ABSTRACT

The media has been repeatedly demonstrated to have a large effect on voting behaviour and voter information worldwide, and to be crucial in the establishment of collective identities. Relatively unexplored in the field of regional politics are the effects of media on substate party system divergence and non-statewide party success. This article takes Europe as its focus and demonstrates how strongly regionalized media environments contribute to the development of distinctive party systems at the regional level. I argue that the effects of media works chiefly through the establishment of a ‘banal regionalism’ and by increasing voter information, thereby boosting issues traditionally associated with regionalist success such as socio-cultural distinctiveness and regional autonomy. The paper demonstrates this through a regression analysis of 69 European ‘Small Worlds’ and an illustrative case study of the United Kingdom.

Introduction

Many factors that lead to the distinctiveness of some substate party systems – such as language, culture, autonomy and economics – have been extensively explored. I contend here that the strength of regional media organizations is a missing piece of the puzzle. Regional media organization is essential for identity formation/consolidation and the provision of voter information, both of which boost the vote shares of non-statewide parties (NSWP) and raise the salience of the territorial cleavage. The article argues that regional media supports two key pillars of NSWP support discussed in the literature – autonomy and identity – and can be influential in deciding whether these factors raise NSWP support. To test this hypothesis, I therefore examine the interaction between independent regional media environments and the success of NSWP. The study tests the relationship using a uniquely comprehensive dataset of ‘Small World’ electoral results and a novel media-strength metric. It then explores the results through an illustrative case study of the United Kingdom.

Theoretical context

This paper uses the concept of the ‘Small World’ to refer to a substate region with a distinctive party system marked by the presence of non-statewide parties (NSWP) and prominent territorial cleavages. This definition is owed to Hepburn (Citation2010), who states that these regions owe their distinctiveness to the existence of a strong territorial identity supported by regional civic institutions, a distinct political culture and the successful political mobilization of territorial interests by NSWP.Footnote1 Small worlds vary considerably in terms of the extent of their divergence from statewide party systems, and many factors have been cited in the literature which would explain these differences in support for NSWP or the salience of territorial cleavages. I contend here that while these factors are undoubtedly important in explaining this divergence, a strong regional media environment serves as a moderator that can straighten the effect of these structural factors.

Many scholars have focused on economic development in determining support for NSWP, such as Gehring and Schneider (Citation2020). Fitjar (Citation2010), for instance, contends that regionalist mobilisation is based on the extent of regional resources and economic development. In addition, Massetti and Schakel (Citation2015) point out that in affluent regions, regionalists may be accepting of fiscal federalism which removes obligations to transfer resources. However, regionalist mobilisation in these circumstances also depends – as Fitjar (Citation2010) points out – on underlying socio-cultural distinctiveness, which serves as a necessary but not sufficient cause of mobilisation. Regional electorates would need to see themselves as sufficiently distinct to opt for parties that articulate their grievances in regional terms, although they will not automatically vote on this cleavage. As argued here, media can very often be crucial in consolidating this identity and activating the cleavage.

Two of the most discussed factors in the literature for explaining regional party system distinctiveness are regional autonomy and socio-cultural distinctiveness. It is the argument of this paper that while these two factors are indeed some of the most important, they are strengthened by regional media. Regional autonomy looms large in the literature. Tatham and Mbaye, for instance, contend that ‘the creation of new electoral arenas and the growing powers and autonomy [of regions] … has gradually redrawn the electoral landscape’ in Europe (Tatham and Mbaye Citation2018, 664). Moreover, Schakel (Citation2013) demonstrates that elections in regions with advanced autonomy display weaker second-order effects. Moreover, Hamman (Citation1999) charts the development of varied party systems in Spain since the introduction of the Autonomous Communities. In general, we can observe that regional parties gain better results in regional elections than in other election types. Massetti and Schakel's outstanding 2015 study, for instance, finds differentiated effects of decentralization on both regionalist and secessionist parties and at regional and national levels. This is somewhat contrary to the findings of Brancati (Citation2008), who rather finds that autonomy boosts NSWP support at all levels.

Many explanations for why this is the case have been put forward. Brancati (Citation2008) demonstrated that stronger performance of NSWP in regional elections has a spillover effect to other levels. Dalle Mulle (Citation2017) attributes this impact to autonomy encouraging issue diversification; and thus undermining statewide parties accommodationist strategies. He also argues that decentralisation improves the opportunity structure for secessionist parties, allowing them to use regional institutions as platforms for nation-building and normalising substate nationalism (Dalle Mulle Citation2017). In addition, Morgenstern et al provide some evidence that federalism, especially when combined with ethnic diversity, has a negative effect on party system nationalization (Morgenstern, Swindle, and Castagnola Citation2009).

However, while it seems likely that regional autonomous institutions boost NSWP, there are cases where high levels of regional autonomy fail to produce strong NSWP. Some of these can be explained with reference to wealth (e.g. Sardinia), but in others the lack of strong NSWP is unexpected considering other features. I argue here that the possession of a regional media is an important element of how autonomy boosts support for NSWP. Autonomy is often credited with further ‘nationalizing’ regions with distinct socio-cultural environments, and also with providing more hospitable elections for NSWP (where more focus will be on regional issues that they will be the most credible on). I argue that these effects cannot be explained without the presence of regional media to inform voters about regional politics. The Welsh case in particular reveals that simply holding regional elections does not mean voters will pay attention to them, or opt for NSWP over statewide parties (Scully and Larner Citation2017).

How then do regional media environments influence regional voting? The first central mechanism is through increasing voter information about regional politics. This fits with existing studies of the effects of media on voter information, such as that of Weaver (Citation1996), which demonstrates how voters gather much of their information on parties and issues from media news sources. Lippmann’s (Citation2008) work is also foundational here. He argues that the mass media shapes and creates a citizen’s political world. If these news sources are predominantly regionally-based, it would make sense that they would be predominantly informing the public of regional parties and issues and creating a regionally-based political world where NSWP would benefit. A range of subsequent studies have demonstrated this idea that the media is a channel for voter information and can serve to create more informed voters (including boosting turnout). For instance, Piolatto and Schuett’s (Citation2015) study suggests media can be responsible for increases in turnout, and Prat and Stömberg’s work on Sweden (Citation2005) found that the media increases voter knowledge of politics. Moreover, at the local level Baekgaard et al. (Citation2014) demonstrate that local media coverage that provides politically relevant information can increase local election turnout.

In addition there are a few studies of the regional level which display the impact of media and media environments on political information propagation and election outcomes, although not nearly as many as there should be and little in the way of large-scale comparative analysis. Those that do support the argument here that regional media is crucial for issue diversification and increases the salience of regional issues. Agnew (Citation1995), for instance, demonstrates how Lega Nord suffered in the 1990s compared to statewide centre-right parties, who were able to effectively utilize statewide media. Given its lack of a distinctive media environment compared to other areas of the UK, Wales has received some attention in this regard. Thomas, Cushion, and Jewell (Citation2004), focus on the 2003 National Assembly for Wales election, which was marked by low turnout. They attribute this partially to Wales’ dearth of indigenous media, which damaged the functioning of the elections. The dominant framing of the elections in the national media, they say, was one of apathy, which reinforced the lack of participation and was inaccurately turned into a story around dissatisfaction with devolution. And more recently, Jones (Citation2017), examines the outcome of the 2016 EU membership referendum in Wales, stating the overall Welsh vote to leave was at least partially attributable to the lack of distinctive media and the dominance of leave-supporting English media. She compares this with the very different public debates in more media-rich Scotland and Northern Ireland, which produced different results.

The second major mechanism is through the consolidation of regional identity and other distinctive socio-cultural factors, another major focus of the literature on regionalism. As Friend notes, Western European states are in general not nation states in the strictest sense, and are usually composed of one or more historic national communities (Friend Citation2012). Friend hypothesizes that these national communities are maintained by a number of ‘carriers of identity,’ such as language, religion and historical institutions and events. These regions, and others with purely regional identities, have the ability to act as magnets for the formation of arenas of political competition influenced by these identities. De Winter’s analysis (1998) also claims strong regional identities create a ‘general positive climate towards parties that most strongly express [a] … sub-state identity’ (De Winter and Trusan Citation1998, pg. 217). Massetti (Citation2009), also identifies an ‘ethnic divide’ as being crucial for strong peripheral nationalist parties, and Van Houten (Citation2007) finds that distinct ethno-national identities are necessary for secessionism. In Catalonia, Dalle Mulle and Serrano find that the lack of recognition for the Catalan nation features as a crucial part of the case for independence. On the other hand, they explain, the unchallenged nature of Scottish nationhood means that arguments for secessionism tend to be more economic and about which form of government would be best for Scotland (Dalle Mulle and Serrano Citation2019).

As Shair-Rosenfield et al. point out, language in particular should be a powerful booster of regional identity, given its high visibility and ability to ‘bind a group in shared communication and meaning’ (Shair-Rosenfield et al. Citation2021, pg. 80). Their study confirms a relationship between regional language use and regional autonomy arrangements, supposing that linguistic minority groups will seek autonomy in order to secure the place of a regional language in public life. Furthermore, studies of single cases have shown that regional language speakers are often more likely to support substate-nationalist parties (Lynch Citation1995; Dowling Citation2013). In Wales, for instance, nationalist parties take most of their votes from Welsh-speaking areas (Lynch Citation1995) and Catalan nationalist parties are also much stronger in the Catalan-speaking countryside than in the predominantly Castilian-speaking Barcelona metropolitan area (Dowling Citation2013). Again, something which seems to be missing from discussions around language is the role of media in increasing the visibility, status and use of the language. Voters who only view their language as a low-status dialect and not as something in the public realm are less likely to be mobilized by language issues, and media would play an important role in institutionalizing or deinstitutionalizing language given its reach.

Compared to other factors such as history, language and institutions, less attention is given to the importance of media as a carrier of regional identity. This is very surprising given various empirical cases where independent regional media and strong NSWP coincide. In both the UK and Spain, territories which have more region-specific media consumption exhibit greater support for NSWP than others. There have been a few smaller-scale studies of regional media in Europe. Paasi (Citation2013), for instance, claims that regional media aids in the maintenance of regional identities – something supported by Terribas i Sala’s (Citation1994) comparative study of Scotland and Catalonia (which shows how regional media acts to preserve separate cultural identities) and Fraser’s (Citation2008) study of Scotland which argues that the media has been crucial in maintaining Scottish national identity. Tobeña (Citation2017) looks at the Catalan case, suggesting that the distinctive Catalan regional media environment has contributed to growing support for secessionism in the 2010s. There has not been, however, an attempt to formulate a general theory of how this process might work.

Central to this process, I believe, is Michael Billig’s concept of ‘banal nationalism’ (1995). This concept – which has gone on to be enormously influential in the field of nationalism (see Slavtcheva-Petkova (Citation2014), Antonsich (Citation2016) and Szulc (Citation2017)), details the everyday, ordinary nationalist actions and signifiers which help define the boundaries of nations and reinforce national belonging. These things are often routine, such as the labelling of food items as products of the country, sporting events, or references to fellow nationals as ‘we’ in newspapers (Billing Citation1995). Mass media, as something widely consumed by society, inevitably plays a crucial role in reinforcing national belonging (Slavtcheva-Petkova Citation2014). Rosie et al. (Citation2006) actually seek to apply Billing's ideas to the Scottish and Welsh media, demonstrating how the media can define national boundaries, albeit in a more multifaceted and ambiguous way in multi-national states. This article will argue that media is an important way of consolidating regional identities through its role in consolidating ‘banal regionalism’ or ‘sub-state banal nationalism’ – consolidating and defining a distinct regional identity which will thereafter impact voting behaviour.

Considering the existing literature and observations of empirical cases, this paper hypothesises that the media's impact on NSWP success would chiefly be twofold. Firstly, distinctive regional media environments help to reinforce a regional or regional-national identity by contributing to ‘banal regionalism’ which aids in creating collective regional-national identities, distinguishing the region from the rest of the state and weakening cross-state ties. Regional media should also solidify and preserve regional cultural distinctiveness, for instance by broadcasting in regional languages. Voters in this situation would be more likely to then cast their votes for parties that promote or defend the interests of this national unit – or are at least unique to it – rather than those with a statewide base.

Secondly, regional media should serve to increase voter knowledge of regional politics, issues and parties, and thus overcome one of the major advantages that statewide parties have. Statewide parties and their politicians are generally much more widely known than regional equivalents due to the national nature of media organisations generally. Strong regionalised media environments would negate this and give a boost to regional actors by raising their visibility, as well as promoting issue diversification into areas favourable to regionalist parties. The theoretical logic of these two processes seems sound, and allow us to state the following hypothesis as to the effect of regional media consumption on NSWP support:

Higher levels of regional media consumption will result in greater success for NSWP

This paper attempts to test this hypothesis through a statistical analysis of the correlation between media consumption and NSWP party support, and then by attempting to draw out some of the causal processes through an illustrative case study of the United Kingdom. The goal of this analysis is to point to important processes which are currently under-explored and to establish a link between the two. However, further research would be needed to firmly establish the causal mechanisms theorized above. The ‘banal regionalism’ mechanism could be studied by examining the presence of banal nationalism markers in the media and studying the relationship between NSWP supporters and those who consume media with the most banal regionalism markers. The role of the media in voter information and issue diversification could be explored through a comparison of the salience of various issues and changes in media consumption, as well as survey work testing voter knowledge in relation to the media they consume.

Data and method

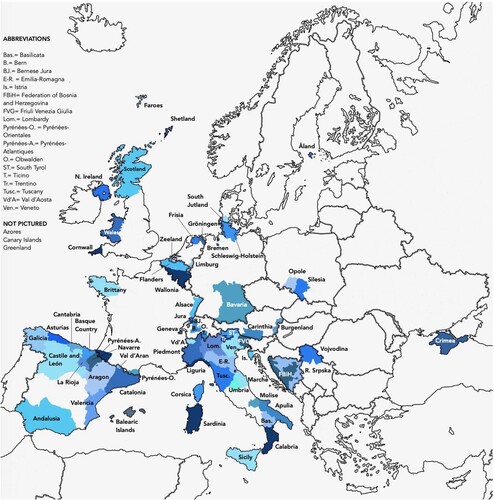

To test this hypothesis, OLS models are run on a new and unique cross-national dataset of European Small Worlds. This covers 17 countries and 69 sub-state regions from 1980 to 2019. Operationally, a NSWP has been defined as a party which competes only in certain areas of the state. It does not need to have a specifically regionalist agenda. For regions to be included, at least one NSWP must have received over 1 per cent of the vote in at least 3 elections at the same governmental level (or at least 2 elections across all levels) in that decade. This should exclude ephemeral parties which may achieve sudden success in particular elections but have no long-term effect on the party system. Secessionist parties – defined as those who explicitlyFootnote2 declare themselves to be in favour of breaking away from the existing sovereign stateFootnote3 – were also coded for the same elections as the wider NSWP as a robustness test (given the more extreme political programmes of these parties). While only selecting regions where NSWP are present may at first glance appear like selection on the dependent variable, the purpose of the study is to measure variation across such regions where these parties are a key component of the party system, and the dataset includes all of these regions, including those with very minimal support for NSWP. The regions included can be found in appendix A. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at (https://drjonathanparker2.wordpress.com/data/) ().

The region must be an integral part of a state, not a dependent territory or similar arrangement, and must have representation in the statewide legislature so that it may theoretically be part of the same party system. I have generally stuck quite rigidly to the rule that the territory must be within the geographic bounds of Europe, in order to control for background factors and ensure similar cultural and socio-economic environments. I have, however, made a number of small exceptions, and have included the Portuguese Autonomous Region of the Azores, the Danish constituent country of Greenland and the Spanish autonomies of the Canaries, Ceuta and Melilla due to their political, cultural and economic connections to Europe.

The dataset starts in 1980 and ends in 2019, resulting in the inclusion of 1,929 elections across local, regional, national and European levels. The 1980s were selected as the starting point because it is in the 1970s that many regionalist movements first began making a significant impact, and from 1980 onwards consistent and comparable data can be gathered for almost all regions. If a region does not meet the criteria for a Small World (laid out above) in a certain decade, it is not included for that period. Two dependent variables are deployed to test the research questions. NSWP_% gives, for each election (local, regional, national and European and some sui generisFootnote4 contests) throughout the period, the combined percentage support for all NSWP winning over 1 per cent of the vote. PIP_% measures support for secessionist parties only on the same basis.

For the primary independent variable, regional media consumption, a novel variable - media - was created. This variable measures the extent to which the region has a media environment distinct from the state as a whole. While ideally I would have collected viewing and listening figures for regional television and radio stations, and circulation figures for regional press, this data is extremely hard to come by and it would be impossible to construct a continent-wide comparative dataset of them. I have instead constructed a variable wherein each region scores between 1 and 6, with 6 being the most independent media environments. Regions are scored either 0, 1 or 2 in each of the categories of TV, radio and newspapers, the scoring of which is explained below and expanded upon in Appendix B, and the values for each are summed to give the final variable. While exact figures could not be acquired, it was in almost all cases possible to make these judgements based on existing data and the literature. A list of scores for each region for the 2010–2019 period is included, to give an idea scoring system, is included in , although it should be noted that the values used in the regression were for each individual election year.

No regional TV or radio station or newspapers exist (bodies must cover the whole region, local media is exempt)

A regional TV or radio station or newspaper exists

Regional TV Radio and newspapers account for majority of media consumption in the region.

Table 1. Media scores for the 2010–2019 period by region.

A third variable of significance is that of regional identity strength (Id_strength). This has been gathered from a wide variety of public opinion surveys and averaged out across the decade to improve robustness. If possible, surveys asking the Linz-Moreno question are used, with answers for ‘only regional,’ ‘more regional than national’ and ‘equally regional and national’ combined to create an overall figure of regional identification. If such surveys are sparse, other polling which asks about regional identity has been used. This variable has been included given that the ability of regional media to consolidate regional identity through banal regionalism is a key causal mechanism hypothesized to link regional media strength to NSWP support. Identity strength is used as an independent variable for regressions testing NSWP and secessionist support, then as a dependent variable to examine its correlation with regional media consumption.

Alongside this, data for many other independent variables were created as controls. These variables reflect the literature on regionalist parties, regional party systems and party system formation more generally. The details of these variables are laid out in below. These variables include economic factors such as regional economy (represented by regional GDP per capita as a percentage of the national figures), regional autonomy (represented by a binary autonomy variable and a measure of length of time since the first autonomous election). Socio-cultural factors relating to the ‘carriers of identity’ discussed above – such as language use – are included also. In addition, regional history, in accordance with Friend (Citation2012) is included through a variable measuring a history of regional independence. Furthermore, several contextual factors were also included in the regression, such as election type,Footnote5 distance from the statewide capital and regional population. A summary of these variables can be found in below.

Table 2. Description of the independent variables.

Three models were tested, initially with the share of the vote for NSWP in general as the dependent variable, then with the support for secessionist parties as the dependent variable, followed by models with regional identity as the dependent variable. The models were tested for signs of autocorrelation, multicollinearity and heteroskedasticity. Durbin-Watson scores for all models revealed significant autocorrelation, which was likely given the time-series nature of the data. To account for this, a lagged version of the dependent variable was also included in both models. Moreover, the distribution of the data is heteroskedastic in both cases. To overcome this problem robust standard errors were specified, clustered by region. However, none of the Variation Inflation Factor (VIF) scores for each variable were above 5, indicating no evidence of multicollinearity.

In addition, several steps were taken to improve the robustness of the results. State-specific factors could be seen to influence results, given that the data is nested within states. For this reason country-dummies were added, following the precedent of Fitjar (Citation2010). Region-level dummies were considered but resulted in very high VIF scores and many variables dropped from the model because of this. To further improve the robustness of the models, each model has been run a second time with the Spanish observations removed, and a third time without Italian observations. Spanish cases made up 33.0% of the total observations, and Italy the next highest with 19.5%, meaning that country specific factors in either country may be influencing the overall results. The models without the Spanish cases was multi-collinear with regards to the European and sui generis election types, so these variables were excluded from the analysis in this model. The same was true for local elections in the general and Italy-excluded models.

Results and discussion

The regression results reveal significant support for the hypotheses. As can be observed in , and , the regional media variable is robustly, positively and significantly correlated with both dependent variables; although more so with NSWP support as a whole than with secessionist party voting. For NSWP support media consumption remains significant for all three models. In the general model with all observations, the variable is highly statistically significant with a p value of 0.009. Crucially, this variable is significantly related to an increase in the dependent variable whereas other widely hypothesised variables such as language use, regional identity and histories of independence are not. Among the statistically significant variables from the literature, media is joined only by the length of time the region has possessed regional autonomy and GDP per capita figures (which isn’t robustly significant across all variables). In addition, the variable has a high coefficient value of 0.18, indicating a significant increase in vote shares of nearly 18 per cent on average when consumption of regional media increases by one unit (so by one band on the media clarification). While autonomy length does create a slightly larger increase in NSWP voting, this result still confirms a strong relationship with media. The statistical significance is somewhat less when the Italian observations are removed, although the direction and magnitude of the effect remains similar.

Table 3. Results of Linear Regressions using the dependent variables NSWP_%, PIP% and Id_strength with all observations.

Table 4. Results of Linear Regressions using the dependent variables NSWP_%, PIP% and Id_strength with Italian observations removed.

Table 5. Results of Linear Regressions using the dependent variables NSWP_% and PIP% with Spanish observations removed.

The results indicate that the effects of media consumption on the secessionist party sub-variable are much less significant, although there may still be something of a relationship. Here the strength of regional identity is the only variable that is consistently statistically significant across all models, although its effect on levels of secessionist voting is rather small (0.06 – although this increases to a much more substantial 0.22 when Spain is omitted). Media strength is statistically significant here for all observations (0.009) and with the Spanish observations removed (0.016), but not with Italy omitted. As with the weaker significance for NSWP on this model, this is likely due to the dominance of Spanish cases here, where media variance is much less dramatic than elsewhere. Even in the full model, where the variable is significantly correlated with secessionist voting, the magnitude of its impact on the dependent variable is much less than media consumption had on support for NSWP as a whole (0.05 – although it must be cautioned that all variables have much lower coefficients in this model). As secessionist voters are typically more extreme and ideologically committed than NSWP voters as a whole, it would perhaps be less likely that they would be influenced by greater levels of voter information. However, we would likely expect that media boosting regional identity would be a very big factor here. Indeed this seems to be reflected in the fact that secessionist voting is here positively and significantly correlated with regional identity.

In addition, the regressions also reveal support for the idea of a linkage between regional media and regional identity – one of the chief hypothesised causal mechanisms linking media strength to NSWP voting. Media is significantly and positively correlated with increases in regional identification, with a p value of 0.005 and a coefficient estimate of 0.056, a greater value than most other independent variables. The correlation is robustly significant with Spanish and Italian observations removed. This indicates that strong regional media are found in regions with powerful regional identities. Again, we cannot be entirely sure of the direction of causality here, but as I explained below, it would seem likely that media at least contributes to growth or maintenance of regional sentiment.

While media is strongly linked to both NSWP voting as a whole and secessionist support in particular, regional identity strength is only significantly predictive of secessionist party support. In many ways this is logical – we are already sampling only regions that have NSWP and have stronger regional identities than regions which don’t, and only those regions with the strongest identities would contemplate secession. We know from the work of Brancati (Citation2008), for instance, that while distinct identities are crucial for the emergence of regionalist parties in the first place, strength of identity alone seems to be a necessary but not a sufficient cause of regionalist party strength. To enable this regional identity to become a variable influencing voting behaviour, this article has argued that a strong regional media to promote banal regionalism needs to be present. The results provide some support for this idea, especially for secessionist parties, who appear to be more influenced by identity factors.

However, while regional media is positively and significantly correlated to territorial identification and secessionist party voting, this does not assure us that the relationship of causality is in the direction hypothesised. It only strongly suggests that the three may be connected, although I detail below why I believe the direction of causality to be the way I predict. The first possibility is a straightforward causal pathway as hypothesised; regional media leads to regional identity leads to voting for secessionist parties. A second possibility is that strong regional identities cause both media strength and secessionist support. A third, but less likely, pathway is that secessionist parties are creating strong regional identities and regional media. The most probable pathway is a more nuanced one, where regional media supports, accentuates, and consolidates regional identities which leads to more secessionist voting. To a more limited extent, the success of secessionist parties as a result of this could lead to a feedback loop, and increase regional media consumption and production further. The reason why I believe this is the most likely scenario will be elucidated through the below comparison of Scotland and Wales.

Supporting this, we can see that regional media is correlated with other factors thought to influence NSWP voting. shows the strength of regional media compared with average scores for other factors. The data was distinctly clustered, with a plurality of regions scoring a ‘3’ indicating a mid-level of regional media consumption (in most cases, they possessed all three of the coded-for attributes but none of them were majority-consumed). Elections which occurred in cases which scored a 3 made up 803 of the 1,929 observations (41.6%). Because of this the rest of the observations have been clustered into two groups of 500–600 observations each; a lower category making up around 27.6% of observations (those scoring 2 or less), and an upper category (4-6) of those cases with well-developed regional media. As we can see, the main difference is between the highest category and the other two, with the medium and low categories not being significantly differentiated from each other. Those regions with significantly popular regional media have much higher levels of NSWP voting, much more widely spoken regional languages and tend to be somewhat wealthier and possess stronger regional identities on average than those with weaker media environments. Crucially, secessionist parties are almost entirely concentrated in those regions with the highest levels of media consumption.

Table 6. Comparison of regional media strength with other variables, showing the average values of variables for each media category.

Again, while there is obviously then a strong correlation between regional media strength and other regional attributes traditionally thought to boost NSWP, what cannot be inferred from the quantitative data is the direction of the relationship, or whether there is a ‘loop’ like self-reinforcing effect occurring. This can be demonstrated when looking at regional language. The regions scoring a ‘6’ (the highest value) on the language variable in the dataset correspond quite closely with the regions with universally-spoken regional languages. While in some cases regional languages may force the creation of regional media, in others regional media can raise the profile and prestige of regional languages. There are in the dataset a selection of regions with high numbers of speakers but low media scores, which generally also have fairly weak NSWP. We can also see this double interaction with regards to regional autonomy, with those elections with regional media and regional elections getting a double boost as regional media cover regional elections and cement the region as a distinct political space. But in addition, regional autonomous governments often establish regional media (for instance in Catalonia after the transition), or encourage its creation or spread by making much of what the news media would report on regionally-based.

Illustrative case study

The situation in the United Kingdom helps illustrate the argument put forward here and provides some indicative evidence of the direction of causality. The three largest small worlds in the state (Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) all have diverging levels of media differentiation from the UK media environment that correlate with differing levels of support for both NSWP and pro-independence sentiment. This section will compare Scotland and Wales, two constituent countries of the UK that are both ‘Small Worlds.’ Whereas Scotland has a fairly independent media and high levels of NSWP voting and secessionist sentiment, Wales lags behind on all three of these metrics.

As indicates, with a score of 2, Wales doesn’t have a particularly distinctive media environment, and media consumption is almost identical to England. There are no all-Wales regional daily newspapersFootnote6 and while regional radio has large listenership, it is usually overshadowed by statewide stations. Wales has rarely been treated as a single unit for TV programming by statewide channels, and has often been more attached to adjacent English regions (Jones Citation2017). While there is a regional TV channel (S4C, established in 1982), this broadcasts solely in the Welsh language, which is only spoken by around 20-30% of the population. The country does not have English language channels of its own (Scully and Larner Citation2017). Wales also has much lower levels of NSWP voting, with an average level of support at 21.5% for the 2010s, and support for secession from the UK around 15-20 percentage points lower than in Scotland. British media pays little attention to Welsh politics, and in general Welsh party leaders are much less well known than the UK leaders (Welsh Election Study, 2016). The principal NSWP in Wales, Plaid Cymru, only really receives significant amounts of media attention at election time. Data from elections surveys shows low levels of public knowledge about devolved politics, with 40% of respondents in a 2016 post-election study erroneously believing Plaid Cymru had been in the Welsh government for the previous 5 years (Welsh Election Study, 2016).

Table 7. Comparison of Scotland and Wales on both media and other relevant variables.

Scotland has a much more distinctive media environment, with a Media score of 4 and a 2010s average support for NSWP of 40.7%. Support for secession is much more widespread, at nearly half of the population. While Scotland’s media environment is linked to that of the rest of the UK, it has long been distinct in terms of print media especially, with a wide variety of widely read Scottish titles being produced such as The Herald, The Scotsman and the Daily Record. Most of the UK press also produces separate Scottish editions of their papers, which focus on regional political news and sometimes take diverging editorial lines from the English editions. The region is less divergent in terms of Radio and Television consumption, but even here popular regional channels exist and regional versions of UK channels produce Scotland-specific content, in particular news coverage. This assists in the production of a specifically Scottish media (especially news) environment, where Scottish politics, parties and leaders receive large amounts of attention and are highly visible to the public (Law Citation2001).

The differences in media consumption also correlate quite closely with the salience of territorial cleavages. Support for self-government and secession has always been much higher in Scotland than in Wales. I would argue, as Law (Citation2001), Rosie et al. (Citation2006), Petersoo (Citation2007) and Rosie and Petersoo (Citation2009) do, that the independent Scottish media environment provides enough collective identity and a sense of a distinctive Scottish politics trough ‘banal nationalism’ that Scottish national consciousness is strengthened to such a degree that independence and autonomy can be contemplated. In Wales, the integration into the English media market does nothing to support the sense that Wales is a distinct polity in which self-government should lie. For the Scots, on the other hand, the media aids (along with distinct institutions) the sense of Scotland as a place apart. And while Scottish newspapers have never been falling over themselves to endorse independence, the media does represent a place for ideas about the nation and its proper form of government to be propagated and reach new audiences, in a way in which they cannot in Wales.

Media support for secessionism and the Scottish National Party (SNP), the largest NSWP, has been fairly muted in Scotland, although some Scottish papers, such as the Scottish Sun, have been explicit in their support for the party at times. However, it can be argued that the existence of Scottish media, and their contribution, along with other factors, to forging a distinctive Scottish national community, would shape voter choice in favour of ‘national’ options such as voting for the SNP or affirmative votes in referenda on devolution or independence. Moreover, it has been noted by Williams (Citation2000), amongst others, that voting for Welsh nationalist parties and positive votes in the various devolution referenda (1979, 1999, 2011) seem to be linked to the accessibility of Welsh media. These are much more available in the Welsh-speaking areas of the West and to a lesser extent in the south Wales valleys, where support for these movements is concentrated. It is in these areas that a Welsh national identity reinforced by distinct media consumption (see below) is much more of a reality, leading to voting for ‘national’ projects. Eastern areas have much less exposure to these media and remain hostile terrain for Welsh nationalism.

There are also other ways in which the media in both countries also serves as an incubator of national identity. While Scotland lacks the linguistic distinctiveness of Wales, its identity is solidified by a national media, and the very existence of this media serves as a marker that Scotland is a different country than England. Moreover, a separate Scottish nation is clearly the legitimating factor in the existence of this media; and Scottish media gives coverage to Scottish socio-cultural issues (Law Citation2001). In Wales, this media is much weaker and does not serve to ‘carry’ a unified national identity to the same degree, relegating ‘Welshness’ to the local and solidifying Britishness as the national frame (Thomas Citation2006). The lack of regional media but a proliferation of local and statewide media also does nothing to overcome the deep regional divides in Wales (created by economy, history, transport, geography and government policy) and forge a unified national community in a way that Scottish media has unified, for instance, the Lowlands and Highlands of Scotland into a relatively homogenous nation (Jones Citation2017). True, Wales has also historically lacked the national institutions that Scotland has possessed, but then many regions of Europe lack these and yet have produced strong secessionist movements, such as the Basque Country, Greenland and South Tyrol. Media could have played a role in unifying the region, and, combined with the establishment of devolution, created the idea of a distinctive Welsh polity rather than a vague cultural area who’s component parts were more closely connected to adjacent English regions.

The one way in which media does serve as a carrier of identity in Wales and impact voting behaviour is through the Welsh language. While English language media in Wales tends to be dominated by English sources, a national Welsh language media industry does exist, consisting of television channels, radio and publications. We can see here the circular, self-reinforcing, relationship of media to other factors. We know that Plaid Cymru’s voting base is overwhelmingly welsh-speakers. The areas of its electoral strength corresponds closely with the areas of the language’s strength, and post election-polling reveals that fluent language speakers are the party’s biggest supporters (Welsh Election Study, 2016). The existence of Welsh-language media undeniably assists the language, giving it a much more prominent role in public life and in voters’ personal lives, as well as propagating the language outside of its main areas. However, due to the size of the Welsh-speaking population, this media strength has limited impact, mainly serving instead to unify language speakers with Welsh national identity. As a consequence, Welsh speakers are much more likely to be exposed to the nation-building attributes of the Welsh media, and much more likely to identify strongly as Welsh and to vote for Welsh nationalist parties. Outside of this community, however, these processes are limited.

Conclusions

The analysis presented here is to some extent exploratory and should mark the beginning of a wider investigation into the linkage between regional media and substate party systems. It does, however, begin to show two key and interlinked ways in which distinctive regional media environments could contribute to the success of NSWP and in particular secessionist parties. Firstly, through the widely recognized ways in which media increases voter information about politics and impacts voter choice. At the regional level, this manifests itself in the creation of electorates informed and aware of regional issues and parties, and perhaps made more inclined to vote for them electorally. It may also be that regional media directly endorses regionalist parties and causes, but more important is that by encouraging and consolidating a substate national identity media encourages voting for these forces.

This leads us to the second way in which media contributes, that of a ‘carrier of identity.’ Through the use of ‘banal nationalism’ and ‘banal regionalism’ it can set the boundaries of the regional polity and mark it out as a separate polity. It can also be used to reinforce the effects of regional languages and regional autonomous institutions, providing coverage of them and facilitating their own effects on the electorate.

The paper has raised but not entirely settled the question of the direction of causality. In one scenario regional media is leading to the creation of stronger regional identities and focusing more on regional news, leading to higher levels of voting for regionalist parties (as hypothesised). On the other hand, a second scenario may be that regionalist parties and sentiment are gaining ground and therefore new regional media is established to meet this demand. Both are possible and both occur in the cases we have discussed. For instance, not until the SNP gained control of the Scottish government did the BBC consider a Scottish-only channel, and S4C was established largely as a result of nationalist pressure. However, I believe the evidence points – although not without caveats and some uncertainty – to the hypothesised scenario being more significant. Across the board in Europe, we can see that regional media scores rarely change over the years, and do not tend to change in relation to rises in support for NSWP. The main cases of dramatic change are in the Spanish autonomous communities, where new TV channels were rapidly established after the transition to democracy and the establishment of the state of autonomies. In general few regions change their score and in even fewer does this follow an increase in the support for NSWP. In addition, the changes that do occur then tend to be rises from very low scores to middling ones.

This would point rather to a situation in which regionalist parties have the best chances of finding success in regions which have district regional media environments, rather than one where the media environment is rapidly changing to take into account new regionalist sentiment. Changes forced by regionalist progress may compound and consolidate distinct regional media environments, or may effect minor increases in their distinctiveness, but they do not seem likely to create them. In the Scottish and Welsh cases, for instance, apart from the activist-driven creation of S4C the media market has not regionalised in an any significant way in response to the somewhat increased popularity of Plaid Cymru. And while some new developments in the past decade have increased the distinctness of the Scottish media space, this has not been enough to change its score and the independent press and television services long predate the SNP’s increase in popularity. So while we cannot determine the causal relationship for certain, the direction of travel looks more likely to be that predicted by the hypotheses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The term itself was first coined by Elkins & Simeon in their study of Canada (Citation1980).

2 Through mention in electoral programmes, in press statements or in party constitutions etc. See appendix for a full list of secessionist parties included.

3 Rattachist parties (such as Sinn Fein in Northern Ireland), and Irredentist secessionist (such as EH Bildu) have also be included in this category.

4 These include, for instance, elections to the Basque Juntas Generals/Batzar Nagusiak.

5 NSWP are known to perform much better in regional elections than statewide contexts, and it stands to reason that regional media may be more influential in these contests as well.

6 This deserves some explanation, and an assurance the author is aware of the existence of the Western Mail. I have not included this paper given its limited circulation in north Wales and de facto status as a regional, south Wales paper.

References

- Agnew, John. 1995. “The Rhetoric of Regionalism: The Northern League in Italian Politics, 1983–94.” Transactions of the Institute of British geographers, pp. 156–172.

- Antonsich, M. 2016. “The ‘Everyday’ of Banal Nationalism–Ordinary People’s Views on Italy and Italian.” Political Geography 54: 32–42. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.07.006

- Baekgaard, M., C. Jensen, P. B. Mortensen, and S. Serritzlew. 2014. “Local News Media and Voter Turnout.” Local Government Studies 40 (4): 518–532. doi:10.1080/03003930.2013.834253

- Billing, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: SAGE Publications.

- Brancati, D. 2008. “The Origins and Strengths of Regional Parties.” British Journal of Political Science, 135–159. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000070

- Dalle Mulle, E. 2017. The Nationalism of the Rich: Discourses and Strategies of Separatist Parties in Catalonia, Flanders, Northern Italy and Scotland. New York: Routledge.

- Dalle Mulle, E., and I. Serrano. 2019. “Between a Principled and a Consequentialist Logic: Theory and Practice of Secession in Catalonia and Scotland.” Nations and Nationalism 25 (2): 630–651. doi:10.1111/nana.12412

- De Winter, Lieven, and Huri Trusan. 1998. Regionalist Parties in Western Europe. London: Routledge.

- Dowling, A. 2013. Catalonia Since the Spanish Civil War: Reconstructing the Nation. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

- Elkins, D., and R. Simeon, eds. 1980. Small Worlds: Provinces and Parties in Canadian Political Life. BY: Methuen.

- Fitjar, R. D. 2010. “Explaining Variation in sub-State Regional Identities in Western Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (4): 522–544. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01907.x

- Fraser, D. 2008. Nation Speaking Unto Nation: Does the Media Create Cultural Distance Between England and Scotland?. International Public Policy Review.

- Friend, Julius W. 2012. Stateless Nations: Western European Regional Nationalisms and the Old Nations. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gehring, K., and S. A. Schneider. 2020. “Regional Resources and Democratic Secessionism.” Journal of Public Economics 181: 104073. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2019.104073

- Hamann, K. 1999. “Federalist Institutions, Voting Behavior, And Party Systems in Spain.” Publius: The Journal Of Federalism 29: 111–138. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a030004

- Hepburn, Eve. 2010. “Small Worlds in Canada and Europe: A Comparison of Regional Party Systems in Quebec, Bavaria and Scotland.” Regional & Federal Studies 20 (4-5): 527–544. doi:10.1080/13597566.2010.523637

- Jones, M. 2017. “Wales and the Brexit Vote.” French Journal of British Studies 22: 1–10. doi:10.4000/rfcb.1387

- Law, A. 2001. “Near and Far: Banal National Identity and the Press in Scotland.” Media, Culture & Society 23 (3): 299–317. doi:10.1177/016344301023003002

- Lippmann, W. 2008. Public Opinion. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co.

- Lynch, P. 1995. “From red to Green: The Political Strategy of Plaid Cymru in the 1980s and 1990s.” Regional & Federal Studies 5 (2): 197–210. doi:10.1080/13597569508420930

- Massetti, E. 2009. Explaining regionalist party positioning in a multi-dimensional ideological space: A framework for analysis. Regional and federal studies 19 (4-5): 501–531.

- Massetti, E., and A. H. Schakel. 2013. “‘Ideology Matters: Why Decentralisation has a Differentiated Effect on Regionalist Parties’ Fortunes in Western Democracies’.” European Journal of Political Research 21 (6): 797–821. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12015

- Massetti, Emanuele, and Arjan H Schakel. 2015. “From Class to Region: How Regionalist Parties Link (and Subsume) Left-Right Into Centre-Periphery Politics.” Party Politics 21 (6): 866–886. doi:10.1177/1354068815597577

- Morgenstern, Scott, Stephen M. Swindle, and Andrea Castagnola. 2009. “Party Nationalization and Institutions.” The Journal of Politics 71 (4): 1322–1341. doi:10.1017/S0022381609990132

- Paasi, A. 2013. “Regional Planning and the Mobilization of ‘Regional Identity’: From Bounded Spaces to Relational Complexity.” Regional Studies 47 (8): 1206–1219. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.661410

- Petersoo, P. 2007. “What Does ‘we’ Mean?: National Deixis in the Media.” Journal of Language and Politics 6 (3): 419–436. doi:10.1075/jlp.6.3.08pet

- Piolatto, A., and F. Schuett. 2015. “Media Competition and Electoral Politics.” Journal of Public Economics 130: 80–93. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2015.04.003

- Prat, Andrea, and David Strömberg, Commercial Television and Voter Information. 2005. “CEPR Discussion Paper No. 4989,” Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract = 772002.

- Rosie, M., and P. Petersoo. 2009. “Drifting Apart? Media in Scotland and England After Devolution.” In National Identity, Nationalism and Constitutional Change, edited by F. Bechhofer, and D. McCrone, 122–143. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rosie, M., P. Petersoo, J. MacInnes, S. Condor, and J. Kennedy. 2006. “Mediating Which Nation? Citizenship and National Identities in the British Press.” Social Semiotics 16 (2): 327–344. doi:10.1080/10350330600664896

- Schakel, A. H. 2013. “Nationalisation of Multilevel Party Systems: A Conceptual and Empirical Analysis.” European Journal of Political Research 52 (2): 212–236. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02067.x

- Scully, R., and J. Larner. 2017. “A Successful Defence: The 2016 National Assembly for Wales Election.” Parliamentary Affairs 70 (3): 507–529. doi:10.1093/pa/gsw033

- Shair-Rosenfield, S., A. H. Schakel, S. Niedzwiecki, G. Marks, L. Hooghe, and S. Chapman-Osterkatz. 2021. “Language Difference and Regional Authority.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (1): 73–97. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1831476

- Slavtcheva-Petkova, V. 2014. “Rethinking Banal Nationalism: Banal Americanism, Europeanism and the Missing Link Between Media Representations and Identities.” International Journal of Communication 8: 19. 1932–8036/20140005.

- Szulc, L. 2017. “Banal Nationalism in the Internet age: Rethinking the Relationship Between Nations, Nationalisms and the Media.” In Everyday Nationhood, edited by Evans J. Fox and Cynthia Miller-Idriss, 53–74. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tatham, M., and H. A. Mbaye. 2018. “Regionalisation and the Transformation of Policies, Politics, and Polities in Europe.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (3): 656–671. doi:10.1111/jcms.12713

- Terribas i Sala, Monica. 1994. “Television, National Identity and the Public Sphere-a Comparative Study of Scottish and Catalan Discussion Programmes.” (1994).

- Thomas, J. 2006. “The Regional and Local Media in Wales.” In Local Journalism and Local Media: Making the Local News, edited by B. Franklin, 71–81. London: Routledge.

- Thomas, J., S. Cushion, and J. Jewell. 2004. “Stirring up Apathy? Political Disengagement and the Media in the 2003 Welsh Assembly Elections.” Journal of Public Affairs 4 (4): 355–363. doi:10.1002/pa.198

- Tobeña, A. 2017. “Secessionist Urges in Catalonia: Media Indoctrination and Social Pressure Effects.” Psychology (Savannah, GA) 8 (01): 77. doi:10.4236/psych.2017.81006

- Van Houten, Pieter. 2007. “Regionalist Challenges to European States: A Quantitative Assessment.” Ethnopolitics 6 (4): 545–568. doi:10.1080/17449050701607648

- Weaver, D. H. 1996. “What Voters Learn from Media.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 546 (1): 34–47. doi:10.1177/0002716296546001004

- Williams, K. 2000. “Claiming the National: The Welsh Media and Devolution.” Scottish Affairs 32 (1): 36–58. doi:10.3366/scot.2000.0030

Appendices

Appendix A: Secessionist Parties Classification (including all regions included in dataset with dates of inclusion)

Appendix B: Notes on inclusion and coding

To be included a region must be an integral part of a state, not a dependent territory or similar arrangement, and must have representation in the statewide legislature so that it may theoretically be part of the same party system. For inclusion, a region must be one of the following. It could be a first level administrative division with an elected body. Alternatively, it may be a unit larger than a local elected unit with institutional recognition (eg. Scotland and Wales pre-devolution, Flanders and Wallonia before the establishment of separate elections for regional parliaments).

Some exceptions have been made to this criteria under specific rules. A second-level subdivision may be included if it has an elected governing body covering its entire territory, and an ethno-regionalist movement of its own. This has allowed for the inclusion the French departments of Pyrénées-Orientales and Pyrénées-Atlantiques, which have NSWP, but are technically 2nd tier divisions, and Araba/Álava (within the Basque Autonomous Community), and the Val d’Aran (within Catalonia). I have not, however, allowed the inclusion of areas within larger subdivisions which have no governing body for the whole area. León, is therefore not included, as it is composed of several provinces, but the autonomous community of Castile and León is.

In cases where NSWP compete in multiple regions, I have included the regions as small worlds individually. This was done for the sake of consistency – in some of the regions in question (e.g. Navarre and the Valencian Community in Spain, and South Tyrol and the Aosta Valley in Italy), both NSWP specific to that region and NSWP that compete in multiple regions contest elections. This means that many of the Italian regions are included separately even though their NSWP is a Lega Nord branch.

Regional Media Variable

The variable is based on the consumption of media by regional populations. 0 Indicates that no regional media organisations of that type exist in the territory. For instance, a 0 in the newspaper category indicates that there are no region-wide daily newspapers in the region. A score of one indicates a situation where regional media exists but coexists in a junior position to the statewide media. In this situation, circulation figures for regional newspapers would be less than those for statewide papers. In category 2, regional newspaper circulation would exceed those of statewide titles in the region and indicate that the majority of the population prefers to consume regional media. Similarly, regional television channels would receive higher viewerships and more inhabitants would listen to regional radio stations than statewide ones.

Several sources were used to code the variable. If they were available, viewing, listening and circulation figures released by national regulatory agencies and similar bodies were used, with regional titles compared to statewide ones. This data was not always possible given that releases of such data is sporadic (if at all), and often not released at the regional level. I therefore relied often on the academic literature, seeking out publications which discussed the media environments of specific regions and coding the territory according to the author’s assessments.

The schema is by nature imprecise although I would argue precise enough to make solid conclusions about the relationship between regional media and NSWP support. It is confined to three broad bands, rather than offering precise detail. While ideally I would have collected viewing and listening figures for regional television and radio stations, and circulation figures for regional press, this data is extremely hard to come by and it would be impossible to construct a continent-wide comparative dataset of them. The schema constructed is therefore broad enough to be most likely very reliable, although it is admittedly not as reliable as a continuous variable. Another weakness of this coding scheme is that it’s very difficult to measure online consumption for the last two decades included. Future researchers should seek to develop this measure and expand its specificity.