ABSTRACT

Why did the territorial conflict between the governments of Catalonia and Spain escalate to the point of extreme institutional disruption in October 2017? The present article explains this crisis – a declaration of independence followed by the imposition of direct rule – as the outcome of an Escalation of Commitment behaviour. By examining the iterative relationship between both governments, the article shows that they were trapped in a failing course of action, unable to withdraw from their early political decisions. Despite facing increasingly negative outcomes from their choices, both sides had already invested too much political capital to quit. Expectations and self-justification attitudes account for the escalation behaviour, together with a radicalized decision environment. The findings have broader implications for the study of nationalist politics: they show that the commitment to early decisions mediated by the existence of strong political incentives against compromise may lead to the escalation of territorial conflicts.

Introduction

At around 3:30 pm on 27th October 2017, the Catalan parliament declared the independence of the region while, in response, an hour later the Spanish senate passed a resolution to impose direct rule on Catalonia from Madrid. During that day, thousands of people were switching between TV channels, from one scenario to the other, following both debates with evident tension and anxiety. The predicted ‘train crash’ between the parties in dispute had finally arrived. This episode was the culmination of a political process which began several years ago, when a growing secessionist feeling in the Spanish Autonomous Community of Catalonia triggered a progressive escalation of the pre-existing territorial conflict. By performing a process-tracing analysis, the question that this article answers is the following: why did the conflict between both governments escalate to the point of extreme institutional disruption?

We already know that in advanced multinational democracies the centre-periphery cleavage profoundly influences political competition (ROKKAN and URWIN Citation1983) and a nationalist culture generates disputes around symbols and power between the majority and the minority groups (NORMAN Citation2006; GAGNON, LECOURS, and NOOTENS Citation2011). Nevertheless, a liberal-democratic political culture and the existence of inclusive institutions mediate the expression of polarized attitudes, these key elements being central to avoiding ethnic violence and war (HECHTER Citation2000; SNYDER Citation2000).

Nationalist disputes between elected governments in advanced multinational countries are usually settled through liberal-democratic means, such as the cases of Scotland or Québec show. Although these places have not been free from contention and instability (KEATING Citation1996; BASTA Citation2017; LECOURS Citation2020), the institutional disruption in contemporary Spain largely surpasses the situation in Canada or the UK. Therefore, the Spanish case is neither an example of ethnic violence nor a paradigm of smooth conflict resolution. It represents a relatively new kind of crisis concerning nationalist and ethnic conflicts in multinational democracies. Drawing from the Catalan case, this article contributes to this broader literature on nationalist and territorial crises in Western countries.

The specific literature on the Catalan bid for independence is still growing (KRAUS and VERGÉS Citation2017). Most authors have mainly focused on the secessionist camp, depicting the pro-independence movement either as a top-down phenomenon fuelled by political elites (BARRIO and RODRÍGUEZ-TERUEL Citation2017; COLOMER Citation2017) or as a bottom-up reaction to the failure of national accommodation of Catalonia within Spain (MUÑOZ and GUINJOAN Citation2013; SERRANO Citation2015; DELLA PORTA, O'CONNOR, and PORTOS Citation2019).

By contrast, the literature on counter-secessionism is scarcer. Scholars point to the central government’s institutional malpractices and an excessive legalist conception of democracy (SÁNCHEZ-CUENCA Citation2018; FISHMAN Citation2019), to an ideological vision of Spain as a ‘single and indivisible nation of equal citizens’ (BROWN SWAN and CETRÀ Citation2020) or to a vote-seeking calculation strategy by prime minister Mariano Rajoy (CETRÀ and HARVEY Citation2019). The problem with all these accounts is twofold: firstly, none of them specifically examine the mechanisms that led to the 2017 crisis. Secondly, they try to account for the behaviour of either the secessionist camp or the central government, without fully developing a more comprehensive approach. We cannot understand secessionist strategies without considering the reaction of the state, and vice versa (MURO and GRIFFITHS Citation2020). The present article fills these gaps in the literature by taking an all-encompassing approach through the exploration of the iterative relationship between the governments of Catalonia and Spain amid the 2012–2017 territorial crisis.

Beyond this case study, the article also contributes to theory-building by applying an original framework to the analysis of territorial politics. Nationalist conflicts have mainly been explained through the perspective of ethnicity and identity (RABUSHKA and SHEPSLE Citation1972; HOROWITZ Citation1985; HALE Citation2008), divergent interests around the distribution of power, status or resources (HECHTER Citation2000; PAVKOVIC and RADAN Citation2007), party politics (TURSAN Citation2003; ALONSO Citation2012) and the role of ideas and its impact on mass mobilization (GIULIANO Citation2011; LOIZIDES Citation2015). Conversely, behavioural economics, rational choice and game theory are approaches scarcely applied to the study of nationalism.

Instead, this article uses the Escalation of Commitment (EoC) theories (BROCKNER Citation1992; STAW Citation1976, 1997). These accounts stem from the disciplines of economy and sociology, and they have been hardly applied to political science. This fact represents a significant innovation in the field. The EoC works on patterns of behaviour in which a decision-maker continues to follow a particular course of action despite facing increasingly negative outcomes from it (STAW Citation1976). At some point, the decision-maker has invested too much capital – here, political capital – to quit. As both the theoretical and the empirical sections will show, the governments of Catalonia and Spain were trapped in a failing course of action, unable to withdraw from their early political decisions. External pressures, political expectations and some self-justifying attitudes prevented both governments from changing their behaviour, although it was quite clear that they were not attaining their goals.

This theoretical model can be highly useful for policymakers and scholars of territorial politics: it offers a new perspective for the understanding of why and how nationalist conflicts escalate. An example of it is the current bid for a second independence referendum in Scotland, now vehemently opposed by Westminster. There exists a reasonable probability to witness a scenario of escalation of commitment behaviour that resembles the Catalan experience – although not necessarily by reaching a point of extreme institutional disruption. Both the Scottish and the British governments are committed to conflicting goals, facing strong political incentives not to compromise. As this example suggests, both the theoretical and the empirical insights of the present article contribute to a better knowledge of a topic which is highly relevant for the democratic stability and the territorial integrity of existing plural states.

This article is organised as follows: firstly, it provides a descriptive account of the Catalan independence ‘process’ from 2012 to 2017. After that, the theoretical framework is outlined. The empirical section is deployed afterwards: several pieces of evidence are provided through a thick narrative of the events being studied, thus linking one explanatory mechanism to another. The last section offers a summary and gives the main conclusions of the research.

The Catalan ‘process’: An overview (2012-2017)

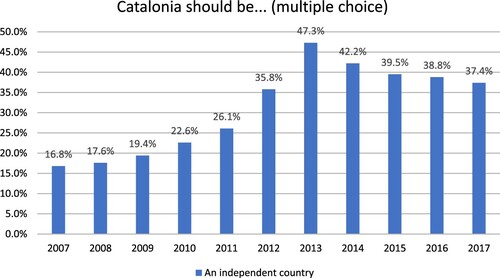

In 2006, the Catalan people approved a new statute of autonomy by referendum, which was previously agreed both in the Catalan and Spanish parliaments. Among other things, the document recognized Catalonia as a nation within Spain. In reaction, the Popular Party, then out of government at the national level, led a state-wide campaign of opposition to the statute and challenged the text in the courts (BASTA Citation2017). The sentence arrived four years later, in 2010, declaring the statute of autonomy partly unconstitutional. The recognition of Catalonia’s nationhood was nullified. In that context, the popular support for independence grew progressively from 25% in 2010 to more than 40% of the population in 2012. displays this data. A massive secessionist rally on 11th September 2012 in Barcelona is, for most commentators, the starting point of the political process under study.

At that time, and coinciding with a deep economic crisis, the Catalan ruling party, Convergència i Unió (CiU), promised a new fiscal agreement that would enhance the economic sovereignty of Catalonia and would prevent more cuts in social expenditure. However, the central government eventually refused to grant a new fiscal framework to Catalonia in September 2012. This decision triggered increasing secessionist mobilization in the streets (RICO and LIÑEIRA Citation2014). At that point, the Catalan prime minister Artur Mas led a major shift in the historically moderate CiU party by putting Catalonia’s ‘right to decide’ at the forefront. He called for a snap election and promised to promote a consultation about the political future of the region, including the independence option.

Despite CiU losing 12 seats, the traditionally secessionist party (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, ERC) obtained 11 more MP’s and a pro-sovereignty majority could be formed. The Catalan greens (ICV) and the far-left pro-independence Candidatures d’Unitat Popular (CUP) also supported a referendum about the future of the region (MARTÍ Citation2013). In April 2014, a delegation from the Catalan parliament made a formal request to the Spanish congress for the powers to hold a legal referendum in Catalonia, as in the Scottish case (LIÑEIRA and CETRÀ Citation2015). However, an overwhelming majority of Spanish MP, including the two major parties (the conservative Popular Party and the centre-left Socialist Party), rejected the proposal.

As a response, in September 2014 the Catalan parliament passed its own law to hold a non-binding vote on the future of the region, expected for November 2014. Rajoy’s government immediately challenged the law in the constitutional court, which automatically suspended it. Nevertheless, the Catalan president Artur Mas decided to go ahead with the poll under another legal precept, turning the consultation into a ‘participatory process’ organised by volunteers. Up to 2.3 million people voted (37% turnout), 80.7% of them supporting full independence (1.9 million) and 10% advocating for a state within Spain – some sort of far-reaching devolution. The November 2014 vote formed the basis of a criminal indictment against prime minister Mas and two other members of the regional cabinet.

Despite the poll being presented as a secessionist success, it had previously been framed as non-binding, and therefore it did not give a political mandate for independence. Due to the opposition of the PP central government to an official and binding referendum, prime minister Mas announced another snap election for September 2015 as a ‘substitute for the referendum that the Spanish government impedes’. That election was framed as ‘plebiscitary’ by the pro-independence parties, meaning that if they won a majority of votes, they would declare independence in 18 months after having built ‘state structures’. CiU/CDC and ERC formed an electoral coalition, Junts pel Sí (Together for Yes, JxS), and the radical small party CUP run separately but joined a shared secessionist platform.

Nevertheless, the results were not as clear as expected: the pro-independence parties obtained a majority of seats but fell short of the desired 50% of votes (MARTÍ and CETRÀ Citation2016; ORRIOLS and RODON Citation2016). After some discussions in the secessionist camp regarding the ideological profile of Artur Mas, vetoed by the radical left party CUP, Carles Puigdemont was elected new prime minister in January 2016. The difficulties of achieving unilateral independence, as well as the need for larger political majorities, led Puigdemont to come back to the idea of holding a referendum. The difference with regards to the 2014 participatory process would be that, this time, the vote would offer a mandate for independence if ‘Yes’ won.

Held on the 1st October 2017, the vote was previously suspended by the constitutional court and vehemently opposed by the Spanish government. Some political liberties were restricted in the run-up to the poll, and the leaders of the two main pro-independence civil organisations were imprisoned under charges of sedition. Rajoy’s cabinet tried to prevent the referendum by force, sending the police. The images of police brutality travelled around the world and deepened the crisis by offering Catalan nationalists a new myth of resistance that allowed them to go further in the escalation of the conflict (LÓPEZ and SANJAUME-CALVET Citation2020). By the end of the day, many people had managed to vote, and the Catalan government was able to launch official, although approximate, results: 43% turnout (2.3 million people), 90.2% in favour of independence (CETRÀ, CASANAS-ADAM, and TÀRREGA Citation2018).

Two days later, a general strike paralyzed the region and the Spanish king, at night, gave a controversial address pledging to protect non-secessionist Catalans from their own government. The initial plan of the secessionist leaders was to declare independence 48 hours following the referendum, but Puigdemont froze the decision and requested international mediation from the EU and third countries such as Switzerland, which never materialized. In private, a few intermediaries between both governments tried to prevent the final institutional clash, i.e. the declaration of independence on the Catalan side and the imposition of direct rule – through activation of article 155 of the constitution – by the Spanish government. They were close to reaching an agreement on the convocation of regional elections in exchange for preserving the Catalan self-government. Nevertheless, in the end, a political solution was not possible, and on 27 October 2017 the escalation of the conflict reached its peak. After that day, Catalan self-rule was temporarily abolished, and the secessionist leaders were either imprisoned or fled Spain to avoid the state’s repression.

Trapped in a failing course of action

The development of the Catalan bid for independence is a clear example of an Escalation of Commitment (EoC) behaviour. First postulated by Barry M. Staw in an influential article (Citation1976), EoC theories explain a pattern of conduct in which a decision-maker continues to follow a particular course of action despite facing increasingly negative outcomes from it. As there is a high level of uncertainty surrounding the attainment of a particular goal, the decision-maker hopes that by adding (i.e. escalating) more resources to his or her organisation’s course of action the objectives will eventually be achieved. Step by step, the total investment increases over time and thus the costs of withdrawing increase too – it involves the compounding of losses over time; leading to a situation of entrapment (STAW Citation1997).

A classic example in economics is a firm that decides to allocate money in one of the company’s operations. The initial feedback is negative, but the manager decides to allocate extra money to the activity, hoping that more investment will bring the goal closer. The second feedback is also negative. Now the costs of withdrawing are higher, but the uncertainty remains, so there is a third allocation of money, and so on. Eventually, the costs of withdrawing are too high to de-escalate, trapping the firm into a failing course of action (BROCKNER Citation1992). In politics, this framework has been applied to International Relations: the Vietnam war is the most famous example (STAW Citation1997; RICE Citation2010, 223–235). In that conflict, the US became trapped after allocating plenty of money, soldiers and national pride into it. At some point, despite receiving terrible feedback from the frontlines, the American government had invested too much to quit.

The processes of escalation behaviour in territorial politics, however, are mainly addressed from the perspective of the outbidding theories (RABUSHKA and SHEPSLE Citation1972; HOROWITZ Citation1985; CHANDRA Citation2005). According to this approach, territorial conflicts escalate because competing nationalist parties outbid each other in their group’s defence to be competitive in the electoral market. As we will see later, this has happened in Spain. Nevertheless, not all multinational democracies with a strong ethnocultural cleavage always fall into this kind of party competition, let alone a situation of extreme institutional disruption (COACKLEY Citation2008; ZUBER Citation2013). Even in Spain, although the territorial cleavage has always been salient, it is only recently that the country has experienced a major territorial crisis. There are other aspects – such as the motivation of the actors beyond party politics – which the outbidding models fail to include. Therefore, the EoC theory tackles these kinds of crises from a new perspective, offering a more comprehensive approach, which can be more suitable to explain escalation behaviours in nationalist conflicts.

Departing from this conceptualization, I hold that the political investments of both the Catalan and the Spanish governments in their respective courses of action progressively increased, escalating the conflict to a point in which they were trapped, unable to withdraw. This situation reached its peak in October 2017, when the Catalan parliament declared independence and the Spanish senate imposed direct rule from Madrid. According to the literature, there are two main explanations for an actor to fall into an Escalation of Commitment behaviour: expectations and self-justification. Regarding the former, decision-makers do not know for sure that the goal will not be attained, so there is always a marginal probability that extra investment will bring the objective closer (O'REILLY and CALDWELL Citation1981; NORTHCRAFT and WOLF Citation1984). Concerning the latter, the self-justifying tendency of people often leads them to be unwilling to admit that the previous allocation of resources was a mistake (BROCKNER Citation1992).

Phenomena such as secessionist crises are complex and multicausal, so it is almost impossible to consider all the nuances. In this case, I treat the two governments in dispute as units of analysis: they are the decision-makers in my model. Of course, this assumption is not free from problematic aspects, mainly because they are not unitary or homogenous actors, and because they faced strong external pressures. I include these elements in my model.

Moreover, the pattern of escalation is highly contingent. As the theory shows, decision-makers face the choice to allocate further resources in their course of action step by step and by observing the feedback of previous investments, meaning that there is a remarkable degree of uncertainty surrounding the attainment of the goal. This choice environment makes it very difficult to devise a clear-cut plan to reach the objectives. As the ‘Catalan process’ shows, both governments improvised and considered the reaction of the other party before moving forward in their escalation of commitment behaviour.

Under this theoretical framework, I will show that the goal of the Catalan government was to bring Mariano Rajoy to the negotiation table to reach some sort of self-determination agreement, ideally an independence referendum. The Spanish government, on the other hand, was committed to stopping the secessionist plan and took a non-negotiation policy concerning the nationalist demands. Expectations, self-justification attitudes and external pressures explain the inability of the actors to withdraw from their course of action, a pattern of behaviour which ultimately led to the extreme institutional disruption of October 2017.

Regarding the expectations, both governments though that the chances to attain their goals – independence, on the one side; and deterrence of secessionist activities, on the other – would increase by escalating the political investments to their respective course of action. Political investment or political capital here refers to promises, commitments, policy programmes (such as nationalist foreign relations by both governments), institutional propaganda and mass mobilization tactics.

Self-justification attitudes mean that both governments thought that they were doing the right thing. Mariano Rajoy was defending the Spanish constitutional order – he ‘could not and did not want to’ compromise (BROWN SWAN and CETRÀ Citation2020) – and the Catalan cabinet was being responsive to its base: as democrats, the pro-independence politicians could not do anything but follow the will of the people who voted for the implementation of a secessionist programme. Therefore, both were unwilling to accept that their previous political investments were in vain, or even a mistake.

Finally, governments are formed from political parties, which means that policy goals are mixed with office and vote-seeking calculations. In this regard, they faced bottom-up pressures from their rank and file and from the attitudes of their voters (vertical pressures), as well as from competing parties, following a pattern of outbidding that has been outlined before (horizontal pressures). I hold that the environment in which the decisions makers operate, facing these external pressures, is as crucial as the expectations and the self-justification elements for the escalation of commitment behaviour. Both parties had strong political incentives not to compromise.

The next section sets out the empirical analysis by systematically testing these claims. The method used is process-tracing (BENNETT and CHECKEL Citation2015), and I rely on secondary sources of data to support my argument. In this regard, I present evidence to support each claim, affirming its relevance as a necessary cause for the outcome to occur. The limitation of this method for a multicausal phenomenon is that it is almost impossible to measure the exact impact of every element included in the theoretical model. However, and precisely because it is a complex phenomenon hardly measurable, this qualitative approach based on a thick narration of political facts is the most suited for our purposes.

The escalation behaviour under examination

A process of escalation behaviour begins when the main actors take the initial decisions, that will later be progressively reinforced. After Mariano Rajoy and Artur Mas disagreed about whether granting or not a new fiscal framework for Catalonia in 2012, the prime minister of this region made a significant turn from the moderate stance of his party and promised to deliver a consultation on independence. His alliance with the secessionist party ERC marked the beginning of the Catalan cabinet’s course of action. Conversely, the Spanish government quickly framed the proposal as both illegal and undesirable, and from then onwards Mariano Rajoy uncompromisingly repeated the same idea: he ‘cannot and does not want to’ allow a referendum on independence (CETRÀ and HARVEY Citation2019). Both actors invested all their political capital in these initial commitments, which ultimately led to the institutional clash of October 2017.

Expectations and Self-justification in the ‘Catalan Process’

Josep Maria Colomer summarized the dynamics of the escalation in an article published in 2017:

Each of the Catalan demands […] and the subsequent mobilisations raised high expectations. Yet all clashed with Spanish resilience […]. Every step in the process of escalation was followed by considerable frustration, which was responded to with increasing radicalisation. (p.3)

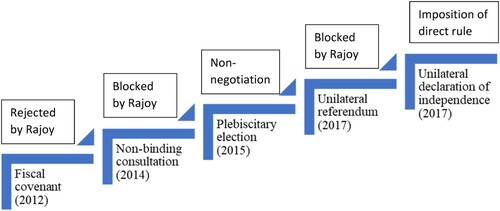

Figure 2. Summary of the process of conflict escalation. A policy of rejection and non-negotiation followed each step made by the Catalan authorities; and vice versa.

During all this time, the Catalan cabinet always thinks that the central government will yield at some point and will offer some kind of dialogue […]. The analysis of Mas and Homs always follows the same pattern: they hope that after each act of defiance conducted by Catalan secessionism something will move in Moncloa [Madrid]. Something that provides a way out before allowing the escalation to reach a disaster point. Nevertheless, this movement never arrives. (2018)

On his part, his successor, Carles Puigdemont, did not utter these explicit statements but acted by following the same rationale. After allegedly winning the 2017 referendum, he did not declare independence as intended, but he made the last call for dialogue ‘before the situation deteriorates still further’ (Jones Citation2017). Both governments were close to reaching an agreement over the organisation of ordinary regional elections, a peculiar way to ‘implement the mandate’ of creating a sovereign republic. Puigdemont’s minister of education, Clara Ponsatí, summarized in a well-known statement this strategy of escalating the demands to put pressure on the Spanish government: ‘We were playing poker and bluffing’ (RTVE Citation2018). Facing Rajoy’s intransigence, the last card in the hands of the regional cabinet was the failed declaration of independence of 27th October 2017, a move that has much to do with external pressures – we will deal with this fact later on.

Conversely, the non-negotiation stance of the Spanish government took three main policy paths; all of them aimed at deterring the secessionists from their activities. Firstly, Rajoy challenged in court every step taken by the Catalan officials, hoping that the rule of law would impede Mas and Puigdemont from further defying the state. Committing illegal actions not only would hinder the Catalan efforts towards secession, but it would threaten the rebel politicians with several criminal charges. However, Mas, Puigdemont and his ministers pushed forward with their plans. The 2017 Annual Report of the Spanish constitutional court recognized that 41% of the litigations regarding the 17 Autonomous Communities had only one source of conflict: Catalonia. The judicialisation of the conflict was the main feature of Rajoy’s behaviour during the crisis (SÁNCHEZ-CUENCA Citation2018).

Secondly, his minister of interior created the so-called ‘patriotic police’, aimed at undermining the pro-independence support amongst the population by crafting scandals against secessionist politicians. This activity was known as ‘operation Catalonia’, a manoeuvre recognized and criticised by the very same Spanish parliament (Congreso de los Diputados Citation2017). Finally, in 2016 Rajoy launched ‘operation dialogue’, intended to address the Catalan crisis by talking about everything except the core issue at stake: self-determination. He hoped that a ‘rainfall of millions’ (Sastre Citation2017) for the Catalan economy and infrastructures would put an end to the secessionist movement. Although a negotiation around financial issues was the goal of the Catalan government back in 2012, four years later the regional cabinet had already invested too much in its pro-independence course of action to accept anything but a referendum on secession. Neither the expectations of the Catalan government about forcing a scenario of negotiation nor those of the Spanish cabinet surrounding the deterrence of the pro-independence activities were met.

Apart from these expectations, the self-justification element was also crucial to understand the progressive investment of political capital in this failing course of action. Both actors thought that, despite facing increasingly adverse outcomes from their decisions, they were doing the right thing. On the Spanish side, the constitution enshrines the indivisible unity of the country. Both the legal and the ideational elements of this – Spain as a ‘single and indivisible nation of equal citizens’ (BROWN SWAN and CETRÀ Citation2020) – led Mariano Rajoy to justify his intransigence towards the Catalan demands. Again, he ‘could not and did not want to’ compromise with Mas and Puigdemont (Ibid). On the Catalan side, the pro-independence politicians vindicated the democratic character of their bid by stressing the political majorities supporting a referendum on self-determination. As democrats, they could not do anything but follow the will of the people – even if this meant taking an illegal path.

Moreover, the unwillingness to recognize that the prior allocation of resources was in vain became explicit within the Catalan camp in two different points of time. Firstly, the 2015 plebiscitary election was called under the promise to declare unilateral independence in 18 months if the secessionist parties won more than 50% of the vote. They reached 48% of the ballots. Even the leader of the far-left pro-independence party CUP stated during the election night that ‘the declaration of independence was linked to the plebiscite. As we have not won, there will not be any declaration’ (GONZÁLEZ Citation2015).Footnote2 Nevertheless, they finally maintained their initial plan and promised to achieve independence in 18 months, a decision that would dramatically escalate the conflict and entrapped, even more, the Catalan government in its failing course of action. Prime minister Artur Mas recognized that it was a mistake, yet four years after the elections were held (Vera Citation2019).Footnote3

Secondly, the Catalan authorities framed the 2017 referendum as politically binding and thus promised to declare independence 48 hours after the poll. Despite Carles Puigdemont and his ministers attempting to avoid it, they were slaves to their previous promise, and facing Rajoy’s intransigence they felt forced to declare independence. The regional authorities did not want to appear before the public to explain that the conditions to enforce the new Catalan republic were not present, as they acknowledged in private (Ara Citation2018).Footnote4 Therefore, in conclusion, expectations and self-justification attitudes led to the progressive escalation of the conflict for both sides. Nevertheless, these mechanisms cannot be fully understood without considering the political environment in which the decisions were taken. The next subsection tackles the external pressures on the Catalan and Spanish governments to deepen in their respective political commitments.

The decision-making environment: strong external pressures

Expectations and self-justification attitudes largely explain the behaviour of the decision-makers regarding the investment of their political capital in the failing courses of action. Nonetheless, we cannot overlook the environment in which both governments were taking the decisions, particularly regarding the external pressures they received to increase their political bids. Formed from political parties, both governments had electoral incentives to be responsive to their file and rank and voters (vertical pressures). Moreover, the structure of political competition in a context of extreme polarization also pushed the parties to appear firmly committed to their goals, avoiding either the emergence or the consolidation of competing parties that could outbid them on the centre-periphery dimension (horizontal pressures).

Regarding the former, extreme polarization led to the ethnicisation of the electoral market (ZUBER and SZÖCSIK Citation2019): the voters were deeply divided and realigned in nationalist terms. For instance, in the run-up to the 2017 referendum, 49.8% of Spaniards stated that the government should not allow this poll, but these numbers were strikingly higher for the electorate of the PP (88.5%) and C’s (77.2%), its parliamentary partner (Cadena SER Citation2017). Conversely, 73.6% of Catalans agreed to call a consultation on independence, but only 50.3% of them supported an illegal poll. This 50.3% of the population, however, was clustered around the secessionist coalition government (90.2%), and its parliamentary partner, CUP (91.4%). Their electorates massively supported the illegal bid for independence (CEO Citation2017). To put it in other words: both governments were being responsive to their electoral base. They had different and contradictory democratic mandates (LÓPEZ and SANJAUME-CALVET Citation2020).

Apart from the voters, another vertical source of external pressure stemmed from the file and rank of their parties and the broad political movement. In Catalonia, it is particularly noteworthy the role played by two pro-independence civic organisations: the Assemblea Nacional Catalana (Catalan National Assembly, ANC) and Òmnium Cultural (OC). In 2015, the ANC had over 80.000 members, while OC had in 2018 over 125.000 (EFE Citation2015). Both associations organised massive annual rallies for the independence of Catalonia, gathering between 1 and 2 million people on average. While the Catalan government was in charge of the institutional dimension of secessionist politics, ANC and OC fuelled an impressive grass-roots movement. Under slogans such as ‘we are in a hurry [to achieve independence]’, they exerted a great deal of pressure on Catalan politicians. A well-known episode of this goes back in 2014, when the non-binding consultation was suspended in courts. In the annual pro-independence demonstration, the president of the ANC demanded prime minister Artur Mas ‘put the ballot boxes’ (Vilaweb Citation2014).

The behaviour of the rank and file of the ruling parties was also crucial to understand the decision-making environment of the Catalan cabinet. Particularly mayors and low-rank officers, in touch with activists and real voters, demanded more commitment to their own parties. For instance, on the 26th October 2017, when prime minister Carles Puigdemont suggested the possibility to call for regional elections instead of declaring independence, two relevant mayors and MP’s of his own party announced their resignation as a protest (La Vanguardia Citation2017a).

In the case of Mariano Rajoy, he had already been mocked as too mild and nicknamed maricomplejines – meaning that he was too concerned about appearing as overtly tough on many issues – by the most radical factions of his own party and the conservative media. As early as 2014, after the non-binding independence vote, he had been suffering pressures to take a hard-line approach towards secessionism (GARCIA Citation2018). He even told his political rivals about the will of his rank and file to abolish the Catalan self-government (El Periódico Citation2017; La Vanguardia Citation2019). His own predecessor in the party, former prime minister José María Aznar, publicly defected from Rajoy’s policies in December 2016, and pushed him to intervene the Catalan institutions from the very beginning of the crisis (Catalunyapress Citation2012). Aznar still acts as a political and moral guide for many conservatives. This decision-making environment partly explains the different behaviour of Mariano Rajoy in the referendums of 2014 and 2017: while both consultations were declared illegal, the former was tolerated by the Spanish government, yet the police fiercely repressed the latter. In 2017, the Spanish authorities were also at the top of their escalation of commitment behaviour, strongly pressed to avoid the poll at all costs.

Moreover, a dynamic of outbidding competition accounts for the horizontal pressures that the governments received (BARRIO and RODRÍGUEZ-TERUEL Citation2017). In the Catalan side, there was a process of outbidding both within the cabinet – among the parties that formed the ruling coalition – and outside it – among the ruling coalition and their parliamentary partner, CUP. Regarding the former, none of the two ruling parties wanted to be blamed for the failure of the independence movement and tried to appear as more committed to secession than its partner. Because of that, political officers from different parties lied to each other about the situation of their departments, as this audiotape from an ERC high-rank official shows: ‘In October we will not have the capacity, we do not have customs control, neither a bank. The situation is not ripe enough. I am terrified that if we explain the things as they really are […] these people [CDC] will use them to blame Junqueras [ERC’s leader] for not preparing the country for the declaration of independence’ (La Vanguardia Citation2017b).Footnote5 On the other hand, the small radical party CUP acted as kingmaker as the ruling coalition fell short of a majority (MARTÍ and CETRÀ Citation2016). With disobedience as its creed, this party repeatedly pushed the government to increase its bid towards unilateral independence, threatening CDC and ERC with withdrawing its parliamentary support.

In the Spanish side, the PP government depended on a parliamentary agreement with Ciudadanos (Citizens, C’s), a committed anti-secessionist party that was born in Catalonia as representative of the Spanish-speaking population (RODRÍGUEZ-TERUEL and BARRIO Citation2016). As the Catalan crisis progressively escalated, C’s tried to outbid the government on the centre-periphery dimension. Apart from C’s, the conservatives were facing the emergence of Vox, a former faction of the Popular Party that in 2014 fell short of achieving representation in the European parliament. Vox accused Rajoy of being too mild regarding secessionism, and although it did not become a real threat until 2018, at that point it already added pressure on Rajoy’s course of action. Vox is currently the third group in the Spanish parliament and places itself on the radical right (FERREIRA Citation2019), promising the suppression of the regional level of government and threatening the pro-independence parties with jail and legal bans.

Summary and conclusions

By considering the iterative relationship between the governments of Catalonia and Spain, this article has explained why the territorial conflict escalated until a point of no return in October 2017. The theoretical framework, based on the Escalation of Commitment behaviour, represents a significant innovation in the field of political science. I have shown that the Spanish and the Catalan governments were trapped in a failing course of action, unable to withdraw from their early political decisions: despite facing increasingly negative outcomes from their choices, they had already invested too much political capital to quit. While Mariano Rajoy was committed to a policy of non-negotiation due to Spanish unity being a principle enshrined in law, the Catalan cabinet repeatedly promised to deliver some sort of self-determination arrangement for Catalonia.

The progressive escalation of the conflict is explained by the expectations and the self-justification attitudes of the decision-makers. They thought that by increasing the bid for the independence, or by a deepening of the deterrence strategy in the case of Rajoy, their goals would be brought closer. The belief that they were doing the right thing, and the unwillingness to admit that their prior decisions were in vain – or even a mistake; also influenced the direction of their political choices.

Finally, I have also considered the decision-making environment of the Catalan and Spanish authorities, without which it would be impossible to understand why the governments took these decisions and not others. I have shown that both governments were operating under strong external pressures. On the one hand, they faced the preferences of their voters and their file and rank (vertical pressures). On the other hand, they felt threatened by competing parties, following a pattern of outbidding competition that has been outlined elsewhere (horizontal pressures). As governments are formed from political parties, policy goals are mixed with office and vote-seeking calculations, which played a relevant role in the phenomenon under study.

These findings represent significant progress in the understanding of the ‘Catalan process’ for independence, as well as of nationalist conflicts in advanced multinational democracies more broadly. Beyond the explanation of this empirical case, the article makes a theoretical contribution by identifying the mechanisms that lead to the escalation of conflicts in territorial politics. These insights can be highly useful to identify patterns of conduct that can trigger extreme institutional disruption. For instance, contemporary Scotland is facing a bid for a second independence referendum, now vehemently opposed by Westminster. There exists a reasonable probability to witness a scenario that resembles the Catalan experience – although not necessarily by reaching the same level of upheaval. Both the Scottish and the British governments are committed to opposite courses of action, and they have already invested in divergent policy decisions that could eventually clash.

To conclude, what Catalonia shows is that the commitment to early decisions mediated by the existence of strong political incentives against compromise may lead to the escalation of territorial conflicts. Moreover, an all-encompassing approach that examines both the secessionist and the counter-secessionist conducts offers a more comprehensive explanation to understand secessionist phenomena, as opposed to the literature focused on either sub-state mobilization or majority nationalism alone. This article can thus give policymakers and scholars a new framework to understand and explain nationalist behaviour and conflict in advanced democracies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Translated from Catalan: ‘La negociació real amb l’estat arribarà quan Catalunya hagi acumulat força suficient per arribar a construir el seu propi estat […]. No volem un referèndum per guanyar-lo i tirar pel dret, sinó per guanyar-lo i seure a negociar’.

2 Translated from Catalan: ‘la declaració unilateral anava lligada al plebiscit. No s’ha guanyat, no hi ha proclamació’.

3 During an interview, prime minister Mas stated the following: ‘yes, it was a mistake. Setting deadlines put a barrier that […] ends up turning against you like a boomerang’

4 Oriol Soler, campaign manager of Junts pel Sí: ‘it is obvious that the government neither has any kind of international complicity nor possesses any state structure that allows a possible declaration of independence to have practical consequences’

5 Translated from Catalan: ‘El mes d’octubre no hi ha capacitat, ni tenim control de duanes, ni un banc. La cosa no pinta, està molt verda. Això qualsevol que té dos dits de front ho sap. Ara bé, a mi em fa pànic que si transmetem les coses com són en realitat […] aquests no l’acabin autoritzant perquè diguin que Junqueras no ha preparat el país perquè el 2 d’octubre declarem la independència’

References

- ACN. 2014. Mas: ‘després del 9-N, Rajoy haurà d’entendre que cal negociar’. Available at https://www.naciodigital.cat/noticia/75585/mas/despres/9-n/rajoy/haura/entendre/cal/negociar (accessed 14 May 2020).

- ALONSO, S. 2012. Challenging the State: Devolution and the Battle for Partisan Credibility: A Comparison of Belgium, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ara. 2018. set dies d’octubre: les 140 hores que van canviar Catalunya. Available at https://www.ara.cat/dossier/Set-doctubre-hores-canviar-Catalunya_0_2005599556.html (accessed 14 May 2020).

- BARRIO, A., and J. RODRÍGUEZ-TERUEL. 2017. “Reducing the gap Between Leaders and Voters? Elite Polarization, Outbidding Competition, and the Rise of Secessionism in Catalonia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (10): 1776–1794.

- BASTA, K. 2017. “The State Between Minority and Majority Nationalism: Decentralization, Symbolic Recognition, and Secessionist Crises in Spain and Canada.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 48 (1): 51–75.

- BENNETT, A., and J. T. CHECKEL. 2015. Process Tracing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- BROCKNER, J. 1992. “The Escalation of Commitment to a Failing Course of Action: Toward Theoretical Progress.” Academy of Management Review 17 (1): 39–61.

- BROWN SWAN, C., and D. CETRÀ. 2020. “Why Stay Together? State Nationalism and Justifications for State Unity in Spain and the UK.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 26 (1): 46–65.

- Cadena SER. 2017. una ajustada mayoría prefiere una salida dialogada pero intervendría Cataluña si se salta la ley. Available at https://cadenaser.com/ser/2017/04/03/politica/1491242416_479479.html (accessed 14 May 2020).

- Catalunyapress. 2012. Aznar ve ‘golpista’ la actitud de Mas y dice que Rajoy debe salvaguardar más que nunca que la ley se cumpla en Cataluña. Available at https://www.catalunyapress.es/texto-diario/mostrar/602205/aznar-ve-golpista-actitud-dice-rajoy-debe-salvaguardar-nunca-ley-cumpla-catalunya (accessed 14 May 2020).

- CEO. 2017. baròmetre d'opinió política. 1ª onada 2017. Available at http://upceo.ceo.gencat.cat/wsceop/6168/Dossier_de_premsa_-_850.pdf (accessed 14 May 2020).

- CETRÀ, D., E. CASANAS-ADAM, and M. TÀRREGA. 2018. “The 2017 Catalan Independence Referendum: A Symposium.” Scottish Affairs 27 (1): 126–143.

- CETRÀ, D., and M. HARVEY. 2019. “Explaining Accommodation and Resistance to Demands for Independence Referendums in the UK and Spain.” Nations and Nationalism 25 (2): 607–629.

- CHANDRA, K. 2005. “Ethnic Parties and Democratic Stability.” Perspectives on Politics 3 (2): 235–252.

- COACKLEY, J. 2008. “Ethnic Competition and the Logic of Party System Transformation.” European Journal of Political Research 47 (6): 766–793.

- COLOMER, J. M. 2017. “The Venturous bid for the Independence of Catalonia.” Nationalities Papers 45 (5): 950–967.

- Congreso de los Diputados. 2017. el Pleno aprueba el dictamen de la Comisión de Investigación que concluye que hubo uso ‘partidista’ de efectivos y medios de Interior bajo el mandato de Fernández Díaz. Available at http://www.congreso.es/portal/page/portal/Congreso/Congreso/SalaPrensa/NotPre?_piref73_7706063_73_1337373_1337373.next_page=/wc/detalleNotaSalaPrensa&idNotaSalaPrensa=25366&anyo=2017&mes=9&pagina=1&mostrarvolver=S&movil=null (accessed 14 May 2020).

- DELLA PORTA, D., F. O'CONNOR, and M. PORTOS. 2019. “Protest Cycles and Referendums for Independence. Closed Opportunities and the Path of Radicalization in Catalonia.” Revista Internacional de Sociología 77 (4): 1–14.

- EFE. 2015. la ANC supera los 40.000 afiliados y cuenta con otros 40.000 colaboradores. Available at https://web.archive.org/web/20150120172531/http://www.abc.es/agencias/noticia.asp?noticia=1760561 (accessed 14 May 2020).

- El Periódico. 2017. Mariano Rajoy reconoce a Núria Marín las presiones que recibe por el 1-O. Available at https://www.elperiodico.com/es/politica/20170914/nuria-marin-reclama-privado-mariano-rajoy-evite-escalada-tension-6285486 (accessed 14 May 2020).

- FERREIRA, C. 2019. “Vox como representante de la derecha radical en España: un estudio sobre su ideología.” Revista Española de Ciencia Política 51: 73–98.

- FISHMAN, R. 2019. “Does National Conflict Within Spain Undermine or Reinforce the Argument?” In Democratic Pratice: Origins of Iberian Divide in Political Inclusion, edited by R. FISHMAN, 153–193. New York: Oxford University Press.

- GAGNON, A., A. LECOURS, and G. NOOTENS. 2011. Contemporary Majority Nationalism. Montréal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- GARCIA, L. 2018. El Naufragio. Barcelona: Ediciones Península.

- GIULIANO, E. 2011. Constructing Grievance: Ethnic Nationalism in Russia's Republics. New York: Cornell University Press.

- GONZÁLEZ, A. 2015. la CUP admet la derrota en el plebiscit i rebutja Mas. Available at https://cat.elpais.com/cat/2015/09/27/catalunya/1443368794_097466.html (accessed 14 May 2020).

- HALE, H. 2008. The Foundations of Ethnic Politics: Separatism of States and Nations in Eurasia and the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- HECHTER, M. 2000. Containing nationalism. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

- HOROWITZ, D. 1985. Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Jones, S. 2017. Catalan president Carles Puigdemont ignores Madrid's ultimatum. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/16/catalan-president-carles-puigdemont-ignores-madrids-ultimatum (accessed 14 May 2020).

- KEATING, M. 1996. Nations against the state: The new politics of nationalism in Quebec, Catalonia and Scotland. London: Springer.

- KRAUS, P. A., and J. VERGÉS. 2017. The Catalan Process: Sovereignty, Self-Determination and Democracy in the Twenty-First Century. Barcelona: Institut d'Estudis de l'Autogovern.

- La Vanguardia. 2017a. el PDeCAT sancionará a los diputados que dijeron que dimitirían por las elecciones. Available at https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20171027/432385563913/pdecat-diputados-dimision-elecciones-puigdemont.html (accessed 14 May 2020).

- La Vanguardia. 2017b. el sumari del 20-S revela la manca de recursos per a la independència. Available at https://www.lavanguardia.com/encatala/20171028/432398614064/el-sumari-del-20-s-revela-la-manca-de-recursos-per-a-la-independencia.html (accessed 14 May 2020).

- La Vanguardia. 2019. el octubre catalán en 20 fragmentos del libro de Sánchez. Available at https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20190221/46601371446/octubre-catalan-2017-libro-pedro-sanchez-20-fragmentos-1o-155-mariano-rajoy-manual-resistencia.html (accessed 14 May 2020).

- LECOURS, A. 2020. “The two Québec Independence Referendums: Political Strategies and International Relations.” In Strategies of Secession and Counter-Secession, edited by R. D. GRIFFITHS, and D. MURO, 143–160. London: ECPR Press.

- LIÑEIRA, R., and D. CETRÀ. 2015. “The Independence Case in Comparative Perspective.” The Political Quarterly 86 (2): 257–264.

- LOIZIDES, N. 2015. The Politics of Majority Nationalism: Framing Peace, Stalemates, and Crises. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- LÓPEZ, J., and M. SANJAUME-CALVET. 2020. The Political Use of de facto Referendums of Independence The Case of Catalonia. Representation, pp. 1-19.

- MARTÍ, D. 2013. “The 2012 Catalan Election: the First Step Towards Independence?” Regional & Federal Studies 23 (4): 507–516.

- MARTÍ, D., and D. CETRÀ. 2016. “The 2015 Catalan Election: a de Facto Referendum on Independence?” Regional & Federal Studies 26 (1): 107–119.

- MUÑOZ, J., and M. GUINJOAN. 2013. “Accounting for Internal Variation in Nationalist Mobilization: Unofficial Referendums for Independence in C Atalonia (2009-11).” Nations and Nationalism 19 (1): 44–67.

- MURO, D., and R. D. GRIFFITHS. 2020. Strategies of Secession and Counter-Secession. London: ECPR Press.

- NORMAN, W. 2006. Negotiating Nationalism: Nation-Building, Federalism, and Secession in the Multinational State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- NORTHCRAFT, G. B., and G. WOLF. 1984. “Dollars, Sense, and Sunk Costs: A Life Cycle Model of Resource Allocation Decisions.” Academy of Management Review 9 (2): 225–234.

- O'REILLY, C.A, and D. F. CALDWELL. 1981. “The Commitment and job Tenure of new Employees: Some Evidence of Postdecisional Justification.” Administrative Science Quarterly 26 (4): 597–616.

- ORRIOLS, L., and T. RODON. 2016. “The 2015 Catalan Election: The Independence bid at the Polls.” South European Society and Politics 21 (3): 359–381.

- PAVKOVIC, A., and P. RADAN. 2007. Creating New States: Theory and Practice of Secession. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- RABUSHKA, A., and K. SHEPSLE. 1972. Politics in Plural Societies. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

- RICE, M. T. 2010. “Escalation of Commitment Behaviour: a Critical, Prescriptive Historiography.” (Unpublished PhD Thesis).

- RICO, G., and R. LIÑEIRA. 2014. “Bringing Secessionism Into the Mainstream: The 2012 Regional Election in Catalonia.” South European Society and Politics 19 (2): 257–280.

- RODRÍGUEZ-TERUEL, J., and A. BARRIO. 2016. “Going National: Ciudadanos from Catalonia to Spain.” South European Society and Politics 21 (4): 587–607.

- ROKKAN, S., and D. W. URWIN. 1983. Economy, Territory, Identity: Politics of West European Peripheries. London: Sage Publications.

- RTVE. 2018. Clara Ponsatí, desde Escocia: ‘estábamos jugando al póquer y jugabamos de farol”. Available at https://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/noticias-24-horas/clara-ponsati-desde-escocia-estabamos-jugando-poquer-jugabamos-farol/4630607/ (Accessed 14 May 2020).

- SÁNCHEZ-CUENCA, I. 2018. La confusión nacional: la democracia española ante la crisis catalana. Madrid: Catarata.

- Sastre, D. 2017. Rajoy promete una lluvia de millones a Cataluña para ‘sellar las grietas’ del ‘procés’. Available at https://www.elmundo.es/cataluna/2017/03/28/58da2965e2704e91108b4593.html (Accessed 14 May 2020).

- SERRANO, I. 2015. “Catalonia: a Failure of Accommodation?” In Catalonia in Spain and Europe: is There a way to Independence?, edited by K. J. NAGEL, and S. RIXEN, 97–113. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG.

- SNYDER, J. 2000. From Voting to Violence. New York: WW Norton.

- STAW, B. M. 1976. “Knee-deep in the big Muddy: A Study of Escalating Commitment to a Chosen Course of Action.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 16 (1): 27–44.

- STAW, B. M. 1997. The Escalation Of Commitment: An Update And Appraisal.

- TURSAN, H. 2003. “Introduction: Ethnoregionalist Parties as Ethnic Entrepreneurs.” In Regionalist Parties in Western Europe, edited by Lieven De Winter and Huri Tursan, 19–34. London: Routledge.

- Vera, E. 2019. Artur Mas: ‘la reacció a la sentència no ha de ser la solució fàcil de convocar eleccions’. Available at https://www.ara.cat/politica/Artur-Mas-sentencia-eleccions-esther-vera_0_2265973480.html (accessed 14 May 2020).

- Vicens, L. 2016. Mas avisa els empresaris que caldrà una “mobilització permanent” per garantir el referèndum. Available at https://www.ara.cat/politica/Mas-empresaris-mobilitzacio-permanent-referendum_0_1695430563.html (accessed 14 May 2020).

- Vilaweb. 2014. Carme Forcadell: ‘president, posi les urnes’. Available at https://www.vilaweb.cat/noticies/carme-forcadell-president-posi-les-urnes/ (accessed 14 May 2020).

- ZUBER, C. I. 2013. “Beyond Outbidding? Ethnic Party Strategies in Serbia.” Party Politics 19 (5): 758–777.

- ZUBER, C. I., and E. SZÖCSIK. 2019. “The Second Edition of the EPAC Expert Survey on Ethnonationalism in Party Competition-Testing for Validity and Reliability.” Regional & Federal Studies 29 (1): 91–113.