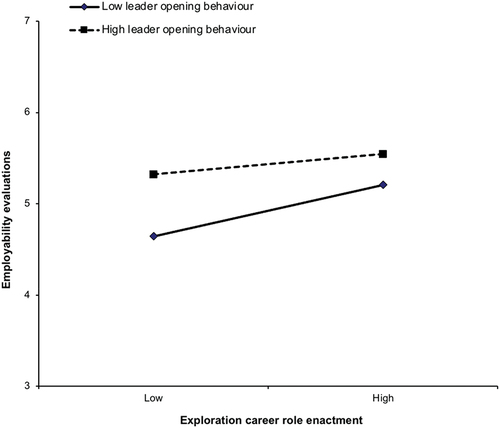

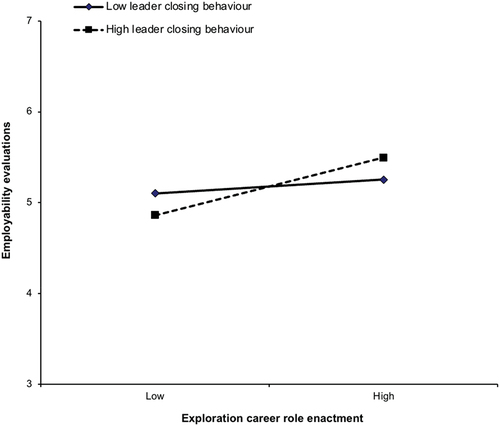

To determine whether these interactions exhibit patterns that either provide support for the supplementary fit (Hypotheses 2a and 3a) or the complementary fit hypotheses (Hypotheses 2b and 3b) we conducted simple slopes analyses. First, in line with the complementary fit Hypothesis 2b, we found that the relationship between exploration career role enactment and employability evaluations was weak and non-significant when leader opening behaviour was high (+1 SD; b = .12, SE = .07, p = .08, 95% CI [−.02, .26]), but positive and significant when leader opening behaviour was low (−1 SD; b =.31, SE = .07, p < .001, 95% CI [.19, .44]; see ). Second, in line with the complementary fit Hypothesis 3b, we found that the relationship between exploration career role enactment and employability evaluations was positive and significant when leader closing behaviour was high (+1 SD; b = .36, SE = .07, p < . 001, 95% CI [.22, .49]), but not when leader closing behaviour was low (−1 SD; b =.08, SE = .07, p = .22, 95% CI [- .05, .21]; see ).Footnote5 In sum, our results provide support for the complementary fit hypotheses rather than for the supplementary fit hypotheses.

Discussion

Given the contemporary societal and organizational changes, employability has become a significant concern not only for individuals, but also for organizations, policy-makers and society at large (De Vos et al., Citation2021). Although we have made significant strides in understanding how individual strengths such as human capital, career competences and specific attitudes and dispositions (Fugate et al., Citation2021) may positively impact subjective employability perceptions and career success, our understanding of what helps individuals be seen as more employable in the eyes of others (e.g., leaders) is largely underdeveloped. In this research, we took a person-supervisor fit perspective (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005) to identify potential antecedents of leader-rated employability by integrating insights from the Career Roles Model (Hoekstra, Citation2011) and ambidextrous leadership (Rosing et al., Citation2011). First, as predicted, we found that the enactment of exploration career roles was positively related to leader evaluations of subordinate employability (Hypothesis 1). Although not predicted a-priori, we also found leader opening behaviours to be positively related to employability evaluations. Second, we showed that the relationship between exploration career role enactment and employability evaluations was moderated by both leader opening and closing behaviours and found support for the complementary fit rather than for the supplementary fit hypotheses. Specifically, subordinate exploration career role enactment was positively related to leader-rated employability when leaders exhibited low levels of opening behaviours (Hypothesis 2b) or when they exhibited high levels of closing behaviours (Hypothesis 3b). Our work furthers our understanding of employability in several ways.

By building on the Career Roles Model, we underscore the value of considering adaptability in terms of broader longer-term behavioural patterns individuals employ to proactively shape their careers. This longer-term behavioural perspective has been sorely missing (Akkermans & Hirschi, Citation2023) as it moves beyond previous research showing that personal strengths, such as skills, abilities, competences and attitudes positively contribute to employability (De Vos et al., Citation2021). These days, a focus on broader behavioural patterns embodying adaptability, like the enactment of career roles, might be even more relevant given that organizations increasingly rely on employees to initiate change and flexibly adapt to changing organizational requirements (Grant & Parker, Citation2009). Our finding that enacting exploration career roles positively impacts leader-rated employability suggests that employees can proactively promote perceptions of employability in others.

Our research also embraces a contextualized approach in the study of employability (De Vos et al., Citation2020; Forrier et al., Citation2018) by focusing on the interaction between employee behaviours and leader behaviours in co-determining leader-rated employability. Surprisingly, although theoretically the importance of various levels of context, ranging from broad and distal levels (e.g., societal, occupational sector level) to more discrete or proximal levels (e.g., immediate task, social and physical context) in co-determining employability has been acknowledged (De Vos et al., Citation2020), the empirical record remains scattered and scant. Whereas some previous work has considered elements of the broader omnibus context (e.g., market structure or national culture; Berntson et al., Citation2006; Holtschlag et al., Citation2013) or the discrete work context (e.g., the job; Erdogan & Bauer, Citation2005) as factors that may interact with individual-level variables in impacting employability, the role that the leader may play has rarely been explored (Fugate et al., Citation2021). This is a substantive oversight given that the leader – being situated psychologically close to the employee – is a critical element in employees’ proximal social context (Johns, Citation2006; Oc, Citation2018) and research indicates that proximal factors affect outcomes more strongly than distal factors (Badura et al., Citation2020; Van Iddekinge et al., Citation2009). Moreover, it has been argued that the leader-follower dyad can be seen as a dynamic interpersonal system and some go as far as to suggest that it is the dyad itself that is the meaningful unit of observation, rather than its individual members (cf. Hofmans et al., Citation2019). From this perspective, leader and follower behaviours are inextricably linked and it has been argued that dyad members, for instance, regulate each other’s emotions and behaviours. Our findings corroborate the idea that including the leader in future research on employability is worthy of attention (Fugate et al., Citation2021) as it may be instrumental in understanding subordinate employability. Clearly, future research would also benefit from investigating how other elements of the broader organizational context (e.g., HRM systems, mobility practices, learning opportunities) or the more discrete work context (e.g., team climate) may interact with individual-level factors in constraining or fostering employability.

This research further underlines the value of taking a person-supervisor fit perspective by showing that leader-ratings of employability are contingent on the extent to which employee behaviour is seen to fit leader behaviour. In doing so, we demonstrate that other types of leader-employee (mis)fit, besides the quality of leader-member exchange (Epitropaki et al., Citation2021) or age dissimilarities (Scholarios & Van der Heijden, Citation2021) significantly impact employability ratings. The finding that exploration career role enactment was only positively related to leader assessments of employability when leaders exhibited low levels of opening behaviours or high levels of closing behaviours points to the importance of complementarity in organizational contexts. Therefore, it appears that both complementary as well as supplementary fit can have positive work outcomes, depending on the context and variables under investigation (Van Vianen, Citation2018). Future research could explore other types of fit (e.g., person-occupation, person-job, person-organization fit) and map out the conditions under which either complementary or supplementary fit might be beneficial for employability over time (Piasentin & Chapman, Citation2006). For instance, complementary fit might be especially important in complex environments that require high levels of agility, adaptability and flexibility, whereas supplementary fit, although potentially beneficial in the short-term, might be harmful in the long-term as development could be hindered by similarity-induced stagnation, tunnel vision or group think.

Our focus on an under-researched leadership style in the context of employability – ambidextrous leadership (Rosing et al., Citation2011) – extends the limited research suggesting that leaders positively influence subordinate employability via supportive and stimulating behaviours, particularly those associated with transformational (Van der Heijde & Van der Heijden, Citation2014; Van der Heijden & Bakker, Citation2011) and servant leadership (Wang et al., Citation2019). Although both the intellectual stimulation facet of transformational leadership and opening leader behaviour target employee exploration and creativity (Bass, Citation1985; Rosing et al., Citation2011), transformational leadership aims to enhance employees’ general motivation to perform beyond expectations (Bass, Citation1985), whereas opening leader behaviour more specifically focuses on stimulating exploration in task performance (Rosing et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, whereas servant leadership is focused on the follower and on identifying conditions that help followers grow and develop (van Dierendonck, Citation2011), ambidextrous leadership is primarily focused on the needs of the organization and aims to increase organizational adaptability, innovation capability and long-term success (Gupta et al., Citation2006). Thus, an ambidextrous leadership lens in the study of employability might be particularly fruitful as it moves beyond transformational and servant leadership and explicitly takes organizational needs into account.

Strengths, limitations and future research

Naturally, our work has both strengths and limitations. One clear strength is that we employed a multi-source design whereby we collected data from nearly 300 leader-subordinate dyads. By using employee-ratings of exploration career role enactment and leader opening and closing behaviour as well as leader-ratings of subordinate employability, the study reduces the risk of common source method variance (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Yet, our study might be criticized for its correlational nature which renders it mute in matters of causality. Nonetheless, we consciously opted for this design because we wanted to understand how employees’ perceptions of their and their leader’s behaviour would impact leaders’ employability assessments, which may have been less feasible in an experimental design. That being said, we strongly encourage future research to test the generalizability of our findings across different methodologies and occupational settings and/or countries. Experimental research would allow for causal relationship analyses and longitudinal studies, based on multi-source ratings, could provide us with insights regarding temporal developments in the interplay between career role enactment, leader behaviour and employability assessments. Career role enactment can be seen as a dynamic process, where individuals are influenced by their environments and, in turn, influence their environments over time (Wille et al., Citation2012). Conceivably, external demands (e.g., organizational strategy, culture, team composition, leadership) might shape the career roles an individual is expected to enact and/or rewarded for enacting, whereas individuals might also shape their environments by enacting certain career roles. Hence, an understanding of how individual career role enactment interacts with environmental demands over time could provide us with valuable insights into the development of long-term employability.

One point worth discussing is our operationalization of employability via leader-ratings. So far, empirical research has overwhelmingly relied on employee self-reports. Undoubtedly, self-perceptions of employability are important and have been shown to predict relevant outcomes (Fugate et al., Citation2021). However, they are also potentially problematic as individuals tend to overestimate their qualities (Lindeman et al., Citation1995). More importantly, whether an individual gains or maintains a job is not entirely under their control but also contingent on their current or potential employer’s assessment of their employability (Fugate et al., Citation2021). Thus, a focus on leader-ratings of employability is valuable. Ultimately, leaders decide internally on who will be hired, retained, promoted or fired (Yukl, Citation2019); control access to a variety of organizational resources necessary for career success (e.g., financial, informational, social; Spurk et al., Citation2019); provide internal growth opportunities (Kraimer et al., Citation2011) and may even influence one’s external employment chances by serving as referees (Yukl, Citation2019). Moreover, the few studies employing leader-ratings of employability have found them to be linked to objective (Bozionelos et al., Citation2016; Epitropaki et al., Citation2021; Van der Heijden et al., Citation2009) and subjective career success (Bozionelos et al., Citation2016). Clearly, reliance on other-reports also has its downsides as leader employability ratings may be affected by bias and noise (Hansbrough et al., Citation2015). Ideally, future research would take a multi-source view on employability (i.e., measuring self- and other-perceptions) especially since the few extant studies including both self- and supervisor-ratings suggest that these perspectives are not always congruent (cf. Epitropaki et al., Citation2021; Van der Heijden et al., Citation2016). Since self-perceived and other-rated employability may differentially impact subjective and objective career outcomes, taking a multi-source view (including not only supervisors but also peers) might not only increase research validity, but also offer insights into how these (dis)agreements uniquely relate to both subjective and objective career success.

Our decision to measure employability via the scale of Rothwell and Arnold (Citation2007) is also worthy of discussion. We purposefully chose this scale both for theoretical and practical reasons. From a theoretical point of view, the scale taps into our conceptualization of employability (i.e., one’s chances of gaining or maintaining a job in the internal and/or external labour market; Forrier & Sels, Citation2003). It thus aligns with our interest in understanding managers’ specific evaluations of their employees’ chances of maintaining their current positions, being internally promoted or gaining employment elsewhere. From a practical point of view, we chose this relatively short (i.e., 10 item) scale to minimize the temporal demands on participating leaders completing the study during work hours. However, we encourage future research to replicate our findings with different scales. For instance, competence-based operationalizations have been proposed, such as the Employability Five-Factor instrument (47 items; Van der Heijde & Van der Heijden, Citation2006) or the Short-Form Employability instrument (22 items; Van der Heijden et al., Citation2018). These scales take a multi-dimensional and somewhat broader perspective on employability (by, for instance, also including items that tap into work-life balance). Future studies could benefit from testing whether the relationship between exploration career role enactment moderated by leader opening and closing behaviours differs across these dimensions (i.e., occupational expertise, anticipation and optimization, personal flexibility, corporate sense and balance). Our reliance on a scale originally developed for self-report to measure other-reports might raise questions regarding its psychometric properties particularly in regard to measurement invariance (i.e., whether self- and other-ratings tap into the same construct; Vandenberg & Lance, Citation2000). Research employing the (Short-Form) Employability Five-Factor instrument (Van der Heijde & Van der Heijden, Citation2006; Van der Heijden et al., Citation2018), specifically validated for self- and other-reports, seems to suggest that congruence between self- and leader-ratings is not necessarily high (Epitropaki et al., Citation2021; Van der Heijden et al., Citation2016). Although this may be caused by bias and noise, employees and leaders may also have different understandings of what employability is all about and rely on different information in their ratings. Hence, future research might benefit from exploring whether and how self- and leader-ratings of employability differ.

Even though our RMSEA and SRMR values do suggest good model fit, the CFI and TLI values of our hypothesized model are slightly below the typically recommended cut-off values of .90 (Marsh et al., Citation2005), which may represent a potential limitation of our study. That being said, there is some current debate within the literature regarding the soundness of relying on conventional cut-off values for goodness of fit indices (Barrett, Citation2007; Greiff & Heene, Citation2017; Marsh et al., Citation2004), given that their values depend on a number of factors, including nuisance parameters (e.g., sample size, size factor loadings of the items, number of items etc.) that are completely unrelated to the actual degree of model misspecification (Greiff & Heene, Citation2017). Indeed, it has been argued that suggestions for cut-off values are based on intuition and experience rather than on statistical justification (see Marsh et al., Citation2004). For instance, it has been shown that the CFI and TLI values are contingent on the number of items per factor, with lower CFI and TLI values as the number of items per factor increases (Heene et al., Citation2011; Kenny & McCoach, Citation2003), which is worth noting in this case given that most of our factors have a sizable number of items (15, 7, 7 and 10 respectively). Nevertheless, model fit could definitely be better, and notwithstanding the current debate, future research might further investigate the measurement of the variables included in this study.

The Career Roles Model (Hoekstra, Citation2011) distinguishes between two types of career roles, namely, exploration and exploitation career roles. Yet, in this research we opted to only focus on exploration career roles. We chose to do so for several reasons. First, we were interested in understanding whether and how employee adaptable behaviour is valued by their leaders. To this end, an exclusive focus on exploratory career roles seemed warranted given that the behaviours associated with them embody adaptability whereas the behaviours associated with exploitation career roles do not. Indeed, although critical from an organizational point of view, exploitative behaviours (e.g., proficiently executing assigned routine tasks and using existing strengths and competencies) signal a need for stability, routines and consistency rather than a will and ability to adapt to changing organizational needs (Hoekstra, Citation2011). Second, employees who only dutifully operate within the confines of their assigned tasks merely do what they were hired to do. Whereas this may influence leader evaluations of current performance (which are only weakly related to career success; cf. Baruch & Bozionelos, Citation2011), the broader literature provides little theoretical foundation or empirical evidence suggesting an expected relationship between exploitation career role enactment and leader ratings of future career potential (an idea also corroborated by the results of our additional analyses reported in Footnote 4). Nevertheless, we do believe that future research would benefit from exploring the conditions under which exploitation career role enactment might play a (positive) role in influencing leader-rated employability. Specifically, organizations differ in the extent to which their daily lives revolve around managing risk and avoiding errors that could have unbearable consequences not only for the organization but also for society at large. For instance, organizations operating in risky contexts such as in the aviation and nuclear industry (e.g., air traffic control, nuclear power plants, radioactive waste disposal), military (e.g., aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines) or space industry will place a higher premium on safety, standardization and protocol adherence, given the immense negative consequences associated with any potential failures (cf. Hällgren et al., Citation2018). In these types of contexts, one might expect that exploitation career role enactment will be viewed as highly desirable and positively relate to leader employability evaluations, whereas it might also be the case that exploration career role enactment will be seen as less desirable, perhaps even translating into negative employability evaluations. Similarly, organizational cultures differ in the extent to which they favour flexibility and discretion versus stability and control (Cameron & Quinn, Citation1999). For instance, hierarchical cultures (high on stability and control and low on flexibility and discretion) might favour the enactment of exploitation career roles whereas adhocratic cultures (low on stability and control and high on flexibility and discretion) may not. Thus, future research could benefit from exploring how specific organizational contexts (e.g., varying in the extent to which they need to manage risk; Hällgren et al., Citation2018) or cultures (e.g., favouring flexibility and discretion vs. stability and control; Cameron & Quinn, Citation1999) may influence the extent to which exploitation vs. exploration career role enactment differentially predict leader-rated employability.

Whereas the Career Roles Model distinguishes between three exploration career roles (expert, guide and inspirer), in this study, we treated them as one overarching cluster. This decision was theoretically guided by the fact that we were only interested in their shared common core: individuals enacting all three roles target variability, exploration and change and showcase adaptability by focusing on developing new skills, knowledge and ability (Hoekstra, Citation2011). Hence, in the context of leader-rated employability, there was no theoretical reason to treat them separately. Our decision-making is supported by statistical findings: the three roles were highly intercorrelated and our factor analysis indicated that they load on one factor. Moreover, our current sample would have been too small to include them as separate factors in the design (Faul et al., Citation2009). Future research could however benefit from identifying the conditions under which the distinct exploration career roles might differentially impact leader-rated employability. For instance, it could focus on how the different motives (i.e., integration, distinction and structure motives) that are associated with the different roles (Hoekstra, Citation2011) might differentially affect leader-rated employability

Another point to consider is that employee exploratory behaviour might not always be viewed positively. Indeed, whether supervisors value exploration may also be contingent on other factors such as the employee’s perceived motives, intentions or competence (Chan, Citation2006; Grant et al., Citation2009) or supervisors’ own expectations (Seibert et al., Citation2001). Moreover, some researchers have cautioned that employee proactive behaviour may not always be desirable and might have negative consequences for the organization, co-workers or the self (Belschak & Den Hartog, Citation2010; Bolino et al., Citation2016). For instance, employees who constantly raise questions about current procedures and suggest new and different ways of doing things could give rise to conflicts as they challenge the status quo (Grant, Citation2013) which may negatively affect leader-rated employability. Moreover, employees who voice their opinions and speak up may be perceived as threatening leader power which may lead to negative evaluations or other forms of retaliatory behaviour on the part of the leader (cf. Wisse et al., Citation2019; Yang et al., Citation2021). Future research would thus benefit from further exploring the potential boundary conditions under which the enactment of exploratory career roles may be positively or negatively associated with leader-rated employability. In this respect, we deem a more balanced focus that considers interdependencies between organizational members as particularly important, especially in light of the fact that adaptability may also detrimentally impact others or the organization (in the short or longer-term).

Practical implications

Although conclusions regarding practical implications should be regarded as tentative, we see potential for our findings to be used in applied settings. First, our work suggests that individuals who enact exploration career roles are seen as more employable by others. Those transitioning into the world of work, could therefore benefit from embracing exploration career roles. Furthermore, organizations may benefit from investing resources in promoting employees’ career role development, as this might not only positively impact individual employability but also help build organizational capability, adaptability and resilience. For instance, interventions such as individual coaching, job-crafting training (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001) or work-redesign (Parker & Bindl, Citation2016) could be launched to increase employees’ will and ability to flexibly shift between a broader set of tasks and roles. Second, acknowledging that employability may also be contingent on the fit between employees and leaders, it may be equally important for organizations to invest resources into supervisor training. Training leaders to develop ambidextrous leadership skills might not only promote leader-employee fit, but could also enhance ambidexterity capability across the organization.

Conclusion

This research shows that enacting exploration career roles may help individuals be seen as more employable by others and that these assessments hinge on the compatibility between employee and leader behaviours. Indeed, leader evaluations of subordinate employability were particularly positive when employee exploration activities complemented leader behaviours (i.e., either high closing or low opening behaviours). With this work we hope to have opened an avenue for exploring the potential interactive effects of employee and leader behaviours in co-determining long-term employability and career success.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. We measured leader-rated employability with the full 11-item scale of Rothwell and Arnold (Citation2007). One item (i.e., “In my opinion, this employee could get any job anywhere, as long as his/her skills and experience were reasonably relevant”) had to be dropped to increase model fit. Running all analyses with the full 11-item scale does not change the significance or pattern of our results.

2. We allowed for two item error term correlations – for items using similar phrasing – to improve model fit. Details are available upon request.

3. This small positive correlation between opening and closing behaviours is in line with the notion that the two behaviours are not mutually exclusive (Rosing et al., Citation2011). Moreover, previous field studies with similar sample sizes also found similar positive correlations between opening and closing behaviours. See, for instance, Zacher et al. (Citation2016) (r = .19; p < . 01) and Mascareño et al. (Citation2021) (r = .31; p < .001).

4. We ran an additional set of analyses controlling for a number of covariates that might be related to leader-rated employability (Rothwell & Arnold, Citation2007), namely subordinate age (in years), gender (1 = male, 2 = female), level of education (1 = primary education to 7 = bachelor’s degree or higher) and tenure with current leader (1 = less than 6 months to 6 = 10 years or more). We also controlled for exploitation career role enactment (Hoekstra, Citation2011) which was assessed using the 15 items of the exploitation roles subscales (maker, presenter, and director role; 5 items per subscale) of the CRRQ-30 (1 = not at all to 7 = very well; α = .91) and the interactions between exploitation career role enactment and leader opening and closing behaviours. Exploitation career role enactment was not related to employability evaluations and neither were the interactions between exploration career role enactment and leader opening and closing behaviours. Including all of the covariates did also not meaningfully alter our pattern of results. In line with current recommendations in the field (Sturman et al., Citation2021) we report the results without covariates.

5. We ran additional sets of analyses replacing our exploration career role enactment predictor with the separate exploration career role subscales (expert, guide, inspirer). The results are in line with those of our main analyses. First, all three subscales positively predict employability evaluations (p < .01). Second, we find the same pattern of results (albeit not always significant) for the interactions: the interactions between the guide role and leader opening and closing behaviour were both significant (p < .05); the interaction between the expert role and leader opening behaviour was not significant (p = .22) whereas the one between the expert role and leader closing behaviour was significant (p < .01); the interaction between the inspirer role and leader opening behaviour was marginally significant (p = .08) whereas the one between the inspirer role and leader closing behaviour was significant (p < .05).

References

- Akkermans, J., & Hirschi, A. (2023). Career proactivity: Conceptual and theoretical reflections. Applied Psychology, 72(1), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12444

- Badura, K. L., Grijalva, E., Galvin, B. M., Owens, B. P., & Joseph, D. L. (2020). Motivation to lead: A meta-analysis and distal-proximal model of motivation and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(4), 331–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000439

- Barrett, P. (2007). Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 815–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018

- Baruch, Y., & Bozionelos, N. (2011). Career issues. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 2. Selecting and developing members for the organization (pp. 67–113). American Psychological Association.

- Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

- Belschak, F. D., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2010). Being proactive at work– blessing or bane? The Psychologist, 23(11), 886–889.

- Berntson, E., Sverke, M., & Marklund, S. (2006). Predicting perceived employability: Human capital or labour market opportunities? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 27(2), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831x06063098

- Bolino, M. C., Turnley, W. H., & Anderson, H. J. (2016). The dark side of proactive behavior: When being proactive may hurt oneself, others or the organization. In S. K. Parker & U. K. Bindl (Eds.), Proactivity at work: Making things happen in organizations (pp. 499–529). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315797113

- Bozionelos, N., Kostopoulos, K., Van der Heijden, B., Rousseau, D. M., Bozionelos, G., Hoyland, T., Miao, R., Marzec, I., Jędrzejowicz, P., Epitropaki, O., Mikkelsen, A., Scholarios, D., & Van der Heijde, C. (2016). Employability and job performance as links in the relationship between mentoring receipt and career success: A study in SMEs. Group & Organization Management, 41(2), 135–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601115617086

- Bozionelos, N., Lin, C., & Lee, K. Y. (2020). Enhancing the sustainability of employees’ careers through training: The roles of career actors’ openness and of supervisor support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 103333. Article 103333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103333

- Byza, O. A. U., Dörr, S. L., Schuh, S. C., & Maier, G. W. (2019). When leaders and followers match: The impact of objective value congruence, value extremity, and empowerment on employee commitment and job satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 1097–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3748-3

- Cable, D. M., & Edwards, J. R. (2004). Complementary and supplementary fit: A theoretical and empirical integration. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 822–834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.822

- Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (1999). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. Addison-Wesley Publishing.

- Chan, D. (2006). Interactive effects of situational judgment effectiveness and proactive personality on work perceptions and work outcomes. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(2), 475–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.475

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- De Jong, N., Wisse, B. M., Heesink, J. A. M., & Van der Zee, K. I. (2019). Personality and career roles: The mediating role of career role preferences. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1720. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01720

- De Vos, A., Jacobs, S., & Verbruggen, M. (2021). Career transitions and employability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126. Article 103475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103475

- De Vos, A., Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M., & Akkermans, J. (2020). Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.011

- Dries, N., Vantilborgh, T., & Pepermans, R. (2012). The role of learning agility and career variety in the identification and development of high potential employees. Personnel Review, 41(3), 340–358. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481211212977

- Dutton, J. E., & Ashford, S. J. (1993). Selling issues to top management. The Academy of Management Review, 18(3), 397–428. https://doi.org/10.2307/258903

- Epitropaki, O., Marstand, A. F., Van der Heijden, B., Bozionelos, N., Mylonopoulos, N., Van der Heijde, C. M., Scholarios, D., Mikkelsen, A., Marzec, I., Jędrzejowicz, P., & The Indicator Group. (2021). What are the career implications of ‘seeing eye to eye’? Examining the role of leader-member exchange (LMX) agreement on employability and career outcomes. Personnel Psychology, 74(4), 799–830.

- Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. (2005). Enhancing career benefits of employee proactive personality: The role of fit with jobs and organizations. Personnel Psychology, 58(4), 859–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00772.x

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Forrier, A., De Cuyper, N., & Akkermans, J. (2018). The winner takes it all, the loser has to fall: Provoking the agency perspective in employability research. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12206

- Forrier, A., & Sels, L. (2003). The concept of employability: A complex mosaic. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 3(2), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHRDM.2003.002414

- Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005

- Fugate, M., Van der Heijden, B., De Vos, A., Forrier, A., & De Cuyper, N. (2021). Is what’s past prologue? A review and agenda for contemporary employability research. Academy of Management Annals, 15(1), 266–298. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2018.0171

- Fuller, J. B., Marler, L. E., & Hester, K. (2012). Bridge building within the province of proactivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1053–1070. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1780

- Gentry, W. A., & Sparks, T. E. (2012). A convergence/divergence perspective of leadership competencies managers believe are most important for success in organizations: A cross-cultural multilevel analysis of 40 countries. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9212-y

- Grant, A. M. (2013). Rocking the boat but keeping it steady: The role of emotion regulation in employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1703–1723. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0035

- Grant, A., Gino, F., & Hofmann, D. (2011). Reversing the extraverted leadership advantage: The role of employee proactivity. The Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 528–550. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.61968043

- Grant, A. M., & Parker, S. K. (2009). Redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 317–375. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903047327

- Grant, A. M., Parker, S., & Collins, C. (2009). Getting credit for proactive behavior: Supervisor reactions depend on what you value and how you feel. Personnel Psychology, 62(1), 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.01128.x

- Greiff, S., & Heene, M. (2017). Why psychological assessment needs to start worrying about model fit [Editorial]. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 33(5), 313–317. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000450

- Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 327–347. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.24634438

- Guilbert, L., Bernaud, J. L., Gouvernet, B., & Rossier, J. (2016). Employability: Review and research prospects. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 16(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-015-9288-4

- Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G., & Salley, C. E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.22083026

- Hällgren, M., Rouleau, L., & Rond, M. (2018). A matter of life and death: How extreme context research matters for management and organization studies. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 111–153. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0017

- Hall, D. T., Yip, J., & Doiron, K. (2018). Protean careers at work: Self-direction and values orientation in psychological success. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104631

- Hansbrough, T. K., Lord, R. G., & Schyns, B. (2015). Reconsidering the accuracy of follower leadership ratings. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 220–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.11.006

- Havermans, L. A., Den Hartog, D. N., Keegan, A., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2015). Exploring the role of leadership in enabling contextual ambidexterity. Human Resource Management, 54(51), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21764

- Heene, M., Hilbert, S., Draxler, C., Ziegler, M., & Bühner, M. (2011). Masking misfit in confirmatory factor analysis by increasing unique variances: A cautionary note on the usefulness of cutoff values of fit indices. Psychological Methods, 16(3), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024917

- Hoekstra, H. A. (2011). A career roles model of career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 78(2), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.09.016

- Hofmans, J., Dóci, E., Solinger, O. N., Choi, W., & Judge, T. A. (2019). Capturing the dynamics of leader–follower interactions: Stalemates and future theoretical progress. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(3), 382–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2317

- Hogan, R., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Kaiser, R. B. (2013). Employability and career success: Bridging the gap between theory and reality. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 6(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/iops.12001

- Holtschlag, C., Morales, C. E., Masuda, A. D., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2013). Complementary person–culture values fit and hierarchical career status. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82(2), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.11.004

- Huckvale, T., & Ould, M. (1995). Process modelling – who, what and how: Role activity diagramming. In V. Grover & W. J. Kettinger (Eds.), Business process change: Concepts, methods, and technologies (pp. 330–349). Idea Group Publishing.

- Itti, L., & Baldi, P. (2009). Bayesian surprise attracts human attention. Vision Research, 49(10), 1295–1306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2008.09.007

- James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology (Vol. 1). Henry Holt and Co. https://doi.org/10.1037/10538-000

- Jansen, J. J. P., Van Den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2006). Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science, 52(11), 1661–1674. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0576

- Jelinek, M., & Schoonhoven, C. B. (1990). The innovation marathon: Lessons from high technology firms. B. Blackwell.

- Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208687

- Junni, P., Sarala, R. M., Taras, V., & Tarba, S. Y. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity and performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0015

- Kenny, D. A., & McCoach, D. B. (2003). Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(3), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1003_1

- Kim, M., Shin, Y., & Gang, M. C. (2017). Can misfit be a motivator of helping and voice behaviors? Role of leader-follower complementary fit in helping and voice behaviors. Psychological Reports, 120(5), 870–894. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117711131