ABSTRACT

Demands for independence have increased across Europe in the last decade, but there are limits to our understanding of what makes secessionist parties more ambiguous or assertive on independence. This article’s original contribution to the literature on regionalist parties in Western Europe is in addressing gaps in understanding of secessionist party strategy. Consequently, its original theoretical contribution is to enrich analysis of secessionist party strategic calculations. It achieves this by advancing analysis of key factors influencing pro-independence parties’ emphasis on their secession claims by modifying a framework of internal and external factors developed by Elias and Mees (Citation2017). It deepens assessment of state-wide impacts on the salience of pro-independence demands, including incumbent central government parties and secessionist parties in other parts of the state. Empirically, the article evaluates the framework’s strengths by examining the case of Plaid Cymru, Wales 2003–2021 drawing on a new dataset and qualitative research.

Introduction

Regionalist parties are increasingly recognized as important, established actors and their ideological positioning on self-governance is their defining characteristic. Whereas their respective constitutional visions vary, the 2010s onwards witnessed a Europe-wide shift as independence demands increased in cases such as Catalonia, Corsica, Galicia, Sardinia, Scotland and Wales (Elias et al. Citation2020, 39–40; Dowling Citation2018; McHarg et al. Citation2016; Duerr Citation2015). The FraTerr analysis of 12 European regions between 1990 and 2018 confirms that calls for independence accounted for 16% of regionalist movements’ constitutional demands in the regions during 2000–2009, with a significant increase after 2010 as calls for independence accounted for 31% of constitutional demands. Since the 2010s, territorial and constitutional challenges to existing states have heightened as more parties have shifted from autonomist to secessionist parties (Massetti Citation2009, 505) (e.g. CDC in Catalonia and BNG in Galicia), thus joining pro-independence parties in Scotland, Bavaria and Corsica calling for establishing independent states. In addition, in many cases, new pro-independence political parties and organizations have formed, including in Catalonia and Sardinia. Another key development is that the salience of pro-independence calls has increased amongst secessionist parties as they become more explicit in foregrounding calls for secession.

Understanding of secessionist party strategy regarding the extent to which they foreground or downplay their independence demands is limited. What explains the degree to which secessionist parties emphasize their calls for independence? In Massetti’s terms (Citation2009, 505), what influences whether a party is an ‘ambiguous’ or a ‘strongly committed’ secessionist placing independence ‘continuously upfront in their discourses and documents’? Consequently, attention needs to be given to understanding the factors that influence the salience of pro-independence parties’ secession demands.

Thus, the central goal of this article is to contribute to this agenda by developing a framework to understand the factors influencing the salience of pro-independence parties’ secession demands alongside their other constitutional demands. To do this, it modifies Elias and Mees’ framework (Citation2017) developed to analyze the factors influencing shifts in the positioning and salience of regionalist parties’ territorial demands to focus on analyzing secessionist parties. It utilizes the vast majority of the framework’s intra-party and external factors and places a greater emphasis on evaluating multi-level influences on the salience of pro-independence demands by strengthening examination of the impact of state-wide developments, namely governing parties at central government level and secessionist party territorial demands elsewhere within the state. Consequently, the article makes an original theoretical contribution to advancing analysis of secessionist party ideology in Western Europe on the centre-periphery cleavage and their strategic calculations.

Empirically, the article investigates the strengths of the modified framework by applying it to examine a specific case, Plaid Cymru (PC), Wales. Known for its ambiguous position on its ultimate constitutional aim, this case departs from the tendency to focus on the most prominent pro-independence parties by investigating a party less likely to be assertive on its secessionist aims where a clear shift has occurred in its emphasis on independence in line with broader European trends.

In terms of its structure, the first section outlines the literature regarding the self-government claims of regionalist parties and makes the case for a framework to understand the salience of secessionist party independence demands by adapting Elias and Mees (Citation2017). The second section outlines the case selection and methodology. It is followed by content analysis findings regarding PC’s constitutional demands, illustrating the shift in the salience of independence between 2003 and 2021. The main section then applies the framework to assess the factors explaining the extent to which PC emphasizes its Welsh independence demands. It argues that applying the framework demonstrates its capacity to develop a comprehensive analysis of the internal and external factors at the state-wide and sub-state levels influencing the relative prioritization of territorial demands by pro-independence parties. State-wide factors intersect and interplay in particular combinations with internal party and sub-state external factors to influence the salience of demands for independence. The conclusion calls for further research to investigate the framework’s potential to analyze the strategic calculations of other pro-independence parties regarding their territorial demands.

Analyzing self-governance claims

Regionalist parties are increasing in number and in prominence as parties of government at the sub-state level, an indicator of their electoral and political success in Western Europe (Hepburn Citation2009, 477–478). Whilst appreciating that regionalist parties’ ideologies are multi-dimensional, aspects including the left-right dimension and their position on European integration (Massetti Citation2009, 502), their distinguishing feature is demanding political reorganization of state territorial structures to achieve sub-state territorial empowerment in the context of economic, political, social, cultural or symbolic interests (Hepburn Citation2009, 482). Their self-government demands vary (De Winter Citation1998, 204–205; Massetti Citation2009, 503) and we can better understand this variation by distinguishing between positioning and salience on the territorial dimension. This distinction has previously been utilized to assess party strategies on two dimensions, the economic left-right and territorial centre-periphery dimensions (e.g. Elias, Szöcsik, and Zuber Citation2015). Here, positioning refers to a regionalist party’s position on the territorial dimension and salience is the extent to which a party selectively emphasizes or de-emphasizes their territorial position based on what they perceive most favourable to the party (Elias, Szöcsik, and Zuber Citation2015, 841). Both form part of a party’s strategic choices, are not fixed and may shift. As discussed below, in the main, existing explanatory frameworks have focused on explaining shifts in regionalist parties’ positioning on territorial demands. Less attention has been given to understanding the second aspect of secessionist party strategy: the factors affecting the salience of their secession demands.

The most relevant literature is frameworks that focus on the determinants of regionalist party positions on self-governance. Building on previous studies, they seek to account for all major Western European regionalist parties and the impact of social, institutional/ political environments, and ideological consistency (see Massetti Citation2009). Specific dimensions investigated include the relationship between regionalist party centre-periphery positioning, on the left-right dimension and a region’s economic status (Massetti and Schakel Citation2015), and the significance of centre-periphery and left-right positioning to stances on European integration (Massetti and Schakel Citation2021). In explaining changes in the ideologies of regionalist parties, in the main, frameworks seek to analyze the factors contributing to two-way shifts in regionalist parties’ positioning between moderate demands for greater self-rule to more radical demands for secession (see Massetti and Schakel Citation2016).

Two studies assessing the impact of the post-2008 global economic crisis and austerity also aim to understand changes in regionalist parties’ territorial demands, combining attention to positioning and salience. In Scotland and Catalonia, Béland and Lecours (Citation2021) argue that a recession and central government responses may provide opportunities for nationalist politicians to blame the state, particularly in multi-national states with more centralized state structures. Consequently, in contrast to Québec, the politics of austerity supported Catalan secession efforts and the UK’s austerity programme influenced the Scottish independence referendum debate. Elias and Mees (Citation2017) highlight the financial crisis’ contribution to shifting Catalan regionalist parties positioning towards calling for fiscal sovereignty and shifting the salience of Basque independence demands.

Whilst there is clearly richness in approaches to explain change in regionalist parties’ positioning between demanding greater self-rule and calling for secession, less attention has been given to explaining shifts in salience, the relative prominence given to pro-independence demands within secessionist party strategy. Analysing the strategic choices of regionalist parties on the two-dimensional strategy of territorial and economic dimensions has a different objective (e.g. Elias, Szöcsik, and Zuber Citation2015). However, analyzing SNP strategic behaviour in regional elections is relevant in stressing that salience forms part of their ‘strategic toolbox’ (Elias Citation2019, 4). Moreover, it points to internal and external constraints influencing regionalist parties’ strategies. The former relates to a party’s identity or ideological legacy and its organizational structures. External constraints include whether a party is in or out of government and the ‘issue structure’ of the political landscape including the impact of public opinion on territorial/ economic issues, strategic choices of other competing parties, and the implications of decentralization. It therefore helpfully outlines factors impacting upon the salience of secession demands in a specific regional elections context.

To develop a broader understanding of what affects the salience of pro-independence parties’ secessionist demands, this article modifies Elias and Mees’ framework (Citation2017) utilized to date to examine two forms of shifts in territorial goals, shifts in positioning between greater self-rule and secession (Convergencia i Unió in Catalonia) and shifts in the salience of a territorial goal (Basque Partido Nacionalista Vasco). It highlighted key intra-party and external factors contributing to these shifts. Intra-party factors are party ideology and internal power relations, with external factors encompassing the territorial state structure, party competition dynamics and multi-level politics, the impact of a financial crisis, public opinion on constitutional preferences and whether a party seeks to enter government. Overall, the framework enabled an analysis appreciating the particularities of the interaction between factors in different cases and periods owing to ideological, political and constitutional pressures (Elias and Mees Citation2017, 158). However, the framework is less specifically attuned to understanding shifts in salience.

This article develops the framework for understanding factors influencing shifts in the salience of a pro-independence party’s secession demands to be applied to understand these dynamics across a range of cases. In doing so, a key contribution is to highlight the multi-level influences and to strengthen attention to the impact of state-wide developments on the salience of pro-independence demands. Therefore, the article’s modified framework for understanding secessionist parties replicates the vast majority of Elias and Mees framework’s intra-party and external factors (see ).

Table 1. An expanded framework of key factors affecting the salience of pro-independence party territorial demands.

The internal factors examined are party ideology, internal power relations and whether or not a party seeks to enter government with respect to intentions and practice. Regarding external factors, first, state-level factors include the impact of the territorial organization of the state, with the impact of multi-level politics on secessionist goals relating to simultaneous involvement in sub-state and state-level party systems.

Two additional external state-wide factors included in the framework are the impact of incumbent parties at central government level and the territorial demands of secessionist parties elsewhere within the state. First, in incorporating the state-level governing party, we remove the impact of the financial crisis factor in Elias and Mees’ framework. The state-level governing party factor is posited as significant as the impact of scenarios such as a financial crisis on secessionist parties is ultimately determined by the effects of state-level governing party/ies’ underlying strategy and ideological positioning on their responses. Consequently, examining the effects of state-level governing parties is informed by Muro (Citation2015). Its attention to party ideological positioning (Muro Citation2015, 28) ‘the ideological corpus or ‘color’ that largely determines its preferences with regard to the degree of asymmetry between regions’ and the political strategy of the (central state) governing party. Second, the framework also incorporates the impact of pro-independence parties in another part of the state as an explanatory factor. A ‘demonstration effect’ whereby regionalist party electoral success in one region could impact another region is long acknowledged (De Winter Citation1998, 220; see also Massetti and Schakel Citation2016). Given its more specific attention to secessionist parties, this framework focuses on the impact of secessionist parties within the same state structure.

Sub-state level factors are associated with the opportunities and constraints arising from decentralized government. They include the implications of party competition from state-wide and other regionalist parties in sub-state elections and public opinion regarding constitutional preferences.

After outlining the framework, we map key expectations regarding the relative impact of different factors on the salience of a secessionist parties’ pro-independence calls. As regards internal factors, we expect party ideology to have a relatively significant impact given its underpinning influence on a party’s emphasis on its independence demands. Given the role played by ideology, the impact of internal power relations on territorial strategy decisions are expected to be more modest. Secessionist parties with ambitions or experience of government are anticipated to be more likely to stress more moderate territorial demands than to be strong independence advocates, with those leaning towards opposition status likely to foreground the latter.

Turning to external statewide factors, the impact of the territorial organization of the state on a party’s emphasis on secessionism is expected to be most apparent in the context of decentralized government. For instance, heightened territorial conflict with the state level is likely to increase a secessionist party’s calls for independence. The dynamics of multi-level politics is likely to be less influential in general, but its impact on the salience of independence demands most apparent if a party secures political leverage via strong performances in state-wide elections. The state-level governing party factor effect is likely to interplay with the territorial organization of the state factor. A lack of accommodation of centre-periphery demands is expected to contribute to pro-independence party assertiveness on secession with the governing party’s ideological positioning and strategy having a determining impact. State-wide parties may be unwilling to engage with centre-periphery issues (Massetti Citation2009, 513). Support for decentralization is likely to be greater amongst centre-left state-wide parties with centre-right state-wide parties more resistant, thus potentially fuelling the strength of secession demands. Another expectation is that a pro-independence party elsewhere within the same state can have a domino effect on another pro-independence party’s calls for secession.

Finally, the two sub-state level factors are expected to inter-relatedly impact on the salience of a party’s secessionist demands. This applies to party competition from state-wide and other regionalist parties in sub-state elections and public opinion regarding constitutional preferences. Both can influence the stress placed on pro-independence goals with the effects contingent on a sub-state party’s electoral performance and the degree of party competition from other regionalist (particularly secessionist) parties.

Methodology and case selection

This article evaluates the strengths of the modified framework building on Elias and Mees (Citation2017) to analyze the factors affecting the salience of independence amongst secessionist parties by examining Plaid Cymru (PC) 2003–2021. Overall, the focus is less on providing a rich empirical discussion and more on analyzing PC to test the analytical framework. Rather than focusing on high profile secessionist parties, particularly in Scotland and Catalonia, examining PC evaluates the framework in relation to a secessionist party least likely to be assertive on independence where there is a shift in the salience of its independence demands. Its ‘threatening intention’ (Massetti and Schakel Citation2016, 60), its secessionist ideological position, has been relatively modest and its ‘threatening capacity’ constrained owing to its limited electoral strength. Electorally, since the 1990s, PC’s vote share in state-wide elections has been around 10%. Its electoral high point was the first regional election in 1999 (28.4% on the constituency vote and 30.5% on the regional list votes) thus securing 17 out of 60 seats and main opposition party status. However, its vote subsequently stabilized at around 20% in regional elections, obtaining 15−20% in European elections. Its sole government experience was a junior coalition partner with Welsh Labour during 2007–11. However, as will be evident below, since 2019 we see a significant increase in PC’s emphasis on independence.

The article investigates PC’s territorial demands and the salience of independence based on qualitative content analysis of PC manifestoes in state-wide, sub-state and European elections in the FraTerr dataset (1990–2018) extended to party manifestoes to 2021. Manifestoes are excellent to analyze party strategic calculations regarding territorial demands. Twenty manifestoes were analyzed based on a coding scheme using computer assisted qualitative content analysis to analyze party territorial demands. The focus on the total number coded in each document allows for an analysis of salience, the extent of emphasizing or downplaying independence vis a vis other territorial demands. In addition to independence, the other main territorial demands were self-rule to transfer competences to the sub-state level, greater shared-rule to increase sub-state level influence at higher governance levels (e.g. state or EU), and a limited number of demands for reform leading to a federal political structure. They also include demands for action by higher levels of government, particularly calling central government to make policy decisions that do not require change in the existing constitutional/legal framework, for instance the allocation of resources, or recognition of an identity or interest of the territory (Elias et al. Citation2021, 7–8). In analyzing PC, we focus on 2003–2021, from PC’s commitment to Welsh independence.

The subsequent section then applies the modified framework to evaluate its ability to assess the factors influencing decisions on prioritizing different territorial demands and the salience of PC independence calls. It draws on party documentation, other primary sources, and interviews with eleven key informants in PC and other Welsh regionalist movements in 2020–21. Interviewees included leading individuals currently or previously serving as PC elected politicians, party officials and National Executive Committee members. In line with the project’s ethics approval, interviews were conducted based on anonymity, were recorded and transcribed.

Plaid Cymru’s territorial demands

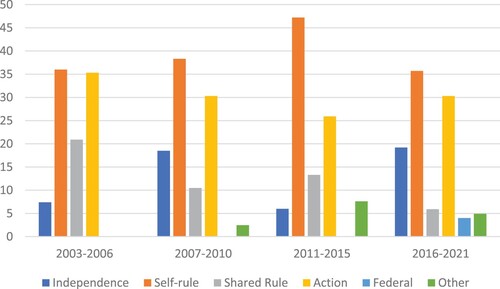

Regarding PC’s constitutional position, in 1932 it adopted as its principal objectives the preservation of the Welsh language and the cause of self-government. However, from 2003, its constitutional goal shifted from the ambiguously formulated ‘full national status’ to the more explicit ‘independence in Europe’ (Elias Citation2009a, 65–70). outlines PC’s territorial demands during 2003–2021 according to sub-state election cycles and highlights shifts in the salience of its independence demands. The party’s main constitutional demand in 2003, greater self-rule for Wales, continued as its main demand up to 2021, ranging between 36% and 47% of its territorial demands. In contrast, independence is downplayed and represents 7.4% of PC territorial demands in manifestoes during 2003–06 after it committed to independence. For instance, in 2003, given the priority of increasing self-rule, PC is keen to stress that ‘Legislative devolution should not be regarded as a mere staging post to full national status’ and outlines that its ‘aspiration is for our country to achieve the status of member state within the European Union’ (PC Citation2003, 47). Independence does not feature as PC’s main demand in any period during 2003–2021. The main emphases are presenting independence as an ‘ambition’, ‘long-term vision’ that would be subject to a referendum. Across the entire period, independence is the joint third most prominent territorial demand with shared rule.

Figure 1 . Share of territorial demands, Plaid Cymru, 2003–2021 (% of all territorial demands made).

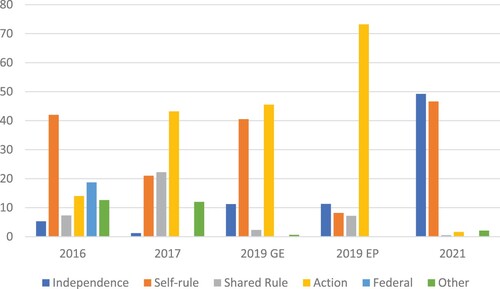

However, by 2016–2021, independence represents 19% of PC territorial demands. The stronger emphasis is further evidenced by independence accounting for 18.5% of PC’s constitutional claims in 2007–10 based on a frequency of 30 demands, compared to 19% of demands for independence in 2016–2021 based on a frequency of 134 demands. Given the increased salience of claims for independence post-2016, details PC’s territorial demands in each election 2016–2021. Overall, independence is the third most prominent territorial demand with government action as the main demand, reflecting concerns regarding the implications for Wales of UK EU withdrawal, followed by self-rule associated with disquiet regarding potential constitutional challenges to devolved government post-Brexit and continuing calls for further decentralization. 2019 marks a turning point in the salience of PC’s independence calls. It is the party’s main constitutional demand in 2021.

Figure 2 . Main configurations of Plaid Cymru territorial demands per election, 2016–2021 (% of all territorial demands made).

PC’s 2016 manifesto confirms independence as its ‘long-term aspiration’ and stipulates ‘we do not plan to hold a referendum in the near term’ (PC Citation2016, 185). Only once is an independent Wales mentioned in the 2017 manifesto. In the two 2019 manifestoes, though the shift in emphasis on independence is moderate (11% of demands in each), the tone and urgency changes with more concrete plans to achieve independence. The first sets the aim of holding an independence referendum by 2030 (PC Citation2019a, 54) and discusses the party’s Independence Commission (Citation2020), established to make recommendations on party preparations for independence. In calling for a second EU membership referendum, the second manifesto focuses on arguments for independence in relation to EU member state status (PC Citation2019b). Finally, in 2021, 49.2% of the party’s territorial demands were for independence and PC commits to holding an independence referendum during its first government term, working towards ‘A new, sustainable, equal and socially just independent nation’ (PC Citation2021a, 12). It sets out a vision for a Welsh state in 2030, steps to a referendum and the role of a statutory National Commission (PC Citation2021a, 115).

Therefore, analysis of manifestoes during 2003–2015 highlight the extent to which PC largely downplayed its ultimate constitutional aim and prioritized more immediate territorial goals, self-rule in particular. PC’s firmer and more assertive position on independence post-2019 signifies a clear shift.

Explaining the salience of Plaid Cymru’s pro-independence demands

Applying the modified framework, discussing each factor in turn, whilst also recognizing interrelationships between various factors, underlines its value in highlighting the main internal and external factors impacting on the salience of a pro-independence party’s territorial demands. Reflecting analysis of PC’s territorial demands above, we apply the framework to two periods, 2003–2015, when independence was downplayed, and post-2016 when the party’s commitment to independence grows in prominence, particularly 2019.

2003–2015

The main factors influencing PC’s decisions to downplay its ultimate goal of independence in this period are explained by the framework. The combined effects of constraints affecting the party within the decentralized state structure, the implications of sub-state party competition compounded by the moderating effect of public opinion on constitutional preferences, the influence of formative party ideology buttressed by internal power relations all encouraged PC to prioritize more moderate constitutional goals, with being an office seeking party having a more limited effect. The ideological positioning and strategic intentions of state level governing parties are also highly important in explaining territorial accommodation in this period with the multi-level politics element of party competition a limited impact given the party’s restricted Westminster presence.

Firstly, examining the impact of internal factors, despite its recent explicit commitment to independence in 2003, party ideology, specifically formative philosophical reasons, is significant to understanding PC’s almost consistent foregrounding of self-rule demands and limited attention to independence. PC’s first leader, Saunders Lewis, emphasized ‘freedom’ that was ambiguous in political constitutional terms and opposed identifying self-government and independence as party aims (Wyn Jones Citation2007). This deeply influenced PC’s reticence on ‘independence’. Its leader’s denial in the context of the 1999 election that it had ‘never, ever’ sought ‘independence’ (McAllister Citation2001, 215) reflects the continuation of this longstanding struggle in this period.

Whilst its effect is less significant overall, the internal power relations factor reaffirmed the party ideology factor by contributing to the party’s limited attention to independence during 2003–2015. Some interviewees argued that the ‘independence question was ambiguous within Plaid Cymru’ and that it had ‘always been gradualist … of the belief in moving onwards step by step and very pragmatic in the sense of building on what we had through more powers’Footnote1. This reflected the party’s two main schools of thought during 2003–2015. The more influential ‘nation-builders’ emphasized advancing self-rule and a gradualist pathway to independence, particularly within PC’s electoral competition environment, the other school being advocates of a greater emphasis on independence. The attention to independence featured in internal debates with some criticisms of party leaders for not being clearer on the Welsh independence aim (Wyn Jones and Scully Citation2004, 205; Elias Citation2009b, 128). Relatedly, interviews pointed to the impact of generational effects on PC leaders and their political strategy. They associated leadership reticence on independence with their unsuccessful 1979 Welsh Devolution Referendum experience that profoundly damaged the party’s credibility: ‘the ‘79 experience was significant and affected a number of Plaid Cymru leaders. Therefore, a step-by-step approach was important’.Footnote2 A key side effect was heightening PC’s sensitivity to aligning with public opinion (discussed below).Footnote3 Moreover, the implications of whether or not a regionalist party seeks to be in government also contributed to PC stressing moderate constitutional demands. PC’s objective was realizing its policy agenda and forming a regional government. Its opportunity arose in 2007–11 as a minor coalition partner with Welsh Labour. Three main self-rule demands included in the coalition agreement were all realized and the affirmative 2011 referendum on law-making powers marked a significant step. The decline in PC’s electoral support in the subsequent election suggest that prioritizing policy-seeking weakened its electoral success (McAngus Citation2014).

Secondly, turning to external factors, in terms of state-wide factors, the territorial structure of the state from 1999 onwards encouraged PC’s emphasis on moderate, greater self-rule calls and limited promotion of independence. Whilst asymmetric devolution in the UK created new opportunity structures, inherent weaknesses to Wales’ constitutional arrangements were compounded by limited support for devolution in the 1997 Welsh referendum.Footnote4 This territorial context steered PC to prioritize greater self-rule to address the constitutional challenges and to strengthen the legitimacy of Welsh devolved government, thus contributing to incremental self-rule expansion over 20 years (see Torrance Citation2018). One interviewee explained: ‘the priority was to move the Assembly along and we had to make the Assembly into a Parliament’.Footnote5

The framework’s two additional state-wide dimensions are also central to explaining PC’s prioritization of self-rule. Firstly, incremental Welsh self-rule gains internally affirmed PC prioritizing this goal and were contingent upon UK governing parties granting further self-rule to Wales via UK Parliament legislation. During 1999–2015, UK Labour and a Conservative Party and Liberal Democrats coalition (1999–2010 and 2010–2015 respectively) largely accepted UK devolved government arrangements and, with some reluctance, granted further self-rule. Between 1999 and 2010, UK Labour’s low enthusiasm for enhancing devolution reflected persisting internal division on the centre-periphery cleavage. However, advancements such as the Government of Wales Act 2006 were enacted as Welsh Labour support for greater self-rule increased, facilitated by key individuals in UK Labour’s Westminster government. Under such circumstances, Labour ‘were in power in Westminster. They were able to achieve legislative devolution’.Footnote6 Unexpectedly, the Cameron-led Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government’s ‘respect’ agenda towards UK devolved governments is considered a ‘clear departure’ from earlier Conservative and Labour attitudes (Convery Citation2016, 29). Whereas electoral arithmetic and its coalition partner partly explain this positioning, ideologically, Cameron’s government granted further self-rule contingent on it not affecting ‘the central assumptions of the Westminster model of British Government’ (Convery Citation2016, 21). Strategically, territorial accommodation across the UK sought to contain Scottish independence. For PC, this meant the ‘pattern of putting pressure on the Westminster Government to transfers power also happened under the Conservative party. We were also as a party able to take some advantage of the Scottish referendum to call for these transfers, alongside Welsh Government calls … . there was an open door to nation-building and devolving powers one by one’.Footnote7

The second additional state-wide factor, secessionist parties in another part of the state, reflects historically close relations between the two ‘sister’ parties, SNP and PC. In this period, the SNP’s unequivocal position on independence was a continual backdrop, but arguably a more long-term influence: ‘the SNP’s unambiguous position on independence over time forced Plaid to be unambiguous’.Footnote8 Both were main opposition parties between 1999 and 2007 and both entered government in 2007, albeit with the SNP as the governing party and PC as a junior coalition partner.

Turning to sub-state level factors, within the framework of devolved governance, state-wide party competition directly contributed to PC’s emphasis on more moderate constitutional goals, with Welsh Labour its main challenge and no other electorally credible regionalist parties. Despite dramatically greater levels of support for PC in the first Assembly election, Labour’s strong performance in sub-state elections reflects historical one-party domination (Awan-Scully Citation2013). Moreover, state-wide parties, especially Labour, adopted a ‘convergence strategy’ (Massetti and Schakel Citation2016, 62), taking on the regionalist agenda. In moving ‘to an address previously occupied by Plaid’ (Wyn Jones and Scully Citation2003, 129), Labour’s journey in this period was one of initially restrained and incremental support for greater Welsh self-rule (Bradbury Citation2006, 227). Significantly for this article, a key consequence of Labour’s continuing centrality is its ‘contagion effect’ (Hepburn Citation2014) influencing other parties’ self-governance positions. Indeed, reflecting this, one debate within PC in this period was whether it was necessary for PC to become Wales’ main political party to achieve its self-governance goals, or whether it should focus on creating the conditions for other parties, Labour particularly, to realize these constitutional aims (see for instance Williams Citation2003, 41).Footnote9 This debate reflects the extent that Welsh Labour competition in sub-state elections influenced PC’s more gradualist self-governance approach at this point. Overall, party competition significantly affected the low prominence of PC’s independence goal in this period.

The other sub-state level factor, public opinion on constitutional preferences interrelate with sub-state electoral competition to explain PC’s prioritization of self-rule demands. Reflecting discussion of public opinion effects on the party internally and party competition dynamics, as PC sought to gain wider electoral support, it emphasized calling for self-rule to align with public opinion. This shifted from low public endorsement of devolution in 1997 to significant public support for extending devolved autonomy, with limited support for independence ongoing (Scully and Wyn Jones Citation2015). Emphasizing its ultimate constitutional goal was internally perceived as risky and counter-productive electorally, with concerns that ‘over-emphasizing independence would raise fears amongst some of Plaid Cymru’s traditional and potential supporters’.Footnote10 Consequently, ‘securing broader support for developing self-government to Wales and focusing on that aim rather than making independence the defining matter for Plaid Cymru’ was prioritized.Footnote11 Its decision to distance itself from being explicit in supporting Welsh independence, including when pressured to clarify the party’s constitutional position, is considered to have contributed to Plaid Cymru’s electoral success in the 1999 election, alongside the electoral repercussions for Labour of finding adapting to multi-level electoral politics challenging and related internal struggles (Bradbury Citation2006, 240–241; Elias, Citation2009b, 122). PC subsequently continued to prioritize further self-rule calls as polls confirmed increasing support for greater self-rule.

Post-2016

In addition to explaining the factors affecting PC’s stress on more moderate constitutional demands and low salience of independence during 2003–2015, the framework’s key internal and external factors also highlight shifts leading to the increased salience of PC calls for independence during 2016–2021. Brexit as a transformation in state structures with negative reprecussions for decentralization was important, highlights the significance of the incumbent state-level governing party factor, and has a substantial impact on other factors that push the party to being assertively pro-independence post-2019.

Turning first to external factors, changes to state territorial structures owing to the 2016 referendum and the approach to devolved governments during the UK’s EU withdrawal acutely impacted on PC. Its Brexit response was more complex than the SNP given the affirmative vote in Wales (52.5% in favour and 47.5% against), a ‘traumatic’ result with the party in shock.Footnote12 After struggling with messaging, PC reaffirmed its ‘independent Wales in Europe’ commitment (Party of Wales Citation2016) and campaigned for a second EU referendum. Little reference to independence in 2016 and 2017 illustrate PC’s initial difficulty in engaging with its ultimate goal post-referendum. However, Brexit precipitated a changed approach by the UK Government to devolved governance, leading to constitutional change viewed as reversing devolution. Over time, the perceived unprecedented threats to devolved government led to PC resolving that investing in nation-building efforts requiring Westminster approval were of no value. Consequently, support for prioritizing and making the case for independence increased. From 2019, PC argued that as ‘Westminster does not work for Wales’ (PC Citation2019a, 5) with devolved government unable to defend itself from Westminster ‘attacks’. Independence was the only answer to defend Welsh democracy (PC Citation2020).

The framework’s additional state-wide factors enable a more comprehensive explanation of this shift. First, regarding the incumbent party at central government, in contrast to territorial accommodation in 2003–2015, decentralization tensions arose following the 2015 election of a Conservative government, eventually leading to PC warning of a ‘power grab from Westminster’ (PC Citation2017, 14).Footnote13 Ideologically, Conservative unionist re-affirmation of parliamentary sovereignty under Johnson by asserting a unitary vision of Westminster’s parliamentary sovereignty as central to the UK constitution alongside an ‘Anglo-British nationalist narrative’ (Wincott, Davies, and Wager Citation2020, 9) was apparent in the Brexit context. They explain why Brexit UK-EU negotiations were treated as the UK Government’s exclusive responsibility (McEwen Citation2020) and why EU regional policy replacement arrangements, the Internal Market Act and Shared Prosperity Fund, were deemed ‘a clear attempt by the UKG [UK Government] to claim areas of competence the DGs [Devolved Governments] regard as their own’. (Wincott, Davies, and Wager Citation2020, 3). These developments have been explicitly associated with the marked change on devolution between Cameron and Johnson’s version of conservatism, apparent also in May’s commitment to the UK union (Wincott, Davies, and Wager Citation2020). The ‘muscular unionism’ dimension of Conservative political strategy was supported by its strong majority following the 2019 state-wide election that constrained Westminster opposition and led to UK devolved voices being given limited attention. Johnson’s efforts to create a more unified UK-wide approach in response to COVID-19 clashed with devolved UK governments (Morphet Citation2021). Conservative ideological positioning shifted PC to greater decisiveness on Welsh independence: ‘We’ve had to shift our priorities due to the political circumstances … The door is shut. There is nothing on the horizon in terms of nation-building through further powers. Consequently, why not have a broader discussion, try to sell the idea of independence’.Footnote14

Second, the impact of secessionist parties elsewhere in the state on Plaid’s more strongly secessionist position highlights the implications of the SNP. Despite the 2014 Scottish independence referendum result (55% against and 45% in favour), an interviewee described the referendum as a ‘game-changer’. Despite not instantly impacting on the salience of PC’s independence demands, it profoundly impacted on PC’s eventual emphasis on independence apparent from 2019 onwards.Footnote15 First, in firmly placing the UK’s constitutional future on the political agenda, it contributed to normalizing independence demands across the UK. It also fuelled generational change in independence support, including amongst young people in Wales. Third, the pro-independence Scottish Parliament majority, SNP continuing strength at Westminster, and support for another Scottish independence referendum post-2019 necessitated the repercussions for Wales to be on the agenda across the political spectrum. Similarly, tensions regarding Northern Ireland exacerbated the sense of political turmoil within the UK. Indeed, PC contextualized its independence proposals as ‘a crisis of the British State in relation to Northern Ireland and Scotland, which the 2016 Brexit referendum and the 2019 general election underlined’. (Independence Commission Citation2020, 11).

Though Scotland (and Northern Ireland in part) provided critical context to the increased salience of independence demands, the former’s role was somewhat less significant in the latest period. Learning from Scotland was still ongoing, including the Independence Commission engaging with SNP counterparts in developing its 2020 report. However, there were indications of less sharing between the parties on self-governance given their different circumstances and relations between the Welsh Labour and SNP governments ‘the impression is that they engage very closely, particularly given Brexit and COVID’.Footnote16 Moreover, PC’s greater urgency in achieving Welsh independence as a result of UK Conservative governance prompted focusing on Wales’ case for independence, as opposed to being overly concerned with reacting to external developments supporting independence.

Amongst the heightened constitutional uncertainties, other sub-state level external factors contributed to PC’s stronger independence position, particularly changes in public opinion. The repercussions of Brexit for public opinion on constitutional preferences greatly encouraged PC to emphasize Welsh independence as various surveys indicated greater support for independence. Some polls suggested a doubling in support between 2019 and 2021 (to 14%), others that 39% of Wales’ population supported independence, particularly younger age groups and higher than expected amongst Labour voters.Footnote17 PC referred extensively to these trends, arguing that independence was for instance experiencing ‘something of a breakthrough, to a point that it must now be regarded as mainstream and more than a marginal prospect’ (Independence Commission Citation2020, 46) and had become a decisive election issue in Wales (Hiraeth Citation2021). Public support for independence also relates to Yes Cymru. Established as a non-partisan movement to make the case for an independent Wales, it experienced substantial membership increases amidst post-Brexit political dissatisfaction. Together, these trends spurred PC to give greater prominence to its independence calls. As one interviewee explained, ‘the success of Yes Cymru has influenced Plaid Cymru, undoubtedly, to be more prominent in its commitment to independence’.Footnote18 Another stated, ‘if we cannot present ourselves as that political wing, taking advantage of the fact that something is happening in terms of the popularity of that grassroots movement, we wouldn’t really be doing our job’.Footnote19

Regarding the implications of sub-state level party competition, post-2016, PC’s electoral performance largely plateaued with Welsh Labour continuing its dominance (Awan-Scully Citation2021). As discussed above for 2003–2015 and indeed up to 2019, electoral competition encouraged PC to prioritize more immediate territorial demands to bolster its electoral prospects. However, the impact of Brexit and shifts in public opinion contributed to steering PC’s greater assertiveness on independence with Welsh Labour positioning also having some effect. From a gradualist and moderate position, aligned with Welsh public support for greater self-rule, by 2019 Welsh Labour had shifted to a devolution max position. It proposed a pro-unionist vision to reform relations within the UK on more federal lines (Welsh Government Citation2021). As regards the extent of convergence, similarities with PC included Welsh Labour’s stress on the ‘serious threat’ to devolution from the Conservative UK Government and willingness to fight for ‘radical constitutional change’ (Welsh Labour Citation2021, 64). Whilst many interviewees attributed PC’s influence to this positioning, it was a major challenge for the party. PC’s leader, Adam Price, referred to the difficulty of recovering from Labour’s rebrand and the ongoing re-positioning challenge facing the party (Eirug Citation2022, 26). A PC interviewee noted that ‘Welsh Labour are trying to face in every direction on the independence question. That is, they obviously know it’s advantageous for them to be placing their tanks on our lawns in order to appear to be somewhat nationalistic and trying to steal our supporters’.Footnote20 In light of public opinion trends post-Brexit, Welsh Labour’s latest positioning made some contribution to PC greater firmness on independence.

Finally, in the context of external factors outlined above, internal PC power relations shifts are critical to the increased salience of independence. Generational change in leadership had already occurred with Leanne Wood becoming party leader (2012–2018), followed by Adam Price (2018 to June 2023). Independence was an important topic in both leadership races, signaling party shifts to greater confidence and extroversion in independence support. Whereas some interviewees attributed the change in PC’s prominence on independence entirely to external factors, others suggested a difference in emphasis on independence between Wood and Price, though no substantial ideological difference between them.Footnote21 For instance, one interviewee argued that ‘it was a part of Leanne’s initial pitch, but it wasn’t foregrounded on every possible opportunity during her leadership period. I think that there are legitimate reasons for that’.Footnote22 Interviewees explained that with PC’s commitment to the constitutional aim of independence now well supported and unquestioning, the party’s two main schools of thought had shifted from the previous categories of ‘nation-builders’ and ‘independentists’ to ‘incrementalists’ and ‘fundamentalists’. Wood was more associated with the incrementalists, that reflected on the SNP gradualist experience since 2007, arguing for prioritizing getting to ‘first base’: securing sufficient electoral support to be seen as a credible government, to make the case for independence in government.Footnote23 In contrast, Price was more associated with the ‘fundamentalists’. Having stressed the importance of foregrounding independence in the 2018 leadership campaign, ‘rather than treading carefully around the subject, he wanted to get it out there … placing an emphasis on independence as the party’s main objective and elevating that aim’.Footnote24 Our data illustrates that this was put into practice on becoming leader. Plaid sought to be more assertive, normalize discussion of independence, illustrating a strategy shift from being responsive to seeking to proactively shape voter constitutional preferences: ‘the seeds have now been sown. We’re now associated as the party who leads on independence in Wales and that hasn’t always been the case’.Footnote25

Regarding the office-seeking party factor, contrary to the framework’s expectation, PC’s government ambitions did not deter foregrounding independence. Instead, in the 2021 election, its strategy shifted to combine office-seeking goals with its urgency to progress on realizing independence. It aimed to achieve a governing majority with its leader as First Minister, was unwilling to be a junior coalition government partner, and committed to an independence referendum in its first government term. Analyses suggest that PC’s unambiguous independence position was not detrimental to its 2021 electoral performance (Wyn Jones Citation2021, 12). The 2021 election result left Welsh Labour one short of an absolute majority leading to a three-year Co-operation Agreement with PC in November 2021. It included the establishment of an Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales to consider options for governing Wales while continuing as an integral part of the UK and options including ‘Wales having full control to govern itself and be independent from the UK’ (Welsh Government Citation2022). Consequently, PC’s status a ‘co-opposition’ party and less clearcut form of ‘office-seeking’ was portrayed as a nation-building programme for government, a ‘down-payment’ on independence (PC Citation2021b).

Discussion and Conclusion

This article set out to contribute to the literature on regionalist parties in Western Europe by developing a framework to better understand secessionist party strategy regarding the salience of their pro-independence demands. In doing so, it sought to investigate the factors behind the tendency amongst pro-independence parties to vary their emphasis on their ultimate constitutional aim, independence, with cases and periods of prioritizing more modest constitutional goals and others of more assertively foregrounding their independence goal. Consequently, this article modified Elias and Mees’ framework (Citation2017) to assess factors influencing the salience of pro-independence demands amongst secessionist parties by replicating key internal and external factors and, given the potential impact of state-wide factors and importance of developing a more multi-level analysis, it incorporated two external state-wide factors, the impact of governing parties at central government level and secessionist parties in other parts of the state.

PC was a particularly valuable case as its post-2003 commitment to independence was predominantly played down prior to a significant shift in assertiveness on independence from 2019. Applying the framework to investigate PC confirmed its explanatory potential to comprehensively analyze the internal and external factors influencing a secessionist party’s strategy regarding its territorial demands and upheld the significance of the framework’s additional state-wide factors. Given the trends in PC, applying the framework demonstrated its capacity to explain downplaying independence in the party’s strategic calculations during 2003–2015 to prioritize vote-seeking goals within the context of the external factors it faced, and to also explain shifts to foreground secession in contrasting circumstances, particularly post-2019.

Returning to the expectations and firstly to internal factors, the case study confirmed the strong impact of party ideology, particularly its formative underpinnings, in influencing the low salience of independence demands during 2003–2015. Whereas the effects of internal power relations were as expected more modest, they played a reinforcing role alongside PC’s office-seeking ambitions in downplaying independence in that period. However, contrary to the expectations of modest impact, internal power relations, particularly party leader agency, was highly significant in spurring party shifts in territorial strategy decisions in the dramatically changed context post-2016. It was also important in explaining PC’s unexpected strategy of combining office-seeking and foregrounding independence in the 2021 sub-state election, at variance with expecting being office-seeking to lead to downplaying independence.

In terms of external state-wide factors, as expected, the territorial structure of the state had a substantial influence. The effects of decentralization during 2003–2015 constrained the salience of independence as it interplayed with the state-level governing party factor in a context of territorial accommodation by state-wide parties on the centre-left and centre-right. However, alternative state developments post-2016, particularly developments in recentralization, displayed an ideological shift in positioning by the centre-right governing party towards devolved governance. Together, they proved powerful in shifting the basis for PC’s decision to foreground independence. The analysis demonstrated that the secessionist party in another part of the state factor can interplay with other factors. As expected, it can have a domino effect but its impact can be less immediate than other factors. The analysis also demonstrated that it can be more intense in the context of proactive efforts to secure independence (e.g. a referendum), and have a less direct impact once a party shifts its position on the urgency of achieving independence. Of the state-wide external factors, the multi-level dimension of party competition was as expected less influential, in PC’s case owing to its limited electoral impact at the state level.

At the sub-state level, as expected, the implications of sub-state party competition and the impact of public opinion on constitutional preferences on party strategic electoral calculations were key interrelated external drivers. Our analysis highlighted their potential to influence secessionist parties to moderate their pro-independence calls (2003–2015) and for further progression of party convergence strategies and signs of change in public support for independence to be an impetus to be upfront on secession. Whereas the public opinion dimension is generally likely to be the most significant of the two given its implications for vote-seeking goals, the party competition factor was powerful in the Welsh case of single party dominance of electoral politics and its repercussions for a pro-independence party.

Overall, the article posits the strengths of the framework of internal and external factors at state-wide and sub-state levels to understand the salience of a pro-independence party’s secession demands. These key factors combine and interplay at multiple levels in specific ways in different cases at particular periods, influenced by specific ideological, political and constitutional dynamics. Incorporating the incumbent party at central government factor into the framework heightens attention to the deep-seated ideological basis of central state governing parties’ constitutional interpretations and consequent implications for a pro-independence party. Moreover, the secessionist demands of a pro-independence party are also important given the potential to affect another secessionist party elsewhere within the state on the salience of their calls for independence. However, this factor may possibly have limited broader applicability as other regionalist parties, including other secessionist parties, forming part of sub-state party competition may have similar effects in other cases.

Consequently, further research could assess the modified framework’s broader potential to explain the salience of pro-independence parties’ secessionist demands. State-wide factors may be more relevant in some multi-level state contexts than others, dependent on issues such as the form of decentralization, with asymmetric decentralization and lack of constitutional entrenchment in regionalized states potentially resulting in greater fluidity in state structures and scope for state-wide factors to impact. Consequently, the framework could be further evaluated by investigating pro-independence parties in cases such as Catalonia, Sardinia and Galicia. Such investigations would further reveal its explanatory potential regarding the political strategic calculations of secessionist parties and contribute to better understanding the significance of European-wide shifts in independence demands.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.8 KB)Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the feedback received on drafts of the paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions May 2021 and ‘Crises of Territorial Politics’ panel at the UACES Conference, September 2021, particularly from Dr Anwen Elias. She is also wishes to thank the anonymous reviewers for their feedback.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interview 4, 26.11.2020

2 Interview 2, 18.11.2020.

3 Interview 2, 18.11.2020.

4 1997 Welsh Devolution Referendum result: yes vote 50.3 per cent, 49.7 per cent no vote.

5 Interview 6, 4.12.2020.

6 Interview 10, 22.10.2021.

7 Interview 10, 22.10.2021.

8 Interview 4, 26.11.2020.

9 Interview 2, 18.11.2020, Interview 6, 4.12.2020.

10 Interview 4, 26.11.2020.

11 Interview 4, 26.11.2020.

12 Interview 2, 18.11.2020, Interview 4, 26.11.2020.

13 See concerns regarding the UK Government Draft Wales Bill published in September 2015. Some of the issues were addressed in the 2017 Wales Act. However, concerns regarding the complexities of the legislation continued and it heightened issues of trust between the Welsh and UK governments.

14 Interview 10, 22.10.2021.

15 Interview 2, 18.11.2020, Interview 10, 22.10.2021.

16 Interview 9, 11.10.2021.

17 The ICM-BBC Wales St. David’s Day Polls reported the ten percent increase in support for independence between 2019 and 2021. The 39% figure was based on a Savanta ComRes Poll in February 2021 and don’t know answers were excluded.

18 Interview 10, 22.10.2021.

19 Interview 11, 1.11.2021.

20 Interview 11, 1.11.2021.

21 Interview 9, 11.10.2021.

22 Interview 11; 1.11.2021.

23 BBC Walescast Citation2021.

24 Interview 9, 11.10.2021.

25 Interview 9, 11.10.2021.

References

- Awan-Scully, Roger. 2013. “The History of One-Party Dominance in Wales. Part 3 1999–2011: Hegemony Under Challenge?” Elections in Wales Blog. Accessed November 29 2021. https://blogs.cardiff.ac.uk/electionsinwales/the-history-of-one-party-dominance-in-wales-part-3-1999-2011-hegemony-under-challenge/.

- Awan-Scully, Roger. 2021. “Unprecedented Times, a Very Precedented Result: The 2021 Senedd Election.” The Political Quarterly 92 (3): 469–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13045

- BBC Walescast. 2021. When we met Leanne Wood in the Rhondda, episode 17.8.21. Accessed September 19 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p09sgx2 m.

- Béland, Daniel, and André Lecours. 2021. “Nationalism and the Politics of Austerity: Comparing Catalonia, Scotland and Québec.” National Identities 23 (1): 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2019.1660312

- Bradbury, Jonathan. 2006. “British Political Parties and Devolution: Adapting to Multi-Level Politics in Scotland and Wales.” In Devolution and Electoral Politics, edited by D. Hough, and C. Jeffrey, 214–247. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Convery, Alan. 2016. The Territorial Conservative Party Devolution and Party Change in Scotland and Wales. Manchester: MUP.

- De Winter, Lieven. 1998. “Conclusion.” In Regionalist Parties in Western Europe, edited by L. De Winter, and H. Tursan, 204–247. London: Routledge.

- Dowling, A. 2018. The Rise of Catalan Independence. London: Routledge.

- Duerr, Glen M E. 2015. Secessionism and the European Union. London: Lexington.

- Eirug, Aled. 2022. “The Sullivan Dialogues.” In The Impact of Welsh Devolution: Social Democracy with a Welsh Stripe?, edited by J. Williams, and A. Eirug, 1–34. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Elias, Anwen. 2009a. Minority Nationalist Parties and European Integration. London: Routledge/UACES.

- Elias, Anwen. 2009b. “Plaid Cymru and the Challenges of Adapting to Post-Devolution Wales.” Contemporary Wales 22: 113–140.

- Elias, Anwen. 2019. “Making the Case for Independence: The Scottish National Party’s Electoral Strategy in Post-Devolution Scotland.” Regional & Federal Studies 29 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1485017

- Elias, Anwen, Linda Basile, Núria Franco-Gullién, and Edina Szöcsik. 2021. “The Framing Territorial Demands (FraTerr) Dataset: A Novel Approach to Conceptualizing and Measuring Regionalist Actors’ Territorial Strategies.” Regional & Federal Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2021.1964481.

- Elias, Anwen, Núria Franco-Guillén, Linda Basile, and Edina Szöcsik. 2020. “Deliverable 7.2: Summary Report on Comparative Framing of Regionalist Movements’ Political Claims.” Integrated Mechanisms for Addressing Spatial Justice and Territorial Inequalities in Europe (IMAJINE). Accessed February 4 2021 http://imajine-project.eu/result/project-reports/.

- Elias, Anwen, and Ludger Mees. 2017. “Between Accommodation and Secession: Explaining the Shifting Territorial Goals of Nationalist Parties in the Basque Country and Catalonia.” Revista d’estudis autonòmics i federals 25: 129–165.

- Elias, Anwen, Edina Szöcsik, and Christina Zuber. 2015. “Position, Selective Emphasis and Framing: How Parties Deal with a Second Dimension in Party Competition.” Party Politics 21 (6): 839–850. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815597572

- Hepburn, Eve. 2009. “Introduction: Re-Conceptualizing Sub-State Mobilization.” Regional and Federal Studies 19 (4-5): 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560903310204

- Hepburn, Eve. 2014. “Party Behaviour in Scotland”. Paper Presented at the Annual Elections, Public Opinion and Parties (EPOP) Conference, Edinburgh.

- Hiraeth. 2021. “The Adam Price Interview”. Accessed November 29 2021 https://soundcloud.com/hiraethpod/the-adam-price-interview.

- Independence Commission. 2020. Towards and Independent Wales: Report of the Independence Commission. Talybont: y Lolfa.

- Massetti, Emanuele. 2009. “Explaining Regionalist Party Positioning in a Multi-Dimensional Ideological Space: A Framework for Analysis.” Regional and Federal Studies 19 (4-5): 501–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560903310246

- Massetti, Emanuele, and Arjan H Schakel. 2015. “From Class to Region: How Regionalist Parties Link (and Subsume) Left-Right Into Centre-Periphery Politics.” Party Politics 21 (6): 866–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815597577

- Massetti, Emanuele, and Arjan H Schakel. 2016. “Between Autonomy and Secession: Decentralization and Regionalist Party Ideological Radicalism.” Party Politics 22 (1): 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068813511380

- Massetti, Emanuele, and Arjan H Schakel. 2021. “From Staunch Supporters to Critical Observers: Explaining the Turn Towards Euroscepticism among Regionalist Parties.” European Union Politics. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165211001508.

- McAllister, Laura. 2001. Plaid Cymru: The Emergence of a Political Party. Bridgend: Seren Books.

- McAngus, Craig. 2014. “Office and Policy at the Expense of Votes: Plaid Cymru and the One Wales Government.” Regional and Federal Studies 24 (2): 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2013.859579

- McEwen, Nicola. 2020. “Negotiating Brexit: Power Dynamics in British Intergovernmental Relations.” Regional Studies 55 (9): 1538–1549. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1735000

- McHarg, Aleen, Tom Mullen, Alan Page, and Neil Walker. 2016. The Scottish Independence Referendum. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morphet, Janice. 2021. The Impact of Covid-19 on Devolution. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Muro, Diego. 2015. “When Do Countries Recentralize? Ideology and Party Politics in the Age of Austerity.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 21 (1): 24–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2015.1003485

- Party of Wales. 2016. Motion to Reaffirm Party’s Commitment to an Independent Wales in Europe Passed by Hundreds of Members in Carmarthen. Accessed January 21 2021. http://web.archive.org/web/20200112113135/https://www.partyof.wales/cynnig_cynhadledd_arbennig_special_conference_motion.

- Plaid Cymru. 2003. Manifesto 2003. Cardiff: Plaid Cymru.

- Plaid Cymru. 2016. The Change Wales Needs. Cardiff: Plaid Cymru.

- Plaid Cymru. 2017. Defending Wales. Action Plan 2017. Cardiff: Plaid Cymru.

- Plaid Cymru. 2019a. Plaid Cymru General Election Manifesto 2019. Cardiff: Plaid Cymru.

- Plaid Cymru. 2019b. European Election Manifesto 2019. Cardiff: Plaid Cymru.

- Plaid Cymru. 2020. Independence “Only Solution” to Stop Westminster Power Grabs for Good Says Plaid Leader Adam Price, 9 September 2020. Accessed November 29 2021. https://www.partyof.wales/independence_only_solution_to_stop_westminster_power_grabs.

- Plaid Cymru. 2021a. Let Us Face the Future Together. Vote for Wales. Senedd Election Manifesto 2021. Cardiff: Plaid Cymru.

- Plaid Cymru. 2021b. Adam Price: “Nation building” Co-operation Agreement is a “down-payment on independence” 25 November 2021. Accessed November 29 2021 https://www.partyof.wales/adam_price_conference_speech.

- Scully, Roger, and Richard Wyn Jones. 2015. “The Public Legitimacy of the National Assembly for Wales.” Journal of Legislative Studies 21 (4): 515–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2015.1059591

- Torrance, David. 2018. A Process, not an Event: Devolution in Wales, 1998-2018. House of Commons Library Briefing Paper Number 08318. Accessed March 2 2020 https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-8318.

- Welsh Government. 2021. Reforming Our Union: Shared Governance in the UK June 2021. Accessed September 1 2021 https://gov.wales/reforming-our-union-shared-governance-in-the-uk-2nd-edition.

- Welsh Government. 2022. Have your say on the Constitutional Future of Wales. Accessed September 19 2022 https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/pdf-versions/2022/8/5/1661533119/have-your-say-the-constitutional-future-of-wales.pdf.

- Welsh Labour. 2021. Moving Wales Forward: Welsh Labour Manifesto 2021. Cardiff: Welsh Labour.

- Williams, P. 2003. The Psychology of Distance. The Gregynog Papers Volume Three, Number Three. Cardiff: Welsh Academic Press.

- Wincott, Daniel, Gregory Davies, and Alan Wager. 2020. “Crisis, What Crisis? Conceptualizing Crisis, UK Pluri-Constitutionalism and Brexit Politics.” Regional Studies 55 (9): 1528–1537. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1805423

- Wyn Jones, Richard. 2007. Rhoi Cymru’n Gyntaf: Syniadaeth Plaid Cymru. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Wyn Jones, Richard. 2021. “Rhoi Trefn ar Blaid Cymru.” Barn, Mehefin 2021, 11–14.

- Wyn Jones, Richard, and Roger Scully. 2003. “”Coming Home to Labour”? The 2003 Welsh Assembly Election.” Regional and Federal Studies 13 (3): 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560308559438

- Wyn Jones, Richard, and Roger Scully. 2004. “Minor Tremor but Several Casualties: The 2003 Welsh Election.” British Elections and Parties Review 14 (1): 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/1368988042000258835