ABSTRACT

Teaching evaluation is deeply entrenched in institutional quality assurance and is a feature of a range of policies including academic recruitment, promotion, and performance management. Universities must ensure that evaluation practices meet regulatory requirements, while balancing student voice and wellbeing. There is extensive literature examining the validity, reliability, and bias of student surveys, but limited focus on institutional evaluation strategies and what constitutes best practice. This study analyses and reports on the teaching evaluation strategies and practices of Australian and New Zealand universities. All 29 participating institutions use standardised and centrally deployed surveys to evaluate teaching and participated in external student experience surveys to benchmark nationally. Comparisons are provided between the strategic intent of evaluation; survey practices, technology, analysis, and reporting; and the use of other nonsurvey methods. The study informs higher education institutions’ evaluation strategy, policies, and practice and provides an agenda for reframing approaches to evaluation of teaching.

Introduction

The vexed questions of how best to seek students’ feedback on their learning and teaching experiences and how to ensure rigorous yet equitable evaluation to meet quality assurance requirements have been vigorously debated for the past five decades (Harrison et al., Citation2022). Effective learning and teaching evaluation practices can provide academics, administrators, and institutions with specific, useful, and actionable data to identify areas for improvement and uncover teaching excellence and innovation (Cherry, Grasse, Kapla, & Hamel, Citation2017; Darwin, Citation2017). Evaluation also provides accountability and avenues for the student voice in their educational experience (Stein, Goodchild, Moskal, Terry, & McDonald, Citation2021). Although universities face similar challenges in relation to evaluation, there is little information available to identify and benchmark effective practice. This study aimed to bring together information about the learning and teaching evaluation strategies and practices of Australasian universities and to analyse practices with reference to the literature.

Literature review

The intent and utility of learning and teaching evaluation

Learning and teaching evaluation is embedded in higher education quality processes. External referencing is mandated by the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) in Australia and the Academic Quality Agency (AQA) in New Zealand, and benchmarking of student evaluation data is facilitated through government-funded open access websites such as ComparED (Australian Government, Citation2020). Furthermore, transparency is lacking around how Australian universities have responded to regulatory requirements for external referencing (McCubbin, Hammer, & Ayriss, Citation2022).

Student evaluation of teaching (SET) surveys are the dominant mechanism for identifying student satisfaction with higher education subjects, courses, and teaching, with an estimated 16,000 institutions worldwide using SET surveys (Cunningham-Nelson, Baktashmotlagh, & Boles, Citation2019). Other commonly used teaching evaluation methods include formative and summative peer review of teaching and small group techniques for obtaining student feedback (Berk, Citation2018). Although SET surveys are widely used in higher education institutions across the world, many institutions face common problems with SETs, including ageing survey technology, declining response rates, perceptions that students are oversurveyed, and academics’ concerns about the validity of SETs (Stein, Goodchild, Moskal, Terry, & McDonald, Citation2021). The dominance of SETs is reflected in the literature, with SET surveys now claimed to be the most researched topic in higher education (Heffernan, Citation2022b). The bulk of the SET literature focuses on validity, reliability, and bias concerns (Spooren, Brockx, & Mortelmans, Citation2013; Spooren, Vandermoere, Vanderstraeten, & Pepermans, Citation2017).

Validity is of course inextricably connected to the purported purpose of student evaluation of teaching: Are SET surveys intended to capture data about student learning, teaching quality, or student satisfaction with their educational experience? Are SET surveys used alone or as part of a suite of indicators of teaching quality? Importantly, there may be differences between intended and believed rationales held by academics, institutions, and institutional leaders (as well as among students) (Cherry, Grasse, Kapla, & Hamel, Citation2017).

While studies have found a relationship between students’ perceptions and learning outcomes (Lizzio, Wilson, & Simons, Citation2002), many studies have found that student evaluations do not usually measure or capture student learning (e.g., Bedggood & Donovan, Citation2012; Cadez, Dimovski, & Zaman Groff, Citation2017). Others have noted that SET instruments are often developed without due consideration of teaching quality (Alderman, Towers, & Bannah, Citation2012; Ory & Ryan, Citation2001; Penny, Citation2003; Spooren, Brockx, & Mortelmans, Citation2013). It is well established, however, that SET surveys, when used in conjunction with other data sources such as peer observation and individual reflection, are useful in improving teaching quality (Alderman, Towers, & Bannah, Citation2012; Brookfield, Citation2017; Spooren, Brockx, & Mortelmans, Citation2013). Triangulation is needed because while student perspectives provide rich insights into experience and satisfaction, students are not always best placed to evaluate teaching and subject quality because their judgements about their own learning are often influenced by subjective matters (Bjork, Dunlosky, & Kornell, Citation2013; Carpenter, Witherby, & Tauber, Citation2020). In line with discipline-based norms of research review, peer observation of teaching is considered valuable to informing teaching improvements (Cheng, Citation2009). This alignment demonstrates that academics consider it part of their professional responsibility to evaluate, reflect on, and improve their professional practice, including teaching (Brookfield, Citation2017).

Reliability questions arise around gender and race bias, and the influence of nonteaching factors on SET results. The gendered nature of student evaluation feedback is well researched, with various studies finding that female academics receive less favourable student ratings than male academics, and that women are more likely than men to receive student comments that are negative, abusive, or about matters unrelated to learning and teaching (Boring, Citation2017; Kreitzer & Sweet-Cushman, Citation2022; MacNell, Driscoll, & Hunt, Citation2015; Mitchell & Martin, Citation2018). There are, however, a small number of studies that found no gender differences in SET results (e.g., Wright & Jenkins-Guarnieri, Citation2012) or found bias against male academics teaching in traditionally female-dominated disciplines such as nursing (Whitworth, Price, & Randall, Citation2002). Racial bias in SET survey results is evidenced by studies showing that academics with ethnically and linguistically diverse backgrounds are more likely to receive lower ratings and abusive comments than white academics (Heffernan, Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Kreitzer & Sweet-Cushman, Citation2022).

Despite these concerns, student evaluation continues to be an integral component of institutional quality assurance processes, an important means for students to positively contribute to learning and teaching improvement, and a dominant method for managing academic performance, probation, promotion, and recruitment (McCubbin, Hammer, & Ayriss, Citation2022; Stein, Goodchild, Moskal, Terry, & McDonald, Citation2021), making it essential for universities to ensure that evaluation practices are as fair and effective as possible.

Evaluation methods and practices

The literature on student evaluation operations, infrastructure, and practices (e.g., frequency of surveys, technology platforms used for evaluation, distribution of surveys, reporting and analysis of evaluation data) remains underdeveloped (Penny, Citation2003). The sector interest in these issues is evident because the few recent studies in this area are highly cited (e.g., Alderman, Towers, & Bannah, Citation2012; Estelami, Citation2015; Goodman, Anson, & Belcheir, Citation2015; Nulty, Citation2008; Penny, Citation2003) and older evaluation methodological studies continue to be heavily cited (e.g., Marsh, Citation1987; Miller, Citation1984). Additionally, although literature highlights the importance of triangulating evidence to provide robust evaluation of the quality of learning and teaching (Berk, Citation2018; Smith, Citation2008), few studies have focused on how that happens at the institutional level. Prior sector scans of evaluation practice are scant, but include Alderman, Towers, and Bannah (Citation2012) Australian study, Hammonds, Mariano, Ammons, and Chambers (Citation2017) study of SET administration and interpretation in the UK and US, and Dunrong and Fan’s (Citation2009) examination of approaches to evaluation at Chinese institutions (Alderman, Towers, & Bannah, Citation2012; Dunrong & Fan, Citation2009; Hammonds, Mariano, Ammons, & Chambers, Citation2017). A 2021 study of Turkish and American educators also investigated how the design and administration of student evaluation can improve teaching quality (Ulker, Citation2021).

Most institutions have moved from paper to online surveys (Young, Joines, Standish, & Gallagher, Citation2019). While survey technology represents a large investment for universities, scholarly examination of evaluation technology choice and use is scant. One study of academic administrators identified some key trends in the use of course evaluation software, finding that important features included question standardisation and benchmarking, alignment with performance indicators, and ability to group evaluation results by course, program outcome, and institutional faculties or divisions (Marks & Al-Ali, Citation2018). However, gaps exist in our understanding of how universities select and use evaluation software.

Response rates are a key concern in the literature, and low SET response rates are often used as a criticism of the reliability of SETs (He & Freeman, Citation2021). A few studies have examined how survey processes such as timing, incentives, or dissemination approaches may affect response rates (e.g., Estelami, Citation2015; Nulty, Citation2008; Young, Joines, Standish, & Gallagher, Citation2019). Incentives are contested. While some research has found they may increase response rates (Goodman, Anson, & Belcheir, Citation2015), others suggest that response rates are more closely influenced by the extent to which students believe that their educators care about feedback and have acted on previous student feedback (Hoel & Dahl, Citation2019). Studies show that incentives such as cookies or chocolates, when provided to classes immediately before administering a SET, result in more positive evaluation of teaching, course material, and overall course experience (Hessler et al., Citation2018; Youmans & Jee, Citation2007). Others have claimed that lenient grading or lower assessment workload result in higher SET scores (Wang & Williamson, Citation2022).

Effective analysis, reporting, and use of evaluation data are an increasing focus of the literature, with strong claims that the previous focus on quantitative data, which is easy to analyse and compare, is not sufficient to inform teaching improvements because it neglects vital qualitative evaluation data, precludes consideration of context, and excludes the student voice (Alhija & Fresko, Citation2009; Shah & Pabel, Citation2020). While analysis and reporting of qualitative, free-text feedback continues to be resource-intensive, technology-enhanced methods for analysing and visualising student comments are progressing in ways that inform administrative decision-making and make academics more likely to engage with evaluation results to inform teaching improvements. (Cunningham-Nelson, Baktashmotlagh, & Boles, Citation2019; Cunningham-Nelson, Laundon, & Cathcart, Citation2021; Santhanam, Lynch, Jones, & Davis, Citation2021). Another important recent focus is screening for abusive student comments that may harm academics, or to identify students’ comments that suggest a possible risk of harm to the student themselves or to other students. These issues were previously seen as too difficult to address but are becoming less resource-intensive with the introduction of machine learning methods (Cunningham, Laundon, Cathcart, Bashar, & Nayak, Citation2022).

Although researchers have honed in on specific aspects of evaluation, the operational aspects of institutional evaluation strategies have been largely ignored in the literature. Therefore, the review of the literature identified that benchmarking data was needed on issues including evaluation strategy; student survey design, technology, and dissemination; and the use, analysis and reporting of evaluation data.

Materials and methods

This research project aimed to seek information about the evaluation practices, policies, and procedures of Australian and New Zealand universities and evaluate practices with reference to the literature to inform the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Review of Evaluation of Units and Teaching conducted in 2020. Human research ethics approval was granted by the university Human Research Ethics Committee [Approval No: 1900000390]. The population was staff members from Australian and New Zealand universities. Both countries were included because Australian and New Zealand higher education policy and institutional practice often inform each other, and institutions are governed by similar quality assurance requirements that influence institutional evaluation arrangements (Freeman, Citation2014). Participants were recruited by emailing Australian and New Zealand university evaluation teams and via the website and email newsletter of the Council of Australasian University Leaders in Learning and Teaching. Respondents were offered a choice of either completing a questionnaire using the Qualtrics platform or participating in an audio-recorded interview using Zoom videoconferencing software. The questionnaire comprised 30 quantitative and open text questions focused on: the primary intent of the institutions’ teaching evaluation activities; use of evaluation data; SET survey design; survey technology; survey frequency and focus; survey dissemination and communication methods; analysis and reporting of survey results; and other methods for evaluating teaching. As noted in the section above, these are all areas that are underrepresented in existing literature. Responses to questions were not compulsory and some questions allowed for multiple responses. A protocol was used to guide interviews, and this included the same questionnaire completed by participants using the Qualtrics platform but also allowed for additional prompts and discussion. Interviews were between 40 and 55 minutes in length and were automatically transcribed using Zoom software. The questionnaire responses from interview participants were entered into the Qualtrics platform by a research team member to facilitate analysis.

Participants

Participants from 29 of the 47 universities in Australia and New Zealand

took part in this study. Thirty-nine staff members from 29 universities responded—28 of the 39 Australian universities listed in Table A of the Higher Education Support Act 2003 (Cth) and one of New Zealand’s eight universities. Where there were multiple respondents from a single university, responses were combined. Respondents held a range of roles, including evaluations managers, evaluation data analysts, academics, academic developers, and senior learning and teaching leaders. Thirty-two participants either held specific evaluation roles or had strategic oversight of evaluation functions. Thirty-three participants completed the online questionnaire and a further six chose to participate in a recorded research interview.

Context

Australia has 39 publicly funded universities (as listed in Table A of the Higher Education Support Act 2003). In the Australian context, university quality assurance requirements are regulated by TEQSA. Higher education institutions are required to meet the minimum acceptable threshold standards against which the quality of education can be assessed under the Higher Education Standards Framework (Threshold Standards) 2021 (Cth). These standards require universities to undertake external referencing to provide evidence of the quality of their operations, and provide all students with the opportunity to give feedback on their educational experience and all educators the opportunity to review feedback about their teaching. Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching are a suite of government-endorsed surveys for higher education, the results of which inform Performance-Based Funding to the sector, and key quality performance benchmarks are made public as a way of driving quality improvements (Australian Government, Citation2020). New Zealand has eight government-funded universities. The AQA conducts regular institutional audits and promotes quality enhancement practices to improve teaching, learning, student experience, and student outcomes. As for the guidance in Australia, the AQA guidance includes an expectation that data will be externally referenced and will be triangulated. Specifically, the AQA Academic Audit Framework requires universities to engage with the student voice at all levels of the quality assurance process and ensure that data is valid and used to improve teaching and learning (Matear, Citation2020).

Results

Results are presented below in relation to the intent and methods of evaluation, SET survey practices, and analysis, reporting and use of evaluation data. As responses were not compulsory and some questions allowed for multiple answers to be selected, results do not always sum to the number of participant institutions (n = 29). The number of respondent institutions is indicated in the caption of each table and figure. A summary table showing an overview of results is provided in .

Table 1. Focus of regular SET surveys (n = 26).

Table 2. SET survey technology (n = 25).

Table 3. SET survey distribution channels (n = 24).

Table 4. Distribution of institution-wide SET response rates (n = 28).

Table 5. A snapshot of the Australian and New Zealand higher education evaluation landscape*.

Strategic intent of evaluation

Respondents were asked to identify the most important strategic focus of their institutions’ evaluation practices. The three listed options were derived from the literature about the purpose of learning and teaching evaluation (see discussion above) and included overall student satisfaction, student engagement, and the learning experience. Respondents were also able to indicate via free text response if their institution had a different strategic priority that they sought to measure through the survey. Commensurate with the literature discussed earlier in the paper we found that measuring student satisfaction was considered the key evaluation metric at the vast majority of institutions (n = 21). Two institutions indicated that student engagement and the learning experience were their most important metrics measured by their learning and teaching evaluation activities. Another said they were moving from student satisfaction towards measuring learner engagement. Five respondents were not able to identify a key metric that served as the strategic focus of their institutions’ evaluation practices.

Methods for evaluating subjects and teaching

Student surveys are the dominant evaluation method, as all Australian universities and all the respondent institutions used centrally deployed student evaluation of teaching surveys. At 12 institutions, centrally deployed SET surveys were the only standardised methods of evaluating subjects and teaching. Thirteen other institutions used SETs alongside other standardised evaluation methods, including peer review of teaching, peer observation of teaching, or small group analysis (such as student focus groups).

Survey focus

Respondents were asked to indicate the focus of centralised institution-wide student surveys. The results are shown in .

The most common focus of student evaluation surveys was the teaching experienced by the student (26 institutions). Eighteen institutions regularly surveyed students about their subject, course, or curriculum. Fifteen deployed combined subject and teaching surveys, and three regularly deployed surveys seeking feedback at the degree or program level. It should also be noted that, in Australia, annual course-level student experience surveys are government-mandated and centrally deployed to higher education students by the national Social Research Centre.

All respondents used aset of standardised core questions, although in 17 cases, these could be added to by individual academics or faculties to seek targeted feedback on areas of teaching innovation or focus. Nine institutions did not permit standardised questions to be changed or extra questions to be added. All respondents said that their SETs included at least one qualitative, free-text question, although Likert scale questions were the most used.

Survey technology

Of the 22 respondents who provided information about survey technology, 20 used proprietary software such as Blue, EvaSys, or Qualtrics. Two used their own custom software (see ). Several institutions used different software programs to deploy, analyse, and report their survey data, with several using multiple software programs to analyse and visualise SET data, for example, Excel, PowerBI, and Tableau. Only five institutions used the same software for survey delivery, analysis, and reporting.

Survey dissemination and promotion

Respondents indicated that the most common means of distributing the survey to students was via a link sent to the official student email address. Many also made the survey link available through the learning management system (LMS), while 11 made the link available during classes (see ). One university had a separate digital evaluation portal leading directly to the survey software.

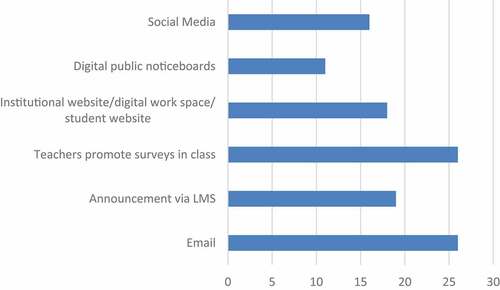

When promoting the survey to students, 26 institutions used email reminders, 19 used LMS announcements, 26 said that teachers promoted surveys in class, and 18 included communications on the student intranet and/or the institutional website. Some respondents commented that the most effective method was encouraging students to complete the survey during dedicated class time. Thirteen institutions promoted student surveys via paper posters and/or digital signage around campus, while 16 promoted surveys via official university social media accounts. Despite the widespread use of mobile and ‘nudge’ technology outside the educational sector, no respondents stated that they used SMS to promote the survey to students. summarises the survey communication methods used by respondents’ institutions.

Survey incentives

Eight institutions offered incentives to students who completed SET surveys. These included prize draws for prepaid Visa cards and vouchers for the university bookshop. Although almost one-third of participating institutions provided survey incentives, only a few were able to share any insights into their efficacy. One respondent commented that students, when contacted and informed they had won prizes, were surprised because they had not been aware of the prize draw. However, at the same institution, the response rate dropped by 1% after the removal of all prizes.

Response rates

As noted above, concerns about declining response rates have been growing in the sector. shows key response rate statistics from the universities surveyed. The response rate varies significantly between institutions, ranging from 15% through to a maximum of 74%. The median response rate for institutions was 33.5%. This median response rate is lower than response rates for large national surveys such as the Australian Student Experience Survey, which reported a 41.4% response rate in 2021 (Social Research Centre, Citation2022).

Analysis of survey data

All the respondent universities indicated that they used some form of quantitative analysis of survey data. Universities indicated that the type of analysis they performed was often limited to basic statistical analysis (mean, median, and standard deviation, or the percentage of respondents indicating ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’) and time series analysis.

Only eight institutions analysed the qualitative free-text comments provided by students. Qualitative analysis included word clouds, with one stating ‘if greater than 10 comments are received word clouds with top 5 element and sentiment lists are generated’. Others used software such as NVivo to identify themes. More sophisticated approaches used sentiment analysis to show the proportions of positive, negative, and neutral comments.

Six institutions considered potential bias and equity concerns when analysing and reporting survey data. Their responses included analysing differences in student response according to the gender of the educator and ensuring that low response rates were not reported.

Reporting of survey results

Sixteen institutions deployed survey reports to staff members by email, although at 21 institutions, users could access or self-generate reports. Access to survey results varied between institutions. All respondents indicated that the unit or subject coordinator would have access to the survey results pertaining to their subject. Twelve institutions allowed all teaching staff involved in the subject to access results. At eighteen institutions, the head of school had access to survey results for all subjects and teachers within their scope of control. Other examples of roles that had broad access to relevant survey results included deans, faculty learning and teaching associate deans, and course/subject area/program convenors. At a few institutions, some quantitative survey data was available to all staff, but qualitative student feedback was often restricted to educators involved in the unit and the head of school or other executives. Seven institutions provided students with access to survey results. At two institutions, all quantitative data was available to students as well as staff. At a further two institutions, summary quantitative data was available to students.

The amount of context and guidance on interpreting evaluation data varied. Several institutions included notes with survey results explaining that the data from student surveys should be triangulated with other sources of evaluation data. One participant said that their institution explained that the survey data ‘is a signpost’ and needed to be triangulated with other evaluation data and behaviour observations by the educators’ supervisor or peers.

Strategies for managing abusive or discriminatory comments

Procedures for managing abusive or discriminatory comments varied greatly across the sector, and in most cases were not formalised anywhere in policy or protocols. Twelve universities prescreen qualitative student feedback to identify abusive or discriminatory comments. The most common approach involves a dictionary-based profanity filter (often embedded in survey software) or a filter that recognises key phrases, with some manual checking by evaluation staff. Procedures involved dictionary checking for comments containing keywords relating to bias, suicidal ideation, violence, or issues not connected to learning and teaching, such as dress or appearance. Manual checking of a sample of comments was used by some institutions, for example, ‘someone [from the evaluations team] … goes through the comments and deletes or de-identifies the comments’, although the resource-intensive nature of manual checking was noted. Educators and faculty leaders were usually able to request removal of unacceptable comments, and recommendations for comment removal were considered by senior evaluations/learning and teaching managers or faculty leaders. One approach was described as ‘Comments provided to DVC (A) [Deputy Vice Chancellor, Academic] for approval to either remove comment, whole response or submit for disciplinary action depending on severity’. Sixteen institutions did not screen comments before their release to academics, although several indicated that their institution was considering the issue. Some institutions relied on educators to identify malicious comments and request that they be removed from the record.

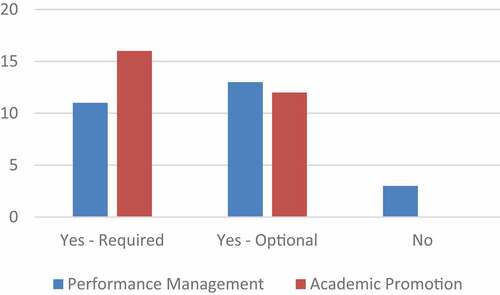

Institutional uses for evaluation data

Respondents indicated that use of evaluation data varied between faculties and managers both within and across universities, as shown in , with one stating ‘It is up to individual managers to review and use student evaluation data for … management of their staff’. Evaluation data was often used by academic promotion panels, with copies of SET survey reports required to be attached to relevant promotion applications. In several institutions, applicants were required to include a brief statement ‘showing reflection on and actions taken in relation to the evaluation data’ as part of a promotion application.

Evaluation data was also frequently used as a starting point in performance discussions between academics and their supervisor, although respondents noted that in the case of performance discussions, unlike recruitment and promotion processes, a detailed discussion of the context often occurs. For example, one participant commented that ‘Evaluation results can be used to supplement evidence of good teaching practice for performance management’.

In some cases, evaluation data, in particular quantitative SET data, were used as key performance indicators. In one institution, two-year means of SET scores were ‘used as part of the criteria for classification under our teaching quality standards framework’.

Evaluation data were also used in quality assurance processes, with some following a tiered approach to intervene where issues are identified:

[University x uses] a metric of student satisfaction from student evaluations and student success in the unit, which then provides a traffic light system—so low student satisfaction and low success rate is red lighted. Schools are sent a centrally generated report and have to work with the academic on strategies for improvement, and then report on these strategies (and in the future on their effectiveness) to a central university wide teaching quality committee.

A similar ‘traffic light’ approach was adopted by other institutions, where those subjects or course/degree programs receiving below a minimum threshold value for quantitative scores (mean or percentage agree) or student comments raising concerns were reported on and investigated in more detail. Some institutions commented that excellent SET response rates or extremely positive results were recognised at the institution, faculty, or school level.

Some institutions commented on the use of evaluation data in regular reflection and course review:

Course Coordinators are required to complete a report reflecting on the course evaluation and other sources of data to critically reflect on the course. The educational judgements and rationale provided in this report can be used as evidence for incremental curriculum renewal, inform purposeful academic decision making at the course, program, and school level, and provide systematic evidence for professional and program accreditation and review. A process is being implemented whereby actions for improvement will be made available for student review. Further a report on the aggregated quantitative results is made available to a standing committee of the Academic Board for the purpose of policy development, identifying priorities for funding and support and developing strategies for learning and teaching.

Overview of evaluation practice

provides a snapshot of the Australian and New Zealand higher education evaluation landscape by summarising the results of this study.

Discussion

Current practice

This study provides insights into the evaluation policy and practices of 29 of the 47 publicly funded Australian and New Zealand universities/higher education institutions. Our own experience in conducting an in-depth evaluation review showed the difficulties in obtaining information about current policy and effective practice in learning and teaching evaluation. In contrast to studies that focus on one aspect of evaluation practice (e.g., survey timing or the use of incentives), this research provides an overview of evaluation frameworks and practices at 29 universities (see ). The study will inform higher education evaluation strategies and add to knowledge of evaluation practice from an institutional perspective.

The divergence in strategic intent of evaluation was notable, with more than half of respondents reporting that the aim of their learning and teaching evaluation was to ascertain overall student satisfaction with the learning experience. This narrow stated intent disguises the multiple ways in which evaluation data are used at the institutional level and does not fully reflect the place of student evaluation feedback in national and institutional quality enhancement and assurance regimes. Our findings point to the importance of acknowledging that evaluation strategies need to be understood as more nuanced to balance the needs of student avenues for meaningful voice, academics’ need for feedback on their teaching, and the institutional imperative to assure the quality of learning and teaching (Bedggood & Donovan, Citation2012; Darwin, Citation2017).

The fact that all respondent universities use centrally deployed student evaluation of teaching surveys is unsurprising, given that all Australian universities do so and it is the dominant form of evaluation globally (Cunningham-Nelson, Baktashmotlagh, & Boles, Citation2019). Given the known importance of triangulating evaluation data to provide a fuller picture of teaching (Berk, Citation2018), it is disappointing to find that only one-third of our sample (13 institutions) used other evaluation methods, such as peer review or peer observation of teaching, or small group student feedback methods. It is clear that more should be done, including more scholarly case studies of successful nonsurvey approaches.

The focus of surveys – subject, teaching, or whole course or degree program – differed. While the vast majority evaluated teaching, only about half evaluated the subject or curriculum. This has the potential to undermine educators’ confidence in evaluation processes, if student feedback indicates difficulties distinguishing teaching and nonteaching aspects such as curriculum, learning systems, or even university support services and facilities in their responses.

More than half of respondents allowed academics to add or customise survey questions to focus on areas of teaching innovation or concern. This is likely to encourage educators to be more engaged in reflecting on and considering student feedback (Ulker, Citation2021).

Evaluation technology to host and deploy surveys and facilitate analysis and reporting represents a significant investment for universities (Marks & Al-Ali, Citation2018). However, with new technology companies engaged in generic customer experience management now targeting the higher education sector, it is important for higher education decision-makers to be aware of the opportunities and limitations of different providers and approaches, particularly those not tailored for the higher education environment.

Low student survey response rates are often claimed as evidence of low reliability and framed as a reason that SETs should be abandoned (Nulty, Citation2008). The results presented here indicate that many universities in the sector may be struggling with response rates and that this is a concern given the reliance on student evaluation surveys for quality enhancement and assurance. The influence of incentives in the literature is contested, with some research showing their use increases response rates (Goodman, Anson, & Belcheir, Citation2015). This is supported by the results from one institution where the response rate decreased following the removal of survey incentives. However, there is evidence that other factors such as closing the loop have more impact on response rate (Hoel & Dahl, Citation2019). It is therefore important for institutions to maximise response rates to the extent possible, by optimising dissemination, communication, and promotion activities, and considering the use of incentives (Young, Joines, Standish, & Gallagher, Citation2019).

Not all institutional approaches are equal

Not all institutional approaches to SETS are equal, despite this often being an assumption in the literature. Our findings point to broad diversity of policy and practice, with pockets of good practice, for example, in relation to sophisticated comment-screening approaches using machine learning (Cunningham, Laundon, Cathcart, Bashar, & Nayak, Citation2022). It is this diversity, including examples of weak or absent institutional policy and procedures, which calls into question the validity and reliability of evaluation strategies and feeds criticisms and calls to abandon student evaluations from researchers and industry groups, including trade unions (National Tertiary Education Union, Citation2018). The study also revealed significant underuse of analysis to provide insights. For example, many institutions ignore or fail to analyse qualitative comments, despite qualitative student feedback having more of an effect on teaching improvements than quantitative evaluation results (Shah & Pabel, Citation2020). Furthermore, despite the growing concern about the impact of abusive or discriminatory student evaluation feedback on staff psychosocial wellbeing and/or academic careers (Cunningham, Laundon, Cathcart, Bashar, & Nayak, Citation2022), a surprisingly low number of institutions have implemented screening processes. Inadequate technology solutions and a lack of sharing of good practice are other deficits identified.

However, the study revealed a broad awareness that current practice had limitations and showed that university staff knew that improvements could be made. Several indicated that their institution was doing the best it could to make incremental improvements within an environment of constrained resources.

Recognition is widespread that student evaluations have limitations in informing improvements to teaching quality, and previous research has highlighted the importance of training and guidance for all parties involved in evaluation to ensure consistency and fairness in the way results are interpreted and used institutionally (Cherry, Grasse, Kapla, & Hamel, Citation2017).

Research implications, limitations, and future research

This research provides important insights for higher education leaders and educators in relation to current learning and teaching evaluation practices.

The effects of, and opportunities presented by, technological advances are evident in the findings relating to institutions adopting new survey platforms and technology-assisted evaluation data analysis and screening of student comments. While some of these approaches are discussed in the recent literature (Cunningham, Laundon, Cathcart, Bashar, & Nayak, Citation2022; Cunningham-Nelson, Baktashmotlagh, & Boles, Citation2019; Cunningham-Nelson, Laundon, & Cathcart, Citation2021; Liu, Feng, & Wang, Citation2022), more research is needed to explore how these approaches can be implemented in different higher education contexts (e.g., by universities with fewer resources).

The recruitment methods used for this study (email invitation to evaluation managers and advertisement via the electronic newsletter of an Australasian learning and teaching leaders council) poses the risk of response bias. Although 32 respondents held specific evaluation roles, the other seven may have had more limited knowledge of evaluation strategy, policy and practice. A further limitation of the study was that the scope did not allow for consideration of whether student evaluation of teaching surveys is a suitable method to evaluate educational quality. Further research is needed to distinguish between overall student satisfaction, and satisfaction with the quality of the learning experience. Future research may also usefully investigate the effectiveness of survey administration practices, such as the optimal number of survey questions, the influence of survey timing, and whether surveys should be deployed every time a course runs. A recent relational map identifying relationships between stakeholders and components of SET in Australian higher education offers a promising tool for analysis of specific dimensions of evaluation policy and practice (Lloyd & Wright-Brough, Citation2022).

Conclusion

This research highlights what is common practice within the sector. The study participants acknowledged the constraints of existing software, resources and time in limiting institutions’ ability to identify and implement optimal evaluation practices. Where there is literature available, we have compared sector practice against effective practice. However, it is clear from the identified gaps that there is a need for further research into best practice from an operational perspective.

The explosion of critical research shows that teaching evaluation is of intense interest to academics, which is unsurprising given its (often mandatory) use in academic recruitment, promotion, and performance management. Its embeddedness in institutional quality assurance and academic management processes ensures that student evaluations of teaching are likely to remain a key feature of university policy and practice. It is therefore essential for institutions to reflect on the wider context for evaluation strategies and consider how they can adopt fair, consistent, and defensible evaluation practices.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the collegial contribution of university evaluation managers and staff members who participated in this study. We also acknowledge the work of the QUT Review of Units and Teaching Evaluation Steering Committee and the support of QUT Academy of Learning and Teaching staff members.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alderman, L., Towers, S., & Bannah, S. (2012). Student feedback systems in higher education: A focused literature review and environmental scan. Quality in Higher Education, 18(3), 261–280. doi:10.1080/13538322.2012.730714

- Alhija, F.N.-A., & Fresko, B. (2009). Student evaluation of instruction: What can be learned from students’ written comments? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 35(1), 37–44. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2009.01.002

- Australian Government. (2020, November 18). Upholding quality: Quality indicators for learning and teaching. https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/upholding-quality-quality-indicators-learning-and-teaching

- Bedggood, R.E., & Donovan, J.D. (2012). University performance evaluations: What are we really measuring? Studies in Higher Education, 37(7), 825–842. doi:10.1080/03075079.2010.549221

- Berk, R.A. (2018). Beyond student ratings: Fourteen other sources of evidence to evaluate teaching. In E. Roger & H. Elaine (Eds.), Handbook of quality assurance for university teaching (pp. 317–344). London: Routledge.

- Bjork, R.A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 417–444. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823

- Boring, A. (2017). Gender biases in student evaluations of teaching. Journal of Public Economics, 145, 27–41. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2016.11.006

- Brookfield, S.D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cadez, S., Dimovski, V., & Zaman Groff, M. (2017). Research, teaching and performance evaluation in academia: The salience of quality. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1455–1473. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1104659

- Carpenter, S.K., Witherby, A.E., & Tauber, S.K. (2020). On students’(mis) judgments of learning and teaching effectiveness. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(2), 137–151. doi:10.1016/j.jarmac.2019.12.009

- Cheng, M. (2009). Academics’ professionalism and quality mechanisms: Challenges and tensions. Quality in Higher Education, 15(3), 193–205. doi:10.1080/13538320903343008

- Cherry, B.D., Grasse, N., Kapla, D., & Hamel, B. (2017). Analysis of academic administrators’ attitudes: Annual evaluations and factors that improve teaching. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(3), 296–306. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2017.1298201

- Cunningham, S., Laundon, M., Cathcart, A., Bashar, M.A., & Nayak, R. (2022). First, do no harm: Automated detection of abusive comments in student evaluation of teaching surveys. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–13. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2081668

- Cunningham-Nelson, S., Baktashmotlagh, M., & Boles, W. (2019). Visualizing student opinion through text analysis. IEEE Transactions on Education, 62(4), 305–311. doi:10.1109/TE.2019.2924385

- Cunningham-Nelson, S., Laundon, M., & Cathcart, A. (2021). Beyond satisfaction scores: Visualising student comments for whole-of-course evaluation. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(5), 685–700. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1805409

- Darwin, S. (2017). What contemporary work are student ratings actually doing in higher education? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.08.002

- Dunrong, B., & Fan, M. (2009). On student evaluation of teaching and improvement of the teaching quality assurance system at higher education institutions. Chinese Education & Society, 42(2), 100–115. doi:10.2753/CED1061-1932420212

- Estelami, H. (2015). The effects of survey timing on student evaluation of teaching measures obtained using online surveys. Journal of Marketing Education, 37(1), 54–64. doi:10.1177/0273475314552324

- Freeman, B. (2014). Benchmarking Australian and New Zealand university meta-policy in an increasingly regulated tertiary environment. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 36(1), 74–87. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2013.861050

- Goodman, J., Anson, R., & Belcheir, M. (2015). The effect of incentives and other instructor-driven strategies to increase online student evaluation response rates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(7), 958–970. doi:10.1080/02602938.2014.960364

- Hammonds, F., Mariano, G.J., Ammons, G., & Chambers, S. (2017). Student evaluations of teaching: Improving teaching quality in higher education. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 21(1), 26–33. doi:10.1080/13603108.2016.1227388

- Harrison, R., Meyer, L., Rawstorne, P., Razee, H., Chitkara, U., Mears, S., & Balasooriya, C. (2022). Evaluating and enhancing quality in higher education teaching practice: A meta- review. Studies in Higher Education, 47(1), 80–96. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1730315

- Heffernan, T. (2022a). Abusive comments in student evaluations of courses and teaching: The attacks women and marginalised academics endure. Higher Education, 85(1), 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10734-022-00831-x

- Heffernan, T. (2022b). Sexism, racism, prejudice, and bias: A literature review and synthesis of research surrounding student evaluations of courses and teaching. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(1), 144–154. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1888075

- He, J., & Freeman, L.A. (2021). Can we trust teaching evaluations when response rates are not high? Implications from a monte carlo simulation. Studies in Higher Education, 46(9), 1934–1948. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1711046

- Hessler, M., Pöpping, D.M., Hollstein, H., Ohlenburg, H., Arnemann, P.H., Massoth, C., Seidel, L.M., Zarbock, A., & Wenk, M. (2018). Availability of cookies during an academic course session affects evaluation of teaching. Medical Education, 52(10), 1064–1072. doi:10.1111/medu.13627

- Hoel, A., & Dahl, T.I. (2019). Why bother? Student motivation to participate in student evaluations of teaching. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(3), 361–378. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1511969

- Kreitzer, R.J., & Sweet-Cushman, J. (2022). Evaluating student evaluations of teaching: A review of measurement and equity bias in SETs and recommendations for ethical reform. Journal of Academic Ethics, 20(1), 73–84. doi:10.1007/s10805-021-09400-w

- Liu, C., Feng, Y., & Wang, Y. (2022). An innovative evaluation method for undergraduate education: An approach based on BP neural network and stress testing. Studies in Higher Education, 47(1), 212–228. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1739013

- Lizzio, A., Wilson, K., & Simons, R. (2002). University students’ perceptions of the learning environment and academic outcomes: Implications for theory and practice. Studies in Higher Education, 27(1), 27–52. doi:10.1080/03075070120099359

- Lloyd, M., & Wright-Brough, F. (2022). Setting out SET: A situational mapping of student evaluation of teaching in Australian higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2022.2130169

- MacNell, L., Driscoll, A., & Hunt, A.N. (2015). What’s in a name: Exposing gender bias in student ratings of teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 40(4), 291–303. doi:10.1007/s10755-014-9313-4

- Marks, A., & Al-Ali, M. (2018). Higher education analytics: New trends in program assessments. Trends and Advances in Information Systems and Technologies, 745, 722–731.

- Marsh, H.W. (1987). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: Research findings, methodological issues, and directions for future research. International Journal of Educational Research, 11(3), 253–388. doi:10.1016/0883-0355(87)90001-2

- Matear, S. (2020). Cycle 6 audit framework. Academic Quality Agency for New Zealand Universities. https://www.aqa.ac.nz/cycle6

- McCubbin, A., Hammer, S., & Ayriss, P. (2022). Learning and teaching benchmarking in Australian universities: The current state of play. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 44(1), 3–20. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2021.1934244

- Miller, A.H. (1984). The evaluation of university courses. Studies in Higher Education, 9(1), 1–15. doi:10.1080/03075078412331378873

- Mitchell, K.M., & Martin, J. (2018). Gender bias in student evaluations. PS: Political Science & Politics, 51(3), 648–652. doi:10.1017/S104909651800001X

- National Tertiary Education Union. (2018). Staff experience of student evaluation of teaching and subjects/units. https://www.nteu.org.au/library/download/id/9058

- Nulty, D.D. (2008). The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(3), 301–314. doi:10.1080/02602930701293231

- Ory, J.C., & Ryan, K. (2001). How do student ratings measure up to a new validity framework? New Directions for Institutional Research, 2001(109), 27–44. doi:10.1002/ir.2

- Penny, A.R. (2003). Changing the agenda for research into students’ views about university teaching: Four shortcomings of SRT research. Teaching in Higher Education, 8(3), 399–411. doi:10.1080/13562510309396

- Santhanam, E., Lynch, B., Jones, J., & Davis, J. (2021). From anonymous student feedback to impactful strategies for institutional direction. In E. Zaitseva, B. Tucker, & E. Santhanam (Eds.), Analysing student feedback in higher education: Using text-mining to interpret the student voice (pp. 167–179). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003138785-15

- Shah, M., & Pabel, A. (2020). Making the student voice count: Using qualitative student feedback to enhance the student experience. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 12(2), 194–209. doi:10.1108/JARHE-02-2019-0030

- Smith, C. (2008). Building effectiveness in teaching through targeted evaluation and response: Connecting evaluation to teaching improvement in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5), 517–533. doi:10.1080/02602930701698942

- Social Research Centre. (2022). 2021 Student experience survey national report. https://www.qilt.edu.au/surveys/student-experience-survey-/ses/#report

- Spooren, P., Brockx, B., & Mortelmans, D. (2013). On the validity of student evaluation of teaching: The state of the art. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 598–642. doi:10.3102/0034654313496870

- Spooren, P., Vandermoere, F., Vanderstraeten, R., & Pepermans, K. (2017). Exploring high impact scholarship in research on student’s evaluation of teaching (SET). Educational Research Review, 22, 129–141. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2017.09.001

- Stein, S.J., Goodchild, A., Moskal, A., Terry, S., & McDonald, J. (2021). Student perceptions of student evaluations: Enabling student voice and meaningful engagement. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(6), 837–851. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1824266

- Ulker, N. (2021). How can student evaluations lead to improvement of teaching quality? A cross-national analysis. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 26(1), 19–37. doi:10.1080/13596748.2021.1873406

- Wang, G., & Williamson, A. (2022). Course evaluation scores: Valid measures for teaching effectiveness or rewards for lenient grading? Teaching in Higher Education, 27(3), 297–318. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1722992

- Whitworth, J.E., Price, B.A., & Randall, C.H. (2002). Factors that affect college of business student opinion of teaching and learning. Journal of Education for Business, 77(5), 282–289. doi:10.1080/08832320209599677

- Wright, S.L., & Jenkins-Guarnieri, M.A. (2012). Student evaluations of teaching: Combining the meta-analyses and demonstrating further evidence for effective use. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(6), 683–699. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.563279

- Youmans, R.J., & Jee, B.D. (2007). Fudging the numbers: Distributing chocolate influences student evaluations of an undergraduate course. Teaching of Psychology, 34(4), 245–247. doi:10.1080/00986280701700318

- Young, K., Joines, J., Standish, T., & Gallagher, V. (2019). Student evaluations of teaching: The impact of faculty procedures on response rates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(1), 37–49. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1467878