ABSTRACT

The expectation of developed countries’ leadership is institutionalised in the United Nations’ climate agreements. Hence, climate leadership discussion often builds on the experience of the Global North and ignores the non-western contexts. This article analyses how climate leadership is socially constructed through discourse by developed and emerging countries. Here, developed countries were limited to Australia, Canada, the EU, Japan, New Zealand, and the US, and emerging countries to the BASIC group, comprising Brazil, China, India, and South Africa. The analysis was conducted by drafting storylines and discourse-coalitions based on national speeches at the UN climate conferences in 2016–2019. The results underline that the two sides differ primarily in perceptions of leadership responsibility and problematisation but share ideas about transition as a problem solution. Furthermore, neither side constructs their own leadership on the basis of responsibility, and the demand for collective responsibility particularly benefits the Global North.

1. Introduction

The first UN agreement to combat climate change, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), was adopted in 1992. Following the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC), the Convention recognised the varying national circumstances to act for climate and divided all nations into developed (Annex I) and developing (non-Annex I)Footnote1 parties. Developed countries were expected to lead the efforts due to their greater historical emissions and capacity to act and developing countries’ higher vulnerability to climate change. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol was adopted to operationalise the Convention by setting emission reduction targets for the developed countries.

After Kyoto, the negotiations became increasingly complex while the US never ratified the protocol, Canada withdrew, and Australia, New Zealand and Japan announced that they would not participate in a second Kyoto period (Gupta Citation2016). During this time, the division between developed, and developing became more fragmented and new negotiation groups began to emerge (Blaxekjær and Nielsen Citation2015). The challenges in the negotiations led to the preliminary idea of an agreement with targets for all the parties. Following this, Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015 and requested all nations to submit their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the UNFCCC secretariat.

The CBDR-RC principle is institutionalised in all these agreements, but in the Paris text, it was adopted with the phrase “in light of different national circumstances” weakening the strict differentiation between the North–South (Albuquerque Citation2021). Nevertheless, the differentiation has remained a perennial question in climate negotiations before and during Paris (Okereke and Coventry Citation2016). The post-Paris negotiations have proven difficult, and the world is not on track to reach the Paris Agreement goal to limit the global average temperature rise to below 2°C or preferably 1.5°C above the pre-industrial levels (UNEP Citation2021). The year 2020 has appeared as a significant line in the post-Paris era dividing it into pre-2020 and post-2020 action; by this benchmark, parties were expected to increase their mitigation ambition and developed countries to mobilise USD 100 billion per year to address the needs of developing countries. As achieving these goals has proven challenging, the trust among parties has decreased.

The complexity of climate change and the large variety of negotiating actors underline the significance of leadership in the success of climate negotiations (Underdal Citation1994). Raising the level of ambition requires leaders, as leadership can reinforce trust among nations and accelerate others’ actions (Parker and Karlsson Citation2010). Post-Paris time creates a new era for potential new climate leaders. Although the Paris Agreement includes the traditional expectation of developed countries’ leadership, it allows new leaders to step up by committing all nations to act. Due to developed countries’ insufficient leadership, the expectations have increased for emerging countries; their growing capabilities and emissions have increased hopes for them to take the lead in tackling climate change in the post-Paris era.

Research on climate leadership has tended to analyse developed countries, particularly the European Union (EU) and the United States (US) (Parker and Karlsson Citation2018), but emerging countries’ potential to lead is increasingly recognised (see for example, Hochstetler Citation2012; Petrone Citation2019; Hurri Citation2020). Furthermore, a research gap has been identified on how the emerging powers shape outcomes in international organisations and how they understand appropriate behaviour in their mercurial position (Weinhardt Citation2020). I contribute to this discussion by deconstructing the narrow western view of climate leadership. I ask: is there a shared understanding of climate leadership within or between the Annex II and the BASIC groups in the post-Paris era? In addition, I ask how these groups attempt to position each other in this argumentative struggle on climate leadership?

To compare these two contexts, I utilise argumentative discourse analysis (ADA) and storyline and discourse-coalition concepts to identify patterns of coherence and reduce the discursive complexity (Hajer Citation1995). Storylines and discourse-coalitions were drafted based on material including national speeches from the UNFCCC Conference of Parties (COP) and joint statements from 2016 to 2019. I compare two groups: developed countries are defined as the Annex II parties, comprising Australia, Canada, Iceland, the EU, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, and the US, and emerging countries as the BASIC group, a coalition of Brazil, India, China, and South Africa.

The Annex I consist of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) members as of 1992 and economies in transition (EIT). However, because of EIT countries’ weaker economic position, a new sub-group of Annex II parties was formed out of richer developed countries (Gupta Citation2010). As of 20 May 2021, the UNFCCC explains on its website that Annex II parties are obliged to provide financial support for developing countries’ climate mitigation and adaptation and “take all practicable steps to promote the development and transfer of environmentally friendly technologies to EIT parties and developing countries”. Annex II has not represented as an explicit coalition in the negotiations but for the aim of this study, they represent the ones who were traditionally expected to take the lead. It is only by researching these parties, though as a loose group, that it is possible to understand how these traditional leaders construct leadership in the post-Paris era.

Power dynamics within the UNFCCC are changing as emerging countries increasingly influence the negotiations. The establishment of the BASIC group in 2009 was motivated by the wish to highlight their non-western historical and cultural experience and their shared Global South identity (Weinhardt Citation2020). The future of the BASIC group has been debated since its foundation because, despite their growing status in world affairs, the interests of these four countries differ widely and even conflict (Hallding et al. Citation2013). BASIC countries have emphasised the CBDR-RC principle but have accepted the bottom-up approach of Paris as it enables them to determine their climate action nationally (Albuquerque Citation2019). In 2020–2021, all four countries announced their net-zero targets, which can be considered a sign of willingness to carry more international responsibility. Due to their conflicting interests, the BASIC group cannot be expected to share a vision of climate leadership, and therefore, this study aims at understanding which issues they can agree on about climate leadership with each other and the developed countries.

In the following section, I briefly introduce climate leadership literature. Then, after an outline of the materials and method, I present the results, which underline that the two sides differ primarily in perceptions of leadership responsibility and problematisation but share ideas on problem solutions.

2. Climate leadership

Gupta (Citation2016) has divided the history of climate leadership at the UNFCCC into the three stages: leadership paradigm (pre-1996), conditional leadership (1997–2007), and leadership in recession (2008–2020). The leadership paradigm adopted by the Convention in 1992 committed the North to lead. The interest behind the leadership paradigm was to create a regime that included developing countries. This paradigm indicated mutual trust, the developed countries promised to act first, and they expected the developing countries to follow when the time would come. The conditional leadership stage began in 1997 after the US withdrawal from the Kyoto negotiations. Demand grew for the key developing countries, such as China and India, to increase their participation because they were claimed to have a competitive advantage over developed countries who were obliged to change their fossil-energy-based growth (Audet Citation2013). Finally, the stage of leadership in recession began with the economic crisis in 2008, as setting binding targets for developed countries proved impossible (Gupta Citation2016). Although Paris Agreement expects action from all, it nevertheless includes the traditional expectation of developed countries taking the lead. These paradigms describe the history of climate leadership at the UNFCCC, but the bottom-up approach of the Paris Agreement has the potential to change the paradigm in the post-Paris era. Does the stage of leadership in recession continue, or are there signs of a new paradigm with new potential leaders?

Analytically and empirically leadership has proven a challenging concept (for an overview, see Kopra Citation2020). It is challenging to define leadership as distinct from other bargaining behaviour and to set benchmarks for identifying leadership (Skodvin and Andresen Citation2006; Eckersley Citation2020). A leader provides vision and inspiration, suggests, and implements solutions to a problem (Underdal Citation1994; Young Citation1991). Leadership in multilateral negotiations is “an asymmetrical relationship of influence, where one actor guides or directs the behaviour of others towards a certain goal over a certain period of time” (Underdal Citation1994, 178). Leadership is an act between leader and followers; therefore, it should be deconstructed by analysing political processes (Nabers Citation2011). This research turns attention away from the individual leaders typically researched and instead understands leadership as “co-constructed by different actors that participate in finding solutions to collective environmental problems” (Uusi-Rauva Citation2010, 75).

Leadership is often presented as a universal and achievable concept when in reality; the context of leadership is seldom highlighted (Case et al. Citation2015). This narrow view and ignorance of the non-western context can lead to ethnocentric views on leadership. Furthermore, single-case studies have dominated discursive environmental research (Leipold et al. Citation2019). Although the comparative perspective increases the complexity of the research, in this study, I wish to broaden the view on leadership by comparing two contexts. A comparison between contexts can be the first step to better understanding the phenomenon but few studies have analysed leadership perceptions in different parts of the world (Moan and Hetland Citation2012).

Critical theorists have pointed out that UNFCCC negotiations and climate change discourse are guided by the interests, values, and experiences of the North and that this often passes unnoticed (Doyle and Chaturvedi Citation2010; Chakrabarty Citation2017; Sealey-Huggins Citation2017). The North–South aspect is significant for this study since the groups researched represent both sides of this division. Nevertheless, my intention is not to reinforce this binary division (Acharya and Buzan Citation2007). Instead, we should broaden our perspective from merely criticising the western perspective to detecting different narratives and storylines about the global (Hurrell Citation2016). I do not wish to formulate a non-western perspective on leadership; rather, this article aims to contribute to a non-universalizing climate leadership concept.

3. Storylines and discourse-coalitions

I look at leadership discursively with the help of storyline and discourse-coalition concepts based on Hajer’s ADA. The choice of method was influenced by three concerns: (1) a coalition focus easily overemphasises unity (Rajão and Duarte Citation2018), (2) nations’ negotiation positions seldom completely converge (Bueno and Pascual Citation2016), and (3) nations often participate in various blocs, complicating the analysis. As Annex II and BASIC parties certainly vary in their leadership framing, goals, and action, storylines reduce the discursive complexity within these heterogeneous groups (Jernnäs and Linnér Citation2019). Storylines enable actors to construct a generic perception of a physical or social phenomenon by utilising various discursive categories (Hajer Citation1995). The value of storylines is in their ability to draft common ground, particularly during uncertainty and change, as they are “the prime vehicles of change” (Lovell, Bulkeley and Owens Citation2009, 99; Hajer Citation1995, 63). The benefit of storylines in this context is their assumption of a mutual understanding. However, much of this mutual understanding is interpretative reading and actors typically have their variations of the story (Hajer Citation2006).

The lack of complete mutual understanding is helpful for political coalition building. Hajer presents this as a paradox that the vagueness of the storyline makes the coalition stronger. Discourse-coalition means “a group of actors that, in the context of an identifiable set of practices, shares the usage of a particular set of storylines over a particular period of time” (Hajer Citation2006, 70). The discourse-coalition approach recognises that membership in a coalition does not require sharing a similar worldview or core beliefs but an understanding of a policy problem (Bulkeley Citation2000). Bulkeley sees the benefit of the approach in allowing actors to move between discourse-coalitions by recognising that actors can subscribe to various storylines in different contexts. This fluidity separates discourse-coalitions from advocacy coalitions. The discourse-coalition approach enables analysing shared understandings that do not need to be promoted by a closely coordinated coalition. Discourse-coalitions are particularly suitable for climate change due to the emerging problems, constant policy learning and the spectrum of actors on different scales (Bulkeley Citation2000).

Jernnäs and Linnér (Citation2019) show that discourse-coalitions cannot be understood by merely comparing negotiation coalitions. Hence, the two negotiation groups are not expected to form two discourse-coalitions in this study. Instead, I compare the groups to explore if there is a discourse-coalition that could bridge the Annex II and BASIC groups. In addition, due to the heterogeneity of both groups, I research whether discourse-coalitions are found within the groups. As Annex II does not represent an explicit negotiation coalition and the BASIC group is suspected of their conflicting interests, searching for discourse-coalitions within the groups broadens the understanding of whether the members share common stances on climate leadership in the post-Paris era. Due to these reasons, even though the BASIC and the Annex II groups are taken as a starting point to enable the comparison between the traditional leaders and potential new leaders, the main convergent and divergent storylines within these groups are also discussed. In this light, the results also suggest whether these negotiation groups are relevant to be researched as groups in the post-Paris era. Although the wish is to avoid considering the groups as monolithic actors, a comprehensive analysis of national stances is not in the interest of this study.

Following the ideas of ADA, I approached leadership not as a semi-static concept but as an argumentative struggle where the actors attempt to achieve discursive hegemony by gaining other actors’ support for their vision on leadership and endeavouring to position others in a particular manner (Hajer Citation1995). Actors attempt to promote their storyline as the authorised base for the policy change (Nasiritousi, Hjerpe and Buhr Citation2014). Hajer (Citation2006, 70) sets criteria for a dominant discourse: discourse structuration and institutionalisation. By structuration, he means that many actors utilise the discourse to conceptualise the world, and by institutionalisation, a situation when a discourse is translated into institutional arrangements.

4. Materials and method

The material comprised national speeches in the high-level segments of the COPs in 2016–2019. This period represents the first five-year period of the post-Paris era excluding the year 2020. No high-level statements were available for 2020 because COP26 was postponed due to the covid pandemic. The high-level segments are an important forum for argumentative interaction because parties have a formal opportunity to justify their initiatives and position to others on the international level. Unlike the more quantitative approaches with broad data sets such as discourse network analysis, studies based on ADA often have more limited material, including policy statements or speeches (Bulkeley Citation2000; Lovell, Bulkeley and Owens Citation2009). In addition, discourse-coalitions and storylines focus on the role of linguistics (Jernnäs and Linnér Citation2019) and, therefore, require a close reading of the material.

The EU was considered as one entity because it represents itself as one bloc within the UNFCCC negotiations. Hence, speeches by individual EU countries were excluded from the material as the EU speeches were considered to explain the common stance of the Union. On the national level, the EU stance would have certainly proven more heterogeneous but the scope of this research was not to focus on individual countries per se but to find a common understanding among the traditionally expected leaders. This limitation meant also excluding speeches by Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland. Although they are not EU member states, they were excluded to reduce the complexity and amount of material. Altogether, 40 speeches were analysed: 24 Annex II and 16 BASIC speeches from COP22 Marrakech in 2016, COP23 Bonn in 2017, COP24 Katowice in 2018, and COP25 in Madrid in 2019. Contextualisation was supported with observations on-site at COP24 in December 2018, the SB50 Bonn conference in June 2019, and COP25 in December 2019. The material was collected online in text and video format. Statements available only in video format were transcribed as text files.

In addition, the material included nine joint statements by the BASIC group, which they typically publish twice a year related to the COP of the year. Nevertheless, the discourse-coalitions were formed based on the BASIC national speeches as the joint statements already present a joint stance of the BASIC group. The statements were included to complement the analysis by broadening the understanding of BASIC argumentation. Annex II does not represent a coalition; hence, joint statements from their side were unavailable.

Responsibilities, problematisations, and solutions are essential elements of policy discourses (Leipold and Winkel Citation2017). Therefore, my analysis builds on these three elements of leadership discourse and answers, from the actors’ viewpoint, how climate change is tackled, what is their responsibility and what is the position of others. I argue that climate leadership is an inherent part of the climate change solution; hence, these questions are relevant for the leadership discourse. The actors’ views on problem definition, solution, and responsibility form part of the process where they attempt to exercise power and impose their views on others.

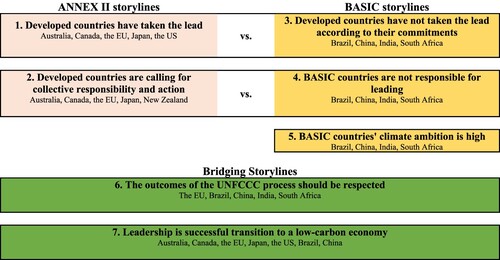

The analysis began with conventional qualitative content analysis allowing me to outline categories with shared meaning from the data (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). As I attempted to avoid pre-conceived categories for climate leadership, I analysed the material by approaching every sentence with four questions based on the policy discourse’s three elements: responsibilities, problematisations, and solutions. The questions were: whose responsibility climate leadership is, what is climate leadership, how successful climate leadership has been, and how is climate change tackled? Based on the answers, I identified 87 categories from the material that I organised with Atlas.ti computer software. These categories enabled understanding the variety of the material and gave me a better insight to draft the storylines. First, I researched every category to assign each an underlying argument, a rationale, for how they explain the perception of leadership (e.g. Jernnäs and Linnér Citation2019). Then, all the categories that shared a similar rationale were drafted as a storyline. An example of the analysis process is given in . It shows three categories that share a similar rationale; therefore, they were drafted as a storyline.Footnote2 Then, following the ideas of ADA, actors who subscribed to a given storyline in the material I defined as a discourse-coalition.

Table 1. An example of the analysis process.

As the storylines are not explicitly given in the material, the researcher drafts them (Tozer and Klenk Citation2018). Hence, although the aim is to increase the reliability of the research by justifying the storylines and providing quotes from the material, the results of discourse analysis are always subjective. This research is framed by my perspective as a white female scholar from the North; following Dengler and Seebacher’s example (Citation2019), I can only attempt to overcome my situatedness.

5. Results

Based on the analysis, I drafted seven storylines displayed in together with the discourse-coalitions. I detected two storylines shared by the Annex II parties, three BASIC storylines, and finally, two storylines that bridged the North–South divide to some extent. The material displayed only slight temporal variation during the period of 2016–2019. The most significant shift was the US stance after COP22 and the election of President Trump. However, surprisingly much remained unchanged in the US leadership claims; for instance, the US leadership in energy, investment, and technology was discussed in all the COPs investigated. Overall, the material included some differences particularly after national elections. For example, Brazil’s new president Bolsonaro has shifted Brazil’s negotiation position since 2019 by withdrawing from hosting the COP25 and threatening to withdraw Brazil from the Paris Agreement (Albuquerque Citation2021). Yet, the influence of this shift was less self-explanatory in the material than I anticipated. Evaluating this change’s influence on the BASIC group would require a longer perspective; now, the material covers only the first year of Bolsonaro’s administration.

5.1. Annex II storylines

Storyline 1: Developed countries have taken the lead.

Japan promises to collaborate with the international community and commits to take a lead in challenging climate change. (Japan at COP23)

Storyline 2: Developed countries are calling for collective responsibility and action.

Now the urgency is upon us and 2020 will test our collective ability to deliver. (The EU at COP25)

5.2. BASIC storylines

Storyline 3: Developed countries have not taken the lead according to their commitments.

The collective level of ambition will be higher to the extents to which developed countries live up to their historical responsibilities and take the lead in the global effort against climate change. (Brazil at COP22)

Climate justice debate typically contains three elements: the burden-sharing of emissions, vulnerability, and costs (Audet Citation2013, 371). In this storyline, the BASIC countries followed the climate justice idea and fought for the rights of developing countries. However, the storyline seemingly omitted the vulnerability aspect of climate justice altogether, and out of the four countries, South Africa was the only one that spoke about the climate vulnerability of African nations.

Storyline 4: BASIC countries are not responsible for leading.

COP25 should take stock of pre-2020 efforts and comprehensively identify the gaps on the part of developed countries in ambitions of emission reduction and support. Arrangements should be made to fill the gaps and avoid transferring present additional burdens to developing countries in the post-2020 period. (China at COP25)

Storyline 5: BASIC countries’ climate ambition is high.

Excellencies, India’s Hon’ble Prime Minister is amongst the thought leaders in this area and our commitment to climate action is second to none. (India at COP24)

5.3. Bridging storylines

Storyline 6: The outcomes of the UNFCCC process should be respected.

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is an inclusive, fair, comprehensive and balanced framework for the adoption of key implementing agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. We stress that the Convention is the core and central basis for ambitious and fair collective climate action. (South Africa at COP22)

In addition, the EU and BASIC countries both emphasised the importance of the Paris Agreement but this storyline involved interpretative reading of the agreement. The EU discussed the agreement as a new beginning, whereas the BASIC countries significantly highlighted the position of the Paris Agreement under the Convention. Convention was referred to more than the Paris Agreement. The BASIC group devotedly adheres to the architecture based on the Convention and does not wish to challenge it (Qingzhi Citation2017).

Storyline 7: Leadership is a successful transition to a low-carbon economy.

To be successful, it is not enough to take individual measures of containment of emissions and of adaptation. We need to change our development path, revise unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, and promote a low-carbon economy in the long run. (Brazil at COP23)

6. Discussion

Based on the analysis, there was more discursive coherence within the groups than between the Annex II and BASIC groups. For instance, most (5 out of 6) Annex II parties shared an understanding of climate leadership by subscribing to two storylines. However, the discourse-coalitions did not unequivocally follow the negotiation coalitions but provided insights into differences that might have been missed with a mere comparison of the negotiation coalitions.

For instance, the Annex II parties varied in their level of self-declared leadership and the way leadership was constructed. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand did not have as strong leadership claims than the EU, Japan, and the US. The US stood out from the group during the Trump administration because of their stance on mitigation and the UNFCCC. Nevertheless, the US speeches included strong leadership claims despite withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, positioning US leadership outside UNFCCC shared policies.

BASIC countries shared a broader understanding of climate leadership; all four countries subscribed to three storylines in their national speeches. Despite their shared understandings, communication of the BASIC joint statements was narrower than topics underlined in their national speeches. The demands in their joint statements correspond well with earlier research on their interests to support the CBDR-RC principle, right to economic growth, opposition of legally binding emissions reduction targets, and insistence on fair climate financing (Hallding et al. Citation2013; Hochstetler and Milkoreit Citation2014). These results suggest that much of the BASIC argumentation as a group has remained the same in the post-Paris era. Yet, their national speeches included more leadership claims. The speeches also showed differences between the BASIC countries in themes such as deforestation, vulnerability, energy, and South-South ideology. In addition, although all BASIC countries emphasised the insufficient support for developing countries, the claims by Brazil, China and India were more explicitly directed at developed countries than South Africa’s claims.

Most actors shared the storyline on transition, while the EU and BASIC countries shared the storyline on the importance of the UNFCCC. These storylines seemed to bridge the North–South divide, but they also explained the miscommunication at the UNFCCC. These leadership storylines were drafted based on three elements of policy discourses: responsibilities, problematisations, and solutions. In the following section, storylines are compared from each element’s perspective and finally, discussed vis-à-vis western-centrism.

6.1. Comparison of leadership responsibilities, problematisations, and solutions

Leadership storylines in neither side seemed to unequivocally aim towards the 1.5°C Paris Agreement goal. Furthermore, the Annex II parties and the BASIC group both outsourced their own responsibility to take the lead. The BASIC group recognised leadership as a responsibility, not just as their responsibility. With storylines 3 and 4, the BASIC group attached leadership particularly to developed countries’ historical responsibility enabling the construction of BASIC contributions as voluntary and exceeding their duties as developing nations. This “voluntary leadership” nevertheless underlines a contradiction between the material and current climate action by BASIC countries. The argumentation particularly in the BASIC joint statements outsourced climate leadership but in reality, climate action in the BASIC countries has been accelerating simultaneously. Thus, the North–South divide and rejection of climate action are less pronounced than the BASIC joint statements, in particular, would suggest. For instance, research has shown that, since 2007, India’s view of climate change as a threat to growth has begun to shift to a win-win discourse (Isaksen and Stokke Citation2014). This win-win discourse recognises India as an emerging economy with growing international responsibilities. This Indian example is an important reminder that the BASIC focus fails to reveal the whole story of the national situations: the BASIC argumentation seems to lag behind its members’ national positions (Hochstetler and Milkoreit Citation2014).

In contrast to the BASIC group, the Annex II parties often ignored the role of responsibility in the framings of their leadership. Developed countries’ responsibility to lead is institutionalised in the Convention. Yet in the material, instead of responsibility, the Annex II speeches constructed leadership as superiority by promoting their initiatives and including explicit leadership claims. Annex II parties’ leadership claims seemed to be driven more by win-win opportunities than from a sense of responsibility. Annex II storyline 1 conflicted with the BASIC storylines 3 and 4 about how successful the leadership of Annex II had been. While the Annex II speeches ignored communication about not having fulfilled their obligation to lead, the BASIC statements mainly focused on pinpointing the developed countries’ insufficient leadership.

Instead of their responsibility, the Annex II parties shifted responsibility into a collective issue and requested action by all with the storyline 2. To some extent, BASIC storyline 5 responded to this demand of collective responsibility: by promoting BASIC countries’ climate ambition as high, they accepted the request for collective action. However, throughout the material, it seemed that collective responsibility in the post-Paris era was interpreted differently between the Annex II and the BASIC parties. The multi-interpretability of the Paris Agreement exemplified this well: most of the Annex II parties seemed to frame the Paris Agreement as a turn towards a bottom-up defined collective responsibility. Instead, BASIC countries emphasised Paris Agreement as a continuation of the Convention, supporting developing countries’ differentiated position and developed countries’ obligation to lead.

Concerning problematisations, the storylines by both groups virtually dismissed their role as major emitters and emissions were discussed only in the context of the NDC targets. Hence, their influence on climate change was ignored. This avoidance is particularly worrying since, in the post-Paris era, parties plan their contributions based on their own assessment. However, this disregard of emissions follows the manner how leadership was framed in the pre-1996 climate leadership paradigm: developed countries accepted the terms of the Convention because they were framed as leaders instead of polluters (Gupta Citation2010). Developed countries have often preferred leadership framing based on their superior economic and technological capabilities (Okereke and Coventry Citation2016). Demands for emerging countries’ climate action, however, are often justified by their growing emissions. If developed countries agreed to the Convention terms with these favourable framings, why would the emerging countries accept a role as polluters rather than leaders?

Despite sharing the ignorance of emission levels, the framing of climate change differed between the Annex II and the BASIC parties. The BASIC group framed climate change as more of a developmental and social challenge, whereas Annex II parties viewed it more as an economic and technological question. In previous literature, the framing of climate change in the Convention has been criticised for mirroring this Annex II position (Gupta Citation2010). Because developed countries’ position is institutionalised in the climate agreement, it frustrates BASIC countries’ efforts to highlight developmental questions. In the material, BASIC countries’ growing disquiet over the pre-2020 gap in action suggests that their concerns were not addressed during 2016–2019.

Discourse-coalitions bridging these two groups were identified only concerning solutions. In storyline 6, the EU and BASIC countries both underlined the importance of multilateral negotiations and trust among parties. Because of the failure to decrease global emissions sufficiently until this point, the UNFCCC has been a target for plenty of criticism (Rajão and Duarte Citation2018). However, this storyline showed that the EU and the BASIC countries highly supported the UNFCCC process and its agreements. Only the US criticised the UNFCCC process and argued that results will also be achieved without the Paris Agreement. Noteworthy, this US stance has changed during the Biden administration.

Another bridging storyline (7) emphasised successful transition as the solution for climate change, which was the most widely subscribed storyline. This storyline exemplified well the paradox that the vagueness of the storyline strengthens the coalition (Hajer Citation2006); the nations subscribing to the storyline seemed to agree on the required transition but the terms of this transition were left ambiguous. The actors shared the support for economic growth with innovative, greener technologies. Noteworthy, China and India could have claimed leadership in this transition by their renewable energy growth rates but surprisingly, energy was ignored in the joint statements and discussed only moderately in the national speeches.

Discourses of ecological modernisation and transition are not exclusive to the discursive space of UNFCCC but represent a broader trend in the North and international organisations (Hajer Citation1995; Audet Citation2013). This storyline reinforces earlier findings of transition discourse bridging the North–South division in climate negotiations also in the post-Paris era (Audet Citation2013). Nevertheless, these discourses have been most researched in the western context (Leipold et al. Citation2019) and they have tended to omit justice and poverty issues important for the developing countries (Bäckstrand and Lövbrand Citation2006). This ambiguity was evident also within storyline 7 as justice of the required transition was framed differently. In this discourse-coalition, Brazil, Canada, and the EU gave space for the transition’s fairness, and outside this discourse-coalition, India and South Africa highlighted fairness significantly. Furthermore, justice claims varied for example in their construction on inter-generational or intra-generational equity. For example, the EU emphasised more inter-generational fairness while the BASIC countries intra-generational. This follows the trend of western climate change discourses attempting to replace intra-generational equity with inter-generational one (Doyle and Chaturvedi Citation2010).

It is important to remember that these storylines exclude important themes and alternative storylines about climate leadership because they describe the topics that Annex II and BASIC countries have chosen to address in their high-level speeches. This exclusion influenced for instance how responsibility was constructed as a state’s responsibility and the storylines omitted the responsibility of other important actors such as the fossil fuel industry. In addition, regarding solutions, the storylines did not address, for instance, reducing unsustainable consumption or fossil fuel phase-out.

6.2. Leadership storylines vis-à-vis western-centrism

The Annex II and BASIC parties’ leadership storylines are closely attached to the paradigms presented earlier (Gupta Citation2016). This finding underlines that leadership discourses are not only time and context dependent but also strictly rooted in how climate leadership is understood in the history of UNFCCC. BASIC storylines rely more on history, particularly on the leadership paradigm by demanding the developed countries to take the position of leaders. However, the BASIC storylines reflect also conditional leadership by showing ambition with their initiatives and to some extent accepting their growing international responsibility.

Annex II storylines primarily support the vision of leadership in recession (Gupta Citation2016) by demanding collective responsibility. Yet, the Annex II parties cannot escape the leadership paradigm as their leadership is institutionalised in the climate agreements. Developed countries attempt to deconstruct the North–South dichotomy by positioning emerging countries on the same line with them (Rajão and Duarte Citation2018). Collective responsibility benefits western interests because it allows developed countries to involve emerging countries while simultaneously maintaining their own role as “leaders”.

Although developed countries initiated this shift, developing countries have begun to show support for the deconstruction of the North–South divide, criticising, in particular, the positions of China and India (Prys-Hansen Citation2020). Despite this fragmentation, South believes that consensual decision-making in climate negotiations offers them leverage to balance the unequal power relations (Rajão and Duarte Citation2018). This leverage is to some extent true also in the context of the BASIC countries; they rely on the developing countries’ support if they wish to continue to position themselves as the advocates of the Global South. Particularly China is identified not only as emphasising the Global South unity but seeking a role as a leader of developing countries in global climate governance (Qi and Dauvergne Citation2022).

Underdal’s (Citation1994) leadership definition recognises this asymmetrical relationship of influence. Understanding how successfully the BASIC and Annex II parties gained other actors’ support for their vision on climate leadership would require a broader analysis of their followers’ responses. Although the BASIC and Annex II parties include the key powers in the negotiations in the post-Paris era, the focus of this study rules out other important actors such as the larger group of Annex I countries, other developing countries, coalitions such as the AOSIS, and non-governmental actors.

The BASIC countries have shown potential for climate leadership, which was evident in storyline 3. If the BASIC countries wish to claim a more substantial climate leadership role, how will they communicate their demands for developed countries’ leadership in the future? Storylines can help to answer this question, as they can create opportunities for change (Lovell, Bulkeley and Owens Citation2009). In the material, two strategies responded to the question. In the first strategy, the BASIC countries were constructing their climate leadership as responsible advocates for the Global South and highlighting their difference from the irresponsible developed countries. This strategy, applied particularly in the joint statements, follows the pre-Paris argumentation of the BASIC countries and hence, does not suggest a policy change for the post-Paris era.

However, according to the second strategy applied mainly in the national speeches, the demands for the developed countries were not nearly as strong as within the joint statements. In the speeches, their leadership claims were justified without the North–South characteristics. This change was not strong enough to create a storyline that BASIC countries would have taken the lead. However, it demonstrates a shift from the leadership paradigm in the post-Paris era while they simultaneously adhere to the paradigm in other storylines. This shift supports that policy change does not always occur in the intersections of storylines but also in dispersed and often overlooked spaces or niches (e.g. Lovell, Bulkeley and Owens Citation2009) such as nuances. These nuances might be ignored with a mere negotiation coalition focus. Tensions within the BASIC storylines emerge when their climate action and leadership claims increase. The increasing claim on leadership is visible in practice: for instance, China’s President Xi Jinping claimed in 2017 that they will take a driver’s seat in international climate negotiations (Zhang and Orbie Citation2021, 19).

If BASIC countries would like to claim a stronger climate leader role in the future, they will have to alter these storylines found in this study. This shift had started nationally but as a group, their argumentation showed only a slight development in 2016–2019. The BASIC group struggles to agree on the behaviour appropriate to their role. This challenge might result from the function of the group; instead of proactiveness, it has operated mainly as a defensive coalition calling for increased action by the developed countries. If these countries succeed in decoupling their development from fossil fuels, it will provide them with a shared experience that further distinguishes them from Annex II parties. This change would offer the BASIC group a possibility to continue with argumentation based on historical responsibility.

The experience of the North has been a determining factor in defining how climate leadership is discussed. The US and Europe have been norm makers in the post-Cold War era, but the position of emerging countries is changing; they have changed from norm takers socialised into the existing world order to norm makers alongside the EU and the US (Bueno and Pascual Citation2016; Jinnah Citation2017). However, the BASIC storylines still attached leadership to developed countries, and thus, it seemed that also their framing of climate leadership is dependent on the western experience and action. Although the emerging powers have gained more leverage in the negotiations, the increasing shift towards collective responsibility reflects the western perception of climate leadership. This western perception is converting to the universal idea of climate leadership. This development is one example of how western-centrism in climate negotiations often remains unnoticed and that, for example, developing countries’ definitions of climate leadership might be rooted in developed countries’ perceptions (Gupta and van der Grijp Citation2000; Chakrabarty Citation2017). Hence, this study supports the claims that the interests of the Global North often dominate the UNFCCC negotiations (Doyle and Chaturvedi Citation2010; Chakrabarty Citation2017; Sealey-Huggins Citation2017).

Climate equity within the UNFCCC has suffered from inconsistency between rhetoric, pledges, and action and has repeatedly been overrun by hard economic and power politics (Okereke and Coventry Citation2016). If the success of developed countries’ leadership depends on their treatment of the emerging powers (Vezirgiannidou Citation2015), successful BASIC leadership similarly requires that developing countries be treated fairly. In this light, the unequal power relations in climate negotiations have a significant role in determining whether and how the Paris Agreement goals will be achieved. Therefore, the mildness of other actors’ responses to the US Paris withdrawal in the material is worrying. It indicates weak practices for judging irresponsibility at the UNFCCC. The US example demonstrates well that although much of the climate governance research distinguishes the top-down approach of the Kyoto Protocol and the bottom-up approach of the Paris Agreement, both these approaches represent essentially bottom-up (Andresen Citation2015). Andresen justifies this by the fact that all international cooperation is voluntary and punishments mechanisms for example for the US for not following their contributions are weak.

7. Conclusions

In this article, I have compared storylines about climate leadership from the perspective of three policy discourse elements: responsibilities, problematisations, and solutions. BASIC countries relied on the institutionalised discourse of developed countries’ leadership responsibility, while Annex II parties emphasised the policy change into collective responsibility. However, both groups outsourced their own responsibility to lead by these arguments. Regarding problematisation, BASIC countries underlined the social and developmental questions more than the Annex II parties. Finally, these two groups shared most ideas regarding solutions; Australia, Canada, the EU, Japan, the US, Brazil, and China agreed that successful leadership requires transition into a low-carbon development.

Because of the heterogeneity of Annex II and BASIC parties, the strength of the storylines was in their ability to distinguish shallow and ambiguous discursive practices and hint about the differences in interpretations in this analysis. Although this focus does not cover how the storylines materialise in climate action or compare the national stances comprehensively, it tells about the policy discourses that constrain and enable the Annex II and BASIC groups as discursive subjects. Analysing shared understandings and re-ordering of meanings through storylines is important; due to the slowness of climate policy implementation, the greatest changes in climate policy have occurred at the level of policy discourse (Lovell, Bulkeley and Owens Citation2009). In addition to implementation, materialising the Paris Agreement targets rely on agreeing on the problematisations, responsibilities and solutions (e.g. Jernnäs and Linnér Citation2019). To tackle the climate crisis, these agreements must cross national borders and bridge the North–South division to increase the trust among parties at the UNFCCC.

The discourse-coalitions in this study show that there is more discursive coherence within the groups than between the Annex II and BASIC groups. Although most of the discourse-coalitions follow the lines of negotiation coalitions, the discourse-coalitions show variation within the groups and the discourse-coalitions of the bridging storylines included only some of the BASIC and Annex II countries.

International Relations is criticised for not fully acknowledging western-centrism, particularly related to historical narratives, theoretical categorizations, and political preoccupations (Hurrell Citation2016; Wilkens Citation2017). Due to the increasing request for collective responsibility, the focus in climate negotiations is turning from the dichotomy between developed and developing countries to the major emitters and the G20. However, this shift does not imply that the western-centrism of the UNFCCC would be disappearing. In whichever format, ethnocentrism does not represent a fruitful approach; rather, the deconstruction of climate leadership should highlight the dangers of representing one view as universal.

The global stocktake at the COP28 in 2023 will be the first opportunity to review who has shown leadership in the post-Paris era. It will be interesting to observe how the aftermath of the stocktake will recognise the North–South divide and how the BASIC discourses on leadership will develop in the foreseeable future if they wish to claim a stronger role as climate leaders. The discourse of leadership by the North is institutionalised in the climate agreements, which might lead it to be better recognised than for example Chinese leadership. By demanding collective responsibility, Annex II countries position the BASIC countries on the same line with them. Nevertheless, it does not mean they would necessarily admit them a leadership role.

The conflicting storylines between Annex II and BASIC parties should be assessed critically. On one hand, it is welcomed that the BASIC group continues with their pre-Paris argumentation that explicitly addresses the failure of developed countries to fulfil their institutionalised obligations. This criticism deconstructs the western-centrism of climate leadership by emphasising that the thus far most powerful actors in the negotiations have not honoured their commitment to lead. On the other hand, the motives for making these accusations should be carefully evaluated. The credibility of BASIC countries’ accusations for developed countries’ insufficient leadership increases if BASIC countries will show increased climate ambition. Hints about the growing acceptance of a greater role in the post-Paris era were found in this study. Nevertheless, their leadership efforts need to accelerate discursively and be supported with action for the Paris Agreement goals to be achieved. Therefore, BASIC countries’ climate ambition should not be overestimated at this stage.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The terms developed, Annex I, Annex II, Global North, and western countries are used interchangeably in this study. Japan is also included among the western countries to decrease possible confusion. Similarly, the terms developing, non-Annex I, and Global South are utilised interchangeably. Although recognizing the problems with the terminology “developed and developing countries”, these terms are used in this study because they are the established party groups within the UNFCCC.

2 Storyline included other categories in addition to these three.

References

- Acharya, A., and B. Buzan. 2007. “Why is There no non-Western International Relations Theory? An Introduction” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 7: 287–312. doi:10.1093/irap/lcm012

- Albuquerque, F. 2019. “Coalition Making and Norm Shaping in Brazil’s Foreign Policy in the Climate Change Regime.” Global Society 33 (2): 243–261. doi:10.1080/13600826.2019.1571482

- Albuquerque, F. 2021. “Climate Politics and the Crisis of the Liberal International Order.” Contexto Internacional 43 (2): 259–282. doi:10.1590/s0102-8529.2019430200002

- Andresen, S. 2015. “International Climate Negotiations: Top-Down, Bottom-Up or a Combination of Both?” The International Spectator 50 (1): 15–30. doi:10.1080/03932729.2014.997992

- Audet, R. 2013. “Climate Justice and Bargaining Coalitions: A Discourse Analysis.” International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 13: 369–386. doi:10.1007/s10784-012-9195-9

- Bäckstrand, K., and E. Lövbrand. 2006. “Planting Trees to Mitigate Climate Change: Contested Discourses of Ecological Modernization, Green Governmentality and Civic Environmentalism.” Global Environmental Politics 6 (1): 50–75. doi:10.1162/glep.2006.6.1.50

- Bäckstrand, K., and E. Lövbrand. 2019. “The Road to Paris: Contending Climate Governance Discourses in the Post-Copenhagen Era.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 519–532. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2016.1150777

- Blaxekjær, L., and T. Nielsen. 2015. “Mapping the Narrative Positions of New Political Groups Under the UNFCCC.” Climate Policy 15 (6): 751–766. doi:10.1080/14693062.2014.965656

- Bueno, M. P., and G. Pascual. 2016. “International Climate Framework in the Making: The Role of the BASIC Countries in the Negotiations Towards the Paris Agreement.” Janus.Net, e-journal of International Relations 7 (2): 121–140.

- Bulkeley, H. 2000. “Discourse Coalitions and the Australian Climate Change Policy Network.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 18: 727–748. doi:10.1068/c9905j

- Carvalho, A. 2005. “Representing the Politics of the Greenhouse Effect.” Critical Discourse Studies 2 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1080/17405900500052143

- Case, P., L. Evans, M. Fabinyi, P. Cohen, C. Hicks, M. Prideaux, and D. Mills. 2015. “Rethinking Environmental Leadership: The Social Construction of Leaders and Leadership in Discourses of Ecological Crisis, Development, and Conservation.” Leadership 11 (4): 396–423. doi:10.1177/1742715015577887

- Chakrabarty, D. 2017. “Politics of Climate Change is More Than the Politics of Capitalism.” Theory, Culture & Society 34 (2–3): 25–37. doi:10.1177/0263276417690236

- Dengler, C., and L. Seebacher. 2019. “What About the Global South? Towards a Feminist Decolonial Degrowth Approach.” Ecological Economics 157: 246–252. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.11.019

- Doyle, T., and S. Chaturvedi. 2010. “Climate Territories: A Global Soul for the Global South?” Geopolitics 15 (3): 516–535. doi:10.1080/14650040903501054

- Eckersley, R. 2020. “Rethinking Leadership: Understanding the Roles of the US and China in the Negotiation of the Paris Agreement.” European Journal of International Relations 26 (4): 1178–1202. doi:10.1177/1354066120927071

- Falkner, R. 2016. “A Minilateral Solution for Global Climate Change? On Bargaining Efficiency, Club Benefits, and International Legitimacy.” Perspectives on Politics 14 (1): 87–101. doi:10.1017/S1537592715003242

- Gupta, J. 2010. “A History of International Climate Change Policy.” WIRES Climate Change 1 (5): 636–653. doi:10.1002/wcc.67

- Gupta, J. 2016. “Climate Change Governance: History, Future, and Triple-Loop Learning?” WIRES Climate Change 7 (2): 192–210. doi:10.1002/wcc.388

- Gupta, J., and N. van der Grijp. 2000. “Perceptions of the EU’s Role. Is the EU a Leader?” In Climate Change and European Leadership. A Sustainable Role for Europe?, edited by J. Gupta, and M. Grubb, 67–81. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Hajer, M. 1995. The Politics of Environmental Discourse. Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hajer, M. 2006. “Doing Discourse Analysis: Coalitions, Practices, Meaning.” In Words Matter in Policy and Planning, edited by M. van den Brink, and T. Metze, 65–74. Utrecht: Netherlands Geographical Studies.

- Hallding, K., M. Jürisoo, M. Carson, and A. Atteridge. 2013. “Rising Powers: The Evolving Role of BASIC Countries.” Climate Policy 13 (5): 608–631. doi:10.1080/14693062.2013.822654

- Hochstetler, K. 2012. “The G-77, BASIC, and Global Climate Governance: A New Era in Multilateral Environmental Negotiations.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 55: 53–69. doi:10.1590/S0034-73292012000300004

- Hochstetler, K., and M. Milkoreit. 2014. “Emerging Powers in the Climate Negotiations” Political Research Quarterly 67 (1): 224–235. doi:10.1177/1065912913510609

- Hsieh, H. F., and S. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hurrell, A. 2016. “Beyond Critique: How to Study Global IR?” International Studies Review 18 (1): 149–151. doi:10.1093/isr/viv022

- Hurri, K. 2020. “Rethinking Climate Leadership: Annex I Countries’ Expectations for China's Leadership Role in the Post-Paris UN Climate Negotiations.” Environmental Development 35: 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2020.100544

- Isaksen, K. A., and K. Stokke. 2014. “Changing Climate Discourse and Politics in India. Climate Change as Challenge and Opportunity for Diplomacy and Development.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 57: 110–119. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.08.019

- Jernnäs, M., and B.-O. Linnér. 2019. “A Discursive Cartography of Nationally Determined Contributions to the Paris Climate Agreement.” Global Environmental Change 55: 73–83. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.01.006

- Jinnah, S. 2017. “Makers, Takers, Shakers, Shapers: Emerging Economies and Normative Engagement in Climate Governance.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 23: 285–306. doi:10.1163/19426720-02302009

- Kopra, S. 2020. “Leadership in Global Environmental Politics.” In The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies, edited by Nukhet Sandal. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.537.

- Leipold, S., P. Feindt, G. Winkel, and R. Keller. 2019. “Discourse Analysis of Environmental Policy Revisited: Traditions, Trends, Perspectives.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 445–463. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462

- Leipold, S., and G. Winkel. 2017. “Discursive Agency: (re-) Conceptualizing Actors and Practices in the Analysis of Discursive Policymaking.” Policy Studies Journal 45 (3): 510–534. doi:10.1111/psj.12172

- Lovell, H., H. Bulkeley, and S. Owens. 2009. “Converging Agendas? Energy and Climate Change Policies in the UK.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 27 (1): 90–109. doi:10.1068/c0797j

- Moan, K., and H. Hetland. 2012. “Are Leadership Preferences Universally Endorsed or Culturally Contingent?” Scandinavian Journal of Organizational Psychology 4 (1): 5–22.

- Nabers, D. 2011. “Identity and Role Change in International Politics.” In Role Theory in International Relations – Approaches and Analyses, edited by S. Harnisch, F. Cornelia, and H. W. Maull, 74–92. Oxon: Routledge.

- Nasiritousi, N., M. Hjerpe, and K. Buhr. 2014. “Pluralising Climate Change Solutions? Views Held and Voiced Participants at the International Climate Change Negotiations.” Ecological Economics 105: 177–184. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.06.002

- Oels, A. 2005. “Rendering Climate Change Governable: From Biopower to Advanced Liberal Government?” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 7 (3): 185–207. doi:10.1080/15239080500339661

- Okereke, C., and P. Coventry. 2016. “Climate Justice and the International Regime: Before, During, and After Paris.” WIRES Climate Change 7 (6): 834–851. doi:10.1002/wcc.419

- Parker, C., and C. Karlsson. 2010. “Climate Change and the European Union’s Leadership Moment: An Inconvenient Truth?” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 48 (4): 923–943. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02080.x

- Parker, C., and C. Karlsson. 2018. “The UN Climate Change Negotiations and the Role of the United States: Assessing American Leadership from Copenhagen to Paris.” Environmental Politics 27 (3): 519–540. doi:10.1080/09644016.2018.1442388

- Petrone, F. 2019. “BRICS, Soft Power and Climate Change: New Challenges in Global Governance?” Ethics & Global Politics 12 (2): 19–30. doi:10.1080/16544951.2019.1611339

- Prys-Hansen, M. 2020. “Differentiation as Affirmative Action: Transforming or Reinforcing Structural Inequality at the UNFCCC?” Global Society 34 (3): 353–369. doi:10.1080/13600826.2020.1739635

- Qi, J., and P. Dauvergne. 2022. “China’s Rising Influence on Climate Governance: Forging a Path for the Global South.” Global Environmental Change 73: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102484

- Qingzhi, H. 2017. “Criticism of the Logic of the Ecological Imperialism of “Carbon Politics” and Its Transcendence.” Social Sciences in China 38 (2): 76–94. doi:10.1080/02529203.2017.1302234

- Rajão, R., and T. Duarte. 2018. “Performing Postcolonial Identities at the United Nations’ Climate Negotiations.” Postcolonial Studies 21 (3): 364–378. doi:10.1080/13688790.2018.1482597

- Sealey-Huggins, L. 2017. “‘1.5°C to Stay Alive’: Climate Change, Imperialism and Justice for the Caribbean.” Third World Quarterly 38 (11): 2444–2463. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1368013

- Skodvin, T., and S. Andresen. 2006. “Leadership Revisited.” Global Environmental Politics 6 (3): 13–27. doi:10.1162/glep.2006.6.3.13

- Tozer, L., and N. Klenk. 2018. “Discourses of Carbon Neutrality and Imaginaries of Urban Futures.” Energy Research & Social Science 35: 174–181. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.10.017

- Underdal, A. 1994. “Leadership Theory: Rediscovering the Arts of Management.” In International Multilateral Negotiation: Approaches to the Management of Complexity, edited by I. W. Zartman, 178–197. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- UNEP. 2021. “United Nations Environment Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2021: The Heat Is On – A world of climate promises not yet delivered” Accessed October 29, 2021. https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2021.

- Uusi-Rauva, C. 2010. “The EU Energy and Climate Package: A Showcase for European Environmental Leadership?” Environmental Policy and Governance 20: 73–88. doi:10.1002/eet.535

- Vezirgiannidou, S. E. 2015. “The UK and Emerging Countries in the Climate Regime: Whither Leadership?” Global Society 29 (3): 447–462. doi:10.1080/13600826.2015.1017554

- Weinhardt, C. 2020. “Emerging Powers in the World Trading System: Contestation of the Developing Country Status and the Reproduction of Inequalities.” Global Society 34 (3): 388–408. doi:10.1080/13600826.2020.1739632

- Wilkens, J. 2017. Postcolonialism in International Relations. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.101

- Young, O. 1991. “Political Leadership and Regime Formation: On the Development of Institutions in International Society.” International Organization 45 (3): 281–308. doi:10.1017/S0020818300033117

- Zhang, Y., and J. Orbie. 2021. “Strategic Narratives in China’s Climate Policy: Analysing Three Phases in China’s Discourse Coalition.” The Pacific Review 34 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1080/09512748.2019.1637366