ABSTRACT

This article analyses the 2019 state elections in Nigeria with a focus on party system institutionalization. The analysis shows that votes shifted and that voter turnout was higher in the state elections than in the national elections two weeks earlier. This indicates that voters regard the state elections as meaningful and that they assess subnational issues. However, the analysis of the 2019 state elections also shows that democratic norms and practices are weakly institutionalized in the political parties. It is argued that the political parties contribute to making elections in Nigeria disconnected from a majority of the citizens. A focus on subnational elections shows how the political parties are structured around regional strongmen that use the parties to pursue personalistic politics based on patronage rewards. Still, Nigeria’s federal system with attractive subnational positions makes elections competitive and state politics constitute a platform for opposition parties to endure losing national elections.

Introduction

Twenty years after the military handed over power in Nigeria, the sixth round of national and state elections were held in March 2019. Gubernatorial and State Houses of Assembly elections took place two weeks after the national elections for president and National Assembly. Subnational elections receive limited attention in general, but especially so in sub-Saharan Africa (exceptions include Ayele, Citation2018; Hamalai, Egwu, and Omotola Citation2017: ch 12; Hartmann Citation2004; Lindeke and Wanzala Citation1994). There is in general increased interest in subnational politics following an international agenda emphasizing decentralization and localization of politics in emerging democracies, partly informed by a notion that subnational politics can represent the diversity of the population better than national politics (Diamond Citation1999; Hadenius Citation2003). However, this has not translated into increased attention for subnational elections. Research on elections in Nigeria has also primarily focused on national elections (e.g. Hamalai, Egwu, and Omotola Citation2017; Kew Citation2010; LeVan, Page, and Ha Citation2018; Omotola Citation2009; Suberu Citation2007), although there are exceptions when particular political dynamics in one state is in focus (e.g. Hoffmann Citation2010; LeVan Citation2018). A reason for the primacy of the national is that decentralization in many African countries is nominal, but Nigeria is arguably the African country with the most well-entrenched federal system. The state governments have capacity and resources for authoritative decision-making. In a comparative perspective, elections to the subnational state legislatures and governments in Nigeria are regional elections as the 36 states are situated between the federal government and the 774 local governments (cf. Hooghe et al. Citation2016).Footnote1

Whereas most attention is directed towards presidential and national elections, an examination of more overlooked subnational electoral dynamics can shed light on processes that shape electoral politics. This article aims to examine the relevance of state elections in semi-democratic settings with Nigeria as a case. This is done first by examining the subnational election results in detail and compare them to the results in the national elections, and second by asking how a weak party system institutionalization contributes to shaping subnational electoral politics in Nigeria. In a democratic context, the value of political parties as an institution of representation is associated with their function as a transmission belt for citizen preferences but in more competitive authoritarian systems, they can instead function as a vehicle to control power (Schedler Citation2013). A major barrier for political parties to represent citizen interests is weakly institutionalized party systems. Four dimensions of party system institutionalization that have been highlighted are (1) stability in patterns of interparty competition; (2) party roots in society; (3) legitimacy of parties and elections; and (4) party organization (Mainwaring Citation1998). Although institutionalized party systems can support democratization, it should however not be conflated with the quality of democracy. Still, a low level of institutionalization undermines electoral accountability (Mainwaring and Torcal Citation2006, 221). Furthermore, the risk of election violence increases when political parties are weak (Fjelde Citation2020). In a study of party institutionalization in Africa, Kuenzi and Lambright (Citation2001) have found it to be low in general, but also that time is a factor that works in favour of an institutionalization of parties. The countries with most institutionalized party systems were those with more than 20 years of experience in elections. This implies that 30 years after a wave of democratization transitions started in Africa, party-systems would now be more institutionalized. However, the analysis in this article shows the parties in Nigeria to have weak roots in society and fragile party organizations, which contribute to a volatile electoral context marred by violence and irregularities.

The material for the analysis consists of newspaper articles, election observer reports, official announcements and documents along with about 30 interviews with election observer organizations, individual election observers, civil servants, politicians, and civil society actors in Nigeria after the party primaries in October 2018 and after the general elections in March 2019.Footnote2 Newspaper articles were accessed through systematic searches in Factiva, a global news database covering local and international media, using keywords related to the elections along with more specific searches, for example connected to the distribution of seats in the State Houses of Assembly. The electoral management body has published election data for the state elections late and only partially. For example, the number of votes for the governorship candidates was published on their website nine months after the elections. It is not required by law to publish detailed results and the institution has been criticized for insufficient transparency (e.g. EU EOM Citation2019a). For the presidential election, the results announcements were televised and the electoral management body primarily used twitter to report results. For this article, official statements combined with media reports and election observation reports have been used to access and compile results. Interviews in October 2018 were conducted in Lagos with civil society organizations working for credible elections, with grassroots organizations and leaders, and with local politicians. Interview requests to members of the State Houses of Assembly were either turned downed or not responded to.Footnote3 Questions related to formal and informal party organization and mobilization, to links between political parties and society, and to political development more generally. Interviews in March 2019 were conducted in Abuja and in Lagos with election observation organizations and networks.Footnote4 A question of a general assessment of the elections was followed by more specific questions regarding the administration of the election as well as about contested events and what they thought contributed to these events. One specific theme of the interviews was also their views of the state elections.

It should be noted that elections in Nigeria are prolonged processes. Just hours before the national elections were about to commence on 16 February, the elections were shifted one week by the electoral management body which cited logistic difficulties as reason. This also affected the state elections. They were originally scheduled to 2 March 2019 but moved one week forward to 9 March. In some states, elections were announced as inconclusive, which means that results could not be announced because elections had been cancelled in some districts due to technical problems, violence or other irregularities. Supplementary elections, i.e. new elections in areas where they had been cancelled, were held two weeks later, on 23 March (see ). After that, election petition tribunals were set up to review the many legal challenges that were filed by losing parties, including 15 governorship elections. In January 2020, the Supreme Court overturned the announced governorship result in Imo state (Premium Times Citation2020), illustrating the unsettled character of Nigerian elections.

Table 1. Election dates 2019, national and state elections.

The article has two main sections in line with the focus of this special issue on subnational elections. This introduction is followed by an overview of the institutional context, the political parties, and an analysis of the results of the 2019 elections in Nigeria. Then follows an analysis of political party institutionalization with a special focus on party organization and the Nigerian parties’ feeble roots in society. The article ends with a concluding section that discusses the ambiguous role of elections in Nigeria. Weakly institutionalized political parties undermine democratic progress but still, the state elections provide an arena for competition between parties. Higher voter turnout and shifting party preferences among voters compared to the national elections indicate that the state elections in Nigeria have their own dynamics and are not just a reflection of national politics.

State government and state elections

Institutional context

Nigeria’s federal arrangement is simultaneously well-entrenched and contested. There is agreement over the view that federalism is suitable for governing the country with an estimated 200 million people and widespread ethnic and religious diversity. However, there is less agreement on how the federation should be organized in terms of the degree of territorial autonomy or how subnational boundaries should be demarcated. Still, the state governments have comparatively extensive powers but these are for many states in practice reduced by a dependence on centrally collected revenues (primarily from oil extraction) distributed through the federal government. A revenue distribution formula specifies 26.72% of the revenues to be transferred to the state governments and 20.6% to the local government councils (via the states).Footnote5 There is also a derivation principle which states that 13% of the natural resource revenues shall be transferred to the state of origin. This entails that some of the oil-rich states in the Niger Delta states have larger budgets than many of Africa’s smaller countries (Owolabi Citation2019). Together with extensive executive powers in a context of widespread patrimonialism, gubernatorial offices are strategically positions with tangible leverage.

The State Assemblies have the power to make laws for ‘peace, order and good government’ if the issue is not on the exclusive jurisdiction list for the National Assembly (Federal Government of Nigeria 1999, section 4, paragraph 7). They can appoint committees and establish courts, including so-called customary courts that rely on customary law (Federal Government of Nigeria 1999, section 6, paragraph 4). The state legislatures also have equivalent oversight functions as the National Assembly at a federal level. This includes hearing petitions, exercising powers of oversight over the executive, confirming appointments and state budget scrutiny, which gives the institution a role in determining government policies and programmes. The governors have executive powers parallel to that of the president at the national level, including assenting bills passed by the state legislature and appointing chairs and members of boards and governing bodies of commissions, higher education institutions, state companies, etc. Furthermore, the state governments are responsible for elections to the local government councils.

Elections take place every four years and the 2019 elections were the sixth round of elections since Nigeria’s transition from military rule in 1999. In all 36 states, there were elections to the State House of Assembly whereas gubernatorial elections were held in 29 of the states. In the seven states without gubernatorial elections, prolonged legal challenges of previous election results have caused disruptions of the election cycle. When initial results have been overturned by courts, the incoming governors’ four-year term started when they were inaugurated after the court procedures were concluded. Governors are voted for in single-member constituencies with a majority run-off system. To win a governorship election, the candidate needs a majority of the votes and 25% of the votes in at least two-thirds of the local government areas in the state (Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999, section 179). The number of local government areas ranges from nine to 44 per state but each state has three senatorial zones and informal party principles specify that there should be ‘zoning and rotation’ of positions between the senatorial zones. This means that the highest positions within the state, such as governor, deputy governor, and speaker of the house should be distributed to persons from the different zones and that the positions should rotate between the zones. This is a reflection of an agreement in national politics that there shall be zoning and rotation between the six so-called geo-political zones.Footnote6 The agreement is connected to Nigeria’s federalism largely being a result of attempts to mitigate national ethno-regional conflict.Footnote7

Apart from the 29 governors and their deputies, 991 members of the states’ Houses of Assembly were elected along with 62 Councillors in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT Abuja). Depending on the population size of the state, the state assemblies have between 24 and 40 members (see ). The seats in the State House of Assembly are voted for in a first-past-the-post system.

Table 2. Number of seats in state houses of assemblies.

The political parties

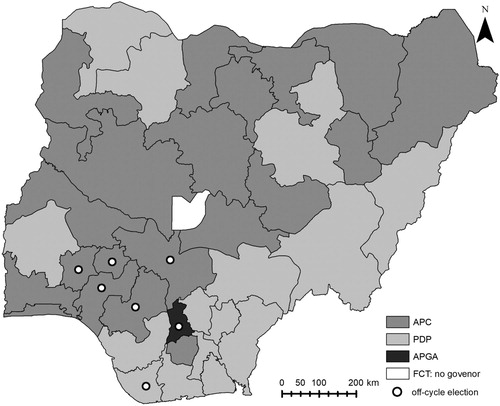

There were 91 registered parties in Nigeria ahead of the 2019 election, but national elections were a two-horse race between the two largest, state-wide, parties: Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and All Progressives Congress (APC).Footnote8 The same two parties dominated the state elections, although some of the smaller parties were represented in the state assemblies. One governor, in Anambra State that had a gubernatorial election in 2017, belongs to another party, the All Progressives’ Grand Alliance (APGA), which is a party with regionally concentrated support in the south-east.

The state-wide parties are accordingly dominating and while these are comparatively centralized, they are oftentimes dependent on regional strongmen who can be more powerful than national politicians (HRW Citation2007). Intra-party competition is fierce and party-switching is a common strategy when the prospect for securing a party candidacy is considered. Candidates seldom defect on their own but bring followers with them, which may swiftly change party strengths in a state (Guardian Citation2018a). Regulations prohibit ethnically and religiously based parties and simultaneously encourage cross-section coalitions by demanding an executive board with national representation and a spread of votes for the president with at least 25% of the votes in two-thirds of the states.

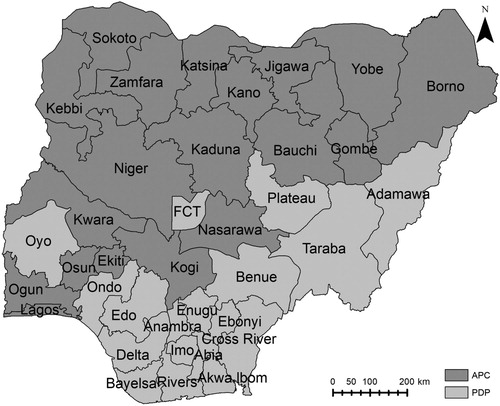

PDP was founded by well-known politicians and key retired militaries as one of three parties in 1998 during the transition from military to civil rule. It was the ruling party at the federal level for 16 years from 1999. APC was founded in February 2013 from a merger of four opposition parties with governors in the different geo-political zones as a successful attempt to challenge the PDP presidency in the 2015 election (Hamalai, Egwu, and Omotola Citation2017). Before the merger, PDP was the only nationalized party with support throughout the federation and with a majority of the state governors (see ).

Table 3. Governorship distribution after elections, 1999–2019.

Electoral administration

In elections from 1999 to 2007, the election management body, the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) had demonstrated a bias favouring the ruling party (Ibrahim and Garuba Citation2010). In 2007, the bias was of the magnitude that it undermined the legitimacy of the president who in reaction promised reforms. Ten months before the 2011 national election, INEC started a reform process when a politically independent and widely respected academic was appointed as chair of the institution. The reforms, including the introduction of biometric voter cards and electronic card readers were by INEC assessed to have contributed positively to electoral integrity (Interview Citation1). The reforms have been interpreted as making the defeat of the incumbent president in the 2015 election possible, which in itself was interpreted as a sign of deepened democratization (Owen and Usman Citation2015). However, ahead of the 2019 elections, further electoral reform was stalled by incomplete bills and repeated presidential vetoes (Pulse Citation2018).

There were 84 million registered voters for the 2019 elections, but 8.5 million did not collect their Permanent Voters Card (PVC) that is needed to vote. Still, the 25.4% increase in the number of registered voters (from 69.3 million in 2015) has been suggested to be connected to increased confidence in INEC (CDD Citation2018). However, the confidence in INEC suffered a setback when the elections were postponed with one week just hours before the polling units were about to open for the national elections. The electoral management body motivated the decision with sabotage by burning INEC offices in several states and logistical challenges that prevented delivery of sensitive material to the polling units (INEC News Citation2019). However, the decision fuelled a lot of suspicions of other factors triggering the postponement. Those with more confidence in INEC tended to think that attempted fraud had been discovered, whereas those more sceptical of INEC voiced concerns that it was an attempt to favour the incumbent (Interviews Citation2–Citation5). The logistical challenges persisted when the elections commenced, for instance reflected in that the number of registered voters had reduced with more than a million when the results were announced (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room Citation2019b). A common sentiment with regard to INEC was bewilderment, as expressed by one election observer organization: ‘Our mighty INEC chair, a professor of history, renowned, we used to love him but I don’t know now, whether our conscious has changed’ (Interview Citation6).

Election outcome

The elections for governors and state assemblies were assessed by observers to be an administrative improvement compared to the national elections two weeks before (EU EOM Citation2019b; NDI-IRI Citation2019) that suffered from poor logistics and preparedness. However, the subnational elections were also assessed to be characterized by ‘systemic failings’ (EU EOM Citation2019a) as state resources were used in the campaigns by the gubernatorial incumbents. There were instances of intimidation, attacks, and kidnappings of elections officials and voters, media was obstructed from reporting in certain areas, citizen observers were denied access to collation centres, and there was widespread vote-buying (EU EOM Citation2019b; Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room Citation2019a; YIAGA Citation2019).

Voter turnout was 34.75% in the presidential election – the lowest in Africa (ICIR Citation2019).Footnote9 However, there were large differences between the states. Lagos State recorded the lowest turnout at 16.6% while 53.0% voted in Jigawa State. Contrary to media reports and popular perceptions (e.g. Aljazeera Citation2019; CLEEN Citation2019), the voter turnout was higher in almost all state elections compared to the national elections, ranging from 14.9% in Lagos to 54.7% in Borno (see ).Footnote10

Table 4. Voter turnout for latest presidential and gubernatorial election.

In many states, the governorship elections were competitive. Out of the 29 states that held governorship elections, APC won 15 states and PDP won 14. Seventeen governors were re-elected while 12 governors won their first term. In nine of the latter 12 states, the preceding governor had served the constitutional two-term limit and in one of the remaining three, the incumbent governor did not get the party ticket at the party primaries. Accordingly, two incumbent governors were out-voted (in Adamawa and Bauchi), which is in line with an incumbent advantage in Africa that makes the incumbent likely to win in 85% of the elections (see Usman and Owen Citation2014). (See for state-level election results.)

Table 5. Results by state: presidential, governorship, and state assembly elections.

In previous state elections, there has been a bandwagon effect in that voters at the state level have shifted allegiance to the governing party at the national level in order to access patronage networks (CDD Citation2019). The National Assembly tried without success to challenge the electoral timeline by having the presidential election after the state elections (Guardian Citation2018b). This would make the governors less vulnerable to the outcome in the presidential election, as extensive executive powers in Nigeria tend to create advantages for states aligning with the president. Still, there were some indications of a diminishing bandwagon effect, even though there were politicians who switched to APC between the elections (The Nation Citation2019). After the 2019 election, the marginal for the president was higher than in 2015, but APC now had only 20 governors compared to 24 after the 2015 elections. The votes were more evenly distributed in many of the states. In 2015, the APC presidential candidate Muhammadu Buhari won over 75% of the votes in 11 states and Goodluck Jonathan of PDP won over 75% in 10 states. In 2019, however, Buhari won 75% or more of the votes in seven states and Atiku Abubakar of PDP won the same amount of votes in only two states (see ). Still, the pattern of APC and PDP strongholds to a large extent persisted (see and ).

In several states, voters shifted party preference in the state elections compared to the national election two weeks earlier. In Kano State, APC presidential candidate, Buhari, received 77.5% of the votes, while the APC incumbent governor managed to count less than 9000 more votes (50.23%) than the PDP challenger. In Bauchi State, the incumbent APC governor lost to the PDP challenger despite APC having 77.9% of the votes in the presidential election. In Sokoto State, the PDP candidate won with a minimal margin of 342 votes whereas the APC candidate won 56.2% of the votes in the presidential election. In Lagos State, on the other hand, the gubernatorial APC candidate won 75.7% of the votes compared to 53.3% for the presidential candidate. This, together with a higher voter turnout, indicates that voters deem the state elections as important and that they consider local issues and candidates, rather than solely translating national programmes or concerns to state politics (discussed further below).

The increased competitiveness of the elections had the effect that INEC declared six governorship elections on 9 March as inconclusive because the elections were suspended in some areas.Footnote11 The electoral law states that an election is to be declared inconclusive when ‘margin of lead between the two leading candidates is not in excess of the total number of registered voters of the Polling Unit(s) where election was cancelled or not held’ (Section 41(e) of the INEC Regulations and Guidelines, in Election Monitor Citation2019, 5). The guidelines stipulate a number of situations when an election can be cancelled or not held, for example when there is overvoting or when polling materials have not been possible to deliver. Elections can also be postponed when ‘there is reason to believe that a serious breach of the peace is likely to occur if the election is proceeded’ (Electoral Act 2010 (as amended), section 26(1)) and the primary reason for inconclusive elections was violence (Election Monitor Citation2019, 7). There was a pattern in the violence that political ‘thugs’ attacked collation centres in stronghold areas of the leading candidate, forcing the INEC officials to cancel the election in those areas (Interview Citation6).

Overall, violent incidents were recorded in 19 states with 17 people reported killed on the day of the state elections (EU EOM Citation2019b). Victims of the violence were party supporters, politicians, and security officials amongst others (Guardian Citation2019a). INEC reported fatalities, abductions and sexual assault against their officials. In Rivers State, the worst-hit state (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room Citation2019b, 38), violence escalated as state security institutions were mobilized by politicians. The incumbent PDP governor was assumingly using the police while a federal APC minister and former governor of Rivers was assumed to mobilize the military in a political tussle between the two strongmen that started before the 2015 election (Interview Citation7; cf. LeVan Citation2018). A leading domestic election observer organization stated with reference to Rivers State that:

the military and other security agencies have been used to undermine the electoral process with harassment and abuse of INEC officials and wanton destruction of lives and properties. Election observers are harassed and the environment for elections feels like a war, disenfranchising citizens who want to participate. (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room Citation2019a)

State elections and party institutionalization

Political parties are an essential aspect of democracy as they aggregate interests and translate voters’ preferences at the ballot box (McElwain and Wren Citation2009). However, it has also been observed that multi-party elections provide autocratic regimes with democratic legitimacy without substance (Ake Citation1996; Levitsky and Way Citation2010). In authoritarian and semi-democratic settings, subnational elections cannot be assumed to be free and fair (e.g. Ayele Citation2018). Typically, the party in power has electoral advantages by controlling the state and can be expected to use its power for advantages in subnational elections as well. In other words, the electoral playing field tends to be tilted to the party in power (Rakner and Van de Walle Citation2009) and public resources are politicized in a way that helps parties in power to maintain patronage networks and suppress opposition (Greene Citation2010). Political parties are in other words not necessarily connected to voter preferences and democratic competition, but can also function as platforms for personal power.

In order for the parties to represent citizens’ interests, the party-system needs to be institutionalized. Mainwaring (Citation1998, 68) defines a party-system as institutionalized when ‘actors entertain clear and stable expectations about the behaviour of other actors, and hence about the fundamental contours and rules of party competition and behaviour’. The four dimensions of party system institutionalization that he highlights are (1) stability in patterns of interparty competition; (2) party roots in society; (3) legitimacy of parties and elections; and (4) party organization (Mainwaring Citation1998). On the surface, some of the dimensions of party institutionalization appear to be fulfilled in Nigeria: it is the same parties that are the major contestants in elections, one of the major parties was formed more than 20 years ago, and the parties have offices in most parts of the country. However, a closer analysis reveals that the substance of the institutionalization is limited. Despite increased competition and enhanced electoral administration, the personalistic and contested nature of the 2019 state elections suggests that party-system institutionalization remains as one of the major challenges for Nigerian democracy after 20 years of uninterrupted experience of elections. The Nigerian case can be characterized as a version of ‘competition without institutionalization’ (Rose and Munro Citation2003 cited in Mainwaring and Torcal Citation2006, 209). In the remainder of this article, the ways in which the dimensions party roots in society and party organization transpired in the 2019 sub-national elections are analysed in detail. These two dimensions are in focus as a critical investigation of these can reveal how informal practices may contribute to undermining political parties as avenues for aggregation of interests and citizens’ representation.

Party roots in society

The dimension party roots in society has been measured as the age of the parties as a way to assess its ability to maintain support (Kuenzi and Lambright Citation2001), or as party loyalty by voters (Mainwaring and Torcal Citation2006). In these perspectives, a proliferation of parties in Nigeria can be noted – from three in 1999 to 91 in 2019, but also that PDP has survived as one of the main parties since the transition from military rule in 1999. APC, although new as a party, was formed as a merger of older ones and could as such be seen as reflecting some form of continuity. These parties are also the ones that attract the, by large, biggest vote shares (see ).

Table 6. Party seats in house of representatives and in the state houses of assembly after the 2019 elections.

However, the electoral dominance of these two parties is not based on programmatic or ideological linkages, but rather on the distribution of patronage resources and on incumbent electoral advantages (Omotola Citation2010). Interviews with local politicians indicate that their personal traits and campaigns are more important than to which party they belong (e.g. Interviews Citation8 and Citation9).Footnote12 The way the 2019 elections ensued, there are few indications that the parties try to establish themselves on an ideological or policy-based ground. The electoral reforms initiated by INEC have made the voting process less susceptible to political manipulation. However, political actors developed new ways of winning elections without having to appeal to a popular mandate. A combined strategy of vote-buying and violence was refined, according to election observer organizations (e.g. Nigerian Civil Society Situation Room Citation2019b). Unlike indications suggesting that vote-buying would diminish as voters gain experience of elections and improved access to information (Weghorst and Lindberg Citation2011), in Nigeria an experience of elections and politics appears to foster an attitude that you might just as well take the money to get something out of politics. Local leaders and civil society organizations report that vote-buying is a largely successful strategy. As expressed by an NGO director (Interview Citation11): ‘People don’t mind selling their votes. It is as it doesn’t matter anyway’. However, political candidates might also have more long-term strategies.

Far before we started the campaign, four years before then, with our money we built boreholes [wells] for the market women, bought motorcycle, Okada, for the Okada riders, bought bus for the road transport union, NURTW, giving less privileged money to buy [school] forms. So, people are seeing actually that “I think if this man is in the Assembly or anywhere we will do better. Doing things with his own money.” (Interview Citation8)

However, enhanced electoral administration has also contributed to strengthening accountability mechanisms. In some states, the voters turned against prevailing regional strongmen. In Kwara State, the senate president Bukola Saraki was voted out as senator and all his aligned politicians lost in the state elections. This indicated a possible fall of the ‘Saraki dynasty’ that has controlled Kwara politics since the Second Republic in 1979 (Luqman Citation2010). Saraki had become increasingly unpopular in the state and when his chosen gubernatorial candidate was defeated in all local governments in the state it was seen as a victory for the ‘O to ge’ (enough is enough) movement (Premium Times Citation2019c). A similar disruption of personalized political power transpired in Akwa Ibom State where the influence of the powerful senator and political broker, Godswill Akpabio, was broken. Then again, there is competing evidence as to what extent better conducted elections actually contribute to democracy (e.g. Donno Citation2013; Elklit Citation1999). Positive effects of electoral institutions are assessed to be contingent on democratic attitudes of the political elites (Elklit Citation1999, 47), and there are few signs of the Nigerian political elites embracing democratic attitudes. Instead, the majoritarian electoral system with a winner-takes-all fosters an attitude of politics as a zero-sum game. The parties are not strong enough to force compliance with democratic rules and instead they are platforms for individuals to contest elections and to build networks. In this latter regard, the parties are relevant as power blocs in the states as politicians have used the parties to stretch their networks of power. There are other factors than confidence in a party’s ability to implement policies that determine support for a candidate, including such aspects as patronage benefits. A local community leader describes it as that he ‘has to belong to their party [the party in power]’ as resources to the community would otherwise be stifled (Interview Citation12).

Still, voters make different party choices in national and state elections despite the closeness in time. State dynamics affect the congruence between state and national elections. The dissimilarity index score in above is a measure of the percentage of the electorate that voted differently in the state election compared to the nearest in time state-wide election result in the same territory (see the formula in Schakel Citation2013). Dissimilarity is high in a number of states, which indicates that subnational elections can be competitive, and that there are different dynamics in state and national elections. In some cases, subnational election dynamics are altered when a third party is able to attract a substantial number of votes, such as in Anambra, Nasarawa and Imo. In other states, such as in Kano and Lagos, the APC and the PDP national and subnational structures and candidates were viewed differently in the states.

Party organization

The other dimension of party system institutionalization analysed here is party organization. The two major parties are state-wide in that they have party branches throughout the country and have, according to the regulations, representation from all six geopolitical zones of the country in their executive committees. However, the parties are rift with internal conflict, reflected in the many struggles over party leadership at different levels and over candidate selection procedures. In several states, the party primaries held in October 2018 were marred by violence:

Before the elections, there was a lot of violence, especially in the APC primaries. We did not see that violence to the same extent within the PDP. Of course, they are not in power. Experience shows that where there is a state government election, there is going to be violence within [the incumbent] political party. APC had the possibility to win more positions, there were going to be more people wanting to grab those positions within the party. (Interview 6)

The APC could not resolve the many disputes surrounding the party primaries in 2018 internally but they had to be resolved by external actors, either by INEC or by the judiciary. In Zamfara State, in which APC won a majority of the votes (71,9%), the Supreme Court later ruled that there had been no primary elections that complied with the regulations and therefore the votes for APC were declared as ‘wasted’ and PDP won the governorship election and all but one seat in the state assembly (INEC Citation2019). The personalistic aspects of Nigerian politics underlie many of the intra-party conflicts. In Zamfara, two different factions claimed to be the legitimate party organization. Also in violence-ridden Rivers State in the south-south, the APC candidates were disqualified to participate in the election on basis of irregular primaries (The Punch Citation2019). The APC in the state had split into different factions, one headed by a former governor and then federal minister, Rotimi Amaechi, who was seen as eager to remain the party leader in the state and be able to have his loyalists in government positions (Interview Citation7). Three days before the election, he endorsed a gubernatorial candidate from another party, the African Action Congress (AAC), which few in Rivers knew about and which had not been visible during the campaign period. Supposedly, negotiations had been held before the AAC candidate was backed. The deal entailed that if the candidate would win, key appointments would be decided by Amaechi (ibid.). The events in Rivers State illustrate the strong position of informal power brokers, so-called ‘godfathers’, in Nigerian politics, which may sometimes be more powerful than the governors, or as expressed by one election observer organization: ‘There are strongmen that are stronger than our institutions’ (Interview Citation6).

Even though there is regularity in party competition and there are formal national organizations for the parties, the political parties function primarily as vehicles for ambitious individuals and the parties have not developed an independent status and value of their own. Having party ‘structures’ is a way to link the party or candidate to the voters. These structures often manifest in the form of clientelist networks that have spread in society, such as community associations, but also groups with violent capital, such as the National Union of Road Transport Workers or ethno-nationalist movements (Agbiboa Citation2018; Nolte Citation2007), and they are not connected to the party in itself. Nurturing such networks over time is, as indicated above, crucial for candidates’ campaigns to gain traction.

The primacy of personalistic politics is further corroborated by the recurring theme in interviews that respondents do not see any difference between the parties, and civil society organizations urged voters to assess the candidates rather than the parties before the elections. The ‘emptiness’ of the parties can be seen as a consequence of the formation of parties being linked to the state and state resources rather than to societal forces. The financial dependence of the parties on the state favours the party in power and provides few alternatives to counteract top-down established party structures (cf. van Bizen Citation2005). Accordingly, the parties continue to primarily be arenas for elite competition, and do not reflect different social interests and cleavages as much as they shape them (Manning Citation2005).

Conclusion

The 2019 state elections in Nigeria demonstrate the ambiguous role of elections in democratization processes. On the one hand, regular elections contribute to predictable party competition, but on the other hand, weakly institutionalized political parties undermine democratic progress. There was close competition between different candidates in a number of the federal states, but the parties and the candidates tend to refine their strategies to circumscribe democratic norms and practices. Still, the national incumbency advantage that is prevalent in competitive authoritarian states is to some extent mitigated by the resources and leverage that the gubernatorial offices bring. The federal system can also help explain why parties in Nigeria has been relatively successful in a comparative African context of surviving over time and especially the continued existence of PDP as a national party despite losing national power in 2015. Oftentimes, losing national power results in party fragmentation causing incumbent parties in Africa to be more nationalized than opposition parties, which are often regionally based (Rakner and Van de Walle Citation2009; Wahman Citation2017). Yet, the combined effect of politicized state institutions and patronage politics tend to enhance the power of incumbency also for subnational governments (Cheeseman Citation2010), which may work to the benefit of national opposition parties. The Nigerian case illustrates that having a dozen governors with capacity for mobilization and attracting local elites can provide an alternative to joining the national ruling party, which is a common strategy for politicians on the losing side that contributes to undermining opposition parties. Still, the parties function as platforms for personalistic politics that build around regional strongmen.

Whereas ongoing reforms of the electoral administration have helped create conditions for elections to be competitive, such reforms were to a large extent thwarted by undemocratic practices by the political elites who regard elections as a way to power unrelated to popular preferences (Ake Citation2000). As electoral administration has improved, politicians refined their strategies to engineer themselves into office. Practices such as ballot-box stuffing and falsified collation result sheets have been counteracted by the introduction of biometric voter cards and electronic card readers, but vote-buying and the deployment of political thugs have instead increased. This contributes to making elections in Nigeria disconnected from a majority of the citizens.

Nonetheless, the level of competition indicates that the state elections are conceived as meaningful, which is also underlined by the localized nature of the elections. This is manifested by the higher voter turnout in the state elections than in the national elections, but also by the shifting of votes in several states in the state elections compared to the national elections held two weeks before. In patronage-driven politics, the expectation is for the states to align with the presidential election outcome, but the state elections saw a number of states with diminishing votes for APC despite winning the presidency and a majority in the National Assembly. In three former APC states, PDP won the governorship elections. In two additional states, incumbent governors had switched to PDP in 2018 and they retained their seats. To an overwhelming extent, however, it is the same two parties that compete in the state elections as it is in the national elections, pointing to the relevance of being able to gain access to networks beyond the state level.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Jenniina Kotajoki, the editors of this special issue, and the reviewers for valuable comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term state election is preferred to regional election in a Nigerian context as ‘regions’ are commonly used to signify a collection of states on basis of the federal units called Regions in the 1960s (Northern, Eastern, Mid-Western, and Western). Additionally, the six geo-political zones (see below note 6) are sometimes referred to as regions.

2 Only cited interviews appear in the list of references. The full list is with the author.

3 Requests were sent via e-mail to representatives who had their address on official website. E-mails were followed up by phone call/text message when phone number was available. A limited time available for the interviews may have contributed to difficulties in gaining access.

4 Abuja and Lagos were chosen as sites for the interviews in 2019 as it is in these cities most of the organizations with national reach have their offices. The interviews in Lagos in 2018 were conducted in a context of research on the implications of the vertical ties between political parties and the electoral constituencies for electoral violence. The focus was on local leaders and local politicians as intermediaries. For that reason, there is an omission of ‘ordinary’ party members in the material. However, this is somewhat offset by the inclusion of interviews with community and grassroots organizations.

5 State governments have taken over most local government functions and resources (UCLG & OECD Citation2016).

6 North-West (Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara), North-East (Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba, Yobe), North-Central (Benue, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Niger, Plateau), South-West (Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun, Oyo), South-East (Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo), and South-South (Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Rivers, Delta, Edo).

7 At independence in 1960, Nigeria had three largely autonomous regions, however with a skewed balance which has been argued to have contributed to the civil war that started in 1967 (Horowitz Citation1993). Since 1967, several reforms have seen the federal units grow to 36 and a Federal Capital Territory, along with 774 Local Government Areas that constitute the third tier of the government. A historical conflict line has been between the north, with Hausa as dominant ethnicity, and the south of the country, with Yoruba in the south-west and Igbo in the south-east as majorities, although this tends to conceal the multi-ethnic composition of the different parts of the country (Suberu Citation2001).

8 74 political parties were de-registered in February 2020 as they did not meet the constitutional requirement of winning enough votes (Vanguard Citation2020).

9 Nigeria also has the lowest number of elected female representatives. The 2019 elections resulted in diminishing number of women filling electoral positions at both the national and the regional level. In the lower house of the National Assembly, the number of women was reduced from 22 to 13 out of 360 and now constitutes 3.6%. Fewer women ran as candidates in the state assembly elections compared to the previous election. It was 12.8% female candidates in 2019 compared to 14.4% in 2015 (EU-EOM Citation2019b) and out of 944 announced seats in the state parliaments, only 44 women won a position, which amounts to 4.6% (CDD Citation2020). There is no woman that has been elected governor and the number of female deputy governors dropped from six to four in the 2019 elections (Premium Times Citation2019a).

10 One factor raising the voter turnout was that there were less cancelled votes in the state elections and the cancelled votes are not added to turnout. There were those who saw the turnout rate as flawed: ‘[It] raises a lot of controversial arguments. Because it was more people that turned out during the presidential than during gubernatorial, but the figures are showing the opposite.’ (Interview 6).

11 In Adamawa, Bauchi, Benue, Kano, Plateau, and Sokoto.

12 However, there are also those in the smaller parties who more committed parties’ programmes (Interview Citation10).

References

- Agbiboa, D. E. 2018. “Informal Urban Governance and Predatory Politics in Africa: The Role of Motor-park Touts in Lagos.” African Affairs 117 (466): 62–82. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adx052

- Ake, C. 1996. Development and Democracy in Africa. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Ake, C. 2000. The Feasibility of Democracy in Africa. Dakar: Codesria.

- Ayele, Z. A. 2018. “EPRDF’s ‘Menu of Institutional Manipulations’ and the 2015 Regional Elections.” Regional & Federal Studies 28 (3): 275–300. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2017.1398147

- CDD (Centre for Democracy and Development). 2018. Nigeria Electoral Trends. Abuja: CDD.

- CDD (Centre for Democracy and Development). 2019. Background Paper on the 2019 Governorship and House of Assembly Elections in Nigeria. Abuja: CDD.

- CDD (Centre for Democracy and Development). 2020. How Women Fared in the 2019 Elections. Abuja: CDD.

- Cheeseman, N. 2010. “African Elections as Vehicles for Change.” Journal of Democracy 21 (4): 139–153. doi: 10.1353/jod.2010.0019

- Diamond, L. 1999. Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation. Baltimore; London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Donno, D. 2013. “Elections and Democratization in Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (3): 703–716. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12013

- Election Monitor. 2019. Why Elections are Determined Inconclusive in Nigeria: Focus on the 2019 Governorship Elections. Abuja: Election Monitor.

- Elklit, J. 1999. “Electoral Institutional Change and Democratization: You can Lead a Horse to Water, But You can't Make it Drink.” Democratization 6 (4): 28–51. doi: 10.1080/13510349908403631

- Fjelde, H. 2020. “Political Party Strength and Electoral Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 57 (1): 140–155. doi: 10.1177/0022343319885177

- Greene, K. F. 2010. “The Political Economy of Authoritarian Single-Party Dominance.” Comparative Political Studies 43 (7): 807–834. doi: 10.1177/0010414009332462

- Hadenius, A. 2003. Decentralisation and Democratic Governance. Experiences from India, Bolivia and South Africa. Stockholm: EGDI.

- Hamalai, L., S. Egwu, and J. S. Omotola. 2017. Nigeria’s 2015 General Elections: Continuity and Change in Electoral Democracy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hartmann, C. 2004. “Local Elections and Local Government in Southern Africa.” Africa Spectrum 39 (2): 223–248.

- Hoffmann, L. 2010. “Fairy Godfathers and Magical Elections: Understanding the 2003 Electoral Crisis in Anambra State, Nigeria.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 48 (2): 285–310. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X1000025X

- Hooghe, L., G. Marks, A. H. Schakel, S. C. Osterkatz, S. Niedzwiecki, and S. Shair-Rosenfield. 2016. Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Horowitz, D. L. 1993. “The Challenge of Ethnic Conflict: Democracy in Divided Societies.” Journal of Democracy 4 (4): 18–38. doi: 10.1353/jod.1993.0054

- HRW. 2007. Criminal Politics: Violence, ‘Godfathers’ and Corruption in Nigeria. Washington: Human Rights Watch.

- Ibrahim, J., and D. Garuba. 2010. A Study of the Independent National Electoral Commission of Nigeria. Dakar: Codesria.

- INEC. 2019. Press Release, May 25. https://www.vanguardngr.com/2019/05/inecs-statement-declaring-pdps-candidates-winners-of-zamfara-eections/.

- INEC News. 2019. Decision to Re-Schedule General Elections Painful But Necessary, Says INEC Chairman. February 17. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://inecnews.com/decision-to-re-schedule-general-elections-painful-but-necessary-says-inec-chairman/.

- Kew, D. 2010. “Nigerian Elections and the Neopatrimonial Paradox: In Search of the Social Contract.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 28 (4): 499–521. doi: 10.1080/02589001.2010.512744

- Kuenzi, M., and G. Lambright. 2001. “Party System Institutionalization in 30 African Countries.” Party Politics 7 (4): 437–468. doi: 10.1177/1354068801007004003

- LeVan, A. C. 2018. “Reciprocal Retaliation and Local Linkage: Federalism as an Instrument of Opposition Organizing in Nigeria.” African Affairs 117 (466): 1–20. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adx040

- LeVan, A. C., M. T. Page, and Y. Ha. 2018. “From Terrorism to Talakawa: Explaining Party Turnover in Nigeria's 2015 Elections.” Review of African Political Economy 45 (157): 432–450. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2018.1456415

- Levitsky, S., and L. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lindeke, W. A., and W. Wanzala. 1994. “Regional Elections in Namibia: Deepening Democracy and Gender Inclusion.” Africa Today 41 (3): 5–15.

- Luqman, Saka. 2010. “Agent of Destruction: Youth and the Politics of Violence in Kwara State, Nigeria.” Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 12 (8): 10–21.

- Mainwaring, S. 1998. “Party Systems in the Third Wave.” Journal of Democracy 9 (3): 67–81. doi: 10.1353/jod.1998.0049

- Mainwaring, S., and M. Torcal. 2006. “Party System Institutionalization and Party System Theory after the Third Wave of Democratization.” In Handbook of Party Politics, Vol. 11, edited by R. Katz, and W. Crotty, 204–227. London: Thousand Oak.

- Manning, C. 2005. “Assessing African Party Systems after the Third Wave.” Party Politics 11 (6): 707–727. doi: 10.1177/1354068805057606

- McElwain, K. M., and A. Wren. 2009. “Voters and Parties.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics, edited by C. Boix and S. C. Stokes, 555–581. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nolte, I. 2007. “Ethnic Vigilantes and the State: The Oodua People's Congress in South-Western Nigeria.” International Relations 21 (2): 217–235. doi: 10.1177/0047117807077005

- OECD & UCLG. 2016. Subnational Governments Around the World: Country Profile Nigeria. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-policy/profile-Nigeria.pdf.

- Ojo, J. 2018. “Party Primaries of Tears, Blood and Sorrow.” The Punch, October 10. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://punchng.com/party-primaries-of-tears-blood-and-sorrow/.

- Omotola, J. S. 2009. “‘Garrison’ Democracy in Nigeria: The 2007 General Elections and the Prospects of Democratic Consolidation.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 47 (2): 194–220. doi: 10.1080/14662040902857800

- Omotola, J. S. 2010. “Political Parties and the Quest for Political Stability in Nigeria.” Taiwan Journal of Democracy 6 (2): 125–145.

- Owen, O., and Z. Usman. 2015. “Briefing: Why Goodluck Jonathan Lost the Nigerian Presidential Election of 2015.” African Affairs 114 (456): 455–471. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adv037

- Owolabi, T. 2019. “Governor Election Counting Halted in Southern Nigeria Oil State.” Reuters, March 10. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://af.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idAFKBN1QR0QE.

- Rakner, L., and N. Van de Walle. 2009. “Democratization by Elections? Opposition Weakness in Africa.” Journal of Democracy 20 (3): 108–121. doi: 10.1353/jod.0.0096

- Rauschenbach, M., and K. Paula. 2019. “Intimidating Voters with Violence and Mobilizing them with Clientelism.” Journal of Peace Research 56 (5): 682–696. doi: 10.1177/0022343318822709

- Rose, R., and N. Munro. 2003. Elections and Parties in New European Democracies. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- Schakel, A. H. 2013. “Congruence between Regional and National Elections.” Comparative Political Studies 46 (5): 631–662. doi: 10.1177/0010414011424112

- Schedler, A. 2013. The Politics of Uncertainty: Sustaining and Subverting Electoral Authoritarianism. Oxford: OUP.

- Suberu, R. T. 2001. Federalism and Ethnic Conflict in Nigeria. Washington: United States Institute of Peace Press.

- Suberu, R. T. 2007. “Nigeria's Muddled Elections.” Journal of Democracy 18 (4): 95–110.

- Usman, Z., and O. Owen. 2014. “Incumbency and Opportunity: forecasting Nigeria’s 2015 Elections.” African Arguments, October 29. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://africanarguments.org/2014/10/29/incumbency-and-opportunity-forecasting-nigerias-2015-elections-by-zainab-usman-and-olly-owen/.

- van Bizen, I. 2005. “On the Theory and Practice of Party Formation and Adaptation in New Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 44 (1): 147–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2005.00222.x

- Wahman, M. 2017. “Nationalized Incumbents and Regional Challengers: Opposition- and Incumbent-Party Nationalization in Africa.” Party Politics 23 (3): 309–322. doi: 10.1177/1354068815596515

- Weghorst, K., and S. Lindberg. 2011. “Effective Opposition Strategies: Collective Goods or Clientelism?” Democratization 18 (5): 1193–1214. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2011.603483

Election Reports

- CLEEN. 2019. Post-Election Statement on the Conduct of Security Personnel on Election Duty during the 2019 Governorship/State Assembly Elections in Nigeria, March 10.

- EU Election Observation Mission. 2019a. Nigeria 2019: Final Report. Brussels: EUEOM.

- EU Election Observation Mission. 2019b. Second Preliminary Statement. March 11.

- IRI/NDI. 2019. Preliminary Statement of the Joint NDI/IRI International Observation Mission to Nigeria’s March 9 Gubernatorial and State House of Assembly Elections.

- Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room. 2019a. Second Interim Statement by Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room on its Observation of the Governorship, State Houses of Assembly And FCT Area Council Elections. Abuja, March 10.

- Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room. 2019b. Report of Nigeria’s 2019 General Elections. Abuja.

- YIAGA. 2019. Statement on Accreditation, Voting and Results Collation. March 10.

Newspapers

- Aljazeera. 2019. “Voter Apathy Apparent in Nigeria's Local Elections,” March 9. Accessed 18 February 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2019/03/voter-apathy-apparent-nigeria-local-elections-190309141520691.html.

- Deutsche Welle. 2019. “Violence and Fraud in Nigeria's Gubernatorial Elections,” March 27. Accessed 15 May 2019. https://allafrica.com/stories/201903280016.html?.

- The Guardian. 2018a. “Lamido Welcomes 2000 APC Defectors to Jigawa PDP,” December 13. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://guardian.ng/politics/lamido-welcomes-2000-apc-defectors-to-jigawa-pdp/.

- The Guardian. 2018b. “National Assembly can’t Re-order Election Sequence,” April 26. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://guardian.ng/politics/national-assembly-cant-re-order-election-sequence/.

- The Guardian. 2019a. “ Governorship/State Assembly Elections Record Low Turnout,” March 10. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://guardian.ng/news/governorship-state-assembly-elections-record-low-turnout/.

- The Guardian. 2019b. “1,119 Electoral Offenders are in Detention, Say Police,” March 22. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://guardian.ng/news/1119-electoral-offenders-are-in-detention-say-police/.

- ICIR. 2019. “2019 Election: Nigeria has the Lowest Rate of Voter Turnout in Africa,” March 14. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://www.icirnigeria.org/2019-election-nigeria-has-the-lowest-voter-turnout-in-africa/.

- The Nation. 2019. “Defections, Court Battles as Parties Intensify Campaigns,” March 5. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://thenationonlineng.net/defections-court-battles-as-parties-intensify-campaigns/.

- Premium Times. 2019a. “2019 Elections Worst for Nigerian Women in Nearly Two Decades, Analyses Show,” April 20. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/326243-2019-elections-worst-for-nigerian-women-in-nearly-two-decades-analyses-show.html.

- Premium Times. 2019b. “Court Nullifies All APC Primaries in Rivers, Stops Party from 2019 Elections,” January 7. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/304544-breaking-court-nullifies-all-apc-primaries-in-rivers-stops-party-from-2019-elections.html.

- Premium Times. 2019c. “‘O to Ge’: How I Originated the Campaign Slogan that Dethroned Saraki – Septuagenarian,” March 6. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/317904-o-to-ge-how-i-originated-the-campaign-slogan-that-dethroned-saraki-septuagenarian.html.

- Premium Times. 2019d. “It’s Official: INEC Declares APC’s Ganduje Winner of Kano Supplementary Guber Election,” March 24. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/322096-its-official-inec-declares-apcs-ganduje-winner-of-kano-supplementary-guber-election.html.

- Premium Times. 2020. “Why Supreme Court Sacked Ihedioha, Declared APC's Uzodinma Winner.” January 14. Accessed 15 January 2020. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/372652-why-supreme-court-sacked-ihedioha-declared-apcs-uzodinma-winner-in-imo.html.

- Pulse. 2018. “This is Why President Buhari Refused to Sign Electoral Amendment Bill for the 4th Time in 2 Years,” December 10. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://www.pulse.ng/news/local/this-is-why-president-buhari-refused-to-sign-electoral-amendment-bill-for-the-4th/vrc24jm.

- The Punch. 2018. “Violent Primaries and Abuse of Democratic Process,” October 9. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://punchng.com/violent-primaries-and-abuse-of-democratic-process/.

- The Punch. 2019. “Supreme Court Upholds Judgement Barring Rivers APC from Polls,” February 9. Accessed 13 May 2019. https://punchng.com/scourt-upholds-judgement-barring-rivers-apc-from-polls/.

- The Punch. 2020. “Supreme Court nullifies Bayelsa Governor-elect’s Election, Declares PDP Winner,” February 13. Accessed 18 February 2020. https://punchng.com/breaking-supreme-court-nullifies-bayelsa-governor-elects-election-declares-pdp-winner/.

- Vanguard. 2020. “Why INEC Deregistered 74 Political Parties,” February 6. Accessed 14 February 2020. https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/02/why-inec-deregistered-74-political-parties/.

Interviews

- Interview 1. Residential Electoral Commissioner, Lagos, 24 October 2018.

- Interview 2. Programme manager, NGO working on election observation nationally, Lagos, 11 March 2019.

- Interview 3. Director, NGO working on democracy, governance and women’s rights, Lagos, 24 October 2018.

- Interview 4. Director, NGO working on elections and security, Lagos, 13 March 2019.

- Interview 5. Member of INEC Situation Room, Lagos, 11 March 2019.

- Interview 6. Staff member, NGO with election observers, Abuja, 20 March 2019.

- Interview 7. Director, Civil Society Organization based in Rivers State, Lagos, 13 March 2019.

- Interview 8. Candidate to House of Representatives, Abuja, 4 December 2017.

- Interview 9. Candidate to State House of Assembly, Lagos, 26 October 2018.

- Interview 10. Local party branch chair, Lagos, 26 October 2018.

- Interview 11. Head of Office, NGO working on accountability, justice, and elections, 22 October 2018.

- Interview 12. Community Leader, party member, Lagos, 15 October 2018.