ABSTRACT

In societies divided along ethnocultural lines, intergroup cooperation can often be a challenging task. This process can be even more complex if political parties and voters are divided along those same social cleavages. This study focuses on the case of Belgium and explores whether divided societies with separate party systems necessarily lead to distinct partisan alignments. Using electoral survey data from the 2014 Belgian federal election, we investigate whether political ideology is stronger than ethnolinguistic group membership in shaping electoral behaviour. The results demonstrate that although Belgian voters are divided along linguistic lines when it comes to preferences about centralization, they remain aligned along party families on social and economic dimensions.

In divided societies, establishing separate political institutions is sometimes seen as a way of mediating and preventing further conflict. While there is a debate on whether political partition along ethnocultural lines assuages or exacerbates division (Anderson Citation2016; McGarry and O'Leary Citation2009), this strategy creates two (or more) separate political worlds that have their own distinct dynamics. Though political elites from each side may come together from time to time to negotiate nation-wide compromises, they can only ultimately be held to account come election time by voters from their own group. This situation creates a perverse incentive for more entrepreneurial political elites to stir up intergroup tensions for their own gain. Therefore, institutional arrangements may promote, or even heighten, existing differences in political culture between the different groups (Cornell Citation2002; Lorwin Citation1968). While political divisions have had a prominent place in the political science literature (see Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967), the exact implications of such divisions on citizens’ attitudes or partisan alignments have been somewhat overlooked. This is especially true regarding how citizens vote along ethnoregional lines.

Belgium is often cited as an example of a ‘divided society’. Dutch-speakers in Flanders and French-speakers in Wallonia and much of the Brussels Capital Region, lead seemingly separate lives while living in the same country. With separate education systems and media landscapes, Belgium’s recent history has been marked by various disagreements over language, many of which inevitably spill over into the political realm. However, the country also has separate party systems organized along this divide, in effect creating two distinct electorates (Van Haute and Deschouwer Citation2018). While not all socio-political tensions in Belgium are about language, the separate socio-political institutions force most inter-regional disagreements to be refracted through a linguistic lens. This, furthermore, not only complicates decision-making on issues of national jurisdiction but also weakens, or ‘hollows out’, the federal government and its institutions (Hooghe Citation2004; Swenden and Jans Citation2006). Once a unified and centralized state, previous social conflicts led the political system to gradually diverge along the regional boundaries, with political parties in both regions eventually being organized and operated as separate entities.

Yet, recent years have seen efforts to go beyond the ethnocultural divide and work together along coherent political lines. The most striking of these endeavours has arguably been the attempts by Dutch-speaking Groen and French-speaking Ecolo green parties to work together. The two parties not only formed a single bilingual group (political faction) in the Belgian Federal Parliament, but also campaigned under a joint and bilingual list for the federal elections in the Brussels region (Dandoy Citation2015; De Winter and Wolfs Citation2017). These efforts to work together across ethnoregional lines in maintaining a well-aligned political ideology lead us to ask the following question: Do divided societies with separate party systems necessarily mean distinct partisan alignments? We wonder whether ideology behaves similarly in shaping citizens’ vote choice across such ethnoregional or ethnolinguistic divides.

To answer this question, we use data from the PartiRep survey for the 2014 Belgian federal election (Deschouwer et al. Citation2015) and an ideological framework that explores centralization, economic, and social ideological dimensions in an independent manner. The results highlight two important findings. Firstly, when we look specifically at voter ideology, similar parties tend to attract similar voters across the linguistic divide. Secondly, we contribute to the understanding of electoral behaviour in divided societies by exploring the relationships between regionalism, ideology, and vote choice. Contrary to expectation, we find that ethnoregional divides do not necessarily lead to differing voting patterns, even when such divides are reflected in the party system.

The paper proceeds in five parts. The first section discusses the literature on electoral dynamics in divided societies. The second section presents the Belgian case. Next, we present our hypotheses for the study. After discussing the data, we show our empirical analyses based on voter attitudes. We then close with a short discussion on the potential implications of our findings for divided societies.

Elections in divided societies

In states with salient ethnocultural divisions, political parties can organize themselves according to these same social divisions. Parties within each segment can either form post-electoral coalitions, like in Belgium, or formal pre-election coalitions, like the Barisan Nasional in Malaysia. Reilly (Citation2006:, 812) states that in societies that are divided along ethnocultural lines, ‘it is often easier for campaigning parties to attract voter support by appealing to ethnic allegiances rather than issues of class or ideology.’ The result is that such societies often deal with a party system that has some elements of ethnic partisanship (Horowitz Citation1985).

These intergroup political divides can be amplified by power-sharing structures that are based on ethnic, linguistic, or religious divisions. For instance, Erk and Koning (Citation2010) find that linguistic heterogeneity often leads to increased decentralization so that institutions come to reflect the linguistic structure in a given country. Power-sharing structures in plural societies, such as consociationalism, aim to provide autonomy and power for each constituent member to be satisfied (Lijphart Citation1977). However, these structures can also institutionalize the divide between societal segments, as each group can develop its own media outlets, political culture, and party system. On this point, Horowitz (Citation1985) argues that power-sharing structures can actually heighten ethnic tensions, since the ‘grand coalition’ requirements lead to ethnic outbidding between intra-group elites. In addition, the greater the importance of ethnic parties for the electoral system, the lower the levels of ideological coherence will be (Gunther and Diamond Citation2001).

In political contexts divided along ethnolinguistic lines, mother tongue has been shown to be a determinant for individuals’ political attitudes and even vote choice (Bilodeau, Turgeon, and Karakoç Citation2012; Miley Citation2013), meaning that differing ethnolinguistic groups can have differing sociopolitical preferences. The situation is further complicated by the fact that even parties from the same party family (i.e. parties with different organizational structures, but with similar policy and ideological stances (see Mair and Mudde Citation1998)) can have diverging positions on core issues (Vasilopoulou Citation2018). Therefore, appealing to all segments of society in a country divided along language and region might be quite a political endeavour.

While divided societies can generate and depend on separate partisan offerings, division does not necessarily lead to complete political separation. For instance, Horowitz (Citation1990) emphasizes the need for political formations to appeal to all segments of a society in order to maximize the chances of achieving a peaceful sociopolitical climate. In some countries with important social cleavages, such as Canada, this led to ‘brokerage parties’ that try to reconcile these differences with programmes that accommodate and integrate such divisions (Carty Citation2015). Furthermore, even in a longstanding, deeply divided society such as Northern Ireland, not all citizens necessarily develop negative attitudes towards political parties that represent the opposing side of the social cleavage (Garry Citation2007).

In terms of political preferences, recent work exploring the ethnolinguistic divide in Canada has shown that citizens’ political attitudes are better predictors of political behaviour than their ethnolinguistic group or region (Medeiros Citation2017). While the scholarship tends to concentrate on the political preferences of the ‘average voter’ (Rivero Citation2015), individuals who share similar political preferences exist on all sides of a social cleavage. For instance, while one sub-national region might be on average more right-leaning and another region in the same country might prefer on average more left-of-centre policies, there will inevitably be left-leaning citizens in the former and right-leaning ones in the latter. Consequently, citizens who share political preferences will tend to behave similarly across the divide (Montpetit, Lachapelle, and Kiss Citation2017). While it is fair to expect deeply divided societies to drift apart politically, social divisions may not necessarily lead to profound political dissimilarities at the citizen level. Rather, individuals across the country may remain ideologically coherent despite the existence of a structuring ethnocultural divide.

Belgium: Living together, but separately?

Belgium is a case-study with ample fodder for critics of consociationalism, such as Horowitz (Citation1985). There are arguably few pan-national ‘Belgian’ social aspects, leading the country’s constituent groups to live relatively isolated from each other. This was brought on by tumultuous social upheavals in the 1960s which saw confrontations between Dutch-speaking—mainly in Flanders—and French-speaking populations—mainly in Wallonia—come to the forefront of national life (Huyse Citation1981). This in turn led elites to institutionalize differences through the creation of separate institutions (Deschouwer Citation2002; Erk and Koning Citation2010; Sinardet Citation2010). Such divisions along linguistic lines have been transposed onto the country’s political system. In fact, it may not even be possible to speak of a ‘Belgian’ party system, as political parties have split along linguistic lines since the 1960s and voters cast their ballot for a candidate/party affiliated with the linguistic community of their region of residence. Generally speaking, Belgians who live in Flanders vote for candidates from Dutch-speaking parties and those from Wallonia cast their ballots for French-speaking parties. The situation is slightly more complicated in the Brussels Capital Region, where parties from both sides of the divide present candidates.Footnote1 As a result, this segmented party system in Belgium plays an interesting role in reinforcing territorial cleavages.

While parties differ across regions, the country’s partisan landscape is still similar due to the existence of ‘sibling parties’. However, party system drift is nonetheless apparent and it has already been acknowledged that both regions produce majorities that tend toward different poles on the ideological spectrum (De Winter, Swyngedouw, and Dumont Citation2006). According to De Smaele (Citation2011), this is a historical curiosity that remains true. However, Billiet (Citation2011) notes that the left-right distinction between Flanders and Wallonia is overstated, as survey data reveal that the two regions are actually less divided than their elites’ political posturing might suggest. Still, Deschouwer and Reuchamps (Citation2013:, 267) have pointed out that the structure of the Belgian federal system is one in which ‘[e]lectoral wins and losses are increasingly different within the same party family. […] The overall result of the elections is – and always has been – a centre-right majority in the north and a centre-left majority in the south.’ This pattern is evident in both regional and federal elections. But it remains, according to Deschouwer and colleagues (Citation2017), that although these sibling parties in Belgium act very independently from one another and have varying levels of success in their respective region, they are, on the whole, ideologically quite similar.

The Belgian partisan landscape therefore provides an interesting opportunity to examine if ideology structures vote choice similarly or differently across an ethnocultural social divide.

Hypotheses

From the review of the literature and of the Belgian case, we identify two competing hypotheses.

First, while the political party literature recognizes the existence of sibling parties across regions in Belgium, this scholarship also points to the fact that ideology is very dissimilar—at least in the aggregate—across regions. Coupled with the literature on divided societies, this leads us to expect that the attitudes of Flemish and Walloon voters should also be distinct, as they should be influenced by their linguistic group membership rather than their ideological party family affinity. We therefore propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Voters from the same ethnolinguistic group are more similar to each other than voters from the same ideological parties.

H2: Voters from similar ideological parties are more similar than voters from similar ethnolinguistic groups

Data

To test our hypotheses, we make use of the PartiRep survey for the 2014 Belgian federal election (Deschouwer et al. Citation2015Footnote).2 The partisan dynamics of the 2014 Belgian federal election were quite similar to the previous one held in 2010, in which the N-VA became the dominant Flemish party (André and Depauw Citation2015). Seeing as the 2014 Belgian federal election is the most recent that is part of this new partisan era and for which survey data were available, it is thus suitable to test our hypotheses. We rescaled all the non-dichotomous variables used in the analyses to run from 0 to 1. Respondents who chose not to answer or responded ‘don’t know’ were excluded from all analyses.

We start with categorizing the Belgian political parties into the five main party families that span the linguistic divide, which represent around 85% of the votes cast for the Federal Chamber in 2014.Footnote3 The Christian Democratic party family contains the Dutch-speaking Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams (CD&V) and its French-speaking sibling party Centre démocrate humaniste (cdH). The Liberal family is formed of the Dutch-speaking Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten (Open VLD) and its French-speaking sibling party the Mouvement Réformateur (MR). The Socialist family is comprised of the Dutch-speaking Socialistische Partij Anders (sp.a) and the French-speaking Parti Socialiste (PS). The Green party family is made up of the Dutch-speaking Groen and the French-speaking Ecolo parties. Finally, the Regionalist party family is a unique party family in that it does not have sibling parties across the language divide (De Winter Citation1998; Van Haute and Pilet Citation2006). While the Francophone regionalist parties have declined in popularity,Footnote4 the main regionalist party on the Flemish side, the Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (N-VA), has become the dominant political force in Flanders. These parties were unified into nation-wide parties with a single party organization in the 1960s, but as De Winter (Citation2006) noted, there remains a lack of coordination mechanisms between party families across the language divide today, with the notable exception of the green parties.

Rather than use a unidimensional left-right framework, we have decided to test our hypotheses through the lens of three separate ideological dimensions. It has been argued that three separate ideological dimensions are necessary when examining vote choice in contexts with a strong ethnoregional divide: one that measures economic liberalism, one that measures social conservatism, and one that measures centralization (or preference for power to be concentrated at the centre in a society rather than at the periphery) (Gauvin, Chhim, and Medeiros Citation2016; Medeiros, Gauvin, and Chhim Citation2015; Wheatley et al. Citation2014). This strategy also allows us to see a more complete picture of the ideological congruence of niche parties, as previous research has supported that a single left-right ideological dimension is too broad (Bischof and Wagner Citation2020). Furthermore, a multidimensional framework allows to better understand partisan divisions in divided societies (Garry, Matthews, and Wheatley Citation2017).

These dimensions were captured by creating summative rating scalesFootnote5 However, it was impossible to do so for all dimensions. For the centralization and economic dimensions, we were not able to create scales that both presented eigenvalues over 1 and loaded into a single factor after principal component analysis (Tabachnick and Fidell Citation1996), or that showed sufficient reliability with high enough Cronbach’s α scores. Thus, we used questions that most explicitly captured the economic (support for the free market) and centre-periphery (power-sharing preferences) dimensions as proxies. The question asking where policy power should lie between the regional and federal levels was used as a proxy for the centralization dimension (variable v47). The answer choices were inverted to reflect the directionality of our dimension, meaning the variable was rescaled so that a 1 indicated preference for power to lie in the hands of the federal government. In the case of the economic dimension, we used a question that asks about the desired level of government intervention in free enterprise (variable v45), with the higher score indicating stronger support for the free market. A scale for the social dimension was constructed by combining three questions (variables v74, v75, and v76). These questions capture attitudes on diversity and immigrationFootnote6 The three questions’ answer choices were inverted to match the directionality of our dimension, where a higher score indicates support for social conservatism. Robustness checks were carried out by conducting principal component analyses using varimax rotation on the items for the three dimensions. The results demonstrate that the social variables are part of a single factor, substantiating that they relate to a common dimension (see Appendix 4 in the online supplemental material). Reliability of the social scale was also validated with a Cronbach's α score of 0.72. Principal component analyses were also used to make sure that our proxies for economy and centre-periphery dimensions did not correlate with our social scale. The results, available in Appendix 4 in the online supplemental material, confirm that the two proxies do not load into a single factor with the social dimension.Footnote7 Therefore, we believe to be further justified in using these questions and scales for the ideological dimensions in our analysis. For more details on the questions that were used to construct these three ideological dimensions, see Appendix 1 in the online supplemental material.

All statistical models use robust standard errors based on a probability weight that aims to correct sample representation with respect to age, gender, and level of education in each region. To isolate the influence of our ideological dimensions, a series of control variables were added to the regression models. To be specific, we control for the respondents’ classic sociodemographics: age, gender, and education. Furthermore, we categorized respondents according to their region: Flanders or Wallonia; the survey was not fielded in the Brussels Capital Region. Since some respondents in the sample did not primarily speak Dutch in Flanders (8 percent) or French in Wallonia (9 percent), we also control for the language most often used with the family in the regression models.

Results

We first consider unidimensional ideological self-placement in order to gauge the general differences between voters in Flanders and Wallonia. shows descriptive statistics broken down by Flemish and Walloon respondents. Respondents were asked to place themselves on an ideological spectrum ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 was the farleft and 10 was the farright. We then rescaled this variable from 0 to 1. On first glance, it seems that there is a noticeable difference between the two language groups in terms of ideological self-placement. While Flemings place themselves on average slightly to the right of centre, Walloons place themselves not too far left from the centre. We compare these means with the use a difference in means test, this gap is found to be statistically significant. This descriptive finding seems to support commonly held expectations about political attitudes in both regions. It is also a larger gap than what is found in Canada, another linguistically divided country, where the difference between Francophone Quebec and the other Anglophone provinces is not statistically significant.

Table 1. Ideological Self-Placement in Flanders and Wallonia.

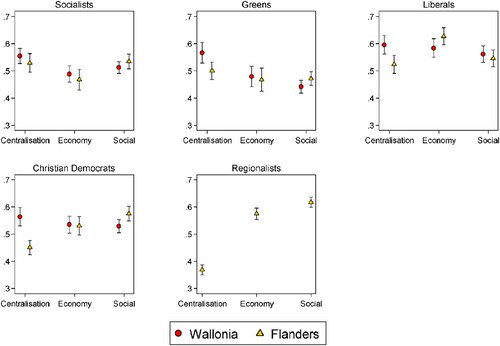

However, while ideological self-placement does provide a general idea of where voters position themselves on a simplified left-right continuum, it relies on individuals’ self-perceptions as well as condenses all issues over a single dimension. For these reasons, we unpack ideology and break it down into the three dimensions to highlight divergences in Flanders and Wallonia: centralization, economic liberalism and social conservatism scales. shows voters’ mean positioning on these three scales. As a reminder, the centralization dimension ranges from 0 to 1 in terms of increasing preferences for power to lie at the centre, rather than in the periphery (region). The economy dimension also ranges from 0 to 1 in terms of increasing freedom that companies should have. Finally, the social dimension ranges from 0 to 1 and is an index in terms of increasing social conservatism. On average, it seems that very little separates Flemings from Walloons. Contrary to what could be expected from , it seems that both regions have similar opinions regarding the economy dimension, even if the difference is almost statistically different to the p < 0.05 level. The social dimension distinguishes voters a bit more, as Flemish voters are on average more conservative than their Walloon counterparts. The main point of divergence lies with the issue of centralization. However, it seems that the differences are in line with what is commonly thought to be the case with individuals from the two communities: those in Flanders would like more power devolved to their region, while those in Wallonia would be more centre-oriented. But what about the partisan divisions?

Table 2. Three-Dimensional Ideology in Flanders and Wallonia (N in Parentheses).

presents predicted positioning on all three dimensions according to region and party family. As can be observed in this chart, in most cases, voters within party families do not have drastically different ideological positions across regions. For instance, in the Socialist family, voters of sp.a and PS position themselves similarly on all three dimensions. While on average Flemish socialists prefer regional powers and are more socially conservative, these differences are not statistically significant. The same pattern can be observed for supporters of the Green parties, Groen and Ecolo voters. The story changes in the cases of Liberal and Christian Democrat voters, however. With regard to centralization, Open VLD voters are less willing to support federal powers than MR voters in the Liberal family. Likewise, within the Christian Democrat family, CD&V voters clearly prefer powers to lie within the regions, while cdH voters prefer these powers to lie with the federal government. The Flemish Christian Democrats are also on average more socially conservative than cdH voters. While this difference is not statistically significant to p < 0.05, it comes close of passing this threshold. Interestingly, the Liberal family is the only one where the Walloon voters are on average slightly more socially conservative than their Flemish counterparts, even though the difference is again not statistically different. Finally, as could be expected, the regionalist N-VA is the party where voters are the least supportive of centralization.

Figure 1. Graphical Representation of Voters’ Ideological Positioning. Note: Confidence intervals are at the 84% level following Macgregor-Fors and Payton (Citation2013). Confidence intervals of 84% are used in the figure, since a classic 95% confidence interval is computed against a baseline of zero and should not be compared to another mean. For instance, overlapping 95% confidence intervals may not necessarily mean that a different is not significant. Macgregor-Fors and Payton (Citation2013) demonstrate that when comparing two values against each other, an 84% confidence interval is the equivalent of a 95% confidence interval.

Overall, our findings suggest that the major ideological divide among Belgian voters is along centralization. Though Dutch-speaking parties are relatively close to French-speaking ones with regard to the other two dimensions, the linguistic division is much less pronounced than what was first hypothesized and voters fall more in line according to ideology. Ultimately, our findings support conclusions from the language group and partisan mean comparisons of Deschouwer and colleagues (Citation2017) as well as Sinardet and colleagues (Citation2017). Yet, while the similarities and differences along ideological dimensions are worthwhile, it is, in our view, essential to know whether these factors determine vote choice in a similar manner across the linguistic divide.

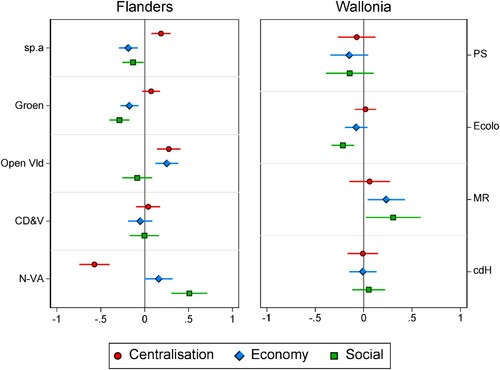

In order to estimate the influence of each dimension on vote choice, we also performed multinomial regression analyses of vote choice. displays the marginal effects estimated from multinomial logistic regression analyses (for the actual marginal effect estimates, see Appendices 2 and 3 in the online supplemental material).

Figure 2. Ideological Positioning of Voters (Marginal Effects). Note: Confidence intervals are at the 95% level.

The results show how our three ideology dimensions affect vote choice for these parties. But more importantly, it further provides support to our competing hypothesis (H2): patterns are more similar within party families than across linguistic lines, as ideology behaves similarly across regions. This is especially true when looking at the effects of social conservatism and economic liberalism. For instance, supporting the free market decreases the likelihood of voting for socialist parties in both regions: by 18 percent for the sp.a and 16 percent for PS, although the result for PS is only significant at the p < 0.10 level. In both cases, positioning on the economy scale even has a slightly more negative effect than social conservatism on voting for these parties. However, while right-leaning voters are less likely to vote for sp.a, the effect was not significant for PS. Interestingly enough, while being in favour for the free market decreases the probability of voting for Groen (by 17 percent in Flanders), social conservatism has an even stronger negative effect on green vote in both regions (22 and 29 percent for Wallonia and Flanders, respectively), suggesting that while some Green supporters may be less likely to support the free market, they are on average more likely to vote based on their stance on social conservatism.

Where regions differ, however, is in the Liberal family. For both Open VLD and MR, supporting economic liberalism increases the probability of voting for them over others by 25 percent in both cases. However, while MR also benefits from support from socially conservative voters (a 32 percent increase in vote likelihood), positioning on this dimension does not seem to affect vote for Open VLD. The case of Christian Democrat parties is also interesting. For both CD&V and cdH, positioning on any of the ideology dimensions does not seem to increase or decrease the likelihood of voting for these parties. Finally, as could be expected, supporting the free market increases the likelihood of voting for the Flemish N-VA by 15 percent (although just at the p < 0.10 level) while being a social conservative increases it by 50 percent, suggesting many N-VA voters align with this party much more on the basis of social issues than economic ones.

One striking difference between regions lies with the role of centralization. Indeed, positioning on this dimension had no effect on voting in Wallonia. However, centralization had an effect in distinguishing party vote in Flanders, as this issue is more salient to many voters. While supporters of more regional powers are more likely to vote for the regionalist N-VA, preferring more powers in the hands of the federal government statistically increases the likelihood of voting for sp.a, and Open VLD. In the case of Groen and CD&V, centralization does not have a statistically significant influence on voting for these parties. Although these results suggest that the centralization issue was especially important for Flemish voters, as it is systematically mobilized in election campaigns by the N-VA, they also indicate that it would likely not be a barrier for the voter unification of the four other party families.

In terms of the control variables, marginal effects based on the multinomial models (in Appendices 2 and 3 in the online supplemental material) highlighted different effects relative to linguistic region. For Flemish voters, marginal effects suggest education and gender did not substantively affect vote for any of these parties. However, younger voters were more likely to vote for Groen (14 percent increase) while older voters were more likely to vote CD&V by 14 percent. Interestingly, language was significant for only two parties, as speaking mainly Dutch with family decreased the likelihood of voting sp.a, by 13 percent but increased the likelihood of voting N-VA by 28 percent. Non-Dutch speakers were also more likely to vote Groen, although only significant at the p < 0.10 level. In the Walloon region, education affected the vote for three of the four main parties. Educated voters were less likely to vote PS by 36 percent, but more likely to vote for Ecolo and MR by 12 and 17 percent, respectively, although the results for Ecolo are only significant at the p < 0.10 level. Age only affected the vote for Ecolo; similar to Groen, the party tends to attract younger voters, with an 11 percent increase in vote probability. Women were also less likely to vote for MR than men by 10 percent, but more likely to vote for PS by 7 percent. However, French speakers did not seem to vote differently than non-Francophones in this region.

Overall, the results of our analyses indicate that Flemings and Walloons are not that ideologically dissimilar. Furthermore, votes for sibling parties are generally similarly determined by ideological dimension, rather than by regional divide. Therefore, our results lend support for the second hypothesis (H2) and undermine the first hypothesis (H1).

Discussion

Our empirical analyses revealed interesting findings. Firstly, party voters are clearly separated along linguistic lines when it comes to preferences about centralization. This is not particularly surprising, given that a regionalist party in Flanders has consistently been mobilizing this issue. Because of the N-VA’s strong issue ownership over the matter of state reform, other Flemish parties must react by either co-opting or challenging this party’s stance to stay electorally relevant. The result is that Flemish political parties become, as a whole, different from their Walloon counterparts.

However, voters aligned more along party families on social and economic dimensions, often seen as the ‘traditional’ components of political ideology. While scholarship has found that vote choice can be independent of social and economic preferences in societies with a salient ethnonationalist divide (Tilley, Garry, and Matthews Citation2019), our findings demonstrate that social and economic dimensions are, along with centralization, important predictors of vote choice in Flanders and Wallonia. Rather our results are in line with other research that has highlighted the importance of social and economic ideology in accounting for vote choice in ethnonational contexts (Rivero Citation2015).

Specifically regarding Belgium, our findings further emphasize that Belgian politics have not been completely overtaken by the (de-)centralization debate. Swenden (Citation2013) indicates that there exists convergence between the two major language communities on a variety of issues other than state reform. Billiet and colleagues (Citation2006), for their part, state that although there may be two separate cultures in the major language groups, there are still many commonalities between them that could facilitate cooperation and communication. This can be seen as potentially good news for those who believe that there is more than unites the two communities than separates them.

Still, the regionalized political structures make unifying voters a unique challenge. Decentralization, especially along ethnic lines, increases the politicization of issues, which in turn is its own challenge (Taye Citation2017). Parties from different partisan families, or even from different sides of the political spectrum, have tended to dominate their respective linguistic divide. Though two groups can share common ideological preferences, these preferences can be spun by their respective political elites in a contradictory manner (Turgeon et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, elite-citizen incongruence can obscure intergroup citizen-level similarities. Belgian parties have been disconnected, and more radical, on the centralization issue than the citizens they represent (Thijssen, Arras, and Sinardet Citation2018; Dodeigne and Niessen Citation2019). Therefore, while there might be common ideological ground, institutional and political barriers still exist.

Nevertheless, it is important to stress that citizens across the linguistic divide seem to be rather similar in political terms. Not only do they share comparable ideological preferences, the de/centralization debate may not be such a potential political divide after all. When asked how important a series of issues were for their vote choice, state reform ranked seventh out of eight in both Flanders and Wallonia (see Appendix 5 in the online supplemental material). Our results truly underscore that if there is a barrier to greater intergroup political cooperation in Belgium, it is not found at the citizen-level. Moreover, we also examined the importance attached by elites to specific issues by using the 2014 Belgian data from the Comparative Candidate Survey project (Citation2019).Footnote9 These data also demonstrate, somewhat surprisingly, that issues of state reform were rarely indicated by the candidates as the most pressing when compared to economic and social issues. Therefore, state reform might not even be that substantial of an obstacle to greater inter-regional political cooperation, even among political elites.

There has previously been a movement among prominent political scientists and other academics advocating for a single nationwide circumscription in Belgium, similar to Israel or the Netherlands (Deschouwer and Van Parijs Citation2009). Known as the PAVIA group, they advocate for federal elections to be held in a single constituency with district magnitude equal to 150 (i.e. the current number of MPs in the federal parliament). While this plan would not necessarily bring back national political parties, it may encourage greater cooperation between political parties from both sides of the linguistic divide by encouraging proposals rooted in a vision for the entire country. A federal circumscription may take different forms in practice and there indeed have been many different proposals about how to go about realizing this hypothetical scenario. Nonetheless, the findings of this paper may be of some use to those still wondering if Dutch-speakers and French-speakers have grown too far apart to make the idea of a single federal circumscription actually workable.

Yet, it is important to note that a potential (re-)unification of political parties would most likely not see the end of regionalist politics. While regionalized political institutions in Belgium tend to politicize issues along regional lines (Murphy Citation1993), we recognize that ideological distance is only one potential hurdle that sibling parties would have to face. Furthermore, if the separate party system has meant that regionalist parties – except for the N-VA in recent years – have generally struggled (Deschouwer Citation2009), the formation of national parties would provide opportunities for regionalist parties, especially on the Francophone side. Nevertheless, we believe that the relationship between ideology and electoral support across an ethnoregional divide to be a topic of great importance, for Belgium as well as other divided societies.

Finally, our results might be of interest for other divided societies with divided partisan systems. For Bosnia or a future unified Cyprus, the possibility of ideology overcoming ethnic divides is attainable. Fiji is another example where the ‘de-ethnicizing’ of the electoral system allowed for parties to bridge the social divide (Fraenkel Citation2015; Larson Citation2014). As evidence from the Belgian example shows, this is potential for partisan systems to overcome the exacerbation of societal divisions caused by separate partisan systems.

Online_supplementary_material.docx

Download MS Word (22 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 There are also German-speaking parties, who stand for elected office in the Parliament of the German-Speaking Community.

2 Designed and supervised by the PartiRep team, the survey was carried out in two (pre and post-election) waves in both Flanders and Wallonia using geographically stratified sampling (in terms of population size) according to the Belgian National Registry. The respondents were questioned on their political attitudes and voting choices in the federal, regional and European elections, which were administered simultaneously on May 25th, 2014.

3 There are also far-right parties, the Dutch-speaking Vlaams Belang (VB) and the French-speaking Front National, that are generally not very successful in elections. However, in the recent 2019 federal and regional elections, the VB had an important surge in votes; making them the second party in terms of vote share in both the Federal and Flemish legislatures. Though it would have been interesting to explore the determinants of vote choice for the VB in the current study, the dataset only includes 21 respondents who indicated having had voted for VB. As for the far-left, the Workers’ Party of Belgium (PVDA/PTB) functions as a single party and fielded in 2014 a common list in all 11 constituencies. While also traditionally not very popular in elections, the party was relatively successful, especially in Brussels and Wallonia, in the recent 2018 provincial and local elections.

4 There are examples of, active and defunct, Walloon regionalist parties; for instance: Rassemblement wallon, Front pour l'Indépendance de la Wallonie, Rassemblement populaire wallon, and the irredentist Rassemblement Wallonie-France. As for the Démocrate Fédéraliste Indépendant party (DéFI; formerly known as FDF), it has traditionally been more of an ethnonationalist party focused on the interests and rights of Francophones in in Brussels and its periphery (in Flemish territory).

5 This technique has been shown to be preferable to gauge ideological positioning than self-reported questions (Treier and Hillygus Citation2009).

6 We recognize that these questions form more of a social diversity acceptability scale rather than represent the complete dimension regarding social values. This follows the logic of Gauvin and colleagues (Citation2016).

7 Although economy and centre-periphery do load on their own factor with an eigenvalue very close to 1, a reliability analysis shows a Cronbach’s α score of 0.06; this is well under any sufficient score and supports our expectations that these two items are not part of the same dimension as well.

8 Using Canadian Election Study data from 2015, a difference in means test using weighted data reveals that Quebecers hold an average of 0.48 on the left-right scale compared to 0.50 for the rest of Canada, with a p-value of 0.076 (n = 1,243).

9 The question for the ‘Most important political problem’ in the Comparative Candidate Survey for Belgium was open-ended. We therefore coded the candidates’ responses into the following categories: State reform, economy, social, environment, Europe, and other.

References

- Anderson, L. 2016. “Ethnofederalism and the Management of Ethnic Conflict: Assessing the Alternatives.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 46: 1–24.

- André, A., and S. Depauw. 2015. “A Divided Nation? The 2014 Belgian Federal Elections.” West European Politics 38: 228–237.

- Billiet, J. 2011. “Flanders and Wallonia, Right Versus Left: Is This Real?” In Right-wing Flanders, Left-Wing Wallonia? Is This so? If so, why? And is it a Problem?, edited by B. De wever, 11–36. Brussels: Re-Bel Initiative.

- Billiet, J., B. Maddens, and A.-P. Frognier. 2006. “Does Belgium (Still) Exist? Differences in Political Culture Between Flemings and Walloons.” West European Politics 29: 912–932.

- Bilodeau, A., L. Turgeon, and E. Karakoç. 2012. “Small Worlds of Diversity: Views Toward Immigration and Racial Minorities in Canadian Provinces.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 45: 579–605.

- Bischof, D., and M. Wagner. 2020. “What Makes Parties Adapt to Voter Preferences? The Role of Party Organization, Goals and Ideology.” British Journal of Political Science 50: 391–401.

- Blais, A., R. Nadeau, E. Gidengil, and N. Nevitte. 2001. “The Formation of Party Preferences: Testing the Proximity and Directional Models.” European Journal of Political Research 40: 81–91.

- Carty, R. K. 2015. “Brokerage Parties, Brokerage Politics.” In Parties and Party Systems: Structure and Context, edited by R. Johnston and C. Sharman, 13–29. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- CCS. 2019. Comparative Candidates Survey Module II – 2013–2018 [Dataset - Cumulative File]. Lausanne: FORS.

- Cornell, S. E. 2002. “Autonomy as a Source of Conflict: Caucasian Conflicts in Theoretical Perspective.” World Politics 54: 245–276.

- Dandoy, R. 2015. “The Electoral Performance of the Belgian Green Parties in 2014.” Environmental Politics 24: 326–331.

- Deschouwer, K. 2002. “Falling Apart Together. The Changing Nature of Belgian Consociationalism.” Acta Politica 37: 68–85.

- Deschouwer, K. 2009. “The Rise and Fall of the Belgian Regionalist Parties.” Regional and Federal Studies 19: 559–577.

- Deschouwer, K., P. Delwit, M. Hooghe, P. Baudewyns, and S. Walgrave. 2015. Décrypter L'électeur: Le Comportement Électoral Et Les Motivations De Vote. Leuven: Lannoo Campus.

- Deschouwer, K., J.-B. Pilet, and E. Van Haute. 2017. “Party Families in a Split Party System.” In Mind the Gap. Political Participation and Representation in Belgium, edited by K. Deschouwer, 91–112. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Deschouwer, K., and M. Reuchamps. 2013. “The Belgian Federation at a Crossroad.” Regional & Federal Studies 23: 261–270.

- Deschouwer, K., and P. Van Parijs. 2009. Electoral Engineering for a Stalled Federation: A Country-Wide Electoral District for Belgium's Federal Parliament. Brussels: Re-Bel Initiative.

- De Smaele, H. 2011. “How ‘Real’ Is Right-Wing Flanders.” In Right-Wing Flanders, Left-Wing Wallonia? Is This So? If So, Why? And Is It a Problem?, edited by B. De Wever, 6–10. Brussels: Re-Bel Initiative.

- De Winter, L. 1998. “Parliament and Government in Belgium: Prisoners of Partitocracy.” In Parliaments and Governments in Western Europe, edited by P. Norton, 97–122. London: Frank Cass.

- De Winter, L. 2006. “Multi-Level Party Competition and Coordination in Belgium.” In Devolution and Electoral Politics, edited by D. Hough and C. Jeffery, 76–95. Manchester: University of Manchester Press.

- De Winter, L., M. Swyngedouw, and P. Dumont. 2006. “Party System(S) and Electoral Behaviour in Belgium: From Stability to Balkanisation.” West European Politics 29: 933–956.

- De Winter, L., and W. Wolfs. 2017. “Policy Analysis in the Belgian Legislatures: The Marginal Role of a Structurally Weak Parliament in a Partitocracy with No Scientific and Political Tradition of Policy Analysis.” In Policy Analysis in Belgium, edited by M. Brans and S. Aubin, 129–150. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Dodeigne, J., and C. Niessen. 2019. “The Flemish Negative Case: Explaining the Prevalence of Regionalist Demands Without Request for an Independence Referendum.” Fédéralisme Régionalisme 19: 1–16.

- Downs, A. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper.

- Erk, J., and E. Koning. 2010. “New Structuralism and Institutional Change: Federalism between Centralization and Decentralization.” Comparative Political Studies 43: 353–378.

- Fraenkel, J. 2015. “An Analysis of Provincial, Urban and Ethnic Loyalties in Fiji's 2014 Election.” The Journal of Pacific History 50: 38–53.

- Garry, J. 2007. “Making ‘Party Identification’more Versatile: Operationalising the Concept for the Multiparty Setting.” Electoral Studies 26: 346–358.

- Garry, J. 2009. “Consociationalism and Its Critics: Evidence from the Historic Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2007.” Electoral Studies 28: 458–466.

- Garry, J., N. Matthews, and J. Wheatley. 2017. “Dimensionality of Policy Space in Consociational Northern Ireland.” Political Studies 65: 493–511.

- Gauvin, J.-P., C. Chhim, and M. Medeiros. 2016. “Did They Mind the Gap? Voter/Party Ideological Proximity between the BQ, the NDP and Quebec Voters, 2006–2011.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 49: 289–310.

- Green, D. P., B. Palmquist, and E. Schickler. 2004. Partisan Hearts and Minds: Political Parties and the Social Identities of Voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Gunther, R., and L. Diamond. 2001. “Types and Functions of Parties.” In Political Parties and Democracy, edited by L. Diamond and R. Gunther, 3–39. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hooghe, L. 2004. “Belgium: Hollowing the Center.” In Federalism and Territorial Cleavages, edited by U. M. Amoretti and N. G. Bermeo, 55–92. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Horowitz, D. L. 1985. Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Horowitz, D. L. 1990. “Comparing Democratic Systems.” Journal of Democracy 1: 73–79.

- Huyse, L. 1981. “Political Conflict in Bicultural Belgium.” In Conflict and Coexistence in Belgium: The Dynamics of a Culturally Divided Society, edited by A. Lijphart, 107–126. Berkeley: Institute of International Studies.

- Larson, E. 2014. “Fiji's 2014 Parliamentary Election.” Electoral Studies 36: 235–239.

- Lijphart, A. 1977. Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Lipset, S. M., and S. Rokkan. 1967. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press.

- Lorwin, V. R. 1968. “Belgium: Religion, Class, and Language in National Politics.” In Political Oppositions in Western Democracies, edited by R. A. Dahl, 147–187. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Macgregor-Fors, I., and M. E. Payton. 2013. “Contrasting Diversity Values: Statistical Inferences Based on Overlapping Confidence Intervals.” PLoS One 8: e56794.

- Mair, P., and C. Mudde. 1998. “The Party Family and Its Study.” Annual Review of Political Science 1: 211–229.

- Mcgarry, J., and B. O'leary. 2009. “Must Pluri-National Federations Fail?” Ethnopolitics 8: 5–25.

- Medeiros, M. 2017. “Not Just About Quebec: Accounting for Francophones’ Attitudes Towards Canada.” French Politics 15 (2): 1–14.

- Medeiros, M., J.-P. Gauvin, and C. Chhim. 2015. “Refining Vote Choice in an Ethno-Regionalist Context: Three-Dimensional Ideological Voting in Catalonia and Quebec.” Electoral Studies 40: 14–22.

- Miley, T. J. 2013. “Blocked Articulation and Nationalist Hegemony in Catalonia.” Regional & Federal Studies 23: 7–26.

- Montpetit, É, E. Lachapelle, and S. Kiss. 2017. Does Canadian Federalism Amplify Policy Disagreements? Values, Regions and Policy Preferences. IRPP Policy Paper.

- Murphy, A. B. 1993. “Linguistic Regionalism and the Social Construction of Space in Belgium.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 104: 49–64.

- Reilly, B. 2006. “Political Engineering and Party Politics in Conflict-Prone Societies.” Democratization 13: 811–827.

- Rivero, G. 2015. “Heterogeneous Preferences in Multidimensional Spatial Voting Models: Ideology and Nationalism in Spain.” Electoral Studies 40: 136–145.

- Sinardet, D. 2010. “From Consociational Consciousness to Majoritarian Myth: Consociational Democracy, Multi-Level Politics and the Belgian Case of Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde.” Acta Politica 45: 346–369.

- Sinardet, D., L. De Winter, J. Dodeigne, and M. Reuchamps. 2017. “Language Identity and Voting.” In Mind the Gap. Political Participation and Representation in Belgium, edited by K. Deschouwer, 113–131. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Swenden, W. 2013. “Conclusion: The Future of Belgian Federalism—Between Reform and Swansong?” Regional & Federal Studies 23: 369–382.

- Swenden, W., and M. T. Jans. 2006. “‘Will It Stay or Will It Go?’Federalism and the Sustainability of Belgium.” West European Politics 29: 877–894.

- Tabachnick, B. G., and L. S. Fidell. 1996. Using Multivariate Statistics. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers.

- Taye, B. A. 2017. “Ethnic Federalism and Conflict in Ethiopia.” African Journal on Conflict Resolution 17: 41–66.

- Thijssen, P., S. Arras, and D. Sinardet. 2018. “Federalism and Solidarity in Belgium: Insights from Public Opinion.” In Identities, Trust, and Cohesion in Federal Systems: Public Perspectives, edited by J. Jedwab and J. Kincaid, 85–114. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Tilley, J., J. Garry, and N. Matthews. 2019. “The Evolution of Party Policy and Cleavage Voting Under Power-Sharing in Northern Ireland.” Government and Opposition, 1–19. Online first. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2019.20.

- Treier, S., and D. S. Hillygus. 2009. “The Nature of Political Ideology in the Contemporary Electorate.” Public Opinion Quarterly 73: 679–703.

- Turgeon, L., A. Bilodeau, S. E. White, and A. Henderson. 2019. “A Tale of Two Liberalisms? Attitudes Toward Minority Religious Symbols in Quebec and Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 52: 247–265.

- Van Haute, E., and K. Deschouwer. 2018. “Federal Reform and the Quality of Representation in Belgium.” West European Politics 41: 683–702.

- Van haute, E., and J.-B. Pilet. 2006. “Regionalist Parties in Belgium (Vu, Rw, Fdf): Victims of Their Own Success?” Regional & Federal Studies 16: 297–313.

- Vasilopoulou, S. 2018. Far Right Parties and Euroscepticism: Patterns of Opposition. London: ECPR Press.

- Westwood, S. J., S. Iyengar, S. Walgrave, R. Leonisio, L. Miller, and O. Strijbis. 2018. “The Tie That Divides: Cross-National Evidence of the Primacy of Partyism.” European Journal of Political Research 57: 333–354.

- Wheatley, J., C. Carman, F. Mendez, and J. Mitchell. 2014. “The Dimensionality of the Scottish Political Space: Results from an Experiment on the 2011 Holyrood Elections.” Party Politics 20: 864–878.