ABSTRACT

This study explores the entrepreneurial potential of the rule-breaking practices of microfinance programs’ beneficiaries. Using the storyboard methodology, we examine the strategies employed by the poor in Burundi to bypass institutional rules. Based on 66 short interviews conducted in seven rural provinces of Burundi, our exploratory study analyzes the entrepreneurial potential in four instances of rule-evasion: consumption spending, illegitimate investment, loan juggling and loan arrogation. We argue that some of the unruly practices are in fact entrepreneurial, as they create tangible and intangible value for the rural poor at both household and community levels. These include strengthening social ties through gift exchange and ceremonies, which then help poor households to self-insure against shocks through social networks. By analyzing the push and pull factors for unruly behavior, we show that rule-breaking practices are often necessitated by the microfinance industry itself and call for increased flexibility and adaptability of microfinance products.

1. Introduction

The practice of rule-breaking by development programs’ beneficiaries conjures up the image of institutional disobedience, bold defiance and disregard for organizational discipline. In the field of microfinance, unruly behavior of the clients (e.g. consumption spending), tends to be regarded by program managers as a peripheral implementation problem, symptomatic of loan monitoring inefficiency. Unruly practices turn out to be much more widespread than one would expect, raising the question of why principally impoverished populations turn against the institutions that had been specifically tailored to cater to their needs (Attanasio, Augsburg, De Haas, Fitzsimons, & Harmgart, Citation2015; Bylander, Citation2015; Karlan & Zinman, Citation2012).

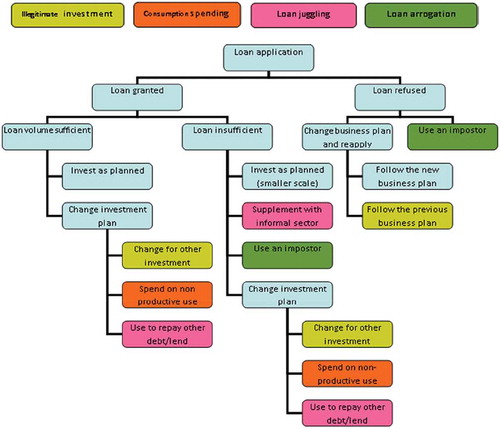

This article draws on the organizational management theory that conceives rule-breaking as a central element of the entrepreneurial process (Anderson & Smith, Citation2007). We understand rule-breaking, or unruly behavior, as a refusal to conform to the normative expectations of institutions (Zhang & Arvey, Citation2009). In the context of microfinance, it comprises activities, strategies and investments that are not allowed by the regulations of a given microfinance program. The most common cases entail consumption spending, illegitimate investment, loan juggling and loan arrogation (using a substitute lender to increase one’s loan volume) (Guérin, Citation2012; Guérin, Roesch, Venkatasubramanian, & D’Espallier, Citation2012; Karim, Citation2008; Shakya & Rankin, Citation2008) ().

Table 1. Unruly practices – overview.

Based on field data from Burundi, this paper examines the strategies employed by the poor to evade institutional rules. We present the results of an exploratory, qualitative study, entailing 66 short interviews conducted in seven rural provinces of Burundi. With the use of storyboard methodology, we describe and analyze these unruly tactics, reconstructing the reasoning that guided the perpetrators. We argue that some rule-breaking practices are the articulation of a nascent entrepreneurial orientation, as they create tangible and intangible value at both household and community levels.

Since its origins, microfinance has been acclaimed for boosting the assumed entrepreneurial propensity of the poor (Collins, Morduch, Rutherford, & Ruthven, Citation2009). At the same time, because of the high costs of developing new products and services, microfinance institutions (MFIs) rely on standardized procedures regardless of the sociocultural context in which they operate. This fosters trespassing and rule-evasion, as the clients attempt to maximize the value output and bend the institutional regulations to adapt them to their needs. The results of our study allow us to reframe rule-breaking practices as necessitated by the industry itself: because household and business activities are interrelated, microfinance’s emphasis on productive loans for business creation only partially meets the clients’ needs for financial services (Collins et al., Citation2009; Nourse, Citation2001). Accordingly, some cases of rule-evasion are in fact instances of an entrepreneurial effort to complement formal financing with more flexible, kinship-based, informal dealings. This is in line with the theory of ‘entrepreneurial bricolage’: when faced with resource constraints, entrepreneurs make do by ‘applying combinations of the resources at hand to new problems and opportunities’ (Baker & Nelson, Citation2005, p. 333). This paper provides compelling evidence that group participation, maintaining relationships and strengthening kindship-based reciprocity are considered as equally value-creating as economic growth measured with household indicators (Guyer, Citation1981; see also Goodman, Citation2017).

2. Microfinance clients as entrepreneurs, households as enterprises

When accounting for the commercialization of the microfinance sector, Fernando observes that MFIs have frequently superimposed entrepreneurial identities onto poor, rural populations (Citation2006). Over the past 30 years, the microfinance industry has switched from viewing its target beneficiaries as passive recipients to empowered subjects: ‘the new entrepreneurs’ (Fernando, Citation2006, p. 17). However, the extent to which microfinance clients embrace this entrepreneurial identity varies significantly across contexts. For example, Huiskamp and Hartmann-Mahmud (Citation2007) argue that women microfinance clients are fully capable of actively developing business plans and then putting them into action; which they find highly entrepreneurial. Also, Bruton, Khavul, and Chavez (Citation2011, p. 10) find that borrowers ‘understand the risk and reward trade-offs that microloans present, and focus on value generation’, which is indicative of highly entrepreneurial behavior. Contrastingly, Banerjee and Duflo (Citation2006) provide evidence that the poor intentionally refrain from maximizing their profits, exhibiting an anti-entrepreneurial attitude (see also Guérin, Kumar, & Agier, Citation2013). A study of Nepalese microfinance by Shakya and Rankin (Citation2008) also reveals that clients routinely contest their entrepreneurial identities by engaging in subversive and evasive practices.

The mixed evidence provided by these studies emphasizes that MFIs’ procedures do not necessarily take into account the local context (Bylander, Citation2015). As financial, though mission driven, organizations, MFIs pursue value creation via increasing the economic capacity of individual households. Each of these households is assumed to be a microenterprise whose well-being depends largely on the entrepreneurial abilities of the members to manage debt and increase savings (Bernard, De Janvry, & Sadoulet, Citation2010). At the same time, the microfinance model overlooks the fact that households are not enterprises, but essentially families, a characteristic that often manifests itself in the impossibility of separating consumptive and productive expenditures (Collins, Citation2008; Collins et al., Citation2009). While profit generation and financial viability are indicative of value creation for enterprises, they do not necessarily imply the same for households. If, however, we do equate households with ‘family enterprises’, we should also admit that breaking the rules to self‐insure consumption against health shocks is just as entrepreneurial as hedging a business against productivity loss or asset failure. When assessing a practice, we must take into consideration sociocultural conditions that contradict regulatory systems, together with the individual factors that underlie persistent divergence from norms. In the next section, we scrutinize what constitutes a ‘productive loan’ from the point of view of the MFIs and discuss the contested definition of value.

3. Norms, rules and values in microfinance

3.1. The microfinance logic: what is a productive use of a loan?

From the very beginning of the microfinance movement, the presumption was that the poor lack access to formal credit and, as a result, are deprived of the ‘right’ to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities (Hudon, Citation2009). Through microcredit, they were to pull themselves out of poverty by investing in microenterprises or asset acquisition (Dichter, Citation2007b). At the same time, a growing body of literature demonstrates that self-employment and micro-business creation are in fact not that frequent in microfinance. A list randomization experiment by Karlan and Zinman (Citation2012) finds that the vast majority of ‘business’ microloans are spent on household items, and health and education emergencies. This is in line with the results of Guérin et al. (Citation2012) whose case study from Southern India proves that only 4.5% of all loan recipients in a local MFI were pursuing micro-business ventures, with the remaining loans financing health expenditures (22%), children’s education (16%), housing (14%), ceremonies (15%) and repaying other debt (12%). Recent findings from Mongolia, by Attanasio et al. (Citation2015), prove that over half of microcredit ‘business loans’ were used for the purchase of household assets as well as paying off other loans. An investigation of Indonesian microfinance by Gertler, Levine, and Moretti (Citation2009) reveals that the primary value that families derive from their loans is not investment, but insuring household consumption against health shocks.

Accordingly, it is safe to assume that the proportion of micro-loans that are not used for investment is much larger than microfinance theorists assumed. Furthermore, while some forms of consumption spending might indeed increase the defaulting risk of the clients (Schicks, Citation2014), it is not necessarily true for all types of ‘consumption’, nor even for the majority of cases. Dichter argues that the micro-borrowers who actually want to invest in new ventures prefer to start them up with informal credit or savings (Citation2007b). He writes: ‘because a loan from a friend or a relative is based partly on a social connection, the entrepreneur gains a hedge since he knows the arrangement is “softer,” more “patient,” more risk tolerant, and less return driven, than a formal loan. In short, such loans are prevalent, not because of a lack of access to formal financing (even when such lack of access may be the case), but because they are preferable to the borrower from a financial risk standpoint’ (Citation2007b, p. 6). Accordingly, the MFI sector’s emphasis on ‘productive loan use’ does not adequately meet the financial needs of the poor (Nourse, Citation2001). Against this background, consumption spending, loan juggling, loan arrogation and illegitimate investment are not only expected, but in fact necessitated by the way the microfinance products are designed and framed. A number of cases of rule-breaking can be seen as correcting for what Nourse calls the ‘missing part’ of microfinance, namely loans for consumption and provision of insurance (Citation2001).

3.2. Values, norms and markets: an anthropological perspective

Anthropologists of exchange have long argued that traditional societies often organize trade and commerce on bases different from Western economies (Malinowski, Citation1978; Mauss, Citation1990). Indeed, in settings similar to the Burundian colines, social networks and culturally legitimized dealings often prevail over market-efficient behavior (Allovio, Citation1997; Goodman, Citation2017). These communities are tied together by a fundamental rule of agrarian societies: the ethic of subsistence. Culturally sanctioned and historically reinforced through patronage and clientelism, the ethics of subsistence manifest themselves through a dense network of interdependencies, and warrants the survival of the group under the condition of extreme scarcity (Sayer, Citation2007). Attitudes to debt, relational value of interest rates, and the blurred boundary between savings and credit are some examples where the understanding of traditional societies significantly differs from the rules of Western finance (Shipton, Citation1995).

Against this background, rule-breaking may be interpreted as a rational, logical choice to embed formal credit transactions with MFIs in a dense network of community-level dependencies, social contracts and micro-dealings to de facto secure it and minimize the risk of defaulting. In the next section, we discuss the role of rule-breaking with reference to entrepreneurial orientation (risk propensity), method (innovation as path-breaking) and outcome (value creation) as presented in interdisciplinary literature.

4. Entrepreneurs as rule-breakers

Research has shown that entrepreneurial behavior often entails breaking the existing rules and conventions. Transgression, non-conformism and subversion are embedded in any pioneering work and characterize visionaries, discoverers and entrepreneurs (Fisscher, Frenkel, Lurie, & Nijhof, Citation2005).

4.1. Entrepreneurial orientation and risk propensity

Willingness to take risks has been proven to be symptomatic of independent and divergent thinking, which, in turn, forecasts creativity and innovation specific to entrepreneurial behavior (Johannisson & Wigrem, Citation2009). A true entrepreneur is supposed to be the ‘path-breaker’ (Bornstein, Citation1998b, p. 5), the ‘leader of innovation’ (Grenier, Citation2006, p. 121) and the ‘provocateur’ (Johannisson & Wigrem, Citation2009, p. 47).

Empirical studies bring convincing evidence linking risk propensity and entrepreneurial orientation. The research of Zhang and Arvey (Citation2009) reveals that people with high-risk propensity in adolescence are also more likely to start new entrepreneurial ventures later in life. Another study by Aidis and van Praag (Citation2007) shows that past criminal experience is often correlated with successful entrepreneurial future. Similar evidence was found in a study by Fairlie (Citation2002), who uses past drug-dealing experience as a proxy for individual characteristics (such as risk-taking) and find it positively correlated with entrepreneurial skills. All of these studies indicate that risk-taking behavior links itself to entrepreneurial orientation.

4.2. Innovation as path-breaking

Together with risk propensity, innovativeness is the key concept linking rule-breaking with entrepreneurial behavior (Mulgan, Citation2006). Brenkert (Citation2009) argues that challenging regulatory frameworks provided by institutions and governments (‘modest rule-breaking’) constitutes the first step in the advancement of innovation (Brenkert, Citation2009, p. 448). Snyder, Priem, and Levitas (Citation2009) find that innovating against the rules is relatively widespread among CEOs of large firms, while Morrison (Citation2006) describes how the cases of employees’ rule-breaking result in improving organizational efficiency, and are signs of bottom-up innovativeness (Morrison, Citation2006, p. 23). Focusing on microfinance, another study by Canales (Citation2011) reveals that the loan officers frequently bend institutional regulations in order to better address their clients’ needs. This line of research proposes that it is also ordinary actors, who, through unruly practices, foster institutional innovation, leading to increased value proposition within organizations.

4.3. Entrepreneurial outputs – value creation

Most frequently, entrepreneurs are treated as synonymous with managers or simply as business owners. In order to delineate the unique domain of entrepreneurship from other business literature, the former has been defined as bringing about a new quality, or, in other words, value creation (Bruyat & Julien, Citation2001). What deserves special attention in the context of microfinance, however, is that what constitutes value varies across social, cultural and economic contexts (Lepak, Smith, & Taylor, Citation2016). For example, a study on illegal cross-border trading in Nigeria by Fadahunsi and Rosa reveals that ‘illegal practices are so widespread that they are a norm, an almost parallel economy with its own traditions and values’ (Citation2002, p. 397). The authors argue that these practices have a positive entrepreneurial potential, creating jobs and informal businesses and allowing the traders to operate more securely in their corrupt environment. Similarly, a study by Amoako and Lyons (Citation2013) shows how entrepreneurs in Ghana avoid recourse to the courts and employ culturally sanctioned rules of dealing to settle internal disputes, creating a parallel informal legal system with a unique set of values. Accordingly, if we assume that value creation constitutes the core element of entrepreneurship, we need to acknowledge that both values and norms vary significantly across contexts.

4.4. Value creation and microfinance

Some existing studies already document how microfinance management and staff exhibit differing views on their institution’s role and purpose (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010). The standpoint of the clients, however, is missing from the mainstream discussion. Their role remains limited to receiving services and products. Recently, participatory product design has become a hot topic in microfinance (Labie, Laureti, & Szafarz, Citation2015), propelled by the realization that, while some of the regulations were put in place for pragmatic reasons (customer protection against over-indebtedness, ensuring the financial viability of the MFI), others have been funded on purely normative grounds. For example, a number of Christian MFIs do not lend to entrepreneurs intending to invest in alcohol sale or the purchase of gambling equipment. At the same time, a growing body of research rejects the central assumption of this scheme, namely that microfinance clients are lacking in discipline and financial literacy, and hence need to be heavily controlled in their spending choices. A number of researchers pointed out that the poor are extremely capable in managing their finances (Collins et al., Citation2009; Dickerson, Citation1999; Guérin, Citation2012). Accordingly, in a number of cases, it is neither ignorance nor inability that drives the rule-breaking practices, but a conscious, entrepreneurial choice to adjust the microfinance products to the clients’ actual needs.

The microfinance sector prides itself on promoting entrepreneurship among the poor. In the empirical part of this paper, we argue that it is through the innovative, daring rule-breaking behavior that the clients’ entrepreneurial identity articulates itself as they strive to create and/or multiply value.

5. Research site – rural Burundi

The microfinance sector in Burundi in 2012 (when this research was done) was relatively young and the exposure to microfinance services was low in comparison with other African countries. Despite the fact that the microfinance industry has expanded considerably in the recent years, it still does not meet the country’s demand for microcredit, in particular in the rural areas of the country

Located in the Great Lakes region, Burundi is one of the poorest countries in Africa; the vast majority of the country’s population comprising small-scale subsistence farmers. With population density reaching peaks of 500 persons per square kilometer, the average farmable land of a household is around 0.5 ha, resulting in a persistent risk of food insecurity and fragile nutritional conditions.

5.1. Sample characteristics

The interviews conducted for the purpose of this research were collected in seven rural and semi-rural provinces of Burundi (Appendix B), selected if microfinance providers of any kind were present. Respondent selection was based on purposeful convenience sampling: we conducted the interviews on market days, mostly in the provincial capitals, singling out interviewees with previous or current microfinance experience.

When investigating an under-researched phenomenon in the qualitative tradition, it is commonplace to select a relatively homogenous sample (Ritchie, Lewis, & Elam, Citation2003). For the purposes of this exploratory research, we chose respondents of a uniform profile and our focus was on identifying the general patterns, mechanisms and tendencies. The vast majority of our respondents were smallholder farmers, with the exception of several village vendors (Appendix B). Bananas, rice, sorghum, coffee and sugar cane were the main crops, and most of these farmers also kept a vegetable garden. Thirty-four out of 66 interviewees were women; mostly married. Characteristically for Burundi, a vast majority lived in multi-generational households; sharing household expenses with in-laws and siblings. Not all of the respondents were microfinance clients at the time of the interview (some were past or prospective clients), but they had presented sufficient knowledge and experience with the microfinance sector.

5.2. Specificity and limitations of the study

The rural communities of Burundi are not an easily accessible research site. In order to be introduced to, and accepted by, the interviewees, the research was conducted with the assistance of the university students from the University of Burundi who agreed to be the ‘gate keepers’ to their home communities. Also, because of the sensitivity of the topic understudy no personal information was elicited from the respondents (personal details of the respondents’ profiles are missing from the study).Footnote1

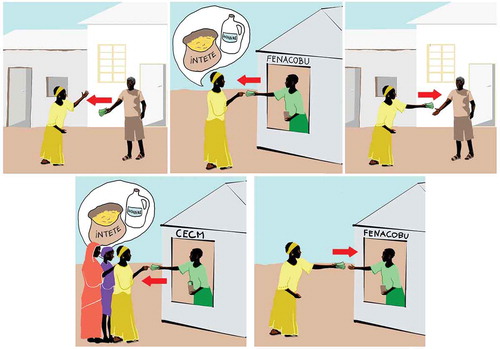

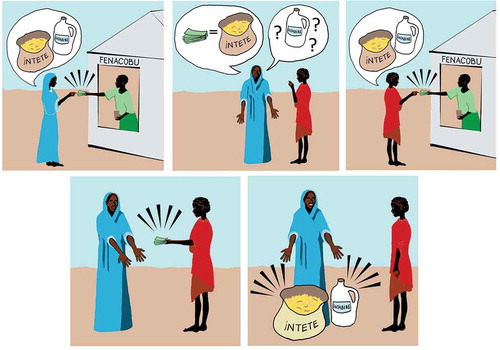

6. Methodology – tool and protocol

The field research focused on identifying the existing rule-breaking practices, and on exploring their value-creating potential. The interviewees were exposed to storyboards – a series of specially designed pictures presenting a narrative scheme of a given unruly practice (–). Subsequently, they were asked to describe the course of events and pass judgment on the storyboards’ protagonists. The storyboard panels were presented as ‘riddles’ the content of which was to be deciphered by the interviewee. If necessary, modest prompts (‘why is that?’, ‘and what happened next?’, ‘what is your opinion on that?’) were applied.

With the use of storyboards, sensitive information (i.e. concerning rule-breaking) can be elicited from the respondents in a non-invasive, non-threating way (Chung & Gerber, Citation2010). Visually displaying a neutral overview of information stimulates divergent thinking, allowing for the examination of sensitive topics through mechanisms of identification, substitution and projection (Czarniawska-Joerges, Citation1997; Denning, Citation2004; Karlan & Zinman, Citation2012). The use of storyboarding technique elicits holistic answers as opposed to categorical normative judgments. Creating a narrative from disconnected images entails explaining the relationships between elements (facts, actors) and the overall scheme (motivations, outcomes, valuation) (Moraveji, Li, Ding, O’Kelley, & Woolf, Citation2007).

At the same time, it is important to observe that the applied methodology does not allow us to categorize the narratives into ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ interpretations. In the course of narration, the respondent’s normative judgement shifts back and forth: the same speaker might find the storyboard’s protagonist ‘crafty’ and ‘resourceful’ and later reflect on his/her behavior as irresponsible or unfair.

The choice of research methodology turned out to be appropriate. Refusal to participate was rare (four instances).

7. Findings

The results comprise 66 short narratives, elicited as responses to the storyboard material. There were four storyboards, each corresponding to one of the four unruly practices: consumption spending, illegitimate investment, loan juggling and loan arrogation.

7.1. The rule-breaking processes

An important primary result is undoubtedly the reconstruction of the rule-breaking process. As illustrates, unruly behaviors may occur in different scenarios depending on the loan decision.

In Western economies, the entrepreneurial process’s activities unfold in stages: entrepreneurial alertness, opportunity and exploitation, and decisions concerning growth (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000). Interestingly, the rule-breaking behavior arises along a similar pattern: once the loan is refused, the entrepreneur resorts to rule-breaking in order to compensate for the lack of, or insufficient amount of, resources (Baker & Nelson, Citation2005). Through the means of social capital (networking, bonds, alliances, partnerships) and informal dealings (local borrowing and lending arrangements), the entrepreneur strives first to secure venture capital, then maximize their prospective output, and finally insure the investment by embedding it in community networks and social dependencies ().

7.2. Consumption spending

Perhaps the most widespread among the unruly practices is spending loan money on consumption (Karlan & Zinman, Citation2012). Widely applied, the term covers an array of activities ranging from expenditure on subsistence needs, such as food and health care, to expensing special events and emergencies (Collins et al., Citation2009). All of these are non-income generating activities and as such are prohibited by most MFIs (Dichter, Citation2007a; Shakya & Rankin, Citation2008).

Unsurprisingly, the consumption spending storyboard was identified and aptly interpreted as such in most of the researched communities. A story of a woman who, despite having obtained loan capital for agriculture, chooses to throw a wedding for her daughter, turned out to be easily understood and enthusiastically narrated by the respondents (). Comments on the protagonist’s behavior were rarely reproachful. The woman’s actions were understood as standard and commonplace. Apart from indicating how widespread the practice of consumption spending might be, the range of answers also suggests the existence of an alternative normative paradigm against which the woman’s behavior may be judged. The lack of concern for the truthfulness of the loan application statement allows for viewing the woman’s actions as acceptable, as she serves her loyalties not to the MFI, but to family and community. ‘She is a mother, what else could she do?’ – one of the respondents asked rhetorically. Caring for children’s well-being and getting them ‘established’ in the community were perceived as values in themselves.

The results also reinforced the argument that separating consumptive and productive loan uses is often impossible when trying to account for household expenditures (Collins et al., Citation2009). Investments made in health care and education, though not income-generating, have the potential of improving the overall financial situation of the household in the long run. Against this background, the protagonist’s choices seem both logical and legitimate.

Importantly, investing in social events has a considerable value-creating potential. Participation in cultural and religious life and observing ceremonies provides a key mechanism for the disbursement of resources. Sharing food and exhibiting generosity and hospitality are important gestures that integrate the community, guaranteeing inclusion, shared responsibility and participation in exchange systems – the exponents of social capital.

7.3. Illegitimate investment

Illegitimate investment entails using loan capital for ventures that are profit-generating but different from purposes stated in the client’s loan application. It includes investments of ambiguous status (such as entertainment equipment, alcohol production) as well as investments with a long-term profit cycle and money-lending (Shakya & Rankin, Citation2008). In the storyboard, the practice is represented as a story of a woman, who, despite having obtained a loan for agriculture, choses to invest in a banana-beer business ().

When confronted with the ‘illegitimate investment’ storyboard, a number of respondents did not identify the rule-breaking behavior as transgressive. The process of applying for a loan was perceived as a procedure with a limited number of ‘correct’ answers. Following the example of previous, successful applicants, the prospective client simply writes one of the loan purposes that ‘worked’ the trick of securing a loan for someone in the past. The process of obtaining a loan thus escapes normative judgment: as long as the applicant has a ‘project’ in mind and is able to secure repayment the actual use of the money is considered a personal matter.

The woman in the pictures is referred to as smart and resourceful. She is seen as the one who knows best what kind of venture would secure income source, regardless of the MFI’s plans or mission objectives. She is praised not only for her wit but also for supplying the community with the service/product that was in high demand (beer). Though seen as a vice by many microfinance agents, alcohol vending is part of the rural reality of Burundi. Instead of being perceived as a transgression, the rule-breaking behavior of the protagonist in fact remains in accordance with the local normative paradigm.

7.4. Loan juggling

When the procedures of securing a loan have been learnt, it is increasing the loan volume that becomes the challenge. Loan juggling, understood as borrowing from multiple sources, is a common rule-breaking practice, where the clients sustain long-term debt financing by drawing on multiple lenders and repaying credit with debt (). Loan juggling often entails mixing formal with informal lending services, revealing how very dependent on the circulation of borrowed money the MFIs really are (Guérin et al., Citation2012; Shakya & Rankin, Citation2008).

The storyboard presented a woman who first borrows from a neighbor, then, in order to repay her debt turns to a saving cooperative, and finally also to a formal microcredit provider. While often identified as a ‘prohibited’ activity, the practice of loan juggling was also often referred to as ‘the thing to do’. The respondents were quick to observe that sustaining multiple sources of debt translates into multiple group participation. The protagonist’s behavior was considered wise precisely because of the high rates that were at stake. Losing membership in a micro-lending group or risking one’s good relations with a neighbor are to be avoided at all cost. Interpreted by the respondents, multiple borrowing cements relationships, builds new alliances and serves as insurance against defaulting.

7.5. Loan arrogation

Practiced through loan migration (changing place of residence to be eligible for a specific loan program) or imposition (using another community member as a ‘substitute lender’ in order to increase own loan volume), loan arrogation is a known technique for securing enough means for the planned investment. In the storyboard, the practice was represented as a tale of a woman, who, having obtained micro-loan insufficient for the planned purchase of fertilizer and grain, asks another community member to apply for a loan in her name. The joint capital is enough to expand her agricultural production, and the woman makes a profit ().

A number of our respondents declared that they, too, had been involved in a similar contract, helping family members, neighbors and friends. The main value ascribed to the practice was the quality of ‘togetherness’, seen as a source of strength and resilience. Joined by the common investment, the two women are sharing the responsibility for the project and the prospective profit will benefit them both. In addition, relying on friends’ and neighbors’ help and advice is often considered a gesture of respect, as it honors the importance of the relationship in the borrower’s life.

Apart from being recognized as commonplace, the four instances of rule-breaking behavior prove to be prone to a plurality of interpretations. Though prohibited from the institutional point of view, the clients’ rule-breaking practices are loaded with entrepreneurial potential, and, according to our respondents, are also value-creating. Creativity, innovativeness, increased potency and control over one’s finances, community integration, preserving social bonds, building alliances, social inclusion and participation are only some of the examples of how value is created in multiplied in communities, outside the realm of institutions ().

Table 2. Unruly practices: regulation approach and social entrepreneurial approach.

8. Analysis and interpretation – value creation?

8.1. Needs and values

In the picture, I can see a woman who has a family, a rather poor family, just like me and my folks, with little money, not even for food, and then she got some money from the credit union, so she left, went far, far to the market, to buy gifts that she will give to her friend who is going to be married. (Is it good to go apply for credit to buy gifts for a friend?) Yes, it is good! It allows you to participate in this festival with honor (…). If I manage to buy a really big gift for a friend’s wedding I’m going to show him that I really am a generous man, a true and honest friend. Then he will also help me if I need it! Look here, it seems that the bride and groom are wealthy, they bought so much food. I’m sure that after receiving my gift, they would not let me starve, this wealthy family, I mean, if I am in distress./Kirundo – Ruhehe/

The starting point for investigating value is the establishment of pending needs. With chronic poverty prevalent in Burundi, the populations under study associate value primarily with basic needs fulfilment, food in particular. The interviewees univocally identified themselves as poor or very poor, drawing parallels between their own lives and the storyboard narratives. Surely, spending money on meals might not be the best project. But, look at it this way: if you don’t eat, how can you work on your investment? If you are hungry, your work can’t be done. Being able to provide for one’s family is seen as a value worth bending the rules for. This woman in the picture, I am sure she had a business plan in mind. But then she came back home, looked at her hungry children, looked in their eyes, and just changed her mind. She will start the project from feeding them all, and then she will see – narrated one of the interviewees, absolving the protagonist’s transgressive behavior. Here in Burundi, we have a saying: you can’t feed your children with virtue alone! – reaffirmed another one, when asked about the truthfulness of the protagonist’s loan application.

8.2. Bonds that bind

What is beneficial for the family is understood as beneficial for the household, its welfare and livelihood. A child that is well fed will not get sick and keep the mother from her work. Work done in due time will earn the family a decent living, keeping it from over-indebtedness and granting a good social standing in the community. Good social standing translates in turn into highly regarded good relationships with neighbors and village elders, granting prosperous coexistence and numerous options for informal credit. Just as consumptive and productive spending cannot be separated at the household level, the boundary between gifts, credit and ceremony are blurred at the community level. This is in line with the anthropological writings we referred to earlier, where ‘community’ becomes a relational system that perpetuates specific ideological and cultural contents that both constrain and enable the functional capacities of its members (Bernard et al., Citation2010). Distinguishing between individualistic and communitarian/collective behavior thus becomes impossible when analyzing the dynamics of traditional societies (Hart, Citation1988).

Importantly, as illustrated by the quote above, friendship and kin relationships are guided by sets of strictly observed rules of obligation and reciprocity. And here (in the picture) I see that she (the protagonist) finally has the money, and she wants to give it to the woman who showed her how to do this trick (loan juggling); that came up with the whole idea; to show her gratitude. She will pay her some! – speculated one of the interviewees. Just as social value is intrinsically intertwined with economic value, social debt translates into financial obligation. Sharing and mutual help are deeply embedded in the understanding of friendship and as such also valued as social collateral for future investments; an arrangement similar to the ‘bonds of necessity’ described by Marglin (Citation2008). Interestingly, as opposed to group-based microfinance where prospective members are selected on the basis of their projected financial viability (‘bonds of affinity’); rule-breaking behavior prioritizes bonds of friendship (‘necessity’). When about to break the rules (loan juggling or loan arrogation practices), it is kin or a long-term friend that one chooses to rely on for help.

8.3. Gifts, ceremonies and reciprocity

In order to benefit from kindship bonds, it is necessary to maintain them properly – a task that again entails both financial and social capital. In the quote at the beginning of the section, the respondent firmly stated that generosity and loyalty are in fact two sides of the same coin. This belief was shared by many: To tell them that I need money for a celebration? Who will ever put that on a form? You will never get money for that… But then marriage celebration, well, can lead to good things too. The wealthy family of the groom, they won’t let him starve, will they? And you’re with him, and so are your children. A dense network of mutual interdependencies guarantees a more secure and relatively shock-resilient living. Interestingly, sharing responsibility for rule-violation seems to trigger very different mechanisms from peer-administered pressure in orderly operating group-lending MFI projects. A respondent, recounting a loan-juggling experience, narrated: There is no jungle without one dangerous animal. Beware! Rely on your kin But, this only teaches the importance of working together, in association with friends. We negotiate first how it is going to be… And I won’t have problems, running left and right, we are in this together. The jointly committed offense seems to cement the bonds, and become a unifying force marking an attitude of non-adherence to the outside force (the MFI). The rule-breaking becomes an opportunity to create new social networks and deepen the existing ones.

8.4. Entrepreneurship, resourcefulness and risk management

It is perhaps through its effect on empowerment that rule-breaking behavior stimulates leadership development. The feeling of empowerment, or dauntlessness, is apparent in some of the interviews. Outwitting the institution, learning to ‘work the system’ is seen as regaining control of the community’s financial plight. One of the respondents explains this rationale when describing the storyboard illustrating illegitimate investment: well look, so what she said something else at first, she might have changed her mind. The important thing is that she got the money, and then she thought: will I feed my children with fertilizer? But, if she starts, say, sorghum-beer business, she will have no problem with repaying the loan fast. And she will always have left-over sorghum beans if someone is hungry… Now, that I call a business plan! The potential ban on investing the loan capital in alcohol production seems irrelevant to the speaker. What matters is the entrepreneurial skill of the protagonist, the value she is about to generate, and the fact that her repayment capacity is not compromised but potentially boosted by the new business scheme.

8.5. Value created, value reclaimed

Interestingly, the disregard for how rule-breaking may affect the MFI seems to be commonplace. Not knowing how the lending methodologies and products are being developed, the clients take on the attitude of either ignorance or indifference. The rules on loan size, allocation, and execution are rarely seen as regulating structures put in place for reasons of client protection and continuous functioning of the institution. Instead, they are perceived as one of the many elements of the complex reality of the poor, a reality to be fought in the battle for survival.

These observations are especially important because MFIs are mission-driven, social organizations. The ongoing debate over the balance between social mission and financial objectives brings evidence on substantial mission drift in the sector, spurring a discussion of what kind of value MFIs actually pursue (Mersland & Strøm, Citation2010). The observed discrepancy between how the different actors view value indicates that it is indeed the clients and their communities where the industry should seek its answers. Including the clients’ perspective would allow the MFIs to adapt their services better to the needs of the communities they serve and leverage their positive social impact (D’Espallier, Guérin, & Mersland, Citation2011).

The rule-breaking behavior, while not necessarily to be encouraged, is a topic worth further investigation. Though in the first instance, rule-breaking may be attributed to private gain motivations, it also generates value for the community by strengthening the existing social ties and generating new ones. In order to amplify their impact on communities, MFIs may want to recognize this neglected entrepreneurial potential and facilitate supportive environments for value creation.

What is considered legal, or legitimate, is defined by a set of norms that are established by the group that is either in majority or in the position of power (Scott, Citation1995). As our results illustrate, numerous activities are considered transgressive simply because of the difference in normative paradigms (Webb, Tihanyi, Ireland, & Sirmon, Citation2009, p. 492). As the previous sections demonstrated, the four informal arrangements comprise a range of forbidden, and yet, within the group, legitimate activities, through which actors recognize and pursue entrepreneurial opportunities (Castells & Portes, Citation1989). The ‘unruly entrepreneurs’ indeed engage in prohibited activities; however, by doing so they ‘rely on the legitimacy that comes by operating within informal institutional boundaries to exploit opportunities and operate their ventures outside formal institutional boundaries’ (Webb et al., Citation2009, pp. 492–493). Our results show that, though remaining illicit, these activities gain within-group legitimation through the mechanisms of collective identity and dis-identification with the agents of formal economy. As we demonstrated in the theoretical section, the unruly practices are incredibly common, and consumptive use of loans might far exceed the productive one. They are also not necessarily harmful to the operations of the MFIs, under the condition that repayment rates are not compromised beyond the threshold level.

As Webb et al. observe, ‘when informal institutions guide entrepreneurs’ perceptions of legitimacy more strongly than do formal institutions’ prescriptions, the entrepreneurs become alert to opportunities in the informal economy (Citation2009, p. 500).’ The community’s collective, established dynamically over a number of years, is bound to have a stronger legitimizing power than a set of external rules arbitrarily decided upon by a microfinance provider. The positive entrepreneurial potential of the rule-breaking practices only reveals itself when judged against the relative interests of this community, and it is through the collective identity mechanisms that entrepreneurial value creation can occur, spread and thrive.

9. Conclusion

Recognizing value in the practices of transgression is only possible when one acknowledges the specific normative paradigms of the populations in question. The results of this research prove that, in the context of rural Burundi, value creation is embedded in the communal, or group, interest. Tied by common interests and networks of mutual dependencies, microfinance clients evade individualization via means of indirect resistance and non-conformity to the MFI’s rules and protocols (Shakya & Rankin, Citation2008). While it can be assumed that these rules and protocols were put in place in order to protect the clients and secure continuous provisioning of services, the results also pose some fundamental policy recommendations.

Understandings of value and value-creation seem inconsistent when comparing the perspectives of the MFIs and the populations they are meaning to serve. At the same time, considering how widespread and frequent the rule-breaking instances might be (as argued in section 3a), it seems likely that it is not necessarily detrimental to the financial viability of the MFIs. Elaborate regulation and strict rules of conduct, though supposedly put in place to secure the success of the microfinance scheme, are easily evaded by the clients and not always necessary. Seen as such, investigating rule-breaking might help expose flaws in outdated organizational systems, pioneer new endeavors in the ‘grey areas’ of institutions and facilitate the abolition of the standing legacies of the past. Transgressive practices and nonconformity of development beneficiaries can contribute to a reform of the MFI towards a more participatory mode of organizational governance.

For the last 40 years of its existence, the microfinance sector has undergone remarkable expansion and evolution. New, diverse services including savings and insurance as well as advances in management strategy have undoubtedly improved the services provided to poor populations. Nonetheless, together with the growth of the industry, microfinance seems to have moved a step away from the clients. Co-designed by the women of Grameen Bank, the microfinance model assumed client participation from its very origin. It is this participation in product design and implementation that seems to be missing in the MFIs nowadays, forcing clients to bend the rules in order to extract all the value needed. A more inclusive approach could increase the value proposition of many microfinance interventions; thus turning the rule-breakers into creators of value.

ODS_Cieslik_Supplemental_File_final.pdf

Download PDF (255.6 KB)Acknowledgments

This paper was realized with the financial support of the Marie and Alain Philippson Foundation. The fieldwork for this paper was made possible thanks to the cooperation with the students from the University of Burundi in Bujumbura: Doris Muhimpundu Irankunda, Dieudonné Ayubu, Ernest Niimpagaritse and Philbert Basomingera, to whom the authors would like to extend their warmest gratitude. Further thanks go to artist Anna Eichler who designed the storyboards for the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

The supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katarzyna Cieslik

Katarzyna Cieslik is a research fellow at Wageningen University. She is interested in livelihoods and entrepreneurship in the context of sustainable development.

Marek Hudon

Marek Hudon is a professor at Solvay Brussels School of Economics & Management (ULB). His research interests are microfinance and sustainable development.

Philip Verwimp

Philip Verwimp is a profesor of Development Economics at the Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management. His research interest are in health, education, poverty an violent conflict.

Notes

1. For the same reason, the study presents the perspective of the microfinance clients and prospective clients alone, refraining from investigating the point of view of the institutions. We believe that association with the officers or managers of the local MFIs could have endangered the trust bond and possibly distorted the interview outcomes.

References

- Aidis, R., & van Praag, M. (2007). Illegal entrepreneurship experience: Does it make a difference for business performance and motivation? Journal of Business Venturing, 22, 283–310.

- Allovio, S. (1997). Burundi identità, etniee potere nella storia di un antico regno. Torino: Il Segnalibro.

- Amoako, I. O., & Lyons, F. (2013). ‘We don’t deal with courts’: Cooperation and alternative institutions shaping exporting relationships of small and medium-sized enterprises in Ghana. International Small Business Journal, 32(2), 117–139.

- Anderson, A. R., & Smith, R. (2007). The moral space in entrepreneurship: An exploration of ethical imperatives and the moral legitimacy of being enterprising. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(6), 479–497.

- Attanasio, O., Augsburg, B., De Haas, R., Fitzsimons, E., & Harmgart, H. (2015). The impacts of microfinance: Evidence from joint-liability lending in Mongolia. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 90–122.

- Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366.

- Banerjee, A., & Duflo, E. (2006). The economic lives of the poor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 141–168.

- Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440.

- Bernard, T., De Janvry, A., & Sadoulet, E. (2010). When does community conservatism constrain village organizations? Economic Development and Cultural Change, 58(4), 609–641.

- Berner, E., Gomez, G., & Knorringa, P. (2012). Helping a large number of people become a little less poor: The logic of survival entrepreneurs. European Journal of Development Research, 24(3), 382–396.

- Bornstein, D. (1998b). Changing the world on a shoestring. Atlantic Monthly, 281(1), 34–39.

- Brenkert, D. P. (2009). Innovation, rule breaking and the ethics of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 24, 448‐464.

- Bruton, G. D., Khavul, S., & Chavez, H. (2011). Microfinance in emerging economies: Building a new line of inquiry from the ground up. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 718–739.

- Bruyat, C., & Julien, P.-A. (2001). Defining the field of research in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(2), 165–180.

- Bylander, M. (2015). Credit as coping: Rethinking microcredit in the Cambodian context. Oxford Development Studies, 43(4), 533–553.

- Canales, R. (2011). Rule bending, sociological citizenship, and organizational contestation in microfinance. Regulation & Governance, 5(1), 90–117.

- Castells, M., & Portes, A. (1989). World underneath. The origins, dynamics, and effects of the informal economy. In A. Portes, M. Castells, & L. Benton (Eds.), The informal economy; studies in advanced and less developed countries (pp. 11–37). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Chung, H., & Gerber, E. (2010). Emotional storyboarding: A participatory design method for emotional designing for children. Proceedings of 7th nternational Conference on Design & Emotion, 5–7 October. Northwestern University. Available at http://egerber.mech.northwestern.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2012/11/Gerber_EmotionalStoryboarding1.pdf

- Collins, D. (2008). Debt and household finance: Evidence from the financial diaries. Development Southern Africa, 25(4), 469–479.

- Collins, D., Morduch, J., Rutherford, S., & Ruthven, O. (2009). Portfolios of the poor: How the world’s poor live on $2 a day. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Czarniawska-Joerges, B. (1997). Narrating the organization: Dramas of institutional identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- D’Espallier, B., Guérin, I., & Mersland, R. (2011). Women and repayment in microfinance: A global analysis. World Development, 39(5), 758–772.

- Denning, S. (2004). Telling Tales. Harvard Business Review, 5(1), 122–129.

- Dichter, T. (2007a). Introduction. In T. Dichter & M. Harper (Eds.), What’s wrong with microfinance? (pp. 1–6). Warwickshire: Practical Action Publishing.

- Dichter, T. (2007b). A second look at microfinance - The sequence of growth and credit in economic history. Development Policy Briefing Paper, CATO Institute (202), 1–13. Retrieved from http://www.cato.org/pub_display.php?pub_id=7517

- Dickerson, M. (1999). Can shame, guilt, or stigma be taught? Why credit-focused financial education may not work. Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review, 32(4), 945–964.

- Fadahunsi, A., & Rosa, P. (2002). Entrepreneurship and illegality: Insights from the Nigerian cross-border trade. Journal of Business Venturing, 17, 397–429.

- Fairlie, R. W. (2002). Drug dealing and legitimate self-employment. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(3), 538–567.

- Fernando, J. (2006). Micro-credit and empowerment of women: Blurring the boundary between development and capitalism. In J. Fernando (Ed.), Microfinance: Perils and prospects, routledge studies in development economics (pp. 162–205). London: Routlege.

- Fisscher, O., Frenkel, D., Lurie, Y., & Nijhof, A. (2005). Stretching the frontiers: Exploring the relationships between entrepreneurship and ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 60, 207–209.

- Gertler, P., Levine, D. I., & Moretti, E. (2009). Do microfinance programs help families insure consumption against illness? Health Economics, 18(3), 257–273.

- Goodman, R. (2017). Borrowing money, exchanging relationships: Making microfinance fit into local lives in Kumaon, India. World Development, 93, 362–373.

- Grenier, P. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: Agency in a globalizing world. In A. Nicholls (Ed.), Social entrepreneurship: New paradigms of sustainable social change (pp. 119–143). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Guérin, I. (2012). Households’ over-indebtedness and the fallacy of financial education: Insights from economic anthropology. Microfinance in Crisis Working Papers Serie, 1. Paris: Paris I Sorbonne University/IRD.

- Guérin, I., Kumar, S., & Agier, I. (2013). Women’s empowerment: Power to act or power over other women? Lessons from Indian microfinance. Oxford Development Studies, 41(Sup1), S76–S94.

- Guérin, I., Roesch, M., Venkatasubramanian, G., & D’Espallier, B. (2012). Credit from whom and for what? The diversity of borrowing sources and uses in rural southern India. Journal of International Development, 24(1), 122–137.

- Guyer, J. (1981). Household and community in African studies. African Studies Review, 24(2/3), 87–137.

- Hart, K. (1988). Kinship, contract and trust. In D. Gambetta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations (pp. 176–193). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hudon, M. (2009). Should access to credit be a right? Journal of Business Ethics, 84(1), 17–28.

- Huiskamp, G., & Hartmann-Mahmud, L. (2007). As development seeks to empower: Women from Mexico and Niger challenge theoretical categories. Journal of Poverty, 10(4), 1–26.

- Johannisson, B., & Wigrem, C. (2009). The societal entrepreneur as provocateur. In M. Gawell, B. Johannisson, & M. Lundqvist (Eds.), Entrepreneurship in the name of society. Reader’s digest of a Swedish research anthology (pp. 47–51). Stockholm: Knowledge Foundation.

- Karim, L. (2008). Demystifying micro-credit: The Grameen bank, NGOs, and neoliberalism in Bangladesh. Cultural Dynamics, 20(1), 5–29.

- Karlan, D. S., & Zinman, J. (2012). List randomization for sensitive behavior: An application for measuring use of loan proceeds. Journal of Development Economics, 98(1), 71–75.

- Labie, M., Laureti, C., & Szafarz, A. (2015). Discipline and flexibility: A behavioral perspective on product design in microfinance. CEB Working Paper 15/020.

- Lepak, D. P., Smith, K. G., & Taylor, M. S. (2016). Value creation and value capture : A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 180–194.

- Malinowski, B. (1978). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An account of native enterprise and adventure in the archipelagos of melanesian new Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Marglin, S. A. (2008). The dismal science: How thinking like an economist undermines community. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mauss, M. (1990). The gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. New York and London: Norton.

- Mersland, R., & Strøm, T. (2010). Microfinance mission drift? World Development, 38(1), 28–36.

- Moraveji, N., Li, J., Ding, J., O’Kelley, P., & Woolf, S. (2007). Comic-boarding: Using comics as proxies for participatory design with children. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, San Jose, US, 1371–1374.

- Morrison, E. W. (2006). Doing the job well: An investigation of pro-social rule breaking. Journal of Management, 32(1), 5–28.

- Mulgan, G. (2006). The process of social innovation. Innovations: Technology Governance Globalization, 1(2), 145–162.

- Nourse, H. T. (2001). The missing parts of microfinance: Services for consumption and insurance. SAIS Review, 21(1), 61–69.

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Elam, G. (2003). Designing and selecting samples. In J. Richie & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 77–108). London: Sage Publications.

- Sayer, A. (2007). Moral economy as critique. New Political Economy, 12(2), 261–270.

- Schicks, J. (2014). Over-indebtedness in microfinance — An empirical analysis of related factors on the borrower level. World Development, 54, 301–324.

- Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Shakya, Y. B., & Rankin, K. N. (2008). The politics of subversion in development practice: Microfinance in Nepal and Vietnam. Journal of Development Studies, 44(8), 1214–1235.

- Shane, S. A., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25, 217–226.

- Shipton, P. (1995). How Gambian save: Culture and economic strategy at an ethnic crossroad. In J. Guyer (Ed.), Money matters. Instability, values and social payments in the modern history of West-African communities (pp. 245–277). London and Portsmouth (NH): Currey Heinemann.

- Snyder, P. J., Priem, R. L., & Levitas, E. (2009). The Diffusion of illegal innovations among management elites. Academy of management conference best paper proceedings, Chicago, US.

- Webb, J. W., Tihanyi, L., Ireland, R. D., & Sirmon, D. G. (2009). You say illegal, i say legitimate: Entrepreneurship in the informal economy. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 492–510.

- Zhang, Z., & Arvey, R. D. (2009). Rule breaking in adolescence and entrepreneurial status: An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Venturing, 24, 436–447.