ABSTRACT

This paper examines how and why work meaning (i.e., what work signifies to an individual) is affected by a macroeconomic indicator: the national unemployment rate. We conducted three studies that explore how and why perceptions of work meaning are related to the unemployment rate of the country in which the work is embedded. Study 1 utilized cross-national data from the International Social Survey Programme and revealed that higher unemployment rates in a country were associated with employees placing less emphasis on the non-financial aspects of work meaning; Study 2 used data from the General Social Survey and found that during worse economic conditions, employees in the US tended to prioritize financial job meaning more. In Study 3, an experiment similarly found that individuals placed more emphasis on financial work meaning in the high unemployment condition compared to the control condition. It also identified the important mediating role of individual experience of uncertainty in explaining such relationships. This paper discusses how our findings contribute to better understandings of the societal-level antecedents of work meaning.

The meaning of work (or work meaning), as defined by Pratt and Ashforth (Citation2003), refers to the significance individuals attribute to work within the context of their lives. This concept is crucial as it is closely linked to people’s decisions to enter or leave the workforce and provides insights into how organizations can motivate their employees (O’reilly & Caldwell, Citation1980; Super & Šverko, Citation1995). Consequently, scholars have extensively explored the antecedents of work meaning (Rosso et al., Citation2010). While there has been significant focus on proximal causes of work meaning (e.g., Nord et al., Citation1990; Podolny et al., Citation2005; Shamir, Citation1991; Wrzesniewski et al., Citation2003), there is a noted gap in research regarding broader macro-level influences (Bailey et al., Citation2019; Pratt & Ashforth, Citation2003). Our current research aims to bridge this gap by examining macro-level antecedents of work meaning, specifically exploring the relationship between the national unemployment rate and individuals’ perceived meaning of work. Additionally, this study investigates whether two psychological processes – fear and uncertainty – may act as mediators in this relationship.

Extensive research has demonstrated that macro-level societal factors significantly influence human attitudes and behaviours (e.g., Dávalos et al., Citation2012; Inglehart & Baker, Citation2000; Inglehart et al., Citation2008; Kahn, Citation2010), highlighting their potential as antecedents of work meaning. To explore this area, our current research was inspired by sociological research on modernization, which examines how transitions from traditional to modern societal contexts across economic, technological, political, and cultural dimensions impact individuals’ values and attitudes (De Witte et al., Citation2004; Inglehart & Welzel, Citation2007). For instance, studies indicate that national economic conditions correlate strongly with various aspects of people’s attitudes, including work values (De Witte et al., Citation2004), work ethics (Stam, Citation2015), and postmaterialism (Clarke & Dutt, Citation1991; Inglehart & Abramson, Citation1994). This evidence underscores the potential significance of macro-level factors in understanding the meaning of work.

Note that the current research specifically focuses on the unemployment rate because this indicator is more closely related to individuals’ assessments about the broader economy than other economic indicators such as GDP (e.g., Chattopadhyay & Bianchi, Citation2020; Dávalos et al., Citation2012; Kahn, Citation2010; Zagelmeyer & Gollan, Citation2012). Using this indicator also facilitates direct comparisons with other study findings because the unemployment rate is “the variable most frequently used across disciplines to examine how the economy affects attitudes and behaviors” (Chattopadhyay & Bianchi, Citation2020, p. 12).

Furthermore, we interpret a high unemployment rate as a source of threatening information, signalling fewer job opportunities and a more unstable job market. Drawing from research on job insecurity (Jiang & Lavaysse, Citation2018) and neuropsychological reinforcement sensitivity models (McNaughton & Corr, Citation2004), such information may induce feelings of uncertainty and fear. Consequently, our research goes beyond merely testing how the national unemployment rate affects work meanings. It tests the mechanisms underpinning these effects, with a particular focus on employees’ experiences of fear and uncertainty. By doing so, this study offers three significant contributions to the literature.

First, to address the need for a greater focus on societal factors affecting work meaning (Bailey et al., Citation2019), our study examines a specific macroeconomic factor: the national unemployment rate. By demonstrating the significant impact of the unemployment rate on work meaning, this research empirically underscores the importance of considering distant antecedents of work meaning to gain a comprehensive understanding of how individuals perceive work. Additionally, this study contributes to the broader literature on the influence of macro-level factors on individual-level outcomes (e.g., Bianchi, Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2020; Bianchi & Mohliver, Citation2016; Chatrakul Na Ayudhya et al., Citation2019; Inglehart, Citation1990), enhancing our knowledge of how distant societal factors can profoundly affect human attitudes.

Secondly, research into the mechanisms linking macro-level factors to micro-level outcomes is limited. A clear understanding of these mechanisms is essential for comprehending the reasons behind these connections and adjusting leadership strategies in response to societal changes. Our study explores both emotional (i.e., fear) and cognitive (i.e., uncertainty) pathways through which unemployment rates affect individuals’ work meanings. In particular, by showing the important mediating role of uncertainty in explaining such effect, our research offers valuable insights for researchers and practitioners on how to proactively adapt to varying societal situations. Specifically, it highlights the importance of managers proactively reducing employees’ cognitive uncertainty in the face of economic hardships.

Third, previous research on the relationship between national unemployment rate and materialism, specifically economic and physical safety values, has yielded inconsistent results. Some studies reported positive effects (De Witte et al., Citation2004; Inglehart & Abramson, Citation1994), while others argued for negative effects (Clarke & Dutt, Citation1991). While previous research has offered critical insights, our study advances the field by utilizing a more comprehensive dataset over an extended period and incorporating more precise measures of individuals’ economic values. Consequently, our research provides nuanced perspectives and makes significant contributions to the ongoing debate, addressing areas where earlier studies may have encountered limitations in data scope and the precision of individual value assessments. It demonstrates that, when specific factors are accounted for when making cross-national comparisons, the national unemployment rate tends to positively influence people’s emphasis on financial rewards. These findings align with existing research on the positive correlation between national unemployment rates and materialism (De Witte et al., Citation2004; R. Inglehart & Abramson, Citation1994).

The conceptualization of national unemployment rate and work meaning

In this section, we present the common conceptualizations of the national unemployment rate and work meaning as found in the literature, and explain the rationale behind our specific conceptualizations of these two concepts. The unemployment rate is typically defined as the percentage of unemployed individuals in relation to the total labour force. However, literature varies in its definition of who is considered unemployed. For example, while most sources define the unemployed as those without a job but actively seeking work, others contend that unemployment classification should not depend on job search behaviours but rather on whether individuals desire for employment (Jones & Riddell, Citation1999; Shorrocks, Citation2009). In this paper, we take the view adopted by the World Bank (Citation2021) and consider unemployment as the proportion of the labour force that is without work, yet available for and actively seeking employment. We took this conceptualization because it is consistent with World Bank’s documented unemployment rates, which we used in our Studies 1 and 2. Although we recognize that our approach to conceptualizing and measuring unemployment rates is more conservative than the alternative method, we believe this cautious approach does not affect our findings. This is because the underestimation of unemployment rates was systematic across all countries, leaving the magnitude of the relationship between unemployment rate and work meaning unchanged.

The meaning of work has been studied from various perspectives, ranging from the importance of work to people in their life (i.e., work centrality as a life role, MOW International Research Team, Citation1987), an individual’s orientation towards their work (i.e., seeing it as a job, as a career, or as a calling, Wrzesniewski et al., Citation1997), the valued work outcomes (e.g., autonomy, prestige, needed income, time absorption, interesting tasks, interpersonal contacts, and service to society, Kaplan & Tausky, Citation1974; MOW International Research Team, Citation1987). These perspectives are interconnected by certain foundational elements (Harpaz & Fu, Citation2002). Scholars have predominantly delineated two overarching classifications of work meaning for individuals: the extrinsic (e.g., monetary benefits) and the intrinsic components of work (e.g., engaging tasks) (De Witte et al., Citation2004; Ros et al., Citation1999). The intrinsic-extrinsic classification of work meaning has been most widely used in this area (Lindsay & Knox, Citation1984). In addition to this broad dichotomous classification of work meaning, alternative theoretical frameworks offer nuanced perspectives on the potential motivations that individuals maintain towards their work, such as self-determination theory (SDT, Ryan & Deci, Citation2000), and needs in work settings framework (Steers & Braunstein, Citation1976).

In our study, we primarily distinguish between the financial and non-financial aspects of work meaning. This classification partially aligns with the intrinsic-extrinsic typology; the financial meaning is a dimension of extrinsic work meaning, while the non-financial dimension encompasses not only intrinsic work meanings but also certain extrinsic aspects. We opted for this distinct categorization as it aligns well with our research objectives. Given that the foremost purpose of working is to secure a livelihood, the most substantial impact of job loss is typically the loss of income. Consequently, our paper posits that higher national unemployment rates accentuate the financial significance of employment. Conversely, formulating a precise hypothesis regarding the impact of unemployment on non-financial aspects is more challenging. Therefore, adopting this dichotomous classification thus allows for a more streamlined analysis of the interplay between unemployment rates and financial work meaning. Moreover, another reason for adopting this distinction between financial and non-financial factors is that some of our data is secondary; therefore, our conceptualization needs to align with the existing measurements. Despite the benefits, we acknowledge that this approach has a broad scope of non-financial work meaning, leaving room for future research to explore the relationship between national economic conditions and specific non-financial work meaning dimensions.

How and why the national unemployment rate influences work meanings

The translation from macro/societal-level features to individual experience and attitudes is a well-established research field in sociology and political science. The work by Ronald Inglehart and his colleagues is particularly relevant to our research question, as they propose that macro-level factors such as industrialization, modernization, and economic affluence can encourage individuals to move beyond survival-level demands and focus on postmaterial concerns (Inglehart, Citation2008; Inglehart & Abramson, Citation1994; Inglehart & Baker, Citation2000; Inglehart & Welzel, Citation2007; Inglehart et al., Citation2008). For example, in a society that places high importance on education and invests significantly in educational expenditure, individuals are more likely to be well-educated and may prioritize postmaterial values (Zhang, Citation2022). In a country where there is a significant investment in public health expenditure, the basic needs of the people, such as safety and health, are likely to be better met. As a result, the individuals in such societies are more inclined to focus on higher level needs such as autonomy and achievement (Ng & Diener, Citation2014). Inspired by the research, we propose that the national unemployment rate can have a significant impact on individuals’ perceived work meaning. Specifically, we suggest that the financial work meaning, which reflects individuals’ material concerns, may be influenced by the unemployment rate.

When the unemployment rate is high, it indicates a weaker job market with fewer opportunities, posing a threat to job security (Anderson & Potunsson, Citation2007; Debus et al., Citation2012; Otto et al., Citation2010). This threat can lead to people’s perception of job insecurity, consisting of cognitive job insecurity (the perceived uncertainty of job continuity) and affective job insecurity (emotional reactions to the perceived uncertainty, such as fear) (Jiang & Lavaysse, Citation2018). A high national unemployment rate also serves as an environmental cue that highlights the negative consequences of job loss and financial instability, reinforcing employees’ focus on financial work functions, as per social information processing theory (Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978). Consequently, we consider perceived uncertainty a mechanism explaining the relationship between the unemployment rate and work meaning. In addition to literature on affective job insecurity (see Jiang & Lavaysse, Citation2018 for a meta-analysis), neuropsychological reinforcement sensitivity models also suggest that fear is a crucial emotional response to threatening information. Thus, we propose fear as another mechanism linking the national unemployment rate and perceived work meaning (McNaughton & Corr, Citation2004). Notably, we approach uncertainty and fear in broader terms, extending beyond the specific apprehensions related to potential job loss. After introducing Hypothesis 1 below, we will elaborate on how the national unemployment rate influences individuals’ work meaning through uncertainty and fear.

Hypothesis 1:

Higher national unemployment rates will be associated with an increased individual focus on the financial meaning of work.

In challenging economic times, like when national unemployment rates are high, both personal and collective uncertainty increase. At a firm level, this economic uncertainty often leads to delays in important business decisions, such as investments and hiring (Bloom, Citation2009). Such pervasive economic uncertainty can directly affect individuals as they contemplate their job security and financial stability (Paulsen et al., Citation2005). At a psychological level, in societies with high unemployment rates, job replaceability increases, causing individuals to perceive their employment as less secure. This perception may encompass potential demotions, pay cuts, or layoffs, leading to heightened experiences of perceptual and behavioural conflict, typical of uncertainty (Buhr & Dugas, Citation2002). Cognitive job insecurity can also extend to perceived threats to financial stability and other job-related extrinsic benefits like health insurance and retirement plans, contributing to a broader sense of uncertainty (Jonas et al., Citation2014). As uncertainty mounts, individuals often prioritize immediate needs, particularly financial stability (Yeves et al., Citation2019). Research on job insecurity confirms this focus on financial motives when individuals feel insecure about their jobs (Lee et al., Citation2018). Prolonged uncertainty tends to amplify the salience of threatening information, causing individuals to concentrate more on potential negative outcomes (Gray & McNaughton, Citation2000). Consequently, high levels of uncertainty may lead people to emphasize the financial meaning of work.

In addition to perceived uncertainty, fear, characterized by a desire to escape threats (Ekman, Citation1992), may stem from financial hardship. Two pathways explain how fear arises. First, cognitive job insecurity (perceived uncertainty) often triggers the fear of job loss (a form of emotional job insecurity, Jiang & Lavaysse, Citation2018). Losing a job can jeopardize rent, bills, and living expenses, particularly when employment is the primary income source (Brand, Citation2015; Veenhoven, Citation1989). Even those with stable jobs may fear job loss and financial insecurity during economic downturns, because jobs become scarcer when unemployment rates are high. This aligns with Inglehart’s scarcity theory (Inglehart, Citation2008), which emphasizes the value of scarce resources. Thus, individuals may experience fear as an indirect result of high unemployment rate, through perceived uncertainty.

Second, a society’s challenging financial situation can directly influence the fear levels of its people. Fear is contagious (Barsade, Citation2002), spreading through social environments, including workplaces and families (Barsade, Citation2002; Goodman & Shippy, Citation2002). For instance, the U.K. experienced widespread expressions of fear and negative emotions on social media after recession-related budget cut announcements (Lansdall-Welfare et al., Citation2012). Social media can diffuse emotional reactions (like fear) in society, reinforcing the association between high unemployment rates and joblessness (Brym et al., Citation2014; Nabi, Citation2009). Additionally, fear redirects attention to threats, away from non-threatening information (Damasio & Carvalho, Citation2013; Lazarus, Citation1991). During economic downturns, individuals with financial fears tend to focus more on monetary matters.

While it’s true that the non-financial perks of employment, like fostering social connections and engaging in fulfilling tasks, can wane after job loss, it’s essential to recognize the potential for compensation through alternative avenues. For instance, the erosion of non-financial fulfilment due to job loss can be mitigated through volunteer work (Rodell, Citation2013). Engaging in volunteer activities not only reignites social connections but also provides opportunities for intellectually stimulating tasks, effectively offsetting the loss. However, predicting how individuals might compensate for the loss of non-financial benefits due to unemployment is challenging. Consequently, we cannot formulate a specific hypothesis about the relationship between the national unemployment rate and non-financial work meanings. Therefore, in our current research, rather than proposing a definitive hypothesis, we have left the exploration of this relationship to empirical testing. Together, we argue that amidst the multifaceted consequences of job loss, the most substantial and immediate challenge lies in the financial realm. In summary, we predict that high unemployment rates can trigger widespread increases in fear and uncertainty throughout the labour force. This heightened fear and uncertainty, in turn, is expected to direct employee attention towards financial threats and lead them to focus more on work’s financial significance. We have thus formulated the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2:

Fear will mediate the positive relationship between the national unemployment rate and a focus on the financial meaning of work, such that higher national unemployment rates will be associated with more fear, which further be related with more financial work meaning.

Hypothesis 3:

Uncertainty will mediate the positive relationship between the national unemployment rate and a focus on the financial meaning of work through two pathways. Specifically, higher national unemployment rates will be associated with greater uncertainty, which will (4a) further correlate with an increased emphasis on financial work meaning, and (4b) lead to heightened levels of fear, which will, in turn, be associated with a stronger focus on financial work meaning.

Study overview

In a series of three studies, we explored the relationship between national unemployment rates and the perceived meaning of work. In Study 1, we utilized data from 38 countries, obtained from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) questionnaire on work orientations in 2005 and 2015. This data enabled us to investigate whether perceptions of financial and non-financial work meaning were related to national unemployment rates at the time of survey administration. To assess the replicability of our findings, we employed survey data from the General Social Survey (GSS) in the United States in Study 2, examining whether employees’ experiences of financial work meaning varied with unemployment rates over time. In Study 3, we implemented an experimental design to explore how and why perceptions of unemployment rates might influence work meanings. This third study allowed us to scrutinize the psychological mechanisms by which a macro-level economic factor (i.e., the national unemployment rate) can affect a micro-level experience of an individual’s work (i.e., the financial meaning of work).

Study 1

Overview and sample

In Study 1, we used an extensive cross-country data set to test our hypotheses. We drew on survey data from the International Social Survey Programme’s (ISSP’s) Work Orientations Module (ISSP Research Group, Citation2013; also described in Hu & Hirsh, Citation2017). The work orientations module data is available for 1989, 1997, 2005, and 2015. However, only the data for 2005 and 2015 contained several items measuring the meaning of work.

The samples for Study 1 were drawn from the 2005 and 2015 ISSP work orientation data on people who had full-time jobs when they responded to the survey questions. The ISSP data had several positive characteristics. First, a large number of responses were collected from more than 30 countries, which supports the potential generalizability of the study’s findings. Second, its items were designed by experienced researchers, with a standardized data collection procedure that guaranteed the quality of the data. Third, the dataset includes measures of work meaning and proxy items for our proposed mediation mechanisms from both 2005 and 2015, allowing us to examine whether the relationship between the unemployment rate and the meaning of work and the mediation relationships existed and changed during this period.

Given our interest in employees’ perceptions of their own work’s meaning, respondents were only included if they were employed full-time and gave valid responses regarding all the predictor and outcome variables. The resulting sample comprised 18,919 participants from 31 countries in 529 different work categories in 2005, and 18,106 participants from 24 countries in 493 different work categories in 2015. In 2005, the unemployment rate ranged from a low of 3.50% in Mexico to a high of 23.80% in South Africa. In 2015, the unemployment rate ranged from a low of 3.40% in Japan to a high of 25.15% in South Africa. Overall 19,119 participants were male, and 17,893 were female. They received an average of 14.31 (SD = 16.16) years of formal education and, on average, were 35.91 (SD = 14.12) years old at the time of the survey administration.

Measures

Unemployment rate

The national unemployment rates of the countries included in the survey were obtained from the World Bank’s open data archives (World Bank, Citation2021). A high unemployment rate is generally an indicator of worse macroeconomic conditions, while a low unemployment rate tends to accompany more prosperous conditions.

Work meaning

Two items were selected from the ISSP data to measure the meaning of work. We used the item “A job is just a way of earning money – no more” to measure financial work meaning and the item “I would enjoy having a paid job even if I did not need the money” to measure non-financial work meaning. A 5-point Likert scale was used in the original survey, where 1 = strongly agree and 5 = strongly disagree. We reversed these responses for a more intuitive coding scheme.

Fear

To operationalize fear, we used the item “To what extent do you worry about the possibility of losing your job?” from the ISSP data, as worry and fear are similar emotions (Stavosky & Borkovec, Citation1987), and previous research has used worry to measure fear (Leary, Citation1983). The original survey used a 4-point Likert scale, where 1 = “I worry a great deal” and 4 = “I don’t worry at all.” We reversed these responses for a more intuitive coding scheme.

Control variables

Several demographic variables were included as covariates to control for potential confounders. Age was included because older people tend to report more non-financial work meaning (Spreitzer & Mishra, Citation2002). We included gender because men tend to focus on the financial meaning of their work more than women (Artazcoz et al., Citation2004). Years of formal education was included because higher education levels are associated with an increased focus on the non-financial meaning of work (Spreitzer & Mishra, Citation2002). Whether the respondent had children was also included as a control variable, because having children significantly increases monetary needs, which could increase the focus on the financial meaning of work. In addition, yearly household income (i.e., the z-score of household income within each country) was included as a control variable that is of particular interest in the current paper. It is commonly believed that lower household income relates to the adoption of more financial work meanings (Jahoda, Citation1981; Vohs et al., Citation2006). Controlling employees’ household income allowed us to examine whether the national unemployment rate predicts financial work meaning above and beyond an individual’s personal financial situation. We also controlled other country-level economic factors (such as national educational expenditure and national health expenditure) to test whether national unemployment rates go beyond other societal factors to predict work meaning. Individuals with health conditions that limit their ability to work and those with low educational attainment may face more challenges in the labour market (McAllister et al., Citation2015). As a result, the unemployment rate may have a greater impact on these groups of people. Thus, national health and educational expenditure are important to consider when assessing the effects of the national unemployment rate on people. To ensure the robustness of the results, we conducted the following analyses with and without the control variables included.

Results

We pooled data from 2005 and 2015 into a single sample. Given the nested nature of the data, where individual responses are nested within countries, and countries are nested within the assessment year, we employed hierarchical linear modelling (HLM), a multi-level analysis method, for the analyses. Intraclass correlation coefficients revealed that significant amounts of the variance in an individual’s focus on financial work meaning [ICC(1) = .14, ICC(2) = .99, F = 210.20, p < .001] and non-financial work meaning [ICC(1) = .08, ICC(2) = .99, F = 110.40, p < .001] were attributable to country-level effects. Based on these results, we continued with the HLM analyses. Random intercepts were included for country and the year of assessment.

summarizes the results of the HLM analyses. Consistent with our hypothesis, a higher unemployment rate was significantly associated with an increased focus on the financial meaning of work (, Model 1), although the effect became insignificant after the control variables were included (, Model 3). In addition, we found a decreased focus on the non-financial meaning of work (, Models 5 and 7). Considering the effects of societal factors on individuals living in that society can differ across different years and cohorts (Zhang et al., Citation2020), it is important to test the relationships using data collected in the two years separately. We compared the relationship between the unemployment rate and the work meaning for the data collected in 2005 and 2015. The results indicated that there was no significant difference in the relationship between financial (β = .001, p > .10) or non-financial work meaning (β = .00, p > .10) and unemployment rates between the two years. This suggests that the magnitude of the relationships between unemployment rates and work meaning did not change across the two time points.

Table 1. Results of HLM analyses in study 1.

Moreover, we analysed the mediation effects of fear using the “lavaan” package in R. The multi-level path analysis results revealed that a higher national unemployment rate was related to more fear (β = .04, p < .001), which further predicted more financial work meaning (β = .25, p < .001), supporting the mediation effect of fear. The mediated effect by fear accounted for 21.95% percent of the effect on financial work meaning. The relationship between fear and non-financial work meaning was not found (β = −.04, p = .07), suggesting that fear did not mediate the relationship between national unemployment rate and non-financial work meaning. In addition to the mediated effect by fear, the direct effect of the national unemployment rate on financial work meaning (β = .03, p < .001) was significant, suggesting the existence of other mechanisms. The mediation effect remained significant after the control variables were included.

Discussion

Study 1 used ISSP data from various countries to examine the relationship between the unemployment rate and individual perceptions of work meaning. Before controlling for other factors, the unemployment rate was a significant country-level predictor of both financial and non-financial meaning of work. A notable merit of Study 1 is that its sample came from various countries and was collected at two different time points. The large and diverse sample ensured adequate statistical power for the analyses and generalizability of the findings. To examine the replicability of the results, Study 2 utilized a within-country dataset; although we recognize that national-level differences may still exist within the same country across different years, we expect the within-country data set to have less variability in national-level factors across different years than the cross-country dataset used in Study 1.

Due to the archival nature of the dataset, the measurements in Study 1 may have certain inherent limitations. For instance, the measurement of fear may have primarily captured the aspect of (affective) job insecurity, as the item includes references to the possibility of losing one’s job. In essence, instead of measuring the general feeling of fear, the fear measurement in Study 1 represents a more specific measure of fear, focusing primarily on individuals’ apprehensions related to job uncertainty. Despite the measurement limitation, we believe that the more specific measure of fear offers a more conservative test of our predictions and, therefore, provides useful information for testing our hypotheses. To address this measurement issue, in Study 3, we measured individuals’ general sense of fear, which was not specifically tied to the fear of job uncertainty.

Study 2

Overview and sample

In Study 2, we used a within-country design to test our first hypothesis, using survey data from the General Social Survey (GSS) in the United States. The National Opinion Research Center administers this large nationwide survey, collecting data from samples of non-institutionalized adults that are representative of the US population. The GSS was conducted annually from 1972 until 1993 (except for 1979, 1981, and 1992), with about 1,500 respondents included each year. Since 1994, the GSS has been administered biannually, with approximately 3,000 to 4,500 respondents each year, resulting in a large set of pooled time-series data.

Respondents were included if they were employed and gave valid responses for all the outcome variables of interest in this study. Because no work meaning measures were available for 1972, 1975, 1978, 1983, 1986, 1996–2004, 2008, 2010, 2016, and 2018, data from these years were not included in the analysis. The inclusion criteria resulted in 12,707 employed respondents across 18 years (1973, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1980, 1982, 1984–1985, 1987–1991, 1993–1994, 2006, 2012, and 2014). In these 18 years, US unemployment ranged from a low of 4.6% in 2006 to a high of 9.7% in 1982. On average, participants were 40.09 (SD = 13.09) years old at the time of the survey, with 6,820 (53.7%) females and 5,887 (46.3%) males.

Measures

Unemployment rate

The US national unemployment rate for each year of the included survey data was obtained from the World Bank (Citation2021).

Financial work meaning

Perceptions of work meaning were assessed using the following question from the core GSS module: “Would you please look at this card and tell me which one thing on this list you would most (next, third, fourth) prefer in a job?” Possible responses include “High income,” “No danger of being fired,” “Short working hours,” “Chances for advancement,” and “Work important and gives a feeling of accomplishment.” An item chosen as most preferred indicated that the item was most valuable to the respondent and thus received a score of 5. If an item was picked as the next (third, fourth) preferred, it was assigned a score of 4 (3 and 2, respectively). Because people tend to interpret the meaning of their jobs in relation to their own preferences and needs (Barrick et al., Citation2013), employees’ answers to this question can reveal how they construe the meaning of their work. The response option that best indicated a focus on financial job meaning was “high income.” Therefore, we utilized this response to gauge individuals’ emphasis on financial work meaning. Categorizing the remaining response options on the financial and non-financial work meaning dimensions was unclear, leading us to exclude them from our study.

Control variables

We included age, gender, years of education, and yearly household income as covariates, given their previously demonstrated relationship with employee perceptions of work meaning (Artazcoz et al., Citation2004; Jahoda, Citation1981; Spreitzer & Mishra, Citation2002). We also controlled national-level covariates such as national education and health expenditures.

Results

Data for Study 2 were nested, with employee responses grouped within the different years of data collection. Intraclass correlation coefficients revealed a significant amount of within-year agreement and between-year variance (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008) in the focus on financial work meanings, ICC(1) = 0.01, ICC(2) = 0.85, F = 6.73, p < 0.001. We analysed the data using a model that included the random effect of the data collection year at the second level, the fixed effect of the unemployment rate as a level-2 predictor, and the focus on financial work meaning as the individual outcome variable. The results (see ) revealed that higher unemployment rates were related to a greater emphasis on the financial meaning of work after including all the control variables (Model 2). This effect, however, was not significant when the controls were not included in the regression model (Model 1).

Table 2. Results of HLM analyses in study 2.

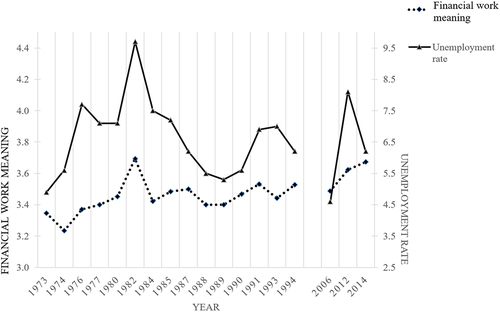

shows the trendlines of the unemployment rates and the focus on financial work meaning over time in the US. It revealed that peaks in unemployment rates are usually accompanied by increases in financial work meaning. thus demonstrates the parallel fluctuations of the national unemployment rate and the perceived financial meaning of work.

Figure 1. Yearly unemployment rate and financial work meanings in study 2.

To examine whether a high national unemployment rate relates to changes in perceptions of financial work meaning, we examined recessionary periods in recent US history. Unfortunately, the GSS data for 2001 and 2008 was not available. Thus, we could not explore how the two recessions around these years were associated with changes in the financial meaning of work. Instead, we focused on the severe recession of the early 1980s. The early 1980s recession was the worst economic downturn in the US since the Great Depression (Sablik, Citation2013). We used Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons from a one-way ANOVA to examine yearly differences in financial work meanings around this time. The comparisons between the year 1982 and the years 1977, 1980, 1984, and 1985 were especially relevant because these years were more temporally clustered than other years in the GSS data set. Results revealed that, in 1982 (when the recession was the worst), individuals reported a significantly greater focus on financial work meanings (M = 3.70) than in 1977 (M = 3.40, p < 0.001), 1980 (M = 3.45, p < 0.001), 1984 (M = 3.42, p < 0.001), or 1985 (M = 3.48, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Study 2 utilized data from the GSS to explore whether changes in the national unemployment rate across different years were associated with variations in the focus on financial work meaning in the United States. After controls were included, HLM analyses revealed a positive association between the annual unemployment rate and the adoption of financial work meanings. Additionally, we found that a severe recession was significantly linked to people’s experience of financial work meaning. Specifically, during the early 1980s recession in the United States, when the national unemployment rate peaked, people were more likely to interpret the meaning of their work based on financial concerns.

The relationship between the unemployment rate and financial work meaning exhibited varying strengths when controls were introduced in Study 1 and Study 2. This inconsistency might be attributed to the nature of the two datasets: the former was cross-national, while the latter focused on a single nation. In the cross-national dataset, factors like the unemployment rate, public expenditure in health, and education reflect a nation’s development stage. When we introduced other national control variables, the variance in the unemployment rate representing a nation’s development stage may have been partially accounted for, resulting in a weaker effect. However, in the United States dataset, the main effect of unemployment in Model 2 was initially masked by control variables. The inclusion of these controls was instrumental in revealing a clearer picture of the primary impact of unemployment.

While both Study 1 and Study 2 revealed associations between unemployment rates and work meaning, neither study can establish the causal direction of this relationship. Additionally, the first two studies did not test the entire mediation model. The next study used an experimental design to address these limitations. The psychological effects of macro-level economic conditions will likely be mediated through individual perceptions of the broader environment. In Study 3, we experimentally manipulated people’s perceptions of the national unemployment rate and explored whether people in different conditions differ in their perceptions of work meaning.

Study 3

Study overview and sample

Study 3 used a vignette study to test the impact of perceived unemployment rates on work meaning, a method used by organizational researchers to study the influence of perceived macroeconomic conditions on individuals’ reactions (e.g., Sirola & Pitesa, Citation2018). The vignette presented a paragraph that depicted a society’s unemployment rate as high or low to manipulate perceptions of the macroeconomic environment. This study also aimed to test our predictions that fear and uncertainty would mediate the relationship between unemployment rates and work meaning.

Business school undergraduate students in a large North American university participated in this study. With a small to medium effect size, to achieve a statistical power of at least 0.80, with an α error probability of 0.05, the predetermined sample size of a two-group between-subjects design must be at least 156. We met this criterion by collecting data from 260 students, who participated in the study for course credit. Four participants did not provide full responses, so their data were eliminated from the analyses. The final sample had 129 participants in the low unemployment rate condition and 127 in the high unemployment rate condition. Of the 256 participants, the mean age was 19.70 (SD = 1.38), with 140 identifying themselves as women, 115 as men, and 1 participant leaving the gender question blank.

Procedure

To prevent participants from inferring the true purpose of the study, we used a cover story that framed the study as a test of imaginative ability. Participants were randomly allocated to either a high or low unemployment rate condition. They read a paragraph describing a social-economic condition, imagined living in that society, wrote a short paragraph describing their thoughts and feelings, and completed a short survey. They were then thanked and debriefed.

We aimed to create vivid vignettes by providing specific details about the imagined society. For example, for the high unemployment condition, participants imagined observing a large number of employee layoffs, while for the low unemployment condition, they were told about the promotion of employees due to a growing economy.

Measures

Manipulation check

We tested whether the manipulation was successful by asking participants to indicate their agreement to two items using a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The two items were: “In the imaginary scenario, my society has a high unemployment rate” and “In the imaginary scenario, my society is experiencing an economic recession.” A higher score was expected from participants responding to the high unemployment rate condition.

Fear

Four items relating to the emotion of fear were used. Participants were instructed to respond to four items on a 7-point scale: 1 = not at all, 4 = neutral, and 7 = very much. The four items were: “To what extent do you feel worried/anxious/afraid/fearful of the consequences of the economic condition in the described scenario?” The mean score of the four items was calculated to measure the level of fear, with higher scores indicating greater fear. The reliability of this scale was α = 0.97.

Uncertainty

Three items were used to measure the sense of personal uncertainty on a 7-point scale ranging from 1(strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Participants were asked to think about the imaginary situation and rate the extent to which they would feel uncertain about their work, their life, and their future. The average of the three items was used as an overall index of uncertainty (α = 0.94). Higher scores indicate increased uncertainty.

Work meanings

The same items used in Study 1 were used in this study. A 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used.

Results

We conducted a manipulation check to verify whether the participants in the high unemployment rate condition perceived the economic environment differently from those in the low unemployment rate condition. The results showed that participants in the high unemployment rate condition reported significantly higher scores (M = 4.47) than those in the low unemployment rate condition (M = 1.82), t (254) = 24.27, p < .001, indicating that our manipulation was successful.

To test the main effect, we conducted an independent samples t-test. Participants in the high unemployment rate condition reported a greater focus on financial work meaning (M = 4.48) than those in the low unemployment rate condition (M = 3.57, t (254) = 4.36, p < .001). In exploring the effect on non-financial work meaning, we also found participants in the high unemployment rate condition to have a less focus on non-financial work meaning (M = 4.34) than those in the low unemployment rate condition (M = 4.77, t (254) = −2.18, p = .03).

We then conducted mediation analyses to examine the roles of fear and uncertainty in the above relationship. According to Hu and Bentler (Citation1999), the model fits were satisfactory: χ2 (2) = 5.52, p = .06, CFI = .99, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .03. Uncertainty was higher when participants imagined high unemployment (M = 5.85) in contrast to low unemployment (M = 3.61, B = 2.24, s.e. = .16, p < .001). The heightened uncertainty predicted more financial work meaning (B = .20, s.e. = .10, p = .04), and no influence on non-financial work meaning (B = −.17, s.e. = .09, p =.06). More uncertainty also predicted more fear (B = .60, s.e. = .05, p < .001). Participants reported significantly more fear in the high unemployment condition (M = 5.93), compared to the low unemployment condition (M = 3.45, B = 1.10, s.e. = .17, p < .001). However, more fear was not related to financial (B = .06, s.e. = 10, p = .51) or non-financial work meanings (B = .07, s.e. = .09, p = .46). A mediation analysis with 5,000 resamples and bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals confirmed a significant indirect effect of the unemployment condition on financial work meaning through uncertainty (indirect effect = .45, s.e. = .22, 95% CI [.01, .89]). Moreover, when the direct link between unemployment and financial work meaning was included in the path analysis, the direct effect was significant (β = .62, p = .04), suggesting other mechanisms in addition to perceived uncertainty. presents the mediation results.

Figure 2. Mediation results for study 3.

The results of Study 3, which showed no significant mediation effects of fear, were inconsistent with those of Study 1. To investigate the possible reasons for this inconsistency, we re-ran the mediation model without uncertainty in Study 3. Mediation analysis with 5,000 resamples and bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals confirmed significant indirect effects from the unemployment condition to fear to more financial work meaning (indirect effect = .53, s.e. = .15, 95% CI [.24, .83]). However, the indirect effects through fear on non-financial work meaning were insignificant (indirect effect = .16, s.e. = .14, 95% CI [−.11, .43]). These findings were consistent with those of Study 1. Together, these results suggest that when fear was considered as the sole mediator, it mediated the effect of unemployment rate on financial work meaning. However, when experienced uncertainty was considered, the mediation effect of fear disappeared. Therefore, the findings suggest that uncertainty is a more important mediator in explaining the relationships between unemployment rate and work meanings.

Discussion

In Study 3, we manipulated participants’ perceptions of the unemployment rate by encouraging them to engage in a vivid imagination process. The results suggested that the perceived high unemployment rate leads to a greater focus on financial work meaning through an increased feeling of uncertainty. Fear was a less important mediator in explaining the relationship between economic condition and work meanings.

General discussion

The current research employs a wide range of data to test how and why national unemployment rate is related to work meaning. Study 1, which used archival data from responses collected from over 30 countries in 2005 and 2015, revealed that people in countries with higher unemployment rates reported less emphasis on non-financial work meaning and more focus on financial work meaning than those in countries with lower unemployment rates, although the effect on financial work meaning became insignificant at the .05 level after controls were included. The mediation analysis showed that fear mediated the relationship between national unemployment rate and financial work meaning, but not mediated the relationship between unemployment rate and non-financial work meaning. Study 2 used a within-country data set and found that Americans’ focus on financial work meaning was particularly high during the severe recession of the early 1980s when the national unemployment rate was at a historic high. In Study 3, we manipulated perceptions of unemployment rates and explored their impacts on perceptions of work meaning, and the mediating effects of fear and uncertainty. Participants in the high unemployment rate condition reported more emphasis on financial work meaning than those in the low unemployment rate condition. Uncertainty explained the effects when both mediators were included, not fear. The results from Study 3 revealed that uncertainty is a more important mediator than fear in explaining the effects of unemployment rates on work meaning.

Our findings make several theoretical contributions to the research on work meaning and the effects of macro-level economic factors on workplace outcomes. First, past research on the antecedents of work meaning has mainly focused on the role of proximal contextual signals or individual characteristics that influence people’s understanding of work meanings (Rosso et al., Citation2010). Previous research has shown that individuals’ perceptions of work meaning can change during actual economic distress. They tend to prioritize the financial function of when their financial needs increase, consistent with the literature on poverty as a “strong situation’ affecting attitudes and behaviours (Brief et al., Citation1995; Jahoda, Citation1981; Leana et al., Citation2009). Our findings took one step further and suggested that the broader economic condition could influence the extent to which employees focus on the monetary significance of their work, above and beyond the effect of their personal financial situation. This finding also supports the argument that the understanding of work meaning should not be isolated from the broader context in which the work exists (Bailey et al., Citation2019; Pratt & Ashforth, Citation2003) because how people construct the meaning of their work is partially a result of the context (Wrzesniewski et al., Citation2003).

Second, our findings provide further evidence for the influence of macro societal conditions on micro individual outcomes. Among the many societal factors that exist, the overall macroeconomic condition is arguably one of the most important for shaping psychological dynamics (Bianchi, Citation2013, Citation2016; Bianchi & Mohliver, Citation2016; Inglehart, Citation1990). This paper builds on a growing body of organizational research suggesting that individuals’ thoughts and behaviours at work are strongly influenced by the distal characteristics of the society in which they live (Bianchi, Citation2020) and adds to this line of research by demonstrating that the economy can also influence people’s basic perceptions of their work’s meaning. Additionally, our finding that a positive relationship exists between the national unemployment rate and financial work meaning is consistent with De Witte et al. (Citation2004) findings. This supports R. Inglehart and Abramson’s (Citation1994) argument on the negative impact of unemployment rates on postmaterialism and contradicts Clarke and Dutt’s (Citation1991) claim that a positive effect of unemployment rates on postmaterialism exists. Overall, our results provide further evidence for the ongoing debate on the effects of unemployment rates on postmaterialism.

Third, our findings directly speak to the argument that macro-level “turbulence” impacts people’s experience of their work. A very high national unemployment rate is an alarming signal of a society’s concerning financial situation. Our findings suggest that under such a financial crisis, people may view their job more as a way to make money. Although work serves both financial and non-financial functions, our research found that only financial work meaning received greater emphasis during economic hardship. This finding is consistent with our assumption that when unemployment rates are high, the financial benefits provided by work are perceived as scarcer, which leads to a greater emphasis on financial work meaning (Inglehart, Citation2008). Although the findings from the three studies collectively indicate a significant relationship between the unemployment rate and financial work meaning, this relationship varies based on the type of comparison. Specifically, it is significant without controls in between-country comparisons but requires controls to become significant in within-country comparisons. This intriguing observation suggests that between-country differences might account for a substantial variance in financial work meaning, rendering the effects of the unemployment rate insignificant once these factors are controlled. Conversely, within a single country, individual differences may initially obscure the impact of the unemployment rate. It is only after accounting for such individual variations (e.g., age and education) that the influence of this macro-level factor becomes apparent.

Our results also demonstrate the distinct effects of macroeconomic conditions on different dimensions of work meaning, highlighting the importance of examining work meaning through a dimensional lens rather than a continuum. Moreover, this finding also complements existing research on the prevalent effects of macroeconomic crises on individuals (Chatrakul Na Ayudhya et al., Citation2019; Conway et al., Citation2014; Cook et al., Citation2016) by showing that the national financial situation may fundamentally change how people view their work. This raises important questions about how managers can best support employee motivation during times of economic crisis (Zagelmeyer & Gollan, Citation2012).

In addition, the article adds to the ongoing dialogue about cross-national differences in work meaning. Two large projects have shed light on this topic, but they were unable to show why such differences existed. One project looked at the importance people assigned to their work roles compared to other roles in life (i.e., the work importance study [WIS]; Super & Šverko, Citation1995); the other studied work’s centrality (i.e., the meaning of working [MOW] study; MOW International Research Team, Citation1987). Both projects gave theoretical explanations for the observed differences, but neither provided evidence for the specific societal factors that influence work meaning. Our results help to explain some of the cross-national differences in perceptions of meaningful work. In addition, the study underscores the significance of examining additional societal-level factors as antecedents of work meaning. For instance, the concept of “welfare state regimes” (Arts & Gelissen, Citation2002) suggests that in societies with a more robust social safety net, such as the Nordic countries, individuals may perceive less uncertainty regarding unemployment rates since the social welfare system may shield them from severe financial distress caused by unemployment, ultimately reducing the impact of unemployment rates on financial work meaning. Consistent with the assumption, we also found that national education expenditure and health expenditure were both negatively related to financial work meaning. Future researchers can delve deeper into whether additional societal protective factors, such as employment protection legislation, active and passive labour market policies (Barbieri & Cutuli, Citation2016), can also mitigate the effects of a high unemployment rate on individuals’ reactions.

Moreover, our work provides initial evidence on the underlying mechanisms accounting for the effects of threatening situations on people’s work orientations. Sheldon and Kasser (Citation2008) found that when people feel threatened by immediate environmental factors, they place relatively more importance on financial concerns; their research, however, did not document the underlying processes responsible for the effect. Consistent with their findings, our paper showed that a distal environmental factor – a higher national unemployment rate – was associated with a greater focus on the financial meaning of work. In addition, we found that higher levels of uncertainty partially account for this relationship. We also found that uncertainty predicted fear, which is consistent with the literature on how cognitive job insecurity (i.e., perceived uncertainty) leads to emotional job insecurity (e.g., fear, anxiety, and worry etc.) (Jiang & Lavaysse, Citation2018). These findings suggest that helping employees manage their personal uncertainty may help to mitigate the effects of broader economic conditions.

Practical implications

Understanding how social and economic conditions influence employees is critical for leaders to successfully navigate their organization through a macroeconomic crisis. Our paper reveals that a high national unemployment rate can lead to a more financially focused and less non-financially focused construal of work meaning. Organizations should pay close attention to changes in employees’ construction of work meaning during these times, because low non-financial work meaning tends to predict reduced job satisfaction and lower performance (Allan et al., Citation2019). To influence employees’ perceptions of work during economic hardship, managers cannot change macro societal conditions, which are largely uncontrollable. Instead, they should focus on proactively creating a less ambiguous organizational environment that helps to alleviate the uncertainty experienced by employees during periods of high unemployment. Moreover, they could also consider granting employees more decision-making flexibility to allow them to perceive more opportunities in an uncertain world (Maley, Citation2019), which could in turn broaden their views on the possible non-financial meanings of their work.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations of this paper could stimulate further research on this topic. First, although the experimental design used in Study 3 ensured the internal validity of the study’s findings, its external validity may be limited. Future research could try other manipulations or quasi-experimental and longitudinal designs to enhance external validity when examining the causal role of unemployment rates. Secondly, while we identified uncertainty as the more significant mediator among the two proposed, our study did not encompass a comprehensive set of potential mechanisms. It is possible that other psychological mechanisms could be relevant in this context. Moreover, our analysis left a significant proportion of the covariance between the unemployment rate and work meanings unexplained. Therefore, future research could delve deeper into this subject and investigate other potential mediation mechanisms. Finally, it is worthwhile for future researchers to explore the boundary conditions of the relationships identified in this paper. For instance, if an individual’s personality fits with their job demands, non-financial work meanings may be more salient, even if the broader socioeconomic context promotes an emphasis on financial concerns (Barrick et al., Citation2013; Frieder et al., Citation2018). One’s personal financial situation and job characteristics may also serve as moderators in these relationships. For instance, wealthier individuals in jobs that emphasize more non-financial features may be more insulated from the impact of the unemployment rate on financial work meaning. Examining the role of potential moderating factors would help to provide a more nuanced understanding of the observed effect.

In conclusion, as an important indicator of a country’s economic condition, the national unemployment rate is related to people’s perceptions of financial work meaning, without controls when making between-country comparisons and with controls when making within-country comparisons. Such a relationship is partially due to the increased levels of uncertainty during economic downturns. Leaders who wish to engage their employees more effectively during challenging economic conditions should be aware of how and why the broader economic climate affects the experience of work meaning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Allan, B. A., Batz-Barbarich, C., Sterling, H. M., & Tay, L. (2019). Outcomes of Meaningful Work: A Meta‐Analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 500–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12406

- Anderson, C. J., & Potunsson, J. (2007). Workers, worries and welfare states: Social protection and job insecurity in 15 OECD countries. European Journal of Political Research, 46(2), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00692.x

- Artazcoz, L., Benach, J., Borrell, C., & Cortes, I. (2004). Unemployment and mental health: Understanding the interactions among gender, family roles, and social class. American Journal of Public Health, 94(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.1.82

- Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2002). Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state-of-the-art report. Journal of European Social Policy, 12(2), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952872002012002114

- Bailey, C., Lips-Wiersma, M., Madden, A., Yeoman, R., Thompson, M., & Chalofsky, N. (2019). The five paradoxes of meaningful work: Introduction to the special issue ‘meaningful work: Prospects for the 21st century’. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12422

- Barbieri, P., & Cutuli, G. (2016). Employment protection legislation, labour market dualism, and inequality in Europe. European Sociological Review, 32(4), 501–516. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv058

- Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Li, N. (2013). The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics. Academy of Management Review, 38(1), 132–153. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0479

- Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(4), 644–675. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094912

- Bianchi, E. C. (2013). The bright side of bad times: The affective advantages of entering the workforce in a recession. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(4), 587–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839213509590

- Bianchi, E. C. (2016). American individualism rises and falls with the economy: Cross-temporal evidence that individualism declines when the economy falters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(4), 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000114

- Bianchi, E. C. (2020). How the economy shapes the way we think about ourselves and others. Current Opinion in Psychology, 32, 120–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.007

- Bianchi, E. C., & Mohliver, A. (2016). Do good times breed cheats? Prosperous times have immediate and lasting implications for CEO misconduct. Organization Science, 27(6), 1488–1503. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1101

- Bloom, N. (2009). The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 77(3), 623–685.

- Brand, J. E. (2015). The far-reaching impact of job loss and unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043237

- Brief, A. P., Konovsky, M. A., George, J., Goodwin, R., & Link, K. (1995). Inferring the meaning of work from the effects of unemployment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(8), 693–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb01769.x

- Brym, R., Godbout, M., Hoffbauer, A., Menard, G., & Zhang, T. H. (2014). Social media in the 2011 Egyptian uprising. The British Journal of Sociology, 65(2), 266–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12080

- Buhr, K., & Dugas, M. J. (2002). The intolerance of uncertainty scale: Psychometric properties of the English version. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(8), 931–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00092-4

- Chatrakul Na Ayudhya, U., Prouska, R., & Beauregard, T. A. (2019). The impact of global economic crisis and austerity on quality of working life and work-life balance: A capabilities perspective. European Management Review, 16(4), 847–862. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12128

- Chattopadhyay, S., & Bianchi, E. C. (2020). Does the black/white wage gap widen during recessions? Work and Occupations, 48(3), 247–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888420968148

- Clarke, H. D., & Dutt, N. (1991). Measuring value change in Western industrialized societies: The impact of unemployment. American Political Science Review, 85(3), 905–920. https://doi.org/10.2307/1963855

- Conway, N., Kiefer, T., Hartley, J., & Briner, R. B. (2014). Doing more with less? Employee reactions to psychological contract breach via target similarity or spillover during public sector organisational change. British Journal of Management, 25(4), 737–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12041

- Cook, H., MacKenzie, R., & Forde, C. (2016). HRM and performance: The vulnerability of soft HRM practices during recession and retrenchment. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(4), 557–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12122

- Damasio, A. R., & Carvalho, G. B. (2013). The nature of feelings: Evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3403

- Dávalos, M. E., Fang, H., & French, M. T. (2012). Easing the pain of an economic downturn: Macroeconomic conditions and excessive alcohol consumption. Health Economics, 21(11), 1318–1335. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1788

- Debus, M. E., Probst, T. M., König, C. J., & Kleinmann, M. (2012). Catch me if I fall! Enacted uncertainty avoidance and the social safety net as country-level moderators in the job insecurity–job attitudes link. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 690–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027832

- De Witte, H., Halman, L., & Gelissen, J. (2004). European work orientations at the end of the twentieth century. Chapter 10, In Wils Arts & Loek Halman (Eds.), European values at the turn of the Millennium (pp. 255–279). Brill Publishers.

- Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 6(3–4), 169–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939208411068

- Frieder, R. E., Wang, G., & Oh, I. S. (2018). Linking job-relevant personality traits, transformational leadership, and job performance via perceived meaningfulness at work: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(3), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000274

- Goodman, C. R., & Shippy, R. A. (2002). Is it contagious? Affect similarity among spouses. Aging & Mental Health, 6(3), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860220142431

- Gray, J. A., & McNaughton, N. (2000). The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the Septo-Hippocampal System. Oxford University Press.

- Harpaz, I., & Fu, X. (2002). The structure of the meaning of work: A relative stability amidst change. Human Relations, 55(6), 639–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726702556002

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hu, J., & Hirsh, J. B. (2017). Accepting lower salaries for meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1649. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01649

- Inglehart, R. F. (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, R. F. (2008). Changing values among western publics from 1970 to 2006. West European Politics, 31(1–2), 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380701834747

- Inglehart, R., & Abramson, P. R. (1994). Economic security and value change. American Political Science Review, 88(2), 336–354. https://doi.org/10.2307/2944708

- Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 19–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240006500103

- Inglehart, R., Foa, R., Peterson, C., & Welzel, C. (2008). Development, freedom, and rising happiness: A global perspective (1981–2007). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(4), 264–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00078.x

- Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2007). Modernization. The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology.

- ISSP Research Group. (2013). International social survey programme: Work orientation III – ISSP 2005. GESIS Data Archive. ZA4350 Data file Version 2.0.0.

- Jahoda, M. (1981). Work, employment, and unemployment: Values, theories, and approaches in social research. American Psychologist, 36(2), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.184

- Jiang, L., & Lavaysse, L. M. (2018). Cognitive and affective job insecurity: A meta-analysis and a primary study. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2307–2342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318773853

- Jonas, E., McGregor, I., Klackl, J., Agroskin, D., Fritsche, I., Holbrook, C., & Quirin, M. (2014). Threat and defense: From anxiety to approach. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 49, pp. 219–286). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800052-6.00004-4

- Jones, S. R., & Riddell, W. C. (1999). The measurement of unemployment: An empirical approach. Econometrica, 67(1), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00007

- Kahn, L. B. (2010). The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy. Labour Economics, 17(2), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.09.002

- Kaplan, H. R., & Tausky, C. (1974). The meaning of work among the hard-core unemployed. Pacific Sociological Review, 17(2), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388341

- Lansdall-Welfare, T., Lampos, V., & Cristianini, N. (2012, April). Effects of the recession on public mood in the UK. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on World Wide Web, Lyon, France (pp. 1221–1226).

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press.

- Leana, C., Appelbaum, E., & Shevchuk, I. (2009). Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Academy of Management Journal, 52(6), 1169–1192. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.47084651

- Leary, M. R. (1983). A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9(3), 371–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167283093007

- LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to twenty questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Method, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642

- Lee, C., Huang, G. H., & Ashford, S. J. (2018). Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 335–359. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104651

- Lindsay, P., & Knox, W. E. (1984). Continuity and change in work values among young adults: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Sociology, 89(4), 918–931. https://doi.org/10.1086/227950

- Maley, J. F. (2019). Preserving employee capabilities in economic turbulence. Human Resource Management Journal, 29(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12211

- McAllister, A., Nylén, L., Backhans, M., Boye, K., Thielen, K., Whitehead, M., & Burström, B. (2015). Do ‘flexicurity’policies work for people with low education and health problems? A comparison of labour market policies and employment rates in Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom 1990–2010. International Journal of Health Services, 45(4), 679–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731415600408

- McNaughton, N., & Corr, P. J. (2004). A two-dimensional neuropsychology of defense: Fear/anxiety and defensive distance. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 28(3), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.005

- MOW International Research Team. (1987). The meaning of working. Academic Press.

- Nabi, R. L. (2009). Emotion and media effects. In R. L. Nabi & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of media processes and effects (pp. 205–221). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ng, W., & Diener, E. (2014). What matters to the rich and the poor? Subjective well-being, financial satisfaction, and postmaterialist needs across the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(2), 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036856

- Nord, W. R., Brief, A. P., Atieh, J. M., & Doherty, E. M. (1990). Studying meanings of work: The case of work values. In A. P. Brief & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Meanings of occupational work (pp. 21–64). Lexington Books.

- O’reilly, C. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1980). Job choice: The impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on subsequent satisfaction and commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65(5), 559–565. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.65.5.559

- Otto, K., Hoffman-Biencourt, A., & Mohr, G. (2010). If there a buffering effect of flexibility for job attitudes and work-related strain under conditions of high job insecurity and regional unemployment rate? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 32(4), 609–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X10388531

- Paulsen, N., Callan, V. J., Grice, T. A., Rooney, D., Gallois, C., Jones, E., Jimmieson, N. L., & Bordia, P. (2005). Job uncertainty and personal control during downsizing: A comparison of survivors and victims. Human Relations, 58(4), 463–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726705055033

- Podolny, J. M., Khurana, R., & Hill-Popper, M. (2005). Revisiting the meaning of leadership. Research in Organizational Behavior, 26, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(04)26001-4

- Pratt, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. (2003). Fostering meaningfulness in working and meaningfulness at work: An identity perspective. In K. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 309–327). Berrett-Koehler.

- Rodell, J. B. (2013). Finding meaning through volunteering: Why do employees volunteer and what does it mean for their jobs? Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1274–1294. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0611

- Ros, M., Schwartz, S. S., & Surkiss, S. (1999). Basic individual values, work values, and the meaning of work. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 48(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1999.tb00048.x

- Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Sablik, T. (2013, November 22). Recession of 1981–82. Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/recession_of_1981_82

- Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392563

- Shamir, B. (1991). Meaning, self and motivation in organizations. Organization Studies, 12(3), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069101200304

- Sheldon, K. M., & Kasser, T. (2008). Psychological threat and extrinsic goal striving. Motivation and Emotion, 32(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9081-5

- Shorrocks, A. (2009). On the measurement of unemployment. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 7(3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-008-9089-9

- Sirola, N., & Pitesa, M. (2018). The macroeconomic environment and the psychology of work evaluation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 144, 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.09.003

- Spreitzer, G. M., & Mishra, A. K. (2002). To stay or to go: Voluntary survivor turnover following an organizational downsizing. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 707–729. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.166

- Stam, K. (2015). The Moral Duty to Work. A Cross-National and Longitudinal Study of the Causes and Consequences of Work Ethic Values in Contemporary Society [ PhD defended at the Department of Sociology]. Tilburg University,

- Stavosky, J. M., & Borkovec, T. D. (1987). The phenomenon of worry: Theory, research, treatment and its implications for women. Women & Therapy, 6(3), 77–95. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015V06N03_07

- Steers, R. M., & Braunstein, D. N. (1976). A behaviorally-based measure of manifest needs in work settings. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 9(2), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(76)90083-X

- Super, D. E., & Šverko, B. E. (1995). Life roles, values, and careers: International findings of the work importance study. Jossey-Bass.

- Veenhoven, R. P. (1989). Did the crisis really hurt? Effects of the 1980–82 economic recession on satisfaction, mental health and mortality. University Press Rotterdam.

- Vohs, K. D., Mead, N., & Goode, M. (2006). The psychological consequences of money. Science, 314(5802), 1154–1156. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1132491

- World Bank. (2021, February). https://data.worldbank.org/

- Wrzesniewski, A., Dutton, J. E., & Debebe, G. (2003). Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 93–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25003-6