ABSTRACT

The international trend of state restructuring and the rise of decentralized welfare systems means a key challenge for social research is to systematically explore the breadth of factors shaping the territorialization of third sector welfare delivery at the meso level in federal and union states. We address this lacuna by synthesizing historical-institutionalism and critical realism with Salamon and Anheier’s classic framework on civic infrastructure development to produce an inductive analytical model for wider empirical testing. Its application here to the longitudinal case study data covering Wales shows it to be effective in providing a holistic understanding of the temporal and spatial processes underpinning decentralization. The wider significance of the case study lies in underlining the iterative, reciprocal relationship between governance reforms and territorialization – and showing how territorialization can originate in response to national crises and welfare demand caused by state and market failure in the delivery of public goods.

Introduction

In response to an international trend of state restructuring and devolution a burgeoning literature has sought to analyse the decentralization of the welfare state (Borghi and Van Berkel Citation2007). Existing studies have tended to examine discrete factors driving this process – such as marketization (López-Santana Citation2015), neo-liberalism (Bergh Citation2012); governance reforms (Pavolini Citation2015); political pressure from minority nationalist parties (Chaney Citation2017); and resistance to federal social programmes (Mooney and Scott Citation2012). However, a challenge for social research is to systematically identify and explore the breadth of factors that shape the territorialization of the third sector welfare delivery at the meso level in federal and union states. Here we address this lacuna through theory-building and empirical case study analysis. Our aim is to engage with the literature on welfare state decentralization with reference to voluntarism – and develop an analytical model for wider application to the empirical analysis of third sector welfare territorialization. In epistemological terms this aligns with the concept of holism (Verschuren Citation2001) and systems analysis in social science (Bailey Citation2001).

Specifically, we synthesize neo-institutionalism and critical realism with Salamon and Anheier’s (Citation1996) classic framework on civic infrastructure development. We use this to produce an inductive analytical model of contingent factors shaping the meso territorialization of third sector welfare. In the second half of the paper, using a longitudinal dataset spanning nine decades, we apply the model to a case study of Wales. In this way the current study responds to earlier calls to explore the divergent histories and geographies of voluntarism (Crowson Citation2011). Our core finding is that welfare decentralization is driven by discontinuity at critical junctures related to governance transitions (phases of devolution), national crisis (war) and political shifts (Thatcherite reforms, and the partnership rhetoric of government given expression in the devolution reforms of the 1990s).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: first, the analytical model is outlined. Following an outline of the research context and methodology, the model is then applied to the case study. In the concluding discussion we reflect on the model’s utility and wider significance as an analytical tool as evidenced by the case study analysis.

An analytical model of contingent factors shaping the meso-territorialization of third sector administration and welfare delivery in union states

Classic expositions of welfare state theory (Esping Andersen Citation1990) are often predicated upon the notion of centralized unitary states and align with ‘methodological nationalism’ or ‘the assumption that the nation/state/society is the natural social and political form of the modern world’ (Wimmer and Glick Schiller Citation2002, 301). In response, a burgeoning literature (e.g. Bergman Citation2007) points to the need to examine spatiality and scalar effects on sub-state welfare provision. Here we take-up this challenge in relation to the empirical analysis of third sector welfare territorialization in federal and union states. This has wide relevance owing to the global trend of state decentralization (Rodriguez-Pose and Gill Citation2003). In definitional terms, it should be noted that union states are characterized by

the incorporation of parts of [… their] territory at different times … reflected in an institutional infrastructure providing some degree of meso-autonomy to particular areas and asymmetric political and social rights; this may coexist with administrative standardisation over most of the territory. (Kay Citation2005, 544)

Contingent factors promoting the territorialization of the third sector welfare at the meso level in federal and union states

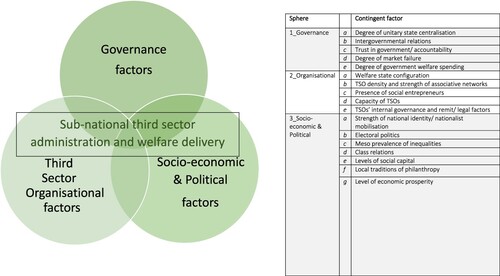

Salamon and Anheier’s (Citation1996) framework lists a raft of factors underpinning civic infrastructure development. The present analytical model develops this by engaging with literature post-dating the original framework. The factors fall into three groupings (): the governance sphere (factors 1 a. – f.), the organizational sphere (2 a. – e.) and socio-economic/ political sphere (3 a. – g.). Governance factors are concerned with the configuration of the state. They include the degree of unitary state centralization, intergovernmental relations in multi-level states, and market efficacy in the provision of public goods. Organizational factors include welfare state configuration, the density and strength of associative third sector networks, and the presence of social entrepreneurs. Lastly, socio-economic and political factors include: the strength of national identity/ nationalist mobilization at the meso level, the ‘regional’ prevalence of social inequalities, and economic prosperity. Further details of these factors and associated literatures are outlined in the latter half of this paper when they are applied to the case study data. Before this, we turn to consider social theory and the mechanism at the heart of the model: critical junctures.

Critical junctures and contingency

In explaining the relationship between the contingent factors and critical junctures in our analytical model we draw on critical realism and historical institutionalism (See Steinmo, Thelen, and Longstreth Citation1992). These conceptual strands support the model’s core thesis: that the interplay and co-presence of contingent factors at key historical moments or critical junctures helps to explain third sector welfare territorialization.

As a social scientific approach the proposed model has its grounding in contingency theory. As Walzer (Citation1990, 32) notes, norms around meaning and understanding of the social world can only be validated when there is cognizance of local, contextual phenomena. It is a view expressed in the literature of critical realism: a theoretical approach to social science that seeks to identify causal mechanisms in social processes that, in turn, enable critique of social arrangements and institutions (Sayer Citation2000). As Gerrits and Verweij (Citation2013, 172) explain: ‘reality is contingent. This means that any explanation [of social processes] is temporal in time and local in place. Since systems are nested within their systemic environments, there is mutual influence between different systems’.

Importantly, the evolutionary theory strand of historical institutionalism argues that contingent factors are not static. They should be viewed as evolving drivers of institutional change. The mere existence of contingent factors does not, in and of itself mean that territorialization of the third sector will be actualized. There is no inductive certainty involved and the straightforward co-presence of a core set of factors or preconditions applied across polities will neither deliver universal or uniform results (Sayer Citation2000). Rather, territorialization is a function of what historical institutionalists dub critical junctures. These are key points in time when contingent factors align to disrupt path dependency – or, ‘the dynamics of self-reinforcing or positive feedback processes in a political system … [Involving] mechanisms that reinforce the recurrence of a particular pattern into the future … ’ (Skocpol and Pierson Citation2002, 6). Applied to the present case, critical junctures break the path-dependent logic of centralized third sector administration in union states and lead to the emergence of new meso systems. Often critical junctures arise from state actions in response to significant external threats (such as war) – or major political initiatives (such as those designed to reform governance and democracy). As Thelen (Citation1999, 390) observes, attention to contingency involves, ‘close examination of temporal sequences and processes as they unfold … [It] focuses on variables that capture important aspects of the interactive features of ongoing political [and social] processes, and explains important differences in regime and institutional outcomes’.

This approach is relevant to contemporary study of third sector administration for the following reason: it underlines that any attempt to understand social processes in a given civil society setting needs to be cognizant of how the social space for action is at once shaped by the historical development of the polity and also the areal qualities specific to different geographical localities (inter alia, prevailing notions of national identity, patterns and processes of voluntarism, and the existence of inequalities). In ontological terms this has powerful implications for the study of welfare decentralization. It means empirical work must take into account a full range of contingent factors and critical junctures that influence and shape territorialization and re-spatialisation.

Research context and methods

The case selection rationale is founded on a number of factors: 1. in a global context, Wales is typical of other historical nations and regions absorbed into (quasi-)federal and union states, making it appropriate to regional studies and exploring the territorialization of third sector welfare (Royles Citation2006); 2. The UK features strongly in the empirical literature on welfare state development (Anttonen, Häikiö, and Stefánsson Citation2012), but much of this continues to promulgate the fallacy of a single welfare state; 3. From an international perspective, Wales is a propitious research context for it has played a key role in the development of social welfare, notably the development of state healthcare; and, 4. The present analysis is facilitated by a rich longitudinal dataset spanning nine decades.

Space constraints do not allow for an exhaustive account of the socio-economic and historical characteristics of the case study polity. Yet key features of this country of three million inhabitants include its language and culture. It is one of three nations that make up Great Britain. With the province of Northern Ireland, they constitute the United Kingdom (UK), an example of a ‘Union State’. Wales’ legal code and indigenous institutions were largely pushed aside as it was incorporated into the legal and administrative structures of England in the sixteenth century (Rawlings Citation2003). In consequence, prior to the twentieth century, the Welsh language and culture were the principal markers of national distinctiveness (Morgan Citation1990). Subsequently, civic nationalism and governance shifts have seen the constitutional ‘re-emergence’ of Wales as a distinct polity. Today it has a national parliament with broad policy responsibilities and tax-raising powers. Against this backdrop, the country’s third sector is comprised of 33,000 third sector organizations (TSOs) (NCVO Citation2018); with international comparative analysis concluding that ‘civil society in Wales is relatively well developed, with a strong value base. It operates in a generally supportive environment, and has a high impact on society’ (Civicus Citation2005, 8).

In methodological terms, the current study presents corpus analysis of the annual reports of the principal representative body – or ‘council’ of the third sector in Wales 1934–2018. Today it is called the Wales Council for Voluntary Action (WCVA). Its strategic priorities include good governance, influencing and engagement, volunteering and resourcing a sustainable voluntary sector. Membership of the Council is made up of charities, voluntary and community groups, and social enterprises. The Council’s annual reports comprise our case study data set. They summarize the activities of the Council over the preceding year. Typically 5,000 words long, they provide a rich social history and chronicle the development of voluntarism in Wales.

The discourse analysis was operationalized using content analysis to examine issue-salience and framing. The latter tells us about the inherent textual meanings and messages in the corpus. Archive hardcopy documents were scanned and converted to searchable text. The corpus was coded using an inductive coding frame based on key frames derived from the literature on third sector representation and administration (see online supplementary file). It was analysed using the UAM CorpusTool 3.3h©.

Case study: exploring the meso territorialization of third sector administration and welfare delivery

In this section we apply the inductive analytical model to the case study data. Attention first centres on the contingent factors. As and the earlier discussion shows, these fall into three spheres. The second part of the discussion is based on close textural analysis of the longitudinal data and identification of critical junctures.

Contingent factors

In accordance with the analytical model the following discussion is structured around consideration of each sphere of contingent factors: governance, organizational and socio-economic/historical.

Governance

The political opportunity structures for the emergence and development of meso third sector systems are shaped by the degree of unitary state centralization (, factor 1a). In turn, this links to political ideology (and the extent to which dominant parties in central government are supportive of unionism and centralized administration), as well as institutional structures and legal and administrative practices (and whether these are conducive to reform/decentralization). The present case study evidences how the Council actively pressed territorial claims upon central (unionist) government at Westminster. For example, we make

a plea for reasonable recognition … the Council has circulated all Departments in Central Government and all Welsh MPs [Members of Parliament], and it is hoped that the facts presented will help organisations in Wales to continue their work … the Council will persist in pressing the claims of legitimate movements who are doing an immense amount of work for the welfare of their fellow citizens. (CSSW Citation1979, 6)

Trust in government (1c) is a predictor of exogenous organizations’ policy engagement (Mishler and Rose Citation2001). It is also key in shaping welfare territorialization for, as Braithwaite and Levi (Citation2003, 240) observe, ‘in the case of the levels of government, proximity would appear to be a major factor in helping to determine the differential foundations for establishing and maintaining trust’. Thus, when applied to the development of meso systems, if third sector organizations and volunteers exhibit greater trust in local governance and mistrust central government (e.g. as being alien or neglectful of local interests), then the propensity to press for government decentralization increases. The present case study supports this thesis. For example, ‘there can be no doubt that Wales does suffer in comparison with other parts of the United Kingdom in the support it receives from [central] Government for Voluntary Work’ (CSSW Citation1979, 6).

Analysis of the case study data also shows that, as devolved government institutions develop, there is increasing engagement and sectoral scrutiny of government at the meso level. For example:

In order to influence how the Welsh Office interprets and implements the report [on third sector funding], the WCVA held a briefing session for voluntary organisations on the content and implications of the scrutiny, in order to stimulate informed debate. It will form the basis of a Welsh voluntary sector response and discussion with the Welsh Office. (WCVA Citation1990, 40)

lobbying for resources to build the capacity of third sector service providers, leading to commitment in the Strategic Action Plan for the Voluntary Scheme, The Third Dimension, to establish an Invest to Serve fund to build the sector's capacity to deliver public services. (WCVA Citation2008, 19)

In a land and a day in which local income for social services is at its lowest ebb, when the very fabric of social institutions is rotting for lack of paint and repair, and when the flower of our young manhood, with all its potentialities of leadership, is leaving us in a steady flow. The ensuing pages record the work of the South Wales and Monmouthshire Council of Social Service, in the past year, to help in facing these overwhelming problems … Voluntary Social Service is … the nurse of a sick society ministering to such needs as it can, proffering fellowship in an hour of distress, and, through it, planning for the fuller use of new health when at last it comes (SWMCSS Citation1935, 4).

Economic problems which seem to be worsening … The new Government has also said that it is going to encourage volunteers to fill some of the gaps that are created through cut-backs … it is essential to emphasise that this is a time when there can be a meaningful dialogue [… with] the Voluntary Movement on how the citizen who is disadvantaged can be helped in a practical manner. This means that the Voluntary Movement is given its rightful place alongside Statutory Social Service Schemes (WCVA Citation1979, 6).

The presence of social entrepreneurs (2c) is a further territorializing contingent factor that aligns with ‘supply-side’ theory in non-profit development (Salamon and Anheier Citation1996). It underlines the role of human agency in the territorialization process; specifically, through the presence of ‘social entrepreneurs’. As Nicholls (Citation2011, 34) explains,

such individuals sometimes conform to the heroic norms and distinctive personality traits associated with conventional entrepreneurs such as risk-taking, creativity, an overly optimistic approach to analysis, and bricolage, but significantly, they are more likely to draw on the communitarian, democratic, and network-building traditions that have always underpinned civil society action.

the outlook for the next few years will be challenging, but the sector’s combination of innovation, agility, and social entrepreneurship, will bring hope to the many who depend on its services and activities to enrich their lives and those of future generations. (WCVA Citation2009, 2)

Staff Structure: In order to meet the objectives our staff has been considerably changed and their functions re-designated … Now for the first time the Council will have Officers who will liaise generally with the voluntary movement in both north and south Wales … already there is ample evidence that staff are getting to grips with practical problems of both national and local significance. (CSSWM Citation1977, 9)

The overall aim of the Council is to promote, support and facilitate voluntary action and community development in Wales. In pursuit of that aim the Council will be guided by the following principles: to employ the strength of local identity as a resource by giving encouragement to local associations. (CSSW Citation1982, 2, see also discussion of national identity below)

The extent of social inequalities at the meso level is a further contingent factor that can promote territorialization as third sector organizations mobilize at a regional level to fight discrimination and oppression (inter alia, around nationality, (minority) language rights – as well as across ‘protected characteristics’) (3c). Furthermore, as Esping Andersen’s (Citation1990, 31–32) work underlines, this also extends to socio-economic matters. Class relations and patterns of need shape the character of welfare regimes (see factors 1d and 1e – above) – including the role of the third sector in the mixed economy of welfare. Here three factors are germane: (1) the nature and extent of working class mobilization; (2) the types of coalitions working class elements are able to secure; and (3) the disposition of new middle class elements towards welfare provision. The contingent nature of inequalities in sectoral territorialization is to the fore in the case study data. For example, in the Articles of Association of the Council its purposes include ‘the relief of poverty, distress and sickness … It must be remembered these words were written before the advent of the Welfare State’ (CSSW Citation1964, 7) and, a later annual report states our goal is to ‘help build a civil society in Wales that is inclusive and promotes equality’ (WCVA Citation2009, 1).

The territorialization of third sector systems at the meso level is also contingent upon prevailing levels of social capital (3e). The latter term refers to the ‘features of social organization, such as trust, norms, and networks’ underpinning voluntarism (Putnam Citation1993, 167). It is a resource for collective action. In this case, this is concerned with revising pre-existing third sector institutions and practices away from centralized to meso-territorial administration. The reason for this lies in the notion of ‘embededdness’ (Portes Citation1995, 13). This is the idea that social capital is ‘embedded’ or linked to local patterns of associative life and is ‘spatially-grounded’ in a given territory. Ergo, its presence is necessary as a resource for re-scaling sectoral administration along regional lines for it is intimately concerned with territorial integrity and meso-norms of voluntarism and philanthropy (3f), as well as social networks linked to identity and the notion of the (meso) nation or region. It is a trope that is evident in the present analysis. For example, reference is variously made to ‘the traditional role of volunteers giving freely of their time and energy … voluntaryism (sic) … This Council stands or falls by this conviction [… and the] activities of those who genuinely desire to serve their neighbours’ (CSSWM Citation1963, 7); and ‘the role of the sector is … dependent on having a strong community and vibrant local organizations – not just to support people, but also to enable them to feel valued and contribute to their own communities’ (WCVA Citation1997, 4).

Economic prosperity is a further contingent factor shaping sectoral territorialization (3g). It underpins the probabilistic relationship between the amount of revenue available to government from taxation and welfare expenditure at the meso level (factors 2a, 1e). Moreover, general income levels amongst the population determine the affordability of commodified welfare and taxation paid to the state (factor 1d), as well as the degree of income inequalities and class-based mobilization (factor 3d). Furthermore, the strength of the economy influences local patterns and processes of voluntarism; not least through shifts in labour market engagement for sections of the population and the concomitant effect on time availability for voluntary action (Warburton and Crosier Citation2001). The contingent nature of economic prosperity is a key trope in the present case study data. For example,

everyone knows that the storm-clouds over the national economy have finally burst in a downpour of inflation and soaring costs. This has been accompanied by a fall in the amount of money available from charitable institutions and the general public [… as well as] a serious drop in the grants on which we have relied in the past, for many important areas of our work. (CSSW Citation1975, 2)

The foregoing analysis affirms the salience of the contingent factors to understanding the territorialization of third sector welfare. We now turn to the second aspect of our analytical framework, critical junctures.

Critical junctures

The following details five critical junctures identified by textual analysis of the longitudinal case study data (). Each is now considered in turn.

Table 1. Case study: critical Junctures and corresponding contingent factors in the meso territorialization of third sector administration and welfare delivery in Wales.

Strategic planning associated with the Second World War

For administrative reasons the Second World War constitutes a critical juncture in the meso-territorialization of welfare. Specifically, the demands of war expose shortcomings in central government’s policy-reach. It then uses the Council to administer aspects of social welfare in Wales. The case study data detail how this transition required the Council to expand and morph from a local to an all-Wales body. Thus the future representative third sector body in Wales, South Wales and Monmouthshire Council of Social Service (SWMCSS), began its work in 1934; predating much of the social protection that came with the development of the British welfare state. This lends credence to the observation that, ‘non-profit organizations are often active in a field before government can be mobilized to respond [and they] develop expertise, structures, and experience that governments can draw on in their own activities’ (Salamon and Anheier Citation1996, 16). Initially, SWMCSS was a local voluntary organization concerned with the provision of welfare (such as employability schemes, poverty reduction initiatives and social care). It operated in industrialized areas affected by the depression and poverty. Its goals rapidly broadened. A miners’ welfare committee was established in 1933. The Council’s provision of a raft of training, social care, support and advice activities followed. In 1940 the Council reported that

The year of the war has presented the Council with many new demands which it has tried to face, without at the same time neglecting those people for whose welfare it has had a special responsibility in the last seven years. (SWMCSS Citation1940, 3)

The unpreparedness of voluntary organisations in face of the crisis of 1938 resulted in a determined effort in succeeding months to remedy the deficiency. By the outbreak of war a Standing Conference of Welsh Voluntary Organisations had been brought into being which set itself to ensure that the maximum effort should be put forth in time of war to ensure the greatest economy of voluntary service compatible with efficiency (CSSWM Citation1940, 3).

there is a great need in Wales, both in town and country for an efficient, forward looking, co-ordinating social service agency which will cover the whole Principality [i.e. Wales]. Nowhere are there more formidable difficulties of geography, finance, and organisation to be overcome. (CSSWM Citation1947, 7)

Government restructuring: a new, territorial government ministry for Wales

During the 1950s and 60s a resurgent nationalist movement in Wales was pressing for home rule (Morgan Citation1990). In their manifesto for the 1959 general election the left-of-centre Labour Party proposed the creation of a territorial ministry of the British state to be run by a Secretary of State for Wales (Chaney Citation2013). This would have executive powers and determine expenditure on public services delegated from Westminster. The creation of the Welsh Office in 1964 is the second critical juncture in the territorializing of third sector administration. Its principal significance lies in the creation of the first all-Wales institution of government in modern history with which the nascent third sector body could engage. Government was keen to encourage this. The Minister of Welsh Affairs addressed the CSSWM in 1962 and affirmed that:

The growth of bodies like the Council of Social Service with a broad overall view has been of great value in co-ordinating separate efforts. It has done much to bring about a necessary unity, but it is arguable that it has never yet played the full role for which it was designed. [Strikingly, he then posed the rhetorical question …] should the Council of Social Service do more to interpret Wales to herself? (CSSWM Citation1962, 8).

One of the lessons to be learned in our modern society is the necessity to work together for the common good [… This can only be achieved by] working in concert with Voluntary Organisations. In Wales, the task of uniting these voluntary organisations is the first responsibility of this Council. In all its Departmental activities the Council endeavours to bring those responsible for statutory services around a table with individual groups working in communities in the spheres of health, welfare and education (CSSWM Citation1966, 9).

By the early 1970s the CSSWM reported that it was making ‘very fast progress’ in establishing its national, Welsh role. Reference to its work for disabled people clearly illustrates this. For example, the contemporary record notes that this, ‘could only have been undertaken by a Welsh national service bringing together disabled organisations’ (CSSWM Citation1973, 22). Just a decade on from the creation of a territorial ministry for Wales, the CSSWM’s assessment is one of ‘excellent working arrangements with the Welsh Office … fulfil[ling] one of its main objectives as a consultative and co-ordinating body’ (CSSW Citation1975, 4). Between 1964 and 1974 the case study data reveal the third sector body’s transition from welfare body to an institution with growing ambition to become a ‘player’ in the Welsh political landscape. For example, ‘it is to be hoped that in the coming year the new Council will consolidate its position as an important element in Welsh affairs’ (CSSWM Citation1972, 6); and ‘the newly reconstructed Council [now renamed the Council for Social Services Wales or CSSW]Footnote2 is, I feel, ready to play a vital and central role throughout the Principality’ (CSSW Citation1972, 2).

Thatcherite reforms

In 1979 the election of a right wing government headed by Margaret Thatcher led to a number of reforms that constitute the next critical juncture. The government’s monetarist policies saw a major rise in unemployment accompanied by deep cuts in public expenditure. The following extract from the Council’s records illustrates the impact of the reforms:

During the last eighteen months, the country has faced a transformation as a result of Government fiscal and economic policies. Latest reports show that one in every eight males, and one in every twelve females, of the Welsh workforce is unemployed. The social implications of these policies, and the serious consequences that face individuals, families and Communities are universally recognised. Naturally, social and Community provisions are affected. Central and Local Government Grants have been reduced … there are signs that most of these Organisations have to curtail spending and programmes’ (CSSW Citation1980, 6).

taking a firm line on the question of the use of Volunteers in Public Services, especially when those previously working in this sector have been made redundant … Volunteers we recruit must not fill the places of those who have lost their jobs. (CSSW Citation1981, 4)

In 1983 the Council again changed its name from CSSW to Wales Council for Voluntary Action (WCVA). More than symbolic, the change reflected the reciprocal way in which governance shifts (principally, Thatcherite reforms and the strengthening role and policy-reach of meso government) promoted functional change in the sector. In short, a process of politicization was at work as the Council extended its remit, and placed greater emphasis on representation and policy work, whilst continuing with its social service provision. As the following extract illustrates, deteriorating relations with government prompted the Council to assert its independence:

We are an independent institution, whose members are voluntary organisations in Wales, and its function is to promote and support voluntary action through development work, through the giving of services [… it is] a national institution which asserts the importance of voluntary action for the health of society: which advocates a consideration in policies and programmes for a proper recognition of voluntary initiative (WCVA Citation1984, 2).

Third sector compacts

The next critical junctures follow in swift succession. The fourth came in 1997 with the advent of voluntary sector ‘compacts’. These were formalized contracts setting out the parameters and expectations of state-third sector relations. They reflected the change of government at Westminster and the New Labour administration’s emphasis on partnership working. Their effect was to formalize the territorialization process for the UK government required bespoke compacts from the territorial ministries for Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (and Westminster in the case of England). This shift is described in the Council’s report of the time as ‘a major step forward’, noting that the ‘government is determined to forge the strongest possible links with the voluntary sector and to support it in every way it can’ (WCVA Citation1998, 3). It went on to note that the new relationship,

will be built on integrity, trust and mutual respect. It will commit the Welsh Office to: Clear policies on volunteering, community development and voluntary organisations, and measures to support them; consultation with the sector on policy changes; [and] a range of measures to improve funding mechanisms. (WCVA Citation1998, 3)

Devolution

The fifth critical juncture followed shortly afterwards when in 1999 the Welsh Office was replaced by a new elected legislature, the National Assembly for Wales (latterly, the Welsh Parliament or Senedd Cymru). This again illustrates the iterative, reciprocal state-third sector relationship at work in the process of territorialization. Notably, pro-devolution activists in the political elite were keen to encourage the involvement of the sector in the design of the new elected government body for Wales. Thus, at the time the National Assembly’s First Minister asserted that: the new legislature ‘must recognise the voluntary sector as a key player and partner … at the heart of our work to build a better Wales’ (cited in Dicks, Hall, and Pithouse Citation2001, 148).

The cornerstone of the new arrangements was a statutory partnership between the National Assembly for Wales and the voluntary sector (Government of Wales Act 2006, s.74).Footnote3 The statutory provisions also stated that the key nexus with government was to be the sector’s representative body, the WCVA. The significance of these developments was not lost on those writing at the time:

there can be no doubt that as the voluntary sector has moved centre stage in national politics in Wales, so has the WCVA. It has been centrally involved in the process of drawing up devolution legislation and preparing [National] Assembly procedures. As a result, the WCVA has entered the era of devolution with expectations of being a significant and key player in the Assembly and its development. (Dicks, Hall, and Pithouse Citation2001, 156)

Discussion

The wider significance of this study is both theoretical and empirical. In the former regard, it makes an original contribution by synthesizing neo-institutionalism and critical realism with Salamon and Anheier’s (Citation1996) classic framework on civic infrastructure development to offer an inductive, systemic analytical model of contingent factors shaping the meso-territorialization of third sector welfare in federal and union states. Moreover, we go beyond earlier discrete approaches to exploring territorialization that centre on single factors such as neo-liberalism and marketization. Instead, we conceptualize decentralization in terms of a raft of temporal and spatial variables. Our core finding is that welfare decentralization is driven by discontinuity at critical junctures related to factors such as governance transitions, national crises and political shifts.

The application of the model to the case study data allows us to reflect upon the evolution of sub-national welfare and the significance of UK devolution to state-third sector relations. The longitudinal analysis reveals how the governance transitions associated with devolution consolidated an earlier process of territorialization when, during the crisis of the Second World War, the Westminster government turned to SWMCSS for welfare coordination and delivery on an all-Wales basis; breaking with the previous British structures of welfare and voluntary sector administration. Indeed, in this regard the territorialization of the third sector in Wales in the 1940s and 1950s can be seen as a precursor to political devolution in the 1990s. Devolution then accelerated the Council’s shift from a sole concern with welfare delivery to a more politicized way of working. Notably, the creation of the Welsh Office in the 1960s drew the Council into lobbying government on behalf of the sector in order to shape public policy and services. Thatcherite reforms in the 1980s deepened this process of politicization. Whilst the (re-)creation of a national Welsh legislature in 1999 further transformed matters by institutionalizing – and giving legal effect to, the prevailing political discourse around partnership working with government.

At this point it is useful to reflect on how the Welsh case fits with extant work and wider trends. First, it underlines the iterative, reciprocal relationship between governance reforms and third sector territorialization. The emergence of the Welsh Council in the 1930s also illustrates how meso-territorialization can originate as a response to welfare demand in the face of economic depression and pronounced inequalities compounded by state and market failure in the delivery of key public goods. Subsequent development of the sector also underlines the influence of socio-economic factors including national identity, language and culture. This is consonant with the existing body of work on the role of civic nationalism in driving welfare decentralization. The extended time taken to fully establish the Council on an all-Wales basis (completing an organizational infrastructure for the Council in the north of Wales lagged behind institutional development in the south) also has wider significance. It supports the social origins thesis (Salamon Citation1970) because it reveals how meso-territorialization depends on prevailing levels of social capital, the presence of social entrepreneurs, the strength of third sector networks and organizational density. The developing relationship with the Welsh Office in the 1970s sees the Council drawn into fulfilling government contracts on skills and employability training. This led to the Welsh Office’s increasing oversight of the Council – a trend that resonates with earlier work on welfare decentralization and the quest for new forms of accountability and performance monitoring (Seabright Citation1996). Moreover, the Council’s dogged opposition to Thatcherite reforms supports earlier work on resistance to central and federal policies as a further driver of territorialization (Mooney and Scott Citation2012).

The wider contribution of this study to social research lies in highlighting the temporal and spatial factors at work in territorializing welfare in a sub-national European polity, thereby extending understanding of how, ‘voluntary and community sector groups are agents of a complex process of “scalar manoeuvring” whereby … governance is produced and contested across a range of sites both within and across spatial scales’ (Kythreotis and Jonas Citation2012, 382). This study’s analytical framework is designed to inform future empirical investigation and be applied in other contexts. The global trend of state restructuring and international prevalence of federal and union states gives this broad salience and paves the way for further holistic studies of third sector welfare decentralization.

inductive_coding_frame.docx

Download MS Word (12.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge grant funding by the Economic and Social Research Council under Award No. S012435/1 and the helpful and constructive comments of the editor and two anonymous reviewers when revising an earlier draft of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See also http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/59013f44-fd4a-4950-b968-958ccce46c70 [Last accessed 24.06.20]

2 This name change simply reflects the fact that for most of the twentieth century the ‘national’ position of the county of Monmouthshire was indeterminate. Local government reorganization in the 1970s eventually allocated it to Wales.

3 This clause replaced a similar one in the 1998 Act.

References

- Anderson, B. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. 2nd ed. New York: Verso.

- Anttonen, A., L. Häikiö, and K. Stefánsson. 2012. Welfare State, Universalism and Diversity. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bailey, K. 2001. “Systems Theory.” Chap. 19 in Handbook of Sociological Theory, edited by Jonathan Turner, 379–401. New York: Springer.

- Bello, V. 2011. “Collective and Social Identity: A Theoretical Analysis of the Role of Civil Society in the Construction of Supra-National Societies.” In Civil Society and International Governance: The Role of non-State Actors in Global and Regional Regulatory Frameworks, edited by Armstrong et al., 31–48. London: Routledge.

- Benford, R. D., and D. A. Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–639. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Bergh, S. 2012. “Introduction: Researching the Effects of Neoliberal Reforms on Local Governance in the Southern Mediterranean.” Mediterranean Politics 17 (3): 303–321. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2012.725299

- Bergman, A. 2007. “Co-Constitution of Domestic and International Welfare Obligations: The Case of Sweden’s Social Democratically Inspired Internationalism.” Cooperation and Conflict 42 (1): 73–99. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836707073477

- Borghi, V., and R. Van Berkel. 2007. “New Modes of Governance in Italy and the Netherlands: The Case of Activation Policies.” Public Administration 85 (1): 83–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00635.x

- Braithwaite, V., and M. Levi. 2003. Trust and Governance. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Brenton, M. 1985. Voluntary Sector in British Social Services. London: Longman.

- Chaney, P. 2013. “An Electoral Discourse Approach to State Decentralisation: State-Wide Parties’ Manifestos on Scottish and Welsh Devolution 1945–2010.” British Politics 8: 333–356. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2012.26

- Chaney, P. 2014. “Multi-level Systems and the Electoral Politics of Welfare Pluralism: Exploring Third-Sector Policy in UK Westminster and Regional Elections 1945–2011.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 25 (1): 585–611. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9354-9

- Chaney, P. 2017. “‘Governance Transitions’ and Minority Nationalist Parties’ Pressure for Welfare State Change: Evidence From Welsh and Scottish Elections – and the UK’s ‘Brexit’ Referendum.” Global Social Policy 17 (3): 279–306. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018116686922

- Civicus. 2005. An Assessment of Welsh Civil Society – Civicus Civil Society Index Report for Wales. London: Civicus.

- Council of Social Service for Wales. 1974–1982. Annual Reports. Cardiff: CSSW.

- Council of Social Services for Wales and Monmouthshire. 1940. Annual Report. Cardiff: CSSWM.

- Council of Social Service for Wales and Monmouthshire. 1946–1972. Annual Reports. Cardiff: CSSWM.

- Council of Social Services for Wales and Monmouthshire. 1964. Annual Report. Cardiff: CSSWM.

- Council of Social Services for Wales and Monmouthshire. 1972. Annual Report. Cardiff: CSSWM.

- Council of Social Services for Wales and Monmouthshire. 1973. Annual Report. Cardiff: CSSWM.

- Council of Social Services for Wales and Monmouthshire. 1977. Annual Report. Cardiff: CSSWM.

- Crowson, N. 2011. “Introduction: The Voluntary Sector in 1980s Britain.” Contemporary British History 25 (4): 491–498. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2011.623861

- Dicks, B., T. Hall, and A. Pithouse. 2001. “The National Assembly And The Voluntary Sector: An Equal Partnership?” Chap. 5 in New Governance- New Democracy? Post Devolution Wales, edited by P. Chaney, T. Hall, and A. Pithouse, 78–102. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Esping Andersen, G. 1990. Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press and Princeton, Princeton University Press.

- Flora, P., and J. Alber. 1981. “Modernization, Democratization and the Development of Welfare States in Western Europe.” In The Development of Welfare States in Europe and America, edited by P. Flora, and A. Heidenheimer, 37–80. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

- Gerrits, L., and S. Verweij. 2013. “Critical Realism as a Meta-Framework for Understanding the Relationships Between Complexity and Qualitative Comparative Analysis.” Journal of Critical Realism 12 (2): 166–182. doi: https://doi.org/10.1179/rea.12.2.p663527490513071

- Itçaina, X. 2010. “An Institutionalization from Below? Third-Sector Mobilizations and the Cross-Border Cooperation in the Basque Country.” Centre for International Borders Research, Working Paper No.19, Queens University Belfast. https://www.qub.ac.uk/research-centres/CentreforInternationalBordersResearch/Publications/WorkingPapers/CIBRWorkingPapers/Filetoupload,184453,en.pdf.

- Kay, A. 2005. “Territorial Justice and Devolution.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 7: 544–560. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2005.00200.x

- Kythreotis, A., and A. E. G. Jonas. 2012. “Scaling Sustainable Development? How Voluntary Groups Negotiate Spaces of Sustainability Governance in the United Kingdom.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30: 381–399. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/d11810

- López-Santana, M. 2015. The New Governance of Welfare States in the United States and Europe: Between Decentralization and Centralization in the Activation Era. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Mishler, W., and R. Rose. 2001. “What Are The Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies.” Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414001034001002

- Mooney, G., and G. Scott, eds. 2012. Social Justice and Social Policy in Scotland. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Morgan, K. 1990. Wales in British Politics, 1868–1922. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- National Council of Voluntary Organisation. 2018. Voluntary Sector Almanac. London: NCVO.

- Nicholls, A. 2011. “Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurs.” Chap. 11 in The Oxford Handbook of Civil Society, edited by M. Edwards, 342–344. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pavolini, E. 2015. “How Many Italian Welfare Systems are There?” In The Italian Welfare State in a European Perspective, edited by U. Ascoli, and E. Pavolini, 283–301. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Portes, A. 1995. “Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

- Putnam, R. 1993. Making Democracy Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rawlings, R. 2003. Delineating Wales: Constitutional, Legal and Administrative Aspects of National Devolution. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Rodriguez-Pose, A., and N. Gill. 2003. “The Global Trend Towards Devolution and its Implications.” Environment and Planning C, Government and Policy 21 (3): 333–351. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/c0235

- Royles, E. 2006. “Civil Society and the New Democracy in Post-Devolution Wales — A Case Study of the EU Structural Funds.” Regional & Federal Studies 16 (2): 137–156. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560600652031

- Salamon, L. 1970. “Comparative History and the Theory of Modernization.” World Politics 23 (1): 83–103. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/2009632

- Salamon, L., and H. Anheier. 1996. “Social Origins of Civil Society: Explaining the Nonprofit Sector Cross-Nationally.” Working Papers of the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, no. 22. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies.

- Sayer, A. 2000. Realism and Social Science. London: Sage.

- Seabright, P. 1996. “Accountability and Decentralisation in Government: An Incomplete Contracts Model.” European Economic Review 40: 61–89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(95)00055-0

- Skocpol, T., and P. Pierson. 2002. Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science. New York: W.W. Norton.

- South Wales and Monmouthshire Council of Social Service (SWMCSS). 1934–1946. Annual Reports. Cardiff: SWMCSS.

- Steinmo, S., K. Thelen, and F. Longstreth, eds. 1992. Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thelen, K. 1999. “Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 2 (1): 369–404. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.369

- Titmuss, R. 1974. Social Policy: An Introduction. New York: Pantheon.

- Verschuren, P. 2001. “Holism Versus Reductionism in Modern Social Science Research.” Quality & Quantity 35: 389–405. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012242620544

- Wales Council for Voluntary Action. 1979. Annual Report. Cardiff: WCVA.

- Wales Council for Voluntary Action. 1983–2017. Annual Reports. Cardiff: WCVA.

- Walzer, M. 1990. Kritik und Gemeinsinn. Berlin: Fischer.

- Warburton, J., and T. Crosier. 2001. “Are We Too Busy To Volunteer? The Relationship Between Time and Volunteering Using the 1997 ABS Time Use Data.” Australian Journal of Social Issues 36 (4): 295–314. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2001.tb01104.x

- Weisbrod, B. 1977. The Voluntary Nonprofit Sector. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Wimmer, A., and N. Glick Schiller. 2002. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2 (4): 301–334. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0374.00043