ABSTRACT

Peacekeeping and development assistance are two of the United Nations’ (UN) defining activities. While there have been extensive studies of UN engagement in each of these areas, respectively, less attention has been given to the relationship between peacekeeping and development. We examine that relationship in this article. We do so by first considering whether concepts and principles that underpin peacekeeping and development cohere. We then combine original quantitative data with qualitative analyses in order to document the degree to which development goals and activities have been incorporated into UN peacekeeping operations since their inception over 70 years ago. While we observe a steady increase in the level of engagement of peacekeeping with development over time, we argue that short-term security goals have been prioritized over longer-term development objectives in a number of recent UN peacekeeping operations, as peacekeepers have been deployed to contexts of ongoing conflict.

By its own account, two of the United Nations’ primary activities are the maintenance of international peace and security, and the promotion of sustainable development (United Nations, Citationn.d.-a). This focus is reflected in the operational expenses of the United Nations (UN) and its agencies; in 2018, peacekeeping operations sat atop the expenditure list, while a range of agencies with development- and humanitarian-focused goals followed shortly thereafter (UN General Assembly, Citation2020, pp. 48–49). It is also reflected in the organizational hierarchy and responsibilities of the UN Secretariat: the Secretary-General is charged with working with the Security Council on matters of peace and security (UN Secretary-General, Citationn.d.-a), while the Deputy Secretary-General’s responsibilities include supporting the UN’s efforts to be a ‘leading centre’ in development policy and assistance (UN Secretary-General, Citationn.d.-b).

Despite the prominence of both peace and development on the agendas of the UN and its agencies, studies of the relationship between UN peacekeeping, in particular, and the UN’s efforts to achieve development goals are quite limited.Footnote1 This may be due, in part, to the fact that peacekeeping is often studied within the disciplinary confines of political science and international relations, while the UN’s diverse development activities and programmes are considered within a wider range of academic disciplines including economics, history, anthropology, development studies, and beyond. In this article, we set aside disciplinary divides in order to examine the nexus between UN peacekeeping and efforts to promote development in conflict-affected territories. We do so by first considering whether the concepts and principles that underpin peace(keeping) and development cohere. We then use manually-coded data on peacekeeping mission mandates and auto-coded data drawn from (2,300+) mission progress reports in order to document the degree to which development goals, activities, and actors have been incorporated into UN peacekeeping operations (PKOs) since their inception.

We make two broad claims. First, at an ideational level, the concepts and principles that underpin peacekeeping are broadly consistent with, and complementary to, those of development. Indeed, as understandings of ‘peace’ and ‘development’ have evolved and expanded in recent decades, the two terms have gradually converged, so that conceptualizations of peace – and operationalization of those concepts through peacekeeping – now regularly make reference to ideas of development and the realization of development goals. Thus, at a conceptual level, we see coherence between UN peacekeeping and development.

Second, despite conceptual alignment, there has been variation over time in the degree to which the UN has, in practice, incorporated and prioritized development activities in its peacekeeping operations. After initially bracketing development in favour of narrow, state security-focused mandates, UN peacekeeping missions steadily expanded their activities after the Cold War to include a range of development goals in their mandates, development projects in their activities, and development agencies in their cooperative arrangements. As such, by the early 2000s, development work had become a central component of UN peacekeeping operations. While this remains the case, a number of recent UN missions have prioritized ‘hard’ security goals over development activities; largely because those missions have been deployed to insecure environments, where immediate concerns over civilian protection and the (forceful) management of armed non-state actors have taken precedence. Within such contexts, the UN’s development work has persisted alongside peacekeeping but, on occasion, it has arguably been leveraged in support of the security goals of PKOs.

In the sections that follow, we unpack these ideas by first introducing the concepts and principles of peace(keeping) and development. After a brief methodological discussion, we then use original quantitative and diverse qualitative indicators to map the evolution of development activities in and alongside UN peacekeeping over four distinct periods: during the Cold War (1948–1988); after the Cold War (1989–1998); during the decade that followed (1999–2009); and over the past decade (2010–2019). We then offer concluding thoughts on peacekeeping, development, and the academic study thereof.

Peacekeeping and development: concepts and principles

To appreciate the relationship between UN peacekeeping and development activities, we first consider the degree to which the concepts and principles that underpin the respective practices cohere.

Conceptualizing peace(keeping) and development

Peacekeeping is fundamentally concerned with maintaining peace among parties to an armed conflict. But what is the nature of the ‘peace’ that peacekeeping seeks to establish and maintain? There is an extensive literature on the concept of peace and how the term is operationalized within the practice of peacekeeping (e.g. Caplan, Citation2019; Diehl, Citation2019; Richmond, Citation2014), and a few basic observations can be drawn from that literature. To begin, it should be noted that peace is a contested concept (Gledhill & Bright, Citation2019, pp. 260–261) and there is no consensus among scholars or practitioners as to the precise characteristics of peace. At a minimum, peace is understood as the absence of violent conflict – what is often referred to as ‘negative peace’ (Galtung, Citation1969). However, many scholars view this as too limited and favour a broader notion – ‘positive peace’ – which involves not only the absence of violent conflict but also the reform of repressive social, political, and economic institutions (i.e. sources of ‘structural violence’), with a view to building societal trust, mutual respect, and good will (Davenport, Melander, & Regan, Citation2018; Diehl, Citation2016; Galtung, Citation1969). Other, more finite, conceptualizations of peace have been put forward over time (e.g. Klein, Goertz, & Diehl, Citation2008), but negative and positive peace have remained the dominant understandings of the term.

The notion of development is a similarly contested concept. During much of the Cold War, the term was understood largely through the prism of national macroeconomic indicators such as economic growth and productivity (Degnbol-Martinussen & Engberg-Pedersen, Citation2003, pp. 25–27; Goldin, Citation2018, p. 4). Over time, however, critics observed that while economic growth may increase national income, this does not necessarily translate into improvements in poverty reduction or the fulfilment of basic needs. Following these criticisms and influenced by the works of Amartya Sen and Mahbub ul Haq, among others, the more ‘people-centred’ notion of human development gained currency (Browne, Citation2011, pp. 48–50; Goldin, Citation2018, pp. 9–10). In 1990, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) adopted the concept, which it defined as ‘a process of enlarging people’s choices’ (UNDP, Citation1990, p. 10). While this formulation was evidently broad, the concept was given specification through the concurrent introduction of the Human Development Index (HDI), which was a quantitative measure of development that incorporated indicators of education and health (life expectancy), alongside traditional economic measures (UNDP, Citation1990). Subsequent UNDP reports and scholarly works then expanded the idea of human development to include political freedoms, human rights, and more (Degnbol-Martinussen & Engberg-Pedersen, Citation2003, p. 32; Ranis, Stewart, & Samman, Citation2006). Over recent decades, issues of environmental sustainability, and social and gender inequalities have been increasingly important to understandings of development and associated policy agendas (Sachs, Citation2012).

As the concepts of peace and development were revised and expanded, so too did policy actors and scholars begin to rethink the idea of ‘security’, which is where peace and development arguably intersect. Throughout the Cold War (and earlier), security was primarily understood in state-centric terms (see Buzan & Hansen, Citation2009) – as the physical security of the state from external aggressors. However, with the reduction of Cold War tensions and an associated decrease in the threat of interstate conflict, policy actors and scholars alike began to shift the focus of security away from the stability of states toward the safety and well-being of individuals within those states – giving rise to the notion of human security (Jackson & Beswick, Citation2018, pp. 8–13; Krause & Jütersonke, Citation2005, pp. 456–457; MacFarlane & Khong, Citation2006). The UNDP’s 1994 Human Development Report identified seven dimensions of human security: economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political (UNDP, Citation1994). Although the concept was criticized by some analysts for being too eclectic and imprecise (Paris, Citation2001), it was widely adopted (in rhetoric, if not reality) and it has remained important to the way that some government departments, international organizations, and scholars think about security.

Through their respective reformulations, the ideas of peace, development, and security have reached a point of broad conceptual coherence (understood as logical consistency). At base, that coherence is underwritten by a common shift away from state-centrism toward a more cosmopolitan approach, which emphasizes the protection, opportunities, and advancement of all individuals. Within this people-centred framework, the goals and aspirations of a positive peace are largely consistent with those of development; indeed, positive peace can even be understood as a combination of physical security plus human development (Barnett, Citation2008; Jackson & Beswick, Citation2018, pp. 12, 88). The concept of negative peace, meanwhile, does not explicitly incorporate ideas or goals related to development, but negative peace and development are seen as intertwined: negative peace facilitates development while development facilitates negative peace (Stewart, Citation2004; also see overviews in Uvin, Citation2002). While some critics express concern that this thinking risks subsuming development under the political and state security interests of powerful actors (see Chandler, Citation2007, p. 363; Hughes, Citation2016), there remains a common view that peace, security, and development are conceptually inter-related (World Bank, Citation2011; United Nations, Citation2005). Does this conceptual coherence, however, extend to commonality in the principles that guide peacekeeping and development in a way that would, in theory, facilitate operational alignment between the UN’s peacekeeping and development activities, in practice?

The principles of peacekeeping and development

While peacekeeping is a prominent activity of the United Nations, there is no specific mention of it in the UN Charter. There is also no formal peacekeeping doctrine, although the core principles of UN peacekeeping have been codified in a document known informally as the ‘Capstone Doctrine’. This document shows that, on paper, the basic principles of peacekeeping have remained largely unchanged since they were first established in the 1950s. Those principles are: consent of the parties to a conflict to the deployment of a PKO; impartiality of the peacekeeping force; and a minimal use of force on the part of the peacekeepers (United Nations, Citation2008, pp. 31–35). Throughout the Cold War, most UN PKOs adhered to a fairly strict interpretation of these principles. As we illustrate below, however, this has not always been the case over the past three decades; rather, as UN peacekeeping missions have deployed to increasingly insecure and unstable contexts in recent decades, consent, impartiality, and limited use of force have all become somewhat malleable guidelines for engagement (Peter, Citation2019).

In contrast with UN peacekeeping, it is hard to discern a common set of underlying principles that guide the wide range of actors – UN and otherwise – that are engaged in development assistance. Alongside the UNDP, the UN itself has a number of agencies that work on development in areas such as health, food security, education, and gender equality. Beyond the UN, donor states, non-governmental organizations, private actors, and multilateral organizations such as the (UN-affiliated) World Bank and regional development banks provide aid, loans, and technical assistance for development projects (Goldin, Citation2018, p. 68). These diverse actors are driven by equally diverse interests and, as a result, they have been guided by diverse operating principles. Still, one arguable commonality is that development agencies have often been inherently political. This is partly because the formulation and delivery of development assistance entails normative choices about questions of social, political, and economic organization.Footnote2 It is also because bilateral aid programmes have, over decades, aimed to realize the political objectives of donor states as well as welfare goals – whether it was establishing ties with former colonies in the wake of decolonization or enlisting support for socialism (by the Soviet Union) or anti-communism (by the United States) during the Cold War (Degnbol-Martinussen & Engberg-Pedersen, Citation2003, pp. 8–9; Wickstead, Citation2015). Multilateral development organizations have also not been immune to political ideas and interests of the day; consider, for example, the commitment of Bretton Woods institutions to structural adjustment programmes during the 1980s, articulating the neo-liberal ‘Washington Consensus’ of the time (Browne, Citation2011, pp. 40–42; Wickstead, Citation2015, pp. 24–25).

Despite the absence of overt common principles guiding development agencies, current UN development efforts can be seen as underwritten by the principles of sustainability, universalism, and integration. Sustainability refers to efforts to satisfy the needs of the present generation without adversely affecting the welfare of future generations (UN General Assembly, Citation1987). Universalism entails consideration for the welfare of all members of society across the globe, not just the few (UNDP, Citation2016). And integration is an approach that seeks to identify interconnected aspects of the UN’s development goals/projects while addressing obstacles to those goals in a way that connects various development actors (UNDP, Citationn.d.-a). These three principles are reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which UN member states adopted unanimously in 2015, albeit after consultation, debate, and some contestation (Farrell, Citation2020; UN General Assembly, Citation2015). These goals build upon their predecessors (the Millennium Development Goals) to provide a common point of reference for UN agencies undertaking development work. The SDGs also provide a framework for potentially deepening cooperation between the UN’s peacekeeping and development programmes; not only is SDG 16 concerned with promoting ‘Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions’ (UNDP, Citationn.d.-b) but the SDGs are credited with informing and inspiring the UN’s commitment to sustaining peace, which is an initiative that aims to build cooperation between the UN’s peace and development actors in support of conflict prevention and management (De Coning, Citation2018).

Over time, such cooperation has existed to greater and lesser degrees. On occasion, UN agencies involved in peace and development, respectively, have had ‘separate procedures, financial arrangements and decision making forums’ (Griffin, Citation2003, p. 199). At other times, however, the activities of UN peacekeepers and UN development agencies have been integrated under a single organizational structure (Boutellis, Citation2013). To document this variation, the next section maps the degree to which development-focused goals, activities, and agencies have been incorporated into UN peacekeeping throughout the 70+ years of UN PKOs. We divide our analysis into four time periods, which vary according to the level of observed development activity in peacekeeping: we first look at the Cold War era (1948–1988), when ‘traditional’ peacekeeping largely bracketed questions of development; we then examine the expansion of peacekeeping and the addition of development activities to PKOs during the early post-Cold War period (1989–1998); the subsequent section focuses on 1999–2009, when peacekeeping witnessed the regular integration of development actors and activities into mission structures; and the final section looks at the past decade (2010–2019), when peacekeeping operations and associated development projects have focused on ‘stabilizing’ conditions on the ground in insecure contexts.

Peacekeeping and development: evolving practice

For each of the periods we consider, we combine qualitative narratives of development and peacekeeping with findings from two sets of quantitative content analyses: one that looks at UN Security Council (UNSC) resolutions mandating the establishment of peacekeeping missions, and a second that examines progress reports on missions that UN Secretaries-General (SG) have produced throughout the course of PKOs. All peacekeeping operations led by the UN between 1948 and 2019 (71 in all) are included in our quantitative analyses.

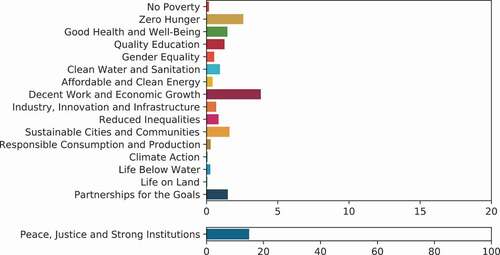

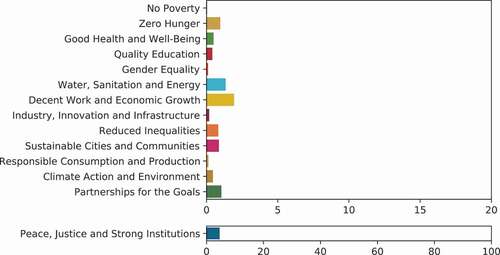

Our documentation of UNSC resolutions allows us to illustrate the range of tasks, including development-related activities, that peacekeeping operations have been formally mandated to realize between 1948 and 2019. To generate our results, which are presented in , we manually coded the initial resolutions that established each UN mission; only in cases of substantive changes to the mandate were later resolutions coded as well.Footnote3 Overall, 72 different tasks were established, which were grouped into 11 categories – some of which relate to the ‘hard’ security roles of peacekeeping missions and others that relate to development. Coding was cross-checked against the inventory of UN peace operations produced by Franke and Warnecke (Citation2009), the case study chapters in Koops, Tardy, MacQueen, and Williams (Citation2015a), and data provided on each UN mission website.

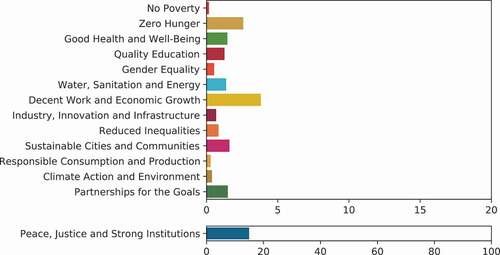

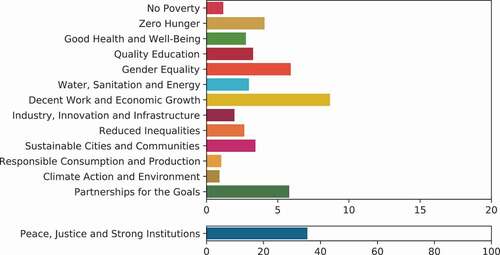

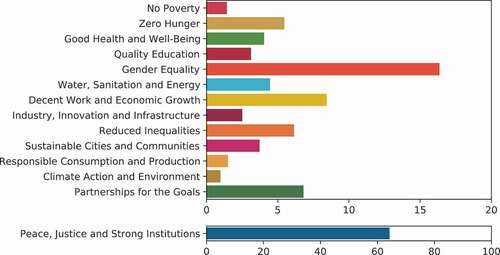

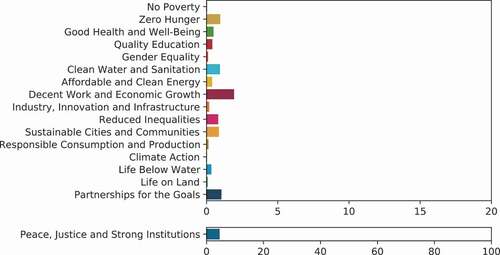

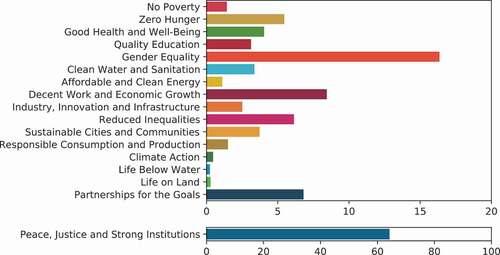

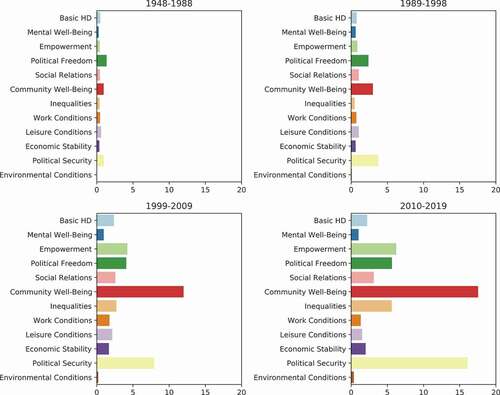

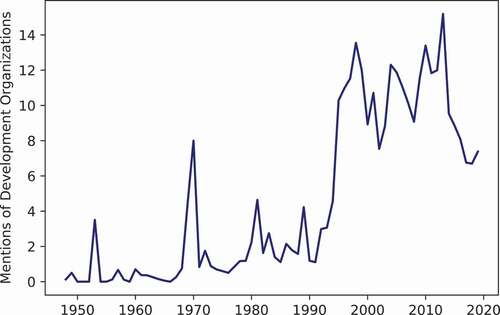

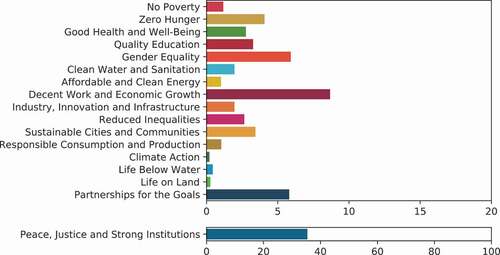

Our second analysis, which looks at the content of SG progress reports, provides insight into development-related activities, interactions with development agencies, and development-related discussions that UN PKOs have pursued as missions have unfolded. For this analysis, 2,310 SG progress reports were collected from publicly-accessible, online repositories – an almost complete compilation of all reports.Footnote4 The reports were converted to text using optical character recognition, and the frequency of keywords relating to development themes in each report was then counted using automated pattern recognition.Footnote5 The keywords we chose were based on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals and their corresponding targets, as defined in the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN General Assembly, Citation2015); a list of all keywords is included in the Appendix and replication data is available in the supplementary files.Footnote6 , below, present aggregated results for each of the four periods of peacekeeping that we consider.Footnote7 For each period, we display the average number of appearances of keywords that correspond to SDGs, per SG progress report, for all reports published within the time period in question.Footnote8 Recognizing that the concept and characteristics of ‘development’ are contested, the coding process was also completed with keywords based on human development indicators, as operationalized by Stewart, Ranis, and Samman (Citation2018). This analysis, which can be found in the Appendix, gives rise to findings that are complementary to (and consistent with) results from our primary analysis, presented below. As a qualification, we note that our quantitative content analysis does not allow us to judge whether a UN PKO directly realized (or collaborated on) a development-related project or whether it merely observed and reported on development activities led by other organizations. It does, nevertheless, still provide insights into the importance that UN peacekeeping operations have attached to development goals, over time.

Figure 1. Mandated activities in the initial resolutions establishing United Nations peacekeeping missions, 1948–2019

Evolution of development in peacekeeping: 1948-1988

As originally conceived in 1948, and then operationalized throughout the Cold War period, UN PKOs were fairly limited in scope. With some notable exceptions (discussed below), early missions were mandated to pursue narrow security roles and had no development goals associated with them, as shown in . The limited incorporation of development activities and interactions into UN PKOs at this time is also reflected in , which summarizes references to development activities in progress reports of peacekeeping missions throughout this period. Only with the end of the Cold War would UN peacekeeping routinely assume broader development-related responsibilities, as the strategic context within which they were deployed underwent significant changes.

Figure 2. References to development activities in UN PKO progress reports, 1948–88.Footnote9

The advent of UN peacekeeping in 1948 represented an ad hoc response by the UN Secretary-General to regional conflicts that erupted in the early years of the organization, beginning with the Indo-Pakistani war of 1947 and the Arab-Israeli war of 1948. In both cases, the UN brokered a ceasefire and then deployed unarmed peacekeepers to monitor the ceasefire, pending a final negotiated settlement among the parties to the conflict (settlements which remain elusive to this day) (Goulding, Citation1993). This improvised start to peacekeeping came about, in part, because major powers could not agree on implementation of many of the provisions for collective security in the UN Charter (see United Nations, Citation1945, Chapter 7) and multilateral UN peacekeeping created opportunities to remove those powers from direct engagement in regional conflicts, thus avoiding further inflaming Cold War tensions. In support of this dynamic, the UN Secretary-General made deliberate efforts to recruit peacekeepers from small and middle-sized powers (see, for example, UN General Assembly, Citation1958) rather than from among the permanent members of the Security Council, although there were exceptions – notably the deployment of British peacekeepers in Cyprus (UNFICYP) and French peacekeepers in Lebanon (UNIFIL I).

Monitoring, observation, and the interposition of peacekeepers between belligerent parties were the primary peacekeeping activities of the Cold War period and, since UN PKOs were ordinarily deployed in response to conflicts between (rather than within) states (Diehl & Druckman, Citation2017, p. 251), there was limited scope for domestic-level interventions – including on the development front. However, there were exceptions, which previewed a move toward more expansive peacekeeping operations following the Cold War. Specifically, the United Nations Operation in the Congo (1960–64), which originated with a request from the Congolese government for military assistance to facilitate the withdrawal of Belgian troops and other foreign military personnel, evolved into a wider operation after the internal situation deteriorated (Berdal, Citation2008). When the Congolese administration collapsed, the UN dispatched civilian experts to help ensure the continued provision of essential public services and to provide a longer-range programme of training and assistance – including in areas often associated with development such as agriculture, communications, education, finance, foreign trade, health, labour, ‘magistrature’, natural resources, and public administration (United Nations, Citation1960, p. 2; House, Citation1978). Another operation, the United Nations Security Force in West New Guinea (UNSF), was deployed between October 1962 and April 1963 to facilitate the withdrawal of the Netherlands from its former colony. UNSF served as the ‘policing and enforcement backstop’ (MacQueen, Citation2015, p. 171) to the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA), which was responsible for administration of the territory pending determination of its future status (it would later be absorbed by Indonesia). Not until the post-Cold War territorial administrations of Eastern Slavonia (UNTAES), Kosovo (UNMIK), and East Timor (UNTAET) would the United Nations exercise such sweeping authority again (Wilde, Citation2008).

With the exception of these two expansive missions, however, the nature of the peace that UN peacekeeping sought to establish in these early years was generally ‘negative’ – maintenance of a cessation of hostilities while negotiations were undertaken in pursuit of a mutually acceptable political settlement. Paradoxically, the relative success of early peacekeeping efforts on this front proved to be a limitation insofar as the stability achieved sometimes reduced pressure to produce longer-term solutions (Roberts & Kingsbury, Citation1993), resulting in peacekeeping missions of long duration in the Middle East (Lebanon, Syria/Israel), Cyprus, and South Asia (India/Pakistan). Where UN PKOs became entrenched in this way, however, their activities generally remained limited and did not extend to the development arena. This changed with missions that were established after the Cold War.

Evolution of development in peacekeeping: 1989-1998

With the end of Cold War hostilities, UN peacekeeping expanded markedly in terms of both the number and scope of operations. In the 40 year period between 1948 and 1988 (inclusive), the United Nations launched 15 peacekeeping operations; in the subsequent 10 years, 34 new operations were established (UN Peacekeeping, Citationn.d.-a). The reason for this expansion was, in part, a dramatic shift in the strategic environment: the end of superpower competition led to greater cooperation on the Security Council in support of efforts to build peace, security, and stability (United Nations, Citation1992).

Growth in the number of operations was matched by an expansion in the mandated remit of these missions (see ). Alongside more ‘traditional’ operations, such as the observer missions in Iraq and Kuwait (UNIKOM) and Georgia (UNOMIG), new operations assumed a much wider range of responsibilities, including the organization and monitoring of elections; promotion and protection of human rights; assistance with the delivery of humanitarian aid; disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of armed groups; and training of police forces (Bellamy, Williams, with Griffin, Citation2010; Ratner, Citation1995/96). Many of these new responsibilities had a direct bearing on development, such as the administration of natural resources (UNTAES in Eastern Slavonia), the facilitation of land transfers (ONUSAL in El Salvador), and activities to promote economic rehabilitation (UNSMIH in Haiti). This increasing interest in development is reflected in our content analysis of issues discussed in mission progress reports for this period ().

The inclusion of development-related responsibilities in peacekeeping reflected a growing recognition of the important role that development can play in the consolidation of (positive) peace in the aftermath of armed conflict (Ginifer, Citation1996, p. 4; Dijkzeul, Citation1998), although in a number of cases UN peacekeepers were also deployed to regions with ‘unfinished conflicts’ – such as Somalia – where it was difficult to establish even negative peace (United Nations, Citation2000, §. 20; Hultman, Kathman, & Shannon, Citation2019). The emerging emphasis on development also reflected broad acceptance of what is commonly referred to as the liberal peace theory, which argued for the promotion of liberal democratic, market-oriented societies in war-torn states, in the belief that these societies would be more peaceful in their inter-state relations and less prone to internal violence (Paris, Citation2004, p. 42). As a consequence, UN peacekeeping operations were sometimes mandated to facilitate the formation of political parties, to promote freedom of expression, and to oversee or conduct competitive elections. In the economic arena, meanwhile, UN peacekeeping operations worked to diminish the role of the state and to enlarge the scope for private enterprise. Proponents of this approach, however, tended to ignore the potentially destabilizing effects of political and economic liberalization for societies emerging from violent conflict (see Paris, Citation1997; Pugh, Citation2002). Development activities can indeed play an important role in consolidating peace, critics would argue, but they have to be sensitive to the sometimes harmful impact of liberalization, as well as to the power structures that fuel violent conflict in the first place and often persist in the post-war period (Berdal & Zaum, Citation2013).

During the 1990s, thus, there began to be something of a convergence of UN peacekeeping and development activities as part of a larger effort within the UN to achieve harmonization and coordination across the different dimensions of peacekeeping operations. In his 1997 report, Renewing the United Nations – A Programme for Reform, the newly-appointed UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan called for a more integrated United Nations, to give the organization ‘greater unity of purpose, coherence of effort’ (UN General Assembly, Citation1997, §34), particularly in relation to peacekeeping, peacebuilding, and development. The principal practical effect would be to confer authority over all UN entities in the field to Special Representatives of the Secretary-General (SRSGs, who lead peacekeeping missions) (UN General Assembly, Citation1997, §119). Despite widespread recognition of the need for an integrated approach and the adoption of some institutional reforms, however, bureaucratic obstacles to integration would prove to be difficult to overcome.

Ambition for, if not by, the United Nations in this period resulted in the establishment of some very large and complex operations, notably in Namibia, El Salvador, Cambodia, Mozambique, and Eastern Slavonia. In some cases, however, ambition exceeded capabilities, such as in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR) failed to provide adequate security for the civilian population, most evidently in the massacre of more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims, mostly men and boys, at Srebrenica in July 1995 (UN General Assembly, Citation1999). The Panel on United Nations Peace Operations, reviewing the UN’s performance at the end of the decade, would therefore go on to stress the ‘pivotal importance of clear, credible and adequately resourced Security Council mandates’ (United Nations, Citation2000, §6) – an admonition that would be repeated as the scope of peacekeeping continued to expand over the decade that followed.

Evolution of development in peacekeeping: 1999-2009

Following attacks on UN peacekeepers in Somalia and the failure to protect civilians in Rwanda and Bosnia, there was a contraction in UN peacekeeping in the mid-to-late 1990s (Bellamy et al., Citation2010, pp. 119–120). However, the appointment of Kofi Annan as Secretary-General in 1997 gave new impetus to peacekeeping and, in 1999, the Security Council approved four new deployments – in Kosovo, East Timor, Sierra Leone, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (Koops, Tardy, MacQueen, & Williams, Citation2015b, p. 607). These missions, and others deployed over the following decade, incorporated development goals into their mandates to an unprecedented level, as evidenced by . Those mandates underwrote a significant expansion in development-related activities and collaborations alongside peacekeeping between 1999 and 2009, as suggested by the content of mission progress reports during this time, seen in .

The expansion of development in peacekeeping during the 2000s grew out of a confluence of the national security interests of powerful UN member states, evolving conceptualizations of development and peace/security, and institutional reforms within the UN itself. In terms of state interests, the late 1990s and 2000s saw the emergence of a view – particularly in the ‘Global North’ – that there was a logic to supporting the political, social, and economic development of fragile or ‘failed’ states (Fukuyama, Citation2004; Rotberg, Citation2002). That logic was built on the belief that these territories were susceptible to armed conflict (Fearon & Laitin, Citation2003), vehicles for trafficking and organized crime (Takeyh & Gvosdev, Citation2002, p. 99), and havens for global terrorist organizations (Council of the European Union, Citation2003; President of the United States, Citation2002). Support for capacity-building in fragile states, meanwhile, resonated with ideas about paths to development that had consolidated within organizations such as the World Bank, which highlighted the importance of institutions and governance for development (Goldin, Citation2018, p. 78). Development agencies and scholars also recognized that conflict, security, and development can be fundamentally intertwined (Browne, Citation2011, p. 83; Griffin, Citation2003, p. 203; Stewart & Fitzgerald, Citation2000), and this view was echoed by Kofi Annan shortly after he took over as UN Secretary-General (UN Secretary-General, Citation1997). Similar thinking also appeared in the final report of the aforementioned UN Panel on Peace Operations (commonly known as the ‘Brahimi Report’), which proposed the creation of ‘integrated mission task forces’ that would bring together diverse UN development and peacebuilding actors when planning multidimensional peacekeeping operations (United Nations, Citation2000, pp. 34–36).

While publication of the Brahimi Report in 2000 gave impetus to mission integration, cooperative arrangements between peacekeepers and development-focused agencies were already evidenced in two missions that were mandated in 1999: UNMIK (Kosovo) and UNTAET (East Timor). Both established ‘transitional civil administrations,’ which saw UN PKOs act as provisional governing authorities (United Nations, Citation2000, p. 13). In Kosovo, this arrangement gave UNMIK power to oversee a number of development-focused programmes, including support for public health and education, reconstruction of industry and infrastructure, and the development of national-level financial institutions (Caplan, Citation2015, Citation2005; Del Castillo, Citation2008; UN Security Council, Citation1999a). In practice, however, development projects in Kosovo were often managed by partner organizations, including the European Union (which was responsible for economic reconstruction), the OSCE (which led on democratization), and other UN agencies (which managed humanitarian activities) (Caplan, Citation2015, p. 619; Del Castillo, Citation2008). In East Timor, UNTAET was mandated to facilitate a wide range of activities alongside its military and policing roles, including developing civil and social services, coordinating humanitarian assistance, and establishing conditions for sustainable development (UN Security Council, Citation1999b). As the de facto government of East Timor, UNTAET also negotiated the terms of a human development project with the World Bank (Chopra, Citation2000, p. 30) although, as Lise Howard notes (Citation2008, p. 288), most economic and social development efforts were actually managed by the Bank, which supported a range of programmes related to ‘health, education, agriculture, community development, private sector development, water and sanitation and transport’ (Rohland & Cliffe, Citation2002, pp. 26–27). These roles for the World Bank in East Timor, and the roles of diverse organizations alongside UNMIK’s operations in Kosovo, were indicative of a broad and sustained increase in the level of engagement of UN PKOs with the UN’s development organizations from around this time onwards, as shown in of the Appendix, which reports the average number of times such organizations are mentioned in mission progress reports between 1948 and 2019.

Beyond particular arrangements in Kosovo and East Timor, a commitment to mission integration during this period saw UN PKOs become increasingly involved in the management and/or delivery of development projects elsewhere. While there was variation in the depth and form of integration (Adolfo, Citation2010, pp. 25–26), fully integrated operations – such as the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) – brought UN development and humanitarian agencies under the direct command of the head of the peacekeeping mission (Hull, Citation2008, pp. 22–23). In Liberia, this arrangement saw the mission take a leadership role in numerous programmes that had development goals. In terms of economic development, for example, UNMIL worked with UNDP to facilitate the demobilization and societal reintegration of former combatants (Munive & Jakobsen, Citation2012), and it supported efforts from the international community to reform state financial institutions (UN Security Council, Citation2005, pp. 11–12). The mission boosted participation in political and community life by facilitating elections and other forms of political engagement (Farrall, Citation2012, pp. 329–330; Mvukiyehe, Citation2018) and it worked with UNICEF, UNDP, and UN Women to introduce gender-focused reforms to policing (Karim, Citation2020, pp. 61–62). UNMIL also oversaw a vast number of ‘Quick Impact Projects’ (QIPs), many of which had development goals, such as the rehabilitation of schools, healthcare facilities, and local infrastructure (UNMIL, Citationn.d.). Alongside these PKO-led projects, the World Bank continued to play an active role in promoting economic recovery and development in post-conflict Liberia (Independent Evaluation Group, Citation2013).

Other UN peacekeeping missions established after 1999 also integrated development activities and actors into their operations to varying degrees. As with the 1989–98 period, support for political participation was particularly common, with UN peacekeeping missions working with UNDP (and other organizations) to facilitate elections in Cȏte d’Ivoire (Flores, Citation2012), Haiti (Faubert, Citation2006, Section 4.4), Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL, Citation2005), and beyond. Human rights protection was also written into the initial mandates of most UN PKOs established during this period (see ), and support for humanitarian assistance (as a precursor to development) was mandated for new PKOs of the time, although concerns were raised that the integration of humanitarian activities into peacekeeping risked politicizing and securitizing relief work (see Harmer, Citation2008; Stoddard & Harmer, Citation2006). Those concerns would intensify as some peacekeeping operations adopted a more ‘robust’ posture over the decade that followed.

Evolution of development in peacekeeping: 2010-2019

UN peacekeeping missions have continued to support and pursue a wide range of development activities over the past decade. During that time, however, development agendas have, on occasion, played something of a supporting role to security-focused activities (Curran & Hunt, Citation2020; Muggah, Citation2014a; Peter, Citation2019, pp. 36–40) as PKOs have increasingly deployed to contexts of active and ongoing conflict (Bellamy & Hunt, Citation2015, p. 1281; United Nations, 2015a, p. x). This observation is partly reflected in , which shows that references to most development activities have remained consistent with the 1999-2009 period, but there has been a sizable increase in discussions of ‘peace, justice and strong institutions’ over the past decade. This suggests a rise in attention given to negative peace and ‘hard’ security concerns, alongside recognition that state capacity and institutions are central to long-term development (Acemoglu, Johnson, & Robinson, Citation2005). There has also been a continued rise in emphasis on gender-focused reforms, in line with the understanding that gender equality is central to both peacebuilding (UN Security Council, Citation2000) and development (UNDP, Citationn.d.-c).

To identify drivers of the shift towards ‘hard’ security within some UN PKOs, it is (again) useful to consider evolving state interests, ideas about peace and development, and reforms to UN institutions. In terms of interests, the UN and powerful member states have continued to see a need to ‘stabilize’ fragile states, which are viewed as sources of instability and violent extremism (Karlsrud, Citation2017, Citation2019). For the United States, this view was partly informed by experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan (see Muggah, Citation2014b, pp. 1–2), while European states have been concerned that conflicts in the Sahel and beyond may have spill-over consequences for migration to Europe (Karlsrud, Citation2015, p. 46), and increasingly-active regional, subregional, and state actors in Africa have been keen to contain civil conflicts on the continent (De Coning, Citation2017). This continued interest in shoring-up fragile states has resonated with evolving ideas about development, as articulated in the World Bank’s 2011 World Development Report and, later, the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, both of which reaffirm the view that physical security and development are interdependent and jointly reliant on strong institutions and good governance (World Bank, Citation2011; United Nations, Citationn.d.-b). The absence of such governance, meanwhile, has been seen as a threat to the security of civilians, whose physical protection has become central to UN peacekeeping (Bellamy & Hunt, Citation2015, pp. 1279–1280; United Nations, Citation2015-a, p. ix). However, using force to protect civilians (typically against armed non-state actors), presents operational challenges for the UN since it can blur the line between impartial, consent-based peacekeeping and partial, forceful conflict ‘management’ (Hunt, Citation2017; Peter, Citation2019). By way of institutional response, the UN Security Council has shown itself willing to authorize regional and/or state-led militaries to deploy and engage ‘robustly’ in advance of, or alongside, UN peacekeepers (De Coning, Citation2017; Van der Lijn, Citation2019). As independent actors, these militaries can use force in ways that may not be consistent with UN PKO principles.

This latest evolution of peacekeeping and development has been framed through the concept of ‘stabilization,’ with missions in the DRC, Mali, the Central African Republic, and HaitiFootnote10 all branded as such. While the term itself is somewhat vague (Curran & Hunt, Citation2020; Zyck, Barakat, & Deely, Citation2014, pp. 16–17), it broadly refers to PKOs that provide protection to civilians and security for humanitarian/development activities, while also shoring up state capacity, governance, and the rule of law (Curran & Hunt, Citation2020; Muggah, Citation2014a, pp. 60–63). Conceptually, stabilization can be seen as an extension of previous efforts to amalgamate security and development, as it emphasizes ‘the interdependence of security, governance, economics and development’ (Muggah, Citation2014b, p. 4). Operationally, stabilization is effectively an extension of integrated approaches to peacekeeping since it involves coordination between military peacekeepers and various civilian actors and international agencies (Carbonnier, Citation2014, p. 35; Muggah, Citation2014a, pp. 59–62). On occasion, UN stabilization operations also work directly with host states to build state and governance capacity.

Operating under the auspices of stabilization, UN PKOs of the past decade have been mandated to perform a wide range of development-focused activities. Political participation has remained a priority, with UN peacekeeping missions facilitating elections in countries such as Mali (Lotze, Citation2015, p. 861) and the DRC, although the quality of ballots in the latter has been critiqued (Doss, Citation2015, p. 809; Von Billerbeck & Tansey, Citation2019, pp. 706–707). UN PKOs have also remained committed to promoting human rights in host states such as the Central African Republic, where MINUSCA has worked with UN Women to realize gender equality programmes (Gilder, Citation2021). A broad range of development-focused QIPs has also been realized across missions, with a view to boosting standards of living at the local level and, in so doing, winning support for peacekeeping efforts (Curran & Hunt, Citation2020, pp. 55, 58). QIPs have focused on diverse development-related goals including the supply of water and food in the DRC (Hofman, Citation2014, p. 263), healthcare and education in Mali (Lyammouri, Citation2018, p. 2), and community development and security projects in South Sudan (UN Peacekeeping, Citationn.d.-b).

While development activities have remained central to UN PKOs since 2010, the focus on stabilizing fragile and conflict-affected countries has occasionally seen security-related objectives prioritized over other, development-focused, aspects of multidimensional peacekeeping. In eastern DRC, for example, MONUSCO’s stabilization efforts were initially built on a model of ‘clear, hold, and build’ (Doss, Citation2015, p. 812)Footnote11 and, to facilitate the ‘clearing’ phase, MONUSCO incorporated a ‘Force Intervention Brigade’ in 2013, which was a military unit charged with executing ‘targeted offensive operations’ that would ‘neutralize [non-state armed] groups’ (UN Security Council, Citation2013, p. 7). While the brigade is credited with helping defeat the M23 militia (Vogel, Citation2013), the UN’s commitment to democratization and human rights in the DRC waned around the same time (Von Billerbeck & Tansey, Citation2019, pp. 709–710). In Mali, MINUSMA was initially praised for overseeing successful elections shortly after deploying in 2013 (Lotze, Citation2015, p. 861), and the mission has realized various development and humanitarian activities (see Marín, Citation2017; Van Der Lijn, Citation2019). In 2014, however, a Security Council resolution listed ‘Security, Stabilization and protection of civilians’ (original emphasis) as a priority task (UN Security Council, Citation2014, p. 6). Such prioritization has unnerved some in the humanitarian community, who have raised concerns that MINUSMA’s military actions – and its support for French and regional forces on the ground in Mali (see Karlsrud, Citation2017; Van Der Lijn, Citation2019) – threaten to undermine local perceptions of the neutrality and impartiality of the diverse international humanitarian actors operating in Mali (Marín, Citation2017). Within such a securitized context, Tronc et al. argue, ‘short-term security gains have been prioritized over more extensive, long-term, inclusive, bottom-up peacebuilding efforts’ (Tronc, Grace, & Nahikian, Citation2019, p. 29).

Conclusion

Do UN peacekeeping and development activities combine to constitute a coherent approach to building sustainable peace? At a conceptual level, yes; positive peace and human development both embody the idea that individuals should have opportunities to flourish and realize their potential. In practice, such opportunities are seen to exist within contexts of physical security, where there are also good governance, human rights protection, and socio-economic structures that afford individuals access to services that open up life opportunities. Given this conceptual coherence, it is not surprising that there has also been convergence in the practice of UN peacekeeping and development assistance over recent decades, as development activities and agencies have been steadily integrated into the mandates, operations, and cooperative arrangements of UN peacekeeping missions. Integration has been built, in part, on the belief that negative peace creates institutional space for activities that advance development, while development and an expansion of life opportunities reduce the likelihood that negative peace will break down. In countries such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Timor-Leste, this logic has underwritten broadly effective peacekeeping interventions.

The interdependence and mutually reinforcing nature of physical security and human development suggest that UN peacekeeping operations should strive for a balance between development and security goals. Over the past decade, however, this has not always been the case; rather, as UN missions have deployed to increasingly volatile security environments, so too have peacekeeping operations increasingly prioritized ‘hard’ security goals and the stabilization of state structures – albeit with a view to creating space and opportunities for long-term peacebuilding and development efforts to then advance (see United Nations, Citation2015-b). While it remains to be seen whether stabilization efforts will indeed facilitate long-term human and economic development, it seems clear that development activities will continue to be part of UN peacekeeping for the foreseeable future. Indeed, noting that ‘strengthening capacities … with regard to the humanitarian-development-peace nexus has been central to United Nations reform efforts’ (United Nations, Citation2020, p. 14), the 2020 Report of the UN Secretary-General on Peacebuilding and Sustaining Peace reiterates the UN’s commitment to a multidimensional and integrated approach to peacebuilding.

By way of conclusion, we would propose that, just as the practice of UN peacekeeping and peacebuilding has integrated diverse actors and goals, so too would the study of peacekeeping and peacebuilding benefit from integrating diverse disciplinary perspectives into a more ‘multidimensional’ approach. As it stands, those who study peacekeeping ordinarily have a background in political science and international relations, and they publish in related field journals. While there was arguably a logic to this disciplinary focus when UN peacekeeping activities were primarily aimed at maintaining negative peace between states, that logic has weakened as peacekeeping has expanded and diversified its activities. Indeed, given that peacekeeping now typically includes interventions that aim to foster human and economic development within conflict-affected states, it seems clear that academic fields that study development should also be integrated into efforts to analyse and assess peacekeeping – fields such as development studies, economics, anthropology, geography and beyond. Cross-disciplinary cooperation and collaboration will likely face some of the same institutional, organizational, and ontological barriers that the UN has encountered when trying to foster cooperation and coherence among the diverse agencies and organizations that are involved in multidimensional, integrated peacekeeping. However, if the UN has been able to make some headway on that front, then surely academics can also take further steps towards a more integrated approach to studying (development and) peacekeeping.

Developing_Peace_GCM_SCmandates_coding_REPLICATION_OK.xlsx

Download MS Excel (27.6 KB)Developing_Peace_GCM_SGreports_counts_REPLICATION_OK.xlsx

Download MS Excel (2.1 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank Alex Bellamy, Frances Stewart, Oisín Tansey, Sarah von Billerbeck, and reviewers/editors for comments on earlier drafts of this article. We also thank colleagues at Oxford and beyond for early discussions that helped shape this study. Any unintended errors, omissions, or misrepresentations are, of course, our own.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Some exceptions include De Coning, Citation2007; Griffin, Citation2003; Jackson & Beswick, Citation2018.

2. Of course, there are also normative implications regarding the ‘quality’ of the peace that peacekeeping underwrites. See Wallensteen (Citation2015).

3. Specifically, UNIFIL, UNPROFOR, UNAMIR, and MINURCAT. The assessment is based on the individual case chapters in Koops et al. (Citation2015a).

4. The collection of SG progress reports is complete for all missions except the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO). Not included are the majority of the addenda to the reports S/7930 (5 June 1967) and S/11057 (29 October 1973) which number in the thousands and were hence too numerous to collect. As these addenda are usually shorter and contain supplemental information, it can be expected that this omission in fact prevents a dilution of the results.

5. The word frequency count was automated using Python code. The code was iteratively refined to remove confounding expressions by comparing samples of the output of the automated coding with hand coding.

6. We used the SDGs as a basis for our search terms because they provide a transparent basis for identifying terms. We recognize that the SDGs were not codified until late in our period of analysis; however, the themes (and related search terms) behind the goals had previously been given attention by PKOs.

7. SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) are combined into the category ‘Water, Sanitation and Energy,’ and SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 14 (Life below Water), and SDG 15 (Life on Land) are combined into the group ‘Climate Action and Environment’ due to their thematic similarity and to improve readability. A disaggregated set of results with all 17 SDGs appears in the Appendix (see figures A1-A4).

8. Note that a number of long-standing missions span more than one of the time periods that we cover. Where that is the case, progress reports are included in the period that corresponds with the date of publication.

9. Note that, for this figure and all that follow, mentions of terms related to ‘Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions’ are presented on a separate scale, due to their high frequency relative to other categories in the later time periods that we cover below.

10. MINUSTAH in Haiti was established in 2004 and terminated in 2017 when it was replaced by a smaller, follow-on UN PKO.

11. While there has been a UN peacekeeping deployment in the DRC since 1999, the mission was renamed a ‘stabilization’ mission in 2010 as part of a wider revision to the mandate of the operation.

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. In P. Aghion & S. N. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth, volume 1A (pp. 385-472). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Adolfo, E. (2010). Peace-building after post-modern conflicts: The UN Integrated Mission (UNAMSIL) in Sierra Leone. Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency.

- Barnett, J. (2008). Peace and development: Towards a new synthesis. Journal of Peace Research, 45(1), 75–89.

- Bellamy, A. J., & Hunt, C. T. (2015). Twenty-first century UN peace operations: Protection, force and the changing security environment. International Affairs, 91(6), 1277–1298.

- Bellamy, A. J., Williams, P. D., with Griffin, S. (2010). Understanding peacekeeping. Cambridge: Polity.

- Berdal, M. (2008). The Security Council and peacekeeping. In V. Lowe, A. Roberts, J. Welsh, & D. Zaum (Eds.), The United Nations Security Council and war: The evolution of thought and practice since 1945 (pp. 175-204). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berdal, M., & Zaum, D. (2013). Power after peace. In M. Berdal & D. Zaum (Eds.), Political economy of statebuilding: Power after peace (pp. 43-68). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Boutellis, A. (2013). Driving the system apart? A study of United Nations integration and integrated strategic planning. New York: International Peace Institute.

- Browne, S. (2011). The United Nations Development Programme and system. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Buzan, B., & Hansen, L. (2009). The evolution of international security studies. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Caplan, R. (2005). International governance of war-torn territories: Rule and reconstruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Caplan, R. (2015). United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). In J. A. Koops, T. Tardy, N. MacQueen, & P. D. Williams (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of United Nations peacekeeping operations (Online). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Caplan, R. (2019). Measuring peace: principles, practices, and politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carbonnier, G. (2014). Humanitarian and development aid in the context of stabilization: Blurring the lines and broadening the gap. In R. Muggah (Ed.), Stabilization operations, security and development: States of fragility (pp. 35-55). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Chandler, D. (2007). The security–development nexus and the rise of ‘anti-foreign policy’. Journal of International Relations and Development, 10(4), 362–386.

- Chopra, J. (2000). The UN’s kingdom of East Timor. Survival, 42(3), 27–40.

- Council of the European Union. (2003). European security strategy: A secure Europe in a better world. Brussels: General Secretariat of the Council.

- Curran, D., & Hunt, C. T. (2020). Stabilization at the expense of peacebuilding in UN peacekeeping operations: More than just a phase? Global Governance, 26(1), 46–68.

- Davenport, C., Melander, E., & Regan, P. (2018). The peace continuum: What it is and how to study it. New York: Oxford University Press.

- De Coning, C. (2007). Coherence and coordination in United Nations peacebuilding and integrated missions – a Norwegian perspective. NUPI Report. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs.

- De Coning, C. (2017). Peace enforcement in Africa: Doctrinal distinctions between the African Union and United Nations. Contemporary Security Policy, 38(1), 145–160.

- De Coning, C. (2018). Sustaining peace: Can a new approach change the UN? IPI Global Observatory (24 April). https://theglobalobservatory.org/2018/04/sustaining-peace-can-new-approach-change-un/ (Accessed 16 August, 2020).

- Degnbol-Martinussen, J., & Engberg-Pedersen, P. (2003). Aid: Understanding international development cooperation. London: Zed Books.

- Del Castillo, G. (2008). Rebuilding war-torn states: The challenge of post-conflict economic reconstruction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Diehl, P. F. (2016). Exploring peace: Looking beyond war and negative peace. International Studies Quarterly, 60(1), 1–10.

- Diehl, P. F. (2019). Peace: A conceptual survey. In N. Sandal (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of international studies (Online). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Diehl, P. F., & Druckman, D. (2017). Not the same old way: Trends in peace operations. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 24(1), 249–260.

- Dijkzeul, D. (1998). The United Nations Development Programme: The development of peace? International Peacekeeping, 5(4), 92–119.

- Doss, A. (2015). United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO). In J. A. Koops, T. Tardy, N. MacQueen, & P. D. Williams (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of United Nations peacekeeping operations (Online). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Farrall, J. (2012). Recurring dilemmas in a recurring conflict: Evaluating the UN Mission in Liberia (2003–2006). Journal of International Peacekeeping, 16(3–4), 306–342.

- Farrell, M. (2020). Negotiating the Sustainable Development Goals. In K. Smith & K. V. Laatikainen (Eds.), Group politics in UN multilateralism (pp. 241-266). Leiden: Brill/Nijhoff.

- Faubert, C. (2006). Evaluation of UNDP assistance to conflict-affected countries. Case study: Haiti. New York: UNDP Evaluation Office. http://www.oecd.org/derec/undp/44826404.pdf (Accessed 4 August, 2020).

- Fearon, J., & Laitin, D. (2003). Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. American Political Science Review, 97(1), 75–90.

- Flores, F. C. (2012). Cote d’Ivoire, 2010 presidential elections: UN integrated electoral assistance case study. ACE, The Electoral Knowledge Network: http://aceproject.org/ero-en/regions/africa/DZ/cote-divoire-un-integrated-electoral-assistance (Accessed 3 August, 2020).

- Franke, V. C., & Warnecke, A. (2009). Building peace: An inventory of UN peace missions since the end of the Cold War. International Peacekeeping, 16(3), 407–436.

- Fukuyama, F. (2004). The imperative of state-building. Journal of Democracy, 15(2), 17–31.

- Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167–191.

- Gilder, A. (2021). Human security and the stabilization mandate of MINUSCA. International Peacekeeping, 28(2), 200–231.

- Ginifer, J. (1996). Development and the UN peace mission: A new interface required? International Peacekeeping, 3(2), 3–13.

- Gledhill, J., & Bright, J. (2019). Studying peace and studying conflict: Complementary or competing projects? Journal of Global Security Studies, 4(2), 259–266.

- Goldin, I. (2018). Development: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goulding, M. (1993). The evolution of United Nations peacekeeping. International Affairs, 69(3), 451–464.

- Griffin, M. (2003). The helmet and the hoe: Linkages between United Nations development assistance and conflict management. Global Governance, 9(2), 199–217.

- Harmer, A. (2008). Integrated missions: A threat to humanitarian security? International Peacekeeping, 15(4), 528–539.

- Hofman, M. (2014). The evolution from integrated missions to ‘peace keepers on steroids’: How aid by force erodes humanitarian access. Global Responsibility to Protect, 6(2), 246–263.

- House, A. H. (1978). The U.N. in the Congo: The political and civilian efforts. Washington D.C.: University Press of America.

- Howard, L. M. (2008). UN peacekeeping in civil wars. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hughes, C. (2016). Peace and development studies. In O. P. Richmond, S. Pogodda, & J. Ramović (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of disciplinary and regional approaches to peace (pp. 139-153). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hull, C. (2008). Integrated missions—A Liberia case study. Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency.

- Hultman, L., Kathman, J. D., & Shannon, M. (2019). Peacekeeping in the midst of war. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hunt, C. T. (2017). All necessary means to what ends? The unintended consequences of the ‘robust turn’ in UN peace operations. International Peacekeeping, 24(1), 108–131.

- Independent Evaluation Group. (2013). Liberia country program evaluation: 2004-2011. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

- Jackson, P., & Beswick, D. (2018). Conflict, security and development: An introduction (third edition). London and New York: Routledge.

- Karim, S. (2020). The legacy of peacekeeping on the Liberian security sector. International Peacekeeping, 27(1), 58–64.

- Karlsrud, J. (2015). The UN at war: Examining the consequences of peace-enforcement mandates for the UN peacekeeping operations in the CAR, the DRC and Mali. Third World Quarterly, 36(1), 40–54.

- Karlsrud, J. (2017). Towards UN counter-terrorism operations? Third World Quarterly, 38(6), 1215–1231.

- Karlsrud, J. (2019). From liberal peacebuilding to stabilization and counterterrorism. International Peacekeeping, 26(1), 1–21.

- Klein, J. P., Goertz, G., & Diehl, P. F. (2008). The peace scale: Conceptualizing and operationalizing non-rivalry and peace. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25(1), 67–80.

- Koops, J. A., Tardy, T., MacQueen, N., & Williams, P. D. (Eds.). (2015a). The Oxford handbook of United Nations peacekeeping operations (Online). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Koops, J. A., Tardy, T., MacQueen, N., & Williams, P. D. (2015b). Introduction: Peacekeeping in the twenty-first century: 1999–2013. In J. A. Koops, T. Tardy, N. MacQueen, & P. D. Williams (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of United Nations peacekeeping operations (Online). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Krause, K., & Jütersonke, O. (2005). Peace, security and development in post-conflict environments. Security Dialogue, 36(4), 447–462.

- Lotze, W. (2015). United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). In J. A. Koops, T. Tardy, N. MacQueen, & P. D. Williams (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of United Nations peacekeeping operations (Online). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lyammouri, R. (2018). After five years, challenges facing MINUSMA persist. PB-18/35. Rabat: OCP Policy Center.

- MacFarlane, S. N., & Khong, Y. F. (2006). Human security and the UN: A critical history. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- MacQueen, N. (2015). United Nations Security Force in West New Guinea (UNSF). In J. A. Koops, T. Tardy, N. MacQueen, & P. D. Williams (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of United Nations peacekeeping operations (Online). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marín, A. P. (2017). Perilous terrain: Humanitarian action at risk in Mali. Médecins sans Frontières. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Case-Study-03-Mali-ALTA_0.pdf (Accessed 3 August, 2020).

- Muggah, R. (2014a). Reflections on United Nations-led stabilization: Late peacekeeping, early peacebuilding or something else? In R. Muggah (Ed.), Stabilization operations, security and development: States of fragility (pp. 56-70). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Muggah, R. (2014b). Introduction. In R. Muggah (Ed.), Stabilization operations, security and development: States of fragility (pp. 1-14). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Munive, J., & Jakobsen, S. F. (2012). Revisiting DDR in Liberia: Exploring the power, agency and interests of local and international actors in the ‘making’ and ‘unmaking’ of combatants. Conflict, Security & Development, 12(4), 359–385.

- Mvukiyehe, E. (2018). Promoting political participation in war-torn countries: Microlevel evidence from postwar Liberia. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(8), 1686–1726.

- Paris, R. (1997). Peacebuilding and the limits of liberal internationalism. International Security, 22(2), 54–89.

- Paris, R. (2001). Human security: Paradigm shift or hot air? International Security, 26(2), 87–102.

- Paris, R. (2004). At war’s end: Building peace after civil conflict. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Peter, M. (2019). Peacekeeping: Resilience of an idea. In C. De Coning & M. Peter (Eds.), United Nations peace operations in a changing global order (pp. 25-44). Palgrave Macmillan/ Springer, Online.

- President of the United States (2002). The national security strategy of the United States of America (September, 2002). Washington D.C.: The White House.

- Pugh, M. (2002). Postwar political economy in Bosnia and Herzegovina: The spoils of peace. Global Governance, 8(4), 467–482.

- Ranis, G., Stewart, F., & Samman, E. (2006). Human development: Beyond the human development index. Journal of Human Development, 7(3), 323–358.

- Ratner, S. R. (1995/96). The new UN peacekeeping: Building peace in lands of conflict after the Cold War. New York: St Martin’s Press.

- Richmond, O. P. (2014). Peace: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Roberts, A., & Kingsbury, B. (1993). Introduction: The UN’s roles in international society since 1945. In A. Roberts & B. Kingsbury (Eds.), United Nations, divided world: The UN’s roles in international relations (pp. 1-62). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Rohland, K., & Cliffe, S. (2002). The East Timor reconstruction program: Successes, problems and tradeoffs (Working Paper No. 2). Conflict Prevention and Reconstruction Unit, The World Bank.

- Rotberg, R. I. (2002). Failed states in a world of terror. Foreign Affairs, 81(4), 127–140.

- Sachs, J. D. (2012). From Millennium Development Goals to Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet, 379(9832), 2206–2211.

- Stewart, F. (2004). Development and security. Conflict, Security & Development, 4(3), 261–288.

- Stewart, F., & Fitzgerald, V. (2000). Introduction: Assessing the economic consequences of war. In F. Stewart & V. Fitzgerald (Eds.), War and underdevelopment: Volume 1: The economic and social consequences of conflict(Online). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stewart, F., Ranis, G., & Samman, E. (2018). Advancing human development: Theory and practice. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stoddard, A., & Harmer, A. (2006). Little room to maneuver: The challenges to humanitarian action in the new global security environment. Journal of Human Development, 7(1), 23–41.

- Takeyh, R., & Gvosdev, N. (2002). Do terrorist networks need a home? The Washington Quarterly, 25(3), 97–108.

- Tronc, E., Grace, R., & Nahikian, A. (2019). Realities and myths of the ‘triple nexus’: Local perspectives on peacebuilding, development, and humanitarian action in Mali. Humanitarian Action at the Frontlines: Field Analysis Series, 2019 (SSRN Paper ID 3404351).

- UNAMSIL (2005). Democratic government established in Sierra Leone. Factsheet 2: Elections. https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/unamsil/factsheet2_elections.pdf (Accessed 3 August, 2020).

- United Nations. (1945). Charter of the United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/sections/un-charter/un-charter-full-text/(Accessed 3 August, 2020).

- United Nations (1960). Progress report [No. 1] on United Nations civilian operations (organization and activities) (ST/ONUC/PR.1), 24 August.

- United Nations (1992). An agenda for peace: Preventive diplomacy, peacemaking and peace-keeping ( A/47/277 - S/24111), 17 June.

- United Nations (2000). Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations ['Brahimi report'] (A/55/305-S/2000/809), 21 August.

- United Nations (2005). In larger freedom: Towards development, security, and human rights for all (executive summary). https://www.un.org/en/events/pastevents/pdfs/larger_freedom_exec_summary.pdf. (Accessed 3 August, 2020).

- United Nations (2008). United Nations peacekeeping operations: Principles and guidelines [‘Capstone doctrine’]. New York: United Nations, Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Department of Field Support.

- United Nations (2015-a). Uniting our strengths for peace – politics, partnership and people. Report of the High-level Independent Panel on United Nations Peace Operations. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations (2015-b). Challenge of sustaining peace: Report of the advisory group of experts on the review of the peacebuilding architecture (A/69/968 - S/2015/490), 30 June.

- United Nations (2020). Peacebuilding and sustaining peace. Report of the Secretary-General (A/74/976-S/2020/773), 30 July.

- United Nations (n.d.-a). What we do/United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/sections/what-we-do (Accessed 17 March, 2021).

- United Nations (n.d.-b). Peace, justice, and strong institutions: Why they matter (Sustainable Development Goals). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/16-00055p_Why_it_Matters_Goal16_Peace_new_text_Oct26.pdf (Accessed 3 August, 2020).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (1990). Human development report, 1990. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (1994). Human development report, 1994. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2016). Human development report, 2016: Human development for everyone. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (n.d.-a). SDG integration—about. https://sdgintegration.undp.org/about (Accessed 12 June, 2020).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (n.d.-b). Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-16-peace-justice-and-strong-institutions.html (Accessed 12 June, 2020).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (n.d.-c). Goal 5: Gender equality. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-5-gender-equality.html (Accessed 4 September, 2020).

- United Nations (UN) General Assembly (1958). Summary study of the experience derived from the establishment and operation of the force: Report of the Secretary-General (A/3943), 9 October.

- United Nations (UN) General Assembly (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our common future (A/42/427), 4 August.

- United Nations (UN) General Assembly (1997). Renewing the United Nations: A programme for reform. Report of the Secretary-General (A/51/950), 14 July.

- United Nations (UN) General Assembly (1999). Report of the Secretary-General pursuant to General Assembly resolution 53/35: The fall of Srebrenica (A/54/549), 15 November.

- United Nations (UN) General Assembly (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development (A/RES/70/1), 21 October.

- United Nations (UN) General Assembly (2020). Budgetary and financial situation of the organizations of the United Nations system (A/75/373), 1 October.

- United Nations (UN) Peacekeeping (n.d.-a). List of peacekeeping operations (1948-2019). https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/unpeacekeeping-operationlist_3_1_0.pdf (Accessed 17 August, 2020).

- United Nations (UN) Peacekeeping (n.d.-b). Quick impact projects for communities. https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/quick-impact-projects-communities (Accessed 16 July, 2020).

- United Nations (UN) Secretary-General (1997). Good governance essential to development, prosperity, peace Secretary-General tells international conference (Press Release SG/SM/6291-DEV/2166). https://www.un.org/press/en/1997/19970728.SGSM6291.html (Accessed 3 August, 2020).

- United Nations (UN) Secretary-General (n.d.-a). The role of the Secretary-General. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/role-secretary-general (Accessed 28 July, 2020).

- United Nations (UN) Secretary-General (n.d.-b). About the post. https://www.un.org/sg/en/dsg/dsgabout.shtml (Accessed 28 July, 2020)

- United Nations (UN) Security Council (1999a). Resolution 1244 (S/RES/1244), 10 June.

- United Nations (UN) Security Council (1999b). Resolution 1272 (S/RES/1272), 25 October.

- United Nations (UN) Security Council (2000). Resolution 1325 (S/RES/1325), 31 October.

- United Nations (UN) Security Council (2005). Ninth progress report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Liberia (S/2005/764), 7 December.

- United Nations (UN) Security Council (2013). Resolution 2098 (S/RES/2098), 28 March.

- United Nations (UN) Security Council (2014). Resolution 2164 (S/RES/2164), 25 June.

- UNMIL (n.d.). Matrix of all QIPs implemented in the 2003-2016 cycle. https://unmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/quick_impact_projects-_2003_-2016web.pdf (Accessed 3 August, 2020).

- Uvin, P. (2002). The development/peacebuilding nexus: A typology and history of changing paradigms. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 1(1), 5–24.

- Van Der Lijn, J. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness of the United Nations Mission in Mali/MINUSMA. No. 4/2019(executive summary). Oslo: NUPI.

- Vogel, C. (2013). Big victory as M23 surrenders, but not an end to Congo’s travails. IPI Global Observatory, 7 November. https://theglobalobservatory.org/2013/11/in-drc-one-militia-m23-down-49-more-to-go/(Accessed 3 August, 2020).

- Von Billerbeck, S., & Tansey, O. (2019). Enabling autocracy? Peacebuilding and post-conflict authoritarianism in the Democratic Republic of Congo. European Journal of International Relations, 25(3), 698–722.

- Wallensteen, P. (2015). Quality peace: Peacebuilding, victory, and world order. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wickstead, M. A. (2015). Aid and development: A brief introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wilde, R. (2008). International territorial administration: How trusteeship and the civilizing mission never went away. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- World Bank. (2011). World development report, 2011. Conflict, security, and development. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

- Zyck, S. A., Barakat, S., & Deely, S. (2014). The evolution of stabilization: Concepts and praxis. In R. Muggah (Ed.), Stabilization operations, security and development: States of fragility (pp. 15-34). Abingdon: Routledge.

Appendix:

‘Developing peace: The evolution of development goals and activities in United Nations peacekeeping’

John Gledhill, Richard Caplan, and Maline Meiske (University of Oxford)

1) Keywords for Quantitative Content Analysis

Below, we present the keywords (and stems) that were used in our content analysis of United Nations (UN) Secretary-General reports on the progress of all UN peacekeeping missions. The keywords are based on the Sustainable Development Goals and their corresponding targets, as defined in the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN General Assembly, Citation2015).

Table A1. SDG Keywords

2) Disaggregated References to Development Activities in UN Peacekeeping Progress Reports

In figures presented in the main paper, we aggregate SDG 6 (‘Clean Water and Sanitation’) and SDG 7 (‘Affordable and Clean Energy’) into the category ‘Water, Sanitation and Energy,’ and SDG 13 (‘Climate Action’), SDG 14 (‘Life Below Water’), and SDG 15 (‘Life on Land’) into the group ‘Climate Action and Environment’ due to their thematic similarity and to improve readability. Here, we disaggregate those categories and present separate results for all 17 Sustainable Development Goals.