ABSTRACT

The Swedish regional elections of 2018 show a consistently high electoral turnout in all regions, and large vote-share variations for different parties across regions. There are not much second order election effects, but at the same time, the nationalization effects are less than could have been expected due to the vertical and horizontal simultaneous elections. In spite of concurrent elections, ticket splitting in Sweden has increased over time: about 30% of Swedish voters vote for different parties at different political levels. The voting pattern does not fit with typical expectations of voting-behaviour following dissatisfaction with the national government. Especially the electoral success of regional healthcare parties in some regions clearly indicate genuinely separate choice processes, more in line with a multi-level understanding of a political system with clear distribution of competences, as healthcare remain the most important task of the regions.

Introduction

Despite being a unitary country, with regions usually considered weak in terms of regional authority (Hegewald et al. Citation2018), Swedish regional elections are surprisingly interesting. One example, which will be discussed in more detail below, is that some regions have strong regional healthcare parties that mobilize voters on healthcare issues. The Swedish regions are responsible for healthcare; it is their main task, and our analyses show that most voters are well informed about this. Another example is the increasing split ticket voting across domestic tiers, despite the vertical and horizontal simultaneous elections. Almost one out of three voters chose to vote for a different party in the subnational elections compared to the national. Our findings indicate that a wider set of theoretical perspectives, beyond the second-order election logic, is needed to understand regional elections in Sweden.

Although not developed in any detail, this election report and the analytical discussion of the results, will address the most commonly used theoretical perspectives used in regional election research (Schakel and Romanova Citation2018). That is, the second order election theory (Reif and Schmitt Citation1980), nationalization of the vote (Schakel Citation2013), and two different kinds of regional election specific aspects: (a) the relevance of the institutional setting and regional responsibilities that voters may evaluate; and (b) regional specific preferences, e.g. regional identity. We argue that the results of the Swedish regional elections help to nuance the understanding of regional elections as the second order effects are limited, as are the examples of nationalization of the vote. Rather, mainly and most interestingly, the Swedish party system seem to be functioning as a multilevel electoral system. Among voters, there is an awareness of the regional specific political responsibility and increased ticket splitting between national and subnational elections.

The 2018 Swedish elections took place Sunday 9 September. Apart from the elections to the European Parliament, all Swedish elections take place with vertical and horizontal simultaneity, every fourth year, the second Sunday in September. Elections to all tiers are proportional and there is no compulsory voting. The vertical and horizontal simultaneity makes the theoretical expectations of regional elections in Sweden somewhat special (Schakel and Romanova Citation2018). The 2018 overall turnout was high, on average 83.75% for the regional level (an increase with almost one and a half percentage point compared to 2014) and 87.18% in the simultaneous national election (Swedish Election Authority Citation2018).

At the national level, the results of the 2018 election was a hung parliament, i.e. neither the red-green parties nor the centre-right alliance parties were able to secure a majority. Hence, the government formation process was unusually long, with several different government alternatives being rejected by the parliament in a record breaking 130 days long process. After months of negotiations, the Social Democratic party and the Green Party reached an agreement with the Centre and Liberal parties, referred to as ‘the January Agreement’. On 18 January 2019, Stefan Löfven (S) was then re-elected as prime minister, forming a red-green minority government, with indirect support from the Centre and Liberal parties. As will be shown below, the regional election outcome varied a lot across the regions.

We will proceed with a section on the current and historical development of the Swedish regions and their political organization and responsibility. This will be followed by a presentation and discussion of the election results regarding turnout and vote shares for different parties at the regional elections and seats in the regional assemblies. We will continue with an outlook on ticket splitting and knowledge of regional political competence, before turning to the conclusions.

Swedish regions

Historically, the regional political level in Sweden has been a county (landsting), and its assembly a county council (landstingsfullmäktige). The county councils were established in 1862. However, following a Swedish parliament decision, as of 1 January 2019, a county is now to be called a region, and the assemblies are thus now called regionfullmäktige. The regionfullmäktige, just like their predecessors, are policy-making assemblies directly elected by the residents of the region. They are financed via regional income tax and their main task has been, and still is, healthcare.

The change from counties to regions marks the culmination of a two-decade long process of regional reform in Sweden. It started with an experimental reform in 1999, when the merger of two previous county councils in the South formed the new Region Skåne, with Malmö as its main centre, and the merger of three previous county councils in the West formed the Västra Götaland region, with Gothenburg (Göteborg) as its main centre. In addition to territorial enlargement, this reform also included devolution of additional competence, such as the responsibility for physical planning, culture, environment, infrastructure and other regional development issues from the state agencies (the county administrative boards, län) to the regions (Stegman McCallion Citation2008). In 2010, this reform became permanent, and has been gradually expanded to include devolution of regional development issues to the assemblies of Gotland and Halland, as well as other forms of regional and municipal cooperation (Berg and Oscarsson Citation2013). However, since 1 January 2019, all county councils have become regions, including the added devolved responsibility of the regional development issues (SALAR Citation2019). Moreover, the Baltic Sea island of Gotland is also called a region since 1 January 2019. The island constitutes its own municipality, but it is also responsible for the typical regional tasks, especially healthcare. Another special regional governing unit is the Sami parliament, though not included in this analysis due to its different function.Footnote1

Despite the devolution of more competences to the regional level during the last two decades, healthcare remain the largest, most important (and most costly) part of the regional responsibilities. The 2019 regional reform decision reduces the previous asymmetry among the Swedish regions, and increases the regional competence in some regions. However, the regional authority in Sweden can still be considered constitutionally weak in a European comparison (Dandoy and Schakel Citation2013), although the fiscal power is strong. Swedish income tax varies around 32%, of which the county councils are responsible to directly collect slightly over 10% (and the municipalities the rest). Only high-income earners pay additional state income tax. This provides unusual fiscal power to the sub-state levels, although there are some limitations regarding how much the tax levels can fluctuate. It also means that the outcome of local and regional elections matter; the municipalities and the regions decide and collect most of the income tax and they are the policy-makers and providers of welfare. The regions can for example decide to close or open hospitals, or to reduce or increase healthcare service, as it is a devolved competence.

Politically, all the parties represented in the Swedish parliament (see ) are represented in all regional assemblies. The political parties can briefly be described in the following way. The Left Party (Vänsterpartiet) is a socialist party, focusing on welfare state issues. The formally named Social Democratic Workers’ Party (Sveriges socialdemokratiska arbetarparti), usually referred to as the Social democratic party (Socialdemokraterna) is a social democratic party, historically enormously influential on Swedish politics and the evolution of the Swedish welfare state. The Green Party (Miljöpartiet) is much younger, founded 1981 and focuses on environmental and social sustainability issues. There are two liberal parties in Sweden: The Centre Party (Centerpartiet) promotes job creation and lower taxes, as well as environmental and rural issues. The Liberal party (Liberalerna) started as the People’s party (Folkpartiet) in 1934, but changed its name in 2015. The party emphasizes liberal values such as an open society and liberal economic policies. The Christian Democratic Party (Kristdemokraterna) advocates Christian values and traditional core-family values. The Conservative party (Moderaterna) emphasizes law and order, tax cuts, and privatization of the public sector. The newest of the Swedish parties represented in the Riksdag is the Sweden Democratic Party (Sverigedemokraterna), founded in 1988. It is often described as a national-conservative, populist or right wing party, albeit the party’s own description is a social conservative party.

Table 1. List of statewide political parties in Sweden.

There are some geographical differences in party support. The northern parts of Sweden tend to vote somewhat more for the Left party and the Social democratic party. The Conservative party gets proportionally more votes in the urban areas, the Sweden democratic party is more popular in the southern parts of Sweden, and the Christian Democrats have a regional stronghold in region Jönköping (see for election results).

Since the early 2000s, the red-green coalition and the centre-right alliance, dominated Swedish national politics as two main blocs. This two-bloc formation on the national level has been challenged after the 2018 national election when the Sweden democratic party became the third largest party. At the regional level however, the two-bloc party system has been much less dominant. Instead, coalitions over the political spectrum have been common. Moreover, something quite special in Sweden is the occurrence of specific healthcare parties in some regions. They are independent parties (i.e. not part of any statewide party), they tend to remain over time in some regions, and they have election campaigns focusing almost exclusively on regional healthcare issues (see e.g. Sjukvårdspartiet Citation2018)

The executive at the regional level is called the regional board (regionstyrelse), previously the county council board, and the members are appointed after voting in the regional assembly. This is not a parliamentary system. Rather, all parties normally have representation in the regional board. However, in order to secure majorities for decisions about policy and the budget, parties negotiate after each election to create informal coalitions that in practice govern the region. Historically it has been common with attempts to seek broad consensus coalitions including parties from both left and right of the ideological spectrum. This became less common after 2010. However, after the 2018 regional elections, the number of coalitions including parties from different parts of the ideological spectrum, so called rainbow coalitions, have increased (see ). There has also been a general shift to the right of the political spectrum, with 12 regions being governed by centre-right coalitions and only one region by a left coalition (in Västerbotten). This can be compared to the national level, where the turbulent government formation process after the 2018 elections eventually led to a red-green minority government, albeit with the indirect support of the Centre Party and the Liberal Party.

Table 2. Regional leadership after regional elections in Sweden, 2010–2018.

Election results and analysis

Starting with turnout, there is not much variation across the different Swedish regions in the regional elections of 2018. As can be seen in , the average turnout for the regional elections was 83.8%. The lowest turnout was in Stockholm (82.4) and Skåne (82.6), while the highest turnout was in Halland (86.3). The comparatively high turnout in Swedish regional elections has been stable over time, around 3–5 percentage points below the national turnout the same year.Footnote2 The system with vertically simultaneous elections is an important explanation to why the regional election turnout is high. In contrast, when there has been an occasional separate regional election the turnout tends to be markedly lower. One example is the re-election in Västra Götaland 15 May 2011, when the turnout was only 44.1%, compared to the 80.6% in the ordinary regional election in September 2010 (Berg and Oscarsson Citation2012).

Table 3. Vote shares per party and turnout in regional elections in Sweden, 2018.

The variation across the different regions is more apparent when we turn to regional party choice. We can see much variation across the regions in vote shares for the statewide parties. The vote share for the Sweden Democrates (SD) is for example much higher in the southernmost regions of Blekinge (20.6) and Skåne (19.7), than in the northernmost regions of Norrbotten (6.0) and Västerbotten (6.7). For the Social democrat party (S) it is more of a rural-urban pattern, as its vote share is the lowest in the Stockholm region (26.2) and around 35% in several regions both north and south (without any of the largest cities). The Conservative Moderate party’s (M) vote share is lowest in Norrbotten (8.3) and around 22% in many of the southern regions plus Region Stockholm. Some parties have regional strongholds, e.g. Jämtland for the Centre (C) party (20.4), Jönköping for the Christian Democratic (KD) party (12.7), Västerbotten for the Left (V) party (13.5) and Stockholm for the Green (MP) party (5.6). This latter geographical variation in strongholds for the statewide parties is partly in line with the variation in vote share at the national level. However, the variation is too large only to reflect a nationalization of the regional vote.

The fact that it is not only a question of nationalization of the vote becomes more apparent when we look at the column for ‘other’ parties, where there is a large variation across the regions. It is striking how 35.2% in Norrbotten, 18.7% in Södermanland and 10.1% in Jönköping chose to vote for a non-statewide party. In these regions there is a successful regional healthcare party attracting most of these ‘other’ votes. In fact, as can be seen in , the regional healthcare parties dominate the category of ‘other’ parties gaining seats in the regional assemblies.

Table 4. Seats per party in the regional assemblies, regional executives and chairs, Sweden, 2018.

This is especially noticeable in several of the more rural and sparsely populated regions in the northern part of the country, where issues concerning closing down of hospitals or parts of the healthcare services have been contested and politicized. In Region Norrbotten for example, there were massive protests against cutbacks and proposals to reduce the intensive care capacity in some of the existing hospitals. The health care party has 27 of 71 seats in total, also holding the position of the chair of the regional board. In Region Västernorrland, the issue of closing down maternity wards lead to massive protests as pregnant women would have to travel up to 200 km to give birth. In most of these regions, healthcare parties are not new, albeit their electoral success may have varied over time. In Region Jönköping however, the southernmost of the regions with healthcare parties in the regionfullmäktige 2018, the party Bevara Akutsjukhusen (Save the Emergency hospitals) was a new party, started by hospital staff at three of the region’s hospitals, who were particularly worried about the future for two of the emergency hospitals in the region (SVT Citation2018).

The only exception to the pattern of regional healthcare parties being the typical ‘other’ parties can be found in Västra Götaland, where the previously existing healthcare party lost its seats in the 2018 election. Instead, another new party, the Democrats (D), attracted 3.44% of the votes, securing five of the 149 seats. The Democrats was a very successful party at the local level in Gothenburg in the 2018 election (16.95%), mainly due to the party’s campaigning to stop a very unpopular infrastructure investment, a train tunnel under Gothenburg (Demokraterna Citation2018, 30). This could thus be seen as a potential ‘spill-over’ from a local election, mainly based on dissatisfaction and issue voting at the local level, although the party also promoted a more efficient organization of the health care sector (Demokraterna Citation2018, 17).

The long-term trend is decreasing congruence of the regional and national vote in Sweden. In the 1970s and 1980s the difference between the aggregated regional and national voting in a region was minimal, one or two%. Since the 1990s, there has been more variation, usually between five and ten percent, reflecting the increased supply of more parties in general, and the emergence of regional healthcare parties in particular. As the 2018 results indicate, this is not a typical second order phenomenon as the elections take place at the same time, the turnout is high, and the voting pattern does not fit with typical expectations of voting-behaviour following dissatisfaction with the national government. It is however also not a typical pattern of nationalization of the vote, as we see large regional variations in vote shares across different parties and regions, and increasing differences in the regional and the national vote. Especially the electoral success of the regional healthcare parties clearly indicate a type of voting behaviour, consistent with a multi-level understanding of a political system with clear distribution of competences, as healthcare remain the most important task of the regions.

From a theoretical perspective, these results thus indicate the existence of a form of regionalized vote rather than a typical second order effect. Comparing it to the two different versions of a regionalized vote (Schakel and Romanova Citation2018), this is not about regional identity and self-governing. Rather, regional parties emerge and expand the supply of alternatives because they mainly compete on issues of relevance to this particular political tier, as healthcare remains the most important responsibility for the regions to handle. The healthcare parties focus predominantly on healthcare issues in their election campaigning (see e.g. Sjukvårdspartiet Citation2018). Although they may have started from a discontent with how the regional branch of the statewide parties have handled healthcare policy in the region, it is not about dissatisfaction with national politics but regional. Once formed, the healthcare parties also tend to be relatively successful in regaining seats in concurrent regional elections in some regions.

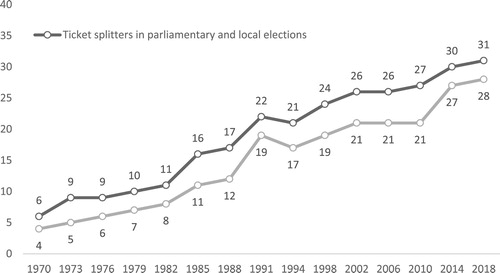

Another indication of a regionalized vote in Sweden is the long-term trend of increased ticked splitting among Swedes since 1970 (see ). In 1970, only a few percentages of Swedes would vote for different parties in the vertically and horizontally simultaneous elections. This has however increased over time, and in 2018, around 30% of Swedish voters chose to vote for different parties in the national and the regional and local elections.

Figure 1. Ticket splitting in Sweden 1970–2018. Source: The Swedish National Election Study 1970–2018. Comments: The share of ticket splitters is calculated among those who have answered which party they voted for in the elections at both compared levels (and controlled against official records of turnout).

In the Swedish National Election study 2018 (SNES Citation2018), voters were asked about their reasons behind their party choice, for both the national and the local party. The response options were set, allowing for comparison of the reasons. For each response alternative, the respondents could answer whether it was one of the most important reasons, rather important reasons, not very important or not at all important. The ticket splitters (around 900 respondents in the survey) emphasize the following categories as one of their most important: the party’s politics (42%), the party’s programme for the future (41%), and – to a larger degree than for the national elections – the importance of individual candidates (26%). Taken together, this can be seen as an indication of at least some locally/regionally aware voters. However, still only a minority (about 30%) of the voters split their tickets across different political tiers. Moreover, we know from other studies that especially the regional politicians in Sweden tend to be unknown to most of the electorate (Holmberg Citation2013).

On the other hand, the most important issue for party choice mentioned in the 2018 election study (SNES Citation2018), was welfare/healthcare (which 42% of the respondents mentioned as one of their three most important issues). Interestingly, the same study also asked respondents about which political level was responsible for healthcare (as well as some other political issues). The correct answer is the regional level. This knowledge seem to be rather high in Sweden as 79% of all respondents indicated the correct answer (see ).

Table 5. Knowledge about which level is responsible for healthcare in Sweden, 2018.

Furthermore, the propensity to provide a correct answer to this question was only somewhat higher among those who chose to split their ticket between the national and the regional elections (85 vs 82%; p = .002). In regions where a regional healthcare party gained seats in the 2018 election, there is also a slightly higher share of respondents (81 vs 79%) that are able to answer the question correctly (p = .042).

The regional healthcare parties are independent parties with different backgrounds and ideological appeal. Hence, it is not surprising that we find only limited specific characteristics of voters for these parties. In the Swedish National SOM study 2018, 11% of the respondents voted for a healthcare party, in the seven regions where healthcare parties gained seats in the regional assembly (N = 1 749). The differences are small, but it is somewhat more likely to find healthcare party voters among respondents who have rather or very little trust in politicians (16%) compared to those with very or rather high trust (8%). It is also more likely among those who voted for the Liberal (20%) or Christian democratic (18%) parties in the national election. Regarding gender, age and education, the differences are not significant, albeit pointing towards somewhat more common among women than men, middle aged rather than young, and not those with lowest education. The healthcare party voters are interesting and should be analyzed in more detail in the future.

Conclusion

The Swedish regional elections of 2018 show a consistently high electoral turnout in all regions, and large vote-share variations for different parties across regions. There are not much second order election effects, but at the same time, the nationalization effects are less than could have been expected due to the vertical and horizontal simultaneous elections.

More interestingly, there seem to exist a regional election specific voting behaviour in some regions. One indication of this is that ticket splitting has increased over time; about 30% of Swedish voters chose different parties at different political levels. While there is also a large variation in party vote shares across the Swedish regions for the statewide parties, more importantly there are specific regional parties gaining high vote shares in some regions.

Voting for these regional parties is however not related to issues of regional identity or demands for increased regional self-governance, which is more commonly found in historic regions such as Catalonia or Scotland. Rather, in the Swedish case, it is connected to the multi-level institutional setting, where the Swedish regions have specific political responsibilities, mainly healthcare. Healthcare is one of the most important issues for Swedish voters, not least in the 2018 election. Regional healthcare parties attract many votes in some regions, especially where proposals of shutting down hospitals or reducing access to healthcare have been highly politicized issues. We have also shown that voters in these regions, as well as voters who chose to split their ticket across national and regional political levels, are more knowledgeable about the regions responsibility of healthcare. It seems clear that at least some voters do evaluate the decisions taken, or the future programme of the regional parties.

Since the regions are responsible for healthcare, and this knowledge is widespread, this form of regional specific voting behaviour in some regions should not be seen as a protest directed towards the national government, but rather towards the parties dominating the regional executive and the regional assembly. Especially the electoral success of the regional healthcare parties clearly indicate a different kind of voting behaviour, more in line with a multi-level understanding of a political system with clear distribution of competences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The Sami parliament was established in 1993 as a publicly elected body and a state authority. Its role is consultative rather than self-governing, although its task is to achieve a living Sami culture. There are 31 representatives, elected every four years by Samis who are entitled to vote. They meet three times a year in the Sami parliament, which operations are controlled by the Swedish parliament and the government (Sametinget Citation2020).

2 It should be noted that the electorates are not identical, as regional and local elections are open to non-Swedish citizens who have been living in Sweden at least three years prior to the election. Turnout among non-Swedish citizens tend to be lower than for Swedish citizens, see Bevelander (Citation2015, 61–80).

References

- Berg, Linda, and Henrik Oscarsson, eds. 2012. Omstritt Omval. Göteborg: SOM-institutet, Göteborgs universitet.

- Berg, Linda, and Henrik Oscarsson. 2013. “Sweden: from Mid-Term County Council Elections to Concurrent Elections.” In Regional and National Elections in Western Europe. Territoriality of the Vote in Thirteen Countries, edited by R. Dandoy and A. H. Schakel, 216–233. London: Palgrave McMillan.

- Bevelander, Pieter. 2015. “Voting Participation of Immigrants in Swden - A Cohort Analysis of the 2002, 2006 and 2010 Elections.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 16: 61–80. doi: 10.1007/s12134-014-0332-x

- Dandoy, Regis, and Arjan H. Schakel, eds. 2013. Regional and National Elections in Western Europe. Territoriality of the Vote in Thirteen Countries. Basingstoke, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Demokraterna. 2018. att göra lista för Göteborg och sjukvården 2018-2020 [To-do-list for Gothenburg and the health care 2018-2020]. Party programme. https://demokraterna.se/var-politik/.

- Hegewald, Sven, Schakel, Arjan, Danailova, Aleksandra & Gein, Iana (2018) Final Report on Updating the Regional Authority Index (RAI) for Forty-Five Countries (2010-2016). Brussels: Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy (European Commission).

- Holmberg, Sören. 2013. “Politikerkännedom.” In En region för alla? Medborgare, människor och medier i Västsverige, edited by A. Bergström and J. Ohlsson, 87–93. Göteborg, Göteborgs universitet: SOM-institutet.

- Reif, Karlheinz, and Hermann Schmitt. 1980. “Nine Second-Order National Elections - A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results.” European Journal of Political Research 8: 3–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

- SALAR. 2019. Swedish Association of Local and Regional Authorities. https://skl.se/tjanster/kommunerochregioner.431.html, accessed 28 October 2019.

- Sametinget. 2020. The Sami Parliament. Kiruna: Sametinget/Sámediggi. https://www.sametinget.se/english.

- Schakel, Arjan H. 2013. “Nationalisation of Multilevel Party Systems: A Conceptual and Empirical Analysis.” European Journal of Political Research 52 (2): 212–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02067.x

- Schakel, Arjan H., and Valentyna Romanova. 2018. “Towards a Scholarship on Regional Elections.” Regional & Federal Studies 28 (3): 233–252. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2018.1473857

- Sjukvårdspartiet. 2018. Vi sätter vården främst! [We Make Healthcare the Priority!]. Party Programme 2018-2020. www.sjukvardspartiet.nu/media/1135/valet-2018-sjukvaardspartiet.pdf.

- SNES. 2018. Swedish National Election study 2018. https://valforskning.pol.gu.se/english.

- Stegman McCallion, Malin. 2008. “Tidying up? ‘EU’ropean Regionalization and the Swedish ‘Regional Mess’.” Regional Studies 42 (4): 579–592. doi: 10.1080/00343400701543322

- SVT. 2018. “Oväntad framgång för Bevara akutsjukhusen” [Unexpected Success for Preserve the Emergency Hospitals] https://www.svt.se/nyheter/val2018/socialdemokrater-bytte-till-bevara-akutsjukhusen.

- Swedish Election Authority. 2018. Valpresentation 2018. Stockholm: Valmyndigheten. https://data.val.se/val/val2018/slutresultat/R/rike/index.html.