ABSTRACT

This article investigates, by means of computer-assisted qualitative and quantitative discourse analysis, how and when ideology was securitized in US presidential speech. It reveals how securitizing speech justifies methods and targets in the resistance of “dangerous ideologies” that are problematic for democracies. The analysis reveals that the entanglement of oppositional ideologies with security was articulated in the context of the War on Terror. While the original need to see ideologies as an existential threat was necessary to justify the exclusion of the ideologies of the Taliban and Saddam Hussein from the elections in Afghanistan and Iraq in 2004 and 2005 respectively, the securitization of ideologies then spread to issue areas beyond terror and to geographic contexts outside of these two countries, all the way to US domestic political competition. The need to avoid embarrassment in Iraq and Afghanistan may have thus affected US democracy.

Introduction

During the Cold War, communist totalitarianism was often described as an unconstrained system of thought control in which technology was used to spy upon ordinary citizens and their ideological commitment to socialism. Recently, intelligence organisations in the US and many other Western countries have been adopting practices that, during the Cold War, would have been considered more characteristic of communist totalitarian countries than of the open societies of the West. This direction of travel in Western countries has been justified as inevitable and necessary given the election interference of – and fake news promoted by – autocratic countries such as China and Russia. The contradiction between thought control and the founding ideals of open societies requires us to consider whether the state control of ideologies was necessary and whether the things that we now see as necessitating such moves really were why an entanglement emerged between the discourse strands of ideology and security.

This paper answers the questions of how and when ideologies – understood as political preferences with the normative and ontological foundations of political visions – became matters of international security in US presidential discourse in the post-Cold War era. It shows how ideologies were securitised in a specific geographic and issue area context. The entanglement of the discourse strand of ideologies with that of security is a premise that can be theoretically shown as something that makes certain autocratic policies possible. This article does not, however, go beyond an empirical analysis of how the “security character of the problem of terrorist ideologies” is established. It does not empirically show how the social commitments resulting from the collective acceptance that the ideologies of terrorists are a threat are fixed, nor how the possibility of ideology-controlling mass surveillance and other autocratic policies are created (these three phases of securitisation are identified in Balzacq, Léonard, and Ruzicka Citation2016, 494). In other words, the empirical investigation in this article is limited to the securitising moves made by US presidents (mainly G.W. Bush). What this article does show theoretically is how the securitisation of ideologies is an autocratic discursive premise of politics that can be observed after the securitising moves have been made. It refers to cases in US domestic policies where the premise justified autocratic practices, even though it is not my intention to claim that the original emergence of this premise was causally dominant or that it was the only reason why such practices emerged in US politics.

I first define what is meant by:

Ideology, by using conceptualizations by Malcom B. Hamilton and Kathleen Knight (Hamilton Citation1987; Knight Citation2006);

Securitisation, by using ideas from the Copenhagen and Paris School of Security Studies (Balzacq, Léonard, and Ruzicka Citation2016; Wæver Citation1995), and

Democracy, by using ideas from Karl Popper’s theory of open societies (Popper Citation2012).

In this way, I am able to define what I study as the securitisation of ideologies and the resultant weakening of democracy. In addition to general ideas on democracy, I classify the targets and methods of the fight against dangerous ideologies; classifications which I then use to make sense of the extent to which the securitisation of ideologies constitutes a danger to democracy.

The process of the securitisation of ideologies does not tend to follow any generic rules that can be revealed through statistical analysis – neither is it caused by exogenous conditions. Instead, the process of the securitisation of ideologies is a singular history of discursive practices – articulations that create and are created, enabled, facilitated, limited and restrained by discourses (as in genealogical analysis by Doty Citation1996; and Foucault Citation1994). This historical process is unique and can only be explained by following the intentions of a given agent and the interplay of said individual with social and material structures. There are not many instances of a democratic country having to defend its honour and the legitimacy of its military operations by barring certain political parties from participating in elections. As a result, the creation of generic rules or a causal theory would not be possible.

To produce this evidence on the process of the securitisation of ideology, I analyse discursive developments from ideology to security and problems of democracy in US presidential papers by using computer-assisted qualitative and quantitative textual analysis. The data will be freely available online at https://doi.org/10.15125/BATH-01127 (Kivimäki Citation2022). With these tools, this article develops a heuristic theory of idiosyncratic historical development and the reasons behind it; one which seeks to explain by revealing and making sense of intentions and purposes, and by unveiling the interplay of purposeful speech acting, together with its structural enabling and limiting.

The main argument of this article is the following: to rescue the US from the embarrassment of Saddamist and Taliban victories in the first elections in Iraq (30 January 2005) and Afghanistan (9 October 2004), the ideologies of the two groups needed to be excluded from political competition. To justify this, these political preferences, ways of interpreting the world and normative inclinations had to be seen as security threats. However, rather than staying put in the Iraqi and Afghan contexts, the security framing of ideologies travelled beyond the context of terror and into Western domestic contexts, ultimately affecting both US and Western democracies.

The securitisation of knowledge and ideologies in existing literature

Articulations that securitise opposing ideologies build upon an existing consensus that has been created by previous articulations in US policies. In this section, I will first look at the research on the articulations upon which the securitisation that I am studying is built. I will then focus upon existing literature about the securitisation of ideologies and the gap in such literature that this article intends to fill.

The securitisation of ideologies in US presidential discourse was made possible by the cultures they were embedded within it (Holland Citation2013, 1). This type of securitisation was further facilitated by specific articulations that emerged before it and created a set of accepted interpretative and normative realities upon which the discourse that associated security with ideology relied.

There is existing literature on the development of the preference of militarised and power-centric approaches to problems in US foreign policy (see, for example, Bacevich Citation2005) as well as the “othering” of Iraq specifically. The propensity to react to problems with military means makes the securitisation of different issue areas, including ideologies, easier. Furthermore, the fact that issue areas related to Islam and Iraq have become easy to securitise in Anglo-American political speech (Croft Citation2012) has simplified the securitisation of ideologies in Iraq and Afghanistan.

While the securitisation of communist ideologies was part of McCarthyism during the Cold War, most McCarthyist normative and interpretative premises were generally rejected, hence they could not be used as building blocks in the articulations of the securitisation of Taliban and Saddamist ideologies. Yet the theme of the danger of the autocratic nature of both of these ideologies could be – and indeed was – utilised (Angstrom Citation2011).

Jackson and Holland show how the narrative of existential threat and the emergency of terrorism that both Republican and Democratic administrations adopted was built discursively. The US was at war with terrorists and thus some of the rules of peacetime did not apply (Jackson Citation2005b, 9). Yet, many other threats produced more fatalities and led to a greater extension of destruction than terror (Holland Citation2013; Jackson Citation2005a, 147, Citation2005b, 4). The War on Terror and the threat from terrorists were essential to the president’s ability to convince both domestic and international audiences of the need to do whatever it took, including the banning of specific ideologies in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Jackson and Homolar show how the identities of good Americans and demonised terrorists were built into US discursive strategies (Homolar Citation2011; Jackson Citation2005b, 2). This, too, was an essential prerequisite for the securitisation of ideologies: disallowing certain ideologies was not such a problem if at least some of their supporters could be demonised. The exceptionality and naturalised goodness of the American identity (Löfflmann Citation2015) also enabled anti-terrorist actions.

Finally, the discourse surrounding the events that took place on 11 September 2001, in which warnings from the intelligence community were not heeded by domestic law enforcement agencies, prepared the ground for a development that connected the partisan intelligence and conflict discourse strand with the domestic administration (Jackson Citation2005b, 15). This discursive entanglement between the external war/security strands with domestic governance prepared the path for the securitisation of ideologies in domestic political competition. Together with the idea of some countries being “rogue” (Homolar Citation2011; Tanter Citation2003), this discursive element lowered the threshold of interference in democratic domestic political competition while highlighting the importance of such interference for the external security of the US (Homolar Citation2011, 711).

There is plenty of literature that focuses upon US and non-US securitising speeches on ideologies that constitute restrictions to ideological competition and lead to the deterioration of democracy (Cohen Citation2017; Yilmaz, Shipoli, and Demir Citation2021). The general association between the securitisation of ideologies and the decline of democracy does not, therefore, require further explanation. This type of securitisation is often seen in terms of the restrictions placed upon the “dangerous ideologies” of political opponents (Malinova Citation2014; Yilmaz, Shipoli, and Demir Citation2021).

In addition to the literature concerned with the implications for democracy of the securitisation of ideologies, there are theories that focus upon the concept of populism as a political ideology that opposes certain democratic procedures. Rather than seeing the securitisation of ideologies as a danger to democracy, this literature focuses upon democratic procedures and calls for the marginalisation of populist ideologies – it suggests that limitations be placed upon “populist popular sovereignty” on account of the danger that it poses to democratic procedures (such as free media, equality in political debate and the principles of non-violent political competition) (Chivvis Citation2017).

Much of the literature on the ideological warfare of the US frames the Western securitisation of ideologies as a response to Russian and/or Chinese ideological offensives. This literature often uses the concept of hybrid or information warfare as a discursive instrument to associate the military threat of Russia with the country’s ideological propaganda challenge (Keating and Schmitt Citation2021; Snegovaya Citation2015, 21). The role of social media as the source of an increasing share of the information behind the beliefs and values that people hold has been seen as another reason why the West should rightly consider certain information and ideologies to be dangerous (Chivvis Citation2017). As such, this literature contributes to the broadening of the Western securitisation of ideologies.

However, evidence-based analysis of the origins of securitised oppositional ideologies is missing. The narrative behind securitised ideologies is recreated to justify such securitisation, which is problematic since it makes autocratic policies possible in the first place. Therefore, this article complements existing literature by showing how and in what contexts securitising moves were made. The securitisation of ideology is not a reaction to the increasing aggressiveness of the Russians or the Chinese in cyberspace, nor is it a necessary adjustment to the flow of propaganda in social media. An investigation of US presidential papers in this article reveals that, at the time when ideologies were being securitised, Russia was not presented as a danger to US security.Footnote1 This article will present evidence as to how the securitisation of ideologies started – it will show that securitisation was not a logical, nor indeed a necessary, conclusion or solution to existing threats. In this way, this article opens up the question of whether the securitisation of ideologies could be viewed more critically and if ideologies themselves could be de-securitised.

Conceptual and theoretical framework

This investigation of the origins of the securitisation of ideologies is based upon constructivist premises in which social reality is seen to be at least partly constituted by collective interpretations (Wendt Citation1998), which are themselves often sedimented in political language. It is therefore useful to investigate the development of social realities by focusing upon political language and texts. This focus reveals the knowledge and interpretations that sustain social realities and support, justify, and make possible certain practices; for example, treating certain ideologies as security threats.

The study of language and discourse reveals the interaction between the active articulation of meaning in political language (Burke Citation1966; Charon Citation1979) and the limits that language sets upon this and political agency (Blumer Citation1969). There are a number of approaches to narratives (Homolar and Rodríguez-Merino Citation2019; Patterson and Monroe Citation1998), rhetoric (Al-Sumait, Lingle, and Domke Citation2009; Jackson Citation2005a), discourses (Holland Citation2013; Wodak Citation2001) and stories (Smith Citation2003) that help one to understand the intellectual premises behind social practices and the strategies for changing such premises.

One of the ways of investigating social realities by focusing upon language is to see how different things are associated and dissociated in words and political language (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca Citation1968). This approach makes sense for an analysis that focuses upon how two discursive strands – those of security and ideologies – became entangled with political effects. Consequently, in this analysis, social structure is formed by the association and dissociation of things.

Finally, the focus of this article is upon the genesis of the meaning-giving that has led us to where we are now. The intention is to return us to the moment in which social reality was changed, either consciously or as a side-product of dealing with something else. In this way, we are able to broaden our range of options by becoming conscious of the conditions and alternatives that we had at the time when we started making dangerous ideologies a reality (Doty Citation1996; Foucault Citation1994).

The association and dissociation upon which this article focuses is that between ideologies and security – it has been argued that this association takes place in the securitising utterances made by authorities (Balzacq, Léonard, and Ruzicka Citation2016; Wæver Citation1995), which are specific types of speech acts (Searle Citation1976). The securitising association between a discourse strand and security is not just an argumentative, rhetorical strategy; it is also an act with the capacity to disrupt the normal rules, practices and politics regarding an issue area, such as a specific ideology (Phillips Citation2007). The focus of this paper is upon the securitising utterances that moved oppositional ideologies into the realm of security – this will be done in a way that reveals the aspects of the entanglement of security and oppositional ideologies that affect democracy. As such, this study is at the core of the research agenda of the securitisation theory (Wæver Citation1999, 334).

While speech acts create social realities by moving issue areas into the realm of security, existing discourses also limit and facilitate opportunities for securitising speech. The talk of information warfare, for example, is only possible once ideologies have been associated with security in political language – only if there are dangerous ideologies can it be claimed that the information that feeds them is also a matter of security. When an ideology is considered to pose an existential threat to the state, the state, it is said, must act decisively – it cannot afford normal, transparent procedures, and the role of the security apparatus in saving the state from this threat must be emphasised (Laustsen and Wæver Citation2000, 708). However, this can be problematic for the principle of popular sovereignty, as outlined below.

Different theories of securitisation vary in the emphasis that they place upon the role of the audience in the securitisation act. In general, the Copenhagen School has focused more upon the speech act (Wæver Citation1995), whereas the Paris School has expanded the concept towards a view in which the audience has an active role in securitisation (Balzacq, Léonard, and Ruzicka Citation2016). There may, for example, be contradictions between US foreign policy documents aimed at audiences focused on human rights and those focused on counter-terrorism (Kurtz and Jaganathan Citation2016), which may also be of importance for this study. While this article solely focuses upon speech acts, it does consider the audiences as something that securitising utterances have to consider. Most of the presidential articulations of the entanglement of security and ideologies were first presented to domestic audiences. It was difficult for President Bush to keep his messages to his own voters and those to his allies in Muslim countries coherent and uncontradictory. By and large, however, presidential speech on ideology specifically is rather coherent.

The concept of ideologies in this article is based upon common elements of political science definitions in contemporary scholarship that view an ideology as a more or less coherent – and relatively stable – explanatory set of beliefs and/or values held by certain groups of people in relation to society (Ackerman and Burnham Citation2021; Hamilton Citation1987, 20; Knight Citation2006, 625). The discussion on ideologies in this article is centred around those related to choices about political futures: what, in other words, people would like society and state to look like. The focus is not, therefore, upon the methods by which these political futures could be attained. The ideological elements under consideration in this article are those that democratic political competition deals with – methods of competition (for example, whether it is justifiable for visions of political futures to be promoted by violent means) will not be discussed as ideology.

There is no objective or scientific way of verifying a “correct” ideology consisting of the “right” sort of beliefs, values, and preferences. According to Popper, in an open society and democratic political system, people should be free to formulate their own individual and collective political preferences, values and ideologies – popular ideologies should then be reflected in the decisions of the state (Popper Citation2012, 510). These two conditions will be referred to as the popular sovereignty principle in this article.

In a democracy, the security apparatus is assumed to control, deter, and prevent illegal actions and methods of political and economic competition, and it is assumed that this control excludes the realm of ideologies and political preferences: thought crimes are associated with autocratic security governance. It is necessary to formulate a distinction between ideologies that the state should not control and methods of achieving ideological objectives that law enforcement officials should control. A state that controls the ideologies of society cannot be considered democratic, while a state that does not control methods of political competition is not an orderly democracy – without a social structure based upon the dissociation of ideas and methods, democracy is simply not possible.

Ideological control has a variety of targets depending upon the construction of the “ideology” behind the practice of securitisation. It is possible to distinguish three targets with very different implications for democracy:

Dangerous state targeting of beliefs and values: When President Bush declared that his forces intended to fight the values and beliefs of the Taliban, his approach represented this definition of targeting. It threatens the core of democracy as it turns the power relationship upside down.

State targeting of ideologies that reject the value of the necessary processes of democracy: When President Bush argued against the ideologies of Saddamists and the Taliban as dangerous to the continuation of the institution of elections, his reasoning represented this type of targeting. Although state control of such ideologies is problematic, their spread may also threaten democracy.

Necessary state targeting of ideological justification and the favouring of violent or illegal methods: This understanding of dangerous “ideologies” (which does not, in the conceptualisation laid forth by this article, constitute an ideology at all) does not challenge democracy since it does not constitute an effort by the state to manipulate popular beliefs or values related to a given political vision. This targeting is based upon a differentiation between values and methods, and the policing of the latter rather than the former. A problem arises when a violent group’s methods of political competition are confused with its ideology and the ideology itself is marginalised from political competition for this reason.

There are also different means of targeting dangerous ideologies. Even though securitisation in its original form implies an emphasis upon military means, dangerous ideologies and radicalisation have been tackled in many ways. The method of fighting dangerous ideologies also determines its effect upon democracy. At least three separate methods can be identified:

Military responses: The discourses of US Presidents on terrorist ideologies clearly prescribe militaristic responses to counter dangerous ideologies. In the words of President George W. Bush to his domestic audience: “There’s a mighty ideological struggle taking place. Remember, it is really – the better way to describe what’s happening [in Afghanistan] is, this is a war against an ideology which stands exactly opposite of what we believe” (Bush Citation2004f, 1262).

Appeasement: Some programmes dealing with “dangerous ideologies” are aimed at the reintegration of ideologically radicalised potential jihadists into the mainstream by means of socio-economic appeasement programmes: for example, employment, housing and counselling (Gilkes Citation2016). These manipulative programmes do, however, threaten the basic model of democracy whenever the target of the state is to change popular political ideologies.

Deliberation: States can also engage dangerous ideologies by means that are compatible with the principle of popular sovereignty by simply using examples, arguments and evidence that counter dangerous ideologies.

Methods and data

This paper uses a special kind of discourse historical and discourse genealogical analysis in order to understand social realities (Doty Citation1996; Foucault Citation1994; Wodak Citation2001). However, the method employed is different from most discourse analyses as it exclusively focuses upon discursive entanglements and insists upon their substantiation – what is more, it does not reject quantitative methods in doing so.

Since the securitisation of ideologies implies an association between ideological and security concepts, it requires at least some degree of temporaneous correlative associations between words that belong to the discursive strand of existential threat and that of ideology. In order to define the context of the association of the language of security and ideology, it is necessary to look at the sentences and speeches in which such association takes place. It is also important to investigate how frequently security and ideological strands become entangled in the context of debates on energy resources, military alliances, terrorism, or other threats, and when discussing the problems of Europe, Africa, or another region or country. Finally, the intensity of securitising speech can be measured by the frequency of words in the ideological language. The main periods of the re-articulation of ideology as a matter of security are likely to be when ideological language and its associated words are most frequent. I have identified, in an analysis of the correlation of monthly frequencies of security and ideology words between 1989 and 2014,Footnote2 that the main period of development took place in 2004, especially in the latter half of the year. A more time-consuming textual analysis entailing the coding of text was then focused upon in the three years between 2003 and 2005.

In the more detailed textual analysis (of presidential utterances in 2003, 2004 and 2005), I have coded sentences with words stemming from “ideology” (413 sentences in total) in presidential papers by using NVivo 12 software. I identified those sentences in which ideology was presented as an existential threat and those where this was not done. I then coded these sentences based upon the method of resisting dangerous ideologies, coding each one for deliberative, appeasing, or military means (see the classification above). Finally, I coded these sentences for the target of their resistance of dangerous ideologies into three categories: resistance of ideologies as justifications of violent methods of political competition, resistance of ideologies as inherently anti-democratic and resistance of ideologies that were opposed for some other reason (see the classification of targets of ideological control, above). The exact coding rules can be found in the codebook of the data archive (https://doi.org/10.15125/BATH-01127). I then proceeded to create a variable describing the distance from elections, which I could subsequently analyze for its associations with the frequencies of monthly utterances of securitised ideologies, methods of resistance of such ideologies and the targets of this resistance.

In addition to quantitative analysis of the frequency of certain words, there is a need for qualitative discourse analysis to make sense of the processes of securitisation and identify the words that belong to “ideology speech” and “security speech”. The qualitative analysis of individual speeches and sentences reveals what kind of underlying discursive logic exists – citations are used to demonstrate how different things are associated with one another.

This study does not reveal causalities; rather, it reveals constitutive relationships. When Bush speaks of the ideology (political vision) of terrorism (method of political competition), a social reality is created in which ideologies and violent methods are entangled and ideologies can be treated as an existential threat (Laustsen and Wæver Citation2000). Since the state is responsible for the security of its citizens, this type of securitisation constitutes a social reality in which the state is expected to control certain ideological developments. Furthermore, as democracy is about the free competition of ideologies, such control constitutes (rather than causes) limitations to democracy.

The quantitative and qualitative analysis of the discourse has been conducted by studying US presidential papers produced since the end of the Cold War (Bush et al. Citation1989). The President of the US is the most authoritative person in Western security policies, and the US government collection of the Public Papers of US Presidents is the most comprehensive, consisting of practically every word that US Presidents have ever publicly spoken or written. Since public interpretations create social realities, public presidential documents are most useful for the study of the securitisation of ideologies.Footnote3 This collection of documents, consisting of more than forty million words, was studied using the NVivo 12 Pro computer package. The quantitative results of this textual analysis were then exported to the Stata IC 17 statistical analysis package – all correlation tests and quantitative data were created using this tool.

Both the textual analysis data and numerical resulting data are available online at the replication data depository (https://doi.org/10.15125/BATH-01127).

The genesis of securitised ideology

During the entire post-Cold War era there was already a weak but very significant correlative associationFootnote4 between the frequency of the words “threat”Footnote5 and “ideology” (0.2906, n = 300, p < 0.00005) and “threat” and “propaganda” (0.2087, n = 300, p = 0.0003). It would, therefore, seem that propaganda and ideology have always been somewhat entangled. However, if one disaggregates different time periods, it is evident that there is great variation in the strength of the correlative association between the terms of security discourse and those of ideology over time. There is a negligible association between 11 September 2001, and the end of 2003, and no association at all before September 2001. After 2003, however, the correlative association is already strong and statistically very significant between the frequencies of: “propaganda” and “terror” (0.5366, n = 120, p < 0.00005), “ideology” and “terror” (0.6121, n = 120, p < 0.00005), “threat” and “ideology” (0.4418, n = 120, p < 0.00005) and “threat” and “propaganda” (0.4076, n = 120, p < 0.00005). The argumentative association between security and ideology in presidential speeches rose sharply in 2004 before peaking in 2005. Therefore, in order to explore the genesis of the securitisation of ideologies, we need to focus most of the more detailed quantitative and qualitative investigation upon this period.

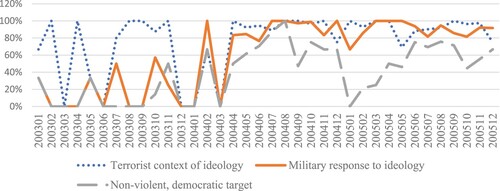

The emphasis placed upon ideologies, propaganda and other securitised discourse strands in information warfare started rising after the September 2011 terrorist attacks in the US, but the sharpest rise in prominence was not until 2004. By looking at US presidential papers, it is possible to see that, while some of the central qualities of the country’s narrative on Western values, freedom and liberty gained prominence after the terrorist attacks, the focus moved to ideology and propaganda only in 2004 (see Graph 1).

Graph 1. Monthly frequencies of utterances on “ideology” and “propaganda” in US presidential papers, 1989–2013.

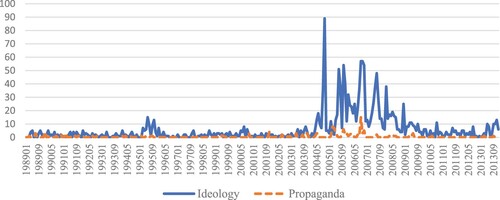

While the prominence of ideology as a discourse strand was temporary and started to wane after the elapse of various years, it managed to articulate some changes in the ways in which ideology could be spoken about. Graph 2 shows how there was a clear change in the way in which dangerous ideologies were associated with terror, and how it was stated that they could then be resisted and controlled militarily, rather than by simply deliberating about unacceptable ideas. What is less systematic but still clear is that, since the latter half of 2004, it has been possible to control and target, even militarily, ideologies that are not defined as violent or anti-democratic – whether they are supported by violent groups or groups that oppose the role of the US military or counterterrorism in the world seems to suffice. As defined above, (a) military means of control of (b) ideologies that were not as such irreconcilable with democracy and non-violence were the two aspects that proved to be most detrimental to open society and democracy. After the transition, it was possible for the President to justify the idea of treating the ideologies that Saddamists and terrorists supported as visions that could not compete non-violently in elections:

These enemies aren’t going to give up because of a successful election … They [terrorists and Saddamists] know that as democracy takes root in that country, their hateful ideology will suffer a devastating blow, and the Middle East will have a clear example of freedom and prosperity and hope. So, our coalition will continue to hunt down the terrorists and Saddamists. (Bush Citation2005h, 1842)

However, the association of danger with the ideologies of terrorists is not a given, nor is it natural. After all, it would be possible to fight for democratic ideologies and the rule of law by means of terror – a group that uses repulsive violent means can still support inherently good political visions.

From 2001 until the beginning of 2004, “terrorists” were taken to be people whose identity was defined by the methods that they used (terror) in the name of their political purpose/ideology. The focus of this perception of terrorism was upon civilian targeting (a method of political struggle). By 2003, terrorists were already affiliated in President Bush’s speech with supporters of Saddam Hussein,Footnote6 but the term “Saddamism” as an ideology was only introduced to a domestic audience in May 2004 (Bush Citation2004b).

The perception of terrorists simply as people with unacceptable methods of political competition started to change in February 2004 as Bush started to see civilian targeting as something that emanated from political objectives and ideologies – political visions had become dangerous and a target of militarised US struggle. This was new as, previously, official rhetoric invariably constructed terrorists as being motivated by “evil”, rather than by a specific ideology (Jackson Citation2016, 174). Furthermore, in Bush’s speeches, methods and objectives started becoming mixed together: “What has changed in the 21st century is that in the hands of terrorists, weapons of mass destruction would be a first resort, the preferred means to further their ideology of suicide and random murder” (Bush Citation2004d, 200). As a result of this mixing of methods and objectives, terrorist methods were not only seen as an existential threat – the political objectives common to terrorists also became fatally dangerous to the US.

In April 2004, Bush increasingly started to present terrorism and its violence as part of an ideology:

We’ve seen the same ideology of murder in the killing of 241 marines in Beirut, the first attack on the World Trade Center, in the destruction of two Embassies in Africa, in the attack on the U.S.S. Cole, and in the merciless horror inflicted upon thousands of innocent men and women and children on 11 September 2001. (Bush Citation2004h, 559)

In May 2004, Bush started to explicitly define counterterrorism as an ideological battle – terrorism could only be defeated by eradicating its underlying ideology: “In the long term, we must end terrorist violence at its source by undermining the terrorist ideology of hatred and fear” (Bush Citation2004g, 896). Lee shows how this made it harder for Bush to credibly convince people in Muslim countries that he was not against Islam itself, given that the ideology that Afghan and Iraqi terrorists claimed to fight for Islam (Lee Citation2017, 4–5).

In the same month, the battle against what Bush referred to as “terrorist ideology” received a further undertone of political power, especially when Bush was talking to domestic audiences: terrorist ideology, it was said, posed a threat to US global leadership.Footnote7 This weakened the ideological credibility of the War on Terror among US domestic and international Muslim populations, as well as in Muslim countries – old ideas of ideological battles as a smokescreen for “American imperialism” against non-Western, non-Christian cultures (Said Citation1997) were easy to mobilise as part of the resistance against US policies in the Middle East. Combining messages to domestic voters with those for international audiences during the 2004 presidential campaign was challenging – simplified “Jacksonian” ideas of cultural conflicts, religious themes and foundations of foreign policy rationales that appealed to domestic audiences were anything but useful for those in the Middle East (Spielvogel Citation2006). It was also in 2004 that the number of fatalities in wars in which the US was participating began to rise steeply.

Later, in June 2004, Bush introduced the idea of terrorists as “ideologues” who spread an ideology of violence that somehow automatically leads to bloodshed (Bush Citation2005d, 1317). Bush used the expression of terrorists as “ideologues” 62 times in 2004, 9 times in 2005, 5 times at the beginning of 2006, and then again more intensively in the lead up to the 2006 elections (25 times). This was done almost exclusively in front of domestic audiences. From 2004 it was stated that both terrorist methods and ideology must be resisted by military means. As a result, the drone assassination of Anwar Awlaki in 2011 was seen as justifiable, even though his connections with violent operations had not been discussed prior to his assassination – he was an “ideologue”, rather than an operator, yet he (and his 16-year-old son and 8-year-old daughter) needed to be killed.

At this point, Bush was still wedded to the idea of the struggle against terrorist ideology and the neoconservative belief that terrorist ideology was somehow related to autocracy (Schmidt and Williams Citation2008, 191–192) – in particular, the sort that Saddam Hussein represented. Defeating not just terrorist ideology but also authoritarianism was held to be necessary to end terror, and Bush used Iraq as the prime example of this: “The rise of a free and self-governing Iraq will deny terrorists a base of operation, discredit their narrow ideology, and give momentum to reformers across the region” (Bush Citation2004e, 920). Autocracy, so it went, caused terrorism.Footnote8 This invented causal linkage was consistent in Bush’s speeches to both domestic and international audiences.

This narrative of ideological warfare against Saddamism borrowed from Cold War discourses in which the forces of freedom were said to have been fighting against the forces of totalitarianism (Angstrom Citation2011). Bush introduced the concept of “ideologies of death” to link the War on Terror, the war on Nazism and the war on communism with the war on Saddamism (Bush Citation2004c, 943). This narrative portrayed death as an ideological objective of US enemies, rather than considering violence as a method in a conflict in which the US was participating. During the Cold War, militarised battle had primarily been against communist insurgents: violence was used to counter violence; deliberation and arguments were used in the ideological competition. This time around, ideological warfare involved denying the ideologies that terrorists supported of access to non-violence political competition, even if their supporters rejected violence.

The relationship between terror and Saddamism developed during 2004. In some of Bush’s later statements in 2004, supporters of Saddam Hussein were confused with terrorists – Saddamism as an ideology was, in and of itself, violent: “Iraqi people understand that America needs to be around for a while to help make sure that the killers – the foreign fighters who are there, disgruntled former Saddamists – don’t wreak havoc” (Bush Citation2004b, 796). The idea that supporters of Saddam’s ideology needed to be dealt with by using the security apparatus became, in 2004 and 2005, a natural fact, as if Saddamist ideology were somehow the same as that of terrorists.

After the first Iraqi elections in 2005, Bush introduced distinctions that partly undid the natural conceptual association between terrorism and Saddamism – he started emphasising terrorism and Saddamism as two distinct enemies, even though both were still associated with violence and continued to be forcefully resisted (Bush Citation2005f, 1783).Footnote9 Consequently, Saddamism still needed to be considered a security threat and kept out of the democratic competition of ideologies.

Elections, democracy, and the danger of ideology

Election victories of the supporters of the regimes that the US had removed from power would have painted the US policy of promoting democracy in a bad light. If avoiding embarrassment for the US and its policy of intervention was the main reason for the marginalisation and securitisation of the ideologies of the Taliban and Saddamists, it can be concluded that the introduction of ideologies as dangerous was motivated by a mere local situation.

Much of the change in the discourse strand on ideologies took place near to the first elections in Afghanistan and Iraq: the Afghan context’s share of ideology speech was strongly, and very significantly, correlated with the proximity of elections in Afghanistan (0.5840, p = 0.0002, n = 36), while the relationship between Iraqi share and the proximity of Iraqi elections was only moderate, yet statistically significant (0.3961, p = 0.0168, n = 36).Footnote10 Proximity to the Afghan elections is strongly and very significantly associated with the share of military means of ideological control as regards sentences on ideology (0.5977, p = 0.0001, n = 36) and the willingness to target ideologies that were not necessarily anti-democratic or violent (0.4287, p = 0.0091, n = 36). In the case of proximity to the Iraqi elections, associations that were considered to be the most dangerous for democracy are even more pronounced (military control: 0.6886, p < 0.00005, n = 36, resistance of non-violent, democratic ideologies: 0.4739, p = 0.0035, n = 36). In the case of proximity to the Iraqi elections, associations that were considered to be the most dangerous for democracy are even more pronounced (military control: 0.6936, p < 0.00005, n = 36, resistance of non-violent, democratic ideologies: 0.4733, p = 0.0036, n = 36). It is thus clearly apparent that the type of securitisation defined earlier as constituting the greatest danger to open society in the Popperian sense was related to the need to avoid electoral embarrassment in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Bush argued that elections were a deliberative strategy and an alternative to Taliban and Saddamist ideology, but he still did not allow the participation of these ideologies in non-violent political competition (Bush Citation2005e, 200). At least in the case of Afghanistan, such an option was explicitly on the table, as the Taliban pleaded with the US for permission to disarm and transition into an unarmed political party (Ackerman Citation2021, 1). This was resisted by the US security administration, most vigorously by the then US Defense Secretary, Donald Rumsfeld. Over 95% of those Bush's securitised utterances on ideology with a geographic context in the month of Afghanistan's elections were in the context of Afghanistan, and all securitised utterances on ideology in the month of Iraq’s election focused upon Iraqi ideologies. Since this was also when the securitisation of ideologies happened, and when references to ideologies as existential threats rose sharply, it seems likely that the very reason for the securitisation of ideologies was the need to find arguments to justify the exclusion of the Taliban and Saddamists from political competition.

It is unlikely that the securitisation and marginalisation of ideologies as a security threat was intended for US and Western political discourse: US ideologies did not yet constitute a security threat, and proximity to the first of the two aforementioned elections was negatively associated with the monthly share of such ideology speech that was related to Western ideological competition. Yet, once the logic of the exclusion and control of ideologies had been justified in US discourse on Iraq and Afghanistan, it became difficult to deny the opportunities that it gave to the domestic security administration. While securitised discourse on ideologies never took place in the context of US or allied security in 2003 or 2004, it happened 3 times during the first half of 2005 and 41 times during the second half. Securitised utterances on ideology were also expanded to issue areas outside terrorism in 2005. In 2003, there were only 3 utterances about dangerous ideologies or others than terrorists; in 2004 there were 13 and, in the first half of 2005 there were 11 – a figure that rose to 79 in the second half. In 2005, securitised utterances concerning ideology were mostly related to communist ideologies, and they were normally referred to together with – and in comparison to – the ideologies of terrorists.

The first time that Bush hinted at the need to control ideologies in the US was in the context of his effort to rally support for the renewal of the Patriot Act, which enabled domestic law enforcement officials to utilise security and intelligence bureaucracy sources. In June 2005, he suggested that: “[W]e’re facing terrorist organizations that know no border … They’ll kill innocent people like that in order to justify a hateful ideology … [W]e’ve got to do everything we can to protect the homeland, and we are” (Bush Citation2005b, 949). In September of the same year, Bush addressed the United Nations in support of a resolution that condemned the incitement of terrorist acts by stating that: “We have a solemn obligation to defend our citizens against terrorism … to promote an ideology of freedom and tolerance that will refute the dark vision of the terrorists” (Bush Citation2005c, 1434). The focus was upon the responsibility of the US to control dangerous ideologies domestically.

The National Security Agency (NSA) soon exploited this by using it as the rationale to justify the surveillance of ideological developments also among Americans. In 2005, the government’s domestic surveillance programme was revealed by the New York Times and the NSA’s massive, warrantless tapping of telephones and emails was exposed. By 2007, the threat from ideologies was also associated with the development of information technology (Bush Citation2007, 163). What had once been a justification for the exclusion of the Taliban from Afghan elections now legitimised the control of ideologies and communication domestically.

The context of securitisation has now broadened from the issue area of terrorism to that of foreign influence, and all this has changed the way in which ideologies, political preferences and information are dealt with: it has expanded the justification for state interference in the development of popular political thought, which has ultimately not been useful for the development of democracy as defined by Popper.

Conclusions

The theory developed in this article is based not upon causal claims but upon revelations about the interplay of agency, unintended consequences and social structures that affected US foreign policy in Iraq and Afghanistan. The securitising of ideologies in the context of these two countries could be seen as conscious conceptual gerrymandering – manipulating the borders of meanings of concepts to produce specific ends. At the same time, the fact that such securitisation expanded to domestic discourses was probably not something that Bush had in mind when he first securitised Taliban and Saddamist ideologies. The spreading of the securitised concept of ideology took place due to the logic of symmetry: if ideologies were a source of terror in Iraq and Afghanistan, it followed suit that they must also be a potential source of terror in the West. Furthermore, the material and institutional structure of the government empowered domestic security apparatuses to harness this discursive logic for their own benefit within domestic power hierarchies: if ideologies needed to be controlled for reasons of security, the security agency could easily justify new powers within the realm of ideological competition. Consequently, the path from avoiding embarrassment in Iraq and Afghanistan to the weakening of democracy in the US was not the result of a causal chain or a conscious masterplan; it was instead a process in which agency and structure interacted in a way that was neither controlled nor predetermined.

As outlined in the section on existing literature, the presidential articulations that entangled the discursive strand on security and ideology were made possible – or easier – by several discourses and material conditions upon which securitising speech on ideologies built. Thus, presidential articulations (mainly those in 2004) did not constitute the entire social structure of securitised ideologies: however, ideological issues became a central topic in US presidential discourse during the time of the first elections in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the association between discourse strands on ideology and security was made in the context of terrorism in these two countries. This inevitably suggests that there is an unintended linkage that has hitherto not been revealed – the need to avoid political embarrassment in Iraq and Afghanistan made it possible for the executive to change US democracy. This is what has been revealed in this article.

This article has explained how some of the limits that have been placed upon US democracy originated in the securitisation of ideologies in Iraq and Afghanistan. The roots of the entanglement of discursive strands of security and ideology have been shown empirically by revealing how ideologies became an issue just before elections in the two countries. Ideology-speech systematically securitised opponent ideologies, and it almost exclusively focused this entanglement on the country in which an election was about to be held. The security-speech on ideologies focused on those the US needed to exclude from the Iraqi and Afghan elections; an entanglement that the material effect of barring the Taliban and the Saddamists participating. This is the main empirical conclusion of this article.

While this article shows how a crucial premise of thought control emerged, a reflection upon how, and to what extent, it travelled from Iraq and Afghanistan to US domestic policies would require further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timo Kivimäki

Timo Kivimäki is Professor of International Relations, University of Bath (UK) and Senior Non-Resident Fellow of the Sejong Institute (South Korea). Professor Kivimäki joined the University of Bath in January 2015. Previously he has held professorships at the University of Helsinki, University of Lapland, and at the University of Copenhagen. Professor Kivimäki has also been director of the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (Copenhagen) and the Institute of Development Studies of the University of Helsinki. In addition to purely academic work Professor Kivimäki has been a frequent consultant to the Finnish, Danish, Dutch, Russian, Malaysian, Indonesian and Swedish governments, as well as to several UN and EU organizations on conflict and terrorism.

Notes

1 Bush refers to Putin as “Vladimir” or “my friend Vladimir” four times during the formative six months when ideology became an existential threat to the US in 2004 – this is as many times as he said “President Putin” or “President Vladimir Putin”, without adding that he is Putin’s friend or that he enjoys working him. Bush says “Vladimir Putin”, while emphasising that he is a friend, five times during this same period. Furthermore, Bush is explicit about the fact that Russia and the US have a common global enemy in terrorism (see, for example, Bush Citation2005a, 270).

2 This is the last year that, at the time of textual analysis, had been compiled by the US government in a biannual PDF format that the NVivo 12 software is able to analyse.

3 There are instances of agencies acting in secrecy that have had concrete consequences through the actions of secret agents. Some of the consequences of the public securitisation of ideologies moved to this secret realm just as political justification of the surveillance of ordinary people enabled secret, illegal practices among the intelligence community. Certain practices re-entered the realm of public politics with the revelations of Edward Snowden.

4 Testing the variables used for this study by using the Shapiro-Wilk W test reveals that none of them are normally distributed. Scatterplots of the relationship between these variables also show that many of these relationships are not necessarily linear and that data is not equally distributed along the regression line (homoscedasticity). I thus used the Spearman correlation test for this article.

5 Of all the words of securitisation, “threat” (and lexis related to different kinds of threats, such as terror) indicates the securitising utterance best: it is the association between a declared existential threat with an issue area that defines a securitising utterance. Once the audience has accepted the association and policies start following the social reality that it constitutes, the securitised issues area can be assumed to become associated with “security”-words. Yet even a superficial investigation of the associations of biannual frequencies between “ideology” and “security” reveals a moderate and statistically significant association (0.3016, p = 0.0333, n = 50). In the period after 1989, the frequency of “security” in presidential utterances was at its highest in the second half of 2004 and at its second highest during the first half of 2005, as might be expected.

6 According to Bush (to a domestic audience): “Al Qaida and the other global terror networks recognize that the defeat of Saddam Hussein’s regime is a defeat for them” (Bush Citation2003, 1062).

7 “They want to spread their ideology of hatred by forcing America to retreat from the world in weakness and fear” (Bush Citation2004a, 916).

8 Yet, according to the data Iraq did not suffer any terrorist fatalities during Saddam Hussein’s rule (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) Citation2019).

9 See (Bush Citation2005f, 1784). In his speech at the Council on Foreign Relations, 7 December 2005, Bush again suggested that Saddamists needed to be defeated militarily (see Bush Citation2005g, 1821).

10 If we look at absolute numbers instead of the percentage of sentences share of ideology, both Iraqi and Afghan elections produce statistically significant associations.

References

- Ackerman, S. 2021. Reign of Terror. How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump. New York, NY: Penguin, Random House.

- Ackerman, G. A., and M. Burnham. 2021. “Towards a Definition of Terrorist Ideology.” Terrorism and Political Violence 33 (6): 1160–1190. doi:10.1080/09546553.2019.1599862.

- Al-Sumait, F., C. Lingle, and D. Domke. 2009. “Terrorism’s Cause and Cure: The Rhetorical Regime of Democracy in the US and UK.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 2 (1): 7–25. doi:10.1080/17539150902752432.

- Angstrom, J. 2011. “Mapping the Competing Historical Analogies of the War on Terrorism: The Bush Presidency.” International Relations 25 (2): 224–242. doi:10.1177/0047117811404448.

- Bacevich, A. 2005. The New American Militarism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Balzacq, T., S. Léonard, and J. Ruzicka. 2016. “‘Securitization’ Revisited: Theory and Cases.” International Relations 30 (4): 494–531. doi:10.1177/0047117815596590.

- Blumer, H. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Burke, K. 1966. Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bush, G. W. 2003. “Remarks at the American Legion National Convention in St. Louis, Missouri, August 26, 2003.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2003, Book 2, 1059–1064. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2004a. “Commencement Address at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana May 21, 2004.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States 2003, Book 1, 914–917. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2004b. “Interview With Al-Ahram International May 6, 2004.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2003, Book 1, 791–799. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2004c. “Remarks at the Dedication of the National World War II Memorial May 29, 2004.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2004, Book 1, 942–945. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2004d. “Remarks at the National Defense University February 11, 2004.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2003, Book 1, 200–205. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2004e. “Remarks at the United States Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania May 24, 2004.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2003, Book 1, 919–925. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2004f. “Remarks in a Discussion at Kutztown University of Pennsylvania in Kutztown, Pennsylvania July 9, 2004.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2004, Book 2, 1251–1266. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2004g. “Remarks to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee May 18, 2004.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2004, Book 1, 894–899. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2004h. “The President’s News Conference April 13, 2004.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2004, Book 1, 557–571. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2005a. “Interview With Russian ITAR–TASS February 18, 2005.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2005, Book 1, 269–270. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2005b. “Remarks at the Associated Builders and Contractors National Legislative Conference June 8, 2005.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2005, Book 1, 949–958. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2005c. “Remarks at the United Nations Security Council Summit in New York City September 14, 2005.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2005, Book 2, 1434–1435. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2005d. “Remarks in a Discussion at Mid-States Aluminium Corporation in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin July 14, 2004.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States 2004, Book 2, 1316–1338. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2005e. “Remarks in a Discussion on Strengthening Social Security in Raleigh, North Carolina, February 10, 2005.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2005, Book 1, 199–213. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2005f. “Remarks on the War on Terror in Annapolis, Maryland, November 30, 2005.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2005, Book 2, 1782–1790. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2005g. “Remarks to the Council on Foreign Relations, December 7, 2005.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States 2005, Book 2, 1820–1828. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2005h. “Remarks to the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia and a Question-and Answer Session in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania December 12, 2005.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2005, Book 2, 1836–1849. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. W. 2007. “Remarks at a Swearing-In Ceremony for J. Michael McConnell as Director of National Intelligence, February 20, 2007.” In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 2007, Book 1, 162–164. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Bush, G. H. W., W. J. Clinton, G. W. Bush, et al. 1989. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Charon, J. M. 1979. Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration. Prentice-Hall.

- Chivvis, C. 2017. Understanding Russian ‘Hybrid Warfare’: And What Can Be Done About It. RAND Corporation. doi:10.7249/CT468.

- Cohen, E. A. 2017. “How Trump Is Ending the American Era.” The Atlantic, October. Accessed October 11, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/10/is-trump-ending-the-american-era/537888/?utm_source=twb.

- Croft, S. 2012. Securitizing Islam: Identity and the Search for Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Doty, R. L. 1996. Imperial Encounters: The Politics of Representation in North/South Relations (:, 1996). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Foucault, M. 1994. The Order of Things. New York: Vintage Books.

- Gilkes, S. 2016. “The Birth of Terrorist Deradicalization Programming in the U.S.?” Accessed May 12, 2021. https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2016/10/03/the-birth-of-terrorist-deradicalization-programming-in-the-u-s/.

- Hamilton, M. B. 1987. “The Elements of the Concept of Ideology.” Political Studies 35 (1): 18–38. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1987.tb00186.x.

- Holland, J. 2013. Selling the War on Terror: Foreign Policy Discourses After 9/11. London: Routledge.

- Homolar, A. 2011. “Rebels Without a Conscience: The Evolution of the Rogue States Narrative in US Security Policy.” European Journal of International Relations 17 (4): 705–727. doi:10.1177/1354066110383996.

- Homolar, A., and P. A. Rodríguez-Merino. 2019. “Making Sense of Terrorism: A Narrative Approach to the Study of Violent Events.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 12 (4): 561–581. doi:10.1080/17539153.2019.1585150.

- Jackson, R. 2005a. “Security, Democracy, and the Rhetoric of Counter-Terrorism.” Democracy and Security 1 (2): 147–171. doi:10.1080/17419160500322517.

- Jackson, R. 2005b. Writing the War on Terrorism: Language, Politics and Counter-Terrorism. Manchester University Press.

- Jackson, R. 2016. “Genealogy, Ideology, and Counter-Terrorism: Writing Wars on Terrorism from Ronald Reagan to George W. Bush Jr.” Studies in Language & Capitalism 1: 163–193.

- Keating, V. C., and O. Schmitt. 2021. “Ideology and Influence in the Debate Over Russian Election Interference.” International Politics. doi:10.1057/s41311-020-00270-4.

- Kivimäki, T. 2022. Data on the Securitization of Ideologies in US Presidential Speech. Bath: University of Bath Research Data Archive. doi:10.15125/BATH-01127.

- Knight, K. 2006. “Transformations of the Concept of Ideology in the Twentieth Century.” American Political Science Review 100 (4): 619–626.

- Kurtz, G., and M. M. Jaganathan. 2016. “Protection in Peril: Counterterrorism Discourse and International Engagement in Sri Lanka in 2009.” Global Society 30 (1): 94–112. doi:10.1080/13600826.2015.1092421.

- Laustsen, C. B., and O. Wæver. 2000. “In Defence of Religion: Sacred Referent Objects for Securitization.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 29 (3): 705–739.

- Lee, M. J. 2017. “Us, Them, and the War on Terror: Reassessing George W. Bush’s Rhetorical Legacy.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 14 (1): 3–30. doi:10.1080/14791420.2016.1257817.

- Löfflmann, G. 2015. “Leading from Behind – American Exceptionalism and President Obama’s Post-American Vision of Hegemony.” Geopolitics 20 (2): 308–332. doi:10.1080/14650045.2015.1017633.

- Malinova, O. 2014. ““Spiritual Bonds” as State Ideology.” Russia in Global Affairs October/December (4). Accessed June 10, 2021. https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/spiritual-bonds-as-state-ideology/.

- National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). 2019. The Global Terrorism Database. College Park: University of Maryland.

- Patterson, M., and K. R. Monroe. 1998. “Narrative in Political Science.” Annual Review of Political Science 1 (1): 315–331.

- Perelman, C., and L. Olbrechts-Tyteca. 1968. The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame.

- Phillips, N. 2007. “The Limits of ‘Securitization’: Power, Politics and Process in US Foreign Economic Policy.” Government and Opposition 42: 158–189.

- Popper, K. 2012. The Open Society and Its Enemies. 5th ed. Oxon: Routledge.

- Said, E. W. 1997. Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (Fully Revised Edition). New York, NY: Random House.

- Schmidt, B. C., and M. C. Williams. 2008. “The Bush Doctrine and the Iraq War: Neoconservatives Versus Realists.” Security Studies 17 (2): 191–220. doi:10.1080/09636410802098990.

- Searle, J. 1976. The Construction of Social Reality. New York: Free Press.

- Smith, R. M. 2003. Stories of Peoplehood. The Politics and Morals of Political Membership. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Snegovaya, M. 2015. Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine: Soviet Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Warfare. Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine. Institute for the Study of War. Accessed June 10, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep07921.1.

- Spielvogel, C. 2006. “‘You Know Where I Stand’: Moral Framing of the War on Terrorism and the Iraq War in the 2004 Presidential Campaign.” doi:10.1353/rap.2006.0015.

- Tanter, R. 2003. Classifying Evil: Bush Administration Rhetoric Towards Rogue Regimes. Policy Focus 44. Washington, DC: The Washington Institute. Accessed February 28, 2022. http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/classifying-evil-bush-administration-rhetoric-and-policy-toward-rogue-regimes.

- Wæver, O. 1995. “Securitization and Desecuritization.” In On Security, edited by R. D. Lipschutz. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Wæver, O. 1999. “Securitizing Sectors? Reply to Eriksson.” Cooperation and Conflict 34 (3): 334–340.

- Wendt, A. 1998. Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge International Relations 67. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wodak, R. 2001. “A Discourse-Historical Approach.” In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer, 63–94. London: Sage.

- Yilmaz, I., E. Shipoli, and M. Demir. 2021. “Authoritarian Resilience Through Securitization: An Islamist Populist Party’s Co-Optation of a Secularist Far-Right Party.” Democratization 0 (0): 1–18. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1891412.