ABSTRACT

COVID-19, as a major public health crisis, has triggered nationalism to different degrees all around the world. This study utilises an online survey to explore the relationships between media use, media trust, and nationalism in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that the level of nationalism was still considerably high in China at the time of the pandemic and that the role of the media in nation-state building enterprises remains significant. It becomes more pervasive after the news media's adoption of digitalisation. Our study argues that contemporary China's expression of nationalism is socially constructed by media and rooted in its Chinese Confucian culture. Meanwhile, the Chinese government is increasingly designing the news media and manages social media. It has already successfully constructed a sense of nationalism to facilitate its own interests in response to the national crisis. This has led nationalism being embodied in the media's constructed social reality.

Introduction

The worldwide spread of COVID-19 was announced as a global pandemic by Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of the World Health Organization, in March 2020. The pandemic has already affected 218 countries and territories and has had a long-term influence in shaping the world’s economic and political future, leaving a profound cultural and psychological impact (Zhang and Jamali Citation2022). Bieber (Citation2020) notes that COVID-19 triggers psychological consequences of collective anxiety and leaves political and social outcomes that strengthen exclusionary nationalism. The pandemic has served as an amplifying event; fuelling existing nationalist sentiments (Bieber Citation2020; Zhang and Jamali Citation2022). This is seen at the state level in terms of the growing power and authority of the nation-state which “may have long-lasting effects for privacy, security and democracy” (Woods et al. Citation2020, 822). Moreover, nationalism also provides a roadmap for citizens dealing with these feelings during the hardship: retreating into their community, rallying around their flag, helping their own, looking to strong leaders for guidance, and blaming their problems on foreigners. In a nutshell, COVID-19 has managed to collectivize people, as they have resorted to following the trend of nationalism (Kloet, Lin, and Chow Citation2020). Woods et al. (Citation2020) find that nationalism is the on the rise in many countries, China is not an exception (Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f).

Nationalism is a constructed sense of belonging to a nation (Anderson Citation2006). Media in this sense plays an essential role in constructing and spreading nationalism (Anderson Citation2006) and reproducing nationalism and national identity (Billig Citation1995). Nationalist feelings are embedded in media production and daily life (Billig Citation1995; Anderson Citation2006). Previous research has already examined the role of digital media in nationalism in China, such as search engines (Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f), websites (Schneider Citation2018) and Weibo (Zhang, Liu, and Wen Citation2018; Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f), showing that what has been termed “digital nationalism” in China is on the rise (Leibold Citation2010). Fang and Repnikova (Citation2018) proposed that expressions of nationalism in China usually feature a top-down and bottom-up type of expression. This means that nationalist expression comes to be pragmatically reframed by the Chinese political elites (Zhao Citation2004), but, at the same time, it is also evident within grassroots political activity (Hyun and Kim Citation2015). Reflecting the subtle and delicate control of mass media and the education system (Zhao Citation1998), Chinese news content in both news media and social media has pro-regime features in which expressions of nationalism are the norm (Shen and Guo Citation2013; Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). However, some empirical studies have uncovered how users’ posts on the internet often criticise domestic political conditions (Fang and Repnikova Citation2018; Zhang, Liu, and Wen Citation2018), a tendency certainly apparent in China during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When the virus broke out in the Chinese city of Wuhan, from where it spread to the rest of the country and the world, China’s social media showed signs of the public’s anxiety and their dissatisfaction with the government responses that accumulated over a period of a few weeks from the start of the outbreak (Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). Although Chinese news media outlets have highlighted a positive image of the government’s success in terms of containing and controlling the pandemic (Zhao Citation2020), social media users have challenged the credibility of the news media (Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). Hence, COVID-19 triggered domestic distrust towards the government and mainstream news media. Some previous studies confirm that both mainstream media use and social media use positively predict nationalism (Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014; Shen and Guo Citation2013). However, such studies tend to select cases of international conflicts between China and foreign countries, which invariably trigger expressions of nationalism (Schneider Citation2018), and neither do they explore issues relating to the connections between media trust and nationalism. This paper aims to explore how the media influenced nationalism in China during the pandemic. Hence, this study examines the correlation between Chinese nationalism, media use and media trust during COVID-19 and tests whether news media that portrays the Chinese state in favourable terms impact the level and extent of nationalism expressed by Chinese citizens.

The authors conducted an online survey (sample size 669) collected from February 2020 to April 2020 in China to explore the research question. The study finds that both social media and mainstream media play a positive role in increasing nationalism in China. Overall, although the government’s nationalist propaganda does not eliminate ordinary people’s concerns about the government’s capacity to appease the domestic political sentiments and respond to public crises, the ubiquitous party propaganda still reinforces a sense of nationalism. This paper begins with a literature review focusing on nationalism and media, followed by a summary of previous studies of China’s digital nationalism and media, then introduces the role of media trust in general. Subsequently, this paper reports the results. Finally, the results will be reported and discussed.

Distinguishing news media and social media in China

News media plays a vital role in spreading information. However, with the arrival of the digital age, social media (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Tumblr, and Instagram) that relies on Internet-based technology and multidimensional information interaction also plays a vital role in yielding daily news, engaging politics (such as the constructive element of social media in Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2018) and crafting a cross-regional feeling of citizenship and identity (Kaplan Citation2018). Moreover, the rise of social media has also witnessed the identity transformation of ordinary people in news participation who have shifted to become news creators rather than newsreaders through a more “mercurial” lens (Morrison Citation2017). Hence, social media plays an alternative role to news media, offering a virtual public sphere where ideas and beliefs can be shared (Groshek and Koc-Michalska Citation2017; Zhang, Liu, and Wen Citation2018).

Nevertheless, news media has also adopted digitalisation which has currently failed to transform its official, exclusive, and professional nature. This is without doubt the case in China where mainstream newspapers like China Daily, People’s Daily, and Xinhua Daily all operate their own social media accounts, distribute news messages regularly, and engage with netizens frequently (Lu, Zhang, and Fan Citation2016). At the same time, due to “the opacity of Chinese media regulations”, social media accounts and operations are always required to censor themselves before posting. The concept of “internet sovereignty” was coined in a Chinese government White Paper in May 2010 to set up a more restrict redline for all internet usersFootnote1, which followed by the issue of “Public Pledge on Self-Regulation and Professional Ethics for China Internet Industry” (Xu and Albert Citation2017). In contemporary China, the two media categories, namely news media and social media (for example, Weixin, Weibo, QQ, and Baidu Tieba), are both routinely monitored and harshly censored by the CCP government (Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f; Lee, He, and Huang Citation2006; Schneider Citation2018). By deploying “‘hard' power (censorship)” and “‘soft' power (reshaping public opinion by promulgating ideologies such as nationalism)” together, China’s ruling regime has made the Internet a digital extension of its geo-political territory (Yan Citation2020, 5) which works to prevent potential ideological challenges. Moreover, the Chinese government frequently takes action to punish “insubordinate” social media users (Ruan, Knockel, and Crete-Nishihata Citation2021). In this way, the informal controls of social media have become part of national security and state stabilisation, thereby demonstrating the “will to power” of the Chinese authorities. Hence, posts which tend to stimulate collective social movements are more likely to be censored than posts that contain negative and even acrimonious criticisms the policies (King, Pan, and Roberts Citation2017). Although the distinction between news media and social media is extremely blurry in contemporary China, the most prominent feature of social media lies in the lack of top-down operating institutions disseminating news and information. Following the work of Hyun, Kim, and Sun (Citation2014) our study defines news media as newspapers, TV news and news websites, while social media refers to social networking sites and microblogs. The reason why this study still divides China media into news media and social media in this manner lies in how we would like to emphasise the individual or unofficial level of nationalist expression in face of the COVID-19 crisis. Therefore, general media trust in this study refers to the Chinese public’s trust in the overall media environment and news media trust refers to popular trust in the news media.Footnote2

Nationalism and media

Individual loyalty and devotion to the nation-state frequently surpasses other individual or group interests, and in this regard nationalism can be understood as an omniscient political ideology based on both the “continuous institutional reinforcement” and the conformity and will of the public (Malesevic 206, 28). However, nationalism is by no means a simply matter of the state projecting a static identity and nor just it be understood as mere loyalty to the nation state. Rather it is a particular, constructive, and historicised condition in which most human beings now find themselves (Smith Citation2009). Hence, it is crucial to reflect on how nationalism, a powerful product of modernist epistemology, is crafted and embedded into the legitimacy of the modern nation state and conceptions of the duties of citizens.

Anderson (Citation2006) defined nationalism as a sense of belonging to an imagined or illusory community. His observation indicates that most community members do not know each other; however, the same community members believe that they “live the image of communion” (Anderson Citation2006, 6). Guibernau (Citation2007, 11) also proposed that community members believe in the commonality of “culture, history, kinship, language, religion, territory, and destiny”, which plays a highly distinctive role in constructing a sense of national identity. Billig (Citation1995) also introduced the concept of “banal nationalism”, which refers to the subtle, unconscious, and unnoticed reproductions of nationalist habits or traditions (e.g. saluting the flag and watching national news). “On a daily basis, the nation is indicated, or ‘flagged', in the lives of its citizenry. Nationalism, far from being an intermittent mood in established nations, is the endemic condition” (Billig Citation1995, 6). The banal expressions and representations of nationalism should be understood as the existence of a nation always contributing to an unconscious part of common people’s everyday and routine life contexts. In other words, nationalism is not only a quality of gun-toting, flag-waving “extremists” but an idea that is quietly and rather imperceptibly reproduced by all of us in our daily lives (Billig Citation1995).

Inspired by Anderson’s “imagined community” where print media can bind mutually unacquainted people together by providing them with a sense of shared community identity (Anderson Citation2006, 6), the close relationship between (banal) nationalism and media has been acknowledged by previous researchers (Gellner Citation1983, 127; Hobsbawm Citation1990, 142; Nossek Citation2004; Szulc Citation2017). Hence, the citizen and his/her daily life are permeated by a nation-centric ideological remodeling in the “Age of Nationalism”, which is associated with the issue of daily media and its role in constructing nationalism (Szulc Citation2017). Characterised by the “bottom-up” engagement of public opinion transcending space–time limits, newly established digital communication has become a driving force “for the promotion and spreading of more visible and exclusive forms of nationalism” (Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez Citation2020, 332). Previous studies have already confirmed that nationalism is very intensive in both China’s media and social media (Schneider Citation2018; Zhao Citation2004). Zhang (Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f) determined that Weibo is filled with “banal nationalism”, especially on National Day. For example, Zhang (Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f) highlighted the fact that even posts that didn’t contain written expressions of nationalism, they often contained emojis of national flags, which created a nationalistic atmosphere. Moreover, the Chinese media’s reporting of COVID-19 related news has reproduced exceptionalism thinking about “China” and “the rest of the world” (Peng et al. Citation2020). Thus, a consensus can be reached that close ties exist between the news media, social media and nationalism. One study further ascertained that when people read biased news reports that paint China in a positive light for an extended period, it increases their level of nationalism (Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014), while political trust also has an impact on nationalism (Shen and Guo Citation2013). Hence, this study aims to draw on media use and media trust in order to further explore the relationship between nationalism and the media.

Chinese nationalism and media use

Before critiquing the practice of Chinese nationalism, we would like to present a particular and ambiguous aspect of it. On one hand, the humiliated past of modern Chinese history (since the First Opium War of 1840) has bred the official statement on Chinese nationalism that is fully sustained by the communist ideology and Chinese government which identifies with “patriotism” in China (Zhao Citation1998). To a certain degree, nationalism in China doesn’t only refer to the sense of China as a great nation or the cultural identity as Chinese but also to the political compliance with the CCP’s ruling legitimacy. On the other hand, Chinese nationalism is “revanchist”, with a strong colour of racism and xenophobism when disseminated among the common people from the Chinese elite (Cabestan Citation2005). Additionally, after entering the twenty-first century due to China’s economic miracle and its global influence, the pride of being Chinese has been extremely pervasive and deep rooted. Such nationalistic sentiments are driven from both the bottom and the top (Modongal Citation2016). A vivid example is the emergence of a young and female-led generation of nationalist activists who were labelled “Little Pink” during the 2016 Taiwanese presidential election. They “stridently defend China’s national honour online” (Fang and Repnikova Citation2018; Kuo Citation2017). More saliently, since Xi Jingping came to power in 2012, his “Chinese dream” discourse has made Confucianism and other traditional cultures a crucial element of maintaining Chinese national identity, linking these values to the CCP’s centenary history of struggle while, at the same time, intensifying the ideological foundation of Marxism and Maoism across-the-board (Rosenberger Citation2020). Teasing out the dominant characteristics, and the historical development of Chinese nationalism, is useful when analysing the nationalist logics at work within the current Chinese media landscape.

Chinese nationalism has been massively intensified by Chinese media propaganda (Zhao Citation2004). Chinese media is widely accepted as a party- state political apparatus (Duan and Takahashi Citation2017), which is owned, funded and monitored by the Chinese government (Chan and Qiu Citation2001). According to Bandurski (Citation2022), the Chinese media sets the news agenda in accordance with the “main theme” (主旋律), which is to mobilise national identity. Previous studies have proven that Chinese news media not only supports the continued governance of the CCP (Wang Citation2020) but that it could also reflect the Chinese government’s position (Liu and Yang Citation2015). One recent study even argues that the official media in China (such as the People’s Daily) are arms of the Chinese state that serve to legitimise CCP rule (Zhang Citation2021). Shen and Guo (Citation2013) propose that the framing of China’s news media is aligned with the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) ideology and interests in which a “positivity bias frame” is obviously operating in the Chinese news media (He Citation2006). Zhao (Citation1998) further concludes that the Chinese government utilises news media to promote a sense of nationalism. The nationalistic features of news media are revealed not only in its coverage of high profile events (e.g. the Beijing Olympic Games) but also within “routine reporting of nationalistic prototypes in mundane, nonpolitical contexts” (Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014, 592). The same pattern was also found in the case of COVID-19. China’s news media spreads a sense of nationalism by downplaying other nations’ performance and self-congratulating China’s containment of the pandemic (Yang and Chen Citation2020). Some of China’s news media even suggested that Western democracies have to learn from Beijing’s experience and “copy China’s homework” if they want to control the COVID-19 pandemic (Dubravčíková Citation2020). Recent studies have also found that the Chinese government is using media outlets to promote vaccine nationalism through implying that the Chinese government is a responsible government that freely vaccinates the domestic public while also acting as a powerful global power to assist worldwide (Zhang and Jamali Citation2022). Therefore, national identity and nationalism are consolidated via news media use (Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014; Shen and Guo Citation2013).

The Chinese propaganda system targets the Chinese domestic population to promote a sense of nationalism while also looking for pro-China narratives around the globe to influence overseas Chinese (Atlantic Council Citation2020). Hence, the Chinese government not only highlights the role of the media to stabilise it legitimacy, but it also seeks to use social media to promote the political legitimacy of CCP to domestical and overseas Chinese (Atlantic Council Citation2020). The extensive findings generally point to social media in China as being full of nationalist features (Zhao Citation2020; King, Pan, and Roberts Citation2017; Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f; Schneider Citation2018; Leibold Citation2010). According to the Atlantic Council (Citation2020), the Chinese government controls Chinese social media through the censorship of politically sensitive topics and anti-CCP discourse, as well as promoting pro-CCP discussion and narratives. For instance, the Chinese government promotes its ideology through the promotion of “positive energy” (正能量) to stabilise its control (Fang and Repnikova Citation2018; Atlantic Council Citation2020). The Chinese government also supports online nationalist activities if the activities do not harm the legitimacy of the Chinese government (Liu Citation2019). King, Pan, and Roberts (Citation2017) found that China’s social media is dominated by pro-regime posts, therefore, social media use is positive in relation to nationalism (Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014).

We also found the same pattern during the Covid-19 pandemic in that the Chinese bottom-up expression is full of the features of nationalism (Peng et al. Citation2020). The intensity of the internet users’ support for the CCP and their distrust of the Western system has occurred since the CCP’s relatively effective handling of the pandemic compared with that of Western democracies (Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). Zhao (Citation2020) found the same pattern where Chinese internet users taunted others on some of the Western countries’ poor performance during the pandemic. However, although the Chinese government aims to control the popular nationalist discourse, Chinese popular nationalism enjoys some autonomy (Yang and Zheng Citation2012). For instance, China’s social media users also challenged the CCP’s foreign policies (Fang and Repnikova Citation2018). China’s social media thus contains both pro-regime posts alongside a critical commentary of China (Zhang, Liu, and Wen Citation2018) which is having a controversial impact on the Chinese government’s rule. More importantly, although previous studies have examined the positive role of news media use and social media use in nationalism (Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014; Shen and Guo Citation2013), they usually use cases that are focused on the international conflicts between China and Japan or the United States, which is seen of as an impetus to increase China’s nationalistic level among Chinese internet users (Schneider Citation2018). What this paper aims to achieve is to determine the use of COVID-19, a public health crisis that has triggered domestic criticism, to examine the relationship between media use and nationalism. The following hypotheses were formulated:

H1: News media use will be positively correlated with nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H2: The use of social media to obtain news will be positively correlated with nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Media trust and media use

Although social media plays a vital role in the public receiving political news (Dutton et al. Citation2017; Newman et al. Citation2018), the level of trust in social media as a news source is low. Strömbäck et al. (Citation2020) held that social media challenges the trustworthiness of news media. Although the level of news media trust is increasingly higher in some areas such as Japan (Hanitzsch, Van Dalen, and Steindl Citation2017) and even the public might show a more conservative attitude towards online sources of political news (Besalú and Pont-Sorribes Citation2021), many countries face the situation of low media trust due to the challenge rising from social media (Prochazka and Schweiger Citation2019; Swift Citation2016). According to the 2018 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, there are an increasing number of people worried about fake news and disinformation on social media (Dubois et al. Citation2020). Even though individuals are more active in various forms of online news participation and a decreasing trend is shown for the popularity of news media due to the challenge of social media (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020), the level of trust in social media news is still lower compared to that of news media (Fletcher and Park Citation2017).

Trust is a “willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party” or a “willingness to take the risk” (Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman Citation1995). Hence, media trust could have an impact on the individuals’ attitudes and behaviour, such as civic engagement (Putnam Citation1993). In Skipworth’s view (Citation2011), media trust could positively reinforce the effect of the dissemination of a certain message. Strömbäck et al. (Citation2020) analyzed the relationship between media trust and media use and found it to be complicated. People utilise media not only for information-seeking but also for social utility, social identity needs, and entertainment (Blumler Citation2016; Rubin Citation2009; Tsfati and Cappella Citation2005). Individuals use the media in a manner that is sometimes more ritualised and habitual rather than instrumental and active (Rubin Citation2009). Meanwhile, structural and semi-structural factors also could influence people’s media use (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004). People usually select media based on their political views instead of the media that they trust (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020). In other words, people usually trust media forms that are aligned to their political standpoint. It can be concluded that the users’ preference for attitude-behaviour consistency is also crucial in the forming of the media users’ standards when selecting a media form.

Tsfati and Cappella (Citation2003) indicated that media trust is positively connected with news media use while also negatively affecting social media use, although social media consists of a large part of people’s news “diet”. Jackob (Citation2010) found the same pattern as Tsfati and Cappella (Citation2003). However, relatively few researchers have explored media trust in China where the media is highly controlled by the government. Although social media in China still follows the media logic of further disseminating the government’s interest (Schneider Citation2018; Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f), digital media still offers a public sphere in which to challenge the news media (Zhang, Liu, and Wen Citation2018). During the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, social media challenged the credibility of the news media. However, news media also repeatedly framed the government’s success in containing and controlling the pandemic in positive terms (Zhao Citation2020). As a consequence, it is crucial to examine whether news media has a higher level of media trust than social media and the relationship between the level of news media trust and media use in China, especially during the ongoing pandemic. The above observation and analyses resulted in the following hypotheses:

H3: News media will result in more media trust than social media during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H4: A higher level of news media trust will be positively correlated with news media use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H5: A higher level of news media trust will be negatively correlated with the use of social media.

Media trust and nationalism

The public’s trust in news media plays an essential role in civic society and the process of political democracy (Newton Citation2016) since news media trust could reflect political trust (Marcinkowski and Starke Citation2018). In the case of COVID-19, we can observe that both news media and social media have played an essential role in supplying information. One study suggests that China’s news media trust could imply Chinese political trust (Shen and Guo Citation2013). Political trust is widely viewed as having a positive correlation with nationalism (van der Toorn et al. Citation2014). Nevertheless, no studies have examined the role of media trust in nationalism. China makes for an interesting case in this regard. China’s news media portrays the Chinese government in highly positive terms (Liu and Yang Citation2015; Zhao Citation2020), and studies of media use and nationalism in China also have a positive association (Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014; Shen and Guo Citation2013). Previous studies have already shown that news media trust and media use have a positive relationship (Tsfati and Cappella Citation2003). This study aims to examine the role of news media trust in nationalism (specifically the nationalist sentiments expressed by Chinese citizens) and, in doing so, we explore whether media use plays a mediating role in their relationship. The following hypotheses and research questions were raised:

H6. General media trust will have a positive relationship with nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H7. A higher level of news media trust will be positively correlated with nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic.

RQ1: During the COVID-19 pandemic, does news media that portrays the Chinese state in positive terms impact the level and extent of nationalism expressed by Chinese citizens?

Methodology

Sample

This study conducted an online survey from February 2020 to April 2020. China was on lockdown in Wuhan and other cities in Hubei at this period. Pan et al. (Citation2021) marks this period as the growing stage of the pandemic since the number of newly confirmed cases in this stage increased dramatically. The online survey was undertaken using a panel sample provided by a survey company based in Shanghai. The company had about 6,000,000 online registered users by the end of 2019. The company randomly sent the survey to its registered users. All participants who successfully filled in the online survey received compensation (cash) from the survey company. The online survey reached 1,020, and 669 users finished the survey. There were slightly more female participants (50.2%) than males. Most of the participants were aged between 30 and 50 (46.6%), followed by 18-30-year-olds (40.1%). In total, 3.9% of participants were under 18 and only 3% were older than 60. Approximately 41.4% of participants had received higher education (Bachelor’s degree or above) while 17.5% of participants reported that the highest education they had received was in middle school. The was 41.1% for senior high school. Most of the participants were workers or company employees (53.5%). Government officials accounted for 16% of the overall participants, followed by students (14.5%), others (13.9%), and the unemployed (2.1%). Most of the participants earned 1000–5000 RMB monthly (52.2%), while almost a quarter of participants earned 5000–10000 RMB per month (23.2%). The rest of them reported that their monthly salary was either under 1000 RMB (19.1%) or above 10000 RMB (5.5%). Approximately 36.9% of participants were Chinese Communist Youth League members, followed by non-partisan group members (36.8%), CCP members (20%), and Chinese Democratic Party members (6.3%).

Measures

Nationalism

This study utilised the Perceived Cohesion Scale to measure the level of nationalism during COVID-19 (Bollen and Hoyle Citation1990). To gain an insight into the respondents’ nationalistic attitudes, the online survey required the participants to answer questions on the extent to which they agreed with the presented statements. The survey used a 5-point scale where 1 represents total disagreement and 5 represents strong agreement. This scale aims to present the two underlying dimensions of cohesion: the sense of belonging and feeling of morale (Bollen and Hoyle Citation1990). To capture sense of belonging, this study asked: “I feel a sense of belonging to China during the COVID-19 pandemic; I feel that I am a member of China during the COVID-19 pandemic; I see myself as part of China during the COVID-19 pandemic”. To capture feelings of morale, three items were used: “I am enthusiastic about China during the COVID-19 pandemic; I am happy to live in China during the COVID-19 pandemic; China is one of the best nations in the world to deal with the COVID-19”. Overall, the scale contained six questions with which to measure nationalism (M = 3.88, SD = 0.93, α = 0.895).

Media use

Media use was measured by a 5-point scale (1 refers to never and five refers to always). The participants needed to answer questions on the frequency (media use) with which the participants obtained news regarding COVID-19 during the pandemic through newspapers (M = 3.72, SD = 1.2), TV news (M = 3.95, SD = 1.1), and news websites (M = 3.97, SD = 1.0) respectively. The participants also needed to fill in answers for the frequency of them obtaining news regarding COVID-19 during the pandemic from social media (social networking sites and microblogs) (M = 4.19, SD = 0.94). Moreover, this study also asked the participants which channel they used to receive the news regarding COVID-19, measured using a multiple-choice format (newspaper, TV, news website, or social media).

Media trust

This study employed Kohring and Matthes’s (Citation2007) method to measure media trust. To calculate the overall level of media trust, the participants were required to answer the extent to which they agreed with various statements. The survey used a 5-point scale where 1 represents total disagreement and 5 represents strong agreement. The statements were

The news media are fair when covering news related to the COVID-19; the news media are unbiased when covering news related to the COVID-19; the news media tell the whole story when covering the news regarding the COVID-19; the news media are accurate when covering the news; the news media separate facts from opinions when covering news regarding the COVID-19. (M = 3.95, SD = 0.91, α = 0.916)

To explore whether news media is more trustworthy than social media, the survey required the participants to fill in the extent to which they agree with the following statements using a 5-point scale. This is where 1 represents total disagreement and 5 represents strong agreement. The statements were

The news media are fairer than social media when covering news related to the COVID-19; the news media are more unbiased than social media when covering news related to the COVID-19; the news media could tell the whole story compare to social media when covering the news regarding the COVID-19; the news media are more accurate than social media when covering the news; the news media separate facts from opinions compare to social media when covering news regarding the COVID-19. (M = 3.95, SD = 0.92, α = 0.921)

This study also used the six demographic variables as the control variables, specifically gender, age, education level, employment, income, and political membership.

Results

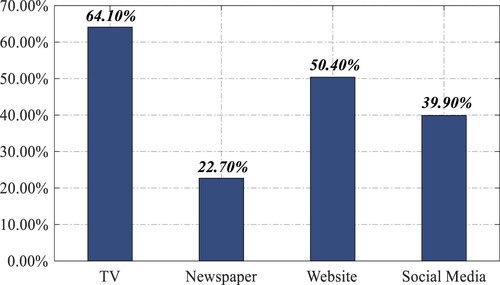

This study demonstrates that the level of nationalism in China was relatively high during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, this paper also reveals that the TV is still the main channel (64.1%) through which the public gain information, followed by websites (50.4%), social media (39.9%), and newspapers (22.7%). However, it is worth noting that although social media is not a major news source that the public use to gain COVID-19 information, the Chinese public spends most of their time exploring COVID-19 news on social media (M = 4.19), followed by news websites (M = 3.97), TV news (M = 3.95) and newspapers (M = 3.72). The participants also reported that the level of general media trust is high in China during the first lockdown in Wuhan and Hubei.

H1 predicted that news media use is positively correlated with nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic. supports this hypothesis. After controlling for the demographic variables, news media use was found to be positively associated with nationalism (β = .47; p < .001). H2 predicted that the use of social media to obtain news will be positively correlated with nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results show that the more people use social media for news specific to COVID-19, the stronger the level of nationalism that they hold (β = .45; p < .001). Besides this, we found that as one of the demographic variables – education – was positively related to nationalism in relation to both news media use (β = .21; p < .001) and social media use (β = .13; p < .001).

Table 1. Predictors of the correlations between news media use, social media use, and nationalism.

H3 predicted that news media has received more media trust than social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. The participants reported that the mean of media trust for mainstream media is 3.95. The median for nationalism is 4 and the mode is 5 (47.9%) which indicates that most of the participants choose to report a score above 4. The results support hypothesis 3 ().

Table 2. Descriptive statistics on the level of news media trust in China during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H4 was supported as a higher level of news media trust is positively correlated with news media use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Before including the other demographic variables in the hypothesis analysis, news media trust has a robust positive association with new media use (β = .70; p < .001). H5 states that a higher level of news media trust will be negatively correlated with the use of social media. rejects this hypothesis and shows that the relationship between news media trust and the use of social media is positively correlated (β = .48; p < .001).

Table 3. Predictors of the correlations between news media trust, news media use, and the use of social media.

H6 was supported as general media trust has a positive relationship with nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic (β = .33; p < .001). Moreover, education also functions as a positive predictor in terms of testing the relationship between general media trust and nationalism (β = .19; p < .001). H7 predicted that a higher level of news media trust will be positively correlated with nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the findings from , this hypothesis is rejected as there is no positive correlation between news media trust and nationalism (β = .09; p < .1). RQ1 asked whether positive news media use mediates the relationship between news media trust and nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic. RQ1 specified that there is a positive relationship between nationalism and news media trust, and this linkage could be explained away by positive news media use. The result shows that news media trust has no relationship with nationalism unless news media use enters the equation. The result shows that the mediation effect is significant (t = 3.515, p < .01).

Table 4. Predictors of the correlations between general media trust, news media trust, and nationalism.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that TV programmes are still the dominant channel through which Chinese acquire news concerning COVID-19. This outcome echoes Shirk’s (Citation2007) study that found that the television still occupies a vital position as a way for the Chinese people to receive information. However, this may also be influenced by “Chinese lockdown policies” that require people to remain in their homes. It is, therefore, more likely that this facilitates more opportunities for Chinese people to seek out relevant news while watching TV. Although most of the participants reported getting their news from the TV, they devoted most of their time to social media, followed by news websites, TV news, and reading the newspaper. In other words, the TV remains the most popular means for people to acquire information, while social media constitute the most vital channel that consumes most of the people's time to receive COVID-19 related news. Hence, social media plays an ongoing and vital role for people to receive and share information during the pandemic (Zhao et al. Citation2020).

This paper details that the level of nationalism has been – and remains – relatively high during COVID-19. This result is aligned with the previous studies showing that the level of nationalism in China is high (Johnston Citation2017; Zhang, Liu, and Wen Citation2018; Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). On the one hand, the pandemic as a global public health crisis could invoke a sense of nationalism (Su and Shen Citation2020; Bieber Citation2020). On the other hand, the media has a significant effect on nationalism, especially the impact of positivity bias in the news media as this study has found. The media plays a significant role in reproducing nationalism unconsciously (Billig Citation1995). Chinese news media has been long understood to be the mouthpiece of the Chinese government which facilitates the spread of the interests of the Chinese government in turn (Shen and Guo Citation2013; Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). Chinese media has also frequently “hailed the superiority of Chinese political system and praised President Xi Jinping’s leadership when reporting anti-epidemic efforts” during the COVID-19 pandemic (Yang and Chen Citation2020, 2). The public’s sense of nationalism is thus reinforced during the pandemic when exposed to the Chinese news media.

Although this study shows that many distrust the posts from the government on social media during COVID-19, it also reproduces a sense of nationalism in an unconscious way (Billig Citation1995). Apart from many distrusting the news due to their skepticism of the Chinese government and the CCP, it may also enhance feelings of belonging to the Chinese community. Hyun, Kim, and Sun (Citation2014) emphasised that the diverse opinions from social media offer a space for internet users to select the topics that they are interested in. Internet users with a high level of nationalism will, therefore, read nationalistic news on social media. Ultimately, the existing nationalism is reinforced as a result. The Chinese government also cooperates with social media companies to design its social media platforms to promote the government’s interests and ideology (Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). For example, many official Chinese government’s departments, party-related agencies, and official media have set up their social media accounts to capture more diverse audiences. Although their content is more for entertainment, some of content still simply replicates and disseminates what is shown on the news media (Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014). This reinforces nationalism in a similar way to what the news media promotes (Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014).

News media trust has faced a historical low in many countries (Prochazka and Schweiger Citation2019; Swift Citation2016) but Chinese news media trust remains high, even during COVID-19. The Chinese public still choose to trust the authorities. However, it should be noted that the news media trust level is experiencing signs of decrement. This is because digital media, to some extent, liberalises the Chinese media environment (Yang Citation2009) which causes a lot of information (both pro- and anti-regime) to be viewed via the internet. For instance, Chinese social media users challenged the credibility and reliability of China’s news media in the early stages of the pandemic (Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). The Chinese receive COVID-19 related news from relatively diverse opinions and stances. However, this does not mean that social media replaces news media. News media is still relatively high in terms of the level of media trust compared to social media trust. Hence, the relatively higher news media trust that this study found partially echoes Wu and Sun’s (Citation2009) study where the Chinese people were found to have a high level of trust in the Chinese government. It could be argued that China’s news media represents authoritative and trustworthy sources. People prefer to consume updated information from trustworthy media (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020). Consequently, it is not surprising that positive news media trust impacts positively on news media usage (Hopmann, Shehata, and Strömbäck Citation2015). There are many sources from which people can receive news right now. People only select the news they trust (Flanagin and Metzger Citation2017). The more they trust the news media, the more likely they are to obtain information from said news media. It is also interesting to see that the news media trust is positively linked with social media use. One possible explanation for this is that the Chinese government also uses social media to release adequate authoritative information during the pandemic to eliminate panic and to promote the stability of the public sentiment. To some extent, social media is an alternative source for the public to use to gain COVID-19 information (Zhao et al. Citation2020). This is where China’s news media has failed to become a leading indicator (Liu et al. Citation2020). In short, the Chinese government is advancing its management and control of both news media and social media which has a huge impact on the public’s information-seeking behaviour.

This study also discovered that general media trust is positively correlated with nationalism. Although China’s news media did not capture the outbreak in a timely manner (Liu et al. Citation2020), China's news media offered valid information on the pandemic as an authoritative source of information (Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). This study confirms that trustworthy and effective media releases will reinforce the public’s sense of nationalism during the pandemic (Kolet, Lin and Chow Citation2020). However, it is rather unexpected that news media trust does not have a relationship with nationalism; nevertheless, news media use can have a mediating role in the relationship between news media trust and nationalism. This study posits that news media, for the purpose of building political trust, represent an artifact acting as the essential ingredient involved in promoting ideologies related to nationalism (Shen and Guo Citation2013). In other words, Chinese nationalism includes a sense of patriotism, which highlights a loyalty that may abate the influence of news media trust. The Chinese government’s patriotism education tends to blur the boundary between the nation, state, and political party (Zhao Citation2004). Hence, Chinese people display a strong national sentiment towards their country as well as the current ruling government or party, rather than one specific party. The authors believe this sentiment based on the fact that Chinese nationalism is influenced by Confucian culture (Townsend Citation1992). Chinese nationalism encompasses the Confucian spirit of “scholar-bureaucrat” (Shidafu). Moreover, the Chinese spirit of “scholar-bureaucrat” highlights the loyalty toward the current ruling party no matter what, which helps maintain the country’s prosperity (Townsend Citation1992). Furthermore, news media trust and nationalism have no relationship unless the news media project a mediating role. Thus, the authors believe China’s news media repeatedly spread stories about COVID-19 that trigger a sense of banal nationalism. The news related to China’s COVID-19 outlook permeates into daily Chinese situations, and this reinforces a sense of belonging to the Chinese community. It could also be argued that there is a significant impact on the populace that relates to the positivity bias in China’s news media as a framing practice for the purpose of social control; thus, ubiquitous party propaganda has had an impact on nationalism.

Overall, the advent of social media has posed a challenge to news media, but trust in news media trust is still higher than that in social media. All types of media nonetheless have a vital role in constructing and disseminating nationalist ideals that are accepted by the general public. Thus, emphasising a sense of nationalism is frequently mobilised by the state as a solution of various internal and external problems, and the Chinese government has successfully designed news media and social media to facilitate a sense of nationalism and to promote its interests. In addition, both the news media and social media produce a sense of “banal” nationalism due to the way that they cover news related to China. The mediating effects of news media use on news media trust via nationalism can be seen of as a success since China’s nationalism assumes an apparent detachment or even irrelevance from one specific political party’s leadership. Or, as this study suggests, China’s nationalism shows a sense of loyalty to the current ruling party and country. Hence, Chinese nationalism is constructed by media and rooted in the Chinese Confucian culture.

Conclusion

COVID-19, as a global health crisis, has had a significant impact on world politics and it has also triggered an outbreak of nationalism worldwide (Bieber Citation2020). This study confirms that China experienced high levels of nationalism amongst its citizenry during the pandemic. Crises such as wars, pandemics and other existential threats have always been a crucial moment to utilise propaganda in newspapers and other media channels to advocate nationalism and to enforce political identification with the nation. Hence, the media has still been vital when constructing and reproducing nationalism during the pandemic (Anderson Citation2006; Billig Citation1995; Schneider Citation2018; Zhang Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c, Citation2020d, Citation2020e, Citation2020f). Media trust is one of the most vital criteria when it comes to prompting the Chinese people to read the news, and the news media is widely regarded as more trustworthy than social media. Although social media is seen as a less trustworthy media source, the growth of social media does not appear to have dented nationalist attitudes because it serves to reproduce a banal and everyday form of nationalism. Moreover, the news media trust does not have a relationship with nationalism unless the media news media use plays a mediation role. This mediating effect implies that China’s nationalism demonstrates a sense of loyalty to the whole Chinese community rather than one specific political party’s leadership. Hence, media and Confucian culture play a vital role in China’s nationalism. Overall, the Chinese government increasingly uses the news media and social media as part of the CCP’s propaganda machine which has a significant impact on nationalism, while Chinese nationalism also shows a sense of autonomy.

However, this study also has some limitations. For example, despite various attempts, this study was unable to balance the age and education level of the participants. Most of the participants were still from the younger or middle generations. Therefore, they may be more nationalistic than the other age groups. Yang and Zheng (Citation2012) found that the younger generation in China is more nationalistic. Meanwhile, most of the participants (41.4%) gained their education from university or above. As Hoffmann and Larner (Citation2013) noted, university-educated Chinese people have relatively higher levels of nationalism. The results of the survey may also have some bias. Moreover, almost all the state-owned media outlets in China run their own social media accounts. Hence, it is hard to make a huge difference between the news media and social media in China. However, although this paper has these limitations, it still contributes to the understanding of the role of the media in nationalism in China.

Acknowledgements

The authors would deliver the specific thanks to the journal’s associate editor Dr Juanita Elias for her helpful suggestions and careful proofreading. The working draft was presented at the APSA Political Communication preconference. Thanks to Dr Joshua Scacco, Associate Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Communication at the University of South Florida, read the early draft and offering valuable feedback during the preconference.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dechun Zhang

Dechun Zhang, PhD candidate at Leiden Institute for Area Studies, Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands. His research interests are political communication, media and politics, China’s digital nationalism and computational social science.

Yuji Xu

Yuji Xu, PhD student at Department of Chinese and History, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Notes

1 The Information Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China in 2010 published a White Paper, “The Internet in China”, to highlight a concept of “internet sovereignty,” requiring all internet users in China, including foreign organizations and individuals, to abide by Chinese laws and regulations. http://www.china.org.cn/government/whitepaper/node_7093508.htm

2 General media trust largely refers to the degree of trust information from all media (information platform) in this country. In other words, it refers to generalized media trust or the trust in different types of media and in the news that is reported (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020). General media trust refers to the trust in the whole media environment, while news media trust refers to specific news outlets (newspapers, TV news and news websites) in this case (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020; Hyun, Kim, and Sun Citation2014).

References

- Anderson, B. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Atlantic Council. 2020. Chinese Discourse Power: China’s Use of Information Manipulation in Regional and Global Competition. Washington: Atlantic Council.

- Bandurski, D. 2022. “An Olympic Legacy of Media Control. Retrieved from The China Media Project.” https://chinamediaproject.org/2022/02/04/an-olympic-legacy-of-media-control/.

- Besalú, R., and C. Pont-Sorribes. 2021. “Credibility of Digital Political News in Spain: Comparison Between Traditional Media and Social Media.” Social Sciences 10 (5): 170. doi:10.3390/socsci10050170.

- Bieber, F. 2020. “Global Nationalism in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Nationalities Papers, 1–13. doi:10.1017/nps.2020.35.

- Billig, M. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage.

- Blumler, J. G. 2016. “The Role of Theory in Uses and Gratifications Studies.” Communication Research 6 (1): 9–36.

- Bollen, K. A., and R. H. Hoyle. 1990. “Perceived Cohesion: A Conceptual and Empirical Examination.” Social Forces 69 (2): 479–504.

- Cabestan, Je. 2005. “The Many Facets of Chinese Nationalism, China Perspectives” doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.2793.

- Chan, J. M., and J. L. Qiu. 2001. “China: Media Liberalization Under Authoritarianism.” In Media Reform: Democratizing the Media, Democratizing the State, edited by M. E. Price, B. Rozumilowicz, and S. G. Verhulst, 27–47. London: Routledge.

- Duan, R., and B. Takahashi. 2017. “The Two-Way Flow of News: A Comparative Study of American and Chinese Newspaper Coverage of Beijing’s Air Pollution.” International Communication Gazette 79 (1): 83–107.

- Dubois, E., S. Minaeian, A. Paquet-Labelle, and S. Beaudry. 2020. “Who to Trust on Social Media: How Opinion Leaders and Seekers Avoid Disinformation and Echo Chambers.” Social Media + Society 6 (2): 205630512091399.

- Dubravčíková, K. 2020. China’s Story About Covid-19: China to Praise, America to Blame, Europe to Learn. Central European Institute of Asian Studies. https://ceias.eu/chinas-story-about-covid-19-china-to-praise-america-to-blame-europe-to-learn/.

- Dutton, W., B. Reisdorf, E. Dubois, and G. Blank. 2017. “Social Shaping of the Politics of Internet Search and Networking: Moving Beyond Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Fake News.” SSRN Scholarly Paper: No. ID 2944191.

- Fang, K., and M. Repnikova. 2018. “Demystifying “Little Pink”: The Creation and Evolution of a Gendered Label for Nationalistic Activists in China.” New Media & Society 20 (6): 2162–2185. doi:10.1177/1461444817731923.

- Flanagin, A., and M. J. Metzger. 2017. “Digital Media and Perceptions of Source Credibility in Political Communication.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication, edited by K. Kenski, and K. H. Jamieson, 1–15. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fletcher, R., and S. Park. 2017. “The Impact of Trust in the News Media on Online News Consumption and Participation.” Digital Journalism 5 (10): 1281–1299.

- Gellner, E. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Groshek, J., and K. Koc-Michalska. 2017. “Helping Populism Win? Social Media Use, Filter Bubbles, and Support for Populist Presidential Candidates in the 2016 US Election Campaign.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (9): 1389–1407.

- Guibernau, M. 2007. The Identity of Nation. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hanitzsch, T., A. Van Dalen, and N. Steindl. 2017. “Caught in the Nexus: A Comparative and Longitudinal Analysis of Public Trust in the Press.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (3): 3–23.

- He, Z. 2006. “Chinese Communist Party Press in a Tug-of-War: A Political Economy Analysis of the Shenzhen Special Zone Daily.” In Power, Money, and Media: Communication Patterns and Bureaucratic Control in Cultural China, edited by J. L. Chin-Chuan Lee, 211–230. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Hobsbawm, E. 1990. Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hoffmann, R., and J. Larner. 2013. “The Demography of Chinese Nationalism: A Field-Experimental Approach.” The China Quarterly 213 (213): 189–204.

- Hopmann, D. N., A. Shehata, and J. Strömbäck. 2015. “Contagious Media Effects: How Media Use and Exposure to Game-Framed News Influence Media Trust.” Mass Communication & Society 18 (6): 776–798.

- Hyun, K. D., and J. Kim. 2015. “The Role of New Media in Sustaining the Status Quo: Online Political Expression, Nationalism, and System Support in China.” Information, Communication & Society 18 (7): 766–781.

- Hyun, K. D., J. Kim, and S. Sun. 2014. “News Use, Nationalism, and Internet Use Motivations as Predictors of Anti-Japanese Political Actions in China.” Asian Journal of Communication 24 (6): 589–604.

- Jackob, N. 2010. “No Alternatives? The Relationship Between Perceived Media Dependency, Use of Alternative Information Sources, and General Trust in Mass Media.” International Journal of Communication 4: 589–606.

- Johnston, A. I. 2017. “Is Chinese Nationalism Rising? Evidence from Beijing.” International Security 41 (3): 7–43.

- Kaplan, Andreas M. 2018. “Social Media, Definition, and History.” In Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining, edited by Reda Alhajj, and Jon Rokne, 1–4. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-7131-2_95

- King, Gary, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E Roberts. 2017. “How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression.” American Political Science Review 107 (2): 1–18.

- Kloet, J. D., J. Lin, and Y. F. Chow. 2020. “We are Doing Better: Biopolitical Nationalism and the COVID-19 Virus in East Asia.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (4): 635–640.

- Kohring, M., and J. Matthes. 2007. “Trust in News Media: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Scale.” Communication Research 34 (2): 231–252.

- Kuo, K. 2017. “Do We Really Need to Worry So Much About Chinese Nationalism?” SupChina. Accessed 10 October 2021. https://supchina.com/2017/02/24/really-need-worry-much-chinese-nationalism/.

- Lee, C.-C., Z. He, and Y. Huang. 2006. “Chinese Party Publicity Inc. Conglomerated: The Case of the Shenzhen Press Group.” Media, Culture & Society 28 (4): 581–602.

- Leibold, J. 2010. “More Than a Category: Han Supremacism on the Chinese Internet.” The China Quarterly 203: 539–559.

- Liu, H. 2019. From Cyber-Nationalism to Fandom Nationalism the Case of Diba Expedition in China. New York: Routledge.

- Liu, X., and Y. E. Yang. 2015. “Examining China’s Official Media Perception of the United States: A Content Analysis of People’s Daily Coverage.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 20 (4): 385–408.

- Liu, Q., Z. Zheng, J. Zheng, Q. Chen, G. Liu, S. Chen, and W.-K. Ming. 2020. “Health Communication Through News Media During the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak in China: Digital Topic Modeling Approach.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (4): e19118–e19118.

- Lu, B., S. Zhang, and W. Fan. 2016. “Social Representations of Social Media Use in Government: An Analysis of Chinese Government Microblogging from Citizens’ Perspective.” Social Science Computer Review 34 (4): 416–436.

- Marcinkowski, F., and C. Starke. 2018. “Trust in Government: What’s News Media Got to Do With It?” Studies in Communication Sciences 18 (1): 87–102.

- Mayer, R. C., J. H. Davis, and F. D. Schoorman. 1995. “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust.” The Academy of Management Review 20 (3): 709–734.

- Mihelj, S., and C. Jiménez-Martínez. 2020. Digital Nationalism: Understanding the Role of Digital Media in the Rise of ‘New’ Nationalism. Loughborough University. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/12656252.v1.

- Modongal, S. 2016. “Development of Nationalism in China.” Cogent Social Sciences 2 (1): 1235749. doi:10.1080/23311886.2016.1235749.

- Morrison, J. 2017. “Finishing the ‘Unfinished’ Story: Online Newspaper Discussion Threads as Journalistic Texts.” Digital Journalism 5 (2): 213–232.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. Levy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2018. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newton, K. 2016. “Trust, Social Capital, Civil Society, and Democracy.” International Political Science Review 22 (2): 201–214.

- Nossek, H. 2004. “Our News and Their News: The Role of National Identity in the Coverage of Foreign News.” Journalism 5 (3): 343–368.

- Pan, Wei, Ren-jie Wang, Wan-qiang Dai, Ge Huang, Cheng Hu, Wu-lin Pan, and Shu-jie Liao. 2021. “China Public Psychology Analysis About COVID-19 Under Considering Sina Weibo Data.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 713597. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713597.

- Peng, A. Y., I. S. Zhang, J. Cummings, and X. Zhang. 2020. “Boris Johnson in Hospital: A Chinese Gaze at Western Democracies in the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Media International Australia 177 (1): 76–91.

- Prochazka, F., and W. Schweiger. 2019. “How to Measure Generalized Trust in News Media? An Adaptation and Test of Scales.” Communication Methods and Measures 13 (1): 26–42.

- Putnam, R. D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rosenberger, C. 2020. “Make the Past Serve the Present: Cultural Confidence and Chinese Nationalism in Xi Jinping Thought.” In Research Handbook on Nationalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781789903447.00040

- Ruan, L., J. Knockel, and M. Crete-Nishihata. 2021. “Information Control by Public Punishment: The Logic of Signalling Repression in China.” China Information 35 (2): 133–157. doi:10.1177/0920203X20963010.

- Rubin, A. M. 2009. “Uses and Gratifications: An Evolving Perspective of Media Effects.” In The SAGE Handbook of Media Processes and Effects, edited by R. L. Oliver, 525–548. London: Sage.

- Schneider, F. 2018. “Mediated Massacre: Digital Nationalism and History History Discourse on China’s Web.” Journal of Asian Studies 77 (2): 429–452.

- Shen, F., and Z. S. Guo. 2013. “The Last Refuge of Media Persuasion: News Use, National Pride and Political Trust in China.” Asian Journal of Communication 23 (2): 135–151.

- Shirk, S. L. 2007. “Changing Media, Changing Foreign Policy in China.” Japanese Journal of Political Science 8 (1): 43–70.

- Skipworth, S. 2011. The Consequences of Trust in the Media: A Moderating Effect of Media Trust on the Relationship Between Attention to Television and Political Knowledge. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers. cfm?abstract_id=1766887.

- Smith, A. D. 2009. Ethno-Symbolism and Nationalism: A Cultural Approach. Oxon: Routledge.

- Strömbäck, J., Y. Tsfati, H. Boomgaarden, A. Damstra, E. Lindgren, R. Vliegenthart, and T. Lindholm. 2020. “News Media Trust and its Impact on Media Use: Toward a Framework for Future Research.” Annals of the International Communication Association 44 (2): 139–156.

- Su, R., and W. Shen. 2020. “Is Nationalism Rising in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic? Individual-Level Evidence from the United State.” Journal of Chinese Political Science, 1–19.

- Swift, A. 2016. Americans’ Trust in Mass Media Sinks to New Low. doi: 10.1007/s11366-020-09696-2.

- Szulc, L. 2017. “Banal Nationalism in the Internet Age: Rethinking the Relationship Between Nations, Nationalisms and the Media.” In Everyday Nationhood: Theorising Culture, Identity and Belonging After Banal Nationalism, edited by M. Skey, and M. Antonsich, 134–153. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Townsend, J. 1992. “Chinese Nationalism.” The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs 27: 97–130.

- Tsfati, Y., and J. N. Cappella. 2003. “Do People Watch What They do Not Trust? Exploring the Association Between News Media Skepticism and Exposure.” Communication Research 30 (5): 504–529.

- Tsfati, Y., and J. N. Cappella. 2005. “Why do People Watch News They do Not Trust? The Need for Cognition as a Moderator in the Association Between News Media Skepticism and Exposure.” Media Psychology 7 (3): 251–271.

- van der Toorn, J., P. R. Nail, I. Liviatan, and J. T. Jost. 2014. “My Country, Right or Wrong: Does Activating System Justification Motivation Eliminate the Liberal-Conservative Gap in Patriotism?” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 54: 50–60.

- Wang, G. 2020. “Legitimization Strategies in China’s Official Media: The 2018 Vaccine Scandal in China.” Social Semiotics 30 (5): 685–698.

- Woods, E. T., R. Schertzer, L. Greenfeld, C. Hughes, and C. Miller-Idriss. 2020. “COVID-19, Nationalism, and the Politics of Crisis: A Scholarly Exchange.” Nations and Nationalism 26 (4): 807–825. doi:10.1111/nana.12644.

- Wu, Y., and I. Y. Sun. 2009. “Citizen Trust in Police: The Case of China.” Police Quarterly 12 (2): 170–191.

- Xu, B., and E. Albert. 2017. “Media Censorship in China.” Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed 10 October 2021. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/media-censorship-china.

- Yan, F. 2020. “Managing ‘Digital China’ During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Nationalist Stimulation and its Backlash.” Postdigital Science and Education, 1–6. doi:10.1007/s42438-020-00181-w.

- Yang, G. 2009. The Power of the Internet in China: Citizen Activism Online. Columbia: Columbia University Press.

- Yang, Y., and X. Chen. 2020. “Globalism or Nationalism? The Paradox of Chinese Official Discourse in the Context of the COVID-19 Outbreak.” Journal of Chinese Political Science, 1–25. doi:10.1007/s11366-020-09697-1.

- Yang, L., and Y. Zheng. 2012. “Fen Qings (Angry Youth) in Contemporary China.” Journal of Contemporary China 21 (76): 637–653.

- Zhang, Z. 2020a. “China: Coronavirus and the Media.” European Journalism Observatory. https://en.ejo.ch/ethics-quality/china-coronavirus-and-the-media.

- Zhang, C. 2020b. “Covid-19 in China: From ‘Chernobyl Moment’ to Impetus for Nationalism.” Made in China Journal 5 (2): 162–165. doi:10.22459/MIC.05.02.2020.19.

- Zhang, D. 2020c. “China’s Digital Nationalism: Search Engines and Online Encyclopaedias.” The Journal of Communication and Media Studies 5 (2): 1–17. doi:10.18848/2470-9247/CGP/v05i02/1-19.

- Zhang, C. 2020d. “Covid-19 in China: From ‘Chernobyl Moment’ to Impetus for Nationalism.” Made in China Journal, 1–11.

- Zhang, D. 2020e. “Digital Nationalism on Weibo on the 70th Chinese National Day.” The Journal of Communication and Media Studies 6 (1): 1–19. doi:10.18848/2470-9247/CGP/v06i01/1-19.

- Zhang, C. 2020f. “Right-Wing Populism with Chinese Characteristics? Identity, Otherness and Global Imaginaries in Debating World Politics Online.” European Journal of International Relations 26 (1): 88–115.

- Zhang, D. 2021. “The Media and Think Tanks in China: The Construction and Propagation of a Think Tank.” Media Asia 48 (2): 123–138. doi:10.1080/01296612.2021.1899785.

- Zhang, D., and A. B. Jamali. 2022. China’s “Weaponized” Vaccine: Intertwining Between International and Domestic Politics. East Asia. doi:10.1007/s12140-021-09382-x.

- Zhang, Y., J. Liu, and J.-R. Wen. 2018. “Nationalism on Weibo: Towards a Multifaceted Understanding of Chinese Nationalism.” The China Quarterly 235: 758–783.

- Zhao, S. 1998. “A State-led Nationalism: The Patriotic Education Campaign in Post-Tiananmen China.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 31 (3): 287–302.

- Zhao, S. 2004. A Nation-State by Construction: Dynamics of Modern Chinese Nationalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Zhao, X. 2020. “A Discourse Analysis of Quotidian Expressions of Nationalism During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Chinese Cyberspace.” Chinese Journal of Political Science, 1–17.

- Zhao, Y., S. Cheng, X. Yu, and H. Xu. 2020. “Chinese Public’s Attention to the COVID-19 Epidemic on Social Media: Observational Descriptive Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (5): e18825–e18825. doi:10.1007/s11366-020-09692-6.