ABSTRACT

A considerable body of research suggests that horizontal inequality between ethnic groups has major socioeconomic implications, in particular for peace and economic development. Much of this work focuses on horizontal inequality as an independent causal variable, rather than an outcome of various processes. We offer conceptual, theoretical, and empirical reasons for treating horizontal inequality as an outcome and challenging assumptions of fixity. We first consider explanations for variation drawing on the literature on horizontal inequality, as well as on ethnicity more broadly. We then explore how horizontal inequality can be measured using survey and census data, and present analysis based on two datasets providing information on inequality in terms of educational attainment (HI-E) for the 1960s to 2000s. These data suggest both a general trend toward decline in HI-E over time and considerable regional variation. This article serves also to introduce and frame the contributions to this special section.

1. Introduction

A considerable body of research in political science and economics over the past several decades has focused on the political-economic implications of ethnic divisions. On the whole, this work raises the spectre of major negative consequences – for economic development, peace and conflict, electoral politics, public goods provision, and the quality of governance (e.g. Alesina, Baqir, & Easterly, Citation1999; Easterly & Levine, Citation1997; Habyarimana, Humphreys, Posner, & Weinstein, Citation2007; Horowitz, Citation1985).Footnote1 Indeed, the negative relationship between social divisions and economic progress has been characterized as ‘one of the most powerful hypotheses in political economy’ (Banerjee, Iyer, & Somanathan, Citation2005, p. 639). Recent research suggests that it may be inequalities between ethnic groups especially that drive negative outcomes (in particular, see Baldwin & Huber, Citation2010). Research on ‘horizontal’ inequality between ethnic groups shows links, in particular, with conflict and underdevelopment (e.g. Alesina, Michalopoulos, & Papaioannou, Citation2016; Cederman, Weidmann, & Gleditsch, Citation2011; Stewart, Citation2002, Citation2008a).

A commonality in this body of work is its focus on the ‘impact’ of ethnic divisions and inequalities. While institutions and other factors are considered in order to mediate the expression and influence of such ethnic ‘structure’, it is often treated as, in effect, an independent variable that varies across countries and holds considerable stability over time. In this paper, by contrast, we consider conceptual, empirical, and theoretical bases for treating horizontal inequality as a dependent variable. This discussion points to several key areas for future research, both with respect to theory building and testing on change and variation in horizontal inequality, and to data collection that allows for – and empirically tracks – changes over time. We build here explicitly on the literature on ethnicity, as well as that on horizontal inequality. We also draw on analyses of two cross-national datasets that provide measures of horizontal inequality in terms of educational attainment for the period 1960–2010, based on census and household survey data.

In so doing, this article serves also to introduce and frame this special section. The other four studies in this collection each speak to horizontal inequality in a particular country – Brazil (Leivas & Dos Santos, Citation2018), India (Chadha & Nandwani, Citation2018), Nigeria (Archibong, Citation2018), and Guatemala (Canelas & Gisselquist, Citation2018a) – providing focused analyses of sub-national patterns, trends, influences, and consequences. While each article advances a distinct argument, each also draws on the common ‘toolkit’ of concepts and measures that are introduced here. In considering explanations for horizontal inequality, this article also reviews the arguments developed in these studies within the context of the wider research literature. Collectively, we consider these four countries particularly interesting for ‘hypothesis building’ because they offer useful variations in terms of both geographic region (Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia) and the types of ethnic groups that are salient (e.g. indigenous/non-indigenous in Guatemala, race in Brazil, caste in India, and ethnolinguistic in Nigeria) (see Eckstein, Citation1975; Lijphart, Citation1971).Footnote2

Section 2 of this paper builds on the literature to explore the concepts of horizontal inequality and ethnic identity, and to consider sources of change and variation. This section introduces conceptual and theoretical bases for treating horizontal inequality as a dependent variable and, within this context, considers two blunt predictions concerning persistence over time and systematic variation across regions. Section 3 turns to the measurement of horizontal inequality, including discussion of data. It introduces the two cross-national datasets used in this paper, which measure horizontal inequality in terms of educational attainment, and provides context on trends in educational inequality since the 1960s. Section 4 considers cross-national patterns and trends in horizontal inequality using these data. It suggests empirically why treating horizontal inequality as ‘fixed’ over decades is problematic, while situating the countries studied in this special section within a broader empirical context. Section 5 concludes.

2. Horizontal inequality and ethnicity: exploring change and variation

2.1. Key concepts

A growing body of research on inequality considers stratification not only between individuals and households, but also between groups in society, suggesting its relevance to various socioeconomic outcomes. In recent research in economics and political science, the latter are commonly referred to as ‘horizontal inequalities’ as distinguished from ‘vertical inequalities’, and defined by Stewart as ‘inequalities in economic, social, or political dimensions or cultural status between culturally defined groups’ (Citation2008b; p. 3; see also: Brown & Langer, Citation2010; Cederman et al., Citation2011; Gubler & Selway, Citation2012; Murshed & Gates, Citation2005; Østby, Citation2008). ‘Horizontal inequality’ is sometimes used interchangeably with ‘ethnic inequality’, defined for instance by Alesina as ‘within-country differences in well-being across ethnic groups’ (Citation2016, p. 1), as well as ‘between group inequality’ or ‘group-based income differences’ (Baldwin & Huber, Citation2010, p. 646). It also has close relation to other work in sociology and political science on ethnic stratification and disadvantage (e.g. Grusky, Citation1994; Kao & Thompson, Citation2003; Noel, Citation1968), ‘ranked’ and ‘unranked’ ethnic groups (e.g. Gisselquist, Citation2013; Horowitz, Citation1985), and ‘categorical’ inequalities (Tilly, Citation1999).

In this paper, we use the term ‘horizontal inequalities’ and an adapted form of Stewart’s definition, replacing ‘culturally defined’ with ‘ethnic’ groups. We prefer ‘ethnic’ because culture may also play a role in defining other types of groups, including ‘class’ groups (see, e.g. Lewis (Citation1959) on the ‘culture of poverty’ or Thompson (Citation1963) on the English working class).

‘Ethnic’ as understood here refers to a broad set of categories based on ascriptive attributes, such as skin colour, maternal language, tribe, caste, religion, and sometimes region (Chandra, Citation2004; Horowitz, Citation1985; Htun, Citation2004). This broad approach to ethnicity has become standard in the recent literature on ethnic politics, grounded in constructivist and instrumentalist frameworks (see Chandra, Citation2001; Hale, Citation2004; Varshney, Citation2007). Ethnic categories, it is clear, are social constructs (often linked with descent-based attributes) and are in this sense culturally defined. Likewise, ethnic groups tend to be associated with systems of shared meanings and beliefs; to have distinguishing cultural features, such as a common language; and to have a sense of shared history and/or connection to a ‘homeland’ – although some do not (Bates, Citation2006; Fearon, Citation2003). Adopting such an approach to ethnicity, theories of ‘ethnic’ politics address all of the following groups: African, White, ‘Coloured’, and Indian in South Africa (Ferree, Citation2010); Hindu and Muslim in India (Varshney, Citation2003); scheduled castes in India (Chandra, Citation2004); Bemba, Nyanja, Tonga, and Lozi speakers in Zambia (Posner, Citation2003); and indigenous and non-indigenous in Latin America (Van Cott, Citation2007).

While ‘ethnic’ is used more narrowly in some work – which, for instance, distinguishes between ‘ethnic’, ‘linguistic’, and ‘religious’ divisions (Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat, & Wacziarg, Citation2003) – the constructivist approach to ethnicity adopted here raises questions about the conceptual rigour with which such distinctions between ‘types’ of groups are made. At the same time, we note that some ethnic divisions may be qualitatively different from others in ways that are relevant to understanding change in horizontal inequality. For instance, ethnic categories linked to less mutable characteristics, such as skin colour could be more fixed than those related to, for example, religious affiliation or linguistic ability. Understanding better the relationship between type of group and horizontal inequality change is one area for future research.

Another area for future work on horizontal inequality as an outcome concerns intersecting inequalities, both those across broadly ‘ethnic’ groups, and others, such as across gender and location. An intersectional approach in particular speaks to the overlapping and interdependent nature of disadvantage across multiple social categories, which implies that inequality should be analyzed within a framework that takes such multiple categories into account simultaneously (see Hancock, Citation2007). In this collection, we consider multiple inequalities, including across gender and location, as well as vertical inequality, but do not focus on their intersection. Kabeer and Santos (Citation2017), for instance, offers an intersectional approach that might be built upon in future quantitative work.

Finally, it is worth underscoring that we thus define horizontal inequalities as inequalities not only across ‘ethnolinguistic’ or ‘tribal’ groups, for instance, but also across groups identified in racial, religious, caste, and regional terms. There is one caveat to this, however: in Sections 3 and 4, we are constrained in our empirical analysis by the available data. The datasets we use classify ‘ethnic’ as distinct from ‘religious’ cleavages. Reclassifying these data is beyond the scope of the analysis here, and we thus present results in these sections following the conventions used in the datasets. This suggests another area for future research and data collection.

2.2. Explaining change

Read within the context of contemporary literature on ethnic identity, the assumption of group stability implicit in the data used in some recent work on horizontal inequality is notable. In Alesina et al. (Citation2016), for instance, proxies for ethnic inequality are constructed using two datasets/maps on the location of ethnic groups, the Geo-Referencing of Ethnic Groups (GREG) dataset, based on the Atlas Narodov Mira, which provides information from the early 1960s (Weidmann, Rød, & Cederman, Citation2010), and the 15th edition of Ethnologue (Gordon & Raymond, Citation2005), which maps language groups in the mid to late 1990s. In the literature on ethnicity, by contrast, a rejection of approaches that assume decades-long fixity in ethnic boundaries has been cited as a defining characteristic of recent research (see Bates, Citation2006; Chandra, Citation2012; Hale, Citation2004; Varshney, Citation2007). To offer just a few examples, recent research demonstrates changes in ethnic identities, triggered or influenced by: the collapse of the Soviet Union (Laitin, Citation1998); the 1991 and 1992 regime transitions in Zambia and Kenya, respectively (Posner, Citation2007); and the timing of competitive presidential elections in sub-Saharan African countries relative to when individuals are asked about their identity (Eifert, Miguel, & Posner, Citation2010).

That said, it is also clear that ethnic divisions and horizontal inequality can show notable persistence over time. Indeed, classic ‘constructivist’ work describing, for instance, the emergence of ‘imagined communities’ along with print capitalism and mass vernacular literacy (Anderson, Citation1983) or of nationalism in industrial society (Gellner, Citation1983) can be consistent with considerable continuity in (ethno)national identities over time. With respect to horizontal inequality, in particular, Stewart and Langer (Citation2007) consider and summarize six factors that contribute to its persistence:

‘Unequal rates of accumulation, due to inequalities in incomes and imperfect markets.

Dependence of the returns to one type of capital on the availability of other types.

Asymmetries in social capital.

Discontinuities in returns to capital.

Present and past discrimination by individuals and non-governmental institutions.

Political inequalities leading to discrimination by governments’ (p. 12).

Given such factors contributing to ‘persistence’, much of the literature on horizontal inequality has dealt with long-ago ‘origins’. In particular, arguments highlighting the role of (1) colonialism and conquest, (2) historical institutions, and (3) geographic endowments offer explanations that speak principally to why levels of horizontal inequality – originating decades or more ago – vary across countries and regions. The literature has also explored factors that can offer explanations for more recent changes over time. We consider a further three here: (4) modernization, (5) migration and integration, and (6) the impact of contemporary government policies.

Classic work on horizontal inequality highlights in particular ‘foundational shocks’ related to colonialism, conquest, capture, and related movements of populations, including the forced migration of Africans to the New World (Stewart & Langer, Citation2008; see also Horowitz, Citation1985). As a result, Horowitz (Citation1985) suggests, we find highly stratified ethnic systems in Southern Africa and in North and South America, among other regions. If we remember that the European colonial period, for instance, can be dated from the 1400s until 1914, and that a number of African and Asian countries achieved independence after the Second World War, such work suggests divergent levels of horizontal inequality across countries and regions that trace back from decades to centuries.

A second set of arguments, often closely linked with the first, deals with the originating influence of historical institutions, in some cases pre-dating colonialism. For instance, Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (Citation2013) point to the degree of centralization of precolonial ethnic political institutions in explaining variation in contemporary economic performance across ethno-regions (‘ethnic homelands’). Their analysis draws on Murdock’s (Citation1967) index of ‘Jurisdictional Hierarchy Beyond the Local Community Level’, which differentiates stateless societies, petty chiefdoms, paramount chiefdoms, and larger states.

In this special section, Archibong (Citation2018) points both to the role of colonialism and conquest, and to precolonial institutions, in understanding contemporary horizontal inequality in Nigeria. Documenting that horizontal inequality (measured in terms of wealth, education, and access to public goods) has been ‘remarkably persistent’, she locates the roots of this inequality in differential treatment by historic (Nigerian) federal regimes in the allocation of federally administered services. This in turn is linked to their interaction with local ethnic leaders and states: in particular, the federal regime ‘punished’ centralized ethnic states that were non-compliant with or rebelled against it with underinvestment in federally administered infrastructure services. Thus, ‘being a centralized ethnic state in 1850 is likely linked to development outcomes inasmuch as it allowed centralized ethnic states to “bargain” with federal regimes for access to federally controlled services through the system of indirect rule’ (p. 7). Two periods of federal regimes are in turn highlighted, the British colonial autocracy (circa 1885–1960) and the postcolonial military autocracy (1966–99).

A third set of arguments highlights the originating role of geography in influencing horizontal inequality. For instance, Alesina et al. (Citation2016) argues that ‘to the extent that land endowments shape ethnic human capital and affect the diffusion and adoption of technology and innovation (e.g. Diamond, Citation1997), ethnic-specific inequality in the distribution of geographic features would manifest in contemporary differences in well-being across groups’ (p. 470). Geographic inequality is proxied using georeferenced data on elevation, land suitability for agriculture, distance to the coast, precipitation, and temperature.

Michalopoulos (Citation2012) locates the origins of ethnolinguistic diversity in differences in land endowments, giving rise to ‘location-specific human capital’. This argument resonates in significant ways with Barth’s (Citation1969) classic work showing how ethnic boundaries are maintained not through geographic and social isolation of groups, but through their interaction. ‘Ecologic interdependence’ may take diverse forms, with some groups occupying clearly distinct ecological niches and interdependence only in the sense of being co-resident in a particular area, while others ‘provide important goods and services for each other, i.e. occupy reciprocal and therefore different niches’ (p. 20). Ethnic stratification obtains ‘where one ethnic group has control of the means of production utilized by another group’ or ‘where groups are characterized by differential control of assets that are valued by all groups in the system’. Thus, for instance, ‘Fur and Baggara do not make up a stratified system, since they utilize different niches and have access to them independently of each other, whereas in some parts of the Pathan area one finds stratification based on the control of land, Pathans being landowners, and other groups cultivating as serfs’ (p. 27).

In this special section, Leivas and dos Santos’ (Citation2018) discussion of the roots of horizontal inequality and ethnic division in Brazil emphasizes geographic (structural) factors alongside colonial influences. They note the particular significance of two episodes during the colonial period: the sugar cane boom (1570–1760) and the gold boom (1695 until the end of the 18th century). Slave labour, a cornerstone of both episodes, ‘not only affected ethnic diversity, but also generated a historical horizontal inequality’ (p. 11). Given Brazil’s geography, it was the northeast and central regions in which emerged both high ethnic fractionalization and high horizontal inequality.

A fourth set of arguments relates to processes of modernization. While modernization theory suggests that ‘traditional’ identities would be replaced by (modern) class identities, it has long been clear that ethnic divisions remain a fact of modern societies and indeed that modernization itself may give rise to ethnic politics (see Melson & Wolpe, Citation1970). The relationship between processes of modernization and the emergence of horizontally unequal ethnic groups is likewise suggested in classic work of this era. For instance, Hechter (Citation1974) suggests that while we may often see status group (ethnic) cleavages becoming less salient with modernization, they have remained politically salient in ‘peripheral’ regions, which are ‘relatively poor and culturally subordinate’. Here, ‘the persistence of such status group political orientations among collectivities is, at least in part, a function of the salience of cultural distinctions in the distribution of resources, and, hence, in the general system of stratification’ (p. 1177). In this argument, then, modernization alongside processes of colonialism and conquest contributes to an enduring ‘cultural division of labour’. Likewise, Bates’ (Citation1974) discussion of the emergence of ethnic politics in Africa points also to the role of colonial institutions, as well as geography. In this argument, it is through competition over the ‘goods of modernity’ (e.g. jobs and education) that ‘new patterns of stratification’ emerged (p. 457). Colonial policy towards ‘tribes’ and the spatial location of groups (e.g. in relation to industry and urban centres) in turn influenced the ethnic character of this stratification.

A fifth set of arguments – which speak also to more recently emerged horizontal inequalities – relate to contemporary migration and integration.Footnote3 In general, we expect both socioeconomic inequalities and ethnic distance between migrant and ‘native’ populations to decline over time and generations. In Dahl’s (Citation1961) theory of assimilation, for instance, the relatively low socioeconomic status of new immigrants reinforces ethnic bonds. But there is considerable diversity in how this plays out, given diverse contexts of reception (government policies, labour markets, and ethnic communities) (Portes & MacLeod, Citation1996; Portes & Rumbaut, Citation1990).Footnote4 Waters’ (Citation2001) study of West Indian immigrants to the USA, for one, suggests the more ‘Americanized’ second-generation doing worse economically than the first generation.

This in turn points to a sixth set of arguments highlighting the impact of government policy on horizontal inequality. In particular, there is substantial research into the impacts of targeted efforts, such as affirmative action policies, on inequality and disadvantaged populations (see, e.g. Brown, Langer, & Stewart, Citation2012; Kalev, Dobbin, & Kelly, Citation2006; Sautman, Citation1998; Sowell, Citation2005). Conversely, we can also include here policies of ethnic favouritism that engender greater inequality (De Luca, Hodler, Raschky, & Valsecchi, Citation2018).

In this collection, Canelas and Gisselquist (Citation2018a) and Chadha and Nandwani (Citation2018) both explore how other types of policies may impact horizontal inequality. Canelas and Gisselquist (Citation2018a) consider the impact of educational and other reforms in Guatemala between 2000 and 2010 on horizontal inequality in terms of human capital and labour market outcomes. This analysis suggests both notable improvements in horizontal inequality between indigenous and non-indigenous populations over the period of study, and the persistence of significant horizontal inequalities, including between indigenous subgroups. It points to the potential of educational policies to support greater equality overall, while also suggesting the need for more targeted efforts to address the persistent disadvantages of some groups.

Chadha and Nandwani (Citation2018) document increases in horizontal inequality in India (at the district, state, and national levels) since the 1990s, and consider the relationship between ethnic fragmentation, public goods provision, and inequality. Building on the literature on ethnic fragmentation and the under-provision of public goods (e.g. Alesina et al., Citation1999; Gisselquist, Leiderer, & Niño-Zarazúa, Citation2016; Habyarimana et al., Citation2007), they consider both whether ethnic fragmentation influences horizontal inequality via a negative impact on public goods provision, and whether public goods provision positively influences inequality. Teasing out distinctions in impact on vertical and horizontal inequality, they find that while ‘overall inequality is higher in more fragmented districts’ and ‘lowered provision of public goods is the channel through which fragmentation manifests its impact’, ‘this is only true for overall inequality and not horizontal inequality’ (p. 12).

As this brief review suggests, there is considerable space in future research for further theory building and testing that speaks to horizontal inequality as an outcome variable. In broad stokes, we consider two cross-national patterns and trends suggested by the discussion above.

Our first prediction is of general stability in terms of relative horizontal inequality between countries over decades (and possibly centuries), along with a gradual trend towards greater equality. We expect general stability given in particular the factors identified by Stewart and Langer (Citation2007) that contribute to the persistence of horizontal inequality. We expect a gradual trend toward greater equality given shifts in government policies – and international norms – in particular, with respect to equality between ethnic groups. While many government policies also have clearly contributed to increases in horizontal inequality, we expect 20th century changes in policies reflecting a more equal approach to citizenship and rights, regardless of ethnicity, to generally support greater equality. We have in mind both national law and policies, such as the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the constitutional reform in support of indigenous rights undertaken in some Latin American countries in the 1990s (Van Cott, Citation2000), as well as evidence of changing international norms and practice, such as the adoption by the United Nations General Assembly of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. We consider the predicted impact of modernization and of migration and integration to be ambiguous. As we discuss above, the literature suggests modernization could lead in different contexts to either the dampening – or preservation, or emergence – of ethnic stratification, making its overall cross-national impact unclear. In terms of migration, even if we expect horizontal inequality between migrants and ‘natives’ generally to decline over time, multiple waves of migration complicate expectations with regard to overall impact.

Our second prediction is of broad variation in horizontal inequality across regions linked to diverse histories of colonialism and conquest, historical institutions, and geographic endowments – with particularly high horizontal inequality in regions marked by settler colonialism, conquest, and slavery, such as Southern Africa and the Americas. As explored above, there is a significant literature suggesting the influence of colonialism and conquest, historical institutions, and geographic endowments on the ‘origins’ of (persistent) horizontal inequalities. We thus expect variation in horizontal inequalities linked to regional variation in these factors. While precise predictions based on historical institutions and geographic endowments, however, are challenging – not least because of debate concerning what precisely about historical institutions and geographic endowments matters, and how – the literature is generally consistent with the expectation that histories of colonialism, conquest, and slavery go along with higher horizontal inequality.

3. Data and measurement

Various approaches to the measurement of horizontal inequality are developed in the literature. One set of cross-national measures has relied on geospatial estimates or proxies. Alesina et al. (Citation2016), for instance, combine data on night-time luminosity along with ethnic ‘homelands’ to construct measures, while Cederman et al. (Citation2011) combine geocoded data on ethnic group settlement areas with spatial wealth estimates. A second set of work, into which this article falls, measures from data compiled in censuses and surveys at the individual or household level.

While the former has the benefit of generally better cross-national and time series coverage, it has several major weaknesses in light of the project at hand and the literature reviewed above. The first is the strong linking of ethnic groups and homelands. This is problematic because many groups are spatially intermixed and because migration contributes to further intermixing, and can be expected to impact horizontal inequality as well. The second is the in-built assumption in focusing on historic ‘homelands’ that all salient ethnic groups have homelands and that these are relatively stable over time. A third issue is that the construct validity of such proxies simply remains as yet unproven without better microdata on horizontal inequality against which to compare them.Footnote5

As Stewart (Citation2008b) discusses, horizontal inequalities are multidimensional, including economic, social, political, and cultural dimensions. In this paper, we draw on data that speak most directly to the economic and social dimensions, focusing on horizontal inequality assessed in terms of educational outcomes (HI-E), in particular mean years of schooling. Education is a common indicator in research on horizontal inequality, but clearly does not speak to all dimensions. It has direct implications in the labour market and for social mobility and wealth. Research shows that inequality in educational outcomes is evident early in childhood and pervasive across the life cycle. Further, evidence suggests that pervasive group disparities in education mirror group disparities in socioeconomic status (see, e.g. Baliamoune-Lutz & McGillivray, Citation2015; Canelas and Gisselquist, Citation2018a; Cutler & Lleras-Muney, Citation2006; García-Aracil & Winter, Citation2006).

Our focus on education is also due to the availability of comparable data with which to consider horizontal inequality across countries and over time. While long time series on vertical inequality exist for most countries in the world, data are comparatively limited on horizontal inequality. For instance, Østby (Citation2008) and Tetteh-Baah, Harttgen, and Guenther (Citation2018) each rely on an analysis of 36 countries using data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS).Footnote6 Data gaps on horizontal inequality are not surprising, given key methodological, conceptual, and in particular political challenges that complicate the collection and use of survey and census data on topics related to ethnicity and, by extension, horizontal inequality (Canelas and Gisselquist, Citation2018b). This study draws on data from two sources based on census and survey data, which offer comparatively broad coverage across countries and over time: the Education Inequality and Conflict (EIC) dataset and the World Inequality Database on Education (WIDE).

The EIC dataset, commissioned by the UNICEF Peacebuilding, Education and Advocacy Programme, is a joint effort with the Education Policy and Data Center to advance knowledge of the relationship between horizontal education inequality and violent conflict, and the effects of investment into educational equity on peacebuilding (EIC, Citation2015). It is an unbalanced panel of countries that combines data from national censuses, DHS, and household consumption and expenditure surveys. It contains measures of horizontal inequality in the educational attainment of young people (ages 15–24) according to identified ‘ethnic’, ‘religious’, and sub-national divisionsFootnote7 for up to 111 countries from 1960 to 2010.Footnote8 The dataset also includes country–year information regarding conflict onset and duration, gross domestic product per capita, political regime, and population, among others. A detailed explanation of the mapping of ethnic groups within countries and across time, as well as on the techniques used for data extraction, back projections, and interpolation, can also be found in the EIC (Citation2015) report.

The WIDE (Citation2015) dataset, developed for UNESCO’s Education for All Global Monitoring Report, combines data from DHS, multiple indicator cluster surveys (MICS), national household surveys, and learning achievement surveys from over 160 countries at different points in time. It enables comparison of different education outcomes between countries and between groups within countries, by wealth quintile, gender, ethnicity, and location of young people (ages 20–24).

Finally, it is important to be clear that measuring horizontal inequality using data on educational attainment provides a partial view of patterns and trends. For one, there are other important indicators of inequality not analyzed here (such as wealth, income, land, and access to other public services). Moreover, the fact that years of schooling is a bounded variable, means that we expect a decline over time in inequality in years of schooling as average years of schooling increases – just as we would for other bounded variables, such as access to health services. In other words, as more individuals gain access to education, the variable becomes less concentrated in any group of the population, becoming more equitably distributed over time. Thus, while analysis of trends in educational inequalities provides important insight into horizontal inequality, we cannot generalize these findings for other variables.

3.1. Measures

A variety of group inequality measures are explored in the literature. These range from simple measures like comparison of group means to more sophisticated indexes (see for example, Atkinson, Citation1970; Das & Parikh, Citation1982; Deutsch & Silber, Citation2013; Zhang & Kanbur, Citation2005). Because our focus here is not on the development of new measures, we work in particular with three well-established measures as defined by Mancini, Stewart, and Brown (Citation2008), i.e. the GGini, GTheil, and GCOV (the group- weighted coefficient of variation) (see also Stewart, Citation2008a). We also consider changes in relative dispersion of education across countries over time. Each of the horizontal inequality measures is calculated as follows:

where y is the variable of interest, i.e. mean years of schooling, ȳ its mean value, R the number of groups with r and s two different groups of the population, and p the group’s population share.

The GGini based on mean years of schooling compares every group with every other group (as opposed to calculating the difference from the mean) and, in our case, it can be interpreted as a measure of how concentrated the total stock of education is in one group. The GTheil compares each group’s mean in educational attainment with the national mean. In doing so, it is especially sensitive to the lower end of the distribution. The GCOV is a measure of overall dispersion and therefore changes on this index can be interpreted as occurring at all levels of the distribution. However, since it is based on squared deviations, outliers are given greater weight than the values in the middle of the distribution.

Aggregate measures of HIs are particularly useful in situations where there are a larger number of groups in the population and direct comparison of simple means is not straightforward. The three measures cited above have been chosen based on the analysis of Mancini et al (Citation2008) on the main principles of a good measure of inequality.Footnote9

In inequality analysis, either vertical or horizontal, it is important to apply several measures, since different indices can generate different trends and thus a single measure of inequality may produce misleading results. Indeed, by construction, every measure is unique. Different value judgments underlie every measure. For instance, the GCOV gives more weight to observations further from the mean and the Gini to observations in the middle of the distribution. Also, while the coefficient of variation is easy to understand, there are several concerns about the intuitive appeal of the Theil index. And, as Mancini et al. (Citation2008) point out with respect to horizontal inequalities, ‘no intuitive understanding has built up of the group Gini either, because of the lack of experience in interpreting it’ (p. 89). Thus, in order to present a complete picture of inequality from different angles, at different points of the distribution, and over time, using the three measures seems appropriate.

The contributors to this special section have taken these measures as a starting point in their analyses. They also were asked to consider several additional measures, including ‘crosscuttingness’ (Rae & Taylor, Citation1970; Selway, Citation2011), ethnic fractionalization (Taylor & Hudson, Citation1972), and ethnic polarization (Montalvo & Reynal-Querol, Citation2005). Selected studies in this collection further explore additional measures. Archibong (Citation2018), for instance, adapts McKenzie’s (Citation2005) inequality coefficient. Footnote10

3.2. Educational attainment

It is useful to consider HI-E within the broader context of educational attainment since the 1960s. displays the trend in educational attainment, in five-year intervals, during 1960 – 2010 for all countries in the EIC dataset grouped by geographic region. For comparison, we also provide the same figures based on the Barro and Lee (Citation2013) and Jordá and Alonso (Citation2017) datasets (see Appendix).

Figure 1. Regional trend in educational attainment.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the EIC dataset.

The first point to notice is that, on average, educational attainment has increased since the 1960s throughout the world. This is clear in the EIC dataset, as well as the Barro and Lee (Citation2013) and Jordá and Alonso (Citation2017) datasets. However, despite this positive trend, persistent differences in mean years of schooling exist across world regions, notably in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, which are consistently below the world average.

It is also useful to consider HI-E between ethnic groups alongside inequality between other types of groups. Using the WIDE dataset, shows the average years of schooling for the countries studied in depth in this special section, for specific years and by different population subgroups. Table A.1 in the Appendix shows values for other countries in the data with relatively big gaps in educational attainment, in similar years.

Table 1. Average years of schooling by population subgroup, selected countries.

For most countries in the data, the greatest educational inequalities are geographic – that is, between urban and rural populations, and across sub-national regions – as well as across wealth quintiles. Clearly, ethnicity, geographic location, and wealth can be deeply intertwined. These interconnections are considered in several of the studies in this special section and call for further unpacking in future work.

The data suggest that while the educational disparity between urban and rural areas has generally decreased over time, a gap in mean years of schooling has remained persistent. In Nigeria, for instance, the country with the highest difference in mean years of schooling between groups in the sample, the mean years of schooling in 2013 was 5.77 years in rural areas, compared with 10.37 years in urban areas. Further, in spite of overall increases in educational attainment, the gap in mean years of schooling has increased over time. (In 2003, the relevant means were 5.43 and 9.01 years, respectively; DHS, age group 20–24 years.) A similar pattern is found when looking at within-country regional disparities, which in the case of Nigeria are stronger than the usual urban–rural divide (see Archibong, Citation2018).

Unsurprisingly, the data show a clear relationship between wealth quintile and educational attainment: individuals in higher wealth quintiles have higher average educational attainment. However, there is also notable variation across world regions. Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest difference in mean years of schooling between the lowest and highest wealth quintiles and Nigeria the largest educational gap, followed closely by Ethiopia. The same pattern as above is observed, with an increasing gap in mean years of schooling over time. In Nigeria, in 2013, mean years of schooling in the lowest wealth quintile is just 1.73 years, compared with 12.7 years in the wealthiest quintile (see ). In Ethiopia, in 2011, averages were 1.55 and 8.58 years, respectively.

Educational attainment also varies by gender. Across regions, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest difference in mean years of schooling; however, the country with the highest gap in educational attainment is now in South Asia (Afghanistan). While the gender gap in educational attainment has reduced significantly over the years, some differences persist, notably in these two regions. According to WIDE data for Afghanistan in 2015, for 20–24-year-olds, there was an educational gap of 3.56 years in favour of men. Afghanistan is closely followed by Guinea and Benin.

In other regions of the world, educational inequality between genders is lower due to both the vast educational expansion that took place in the past decades and active gender equity promotion. In Latin America, for instance, female educational attainment is on average higher than that of males; however, this gain has not yet been translated into lower inequalities in other socioeconomic spheres, such as the labour market, domestic production, and political representation (see Campana et al., Citation2018; Canelas & Salazar, Citation2014; Carrillo, Gandelman, & Robano, Citation2014).

4. Results: HI-E patterns and trends

This section presents trends in horizontal inequality in educational attainment (HI-E) across what the EIC dataset identifies as ‘ethnic’ and ‘religious’ cleavages. We present the results at the regional level. The Appendix provides a disaggregated list of countries grouped by region.

Before going into the details of the results, it is useful to look at the simple correlation among the HI-E measures. presents the correlation coefficients between all three HI-E measures used in this study for the EIC’s ‘ethnic’ and ‘religious’ cleavages. The correlations between all the measures are significant at the 1 per cent level and very high, although there is some variation on the strength of the relationship, in particular within countries (not shown in the tables). The strongest correlations at the regional level are between the GGini and the GCOV for both ethnic and religious cleavages, while the lowest correlation is between the GTheil and the GCOV for ethnic groups, and between the GGini and the GTheil for religious groups. Given the strength of the correlation, most of the analysis below relies on the GGini, but when needed we also present the results for the other measures.

Table 2. Correlations of different measures of horizontal inequality.

4.1. Trends over time

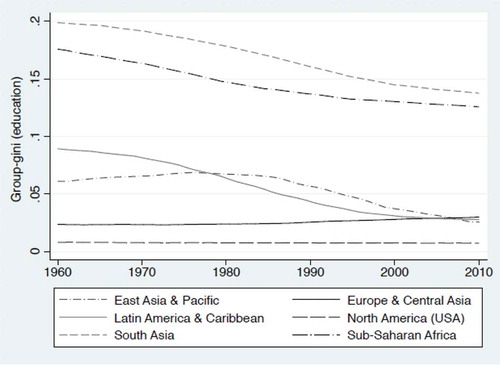

shows average schooling years and education GGini coefficients by ethnic groups for 73 countries for 1960–2010. A declining trend in HI-E can be observed alongside an increasing level of educational attainment during the period. For all countries together, the average GGini declined from 0.12 in 1965 to 0.08 in 2005 (5-year intervals), suggesting an increasingly equal distribution of education over time. This is broadly consistent with the first prediction outlined in Section 2.2. In the context of the six sets of factors considered above, we expect this is due in part to contemporary government policies reflecting a more equal approach to citizenship and rights, and more attention to ethnic discrimination, as well as various efforts over this period specifically to improve educational access by disadvantaged populations. In addition, given in particular that we measure inequality in terms of years of schooling, we posit the influence of ‘modernization’ in supporting an increase in average educational attainment, and thus, given the bounded nature of this variable, some decline in inequality measured in these terms.

4.2. Patterns and trends across countries and regions

Significant geographic dispersion in HI-E over time also can be observed in and . South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have relatively higher HI-E GGini coefficients, suggesting greater inequality in the distribution of educational attainment between ethnic groups in those regions. For instance, in 2005, the 5-year average GGini coefficient by ethnic groups in North America (USA) was 0.001, while in South Asia it was 0.14.

Table 3. Horizontal inequality measures by ethnic groups.

Figure 3. Horizontal inequalities by ethnic groups.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the EIC dataset.

In terms of ‘religious’ groups as identified in our data, HI-E also declined during the period under study, in particular for East Asia.Footnote11 For the other world regions, HI-E between religious groups has remained relatively low over time. Interestingly, in Latin America, HI-E between ethnic groups, gender groups, and sub-national regions is large (see Feranti, Perry, Ferreira, & Walton, Citation2004), but HI-E between religious groups has been traditionally low and constant over time (). This is true for all three measures employed: GTheil, GGini, and GCOV (see Appendix for details).

Figure 4. Horizontal inequalities by religious groups.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the EIC dataset.

To explore overall changes in the relative dispersion of education from 1960 to 2005, we calculate the percentage change in the three measures of horizontal inequality used in this study. As shown in , all three measures yield rather similar results in terms of ranking. The most significant reduction in HI-E over the period, when comparing regions, occurred in Latin America, where the regional average GGini by ethnic groups decreased by roughly 72 per cent, from 0.09 in the 1960s to 0.02 in the 2000s. At the country level (not shown in the tables), the largest reduction occurred in Mexico (roughly 94 per cent between 1965 and 2000), closely followed by Vietnam (90 per cent), the Democratic Republic of Congo (80 per cent), and South Africa (80 per cent), all between 1965 and 2005.

Table 4. Changes in horizontal inequalities, 1960–2005.

The regional variation in HI-E discussed here is partially consistent with our second prediction, but we find no evidence that HI-E is highest in regions marked by settler colonialism, conquest, and slavery. In fact, whether we look at ‘ethnic’ or ‘religious’ disparities as identified in our data, Southern Africa and the Americas, together or in two groups, rank second or third and fourth, after South Asia and all the other African countries in terms of HI-E.Footnote12 Figures A.4–A.7 in the Appendix show trends for HI-E for ethnic and religious groups.

This point requires further consideration. In particular, we suspect that this lack of evidence may be due to the ethnic categories considered in each country within the data used here and our focus on educational attainment. We expect that the persistent legacies of colonialism and conquest would better be seen in comparison of inequalities between ‘indigenous’ and ‘non-indigenous’ and ‘African’ versus ‘European’ descent populations in terms of wealth and land holdings in particular.

5. Conclusion

A considerable body of research suggests that horizontal inequality between ethnic groups has major socioeconomic implications, including for peace and economic development. Much of this work effectively treats horizontal inequality as an independent causal variable, rather than an out- come of various processes. In so doing, it sits uncomfortably with a large body of research on ethnicity demonstrating the constructed nature of ethnic groups. If ethnic groups are not fixed and require explanation, so too does horizontal inequality. Horizontal inequality may change not only due to changes in average group levels of economic, social, political, and cultural status or well-being, but also due to changes in the composition and boundaries of the salient groups themselves. Indeed, it may also be that ‘ethnic’ boundaries between groups weaken as inequalities decline.

In this article, we consider explanations for variation in horizontal inequalities across countries and over time, highlighting six sets of factors in particular. The first three deal with ‘origins’ due to (1) colonialism and conquest, (2) historical institutions, and (3) geographic endowments. Levels of horizontal inequality, once set, are then expected in these arguments to be persistent. The latter three sets of factors speak to influences on more recent change over time: (4) modernization, (5) migration and integration, and (6) contemporary government policies. We further explore how horizontal inequality can be measured using survey and census data and draw on two relatively new datasets providing information on inequality in terms of educational attainment for selected groups classified as ‘ethnic’ and ‘religious’. These data suggest both a general trend towards a decline in HI-E over time between the 1960s and 2000s, and considerable regional variation. We posit that these trends can be understood both in terms of contemporary shifts in government policies in support of greater social inclusion, and worldwide improvements in educational access, which – in most regions – have influenced not only equality between ethnic groups, but also between other population subgroups (sub-national regions, urban–rural divides, gender, and even wealth quintiles). Nevertheless, substantial group-based inequalities remain – particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

Broadly, then, the HI-E data we analyze are consistent with expectations both of substantial regional variation – likely linked with variant histories of colonialism and conquest, historical institutions, and geographic endowments – and a trend towards greater equality. Notably, however, there is little evidence – at least in these data – for our prediction based on the literature of particularly high horizontal inequality in either Southern Africa or the Americas as compared to the rest of the world. This latter finding requires further consideration, especially taking into account other indicators of inequality, such as wealth and land holdings.

In short, in this article we offer conceptual, theoretical, and empirical reasons for treating horizontal inequality as a dependent variable and questioning assumptions of fixity. In so doing, this article serves also to introduce and frame this special section. The other four studies in this collection each speak to horizontal inequality in a particular country, providing a focused look – using survey and census data – into patterns, trends, correlates, and implications of horizontal inequality at sub-national levels.

In terms of future research, this article and the collection as a whole suggest first that there is a need for further work on data that allow for – and empirically track – changes in horizontal inequality over time, both at national and sub-national levels. There are indeed challenges and limits to the sort of data that can be compiled on ethnicity in surveys and censuses, but much more can be done in terms of reanalysis of existing surveys and censuses, new data collection, and innovative approaches to measurement (Canelas and Gisselquist, Citation2018b).

A second implication is that much more attention should be paid in future work to theory building and testing with respect to change in horizontal inequality – especially change over the short to medium term. For instance, in the area of migration, what are the key factors influencing the evolution of inequality between migrants and ‘native’ populations over years and generations? Why are migrants and their descendants better integrated economically in some societies? What policies and institutions support greater equality and integration at the national and local levels? In terms of government policy, there is substantial research into affirmative action and disadvantaged populations, but less work into how other types of programmes and policy instruments affect horizontal inequality. The impact of development interventions to reduce poverty, for instance, is generally analyzed in terms of individuals and households, with relatively little attention to impacts on groups (Gisselquist, Citation2018). More broadly, there is considerable space for exploring other explanatory factors. In particular, as we look to the future, focused consideration of the impact of economic globalization on horizontal inequality – including factors that mediate impact – should be a priority for research and policy (see, e.g. Bormann, Cederman, Pengl, & Weidmann, Citation2016; Chua, Citation2002; Thomas & Clarke, Citation2013).

Appendix

Download PDF (341.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. A growing body of research challenges these negative expectations (e.g. Birnir, Citation2007; Chandra, Citation2005; Gisselquist et al., Citation2016; Singh & Vom Hau, Citation2016).

2. This collection is part of a broader research initiative, ‘Group-based Inequalities: Patterns and Trends Within and Across Countries’, which is supported by UNU-WIDER under its 2014–18 research programme as part of the project on ‘Disadvantaged Groups and Social Mobility’.

3. Migration is also closely interlinked with the influence of colonialism and conquest – as Stewart and Langer (Citation2008) note, the roots of horizontal inequalities can also be found in movements of people ‘from the imperial power, but also the movement of indentured labour from one part of the world to another’ (p. 79).

4. For instance, these four studies of Vietnamese refugees in Canada, Germany, the UK, and the USA suggest diverse patterns both across and within countries: Bankston and Zhou (Citation2018); Barber (Citation2018); Bösch and Su (Citation2018); Hou (Citation2017).

5. For an opposing case in favour of spatial datasets over survey-based methods, see Cederman et al. (Citation2011, p. 483).

6. One of the objectives of the research initiative of which this special section is a part was to investigate data gaps. It involved both research into available large-N datasets on horizontal inequalities and focused studies on a set of 15 selected countries.

7. In measuring ethnic and religious inequality, the EIC dataset is limited to countries with more than one ethnic and religious group. It also establishes a minimum cut-off, requiring groups to be at least 5 per cent of the population.

8. The dataset contains inequality measures among identity groups defined by ethnicity for 73 countries and defined by religion for 84 countries.

9. For a discussion of the five principles see Mancini et al (Citation2008).

10. Note that the EIC dataset contains considerably fewer countries than the Barro and Lee (Citation2013) and Jordá and Alonso (Citation2017) datasets.

11. Note that in the 1990s, Thailand (1990), Malaysia (1991), and Indonesia (1995) left the sample.

12. The ethnic HI-E includes available Southern African (Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) and American countries (all Latin American and Caribbean countries in the dataset, along with the USA). The religious HI-E includes also Lesotho and Swaziland, but not the USA.

References

- Alesina, A., Baqir, R., & Easterly, W. (1999). Public goods and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(4), 1243–1284.

- Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 155–194.

- Alesina, A., Michalopoulos, S., & Papaioannou, E. (2016). Ethnic Inequality. Journal of Political Economy, 124(2), 428–488.

- Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

- Archibong, B. (2018). Historical origins of persistent inequality in Nigeria. Oxford Development Studies, 1–23. doi:10.1080/13600818.2017.1416072

- Atkinson, A. B. (1970). On the measurement of inequality. Journal of Economic Theory, 2(3), 244–263.

- Baldwin, K., & Huber, J. D. (2010). Economic versus cultural differences: Forms of ethnic diversity and public goods provision. American Political Science Review, 104(4), 644–662.

- Baliamoune-Lutz, M., & McGillivray, M. (2015). The impact of gender inequality in education on income in Africa and the Middle East. Economic Modelling, 47, 1–11.

- Banerjee, A., Iyer, L., & Somanathan, R. (2005). History, social divisions, and public goods in Rural India. Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2–3), 639–647.

- Bankston, C. L., & Zhou, M. (2018). involuntary migration, context of reception, and social mobility: The case of vietnamese refugee resettlement in the United States. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2018/14. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

- Barber, T. (2018). The integration of vietnamese refugees in London and the UK: Fragmentation, complexity, and in/visibility”. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2018/2. Helsinki: UNU- WIDER.

- Barro, R. J., & Lee, J. W. (2013). A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010ʹ. Journal of Development Economics, 104, 184–198.

- Barth, F. (1969). Ethnic groups and boundaries. Prospect Heights, NY: Waveland Press.

- Bates, R. (1974). Ethnic competition and modernization in contemporary Africa. Comparative Political Studies, (January), 457–483.

- Bates, R. H. (2006). Ethnicity. In D. A. Clark (Ed.), The elgar companion to development studies (pp. 167–173). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Birnir, J. K. (2007). Ethnicity and electoral politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bormann, N.-C., Cederman, L.-E., Pengl, Y., & Weidmann, N. B. (2016). Globalization, exclusion, and ethnic inequality. Retrieved from http://unige.ch/sciences-societe/speri/files/6014/5294/5374/Yannick_Pengl_-_BCPW_Ethnic_Inequality_Geneva.pdf.

- Bösch, F., & Su, P. H. (2018). Invisible, successful, and divided: Vietnamese in Germany Since the Late 1970s. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2018/15. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

- Brown, G., Langer, A., & Stewart, F. (Ed.). (2012). Affirmative action in plural societies: International experiences. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brown, G. K., & Langer, A. (2010). Horizontal inequalities and conflict: A critical review and research agenda. Conflict, Security & Development, 10(1), 27–55.

- Campa Na, J. C., Giménez-Nadal, J. I., & Molina, J. A. (2018). Gender norms and the gendered distribution of total work in Latin American households. Feminist Economics, 24(1), 35–62.

- Canelas, C., & Gisselquist, R. M. (2018a). Human capital, labour market outcomes, and horizontal inequality in Guatemala. Oxford Development Studies, 1–20. doi:10.1080/13600818.2017.1388360

- Canelas, C., & Gisselquist, R. M. (2018b). Horizontal inequality and data challenges. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-018-1932-1

- Canelas, C., & Salazar, S. (2014). Gender and ethnic inequalities in LAC countries. IZA Journal of Labor and Development, 3(1), 18.

- Carrillo, P., Gandelman, N., & Robano, V. (2014). Sticky floors and glass ceilings in Latin America. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 12(3), 339–361.

- Cederman, L.-E., Weidmann, N. B., & Gleditsch, K. S. (2011). Horizontal inequalities and Ethnonationalist civil war: A global comparison. American Political Science Review, 105(3), 478–495.

- Chadha, N., & Nandwani, B. (2018). Ethnic fragmentation, public good provision and inequality in India, 1988–2012. Oxford Development Studies, 1–15. doi:10.1080/13600818.2018.1434498

- Chandra, K. (2001). Cumulative findings in the study of ethnic politics: Constructivist findings and their non-incorporation. APSA-Comparative Politics Newsletter, 12(1), 7–11.

- Chandra, K. (2004). Why ethnic parties succeed: Patronage and ethnic head counts in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chandra, K. (2005). Ethnic parties and democratic stability. Perspectives on Politics, 3(2), 235–252.

- Chandra, K. (Ed.). (2012). Constructivist Theories of ethnic politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chua, A. (2002). World on fire: How exporting free market democracy breeds ethnic hatred and global instability. New York: Doubleday.

- Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2006). Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence. Working Paper 12352. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Dahl, R. A. (1961). Who Governs? Democracy and power in an American City. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Das, T., & Parikh, A. (1982). Decomposition of inequality measures and a comparative analysis. Empirical Economics, 7(1), 23–48.

- De Luca, G., Hodler, R., Raschky, P. A., & Valsecchi, M. (2018). Ethnic favoritism: An axiom of politics? Journal of Development Economics, 132, 115–129.

- Deutsch, J., & Silber, J. (Eds.). (2013). The measurement of individual well-being and group inequalities: Essays in memory of Z.M. Berrebi. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Diamond, J. (1997). Guns, germs, and steel: The fates of human societies. New York: Norton.

- Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (1997). Africa’s growth tragedy: Policies and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1203–1250.

- Eckstein, H. (1975). Case study and theory in political science, volume VII. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- EIC. (2015). Education inequalities and conflict database. Washington, DC: Education Policy and Data Center.

- Eifert, B., Miguel, E., & Posner, D. N. (2010). Political competition and ethnic identification in Africa. American Journal of Political Science, 54(2), 494–510.

- Fearon, J. D. (2003). Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 195–222.

- Feranti, D., Perry, G., Ferreira, F., & Walton, M. (2004). Inequality in Latin America: Breaking with history? Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Ferree, K. E. (2010). Framing the race in South Africa: The political origins of racial census elections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- García-Aracil, A., & Winter, C. (2006). Gender and ethnicity differentials in school attainment and labor market earnings in ecuador. World Development, 34(2), 289–307.

- Gellner, E. (1983). Nations and nationalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Gisselquist, R. M. (2013). Ethnic politics in ranked and unranked systems: An exploratory analysis. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 19(4), 381–402.

- Gisselquist, R. M. (2018). Legal empowerment and group-based inequality. The Journal of Development Studies, 1–15. doi:10.1080/00220388.2018.1451636

- Gisselquist, R. M., Leiderer, S., & Niño-Zarazúa, M. (2016). Ethnic heterogeneity and public goods provision in Zambia: Evidence of a subnational “diversity dividend”. World Development, 78, 308–323.

- Gordon, J., & Raymond, G. (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the world (15th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International.

- Grusky, D. B. (Ed.). (1994). Social stratification: Class, race, and gender in sociological perspective. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Gubler, J. R., & Selway, J. S. (2012). Horizontal inequality, crosscutting cleavages, and civil war. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 56(2), 206–232.

- Habyarimana, J., Humphreys, M., Posner, D. N., & Weinstein, J. M. (2007). Why does ethnic diversity undermine public goods provision? American Political Science Review, 101(4), 709–725.

- Hale, H. E. (2004). Explaining Ethnicity. Comparative Political Studies, 37(4), 458–485.

- Hancock, A.-M. (2007). When multiplication doesn’t equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a research paradigm. Perspectives on Politics, 5(1), 63–79.

- Hechter, M. (1974). The political economy of ethnic change. American Journal of Sociology, 79(5), 1151–1178.

- Horowitz, D. L. (1985). Ethnic groups in conflict. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hou, F. (2017). The resettlement of vietnamese refugees across Canada over three decades. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2017/188. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

- Htun, M. (2004). Is gender like ethnicity? The political representation of identity groups. Perspectives on Politics, 2(3), 439–458.

- Jordá, V., & Alonso, J. M. (2017). New estimates on educational attainment using a continuous approach (1970–2010). World Development, 90, 281–293.

- Kabeer, N., & Santos, R. (2017). Intersecting inequalities and the sustainable development goals: Insights from Brazil. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2017/167. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

- Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelly, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. American Sociological Review, 71(4), 589–617.

- Kao, G., & Thompson, J. S. (2003). Racial and ethnic stratification in educational achievement and attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 29(1), 417–442.

- Laitin, D. D. (1998). Identity in formation: The Russian-Speaking populations in the new abroad. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Leivas, P. H. S., & Dos Santos, A. M. A. (2018). Horizontal inequality and ethnic diversity in Brazil: Patterns, trends, and their impacts on institutions. Oxford Development Studies. doi:10.1080/13600818.2017.1394450

- Lewis, O. (1959). Five families: Mexican case studies in the culture of poverty. New York: BasicBooks.

- Lijphart, A. (1971). Comparative politics and the comparative method. The American Political Science Review, 65(3), 682–693.

- Mancini, L., Stewart, F., & Brown, G. K. (2008). Approaches to the measurement of horizontal inequalities. In F. Stewart (Ed.), Horizontal inequalities and conflict: Understanding group violence in multiethnic societies (pp. 85–105). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McKenzie, D. (2005). Measuring Inequality with asset indicators. Journal of Population Economics, 18, 229–260.

- Melson, R., & Wolpe, H. (1970). Modernization and the politics of communalism: A theoretical perspective. American Political Science Review, 64(4), 1112–1130.

- Michalopoulos, S. (2012). The origins of ethnolinguistic diversity. American Economic Review, 102(4), 1508–1539.

- Michalopoulos, S., & Papaioannou, E. (2013). Pre-colonial ethnic institutions and contemporary african development. Econometrica, 81(1), 113–152.

- Montalvo, J., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2005). Ethnic polarization, potential conflict, and civil wars. American Economic Review, 95(3), 796–816.

- Murdock, G. P. (1967). Ethnographic Atlas. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Mushed, S.M., and S. Gates (2005). ‘Spatial–horizontal inequality and the maoist insurgency in Nepal’. Review of Development Economics, 91, 121–134.

- Noel, D. L. (1968). A theory of the origin of ethnic stratification. Social Problems, 16(2), 157–172.

- Østby, G. (2008). Polarization, horizontal inequalities and violent civil conflict. Journal of Peace Research, 45(2), 143–162.

- Portes, A., & MacLeod, D. (1996). Educational progress of children of immigrants: The roles of class, ethnicity, and school context. Sociology of Education, 69(4), 255–275.

- Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (1990). Immigrant America: A portrait. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Posner, D. N. (2003). The colonial origins of ethnic cleavages: The case of linguistic divisions in Zambia. Comparative Politics, 35(2), 127–146.

- Posner, D. N. (2007). Regime change and ethnic cleavages in Africa. Comparative Political Studies, 40(11), 1302–1327.

- Rae, D. W., & Taylor, M. (1970). The analysis of political cleavages. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Sautman, B. (1998). Preferential policies for ethnic minorities in China: The case of xinjiang. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 4(1–2), 86–118.

- Selway, J. S. (2011). The measurement of cross-cutting cleavages and other multidimensional cleavage structures. Political Analysis, 19(1), 48–65.

- Singh, P., & Vom Hau, M. (2016). Ethnicity in time: Politics, history, and the relationship between ethnic diversity and public goods provision. Comparative Political Studies, 49, 1303–1340.

- Sowell, T. (2005). Affirmative action around the world: An empirical study. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Stewart, F. (2002). Horizontal inequality: A neglected dimension of development’. WIDER annual lecture 005. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

- Stewart, F. (Ed.). (2008a). Horizontal inequalities and conflict: Understanding group violence in multiethnic societies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stewart, F. (2008b). Horizontal inequalities and conflict: An introduction and some hypotheses. In F. Stewart (Ed.), Horizontal inequalities and conflict: Understanding group violence in multiethnic societies (pp. 3–24). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stewart, F., & Langer, A. (2007). Horizontal inequalities: Explaining persistence and change. Report. Oxford: Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity (CRISE), University of Oxford.

- Stewart, F., & Langer, A. (2008). Horizontal inequalities: Explaining persistence and change. In F. Stewart (Ed.), Horizontal inequalities and conflict: Understanding group violence in multiethnic societies (pp. 54–82). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Taylor, C., & Hudson, M. (1972). World handbook of political and social indicators. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Tetteh-Baah, S., Harttgen, K., & Guenther, I. (2018). Inequality of opportunities in Africa. Working Paper. Zurich: ETH.

- Thomas, D. A., & Clarke, M. K. (2013). Globalization and race: Structures of inequality, new sovereignties, and citizenship in a Neoliberal era. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 305–325.

- Thompson, E. P. (1963). The making of the english working class. London: Victor Gollancz.

- Tilly, C. (1999). Durable inequality. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Van Cott, D. L. (2000). The friendly liquidation of the past: The politics of diversity in Latin America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Van Cott, D. L. (2007). From movements to parties in Latin America: The evolution of ethnic politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Varshney, A. (2003). Ethnic conflict and civic life: Hindus and Muslims in India. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Varshney, A. (2007). Ethnicity and Ethnic Conflict. In C. Boix & S. C. Stokes (Eds.), The oxford handbook of comparative politics (pp. 274–294). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Waters, M. C. (2001). Black identities: West Indian immigrant dreams and American realities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Weidmann, N. B., Rød, J. K., & Cederman, L.-E. (2010). Representing ethnic groups in space: A new dataset. Journal of Peace Research, 47(4), 491–499.

- WIDE. (2015). World inequality database on education. Global Education Monitoring Report. Paris: UNESCO.

- Zhang, X., & Kanbur, R. (2005). Spatial inequality in education and health care in China. China Economic Review, 16(2), 189–204.