ABSTRACT

With the National Hydrogen Strategy, the German government defined an initial framework for the integration of hydrogen into the energy system. At the subnational level, most Länder have also adopted individual hydrogen strategies. This article examines the coherence between the different strategies. We find a fragmentation of the different strategic goals and approaches towards the market ramp-up of hydrogen technologies, which results from a deficient multilateral coordination within the federal system. Hydrogen coordination in Germany is constrained by party-political and territorial conflicts, but also by the interaction between intra- and intergovernmental dynamics. Thus, to prevent fragmentation of complex energy transition issues, such as hydrogen, regular coordination is required at both the intra- and intergovernmental levels. Given the exemplary nature of the German case, this analysis offers insights for the study of similar coordination challenges encountered in various federal and multi-level systems.

Introduction

Hydrogen has been discussed as a potential energy carrier since the 1970s and is, once again, on top of the political agenda. To meet climate neutrality requirements, hydrogen technologies are being considered both as energy storage solutions and as decarbonization options for hard-to-abate sectors. While energy transitions in federal systems have recently received growing attention (Balthasar, Schreurs, and Varone Citation2020), hydrogen represents a new and uncharted field. Moreover, previous studies have focused predominantly on the role of formal federal structures, but neglected intergovernmental relations. This article aims to address these research gaps by exploring the role of intergovernmental relations in hydrogen governance, using Germany as a case study.

As a highly industrialized country, having the highest hydrogen demand in Europe, Germany is expected to increasingly rely on hydrogen (IEA Citation2021, 20). Consequently, like other European governments, Germany developed a National Hydrogen Strategy (NHS), outlining goals and measures to promote technological development and build international partnerships to meet anticipated needs (BMWi Citation2020). Hydrogen is also playing an increasingly important role at the subnational level. By August 2022, 14 of the 16 German Länder (states) had published regional hydrogen strategies. This is a potential problem, as the market ramp-up for hydrogen technologies requires an efficient and politically feasible allocation of hydrogen supply and demand, including the necessary infrastructure. Individual Länder strategies with different priorities suggest fragmentation that may hinder the market ramp-up of hydrogen. Hydrogen, as a multi-sector issue (Ohlendorf, Löhr, and Markard Citation2023), is supposed to integrate previously separate energy end-use sectors and, thus, political arenas. As a result, the complexity and necessity for coordination in the implementation of hydrogen technologies are considerably high (Kemmerzell and Knodt Citation2020). Against this background, this article will ask two main questions: (1) How fragmented are the hydrogen strategies at the federal and Länder level? (2) What explains this fragmentation? Through an explorative analysis of Germany, as an aspiring hydrogen economy and as a characteristic case of cooperative federalism, this study explores a new empirical field and contributes to a better understanding of coordinating energy transitions in federal systems.

We assume that the fragmentation of German hydrogen strategies is caused by a lack of coordination both between the federal government and the Länder governments (vertical coordination) and among the Länder themselves (horizontal coordination). First, the article briefly reviews the state of research on hydrogen in German politics, as well as policy coordination in the federal system. Then, we introduce our analytic framework, integrating concepts of coordination from federalism and public administration research, and provide details of our method and data. In the empirical analysis, we firstly assess the fragmentation of the federal and Länder hydrogen strategies, and secondly, discuss whether this fragmentation can be explained by a lack of vertical and horizontal coordination.

Energy Transition Within Federal Boundaries – State of Research

Recent studies attribute an important, though partly uncertain, role to hydrogen in the global energy transition (Hanley, Deane, and Gallachóir Citation2018; Kovač, Paranos, and Marciuš Citation2021). In political science, this new issue is addressed primarily in international political economy, with van de Graaf et al. (Citation2020) labelling hydrogen the ‘new oil’ and others anticipating a reconfiguration of the geopolitics of energy (Noussan et al. Citation2021; Pflugmann and de Blasio Citation2020). Political research on hydrogen, in the national context, focuses mostly on stakeholder attitudes and public acceptance (Emodi et al. Citation2021; Ohlendorf, Löhr, and Markard Citation2023). So far, there is little research on hydrogen policy-making and its coordination in federal or multi-level systems (Knodt et al. Citation2022); and yet studies on energy federalism investigate the effects of federal structures on energy transition processes (Balthasar, Schreurs, and Varone Citation2020; Rossi Citation2016).

This article sheds light on federal coordination in a novel subsystem of the Energiewende and contributes to the analysis of innovations in federal contexts. The focus on Germany, as an early mover in the field of hydrogen and an exemplary case of cooperative federalism, provides insights into the processes of innovation policies and suggests recommendations for further research in energy federalism.

Scholarship on German federalism has emphasized the significant importance of shared rule between the federal government and the Länder, which was labelled as Politikverflechtung or interlocking politics (Scharpf Citation1988). Over time, the degree of shared rule increased as the Länder exchanged legislative autonomy for greater participation, in the form of joint decision-making, in the federal legislation through the Bundesrat (Germany’s second chamber). This led keen observers to (ironically) call Germany a unitary state in disguise (Abromeit Citation1992). Despite the increasing centralization of legislation at the federal level, the Länder remained responsible for the implementation of most federal policies. This functional distribution of power, also known as administrative or cooperative federalism, inevitably creates interdependence between the political levels in policy-making (Oeter Citation2006, 155). The Länder depend on federal legislation, while the federal government relies on the effectiveness of its measures not being intentionally, or unintentionally, undermined in the administrative process. In such a system of mutual dependence ‘no single actor will be able to determine the outcome unilaterally’ (Scharpf Citation1997, 7), or to act autonomously without risking inefficiencies or policy failure (Bolleyer Citation2018, 46). Therefore, systems of joint decision-making always run the risk of generating negative externalities if interdependencies of policy making are not sufficiently considered.

In order to cope with functional interdependencies and to ensure the efficiency of the federal system, both the federal government and the Länder are obliged to coordinate with each other, not formally but in practice (Kropp Citation2010). Consequently, intergovernmental relations are essential in German cooperative federalism and are highly institutionalized when compared to other federal systems (Hueglin and Fenna Citation2015). Eighteen sectoral ministerial conferences deal with the exchange of technical information and the coordination of policy implementation between the Länder. In policy sectors with exclusive Länder competence, the ministerial conferences also serve as coordinated autonomy protection (Hegele and Behnke Citation2017). Intergovernmental relations are constrained by party-political conflicts between the various coalition governments among the Länder, as well as by territorial interests (Auel Citation2014). Finally, coordination is also affected by ministerial portfolio allocation, as has been shown for interdepartmental coordination in the Bundesrat – especially in ‘minor policy sectors’ like energy (Hegele Citation2021, 443).

Energy policy is predominantly centralized at the federal level. For major energy issues, such as renewable energy, transmission grids, or the nuclear phase-out, federal legislation does not require the consent of the Bundesrat. Therefore, Benz and Broschek (Citation2020) characterize the energy transition as mostly top-down governance by the federal government, and not as the result of a coordinated endeavour. However, research on sub-national energy policy emphasizes the influence of the Länder on the advance of the energy transition (Schönberger and Reiche Citation2016; Wurster and Köhler Citation2016). Functional distribution of power enables the Länder to shape implementation to their own interest, which, in the case of renewable energy, has led to diverging outcomes at the subnational level (Saurer and Monast Citation2021, 306). In spatial planning and nature conservation, the Länder enjoy a certain degree of self-rule, resulting in restrictions to wind energy in some Länder (Wegner Citation2022, 64). However, several Länder also promote renewable energy through distributional policies or administrative action (Monstadt and Scheiner Citation2016; Ohlhorst Citation2015). Consequently, there are leaders and laggards among the Länder in the implementation of the energy transition (Schill, Diekmann, and Püttner Citation2019).

Although policy competition is inherent in federal systems and can be advantageous in certain policy domains, it can have adverse effects on energy transition processes. Laggards may delay the transition within their jurisdictions, while leaders may create significant overcapacity in renewable energy production, incentivized by federal subsidies. These substantial interdependencies can create negative externalities, such as additional costs in leading Länder, due to the need for grid expansion, or the balancing of volatile renewables caused by the absence of storage and transmission infrastructure. This results in an overall inefficient fragmentation of the energy transition (Kemmerzell Citation2022; Münch Citation2013). Benz (Citation2019, 310) argues that the lack of ex-ante coordination in the energy transition stems from the previously mentioned increasing centralization and ‘unbundling’ of energy legislation. A similar pattern applies to hydrogen, as potential demand and supply centres are unevenly distributed among the Länder, and a connecting transport infrastructure does not yet exist. This interdependence must be addressed, otherwise there is a risk of negative externalities recurring, leading to inefficient policies and delayed transformation. Building on previous research on intergovernmental relations, we investigate coordination processes on hydrogen with a focus on Germany for two reasons: first, Germany represents a characteristic case of cooperative federalism; and second, Germany faces challenges typical of an advanced energy transition. In doing so, we aim to gather empirical information on the presumed coordination deficit in the energy transition. Our research will contribute to a deeper understanding of energy transition processes in federal settings, particularly as recent research shows an increasing degree of ‘de facto administrative federalism’ or a ‘Germanisation’ in dual federal systems, explained by the centralization of policy making (Mueller and Fenna Citation2022, 526).

Analytic Framework

Addressing our first research question, we understand the fragmentation of the German hydrogen strategies as inconsistent, or even conflicting, ‘calculation[s] of objectives, concepts, and resources’ (Yarger Citation2006, 5). Thus, fragmentation represents the opposite of a coordinated outcome, being the ‘end-state in which the policies and programmes of government are characterized by minimal redundancy, incoherence and lacunae' (Peters Citation1998, 296). Coordination can also be conceptualized as a sequence, where coordination processes – the ‘act of managing interdependencies’ (Malone and Crowston Citation1994, 90) – ideally lead to a coordinated outcome. Between these stages, a coordination output can possibly be observed in the form of joint declarations or agreements (Schnabel and Hegele Citation2021, 543).

With regard to our second research question, we argue that the federal fragmentation of the energy transition, observed by the federalism literature, results from a deficit in coordination processes between, and within, the political levels. We, therefore, also expect fragmentation in hydrogen issues, if coordination processes do not evolve.

As we examine coordination in the context of federal intergovernmental relations, we distinguish between horizontal coordination among the Länder, and vertical coordination between the Länder and the federal government. In multi-level systems, challenges also arise from intragovernmental rules that bind coordinating actors (Benz Citation2004, 133). Particularly in the case of cross-cutting issues, such as hydrogen, different allocations of interests and responsibilities within governments are likely to affect intergovernmental coordination (Hegele Citation2021). To capture inter- and intragovernmental coordination analytically, we adapt Christensen and Lægreid’s (Citation2008) forms of coordination of public administration to the federal system. The resulting fourfold table () structures data collection and analysis along two dimensions. The internal dimension describes coordination within a government, horizontally between ministries, and vertically between the political leadership and the administrative level. The external dimension reflects intergovernmental relations in the form of horizontal coordination between the constituent units of a federation; and vertical coordination between the constituent units and the federal government.

Table 1. Forms of governmental coordination in federations.

Furthermore, coordination processes can take place in both informal and formalized settings, depending on the degree of institutionalization (Chisholm Citation1992). Also, coordination can be organized symmetrically in the form of multilateral participation of all stakeholders, or more asymmetrically in bi- and trilateral processes (Bolleyer Citation2009, 69). The four forms outlined in are open to those additional aspects.

Although coordination is considered a necessary consequence of the division of labour and specialization in order to address complex problems in an organization’s environment (Dearborn and Simon Citation1958; Scharpf Citation1972, 169), often enough organizations do not coordinate sufficiently. Especially within public administration, sub-organizational units protect their own turfs, i.e. resources, formal jurisdiction, and mission. Individuals in specialized organizations also have certain professional beliefs about specific policy problems that can subsequently hinder coordination (Peters Citation2018, 5). This reflects observations from federalism research that portfolio allocation affects intergovernmental coordination (Hegele Citation2021). As mentioned above, coordination is regularly compromised by geographical interests and ideological or party-strategic considerations (Auel Citation2014), which, in turn, can also affect internal coordination processes in coalition governments (Husted and Danken Citation2017).

Data & Methodology

We apply a qualitative research design based on official documents and interview data, which we analyze using qualitative content analysis (Mayring Citation2014). The units of analysis are the governments of the German Länder that constitute the lower tier of the federal system. We use a positive case selection and include all Länder that had published an official governmental hydrogen strategy by August 31, 2022. By this date, all Länder, except Berlin and Rhineland-Palatinate, had published hydrogen strategies or road maps. In total, there are 12 strategy documents, since the northern Länder (Bremen, Hamburg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Lower Saxony, and Schleswig-Holstein) have published a joint Northern German Hydrogen Strategy and only Schleswig-Holstein has issued a separate government strategy. The eastern Länder of Brandenburg, Saxony, and Saxony-Anhalt have published a joint strategy document in advance of their individual strategies.

As the first step of our analysis, we assess fragmentation by comparing the regional hydrogen strategies. Using the NHS as a benchmark, we develop four categories for qualitative coding (see Annex I).Footnote1 The NHS evaluates the role of hydrogen, sets goals and ambitions (such as the establishment of 5GW of hydrogen production capacity in Germany by 2030), and defines measures for production and application (divided into action fields such as transport, industry, heating and infrastructure, and international trade) (BMWi Citation2020).

The first coding category captures the overarching strategic purpose assigned to the development of hydrogen technologies. Since hydrogen is commonly considered a new issue in energy policy, purpose is divided into three subcategories corresponding to the three energy policy objectives: economic viability, environmental impact, and security of supply (Schubert, Thuß, and Möst Citation2015, 46). The second category captures strategic goals by coding statements about the intended role of the Länder in the future hydrogen economy. Literature on the hydrogen market ramp-up indicates different views on the relevance or desirability of different hydrogen supply types, hydrogen application, and the importance of hydrogen imports (Ueckerdt et al. Citation2021). We capture this with the third category anticipated pathways. Finally, we code projected instruments with which the market ramp-up should be promoted. We distinguish between regulation, financial support, administrative action and spatial planning. If the frequency and the characteristics of the (sub-)categories vary strongly between the documents, this indicates a fragmented strategic outcome.

To gather information about coordination processes on the formulation and implementation of the different hydrogen strategies, we conducted 14 expert interviews (via web/phone conferences) with representatives of the responsible ministries in the Länder governments. The interviewees are heads of units or desk officers and were identified via publicly available organization plans and subsequent personal correspondence. The interviewees belong to the ministries of environment, or to the ministries of economics, as the allocation of responsibility for hydrogen varies among the Länder. To create a trusting environment and to increase the willingness to provide information, the interview partners were guaranteed anonymity. The expert interviews followed a semi-structured approach, enabling comparability while allowing interviewees to provide additional insights. The interview guidelines are based on the previously presented analytical framework, and group the research questions into four topics and 16 interview questions (Annex II). The first topic covers the purpose of hydrogen and the strategic role of the Länder in the market ramp-up. The second topic addresses the internal coordination of the strategy formulation; the third topic external-horizontal coordination; and the fourth topic external-vertical coordination. In the following sections, we use the abbreviations and IDs as applied in to refer to Länder, interviews and strategies.

Table 2. Used abbreviations for Länder (states), interviews, and strategies.

Federal Fragmentation of Hydrogen Strategies

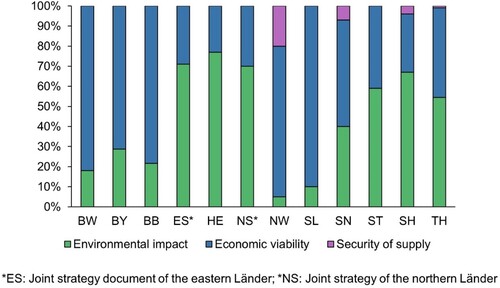

In this section, we assess the fragmentation of the hydrogen strategies of the Länder. First, we examine the strategic purpose the Länder attach to hydrogen and the related technologies. indicates the fragmentation of energy policy objectives in the strategies by comparing the coverage of the three energy objective codes. Economic viability is mentioned most frequently (58% coverage), since positive effects of technology development on regional wealth and employment are expected. Environmental impact is also frequently mentioned (39% coverage), since all strategies assign hydrogen technologies an important role in decarbonization. However, differences between strategies are evident, with some Länder placing more emphasis on economic viability and others on environmental impact. Security of supply plays a noticeably smaller role in the strategies (4% coverage). Since all strategies were published before the Russian assault on Ukraine and the related energy crisis, it can be assumed that security of supply would play a greater role in the meantime.

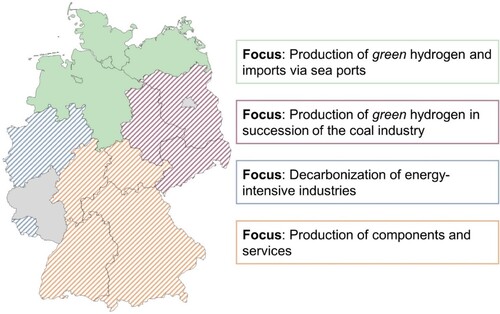

Differences can also be found in the strategic goals. In their respective joint documents, both the northern Länder (HB, HH, MV, NI, SH) as well as the eastern Länder (BB, SA, SN) intend to play a major role in hydrogen production. The former due to high potentials for wind energy in the North and Baltic Sea (WVNK Citation2019, 10) and the latter as a possible response to the structural change caused by the phase-out of coal-fired power generation (SMUL Citation2020, 3). In contrast, the strategies of the southern Länder (BW, BY, HE, TH) primarily focus on promoting the development and future global marketing of hydrogen technologies. While this also applies to the strategies of the two western Länder (NW, SL) they focus on the perspectives of the local energy-intensive industry, especially steel production (MWAEV Citation2021, 20; MWIDE Citation2020, 9).

With regard to the anticipated pathways of the market ramp-up, we find similarity on the importance of hydrogen imports. All strategies expect high demand for imports in the long term. Still, the need for domestic production is emphasized by both the Länder with limited production capacities in order to cover short-term demand (UMBW Citation2020) and to demonstrate expertise (STMWI Citation2020, 10), and by the Länder that perceive economic opportunities. However, the Länder differ significantly on the issue of hydrogen production. Although all regional strategies emphasize that hydrogen should be produced exclusively by renewable energies (green) in the long term, seven strategies mention hydrogen produced from fossil sources as a transitional option. Hesse emphasizes hydrogen production via pyrolysis of methane and ‘by-product hydrogen’, which is (already) produced in the local chemical industry by grid electricity (HMWEVW Citation2021, 4). In addition to pyrolysis, five Länder (BB, NW, SN, ST, TH) highlight the production of blue hydrogen, via steam methane reforming, in combination with carbon capture and storage (CCS) as a viable option for a ‘fast and cost-efficient market ramp-up’ (MWIDE Citation2020, 10).

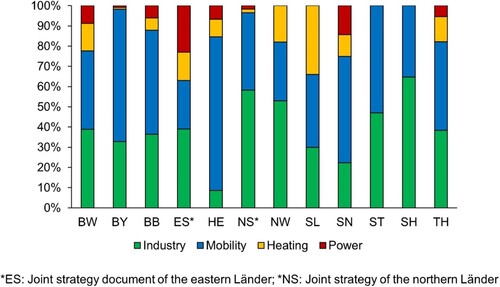

On the demand side, all strategies prioritize specific sectors. As indicates, mobility and industry are the central sectors addressed by the strategies. However, the strategies deviate from another when it comes to specific applications. For example, the strategy of Baden-Württemberg stresses hydrogen demand in the cement industry (UMBW 2022, 29), while the strategy of Thuringia points out the relevance of hydrogen for glass production (TMUEN Citation2021, 7). Although all Länder highlight the importance of hydrogen for heavy-duty transport (trucks, trains, ships, etc.), only Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria emphasize passenger cars (STMWI Citation2020, 13). Heating seems to play a minor role, but still the western and the eastern Länder give it priority in the short term. The use of hydrogen in power supply is low priority across all strategies.

To achieve their strategic goals, the Länder define projected instruments for promoting the market ramp-up of hydrogen technologies. However, there are no significant differences between the Länder in this dimension. All strategies include financial support for private investments in hydrogen projects and research (MELUND Citation2020, 8), as well as administrative action, such as public procurement of hydrogen technologies for public fleets and streamlining of permission processes.

A comparison of the strategies indicates broad consensus on the increasing importance of hydrogen for decarbonization and regional economic development. However, there are significant differences in the strategic goals associated with hydrogen, which form regional clusters, as illustrated in . With the exception of the northern Länder, there are diverging preferences and expectations for the market development of hydrogen. Also, the NHS differs from specific Länder strategies, as it does not provide a clear position on the role of fossil hydrogen, and gives low priority to the heat and passenger car sectors (BMWi Citation2020, 3).

Figure 3. Fragmentation of hydrogen strategies. Adopted from Flath, Knodt, and Kemmerzell Citation2023.

Coordination of Hydrogen Strategies

This section addresses our second research question and examines the extent to which this fragmentation can be explained by specific patterns of coordination. We first investigate the level of coordination along the dimensions of our analytic framework (), and then discuss whether any coordination deficits can explain the fragmentation observed across the strategies.

Horizontal-internal Coordination

The horizontal coordination processes within the Länder governments vary depending on the allocation of responsibility for energy and hydrogen policy. When the hydrogen strategies were formulated, responsibility for energy lay with the ministries of the environment in eight cases, with the ministries of economics in five cases, and with a separate energy ministry in one case. All Länder were governed by coalitions: in eight Länder, two parties; and in six Länder, three parties formed the government.

In Bavaria, North Rhine-Westphalia, and Saarland, the ministries of economics, and in Baden-Württemberg, the Ministry of the Environment, did not share responsibility with other ministries. This resulted in a ‘one-way process’, with minimal and mostly informal engagement from other ministries [#2]. While in Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, and North Rhine-Westphalia the strategies were approved by the cabinet, in Saarland, the strategy was only informally discussed with the office of the prime minister before being published solely by the Ministry of Economics [#10]. The situations in Hesse, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia were different, as the formulation of the strategies was coordinated in existing or specially established inter-ministerial working groups (IMWGs) to cover turfs and address dispersed responsibility for hydrogen, as in SaxonyFootnote2:

After a long discussion, the Ministry of the Environment and Energy was given responsibility for hydrogen. Nevertheless, hydrogen, for example in mobility, lies with the Ministry of Economics and Transport. The structural change aspect lies with the Ministry for Structural Change, which is entrusted with permitting processes. [#11]

The horizontal-internal coordination within the northern Länder was strongly influenced by the horizontal-external dimension. Due to prior intergovernmental cooperation, the ministries of economics became responsible for the hydrogen strategy in Bremen, Hamburg, Lower Saxony, and Schleswig-Holstein, although energy was the responsibility of the ministries of the environment. The horizontal-external coordination of the formulation process also led to tight deadlines and limited capacities, due to which internal coordination during formulation was only possible to a limited extent [#8]. In Schleswig-Holstein, the green-controlled Energy Transition Ministry introduced a separate strategy, while the joint strategy of the northern Länder ‘was not easily supported’ [#4].

Vertical-internal Coordination

Regarding the vertical coordination within the governments, all interviewees stated that hydrogen strategy development was politically motivated and driven by top-down agenda setting from the political leadership in the ministries. In Hamburg, the responsible senatorFootnote3 initiated the process of the Northern German Hydrogen Strategy [#5]. In Bavaria, the goal of developing a hydrogen strategy was formulated in the coalition agreement of the two governing parties in 2018 and was the starting point for the strategy process [#2]. Early adopted strategies, and ongoing announcement of other strategies, represented an ‘external pressure’ [#12] on the remaining Länder to also develop a strategy. Also, the NHS was an incentive to have an integrated strategy ‘to benefit maximally from these funding billions’ [#6].

After the political agenda was set, the draft strategies were formulated at the administrative working level and passed a review process across the ministerial hierarchy. Political salience was reflected in a strong interest by the leadership during formulation. In some cases, the ministers informed themselves about the status of the draft strategies directly at unit level [#5; #9]. To improve networking and coordination and ‘to overcome inertia effects in the administration’, the Ministry of Economics in Hamburg established a special unit ‘Hydrogen Economy’ outside the regular administrative hierarchy as a contact point of hydrogen matters for both internal and external actors [#5].

Horizontal-external Coordination

Multilateral coordination between the Länder governments on energy issues usually takes place in the institutionalized conferences of ministers, such as the Conference of Ministers of Economics (WMK) and the Conference of Ministers of the Environment (UMK), as well as the Meeting of Energy Ministers (EMT). The latter was founded in 2019 as an informal meeting of the energy ministers and is supposed to become an official conference in the future. In their first meeting in May 2019, the energy ministers agreed on the general importance of hydrogen for sector integration (EMT Citation2019). Due to its ‘virulence in the political arena’, hydrogen has been on the agenda of the conferences and meetings since then from time to time, but these discussions have mainly been limited to joint statements on federal government projects and there has been no coordination among the Länder [#5]. Also, the interviewees recognize that the strategies of the Länder hardly played a role in the conferences and meetings. The locational interests (especially between north and south) and different party affiliations of the respective ministers, only allow hydrogen policy coordination of the Länder within the framework of the conferences ‘at a too high altitude’ [#7]. The effects of portfolio combination already described above can be problematic. For example, the UMK calls for the exclusive use of green hydrogen (UMK Citation2020, 24), while the WMK emphasizes the temporary use of ‘options other than green hydrogen as well’ (WMK Citation2022, 9):

I think the problem is that we have far too many players and far too many conflicting interests at these sectoral ministerial conferences. All the decisions remain at a very superficial level. It will not be possible to agree on detailed common positions, because the interests between north and south, and between east and west, are far too great. [#7]

I would like this working group to function more as an alliance of the Länder, also toward the federal government. I notice that individual Länder are not satisfied with what is happening at the federal level – keyword: hydrogen regulation – but then individually protest. That makes it too easy for the federal government. If 16 Länder, or as many as possible, act in concert, we add a bit more political weight to the scales. [#3]

Brandenburg, Saxony, and Saxony-Anhalt also attempted to develop a regional hydrogen strategy, which ultimately was ‘not politically feasible’ [#11]. As the ‘colour constellation was so difficult’, meaning the different party compositions of the coalition governments, ‘it was assumed that such a strategy would not have gone through so easily’ [#3]. The common understanding achieved was finally published as a key points paper, which does not represent a governmental strategy as it was only adopted by the respective energy ministries [#12]. The main reasons for the failed cooperation were different views on the production of hydrogen and the sector allocation of its use [#3; #11]. Consequently, the three Länder published individual hydrogen strategies.

The government of Brandenburg formulated its own strategy and has coordinated bilaterally with its neighbour Berlin, which is not developing a strategy for itself [#3]. However, despite strong interdependencies in the metropolitan region, no joint governmental hydrogen strategy was developed, since coordination did not always go ‘completely smoothly’ and Brandenburg wanted to retain the final decision-making authority [#3].

The interviewees were not aware of other deliberate horizontal-external coordination processes – multilateral, regional or bilateral. Instead, coordination took place primarily in the form of mutual adaptation: ‘There were already several strategies on the market, and of course, we took a look – you don’t necessarily have to reinvent the wheel’ [#14]. Even though there was little bilateral coordination during strategy development among the Länder, this might change during implementation and project planning of the first activities. Here the southern Länder are planning a stronger regional exchange, especially within the framework of co-financed cross-border projects [#6].

Vertical-external Coordination

In legislation, the Bundesrat is the formal arena for vertical-external coordination. Even though hydrogen was often on the agenda for the plenum since 2019, the Bundesrat’s de facto role was to comment on legislation at federal level or to request federal actions via non-binding resolutions (e.g. Bundesrat Citation2019). However, a request for regulatory prerequisites for a hydrogen grid infrastructure, which included a draft proposal from the Bundesrat (Bundesrat Citation2020, 8–13), was rejected by the federal government (Bundesregierung Citation2020, 16–17).

Vertical-external coordination on hydrogen policies started after the NHS was published in June 2020. During the formulation process itself, there was little [#4] to no [#3; #6] involvement of the Länder. The formulation of the National Hydrogen Strategy was ‘a very isolated process’ [#11] or ‘more of a closed shop with the industry’ [#12]. Only the interviewee from Hamburg stated that there was an informal exchange on the NHS on ‘many channels’, as well as a ‘matching’ between strategies [#5]. This deviant case might be a consequence of Hamburg’s role as an early mover and as a location of important R&D projects, which motivated policy makers in the federal government to benefit from regional experiences.

With the National Hydrogen Strategy, the German government has established two new coordinating bodies: The National Hydrogen Council and the Bund-Länder Working Group on Hydrogen (BMWi Citation2020, 15). The National Hydrogen Council is an expert group appointed by the federal government. It gathers 26 experts from industry, science, and civil society who advise on the implementation and development of the National Hydrogen Strategy. Four Länder, each representing a geographical area, attend the meetings of the National Hydrogen Council as guests without voting rights. The concrete participation is organized within the Länder groups. While the northern, southern, and eastern Länder take turns [#1; #5], North Rhine-Westphalia permanently represents the other two western Länder, Rhineland-Palatinate and Saarland, in the National Hydrogen Council [#9]. However, participation of the Länder was not initially intended by the federal government and was only established after massive interventions of the Länder [#3; #12].

The Bund-Länder Working Group on Hydrogen is in turn supposed to be a platform for ‘close cooperation between the federal government and the Länder’, as was announced in the NHS but not specified (BMWi Citation2020, 16). According to interviews, the working group meets two to four times a year [#5; #13] and consists of representatives of the responsible federal ministries, as well as the heads of the energy departments of the Länder. The meetings typically last three hours, two of which are spent by federal ministries reporting on their activities and current developments. In the remaining hour, the Länder can ask questions or report on their own activities [#3]. Some interviewees consider the working group as an important arrangement [#6; #13], while others attribute a ‘questionable quality’ [#9] to it. Reasons for the latter are the low frequency of meetings in the face of a highly dynamic policy field [#4], as well as redundancy due to thematic and personnel overlaps with the Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technology Working Group [#14]. Since the effective speaking time is limited to three to four minutes per Länder representative, the Bund-Länder working group on Hydrogen is primarily perceived as an information channel of the federal government and not an institution designed for exchange [#11; #12].

Project-based coordination within the Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) was positively emphasized by interviewees [#3; #9; #10; #11; #13]. IPCEIs are private sector projects that can be announced by EU Member States to the European Commission and, if accepted, are subject to special state aid rules. The federal government selected 62 hydrogen projects across Germany as IPCEIs. Within the IPCEIs, the federal government and the Länder coordinate closely, since public funding of the IPCEIs is shared between the federal government (70%) and the Länder where the specific project is located (30%). The eastern Länder and the federal government, for example, have institutionalized regular exchanges through the regional IPCEIs [#3]. The Länder view coordination with the federal government in the IPCEIs as more substantial than during the formulation of the National Hydrogen Strategy. This may be explained by the lower level of politicization of the IPCEIs, and because ‘we [the Länder] co-finance – then you also inevitably play a strong role’ [#9].

Lack of Coordination as a Cause of Strategic Fragmentation?

Analysis shows a significant fragmentation of the hydrogen strategies of the Länder and the federal government. Although the Länder governments jointly emphasize the importance of hydrogen for climate protection and for the German economy at ministerial conferences and meetings, a joint strategic approach has yet to be established. It has also become apparent that inadequate coordination between the federal government and the Länder, as well as among and within the Länder, largely accounts for this fragmentation.

When considering the vertical-external dimension, it becomes apparent that the lack of multilateral coordination between the federal government and the Länder in the formulation of the NHS is a key factor contributing to fragmentation. The only observed coordination on the NHS was bilateral and informal between the federal government and Hamburg, indicating a highly selective coordination strategy by the federal government. After the formulation of the NHS, vertical-external coordination, aside from the ICPEIs, is still largely absent. Although the federal government institutionalized a joint working group on hydrogen, it is perceived more as a one-way communication channel by the Länder. These findings align with those of previous studies, which have noted that the federal government follows a top-down approach in the energy transition.

In the horizontal-external dimension, the different strategies and approaches reflect a lack of multilateral coordination among the Länder. Despite high salience of the issue, hydrogen strategies were not discussed in intergovernmental conferences. Even in the existing informal Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technology Working Group of the Länder, exchange on the hydrogen strategies did not take place. However, the Länder can be divided into four clusters based on similar strategic goals in their strategies. Despite similar goals, different approaches can be observed regarding the targeted pathways among the southern and the western Länder. This fragmentation can be explained by an almost complete absence of horizontal-external coordination. In particular the Länder that published a hydrogen strategy at an early stage (BW, BY, NW) did not consider an intensive strategic coordination necessary [#1; #2; #9]. In the case of the eastern German cluster, initial coordination attempts between Brandenburg, Saxony, and Saxony-Anhalt failed, ultimately resulting in different strategic assessments of hydrogen production and usage. Only among the northern Länder did coordination turn out successfully, leading to a coherent common hydrogen strategy. Compared with the external-vertical dimension, intergovernmental coordination between the Länder is, therefore, not completely absent, but takes place only on a small scale within regional clusters.

The inclusion of the internal dimension highlights the partial relationship of (non-)coordination between governments and coordination problems within governments. In the eastern cluster, horizontal-internal coordination problems with dispersed responsibilities, differing portfolio allocation of hydrogen, and high politicization, resulted in the failure of a common approach and the emergence of fragmented strategies. In contrast, the northern German Länder drafted a coherent strategy due to efficient internal-horizontal coordination, with clear responsibility assigned to one ministry and effective external coordination resulting from similar portfolio allocation. The formulation of the northern German hydrogen strategy also indicates the impact of external coordination on internal coordination. Agenda-setting for a joint strategy took place within established external coordination routines. This shifted responsibility for hydrogen within the governments to the ministries of economics, thereby effectively containing internal conflicts. Coordination issues are also partly an indicator of party-political conflicts, not only leading to delays in strategy development within coalition governments (such as HE and SN), but also preventing a joint strategy (as in Berlin and Brandenburg).

Overall, it is evident that there was little strategic coordination on hydrogen between the Länder and the federal government. Although intergovernmental coordination among the Länder was more prevalent, it was limited to bilateral coordination, and coordination within clusters that shared similar goals. There was neither multilateral coordination between the majority of the Länder nor between all of them. However, as has been shown with reference to the northern Länder, formal coordination was more successful than informal coordination, as it led to greater strategic coherence.

Conclusion

This analysis indicates that, despite consensus on the great importance of hydrogen, the hydrogen strategies of the German federal government and the Länder differ in terms of strategic goals and expectations for market ramp-up. Federalism scholarship regularly explains the fragmentation of energy policy by a presumed (but not directly observed) lack of coordination between political levels. In an explorative-qualitative analysis of document and interview data, we find that fragmentation of the hydrogen strategies can indeed be explained by lacking both external and internal coordination. In doing so, this article applies a concept of coordination that integrates interactions between inter-governmental and intra-governmental coordination. Externally, vertical multilateral involvement of the Länder in the formulation of the NHS was absent. Horizontal strategic coordination occurred only within groups of neighbouring Länder, where geographical, party-political and sectoral interest have dwindled. We also found interactions between intragovernmental coordination and intergovernmental coordination, in that the allocation of hydrogen in government portfolios significantly determines external coordination and, surprisingly, vice versa.

However, the research design has some limitations. The cross-sectoral analysis only captures process dynamics to a limited extent. There were 28 months between the first and the last published strategy. Changes in the political environment, such as public discourse, may have affected strategy development differently. Since most of our interviews were conducted with administrative staff, aspects of political leadership can only be assessed indirectly, as in the case of Hamburg. Some interviews [#2; #6] suggest that stronger coordination is unlikely, solely due to high transaction costs. Therefore, it would be beneficial to provide a comprehensive explanation of the conditions for coordination. Ultimately, we analyzed the strategies, not the implementation of outlined policies, which were not in place at the time of the study. To what extent the Länder will adopt their own policies or federal policies, and coordinate implementation, remains a research desideratum: It is possible that uncoordinated production and sector applications yield a spatial mismatch between hydrogen demand and supply.

As shown by the example of Germany, territorial interests have not hindered the agenda-setting of hydrogen but have instead influenced the strategic focus. Also, the hydrogen topic intersects established portfolios, and its integration can vary between governments, thus constraining intergovernmental relations through intra-governmental processes. We expect that spatial interdependencies of hydrogen will be observable in other federal systems, and, while elements of functional separation of powers emerge across federations, coordination will become increasingly important. Finally, we expect that higher coherence in the allocation of hydrogen in government portfolios leads to better intergovernmental coordination and perhaps even more efficient governance of the hydrogen market ramp-up. Case studies across different federal configurations, and comparative analyses, can provide valuable insights into the federal dynamics of the hydrogen market ramp-up, which will be critical for the advancement towards climate-neutrality.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Document coding was conducted with the MAXQDA software.

2 The authors translated quotes from interviews that Lucas Flath conducted in German.

3 In the German city-states (Stadtstaaten) Berlin, Bremen and Hamburg, ministers are referred to as senators.

References

- Abromeit, Heidrun. 1992. Der verkappte Einheitsstaat. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

- Auel, Katrin. 2014. “Intergovernmental Relations in German Federalism: Cooperative Federalism, Party Politics and Territorial Conflicts.” Comparative European Politics 12 (4-5): 422–443. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2014.13.

- Balthasar, Andreas, Miranda A. Schreurs, and Frédéric Varone. 2020. “Energy Transition in Europe and the United States: Policy Entrepreneurs and Veto Players in Federalist Systems.” The Journal of Environment & Development 29 (1): 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496519887489.

- Benz, Arthur. 2004. “Multilevel Governance — Governance in Mehrebenensystemen.” In Governance - Regieren in komplexen Regelsystemen: Eine Einführung, edited by Arthur Benz, 125–146. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Benz, Arthur. 2019. “Koordination der Energiepolitik im deutschen Bundesstaat.” der moderne staat 12 (2): 299–312. https://doi.org/10.3224/dms.v12i2.01.

- Benz, Arthur, and Jörg Broschek. 2021. “Transformative Energy Policy in Federal Systems: Canada and Germany Compared.” Canadian Journal of European and Russian Studies 14 (4): 56–78. https://doi.org/10.22215/cjers.v14i2.2762.

- BMWi (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie). 2020. Die Nationale Wasserstoffstrategie. Berlin.

- Bolleyer, Nicole. 2009. Intergovernmental Cooperation: Rational Choices in Federal Systems and Beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bolleyer, Nicole. 2018. “Challenges of Interdependence and Coordination in Federal Systems.” In Handbook of Territorial Politics, edited by Klaus Detterbeck, and Eve Hepburn. 45–60. Northampton (MA): Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bundesrat. 2019. Beschluss des Bundesrates: Entschließung des Bundesrates zur Schaffung eines Rechtsrahmens für eine Wasserstoffwirtschaft. Drucksache 450/19. Berlin.

- Bundesrat. 2020. Stellungnahme des Bundesrates: Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Änderung des Bundesbedarfsplangesetzes und anderer Vorschriften. Drucksache 570/20. Berlin.

- Bundesregierung. 2020. Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Änderung des Bundesbedarfsplangesetzes und anderer Vorschriften: Stellungnahme des Bundesrates und Gegenäußerung der Bundesregierung. Drucksache 19/23491. Berlin.

- Chisholm, Donald. 1992. Coordination Without Hierarchy: Informal Structures in Multiorganizational Systems. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Lægreid. 2008. “The Challenge of Coordination in Central Government Organizations: The Norwegian Case.” Public Organization Review 8 (2): 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-008-0058-3.

- Dearborn, DeWitt C., and Herbert A. Simon. 1958. “Selective Perception: A Note on the Departmental Identifications of Executives.” Sociometry 21 (2): 140–144. https://doi.org/10.2307/2785898.

- Emodi, Nnaemeka V., Heather Lovell, Clinton Levitt, and Franklin. Evan. 2021. “A Systematic Literature Review of Societal Acceptance and Stakeholders’ Perception of Hydrogen Technologies.” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 46 (60): 30669–30697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.06.212.

- EMT (Energieministertreffen). 2019. Wasserstoffstrategie (Reallabore, regulatorische Rahmenbedingung). Hannover.

- Flath, Lucas, Michèle Knodt, and Jörg Kemmerzell. 2023. “Die Wasserstoffstrategien von Bund und Ländern: Koordinationsdefizite im Föderalen System?.” In Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2023: Nomos. (forthcoming)

- Hanley, Emma S., J. P. Deane, and BÓP Gallachóir. 2018. “The Role of Hydrogen in low Carbon Energy Futures–A Review of Existing Perspectives.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 82: 3027–3045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.10.034.

- Hegele, Yvonne. 2021. “The Impact of Department Structure on Policy-Making: How Portfolio Combinations Affect Interdepartmental Coordination.” Public Policy and Administration 36 (4): 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076720914361.

- Hegele, Yvonne, and Nathalie Behnke. 2017. “Horizontal Coordination in Cooperative Federalism: The Purpose of Ministerial Conferences in Germany.” Regional & Federal Studies 27 (5): 529–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2017.1315716.

- HMWEVW (Hessisches Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Energie, Verkehr und Wohnen). 2021. Die Potenziale des Wasserstoffs für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz erschließen: Eine Strategie für Hessen. Wiesbaden.

- Hueglin, Thomas O., and Alan Fenna. 2015. Comparative Federalism: A Systematic Inquiry. 2. ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Husted, Thurid, and Thomas Danken. 2017. “Institutional Logics in Inter-Departmental Coordination: Why Actors Agree on a Joint Policy Output.” Public Administration 95 (3): 730–743. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12331.

- IEA (International Energy Agency). 2021. Hydrogen in North-Western Europe: A Vision Towards 2030. Paris.

- Kemmerzell, Jörg. 2022. “Energy Governance in Germany.” In Handbook of Energy Governance in Europe, edited by Michèle Knodt, and Jörg Kemmerzell, 667–708. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Kemmerzell, Jörg, and Michèle Knodt. 2020. “Governanceprobleme der Sektorkopplung: Über die Verknüpfung der Energie- mit der Verkehrswende.” In Baustelle Elektromobilität, edited by Achim Brunngräber, and Tobias Haas, 355–381. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Knodt, Michèle, Michael Rodi, Lucas Flath, Michael Kalis, Jörg Kemmerzell, Falko Leukhardt, and Christian Flachsland. 2022. Mehr Kooperation wagen: Wasserstoffgovernance im deutschen Föderalismus: Interterritoriale Koordination, Planung und Regulierung. Kopernikus-Projekt Ariadne, Potsdam.

- Kovač, Ankica, Matej Paranos, and Doria Marciuš. 2021. “Hydrogen in Energy Transition: A Review.” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 46 (16): 10016–10035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.11.256.

- Kropp, Sabine. 2010. Kooperativer Föderalismus und Politikverflechtung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Malone, Thomas W., and Kevin Crowston. 1994. “The Interdisciplinary Study of Coordination.” ACM Computing Surveys 26 (1): 87–119. https://doi.org/10.1145/174666.174668.

- Mayring, Philipp. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Klagenfurt. URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173.

- MELUND (Ministerium für Energiewende, Klimaschutz, Umwelt und Natur). 2020. Wasserstoffstrategie.SH: Wasserstoffstrategie des Landes Schleswig-Holstein. Kiel.

- Monstadt, Jochen, and Stefan Scheiner. 2016. “Die Bundesländer in der Nationalen Energie- und Klimapolitik: Räumliche Verteilungswirkungen und Föderale Politikgestaltung der Energiewende.” Raumforschung und Raumordnung 74 (3): 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13147-016-0395-6.

- Mueller, Sean, and Alan Fenna. 2022. “Dual Versus Administrative Federalism: Origins and Evolution of Two Models.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 52 (4): 525–552. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjac008.

- MULE (Ministerium für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Energie). 2021. Wasserstoffstrategie für Sachsen-Anhalt. Magdeburg.

- Münch, Ursula. 2013. “Energiewende im Föderalen Staat.” In Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2013, 31–47. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- MWAE (Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Arbeit und Energie Brandenburg). 2021. Maßnahmenkonkrete Strategie für den Aufbau einer Wasserstoffwirtschaft im Land Brandenburg. Potsdam.

- MWAEV (Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Arbeit, Energie und Verkehr Saarland). 2021. Eine Wasserstoffstrategie für das Saarland: Saarland 2030 - auf dem Weg zum Wasserstoffland. Saarbrücken.

- MWIDE (Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Innovation, Digitalisierung und Energie des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen). 2020. Wasserstoff Roadmap. Nordrhein-Westfalen. Düsseldorf.

- Noussan, Michel, Pier P. Raimondi, Rossana Scita, and Manfred Hafner. 2021. “The Role of Green and Blue Hydrogen in the Energy Transition — A Technological and Geopolitical Perspective.” Sustainability 13 (1): 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010298.

- Oeter, Stefan. 2006. “Federal Republic of Germany.” In Legislative, Executive, and Judicial Governance in Federal Countries, edited by Katy Le Roy, and Cheryl Saunders, 135–164. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Ohlendorf, Nils, Meike Löhr, and Jochen Markard. 2023. “Actors in Multi-Sector Transitions - Discourse Analysis on Hydrogen in Germany.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 47: 100692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2023.100692.

- Ohlhorst, Dörte. 2015. “Germany’s Energy Transition Policy Between National Targets and Decentralized Responsibilities.” Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences 12 (4): 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/1943815X.2015.1125373.

- Peters, B. G. 1998. “Managing Horizontal Government: The Politics of Co-Ordination.” Public Administration 76 (2): 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00102.

- Peters, B. G. 2018. “The Challenge of Policy Coordination.” Policy Design and Practice 1 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2018.1437946.

- Pflugmann, Fridolin, and Nicola de Blasio. 2020. “The Geopolitics of Renewable Hydrogen in Low-Carbon Energy Markets.” Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 12 (1): 7–44. https://doi.org/10.22381/GHIR12120201.

- Rossi, Jim. 2016. “The Brave New Path of Energy Federalism.” Texas Law Review 95 (2): 399–466.

- Saurer, Johannes, and Jonas Monast. 2021. “Renewable Energy Federalism in Germany and the United States.” Transnational Environmental Law 10 (2): 293–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102520000345.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 1972. “Komplexität als Schranke politischer Planung.” In Gesellschaftlicher Wandel und politische Innovation. Politische Vierteljahresschrift Sonderheft 4/1972, 168–192. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-88716-0_10.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 1988. “The Joint-Decision Trap: Lessons from German Federalism and European Integration.” Public Administration 66 (3): 239–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1988.tb00694.x.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 1997. Games Real Actors Play: Actor-Centered Institutionalism in Policy Research. Theoretical Lenses on Public Policy. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

- Schill, Wolf-Peter, Jochen Diekmann, and Andreas Püttner. 2019. “Sechster Bundesländervergleich erneuerbare Energien: Schleswig-Holstein und Baden- Württemberg an der Spitze.” DIW Wochenbericht 2019 (48): 882–894.

- Schnabel, Johanna, and Yvonne Hegele. 2021. “Explaining Intergovernmental Coordination During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Responses in Australia, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 51 (4): 537–569. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjab011.

- Schönberger, Philipp, and Danyel Reiche. 2016. “Why Subnational Actors Matter: The Role of Länder and Municipalities in the German Energy Transition.” In Germany’s Energy Transition, edited by Carol Hager, and Christoph H. Stefes, 27–61. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schubert, Daniel K. J., Sebastian Thuß, and Dominik Möst. 2015. “Does Political and Social Feasibility Matter in Energy Scenarios?” Energy Research & Social Science 7: 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.03.003.

- SMUL (Sächsisches Ministerium für Umwelt und Landwirtschaft). 2020. Eckpunktepapier der ostdeutschen Kohleländer zur Entwicklung einer regionalen Wasserstoffwirtschaft. Dresden.

- SMUL (Sächsisches Ministerium für Umwelt und Landwirtschaft). 2021. Die Sächsische Wasserstoffstrategie. Dresden.

- STMWI (Bayrisches Staatsministerium für Wirtschaft, Landesentwicklung und Energie). 2020. Bayrische Wasserstoffstrategie. München.

- TMUEN (Thüringer Ministerium für Umwelt, Energie und Naturschutz). 2021. Thüringer Landesstrategie Wasserstoff. Erfurt.

- Ueckerdt, Falko, Benjamin Pfluger, Adrian Odenweller, Claudia Günther, Michèle Knodt, Jörg Kemmerzell, Matthias Rehfeldt, et al.. 2021. Durchstarten trotz Unsicherheiten: Eckpunkte Einer Anpassungsfähigen Wasserstoffstrategie. Kopernikus-Projekt Ariadne, Potsdam.

- UMBW (Umweltministerium Baden-Württemberg). 2020. Wasserstoff-Roadmap Baden-Württemberg: Klimaschutz und Wertschöpfung kombinieren. Stuttgart.

- UMK (Umweltministerkonferenz). 2020. 95. Umweltministerkonferenz: Ergebnisprotokoll. s.l.

- van de Graaf, Thijs, Indra Overland, Daniel Scholten, and Kirsten Westphal. 2020. “The New Oil? The Geopolitics and International Governance of Hydrogen.” Energy Research & Social Science 70: 101667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101667.

- Wegner, Nils. 2022. Reformansätze zum Planungsrecht von Windenergieanlagen. Würzburger Studien zum Umweltenergierecht 26. Würzburg: Stiftung Umweltenergierecht.

- WMK (Wirtschaftsministerkonferenz). 2022. Beschluss-Sammlung der Wirtschaftsministerkonferenz am 30. Juni 2022 und 1. Juli 2022 in Dortmund. Dortmund.

- Wurster, Stefan, and Christina Köhler. 2016. “Die Energiepolitik der Bundesländer: Scheitert die Energiewende am Deutschen Föderalismus?” In Die Politik der Bundesländer, edited by Achim Hildebrandt, and Frieder Wolf, 283–314. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

- WVNK (Wirtschafts- und Verkehrsminister der norddeutschen Küstenländer). 2019. Norddeutsche Wasserstoffstrategie. s.l.

- Yarger, Harry R. 2006. Strategic Theory for the 21st Century: The Little Book on big Strategy. Carlisle, Pa: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College.