ABSTRACT

The study of political careers has focused mainly on highly institutionalized systems. This article examines the extent to which the findings from this research agenda apply to more fluid settings, looking at trajectories to the national cabinet in a regime combining presidentialism and federalism: Argentina from 1983 to 2020. We propose an operationalization of political career that integrates five definitional dimensions, looks at full sequences of single occupational positions, and tests six expectations derived from the literature. When only political jobs are taken into account, we found that careers show significant movement from the subnational level and predominance of executive experience. However, when all occupational jobs are considered, political positions are pulled into second place behind the private sector. Most unexpectedly, in a significant percentage of cases, a ministerial position does not appear to be the last step of a political career but rather an initial springboard thereof.

Introduction

The study of political careers has predominantly focused on institutionalized settings, whether macro – concentrating on long-established democracies – or micro – studying fixed-term positions like legislative seats or presidential office. In those settings, rules and practices are widely known and rather stable. But political careers also develop in more open settings, whether due to less institutionalized regimes, critical junctures, or open-term positions such as cabinet ministries. To what extent do the theoretical arguments and analytical tools developed from the former settings apply to the latter? We tackle this question by focusing on a federal presidential cabinet, as the combination of presidential discretion over nominations and the existence of multiple loci of power results in more fluid ministerial careers.

Argentina is one of the five presidential regimes worldwide that combine presidentialism and federalism.Footnote1 The president and vice-president are the only office-holders elected directly by the people – in a single, nationwide electoral district. However, the executive office is unipersonal: the vice-president heads the senate and replaces the president if constitutionally needed, but otherwise does not hold executive power. The country’s federal design means that 23 provinces – plus a functionally equivalent entity, the city of Buenos Aires – have independent authority across the three branches of government, including governors whose powers and competencies resemble the president’s.

We explore paths to the federal cabinet through five sections. The first discusses the state of the art, showing that most of the systematic examination of political careers has focused on legislative positions and consolidated parliamentary systems, thus neglecting the executive side of political careers, particularly in presidential systems. The second presents our analytical framework. Based on previous contributions, we propose an operational definition of political career that looks at full sequences of single occupational positions prior to national cabinet, and distinguishes these positions according to their (a) territorial level – local, regional, national, international; (b) arena – executive, legislative, party, bureaucracy, private; (c) hierarchy; (d) position in the sequence; and (e) duration. Then, we derive a set of expectations regarding the expected characteristics of career paths to the national cabinet in multilevel systems. A brief subsection presents the data. The third section applies the analytical framework to the Argentine case and tests the validity of the six expectations derived from the literature. We find unforeseen variation within and across dimensions and an intriguing predominance of ministers spending most of their previous careers in non-political positions. The fourth section discusses the explanatory power of institutions and parties. We find no clear support for the argument that institutional factors are the most important. While executive-legislative relations, federalism, and party rules provide the opportunity structure, pathways to portfolio seem to be determined to a large extent by contextual and individual factors.

The concluding section warns against adopting too stylized a typology of multi-level political careers, emphasizing the relevance of non-political backgrounds and the role of agency in determining career paths to appointed political positions in open institutional settings.

State of the art

The study of political careers is spread across various research agendas but has only rarely become an autonomous area of study (Jahr and Edinger Citation2015, 9). A remarkable exception is the special issue of Regional and Federal Studies edited by Jens Borchert and Klaus Stolz in 2011. This issue included an analytical framework supported by a thorough revision of the literature, its application to the study of diverse political regimes, and a comparative analysis of the findings and their implications. Its key contribution is a typology of multi-level political careers which, by looking into the quantity and direction of movements across positions, distinguishes three major patterns. The unidirectional pattern refers to careers in which positions are organized along one predominant ladder of hierarchy. The route to power here is delineated by one main cursus honorum. The alternative pattern refers to scenarios where the attractiveness of positions is organized around several sets of hierarchies, allowing for the configuration of simultaneous career options. Boundaries are the key notion, particularly those between levels of government and those between types of institutions, which channel individual trajectories and make it harder to shift from one path to another. Finally, the integrated pattern features arrangements that lack a distinct hierarchy among positions. The image of single or multiple ladders disappears in systems that integrate important political offices relatively equally. This kind of arrangement tends to require a coordinating figure or role, such as a political party or an interest group, ‘in order to limit competition and guarantee professional survival in the midst of that terrible mechanism of job evaluation that democracies provide for elections’ (Borchert Citation2011, 131). The three patterns are presented as ideal types organized in a triangle, with real cases positioned between the three vertices.

The approach travels well across the literature, where political careers are seen as the interaction between individual ambition and a given structure of opportunities moderated by key collective actors. While the operationalization of individual ambition has been rarely discussed, the structure of opportunities has been observed as a wide set of factors, among which the country’s territorial organization has gained increasing attention. The relevance of this factor is crucial. Multilevel systems break the political arena into multiple subsets, increasing the range of opportunities (number of posts) and break unidirectional hierarchies. When it comes to the moderator of individual careers, political parties continue to be highly relevant. The country case studies in Jahr and Edinger (Citation2015) illustrate the validity of this approach, enlarging the scope by including the international level (Edinger Citation2015; Kjær Citation2015; Stolz Citation2015) and emphasizing changes within countries (Lo Russo and Verzichelli Citation2015; Fiers and Noppe Citation2015). Also in line with the mainstream literature, a large number of the case studies in this research concentrate on parliamentary positions, with some exceptions that examine executive positions ‘mostly as either previous experience or as the ‘final destination’ of parliamentarism’ (Jahr and Edinger Citation2015, 20).

Quite possibly because a great deal of existing scholarship has focused on parliamentary regimes, and due to the central relevance of legislative positions in any democratic regime, the bulk of the research has not progressed to a systematic examination of the executive side of political careers. One exception is Siavelis and Morgenstern (Citation2008), who proposed an overarching approach for the study of political recruitment and candidate selection for the legislative and executive branches in Latin American presidential regimes. They argued that legal variables (e.g. electoral rules, geographical organization, possibility of reelection, or legislative strength) and party variables (e.g. campaign financing or issue salience) produce specific types of candidates (such as party loyalists, party adherents or group agents) who, once in power, behave differently in aspects such as campaign behaviour, relations with the executive, personal vote seeking, or legislative discipline. Notably, the precise variables and the expected dynamics vary across different arenas. In this regard, a relevant finding is that, compared to legislative candidates, the selection of executive candidates is less restrained by rules and more sensitive to contextual variables, particularly when the party system is not highly institutionalized. This flexibility ‘for executives also makes clear the adaptability of laws to fit the situation’, where parties and candidates can choose substantially different strategies within one set of rules (Siavelis and Morgenstern Citation2008, 386). In federal systems, the interaction between territorial organization and party organization plays a salient role. When governors are powerful actors, the region-level party opens up different pathways to power.

The application of Siavelis and Morgenstern’s framework to executive political recruitment in Argentina confirms the expectation regarding the centrality of political parties, but emphasizes the role of subnational ones. The reason for this is a combination of electoral and party variables that include a plurality electoral system, concurrent executive and legislative elections, and the use of patronage, pork-barrel and clientelism. Parties that are more institutionalized tend to produce party-insider executives, who in turn appoint party-insider ministers. In contrast, more decentralized or non-programmatic parties tend to produce more party-adherent executives, who select their cabinet and deal with the legislature with less attention to party issues and partisan mechanisms (De Luca Citation2008).

Lodola (Citation2009, see also Citation2017) provides a systematic approach to the comparative study of multilevel political careers applied to Argentina. His framework distinguishes a territorial attribute – including a horizontal dimension (positional movements within the same territorial level) and a vertical dimension (positional movements across different territorial levels) – and a directional attribute, including ‘progressive ambition’ for a better position, and ‘static ambition’ for retaining a position, producing a typology of four kinds of careers. Focusing on subnational deputies in Brazil and Argentina, two large presidential and robust federal systems with strong powers wielded at the subnational level, the author finds support for the distinctive impact of electoral rules and party rules on candidate nomination, producing different types of political career. In Brazil, with open list proportional representation and candidate selection processes that incentivize individual strategies, a seat in the state legislature is attractive both for consolidating political status – as deputies can remain several terms, take part in the decision-making process, and access career-advancing ‘pork’ – and as a step to higher state executive or federal legislative positions. In Argentina, with closed list proportional representation and candidate selection processes controlled by regional party leaders, provincial legislative positions are just one of several resources the party can award to secondary members. In this case, legislative positions are seldom relevant political positions, as deputies tend to stay for one or two terms and rarely move to better positions. The lesser attractiveness of legislative positions compared to executive positions, even at the subnational level, and the decisive role of regional party leaders are well documented in Argentina (De Luca, Jones, and Tula Citation2002; Franceschet and Piscopo Citation2014; Jones et al. Citation2002; Jones and Hwang Citation2005; Kikuchi Citation2018; Micozzi Citation2014).

While the lack of explicit definitions of political career is commonplace in the field (Jahr and Edinger Citation2015; Vercesi Citation2018), basic distinctive attributes are consistently present across diverse studies. The next section aims to identify and operationally define those attributes.

A disaggregated analytical framework

The basic meaning of a ‘career’ can be formulated as ‘the sequence of jobs or positions occupied by an individual’. When talking about a career of the political kind, two alternative units of analysis can be identified. The first concentrates on the individual, looking at pathways followed by certain politicians (Nicholls Citation1991; Sieberer and Müller Citation2017; Di Capua et al. Citation2022). The second focuses on the office, looking at the route leading to certain political position such as a parliamentary seat (Stolz Citation2003; Grimaldi and Vercesi Citation2018; Lodola Citation2017). Hence, the two alternative definitions of political career that may be derived are respectively (a) the sequence of occupational positions of a politician, and (b) the sequence of occupational positions up to a certain political position. Note that while both approaches emphasize political positions, notions like ‘discrete ambition’ that refer to movements in and out of the political arena (Schlesinger Citation1966) implicitly include non-political positions. Guided by our research question, the definition we apply in this article follows the second approach, rephrasing it as the sequence of occupational positions leading to national portfolio in a multilevel system. For the operationalization of this definition, we consider the analytical dimensions most frequently referred to in the literature.

Roads to power can be travelled at different paces. This aspect is given by the sum of time spent by the individual in each job position. Duration, then, is a first analytical dimension that affects both the single position and the full sequence of positions. The sequence of those positions over time is a related dimension, illustrated by the career ladder metaphor. Since a ministerial office is reckoned to be among the top political positions in any democratic regime, it is expected to be achieved at a mature stage of a political career. This is consistent with the traditional cursus honorum, which places ministerial office as the highest steps of the ladder (Jahr and Edinger Citation2015, 21), and it is implicit in the new alternative patterns where the national level is included. The empirical treatment of the notion of sequence is not easy and it has been addressed using two alternative strategies: one looks at the passage between a few isolated positions such as the movement from the local to the national level (Jones et al. Citation2002; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Citation2009; Stolz Citation2003; Borchert and Stolz Citation2011a Docherty Citation2011; Lodola Citation2017) leading to analysis that is too stylized; the other takes full sequences into consideration, leading largely to descriptive analyses that are too disaggregated (Jäckle Citation2016; Jäckle and Kerby Citation2018). We opt for an intermediate strategy that applies a full categorization of just the ‘jumping off point’, – that is, the office taken immediately before ministerial office (Lodola Citation2017).

A third definitional dimension is the institutional arena. The most commonly applied distinction here is between legislative and executive careers (Di Capua et al. Citation2022; Jones Citation2008), but political party (Cotta and Best Citation2008, Fiers and Secker Citation2008) and the bureaucratic arena are also frequently considered (Cotta, de Almeida, and Roux Citation2004; Cotta and de Almeida Citation2008; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Citation2016). As ministerial office is a late position in a political career, much of the pathway is expected to be spent serving in other political positions, including a path through the legislative and party arenas. Again, this is explicit in the traditional trajectory but it is also implicit in other approaches. The pathway to executive office may be more open than for legislative positions but the presence of political experience is expected. To cover this dimension, we first categorize positions according to whether they are located within the political, public administration, or private arenas. Then, we distinguish between executive, legislative and partisan positions in the political arena.

Hierarchy or salience is probably the most present definitional attribute of political career but also the less operationally discussed. The traditional ‘ladder’ is itself a sequence of positions ranked by relevance, from less important to more important. The patterns discussed above can be rephrased by looking at this feature: systems with one hierarchical organization (unidirectional model/one ladder), with more than one (alternative model/several ladders), and with none (integrated model/no ladder). Yet, there is little explicit specification of how the hierarchy is established. Even if there is no agreement on whether the hierarchical organization of positions is static or dynamic (Lodola Citation2009, 262), the fact that political positions have different values, i.e. that some positions are more important than others, is a common assumption (e.g. Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Citation2016, Franceschet and Piscopo Citation2014). As a ministry is near the top of the hierarchy, it is likely to be preceded by the occupation of other important positions. We apply a dichotomous codification, distinguishing hierarchical and non-hierarchical positions within each category of the cross-tabulation between territorial levels and arenas. This procedure allows us to distinguish between key and non-key executive, legislative, partisan and bureaucratic positions within each level.

Last among the basic definitional dimensions is the territorial level, which characterizes pathways according to the geographic localization of the individual positions – e.g. national vs. regional careers – and movement across levels – e.g. static vs. horizontal vs. vertical careers (Cotta and Best Citation2008; Pedersen and Kjaer Citation2008; Copeland and Opheim Citation2011; Stefan Citation2015; Docherty Citation2011). The subnational level is expected to play an appreciable role in multi-level systems (Barragán Manjón Citation2016). Four categories provide full coverage of this dimension: international, national, regional (provinces/states), and local (here, the ‘subnational’ level is split into regional and local categories).

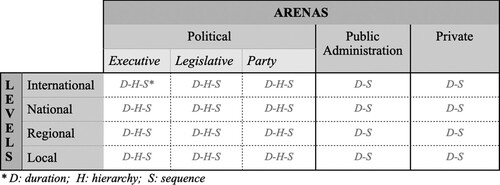

The three career patterns proposed by Borchert (Citation2011) are defined by reference to one element, namely the directional movement of pathways (either one direction, several bounded directions or no identified direction). Although all five definitional attributes identified above are taken into consideration, they were integrated into three groups, taken to be correlated. For instance, unidirectional patterns link territorial level with hierarchy and are associated with short-term positions (p.132). While this strategy may work well for institutionalized systems, where it is acceptable to relate the absence of bounded hierarchical sequences to the notion of an integrated model, it presents notorious difficulties for the examination of less institutionalized countries, where definitional dimensions are less specified and may run in opposite directions. For the present study, we opt for a disaggregated approach and look at each definitional attribute separately ().

While careers leading to the cabinet in presidential systems have rarely been studied, the broader literature discussed above provides a framework to shape assumptions about their elemental characteristics and driving factors. From the definitional dimensions discussed above, we derive a set of descriptive propositions to test with our case. Pathways to cabinet in a multilevel system are expected to present the following characteristics:

To be of considerable length. A standard political career to national cabinet is expected to take a considerable amount of time.

To have a significant incidence of hierarchical positions. A standard political career to national ministry is expected to include transition through other high ranking political positions.

To have a significant incidence of the political arena. A standard political career to national cabinet is likely to include a considerable amount of time spent at other positions within the political arena.

To have a significant incidence of the subnational level. A standard political career to national cabinet is likely to include passage through the subnational level.

Given these considerations, career paths leading to ministerial office in a federal presidential system are expected:

| (v) | To be conditioned by the general arrangement of the political system. The greater the consolidation of the system, the stronger its impact on the consolidation of political careers patterns. | ||||

| (vi) | To be conducted by political parties. Political careers leading to the national cabinet are expected to be guided by party strategies, especially when parties are well-organized. In other cases, individualistic strategies are expected. | ||||

Data

To test the validity of the derived expectations for careers to cabinet in multi-level presidential systems, we examine their applicability to the Argentine case, a consolidated presidential federal system.

The unit of analysis for this study is the single trajectory leading to a national government cabinet portfolio, comprising the sequence of job positions occupied by an individual before becoming minister. The unit of observation is each of those positions. We looked at all single trajectories between the transition to democracy in 1983 and 2020, registering a total of 251 individual careers and 2339 of job positions those individuals held before taking national cabinet post. Each of these positions was categorized according to (i) its localization within the territorial level (local, regional, national, international); (ii) its localization within the arena (executive, legislative, party, public administration, private); (iii) its hierarchy (salient/not salient)Footnote2; (iv) its duration in years; (v) and its precedence to the arrival at the cabinet portfolio (jumping, non-jumping). In situations where more than one position was simultaneously occupied by an individual, we chose the most important one.Footnote3 Each individual sequence starts when the individual was 18 years old. For moments of the sequence with missing information, we assumed that the individual was occupying a non-political and non-hierarchical position (297 out of 2339 posts).

The process of categorization and codification followed a comparative codebook developed by the Presidential Cabinets project, which includes the application of a common matrix for categorizing positions and ranking them according to their salience (Camerlo and Martínez-Gallardo Citation2022). Data were collected mainly from official government sites, online personal information, and leading national journals (Clarín, La Nación, and Página 12). In the next two sections, we use descriptive tools to analyse the distribution, aggregation, and variation across time and types of political parties ().

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of job positions (unit of observation).

Career paths to a federal presidential cabinet

The Argentine political system has been presidential and federal since 1853. The president is both head of state and chief of government, entitled to initiate and veto legislation, and to appoint and dismiss cabinet ministers. She is elected by popular vote for a fixed term (four years since the last constitutional reform in 1994), which can only be interrupted by congress through impeachment. Congress is composed of the Chamber of Deputies (257 members elected for a four-year term by proportional representation, one-half of them renewed every two years) and the Senate (72 members elected for a six-year term, one-third of them renewed every two years). Ministers are responsible for the administration of their departments and for giving legal effect to the president’s legislative actions. They cannot be members of congress but can be summoned to appear before either house and are subject to impeachment. Since 1994, the cabinet includes the position of chief of cabinet, who holds broad competencies over the general administration and is in charge of the coordination of the other ministers. He is politically answerable to congress and can be removed from office by a majority vote of each chamber.

Argentina’s federal organization consists of 24 subnational units with the competence to elect their legislatures and chief executives and to pass their own laws. The provincial political systems replicate the national institutional design closely.

While the first elected government took office in 1916, democracy was only consolidated after 1983 as part of a continental wave that began in the Dominican Republic in 1978. Since then, national politics has pivoted mostly around a two-party competition, where each ‘party’ was either an electoral alliance or a formal party covering an informal party federation. Indeed, both the Justicialist Party (Peronism) and the Radical Civic Union (UCR) function as confederations of subnational parties, whose leaders have the power to select legislative candidates for congress and define electoral alliances at the provincial level (Cherny, Figueroa, and Scherlis Citation2018).

To what extent does the standard pathway to cabinet office characterized by the six expectations identified above apply to our case? We start to answer this question with an aggregated description of all the 251 individual trajectories that led to cabinet between 1983 and 2020.

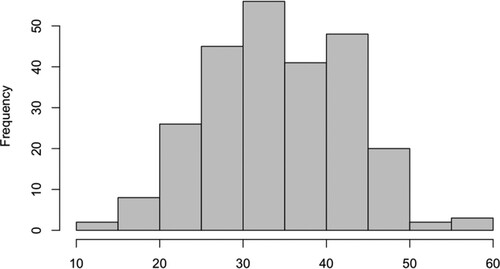

Since a position in the national cabinet is placed near the top of the ladder to power, accessing one of these offices is expected to take time. Consequently, a distribution of the length of these trajectories should be displaced to the right, with most of the observations located at the highest values. contradicts this expectation, showing quite a normal distribution. Access to the Argentine cabinet takes on average 35 years, with cases ranging from 12 to 56 years evenly spread around the median. Given this, expectation 1 regarding the long duration of careers would apply just for the upper tail of that distribution. If the third quartile was taken as a reference, those cases would include the 25% of the observed trajectories which lasted 41 years or more. The other 75% of the cases would not be covered by the expectation, comprising shorter – including very short – trajectories.

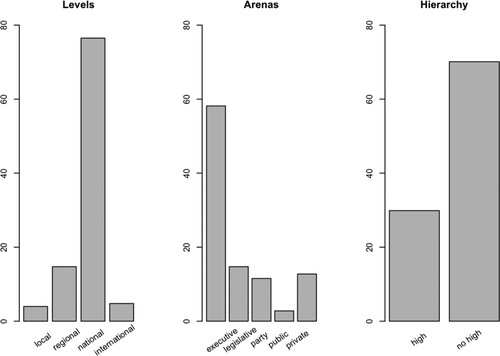

Moving forward in the cursus honorum means moving up, with each step seen as more important than the previous. As the trajectory advances, the salience of the positions taken increases as well. As it is the final step on the ladder, expectation 2 anticipates that the trajectory to the portfolio include the occupation of other salient positions.

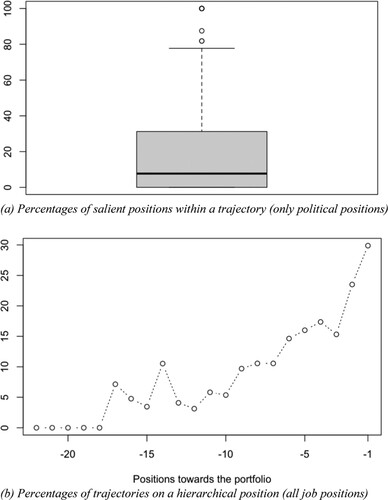

(a) shows the time spent during career paths leading to cabinet ministry at what we code as a hierarchical political positions. On average, the observed trajectories spent 20% of their duration on salient positions, with 50% of the cases spending less than 8% (median = 0.076). In turn, 25% of the trajectories include more than 30% of time at salient positions (3rd quartile = 0.312) or even spend all their time there (max = 1.00, 11 observations).

Figure 3. Hierarchical positions before taking portfolio. (a) Percentages of salient positions within a trajectory (only political positions). (b) Percentages of trajectories on a hierarchical position (all job positions).

(b) complements this examination with the inclusion of non-political positions and the sequence of the positions, showing the percentage of trajectories that were located at a hierarchical position (vertical axis) in each of the previous posts that integrates the career sequence (horizontal axis). For instance, none of the Argentine ministers had occupied a salient political position when they were at their 20th job before acceding to portfolio; about 5% of them occupied one of these posts at their 10th precedent positions; about 16% of them when at the 5th precedent position; and about 30% when they were in the immediately previous position.

This evidence provides two interesting insights on expectation 2. On the one hand, it shows the anticipated incremental distribution of the cases. As trajectories move forward, they move up in salience. However, this dynamic apply to less than 30% of the observed ministers. For most of the cases, then – contrary to anticipated – reaching the top is not strongly associated with having been at the top before.

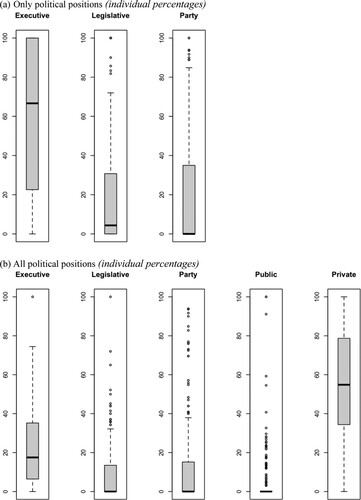

The next figure shows the time spent in different arenas. Looking at the political arena ((a)), the observed trajectories spent on average more than 60% of their time in the executive arena, with 25% of them completely located within it (3rd quartile = 1.00). The average proportion of time spent within the legislative arena was less than 20%, and half spent less than 5% of their time here (median = 0.43). Time spent in party office as dominant position presents similar values (mean = 0.19, median = 0.00). This predominance of executive experience over legislative experience is consistent with expectation 3.

Figure 4. Arenas of careers to portfolio. (a) Only political positions (individual percentages). (b) All political positions (individual percentages).

However, the picture changes when non-political positions are considered, as shown by (b). While executive predominance remains within the political arena, overall, political positions represent on average just about 40% of the time spent in the career path. Overall, time spent in the private sphere is around 53% of the career path (median = 0.55). Finally, public administration represents about 4.5% of career trajectory.Footnote4

A multilevel career comprises, by definition, experience within different territorial units of the political system. In a career to a national position, interest focuses on the extent to which the non-national level is present. The evidence from the Argentine case is consistent with expectation 4 on the relevance of that presence – but with an unforeseen finding, too.

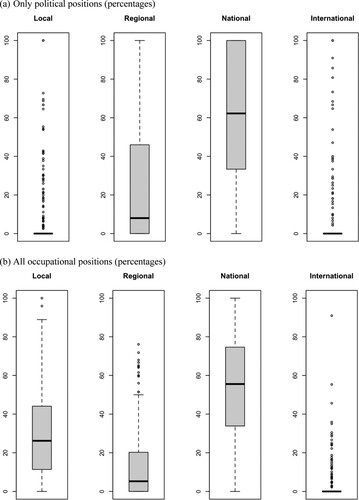

shows the percentage of time spent by each individual trajectory at the different territorial levels. When considering only political positions ((a)), the data show that ministers spent on average about 30% of their trajectories at the subnational level. As illustrated by the first and second bars, most subnational experiences happened at the regional level. On average, ministers spent about 26% of their career paths at the regional level and only about 6% at the local level. Of the 251 observed trajectories, only 23 present subnational experience; of these, 8 had more than 15 years, while the rest show local experience ranging from 1 to 8 years. Overall, experience was at its most at the national level, where ministers spent an average of 60% of their careers. As indicated by the Figure, the preponderance of the national level was absolute for those 25% of individuals located above the third quartile of the distribution.

Figure 5. Levels of careers to portfolio. (a) Only political positions (percentages). (b) All occupational positions (percentages).

The dispersion among levels changes significantly if we zoom out to non-political positions. (b) includes these positions and shows a notable increase of the local level, from 6% to 30%, meaning that, on average, ministers spent 30% of their career there. This increment is at the expense of both the regional level (decreasing from 26% to 13%) and the national level (decreasing from 60% to 55% and showing a general displacement of the upper tail of the distribution to lower values). Given this, the presence of the subnational level in the career to the cabinet is quite relevant – as anticipated – but it is much more important when we include the non-political sphere in the observation.

completes the univariate analysis providing some evidence on the last positions occupied before entering cabinet office. The figure shows that these positions retain a similar configuration to those offered by aggregated figures. Individuals arrive to cabinet largely by jumping off from national, executive, and non-hierarchical positions. There is a larger presence of the political arena but the private sector continues to be considerable, with about 40% of the ministers coming directly from that sphere.

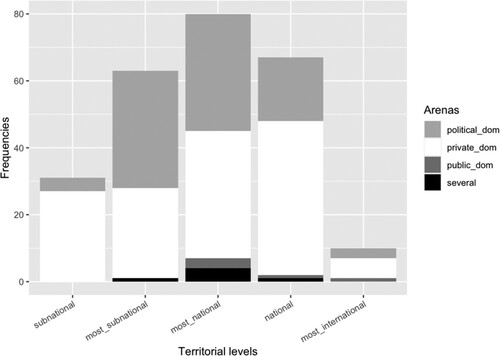

So far, our analysis has considered one attribute at the time. proposes an aggregated approach by combining levels, arenas and duration of career positions. The horizontal axis displays five categories for territorial levels, including careers that take place fully at the subnational level (subnational), fully at the national level (national), or mostly at the subnational (most_subnational), national (most_nat) or international (most_int) levels. Colours within bars indicates dominant arenas, distinguishing cases according to whether their trajectories took place predominantly at the political (pol_dom), public (pub_dom), private (priv_dom) arenas or a mix of them (aren_dom). The vertical axis represents the duration of time spent at different levels and arenas. As the figure shows, Argentina presents cases for 16 of the 20 patterns that the cross-tabulation logically allows for. Ninety percent (227 out of 251) of these cases fall within five specific career patterns:

trajectories fully spent at the subnational level, predominantly in the private arena (11%, 27 cases);

trajectories mostly spent at the subnational or the national levels, predominantly in the political arena (28% 35 + 35 cases);

trajectories mostly spent at the subnational or the national levels, predominantly in the private arena (26% 27 + 38 cases);

trajectories fully spent at the national level, predominantly in the political arena (7%, 19 cases);

trajectories fully spent at the national level, predominantly in the private arena (18%, 46 cases).

In the next section, we provide an account of the contrasting patterns between the ten administrations of the period. The differences highlight the presence of contextual factors, since the general patterns just described are not homogeneous throughout the whole period or across all governments.

On the determinants of career patterns

The literature identifies institutional features (such as separation of power and territorial organization) as the main determinants of career patterns. The basic argument is that the consolidation of such institutions leads to the consolidation of the ways in which politicians access offices, as formulated by our expectation 5.

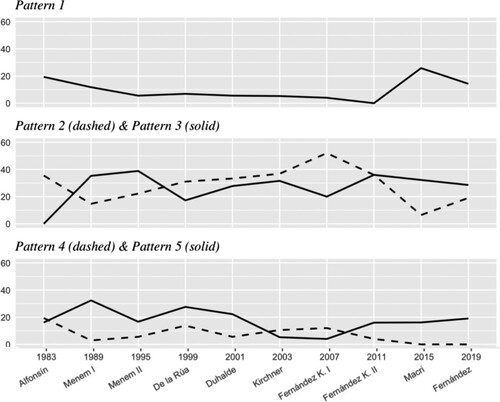

Empirically, this process should be expressed by incremental changes over time and across governments. However, the evidence from Argentina displays a different dynamic, showing high levels of volatility across all career patterns. For instance Pattern 1, representing about 11% of the cases, shows its highest figures at the beginning of the period (19% in 1983) and at its end (26% after 2015), with three different presidents and presidential parties. In turn, Pattern 2 shows the opposite dynamic, with its highest value at about the middle of the period, while Patterns 3 and 4 follow a sequence of ups and downs. Pattern 5 is the only one that shows a decreasing tendency, but only since 2007 ().

Figure 8. The five career patterns across Time (1983–2020). Pattern 1: subnational level, private arena. Pattern 2: subnational and national levels, political arena. Pattern 3: subnational and national levels, private arena. Pattern 4: national levels, political arena. Pattern 5: national levels, private arena.

Expectation 6 refers to an additional set of explanatory factors related to the role of political parties, where the level of influence is conditioned on their internal organization and control over the territory. Well-organized parties across levels and in control of candidacies and nominations are expected to produce more consolidated career patterns than less organized parties. Our study provides partial confirmation of this expectation. Following Luna et al. (Citation2021), we distinguish political parties according to their degree of coordination. As shows, more coordinated governing parties (UCR and PRO) tend to encourage career patterns exclusively placed at one level, either the subnational (18% vs 7%) or the national – both in the political arena (11% vs. 6%) and the private arena (20% vs. 17%). In contrast, less coordinated parties (Peronism) feature a predominance of career patterns that show greater movement between the subnational and the national levels (see Appendix Table 3).

Table 2. Career patterns by Government-Parties (1983–2020).

A disaggregated examination of individual dimensions is consistent with the general configuration, albeit with some nuances. The average duration of individual careers per administration remains close to the overall average duration (35 years). With regard to territorial levels, salience of the subnational component is observed during the second half of the period, with an average participation rate of 36% to 41% from 2003 – as opposed to 24% to 27% before 2003. This variation is related to the recruitment strategies of presidents Néstor Kirchner and Mauricio Macri, who had previously been state governors and who drew ministers from their local jurisdictions.

The most relevant findings on the institutional arenas are that executive experience is consistently superior to legislative experience across all governments; that there is predominance of party experience over other types of political experience in the governments led by the most coordinated party (UCR); and that nonpolitical experience is the most extensive arena across all governments, with major presence in the three right-wing administrations (Menem I and II, and Macri). Experience in previous hierarchical positions, which in general terms is quite low (21%), reaches its peak in the two governments formed to deal with the most severe institutional and socio-economic crises of the period, in 1989 and 2001 respectively (Appendix Table 3).

Conclusions

This article has examined the applicability of current analytical tools and arguments, mostly developed from research on legislative careers in consolidated parliamentary systems, to the study of pathways to national cabinet in a federal presidential regime. After distinguishing two broader meanings of political career (trajectories of politicians vs. trajectories to political positions), we proposed a disaggregated analytical framework including five definitional attributes that cut across the literature, and derived six expectations that would characterize a standard career to cabinet office in a presidential multilevel system. According to these expectations, the pathway to cabinet office is expected to be of long duration, to develop incrementally from less important to more important positions, to feature significant executive and subnational experience, and to be conditioned by institutional design and territorial organization, and mainly managed by parties.

We then examined the validity of these expectations on the full career set provided by Argentina between the 1983 transition to democracy and 2020, and found inconsistencies with the theoretical expectations. Ministers’ careers up to the cabinet can be quite long but some are extremely short (i.e. very young ministers), and the transition through previous hierarchical positions has been surprisingly low, suggesting that a cabinet position does not always appear to be among the last steps of a political career but rather can be an initial springboard for a political career. When looking exclusively at political positions, these careers show a predominance of executive over legislative arena, and significant movement from the subnational level as expected. However, when all positions held within the career trajectories are taken into account, political positions are pushed into second place behind non-political positions. Additionally, the presence of the subnational level is reinforced but with an unforeseen pattern: careers developed at the local and regional level take place mostly within the private arena. As for the determinants of career patterns, only occasionally does the empirical evidence follow the expected dynamics. Variations detected to career paths are not incremental along time; they cannot be systematically associated with the consolidation of institutional factors such as presidentialism, federalism or democracy itself.

The comparative study of political careers has made significant strides in recent years.

Our findings point to three aspects that deserve further research. The first regards a more careful and disentangled treatment of the definitional dimensions and of their possible aggregations, as a step prior to the application of parsimonious classifications. We show that these dimensions can have autonomous dynamics and run in opposite directions, challenging theoretical expectations. Typologies that are too stylized and categorize careers into just two or three options risk overlooking critical internal variations in under-institutionalized settings. In parallel, the characterization and operationalization provided here should be extended to include more fine-grained distinctions. For instance, it is critical to improve our understanding of the internal differences at the subnational level – including aspects like distance to the centre of the territorial power and to the president as cabinet formateur – to capture the incidence of factors such as hyper-centralization and concentrationist presidentialism (Malamud Citation2001) that characterize Argentina. It is also necessary to engage in a fluid dialogue with the literature on portfolio salience, to control for the implications different types of cabinet posts have for the pathways that lead to them. A key issue is dealing with different trajectories travelled by the same person: ministers who serve more than once represent both a procedural and substantial challenge that requires further development.

A second theoretical implication relates to the relevance of studying non-political positions. We show that the characterization of pathways to power changes significantly each time non-political roles are considered. This suggests that low entry barriers to appointed office, particularly in presidential systems, might foster dynamics that have not been registered by current scholarship. Future research should further analysis within this arena, differentiating between sub-domains such as organized groups, businesses, and NGOs, and applying distinctions already used for political positions such as hierarchy, sequence, and territorial level.

Finally, the evidence produced suggests the need for deeper examination of explanatory factors such as the role of individuals and crises. Institutional arrangements and political parties are fundamental, but the influence of virtue and fortune in the design of political careers may turn out to be more decisive in federal presidential systems than in other settings. In this sense, research should move towards strengthening the dialogue with the literature on the uses of presidential powers, on gender, and on exogenous factors such as economic crises and social protests.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The other cases are Brazil, Mexico, Nigeria, and the United States. Russia and South Africa are incomplete cases, the former because it is formally semi-presidential and the latter because the president is appointed and removed by the parliament.

2 We codified as ‘salient’ the high-rank positions of each arena per level. For instance, In the case of public administration and private arenas, we also consider the relevance of the organization. For instance, any position in a minor organized group were codified as ‘non-salient’ while board membership in decisive organized groups had been considered salient posts.

3 They were chosen ‘salient’ over ‘non-salient’ posts; political over non-political posts; and longer vs shorter posts.

4 While other authors (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor Robinson Citation2016) have found that public sphere in ministers’ careers represents 71%, the difference is such noticeable because we have coded Secretary positions as political. These spots usually change according to government changes. For a complementary examination of ministerial backgrounds in Argentina see Camerlo and Pérez-Liñán (Citation2015).

References

- Barragán Manjón, Mélany. 2016. “Carreras políticas en países descentralizados.” Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Salamanca.

- Borchert, Jens. 2011. “Individual Ambition and Institutional Opportunity: A Conceptual Approach to Political Careers in Multi-Level Systems.” Regional and Federal Studies 21 (2): 117–140.

- Borchert, Jens, and Klaus Stolz. 2011a. “German Political Careers: The State Level as an Arena in Its Own Right?” Regional and Federal Studies 21 (2): 205–222.

- Borchert, Jens, and Klaus Stolz. 2011b. “Introduction: Political Careers in Multi-Level Systems.” Regional and Federal Studies 21 (2): 107–115.

- Camerlo, Marcelo, and Aníbal Pérez Liñán. 2015. “The Politics of Retention: Technocrats, Partisans and Government Approval.” Comparative Politics 47 (3): 315–333.

- Camerlo, Marcelo, and Cecilia Martínez-Gallardo. 2022. “¿Por qué son importantes los ministerios importantes? Un marco de análisis.” Política y Gobierno 29 (1): 1–19.

- Cherny, Nicolás, Valentín Figueroa, and Gerardo Scherlis. 2018. “Who Nominates Legislative Candidates? The Chamber of Deputies in Argentina.” Revista SAAP 12 (2): 215–248.

- Copeland, Gary, and Cynthia Opheim. 2011. “Multi-level Political Careers in the USA: The Cases of African Americans and Women.” Regional and Federal Studies 21 (2): 141–164.

- Cotta, Maurizio, and Heinrich Best. 2008. Democratic Representation in Europe: Diversity, Change, and Convergence. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cotta, Maurizio, and Pedro Tavares de Almeida. 2008. “From Servants of the State to Elected Representatives: Public Sector Background among Members of Parliament.” In Democratic Representation in Europe: Diversity, Change, and Convergence, edited by M. Cotta, and H. Best, 51–76. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cotta, Maurizio, Pedro Tavares de Almeida, and Christophe Roux. 2004. “From Servants of the State to Elected Representatives: Public Sector Parliamentarians in Europe.” Pôle Sud 21: 101–122.

- De Luca, Miguel. 2008. “Political Recruitment and Candidate Selection in Argentina: Presidents and Governors, 1983 To 2006.” In Pathways to Power. Political Recruitment and Candidate Selection in Latin America, edited by P. Siavelis, and S. Morgenstern, 189–217. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- De Luca, Miguel, Mark P. Jones, and María Inés Tula. 2002. “Back Rooms or Ballot Boxes? Candidate Nomination in Argentina.” Comparative Political Studies 35 (4): 413–436.

- Di Capua, Roberto, Andrea Pilotti, André Mach, and Karim Lasseb. 2022. “Political Professionalization and Transformations of Political Career Patterns in Multi-Level States: The Case of Switzerland.” Regional and Federal Studies 32 (1): 95–114.

- Docherty, David. 2011. “The Canadian Political Career Structure: From Stability to Free Agency.” Regional and Federal Studies 21 (2): 185–203.

- Edinger, Michael. 2015. “Springboard or Elephants’ Graveyard: The Position of the European Parliament in the Careers of German MP.” In Political Careers in Europe. Career Patterns in Multi-Level Systems, edited by Michael Edinger, and Stefan Jahr, 77–108. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Escobar-Lemmon, Maria, and Michelle Taylor-Robinson. 2009. “Getting to the Top: Career Paths of Women in Latin American Cabinets.” Political Research Quarterly 62 (4): 685–699.

- Escobar-Lemmon, Maria, and Michelle M. Taylor-Robinson. 2016. Women in Presidential Cabinets: Power Players or Abundant Tokens?. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fiers, Stefaan, and Jo Noppe. 2015. “Level-Hopping in Belgium: A Critical Appraisal of 25 Years of Federalism (1981-2006).” In Political Careers in Europe. Career Patterns in Multi-Level Systems, edited by M. Edinger, and S. Jahr, 109–130. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Fiers, Stefaanm, and Ineke Secker. 2008. “A Career through the Party: The Recruitment of Party Politician in Parliament.” In Democratic Representation in Europe: Diversity, Change, and Convergence, edited by M. Cotta and H. Best, 136–159. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Franceschet, Susan, and Jennifer M. Piscopo. 2014. “Sustaining Gendered Practices? Power, Parties, and Elite Political Networks in Argentina.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (1): 85–110.

- Grimaldi, Selena, and Michelangelo Vercesi. 2018. “Political Careers in Multi-Level Systems: Regional Chief Executives in Italy, 1970–2015.” In Regional and Federal Studies 28 (2): 125–149.

- Jäckle, Sebastian. 2016. “Pathways to Karlsruhe: A Sequence Analysis of the Careers of German Federal Constitutional Court Judges.” German Politics 25 (1): 25–53.

- Jäckle, Sebastian, and Matthew Kerby. 2018. “Temporal Methods in Political Elite Studies.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Political Elites, edited by Heinrich Best, and John Highly, 115–133. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jahr, Stephan, and Michael Edinger. 2015. “Making Sense of Multi-Level Parliamentary Careers: An Introduction.” In Political Careers in Europe. Career Patterns in Multi-Level Systems, edited by Michael Edinger, and Stefan Jahr, 9–26. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Jones, Mark P. 2008. “The Recruitment and Selection of Legislative Candidates in Argentina.” In Pathways to Power. Political Recruitment and Candidate Selection in Latin America, edited by Peter Siavelis, and Scott Morgenstern, 41–75. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Jones, Mark P., and Wonjae Hwang. 2005. “Provincial Party Bosses: Keystone of the Argentine Congress.” In Argentine Democracy: The Politics of Institutional Weakness, edited by Steven Levitsky, and María Victoria Murillo, 115–138. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Jones, Mark P., Sebastian Saiegh, Pablo T. Spiller, and Mariano Tommasi. 2002. “Amateur Legislators - Professional Politicians: The Consequences of Party-Centered Electoral Rules in a Federal System.” American Journal of Political Science 46 (3): 656–669.

- Kikuchi, Hirokazu. 2018. Presidents Versus Federalism in the National Legislative Process. Londres: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kjær, Ulrik. 2015. “National Mandates as Stepping Stones to Europe-The Danish Experience.” In Political Careers in Europe. Career Patterns in Multi-Level Systems, edited by Michael Edinger, and Stefan Jahr, 159–178. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Lodola, Germán. 2009. “La Estructura Subnacional de Las Carreras Políticas En Argentina y Brasil.” Desarrollo Económico 49 (194): 247–286.

- Lodola, Germán. 2017. “Reclutamiento político subnacional. Composición social y carreras políticas de los gobernadores en Argentina.” Colombia Internacional 91: 85–116.

- Lo Russo, Michele, and Luca Verzichelli. 2015. “Reshaping Political Careers in Post-Transition Italy: A Synchronic Analysis.” In Political Careers in Europe. Career Patterns in Multi-Level Systems, edited by Michael Edinger, and Stefan Jahr, 27–54. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Luna, Juan, P. Rafael P, Fernando Rosenblatt Rodríguez, and Gabriel Vommaro. 2021. “Political Parties, Diminished Subtypes, and Democracy.” Party Politics 27 (2): 294–307.

- Malamud, Andrés. 2001. “Presidentialism in the Southern Cone. A Framework for Analysis”, EUI SPS Working Paper 2001/01, European University Institute, Florence.

- Micozzi, Juan Pablo. 2014. “From House to Home: Strategic Bill Drafting in Multilevel Systems with Non-Static Ambition.” Journal of Legislative Studies 20 (3): 265–284.

- Nicholls, Keith. 1991. “The Dynamics of National Executive Service: Ambition Theory and the Careers of Presidential Cabinet Members.” Western Political Quarterly 44 (1): 149–172.

- Pedersen, Mogens, and Ulrik Kjaer. 2008. “The Geographical Dimension of Parliamentary Recruitment - Among Native Sons and Parachutists.” In Democratic Representation in Europe: Diversity, Change, and Convergence, edited by M. Cotta, and H. Best, 160–192. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schlesinger, J. 1966. Ambition and Politics. Chicago: Rand McNelly.

- Siavelis, Peter, and Scott Morgenstern. 2008. Pathways to Power. Political Recruitment and Candidate Selection in Latin America, edited by Peter Siavelis, and Scott Morgenstern. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Sieberer, Ulrich, and Wolfgang C. Müller. 2017. “Aiming Higher: The Consequences of Progressive Ambition among MPs in European Parliaments.” European Political Science Review 9 (1): 27–50.

- Stefan, Laurentiu. 2015. “Political Careers Between Local and National Offices: The Example of Romania.” In Political Careers in Europe. Career Patterns in Multi-Level Systems, edited by Michael Edinger, and Stefan Jahr, 55–76. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Stolz, Klaus. 2003. “Moving up, Moving Down: Political Careers Across Territorial Levels.” European Journal of Political Research 42: 197–222.

- Stolz, Klaus. 2015. “Legislative Careers in a Multi-Level Europe.” In Political Careers in Europe. Career Patterns in Multi-Level Systems, edited by Michael Edinger, and Stefan Jahr, 179–204. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Vercesi, Michelangelo. 2018. “Approaches and Lessons in Political Career Research: Babel or Pieces of Patchwork?” Revista Española de Ciencia Política 48: 183–206.