?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Using a repeated cross-section data set from Ghana for 1991/1992, 1998/1999, 2005/2006, 2012/2013 and 2016/17, and a Two-Stage Least Squares estimator, this paper investigates the effect of agricultural income on remittances and consumption expenditure. It is found that households in Ghana use remittances to protect themselves from decline in agricultural income due to rainfall failure. The results suggest that a 100 Ghana Cedis decrease in agricultural income leads to a 30 Ghana Cedis increase in remittances. The results further posit that rainfall-induced agricultural income changes affect total consumption and food expenditures of rural households. A 100 Ghana Cedis decrease in agricultural income due to rainfall failure leads to a 60 Ghana Cedis fall in total consumption expenditure, and 36 Ghana Cedis fall in food expenditure of rural households. Very poor households in rural areas are found to be more vulnerable to such rainfall-driven agricultural income changes.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

African migrants migrate to other cities in their own countries, to other states within Africa, or further away from the continent to other regions. These migrants normally provide economic support to a considerable number of persons from their home villages and towns, who are either related or unrelated to them, through remittances. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognizes the contribution of migration and its associated remittances to sustainable development.

Shocks affecting agricultural production can have negative effects on the welfare of households in developing countries (Dercon & Krishnan, Citation2000). How to minimize household’s vulnerability to risks associated with agricultural income changes is therefore a major issue in many developing countries. Remittances may serve as a tool to minimize income risks in agricultural settings, especially in a developing country like Ghana, due to the heavy reliance on rain-fed agriculture. Only 0.4% of the agriculture land area under cultivation in Ghana is irrigated (MOFA, Citation2013). Thus, changes in rainfall levels may be associated with variations in production and farm incomes.

Extensive research has been done on the effect of remittances on poverty. Single country studies by Lopez-Cordova, Tokman, and Verhoogen (Citation2005) for Mexico, Lokshin, Bontch-Osmolovski, and Glinskaya (Citation2010) for Nepal, and Adams & Cuecuecha (Citation2013) for Ghana, support the poverty-reducing effect of remittances. Acosta, Calderon, Fajnzylber, and Lopez (Citation2006) use household survey data from 10 Latin American countries to show that international remittances reduce poverty by 0.4% for each percentage point increase in the remittances to GDP ratio.

Ajefu and Ogebe (Citation2019) establish that the receipt of remittances enhances the likelihood of using formal financial services, such as deposit accounts and mobile banking in Nigeria. The empirical literature on Ghana provides that recipients of international remittances spend less at the margin on food and more at the margin on investment in education, housing, and health than what they would have spent on these goods without remittances (Adams & Cuecuecha, Citation2013). However, studies that look at the relationship between rainfall-driven income and remittances are scarce.

An attempt has been made to examine the relationship between illness-driven agricultural income and remittances in Ghana (Akobeng, Citation2017b). The paper uses hospitalization due to injury or illness and visits to doctors as instruments for agricultural income. Hospitalization due to injury or illness and visits to doctors are not orthogonal to remittances. Households who receive remittances regularly are less likely to face illness due to access to more resources to provide proper nutrition and health care. By using rainfall as an instrument for total income, Yang and Choi (Citation2007) demonstrate that remittances from overseas respond to total income changes in the Philippines. The concern with their paper is that agricultural income is more strongly associated with rainfall than total income and this makes the choice of the total income a real problem.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the relationship between exogenous changes to household agricultural income, consumption expenditure and the flow of remittances. Two hypotheses are tested. First, there is a negative relationship between rainfall-driven agricultural income and remittances. Second, there is a positive relationship between rainfall-driven agricultural income and household per capita consumption expenditure.

A fundamental problem that needs to be addressed is that remittance payments and agricultural income may both be simultaneously determined. For example, productive activities financed by remittance payments may increase agricultural income thereby resulting in a positive relationship between agricultural income and remittances. Likewise, remittance receipts may reduce a household’s desire for agricultural income, leading to an inverse relationship between remittances and agricultural income. Moreover, similar factors like the type of work or agricultural activity might determine both agricultural income and consumption expenditure such that the inclusion of agricultural income in the consumption expenditure model poses an endogeneity problem.

This paper attempts to address these challenges by instrumenting agricultural income with detailed daily rainfall data across the ten administrative regions of Ghana. The paper contributes to the extant literature on the following inter-related grounds.

It provides a first-hand empirical test of the claim that remittance flows buffer economic shocks with micro-level household data for Ghana.

It extends the existing income and consumption studies (Akobeng, Citation2017a; Dercon, Hoddinott, & Woldehanna, Citation2005; Harrower & Hoddinott, Citation2005; Agarwal & Qian, Citation2014; Jack & Suri, Citation2014) by quantifying the consumption and agricultural income relationship for poor and very poor households in rural areas.

It determines rainfall and agricultural income thresholds from dry and wet season perspectives to inform agricultural planning in Ghana.

The existing few micro-level studies on remittances and poverty in Ghana depend on small and unrepresentative household surveys (Adams & Cuecuecha; Citation2013; Gyimah-Brempong & Asiedu, Citation2011; Quartey, Citation2006). This paper combines five waves of the Ghana Living Standard Survey for the years 1991/1992, 1998/1999, 2005/2006, 2012/2013 and 2016/17 with sample households of 4,552, 6,000, 8,687, 16,195 and 14,009 respectively, to chart a new course of investigation.

Section two presents the overview of remittances and household expenditure in Ghana. Section three presents the literature review. Section four presents the data and econometric methodology. Sections five and six present the results and conclusion, respectively.

Remittances and household expenditure in Ghana

As a result of the COVID-19 crisis, the World Bank reports that remittance flows to the Sub-Saharan Africa region are expected to decrease by 23.1% to reach $37 billion in 2020 (World Bank, Citation2020). Despite this decline, the report indicates that remittances are projected to perform better as a source of external financing for low-and middle-income countries than foreign direct investment.

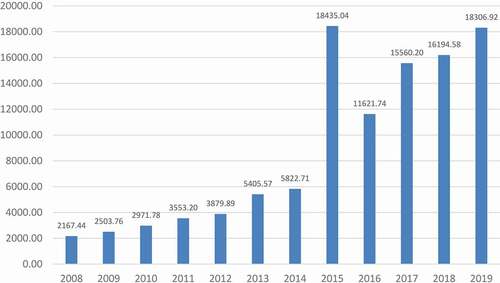

The government of Ghana considers remittances an important source of foreign exchange inflows with a high policy interest due to their poverty-reducing and growth-enhancing effects (BoG, Citation2016). demonstrates the flow of international remittances to Ghana from 2008 to 2019. The figures show that migrant remittances to Ghana increased from GH¢2167.44 million in 2008 to GH¢18435.04 million in 2015 and declined to GH¢18306.92 million in 2019. According to the BoG (Citation2016), the rapid increase in remittances in 2015 was attributed to several reasons including, rising use of formal channels, improvement in remittances data gathering by the Bank of Ghana and the growth in financial transfers by migrants. The decline in remittances to Ghana and other developing countries after 2015 was generally due to slow economic growth in Europe and other remittance-sending countries; decline in commodity prices, especially oil, which impacted remittance receiving countries; and diversion of remittances to informal channels due to controlled exchange rate regimes (World Bank, Citation2017).

Figure 1. Remittance flows to Ghana (millions of GH¢), 2008–2019.

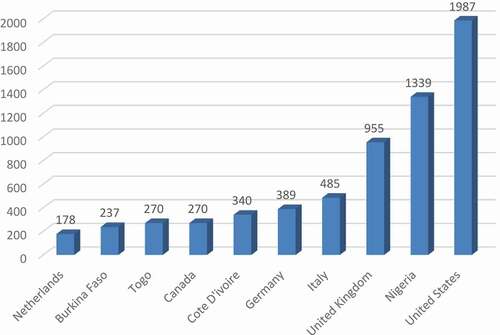

shows that the main countries of origin of international remittances to Ghana are the United States of America, Nigeria, United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, Cote d’Ivoire, Canada, Togo, Burkina Faso, and Netherlands (IOM, Citation2017; World Bank, Citation2016). These ten countries contributed 35% (GH¢6449 million) of the total remittances in 2015 (GH¢18,435.04 million). The data shows that a significant percentage of remittances to Ghana come from African countries, such as Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire, Togo and Burkina Faso.

Figure 2. Major countries of origin of remittances to Ghana in 2015 (millions of GH¢).

Households in Ghana receive remittances from other households and pay out remittances to others. According to the GSS (Citation2014) report, the estimated total annual amount of all remittances payment by households in Ghana was GH¢1,673.1 million (see ). The annual expenditure incurred by households which actually remitted was about GH¢698.7million.

Table 1. Mean annual household expenditure on and receipts from remittances and estimated total remittances by locality (Millions of GH¢).

Households in Ghana also benefit from people who are not part of their households. shows that the annual estimated total worth of remittances received in Ghana amounted to GH¢1,804 million. Annual receipt of remittances by households which actually received them was GH¢848.5 million. Households in urban Ghana received remittances worth of GH¢1,268.7 million, and households in rural Ghana received an amount of GH¢535.2 million as remittances.

Remittances and consumption theories

The remittances theory can be divided into two main areas. The first modeling is altruism, in which the sender’s utility function depends partly on the utility function of the receiver. The altruism school argues that remittance flows are seen as a mechanism to fulfil responsibility to the household based on affection towards the family (Poirine, Citation2006).

The second type of remittance modelling is christened ‘self-interest.’ Thus, remittances are utilized to some extent to satisfy the self-interest of the remitter. The self-interest motive is further classified into an ‘insurance model’ (Agarwal & Horowitz, Citation2002, p. 2033) and the second category perceives remittances as a kind of implicit loan agreement used to finance migration or education that is, for the repayments of past investments (Ilahi & Jafarey, Citation1999). The insurance model provides that the imperfect nature of institutional mechanisms for managing risk in low-income countries motivates agricultural households to self-insure themselves through the geographical dispersion of their members. In the event of transitory income shocks due to unexpected bad local conditions, families can depend on remittances from urban localities and abroad (Amuedo-Dorantes & Pozo, Citation2011; Batista & Umblijs, Citation2016; Gubert, Citation2002; Lucas & Stark, Citation1985).

Jappelli and Pistaferri (Citation2010) present a theory to predict sensitivity of consumption to unanticipated and anticipated income shocks contingent on the persistent nature of the shock and the behavior of credit and insurance markets. This current paper tests this theory by looking at the effect of rainfall-driven income changes on consumption expenditure from rural households’ perspectives.

Remittances and income shocks

Some scholars have noted the steadiness of remittances in the face of global economic downturn. Yang (Citation2011) demonstrates that, in the wake of the financial crisis between 2008 and 2009, remittances drop by 5.2% whilst foreign direct investment fell by 39.7% over the same period. Using panel data from Jamaica, Clarke and Wallsten (Citation2003) find that international remittances increased by about 25 cents for every dollar of damage that hurricanes imposed on Jamaican households. Using meteorological data on hurricanes as an instrument, Yang (Citation2008) finds that disaster damages lead to increases in national-level net inflows of migrants’ remittances, foreign lending, and foreign direct investment.

Aside from global economic downturns, some scholars provide evidence indicating that remittances act as informal insurance in times of other covariate and idiosyncratic income shocks. Mohapatra, Joseph, and Ratha (Citation2012) and Amuedo-Dorantes and Pozo (Citation2006) demonstrate that households that rely on international remittances face fewer shocks from the shortage of food, drought and illness compared to other households who do not receive remittances.

Yang and Choi (Citation2007) provide evidence showing that about 60% of declines in household income are replaced by remittance inflows from overseas in the Philippines. Jack and Suri (Citation2014) find that, in Kenya, shocks reduce per capita consumption of households by 7% for non-users of mobile money but the consumption of households with access to mobile money is not affected due to increase in remittances received.

Consumption and shocks

Many scholars examine the effect of expected and temporary income variations on consumption and demonstrate that income shocks may affect consumption depending on the magnitude of the shock (Agarwal, Chunlin, & Souleles, Citation2007; Hsieh, Citation2003; Irac & Minoiu, Citation2007; Parker, Souleles, Johnson, & McClelland, Citation2013; Souleles, Citation2002; Stephens, Citation2008a; Stephens & Unayama, Citation2011).

Dercon et al. (Citation2005) look at the direct impact of income shocks on per capita consumption expenditure of households in 15 Ethiopian villages and find that experiencing a drought at least once in the previous five year decreases per capita consumption by about 20% and experiencing an illness decreases per capita consumption by almost 9%.

Using a panel data of households in rural Ethiopia, Dercon and Krishnan (Citation2000) present a contradictory result. They posit that food and non-food consumption expenditures are not influenced by farm-related mishaps such as disease in plants and animals, pest infestation and crop shortages.

Porter (Citation2012) provides evidence indicating that households are unable to safeguard themselves from rainfall failure that takes place on average every five years in rural Ethiopia. Alderman and Paxson (Citation1992) outline the possible reasons why households cannot fully insure consumption against income changes as moral hazard issue, information asymmetries and scarcity of insurance companies in developing countries.

Data and empirical methodology

The primary data for this study come from waves 3 to 7 of the Ghana Living Standard Surveys (GLSS), a nationally representative survey carried out by Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) with sponsorship from the World Bank. Wave 3 was carried out in 1991/1992 to cover the whole country with a sample of 4,552 households. Wave 4 was administered in 1998/1999 to cover the whole country and had a sample of 6,000 households. Wave 5 was carried out in 2005/2006 to cover the whole country with a sample size of 8,687 households. Wave 6 was carried out in 2012/2013 with a sample of 16,195 households and Wave 7 was carried out in 2016/2017 with a sample of 14,009 households. The outcomes of the surveys of 1991/1992, 1998/1999, 2005/2006, 2012/2013 and 2016/17 were published by the Ghana Statistical Service in March 1995 (GSS, Citation1995), October 2000 (GSS, Citation2000), September 2008 (GSS, Citation2008), August 2014 (GSS, Citation2014) and June 2019 (GSS, Citation2019), respectively.Footnote1 The paper builds on Akobeng (Citation2017) by extending the data period and including analysis on remittances and consumption expenditure.

The repeated cross-section data has advantages of less attrition and non-response, larger sample, and longtime of the survey interval. As commended by Deaton (Citation1997), it helps in attaining improved estimates and statistical power. However, the use of panel data that follow the same households over the years would have been more prudent in minimizing possible problems associated with unobserved heterogeneity of households. Unfortunately, the individual-level panel data is not available in Ghana for this study.

The surveys have sample households of 49,443. The sample households receiving remittances are 20,502 (41%) and those not receiving remittances are 28,941 (59%). Out of those receiving remittances, 16,546 (81%) receive internal remittances from Ghana and 3152 (15%) receive international remittances from Africa or other countries. The sample households receiving both internal and international remittances are 804 (4%). Thus, most migrants in Ghana engage in internal migration by moving from urban to rural areas. Even though more households receive internal than international remittances, the latter is more than the former, due to the huge amount of international remittances flow from countries outside of Africa like America and Europe.

is a t-test of the mean difference between recipients and non-recipients of remittances on sex of the head of household, age of the head of household, household size, total income, agricultural income, self-employment, rental income, other income, remittance income and total expenditures. The mean income and consumption expenditure of those receiving remittances are more than the non-recipients. We can infer from the table that income and expenditure are strongly correlated with remittances, as expected. The table shows that remittances tend to go to the older and female heads.

Table 2. Household summary statistics.

provides the regional mean summary of income. The regional summary shows that Greater Accra region, which contains the capital city (Accra), has the highest mean total income but the lowest agricultural income. This is expected because agriculture in Ghana is principally a rural phenomenon (MOFA, Citation2013). The Greater Accra region received the second-highest level of remittances, after the Ashanti region. Ashanti region has an archetypical matrilineal culture. One’s relationship with members of the extended family may be as important as, and in some cases more important than, one’s relationship with one’s spouses and children (Kutsoati & Morck, Citation2014).

Table 3. Regional summary of income.

The rainfall data, used as the instrument for the household agricultural income, were obtained from the Ghana Meteorological Agency. We were provided with daily rainfall data from 50 weather stations (as in Table 7 or Appendix 1) across Ghana over the period 1990 to 2017. Using this data, we calculate monthly averages and variance by region. Seasonal total rainfall for each rainfall station in each year is obtained by adding monthly rainfall for the months in each weather season (wet and dry season). The dry months in Ghana are August, December, January, February, and March whilst the wet months are April, May, June, July, September, October, and November. The excluded instrument for agricultural income is the average rainfall for an individual i in region j one year prior to the survey month. Each region has five rainfall stations. Households are assigned the rainfall data of the rainfall station geographically located in their region.

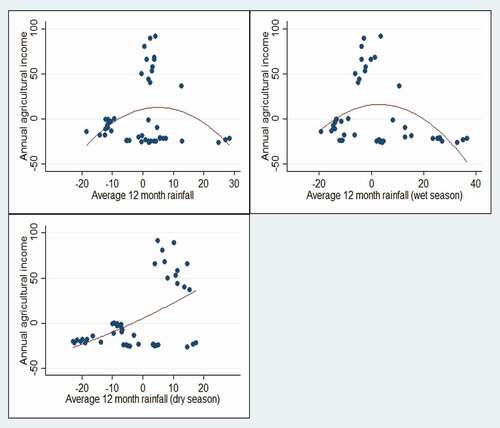

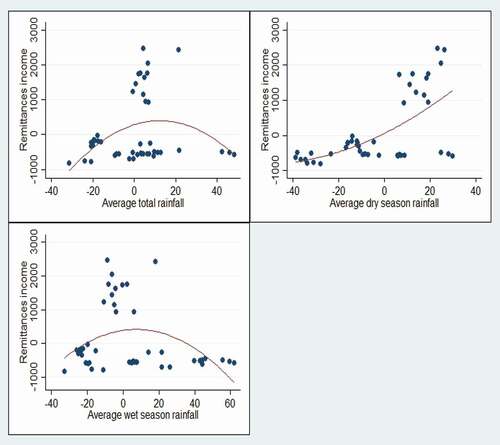

demonstrates the relationship between annual agricultural income and total rainfall. The figure shows that there is a quadratic relationship between total rainfall and annual agricultural income. The relationship between dry season rainfall and annual agricultural income is positive. This is expected because Ghana lies in the arena of the semi-arid tropical zone and is predisposed to drought, as such any increase in rain in the dry season imposes positive shock and thereby increases agricultural income. As the wet season rainfall is high, any further increase in wet season rainfall imposes negative shock leading to a decline in agricultural income.

Figure 3. Rainfall vs. agricultural income. Source: Author, using Ghana Meteorological Agency (rainfall data) and Ghana Living Standard Surveys of 1991/1992, 1998/1999, 2005/2006, 2012/2013 and 2016/2017. The points reflect average agricultural income and rainfall aggregated by region, reported in deviations from the regional mean.

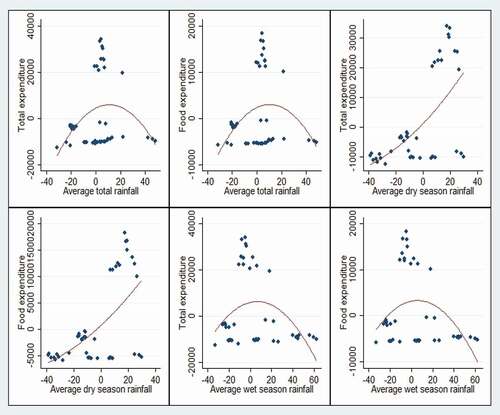

depicts the relationship between rainfall and total consumption and food expenditures. There is quadratic relationship between total rainfall, wet season rainfall and consumption expenditures. The dry season rainfall exhibits a positive relationship with consumption expenditures. Thus, a decline in dry season rainfall imposes negative shock on total consumption and food expenditures.

Figure 4. Rainfall vs. consumption expenditures. Source: Author, using Ghana Meteorological Agency (rainfall data) and Ghana Living Standard Surveys of 1991/1992, 1998/1999, 2005/2006, 2012/2013 and 2016/17. The points reflect average total consumption/food expenditures and rainfall aggregated by region, reported in deviations from the regional mean.

depicts the relationship between rainfall and remittances flow. Remittances increase with total and wet season rainfall until certain point where further increase in rainfall decreases remittances. In the dry season, remittances may increase to help households minimize the decline in agricultural income.

Figure 5. Rainfall vs. remittance income. Source: Author, using Ghana Meteorological Agency (rainfall data) and Ghana Living Standard Surveys of 1991/1992, 1998/1999, 2005/2006, 2012/2013 and 2016/2017. The points reflect average remittances income and rainfall aggregated by region, reported in deviations from the regional mean.

Empirical methodology

The study examines the relationship between agricultural income ( and household receipts of remittances (

. This relationship is identified with EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) . In this model we assume that the remittances-receiving household communicates its needs to the remitter, who responds by sending funds. Rainfall-driven income shocks may affect consumption expenditure of Ghanaian households. We analyze the effect of agricultural income on consumption expenditure (

with EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) .

The outcome, , is annual flow of remittance payments to household

living in region

in year

. The outcome,

, is consumption expenditure of household

living in region

in year

.

is the agricultural income earned by household

, and

is a vector of observable characteristics that influence remittance flows. The unobservable influences on remittance flows and consumption expenditure are specified in three parts: unobservable influences common to everyone in region

,

; unobservables over time that affect everyone in Ghana,

; unobservable characteristics of the individual that affect remittance flows and consumption in EquationEquations (1)

(1)

(1) and (Equation2

(2)

(2) ),

. EquationEquation (3)

(3)

(3) , the first-stage model, uses the rainfall instruments

to isolate the part of the variation in agricultural income that is uncorrelated with the error term. The isolated part of agricultural income

is used to estimate the effect of a change in agricultural income on remittances

from EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) and the effect of a change in agricultural income on consumption expenditure

from Equation (2).Footnote2

The first parameter of interest,, reflects the marginal impact of a unit increase in agricultural income on net remittance flows. The second parameter of interest,

, reflects the marginal impact of a unit increase in agricultural income on consumption spending. Using OLS to estimate these parameters in EquationEquations (1)

(1)

(1) and (Equation2

(2)

(2) ) requires that there are no unobservable influences on remittance flows and consumption expenditure that are also correlated with agricultural income.Footnote3 Based on observational data this is unlikely to be true. For example, this assumption is violated if households with more education or agricultural income may probably produce migrants and receive remittances.

Also, it is likely that heads of households characterized by risk aversion may be less expected to produce migrants and receive remittances. It is difficult to obtain data on these issues. Obviously, the OLS estimator will be biased if the omitted variable(s) is relevant and correlates with agricultural income or the other included regressors. This bias does not disappear in large samples, rendering OLS inconsistent.

Furthermore, similar factors like type of work or agricultural activity might determine both agricultural income and consumption expenditure such that the inclusion of agricultural income in the consumption model poses an endogeneity problem. We use an instrumental variable identification strategy to account for the potential endogeneity outlined above.

For Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) strategy to provide consistent estimates, we require that the excluded instruments, satisfy two conditions: 1) They must have a non-trivial correlation with agriculture income; 2) They must not be correlated with remittance payments and consumption expenditure other than through their effects on agricultural income.

We control for regional fixed effects that may affect remittance payments and consumption expenditures . It could be that different regions have different migration patterns, and these migration patterns are correlated with rainfall. For example, regions with a very high dry season may see high migration from households seeking more fertile grounds. These households then move instead of receiving remittance. If this is the case, then regional fixed effects should correct for migration.

The variables in include: 1) demographic, educational and occupational characteristics; 2) other income variables – including non-farm self-employed income, imputed rental income and other income sources.Footnote4 Remittance flows are also included in EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) . The demographic characteristics are sex of head of household, age of head of household and household size. The occupational characteristics are public employment, private formal employment, self-agro export, self-business, and non-working. The educational characteristics are no education, primary, junior secondary, senior secondary, middle school, teacher training, vocational school, ordinary level, advanced level, bachelor, masters and doctorate.

Estimation results with OLS and 2SLS-IV

In we present the resulting estimates of EquationEquations (1)(1)

(1) . The first column of the table presents the OLS regression results, whilst the second and third columns present results for two specifications of the instrumental variable regressions. In the first specification (IV(1)), we use as an excluded instrument the quadratic of average monthly rainfall for the entire year. In the second specification (IV(2)), we use as an excluded instrument the quadratic of average monthly rainfall for the wet and dry months separately. The IV(1) and IV(2) results suggest that there is a significant negative relationship between remittance payments and agricultural income. The IV(1) and IV(2) estimates suggest a 0.457 unit and 0.295 unit increase in remittance payments following a 1 unit decrease in agricultural income respectively. The implication from the IV(2) result is that a decrease in agricultural income of 100 Ghana Cedis (GH¢100) in times of negative income changes attracts remittance payments of about 30 Ghana Cedis (GH¢30), or a replacement rate of 30%. The OLS estimator puts the replacement rate at 0.7%. This suggests that the OLS estimator under-estimates the relationship between agricultural income and remittance payments. The analysis for only agricultural households in Appendix 2 (Table 8) reveals replacement rate of 32% and 0.8% for the IV and OLS estimates, respectively.

Table 4. Remittance payments regressed on agricultural income.

The findings are consistent with the self-interest motivation which is classified in the theoretical literature as ‘insurance model’ (Agarwal & Horowitz, Citation2002, p. 2033). The result is qualitatively in line with Yang and Choi (Citation2007). The result matches with other empirical findings that remittances in the receiving country provide a bolster for income declines for receiving households (Gubert, Citation2002; Yang, Citation2008a; Mohapatra et al., Citation2012; Amuedo-Dorantes & Pozo, Citation2006).

The first-stage results in suggest an important relationship between agricultural income and rainfall which is 1% significant when the wet and dry seasons are evaluated separately. We take advantage of the quadratic effects of rainfall and agricultural income in the first-stage regression to further investigate the rainfall levels at which agricultural income decreases or increases in the dry and wet seasons.

Using Model (IV(2)), we can determine the optimum level of dry and wet-season rainfall by differentiating the agricultural income equationsFootnote5 for dry and wet seasons respectively and equating them to zero.Footnote6 The first-stage of model IV(2) suggests that in the dry season rainfall decreases agricultural income, until approximately 88 mm of rain, more than twice the average dry-season rainfall of 42 mm, after which we see an increase in agricultural income. In the wet season we see the opposite effect, rainfall increases agricultural income, until approximately 147 mm of rain, 16 mm more than the average wet-season rainfall of 131 mm, after which we see a decrease in agricultural income. The errors are clustered by running month and region (as this is the level of aggregation for the rainfall variable).

quantifies the relationship between total consumption, food expenditures and agricultural income for rural households in Ghana. It is found that a GH¢100 decline in agricultural income due to rainfall failure leads to GH¢60 decline in total consumption and GH¢36 decline in food consumption expenditure. Agricultural households recorded GH¢63 and GH¢39 decline in total and food consumption expenditure respectively (Table 9 of Appendix 2).

Table 5. Consumption expenditure regressed on agricultural income for rural households.

We further regressed consumption expenditure on agricultural income of very poor and poor households in the rural areas in . The standard of living for everyone in Ghana is measured as ‘the total consumption expenditure per equivalent adult, of the household to which he or she belongs, expressed in constant prices of Greater Accra in January 2013’ (GSS, Citation2014, p. 7). Based on this definition, two nutritionally-based poverty lines are derived for Ghana. These are a lower and an upper poverty line of GH¢792.05 (equivalent to about $1.10 per day) and GH¢1314.00 (equivalent to about $1.83 per day) per adult per year, respectively.

Table 6. Consumption expenditure regressed on agricultural income of very poor and poor households in rural areas.

A lower poverty line is what is needed to satisfy the nutritional requirements of household members. Individuals whose total expenditure falls below this line are said to be in extreme poverty or among the very poor group. The upper poverty line combines both essential food and non-food consumption. The individuals consuming above this level can buy sufficient food to satisfy their nutritional requirements and their basic non-food needs. The poor are individuals whose total expenditure falls below the upper poverty line but with expenditure level at the lower poverty line or above.

The results in show that a GH¢100 decline in agricultural income due to rainfall failure leads to GH¢52 decline in total consumption of very poor households in rural areas. For the poor household’s total consumption declines by GH¢36. Thus, very poor households may be less safeguarded against income risk.

Additionally, a GH¢100 decline in agricultural income due to rainfall failure leads to GH¢35 decline in food consumption of very poor households in rural areas. For the poor households, food consumption declines by GH¢34.

Model diagnosis

We test the validity of our instruments with the Hansen (Citation1982) J-test. The null hypothesis is that the instruments are valid. The Hansen tests indicate that P > 0.05. The P-value in models IV(1) and IV(2) are 0.937 and 0.152 respectively in . So, we fail to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that the over-identifying restriction is valid.

Weak identification test is conducted by computing the Kleibergen and Paap (Citation2006) rk Wald F-statistics and juxtaposing it with the Stock and Yogo (Citation2005) IV critical values. As a rule of thumb, a Kleibergen-Paap Wald rk F-statistic greater than 10 is required to reject the null hypothesis of weak identification (Baum, Citation2006). As shown in , the Kleibergen-Paap Wald rk F-statistics for the IV(1) and IV(2) models are 18.366 and 29.320, respectively. This testifies the strength of the instruments.

Whether the instrumental variable approach isolates the causal channel depends on two factors: the strength of the instrument, and the timing of remittance flows relative to agricultural income. The strength of the instrument is affirmed by the Kleibergen-Paap Wald rk F-statistics which is greater than 10. Unfortunately, the GLSS does not provide information to determine whether remittance flows are received before or after the realization of agricultural income or the rainfall shocks.

The relevance of the rainfall instruments is scaled by the correlation between rainfall and agricultural income in . Rainfall is likely to influence agricultural income but may not affect remittances and consumption after controlling for factors that are directly affected by rainfall such as other income sources, demographic, and occupational characteristics in the models.

Conclusion and policy implications

After instrumenting for the possible endogeneity of household agricultural income, and controlling for household characteristics, our results suggest that a fall in agricultural income in times of rainfall failure may increase remittance payments.

We also find that a decline in agricultural income due to rainfall failure reduces total consumption and food expenditure of rural households. The effect of the decline in total consumption expenditure on very poor households in rural areas is more than the effect on only poor ones.

In order to help households protect themselves from adverse rainfall-driven agricultural income changes, it is necessary that the government of Ghana put in place infrastructure and policies. These should include measures such as irrigation structures, storage facilities, crop diversification, subsidies, access to credits, and favorable land policies. In addition, legislation to reduce the transaction cost of remitting can help households benefit more from such inflows to smooth consumption expenditures.

As the poor rely substantially on crop income, an increase in crop income may reduce poverty. This implies that part of the remittance payments which replace the fall in agricultural income may help alleviate household’s vulnerability to poverty. Our findings point to the fact that remittance payments may play an essential role as an informal safety net, especially for people engaged in agriculture in rural areas of Ghana. The mobilization of diaspora organizations and individuals to channel remittances towards interventions that benefit the poor may be considered as one of the priority areas in the national development plan of Ghana.

This paper uses a method that generates exogenous variation in agricultural income to quantify the relationship among agricultural income, remittances, and consumption. It provides a first-hand empirical test of the insurance motivation of remittances in Ghana. A cross-sectional approach may suffer from the effects of unmeasured confounders. However, an instrumental variable approach enables causal estimates in observational studies to be obtained in the presence of unmeasured confounders. It minimizes possible influences on remittances, agricultural income, and consumption expenditure. Also, a cross-sectional approach may be subjected to responder, interviewer and social acceptability biases in agricultural income and remittances. The instrumental variable approach minimizes the possibility of measurement errors in agricultural income and remittances.

The Ghana Living Standard surveys do not provide adequate information to facilitate the determination of both observed and counterfactual agricultural income. The lack of experimental data on household agricultural income in Ghana prevented us from conducting a true experimental analysis of the impact of agricultural income on remittances and consumption. Due to the possible skewness of remittances and consumption expenditure, a generalized MLE approach may be appropriate for correcting for agricultural income. Rainfall may correlate with agricultural income in Ghana overall, however the overall correlation could be mostly driven by a strong correlation in rural areas and a weak one in urban areas.

An interesting question for future policy research may be whether a fall in agricultural income, because of a decrease in rainfall, causes a change in the diet of households without affecting nutrition. Future research may also look at whether diversifying agricultural activities or implementing climate change solutions that are oriented towards stabilizing variability in rainfall might be helpful in limiting household dependence on remittance.

Acknowledgement

I especially thank Lancaster University for providing the Gold Open Access funding. I am indebted to Dr. Jesse Matheson of the University of Sheffield, for his helpful ideas and suggestions. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Prof. Bartholomew Armah of United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, and Prof. Tadele Agaje of Addis Ababa University, for their feedback on the drafts of this manuscript. I am thankful to the conference participants of the University of Ghana Alumni Conference, and Ethiopian Economic Association seminar presentation. I thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor, Prof. Cheryl Doss, at the Oxford Development Studies for their constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eric Akobeng

Eric Akobeng is a Lecturer in Economics at Lancaster University (Ghana Campus). He holds an MSc in Economics from the University of Manchester (UK) and a PhD in Economics from the University of Leicester (UK). He worked with the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) as Chief of the Development Planning Section at the Macroeconomic and Governance Division in Ethiopia (Addis Ababa). Prior to that, he worked with Ghana Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning as Chief Budget Analyst, and with Ghana Local Government Service as Coordinating Director.

Notes

1 Remittances, income, and expenditure variables for the year 1991/1992, 1998/1999, 2005/2006

were converted from Cedis to Ghana Cedis before the analysis.

2 If agricultural income exhibits a non-normal distribution, the estimated values may be different from

the values estimated under the normality assumption. However, the instrumental variable approach

helps to minimize this challenge by using the predicted value of agricultural income which is uncorrelated

with the error term for the estimation. An obvious way may be through a controlled experiment.

Such experimental data is not available in Ghana.

3 That is, the following moment condition must be satisfied:

4 The other income sources include transfers and factor incomes from social security, pension receipts, educational scholarships, and dividends on investments, interest on savings and certain windfall gains.

5 The first-stage models for dry (D) and wet (W) seasons are and

.

6 These give the optimum level of dry- and wet-season rain as 0.876 mm and 1.472 mm respectively.

The rainfall values denote the effect of every 100 mm of rainfall on agricultural income,

so the optimum level of dry- and wet-season rainfall are 88 mm and 147 mm, respectively.

References

- Acosta, P., Calderon, C., Fajnzylber, P., & Lopez, H. (2006). Remittances and development in Latin America. The World Economy, 29(7), 957–987.

- Adams, R. H., & Cuecuecha, A. (2013). The impact of remittances on investment and poverty in Ghana. World Development, 50, 24–40.

- Agarwal, R., & Horowitz, A. W. (2002). Are international remittances altruism or insurance?Evidence from Guyana using multiple-migrant households. World Development, 30(11), 2033–2044.

- Agarwal, S., Chunlin, L., & Souleles, N. S. (2007). The reaction of consumer spending and debt to tax rebates - Evidence from consumer credit data. Journal of Political Economy, 115(6), 986–1019.

- Agarwal, S., & Qian, W. (2014). Consumption and debt response to unanticipated income shocks: evidence from a natural experiment in Singapore. The American Economic Review, 104(12), 4205–4230.

- Ajefu, J. B., & Ogebe, J. O. (2019). Migrant remittances and financial inclusion among households in Nigeria. Oxford Development Studies, 47(3), 319–335.

- Akobeng, E. (2017). Four Empirical Essays in Development Economics. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Leicester, United Kingdom.

- Akobeng, E. (2017a). The invisible hand of rain in spending: Effect of rainfall-driven agricultural income on per capita expenditure in Ghana. South African Journal of Economics, 85(1), 98–122.

- Akobeng, E. (2017b). Safety net for agriculture: Effect of idiosyncratic income shock on remittance payments. International Journal of Social Economics, 44(1), 2–20.

- Alderman, H., & Paxson, C. H. (1992). Do the poor insure? A synthesis of the literature on risk and consumption in developing countries. World Bank (Research Paper No. 164). World Bank.

- Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Pozo, S. (2006). Migration, remittances, and male and female employment patterns. The American Economic Review, 96(2), 222–226.

- Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Pozo, S. (2011). Remittances and income smoothing. The American Economic Review, 101(3), 582–587.

- Batista, C., & Umblijs, J. (2016). Do migrants send remittances as a way of self-insurance? Oxford Economic Papers, 68(1), 108–130.

- Baum, C. F. (2006). An introduction to modern econometrics using Stata. Stata Press. Texas, United States.

- BoG (2016). Annual Report 2015. Bank of Ghana: Accra.

- Clarke, G., & Wallsten, S. (2003). Do remittances act like insurance? Evidence from a natural disaster in Jamaica. SSRN Working Paper Series, January. The World Bank.

- Deaton, A. (1997). The analysis of household surveys: A microeconometric approach to development policy. Baltimore, United States: World Bank Publications.

- Dercon, S., & Krishnan, P. (2000). Vulnerability, seasonality and poverty in Ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies, 36(6), 25–53.

- Dercon, S., Hoddinott, J., & Woldehanna, T. (2005). Shocks and consumption in 15 Ethiopian villages, 1999–2004. Journal of African Economies, 14(4), 559–585.

- GSS (1995). Ghana living standard survey wave 3 (1991/92) Report. (Technical Report, March). Ghana Statistical Service. Accra.

- GSS (2000). Ghana living standard survey wave 4 (1998/99) Report. (Technical Report, October). Ghana Statistical Service. Accra.

- GSS (2008). Ghana living standard survey wave 5 (2005/06) Report. (Technical Report, September). Ghana Statistical Service. Accra.

- GSS. (2014). Ghana living standard survey wave 6 (2012/13) Report. (Technical Report, August 2014). Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

- GSS (2019). Ghana Living Standard Survey Wave 7 (2016/17) Report. (Technical Report, June 2019). Ghana Statistical Service. Accra.

- Gubert, F. (2002). Do migrants insure those who stay behind? Evidence from the Kayes Area (Western Mali). Oxford Development Studies, 30(3), 267–287.

- Gyimah-Brempong, K., & Asiedu, E. (2011). Remittances and Poverty in Ghana. Paper Presented at the 8th IZA Annual Migration Meeting. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). Washington D.C.

- Hansen, L. P. (1982). Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 50(4), 1029–1054.

- Harrower, S., & Hoddinott, J. (2005). Consumption smoothing in the Zone Lacustre, Mali. Journal of African Economies, 14(4), 489–519.

- Hsieh, C.-T. (2003). Do consumers react to anticipated income changes? Evidence from the Alaska permanent fund. The American Economic Review, 93(1), 397–405.

- Ilahi, N., & Jafarey, S. (1999). Guestworker migration, remittances and the extended family: Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Development Economics, 58(2), 485–512.

- IOM. (2017). International organisation of migration IOM, Republic of Ghana Main Report . Accra: IOM Ghana March 2017.

- Irac, D. M., & Minoiu, C. (2007). Risk insurance in a transition economy. Economics of Transition, 15(1), 153–173.

- Jack, W., & Suri, T. (2014). Risk sharing and transactions costs: Evidence from Kenya’s mobile money revolution. The American Economic Review, 104(1), 183–223.

- Jappelli, T., & Pistaferri, L. (2010). The consumption response to income changes. Annual Review of Economics, 2(1), 479–506.

- Kleibergen, F., & Paap, R. (2006). Generalized reduced rank tests using the singular value decomposition. Journal of Econometrics, 133(1), 97–126.

- Kutsoati, E., & Morck, R. (2014). Family ties, inheritance rights, and successful poverty alleviation:Evidence from Ghana . In Sebastian Edwards, Simon Johnson, and David N. Weil (eds.),African successes, volume II: Human capital (pp. 215–252). : Chicago, United States: University of Chicago Press.

- Lokshin, M., Bontch-Osmolovski, M., & Glinskaya, E. (2010). Work-related migration and poverty reduction in Nepal. Review of Development Economics, 14(2), 323–332.

- Lopez-Cordova, E., Tokman, A. R., & Verhoogen, E. A. (2005). Globalization, migration, and development: The role of Mexican migrant remittances/comments. Economia, 6, 217.

- Lucas, R. E., & Stark, O. (1985). Motivations to remit: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy, 93(5), 901–918.

- MOFA. (2013, August). Agriculture in Ghana. Facts and Figures (2012). Statistics, research and information directorate (SRID), Ghana ministry of food and agriculture (MOFA) (pp. 1–64). Accra : Statistics, Research and Information Directorate (SRID) of Ghana .

- Mohapatra, S., Joseph, G., & Ratha, D. (2012). Remittances and natural disasters: Ex-post response and contribution to ex-ante preparedness. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 14(3), 365–387.

- Parker, J. A., Souleles, N. S., Johnson, D. S., & McClelland, R. (2013). Consumer spending and the economic stimulus payments of 2008. The American Economic Review, 103(6), 2530–2553.

- Poirine, B. (2006). Remittances sent by a growing altruistic diaspora: How do they grow over time? Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 47(1), 93–108.

- Porter, C. (2012). Shocks, consumption and income diversification in rural Ethiopia. Journal of Development Studies, 48(9), 1209–1222.

- Quartey, P. (2006). The impact of migrant remittances on household welfare in Ghana. AERC Research Paper (No. 158). African Economic Research Consortium

- Souleles, N. S. (2002). Consumer response to the Reagan tax cuts. Journal of Public Economics, 85(1), 99–120.

- Stephens, M. (2008a). The Consumption Response to Predictable Changes in Discretionary Income: Evidence from the repayment of vehicle loans. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(2), 241–252.

- Stephens, M., & Unayama, T. (2011). The consumption response to seasonal income: Evidence from Japanese public pension benefits. American Economic Journal. Applied Economics, 3, 86–118.

- Stock, J. H., & Yogo, M. (2005). Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In J. Andrews & D. W. K. Stock (Eds.), Identification and inference for econometric models: Essays in honor of Thomas Rothenberg (pp. 1–54). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- WDI. (2016-2019). World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- World Bank. (2016). Migration and remittances factbook 2015. Washington DC: Author.

- World Bank (2017). Migration and development brief 28. October. Washington DC:Author

- World Bank. (2020). World bank predicts sharpest decline of remittances in recent history (Press Release NO: 2020/175/SPJ). Washington DC: Author.

- Yang, D., & Choi, H. (2007). Are remittances insurance? Evidence from rainfall shocks in the Philippines. The World Bank Economic Review, 21(2), 219–248.

- Yang, D. (2008). Coping with disaster: The impact of hurricanes on international financial flows, 1970-2002. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 8(1), 1–45.

- Yang, D. (2011). Migrant remittances. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3), 129–151.

Appendix 1

Table 7. Rainfall stations in Ghana.

Appendix 2

Table 8. Remittance payments regressed on agricultural income of agricultural households.

Table 9. Consumption expenditure regressed on agricultural income for rural households engaged in agricultural income.

Table 10. Consumption expenditure regressed on agricultural income of very poor and poor households in rural areas who are engaged in agriculture.