?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Adequately financed branches contribute to the integration of regional interests into statewide parties. Yet, we have limited knowledge about the determinants of branches’ varying income levels in federal contexts. To address this shortage, this article elucidates why branches receive donations from citizens and businesses to different degrees. I hypothesise that party competition at the state level, the difference in regional economic performance and parties’ historical legacies can account for the level of branches’ donation revenue. Analysing German statewide party branches’ income from 2009 to 2017, this study finds support for the facilitating impact of state and federal electoral contests on donation levels. Regional economic disparities, by contrast, only marginally affect donation revenues. At the same time, parties’ path-dependent developments help explain asymmetries in average revenue levels between western and eastern branches. The study’s findings suggest that intense regional party competition contributes to branches’ financial independence within the statewide party organisation.

Introduction

Federal theory suggests that political parties running in multiple states integrate regional interests into federal politics (Bednar Citation2009; Filippov, Shvetsova, and Ordeshook Citation2004). By running party offices at the state and federal level, statewide parties incorporate regional interests into their agenda and settle conflicts between state regions internally (Detterbeck Citation2016b; Petersohn, Behnke, and Rhode Citation2015, 631; Verge and Gómez Citation2012). In this process, branches serve as an important channel through which regional interests are represented in the statewide party. However, for this integrative channel to work, regional branches require sufficient resources to run regional party offices properly and express regional interests in the decision-making process within the statewide party. And yet, while research has already investigated the role of regional parties in federal systems (Aarebrot and Saglie Citation2013; Deschouwer Citation2003; Detterbeck Citation2012), we still know relatively little about the determinants of branches’ income in federal contexts. This article aims to address this understudied aspect of party organisations in federal systems. The German federal system provides a good study environment in which to investigate the determinants of branch revenues. Because of Germany’s symmetric federal design, party branches operate in similar institutional contexts, which is why institutional factors can be mostly neglected when seeking to explain differences in donation levels (cf. Freitag and Vatter Citation2008, 17).

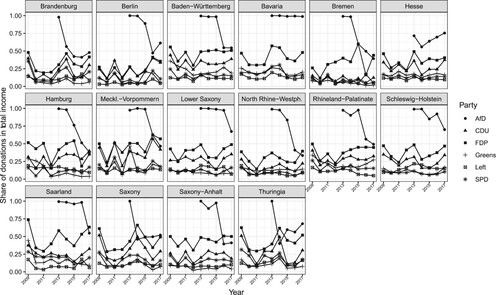

At the same time, German party branches can generate their income independently of the statewide party office. In contrast to membership dues and a large share of state subsidies, all donations made by individuals and business remain with the receiving branch and are not redistributed within the federal party organisation. Consequently, donations represent a revenue type that provides statewide party branches with additional means to run a regional infrastructure. Indeed, as shows, donations make up a considerable portion of many branches’ total revenues, yet to various degrees. First, branches of some statewide parties (AfD and FDP) appear to be more dependent on donations than others. Second, party branches’ donation incomes are, in many cases, relatively unstable over time. In light of the relative importance of donations for a large share of statewide party branches and longitudinal variation, I ask: What explains the differences in statewide party branches’ donation revenues?

To identify potential explanatory factors of branches’ donation levels, I draw on approaches in federal theory and research into party organisations. Specifically, branch donation levels may be affected by political competition both at the state and federal levels, the socio-economic environment in the respective regions, and branches’ path-dependent trajectories, meaning that historical legacies account for varying incomes. To test these accounts empirically, based on an original dataset compiling finance data from 2009 to 2017,Footnote1 I compare donation levels within and across party branches and apply multilevel negative binomial regression models to donation levels. Lastly, I discuss the empirical findings in light of the presented theoretical approaches derived from scholarship on federal systems and party organisation.

The results indicate that competition-related factors boost branches’ donation income, while economic conditions only marginally play into revenue levels. Both state and federal elections increase branches’ donation level, where higher fragmentation of state party systems reinforces the concentration of donations in electoral years. Moreover, parties’ path-dependent trajectories account for partially asymmetrically integrated statewide organisations in western and eastern states. Overall, the results imply that, despite the role of regional economic interests in German federal politics (Jeffery Citation1999, Citation2003), branches in states showing comparatively poor economic performance do not generally generate higher donation revenue than their counterparts in more affluent environments. Instead, political competition raises branches’ donation incomes, expanding their budget for running party offices and financing electoral campaigns.

Party financing in federal environments

Multilevel party competition and the financing of statewide party branches

Research into party politics at the regional level has argued that the form and extent of regional competition is an important determinant of how regional parties organise themselves and compete with each other (Deschouwer Citation2003). Since citizens have increasingly given up their long-term ties to a single political party (Flanagan and Dalton Citation1984) and instead became more likely to vote for different parties between elections, it can be assumed that competition has become an important driver of regional party politics. As Detterbeck and Renzsch (Citation2004, 88) state, the weakening of enduring citizen-voter linkages has been replaced by conflicts over territorial interests and corresponding institutional arrangements. Because of this process, territorial interests, rather than political colours binding state actors together, might increasingly shape politics in the states, which could eventually nurture a more competitive setting at the subnational level. Party branches might exploit these local environments by running campaigns tailored to territorial issues and investing in organisational infrastructure to establish linkages with the regional electorate. In the long term, this could pay off for branches in gaining citizen support and advantages over competing branches.

From this perspective, competition should exert a significant influence on statewide party branches’ donation revenues. Specifically, there are three aspects of party competition that likely account for varying donation levels: (1) the intensity of political competition in the states, (2) whether branches hold executive office at the state and federal level, and (3) electoral campaigns.

First, the nature of party competition at the state level may influence branch revenue levels. The effect of fierce competition on the amount of funding is well known from first-past-the-post (FPTP) systems, in which candidates, commonly running on a party ticket, seek to generate as much revenue as possible for their electoral campaign. For instance, in the United Kingdom, marginal seats attract more donations to candidates than seats that will be most likely won by a candidate of the dominating party (Johnston and Pattie Citation2007; Pattie, Johnston, and Fieldhouse Citation1995). In competitive constituencies, candidates’ investment in the campaign oftentimes is a decisive factor for the election outcome. Applying this mechanism to mixed-member proportional (MPP) representation, which is widely used in German state elections, particularly fragmented state party systems may incentivise partisans to donate for their party to run an effective and elaborated campaign. As fragmented party systems are characterised by citizens voting for various smaller parties (Coleman Citation1995, 141), party supporters could be more willing to support their party with donations in order for it to gain strength vis-à-vis competing party branches and to run capital-intensive electoral campaigns that appeal to undecided voters.

There are other forms of party competition besides fragmentation. For one thing, the closeness of the previous electoral race might have implications for future elections, yet, as research into elections at the German state level shows (Müller Citation2018; Schniewind Citation2008, 199–267), there is considerable voter volatility between state elections. Moreover, the usual period between elections is five years, making it rather difficult to anticipate the closeness of the upcoming electoral race.

What is more, the coalition size in the federal parliament could also be seen as an indicator of party competition. However, a slim majority of a party coalition in a state parliament does not necessarily indicate a higher degree of competition in the next state electoral contest. For instance, two branches forming a coalition that holds a supermajority in a state parliament could aim to achieve a higher share of the vote in the next election to be no longer dependent on the coalition partner. Similarly, a minimum-winning coalition (i.e. a coalition narrowly passing the majority threshold) may consider the upcoming election highly competitive, as the incumbent parties could prefer to continue their coalition after the next election. Therefore, depending on the various state branches’ coalition preferences, the coalition majority size of state governments can lead to diverging degrees of competition among parties in the German states.

Given these considerations about the potential influence of party competition, I theorise that a low degree of party fragmentation, marked by a voter concentration to a low number of political parties, is likely to result in lower donation revenues. Vice versa, fiercer party fragmentation should lead to higher donation levels. Hence,

Hypothesis 1: The higher state party fragmentation is, the higher branches’ donation level in that state.

This theoretical claim has found support in empirical studies, showing that governing parties tend to enjoy higher incomes than opposition parties (Fink Citation2017; Lösche Citation1993). Furthermore, business donations have been found to be influenced by power status at the state level: Fink (Citation2017), analysing private and business donors’ spending patterns in the German states, showed that only corporate donors tend to give more to governing parties than to opposition parties.

Besides attracting pragmatic donations, governing state branches are likely more salient in the public and media, encouraging citizens and partisans to donate money to a branch in state government. It has been shown that rerunning candidates have a higher propensity to be reelected in elections, as officeholders usually enjoy higher media coverage and public attention than their challengers (Egner and Stoiber Citation2008; Stoiber and Egner Citation2008; Träger, Pollex, and Jacob Citation2020).

Adapting the incumbency effect to party branches’ income in the German states, one may argue that parties in government are granted more public attention, thereby becoming more relevant to business actors’ and citizens’ concerns, resulting in a higher willingness to donate money to a governing branch than to the state opposition (Lösche Citation1993, 222). Based on these two mechanisms, I derive the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: If a party branch is in government at the state level, its donation level increases.

Alternatively, branches benefit from their umbrella party’s governmental status at the federal level. Like the incumbency effect at the state level, branches whose statewide party is in federal government would gain benefits from pragmatic donations and increased public attention. In this line of argument, the incumbency effect at the state level not only pays off for the federal party but also for the branches at the subnational level. This produces two competing hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: If a statewide party is in opposition at the federal level, its branches’ donation level increases.

Hypothesis 3b: If a statewide party is in opposition at the federal level, its branches’ donation level decreases.

Conversely, in a firmly integrated statewide party organisation, regional branches and the federal office collaborate closely in federal elections, resulting in higher donation income for branches in national electoral contests. Here, branches are heavily involved in national election campaigns and seek to appeal to donors in federal races too. To test the effect of both state and federal elections, I will put the following hypotheses under empirical scrutiny:

Hypothesis 4a: In state election years, branches’ donation level increases in that state.

Hypothesis 4b: In federal election years, branches’ donation level increases.

Hypothesis 4c: The more fragmented a state party system, the higher branches’ donation levels in state election years.

In Germany, economic disparities are the most prevalent cleavage in federal politics (Jeffery Citation1999, 160). Considerable differences in states’ economic performances could result in diverging income levels. In states where the economy is comparatively strong, party branches are likely to benefit from this situation because individuals and corporations tend to harvest more financial means. As a result, more affluent citizens and enterprises may result in higher branch revenues. This produces:

H5: The higher a state’s economic performance, the higher branches’ donation revenue in that state.

Historical legacies and statewide party branches’ donation levels

Apart from competition-related and contextual approaches to statewide party branches’ financial behaviour, party branches’ trajectories may furthermore account for varying income levels. In the case of Germany, parties exhibit a firmly institutionalised structure, which partially originates in strict organisational regulations stipulated by the German Parteiengesetz (Party Law). Parties must organise in accord with the federal order, which requires well-equipped party branches employing a considerable amount of staff (Nassmacher Citation2009, 383). Even though the number of generous donations to parties has decreased over the past (Saalfeld Citation2000, 99), this funding source makes up a relevant share of parties’ revenues and is especially critical for the party on the ground, as a mediocre amount of money may contribute significantly toward the local unit’s budget (Lösche Citation1984, 39). Furthermore, since it is the local branch that is closest to members on the ground (Detterbeck and Jeffery Citation2009, 74), state branches enjoy the advantage of having the most direct access to donations.

At the same time, parties deal with institutional environments in different ways. Most importantly, the party’s historical legacy, or, in other words, “sticky” party traditions’ (Hepburn and Detterbeck Citation2013, 88), influence the development of intra-party organisational structures. In this line of argument, the institutionalisation of organisational structures during the party’s formative years shapes the organisation’s development. With respect to statewide parties, it may matter whether the organisation was initially established at the federal or state level; parties founded from top-down may remain relatively centralised, while bottom-up party institutionalisation may result in a rather decentralised organisation in the long term.

Additionally, more regionally integrated branches should appeal to individual and businesses donors considerably more than branches that do not enjoy much public support in their regional political environment. Parties legacies are thus likely to affect branches’ donation levels. There is a rich literature on the trajectory of German statewide parties, which allows formulating empirical expectations regarding diverging donation levels that can be traced back to path-dependent developments of party organisations since the beginning of the Federal Republic.

As the two dominant parties in German party politics, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Christian Democratic Party (CDU) are likely to generate a relatively high number of donations across German regions. Moreover, besides their prominent role in politics at the federal level, many branches have been part of state governments, illustrating their principal role in state politics. It can thus be expected that the two parties’ donation levels should not vary too enormously between branches.

Yet, the different sequence of establishing the two parties is likely to have affected the branches’ composition of revenue. The SPD has been categorised as a ‘unitary organisation’ (McMenamin Citation2013, 29), as the party was established first at the federal level and then founded branches in all German states. By contrast, the Christian Democrats (CDU), with its Bavarian collaboration partner the Christian Social Union (CSU), first organised in the various states and established regional organisations in the states. Contrasting with the SPD’s formative years, the CDU’s federal umbrella party was founded after establishing regional organisations in 1950. Because of this sequence, the federal party was comparatively week in the first decades of its existence. CDU chairman Helmut Kohl later strengthened the federal party’s office and its resources in the 1970s, yet the Union’s state branches have preserved their influential role in federal politics (Detterbeck Citation2012, 136).

Based on these two different trajectories at the first stages of the parties’ organisational evolution, one may expect donations to make up a higher portion of CDU branches’ income because of its regional units’ regional independence. Besides these differences, the unification process in the 1990s should have affected both parties to similar degrees. In the aftermath of integrating the eastern states into the Federal Republic, CDU and SPD were coping with the structural heterogeneity between ‘old’ and ‘new’ states.Footnote2 As Jeffery (Citation2005, 83) points out, traditional western German parties have not fully integrated into all eastern states. Nonetheless, though confronted with higher electoral volatility in the east (Mannewitz Citation2017, 231), SPD and CDU were able to gain strength in the eastern states and built up organisational structures, such as well-equipped branch offices. However, advancing a more reluctant assessment, Detterbeck (Citation2012, 136) notes that all eastern state branches are still ‘organizationally weak’. Empirically, we may thus expect the CDU’s and SPD’s eastern branches to receive fewer donations than their western counterparts.

The Free Democratic Party (FDP) has been traditionally more dependent on donations than other German parties (Lösche Citation1984, 60), both at the federal and state level. However, its trajectory shares some similarities with that of the CDU, as the organisation was first founded at the state level and later established at the federal level (Filippov, Shvetsova, and Ordeshook Citation2004, 243). Likewise, the Green Party, founded in 1980 in the (western) Federal Republic, implemented a decentralised rather than a centralised internal structure. In so doing, the party sought to establish grass-roots-oriented funding patterns to avoid power centralisation (Lösche Citation1984, 95–96). Thus, it is likely that the FDP and Green branches generate substantial donation revenue across states. Similarly to the CDU and SPD, however, western branches should exhibit higher donation levels than their eastern counterparts.

Lastly, The Left and the Alternative for Germany (AfD) are likely to exhibit significant differences in donation income levels between western and eastern branches. As Abedi (Citation2017, 458) notes, ‘[d]ifferences in western and eastern voting behaviour have their roots in the discrete identities’, which can mainly be explained by citizens’ distinct experiences in different political cultures prior to unification and lasting socio-economic disparities (Abedi Citation2017, 475). The socialist Left Party’s eastern branches continue to be more successful in electoral contests and have considerably more members than their western counterparts. In a similar vein, the far-right AfD is most successful in eastern state elections (Abedi Citation2017, 457). Therefore, the two parties’ higher electoral support may suggest that The Left and AfD generate more donations in the east, leading to financial asymmetries between western and eastern branches.

Overall, statewide parties’ historical legacies are likely to explain variance in income levels that cannot be captured by the level of competition and economic performance in the various states. summarizes the expectations on branches’ donation revenues derived from parties’ trajectories from the outset of the Federal Republic. Empirically, path-dependencies are challenging to study with conventional regression analyses, which is why the following empirical study builds on both descriptive and inferential quantitative techniques. While the effects of competition and state economy can be investigated in a regression framework, path dependencies may become apparent in systematic deviation in generated income along German parties’ distinct trajectories outlined in this section. In addition to estimating the effect sizes of competition- and economy-related factors, I shall investigate to what extent branches within statewide parties differ internally with regard to their donation levels.

Table 1. Expectations on branch income differences and empirical findings between and within German statewide parties.

Research design

Subnational research has become a popular approach to hold contextual factors relatively constant while investigating multiple subunits of a political system (Freitag and Vatter Citation2008, 17; Jacob and Pollex Citation2021). In Germany, the Party Law, including parties’ obligation to publish their incomes and expenditure, applies to all branches, facilitating the comparative analysis of income patterns.

The dependent variable of the analysis is donations received by statewide party branches per annum measured in euro. To test whether the various explanatory factors affect types of donations in different ways, I differentiate between donation revenue from citizens (i.e. individual donations) and legal bodies (i.e. corporate donations). In Germany, donations are the only income type that remains entirely with the receiving branch within the statewide party. In contrast, other sources, such as fees, mandate holder fees (‘party taxes’) and state subsidies, are at least partially redistributed based on intra-party arrangements that vary from one statewide party to the next. While it is important to note that donations to branches do not necessarily originate from donors residing in the respective state, it can be assumed that the lion’s share of donations comes from local individuals and businesses. The data is taken from the annual reports on parties’ incomes, expenditure and assets, which the parties must submit to the President of the Bundestag (Deutscher Bundestag Citationn.d.).

In the reports, state branches’ income is listed separately for revenues of the branches’ central offices (Landesgeschäftsstellen) and local units of the branch (nachgeordnete Gliederungen). As both build the party branch, the two levels’ revenue is summed up to a merged value for each state branch. The data encompasses the period from 2009 to 2017, whereby two complete electoral cycles at the federal level can be examined.Footnote3 Therefore, this period allows for testing the impact of state and federal elections and the incumbency effect in at least two government terms per state. Overall, the dataset (N = 791) encompasses the annual donation revenue of the six main statewide parties’ branches over nine years. Since the AfD was founded in 2013, data on its branches are only available for four years. To receive an overview of the income levels within the Union ‘party family’, the CSU is considered in the descriptive part of the analysis but not in the regression models because it is not a statewide party.

The empirical analysis proceeds in two steps. Firstly, to systematically shed light on differences in branches’ income levels that may point to path-dependent developments, I calculate the average income from individual and corporate donations of party branches per 1000 inhabitants between 2009 and 2017. Next, I report the extent to which each branch deviates from the average income among their statewide party’s branches. More formally, I calculate

where p is the statewide party, b a branch of a statewide party, N the number of branches per statewide party (i.e. 16 for each statewide party), and

the branch’s income divided by 1000 state inhabitants. This measure allows comparing the variance across parties as it reports the percentage deviation of each branch from the average branch income of the respective statewide party. Substantially, negative values would indicate lower, and positive values higher, income than the average branch of the statewide party. By contrast, values close to zero per cent suggest that the branch approximates the average branch income of its statewide party. I display the deviations in a heat map of German states by party to facilitate the evaluation of deviances between and within parties.

In a second step, I implement regression models to identify statistical predictors of donation levels. The independent variables of these model are operationalised with the following indicators. Firstly, the effective number of electoral parties (ENEP) measures the level of party fragmentation in the states based on all parties’ vote shares in state elections (Laakso and Taagepera Citation1979).Footnote4 I choose this measure over the elective number of parliamentary parties (ENPP), as smaller statewide parties regularly fail the 5 per cent electoral threshold but nevertheless operate in states with relatively weak electoral support, including running branch offices and electoral campaigns.

Secondly, governmental status is coded as a binary variable, indicating whether a party is in state government (1) or not (0). Another variable measures whether a party is in the opposition at the federal level (1) or not (0). Moreover, a binary variable indicates whether a state election (and thereby an election campaign) was held in the year of the observation (1) or not (0). Similarly, another binary variable is created that indicates if a federal election took place (1) or not (0). Lastly, a continuous variable takes account of the respective state’s GDP economic performance.Footnote5

I implement negative binomial regression models to estimate the association between the independent and dependent variables. This generalised linear model is preferable to linear models because of the outcome variable’s specific characteristics (i.e. donation revenue in euro). Specifically, branch revenues deviate substantially between states and parties, leading to a highly skewed distribution of the outcome variable. However, as linear models should be implemented with reasonably normally distributed data, this model specification may lead to spurious results with donation data. By contrast, negative binomial models can accommodate heavily positively skewed and overdispersed count data in its parameterisation (Hardin and Hilbe Citation2007, 200–203), which applies to the distribution of donations, a variable on a currency scale. Therefore, in line with previous analyses using financial data as an outcome variable (McMenamin Citation2019), I employ negative binomial models.

Further, the regression model takes account of the multilevel structure of the data (Gelman and Hill Citation2006). For instance, while GDP is measured at the state level, the incumbency variable refers to the branches in the states. To take account of the data’s nested structure, the model includes random effects for (1) state and (2) parties nested in states.

Results

Donation levels of statewide party branches

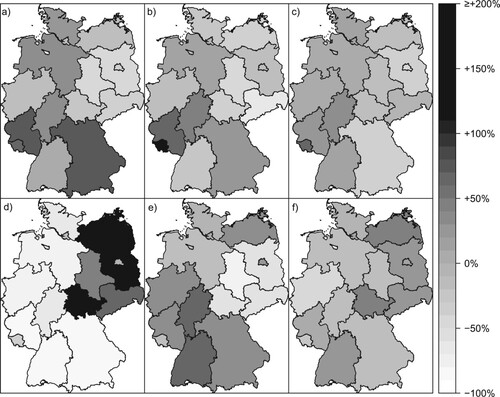

displays the deviation of each party branch from the average level of individual donations per 1000 inhabitants. Within the Union party family, the Bavarian CSU and the Rhineland-Palatinate CDU branch generate about 75 per cent more individual donations than the average CDU branch.Footnote6 Although the highest donation levels within the CDU occur in the western German states, eastern branches do not receive remarkably less income from individual donations. For instance, the eastern CDU branch of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania exhibits a similar relative donation level as the western branch of North Rhine-Westphalia.

Figure 2. Deviation of average individual donations to branches of (a) CDU, (b) SPD, (c) FDP, (d) The Left, (e) Greens and (f) AfD.

Like the CDU/CSU’s donation revenue, the SPD branches in the east receive donations levels comparable to western counterparts. The only exception is the Saxony branch, which receives almost 70 per cent less than an average SPD branch. In contrast, The Left’s individual donations mirror its asymmetric integration: All eastern branches generate remarkably more income from that source than Western branches. Even though the AfD has been the most successful in eastern state elections, western party branches, most notably in Baden-Württemberg, obtain on average the same amount of donations as their eastern counterparts. As for the share of donations in the overall income of the two German principal parties, CDU branches do not appear more reliant on donation revenue than SPD branches across states (see Figure 1 in Online Appendix).

In line with the Greens’ and FDP’s more muscular organisational strength in western states, their party branches tend to receive more individual donations in the west than in the east. However, the asymmetry tends to be more prevalent within the Green Party, which generates most of its individual donation income in southern and northern states. In contrast, the eastern Saxony-Anhalt branch receives about 70 per cent less than an average Green branch. Substantially, this branch generates only 10 euro per 1000 inhabitants, one of the lowest figures among all branches’ individual donation income. The FDP branches in the east, particularly the Saxony branch, appear to enjoy higher financial support from individual donors, suggesting that this party has appealed to private donors in the east to a greater extent than the Greens. Like AfD branches, FDP branches are the most dependent on individual donations in their overall income (see Figure 1 in Online Appendix).

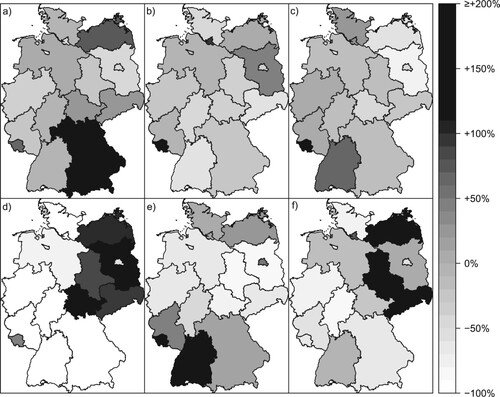

Turning to business donations, shows the deviation of each branch from the average corporate donation by statewide party. The CDU/CSU’s income from that source does not vary substantially between east and west, with the Bavarian CSU having the most corporate donations per inhabitant at its disposal. Yet, the Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania branch in eastern Germany also receives a comparatively high level of business donations per capita. This finding is somewhat surprising, as economic performance is considerably higher in the western states, most notably in Baden-Württemberg, but business actors do not support the CDU to a higher degree in that state than in others.

Figure 3. Deviation of average corporate donations to branches of (a) CDU, (b) SPD, (c) FDP, (d) The Left, (e) Greens and (f) AfD.

As the CDU has been traditionally closer to employers’ interests than the SPD, it is not surprising that SPD branches receive on average less from business donations than the CDU (see Figure 2 in Online Appendix).Footnote7 While income of this type is comparatively evenly distributed across states, the Saarland branch turns out to generate the highest income from business donations. As for The Left, once more, the eastern branches receive more than their western counterparts. However, since The Left accepts business donations only under exceptional circumstances, the level of that revenue type is close to zero. In contrast to individual donations within the statewide party, most of AfD’s eastern branches appear to receive the highest relative amount of corporate donations, where business donations of AfD branches tend to be generally low. The Greens’ and FDP’s revenue levels from corporate donations do not differ substantially between east and west.

Summarised in along with the expectations about income differences derived from party trajectories, the four ‘traditional’ parties CDU/CSU, SPD, Greens and FDP do not generally receive a higher amount of donations in the west. Instead, eastern branches of these statewide parties have been particularly successful in generating business donation and, in a few cases, even exceed their western counterparts in corporate donations per state capita. While The Left is asymmetrically integrated across the states in terms of both individual and corporate donations, the AfD, despite its better electoral performance in the east, has also been able to acquire donations from citizens in the west.

Determinants of donation levels

reports the results of the multilevel regression models. To analyse the impact of the dependent variables on overall donation levels, Models 1–3 estimate the effects of the explanatory variables on the sum of individual and corporate donations. In Model 1 (without interaction effect) and Model 2 (with interaction effect), state government participation, state elections and federal elections turn out to be statistically significant. To see whether this pattern holds for (1) a smaller sample without AfD observations and (2) individual and corporate donations separately, I refine the aggregated regression model.

Table 2. Multilevel negative binomial regression on total, individual, and corporative donations.

First, it may be that the AfD’s income patterns (that is, a considerably high share of donations in the overall income, see ) are too different from the established parties’ revenue structures. I thus test whether the results for all parties hold when dropping all AfD branches from the sample (Model 3). Besides participating in state government, all estimates retain their statistical significance, providing support for the effects identified for elections at the state and federal levels, population size and the interaction term between party fragmentation and state elections.

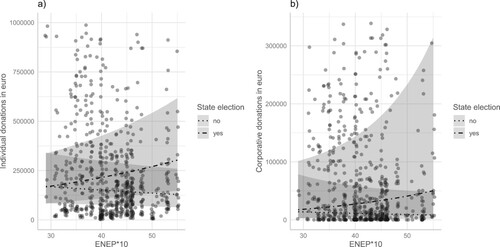

Second, the independent variables could exert different effects on individual and business donations. To test this proposition, Model 4 shows the effects on individual donations only. In this specification, state population increases individual donations the most, followed by state elections (β = 0.399) and federal elections (β = 0.283). This finding suggests that citizens tend to donate more to branches in state election years and, to a lower extent, in federal electoral contests. Compared to the other effect sizes, the negative impact of party fragmentation (ENEP) is negligible.

As Model 5 shows, a similar pattern emerges for corporate donations. Again, both state elections (β = 0.967) and federal elections (β = 0.905) exert a considerable positive effect on business donations. In contrast, recognising that GDP does not yield a significant coefficient, economic performance is negatively associated with corporate donations (β = −0.443). This somewhat surprising finding suggests that branches in states with lower economic performance tend to receive more corporate donations. While governmental status is not associated with individual donations, branches participating in state government tend to receive more business donations than branches sitting on the state legislature’s opposition benches. In contrast, if the umbrella party is in the federal opposition, that branch will generate less revenue from business donations. However, both coefficients of both federal and state government participation fail the significance test.

As for the hypothesised facilitating effect of a fragmented state party system and state elections, the interaction effect of ENEP and state election yields a positive association with both individual (β = 0.194) and corporate donations (β = 0.348). This result suggests that, as hypothesised in H4c, the higher party fragmentation, the higher branches’ donation revenues in state election years. illustrates this effect: From the state with the lowest degree of fragmentation to that with the highest, the models predict a rise for individual and corporate donations in state election years. While the confidence intervals are relatively large, branch observations in the state of Berlin and a few in Brandenburg, Bremen, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Schleswig-Holstein, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia yield higher ENEP values (see Online Appendix Figure 4). This group of states is of different population sizes and located in different regions, even though most of them in eastern Germany. This variance indicates that the interaction coefficient is likely not driven by outlying ENEP in one or a few states.

Figure 4. Predicted counts of a) individual and b) corporate donations with 95% confidence intervals (see Online Appendix for predicted counts of all donations).

Overall, the analysis suggests that competition-related variables affect the sum of individual and corporate donations. Moreover, this pattern holds for the sample without the more recently established AfD and individual and corporative donations separately.

Conclusions

What accounts for varying donation levels of German statewide party branches? This article addresses this question by deriving potential determinants of statewide party branches’ donation levels from scholarship on party organisations in federal systems. From a competition perspective, regional party competition, governmental status and electoral campaigns may influence statewide branches’ donation revenues (Hepburn and Detterbeck Citation2013; Hildebrandt and Wolf Citation2016). From an economic angle, states’ varying economic performance may similarly shape donations levels (Detterbeck and Jeffery Citation2009; Jeffery et al. Citation2014). Lastly, parties’ different historical legacies could account for persisting asymmetries in branch revenues since parties are organisations that have evolved practices and institutions over time (Hepburn and Detterbeck Citation2013).

To test these approaches empirically, this article examines German statewide party branch revenues from donations between 2009 and 2017. The empirical analysis suggests that branches’ donation levels are decisively affected by regional political competition. Elections at the state and, to a lower extent, federal level politicise both citizens and businesses to support state branches financially, providing them with additional means for running party offices and electoral campaigns. Moreover, this mobilisation effect appears to become stronger in more fragmented party systems, in which branches generate more donations in the electoral season but less in non-election years.

By contrast, states’ economic performance only matters to a low degree for branch revenue levels, indicating that the economic environment only marginally influences branch incomes. Interestingly, corporate donations to state branches tend to be higher in states with lower economic performance, even though the effect failed to be statistically significant. At first sight, this finding seems to be counterintuitive as one would expect more business donations in states with higher economic performance. McMenamin (Citation2012) explains this puzzle, arguing that businesses already participate in the policymaking process in coordinated market economies like Germany. From this perspective, businesses operating in states with comparatively weak economic performance may want to expand their influence at the state level to influence policies conducive to their enterprise. Firms in more affluent states, however, may not see the necessity to exert influence on party branches because they already consider the state economy to be competitive. Overall, the hypothesis that high economic performance increases party branches’ income in the states substantially could not be confirmed.

Therefore, the divide between poor and prosperous states in German federal politics is not reflected by branches’ donation levels. Nonetheless, as the descriptive inquiry of donation levels in the states has shown, most statewide parties exhibit asymmetrical patterns that mirror their historical trajectories. While the largest statewide parties, namely CDU and SPD, are integrated into both east and west, the Green Party and FDP tend to generate a higher income in the latter. By contrast, The Left is the most established in eastern states, which can be explained by the party’s historical strength in that region (Detterbeck Citation2016a). The far-right AfD has been remarkably capable of appealing to individual donors in all states, yet only to business donors in the east. Thus, similarly to differences in voting behaviour and political attitudes between eastern and western Germany (Abedi Citation2017; Mannewitz Citation2017), the distinct political environments also manifest themselves in their branches’ donation revenue.

Overall, the findings of this study imply that party competition at the state level is crucial for branches to generate individual and business donations. Without a competitive nature of subnational politics, branches would likely be in a financially weaker position. Simultaneously, statewide parties’ historical legacies account for asymmetric donation levels within statewide parties, most importantly, for their more robust integration in either western or eastern Germany. In sum, intense party competition at the state level appears to strengthen branches’ financial independence, which can help them formulate regional interests more confidently in decision-making processes within the statewide party.

As this article has sought to show, empirical analyses of branch revenue provide fertile ground for research into multilevel party politics. Even though the current availability of financial data on regional parties sets limits to the number of potential cases other than Germany, the trend to adopt more transparent party finance regulation in established democracies may ultimately offer additional promising data sources in the future.

Replication material

Replication material can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/97EDVS.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (176.5 KB)Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Chris Jardine, Sabine Kropp, Christoph Nguyen, Ugur Ozdemir, Greta Schenke, Noel Treffinger, Editor Louise Tillin and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on previous versions of the manuscript. All remaining errors are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 The full dataset can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FSCDPI.

2 However, as Rueschemeyer (Citation1998) remarks, it is important to note that the SPD was required to build up branches from scratch after unification, while CDU and FDP could integrate existing branches of former ‘block parties’ into their statewide party.

3 Federal elections were held in 2009, 2013 and 2017.

4 . Parties below the 5 per cent threshold were also considered for calculating the ENEP based on state election results. The ENEP values were assigned to all state branch observations in the respective legislative period.

5 The data for state GDP and inhabitants was taken from the Federal Statistical Office. A longitudinal overview of state GDP and inhabitants can be found at www.statistik-bw.de.

6 In absolute terms, both branches generate about 400 euros per 1000 inhabitants on average.

7 The average SPD branch corporate donation level is 32 euro per 1000 inhabitants, while CDU branches generate on average 120 euro per 1000 inhabitants.

References

- Aarebrot, E., and J. Saglie. 2013. “Linkage in Multi-level Party Organizations: The Role(s) of Norwegian Regional Party Branches.” Regional & Federal Studies 23 (5): 613–629. doi:10.1080/13597566.2013.806303

- Abedi, A. 2017. “We Are Not In Bonn Anymore: The Impact of German Unification on Party Systems at the Federal and Land Levels.” German Politics 26 (4): 457–479. doi:10.1080/09644008.2017.1365135

- Bednar, J. 2009. The Robust Federation. Principles of Design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coleman, S. 1995. “Dynamics in the Fragmentation of Political Party Systems.” Quality and Quantity 29 (2): 141–155. doi:10.1007/BF01101895

- Deschouwer, K. 2003. “Political Parties in Multi-Layered Systems.” European Urban and Regional Studies 10 (3): 213–226. doi:10.1177/09697764030103003

- Detterbeck, K. 2012. Multi-level Party Politics in Western Europe. Houndmills. Basingstoke: Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Detterbeck, K. 2016a. “Party Inertia Amid Federal Change? Stability and Adaptation in German Parties.” German Politics 25 (2): 265–285. doi:10.1080/09644008.2016.1164841

- Detterbeck, K. 2016b. “The Role of Party and Coalition Politics in Federal Reform.” Regional & Federal Studies 26 (5): 645–666. doi:10.1080/13597566.2016.1217845

- Detterbeck, K., and C. Jeffery. 2009. “Rediscovering the Region: Territorial Politics and Party Organizations in Germany.” In Territorial Party Politics in Western Europe, edited by W. Swenden and B. Maddens, 63–85. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Detterbeck, K., and W. Renzsch. 2004. “Regionalisierung der politischen Willensbildung: Parteien und Parteiensysteme in föderalen oder regionalisierten Staaten.” In Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2000. Föderalismus, Subsidiarität und Regionen in Europa, edited by Europäisches Zentrum für Föderalismus-Forschung Tübingen, 88–106. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Deutscher Bundestag. n.d. Fundstellenverzeichnis der Rechenschaftsberichte [online]. Accessed February 10, 2020. https://www.bundestag.de/parlament/praesidium/parteienfinanzierung/rechenschaftsberichte/rechenschaftsberichte-202446.

- Egner, B., and M. Stoiber. 2008. “A Transferable Incumbency Effect in Local Elections: Why it is Important for Parties to Hold the Mayoralty.” German Politics 17 (2): 124–139. doi:10.1080/09644000802075609

- Fabre, E., and W. Swenden. 2013. “Territorial Politics and the Statewide Party.” Regional Studies 47 (3): 342–355. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.733073

- Filippov, M., O. V. Shvetsova, and P. C. Ordeshook. 2004. Designing Federalism. A Theory of Self-Sustainable Federal Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fink, A. 2017. “Donations to Political Parties: Investing Corporations and Consuming Individuals?” Kyklos 70 (2): 220–255. doi:10.1111/kykl.12136

- Fisher, J. 2018. “Party Finance.” Parliamentary Affairs 71: 171–188. doi:10.1093/pa/gsx055

- Flanagan, SC, and Dalton RJ. 1984. “Parties Under Stress: Realignment and Dealignment in Advanced Industrial Societies.” West European Politics 7 (1): 7–23. doi:10.1080/01402388408424456.

- Freitag, M., and A. Vatter. 2008. “Demokratiemuster in den deutschen Bundesländern. Eine Einführung.” In Die Demokratien der deutschen Bundesländer. Politische Institutionen im Vergleich, edited by M. Freitag and A. Vatter, 11–32. Opladen: UTB.

- Gelman, A., and J. Hill. 2006. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Leiden: Cambridge University Press.

- Hardin, J. W., and J. M. Hilbe. 2007. Generalized Linear Models and Extensions. 2nd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

- Hepburn, E., and K. Detterbeck. 2013. “Federalism, Regionalism and the Dynamics of Party Politics.” In Routledge Handbook of Regionalism and Federalism, edited by J. Loughlin, J. Kincaid, and W. Swenden, 76–92. London: Routledge.

- Hildebrandt, A., and F. Wolf. 2016. “How Much of a Sea-Change? Land Policies after the Reforms of Federalism.” German Politics 25 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1080/09644008.2016.1164842

- Jacob, M. S., and J. Pollex. 2021. “Party Fragmentation and Campaign Spending: A Subnational Analysis of the German Party System.” Party Politics, forthcoming.

- Jeffery, C. 1999. “Party Politics and Territorial Representation in the Federal Republic of Germany.” West European Politics 22 (2): 130–166. doi:10.1080/01402389908425305

- Jeffery, C. 2003. “The Politics of Territorial Finance.” Regional & Federal Studies 13 (4): 183–196. doi:10.1080/13597560308559451

- Jeffery, C. 2005. “Federalism: The New Territorialism.” In Governance in Contemporary Germany. The Semisovereign State Revisited, edited by S. Green and W. E. Paterson, 78–93. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jeffery, C., N. M. Pamphilis, C. Rowe, and E. Turner. 2014. “Regional Policy Variation in Germany. The Diversity of Living Conditions in a ‘Unitary Federal State’.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (9): 1350–1366. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.923022 .

- Johnston, R. J., and C. J. Pattie. 2007. “Funding Local Political Parties in England and Wales: Donations and Constituency Campaigns.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 9 (3): 365–395. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856x.2007.00296.x

- Laakso, M., and R. Taagepera. 1979. “‘Effective’ Number of Parties: A Measure with Application to West Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 12 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1177/001041407901200101

- Lösche, P. 1984. Wovon leben die Parteien? Über das Geld in der Politik. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag.

- Lösche, P. 1993. “Problem of Party and Campaign Financing in Germany and the United States—Some Comparative Reflections.” In Campaign and party finance in North America and Western Europe, edited by A. B. Gunlicks, 219–230. Boulder: Routledge.

- Mannewitz, T. 2017. “Really ‘Two Deeply Divided Electorates’? German Federal Elections 1990–2013.” German Politics 26 (2): 219–234.

- McMenamin, I. 2012. “If Money Talks, What Does it Say? Varieties of Capitalism and Business Financing of Parties.” World Politics 64 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1017/S004388711100027X

- McMenamin, I. 2013. If Money Talks, What Does it Say? Corruption and Business Financing of Political Parties. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McMenamin, I., 2019. Party Identification, the Policy Space and Business Donations to Political Parties. Political Studies 68 (2): 293–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719841243.

- Müller, J. 2018. “German Regional Elections: Patterns of Second-Order Voting.” Regional & Federal Studies 28 (3): 301–324. doi:10.1080/13597566.2017.1417853

- Nassmacher, K.-H. 2009. The Funding of Party Competition. Political Finance in 25 Democracies. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Pattie, C. J., R. J. Johnston, and E. A. Fieldhouse. 1995. “Winning the Local Vote: The Effectiveness of Constituency Campaign Spending in Great Britain, 1983-1992.” American Political Science Review 89 (4): 969–983.

- Petersohn, B., N. Behnke, and E. M. Rhode. 2015. “Negotiating Territorial Change in Multinational States: Party Preferences, Negotiating Power and the Role of the Negotiation Mode.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 45 (4): 626–652.

- Rueschemeyer, M. 1998. “The Social Democratic Party in Eastern Germany.” In Participation and Democracy, East and West. Comparisons and Interpretations, edited by D. Rueschemeyer, M. Rueschemeyer, and B. Wittrock, 99–131. Armonk, NY, London: M.E. Sharpe.

- Saalfeld, T. 2000. “Court and Parties: Evolution and Problems of Political Funding in Germany.” In Party Finance and Political Corruption, edited by R. Williams, 89–121. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schniewind, A. 2008. “Parteiensysteme.” In Die Demokratien der deutschen Bundesländer. Politische Institutionen im Vergleich, edited by M. Freitag and A. Vatter, 63–109. Opladen: UTB.

- Stoiber, M., and B. Egner. 2008. “Ein übertragbarer Amtsinhaber-Bonus bei Kommunalwahlen.” Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 2 (2): 287–314. doi:10.1007/s12286-008-0015-0

- Träger, H., J. Pollex, and M. S. Jacob. 2020. “Amtsinhaber-Effekte in „unsicheren“ Wahlkreisen – eine Analyse anhand der Landtagswahlen in Brandenburg, Sachsen und Thüringen (1990 bis 2019).” ZParl Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 51 (2): 349–366.

- Verge, T., and R. Gómez. 2012. “Factionalism in Multi-Level Contexts.” Party Politics 18 (5): 667–685. doi:10.1177/1354068810389636