ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has created yet another dimension of performance on which governments can be judged during elections. This article focuses on how the pandemic and its management factored into vote choices in provincial elections in Canada. Did pandemic considerations overwhelm other factors, or was it a tangential consideration? We address this question with data from a series of two-wave election surveys that were conducted by the Consortium on Electoral Democracy (C-Dem) using online samples of citizens.

Introduction

Regardless of which basic dimensions voters use to evaluate governments, election outcomes are always the same – either electors vote the ‘rascals’ out because of displeasure with their performance or they keep them around to continue with the status quo (Downs Citation1957; Key Citation1966). A long literature documents the types of factors that can be used in these evaluations, from economic evaluations (e.g. Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier Citation2019), overall government approval (e.g. Brody and Sigelman Citation1983), or evaluations of promises kept (e.g. Matthieß Citation2020). Yet, since the pandemic hit countries around the globe in 2020, there is yet another dimension of performance on which governments can be judged. How has the government handled the pandemic? Have the policies been helpful at preventing large outbreaks? Were the programmes put in place useful for those who were faced with unemployment and health issues? And how has the economy suffered? In some countries, when the pandemic began there was an upswing in support for governments who scrambled to support citizens and maintain control over borders as effectively as possible (for the Canadian situation, see Harell et al. Citation2020; Pickup et al. Citation2020; Merkley et al. Citation2020). This type of ‘rally round the flag’ effect has long been a documented phenomenon, with studies showing its presence in the midst of foreign policy and natural disasters (for an early statement, see Mueller Citation1970; also see Lambert, Schott, and Scherer Citation2011; for COVID-specific results, see Yam et al. Citation2020; Bækgaard et al. Citation2020; for mixed results related to government trust, see Kritzinger et al. Citation2021). Over time, however, as the COVID-19 pandemic wore on, fractures in support appeared over specific policy choices. Were vaccines procured in time? Was there a shortage of supplies? Were restrictions too tight or not tight enough? Were waves of infection preventable or inevitable? In Canada, there was some vocal pushback against the COVID policies of the federal government that culminated in ‘Freedom Convoy’ protests in Ottawa and other parts of the country in January 2022.

This article focuses on how the pandemic and its management factored into vote choices in Canada. The Canadian context is particularly interesting because five provincial elections were held in the year and a half following the declaration of the pandemic in March, 2020. Did pandemic considerations overwhelm other factors, or was it a tangential consideration? We focus on answering this question with data drawing upon a series of two-wave election surveys that were conducted by the Consortium on Electoral Democracy (C-Dem) using online samples of citizens.

Studying voter dynamics with respect to the COVID-19 pandemic at the subnational level is particularly appropriate in the Canadian case because the majority of restrictions and health care choices, such as COVID testing, surgery delays and school cancellations, are the responsibility of provincial governments. However, despite this clear jurisdictional point, in four of the five elections we study here the incumbent was re-elected. This suggests, overall, that either there was not a lot (or enough) discontent among voters with how the pandemic was handled, and/or that other issues pushed voters to stick with the status quo when they went to the polls. By comparing experiences across these elections, we can draw lessons about the impact of pandemic satisfaction on voter behaviour. The focus of this article is to test the extent to which voters in five provincial elections in Canada were affected by pandemic considerations.

Theories of voting in a pandemic

To best understand how governments were or were not punished for their management of the pandemic at the voting booth, it first important to think about how voters make up their minds during elections. Early studies of voting behaviour privileged social group explanations (Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee Citation1954), with the understanding that group identity would lead voters to prefer a specific party. Blais (Citation2005) suggests that social demographics remain important vote choice considerations. Subsequent studies varied between portraying voters in instrumentally rational terms (Downs Citation1957) and a more complex socio-psychological perspective that incorporated partisan identification (Campbell et al. Citation1960). Still others prioritized retrospective evaluations (Key Citation1966; Fiorina Citation1981) or valence issues (Clarke et al. Citation2004), or advocated for a more comprehensive approach that considers the temporal nature of the many, varied factors that shape vote preferences (Miller and Shanks Citation1996; Gidengil et al. Citation2012). These models shape much of our understanding of vote choices today: partisanship, retrospective evaluations of the economy, and valence politics have been important considerations in recent vote analyses around the world (see, for example, Clarke et al. Citation2009b; Kalaycıoğlu Citation2021), in Canada (Anderson Citation2008; Daoust and Dassonneville Citation2018; Gidengil et al. Citation2012; Clarke et al. Citation2019), and at the subnational level (Cross et al. Citation2015; González-Sirois and Bélanger Citation2019; Roy and McGrane Citation2015).

Indeed, studies of provincial elections in Canada have relied on many models commonly used at the national level (for example, see the comparison in Roy and McGrane Citation2015). While provincial economic conditions impact incumbent support as expected, there is an interesting deviation in that there is also an impact of federal economic conditions when there is partisan overlap between the federal government and the provincial incumbent (Gélineau and Bélanger Citation2005; González-Sirois and Bélanger Citation2019). Partisanship is also a recognized factor, which is interesting because of the considerable deviation between provincial and national party systems across Canada (see, for example, Johnston Citation2017). Clarke and Stewart (Citation1987) and Stewart and Clarke (Citation1998) documented how belonging to ‘two political worlds’ (Blake, Elkins, and Johnston Citation1985) can weaken partisan loyalty, but partisanship nonetheless is an important factor in provincial models. Even though many parties share the same names at the provincial and federal levels, the links between them are not usually formal (except the NDP) and often involve campaign and administrative logistics (Esselment Citation2011; Pruysers Citation2016).

When it comes to analysing what might have mattered in the pandemic provincial elections, then, each of the existing vote choice models has something to offer. For investigating the impact of how a government managed the pandemic, retrospective evaluations seem particularly relevant, as evaluating government performance is necessarily a retrospective activity similar to economic voting. The findings of Pétry, Duval, and Birch (Citation2020) in a case study of Quebec suggest that provincial governments can avoid some punishment when they fulfil fewer promises than federal governments due to complicating jurisdictional factors, but when it comes to the pandemic it was an unforeseen event. Therefore, there is no real benchmark for evaluation other than perceptions.

However, vote choices are rarely based on simple ‘good’ or ‘bad’ evaluations, even during pandemic elections. First, we must recognize that not everyone may see the pandemic as the most important issue in the election, so their evaluation of its handling may be of little salience. Issue salience is a vitally important consideration when determining what people respond to (Bélanger and Meguid Citation2008; for a review, see Dennison Citation2019), and elections during a pandemic are no different. Governments do, after all, make policy decisions that can impact all areas of one’s life. If someone did not find their lives particularly disrupted by the pandemic or believe that the pandemic was outside the government’s control, they are unlikely to hold the incumbent responsible at the ballot box.

A second and equally important consideration is the role of motivated reasoning. It is rare for a voter to be completely objective when evaluating a government’s record. Partisanship is a very powerful force that provides both a shortcut for vote decisions (Bonneau and Cann Citation2015) as well as a perceptual screen that influences evaluations of candidates (Rahn Citation1993) and objective conditions, like the economy (Jones Citation2020). Research demonstrates that partisan ties have this kind of biasing effect in Canada, at the local (McGregor, Anderson, and Pruysers Citation2021) and national (Merkley Citation2021) levels. When thinking about the pandemic, those who identify with the incumbent party may well think the government did the best they could in an unprecedented situation, while partisans of other parties may be more likely to see the faults and place blame on the government. Partisans receive signals from ‘their’ parties about how to understand issues and are more inclined to evaluate their own party’s performance positively. However, such partisan motivated reasoning can be conditioned by intra-party heterogeneity demonstrated through cross-partisan support (Bolsen, Druckman, and Cook Citation2014). Because pandemic management was not a particularly partisan issue in Canada (Merkley et al. Citation2020; at least prior to the arrival of vaccines), it is uncertain whether partisan bias will be as distinct.

Cross-partisan support is more common in crisis situations that are experienced by an entire population. Many governments saw a ‘COVID bump’ in popularity (Merkley et al. Citation2020; Bol et al. Citation2021), and it is not uncommon to see a rallying of support behind the government in times of crisis, across party lines. This type of ‘rally round the flag’ effect has long been a documented phenomenon, with studies showing its presence in the midst of foreign policy and natural disasters (for an early statement, see Mueller Citation1970; also see Lambert, Schott, and Scherer Citation2011). In the UK, a good comparison case for Canada with its Westminster system of government, Lanoue and Headrick (Citation1998) found that while the popularity of the Prime Minister was affected by crises, the popularity of the governing party was not. However, in a recent piece Bol et al. (Citation2021) found both diffuse and specific government support in European countries related to actions taken against the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, while a specific government leader may be affected by pandemic management attitudes, this may also carry over to their party as well.

There are multiple reasons to expect a rallying effect in times of crisis, including the lack of public criticism (Brody Citation1991; Baker and O’Neal Citation2001) and emotional motivations, such as the need for security to combat personal anxiety or anger (see Lambert, Schott, and Scherer Citation2011 for a discussion). Such ‘rally round the flag’ effects are also heterogeneous: the nature of the crisis matters (economic vs. international), the partisan leanings of the citizen matter, and whether the governing party ‘owns’ the issue can matter (Merolla and Zechmeister Citation2013). Rally effects can create a related ‘halo’ effect across unrelated domains (Bowen Citation1989). Nonetheless, the point of the rally effect is that those who might not normally support the government could find themselves doing so in a crisis. This may also be because leaders during a crisis benefit from their authority to deal with the issue. For example, Merolla, Ramos, and Zechmeister (Citation2007, 39) note,

during times of crisis, individuals look for a strong, confident leader, and they project additional power, morality, and competence onto that individual. They further become more willing to overlook policy mistakes … These findings help explain both the allure and the “Teflon” nature of leaders who come to power in times of crisis.

Based upon the above reasoning, we therefore have the following expectations for the five provincial elections we are studying:

H1: Evaluations of pandemic management will be moderated by partisanship, such that partisans of the incumbent party will approve of the government more than other partisans.

H2: Evaluations of pandemic management will contribute to evaluations of the incumbent premier, even among partisans of other parties and non-partisans.

H3: Positive evaluations of pandemic management will translate into electoral support for the incumbent party, especially among partisans of non-incumbent parties and non-partisans.

The cases

From August 2020 to August 2021, five provincial election campaigns took place in Canada. Although the pandemic was a relevant factor in each, the specific COVID context varied widely, from less than 1 to almost 30 active COVID-19 cases per 100 000 people averaged over the days between the election call and voting day.Footnote1 At least initially, some provinces were able to manage the pandemic by restricting entrance and enforcing stringent quarantines (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia) while others experienced large spikes (British Columbia).Footnote2 The pandemic experiences of voters, including their own personal exposure to risk and restrictions imposed by their province,Footnote3 varied depending on where one was in Canada.

The first COVID election held in Canada was in New Brunswick. Progressive Conservative Premier Blaine Higgs called an early election in August 2020, a full two years before the next election was mandated to occur. This was not unexpected as his government only held a minority of the seats in the legislature, but there was the potential for consequences: calling early elections can create resentment toward the incumbent that affects vote choice (Blais et al. Citation2004; Daoust and Péloquin-Skulski Citation2021) but it can also increase trust (Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2022). New Brunswick, along with the other Atlantic provinces (PEI, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador), had benefited from border controls and the so-called ‘Atlantic Bubble’ to enjoy relatively lower levels of infection than other parts of the country.Footnote4 At the time the election was called, the prevalence of the disease in New Brunswick was low in terms of cases throughout the course of the election period, and even declined. However, according to the stringency index calculated by Breton et al. (Citation2021),Footnote5 the government restrictions put in place to mitigate the risk actually increased somewhat over the same period. This may have increased the salience of the pandemic in the minds of voters, despite the immediate health risk being fairly stable.

British Columbia’s early election was called by John Horgan’s New Democratic Party (NDP) minority government shortly after the New Brunswick election, and it was followed closely by a regularly scheduled election campaign in Saskatchewan. In BC the election was early compared to its expected date in May, 2021, but not fully unexpected. The Saskatchewan election, however, came when expected by the fixed election date law in the province because the Saskatchewan Party majority government had no reason to call an election early. In both cases, the prevalence of COVID-19 in the province was much higher than in New Brunswick, with Saskatchewan seeing an increase in cases between the time the election was called and election day. However, the restrictions on citizens remained stable throughout the campaigns in both provinces.

Newfoundland and Labrador had a very different experience. The province had very little experience with the virus compared to most other provinces, largely due to its ability (like New Brunswick) to limit travel from outsiders. The Liberal premier called an early election on January 15, 2021, in this context. The election was ‘early’ in two ways – because it was two years prior to the fixed election date based upon the previous election, and because it was six months earlier than required due to the change in premier. Thus, it must have seemed like an opportune time for the governing party. However, the province was rocked by a sharp spike in infections during the campaign, leading the Chief Electoral Officer to cancel in person voting on election day amid a rise in pandemic restrictions and concern about being able to staff voting locations. While the election was supposed to have occurred on February 13, a series of extensions and changes led to mail ballots being received for processing up until March 25, 2021.

In contrast, Nova Scotia’s early election was called in later summer 2021 in a period of relative pandemic calm. Although the election was technically early, the majority government had been in place for four years, so it was not unexpected. Cases were low, and stayed low, and restrictions remained the same throughout the campaign. Interestingly, the restrictions were less stringent than for any of the other elections studied here. This was the only election among our cases in which the incumbent government lost power.

Data and methods

The Consortium on Electoral Democracy (c-dem.ca) conducted two-wave election studies for each of the pandemic elections we study here (Everitt, Stephenson, and Harell Citation2022; Berdahl, Stephenson, and Harell Citation2022; Pickup et al. Citation2022; Stephenson and Harell Citation2022; Roy, Stephenson, and Harell Citation2022).Footnote6 C-Dem also conducted the 2019 and 2021 Canadian Election Studies, and the provincial surveys were modelled on these national studies. The data contains many questions of direct relevance for evaluating vote choice, partisanship, and policy salience, as well as attitudes toward pandemic management and the provincial government. Surveys were fielded two weeks prior to election day in each province and then all respondents were re-contacted immediately following the election for a follow-up survey. Each survey was approximately 20 minutes long and was self-administered online via the Qualtrics platform. Respondents were recruited from online panel providers. Sample sizes ranged from n = 854 in NL to n = 1505 in BC. Each study was quota-sampled based on the distribution of key demographic variables; the quotas were roughly met, and weights are used in the analyses below to improve representativeness.Footnote7 Technical details for each survey are available online (Everitt, Stephenson, and Harell Citation2022; Pickup et al. Citation2022; Berdahl, Stephenson, and Harell Citation2022; Stephenson and Harell Citation2022; Roy, Stephenson, and Harell Citation2022).

How can we evaluate the impact of the pandemic on vote choice in provincial elections in Canada? In this paper we use a modified version of a valence model (Sanders et al. Citation2011) to address the main factors discussed above. Valence models prioritize evaluations of leaders, partisanship, and party competence on important issues. In regular non-pandemic elections, such models have been shown to perform well for explaining vote choice in Canada (Clarke, Kornberg, and Scotto Citation2009a) and in Britain (Sanders et al. Citation2011). Our primary dependent variable is incumbent vote, coded as a dummy variable from a survey question asked after the election. Evaluations of party leaders are drawn from feeling thermometers, gathered during the campaign period, that range from 0 to 100. Partisanship is coded from a campaign period survey question that asks whether the respondent usually thinks of themselves as a supporter of a particular party. We created a variable that was coded 1 for incumbent party supporters; 2 for partisans of a different party; and 3 for non-partisans. To measure party competence on important issues, we coded for campaign period responses that indicated the incumbent party was the best able to handle what the respondent perceived as the most important issue in the election. We also created a variable to measure attitudes about the economy, coded 1 if the respondent indicated the economy had got worse, as this could be considered a measure of competence as well. To these variables we add a measure of satisfaction with the province’s handling of the pandemic as a retrospective evaluation, taken from a survey question fielded during the campaign that read, ‘How satisfied are you with the following governments’ handling of the COVID-19 pandemic? [Provincial government named].’ The responses, ranging from not at all satisfied to very satisfied, were rescaled to run from 0 to 1. When used as an independent variable, we created a dichotomous variable that distinguished between satisfied (very or somewhat) and not satisfied (not very and not at all).Footnote8

Analyses

The objective of this paper is to investigate whether voters electorally punished or rewarded governments for their management of the pandemic. To set the stage, it is useful to gain a sense of how salient the pandemic was for voters. Respondents in the surveys were asked to indicate their most important issue. shows the percentage of responses that referenced the pandemic directly in their responses, either as the main issue itself (for example, ‘COVID’) or as necessitating further government action (economic recovery due to the pandemic) or as reference to pandemic restrictions and policies in particular (‘masks’ or vaccine mandates).Footnote9

Table 1. Salience of pandemic in most important issue question.

Focusing on specifically mentioning the pandemic is a relatively strict test of issue salience, as the pandemic is also linked to more general policy areas, specifically health care, the economy and government spending. As those are more typical issue areas in elections, however, it would be unclear whether it was the pandemic that was driving the salience or whether the general issue area would have retained its significance regardless. For comparison, we also report responses that referenced health or the economy in .

Two things stand out: first, the pandemic was most salient in British Columbia. Seeing as New Brunswick fared relatively well at the start of the pandemic, it is not surprising that the issue was less salient there. The low value for Saskatchewan is more surprising. However, the second point is that the issue was not overwhelmingly important anywhere. In all cases, the economy was a more salient issue and in 4 out of 5 provinces health was also more salient. This suggests that pandemic management did not predominate vote choice, though we cannot dismiss the possibility that the economy – or healthcare – as a general issue was more salient as a result of the pandemic.

Before evaluating the influence of pandemic management on incumbent vote choice, it is important to understand attitudes and partisan biases in evaluations of pandemic management and evaluations of the incumbent premier. These issues correspond to hypotheses 1 and 2.

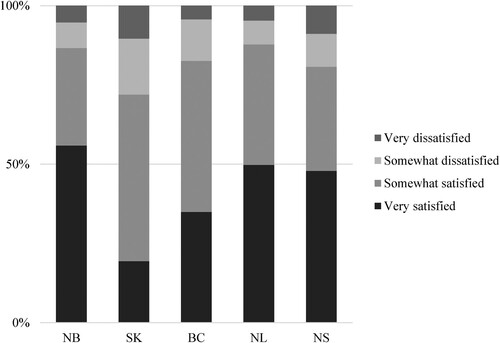

We first consider satisfaction with the incumbent government’s management of the pandemic. The distribution of responses on a scale from very dissatisfied to very satisfied is displayed in . It is overwhelmingly clear that the incumbent governments were generally seen as having done a satisfactory job of managing the pandemic. Combining very and somewhat satisfied together, the percent never falls below 72 (Saskatchewan), and reaches a high of almost 88 in Newfoundland and Labrador. Indeed, Saskatchewanians seem least satisfied with their pandemic government (lowest ‘very satisfied’ value) but still more were satisfied than not.

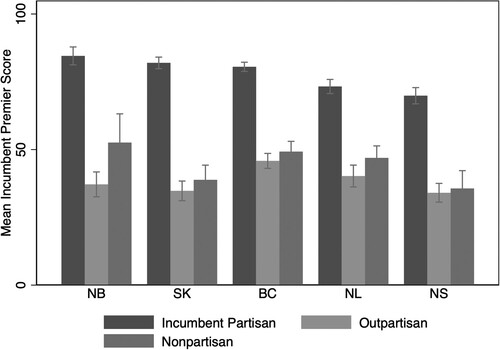

H1 suggests that views of pandemic management may be subject to the same partisan biases as documented regarding economic conditions (Bartels Citation2002; Brady, Ferejohn, and Parker Citation2022). provides insight into this hypothesis, showing the mean level of satisfaction for partisans of the incumbent party compared to others. The data suggest that strong satisfaction remains evident even when we compare across partisan groups and supporters of other parties. While there is significantly less satisfaction among those who are not partisans of the incumbent government, there is still a generally high level of satisfaction, with out-partisan mean satisfaction at or above 50%. Again, Saskatchewan stands out as an outlier with less overall satisfaction. Another way to evaluate the impact of partisan bias on satisfaction with pandemic management is to run a regression with partisanship as an independent variable (incumbent, out-partisan and non-partisan), controlling for age (continuous variable), education (university or higher), and gender (woman), and adding language (French) specifically in New Brunswick due to its relevance in politics there. Full models and a plot of predicted pandemic satisfaction by partisanship (other variables held at original values) is available in the Appendix, Table A1 and Figure A1. In that analysis, it becomes clear that there is an incumbent partisan bias. Those who do not support the incumbent party (out-partisans, and especially non-partisans) have significantly lower evaluations.

Figure 2. Mean satisfaction with pandemic management on a 0–1 scale, by province, incumbent partisans versus others.

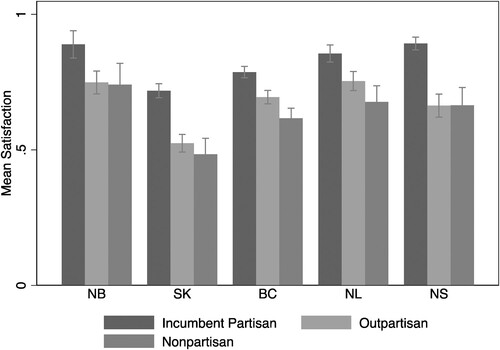

What about the incumbent premiers? Did their evaluations benefit from positive pandemic management (H2)? While incumbent party partisans are likely already very favourable toward their own party’s leader, we are particularly interested in whether out-partisans and non-partisans were particularly likely to have positive evaluations of the pandemic management spill over to evaluations of the incumbent premier. reports the mean score for the incumbent premier on a 0–100 thermometer. Unsurprisingly, the evaluation of provincial premiers was a highly partisan affair. Among partisans of the incumbent party, the ratings are significantly higher than for both out-partisans and non-partisans.

Looking at ratings among incumbent partisans, we see that the premier of Nova Scotia was the least popular. This may be partly because the party leader that went into the election (Iain Rankin) was not the same person who won the election in 2017 and led the Liberal Party to form the government (Stephen McNeil). McNeil resigned in 2020 but remained in office until the Liberals chose a new leader in February 2021. That a relatively new premier might not enjoy as much support as the person who led the population through the early days of the pandemic is not surprising. A similar situation occurred in Newfoundland and Labrador, with that premier (Andrew Furey) having only been the Liberal leader since August 2020 before calling the election in January 2021.Footnote10 Nonetheless, even when there was no change in premier, we see that supporters of other parties and non-partisans rated the incumbent premier significantly worse, though we should note that in New Brunswick, non-partisans were significantly warmer toward the premier than out-partisans. It is hard to assess whether out-partisan and non-partisan ratings were higher than they would be under normal circumstances, as the baseline for comparison is unknowable. Yet, we clearly see from that there was not a full rally under the leadership of the existing premier.

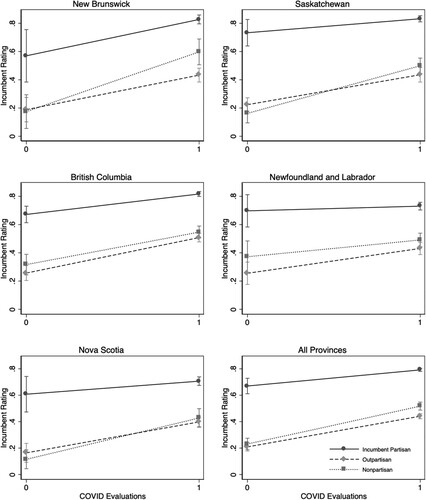

A more rigorous way to analyse this is by modelling incumbent leader ratings with an interaction term between partisanship and pandemic evaluations in an OLS regression model with control variables. presents the predicted ratings for partisans with different pandemic evaluations (other variables held at their original values). All other variables are excluded from the figure (full models available in the Appendix Table A2). It is clear that positive evaluations of the pandemic were related to higher leader ratings for the incumbent, regardless of partisanship, though out-partisans and non-partisans were less favourable overall. This reflects what the analysis of means reported above shows. We also see, however, evidence of a rally effect in some of the cases under consideration here. In Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia non-partisans are significantly more supportive of the incumbent premier when they approved of the pandemic handling (see Appendix Table A2). In Saskatchewan, BC, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia, the interaction term is significant for out-partisans, meaning that when pandemic evaluations were higher, their leader evaluations were higher. Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia are the clearest examples of a rallying effect around the leader, yet Nova Scotia is the only case in our study where the incumbent actually lost the election. In a pooled model of all provinces (also shown in ), both non-partisans and out-partisans express significantly higher support for the incumbent premier when their pandemic approval is higher.

Figure 4. Interaction effects for partisanship and pandemic evaluations on support for incumbent premiers.

Did incumbents have a pandemic edge?

Now that we have considered the component factors, we turn to evaluating the impact of the pandemic on vote choice. Recall that in no province did the pandemic appear to be the most important issue of the election.

To investigate H3, concerning the impact of the pandemic on vote choice, we run logistic regression models in each province. We analyse each province independently because we recognize that each of the factors may operate quite differently. The dependent variable is voting for the incumbent or not. We start with a basic model (Model 1) of pandemic evaluation and controls (age, education, gender, language in New Brunswick). Then we add, in consecutive models, the factors that are expected to have relevance in a valence model: partisanship (out-partisan and non-partisan, base = incumbent partisan); two measures of party competence: which party is best able to handle the most important issue (=1 if incumbent party) and economic evaluations (=1 if worse); and an incumbent premier feeling thermometer (recoded 0–1).Footnote11 The full regression results are reported in the Appendix (Tables A3–A7).

Support for H3 would come in the form of a positive and significant coefficient for the evaluation of the COVID-19 pandemic. We see this consistently across the provinces in the basic model (Appendix Tables A3–A7). When we add partisanship variables, it continues to be significant everywhere except for Newfoundland and Labrador. Once we add the measures indicating competence, it only remains significant in BC and Nova Scotia. After adding the evaluation of the incumbent premier, evaluations of pandemic management cease to be positive and significant in any province. It actually becomes negative and significant in New Brunswick, contrary to expectations. One possibility is that the general cross-partisan satisfaction with pandemic management is overwhelmed by partisanship when it comes to more traditional vote factors.

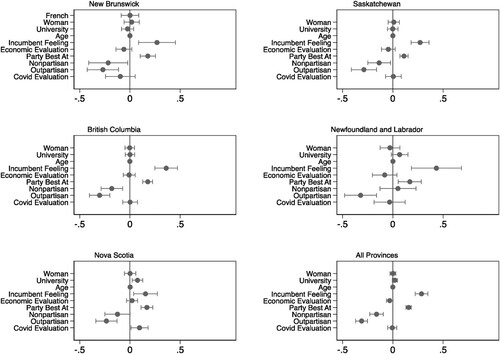

To get a better picture of these effects, we graphed the average marginal effects of each variable in the final model (other variables held at original values). shows the marginal effects and 95% confidence intervals for each province. What stands out is that major components of a valence model of vote choice – partisanship, party issue handling and feelings towards the leader – are important in every case. The exception is economic evaluations, which are likely dwarfed by the impact of the more general issue handling variable. The effect of partisanship is also as expected: out-partisans are more negative than non-partisans. Evaluations of pandemic management are dwarfed – they are only significant once. These results hold in a pooled model of all provinces ().

Figure 5. Average marginal effects on incumbent vote choice, logistic models by province (other variables held at original values).

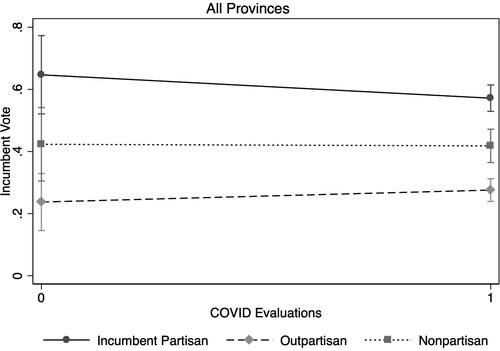

While pandemic evaluations seem to have little to no effect, it is possible that these attitudes only mattered among those who were less inclined to vote for the incumbent. Were non-partisans or out-partisans more likely to vote for the incumbent based on their pandemic evaluations? To explore this, we run a logistic regression model including interaction terms between partisanship and pandemic evaluations for the pooled dataset, with controls as above. The predicted outcomes for partisans with different pandemic evaluations (other variables held at original values) are shown in (regression results are shown in Appendix Table A8). Despite the strong evaluations of pandemic management across partisan groups, we find no significant interaction terms. Out-partisans and non-partisans did not support the incumbent party at the ballot box significantly more than incumbent partisans due to their positive evaluation of pandemic management. Although there is a bivariate relationship between support for the incumbent and positive pandemic management perceptions, this relationship appears to be largely spurious and related to underlying partisan preferences and their ability to shape perceptions of the incumbent’s handling of the pandemic.

Discussion and conclusion

We began this paper with the objective of understanding how a once-in-a-lifetime event might influence people’s vote choices. In four of the five provincial elections held in Canada between 2020 and 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, incumbent governments were returned. At first glance, this suggests a rallying behind the administration that provided security, services, and safety during a crisis. The academic literature supports that explanation – in times of crisis, not only can governments receive an approval boost but even leaders can benefit from perceptions of charismatic leadership in the face of a crisis.

To test whether this was in fact the case, we first looked to see whether there was evidence that the government was evaluated highly on its pandemic efforts, whether there was pandemic bias, and whether the incumbent premier benefited from being at the helm while the pandemic policies were developed. We found mixed evidence – while the government’s activities were evaluated highly, there is no evidence of cross-partisan approval for the premier nor that the pandemic itself was highly salient during the elections (although, as noted above, we cannot disentangle whether the salience of other issues was in fact a consequence of the pandemic, hence indicating indirect salience). We then turned to a well-used model of vote choice in order to balance pandemic evaluations against standard factors that are known to influence voters. We found that although those who evaluated the pandemic management highly were more likely to vote for the incumbent party, this effect was largely driven by partisan evaluations of pandemic management. There is little indication that pandemic management led partisans of other parties, or non-partisans, to be more inclined to vote for the incumbent.

One of the limits of this analysis is that the data were collected around elections, while many of the rallying effects around governments were observed in the first months of the pandemic that were characterized by a lot of uncertainty, as well as cross-party unity. One possibility is that incumbent parties did in fact benefit from the pandemic, but rather than directly affecting vote choice, it shifted people’s identification towards the party in power prior to the election. We cannot explore this possibility here, as that would require panel data that incorporated previous attitudes. What is clear from our analysis, however, is that during election campaigns where parties made arguments about why they should govern, there was much less cross-party unity than at the start of the pandemic. This environment reinforced the partisan-motivated evaluation of both the government’s handling of the crisis and the personalities involved and appears to have limited the impact that the pandemic had on the electoral outcomes.

Appendix

Download MS Word (536.3 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Reported at https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html.

2 For a detailed case study of each of the first four provincial elections, see Garnett et al. (Citation2021).

3 Information about restrictions, including an Average Restrictions Index, can be found in Breton et al. (Citation2021).

4 The ‘Atlantic Bubble’ was announced on June 24, 2020 (to begin July 3, 2020) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. When initially created, citizens of the four Atlantic provinces could travel across those provincial borders without restriction (https://cap-cpma.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CAP-Release-AP-Form-Travel-Bubble-June-24-2020.pdf). The bubble was suspended in November 2020 due to rising infections in some areas. Attempts to reopen the bubble in 2021 were complicated by additional waves of COVID-19.

5 Breton et al.’s (Citation2021) stringency index takes a variety of different public health measures into consideration, including gathering restrictions; mask mandates; whether schools are open and whether masks are required in schools; restrictions in care homes, dining and restaurants, personal care services, cultural attractions, and intra- and inter-provincial travel; curfews; and vaccine mandates (https://centre.irpp.org/2021/07/covid-19-stringency-index-new-codebook/).

6 Data were gathered under ethics approval #115422 from the Non-Medical Research Ethics Board at the University of Western Ontario.

7 The survey weights adjusted for age, gender, and education to match the 2016 Canadian Census estimates for the population 18 and older in the province. In New Brunswick, language was also incorporated.

8 This was done to address the fact that when we interact pandemic satisfaction with partisanship, we end up with few respondents in some of the cells (in particular, incumbent government partisans and low evaluations).

9 Missing data and non-responses were excluded from the calculations. At least one respondent indicated that the most important issue was NOT COVID, and such responses have been coded as not indicating the pandemic is the most important issue.

10 By law, an election had to be called within one year of Furey assuming office.

11 To check for multicollinearity, we confirmed that the variance inflation factors never exceeded the standard threshold of 10.

References

- Anderson, Cameron D. 2008. “Economic Voting, Multilevel Governance and Information in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 41 (2): 329–354. doi:10.1017/S0008423908080414

- Baker, William D., and John R. O’Neal. 2001. “Patriotism or Opinion Leadership?: The Nature and Origins of the ‘Rally ‘Round the Flag’ Effect.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 45 (5): 661–687. doi:10.1177/0022002701045005006

- Bartels, Larry. 2002. “Beyond the Running Tally: Partisan Bias in Political Perceptions.” Political Behavior 24 (2): 117–150. doi:10.1023/A:1021226224601

- Bélanger, Éric, and Bonnie M. Meguid. 2008. “Issue Salience, Issue Ownership, and Issue-Based Vote Choice.” Electoral Studies 27 (3): 477–491. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2008.01.001

- Berdahl, Loleen, Laura B. Stephenson, and Allison Harell. 2022. “2020 Saskatchewan Election Study.” Dataset, doi:10.7910/DVN/A1CAXU.

- Berelson, Bernard R., Paul F. Lazarsfeld, and William N. McPhee. 1954. Voting: A Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bækgaard, Martin, Julian Christensen, Jonas Krogh Madsen, and Kim Sass Mikkelsen. 2020. “Rallying Around the Flag in Times of Covid-19: Societal Lockdown and Trust in Democratic Institutions.” Journal of Behavioral Public Administration 392: 1–12. doi:10.30636/jbpa.32.172

- Blais, André. 2005. “Accounting for the Electoral Success of the Liberal Party in Canada: Presidential Address to the Canadian Political Science Association London, Ontario June 3, 2005.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 38 (4): 821–840. doi:10.1017/S0008423905050304

- Blais, André, Elisabeth Gidengil, Neil Nevitte, and Richard Nadeau. 2004. “Do (Some) Canadian Voters Punish a Prime Minister for Calling a Snap Election?” Political Studies 52: 307–323. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2004.00481.x

- Blake, Donald E., with David J. Elkins and Richard Johnston. 1985. Two Political Worlds: Parties and Voting in British Columbia. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Bol, Damien, Marco Giani, André Blai, and Peter J. Loewen. 2021. “The Effect of COVID-19 Lockdowns on Political Support: Some Good News for Democracy?” European Journal of Political Research 60 (2): 497–505. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12401

- Bolsen, Toby, James N. Druckman, and Fay Lomax Cook. 2014. “The Influence of Partisan Motivated Reasoning on Public Opinion.” Political Behavior 36: 235–262. doi:10.1007/s11109-013-9238-0

- Bonneau, Chris W., and Damon M. Cann. 2015. “Party Identification and Vote Choice in Partisan and Non-partisan Elections.” Political Behavior 37: 43–66. doi:10.1007/s11109-013-9260-2

- Bowen, Gordon L. 1989. “Presidential Action and Public Opinion About U.S. Nicaraguan Policy: Limits to the ‘Rally Round the Flag’ Syndrome.” PS: Political Science and Politics 22 (4): 793–800. doi:10.2307/419470

- Brady, David W., John A. Ferejohn, and Brett Parker. 2022. “Cognitive Political Economy: A Growing Partisan Divide in Economic Perceptions.” American Politics Research 50 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1177/1532673X211032107

- Breton, Charles, Ji Yoon Han, Mohy-Dean Tabbara, and Paisley Sim. 2021. COVID-19 Canadian Provinces Measures Dataset. Center of Excellence on the Canadian Federation. https://centre.irpp.org/data/covid-19-provincial-policies/.

- Brody, Richard A. 1991. Assessing the President. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Brody, Richard, and Lee Sigelman. 1983. “Presidential Popularity and Presidential Elections: An Update and Extension.” Public Opinion Quarterly 47 (3): 325–328. doi:10.1086/268793

- Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. New York: John Wiley.

- Clarke, Harold D., Jane Jenson, Lawrence LeDuc, and Jon H. Pammett. 2019. Absent Mandate: Strategies and Choices in Canadian Elections. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Clarke, Harold D., Allan Kornberg, and Thomas J. Scotto. 2009a. Making Political Choices: Canada and the United States. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Clarke, Harold D., David Sanders, Marianne C. Stewart, and Paul Whiteley. 2004. Political Choice in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Clarke, Harold D., David Sanders, Marianne C. Stewart, and Paul Whiteley. 2009b. Performance Politics and the British Voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Clarke, Harold D., and Marianne C. Stewart. 1987. “Partisan Inconsistency and Partisan Change in Federal States: The Case of Canada.” American Journal of Political Science 31 (2): 383–407.

- Cross, William P., Jonathan Malloy, Tamara A. Small, and Laura B. Stephenson. 2015. Fighting for Votes. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Daoust, Jean-François, and Ruth Dassonneville. 2018. “Beyond Nationalism and Regionalism: The Stability of Economic Voting in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 51 (3): 553–571. doi:10.1017/S000842391800001X

- Daoust, Jean-François, and Gabrielle Péloquin-Skulski. 2021. “What are the Consequences of Snap Elections on Citizens’ Voting Behaviour?” Representation 57 (1): 95–108. doi:10.1080/00344893.2020.1804440

- Dennison, James. 2019. “A Review of Public Issue Salience: Concepts, Determinants and Effects on Voting.” Political Studies Review 17 (4): 436–446. doi:10.1177/1478929918819264

- Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Voting. New York: Harper & Row.

- Esselment, Anna Lennox. 2011. “Birds of a Feather? The Role of Partisanship in the 2003 Ontario Government Transition.” Canadian Public Administration 54 (4): 465–486. doi:10.1111/j.1754-7121.2011.00189.x

- Everitt, Joanna, Laura B. Stephenson, and Allison Harell. 2022. “2020 New Brunswick Election Study.” Dataset, doi:10.7910/DVN/WC5290.

- Fiorina, Morris P. 1981. Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Garnett, Holly Ann, Jean-Nicolas Bordeleau, Allison Harell, and Laura Stephenson. 2021. “Canadian Provincial Elections During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Electoral Integrity Project Report, Case Study 17 (December). https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/multimedia_reports/canadian-provincial-elections-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-en.pdf.

- Gélineau, François, and Éric Bélanger. 2005. “Electoral Accountability in a Federal System: National and Provincial Economic Voting in Canada.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 35 (3): 407–424. doi:10.1093/publius/pji028

- Gidengil, Elisabeth, Neil Nevitte, André Blais, Joanna Everitt, and Patrick Fournier. 2012. Dominance and Decline: Making Sense of Recent Canadian Elections. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- González-Sirois, Gaby, and Éric Bélanger. 2019. “Economic Voting in Provincial Elections: Revisiting Electoral Accountability in the Canadian Provinces.” Regional and Federal Studies 29 (3): 307–327. doi:10.1080/13597566.2018.1493576

- Harell, Allison, Laura B. Stephenson, Daniel Rubenson, and Peter J. Loewen. 2020. “How Canada's Pandemic Response is Shifting Political Views.” Policy Options, April 9. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/april-2020/how-canadas-pandemic-response-is-shifting-political-views/.

- Johnston, Richard. 2017. The Canadian Party System. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Jones, Philip Edward. 2020. “Partisanship, Political Awareness, and Retrospective Evaluations, 1956–2016.” Political Behavior 42: 1295–1317. doi:10.1007/s11109-019-09543-y

- Kalaycıoğlu, Ersin. 2021. “Party Identification and Vote Choice in Turkey.” In Elections and Public Opinion in Turkey: Through the Prism of the 2018 Elections, edited by A. Çarkoğlu, and E. Kalaycıoğlu, 1st ed., 170–192. London: Routledge.

- Key, V. O. 1966. The Responsible Electorate. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Kritzinger, Sylvia, Martial Foucault, Romain Lachat, Julia Partheymüller, Carolina Plescia, and Sylvain Brouard. 2021. “‘Rally Round the Flag’: The COVID-19 Crisis and Trust in the National Government.” West European Politics 44 (5-6): 1205–1231. doi:10.1080/01402382.2021.1925017

- Lambert, Alan J., J. P. Schott, and Laura Scherer. 2011. “Threat, Politics, and Attitudes: Toward a Greater Understanding of Rally-’Round-the-Flag Effects.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 20 (6): 343–348. doi:10.1177/0963721411422060

- Lanoue, David J., and Barbara Headrick. 1998. “Short-Term Political Events and British Government Popularity: Direct and Indirect Effects.” Polity 30 (3): 417–433. doi:10.2307/3235208

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Mary Stegmaier. 2019. “Economic Voting.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Choice, Volume 1, edited by Roger D. Congleton, Bernard Grofman, and Stefan Voigt. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190469733.013.12.

- Matthieß, Theres. 2020. “Retrospective Pledge Voting: A Comparative Study of the Electoral Consequences of Governments Parties’ Pledge Fulfillment.” European Journal of Political Research 59: 774–796. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12377

- McGregor, R. Michael, Cameron Anderson, and Scott Pruysers. 2021. “Partisanship, Motivated Reasoning and the Notwithstanding Clause: The Case of Provincially Imposed Redistricting in the City of Toronto.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 59 (1): 94–117. doi:10.1080/14662043.2020.1800294

- Merkley, Eric. 2021. “Ideological and Partisan Bias in the Canadian Public.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 54: 267–291. doi:10.1017/S0008423921000147

- Merkley, Eric, Aengus Bridgman, Peter John Loewen, Taylor Owen, Derek Ruths, and Oleg Zhilin. 2020. “A Rare Moment of Cross-Partisan Consensus: Elite and Public Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 53 (2): 311–318. doi:10.1017/S0008423920000311

- Merolla, Jennifer L., Jennifer M. Ramos, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister. 2007. “Crisis, Charisma, and Consequences: Evidence from the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election.” The Journal of Politics 69 (1): 30–42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00492.x

- Merolla, Jennifer L., and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister. 2013. “Evaluating Political Leaders in Times of Terror and Economic Threat: The Conditioning Influence of Politician Partisanship.” The Journal of Politics 75 (3): 599–612. doi:10.1017/S002238161300039X

- Miller, Warren E., and J. Merrill Shanks. 1996. The New American Voter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mueller, John E. 1970. “Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson.” American Political Science Review 64: 18–34. doi:10.2307/1955610

- Pétry, François, Dominic Duval, and Lisa Birch. 2020. “Do Regional Governments Fulfill Fewer Election Promises Than National Governments? The Case of Quebec in Comparative Perspective.” Party Politics 26 (4): 415–425. doi:10.1177/1354068818787353.

- Pickup, Mark, Dominik Stecula, and Clifton van der Linden. 2022. “Novel Coronavirus, Old Partisanship: COVID-19 Attitudes and Behaviours in the United States and Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 53 (2): 357–364. doi:10.1017/S0008423920000463

- Pickup, Mark, Laura B. Stephenson, and Allison Harell. 2022. “2020 British Columbia Election Study.” Dataset, doi:10.7910/DVN/NXESNA

- Pruysers, Scott. 2016. “Vertical Party Integration: Informal and Human Linkages Between Elections in a Canadian Province.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 54 (3): 312–330. doi:10.1080/14662043.2016.1180842

- Rahn, Wendy M. 1993. “The Role of Partisan Stereotypes in Information Processing About Political Candidates.” American Journal of Political Science 37 (2): 472–496. doi:10.2307/2111381

- Roy, Jason, and David McGrane. 2015. “Explaining Canadian Provincial Voting Behaviour: Nuance or Parsimony?” Canadian Political Science Review 9 (1): 75–91.

- Roy, Jason, Laura B. Stephenson, and Allison Harell. 2022. “2021 Nova Scotia Election Study.” Dataset, doi:10.7910/DVN/4JL3SB.

- Sanders, David, Harold D. Clarke, Marianne C. Stewart, and Paul Whiteley. 2011. “Downs, Stokes and the Dynamics of Electoral Choice.” British Journal of Political Science 41: 287–314. doi:10.1017/S0007123410000505

- Stephenson, Laura B., and Allison Harell. 2022. “2021 Newfoundland and Labrador Election Study.” Dataset, doi:10.7910/DVN/X5HE8X.

- Stewart, Marianne C., and Harold D. Clarke. 1998. “The Dynamics of Party Identification in Federal Systems: The Canadian Case.” American Journal of Political Science 42 (1): 97–116.

- Turnbull-Dugarte, Stuart J. 2022. “Do Opportunistic Snap Elections Affect Political Trust? Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” European Journal of Political Research, doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12531.

- Yam, Kai Chi, Joshua Conrad Jackson, Christopher M. Barnes, Jenson Lau, Xin Qin, and Hin Yeung Lee. 2020. “The Rise of COVID-19 Cases is Associated with Support for World Leaders.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (41): 25429–25433. doi:10.1073/pnas.2009252117