ABSTRACT

The current study examines how events external to organizations raise a challenge to perceptions of organizational identity continuity leading to a negative affective and attitudinal workforce response. This 5-wave study surveys full-time employees (N = 1309) from around the UK during a period of socio-political turmoil during negotiations of terms of withdrawal from the EU (Brexit). Drawing on Conservation of Resources Theory and Affective Events Theory we hypothesize that employees’ anticipation of change in organizational identity will lead to negative individual-level affective responses of job anxiety and a subsequent reduction in affective commitment. Utilizing a Random Intercept Cross Lagged Panel Model, the results show that within-person increases in perceptions of anticipated organizational identity change are followed by increases in job anxiety, which is followed by reductions in affective organizational commitment. Thus, the turbulent external context challenges employees’ enduring sense of organizational identity which can have profound effects on employees and their relationship with their employer.

Introduction

The literature focusing on organizational identity emphasizes that the enduring nature of an organization’s characteristics and attributes help form a stable collective sense of “who we are” as an organization (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985). However, there is also recognition that various forces can challenge these enduring features and enact pressure on organizational identities to change (Gioia et al., Citation2000, Citation2013). This change may be internally driven by organizational actors attempting to change the essence of the organization (Pratt, Citation2012; Shultz, Citation2016) or it may come from external pressures (Gioia et al., Citation2013; Phillips et al., Citation2016). Where change does occur however, this will have implications for employees. Albert and Whetten (Citation1985) highlight that “a loss of identity (in the sense of continuity over time) threatens an individual’s health” (p272). This argument has also been reinforced by a number of proponents of Social Identity Theory (e.g., Haslam et al., Citation2003; Jetten et al., Citation2002; van Dick et al., Citation2006; Van Knippenberg et al., Citation2002).

A question that remains unresolved in the literature, however, is whether and how changes in the external socio-political and economic context will exert change pressure on organizational identity and what implications this has for employees. Where the external context puts pressure on the organization’s continuity, employees are likely to perceive a sense of anticipated organizational identity change. A stable organizational identity that endures over time is considered important for employees. Given this, any change or pressure which threatens organizational identity continuity will likely translate into changes to employees’ health and well-being (van Dick et al., Citation2006). As employees’ beliefs about the organization’s characteristics make up the essence of its identity (Gioia et al., Citation2000), when employees anticipate that the organization is changing, to these employees the enduring nature of its identity is under threat; thus, they are likely to experience a state of identity threat (Petriglieri, Citation2011). If the wider context of the organization involves particular socio-political or economic change, this is likely to impact the organization’s enduring sense of identity, which is likely to have a profound impact on employees’ individual level beliefs and perceptions linked to an anticipation of change. We test this through the 18-months leading up to Brexit in the UK; a period of ongoing uncertainty for organizations (and employees) across the UK (and also for many in Europe), and an external context likely to be seen as a threat to organizational identity continuity.

The purpose of this paper is to test our proposition that, in an external context of socio-political turmoil, individual level employees are likely to perceive a sense of anticipated organizational identity change, which we define as: employees’ anticipation that key aspects which encompass the organizational identity will change in the future. We test the central proposition that anticipating a change in organizational identity (due to Brexit) will flow on and have a profound impact on both job anxiety states and the employee’s linkage with their organizations (in the form of affective organizational commitment).

We draw on and make an integrative contribution to both Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989) and Affective Events Theory (AET, Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996). We do this by explaining and demonstrating how the continuing context of (Brexit) uncertainty (detailed below) as an external work environment feature will lead to an affectively relevant work event, specifically fostering perceptions of anticipated organizational identity change and this is likely to manifest a sense of identity threat which will trigger job-related anxiety (as an affective reaction). Furthermore, we examine how job anxiety as an affective reaction is subsequently associated with a change in work attitudes (a reduction in affective commitment in this case); thus, we also make an empirical contribution by demonstrating a key theorized sequence proposed within Affective Events Theory (AET). Affective Events Theory (AET, Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996) theorizes how the external context and change-related work events trigger emotional reactions in employees, which in turn influence their attitudes and behaviours. The theory emphasizes the impact of external context, on shaping the emotional experiences of individuals at work and their subsequent outcomes. We empirically demonstrate a key theorized sequence proposed within the theory, that external work environment features, trigger work events, often related to change, which can foster affective reactions and impact work attitudes. Furthermore, AET incorporates time into an explanation of affective responses to events at work by suggesting that affect fluctuates over time and that these affective reactions can go on to have profound effects on work attitudes.

We provide some additional insight into possible temporal aspects of relationships between features of AET by exploring the temporal sequence of perceptions of anticipated organizational identity change as an affectively relevant work event, job-related anxiety as an affective reaction and reduction in affective commitment as a work attitude response. Thus, in accordance with AET, that includes the idea that context and change-related work events can influence affect and attitudes over time, we include a temporal aspect to our study to evidence (and test) the temporal sequence of affective reactions to work events. This provides important evidence for the temporal sequencing of unfolding theoretical processes included in AET. Notably, our study also makes a contribution to Conservation of Resources theory research as we highlight that identity continuity can be seen as an important personal resource. Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989) emphasizes that individuals strive to acquire, protect, and maintain personal resources to cope with stress and achieve well-being. According to COR Theory, stress arises when individuals perceive a threat of personal resource loss or experience actual resource depletion, leading to efforts to conserve and replenish these resources through adaptive or maladaptive coping strategies. The notion of personal resource refers to any asset, attribute, capability or characteristic that an individual possesses and that can be mobilized to cope with stress, achieve goals, and maintain well-being. Examples of personal resources include education, skills, knowledge, physical health, personal traits, status, self-efficacy and self-esteem (Hobfoll, Citation1989, 2012). These resources contribute to an individual’s ability to effectively navigate challenges and sustain their functioning in various domains of life. As discussed below, identity continuity is an important personal resource for individuals to be able to draw on to plan, function, predict and control aspects of their environment in times of transition or change. We are able to examine whether employees that experience an ongoing anticipation that their organizational identity will change (potentially threatening a loss to identity continuity as a personal resource) is associated with an ongoing change in job anxiety as an affective reaction.

Crucially, we examine job anxiety (Warr, Citation1990), as an affective response to the identity threatening anticipation of organizational identity change. We test whether this ongoing affective response has a negative impact on employees work attitudes, specifically employees’ ability and willingness to commit affectively to their organization. Thus, we theorize that an ongoing experience of identity threat will deplete identity continuity as a personal resource leading to an increase in job anxiety states as a negative affective response. We also argue that this is expected to undermine employees’ subsequent linkage with their employing organization in the form of a reduction in a core job attitude of affective organizational commitment. This reduction of affective commitment can be considered an identity threat reduction response (Petriglieri, Citation2011) where employees reduce the potential subjective importance of the threatened organizational identity by reducing their affective linkage to the organization.

In the current study therefore, we show how the core theoretical frameworks of COR and AET can help explain how ongoing events external to organizations can have negative consequences on employees. As discussed below, we draw on Petriglieri’s (Citation2011) identity threat response model by framing an anticipation of organizational identity change as a potential identity threat and we make a contribution to the field by integrating key tenets of both COR and AET. We demonstrate the important implications that follow from anticipated organizational identity change and how the external context can profoundly impact employees that includes increased job anxiety and a reduction in affective commitment with their employer. Thus, we provide a clear explanatory framework that helps provide insight into how external turmoil can impact employees by unsettling the enduring nature of organizational identities.

Brexit as a challenge to organizational identity

As the potential separation from the European Union (Brexit) unfolded, it likely challenged the make-up of the employee body that formed the “we” in organizational identities across the UK, with many EU citizens’ facing uncertainty around the right to live and work in the UK (affecting EU employees, and/or their families, colleagues, and friends). During this period, UK based employers to engage in careful communication and provide staff with support (e.g., legal advice) if their citizenship status meant that there was uncertainty around their right to continue working in the country post Brexit. This had workforce planning implications for UK employers who traditionally hired EU workers originating outside the UK; raising uncertainty around the ease and strategic case for retaining and continuing to hire EU citizens. This period of uncertainty also meant that the collective and shared identity of organizations who employed EU workers, their cohesive make-up and central essence, would have been challenged due to Brexit. Such a challenge would have led to a threat to identity continuity for employees.

Gioia et al. (Citation2000) and Gioia et al. (Citation2013) highlight that external organizational environment features and external pressures are important potential sources of organizational identity change. In the study’s context of Brexit these potential external pressures operate as a background context across the study’s timeline. Importantly, the pre-Brexit negotiations (and uncertainty associated with what it would involve for organizations) unfolded over time as we tracked employees across 18 months through this period (we set out the study’s associated timeline in ).

A key stream of research within the organizational identity field focusses on organizational identity change and considers the process of unfolding change over time (Dutton et al., Citation1994; Gioia et al., Citation2000). When discussing how an organization may manage or build a narrative around change in identity, a temporal component is implied. However, research exploring organizational identity change and how employees make sense of this change, often has a theory building focus rather than an empirical focus (e.g., Hatch & Shultz, Citation2002; Gioia et al., Citation2013) and empirical studies (either quantitative or qualitative) exploring change in organizational identity are usually conducted at one time point or, where data is collected over a given time period these studies rarely systematically, integrate time into the design or analyses. Whilst theory presented linked to change in organizational identity discusses the essential temporal element of organizational identity (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985; Shultz, Citation2016), to date the literature does not discuss expected timelines of change in organizational identity. In the current study we specifically focus on a time-period in our longitudinal data collection (18 months) that will enable us to access changing perceptions and employee responses across the protracted sequence of (potentially tumultuous) external events. In this context the temporal span of Brexit negotiations and uncertainty that unfold over a period of many months is integrated into the study as an external background contextual variable.

Much of the existing theorizing and research in the area of organizational identity change explores how and why organizational identity may change and how actors present or make sense of unfolding change (Gioia et al., Citation2013; Pratt et al., Citation2016) and some recent research has explored the anticipated outcomes of organizational identity change and identity threat (Onken-Menke et al., Citation2022). However, to date research has not explored or tracked change in employee perceptions of anticipated change in organizational identity over time nor the unfolding impact of employees’ anticipation of this change over time.

Given that organizational identity and employees’ links with the organizational entity will be an important component of employees’ sense of self, continuity in this will be important for individual self-continuity (Spears, Citation2008) and for their well-being (Haslam et al., Citation2003). Where employees anticipate a change in organizational identity, this is likely to be appraised as a potential threat to organizational identity continuity, and potentially individual identity continuity. Therefore, this sense of anticipation in organizational identity change is likely to be perceived as an identity threat (Petriglieri, Citation2011), in the current study we therefore treat this as a proxy of identity threat. Assuming that anticipated change in organizational identity as a potential identity threat is likely to have a profound impact on employees, it is important to be able to document and demonstrate this. Here, we suggest and test whether employees’ perceptions of anticipated change in organizational identity over time, and change in this, will have profound effects on affective states of job anxiety, and subsequently employees’ commitment to their organization. This endeavour is important as we provide insight into how processes of employee responses unfold over time in the potentially tumultuous context of ongoing organizational identity change pressures. Showing evidence of the psychological impact that this has on employees is important; it is also important to understand the (potential causal) sequence of theory-linked individual level responses to such context.

Anticipated change in organizational identity and affective responses

It is well-established that general organizational change can negatively impact employees’ affective states, such as increasing anxiety (Miller & Monge, Citation1985), possibly due to an associated threat to organizational identity (Argyris, Citation1990; Huy, Citation2002). This is consistent with Albert and Whetten’s (Citation1985) suggestion that a potential loss of or threat to organizational identity is expected to negatively impact individual level well-being. Indeed, having identity-based linkages buffer against uncertainty and change (Jetten et al., Citation2012). Recently, Onken-Menke et al. (Citation2022) show that where organizations are under identity threat, this can influence employees’ perceptions of features of the organizational identity, this is also linked to employees’ anticipated sense of continuity and states of employee well-being (in the form of anticipated self-esteem). Key with the current study however, is that we expect employees to respond to the tumultuous external events of the pre-Brexit negotiations by anticipating a future change in their employer’s organizational identity and this can be seen as a potential stressor (Cavanaugh et al., Citation2000) for employees. That is, this anticipated change in organizational identity, and any increase in this anticipation, will threaten a sense of identity related continuity experienced by employees and this individual anticipation of organizational identity change acts as a potential stressor. This accords with Petriglieri (Citation2011), who argues that where employees experience a sense of identity threat, this is a potential stressor, and it is likely to lead to a stress response.

Petriglieri (Citation2011) draws on Lazarus and Folkman’s (Citation1984) stress appraisal model to explain the potential impact that identity threat can have and argues that employees’ primary appraisal response to experiencing ongoing identity threat is likely to lead to a stress response. Petriglieri (Citation2011) suggests that following a secondary appraisal process, assessing coping resources and coping opportunities, this response may manifest in a self-protective coping response that could include identity protection or reconstruction (in various forms). Specifically, in the current context, we argue that an ongoing experience of anticipated change in organizational identity is likely to be experienced as identity threatening and this identity threat is likely to manifest in job anxiety as an affective response. Thus, we draw on Petriglieri (Citation2011) to help explain why anticipated change in organizational identity is likely to lead to job anxiety. Importantly, our theorizing accords with core tenets of Affective Events Theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996). The theory specifically argues that external work environment features and subsequent work-related events can lead to affective reactions in employees that impact their work attitudes and affect driven behaviours (Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996).

Our study is situated within a Brexit-related external context, which we consider a work environment feature that will influence employees’ sense of anticipation of organizational identity change as a proximal work event; this anticipation of organizational identity change will then foster a subsequent affective response. The Brexit context is therefore a distal external event that ultimately fosters an individual level affective employee response. Our study contributes to the theoretical framework of Affective Events Theory as the Brexit context is demonstration and an applied example of where certain external organizational events can lead to an affective response with employees, which is likely to impact subsequent job attitudes.

In the context of the identity threat linked response to anticipated organizational identity change, Conservation of Resources (Hobfoll, Citation1989) is also a useful theoretical framework that can be drawn on to help explain why this external event-driven potential identity threat may lead to negative affective responses.

As identity theorists have argued (e.g., Spears, Citation2008), identity continuity, or a sense of self that endures over time, is important to individuals as it “allows us to function as integrated agents” (p.254). Importantly, some aspect of our self-identity and self-continuity will be determined by, or embedded within, a group or collective context (such as organizational identity in the case of our study). Crucially, self-continuity is important and necessary for individuals to be able to plan, function, predict and control aspects of our environment (Spears, Citation2008). Thus, identity continuity is an important personal resource that individuals can draw on to help plan and predict in times of transition or change. As Hobfoll (Citation1989) argued within Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989), when individuals experience an ongoing threat to personal resources or a potential resource loss (in this case, a threat to continuity in identity as a resource), this can lead to a psychological stress-based secondary appraisal response as individuals will be concerned that they cannot draw on this resource to cope with future situations. Hobfoll (Citation1989), draws on Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) stress appraisal model in explaining how a threat to resource loss will lead to a stress response. As mentioned above, Petriglieri (Citation2011) identifies identity threat as a potential stressor and also draws on Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) stress appraisal model to explain a stress-based response to identity threat.

In highlighting that identity continuity can be seen as a personal resource, we contribute to COR theory by integrating existing theorizing set out by Petriglieri (Citation2011) of the potential impact of identity threat; a threat to identity continuity can be seen as a threat to an important personal resource. Thus, we argue that the threat of identity resource loss will foster a stress based primary and subsequent secondary appraisal response and that this appraisal response will foster an affective reaction, as argued this also contributes to Affective Events Theory as it helps provide an applied context that serves as an example of the core theoretical propositions of AET. Thus, we help integrate tenets of theorizing set out by both COR and AET. As mentioned above, we argue that the manifestation of such an affective response to potential identity continuity threat will take the form of job-related anxiety. Thus, we suggest that in the context of Brexit, employees’ beliefs and anticipation of Brexit-related organizational identity change are likely to increase job-related anxiety over time. Thus:

Hypothesis 1:

Increases over time in anticipated organizational identity change will be associated with a subsequent increase in job anxiety, specifically this association will be in the form of a positive cross lagged relationship.

Job anxiety states and affective commitment

In the current study therefore, we examine employees’ affective response to identity threat linked to anticipated organizational identity change. The affective response that we focus on is an ongoing negative affective state of job anxiety, a manifestation of negative job-related affective state Warr (Citation1990). We specifically argue that a job-related anxiety response will be fostered by the negative (primary) appraisal experienced with an ongoing threat to identity continuity as a resource (linked to Conservation of Resource theory, Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). This threat of resource loss will manifest as an ongoing state of job anxiety. Importantly, an ongoing state of job anxiety represents a negative job-related affective state (War, Citation1990). Rodell and Judge (Citation2009) showed that anxiety can lead to negative job outcomes (such as citizenship). Along with these authors and also Vandenberghe et al. (Citation2011), we draw on Affective Events Theory (AET; Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996) and argue that the affective states of job anxiety (fostered by anticipated organizational identity change) will frame and influence employees’ outcomes and job attitudes; specifically, that higher job anxiety will be associated with lower subsequent levels of affective organizational commitment. As Petriglieri (Citation2011), argues, when employees’ identities are under threat this will foster a stress-based psychological response (in the case of the current study, job anxiety). If the threat persists, a response may well involve identity regulation which may lead to employees’ adjusting or reducing the importance of the threatened identity, it may even lead to psychological identity exit as a form of self-protection. Thus, anticipated organizational identity change can be considered an individual response to an organizational level linked event that fosters an individual level affective reaction (in this case job anxiety states). This will then impact employees’ affective organizational commitment, specifically a reduction in commitment to the organization as a (self-protective) form of identity regulation (Petriglieri, Citation2011). For such a proposition we can also draw on arguments associated with Conservation of Resources theory, proponents of which stress that if individuals lose or expend resources over time, this can have profound negative consequences for employees (Hobfoll, Citation1989).

In a longitudinal study utilizing cross-lagged analyses, Hakanen et al. (Citation2008) showed that negative affective states such as low engagement and higher burnout are (subsequently) related to reduced commitment over time, and COR can help explain such a finding. We suggest that ongoing energy depletion at work fostered by an ongoing experience of a threat to identity continuity as a personal resource, will impact employees’ job attitudes, specifically it will hinder their willingness and ability to affectively commit to their employing organization. Therefore, drawing on both Affective Events Theory and Conservation of Resources theory, we argue that ongoing experiences of negative affective states in the form of increased job anxiety (that follow on from increased anticipation of organizational identity change), will be followed by a subsequent reduction in affective commitment. Thus,

Hypothesis 2:

Increases in levels of job anxiety will be associated with a subsequent decrease in affective commitment; specifically, this will be in the form of a negative cross-lagged relationship.

Perceived organizational identity change, job anxiety & affective organizational commitment

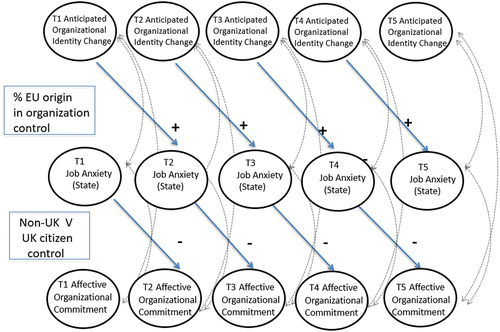

We argue that Brexit as an external background contextual event would foster or place organizational identity under change pressure and employees will anticipate potential change in these organizational level identities which fosters (in accordance with Conservation of Resources theory) a stress-based job anxiety response due to the ongoing threat of a loss of identity continuity as a personal resource. Furthermore, the individual level reaction to this threat of resource loss will manifest as a (negative) affective response (according with Affective Events Theory) and will impact affective employee well-being in the form of increased job anxiety. In addition, this individual affective response will go on to (subsequently) negatively impact an important employee work attitude, that of affective organizational commitment. Importantly, we need to recognize that the flow of theoretical propositions presented here consist of a mediating sequence where perceptions of anticipated organizational identity change will lead to negative affective well-being states of job anxiety, and this will then flow on to have a negative impact on affective commitment (see ). Given the nature of this theorized sequential flow, we propose the following hypotheses:

Figure 1. Proposed model of relationship between anticipated organizational identity change, job anxiety and affective organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 3:

There will be an indirect relationship between increase in anticipated organizational identity change and decreases in affective commitment via a sequence of cross-lagged relationships: namely from increases in anticipated organizational identity change to subsequent increases in job anxiety, and then from higher job anxiety states to subsequent affective commitment (each time controlling for prior states/perceptions).

Temporal dynamics

Given the dynamic nature of the process leading up to Brexit, fluctuations in the variables of interest and in their associations are possible. Thus, to test whether the direction of the effects flow as hypothesized above (i.e., from organizational identity change perceptions to subsequent job anxiety, which will be followed by a reduction in affective commitment), we employ a longitudinal design. Importantly, we test this proposition using Random Intercept Cross Lagged Panel Modelling (RICLPM, Hamaker et al., Citation2015) to help isolate and identify how and whether the longitudinal interrelationships flow in the expected direction. The RICLPM modelling approach has an advantage over previous forms of cross-lagged panel modelling as it can disentangle stable-between person differences from within person processes and can explicate between person differences and intra-person changes or fluctuations (Hamaker et al., Citation2015). These temporal change features have been identified by researchers (e.g., Sonnentag, Citation2015) as being important to understand temporal changes in well-being; which as discussed is a focal construct in our model.

Macro context features: UK citizenship and proportion of EU workforce as covariates

Whilst we indicate that anticipated organizational identity change is expected to impact employees, other specific Brexit related factors will have the potential to drive or influence employee responses. One of these is the citizenship status of the participants. Due to immigration threat associated with the uncertainties around Brexit, the citizenship status of the participants may have an underlying influence on their perceptions and affective well-being states. For example, those without UK citizenship status may be more likely to feel a greater sense of anticipated organizational identity change, have higher levels of job anxiety and (as a consequence) have lower levels of organizational commitment because Brexit placed these employees in a heightened state of uncertainty and potential job insecurity during a period where the UK government was not being clear about the status of non-UK EU citizens (or general immigration policies post-Brexit). Thus:

Hypothesis 4:

Employees without UK citizenship status will be a) more likely to express anticipated organizational identity change, b) more likely to exhibit higher job anxiety states, and c) more likely to show lower levels of affective commitment.

A further contextual influence on perceived organizational identity change is likely to be the proportion of EU (non-UK) members employed within an organization’s workforce. The proportion of an organization directly affected by any change to immigration legislation linked with Brexit will be greater where there is a greater proportion of the workforce made up of EU workers. It follows that there would be a greater potential for employees to perceive that their organizational identity will change because of Brexit (and the UK/EU profile of the work force) in organizations that have a greater proportion of EU (non-UK) members. Thus, given these arguments we also propose the following:

Hypothesis 5:

There will be a positive relationship between the proportion of EU (non-UK) employees working in the respondents’ organization and their levels of anticipated organizational identity change.

We will include these key covariates in our main cross-lagged model to control for their effect when testing for our hypothesized cross-lagged relationships.

Context and timeline

We set out the study’s timeline (and associated key Brexit related events) graphically in .

The Brexit referendum occurred in 23 June 2016, Article 50 (Britain’s formal legal declaration giving 2 years’ notice of intent to withdraw from the EU) was triggered on 29 March 2017. Our first wave of data collection was initiated a year after article 50 was triggered and a year before the proposed (initial) exit date (29 March 2019). We continued collecting further waves quarterly following this. A number of Brexit related events occurred during the 5 waves of data collection that we note down in the timeline. This included a government announcement between Wave 1 and Wave 2 of a “settled status” scheme where EU citizens who had been in the UK for more than 5 years could apply for indefinite right to remain in the UK – this in effect gave an initial commitment to allow EU (non-UK) workers to be able to stay in the UK after Brexit (to 31 October 2019), which the government reassured would remain in place even in the event of a no-deal Brexit (i.e., if the UK were to leave the EU without a withdrawal agreement). Between Wave 2 and 3 a number of government ministers resigned because they did not agree with the government’s decision to pursue a Brexit deal. Between Waves 3 and 4 a number of proposed Brexit deals were rejected and ultimately the Brexit date was extended. Between Wave 4 and 5 the Prime Minister resigned, and the government party had a leadership election which occurred around the time of Wave 5 where a new prime minister was elected by the party in power (not via general election). Thus, during the period that spanned the 5 waves of data collection, a range of different political events occurred that fed a continuing period of Brexit related socio-political (and economic) turbulence. Note that the data collection was finalized before the COVID-19 pandemic began.

Method

Participants, design, and procedure

We utilized an online crowdsource platform (Prolific) to collect data. We restricted our participant pool to those who lived in the UK and were employed in full-time employment. A unique advantage of using this population is that participants are drawn from all around the UK (our 1309 participants were located in more than 300 different cities and towns across the UK), and worked in a variety of jobs (many hundreds of different job roles were indicated by participants; e.g., “train driver”, “plumber”, “planning manager”, “customer service advisor”). In the first wave we targeted recruitment at participants who were born in the UK (400 participants), those who were born within the EU but outside the UK (400), and participants who were originally from outside the EU (100) as a comparator condition. After removing participants with incomplete responses, the final T1 sample included 697 full-time employees, 365 were born in the UK, 245 were born in Europe but outside the UK and 87 were born outside of Europe. In total 301 indicated that they did not have UK citizenship, 41 had dual citizenship (including UK), and 355 indicated that they were a UK citizen. In further waves we invited previous respondents to participate again. At each wave we opened the invite up to 250 more possible participants to supplement the responses in samples each wave; as the repeated responses were not predictable the response rate varied at each wave. In total we received 1309 responses across the 5 waves and 608 of these (46.4% of the total sample) were born in the UK, 498 (38%) were born in Europe but outside the UK and 203 (15.5%) were born outside of Europe. Of the total sample the within wave samples were 697, 511, 674, 508 and 629 T1-T5 respectively. In total 171 participants completed all 5 waves of the surveys (which amounted to a potential listwise panel response rate of 21%), 113 completed only 4 waves, 231 only three waves, 225 only two and 569 completed only one wave of surveys. The response rates varied depending on the particular combination of wave completions. However, of those who completed Wave 1 and went on to complete a second wave: 409 responded at Wave 2 (51% T1 + 1 wave panel response rate), 346 responded at Wave 3 (43% T1 + 1 wave panel response rate), 303 at Wave 4 (38%), 243 at Wave 5 (30%), 283 completed the first three waves (35% T1 + 2 wave panel response rate) and 210 completed the first 4 waves (26% T1 + 3 wave panel response rate). Note that the FIML method of estimation utilizes all data available for particular paths, therefore the sample drawn on to estimate specific parameters will vary depending upon the wave combinations. Details of the sample for particular coefficient combinations are included in the supplemental online material ().

Table 1. Correlations between anticipated organizational identity change (AOI Change), job anxiety, affective organizational commitment and control variables with reliability statistics and means.

Measures

T1–T5 panel variables

Anticipated organizational identity change

To measure anticipated (Brexit-related) Organizational identity change we drew on items used by Van Knippenberg et al. (Citation2002), and M. R. Edwards and Edwards (Citation2012) who explored aspects of organizational identity change linked to pre- and post-merger/acquisition (M&A) organizations. These authors focussed on continuity between pre- and post- M&A organizations, however, to emphasize the change aspect we refer to the organizational being different after Brexit on dimensions of “culture”, “characteristics” and “how things are done” (which, we argue, cover key aspects of the organization’s identity, based on Albert & Whetten, Citation1985). Participants were asked “Please think about what you anticipate your organization to look like after Brexit, to what extent do you agree with the following. After Brexit…” and the following items were presented with a 1–5 strongly disagree to strongly agree scale: “My organization will have a different culture.”, “My organization will have different characteristics than it does now”, “People in my organization will work in different ways than they do now”.

Job anxiety

Three items were used to measure job anxiety specifically using Warr’s (Citation1990) job anxiety sub-component of the affective well-being measure. Employees were asked to think of the past few weeks, how much of the time their job has made them feel the following: “tense”, “uneasy”, “worried”, with a 1–6 (never-all of the time) scale.

Affective commitment

Four items were used to measure affective commitment drawn from Allen and Meyer’s (Citation1990) scale. Example items include “This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me”, “I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organization”, “I feel emotionally attached to this organization”, and “I feel ‘part of the family’ at my organization”. A 1–5 (strongly disagree-strongly agree) response scale was used.

Brexit contextual variables (covariates)

Proportion of EU employees

Participants were asked to identify the proportion of colleagues who were UK, EU (non-UK) and International (non-EU and non-UK) citizens. They were asked to indicate a (rough) percentage for each group, using a slider scale. Because we are focusing on EU (non-UK) members, for this study we just used the answer referring to “European (non-UK citizens)” as a measure.

UK citizenship

Participants were asked “What is your nationality?” and were presented with three options: “UK citizen”, “Dual citizenship – UK citizen + another:” and: “Not UK citizen. Other”. For the purposes of the analyses we combined the UK citizen and dual citizenship question on the bases that these participants all had UK citizenship. We then coded this variable as 0 = “no-UK citizenship” and 1=”UK citizenship”.

Analytical approach

We had various sub samples within our study: some participants took part on one occasion only, some on two occasions, some on three, some four and some five. The strict list-wise five wave panel would have restricted the sample size to 171, however, we were able to utilize the entire sample. The treatment of missing cases in longitudinal research is discussed by Newman (Citation2014) who suggests that techniques should be used to utilize as much of a sample as possible. We use a Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation procedure with Mplus (with Missing At Random – MAR – assumptions, Little & Rubin, Citation1987) given that utilizing an entire longitudinal dataset has many advantages over restricting samples to less representative list-wise deletion sub-populations (Wang et al., Citation2013). Our analytic approach took two main steps. Firstly, we examined the study’s focal measures using Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA); this included invariance testing (Ployhart & Vandenberg, Citation2010) to check for structural integrity over the five waves. Once the measurement model was confirmed we created composite variables, with which we obtained descriptive statistics and conducted Random Intercept Cross Lagged Panel Modelling (RICLPM), an approach that is useful when researchers are interested in identifying potential directional flows or influences between variables over time (Hamaker et al., Citation2015). Importantly, RICLPM is able to isolate the earlier to later cross-wave relationships between potential independent and dependent variables specifically linked to within person relationships (which traditional cross-lagged panel models are unable to do, Hamaker et al., Citation2015). Thus RICLPM is able to isolate stable between person relationships across constructs and also identify relationships across these constructs that take into account states or perceptions that change or fluctuate within person over time. Importantly, we are able to include an unmeasured control for all stable unmeasured covariates that impact anticipated organizational identity change demographic factors) by removing between person stable differences (Masselink et al., Citation2018).

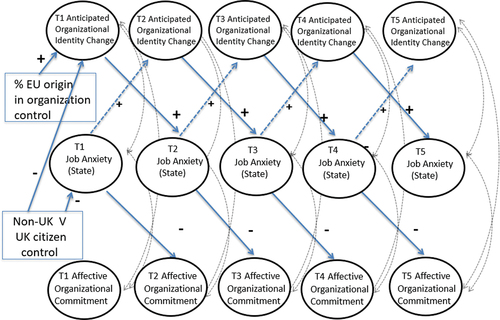

Thus, in the current study we set up a 5-wave RICLPM that incorporates stable between person relationships and state like change relationships between anticipated organizational identity change, job anxiety states and affective organizational commitment. Such a model allows a latent version of each within wave construct to correlate with the two other within wave constructs and be regressed on to an earlier version (one wave previous) of that construct as well as the two earlier (one wave previous) versions of the two other study constructs ( shows a diagrammatic example of the model with two variables).

Figure 3. RICLPM – Example of the model showing relationship between two key variables of anticipated organizational identity change and job anxiety over five time points. Time points are indicated by T1-T5.

The model also forms a latent variable that represents a stable between person measure of each construct (regressed onto each person’s measure across 5 waves). With these analyses we impose equality constraints on stability coefficients and cross-lagged effects (Hamaker et al., Citation2015), enabling us to test and obtain aggregate coefficients of the cross-lagged effects over multiple waves.Footnote1

Results

Measurement model testing

As initial model testing we conducted a series of analyses to test the structural validity of our core measure of anticipated change in organizational identity. As mentioned above we use the above anticipated organizational identity change to measure this construct across 5-waves based on measures used in research set in a merger change context (M. R. Edwards & Edwards, Citation2012; Van Knippenberg et al., Citation2002). A potential limitation with this measure is that it does not specifically make reference to specific organizational identity components, it does however refer to anticipated change in key aspects: the organization’s characteristics, culture and ways of doing things. These cover a wide scope and should represent the key essence of organizational identity change. As a validity check however, in supplementary analyses we conducted an additional survey of (N = 243), drawn from the same population (prolific.co) and asked four additional questions on anticipated organizational identity change based on items drawn from the Kreiner and Ashforth (Citation2004) measure of organizational identity strength. These were: “After Brexit … ” … “my organizations sense of purpose will change”; “There will be a reduced sense of unity in my organization”; the vision of the organization will change” and “the mission of the organization will change”. Importantly, when we carried out exploratory factor analyses with these 7 items, the four items plus our anticipated organizational identity change measure all factored into a single measure with loadings ranging from 0.830 to 0.916 (see Table 9 in the online supplemental material). Thus, we can be comfortable drawing on organizational identity theory when discussing implications of anticipated organizational identity change. The Reliability of this shorter 3-item scale was strong, Cronbach Alpha = 0.916.

As an initial first stage testing of the longitudinal measurement model we carried out Confirmatory Factor Analyses with the 5-waves of anticipated organizational identity change; with each factor representing a 3-item anticipated organizational identity change measure collected at each time point, we set this model to include autocorrelated residuals with the repeated items. This five-factor model fit the data well (X2 = 89.119, df = 50; X2/df = 1.782, RMSEA = 0.024; CFI = 0.994; TLI = 0.987; SRMR = 0.036). The item loadings of the organizational identity change latent variables were each on or above 0.771, 0.796, 0.786, 0.841 and 0.762 at T1, T2, T3, T4 and T5 respectively. All Cronbach Alphas were above 0.82. A five-factor job anxiety Time 1-T5 model also fit the data well (X2 = 61.927, df = 50; X2/df = 1.24, RMSEA = 0.013; CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.996; SRMR = 0.025, with all loadings above 0.820 in any wave), as did a five-factor Affective Organizational Commitment model (X2 = 367.00, df = 120; X2/df = 3.06, RMSEA = 0.040; CFI = 0.981; TLI = 0.969; SRMR = 0.027 with all loadings above 0.790 in any wave).

Full T1-T5 measurement model

We tested a five-wave measurement model with the three longitudinal variables (anticipated organizational identity change, job anxiety, and affective commitment T1-T5) as separate variables whilst auto-correlating the errors of repeated items. This fifteen-factor model fit the data well (X2 = 1556.60, df = 970; X2/df = 1.60, RMSEA = 0.021; CFI = 0.977; TLI = 0.971; SRMR = 0.035). The item loadings of the organizational identity change latent variables were each on or above 0.773, 0.799, 0.789, 0.840 and 0.763 at T1, T2, T3, T4 and T5 respectively; the loadings of the job anxiety items were on or above 0.824, .832, .820, .850 and .819 at T1, T2, T3, T4 and T5 respectively; the loadings of the affective commitment items factors were on or above 0.795, 0.827, 0.820, 0.800 and 0.811 at T1, T2, T3, T4 and T5 respectively. To test for longitudinal invariance the 15 factor configural model was compared with a metric-invariant measurement model that constrained the factor loadings to be equal within the corresponding latent factors across the 5 waves for each variable in turn. The model that fixed the factor loadings of the job anxiety measures to be equal over time did not show a significant reduction in fit (X2 = 1562.536, df = 978, X2diff = 6.741, df diff = 8, p=.565) nor did the model that fixed the affective commitment loadings to equality (X2 = 1574.104, df = 982; X2diff = 17.501, df diff = 12, p=.132) or the anticipated organizational identity change model that fixed the loadings to equality (X2 = 1570.60, df = 978; X2diff = 14.0, df diff = 8, p=.082). After confirming the validity of the study’s measurement model, we ran reliability analyses on each of the measures at each time point. The Cronbach Alphas are presented in . All measures are found to be reliable with the measures of anticipated organizational identity change coefficients all being above 0.88, the job anxiety all being above 0.88 and affective organizational commitment being above 0.92.

Descriptives

Correlations between all of the study’s focal variables are set out in , along with means, standard deviations and reliability coefficients for all variables.

Random intercept cross lagged panel model

sets out the main results of the RICLPM, including the within person stability and cross-lagged relationships, within wave correlations and between-person (stable trait like) correlations.

Table 2. Summary of Model 1 – Autoregressive, Random Intercept-Cross-Lagged Panel Model Pathways and within wave correlations.

Within and between person relationships

As presented in , there were two significant within person aggregate stability coefficients (carry over effects, Hamaker et al., Citation2015) over five waves for anticipated organizational identity change and affective commitment indicating that where respondents show a higher than expected increase or decrease of both these perceptions/attitudes, these effects carry over to a later waves.

The significant stability (unstandardized beta) coefficients are: anticipated organizational identity change B = .079 (SE = .039), p = .042 and affective commitment B = .080 (SE = .040), p = .044. The job anxiety stability coefficient was not significant, indicating that within person fluctuations on this did not maintain/were not stable over time B = .015 (SE = .037), p = .676. Of the crossed lagged pathways, there was a significant positive cross-lagged relationship between earlier states of anticipated organizational identity change and change in job anxiety (B = .093 (SE = .034), p = .006, supporting Hypothesis 1). Importantly, the model shows a reciprocal (but weaker) relationship between job anxiety and later states of anticipated organizational identity change (B = .070 (SE = .034), p = .038). In addition to this, the model shows that earlier increases in job anxiety significantly predict reductions in later affective commitment (B = −.072 (SE = .029), p = .013), supporting Hypothesis 2 (see ). Note that the terms “higher” or an “increase” here are relative to the person’s between person stability on these factors (see Hamaker et al., Citation2015 for a discussion on this).

Figure 4. RICLPM Results showing the nature of the significant within person relationships between anticipated organizational identity change, job anxiety states and affective organizational commitment (with controls).

The remaining cross-lagged relationships tested in the model are not significant. Thus, results provide evidence that increased anticipated organizational identity change had a negative impact on subsequent job anxiety, which in turn had a detrimental impact on affective commitment. The results also show that within wave relationships (indicating simultaneous fluctuations) between anticipated organizational identity change and job anxiety are not always significant, in two of the five waves these fail to reach significance; they do however show positive relationships across wave 2, 4 and 5. This highlights the turmoil and changing nature of the study’s context, where temporal events may lead to increases and decreases in these constructs at the same time. Similarly, the within wave correlations between anticipated organizational identity change and affective commitment are non-significant in three of the five waves, though job anxiety and affective commitment correlate within the waves in four of the five waves. Interestingly, the between person relationships between anticipated organizational identity change and affective commitment are also not significant. However, people who generally have higher levels of job anxiety also tend to report higher levels of anticipated organizational identity change (r = .207, SE = .045, p < .001) and lower levels of affective commitment (r =-.232, SE = .039, p < .001).

Indirect effects of anticipated organizational identity change on affective commitment via job anxiety states

We tested the hypothesized indirect cross-lagged relationship between anticipated organizational identity change ➔ job anxiety ➔ affective commitment (Hypothesis 3). For these indirect effects we produced Bootstrapped (1000) indirect effects with bias corrected confidence intervals. See for the results. The key predicted indirect cross-lagged effect was significant estimate = −0.007; 95% lower level confidence interval =-0.018 and upper level = −0.001. We also tested all other possible indirect cross-lagged effects using combinations of the three variables (see ) and no other sequence of indirect effects was significant. Thus, Hypothesis 3 has been supported.

Table 3. Boot-strapped Indirect Cross-Lagged model with Bias Corrected Confidence intervals.

UK citizenship status and % of EU members in the organization

Included as part of the RICLPM, each latent variable measure across the T1-T5 waves were regressed onto the two control variables of UK citizenship status and percent of the organization who are EU (non-UK) employees. The regression coefficients are presented in . UK citizenship and percent-EU were significantly and positively related to anticipated organizational identity change at waves 1, 2 and 3, (T1 β = .200, SE = .048, p < .001; T2 β = .216, SE = .057, p < .001; T3 β = .153, SE = .051, p = .003). The coefficients for these relationships at wave 4 (right after the agreed first extension to Brexit between the UK and EU) and 5 (3 months ahead the second Brexit date) were both also positive but did not reach the p < .05 level of significance (T4 β = .098, SE = .054, p = .070; T5 β = .104, SE = .055, p = .059). The proportion of EU workers in the organization also predicts T5 commitment, showing a negative relationship (β= −.148, SE = .061, p = .016). Citizenship status showed a significant positive relationship with affective commitment at Wave 1 and wave 4 (T1 β = .140, SE = .055, p = .015; T4 β = .120, SE = .057, p = .037) and a negative relationship with organizational identity change at Waves 2, 3 and 5 (T2 β = −.117, SE = .055, p = .035; T3 β = −.125, SE = .050, p = .013; T5 β = −.116, SE = .053, p = .028) and job anxiety at Waves 1 and 4 (T1 β = −.182, SE = .050, p < .001, T4 β = −.141, SE = .056, p = .012). Thus, those with UK citizenship showed lower levels of anticipated organizational identity change, less job anxiety and higher affective commitment. However, these relationships do not consistently reach significance in every wave and thus their influence varied according to the different Brexit-related political events that occurred between waves.

Table 4. Summary of relationships between Proportion of EU membership and Citizenship status on each wave.

As an additional analysis to test the extent to which the two controls were related to the study’s focal constructs across the five waves, we added equality constraints between the two sets of controls and all five waves of measurement for the three focal constructs. This provides a single unstandardized index of the overall relationship between these control factors and the three focal variables. Both percentage of EU organizational members and citizenship status predicted anticipated organizational identity change (β = .006, SE = .001, p < .001 and β = −.138, SE = .051, p = .006, respectively), supporting Hypotheses 4a and 5. This was not the case for job anxiety as EU organizational members percentage did not significantly predict job anxiety (β = 0.002, SE = .001, p = .223). However, citizenship status was a (negative) significant predictor of job anxiety states (β = −.176, SE = .058, p = .002), supporting Hypothesis 4b. Percentage of EU organizational members did not predict affective commitment significantly (β = −.001, SE =.001, p=.270) and citizenship status showed a positive relationship but not did reach the 0.05 cut-off for significance (β = .108, SE = .057, p = .057), thus, Hypothesis 4c is not supported.Footnote2

Discussion

This study makes a novel contribution by showing that the external context of macro-level uncertainty challenges the enduring and stable nature of employees’ sense of organizational identity, with consequences for job anxiety affective states and attachment to the organization. During an 18-month period marked by socio-political turmoil following the Brexit referendum, employees’ (within person) increase in anticipated organizational identity change predicted a rise in subsequent job anxiety; this rise was then followed by a reduction in affective commitment across subsequent waves. The study presents unique and consistent evidence that where employees perceive that their organization’s identity is likely to change, this can have important implications for employees’ affective well-being and the employee–organization relationship.

Identity continuity is important for health, thus when continuity is challenged this will have a negative impact on an individual’s health (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985). Our findings demonstrate that when organizational identity continuity is threatened during dynamic macro-level socio-political events, it can translate into negative consequences for employees’ affective well-being (specifically heightened job anxiety) and, in turn, employees’ attitudes to work (specifically lowered affective commitment). This is consistent with the suggestion that organizational continuity “connotes a bedrock” quality or a solid foundation (facilitating the employee-organizational linkage) which are considered particularly important for individuals who seek “situated moorings” (B. Ashforth & Mael, Citation1996; B. Ashforth et al., Citation2008) in times of turbulence. Given the known importance of affective organizational commitment as being a core employee outcome linked to a range of other important attitudes and behaviours (Mathieu & Zajac, Citation1990; Meyer et al., Citation2002), these findings have important implications for organizations operating in turbulent environments.

One of the key unique contributions of the current study is the suggestion that employees will suffer, perhaps largely unanticipated negative consequences of the broader socio-political/economic uncertainty, beyond the most likely tangible expected fears over job loss and downsizing. The negative impact that such an event will have on employees is likely to include higher levels of negative affective states such as job anxiety and potentially disrupted levels of affective commitment, which will have profound implications at the collective organizational level.

Cross-lagged effects of anticipated organizational identity change and job anxiety

A key finding of this study is that anticipated organizational identity change fluctuations are followed by (and potentially cause) job anxiety states and negative work outcomes. This follows the theoretical propositions set out in our hypotheses, drawing from arguments made by organizational identity theories (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985) and social identity theory perspectives (Haslam et al., Citation2003) who argue that having identity continuity challenged can have profound effects on employees. As we suggest however, the external context of pre-Brexit uncertainty as an event, will foster anticipation of organizational identity change which can be considered a stressor which triggers a negative affective state of job anxiety. This accords with a core proposed sequence with Affective Events Theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996), which suggests that work environment features will influence work events which can lead to affective employee responses. Our study therefore provides empirical support for the sequencing of core propositions of AET.

The findings of our study are also consistent with aspects of COR theory (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018) as ongoing experiences of job anxiety as a response to an ongoing threat to job continuity as a personal resource will be a drain on employees’ personal resources. Here, this manifests a reduced tendency (and ability) for employees to affectively commit to their employer. It is worth noting that the RICLPM results support this proposition as does the additional supplemental latent growth modelling results. Notably, the Latent Growth Modelling shows that those employees who demonstrate a growth (over 18 months) in anticipated organizational identification change, translate into a growth in job anxiety which predicts a decline in affective organizational commitment. This supports the idea that ongoing anticipation of organizational identity change, here considered a potential threat to identity continuity as a resource, fosters ongoing job anxiety states which (as an indicator of resource depletion) will hinder employees’ likelihood and ability to expend resources to affectively commit to their employing organization.

As discussed in detail by Sonnentag (Citation2015) with reference to the dynamics of well-being states in the workplace, specific directional relationships are not always straight forward to identify with well-being effects. The anticipated organizational identity change onto higher job anxiety cross-lagged relationship identified in the study is stronger than the crossed-lagged relationship between the higher job anxiety states and organizational identity change. However, in our study there is evidence of some reciprocity between the two constructs, suggesting that employees experiencing higher job anxiety states may go on to anticipate subsequent change in their organization’s identity than those without heightened anxiety. This raises interesting questions around the degree to which employees will judge or anticipate organizational identity change in circumstances where they are experiencing heightened levels of job anxiety normally. Ultimately, we need to recognize the potential reciprocal relationship between job anxiety states and anticipated organizational identity change, even though this does not produce a significant indirect cross-lagged relationship flow in the current study. Such a finding is itself interesting, given the implications it has for organizational identity theory. It also highlights the need for managers to consider the importance of devising effective strategies for improving workplace well-being more generally. Of course, in raising such an issue we do need to recognize that a collective sense of well-being in an organization, in particular negative affective states of job anxiety, is likely to be influenced by the socio-economic context that the organization faces. It is also likely to be shaped by individual circumstances (such as citizenship status), as our study shows.

Correlates of the study’s focal concepts

As mentioned above, the two key control variables of UK citizenship status and percentage of EU members in the organization predicted perceived organizational identity change, job anxiety, and affective commitment at various stages of the study’s life cycle. Whilst the inclusion of these factors in the RICLPM model was not central to the hypotheses testing of the cross-lagged propositions, these factors played an important control role in the model as these two important (expected) contextual features will be very likely to influence employees’ responses to all three of the study’s focal variables throughout the study period. Thus, including them in our analyses helps us be more confident that we are factoring in important Brexit contextual features in our key cross-lagged hypothesis testing. Over and above this however, including citizenship status and % of EU origin workers in the organization in our analyses helped us identify the role that such factors played in employee responses over this macro-level uncertain period.

As mentioned, Albert and Whetten (Citation1985) suggested that a key factor which could lead to potential organizational identity change is the loss of an identity sustaining element. Importantly, the workforce and employees themselves are a key organizational identity sustaining element as they make up the collective “we” of organizational identity. As a key feature of the potential threat that Brexit posed to the UK workforce is that the freedom of movement and work between the EU and UK is being challenged, where organizations have a high proportion of the work force who were of EU (non-UK) origin, the collective identity sustaining element of the “we” made up of EU origin employees would be threatened. Our study supports this idea as the proportion of EU workers in the participant’s organization is positively correlated with states of anticipated organizational identity change in the study. This relationship helps validate our argument that the Brexit related context was an important driver of anticipated organizational identity change. In addition to this, citizenship status was also a key predictor of all three of the study’s focal constructs across a number of the waves. In the context of the Brexit process we would expect this and thus again these relationships help validate some of our core assumptions.

Theoretical contribution

As discussed above, in exploring the potential impact of ongoing anticipated organizational identity change our study draws on theoretical work and research linked to organizational identity as a foundation, in particular work inspired by Albert and Whetten’s (Citation1985) organizational identity theoretical framework. However, a key strand of this literature that our study contributes to is work focusing in organizational identity change (e.g., Gioia et al., Citation2013). This literature tends to focus on identity change at the organizational level and we contribute to this literature by showing empirically how a background context of perceived anticipation in organizational level identity change can have individual level effects within the organizations that face potential identity change.

In helping to explain the individual level impact that potential organizational identity change has on employees, we draw on Affective Events Theory and Conservation of Resources theory as explanatory frameworks. In doing so we help integrate these theoretical frameworks and demonstrate that within an external context where organizational identities may be under change, individual level reactions can be explained through employees experiencing anticipation of the organizational level identity change. Furthermore, that ongoing employee anticipation of organizational identity change will be experienced as an individual identity threat and appraised as a stressor (Petriglieri, Citation2011); this personal (identity continuity) resource threat will foster a stress response (COR) and lead to a negative affective response (AET) of job anxiety (Warr, Citation1990). Employees’ ongoing experiences of potential identity threat and subsequent ongoing negative affective job anxiety experiences will subsequently lead to identity regulation response (Petriglieri, Citation2011) and manifest in a reduction of employees’ affective commitment to the organization (see ). Our study therefore makes a unique integrative contribution to the literature by helping provide evidence for a theoretically reasoned sequence of responses that accords with Organizational Identity theory, Affective Events Theory and Conservation of Resources theory. In addition, Weiss and Cropanzano (Citation1996) suggest that AET explains how the work context can have a distal impact on individual work attitudes through an affective mediation process of employee reactions to proximal work events. Our study contributes to AET as we show how an external context of (Brexit related) uncertainty can have a distal impact on employee attitudes towards their organization by triggering perceptions of anticipated organizational identity change. This perception of change as a proximal work event then fosters job anxiety states, subsequently impacting employees’ affective commitment. Thus, we demonstrate how the distal external organizational context can impact employee attitudes through triggering proximal drivers of affective reactions and through a process of affective mediation.

Finally, in including a temporal aspect to the current study and testing the temporal sequencing of key relationships between employees’ affective responses to work events and subsequent work attitudes, we provide some evidence that there may be feedback loops and potential reciprocal relationships between affective reactions (over time) and employee perceptions of the work events. Whilst AET does incorporate mood and affect cycles that may unfold over time, a key assumption of AET involves the idea that affect will follow the experience of work event. Our findings support this; however, we also show evidence that employee perceptions of work events (anticipated organizational identity change) may be subsequently influenced by affective responses (job anxiety). This finding enables us to highlight that the temporal sequences proposed in AETin particular, that the affect and work event sequence may include an added level of dynamic complexity.

Limitations

Despite the strengths and contributions of this study, as with any other study, we acknowledge there may be some potential limitations of the methodology used. A limitation that is also worth mentioning is the question of whether the diverse sample of employees recruited for our study warrants generalizability from the findings. The use of such populations in psychological research has been discussed in a number of recent articles (e.g., Porter et al., Citation2019), that recognize both problems and potential benefits. Evidence suggests that the response patterns of such samples fall within credibility intervals from conventionally sourced data (Walter et al., Citation2019). Importantly from the perspective of our study, because we were able to obtain a considerable variety of employees from all around the UK in hundreds of different job types, diversity in our sample can also be seen as a strength of the current study. Future research could however explore the degree to which employees vary in their responses depending upon the job or sector they may occupy.

In addition, we should also highlight that the operation of our measure of anticipated organizational identity change mixes aspects of before and after change. Scholars have pointed out that measuring aspects of a before and after change can be more fruitful if researchers separate features of the changes before and after an event, and response surface methodology is often recommended in this regard (J. R. Edwards, Citation1994). Unfortunately, the operationalization of our change measure does not allow us to disentangle the effects of the components on which the change is based, however future research would benefit from additional nuance that enables more elucidation of the features of the change. It is also worth noting that our study utilizes Brexit as an external background context variable and we make an assumptions that the temporal changes that we find in the sample are linked to the context of Brexit uncertainty. Whilst our core independent variable of anticipated organizational identity change makes specific reference to Brexit and we find significant relationships with this measure and the study’s other variables, we accept that other factors will be influencing perturbations in job anxiety states and organizational commitment through the five waves. However, we are confident in our interpretations given the consistent relationships that we find between our focal variables and, in addition, our control variables of citizenship status and proportion of the workforce made up or EU citizens. Whilst Brexit is a context variable of the study, the combination of the prominence of media discussion of Brexit (on a daily basis) during the time of the study and the advertisement of the study as being about Brexit in the workplace would have meant that this external context was salient to the participants.

We also acknowledge that the measure of change that we use in our study neither incorporates any information about whether the change is good or bad nor any information about whether the respondents are supportive of Brexit (which is likely to be related to their evaluations of change). Whilst we do not have a measure indicating whether the respondents are supportive or opposed to Brexit, we did measure perceptions of whether Brexit is likely to be bad for their organization in each wave. To ensure that the results of the RICLPM were not confounded by an evaluative perception of the change we included this measure into an additional RICLPM to see whether the results of the main study changed. Even with incorporating this additional measure into the analyses we found the same pattern of results as we report in the main study. Thus, we can be confident that the results we find are not confounded by any evaluative judgement of the anticipated change. This additional analysis is included in the online supplemental material.

Finally, we recognize that the current study is firmly embedded in the external context of national level socio-economic uncertainty following on from the Brexit referendum in the UK. This is obviously a unique context that would have particular salience to the geographical region of the UK (and arguably the rest of Europe). Readers would do well to reflect on how generalizable the findings of the current study are beyond such a context. Despite this point, the general theoretical idea that an external context can place change pressure on organizational identities and employees in these organizations will experience or display individual level responses, is likely to be found in contexts beyond Brexit. Other example contexts may include the introduction of national level legislation or institutional level changes that place organizations under change pressure, also where organizations across certain industries go through ongoing periods of change that threaten the continuity of organizational identity (e.g., organizations that undertake a series of acquisitions). Thus, in future research, the current theoretical model could be tested in other contexts where organizational identity continuity is under change pressure.

Conclusion

The current study highlights the importance of continuity to employees’ organizational identity moorings, and that a potential change or threat of change to the identity of employees’ organizations will have profound negative effects on their employees’ affective well-being, with subsequent consequences for organizations as well. We demonstrate the implications that follow when employees experience anticipated organizational identity change and show how the external context can profoundly impact employees’ work-related experiences. The study is unique in showing how a turbulent macro-level environment can have an impact on employees’ perceptions of their organization’s identity. We provide an explanatory framework that integrates key tenets of both Conservation of Resources theory and Affective Events Theory and helps provide insight into the field in helping explain how a tumultuous organizational context can impact employees by unsettling perceptions of the enduring nature of organizational identities. We have also shown how a context of macro socio-political/socio-economic turmoil (in this case Brexit uncertainty) can affect micro aspects of organizational life and go on to impact employee affective well-being states and levels of affective commitment; thus, the macro-organizational contextual environment can have a fundamental impact in the essence of an organization’s being.

EJWOP RICLPM Online supplemental material Third Revision .docx

Download MS Word (76.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2024.2374050.

Notes

1. As additional supplemental analyses, we also conduct Latent Growth Modelling (McArdle, Citation2009) with the study’s 3 focal constructs to explore whether individual overall growth or decline over five waves amongst our focal variables are associated as expected. With the LGM we use the composite variables as our observed measures at each wave, we model the intercepts (initial levels) for each of the three focal measures and also model growth (or decline) slopes (in this case linear); this allows the analyses of various features of growth (including whether individual growth slopes on one variable predict growth slopes on another) over five waves. Given that the study’s hypotheses 1 and 2 set the expectation that anticipated organizational identity change would predict job anxiety states and these would predict affective organizational commitment, we set a model that tests whether growth in the anticipated change in organizational identity (over 5 waves) predicts a growth (or decline) in job anxiety states; we also set growth in these two variables to predict growth in affective organizational commitment. As we hypothesize (with the RICLPM) mediation (of anticipated change in organizational identity through job anxiety states onto affective organizational commitment), we also test for this mediation (of growth relationships) with the LGM.