ABSTRACT

This review focuses on the nature, influence, and modifiability of academics’ mindsets. Synthesising the large, growing, and influential body of adult growth and fixed mindset research with applied research into academia, it documents emerging evidence suggesting an academic’s growth mindset can improve their personal performance, career success, and well-being – and some student, peer, and workplace outcomes. Commencing with a primer to the general research into the nature and effects of mindsets in adults, we recommend that while more and better applied research is needed, and there is sufficient general and research in academics to incorporate growth mindset principles into professional development for individual academics, managers and institutional leaders.

Introduction

Success matters for academics, but what matters most for academics’ success? A growing volume of international research identifies a pivotal factor that leads to improvements in human performance, achievement, and well-being: the growth mindset (Dweck, Citation2006). In this review, we will explore the nature, influence and modifiability of the growth mindsets in the performance and development of academics and examine its impact on academics and their students. Throughout, we recognise that mindsets are implicit theories of the nature and influence of intelligence (Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019; Martin et al., Citation2017). A key variation Dweck (Citation2006) termed as being between the entity theory of intelligence (fixed mindset) and the incremental theory of intelligence (growth mindset) (Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019).

Fixed mindsets: proving ability via the verification of talent

The fixed mindset is characterised by primordial assumptions that personal abilities are fixed, with successes acting to verify current or enduring abilities, skills and/or talent (Dweck, Citation2006). Mindsets are coherent and highly cohesive cognitive systems forming a highly robust framework of self-reinforcing perceptions, beliefs, reactions, and goals (, ). Consequently, an academics’ perception of their own talent as an engaging speaker, thoughtful listener or successful grant writer is more likely to be reinforced by their own subsequent attainments and performance, which then act to influence their thoughts and behaviours. The underlying talent is attributed to be both pivotal to, and evident in, the success with other possible contributing contextual factors being downplayed, such as: privilege, others, or luck (Neuroleadership Institute, Citation2018).

Table 1. Consequences of mindsets for goals, beliefs, efforts, and reactions.

However, this strong association between the fixed mindset and corroboration of talent is also likely to have negative consequences because perceived inadequacies in performance lead to perceptions that the absence of ability is also fixed (Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019). Consequently, the individual devotes no efforts to this: ‘I will never be a people person!’ This is more likely to negatively impact self-confidence and self-beliefs, including helplessness and low self-esteem (Dweck, Citation2006). Paradoxically, sustained success is also compromised under the fixed mindset because people with fixed mindsets often set less ambitious goals to increase the probability of attaining the valuable psychological verification of their transcending ability that even results from meeting less aspirational goals (Dweck, Citation2006). The fixed mindset functions predominantly to prove ability.

Growth mindsets: improving ability via learning

Conversely, the goal of the growth mindset is not to prove but to improve ability (Neuroleadership Institute, Citation2018). The growth mindset also forms a coherent and cohesive self-reinforcing cognitive system (). Ability, talent, and other skills can always grow, change, and improve over time and situation irrespective of success or failure (Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019), with success deriving from the ability to reflect, learn, and improve, whatever transpires (Heslin & Keating, Citation2017).

While mindsets are usually presented dichotomously (i.e., fixed versus growth), in natural settings, mindsets are situational. A person’s dominant mindset in any situation is more likely to vary on a continuum between growth and fixed extremes – with their precise position on the mindset continuum varying by situation (Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019). For example, a Chair’s growth mindset may be dominant when dealing with safer learning, such as mastering a new email system, but much more fixed when learning how to be calmer when approached by colleagues who openly question the Chair’s integrity. As such, mindsets are situationally specific dispositional biases (Brummelman & Thomas, Citation2017; Haimovitz & Dweck, Citation2017) rather than as fixed traits that define people across time and situation (Heslin & Keating, Citation2017).

The case for examining and harnessing academics’ mindsets

It is important to understand and address mindsets in academia and academics for a number of reasons. Firstly, there is persuasive evidence via large systematic reviews (see Supplemental Material: ) that mindsets influence outcomes over the life course. While early research addressed children’s mindsets, mindsets during adulthood are now known to influence aspects of work performance, achievement, and wellbeing (Bahlmann et al., Citation2015). For example, in adults, the growth mindset is linked to sustained improvements in work performance (Canning et al., Citation2020), greater openness to feedback (Ng, Citation2018), higher motivation to learn from failure (Canning et al., Citation2020; Ng, Citation2018), and better error self-monitoring (Ng, Citation2018). When goals are not met, adults with fixed mindsets are less likely to seek feedback (Zingoni, Citation2017) and tend to have poorer wellbeing related to confidence crises, reduced motivation, and lower effort (Heslin & Keating, Citation2017).

Systematic reviews also indicate that mindsets during adulthood can, however, be modified to increase attainment and performance (Costa & Faria, Citation2018). Further, a recent large national randomised trial in Nature showed that effective programs can be short (<60 min) and provided online (Yeager et al., Citation2019).

Mindsets not only exist at the individual level but at the organisational level too – with employees’ mindsets can both be influenced by and influence the mindset dominant in their workplaces (Canning et al., Citation2020; Murphy & Dweck, Citation2010). Workplace mindsets can also be resistant to change (Murphy & Dweck, Citation2010). When applying to join organisations, depending on the dominant mindset of the organisation, potential employees are more likely to adjust how they present themselves to appear either smarter (fixed mindset) or more motivated (growth mindset), which influences both future hiring practices and sustains the dominance of the mindset (Murphy & Dweck, Citation2010).

There are ethical reasons to explore mindsets in academia. To increase the probability of success, people with dominant-fixed mindsets report being more willing to ‘play the system’ to falsely attain success or be unfairly harsh to others to boost self-confidence (Dweck, Citation2006). In academia, this could lead to workplace bullying or questionable research practices (Bruton et al., Citation2020).

In summary, adults’ dominant mindsets, though established in childhood, influence personal and work-related outcomes over life. As these mindsets are likely to influence both work and workplaces, it is useful and timely to consider applied research into the nature, influence and modifiability of academics’ mindsets and the impacts of these on their development. Accordingly, examines existing published research to identify:

What are the implications of fixed versus growth mindsets in academics?

What is the prevalence of fixed versus growth mindsets in academics?

Can academics’ mindsets be changed to more growth orientations?

Methods

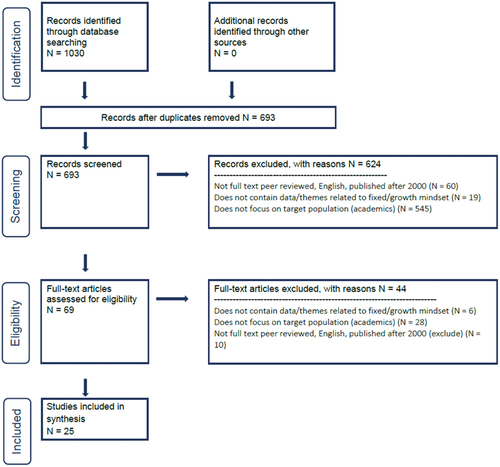

A scoping review was done to document findings from published empirical research (Appendix 1). The search was broad and included studies using different research methods, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (Appendix 2).

Search and selection of studies

The search was comprehensive and detailed, using quality assurance recommendations (Shea et al., Citation2009), was organised in the DistillerSR software (Evidence Partners, Citation2017), and reported using PRISMA recommendations (Moher et al., Citation2009) (Appendix 1) Pre-determined inclusion criteria were used to screen articles for inclusion by titles and abstracts initially (Appendix 2). Secondary screening involved full-text review.

Published literature was identified by searching ERIC 1965- (Ovid), MEDLINE 1946- (Ovid), APA PsycINFO 2002- (Ovid), Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, and Academic Search Complete (EBSCO). The search strategy (see Supplemental Material: ) included controlled vocabularies, such as the ERIC thesaurus, and keywords. No filters were applied to limit the retrieval by study type. In response to resource constraints and to ensure appropriate homogeneity of articles, the search was limited to English language documents published from 1 January 2000, to 15 February 2021. Conference abstracts and non-journal publications (i.e., grey literature) were excluded from the search results, but student dissertations were included. The initial search was completed in February 2021.

Data extraction, quality, and synthesis

For each included study, data extraction was performed using a customised data extraction form. To generate data related to mindsets, based on the foci of the study, verbatim data and themes were cut and pasted from the published studies into the extraction form in DistillerSR. For qualitative studies, data were derived from themes or data relating to growth and fixed mindsets, while for quantitative or mixed-method studies, primary numerical data that is interpreted as giving insight into fixed and growth mindsets were extracted from each study. In deciding whether data or themes are pertinent to the synthesis, whether or not the identified data offers knowledge regarding fixed and growth mindsets was considered. The quality of each included study was appraised using the appropriate quality appraisal tool (CASP, Citation2020; Hong et al., Citation2018).

To synthesise the qualitative, mixed-method, and quantitative research, interpretive synthesis was used (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). This approach (Appendix 3) is suitable to synthesise qualitative, mixed-methods, and quantitative research (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2004), and can thus synthesise findings from studies using a wide range of methods.

Results

From 1030 papers, after the removal of duplicates and screening (n = 693), 25 papers met the inclusion criteria (Appendix 4).

Study characteristics

Most of the studies (n = 17) examined both fixed and growth mindsets, with the remainder (n = 8) focusing solely on the growth mindset (Åkerlind, Citation2005; Holmes, Citation2018; Kamhawy et al., Citation2020, Norman et al., Citation2021; Powers, Citation2015; Richardson et al., Citation2020; Rolley, Citation2020; Sunga & Kass, Citation2019). No studies focused on the fixed mindset alone. Almost, half the studies (12/25) used qualitative methods, and 44% (11/25) used quantitative methods, while 6% (2/25) used mixed methods.

Most studies were conducted in North America: 18/25 studies were set in the United States, and two in Canada (Jeffs et al., Citation2021; Kamhawy et al., Citation2020). The additional five studies originated in Austria (Kostoulas et al., Citation2019), Australia (Åkerlind, Citation2005), and Spain (Matias-Garcia & Cubero-Perez, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Thadani et al., Citation2010).

The nature and determinants of academics’ mindsets

Studies to determine the prevalence of fixed and growth mindset in academics (Canning et al., Citation2019; Jeffs et al., Citation2021; Matias-Garcia & Cubero-Perez, Citation2020a; Rolley, Citation2020) varied widely in terms of quality, methods, demographic, and population considerations. There was poor evidence of the prevalence of different mindsets in academics. One study identified that males and females were equally likely to endorse fixed mindset beliefs (Canning et al., Citation2019), whereas other work found substantial differences (Matias-Garcia & Cubero-Perez, Citation2020a) with males expressing greater affinity with the growth mindset compared to female academics. Additionally, males reported less affinity to the idea that intelligence is tied to genetics (than did females) (Matias-Garcia & Cubero-Perez, Citation2020a). Due to the small size of the evidence, these findings should be viewed as weak and preliminary. While there is no evidence that academics’ mindsets differed by disciplines, age, or race, mindset beliefs were similar across disciplines (Canning et al., Citation2019), age (Canning et al., Citation2019), and race/ethnicity (Canning et al., Citation2019).

There was mixed evidence as to whether job status influences mindsets. Some studies identified that job factors do not influence mindsets, including tenure status (i.e., pre- or post-tenure or permanence of appointment) or years of teaching experience (Canning et al., Citation2019; Matias-Garcia & Cubero-Perez, Citation2020a). However, Jeffs et al. (Citation2021) identified academics with fixed mindsets had higher levels of stress when receiving teaching feedback, with stress being highest in more experienced academics. Variation was also noted across academic career tracks (Rolley, Citation2020) with tenure-track faculty being more likely to have fixed mindsets while teaching faculty was more likely to have growth mindsets.

Implications of academics’ mindsets

In contrast to this weaker evidence, mindsets had meaningful and consistent effects on aspects of academics’ personal and professional development, academics’ behaviours, and their influence on student outcomes and engagement. Study findings indicated positive and consistent evidence that academics’ mindsets influenced behaviours linked to learning and development.

Professional development

Academics with a growth mindset were more likely to participate in professional development (PD) of various types (Kostoulas et al., Citation2019; Thadani et al., Citation2010, Citation2015), including for teaching (Strage & Merdinger, Citation2014). Growth mindsets were also linked to increased ability to learn a new technology (Rolley, Citation2020). Those with growth mindsets had a higher interest and motivation to do so (Auten, Citation2013; Strage & Merdinger, Citation2014; Thadani et al., Citation2010, Citation2015). Conversely, academics with a stronger fixed mindset were not only less likely to engage in PD but preferred formal PD opportunities over collaborative or self-reflective forms of PD (Thadani et al., Citation2015) and chose less variety in their PD opportunities (Thadani et al., Citation2010).

Openness to feedback and data

Academics with a growth mindset were more likely to report being open to personal change (Kamhawy et al., Citation2020; Kostoulas et al., Citation2019) using research (Kostoulas et al., Citation2019) or feedback (Kamhawy et al., Citation2020). Growth mindsets were also linked to higher:

Openness to learning new strategies (Rolley, Citation2020)

Creativity and proactivity to change (Holmes, Citation2018)

Adaption of teaching practices (Aragón et al., Citation2018; Holmes, Citation2018; Richardson et al., Citation2020)

Reflectiveness on personal practice and seeking improvement was higher with the growth mindset even when feedback data were of low-quality (Kamhawy et al., Citation2020). Conversely, those with a dominant fixed mindset used data for self-improvement only if they perceived it to be of high quality (Kamhawy et al., Citation2020).

Perceptions of students

Academics overwhelmingly viewed students as being more likely to possess fixed mindsets (Auten, Citation2013; O’Leary et al., Citation2020; Oduwole, Citation2016; Powers, Citation2015). For example, academics could view some students as more intelligent than others, and up to 80% of the time expressed fixed mindset views of intelligence (Oduwole, Citation2016).

Student engagement and learning

Academics’ growth mindsets had consistent positive effects on student progress and attainment (Aragón et al., Citation2018; Canning et al., Citation2019; Fuesting et al., Citation2019; LaCosse et al., Citation2020; Muenks et al., Citation2020; Powers, Citation2015; Richardson et al., Citation2020) and program admission (Scherr et al., Citation2017). Academics judged students as more likely to be successful if they adopted a growth mindset (Oduwole, Citation2016) and when taught by academics with growth mindsets, students demonstrated:

Higher interest in particular courses or majors (Fuesting et al., Citation2019; LaCosse et al., Citation2020; Muenks et al., Citation2020);

Higher interest in pursuing STEM majors (Fuesting et al., Citation2019) or courses (LaCosse et al., Citation2020; Muenks et al., Citation2020);

More engagement (Fuesting et al., Citation2019; Muenks et al., Citation2020);

A greater sense of belonging (Muenks et al., Citation2020);

Fewer concerns about assessment (LaCosse et al., Citation2020; Muenks et al., Citation2020);

Higher expectations to perform better (LaCosse et al., Citation2020; Muenks et al., Citation2020) and be treated fairly (LaCosse et al., Citation2020);

More helping behaviours towards other students (Fuesting et al., Citation2019); and,

More goal-oriented behaviour overall (Fuesting et al., Citation2019).

Conversely, when taught by academics with fixed mindset, students had negative perceptions about how they would be treated, evaluated, belong, engage, and perform (Fuesting et al., Citation2019; LaCosse et al., Citation2020; Muenks et al., Citation2020). Academics’ mindset could also widen inequities – as a fixed mindset in academics was more strongly associated with lower course performance among Black, Latino, and Indigenous students than among White and Asian students (Canning et al., Citation2019).

Modifiability of mindsets

Modifying students’ mindsets

Academics’ behaviour and teaching around mindsets were also found to influence students’ mindsets (Auten, Citation2013; Powers, Citation2015) – for example, by teaching students directly about mindsets or actively modelling growth mindset practices or behaviours (Auten, Citation2013), and engaging students in activities to change their mindsets, from fixed to growth (Powers, Citation2015). In one intervention (Powers, Citation2015), academics participated in specialised training to adopt new teaching practices intended to change student mindset, but the PD also had a significant impact on their own mindset and practices as well, with 100% of participants reporting changes, and the intervention described by participants as ‘transformative’ (Powers, Citation2015, p. 81). The changes in mindset were qualitatively described as ‘dramatic’, with one participant stating, ‘with practice, I completely changed my mindset’ (Powers, Citation2015, p. 56). Additionally, findings suggested that intelligence does not necessarily guarantee academic success and that adopting a growth mindset was key to increase academic success (Powers, Citation2015).

Modifying academics’ mindsets

Other studies demonstrated that academics experience various challenges when changing their own mindsets related to:

Lack of knowledge on the nature and influence of mindsets (Auten, Citation2013; Powers, Citation2015);

Lack of time to engage with mindset learning (Auten, Citation2013; Powers, Citation2015); and,

Cultural barriers to embracing a growth mindset (Auten, Citation2013).

However, all five studies using experimental designs () identified that growth mindsets could be strengthened in academics via initiatives and programs (Auten, Citation2013; Jeffs et al., Citation2021; O’Leary et al., Citation2020; Powers, Citation2015; Sunga & Kass, Citation2019). While these studies were appraised to be of low to moderate quality, positive changes were observed following growth mindset oriented academic development, including:

Table 2. Mindset intervention studies.

Table 3. Recommended shifts from fixed to the growth mindset.

Workshops (Auten, Citation2013; Jeffs et al., Citation2021; O’Leary et al., Citation2020);

Keynote addresses (Jeffs et al., Citation2021);

Long-term growth mindset development programs (Sunga & Kass, Citation2019); and,

Course-based content overtly intended to benefit students (Auten, Citation2013; Powers, Citation2015).

These programs had diverse benefits, including academics:

Experiencing lower distress from feedback (Jeffs et al., Citation2021);

Improving as public speakers (Sunga & Kass, Citation2019);

Being more open to meeting student needs and adaptation (Auten, Citation2013; O’Leary et al., Citation2020; Powers, Citation2015); and,

Reduced beliefs about students’ fixed mindsets (Auten, Citation2013; Powers, Citation2015).

Due to differences in outcomes and measurement, the consistency of changes in effect sizes and the overall meaningfulness of the statistically significant benefits from these programs could not be calculated. However, effective programs to support academics develop their growth mindset tended to:

Incorporate dedicated content for the academics on mindsets that is discipline-specific and includes practical examples suggested practical strategies for implementation and downloadable resources (Auten, Citation2013; Powers, Citation2015); and,

Engage university senior administration to make mindset education a priority (Auten, Citation2013; Powers, Citation2015).

Discussion

The use of growth mindset approaches in academic workplaces and academics must take into account both the large size and higher-quality evidence supporting the benefits of growth mindsets in adults generally with the relatively smaller and lower-quality evidence in academia specifically.

Accordingly, while this review found research into the relative prevalence of mindsets in academia to be weak, there is emerging yet consistently positive evidence that academics’ growth mindsets have a range of benefits for academics and their students and, crucially, can be modified (Burnette et al., Citation2020). Possible benefits include academics’ professional development, behaviours, success – and student outcomes. On this evidence, we encourage further exploration of growth mindset principles to guide practices around individuals and teams, management, and policy in higher education ().

In modifying the strength of the following recommendations, we recognise that this review was based on established quality assurance standards (Shea et al., Citation2009) and included published studies across a variety of methods and a large volume of published research. However, as with many reviews, our conclusions and recommendations must take into account many complexities, notably the diverse nature and variable quality of the evidence documented. Current applied evidence remains relatively small in size and variable in study quality. Studies in this area may be prone to publication bias – the tendency for affirmative studies to be more likely to be published (Franco et al., Citation2014). This may lead to an over-estimation of the relative benefits of the growth mindsets by removing negative results from the published literature.

Recommendations for people, management, and policy

While more research is needed, both general and applied research suggest that shifts from fixed mindset principles (focused on achievement) to growth mindset practices (focused on progress) have promising potential benefits for individuals, teams, management, and policy in academia (). Given the emerging nature of research into growth mindsets in academia, the relative attractiveness of these recommendations is influenced not only by the likelihood and size of benefits but also the potential costs.

Personal, interpersonal and team recommendations

Effective steps to promote the growth mindset can be small and relatively easy to implement at the individual level from as simple as intentionally allocating time for personal or team learning in the working week with the growth mindset aims of learning to be better, increasing perseverance, and/or improving strategic thinking (Clark & Sousa, Citation2018). For individuals or teams, ideally, such shifts should be made based on knowledge of the nature and application of growth mindset principles to people and teams, as could be attained via engaging with key concepts via seminal readings, videos, or book clubs.

Other personal, interpersonal and team-focused applications of growth mindset principles relate to how success and failure in work are viewed and handled, how more successful peers are viewed, feedback to]and from others, and cultural practices in workspaces that signal dwelling on past successes (e.g., the display of degree certificates) versus future development (e.g., the display of professional development books). Whenever possible, to be oriented to the growth mindset, actions should be focused less on ability and the presence of talent or giftedness than the imperative of constant learning and improvement from all situations, including those associated with success and failure. These individual and interpersonal behaviours should be premised on destigmatizing failure.

Management recommendations

Based on this review, those who oversee and/or support the professional development of academics in formal roles (whether in central units such as human resources or professional development) or in academic departments themselves (as academic line managers) can justify carefully incorporating growth mindset principles into existing or new strategies, supports, and other initiatives to support personal and workplace success.

However, the potential diversity and emerging status of current evidence in academia is challenging. Potential applications of growth mindset interventions are markedly diverse (Clark & Sousa, Citation2018). - from more costly full-scale online or in-personal workplace development programs to increase self-knowledge and the prevalence of the growth mindset in both individuals and teams of academics to more subtle shifts in what is rewarded and celebrated in working cultures.

The evidence to justify formal programs to promote the growth mindset in academia is promising but still partial. As such, there is more persuasive general than applied evidence that academic workplaces should offer education and support to all academic staff to develop their growth mindsets. A balanced approach could be to target growth mindset programs for staff who are earlier in their career, involved in teaching (the area in which most existing applied interventions are done) or experience frequent failures, such as around research grants or manuscripts.

That said, the evidence to support smaller-scale and more localised attempts to incorporate growth mindset principles into workplace cultures is more attractive than programs taking into account both benefits and lower costs. Cultural initiatives to promote the growth mindset can include management intentionally switching from predominantly celebrating team and individual success to celebrating, rewarding, and incentivising strategy savviness, perseverance of effort especially after failure(s), and team and individual learning. These could occur in or around formal meetings, in official online communications, or intentional meetings focused on sharing failures and learning over recent periods or the career. Celebrating and sharing learning over success in this way addresses the harmful tendency for academic workplaces and teams or individual academics to overly esteem and celebrate career successes – cultural behaviours that are likely paradoxically to lead to less success over time by fostering fixed mindset tendencies in people and workplaces. The relative attractiveness of such subtle smaller-scale and more logistically implementable approaches should not be underestimated: they are cheaper and have more current evidence in academia than large-scale programs.

Policy recommendations

The utilisation of growth mindset principles in policy within and for academic workplaces warrants consideration. Policy should utilise evidence when possible, and currently, the application of growth mindset principles to academic workplaces is promising but rudimentary. As applied research continues to grow and improve, those involved in policy-making should consider using growth mindset principles in relation to hiring – which has persuasive evidence outside of academic settings. As the evidence for workplace-wide professional development evolves, policy should grow accordingly to formalise this – as appropriate – as a workplace expectation at the institutional level.

Research recommendations

The vast majority of efforts to integrate growth mindset principles into education have occurred in elementary and high-school settings (Brummelman & Thomas, Citation2017). Mirroring the benefits of growth mindsets across both childhood and adulthood, academia should recognise and further explore the benefits of academics’ growth mindsets for academics, their workplaces, and students. While the volume of research on academics’ growth mindsets is increasing, some key gaps remain. Despite evidence of the positive influence of growth mindsets on academics, there have been no high-quality or large-scale national or international surveys of the relative prevalence of growth and fixed mindsets in large cohorts of academics. Further substantial work is also needed to assess how these mindsets vary by sex, country, discipline, and years of experience. Large national and international surveys of academics’ mindsets would allow the predictors of academics’ mindsets to be better understood and programs to be better targeted and prioritised to those most likely to benefit or in need. Research is also needed to explore how dominant mindsets vary over the career, including new academic staff members, senior staff, and managers.

While there is a growing and promising body of evidence supporting programs to foster growth mindsets in academics, the quality of current experimental studies requires improvement. As has been done with high-school students (Yeager et al., Citation2019), large national trials of online growth mindset interventions for academics are now needed. These trials should draw on key determinants of effectiveness from past trials, be sufficiently powered, large in sample size, and measure meaningful outcomes in academics and students over the longer term. Online interventions to promote the growth mindset offer a particularly attractive alternative to traditional face-to-face initiatives in terms of accessibility, feasibility, and scalability.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Åkerlind, G. S. (2005). Academic growth and development - How do university academics experience it? Higher Education, 50(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6345-1

- Aragón, O. R., Eddy, S. L., Graham, M. J., & Brickman, P. (2018). Faculty beliefs about intelligence are related to the adoption of active-learning practices. CBE - Life Sciences Education, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-05-0084

- Auten, M. A. (2013). Helping educators foster a growth mindset in community college classrooms. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/1073

- Bahlmann, J., Aarts, E., & D’Esposito, M. (2015). Influence of motivation on control hierarchy in the human frontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(7), 3207–3217. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2389-14.2015

- Brummelman, E., & Thomas, S. (2017). How children construct views of themselves: A social-developmental perspective. Child Development, 88(6), 1763–1773. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12961

- Bruton, S. V., Medlin, M., Brown, M., & Sacco, D. F. (2020). Personal motivations and systemic incentives: Scientists on questionable research practices. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(3), 1531–1547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00182-9

- Burnette, J. L., Knouse, L. E., Vavra, D. T., O’Boyle, E., & Brooks, M. A. (2020). Growth mindsets and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 77, 101816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101816

- Canning, E. A., Muenks, K., Green, D. J., & Murphy, M. C. (2019). STEM faculty who believe ability is fixed have larger racial achievement gaps and inspire less student motivation in their classes. Science Advances, 5(2), eaau4734. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4734

- Canning, E. A., Murphy, M. C., Emerson, K. T., Chatman, J. A., Dweck, C. S., & Kray, L. J. (2020). Cultures of genius at work: Organizational mindsets predict cultural norms, trust, and commitment. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(4), 626–642. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219872473

- Clark, A. M., & Sousa, B. J. (2018). How to be a happy academic: A guide to being effective in research, writing and teaching. SAGE.

- Costa, A., & Faria, L. (2018). Implicit theories of intelligence and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00829

- Critical Appraisal Skills Program. (2020). CASP check list. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Dixon-Woods, M., Agarwell, S., Young, B., Jones, D., & Sutton, A. (2004). Integrative approaches to qualitative and quantitative evidence. Health Technology.

- Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Dweck, C., & Yeager, D. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166

- Evidence Partners. (2017). DistillerSR [ Computer program].

- Franco, A., Malhotra, N., & Simonovits, G. (2014). Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science, 345(6203), 1502–1505. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255484

- Fuesting, M. A., Diekman, A. B., Boucher, K. L., Murphy, M. C., Manson, D. L., & Safer, B. L. (2019). Growing STEM: Perceived faculty mindset as an indicator of communal affordances in STEM. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 117(2), 260–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000154

- Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. (2017). The origins of children’s growth and fixed mindsets: New research and a new proposal. Child Development, 88(6), 1849–1859. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12955

- Heslin, P. A., & Keating, L. A. (2017). In learning mode? The role of mindsets in derailing and enabling experiential leadership development. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LEAQUA.2016.10.010

- Holmes, L. Q. (2018). Impacts of performance-based funding institutional measurement goals on faculty at state colleges. [Ph.D. Dissertation]. Northcentral University.

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Jeffs, C., Nelson, N., Grant, K. A., Parb, N., & Viceer, N. (2021). Feedback for teaching development: Moving from a fixed to growth mindset. Professional Development in Education, 49(5), 842–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1876149

- Kamhawy, R., Chan, T. M., & Mondoux, S. (2020). Enabling positive practice improvement through data-driven feedback: A model for understanding how data and self-perception lead to practice change. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13504

- Kostoulas, A., Babić, S., Glettler, C., Karner, A., Mercer, S., & Seidl, E. (2019). Lost in research: Educators’ attitudes towards research and professional development. Teacher Development, 23(3), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2019.1614655

- LaCosse, J., Murphy, M. C., Garcia, J. A., & Zirkel, S. (2020). The role of STEM professors’ mindset beliefs on students’ anticipated psychological experiences and course interest [data file]. https://osf.io/7mkj6/

- Martin, A., Bostwick, K., Collie, R., & Tarbetsky, A. (2017). Implicit theories of intelligence. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (p. 2184). Springer.

- Matias-Garcia, J. A., & Cubero-Perez, R. (2020a). “Einstein worked his socks off”. Conceptions of intelligence in university teaching staff. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 9(2), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.17583/ijep.2020.4553

- Matias-Garcia, J. A., & Cubero-Pérez, R. (2020b). Heterogeneity in the conceptions of intelligence of university teaching staff. Culture & Psychology, 27(3), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X20936926

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Muenks, K., Canning, E. A., LaCosse, J., Green, D. J., Zirkel, S., Garcia, J. A., & Murphy, M. C. (2020). Does my professor think my ability can change? students’ perceptions of their STEM professors’ mindset beliefs predict their psychological vulnerability, engagement, and performance in class. Journal of Experimental Psychology General, 149(11), 2119–2144. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000763

- Murphy, M., & Dweck, C. (2010). A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(3), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209347380

- Neuroleadership Institute. (2018). Idea report: Growth mindset culture – corporate membership. https://membership.neuroleadership.com/material/idea-report-growth-mindset-culture/

- Ng, B. (2018). The neuroscience of growth mindset and intrinsic motivation. Brain Sciences, 8(2), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8020020

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. SAGE.

- Norman, M. K., Mayowski, C. A., & Fine, M. J. (2021). Authorship stories panel discussion: Fostering ethical authorship by cultivating a growth mindset. Accountability in Research, 28(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2020.1804374

- Oduwole, T. (2016). Perceptions of community college faculty members’ mindsets and their projections of students’ academic outcomes. [ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global]. (AAT 10038412). Capella University.

- O’Leary, E. S., Shapiro, C., Toma, S., Sayson, H. W., Levis-Fitzgerald, M., Johnson, T., & Sork, V. L. (2020). Creating inclusive classrooms by engaging STEM faculty in culturally responsive teaching workshops. International Journal of STEM Education, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00230-7

- Powers, M. D. (2015). Growth mindset intervention at the community college level: A multiple methods examination of the effects on faculty and students [UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations]. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/48575763

- Richardson, D. S., Bledsoe, R. S., Cortez, Z., & Tanner, K. (2020). Mindset, motivation, and teaching practice: Psychology applied to understanding teaching and learning in STEM disciplines. CBE - Life Sciences Education, 19(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-11-0238

- Rolley, T. A. (2020). Faculty mindset and the adoption of technology for online. Grand Canyon University.

- Rubin, L. M., Dringenberg, E., Lane, J. J., & Wefald, A. J. (2019). Faculty beliefs about the nature of intelligence. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 19(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v19i4.24158

- Scherr, R. E., Plisch, M., Gray, K. E., Potvin, G., & Hodapp, T. (2017). Fixed and growth mindsets in physics graduate admissions. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.13.020133

- Shea, B. J., Hamel, C., Wells, G. A., Bouter, L. M., Kristjansson, E., Grimshaw, J., Henry, D. A., & Boers, M. (2009). AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1013–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009

- Strage, A., & Merdinger, J. (2014). Professional growth and renewal for mid-career faculty. The Journal of Faculty Development, 28(3), 41–50.

- Sunga, K. L., & Kass, D. (2019). Taking the stage: A development programme for women speakers in emergency medicine. Emergency Medicine Journal, 36(4), 199–201. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2018-207818

- Thadani, V., Breland, W., & Dewar, J. (2010). College instructors’ implicit theories about teaching skills and their relationship to professional development choices. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 21(2), 113–131.

- Thadani, V., Breland, W., & Dewar, J. (2015). Implicit theories about teaching skills predict university faculty members’ interest in professional learning. Learning & Individual Differences, 40, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.03.026

- Wheeldon, J., & Faubert, J. (2009). Framing experience: Concept maps, mind maps, and data collection in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800307

- Yeager, D. S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G. M., Muller, R., Crosnoe, C., Dweck, E., Tipton, C. S., Schneider, B., Hulleman, C. S., Hinojosa, C. P., Paunesku, D., Romero, C., Flint, K., Roberts, A., Trott, J., Iachan, R., Buontempo, J., Yang, S. M., Carvalho, C. M., Hahn, P. R., & Duckworth, A. L. (2019). A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature, 573(7774), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1466-y

- Zingoni, M. (2017). Motives in response to negative feedback: A policy-capturing study. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 30(3), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.21249

Appendix 1.

PRISMA diagram of search Strategy