ABSTRACT

Higher education has existed in Australia for 170 years, yet Indigenous Australians have participated for only half a century. One key change the Australian higher education sector has witnessed over the last decade is the steady increase of people occupying senior Indigenous leadership roles. These positions are indeed relatively new and have not been empirically investigated until now. Reporting on findings from an Australian Research Council funded study on Indigenous leadership in higher education, this paper highlights some of the discrepancies in how the skills of Indigenous leaders are interpreted by the academy, with a hope to challenge the sector’s next senior non-identified appointments to ensure that Indigenous people become integral architects in designing the future Australian higher education sector.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Higher Education in Australia is quite young compared with that of other first world countries and even younger if compared with the thousands of years Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples) have been educating subsequent generations in the daily necessities of life such as food gathering and survival but also in the sophisticated social, spiritual and moral lore governing our societies (Perry & Holt, Citation2018). The first university established in Australia was the University of Sydney, a sandstone institution founded in 1850 (Horne & Sherington, Citation2010). This was followed by several other institutions soon opening their doors – Melbourne University in 1853; University of Adelaide in 1874; University of Tasmania in 1890; University of Queensland in 1909 and University of Western Australia in 1911 (Partridge, Citation1965). By 1911, all six states had a university, however, in comparison with today, and the numbers of students studying were quite low with only 3,000 students enrolled nation-wide. Interestingly, two-thirds of this group were enrolled in Sydney or Melbourne University (Forsyth, Citation2014).

Ma Rhea and Russell (Citation2012) purport that institutions were established as ‘intellectual constructs of the British homelands’ (18). Others such as Forsyth (Citation2014) contend that unlike many of the internationally renowned institutions, Australian universities were usually designed by people who had minimal, if any, knowledge about the higher education sector. Forsyth (Citation2014) points out that this proved to be of benefit to the Australian higher education architects as it helped them to innovate. While both Sydney and Melbourne Universities were established to be more open and equitable than their British counterparts, in practice, few in the new colonies had the pre-requisite knowledge to begin university study (North, Citation2016) and education of Indigenous Australians was yet to figure in colonial consideration, as practices of segregation gathered pace as the colony expanded (Welch, Citation1988). Western education of Indigenous children began as an assimilationist intention to draw the increasing numbers of mixed race children into the broader society (Povey & Trudgett, Citation2019) under the guise of civilisation (Welch, Citation1988).

Despite higher education existing in Australia for 170 years, Indigenous Australians’ participation has been relatively recent, with fewer than 100 students enrolled in university in the early 1970s (Gale, Citation1998). This entry of Indigenous Australians to higher education has been underpinned by equity aspirations and the ongoing endeavour to reach parity of participation and outcome (Bunda, Zipin, & Brennan, Citation2012; Wilson & Wilkes, Citation2015). In contrast to millennia of sophisticated educational processes prior to colonisation, the first Indigenous person to receive a tertiary qualification is believed to be Dr. Margaret Weir, who was awarded a Diploma of Physical Education from Melbourne University in 1959 (Cleverley & Mooney, Citation2010). The first Indigenous person known to receive a doctoral qualification was Dr. Bill Jonas, who was awarded a PhD in 1980 from the University of Papua New Guinea (Bock, Citation2014; New South Wales Board of Studies, n.d). Whilst there is a body of literature that articulates the structural and systematic challenges facing Indigenous students, Thunig and Jones (Citation2020) indicate that minimal research has been undertaken on how we can best support Indigenous Australians to become effective academics, researchers and teachers. We concur, though we would suggest that there is an even greater dearth of literature that addresses how Indigenous people can become strong leaders in higher education at the Senior Executive level. Given this relatively new relationship between Indigenous Australians and the higher education sector, the sector is still processing how, as Indigenous people, we might contribute to the overall leadership structures within Australian universities. This paper assists in addressing this void by providing comprehensive insight into the roles and functions associated with senior Indigenous positions.

This paper defines the key positions in universities that have an Indigenous specific remit, are occupied by an Indigenous Australian, and are of the Dean, Pro Vice-Chancellor (PVC) or Deputy Vice-Chancellor (DVC) levels, as the ‘senior Indigenous leadership’ positions. There are other positions in existence that hold a title of Director, Assistant or Deputy Pro Vice-Chancellor – however, they are not viewed as senior positions, but rather ‘a stepping stone towards the introduction of such a position’ (Page, Trudgett, & Sullivan, Citation2017, p. 36). It is, however, clear that the number of senior Indigenous positions continues to steadily increase with time (Coates, Trudgett, & Page, Citation2020a, Citation2020b), fuelled by sustained Indigenous advocacy by groups such as the Indigenous Higher Education Advisory Councils and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Higher Education Consortium (Page et al., Citation2017). Since the first Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous appointment at Charles Darwin University in 2009 the growth in similar appointments has been bolstered by the explicit commitments to such appointments by Universities Australia (Universities Australia, Citation2017) and by requirements for Indigenous supplementary funding to universities to have senior Indigenous appointments involved in governance (Buckskin et al., Citation2018). While not the focus of this study or paper, we recognise there are other Indigenous academic, professional staff, research leaders and Elders who provide significant leadership contributions to universities throughout Australia.

At the time of writing this paper, there were 28 Senior Indigenous roles in the 39 public Australian universities. While the roles have considerable overlap in role expectations, their institutional contexts can differ. For example, some universities have over one thousand Indigenous students enrolled in their institutions and others have enrolments in the low hundreds. Similarly, Indigenous staff numbers vary across the sector. Some of the senior Indigenous leaders also lead their Indigenous student support centres as part of their roles, while other institutions have both a head of the Indigenous centre and a Dean, Pro Vice-Chancellor or Deputy Vice-Chancellor role. Now that the demands for greater involvement in Indigenous governance (Gunstone, Citation2013; Indigenous Higher Education Advisory Council, Citation2006; Pechenkina & Anderson, Citation2011) are being heeded, it is imperative to better understand how those roles can and do function optimally in Australian universities.

Walan Mayiny: the leadership study

The research employed a qualitative approach to examine Indigenous leadership in Higher Education. The study was funded by the Australian Research Council, with the first two authors being the Chief Investigators of the grant. The project is underpinned by Rigney’s (Citation1999) notion of emancipatory Indigenist research and Indigenous Standpoint theory (Foley, Citation2003), which privileges Indigenous epistemologies. It centres Indigenous voices in three of the five stages of the study, with a view to highlight their experiences as valuable contributors to the higher education sector.

Participants and recruitment

The study comprises of two key phases. Phase one includes five sets of participants, grouped into ‘stages’ as illustrated in . Phase two analyses institutional rhetoric, such as Indigenous Student Success Program(ISSP) Reports and Strategic Plans across every Australian university. The Indigenous Student Success Program is a Commonwealth Government Program that commenced in 2017 with a mission to provide supplementary funding to accelerate Indigenous enrolment, progression and completion in higher education. It can be used to fund initiatives such as scholarships, tutorial assistance, mentoring, safe cultural spaces and other services deemed necessary to support Indigenous student success (Department of Minister and Cabinet, Citation2018).

This paper uses data from stage two, three and four of the studies, which are described in detail below. Stage one involved three recruitment professionals who had experience in assisting universities to fill an Indigenous leadership position at the Dean, Pro Vice-Chancellor or Deputy Vice-Chancellor levels (see Trudgett, Page, & Coates, Citation2020). Stage five of the research includes the voices of international First Nation people who occupy senior leadership positions. Recognising the question of how to best integrate and involve Indigenous people into the leadership structures of institutions is not just an issue for Australian universities, the Walan Mayiny study included four First Nation leaders from Canada, five from New Zealand and four in North America. Their collective voices enable the study to understand First Nation leadership in higher education from a globalised context. The term First Nation is one commonly understood but rarely defined in the global context. In application, we are referring to the population of people who are the culturally distinct native custodians of the land prior to being colonised by another ethnic group, e.g., the First People of Canada, New Zealand North America.

The second stage of the study consisted of Indigenous Australians who hold an Indigenous specific position of Dean, Pro Vice-Chancellor or Deputy Vice-Chancellor. In 2018, when the data was collected for this stage of the study there were 22 Indigenous Australians in these positions. All received an invitation to participate in the research, with 14 (64%) taking part in the research. Emphasis was placed on their engagement with staff, students and community; challenges faced in their positions; key achievements and goals; governance structures; the characteristics of Indigenous leadership; and relationships with senior executives.

The third stage encompassed the university senior executive. All 39 Vice-Chancellors overseeing Australian universities were invited to participate in the study. A total of 27 (69%) Vice-Chancellors participated in the study, 4 (10%) did not respond, 2 (5%) were somewhat indecisive/non-committal, 3 (8%) declined the invitation and 3 (8%) delegated the opportunity to another member of their senior executive. The participants who had been asked by their Vice-Chancellor to take part comprised of one Provost and two Deputy Vice-Chancellors. One Vice-Chancellor asked that another member of their Executive team to also take part in their interview. In summary, we had 27 Vice-Chancellors and four other members of Senior Executive from a total of 30 universities participate in the study.

Stage 4 comprised of Indigenous Academics ranging from Level A/Associate Lecturers through to Level E/Professors. Coates, the third author of this paper, was assigned this specific stage of the study as the main component for their PhD research. Importantly, the study captured experiences from staff across 35 of the 39 universities in Australia, which was of key importance given the specific differences across locations, i.e., the complexities of attracting staff to regional areas, the cultural diversity in different regions, and the geographical scope of areas that institutions serve.

Data collection and analysis

Most of the interviews for stages two, three and four were conducted in person (face-to-face) at the participant’s office or nominated location. Of the three interviews that were not conducted face-to-face, two were conducted via telephone and one using video conferencing technology. The interviews were transcribed and sent to participants for review.

NVivo software was employed to manage the considerable interview transcript data generated throughout the research (Al-Yahmady & Al-Abri, Citation2013). Each transcript across the three stages was analysed in detail for emerging themes, connections and disagreements (Bazeley & Jackson, Citation2013; Charmaz, Citation2006) whilst also incorporating researcher insights into an interactive interplay with the data (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990).

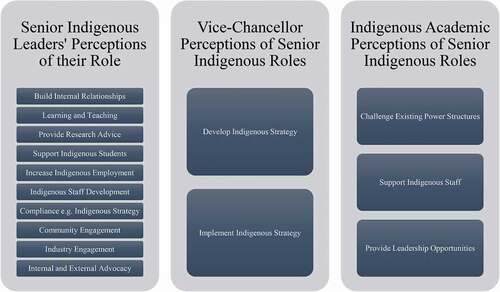

Findings: exploring the expectations and responsibilities of the senior Indigenous leadership roles

The responsibilities of senior Indigenous leaders are examined from the perspectives of the three different groups of stakeholders identified above. First, we view the functions and responsibilities of these positions through the voices of the senior Indigenous leaders. Second, we outline what the Vice Chancellors understand this role does, noting their emphasis on strategic initiatives. Third, we highlight what Indigenous academics think about the role, focusing on aspects such as advocacy and need for that position to create opportunities for others. During the interviews and through analysis of the collective stage 2 and 2 transcripts, it became increasingly apparent that both senior executives and Indigenous academics had differing perspectives on the roles of the senior Indigenous leaders. Similarly, many of the senior executive and Indigenous academics appeared to have minimal understanding of the extensive scope associated with the senior Indigenous leadership positions both within their institution and across the sector more broadly. This section will then conclude with a discussion about the characteristics required of people in senior Indigenous leadership positions, which may be useful for future considerations when appointing these roles.

Senior Indigenous leaders’ perceptions of their roles

All senior Indigenous leaders were asked about what activities their roles encompassed. Though there were some slight differences in terms of focus areas, which was usually influenced by the Vice-Chancellor direction and skillset of the incumbent (Trudgett et al., Citation2020), analysis revealed considerable overlap in tasks. The responsibilities of these roles encompass are now outlined according to those relevant to the internal operations within the university, followed by those that focus more on external relationships. The subsequent tension that arises between operational and strategic imperative is then discussed.

Internal university responsibilities of senior Indigenous leaders

Participants often commented on the importance of senior Indigenous leaders being able to influence other members of the University Executive to build and foster strong relationships. The more specific aspects of the senior Indigenous leader’s portfolios covered areas such as:

Learning and teaching – often involving complex university-wide initiatives such as Indigenous graduate attribute work, Indigenising curriculum and pedagogical advice across all disciplines.

Research – inclusive of providing advice to non-Indigenous and Indigenous students and staff about their research and also providing guidance on ethics, initiatives introduced by external funding organisations (such as the Australian Research Council) and advice on university research strategies.

Indigenous students – responsibility to ensure all Indigenous students within the institution receive appropriate pastoral, cultural and academic support. Some senior Indigenous leaders indicated apart from their senior leadership role, they were Directors of the Indigenous Student Support Centre within their institution, whilst others had a separate Director who usually reported to them.

Human Resources – senior Indigenous leaders were often deemed responsible for ensuring that Indigenous employment targets were met. This should be viewed as a whole of university responsibility given the Indigenous budget is often quite limited.

Staff development – some senior Indigenous leaders spoke about the need to develop and support Indigenous staff within their institution.

Compliance – Ensuring that the university is aligned with national Indigenous higher education priorities and international principles that apply to Indigenous people.

Whilst the following responsibilities did not emerge from the data, our observations across the sector and experience in senior positions indicate that these responsibilities could be extended to include numerous other tasks such as marketing/branding, finance, event management, procurement, advancement/philanthropy, building and campus development and internationalisation.

External responsibilities of Indigenous senior leaders

The senior Indigenous leaders identified several external focused responsibilities within their portfolio. Community engagement emerged as a key theme within the data, with this group speaking in detail about the need to carefully engage with the Indigenous community and how this requires a certain skillset. Engagement with Indigenous alumni emerged as an important theme in the data. The need to be aware of what the expectations of the local community are, and to be conscious of the sensitivities and politics within the community, is considered an essential element within the role.

Another component mentioned is the ability to undertake meaningful industry engagement that ultimately results in benefits to both the university and broader community. This is often delivered through partnerships, which can include opportunities from research collaboration through to cadetships or internships.

The third main area of external engagement is advocacy with the Government, Universities Australia, and other organisations.

We’re pushing the governments hard at the moment to stand up and make changes and to be inclusive in their agendas and to make considerations (Senior Indigenous Leader 1).

Many of the senior Indigenous leaders spoke in great detail about how a large portion of their time is consumed lobbying external bodies to make changes to policy, practices and existing structures. It is perhaps one of the most underestimated components to these positions in terms of the degree of time and commitment this group of people give to advocating for change.

Operational versus strategic work

As indicated above, the senior executive mentioned that a key component to the senior Indigenous leaders’ role was to drive strategy. Whilst this resonated with many of the Indigenous leaders, there was some evidence that operational tasks were sometimes more pressing, and sometimes obstructed their larger strategic aspirations.

Trying to deal with these workplace culture issues is my main job, and trying to push the broader agenda of strategy and leadership is very much secondary at the moment. Secondary because the university has put it on the backburner (Senior Indigenous Leader 2).

Despite these roles having a wide range of responsibilities, the data indicated the niche aspects of the roles. One senior Indigenous leader shared an experience where they had been in a conversation with two of the other Pro Vice-Chancellors at their institution. The other two pro vice chancellors were discussing how their roles had some overlap with Indigenous pro vice-chancellors positions and how the senior Indigenous leader could act in their roles when on leave.

If you were here – I was going away too – they said you could act in our position. Then we got further in the conversation and they went, no we couldn’t act in yours (Senior Indigenous Leader 3).

This is a good example of how the Indigenous leaders are required to have a range of skillsets that are transferable to numerous wider portfolios, but their roles are deemed highly specialised and that very few people can actually successfully execute – even in this instance non-Indigenous people holding the same level of positions within the same institution.

Some institutions appointed a Dean for their senior Indigenous leader. One such incumbent indicates that such titles fail to denote the scope of the role and are both structurally and ethically inapt.

I was doing the whole of university role. It wasn’t located within an academic unit, whether it was a college, school or faculty … I’d been arguing for a senior position, the senior officer’s position of the university should be, at a minimum, Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous level. The ISSP guidelines and the eligibility for those funds make the statement that there should be a senior Indigenous officer at Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Pro Vice-Chancellor or equivalent level. [The person] who I reported to argued that the Dean’s role was equivalent …. I debated that and argued that it was not the case. I argued that the position was not being paid at a Pro Vice-Chancellor level (Senior Indigenous Leader 4).

It was clear that there were discrepancies between how the senior Indigenous leaders understood their roles and how the University Executive perceived them. One senior Indigenous leader shared that their Provost had agreed that a vital component of their role was to keep the university honest.

It is clear from the expansive list of activities that the senior Indigenous leaders have considerable breadth and depth to their portfolios, often revealing that they did not have adequate support to assist them to realise their goals.

[I’m] doing all that operational stuff as well. So, it gives me about two seconds a day. I used to be busy before, but now I’m really busy … It wouldn’t happen anywhere else in the university … but they [University Executive] think the Indigenous area can just wait for resources (Senior Indigenous Leader 5).

The roles span both the specific Indigenous area and more broadly across the institutions. This comprehensive portfolio of work, coupled with the high expectations of Senior Executives and Indigenous Academic staff, suggests that these roles are challenging both professionally and personally. The data further suggest that only the senior Indigenous leaders have a coherent understanding of the complexities of these positions as we outline below.

Vice-chancellor perceptions of the senior Indigenous roles

The Vice-Chancellors all expressed an interest in Indigenous Higher Education and a keen impetus to ‘do the right thing’. However, there were considerable differences in terms of the knowledge this group had about the senior Indigenous roles, particularly in relation to their functions, scope and impact across the university. One vice chancellor who had a good grasp of the position breadth described the role as ‘It’s a facilitator. It’s an engager. It’s a promoter. It’s an advocate. That’s the key … ’. The other senior executive identified the responsibility of their senior Indigenous leaders was to develop and implement an Indigenous Strategy within their institution. Two interesting aspects emerged from these discussions: first, not all institutions with a senior Indigenous appointment had an Indigenous Strategy, signalling that the Vice-Chancellor may not completely understand the strategic imperatives within the Indigenous portfolio. Second, some Vice-Chancellors spoke about their Indigenous Strategy as being a university wide responsibility, which ought to be led from all members of the Senior Executive, inclusive of the Vice-Chancellor; whilst others spoke about it as the predominantly sole responsibility of the Indigenous leader. The (Universities Australia, Citation2017–2020) Indigenous Strategy (Universities Australia, Citation2017) was also mentioned by several of the Vice-Chancellors with many referring to it as a national commitment to improve Indigenous engagement and success across the sector. Whilst there was general excitement about this strategic document, it was rather disappointing, given the peak body commitment to the document, to learn that some Vice-Chancellors were not familiar with the document. For example, one Vice-Chancellor of a university with a Senior Indigenous appointment indicated:

I have no idea what Universities Australia’s Indigenous strategy says … I should’ve paid more attention to it and I didn’t. I’m sorry (Senior Executive 1).

Several of the Vice-Chancellors indicated that the senior Indigenous positions were different to all other senior positions within the University because they carried with them a deep sense of personal and emotional commitment.

The additional requirements for this role would be the sensitivities that may surface as a result of these roles. So, if someone is a DVC Academic or a DVC Research or a Dean of Engineering, we generally don’t encounter a lot of prejudice and preconceived ideas … So you don’t get that same – that is as much connected to that personal identity. So this is a role that carries, I think for the individual, an increased pressure to be public, but to be personal in a public sphere and to take your cultural identity and your beliefs into your work world in a way that’s much more explicit, visible, open. That takes risk and courage (Senior Executive 2).

This Vice-Chancellor went on to further explain the burnt out feeling that some senior Indigenous leaders’ experience.

But it takes a lot of energy and I think that’s where you can get burn out. …. But when it’s your whole identity and you’re always in the spotlight and the way that you have to operate all the time with the very many groups have a legitimate call on your time. That is huge. This is why when these roles are created I think they need to be really carefully scoped, understood, located correctly in the university setting and very, very well supported (Senior Executive 3).

The personal aspect of the role resonates with the data provided by both the senior Indigenous leaders and the Indigenous academics.

The Senior Executives emphasised the strategic, big picture, aspects of the roles as opposed to the operational responsibilities. Perhaps because of this, many were unable to articulate the scope of responsibilities within the portfolios. There was a tendency for this group to be able to articulate the actual functions within other Executive positionsfor example, Deputy Vice-Chancellor Research or Deans – however, in most cases this was not evident for the senior Indigenous position.

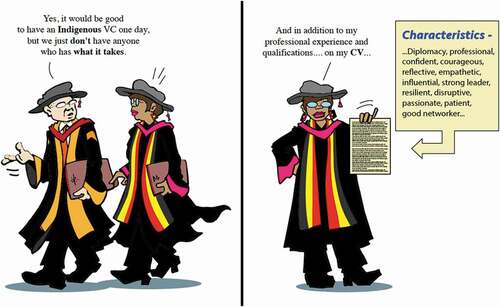

It is therefore not at all surprising that a key challenge linked to the senior Indigenous appointments is career progression. One of the Vice-Chancellors commented that the cultural expectation still fits a white male better than it fits anybody else unfortunately. The equity conversation is yet to progress thinking about how the vast experiences and skillset of senior Indigenous leaders can be extended into higher positions such as non-Indigenous identified Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Provost or Vice-Chancellor roles.

I’m hoping that with the increasing cohort of Indigenous PhDs, with the increasing cohort of university educated Indigenous people that we’re moving to a time where we will be thinking about it less in terms of, we need a trophy Indigenous senior position. More that we just have senior Indigenous [people in positions]. I mean look we – the Vice-Chancellors’ group is incredibly Anglo-Celtic and white. We need to change that (Senior Executive 4).

It is certainly time for the Vice-Chancellors to learn more about the intricacies of the Senior Indigenous positions and consider ways to disrupt the Anglo, white, male space that dominate senior executive positions.

Indigenous academic perceptions of senior Indigenous roles

When asked to share their thoughts about the senior Indigenous appointment in their institution, Indigenous Academics revealed a broad range of opinions. Key ideas included the expectation that the senior Indigenous leaders would challenge existing power structures and the perceived benefits – or lack of – to individual academic staff. Some participants were extremely supportive of both the positions themselves and the people occupying these positions. Conversely, others were less supportive of such positions and/or the people holding these positions.

It’s not overly well-perceived … initially [we] were very happy to have this role and would see a lot of change and a lot of inclusion when it came to student engagement, community engagement and seeing more Indigenous Academics being brought into [the university]. It’s been a year-and-a-half now and no change has been seen. So it’s not hugely positive to be honest … [we’re] not confident in [the senior Indigenous leader] - well in that role (Indigenous Academic 1).

An interesting aspect that emerged is that a small number of Indigenous academics felt disconnected from their senior Indigenous leader.

I’m not intimately connected to the position … I really have nothing to do with the position at all. I’m just an Aboriginal Academic (Indigenous Academic 2).

In some instances, participants reported feeling isolated or insignificant, despite having a senior Indigenous leader at their university. This was attributed to the person holding the Senior position not taking the time to engage with the Indigenous Academics within their university.

I would’ve expected that there was a direct connection [between my role and the PVC Indigenous role]. However, it seems to be quite far removed and there’s no support from this particular role … [They’re] very vacant in that area (Indigenous Academic 3).

The position itself doesn’t mean anything unless the people who create the position are being genuine. I’ve been involved in other spaces where it’s not genuine; the person doesn’t have any power; they’re kept away from the actual staff - or they keep themselves away and then they move on to more money; there’s no genuine connection (Indigenous Academic 4).

The notion of connection through meaningful engagement and relationships proved paramount for these roles to have the most chance of success.

Challenging existing power structures

Indigenous Academics were incredibly mindful of issues relating to power structures, systems and status. As a group, they identified that a key component of the Senior Leadership position was to dismantle the power structures within the academy to ensure that there is a place for Indigenous Australians to be able to participate and succeed in higher education. For instance, one participant spoke quite positively about their Indigenous Leader and what they might bring to their institution.

With the new role I think people are excited about the opportunities that the person will bring and the status and power within the structure to be able to effect change. That’s what we’re always hoping for that they have influence at the executive level and are able to make a change (Indigenous Academic 5).

In cases where the Senior Leadership position was already established, a number of participants witnessed their senior Indigenous leader driving change, ensuring there was a whole-university approach to Indigenous education.

[The PVC Indigenous is] really pushing the boundaries at a number of levels (Indigenous Academic 6).

The strength is clearly that we have a senior manager who can not only be at the table but try and change the table (Indigenous Academic 7).

Similarly, several of the Indigenous academics spoke in detail about the role of the senior Indigenous leader in terms of a position of advocacy across the institutional structures.

I think it’s really important that the PVC role advocates and support the good work in the faculties, not just the Aboriginal Education Centre (Indigenous Academic 8).

The PVC is part of that higher Executive, so it means that we have an ally at the top end as well. So that works really well if we’re trying to push for more research or create something better. [They’re] actually a really great advocate for us at those higher levels (Indigenous Academic 9).

The Senior Executives’ desire for strategic advancement in the Indigenous sphere seems to be echoed by the Indigenous staff, creating high expectations for the senior Indigenous leader to achieve visible outcomes.

Benefit (or not) to individual Indigenous academics

One element that did clearly emerge from the data analysis is that Indigenous Academics tend to link the importance and success of such positions with the benefits, or in some cases, the lack of benefits that such positions can bring to their own professional experience. In this example, the strategic growth in Indigenous staff fostered by the senior position has engendered a positive working environment for academics.

I’ve got a great relationship with the Pro Vice-Chancellor. They are a fabulous colleague and I’ve always felt supported … I feel like this position has been a godsend to me (Indigenous Academic 10).

Similarly, another Indigenous Academic valued the senior Indigenous leadership position at their university, seeing it as a person who they could go to if they had questions and to seek advice, indicating these people usually have good knowledge of the university systems and community.

If there’s nobody in place then – especially now, here, the roles are kind of blurred and you don’t know who’s responsible for what. Whereas when you have one person that’s responsible for everything Indigenous, whether that be research, education or anything, then you actually know who to go to and you know where the buck stops. You know who’s responsible, and if they’re not responsible, then they’ll tell you who’s responsible (Indigenous Academic 11).

Despite many of the Indigenous academics reporting on how the senior Indigenous roles had a positive impact on their careers, some suggested that these roles had minimal, if any, impact across the broader institution, particularly those who viewed the senior Indigenous leader had not taken the time to provide leadership opportunities for the next generation of senior Indigenous leaders. For example, when asked about how the senior Indigenous leadership position impacts their position in the university, one participant responded:

There’s a big jump between my position, where I’m a Senior Lecturer, and I don’t see a lot of other Indigenous staff at my university, so I can’t see my career projection through the university. There’s no Deans, there’s no Associate Deans, there’s no – I don’t think there are any Professors. There’s not a lot of positions (Indigenous Academic 12).

Overall, the Indigenous Academics were not conclusively supportive nor unsupportive of the senior Leadership positions. There was, however, widespread agreement that these roles were important as positions that could advocate for positive change through dismantling colonial power structures within the higher education sector and as a consequence open up opportunities for other academics.

The great expectations of senior Indigenous leaders, as well as the scope of their role, are illustrated in . Understanding the demands of these roles can be challenging and are further complicated by institutional environments that vary in financial and strategic support for such roles, potentially creating unrealistic demands of the incumbents.

Figure 2. Great expectations: role expectations and requirements of Indigenous senior leaders in Australian universities.

Given the complexity, we now outline the characteristics that Senior Executives, Senior Indigenous Leaders and Indigenous Academics suggest are critical to these roles.

Indigenous leadership characteristics

The Senior Executive cohort believed that it was necessary for the Indigenous Leaders to possess the same type of characteristics as would be expected by other members of Executive, for example, diplomacy, professionalism, confident, courageous, reflective, empathetic and the ability to influence others.

This person will be making an influence – making an impact through influence, not direct line reporting through a massive group of staff reporting to them …. This person needs to have incredible influencing skills and negotiation skills and the soft diplomacy skills (Senior Executive 5).

However, many of the Senior Executives extended this by saying that the leadership characteristics required of Indigenous Leaders were more extensive as they also required a diverse range of specific cultural skills, which might be termed cultural soft skills, such as patience, resilience and networking capability. As we note below, these are not the usual soft skills but a set of attributes deemed necessary because of potentially hostile environments and negotiating of complex intercultural relationships. Several shared that Indigenous Leaders are often called upon for commentary on sensitive national matters, e.g., Australia/Invasion Day, the Uluru Statement from the Heart and the playing of the national anthem at ceremonies.

The data suggests that the array of leadership characteristics held by senior Indigenous leaders is likely to bring significant benefit to the sector, yet that value is often under-estimated and sometimes taken for granted. It became apparent during the course of the interviews with the Senior Executive that many had not thought deeply about what their Indigenous leaders bought to their institution, their unique skillset and ability to lead two quite different spaces – the academy and Indigenous communities.

Being Indigenous actually does bring a credibility, beyond the expertise and beyond the experience. If you just take those things – I think having the personal connection to community, to country is – does add something that’s a bit intangible, that is good and valuable. Beyond Indigenous background, then I think the skills required are probably different in another subtle way. Although I’m hoping it’s not an issue in this university, although I can’t absolutely say on every count, I hope it’s getting to be less of an issue across Australia and that is the capacity to deal with prejudice (Senior Executive 6).

This Vice-Chancellor went on to further explain the innate discrimination and prejudice that people in these positions were forced to contend with as part of their jobs.

If you look at some of the other fields or the other positions … I don’t think they have the degree – the potential for innate human bias to be quite as strong. … Therefore, I think that’s an extra burden, if you will, on people in these senior Indigenous leadership roles, is that they are comfortable and have the personal skills to deal with that in a way that helps them to be effective and doesn’t get them into open warfare with people (Senior Executive 7).

Whilst we understand they are noting the very real additional expectation and burdens placed on Indigenous leaders, the notion of these people having an element of comfort is concerning. An alternative angle to interpret this is through a position of resilience, which is often developed over one’s lifetime. The notion of resilience was mentioned by both the Senior Executive and senior Indigenous leaders throughout the study. Analysis of the data from the Indigenous leaders clearly points to a reality that offers no comfort in their roles. In fact, one could argue that their positions are disruptive – they disrupt the notion of a Western academy, disrupt colonisation by placing focus on Indigenous knowledge and self-determination and disrupt Australia’s ability to stereotype Indigenous people as uneducated and impoverished through their broad professional and cultural capacities.

Like many of the other Senior Executives, one participant explained that they believed that the senior Indigenous leader required the same leadership characteristics as other members of the Executive at the University, but pointed out that they perhaps needed an additional element of patience.

In this space sometimes, the patience is important only because there will be so many setbacks and that’s why actually passion and patience needs to be balanced. If you have too much patience you won’t create change. So you don’t want to have that (Senior Executive 8).

The balance of patience emulates the delicate balance of the Goldilocks fairy-tale and perhaps reflects the unrealistic expectations of the individuals appointed to these roles. This Senior Executive went on to add how much they rely on their senior Indigenous leaders to provide valuable networking opportunities for the University.

Conclusion

Despite scholars such as Forsyth (Citation2014) proposing that the original higher education architects were innovative, it cannot be ignored that such practices completely dismissed Indigenous Australians of our place in the academy. Pioneers of Indigenous education worked tirelessly to redesign parts of the Australian higher education sector's grand architectural plan so that doorways opened for Indigenous people as both students and staff. This has been no easy feat, and their struggles in the redesign process have been met with embrace, curiosity and unfortunately sometimes opposition. Whilst the doors have gradually been plied open by grit and determination, and we have more Indigenous people studying and working within Australian universities than ever before, we are not present in every room nor are we present at every level of senior position.

Senior Indigenous leaders require a skillset and knowledge base that is both broad and deep, encompassing all aspects of an institution’s portfolio. Whilst the final publication associated with the study will establish a model of best practice for the inclusivity of Indigenous leadership in higher education governance structure and will include a number of significant recommendations, we suggest that more work needs to be undertaken across the Australian higher education sector to ensure a more widespread understanding of what these positions entail. Through opportunities such as executive meetings within institutions through to conferences with bodies such as Universities Australia, senior Indigenous leaders should be invited to share more broadly the details of their positions along with the key challenges they face in executing their roles.

Compellingly, senior Indigenous leaders are required to possess all the attributes expected of other members of Senior Executive whilst also possessing an additional set of personal and cultural competencies. As illustrated in below, despite the expectation to have ‘more than’ others, there was widespread indication that the experience gained within these portfolios would not position one to be deemed competitive for a Provost or Vice-Chancellor position.

We encourage the Australian higher education system to review how it interprets, interacts, and responds to these roles. They should never be viewed as supplementary to other portfolios, but rather core to all components of university business. Emerging and current senior Indigenous leaders are one of the sector’s richest assets, which have tremendous power to challenge how the higher education system in Australia operates. Together, let us continue to ply open the heavy doors that lead to the Boardrooms and ultimately, the Vice-Chancellors Office.

Declaration

This manuscript is an original work that has neither been submitted to nor published anywhere else.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank the 80 people who participated in this research by kindly sharing their knowledge and experiences with us. We would also like to thank the Australian Research Council for funding this project (IN180100026).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Yahmady, H.H., & Al-Abri, S.S. (2013). Using NVivo for Data Analysis in Qualitative Research. International Interdisciplinary Journal of Education, 2(2), 1–6. http://www.iijoe.org/v2/IIJOE_06_02_02_2013.pdf

- Bazeley, P., & Jackson, K. (Eds.). (2013). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. London: Sage.

- Bock, A. (2014, March 17). Academics open doors to social benefits. The Age- Education Supplement. pp. 14.

- Buckskin, P., Tranthim-Fryer, M., Holt, L., Gili, J., Heath, J., Smith, D., and Ma Rhea, Z. (2018). NATSIHEC accelerating Indigenous higher education consultation paper. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Higher Education Consortium. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/123520/1/NATSIHEC_%20AIHE_FinaL_%20Report%20Jan%202018_updated_031218.pdf.

- Bunda, T., Zipin, L., & Brennan, M. (2012). Negotiating university ‘equity’ from Indigenous standpoints: A shaky bridge. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(9), 941–957. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2010.523907

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, England: Sage.

- Cleverley, J., & Mooney, J. (2010). Taking Our Place: Aboriginal Education and the Story of the Koori Centre at the University of Sydney. Sydney University Press. Pp, 27–28.

- Coates, S.K., Trudgett, M., & Page, S. (2020a). Examining Indigenous leadership in the academy: A methodological approach. Australian Journal of Education. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944120969207

- Coates, S.K., Trudgett, M., & Page, S. (2020b). Indigenous higher education sector: The evolution of recognised Indigenous Leaders within Australian Universities. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2019.30

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

- Department of Minister and Cabinet. (2018). ISSP Post-Implementation Review 2018 discussion paper. http://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/ISSP-review-discussion-paper-2018.pdf

- Foley, D. (2003). Indigenous epistemology and Indigenous standpoint theory. Social Alternatives, 22(1), 44.

- Forsyth, H. (2014). A history of the Modern Australian University. Sydney: University of New South Wales Publishing.

- Gale, P. (1998). Indigenous Rights and Tertiary Education in Australia. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education (Adelaide, Australia, November 29 December 3).

- Gunstone, A. (2013). Indigenous leadership and governance in Australian universities. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 6(1), 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v6i1.108

- Horne, J., & Sherington, G. (2010). Extending the educational franchise: The social contract of Australia’s public universities, 1850–1890. Paedagogica Historica, 46(1–2), 207–227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230903528637

- Indigenous Higher Education Advisory Council. (2006 September 18–19). Partnerships, pathways and policies, improving Indigenous education outcomes, Conference Report of the Second Annual Indigenous Higher Education Conference. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government.

- Ma Rhea, Z., & Russell, L. (2012). The invisible hand of pedagogy in Australian Indigenous studies and Indigenous education. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 41(1), 18–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2012.4

- North, S. (2016). Privileged knowledge, privileged access: Early universities in Australia. History of Education Review, 45(1), 88–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/HER-04-2014-0028

- Page, S., Trudgett, M., & Sullivan, C. (2017). Past, present and future: Acknowledging Indigenous achievement and aspiration in higher education. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 4, 29–51. Downloaded from www.herdsa.org.au/herdsa-review-higher-education-vol-4/29-51 (3rd June, 2020).

- Partridge, P.H. (1965). Universities in Australia. Comparative Education, 2(1), 19–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006650020103

- Pechenkina, E., & Anderson, I. (2011). Background paper on Indigenous Australian higher education: Trends, initiatives and policy implications. Canberra. ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Perry, L., & Holt, L. (2018). Searching for the Songlines of Aboriginal education and culture within Australian higher education. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(3), 343–361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0251-x

- Povey, R., & Trudgett, M. (2019). There was movement at the station: Western education at Moola Bulla, 1910–1955. History of Education Review, 48(1), 75–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/HER-10-2018-0024

- Rigney, L.I. (1999). Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: A guide to Indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo Sa Review, 14(2), 109–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1409555

- Thunig, A., & Jones, T. (2020). Don’t make me play house-n***er’: Indigenous academic women treated as ‘black performer’ within higher education. The Australian Educational Researcher. Published online 7th August, 2020, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00405-9

- Trudgett, M., Page, S., & Coates, S.K. (2020). Talent war: Recruiting Indigenous Senior Executives in Australian Universities. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. Published online 18 May, 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2020.1765474

- Universities Australia. (2017). Indigenous Strategy 2017–2020. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory. https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/policy-submissions/diversity-equity/universities-australias-indigenous-strategy-2017-2020/

- Welch, A.R. (1988). Aboriginal education as internal colonialism: The schooling of an Indigenous minority in Australia. Comparative Education, 24(2), 203–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006880240205

- Wilson, K., & Wilks, J. (2015). Australian Indigenous higher education: Politics, policy and representation. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 37(6), 659–672. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2015.1102824