ABSTRACT

This article introduces a new dataset on regionalist actors’ territorial demands and frames in Europe. The FraTerr dataset advances on existing datasets by proposing a more fine-grained understanding of regionalist actors’ territorial demands, and is the first to provide comparative data on how these are framed. Methodologically, it develops an original coding scheme for the qualitative content analysis of political documents. Empirically, this approach is applied to a comparative study of regionalist parties and civil society actors in twelve European regions. A preliminary analysis of the data provides new evidence of the complexity of regionalist actors’ territorial demands and the multi-dimensional nature of their framing strategies. The dataset has implications for the study of regionalist actors and issues, and for broader scholarly efforts at estimating political actors’ territorial issue positions and framing strategies.

1. Introduction

This article introduces the Framing Territorial Demands (FraTerr) dataset, which provides new data on the territorial demands and framing strategies of 61 actors in twelve regions in eight European countries for the period 1990–2018. The dataset advances on extant datasets in the field in three ways. Firstly, instead of attributing to regionalist actors a single territorial demand or position, it provides a more fine-grained conceptualization of the kinds of demands regionalists make and allows for the possibility that regionalists make several different territorial demands simultaneously. Secondly, it is the first comparative dataset that systematically assesses the frames that regionalist actors use to justify their territorial demands. Thirdly, the dataset has a broader empirical scope as a result of the inclusion of regionalist political parties and civil society actors.

In the next section, we review extant studies of the territorial strategies of regionalist actors, and present FraTerr’s alternative conceptualization and measurement of these actors’ territorial demands and frames. We then introduce the methodology used to compile the FraTerr dataset, before presenting a first analysis of the data in order to highlight its potential for advancing scholarly understandings of regionalist actors’ territorial strategies. The FraTerr dataset significantly advances the study of territorial politics in two respects: it enables scholars to examine aspects of regionalist mobilization that have been neglected to date, and provides a coding scheme and methodology that can be applied to regionalist actors in other cases as well as to other types of political actors who mobilise on territorial issues.

2. Re-conceptualizing regionalist actors’ territorial strategies

Scholars of regionalist mobilization have increasingly sought to understand the agency of regionalist actors in translating structural inequalities between centres and peripheries within a state, into arguments for the territorial re-structuring of political authority (Türsan Citation1998, 6). The territorial dimension thus constitutes the core issue dimension for this party family, since at stake is the issue of ‘political control over a (peripheral) territory’ (Alonso Citation2012, 25).

Several datasets have been compiled with the aim of comparing how regionalist parties strategise on the territorial dimension. The exclusive focus to date has been on the kind of changes to the territorial organization of political authority regionalists have sought. One approach entails categorizing regionalist actors’ territorial demands on a spectrum reflecting degrees of self-government ranging from administrative decentralization to full independence. The Regionalist Party dataset, for instance, draws on published secondary sources to classify regionalist parties from 11 countries for the period 1945–2010 according to whether they adopt separationist, ambiguous, federalist or protectionist positions (Massetti and Schakel Citation2013; Citation2016).

An alternative approach has been adopted by cross-national datasets that identify regionalist parties’ positions on a ‘centre-periphery’ (Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza Citation2013),Footnote1 ‘ethno-national’ (Szöcsik and Zuber Citation2015; Zuber and Szöcsik Citation2019) or ‘decentralist-centralist’ (Basile Citation2019) dimension.Footnote2 Whilst the Regional Manifesto Project (RMP) (Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza Citation2013) and Basile’s dataset (Basile Citation2019) have been compiled through the content analysis of party manifestos, the Ethnonationalism in Political Competition (EPAC) dataset relies on an expert survey (Szöcsik and Zuber Citation2015; Zuber and Szöcsik Citation2019). The empirical scope of these datasets also varies. Basile (Citation2019) analyses the manifestos of Italian state-wide parties and the Lega Nord (LN) from 1948 to 2018, whilst the RMP provides data for state-wide parties and many regionalist parties in Spain, the UK and Italy for varying time periods; the EPAC datasets provide data on ethnic parties in 22 European countries for two time periods (210 parties in 2011 and 222 in 2017).

More recently, scholars have also begun to explore how regionalist actors justify, or frame, their territorial claims (Huszka Citation2014; Field and Hamann Citation2015; Dalle Mulle Citation2016, Citation2017; Brown Swan Citation2017; Máiz and Ares Castro-Conde Citation2018; Basile Citation2019; Elias Citation2019; Della Porta et al. Citation2017; Basta Citation2018). This work adopts an inductive approach, with frames identified through a close qualitative examination of political texts for one or a few cases of regionalist mobilization. Whilst this allows for sensitivity to context-specific rhetorical nuances and complexities, it makes it difficult to generalize across cases to arrive at a broader understanding of how regionalist actors frame their territorial demands. There is currently no cross-national dataset of regionalist actors’ framing strategies that permits such a comparative analysis to be undertaken.

The FraTerr dataset advances on existing datasets in two ways. Firstly, instead of attributing to regionalist actors a single territorial demand or position on the territorial dimension, it provides a more fine-grained conceptualization of the kinds of demands regionalists make and allows for the possibility that regionalists make several different territorial demands simultaneously. Secondly, it constitutes the first comparative dataset of how regionalist actors frame their territorial demands, based on an original categorization of regionalists’ frames. The rest of this section expands on these innovations. Empirically, whilst other datasets have focused exclusively on regionalist parties, the key advance provided by the FraTerr dataset is its analysis of territorial demands and frames for regionalist parties and civil society actors; the next section expands on this empirical scope and the methodological approach adopted for data collection.

2.2. Re-conceptualizing territorial demands

The FraTerr dataset understands territorial demands as demands that regionalist actors formulate for the territorial empowerment of the region they seek to represent (Hepburn Citation2009, 482). Much of the scholarship has assumed that such demands entail more ‘self-government’, understood as the shift of political authority from the state to the region (Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza Citation2013, 191; Mazzoleni and Mueller Citation2016, 2). The FraTerr dataset departs from this assumption in two ways. Firstly, it proposes a more fine-grained conceptualization of the kinds of territorial demands made by regionalists to reflect the fact that these actors often call for other forms of territorial re-structuring. For example, regionalist parties have been found to make shared-rule demands, whereby they want to enhance the capacity of a regional government to shape central decision-making (Hepburn Citation2009, 484). We thus follow the RMP dataset in including a demand for more shared-rule in the FraTerr coding scheme (Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza Citation2013). Hepburn (Citation2010, 34) also argues that regionalist parties may be willing to trade-off political autonomy (and agree to re-centralization in specific policy areas) in exchange for additional resources in a different policy area of importance to the sub-state territory. In specific circumstances, therefore, regionalists may also make demands to re-centralise political authority, and the FraTerr coding scheme can capture such demands.

Furthermore, not all territorial demands necessarily imply a formal redistribution of authority or shift in power relations; they may instead consist of calls for action by other levels of government to empower the sub-state territory in some way. Scholars have mostly identified such demands in relation to calls by ‘protectionist’ parties for the cultural or political recognition of a sub-state territory’s distinctiveness, or for cultural or economic resources, within the framework of the existing state (De Winter Citation1998, 205; Dandoy Citation2010). Informed by this work, the FraTerr dataset is novel in its inclusion of a category for ‘action’ demands to capture such calls for action in relation to the territory’s identity and/or interests within the existing territorial framework.

Secondly, whilst extant datasets attribute to regionalist actors a single territorial demand or position, in reality regionalist actors often pursue different territorial goals simultaneously. For example, regionalist political parties have been found to pursue long-term territorial aspirations alongside more short-term instrumental or pragmatic demands to improve ‘their’ territory’s autonomy (Hepburn Citation2009; Lluch Citation2014; Dalle Mulle Citation2016; Basile Citation2019). In other cases, the adoption of a plurality of territorial goals is a deliberate strategy for accommodating diverging territorial preferences within the party organization (Mees Citation2015). Datasets that classify regionalist actors according to their main territorial demand or identify their position on the centre-periphery dimension cannot capture this complexity to regionalists’ territorial claims. In contrast, the FraTerr dataset provides data on the multiple territorial demands that regionalists may make simultaneously. This constitutes a more nuanced measurement of territorial demands that reflects the reality that regionalists often pursue a differentiated territorial strategy that encompasses more moderate and radical claims at the same time.

Informed by the discussion above, the FraTerr dataset thus differentiates between four categories of territorial demands based on the nature of the change they imply to existing political systems. The logic of the categorization reflects the degree of territorial change implied from more to less radical:

Territorial demands that imply a formal re-distribution of authority between different territorial levels. We further distinguish here between a. demands for independence (understood as the withdrawal of existing constitutional framework); and b. demands for the re-structuring of the existing territorial framework. For the latter category, and drawing on Dardanelli (Citation2019, 282), we further differentiate between strong restructuring leading to a ‘difference in the kind’ of territorial model (e.g. transition from unitary to decentralized or federal state), and weak restructuring constituted by changes that do not entail a transition from one type of territorial model to another, that is, ‘difference of degree’ rather than of kind. We capture this distinction in our coding scheme by distinguishing between demands for fundamental reform (creation or re-organization of regional government, establishment of a federal system, or general territorial re-organization of the state); and demands for modification of the existing political system (more self-rule, shared-rule or centralization). In order to capture the possibility that regionalist actors may not discuss in detail the nature of the territorial re-structuring they aspire to, the coding scheme also includes ‘general’ codes for the latter two categories.

Territorial demands for action that imply an empowerment of the territory without altering the existing territorial framework. We further distinguish between a. demands for intervention (action by another actor in, or in relation to, the territory in some way); and b. demands for non-intervention (for a political actor to refrain from intervening in, or in relation to, the territory in some way).

General territorial demands that imply some kind of change to the existing territorial framework, that is not specific about the nature of the change implied (and therefore none of the above categories can be applied).

Unspecified territorial demands. This last category captures narratives related to changing the existing territorial framework in some way, but where no territorial demand was articulated, nor could the narrative be linked directly to one. These discourses may provide a narrative about the support for, or legitimation to, a regionalist actor’s territorial demands, for example by placing it in a broader context, or by discussing the territorial identity and/or interests that underpin the actor’s territorial demands. Such a narrative is an important element of regionalist actors’ framing strategies, as argued below. This category thus serves the purpose of capturing (and coding) such frames, rather than any specific territorial demand.

FraTerr also conceptualizes territorial demands within a multi-level context. We do so since regionalist actors have sought to empower their territories not only in relation to the state, but also in relation to other levels of government (Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza Citation2013, 193–194). For instance, regionalist parties have interpreted the European Union (EU) as a new structure of opportunity for achieving their territorial goals (Jolly Citation2015), with many during the 1980s and 1990s calling for the creation of a ‘Europe of the Regions’ (Elias Citation2008, Citation2009a). Regionalist actors may also look to international organizations and legal frameworks on human and minority rights for support for their territorial demands (Elias Citation2009a, 114). In order to capture the multi-level scope of regionalist actors’ territorial demands, for each specific territorial demand (i.e. all categories apart from unspecified territorial demands), the FraTerr dataset codes the level in relation to which a territory would be empowered if the territorial demand made were achieved (region, state, EU or international).

Finally, scholars have increasingly recognized the important ‘competential dimension’ (Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza Citation2013, 191; Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza Citation2017, 255–257) to territorial demands, where territorial contestation takes place in relation to a range of policy areas. Accordingly, the FraTerr database includes a set of codes that capture the policy area to which a territorial demand relates. Since ‘every public policy has spatial dimensions (it has to apply somewhere), in principle any domain of political decision-making is a potential object of such explicit territorialisation’ (Mazzoleni and Mueller Citation2016, 8). FraTerr thus adapts the list of policy areas provided by Basile (Citation2019) and specifies 21 policy areas in relation to which a territorial demand can be made (see ).Footnote3

Table 1. Regionalist actors’ demands for territorial empowerment (text in bold indicates the FraTerr coding categories).Table Footnotea

2.2. Conceptualizing regionalist actors’ framing strategies

The extant literature on regionalist actors’ framing of their territorial demands has (with some exceptions) employed the terminology of ‘framing’ relatively loosely and has not always clearly conceptualized ‘frames’ or ‘frame analysis’. In contrast, the FraTerr dataset takes as its starting point recent work that has examined political actors’ use of ‘justification frames’, where these are understood as arguments that add political meaning to an issue or position by providing ‘a legitimating basis for taking up a specific stance’ (Statham and Trenz Citation2012, 128–129). Such frames thus provide insight into how different actors define a particular problem, and direct attention to certain causes and consequences in order to convey what is at stake on a specific issue (Helbling Citation2014, 23).

FraTerr’s categorization of frames was developed based on a review of the literature on territorial politics, and the specific studies of regionalist actors’ framing strategies discussed above. Four thematic groups of frames were identified: cultural, socio-economic, political and environmental. The first three of these are informed by the argument advanced by Rokkan and Urwin (Citation1983) that the territorial inequalities inherent in the centre-periphery cleavage can be observed along cultural, economic and political dimensions. This conceptualization of the centre-periphery cleavage has proved enduring in subsequent scholarly work (e.g. Keating Citation1988; Massetti, Citation2009; Fitjar Citation2009; Alonso Citation2012). The fourth category of environmental frames reflects the findings of studies that have found territorial claims to be supported by the assertion that it would allow for better stewardship of the environment (e.g. Gómez-Reino Cachafeiro Citation2006, 184; Elias Citation2009b; Hepburn Citation2010, 180). A fifth category of ‘other’ frames aims to capture arguments that do not fit into the previous categories. In a second step, we identified specific frames within each of the thematic groups. The resultant frame categories are presented in below.

Table 2. Regionalist actors’ frames (text in bold indicates the coding categories included in the FraTerr coding scheme).

3. Overview of the FraTerr dataset

3.1. Case and actor selection

The FraTerr database covers 39 regionalist parties and coalitions, 14 civil society organizations and coalitions and 8 coalitions of parties and civils society actors in twelve regionsFootnote4 across eight European countries: Scotland and Wales (UK); Catalonia and Galicia (Spain); Corsica (France); Bavaria (Germany); Aosta Valley, Northern ItalyFootnote5 and Sardinia (Italy); Friesland (Netherlands); Kashubia (Poland); and the Hungarian minority/the Szeklerland (Romania). The selected actors are listed in the Appendix A.

As the FraTerr dataset was collected as part of the Integrated Mechanisms for Addressing Spatial Justice and Territorial Inequalities in Europe (IMAJINE) Horizon 2020 project, our country selection constitutes a sub-set of countries included in the larger project.Footnote6 Within these countries, we selected regions that provide variation across several dimensions that the scholarship has identified as important determinants of regionalist mobilization: (i) key features of the state within which the regions are located (e.g. type of territorial model and date of EU membership); (ii) economic, cultural and political characteristics of the regions themselves; and (iii) the number and ideology of the regionalist movements that have mobilized (see Elias et al. (Citation2018) for a full discussion).Footnote7

Within the selected regions, we identified the most relevant regionalist parties and civil society organizations that have mobilized around demands for territorial empowerment between 1990 and 2018. To establish a relevance criterion for the selection of regionalist parties, we follow Massetti and Schakel (Citation2016) by examining those that (since 1990) have obtained at least 1% of the vote and/or one seat in more than one state-wide (national) or regional elections. For civil society organizations, establishing a relevance criterion is more difficult since the electoral criterion does not apply, and as the nature of these actors varies extensively across our cases. We thus adopt a more subjective approach, whereby case-study experts, based on their in-depth knowledge of the case and published secondary sources, selected organizations considered to be the most relevant in terms of their contribution to debates about, and key developments in, territorial restructuring during the time period under consideration.

3.2. Document selection and collection

For the analysis of regionalist parties’ territorial demands and frames, we collected for each selected party all election manifestos for regional, state-wide and European elections between the time period 1990–2018. As election manifestos represent the authoritative positions of a political party, provide a synthetic position in light of internal divergences (Harmel et al. Citation2018), are issued regularly in the run-up to elections, and are publicly available (Budge et al. Citation2001), they represent an ideal minimum sample of programmatic documents for the study of regionalist parties’ territorial strategies. When election manifestos were not available, proxy documents (e.g. conference proceedings) were selected from the election year. This minimum sample was supplemented by other relevant programmatic documents addressing the key milestones and periods of regionalist mobilization outside of election campaigns during the period 1990 and 2018, such as policy position papers, political statements, legislative proposals and press releases. For regionalist civil society organizations, similarly to the selection of party documents, a minimum sample of documents was defined as the most relevant programmatic documents addressing the key milestones and periods of regionalist mobilization during the period 1990 and 2018. These included policy position papers, political statements, legislative proposals and press releases; whilst some of these were issued to coincide with elections, others were not. This resulted in a total of 581 documents included and content analysed in the FraTerr dataset (see Appendix B for an overview of the documents).

3.3. Qualitative content analysis of regionalist actors’ territorial demands and frames

Using the coding scheme introduced in the previous section, we conducted a qualitative content analysis of the selected documents with computer assisted manual coding, using the software MAXQDA. We coded only those sections in each document that contained a narrative about changing the territorial status quo in some way. The salience of territorial demands and frames are thus calculated out of the total number of territorial demands and frames coded in the document. In this respect, our approach differs to that adopted by other data collection projects based on qualitative content analysis of political documents (e.g. Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza Citation2013; Volkens et al. Citation2020) which calculate the salience of territorial demands relative to the document as a whole (including non-territorial demands).

Following previous work (Werner, Lacewell, and Volkens Citation2015, 6; Basile Citation2019), we define the coding unit as a quasi-sentence that contains exactly one statement or argument. For our purposes, we furthermore require each quasi-sentence to contain a maximum of one territorial demand that is linked to a maximum of one level of territorial empowerment, policy area, and frame. Natural sentences containing more than one of each of these elements are therefore split into quasi-sentences.

3.4. The FraTerr dataset

The coding process resulted in the FraTerr_segments dataset containing a total of 32,393 coded quasi-sentences from 581 documents of 61 regionalist actors across Europe. The FraTerr_documents dataset aggregates the data from the FraTerr_segments dataset to the level of documents. It provides, therefore, the number of quasi-sentences coded in each document with the coding variables presented in and above. The measures of regionalist actors’ territorial demands and frames provided in the FraTerr_document dataset are summarized in Appendix C. Reliability and validity tests were performed to assess the accuracy and consistency of the measurements obtained with the FraTerr coding process relative to other datasets; a detailed discussion of these tests is provided in Appendix D.

4. Analysing regionalist actors’ territorial strategies using the FraTerr dataset

This section presents the results of two document-level analyses of the FraTerr datasetFootnote8 to illustrate its potential for providing new insights into the territorial strategies of regionalist actors. Firstly, the results of an analysis of territorial demands show that independence demands are the most frequently formulated territorial demands by regional actors included in the dataset (mean value across documents of 32%). These are followed by demands for self-rule (mean of 19%), intervention (17%), general demands (7%) and non-intervention (4%).Footnote9 The remaining categories of territorial demands are relatively little used. The analysis also confirms that regionalist actors often make a plurality of territorial demands simultaneously: 62% of documents contain at least two types of territorial demands.

Secondly, the results of an analysis of regionalist actors’ frames indicate that political frames are by far the most widely used to justify territorial demands: regionalist actors use political frames in 41% of their territorial discourses on average, and 91% of documents contained such frames.Footnote10 Within this group, the most salient frame is that alluding to the democratic quality of the political system (mean of 9%), followed by dissatisfaction with, and attribution of blame for, the territorial status quo (mean of 6% and 5% respectively), and frames asserting the regional community’s sovereignty (5%).

After political frames, socio-economic frames are the most used (mean value across documents of 17%), with those relating to social justice and economic prosperity predominating (both with mean values of 6%). In contrast, cultural and (especially) environmental frames are much less utilized overall (mean of 8% and 2% respectively). Among cultural frames, those invoking a sense of territorial identity as a justification for territorial empowerment (2%), as well as those relating to linguistic, cultural and/or historical distinctiveness (all with a mean value of 2%) are most used, whilst environmental sustainability frame is among the most salient in the environmental group (mean of 1%).

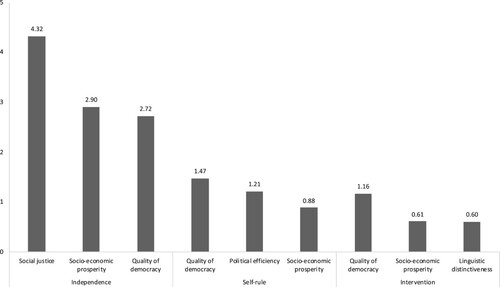

Finally, we explore the frames regionalist actors’ use to justify their territorial demands.Footnote11 We focus on the three most prominent territorial demands as identified above: independence, self-government and intervention. Independence demands are mainly justified in terms of tackling or improving social justice, socio-economic prosperity and the quality of democracy. In comparison, justifications for greater self-rule reveal both similarities and differences: whilst frames relating to the quality of democracy and socio-economic prosperity are also used, so too are those about political efficiency. Finally, whilst demands for policy intervention are also framed predominantly in terms of the quality of democracy and socio-economic prosperity, arguments referring to linguistic distinctiveness are also used in this respect ().

6. Conclusion

The FraTerr dataset presented in this article advances the scholarship on regionalist actors in two major respects. Firstly, it provides more fine-grained data on these actors’ territorial demands than previous datasets, and accounts for the possibility that regionalist actors formulate a range of territorial demands in multiple issue areas addressing different territorial levels at the same time. Secondly, it provides the first cross-national data set of the frames employed by regionalist actors in their territorial discourses.

As a result, the FraTerr dataset enables scholars to examine several aspects of regionalist mobilization that have been neglected in the literature to date. Future work should analyse the variation of regionalist actors’ territorial demands and framing strategies from a cross national perspective, as well as differences between different types of regionalist actors (regionalist parties vs. civil society organizations), changes in demands and frames over time and across different territorial levels (e.g. state vs. EU), and within different types of political documents. The original coding scheme and methodological approach can be applied to the study of regionalist actors in further cases, as well as to other types of political actors (such as state-wide parties) that also have a territorial discourse. In these ways, the FraTerr dataset may significantly advance understandings of the territorial dimension of political debate and contestation in pluri-national states.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (254.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In their conceptualisation of the ‘centre-periphery’ dimension, Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza (Citation2013, 3) differentiate between a ‘competential dimension’ that refers to how political autonomy should be distributed between the state and the peripheral territory, and an ‘identitarian dimension’ which refers to the ‘rationale behind the demands for self-governance’ and which links to processes of nation-building and nation preserving. Here, we refer specifically to the former. The FraTerr dataset captures the latter through the coding of frames. The FraTerr coding scheme also includes an identity frame among others (see below).

2 The Manifesto Project (Volkens et al. Citation2020) and the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al. Citation2015, Citation2020), have sought to measure parties’ position on a decentralisation dimension but do not capture the complexity of the centre-periphery dimension (Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza Citation2013, 192–194) and exclude many regionalist parties (Szöcsik and Zuber Citation2015, 153). Therefore, they do not allow for an in-depth interrogation of regionalist actors’ territorial strategies.

3 Basile (Citation2019, 13–15) identifies 25 policy areas in which competencies are distributed between the state and regions according to the Italian Constitution. As some of these policy areas overlap and are therefore difficult to differentiate, they were merged (e.g. ‘identity and cultural policies’ and ‘cultural policy’ merged to create ‘culture’ policy). Other policy areas that were identified whilst piloting the coding scheme but were not included in Basile’s policy list, were added (e.g. policies relating to European integration.)

4 In the case of the majority of the selected regions, the region which regionalist actors seek to represent is congruent with the existing regional administrative structures. However, in Northern Italy and in the case of the Hungarian minority in Szeklerland, the imagined and represented region spans several administrative regions/counties. In addition, whilst some Catalan regionalist actors also aim to mobilise in Catalan-speaking regions beyond Catalonia, we focus here on mobilisation within the Catalan autonomous region. In the case of Kashubia, prior to 1998 the Kashubian linguistic group was dispersed across three provinces. Since the territorial reforms in 1998, the Kashubian linguistic group is united in the voivodship of Pomerania.

5 We use 'Northern Italy' here since a Padanian territorial entity has never existed geographically or historically, and the Lega Nord’s electoral appeal has been strongest in the northern parts of Lombardy and Veneto (Giordano Citation1999; Massetti and Schakel Citation2013).

6 The countries included in the IMAJINE project are: Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain and the United Kingdom.

7 This selection necessarily excludes some regions with sustained and significant regionalist mobilisation (e.g. the Basque Country in Spain, South Tyrol in Italy and Brittany in France etc.). However, the FraTerr coding scheme can be applied to these cases, and this constitutes an important avenue for future research.

8 We use the FraTerr_documents dataset in these analyses (see Appendix C).

9 In this analysis, we use the per variables which compute the share of types of territorial demands based on the total number of specified territorial demands (see Appendix C).

10 We use here the per2 variables, which compute shares based on the total number of coded segments, including those coded as unspecified territorial demands (see Appendix C).

11 These results are based on the per_FRAME_TD variables that link frames to demands (see Appendix C).

References

- Alonso, S. 2012. Challenging the State: Devolution and the Battle for Partisan Credibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Alonso, S., B. Gómez, and L. Cabeza. 2013. “Measuring Centre–Periphery Preferences: The Regional Manifestos Project.” Regional & Federal Studies 23 (2): 189–211.

- Alonso, S., B. Gómez, and L. Cabeza. 2017. “‘Disentangling Peripheral Parties’ Issue Packages in Subnational Elections.” Comparative European Politics 15 (2): 240–263.

- Bakker, R., E. Edwards, L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, J. Koedam, F. Kostelka, G. Marks, et al. 2015. 1999 − 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File - Version 1.13. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Accessed November 25, 2020. chesdata.eu.

- Bakker, R., L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, G. Marks, J. Polk, J. Rovny, M. Steenbergen, and M. A. Vachudova. 2020. 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey - Version 2019.1. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Accessed November 25, 2020. chesdata.eu.

- Basile, L. 2019. The Party Politics of Decentralization: The Territorial Dimension in Italian Party Agendas. London: Palgrave.

- Basta, K. 2018. “The Social Construction of Transformative Political Events.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (10): 1243–1278.

- Brown Swan, C. 2017. “The Art of the Possible: Framing Self-government in Scotland and Flanders.” PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh.

- Budge, I., H. D. Klingemann, A. Volkens, J. Bara, and E. Tanenbaum. 2001. Mapping Policy Preferences: Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments, 1945-1998. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalle Mulle, E. 2016. “New Trends in Justifications for National Self-Determination: Evidence from Scotland and Flanders.” Ethnopolitics 15 (2): 211–229.

- Dalle Mulle, E. 2017. The Nationalism of the Rich: Discourses and Strategies of Separatist Parties in Catalonia, Flanders, Northern Italy and Scotland. London: Routledge.

- Dandoy, R. 2010. “Ethno-regionalist Parties in Europe: A Typology.” Perspectives on Federalism 2 (2): 194–220.

- Dardanelli, P. 2019. “Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Mapping State Structures—With an Application to Western Europe, 1950–2015.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 49 (2): 271–298.

- Della Porta, D., F. O’Connor, M. Portos, and M. Subirats Ribas. 2017. Social Movements and Referendums from Below: Direct Democracy in the Neoliberal Crisis. London: Policy Press.

- De Winter, L. 1998. “A Comparative Analysis of the Electoral, Office and Policy Success of Ethnoregionalist Parties.” In Regionalist Parties in Western Europe, edited by L. De Winter, and H. Türsan, 204–247. London: Routledge.

- Elias, A. 2008. “Whatever Happened to the Europe of the Regions? Revisiting the Regional Dimension of European Politics.” Regional & Federal Studies 18 (5): 483–492.

- Elias, A. 2009a. Minority Nationalist Parties and European Integration: A Comparative Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Elias, A. 2009b. “From Protest to Power: Mapping the Ideological Evolution of Plaid Cymru and the Bloque Nacionalista Galego.” Regional & Federal Studies 19 (4-5): 533–557.

- Elias, A. 2019. “Making the Economic Case for Independence: The Scottish National Party’s Electoral Strategy in Post-Devolution Scotland.” Regional & Federal Studies 29 (1): 1–23.

- Elias, A., E. Szöcsik, R. Siegrist, J. Miggelbrink, and F. Meyer. 2018. “D1.1 Conceptual Review of the Scientific Literature.” Integrated Mechanisms for Addressing Spatial Justice and Territorial Inequalities in Europe (IMAJINE). Accessed April 4, 2020. http://imajine-project.eu/result/project-reports/.

- Field, B., and K. Hamann. 2015. “Framing Legislative Bills in Parliament: Regional-Nationalist Parties’ Strategies in Spain’s Multinational Democracy.” Party Politics 21 (6): 900–911.

- Fitjar, R. D. 2009. The Rise of Regionalism: Causes of Regional Mobilization in Western Europe. London: Routledge.

- Giordano, B. 1999. “A Place Called Padania? The Lega Nord and the Political Representation of Northern Italy.” European Urban and Regional Studies 6 (3): 215–230.

- Gómez-Reino Cachafeiro, M. 2006. “The Bloque Nacionalista Galego: From Political Outcast to Success.” In Autonomist Parties in Europe: Identity Politics and the Revival of the Territorial Cleavage, edited by De Winter, L. Gómez-Reino Cachafeiro, and M. and Lynch, 167–196. Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.

- Harmel, R., A. C. Tan, K. Janda, and J. M. Smith. 2018. “Manifestos and the “Two Faces” of Parties: Addressing Both Members and Voters with One Document.” Party Politics 24 (3): 278–288.

- Helbling, M. 2014. “Framing Immigration in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (1): 21–41.

- Hepburn, E. 2009. “Introduction: Re-Conceptualizing Sub-State Mobilization.” Regional & Federal Studies 19 (4–5): 477–499.

- Hepburn, E. 2010. Using Europe: Territorial Party Strategies in a Multi-Level System. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Huszka, B. 2014. Secessionist Movements and Ethnic Conflict: Debate-Framing and Rhetoric in Independence Campaigns. New York: Routledge.

- Jolly, S. 2015. The European Union and the Rise of Regionalist Parties. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Keating, M. J. 1988. State and Regional Nationalism: Territorial Politics and the European State. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Lluch, J. 2014. Visions of Sovereignty: Nationalism and Accommodation in Multinational Democracies. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Máiz, R., and C. Ares Castro-Conde. 2018. “The Shifting Framing Strategies and Policy Positions of the Bloque Nacionalista Galego.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 24 (2): 181–200.

- Massetti, E. 2009. “Explaining Regionalist Party Positioning in a Multi-dimensional Ideological Space: A Framework for Analysis.” Regional and Federal Studies 19 (4/5): 501–531.

- Massetti, E., and A. H. Schakel. 2013. “Ideology Matters: Why Decentralization has a Differentiated Effect on Regionalist Parties’ Fortunes in Western Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 52 (6): 797–821.

- Massetti, E., and A. H. Schakel. 2016. “Between Autonomy and Secession: Decentralization and Regionalist Party Ideological Radicalism.” Party Politics 22 (1): 59–79.

- Mazzoleni, O., and S. Mueller. 2016. “Introduction: Explaining the Policy Success of Regionalist Parties in Western Europe.” In Regionalist Parties in Western Europe. Dimensions of Success, edited by O. Mazzoleni, and S. Mueller, 501–531. London: Routledge.

- Mees, L. 2015. “Nationalist Politics at the Crossroads: The Basque Nationalist Party and the Challenge of Sovereignty (1998–2014).” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 21 (1): 44–62.

- Rokkan, S., and D. W. Urwin. 1983. Economy, Territory, Identity: Politics of West European Peripheries. London: Sage.

- Statham, P., and H.-J. Trenz. 2012. The Politicization of Europe: Contesting the Constitution in the Mass Media. London: Routledge.

- Szöcsik, E., and C. I. Zuber. 2015. “EPAC - A New Dataset on Ethnonationalism in Party Competition in 22 European Democracies.” Party Politics 21 (1): 153–160.

- Türsan, H. 1998. “Introduction: Ethnoregionalist Parties as Ethnic Entrepreneurs.” In Regionalist Parties in Western Europe, edited by L. De Winter, and H. Türsan, 1–16. London: Routledge.

- Volkens, A., T. Burst, W. Krause, P. Lehmann, T. Matthieß, N. Merz, S. Regel, B. Weßels, and L. Zehnter. 2020. The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2020a. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). Accessed November 25, 2020. https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2020a.

- Werner, A., O. Lacewell, and A. Volkens. 2015. Manifesto Coding Instructions (5th revised edition), February 2015. Accessed December 17, 2018. https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/information/documents/handbooks.

- Zuber, C. I., and E. Szöcsik. 2019. “The Second Edition of the EPAC Expert Survey on Ethnonationalism in Party Competition – Testing for Validity and Reliability.” Regional & Federal Studies 29 (1): 91–91.