ABSTRACT

Using Multilevel Job Demand-Resources theory, this research explores how crisis influenced perceptions about academic work engagement at individual, team, and organisational levels. The COVID-19 crisis led universities to make significant changes in response to health and fiscal impacts. Changes included restructuring, job shedding, and pivoting to online teaching which affected psychological well-being, and myriad affective outcomes. Thirty-six participants discussed COVID-19, changes in their university, effects on their work, and coping strategies. At the organisational level, participants consider their universities, specifically university leaders and leadership practices, afford limited resources to support responses to crisis and change leading to excessive job demands, negative health outcomes, and low motivation. At the team level, strong team relationships and supportive leaders were identified as important job resources to mitigate against some demands. At the individual level both coping and self-undermining practices were identified to manage demands. The implications on academic work engagement are elaborated.

Introduction: The COVID-19 crisis response and academic employee outcomes

Universities have engaged in significant strategic and operational restructuring in response to the COVID-19 crisis. As widely reported across the media, universities engaged in job shedding as a revenue saving activity, for example. Drawing on Australian Government Department of Education (DoE, Citation2022) staff data, Hare (Citation2022) reported in the Australian Financial Review the loss of 27,000 university jobs in 2020. This was the largest decline in staff numbers in Australian universities since 1989 (see, Norton, Citation2022 for an analysis of Australian higher education job losses). Job shedding, together with mergers and organisational restructuring (Slade et al., Citation2022) which is commonplace across the Australian higher education sector, have profound effects on and implications for academic staff such as decreased job security, increased workloads, and increased job dissatisfaction (Littleton & Stanford, Citation2021). In a work environment that can only be characterised as unstable and unpredictable, with universities continuing to reconfigure their operations in the aftermath of COVID-19, the academic workforce is experiencing instability, unpredictability, and complexity requiring teams and individuals to adapt to new (and more) job demands (Van de Ross et al., Citation2022).

Organisational change research observes that instability and consistently changing conditions negatively affect employee engagement, commonly defined as, ‘a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind’ (Bailey et al., Citation2017, p. 34). This is no less true for academic staff (Littleton & Stanford, Citation2021). Research exploring academic engagement and psychosocial safety in the context of crisis and change, is, however, relatively callow. Whilst the concept of engagement (personal, job, work task) is not new (c.f., Macey & Schneider, Citation2008), the concept of academic engagement encompassing psychosocial safety is (see León, Citation2021). This is also an area of research that has received limited attention in higher education studies. Nonetheless, León (Citation2021) avers that exploring academic staff engagement is highly relevant for university decision makers because of its impact on teaching quality, the student experience, and academic job satisfaction. Specifically understanding how academic engagement, and by extension psychosocial safety, is influenced by job demands and resources would prove useful in the development of policies and institutional practices that foster and maintain engagement and mitigate academic burnout and attrition.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified many of the conditions contributing to the degradation of engagement among university employees and what brings academic staff joy at and in their work as evidenced by recent research (Whitsed & Girardi, Citation2022 Whitsed et al., Citation2024). The COVID-19 crisis exacerbated long-standing factors that contribute to occupational stress, burnout, and psychosocial harms. For several decades a consistent finding of studies on workplace satisfaction and academic stress within Anglophone universities has been the negative views of academics of university governance which tie these perceptions to the rise of the neoliberal university and new public managerialism (Bleiklie, Citation1998; Winefield et al., Citation2003; Wray & Kinman, Citation2022). For example, as Bottrell and Manathunga (Citation2019) observe, prior to the COVID-19 crisis, Australian universities had begun to be transformed by neoliberal ideologies and management practices. Consequently, the conditions academic staff once found satisfying were being eroded along with conditions that supported positive wellbeing. Within this context, academic staff had to negotiate the ‘neo-liberal reform of universities, primarily centred on managerialism, [and] the top-down, hierarchical structure of governance and decision-making’ (Bottrell & Manathunga, Citation2019, p. 5). Moreover, as Bottrell and Manathunga (Citation2019) note, academic staff were also increasingly ‘readily discarded’ in restructures argued as necessary to achieve a university’s strategic goals within narratives of budgetary constraints and the necessity of maintaining budget surpluses. Within this context, academic staff became perceived as highly disposable and largely dehumanised resources.

As observed in the Australian Universities Accord Interim Report (O’Kane, Citation2023), factors that contribute to psychosocial hazards in the academic workplace are widely reported (e.g., Lee et al., Citation2020) and these can influence academics’ levels of commitment, satisfaction, and engagement (Mudrak et al., Citation2017). Consistent across this research is the increase in job demands that have not been met by a commensurate change in opportunities for job control and social support – job resources – which have been shown to increase engagement and reduce the risk of burnout (Wray & Kinman, Citation2022).

To address how the nexus of job demands-resources manifests within academic work and explore perceptions of engagement and wellbeing, this research delved into the lived experience of academics influenced by crisis, complexity, and change within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This research therefore utilised qualitative interviews to explore participants’ perceptions of their professional environment, how they navigate this complex and demanding environment, and how they and their colleague’s cope.

The following elaborates key dimensions of the Job Demand-Resources theory (JD-R theory) as a hermeneutic lens to explore these academic staff perceptions.

Job demands-resources theory and academic staff engagement

JD-R theory has been widely applied to explain organisational processes that influence the health, well-being, and performance (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2023), and is a dominant framework for exploring employee engagement (Kwon & Kim, Citation2020; Mudrak et al., Citation2017). It has also been used to examine the work engagement of academics in range of higher education contexts (c.f., Rothmann & Jordaan, Citation2006; Xu, Citation2019). Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2018) define job demands as ‘aspects of work that cost energy’ (p. 2) and require sustained effort (e.g., work pressure, cognitive demands). Job demands are energy consuming and encompass phenomena such as challenged demands (role conflict, workload, complex tasks), and hindrance demands (conflicts, work-home interference, and job insecurity).

Job resources are ‘those physical, psychological, social, or organisational aspects of the job that are functional in achieving work goals, reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, or stimulate personal growth, learning, and development’ (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017, p. 274). Because they fulfil the needs for ‘relatedness, competence, and autonomy’ job resources are intrinsically motivating. They are also extrinsically motivating because of their potential to help attainment work-related goals (Bakker & Albrecht, Citation2018). Job resources are predictors of positive work outcomes and are aspects of the job that promote work goal achievement, stimulate personal growth, learning and development, reductions in job demands, and psychological costs. In other words, they ‘generate motivation’, and ‘buffer the effects of job demands on employee well-being and performance’ (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2023, p. 7).

JD-R theory has been applied across a range of organisational contexts to explore, understand, and predict engagement and engagement-related outcomes (including burnout); however, its utility in academic environments is less well understood. Of the studies specifically applying JD-R theory to university academic experiences, the outcomes have focussed on identifying a range of demands and resources that influence engagement.

For instance, Mudrak et al. (Citation2017) research in public universities in the Czech Republic utilises JD-R theory to explore ‘the relationship between the academic work environment and academic well-being’ (p. 362), including engagement. According to their data, job resources (e.g., influences over work, and support from supervisors) correlated positively with academic work engagement and job satisfaction, while job demands (e.g., work-family conflict, job insecurity) were associated with stress, supporting the propositions of the JD-R theory. Mudrak et al. (Citation2017) posited that positive social characteristics of the academic workplaces, which are crucial determinants of academics’ job satisfaction, include: the university atmosphere, a sense of community, relationships with colleagues, the effectiveness of administration and technical/administrative support, the quality of academic leadership and staff autonomy and influence over their work. Salient drivers of job dissatisfaction, according to Mudrak et al. (Citation2017, p. 327) include perceptions of controlling leadership, poor managerial culture, high workloads, job insecurity, and work-family conflicts. This study implies that job demands, and job resources occur at multiple levels – from individual to organisational – and therefore activities that influence the management of demands and resources are similarly multilevel, although this was not specifically tested.

Other research using the JD-R theory focussed on individual outcomes. For instance, Han et al. (Citation2020) examined the ‘applicability’ of the JD-R theory to the higher education context in China and ‘examine[d] the mediation effect of personal resources within the model’ (p. 1772). Han et al. (Citation2020) reported, a ‘significant negative relationship between job resources and emotional exhaustion in university teachers, indicating that under demanding work conditions, high levels of job resources may alleviate teachers’ work strain. The results also indicate that a lack of job resources available to deal with job demands may lead to emotional exhaustion’ (p. 1781). Similarly, Sarwar et al. (Citation2021) in the Pakistani higher education context employed JD-R theory to examine academic satisfaction with work-family balance. They reported that, ‘academic workload, emotional stress, and cognitive pressures’ decrease academic’s ability to ‘integrate multiple role demands causing inter-role strain’ (p. 13). Inversely, job resources like ‘social support from supervisors and colleagues, control over job tasks and working time and sufficient development opportunities’, when present increases faculties ‘abilities to manage their multi-domain role and lead to a positive evaluation of domain balance’ (Sarwar et al., p. 13). The outcomes of this study point to a combination of self-directed individual strategies and support from others as needed to balance demands and resources. The role of the institution, however, is absent from discussions.

While more recent studies have emerged exploring the experience of academic during the COVID-19 pandemic using the JD-R theory (e.g., Joseph & Rao, Citation2022), few have specifically explored the multilevel nature of job demand-resources experienced during crisis, and their interactive effects on academic perceptions about work, particularly within the Australian context. This study offers a novel approach and addresses this current limitation by applying a multilevel JD-R theory to explore the perceptions of academic staff in a context of crisis and change.

Multilevel job demands-resources

Reflecting on the past ten years of JD-R theory and research, Bakker et al. (Citation2023) consider multilevel JD-R to be an ‘exciting’, ‘important’, and ‘major innovation’ in the theoretical development and application of JD-R this decade (pp. 36–37). As we elaborate, consistent with Bakker et al. (Citation2023), multilevel JD-R acknowledges individual employees’ work nested in teams, which are, in turn, nested in organisations. This is significant because as Bakker et al. (Citation2023) highlight, individuals who work in teams ‘share their perceptions of job demands and resources’ and influence each other’s ‘affect, cognitions, and behaviours through modelling and emotional contagion’ through their ‘interdependence and frequent interactions’ (p. 39). Moreover, multilevel JD-R references factors beyond work design and includes, inter alia, the broader psychosocial safety climate (Bakker et al., Citation2023, p. 43).

We draw on Bakker et al. (Citation2023), Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2018) multilevel JD-R theory, Demerouti and Bakker’s (Citation2023) extended JD-R model, and Lee et al.’s (Citation2020) taxonomy to explain how in a crisis job demands and resources do not exist in isolation, but at multiple levels (see, Park & Park, Citation2023) and influence affective and performance related outcomes via either the activation of a motivational process or a health impairment process.

Job resources support employees to develop themselves and deal with demands (Demerouti and Bakker (Citation2023). Job resources initiate motivational processes that increase affective employee outcomes including engagement and performance (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2023). Coping styles and regulatory strategies, and access to a range of resources (e.g., family, and social support) can positively influence motivation and job performance by moderating the negative effects of job demands. Motivated employees are more likely to use job crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001) behaviours, to influence levels of job and personal resources and thereby further increase levels of motivation. Job crafting has become a major area of study (Lee & Lee, Citation2018), and indeed several recent studies have examined job crafting in relation to academics (e.g., Arachie et al., Citation2021). Job crafting is understood to constitute a cognitive process wherein employees try to adjust their view of work in such a way that it becomes more meaningful (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2018). Tims and Bakker (Citation2010) explain this means, employees ‘can change how work is conceptualised and carried out … , how often, and with whom they interact (e.g., changing relationship boundaries) and how they cognitively ascribe meaning and significance to their work’ (p. 3). Job crafting may result in an increase in resources (personal and job), and positive outcomes such as, job satisfaction, work engagement, resilience, thriving and organisational commitment (Tims & Bakker, Citation2010). In times of crisis however, job crafting is insufficient as a coping mechanism and the access to job resources at individual, team and institutional levels to counter job demands becomes paramount (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2023).

The health impairment process (e.g., stress, anxiety, depression etc.) is initiated when demands are high and corresponding resources are low. In a crisis, employees experiencing job strain (e.g., chronic exhaustion, burnout) are more likely to demonstrate self-undermining behaviours that inhibit or undermine performance because they lack the energy/resources to redress job demands (Bakker & Wang, Citation2020). Bakker and Wang (Citation2020) characterise self-undermining behaviours as, ‘a set of undesirable reactive behaviours in the workplace without a functional purpose that undermines adequate functioning’ with the potential to ‘fuel a vicious cycle of high job demands’ (p. 242). Self-undermining is considered a stress response that inhibits an individual’s capacity to engage in self-regulation and coping strategies. Moreover, employees who exhibit self-undermining behaviours tend to lack self-regulation, communicate poorly, create conflicts, and/or make mistakes. Self-undermining behaviours are positively correlated with high levels of stress, anxiety, exhaustion, burnout, and related psychosocial conditions (Bakker & Wang, Citation2020). Self-undermining behaviours result in a loss-cycle-feedback-loop of increased levels of job demands which fuels job strain (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2023). In times of crisis, like the COVID-19 pandemic, demands experienced by individuals became interwoven (e.g., family/home and job demands). The balancing of these various life domains (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2023) relies on the availability of resources at various levels.

At the organisational level, resources include positive organisational culture; HR practices and climate; psychosocial safety climate; employee voice; stability, job security, and organisational trust; and senior leadership quality and authenticity. The degree to which these resources are perceived to be available asserts an influence on how team/group resources and individual/personal level resources are perceived. Team/group level resources include interactions, interpersonal relationships with supervisors and co-workers, support in work-role tasks, team climate, leaders’ behaviours, team well-being and performance. Individual or personal level resources include job-crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001), an individual’s capacity (both psychological and social) to manage job demands and access to job resources, individual well-being and performance.

Team/group and individual/personal levels are influenced by the organisational level, which in turn can be influenced by the team/group and individual/personal level. For instance, a leader’s behaviour can influence team and individual JD-Rs. Team JD-R can influence individual JD-R and individual well-being and performance. An individual’s personal resources (attributes, self-efficacy) and job demands (e.g., workaholism, performance expectations) and job resources (e.g., resilience, self-efficacy) are salient determinants of positive job performance.

A goal of this research is to understand how academics experience crisis and change across multiple levels of job resources and demands. Understanding the interaction effects between the three levels can prepare management to better navigate the complexity, manage change, and prepare for future crises.

Research methods

We adopted a qualitative design to explore how academic staff experience their work environment, and job demands and resources during a time of crisis and change. To create data, the project utilised qualitative interviewing (Kvale, Citation2007; Patton, Citation2002). The sampling strategy was purposeful, together with snowballing to recruit participants across all levels of academic appointment (A-E) and disciplines from five universities in Western Australia (Curtin University, Edith Cowan University, Murdoch University, the University of Notre Dame, and the University of Western Australia). The project was approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2021–0059) prior to the collection of interview data. We interviewed 36 academic staff over 12 months from the end of 2020 to late 2021. Qualitative interviews were one-to-one, in-depth, and semi-structured and ranged from 40–90 minutes in duration. Participants were prompted to discuss their:

work environment and what they perceived the mood, workplace culture, leadership, and governance to be like in their universities broadly and in their immediate workplaces (e.g., Schools, Disciplines) and what they say to others outside of their university when discussing work with colleagues, friends and/or family;

perceptions of their leaders’ governance, decisions, and actions as they responded to crisis – in this case the COVID-19 pandemic; and,

organisational changes in their institutions and how these impacted them and their colleagues, the biggest challenges they and their colleagues are confronting, and how they and their colleagues are feeling, cope and make sense of these challenges.

Participants

The participants (n = 36) were assigned pseudonyms (e.g., P2, P3) in the order of the interviews. Participants were almost evenly divided between Business and Law disciplines (n = 12), Health Sciences (n = 11), and Humanities (n = 10); with fewer participants from Science and Engineering (n = 2) and a university central division (n = 1). Participants represented all levels of academic appointment: Lecturer, Level B (n = 13), Senior Lecturer, Level C (n = 4), Associate Professor, Level D (n = 9) and Professor, Level E (n = 7). Only one Associate Lecturer, Level A participated in the study. The sample also included participants who were in academic leadership roles including Deputy Head of School, Dean/Director of Teaching and Learning, Dean/Director of Research and Disciplines Leads (n = 9). Participants were almost equally divided according to gender with 48% nominating as female and 51% male. Most participants indicated that they were over 40 years of age (40–49 (7%) 50–59 (34%) and 60–69 (31%)). Eighty-five percent of participants had between 10 or more years of experience working in the university sector, with the rest of the participants having more than five years at the time of their interview.

Data analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim using the Otter.ai transcription platform (https://otter.ai/) and checked for accuracy by members of the research team. Each transcript was verified against the audio recordings and lightly edited for accuracy. Each transcript was read by the members of the research team and discussed to ensure overall understanding.

Following Gibbs (Citation2007), the transcripts were interrogated thematically which involved identifying, analysing, organising, and describing salient themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). This process involved initial inductive, line by line, open coding by the lead member of the research team. The codes were crossed checked by a second member of the research team and organised into broad categories and themes. This was followed by focused axial coding and categorising to identify emergent themes. Then the data was interrogated deductively employing theoretical/selective coding to explore the relationships between the categories that emerged out of the initial coding stages (Gibbs, Citation2007) and salient dimensions of JD-R theory. The data were not analysed comparatively given the uniformity of participants’ responses across the interviews.

The following sections elaborate the research findings, using the multilevel JD-R theory as a heuristic lens exploring academic perceptions.

Findings

Organisation level job demands-resources

Participants were asked to discuss the characteristics of their academic workplaces, including their immediate teams as well as the broader institution, as a context for their responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Day et al. (Citation2017) observed organisational change can result in higher levels of job stress, uncertainty, role ambiguity, increased workloads, burnout and lower employee health and well-being, which can be mitigated if employees are provided with appropriate job resources including good governance structures, supervisor support, job control, and autonomy – features that appeared lacking in participant responses.

For example, participants identified organisational change management (P14, P16, P34, P9, P8, P18), restructuring (P3, P33), school mergers (P4, P7, P8), new structures (P18, P20, P35), short-term strategies (P22), short-term savings measures (P18) and limited infrastructure support (P25) as characteristic of their universities’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Increasing levels of managerialism (P22), bureaucratic decision making, practices and processes (P9, P15, P33) and dysfunctional organisational leadership (P11); inefficient governance and management structures (P4), frequent organisational change (P4, P25), deteriorating workplace conditions due to restructures, (P13, P34) and centralisation of support services were identified as key drivers increasing workloads (P9, P16), and a general climate of distrust (P10, P18). This sentiment is reflected in the following comment,

So, we have a set of values [at my university]. A sentiment that I’ve heard a number of times from staff is that the university executive and the Faculty Executive are not living by those values. Not practicing what they preach in terms of those values. So, I think that has created a culture of distrust amongst staff. … I think there’s a growing sort of distance between senior management at the university and Faculty level and those staff at the coalface. (P10)

The following excerpt (P22) highlights the tensions associated with institutional cost cutting and job insecurity as a reduction in job resources and an increase in job demands (e.g., anxiety, insecurity), which further amplifies job demands as experienced and/or perceived by the most participants in this research.

I think job insecurity is probably the overwhelming anxiety for most people. Seeing so many people lose their job, including people who’ve been there for a long time, has made everybody feel insecure. So, what people are having to cope with is anxiety around their jobs, anxiety around their ability to do their job. (P22)

This sentiment was reflected across the interviews, with a significant number of participants reporting feelings of stress and anxiety (e.g., P4, P21, P16). For many, as P14 remarked, ‘stress levels have risen quite significantly’. As P18 observed, change management was associated with the creation of ‘a lot of psychological stress, anxiety and a demoralised staff’. With such increased ‘stress’ levels, the reliance on individual, team and institutional supports is expected to rise. The participants however did not suggest this was the case.

Participants reflected on their university’s management, governance and decisions over the year preceding their interview. Many responded positively (e.g., P2, P13) about the initial responses to COVID-19 but participants were cynical of senior leadership and their decisions during and after the COVID-19 crisis. For example, participants characterised their university leaders as ‘not being effective at communicating their vision’ (P18), being ‘disconnected’, (P8), ‘dysfunctional’ (P11), ‘lacking in accountability’ (P7), ‘disingenuous and lacking in transparency’ (P30), and duplicitous by using COVID ‘as a way to accelerate change’ (P25) and/or ‘push their own agenda’ (P14). P10 and P9, in the following extracts, highlight the lack of trust and cynicism participants expressed towards senior management when discussing the university’s response to COVID-19.

I felt that there was a change midway through the year. And the university saw that the crisis was actually going to provide an opportunity for them to implement some change and restructure under the guise of it being necessary because of the financial impact of COVID-19. I’m not sure. I’m not convinced that that was entirely the case. And that’s a sentiment I’ve heard from other staff as well. Which brings about a lack of trust in senior management. (P10)

… the senior executive board brought out it’s COVID-19 strategy. Which many of us saw as a very cynical move. Claiming that they needed to make cutbacks … I hear colleagues use the word toxic in relation to the atmosphere in the university. I’ve heard them talk about the university structures imploding. … I think there’s a sense of a senior management team that is out of touch. Doesn’t really care. Is vindictive. Generally, I think the feeling of the university is extremely negative. (P9)

Such reflections suggest that university leadership did not provide important details about the crisis and specifically crisis management, neither through explicit communication nor explicit behaviours. This left academic staff to construct their own meaning about the intentions of the interventions and suggests that communication is critical during crisis to reduce competing sense-making of actions.

Instability and leadership change, which P36 characterised as a ‘revolving door of senior leaders’, also contributed to the creation of anxiety among participants. As P15 explained, ‘the appointment of the new Vice Chancellor creates a degree of angst and anxiety because every new strategic leader arrives with his or her own agenda, you don’t know what [their] agenda is going to be…’

Like the sentiment about change management, when discussing university-level workplace culture, participants like P5 and P31 highlighted what they perceive to be a closed workplace culture not based on merit. The workplace culture is characterised as one wherein favouritism is shown to a clique of staff who are ‘looked after’ and supported in their careers, while the majority just ‘do the work’ (P31). The workplace culture is also characterised as ‘vindictive’, with some staff who challenge management and/or overtly push back being on management’s ‘target list’ (P5). P11 identified a range of phenomena including feelings of ‘powerlessness and concern’ among staff within their university, as management practices and the workplace culture have undermined goodwill and elicited feelings of exploitation and diminished pride in their university as a place to work as it transformed into ‘some kind of corporation gone wrong’. Similarly, P22 identified the transformation of their workplace culture from one of collegiality to ‘being very impersonal, very corporate’ as a major factor affecting morale and consequently academic work engagement. P22’s perception of the workplace culture is one of staff not being ‘cared about at all’ and management being ‘indifferent to them’, excluding them from consultation while pursuing their own agendas resulting in a ‘culture of anxiety’ and job insecurity which have been linked to psychological safety.

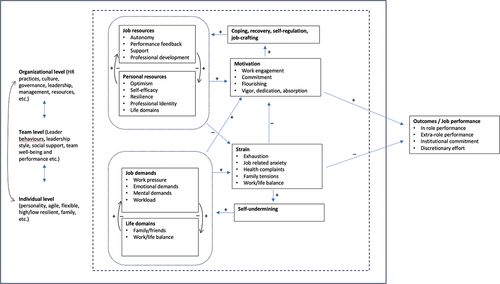

Most participants suggest that their institutional and work environments contribute to the creation of protracted and excessive job demands that exert considerable physical and psychological costs on academic staff, while constraining and/or limiting aspects of work that motivates them and/or their colleagues (see, Whitsed et al., Citation2024). The multilevel JD-R framework () provides for multilevel resources to mitigate against organisation-level job demands – such as those characteristics of any organisational change programme. Participants largely reported the absence of these resources at the organisational-level. However, they had positive responses when discussing the team level resources available to draw on to manage job demands, which is presented next.

Team level job demands-resources

Participants’ perceptions of job demands-resources at the team level stood in stark contrast to the institutional level. As indicated, participants characterised their university’s organisational climate as being fraught (P34), pervasive (P36), fragmented (P9, P34), uncertain (P6, P18, P30), oppressive (P5), toxic (P9, P19), deplorable (P7), imploding, vindictive (P9), illogical (P2), extremely negative, unjust (P10, P17), difficult (P11), exploitive (P15), unforgiving and highly punitive (P14) and therefore requiring sustained effort and considerable personal resources to negotiate professionally and personally. In contrast, at the School level (team) many participants ‘felt very well supported and very well informed by our leadership’ (P8). This is somewhat reflective of our research which suggests that during times of crisis, social support is greatly sought after (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2023).

Most participants spoke favourably of their immediate workplace (School, teaching team) as providing a positive and supportive culture. For example, P8 observed, ‘I feel like our school has always had a very supportive and inclusive culture. … We tend to get together to celebrate and to, in some ways, commiserate. We celebrate when people leave and we celebrate when people are having babies. And we fundraise and do things to support each other. It’s a reasonably open school in terms of people talking to you about what’s actually going on’. P33 observed, ‘I feel reasonably good about it, because I’ve got very good colleagues who I value and who are quite creative problem solvers and are supportive. And we don’t have any of those problems like harassment. It’s a good environment that is inclusive and tolerant. I’m aware that it’s not like that everywhere and it certainly hasn’t been that way everywhere I work. So [it’s] more about having immediately supportive colleagues that I value’. P21 remarked, ‘we’ve got a pretty good team in terms of collegiality’, and P31 observed ‘workplace culture generally, in my area, is very good between colleagues. At my level, I think there’s really there’s good interaction, and people are really happy to help each other’.

This theme of ‘social support’ has been shown to mitigate against worker disengagement through the activation of cognitive-based trust (Kumar & Sia, Citation2012) and thereby psychological safety which is a precursor to engagement (Frazier et al., Citation2017). This is presented in as a job resource and is especially in high demand during crisis periods. Collegiality, and positive and supportive teams (discipline/teaching) emerged as job resources that also interacted favourably with personal resources and linked to resilience, optimism, motivation, and sustained job performance. The resources at this team level influenced individual mechanisms for managing job demands. Other individual level resources are presented next.

Individual/personal level job demands-resources

Coping

Across the interviews participants discussed how they and their colleagues coped and/or buffered high work demands and low job resources. For example, P10 tries ‘to leave it at work’ ‘and spend time with their family’; however, he added, ‘that is not always possible’. P12 copes by focusing on their work and P19 by ‘trying to focus on those things that are sustaining and worthwhile’. Like P12 and P19, others cope by conserving resources and being pragmatic (P2) to maximise favourable effects of job characteristics. P4 copes by ‘putting one foot ahead of the next and keeping on walking and taking one day at a time’. P5 related they achieved ‘a relatively similar level of output from what I have in the past just through [personal] efficiencies’. P29 stated that they put their ‘head down and try and ignore the static, the stuff happening around me’. These actions are considered a form of self-regulation as depicted in .

P18 explained they were better able to cope by ‘focusing on the domains of work which are under your control’; ‘I personally think there’s an erosion of academic autonomy, that we’re more and more driven by metrics and bureaucracies in terms of reporting what we do. And those metrics, measurements of what you do and reporting on what you do are control mechanisms really’. As such, P18 reasoned it is ‘better to just focus on the things that I enjoy doing that are under my control’. Further, P18 observed colleagues ‘retreating to their own space’, and focusing on, ‘the things that they could control in terms of their work routines’.

This theme of control and agency emerged as a major one across the interviews, with some participants, like P2, feeling that irrespective of their circumstances and job demands they ‘feel in control’ and this enabled them to better maximise favourable effects of job characteristics through self-regulation and job crafting. Other coping strategies elaborated included ‘humour’ and ‘cracking jokes’ (P8, P16) and socialising with team members (P8, P10). P15 copes by ‘exercising regularly … to deal with stress’ and ‘allowing themselves quick get aways … to have a mental and physical break’. P16 observed colleagues made use of ‘various counselling services’ to cope with and manage stress. For others, time with family, ‘taking the dog for a walk or going fishing’ (P10) with family are part of their personal/home resources for coping.

While some participants coping strategies included physical and psychologically ‘withdrawing’ (P19) from the work environment, and ‘closing doors’ (P19); the majority adopted proactive coping strategies to deal with the effects of unfavourable job demands such as, job crafting, and recovery from work (Demerouti et al., Citation2019). Of some concern were the participants who were unable to engage any individual/personal level resources to mitigate against the demands of their work.

Self-undermining and loss cycles

P6 averred, like many participants, ‘I have no autonomy, I have no freedom to do what I want to do when it’s very stifling’. Responses to the interview questions ‘with everything going on across the HE sector, how are you feeling?’ and ‘how are the people you work with feeling?’ suggest participants do not feel they are able to fully exercise their agency and control within their jobs.

These low levels of personal and job resources and high levels of job strain manifested in reported feelings of job-related anxiety, uncertainty, fatigue, and emotional and physical exhaustion and ‘demotivation’ pointing to burnout. For example, participants reported feelings of being ‘stressed and overworked’ (P20) ‘unsupported’, ‘isolated’ (P6), ‘distressed’ (P34), ‘overwhelmed’ (P21), ‘vulnerable’ (P16), and engaged in ‘trench warfare’ (P6). Similar responses were elicited when participants reflected on how they perceived their colleagues feeling. Participants related colleagues felt, ‘change fatigued’ (P4, P35), ‘cynical’ (P4, P36), ‘clinically depressed’ (P18), ‘unhappy’ (P22), ‘burnt-out’ (P2), ‘withdrawn’ (P19), ‘demoralised’ (P22), ‘despondent’ (P36), ‘desperation’ and ‘helplessness’ (P7), and were ‘experiencing mental health issues’ (P33). Feelings of exhaustion emerged as a salient theme throughout the interviews (P2, P4, P10, P15, P24, P30). P15 linked the exhaustion to increased job demands and decreased personal and job-related resources,

because of so many demands and so much to do, with so limited resources given to yourself, including the allocation of hours. People tend to address everything that comes their way on almost like 24/7 basis … it becomes a never-ending circle.

Participants also related a range of feelings associated with job strain – with their job requiring sustained emotional, psychological effort to manage feelings of being: ‘disempowered’ (P19), ‘frustrated’ (P4), ‘voiceless’(P11), ‘uncertain’ (P12), ‘disengaged’ (P5, P18), ‘isolated’ (P9), ‘cautious’ (P4, P30), ‘worried’ (P26) and ‘conflicted’ (P8). Participants felt that colleagues too displayed a broader, deeper malaise (psychological, physiological, and social disconnection) attributable to the conditions in their academic workplaces.

According to Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2017), job demands not only cause job strain, but ‘employees who experience job strain also perceive and create more job demands over time’, which may result in a ‘loss spiral of job demands and exhaustion’ (p. 277). This manifests in self-undermining ‘behaviour that creates obstacles that may undermine performance’ because employees are ‘too tired to invest the necessary effort in their work’ and is associated with persistent high levels of job strain, workplace stressors, exhaustion, and burnout (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017, p. 277) as presented in .

From the perspective of most participants in this study, the capacity to proactively make changes to job demands and resources (by job crafting for example) is constrained by the confluence of demands and resources across the organisational, team, and individual levels. The implications of these outcomes are discussed next.

Discussion and conclusion

This research has demonstrated the conceptual utility of multilevel JD-R as a framing device through which to consider the dynamic interaction between job demands and job resources for understanding the affordances and constraints to academic employee engagement in a changing university environment and how academic staff respond to and negotiate crisis and complexity in their work environment. It indicates that research and practice should pay more attention to the institutional antecedents of job demands and resources, and the interaction effects of individual, team, and organisational demands-resources in times of crisis.

One of the key attributes of the multilevel JD-R framework is that it encourages a contextualised understanding of psychological and behavioural phenomena, such as employee engagement, in relation to institutional and sectoral factors, eschewing overly individual and ‘psychologised’ accounts of employee relations (Fletcher et al., Citation2020). The foregrounding of the organisational and team levels in the multilevel JD-R framework places calls to reduce self-undermining and loss cycles in a broader context and means, as Bakker and Costa (Citation2014, p. 117) assert, ‘chronically burned-out employees or those at risk for burnout need help from others in order to change the structural causes that contribute to their impaired health status and work capacity’ – help that extends beyond encouraging bottom-up attempts at job-crafting. These hierarchical interactive effects have implications for practice at the organisational team, and individual levels ‘with training across the entire organisation and with accompanying management support’ (Pignata, Citation2020, p. 303).

Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2017) hold that engaged (motivated) employees are likely to use a ‘range of behaviours that lead to higher levels of resources’ (job and personal) and ‘even higher levels of motivation’, in what they term ‘gain spirals’ (p. 276). Despite the varied responses of universities to the COVID-19 disruptors to mitigate against changing job demands, at the individual/personal and team level of resources, participants employed three main strategies: (a) to deal with the unfavourable effects of job demands through active coping and recovery, (b) to maximise favourable effects, achieve goals, and avoid losses through a pattern of self-regulation; and (c) to mitigate against increased demands by job crafting (Demerouti et al., Citation2019). However, many participants reported facing a lack of agency, job clarity, job security, and voice, which significantly affected morale. These factors contributed to a negative spiral of self-undermining, limited engagement, and contributed to a poor work climate.

While individual factors such as, personality differences may contribute to burnout and self-undermining behaviour (Bakker & Costa, Citation2014) it is clear that situational factors, particularly at the organisational level, were identified as central contributors to our interviewees’ emotional and behavioural responses. Mudrak et al. (Citation2017) and McGaughey et al. (Citation2022) Citation2021observe interactive effects of organisational practices and culture within the university sector as contributing to high emotional and psychological strain and low motivation and engagement within a context of significant job demands. Devoid of a work climate considered collegial and founded on interpersonal trust, recognition, and support (McCarthy & Dragouni, Citation2021), the efficacy of such strategies is not sustainable.

At the organisational level Van de Ross et al. (Citation2022) highlight the importance of university leaders recognising the sustaining conditions that enable the engagement of their academic staff. Pignata (Citation2020) has suggested that supportive human resource management practices which promote adequate staffing and task resourcing, underpinned by a clear organisational vision and goals, can support a culture of positive psychological safety. Specific interventions that enable individuals to participate in decision-making reflect a commitment to employee voice and influence perceptions of organisational support, central conditions for creating psychologically safe work environments (see, Pignata, Citation2020, p. 279). However, the efficacy of such interventions, which do not materially change leadership behaviours and actions in the higher education sector, does not future-proof the academic workplace from the next crisis.

In this study, individuals perceived that university leaders and leadership significantly contributed to an environment characterised by organisational and interpersonal mistrust through limited opportunities to engage employee voice. This has led to perceptions of poor psychological safety within the academic workplace. This is consistent with Mudrak et al. (Citation2017) and McCarthy and Dragouni (Citation2021) and requires a mission-focussed approach.

As made clear by Croucher and Lacy’s (Citation2020) review of the perspectives of Australian higher education leadership in the period directly before the COVID-19 pandemic, questions of organisational justice and organisational psychosocial safety climates have not been at the forefront of issues considered by senior leaders within universities and those outside universities in bureaucracies and legislatures. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, these leaders, inside and outside of universities, held a common view on ‘issues largely related to the management and organisational changes within universities that are associated with managerialism … [including] governance and strategic planning’; a shared view that ran counter to ‘the vocal concern of many academic staff of the increasing managerialism in administration and a loss of collegiality’ (Croucher & Lacy, Citation2020, pp. 524–25). However, the 2023 establishment of an inter-jurisdictional working group to look at three priority areas identified in the Australian Universities Accord’s interim report (O’Kane, Citation2023) suggests that such convergent leadership perspectives may change. The three areas include ensuring that universities are good employers that provide a supportive workplace, are safe for staff and students, and have university governing bodies with the right expertise, including in the business of running universities.

Distrust emerged as a salient theme throughout the interviews. These three areas are premised on building a climate of trust. While the outcomes of actions engendered by the Working Group and the Universities Accord are unclear, such change would help to positively affect the JD-Rs of university academics, especially at the organisational level. To help ensure that positive institutions are a common feature of the Australian higher education system (Rothmann & Janse van Rensburg, Citation2020), building trust is foundational. As trust emerged as a key issue for the participants in this study, universities must seek out actions to build trust. How university leaders engage with feedback can have a significant impact on perceptions of trust, respect, and thereby psychosocial safety (Kahn, Citation1990).

To elaborate, feedback-sharing, that is, ‘ … disclosing suggestions for improvement that one has received in the past … ’ (Coutifaris & Grant, Citation2022, p. 1575), has been shown to have greater enduring effects on perceptions of psychological safety than feedback-seeking, ‘ … the act of inquiring for information about one’s performance … ’ (p. 1575). Feedback-sharing promotes self-disclosure and signals to individuals that the leader is receptive to feedback and makes transparent how leaders will react to feedback (both positive and negative) in the future. Furthermore, feedback-sharing, unlike feedback-seeking ‘ … makes … clear to employees that leaders are self-assured enough to recognise and accept their own fallibility … ’ (p. 1577), building trust which is then reciprocated. This action has implications for leadership practice, leadership development, and, more importantly, research into efficacy of leadership development programmes within higher education (see, Brown, Citation2014; Dopson et al., Citation2019) of which there is a dearth, and an area for future investigation.

At the team level, job design features such as job autonomy, feedback, opportunities for development, rewards and recognition, job variety, and work role fit are important predictors of managing demands. However, our qualitative study of academic staff navigating a period of crisis highlighted a key perceived resource – a collegial environment premised on interpersonal trust, recognition, and support (McCarthy & Dragouni, Citation2021). While our study indicated that participants often voiced a concern about the overall collegiality of university workplace culture under the strain of organisational level practices and changes, most participants spoke favourably of their immediate workplace (School) as providing a positive and supportive culture. Safeguarding and improving the relationships between line managers, academic staff, and other staff within schools/departments (Pignata, Citation2020) is a central consideration of universities transitioning through periods of heightened uncertainty and change.

At the individual level, it was clear academic staff employed personal resources to mitigate against changing job demands. Demerouti et al. (Citation2019) observed that employees ‘are more than just passive receivers of external influences; they actively modify their work environment through cognitive interpretation and intentional behaviours’ (p. 6). The cognitive and behavioural responses include seeking greater competence, discretion, and efficiency over their work. The extent to which academic staff are encouraged and supported, including through personal and team resources, to seek out social support in combination with job-crafting, the more likely they are to experience a gain cycle through personal efficiencies which can support psychological empowerment.

While this research indicates that the interviewed academic staff are suffering from job strain, it also appears that the prevailing conditions and expectations pertaining to academic work in Australian universities, and beyond, merit further multilevel investigation for academic employee engagement. Job demands-resources and other structural and organisational factors play a vital role in enhancing or reducing academic employee satisfaction and engagement levels. This is important for universities because as Raina and Khatri (Citation2015) observe, there is a growing consensus of understanding that ‘engaged employees can bring revolutionary transformations in organizations’ (p. 285). Engaged employees can revitalise, reenergise, and transform institutions which is what is needed to manage crisis, complexity, and change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arachie, A.E., Agbaeze, E. K., Nzewi, H. N., & Agbasi, E. O. (2021). Job crafting, a bottom-up job characteristic of academics with an embeddedness potential. Management Research Review, 44(7), 949–969. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-07-2020-0432

- Australian Government, Department of Education. (2022, February 9). Table 1.1 FTE for full-time, fractional full-time and estimated casual staff by work contract, 2012 to 2021, 2021 staff full-time equivalence. https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/2021-staff-fulltime-equivalence

- Bailey, C., Madden, A., Alfes, K., & Fletcher, L. (2017). The meaning, antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement: A narrative synthesis. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12077

- Bakker, A.B., & Albrecht, S. (2018). Work engagement: Current trends. Career Development International, 23(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-11-2017-0207

- Bakker, A.B., & Costa, P. L. (2014). Chronic job burnout and daily functioning: A theoretical analysis. Burnout Research, 1(3), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2014.04.003

- Bakker, A.B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

- Bakker, A.B., & Demerouti, E. (2018). Multiple levels in job demands-resources theory: Implications for employee well-being and performance. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of wellbeing (pp. 1–13). DEF Publishers.

- Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-053933

- Bakker, A.B., & Wang, Y. (2020). Self-undermining behavior at work: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. International Journal of Stress Management, 27(3), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000150

- Bleiklie, I. (1998). Justifying the evaluative state: New public management ideals in higher education. European Journal of Education, 33(3), 299–316. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1503585

- Bottrell, D., & Manathunga, C. (2019). Shedding light on the cracks in neoliberal universities. In D. Bottrell & C. Manathunga (Eds.), Resisting neoliberalism in higher education volume I. Palgrave critical university studies (pp. 1–33). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic Analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

- Brown, A. (2014). The myth of the strong leader: Political leadership in the modern age. Penguin Random House.

- Coutifaris, C.G., & Grant, A. M. (2022). Taking your team behind the curtain: The effects of leader feedback-sharing and feedback-seeking on team psychological safety. Organization Science, 33(4), 1574–1598. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1498

- Croucher, G., & Lacy, W. B. (2020). Perspectives of Australian higher education leadership: Convergent or divergent views and implications for the future? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 42(4), 516–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2020.1783594

- Day, A., Crown, S. N., & Ivany, M. (2017). Organizational change and employee burnout: The moderating effects of support and job control. Safety Science, 100, 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.03.004

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2023). Job demands-resources theory in times of crises: New propositions. Organizational Psychology Review, 13(3), 209–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/20413866221135022

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2019). Job demands-resources theory and the role of individual cognitive and behavioral strategies. In T. Taris, M. Peeters, & H. D. Witte (Eds.), The fun and frustration of modern working life: Contributions from an occupational health psychology perspective (pp. 94–104). Pelckmans Pro.

- Dopson, S., Ferlie, E., McGivern, G., Fischer, M. D., Mitra, M., Ledger, J., & Behrens, S. (2019). Leadership development in higher education: A literature review and implications for programme redesign. Higher Education Quarterly, 73(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12194

- Fletcher, L., Bailey, C., Alfes, K., & Madden, A. (2020). Mind the context gap: A critical review of engagement within the public sector and an agenda for future research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(1), 6–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1674358

- Frazier, M.L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta‐analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12183

- Gibbs, G.R. (2007). Analyzing qualitative data. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208574

- Han, J., Yin, H., Wang, J., & Bai, Y. (2020). Challenge job demands and job resources to university teacher well-being: The mediation of teacher efficacy. Studies in Higher Education, 45(8), 1771–1785. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1594180

- Hare, J. (2022, February 13). Pandemic-hit unis cut up to 27,00 jobs in a year. Financial Review. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/education/university-jobs-slashed-as-pandemic-forces-students-away-20220211-p59vqn.

- Joseph, S., & Rao, C. B. N. (2022). Transformation leadership and work performance: Mediating role of faculty engagement in higher educational institutions during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Management in Education, 16(6), 664–680. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMIE.2022.126588

- Kahn, W.A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287

- Kumar, R., & Sia, S. K. (2012). Employee engagement: Explicating the contribution of work environment. Management and Labour Studies, 37(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103700104

- Kvale, S. (2007). Doing interviews. SAGE Publications, Ltd.

- Kwon, K., & Kim, T. (2020). An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: Revisiting the JD-R model. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100704–100718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100704

- Lee, J.Y., & Lee, Y. (2018). Job crafting and performance: Literature review and implications for human resource development. Human Resource Development Review, 17(3), 277–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484318788269

- Lee, J.Y., Rocco, T. S., & Shuck, B. (2020). What is a resource: Toward a taxonomy of resources for employee engagement. Human Resource Development Review, 19(1), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484319853100

- León, M. (2021). University president perceptions of part-time faculty engagement. Human Resource Development International, 24(5), 490–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2021.1951523

- Littleton, E., & Stanford, J. (2021). An avoidable catastrophe: Pandemic job losses in higher education and their consequences. The Australia Institute Centre for Future Work. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2021-09/apo-nid314011.pdf

- Macey, W.H., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2007.0002.x

- McCarthy, D., & Dragouni, M. (2021). Managerialism in UK business schools: Capturing the interactions between academic job characteristics, behaviour and the ‘metrics’ culture. Studies in Higher Education, 46(11), 2338–2354. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1723524

- McGaughey, F., Watermeyer, R., Shankar, K., Suri, V. R., Knight, C., Crick, T., Hardman, J., Phelan, D., & Chung, R. (2022). ‘This can’t be the new norm’: Academics’ perspectives on the COVID-19 crisis for the Australian university sector. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(7), 2231–2246. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1973384

- Mudrak, J., Zabrodska, K., Kveton, P., Jelinek, M., Blatny, M., Solcova, I., & Machovcova, K. (2017). Occupational well-being among university faculty: A job demands-resources model. Research in Higher Education, 59(3), 325–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9467-x

- Norton, A. (2022, February 10). University job losses in the first year of COVID-19. Higher education commentary from carlton. https://andrewnorton.net.au/2022/02/10/university-job-losses-in-the-first-year-of-covid-19/ Accessed 22/12/2023.

- O’Kane, M. (2023). Australian universities accord interim report. Australian Government Department of Education from https://www.education.gov.au/australian-universities-accord/resources/accord-interim-report

- Park, S., & Park, S. (2023). Contextual antecedents of job crafting: Review and future research agenda. European Journal of Training & Development, 47(1/2), 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejtd-06-2021-0071

- Patton, M.Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325002001003636

- Pignata, S. (2020). Stress in Australian Universities: Initiatives to enhance well-being. In R. J. Burke & S. Pignata (Eds.), Handbook of research on stress and well-being in the public sector (pp. 294–307). Edward Elgar.

- Raina, K., & Khatri, P. (2015). Faculty engagement in higher education: Prospects and areas of research. On the Horizon, 23(4), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-03-2015-0011

- Rothmann, S., & Janse van Rensburg, C. (2020). Towards positive institutions: Positive practices and employees’ experiences in higher education institutions. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 46(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v46i0.1733

- Rothmann, S., & Jordaan, G. M. E. (2006). Job demands, job resources and work engagement of academic staff in South African higher education institutions. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 32(4), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v32i4.247

- Sarwar, F., Panatik, S. A., Sukor, M. S. M., & Rusbadrol, N. (2021). A job demand–resource model of satisfaction with work–family balance among academic faculty: Mediating roles of psychological capital, work-to-family conflict, and enrichment. Sage Open, 11(2), 215824402110061. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211006142

- Slade, C.P., Ribando, S., Fortner, C. K., & Walker, K. V. (2022). Mergers in higher education: It’s not easy. Merger of two disparate institutions and the impact on faculty research productivity. Studies in Higher Education, 47(6), 1215–1226. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1870948

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841

- Van de Ross, M.R., Olckers, C., & Schapp, P. (2022). Engagement of academic staff amidst COVID-19: The role of perceived organizational support, burnout risk, and lack of reciprocity as psychological conditions. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(874599), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.874599

- Whitsed, C., & Girardi, A. (2022). Where has the joy of working in Australian universities gone? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/where-has-the-joy-of-working-in-australian-universities-gone-184251

- Whitsed, C., Girardi, A., Williams, J. P., & Fitzgerald, S. (2024). Where has the joy gone? A qualitative exploration of academic university work during crisis and change. Higher Education Research & Development.

- Winefield, A.H., Gillespie, N., Stough, C., Dua, J., Hapuarachchi, J., & Boyd, C. (2003). Occupational stress in Australian university staff: Results from a National Survey. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.10.1.51

- Wray, S., & Kinman, G. (2022). The psychosocial hazards of academic work: An analysis of trends. Studies in Higher Education, 47(4), 771–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1793934

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.2307/259118

- Xu, L. (2019). Teacher-researcher role conflict and burnout among Chinese university teachers: A job demand-resources model perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 44(6), 903–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1399261