ABSTRACT

Little is known about what works to facilitate disability-inclusive employment. This study reports initial findings of a process evaluation of a disability-inclusive employment programme, STAR+, being implemented across Bangladesh. The study interrogates the design of STAR+ and the structures and processes by which it was delivered. Findings reveal an important role of early involvement of disability-focused organizations in intervention planning. The study further discusses adaptations made during STAR+ delivery. First, in some project areas, extra resources were available to appoint additional staff to support disability inclusion. Second, family members were relied upon by implementers to support youth with disabilities at their workplace and classroom training. Lastly, STAR+ implementers take care to ensure the right employers are selected by the programme, in some cases engaging in additional ad-hoc selection processes to on-board more altruistic individuals. Results are discussed in terms of programmatic and policy implications.

Introduction

Despite concerted efforts by the global community, access to decent work still remains elusive for many. Notably, persons with disabilities, who comprise approximately 16% of the world’s population (World Health Organization, Citation2022), are more likely to face barriers to employment and suffer poorer labor market outcomes, relative to the general population. For example, Mizunoya and Mitra (Citation2013) find people with disabilities have lower employment rates, compared to people without disabilities across 15 low- and middle-income countries (including Bangladesh). Achieving decent work and economic growth for all is a key target of the Sustainable Development Goals, the set of 17 objectives that provide a blueprint for achieving global peace and prosperity (United Nations, Citation2015). In particular, decent work is defined by the International Labor Organization (Citation1999) as productive work in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity. Decent work, in comparison to ‘work’ more broadly, focuses on opportunities for fairly paid jobs in safe working environments, where workers receive social protection, are treated equally and have the freedom to express concerns to employers (Rantanen et al., Citation2020).

The right to work comprises an essential facet of human dignity, and gainful employment underpins good physical health, mental wellbeing and economic security (United Nations, Citation2022). For persons with disabilities, this right is protected through Article 27 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Citation2008) which recognizes the right that persons with disabilities have to work on an equal basis with others. Moreover, work is an important pathway through which to offset the heightened risk of poverty people with disabilities experience (Banks et al., Citation2017). In addition to raising household income, work can improve the capacity to pay for disability-related goods and services necessary for promoting optimal functioning and participation – such as additional healthcare, personal assistance, assistive devices, or for accessible transport (Mitra et al., Citation2017). More broadly, inclusion of people with disabilities in the labour market also broadens national tax bases and represents opportunity to increase gross national domestic product (Banks & Polack, Citation2014). In an analysis of 10 low- and middle-income countries, the exclusion of people with disabilities from the labour market was estimated to have resulted in losses to GDP of 3–7% (Buckup, Citation2009). In Bangladesh, a 2008 assessment by the World Bank found the exclusion of people with disabilities from the labour market was responsible for a GDP loss of USD $891 million per year (World Bank, Citation2008). Workplace inclusion also fosters broader non-economic benefits. For example, modifications to ensure accessible workplaces benefit future employees with disabilities, including current employees who may later acquire a disability, as well as potentially other groups such as pregnant women.

Given that decent work is a human right and there are myriad individual and societal-level benefits associated with the participation of people with disabilities in the workforce, it is perhaps surprising that the evidence base on ‘what works’ to improve access to employment for persons with disabilities is relatively sparse. In a systematic review, Hunt et al. (Citation2022) identified a paucity of evidence concerning disability-inclusive livelihoods interventions, including a dearth of well-designed impact evaluations. Essential to evaluating the extent that real world interventions are effective at producing intended outcomes, like increases in employment participation and earnings, includes grasping why, when and how an intervention impacts – or fails to impact- target outcomes. Concerning disability-inclusive employment, Shaw et al. (Citation2022) have also noted the need for interventions to move beyond isolated strategies which target employers and employees to address the embedded structural and attitudinal barriers that are keeping people with disabilities out of work. This implies that interventions that have a chance at meaningfully and persistently addressing such an intractable challenge as the disability employment gap will tend to be complex by nature. Consequently, merely identifying whether there has been a change in desired outcomes that can be attributed to an intervention provides in isolation little insight to policymakers into the likelihood of similar results being produced again, across different contexts, and of the resources needed to do so. Hence, process evaluation of interventions are needed to provide insight into what has been referred to as the ‘black box’ of complex interventions (Hameed et al., Citation2022).

Employment and persons with disabilities in the Bangladesh context

Recent studies (Buettgen et al., Citation2015; Chowdhury et al., Citation2022; Thompson, Citation2020) highlight the significant economic challenges faced by persons with disabilities in Bangladesh, including exclusion from formal employment. A major driver of this exclusion is that youth with disabilities face difficulties in accessing education on the same basis as their peers, with many dropping out of school due to lack of specialized or accessible school infrastructure, for instance (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Citation2022). Moreover, vocational training centers often fail to provide accessible and suitable skills training for people with disabilities. This contributes to high rates of poverty for households with individuals with disabilities. Moreover, due to disability stigma, these households are more likely lose their social capital, networks and support circles when pushed into poverty, compared to others (Foley & Chowdhury, Citation2007). Women and girls with disabilities face particular challenges in terms of their livelihoods. Like many other South Asian countries, women with disabilities in Bangladesh experience limited opportunities for income-generating activities. The patriarchal structure in Bangladesh contributes to a situation where many women are confined to male-dominated rules, laws, and conventions, leading to their undervaluation, underpayment, and exploitation in the labor market. Women and girls with disabilities face additional disadvantage due to their impairment, often being expected to stay at home and being discouraged from participating in work outside their homes (Quinn et al., Citation2016).

Bangladesh is a signatory to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and passed the Rights and Protection of Persons with Disabilities Act (2013), which established work and employment for people with disabilities as a right in the context of national legislation. Despite this and the existence of a 10% quota of positions reserved for persons with disabilities in the public sector, actual representation remains disappointingly low. A key reason is the inadequacy of employment policies for individuals with disabilities in Bangladesh. For instance, inadequate provision of assistive devices and workplace modifications like ramps make it challenging for individuals with disabilities to work. However, there is no policy commitment to ensure these types of reasonable accommodations (Quinn et al., Citation2016). Moreover, there is no obligation to ensure guaranteed employment for a quota of persons with disabilities in the private sector. There is also widespread stigma toward persons with disabilities, including negative attitudes about their capability (Thompson, Citation2020. These factors underpin the low rate of employment for persons with disabilities across the country, affecting millions of people. A recent national survey by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (Citation2022) suggests that approximately 7% of Bangladesh’s 169 million people have some type of disability. Of these, two-thirds were found to be unemployed, rising to 87% of the women with disabilities. However, there is a lack of adequate knowledge regarding what works in the creation of employment opportunities for people with disabilities in Bangladesh (Šiška & Habib, Citation2013).

Present study

The present study is part of a broader process evaluation of the Skills Training and Resources + [STAR+] intervention, implemented across Bangladesh by the NGO BRAC. The primary objective of STAR+ is to enhance livelihoods and decent employment opportunities for youth with disabilities. The process evaluation is taking place alongside a cluster randomized control trial [cRCT] (see Banks, Das, et al., Citation2022) as part of a comprehensive impact evaluation of STAR+ carried out by the Programme for Evidence to Inform Disability Action [PENDA] project and funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office [FCDO]. STAR+ is taking place in 45 of BRAC’s 91 branch office catchment areas (geographical areas covering a radius of about eight km radius from the local BRAC office) across 39 of the 64 districts of Bangladesh. BRAC branch offices are located in urban or peri-urban areas of Bangladesh. Branch office catchment areas are clusters for the purposes of the STAR+ cRCT, with the 45 STAR+ delivering catchment areas comprising the intervention arm, and the remaining 46 the control, in which participants have access to only other usual programmes that BRAC offer (see Banks, Das, et al., Citation2022). To be eligible for STAR+ learners must have a disability, be aged between 14 and 35, have dropped out of school, and be living in poverty (a per capita household income of BDT 4000 (US$46) or less per month) without access to other employment or training. STAR+ was delivered alongside BRAC’s existing employment programme STAR. The trial endline is anticipated for Spring 2024.

Findings of the paper interrogate what was intended in the design of STAR+ and present an overview of the intervention process by investigating the structures and actors through which delivery was achieved. Moreover, findings identify key adaptations made to the intervention and theorise how these may conceivably influence or interact with subsequent intervention delivery and outcomes.

Specifically, the study had two research questions:

What were the processes, actors and resources used in STAR+ intervention design and delivery?

What were key adaptations were made to STAR+?

Method

The study is part of a broader process evaluation of STAR+, that uses the Medical Research Council framework (Moore et al., Citation2015) as its conceptual framework. This framework identifies four core focuses of process evaluations: i) How is delivery achieved? (e.g. structures and resources used to deliver the intervention); ii) What is actually delivered? (e.g. fidelity [the quality of what is delivered], dose [the quantity of what is delivered], reach [who the intervention reaches]); iii) How does the intervention work? (e.g. mechanisms of impact); and iv) context. The focus of this study is mainly on the first component, with findings from the other components to be discussed in future papers.

Specifically, findings draw on qualitative process evaluation data, collected after STAR+ implementation but before the impact evaluation endline. Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with a range of STAR+ implementers and beneficiaries, and key programme documentation was reviewed. Interview questions were designed to cover both the key concepts in the Medical Research Council framework (e.g. Moore et al., Citation2015), and each of the intervention’s components according to the project Theory of Change. Adopting the semi-structured approach supported the interviewers to capture necessary key information across the participant cohort, while having the flexibility to probe aspects which participants were particularly knowledgeable about or interesting information obtained during interviews.

Procedure

Qualitative research was carried out in three purposively selected clusters from the pool of 45 delivering the intervention. Selection aimed to maximize variation between research sites with respect to location and external job market conditions, but consideration was also given to ensuring the branch offices selected contained staff members that had been in post during the rollout of STAR+. Site selection was made with the assistance of BRAC. Utilizing these factors, Dorshona and Pirgacha from the Rangpur district in the northern part of Bangladesh, and Tala from the Satkhira district in the southern part of Bangladesh were chosen as sites. Pirgacha and Tala are peri-urban areas, while Dorshona is situated within a City Corporation, representing an urban area. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the institutional review boards at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (UK) and the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (Bangladesh).

As part of the initial stages of data collection, interviews were held with the senior management of the STAR+ programme. These explored the intervention’s design, the assumptions underpinning the intervention, and resources (e.g. staffing, programme structure) from the viewpoint of the senior management. Programme documents outlining planned aspects of the intervention were also collated and reviewed for this purpose. Next, in-depth interviews were conducted with STAR+ beneficiaries, programme staff and other intervention actors. For these interviews, the semi-structured interview guide was prepared in English and translated to Bangla. Interviews were conducted based on the participants’ availability throughout the day and were held in locations accessible and convenient to the participant. They were conducted in either the local Bangla dialect or standardized Bangla, depending on the participants’ preference. The average interview duration was 60 min. Interviews with marketplace community members were generally shorter at around 20–30 min as these focused primarily on a single aspect, sensitisation workshops.

Selection of STAR+ beneficiaries was purposive and designed to obtain a diverse range of viewpoints from youth with disabilities based on gender, impairment type and selected trade. Individuals connected to these youth (e.g. their employers during STAR+ apprenticeships) were also selected for interview where possible. Selection of programme staff to interview was done with the guidance of the implementation team.

Participants

A total of 61 interviews were conducted. Twelve were with the intervention recipients (youth with disabilities) and the remainder were with actors involved in STAR+ delivery (N = 49). This paper classifies these actors into three types: Implementers, who had responsibilities across multiple intervention components during the inception and delivery of STAR+, Trainers, who were recruited during inception for the delivery of specific STAR+ components and Marketplace Community Members, who did not have formal delivery responsibility but were exposed to behaviour change communication workshops through STAR+ and were expected by intervention designers to thereby create a more supportive environment for youth with disabilities as a result. Findings in the present study focus on the perspectives of the first two groups, Implementers & Trainers.

describes the main characteristics of these Implementer and Trainer respondents.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Analysis

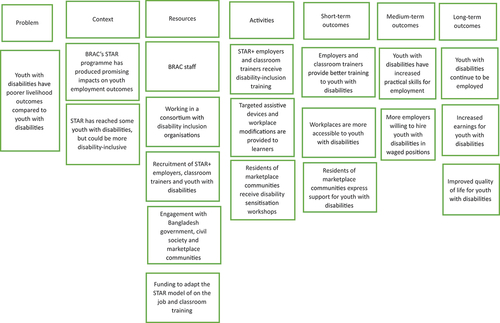

Interviews were transcribed to Bangla and then translated to English by professional translators. Interviews were imported to Nvivo 12 coded to identify discrete elements of the STAR+ intervention process, informed by the Medical Research Council guidance for conceptualizing interventions and process evaluations (Moore et al., Citation2015). Codes containing similar content were organized into superordinate themes. Once the data had been analyzed, a LOGIC model of STAR+ was developed (Moore et al., Citation2015). This used the STAR+ Theory of Change as a basis, which had been co-developed by the evaluation team and BRAC, and updated it based on the qualitative data and insights collected from STAR+ designers in the present study. The present paper draws on data collected from STAR+ Implementers and Trainers and forms part of a broader process evaluation of the programme.

Findings

An overview of STAR+ implementation is given below.

Overview of STAR+ implementation

Rollout of the STAR+ intervention entailed an inception phase of approximately three months (November 2021- January 2022) during which beneficiaries and key personnel are identified, a delivery period of six months (February 2022-July 2022) and a monitoring period of one month (August 2022) after conclusion of core delivery.

Selection and enrolment

To identify youth with disabilities the programme first gathered information from government and civil society sources, such as the Ministry of Social Welfare and local Organisations of Persons with Disabilities [OPDs], to better understand where youth with disabilities were located in a particular area. This was followed by a household survey with the youth and their caregivers to assess eligibility for the programme. Concurrently, MCPs are selected via a survey conducted within marketplace communities within STAR+ catchment areas. STAR+ personnel responsible for classroom delivery are recruited via a job advert and interview.

Trade matching, assistive device provision and workplace modifications

After programme enrolment, youth with disabilities received orientation on available trades within their local marketplaces. Eleven trades were offered through STAR+ in total (aluminum fabrication, beauty salon, dressmaking, electrical motor repair, IT support, mobile phone servicing, motorcycle servicing, refrigeration and air conditioning repair, tailoring, wood furniture, wood furniture design) although not all were available within individual market communities and the beauty salon trade was reserved for females. Trade matching took into account both the participant’s work preferences and implementer perception of their capability to work in the chosen trade, at the assigned workplace location (e.g. distance from the participants home). At this stage, youth with disabilities who needed them also received assistive devices from the programme. Devices like wheelchairs and crutches were given directly to beneficiaries by implementers, while youth requiring hearing aids and glasses were first assessed by a doctor. Assistive devices were paid for by the programme and support was also provided to help youth attend medical appointments. For example, BRAC staff would attend appointments with beneficiaries where relatives could not. Concurrently, when it was not possible to match learners to accessible workplaces, implementers introduced workplace modifications such as ramps and seating adjustments. In some marketplace committees, the programme also built accessible toilets.

Apprenticeships and classroom training

Apprenticeships with Master Crafts Persons lasted for six months, during which youth with disabilities worked five days a week. MCPs taught according to a Competency Skill Log Book provided by the STAR+ programme, which set out what youth with disabilities should learn about the chosen trade over the apprenticeship period. Each week learners also attended four hours of classroom training, comprising two hours of theoretical training in the chosen trade and two hours of soft skills training, for example covering behaviour and success in the workplace. Trainers teaching theoretical material also used the Competency Skill Log Book to plan and deliver session content. Theoretical classroom training was given to STAR+ learners alongside learners from STAR.

Sensitisation events

Community events took place targeting stigma and discrimination about the ability of people with disabilities to work, as well as wider common misconceptions about disability in Bangladeshi society (e.g. that it is a curse). These events adopted behaviour change communication strategies designed through formative research and targeted parents/caregivers and other family members of youth with disabilities, as well as the market communities more widely (i.e. market traders, including MCPs and co-workers, and other community people). Sensitisation events were delivered by BRAC staff alongside local OPD partners.

Job placement

At the conclusion of the six-month apprenticeships and the core delivery phase of STAR+, BRAC invited MCPs to offer learners waged roles. BRAC staff negotiated with MCPs to try to ensure youth with disabilities are given a fair salary and attempted to place learners not offered a waged role with another MCP or alternative marketplace employer. Monitoring of learners takes place for an additional month during this period.

How was STAR+ developed?

The STAR+ programme was developed by BRAC and partners through consultations with key stakeholders (OPDs, NGOs) between October 2018 and April 2019. The development and design of STAR+ was closely tied to BRACs existing experience with its employment programme for all youth, Skills Training for Advancing Resources (STAR). STAR has been active in Bangladesh since 2012, reaching over 60,452 youth, including 6,973 people with disabilities as of May 2021, comprising 11% of the total learners (Banks, Das, et al., Citation2022). STAR aimed to be inclusive from outset, taking an explicit focus on reaching women, non-binary individuals and youth with disabilities. Many components of STAR+ are activities that have been assessed by BRAC as effective in STAR for all learners (e.g. apprenticeships & classroom training).

The process evaluation found that the design of STAR+ was also informed by the perceived shortcomings of STAR with respect to reaching youth with disabilities. Implementers expressed concerns that the STAR programme was essentially a mainstream initiative, with only one component, assistive device provision, specifically targeted to youth with disabilities. As such, they conceived youth with disabilities to have equal access to the programme, but not equitable access, because they were not receiving additional support like workplace modifications. Moreover, they could not address this gap in STAR as resources were not available within the programme to provide youth with disabilities additional support, underpinning the need for a new initiative. Another noted issue was a gap in implementer expertise, for instance, in what constitutes a disability and how to provide accommodations. This experience informed the development of the impairment assessment in STAR+. As one implementer put it: ‘When we started developing [STAR+] with BRAC UK our major assumption was that yes we have failed in terms of identifying the PWDs’ (BRAC staff).

In the design phase, staff at BRAC were unsure of how to facilitate disability-inclusive employment and viewed STAR+ as an opportunity to acquire learnings which could be later integrated into STAR to support disability inclusion as well:

We lacked clarity and this project served as a valuable learning experience. We consistently discovered how to effectively incorporate persons with disabilities into the mainstream STAR program. Since I was asked about the assumption of the programme in the pre-designing phase, I would say that we were unaware of what we needed to learn, and this presented the ideal opportunity for us to learn it all.

In this respect, consortium working was perceived by BRAC staff as a key mechanism by which to acquire this knowledge. Although STAR was developed by BRAC, its adaptation to STAR+ has been funded by the Disability Inclusive Development programme [DID], through which BRAC formed new partnerships with several DID disability inclusion organisations, namely Action on Disability and Development [ADD], the Centre for Disability in Development [CDD] and Light for the World [LFTW]. An advantage of this collaboration was the opportunity for cross-learning. According to implementers, the expertise of the disability inclusion organisations helped make planned STAR+ activities more inclusive, for example, by supporting the development of disability-inclusive facilitation training through provision of technical assistance. Simultaneously, disability-focused organizations learned about skill development. At management level, LFTW also introduced the Disability Inclusion Score Card. which is a tool that helps organizations benchmark inclusion across six domains of organisational functions (e.g. Human Resources) and funded ten Disability Inclusion Facilitators [DIFs] to work within BRAC (see below). These initiatives were cited by BRAC as both informing the development of inclusive activities in STAR+ and changing BRAC staff members wider mindset and attitudes to disability.

Based on the findings, we constructed a logic model of STAR+, shown in , which highlights the processes behind implementation.

Intervention actors

The intervention involved numerous actors. outlines the roles of BRAC STAR+ implementers that are involved from the inception phase.

Table 2. STAR+ implementers and roles.

outlines the roles and processes involved in recruiting STAR+ trainers who are responsible for implementation of discrete intervention components in the delivery phase.

Table 3. STAR+ trainers, roles and selection process.

A final category of actors were marketplace community members. These individuals were the parents/caregivers of youth with disabilities, other family members, co-workers, market committee members, and miscellaneous community members that were recruited by STAR+ to attend sensitization workshops. No restrictions were placed on who could attend these meetings.

What adaptations were made to the delivery STAR+?

Findings identified three key adaptations made to STAR+ delivery. First was the appointment of ten Disability Inclusion Facilitators [DIFs] to work within ten branch office catchment areas that delivered STAR+. DIFs were a planned adaptation after the initial stages of STAR+ design, trained and introduced to the programme by consortium partner Light for the World through additional funding. In clusters where they were present, DIFs gave input into learner and trainer identification and monitoring, provided practical support to learners during apprenticeships and classroom training and assisted with the delivery of sensitisation workshops:

Their work involved visiting the shops where PWD learners were working, making regular visits, talking to their family members, having conversations with the MCP, and maintaining direct contact with the learners. And they have played an essential role in this behaviour change communication.

Each time I was in the training centre I had to help learners. For instance, suppose an intellectually disabled PWD is having a tough time understanding something, then I took help from the other non-PWDs to help that learner. With the help of others I managed to put them near the trainer. Those who could not write I arranged their seat in a way so that they may get help from other PWDs who could write.

As these excerpts highlight, DIFs were an additional point of communication between key stakeholders (youth, parents/caregivers, and MCPs) and assisted with the implementation of reasonable accommodations in classrooms. In non-DIF containing clusters, responsibility for this delivery fell wholly to BRAC staff, trainers and partner OPDs. As DIFs functioned as additional resources for the intervention to draw on during delivery it is plausible that youth with disabilities may have derived additional benefits from their involvement.

Second, the findings of this process evaluation identify the active involvement of parents/caregivers and family members, particularly of youth with communication impairments and difficulties travelling independently, as an important way in which implementers tried to ensure these beneficiaries received the intervention on the same basis as other learners. The primary role of parents/caregivers and family members in STAR+ intervention delivery was conceived as sensitization recipients as part of a wider effort to create positive attitudes to disability and shape an inclusive marketplace environment. However, in practice, implementers and consequently MCPs and classroom trainers relied on family members to provide practical support and assistance to communicate with these learners. Speaking about difficulties communicating with one of their apprentices, one MCP related:

I told [BRAC] that this learner actually cannot speak and often misunderstands. That means he cannot understand what I say and I cannot convey many things to him. What should I do with him? Then, [BRAC] connected me with the learner’s mother. When she came to my shop, I asked her, ‘What does your son do when he wants to go home or what does he think or say at that time?’ Then his mother showed me that when he wants to go home, he raises both hands up and points towards the house’s direction…For such problems, I also had his mother’s mobile number, so I would tell his mother what I want to express to him and she would tell me the gestures to make him understand.

Implementers also conveyed that they set expectations for parents/caregivers to attend both classroom training and workplaces to support youth with disabilities:

In addition, when we talked with their families, we encouraged the family members saying, you want to train the PWD but as she is a speech impaired person she cannot communicate properly through her voice. So, when she goes to work, you must go to the workshop sometimes so that the MCP can learn how to communicate with her.

The presence of family members was also viewed as necessary to help some learners, including those with some hearing, physical and speech impairments, to travel to and from workplaces and training institutions. When family members were unavailable to do this for example, because they were working, some trainers were given additional responsibilities by implementers to secure transportation for learners. Unavailability of family members to take learners to and from workplaces and training centres was also perceived as a source of learner absence and dropout and implementers suggested that these practical aspects of family member support may have been difficult to sustain through the six-month core delivery period. Taken together, these findings the need to examine the role of family member support in STAR+ in greater depth, including whether or not their involvement resulted in unanticipated consequences for some learners (e.g. dropouts).

Finally, the findings of the process evaluation suggest that the extent of ad-hoc adaptations made by implementers to the selection of Master Crafts Persons could play an important role in outcomes for youth with disabilities. District managers were the main decision-figure in MCP selection. One district manager interviewee viewed MCP selection as the most important aspect of the intervention delivery, as without the right MCPs motivated by social responsibility and not money, youth with disabilities would not be adequately trained as per the programme objectives. Speaking about MCP training, they (and other implementers) highlighted strategies that they would use to ensure that more altruistic motivations were nurtured among the MCPs, such as emphasising their social responsibility to youth with disabilities:

While selecting the MCPs I gave importance to how much they felt for disabled people and how much they were interested to hold a PWD as a brother or neighbour. If they had at least a little of this feeling, I nurtured them to magnify it. I made them understand that PWDs were also human beings like us and if we wanted to see them alive and healthy, we needed to build up and nurture skills inside them. Overall, the mentality of the MCPs was the most important thing to me.

In this excerpt, the implementer gives priority to the mentality held by MCPs in informing their selection decision-making. While the self-reported interest of MCPs in tutoring youth with disabilities was part of the formal STAR+ selection criteria, this implementer describes his conception of MCP mentality and the process of assessing it differently:

I used to talk and gossip with them and tried to get their intention to find out whether they were interested in training 2 PWDs for 3000 taka [27 USD] or they were doing that from their social responsibility … most of the people had a focus on the 3000 taka allowance though some of them had also a hidden intention to support people as a part of their social responsibility. (BRAC District Manager)

As this excerpt indicates, the monthly compensation offered to Master Crafts Persons during learner apprenticeships was an important resource. This compensation operated as an incentive for skilled MCPs to join the programme and remain engaged in tutoring youth with disabilities over the six months apprenticeship period and was higher compared to what they would receive through participation in other BRAC programmes, like STAR. Trying to draw out an MCPs true reason for participation is an example of an ad-hoc adaptation made to the STAR+ MCP selection process because, as this implementer later explained, they viewed the few days training given to the MCPs at the outset of the programme as insufficient to nurture altruistic motivations. The initial findings of this process evaluation suggest that the quality of MCP training and the extent of any ad-hoc modifications made by BRAC staff to select altruistic MCPs could prove important to the employment outcomes of youth with disabilities through two potential ways.

Firstly, MCPs involved in STAR+ primarily for monetary compensation may be less likely to pay learners fairly at the conclusion of apprenticeships. Specifically, at the end of STAR+ MCPs are asked to offer learners job placements. BRAC negotiates and attempts to secure a good salary for learners, but ultimately the decision to on-board youth with disabilities into waged placements and what to pay remains with the MCP. Where MCPs do not take youth with disabilities into waged placements, BRAC attempts to place them either at shops owned by other MCPs or with market traders otherwise unaffiliated with the programme. This process evaluation identified accounts of some MCPs offering waged placements to youth with disabilities, but subsequently underpaying them because of lack of demand for them compared to non-disabled workers. This creates a feedback loop in the marketplace, whereby other employers also seek to underpay them. One implementer spoke about a youth who was poached from a waged job placement by another trader:

Other shop owners wanted to take him because they would get more service with less investment. For example, if they took a healthy person, they needed to give him/her 300-500 taka [3-5 USD] where they could pay the PWDs 100 taka [1 USD] … I mean when another shop owner found that they were getting 80 taka in an MCP’s shop, they offered them 100 taka. With 100, they were getting an expert worker who was trustworthy too. (BRAC staff)

Second, for MCPs motivated by monetary compensation, the cyclical nature of the wider STAR programme, may act as an economic incentive for MCPs not to offer waged job placements to youth with disabilities at the end of the intervention. One BRAC staff respondent related:

Again there are other cases, where [MCPs] don’t want to keep the previous workers as they get two new learners free of charge. Why would I spend money when I can get the job done for free? ...Now I have told them, you will give a job to one, and give another one to your brother (laughing) so that your demand remains in the next year too. The market will be yours. (BRAC staff).

Although this implementer refers to learners carrying out work for free during STAR+, in actuality MCPs receive an additional incentive in the form of monthly monetary compensation. Thus, when MCPs are asked to adopt learners in waged placements, they are being asked to spend money on wages while concurrently losing a source of income. This account suggests that some MCPs prefer not to offer waged placements so they can wait to participate in the next STAR/STAR+ programme cycle and earn additional income. This excerpt also highlights an underlying mitigation strategy taken by BRAC staff during the job placement follow-up. Specifically, this implementer engages in economic negotiation with the MCP, explaining that they can retain their eligibility of the programme by giving at least one learner a job and helping to place the second with another market trader.Footnote2 The implication is that the MCP will then have a greater chance of being selected for the next programme cycle and gaining the corresponding supplementary income.

Discussion

Disability-inclusive employment interventions hold great promise for people with disabilities, their families and national economies. Yet, complex interventions are often a ‘black box’ (Hameed et al., Citation2022) leaving policymakers and implementers seeking to replicate a successful intervention or understand what happened behind an unsuccessful one with little to go on. This study releases initial findings of a process evaluation of the STAR+ intervention. First, it interrogates the assumptions implementers made in the design of the programme and the structures and actors used to adapt an existing livelihoods intervention, STAR, to be disability-inclusive. Second, the paper discusses key adaptations made to STAR+ delivery and theorises how these may influence or interact with outcomes.

The findings show that STAR+ was designed to provide youth with disabilities with a higher quality of livelihoods training through introducing disability-targeted initiatives (e.g. disability-inclusion training) and to address a perceived failure in the coverage of youth with disabilities within mainstream STAR. This is despite the fact that STAR has, at face value, reached a substantial proportion (at least 11% of total beneficiaries) of learners with disabilities (Banks, Das, et al., Citation2022). Moreover, working within a consortium with disability-focused organisations was highlighted as crucial by implementers in learning how to adapt STAR+ to be disability-inclusive. In particular, the actions taken by one partner, Light for the World, to embed disability-inclusion within BRAC itself through an organizational assessment tool and funding secondment positions for persons with disabilities in BRAC was highlighted as useful. The added value of this structure seems to be that implementers learn not just how to do disability inclusion, in the sense of providing a better intervention, but also how to be disability-inclusive in their own attitudes and practices. Similar conclusions have been reached by an assessment conducted by BRAC and its partners of the secondment model (Inclusive Futures, Citation2023).

Concerning adaptations to intervention delivery, firstly this process evaluation has identified that the appointment of Disability Inclusion Facilitators in some STAR+ clusters may have been beneficial to the intervention, as DIFs were useful additional resources for the intervention to draw upon. Second, STAR+ intervention delivery relied on practical support from family members, particularly of youth with communication impairments and difficulties travelling independently, in additional ways not fully anticipated by STAR+ designers. Notably, some family members were asked to take their children to and from workplaces and classroom trainings and in some cases to stay around to support communication between STAR+ trainers and learners. This strategy was vital to ensure these learners received the intervention, but implementers suggested the interest and ability of parents/caregivers to sustain this support through the six-month delivery period may have waned, raising the possibility affected learners could have been disadvantaged, relative to other youth. Lastly, the findings highlight that BRAC staff go to considerable lengths to ensure that the right MCPs are selected and stay motivated to serve the interests of learners in STAR+, in some cases engaged in ad-hoc selection procedures based on intuition about an MCPs personality and motivation for participating. Initial indications suggest that these efforts are important because the monthly compensation offered to MCPs to participate in STAR+ act as a considerable blanket incentive to participate. Further, the findings raise the possibility that financially motivated MCPs may be less likely to be on-board youth in waged placements at the conclusion of STAR+ and pay them fairly if doing so.

The contribution of these findings are three-fold. First, they add to theorizing of how STAR+ may have operated amidst the noise of real-world conditions and of how aspects of the programme (e.g. MCP participation incentives) may have interacted with the existing contextual dynamics of the Bangladesh marketplace. Second, they generate insights to be interrogated by future quantitative and qualitative data collection within the wider STAR+ cRCT evaluation, of which an endline is planned for Spring 2024. Third, they provide useful information to policymakers about resources and structures that proved beneficial to implementers in adapting an existing successful mainstream skill development programme (STAR) to be disability-inclusive (STAR+). Taken together, these findings comprise an initial glimpse into the black box of complex disability-inclusive employment interventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For most quotes, a broad description of the implementer category is given without their exact job title or geographical work location to preserve anonymity.

2 Bhai (brother) in Bangladesh is used widely as a term of address for another man.

References

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Report on national survey of persons with disabilities (NSPD).

- Banks, L. M., Das, N., Davey, C., Adiba, A., Ali, M. M., Shakespeare, T., Fleming, C., & Kuper, H. (2022). Impact of a disability-targeted livelihoods programme in Bangladesh: Study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial of STAR+. Trials, 23(1), 1022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-06987-2

- Banks, L. M., Kuper, H., Polack, S., & van Wouwe, J. P. (2017). Poverty and disability in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, 12(12), e0189996. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189996

- Banks, L. M., & Polack, S. (2014). The economic costs of exclusion and gains of inclusion of people with disabilities. International Centre for Evidence in Disability.

- Buckup, S. (2009). The price of exclusion: The economic consequences of excluding people with disabilities from the world of work. International Labor Organization.

- Buettgen, A., Gorman, R., Rioux, M., Das, K., Vinayan, S., Das, K., & Vinayan, S. (2015). Employment, poverty, disability and gender: A rights approach for women with disabilities in India, Nepal and Bangladesh. In Nazilla Khanlou, F. Beryl Pilkington (Eds), Women’s mental health: Resistance and resilience in community and society (pp. 3–18). Springer International Publishing.

- Chowdhury, S., Urme, S. A., Nyehn, B. A., Mark, H. R., Hassan, M. T., Rashid, S. F., Harris, N. B., & Dean, L. (2022). Pandemic portraits—An intersectional analysis of the experiences of people with disabilities and caregivers during COVID-19 in Bangladesh and Liberia. Social Sciences, 11(9), 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090378

- Foley, D., & Chowdhury, J. (2007). Poverty, social exclusion and the politics of disability: Care as a social good and the expenditure of social capital in Chuadanga, Bangladesh. Social Policy & Administration, 41(4), 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00559.x

- Hameed, S., Walsham, M., Banks, L. M., & Kuper, H. (2022). Process evaluation of the disability allowance programme in the Maldives. International Social Security Review, 75(1), 79–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/issr.12289

- Hunt, X., Saran, A., Banks, L. M., White, H., & Kuper, H. (2022). Effectiveness of interventions for improving livelihood outcomes for people with disabilities in low‐and middle‐income countries: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18(3), e1257.

- Inclusive Futures. (2023). Learning document: Towards inclusion of persons with disabilities within BRAC’s skills development programme.

- International Labor Organization. (1999). Decent work. Report of the Director-General to the 87th Session of the International Labour Conference, Geneva.

- Mitra, S., Palmer, M., Kim, H., Mont, D., & Groce, N. (2017). Extra costs of living with a disability: A review and agenda for research. Disability and Health Journal, 10(4), 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.04.007

- Mizunoya, S., & Mitra, S. (2013). Is there a disability gap in employment rates in developing countries? World Development, 42, 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.037

- Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., Moore, L., O’Cathain, A., Tinati, T., Wight, D., & Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical research council guidance. BMJ, 350(6), h1258–h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258

- Quinn, M. E., Hunter, C. L., Ray, S., Rimon, M. M. Q., Sen, K., & Cumming, R. (2016). The double burden: Barriers and facilitators to socioeconomic inclusion for women with disability in Bangladesh. Disability, CBR & Inclusive Development, 27(2), 128–149. https://doi.org/10.5463/dcid.v27i2.474

- Rantanen, J., Muchiri, F., & Lehtinen, S. (2020). Decent work, ILO’s response to the globalization of working life: Basic concepts and global implementation with special reference to occupational health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103351

- Shaw, J., Wickenden, M., Thompson, S., & Mader, P. (2022). Achieving disability inclusive employment–Are the current approaches deep enough? Journal of International Development, 34(5), 942–963. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3692

- Šiška, J., & Habib, A. (2013). Attitudes towards disability and inclusion in Bangladesh: From theory to practice. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(4), 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.651820

- Thompson, S. (2020). Bangladesh situational analysis. Inclusion Works.

- United Nations. (2008). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. UN Doc. A/RES/70/1.

- United Nations. (2022). CRPD/C/GC/8: General comment No. 8 (2022) on the right of persons with disabilities to work and employment.

- World Bank. (2008). A Project appraisal document on a proposed credit in the amount of SDR 21.9 Million (US$35 Million equivalent) to the People’s Republic of Bangladesh for a disability and children-at-risk project.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities.