ABSTRACT

This paper examines how migrant domestic workers subvert domination, exploitation and subjection through performances in TikTok videos. Through this medium, workers exercise autonomy in severely restrictive employment and living conditions, where collective action may not only be improbable but also illegal. I argue that these videos demonstrate Foucauldian counter-conduct or the “art of not being governed so much”. Counter-conduct is a form of resistance distinct to those who have limited access to the public sphere, due in part to the gendered nature of cooking, cleaning and caring. Domestic work is not normally included in labour laws, and the place of employment are private homes. This makes it difficult to organise or make rights claims. I build on literatures of everyday resistance to examine the practices and subjectivities by migrant domestic workers in Gulf countries. In so doing, so-called “modern slaves”, enact freedom, already present, as subjects of ethics and politics.

Introduction

TikTok videos became wildly popular as a medium at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Many discovered the app as a way to alleviate boredom and virtually live social lives under lockdowns and restriction to public spaces. People filmed themselves dancing and responding to funny memes. Migrant domestic workers were not exempt from this social media trend. In August 2020, the New York Times published a feature of one such worker from Kenya, Brenda Dama. One of her videos garnered nearly one million views, liked over 143 000 times, and has nearly 5000 comments. In the video, she looks at her mobile phone camera directly as text captions and background music tell us what it is like for her to work in Saudi Arabia. The captions that read “Freedom”, and “A single day off” among others, are timed to appear before the background music’s hook – “Don’t got it”. Many of the comments were messages of commiseration and solidarity – wishing prayers and strength, recognition of similar experiences, or simply typing “We are here for you”.

In fact, there are thousands of these videos on the platform. As of writing, videos with the hashtags #kadama and #shagala, both meaning servant or housemaid in Arabic, have over five hundred million views. Arab States comprise the region with the highest percentage of domestic workers as a share of total employment (12 percent). The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that the region employs 6.6 million, most of whom are migrants (83 percent) from Southeast Asia (e.g. the Philippines and Indonesia), South Asia (e.g. India, Nepal and Sri Lanka), and more recently from Africa (e.g. Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia) (ILO Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2022). The biggest destination countries are Saudi Arabia (accounting for over half), the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Qatar. Arab States also have the lowest coverage of social protection for domestic workers compared to other world regions (ILO Citation2022). Worldwide, nearly 94 percent of domestic workers are excluded from the scope of national labour laws and covered only by subordinate regulations which are poorly enforced, if at all. This means that many taken-for-granted employment norms, e.g. the workweek ending on a Friday or regularly receiving wages or salaries, may not always apply to this category of worker. Since they work in private households, it is not difficult to limit their freedom of mobility both in the labour market and even their literal physical access to the public sphere.

In the region’s kafala system, migrant workers’ residency and right to work are tied to a sponsor or the kafeel (usually the employer). It is also normal for the employer to confiscate the worker’s passport and iqama (residence papers) even though this is technically illegal (Fernandez Citation2019, 56). Kafala as a labour migration regime therefore creates a significant power asymmetry between worker and employer, creating severely restrictive living and working conditions in which the former needs the latter’s approval to switch employment and/or leave the country. The gendered nature of domestic work also poses different challenges compared to, say, migrant workers in construction or the service industry. The most crucial difference is that domestic workers reside in their employers’ homes.

In this scenario, this paper looks into why the practice of making TikTok videos has become wildly popular among migrant domestic workers in the Gulf. What do they do on these videos? What do we make of their portrayals, messaging and interactions? I argue that these videos instantiate counter-conduct – “the sense of struggle against processes implemented for conducting others” (Foucault Citation2007a, 201). Counter-conducts are meant to counter subjectivation, or the processes which lead us to believe truths about ourselves. Counter-conduct is reflexive, in which the subject understands that she is being acted upon by others. The goal is to mitigate these effects through ethical practices or askesis – a mastery over oneself. In Foucault’s formulation, freedom is not the end goal or an end state. Neither is it a condition. It is a practice, where counter-conduct is a practice of freedom. They are everyday actions, and in this sense constitute “everyday resistance” (Johansson and Vinthagen Citation2016; Vinthagen and Johansson Citation2013). Counter-conduct is also about “the will not to be governed thusly, like that, by these people, at this price” (Foucault Citation2007b, 75).

I put forward counter-conduct as the appropriate frame with which to understand this phenomenon for three reasons. First, it understands that the subject doing the resisting knowingly does so, and that their targets are local agents in practical settings. Second, counter-conduct also understands that the subject that does the resisting does not come pre-formed. In the concrete steps they take to counter power, migrant domestic workers also transform themselves into subjects capable of “doing politics”, albeit in this informal, everyday sense. In the same vein, they transform themselves from objects of social domination to subjects capable of resistance through recuperation – recouping self-dignity lost due to the low status accorded to domestic work, recouping bodily well-being through physical rest and bodily care, and recouping mental well-being through leisure, humour and play, either by themselves or with others. They resist economic exploitation by avoiding work or surreptitiously taking rest time.

Finally, the paper reflects on the medium of TikTok itself, and what it allows migrant domestic workers to do. As an in-between space, the platform calls on the public to witness what would otherwise be hidden in the private domain of the household. It is here where the “hidden transcript” is produced, performed and circulated among the habitués of #shagalalife - a repository of jokes, gripes, moods and practices that “only shagala would know”. This is a site in which they practice “a politics of disguise and anonymity that takes place in public view but is designed to have a double meaning” (Scott Citation1990, 18). It is a kind of politics practiced by a liminal economic subject – not quite worker, not quite family member, not quite “slave”. Where “major politics” courses through parliaments, bureaucracies, political parties, and is premised on a “people” and their representation, “minor politics” is about a “people to come” (Deleuze Citation1989, 216). There is, as yet, no collective identity from which to draw meaning and political agency. The focus, rather, is on their creativity, premised on the lack of resources, and which emerge out of “cramped” spaces. This is a politics that is no longer “a process of facilitating and bolstering identity, or ‘becoming-conscious’, but […] a process of innovation, of experimentation … ” (Thoburn Citation2003, 8).

In their creation of TikTok videos, domestic workers co-produce a counter-culture from which they may present and draw meanings about themselves, and practical know-how to survive the hard circumstances of living and working under kafala. With these videos, they draw an audience, and co-create an intimate yet physically dispersed community. Without the possibility of unionising, or even getting access to the public sphere, creating these videos embodies counter-conduct. This research does not mean to trace change from state A to state B, or to identify causal mechanisms. It may very well be that some of these workers augment their digital worlds with off-line activities if they have the freedom to do so. In this instance, proof of resistance is in the very practice of creating these videos.

I coded two hundred and fifty TikTok videos dating from 2021 to 2022, using primarily search terms #shagala and #kadama in combination with geographic places – e.g. Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Doha, Kuwait and Dubai. Most of the text and voice in these videos were in Filipino and/or English. There are some videos with text and/or voice in Indonesian Bahasa and Swahili. For these, I used Google Translate to translate text captions. The videos were selected from public profiles – these uploads are viewable to the general public without having to download the app or sign up to TikTok’s desktop version. These videos may be assumed to be public as users include hashtags in order to be found, observed by, and to engage with, strangers. Arguably for most of these workers, these videos augment their very limited access to the public sphere. For others, it may be their only access. Videos were selected from dozens of different users. The selection process itself is random. I coded whatever TikTok’s algorithm would show as search results after the hashtags #shagala or #kadama and the geographic regions. I myself have not interacted with any of the users. To protect the anonymity of users, their handle or usernames are not included, and there are no identifiers other than they are located in the Arabian Gulf. The workers who have been mentioned in the vignettes below are pseudonymized.Footnote1

This research is informed by a rethinking of the internet and our digital devices as spaces and tools whose technics allow for new modes of sociality and subject-formation (Light, Burgess, and Duguay Citation2018; Ritter Citation2021). These new ways of doing and being are a result of actors’ actions rather than their causes. For example, the use of hashtags not only allows the user’s video to be found, but is also a claim to a community and a belonging to that community. The socio-technics of social media has allowed for an unprecedented “hyper-reflexivity” (Caliandro Citation2018, 20), in which we are acutely aware that we are acting in front of an audience, both seen and unseen. What results is a more-than-human “hybrid” that exceeds the value capture of “communicative capitalism” (Dean Citation2005) and firmly instantiates the “positive becoming of the virtual as a method of induction and reproduction” (Greaves Citation2015, 206).

Everyday resistance and hidden transcripts

Various scholars have characterised domestic workers’ resistance in terms of peasant anthropologist James Scott’s hidden transcripts (Chin Citation1998; Constable Citation2007; Moukrabel Citation2009; Pande Citation2012; Tondo Citation2014), in part because their living and working conditions match what Scott calls an “infrapolitics of the powerless” (Scott Citation1990). This is the practice of politics in the presence of overwhelming domination and subordination as in slavery, serfdom or within the caste system. It consists of performing on two “stages” and participating in public and hidden transcripts. Public transcripts are hegemonic – taken-for-granted beliefs of dominant elites that reinforce their self-image and self-understanding (Scott Citation1990, 18). The public transcript is “the open interaction between subordinates and those who dominate” (Scott Citation1990, 2). Hidden transcripts are practiced “off-stage”, away from the gaze of powerholders. While public transcripts are for everyone to see, hidden transcripts are produced for a different audience. They may comprise rumours, jokes and discourse that would otherwise invite backlash, if not outright physical violence, from dominant groups if uttered in public. “At its most elementary level, the hidden transcript represents an acting out in fantasy – and occasionally in secretive practice – of the anger and reciprocal aggression denied by the presence of domination” (Scott Citation1990, 38). This is Scott’s intervention in Marxian and Gramscian theories of false consciousness and hegemony. Subordinate groups are not dupes, and their compliance does not always mean consent.

There are real costs to openly subverting public transcripts. Where laws exist but are poorly enforced, the cost of workers insisting on legal entitlements may mean becoming less attractive in the labour market. For example, in Singapore, a weekly rest day for domestic workers has been mandated since 2012, but less than half avail of the entitlement. What explains this phenomenon? Where the public transcript means performing “agentic submission” (Schumann and Paul Citation2021), that is, complying with the tacit wishes of employers that the worker continues working on weekends, forgoing rest days may indeed incur short-term suffering but accrue gains in long-term economic goals. That is, the logic that motivates forgoing rest does not only mean signalling to current or future employers that one will not disturb the public transcript, or that one is more attractive to labour markets by being permanently exploitable, but that one is exercising one’s economic reason. After all, being less attractive to employers, or worse, being unemployed, is illogical.

It is precisely this limit to one’s self-understanding as well as the limits to one’s imagined possible actions to which counter-conduct responds. Foucauldian counter-conduct straddles both the internal (intentional, consciousness) and practice-oriented (non-reflective) aspects of resistance. I follow Arnold Davidson’s argument that counter-conduct links the ethical to the political, and in which ethics (or askesis) “is an activity that transforms one’s relation to oneself and to others” (Davidson Citation2011, 32). The goal of counter-conduct is to modify force relations - that is, to elicit an opposite and novel reaction in the other party, possibly opening a rupture in otherwise sedimented (i.e. institutionalised) forms of power (Davidson Citation2011, 28–29). Counter-conduct recognises that dominant representations (ideology, public transcripts) work to direct both our understandings (mentalities) and concrete behaviours. As such, resistance must work at both registers. Failure to do so would result in the case described by Schumann and Paul (Citation2021), in which the short-term compliance with economic exploitation (i.e. forgoing rest days), in order to maintain future access to labour markets (i.e. future exploitation), is the only pragmatic and obvious option.

The inability to think and therefore act otherwise is at the very heart of askesis and Foucauldian counter-conduct. This relates to Foucault’s graduated understanding of power and its various techniques – from sovereignty’s power to prohibit (i.e. the state’s legal system’s ability to shape action via prohibition or illegality), to governmentality being able to shape action through the exercise of freedom by the neoliberal subject or the means-ends calculating homo economicus (Foucault Citation2008, 252). Interestingly, the kind of short-term compliance described by Schumann and Paul may be harmful in the sense that it further disempowers workers. It may induce a sense of “low self-efficacy” or the feeling of not having accomplished or failed at something, and just the general lack of “mastery experiences” (Ellerman Citation2017, 193). This would then make it more difficult to put up resistance of any kind, at the present or in the future.

Open contestation, i.e. the outright disruption of a public transcript, may be linked to association with a union (Barua, Haukanes, and Waldrop Citation2016, 18). Where the protection of a collective is not possible due to limits posed by citizenship and legal systems, everyday resistance must be subtle, discreet and strategic. The target “audience” of hidden transcripts are almost always other domestic workers. Where they are allowed, and do take days off, the safety of weekend enclaves or churches allow informal communities to form. In some sense, these communities even take on the form and function of a union, informal networks where older members pass on important information to newcomers or give advice (Pande Citation2014, 41). The exclusion of domestic work from labour laws as well as foreigner status of course limit what these collectives can accomplish. And identity differences make it difficult to organise across nationalities (Kayoko Citation2009, 509). Where forming trade unions is prohibited, spiritual communities (churches) allow for mechanisms of collective agency and practical support. For the individual, religion helps women “construct and maintain internal discourses of dignity and self-worth” (Fernandez Citation2014, 70). In these communities, workers alleviate stress, find comfort and a sense of belonging “by sharing their ordeals, dreams for the future, and food with one another” (Liebelt Citation2014, 97).

Amrita Pande calls “meso-level of resistances” the actions that cannot be easily categorised as either private/individual or collective. These typically occur between two, or among a few, workers and form a middle ground on which more organised forms of resistance may be built. As with the above, they take place on balconies, in religious meetings and weekend enclaves, where workers share information on contracts, salary, and ways to negotiate with employers for more freedom and leisure time (Pande Citation2012). They are “meso-level” as they straddle the space between micro-politics and macro-politics, as Scott’s infrapolitics (Pande Citation2012, 299).

Different dynamics play out when the private domain of the household becomes the site in which a specific kind of class conflict takes place. As Bridget Anderson argues, the employer is not buying the worker’s labour power but the “power to command” – limited only by the employment contract. The fiction in Marxist theory is that labour power can be sold as a commodity, separate from one’s personhood. The two combined is nothing but slavery after all. But this fiction is useful to distinguish what aspects of oneself one can sell and which ones cannot be sold. On the one hand, the domestic worker is attempting to sell her labour power, and on the other, the employer is attempting to acquire a particular kind of person (Anderson Citation2000, 113–114). This person does not simply perform household tasks, but whose very personhood serves as a marker of class, racial, gender and other social distinctions.

The maintenance of these distinctions prompts both employers and workers to do “boundary work” (Lan Citation2003), which produce and reproduce divides that distinguish private space and identity categories. Hierarchies of distinction manifest in various ways – notably in access to space within the home, where domestic workers get to sleep – if they get their own rooms, or if they must share quarters with others, e.g. with the infant, child or the elderly they care for. There are distinctions in mannerisms, mode of dress and in how one speaks. There is also boundary policing on who gets to eat what, when and how much (Lan Citation2003, 539). Workers are enjoined to play down their femininity, for example by having short hair, not wearing make-up and wearing a uniform (Chee Citation2020, 372). To maintain status asymmetries, workers must bear various indignities, and as such should not be too choosy and not have too much “pride” (Chee Citation2020, 371). Slights or jokes made at their expense are a type of, “subtle subordination” – “to inform workers who their employers think they should be and how they should act (Ellerman Citation2017, 201)”, that is, to put them in their place.

To counter the effects of everyday humiliations, workers valorise the nature of domestic work itself, and repair the damage caused by employers or society (Barua, Haukanes, and Waldrop Citation2016, 8). Jokes function to “symbolically reverse the roles of the employer and domestic worker” (Constable Citation2007, 174). Where they have an opportunity to gossip, they may criticise employers’ material excesses in festivities, for example during Eid, and bolster their moral superiority by comparing this to their own more modest celebrations (Elyas and Johnson Citation2014, 154). In response to verbal insults, simply stating “Tao ako!” (I am human!), (Lindio-McGovern Citation2010, 199) can be resistance.

Of course the final and ultimate “weapon of the weak” is “the power to exit” – when workers run away from the household (Fernandez Citation2014, 69). Running away is often the last resort when living and employment conditions become too much to bear. However in doing so they become undocumented, even though they have more freedom to be “freelancers”, i.e. day cleaners in households and employers of their choosing (Fernandez Citation2019, 134). Working for different employers distributes risk and gives them more options. More experienced migrants, those who have already served one or two contracts and are on a new deployment, may plan to run away at the first opportunity in order to have the flexibility of not being tied to a kafeel. Since it is a repeat deployment, these workers may already speak the language, and have informal networks on which to rely to find irregular employment (Fernandez Citation2019, 68–69).

The public transcript reflects the dominant understanding of reality, in which dominant groups play at mastery and subordinate groups play at subservience (Scott Citation1990, 87). As mentioned previously, the capacity to challenge the public script diminishes the more one performs compliance. The example of Su in Ellerman’s study is particularly poignant. Where she initially felt angry that she did not eat the same food as her employers, over the years she came to accept the need to economise and that her employers’ having savings means she eats cheaper or less (Ellerman Citation2017, 203). As such, enduring, adapting, and indeed being “resilient” (Chee Citation2020) becomes a virtue rather than merely a mode of survival.

The ability to contest the public transcript relies on the type of consciousness in which the worker has the ability to recognise “how or to what degree they adopt the perspectives of the dominant, how they are made to comply, and how subordination shapes their attitudes, perspectives and behaviour” (Ellerman Citation2017, 202). This means the worker firstly recognises means and ways of subordination, and then is able to reflect on the degree to which the worker has internalised the identities and attendant indignities imposed on her. Ellerman claims this second stage is more difficult to accomplish.

To counter the “reality” in which they are inferior, powerless, promiscuous, etc., domestic workers turn to artistic self-expression to reimagine their lives otherwise. Workers in Singapore participate in beauty contests and spend their days off dressing up, making themselves beautiful. Roces argues they use “fashion as resistance and as a rite of passage that marks their new identities” (Roces Citation2022, 131). Just like beauty queens in the Philippines, these pageants confer social status that is lost. Similarly, art classes organised by a domestic worker collective in London were not only outlets of self-expression but also a safe space to produce communal knowledge and solidarity. Participating in such artistic endeavours had a capacitating effect, in which reflection upon shared experiences and struggles made workers feel confident and agentic (Jiang and Korczynski Citation2019).

Vinthagen and Johansson expand on Scott’s notion of everyday resistance which focuses on acts rather than (political) consciousness. They argue that there is no intention or “consciousness” in the actor, nor is there need of recognition by the targets of resistance for us to detect everyday resistance. What is important is the action itself, its agency. There is no need for the vision and execution of some grand plan, let alone an envisioned result. It may simply be to survive or respond to a very micro, practical problem. What is important is “the potential of undermining power” (Vinthagen and Johansson Citation2013, 18). They then argue to focus on creativity – the “art of resistance” rather than “properties of consciousness” (Vinthagen and Johansson Citation2013, 22). Similar to the Foucauldian formulation of counter-conduct, they see that resistance does not originate from within the subject, but “arises in combination of subjectivity, context and interaction” (Vinthagen and Johansson Citation2013, 36). Later they would elaborate on their conceptualisation by adding temporal and spatial elements. Like Scott (Scott Citation1990, 114), they see the importance of a “third space” in which a counter-hegemonic or counter-culture practices and discourses may flourish. In this space, the worker has the opportunity to steal back the time appropriated from her labour, where she is not a unit of productivity, and rather redirects her efforts in free and creative pursuits (Johansson and Vinthagen Citation2016).

In sum, the literature has examined everyday resistance practiced by domestic workers in the “meso level”, between public and private spaces. Hidden transcripts may be co-produced and circulated by subordinate groups in these spaces. Even if they do not openly contest the hegemony of dominant groups, hidden transcripts are at least a source of alternate codes, identities and imaginaries from which subordinate groups may draw, and with which to reimagine reality differently. Everyday resistance which focuses on situated acts rather than intentions premised on class consciousness shift the analytic focus to pragmatic, everyday actions to alleviate, if not counter, immediate acts of exploitation and domination. The introduction of Foucauldian subjectivity or “mentalities” in everyday resistance makes practical, embodied and local what would otherwise be distant, abstract and transcendental. This is especially the case for workers who are living and working in isolation, and who may not always have direct access to the public sphere. For this case, I suggest that the practice of making TikTok videos works on multiple registers – not only as a means by which migrant domestic workers co-produce a counter-hegemonic culture – but also as a practice of counter-conduct.

Counter-conduct

Foucault’s genealogies reconceptualise power, first as a relation, and second as productive. These two allow for the move to think of power as neither good nor bad, but as a “game” in which one tries to conduct the conduct of another. Foucault’s re-conception of power as relational rather than a substance that one possesses has allowed him to shift the analytic focus to “strategies” or “tactics” rather than describing what kinds of agents possess power and how they wield “it” (Foucault Citation1978, 94–95). “Resistance” then are techniques to counter power, and are purposive actions taken in local contexts. This conception is intrinsic in Foucault’s thinking about power as relations which emanate from all facets of society as potentialities and become frozen or solidify in institutions, groups or norms (Dreyfus and Rabinow Citation1982, 197). Resistance is the possibility for these relations to be reversed in a “strategic games between liberties” (Fornet-Betancourt et al. Citation1987, 130) rather than states of absolute control or domination where one has no room for manoeuvre. This possibility to resist is what constitutes power relations (Foucault Citation1980, 142). The condition of absolute domination or total power is only possible in slavery (Foucault Citation2013, 292).

Foucault disputes the so-called “repressive hypothesis” by claiming power does not only prohibit but also enables (Foucault Citation1982). While it may repress or conceal reality, it can also produce it – “it produces domain of objects and rituals of truth” (Foucault Citation1977, 194). In Foucault’s genealogies he describes three ways by which someone becomes a “subject” – (1) through the knowledge production of the human sciences, (2) individualising processes that create categories (sane/insane, good/bad) and (3) askesis – how individuals turn themselves into subjects. As such, the move from power as negative (prohibition/law) to productive (capacitating) allows for the possibility that becoming a “subject” does not only entail subjection but also resistance.

Counter-conduct is resistance to power brought to bear on a subject and is related to what Foucault calls “three types of struggles” – against domination, against exploitation and finally against subjection. Examples of these three working in isolation or in combination with each other can be found throughout history (Foucault Citation1982, 781–782). Revolts of conduct are different from resistance against sovereignty (or political power) and against exploitation (or economic power). At this micro-level, resistance might comprise technologies of the self to carve a space of autonomy that is as free from the influence of power as possible. Foucault’s thinking on resistance is premised on his claim that there is no “human nature” fully formed and thus there is no pre-existing absolutely free human that will do the resisting. This subject is formed within power relations and will consequently resist from, within and against the same. It is not simply a negation or a reaction but is productive (Davidson Citation2011, 28), in the sense that it creates or fashions a new subjectivity, a new self.

Foucauldian counter-conduct has been mobilised by IR scholars primarily in the context of public protests, e.g. in Occupy movements (Rossdale and Stierl Citation2016; Nişancıoğlu and Pal Citation2016), in development summit protests (Death Citation2010, Citation2011), in Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement (Barrett Citation2020), in London Riots (Sokhi-Bulley Citation2016), among others. These studies are interested in the formation of identities and subjectivities which resulted from collective action, as well as concrete practices and techniques employed in specific contexts. “Fields of visibility” (Death Citation2010, 242) seek to counter or disrupt dominant modes and scopes of vision. “Creative visual counter-conducts” (Malmvig Citation2016) mobilise visual materials to problematise and reconfigure power relations. Counter-conducts create new knowledges and new mentalities (Death Citation2011, 429). They are not always directed at the state (the “chief enemy”) but to other “governors” in the plural. They may thus be practiced in seemingly apolitical settings (Odysseos, Death, and Malmvig Citation2016, 3). As with Foucault’s original formulation, counter-conduct as a form of resistance is understood to exist in a continuum with techniques of power. “Where there is power, there is resistance, and yet, or rather consequently, this resistance is never in a position of exteriority in relation to power” (Foucault Citation1978, 95). Counter-conducts are “wholly immanent and necessary to the formation and development of governmentality” (Cadman Citation2010, 540). In Malmvig’s investigation of Arab states’ resistance to Europe’s democracy promotion, counter-conduct is not overtly political, vocal or even emancipatory (Malmvig Citation2014). There is no “end point” or an outside of power, and as such one can never reach a space where one is emancipated from relations of power.

Counter-conduct makes it possible to resist without first possessing a consciousness. It makes it possible to resist without first being a certain kind of subject or identity. To raise a hand when one is about to get slapped has no other meaning than to avoid pain. Counter-conduct also allows for the possibility that these micro-actions, of habitually avoiding getting slapped for example, produces a subjectivity. That is, that these practices capacitate one as a subject, an actor, a person who has the will and ability to counter power in this specific way. This transformation is premised on the relation of the self to itself – a relation that is ethical and therefore political (Davidson Citation2011, 29). This is a relation that is founded on a discovery of truths about oneself that is impossible if one’s behaviour were pegged to the rationality of the domestic workers in Schumann and Paul’s study – the means-ends calculating homo economicus. Where the logical option is to forgo rest days, resisting the self’s own thinking and consequent behaviour means to make the irrational choice of taking the day off.

Lastly, counter-conduct makes it possible to resist without the formal organisation of social movements. This is especially pertinent to the phenomenon under study, in which participants and co-creators of #shagalife are dispersed, and who only meet and momentarily share virtual space through hashtags on the platform.

Laughter, levity and role-play

I return to the initial puzzle that has motivated this paper – what exactly are these women doing in front of their mobile phone cameras? What prompts them to put together sometimes elaborate theatrical performances in video clips that often last no longer than ninety seconds?

The dominant “mood” of these TikTok videos denote humour, fun and play. They depict workers in the middle of performing their daily tasks – cleaning, vacuuming, yard work, ironing, washing dishes and doing the laundry. There is almost always lively music, smiling emojis and a laugh track overlaying the action taking place. The background music employed might be songs that originate from American or European pop artists, but they may also be songs from workers’ origin countries. The most common emotions show workers laughing, being silly, being joyful. In combination with smiling, laughing or laugh-crying emojis, it is clear that the audience is supposed to laugh along and have fun.

Humour lightens the heart and may even seem frivolous compared to politics – an activity that is thought of as weighty and consequential (Kutz-Flamenbaum Citation2014). It is this duality to which author and stand-up comic Kate Fox attributes her concept “humitas” – a play on two words; humour and gravitas (Fox Citation2018). The idea is that humorous discourse is not simply bracketed off as “play” but may actually have real-world consequence, that “humour can make things happen (Wilkie Citation2017, 220)”. Fox also refers to the practitioner of humitas as a kind of parrhesiast who, by expressing the feelings of an audience, creates a fusion with them in the performance. The successful melding of levity and gravity in comedic performances are “visible counter-conduct” which reject current modes of political discourse (Fox Citation2018, 90–91). Parrhesia is the practice of speaking freely where there is consequence to the speaker, where it “opens up an unspecified risk” (Foucault Citation2010, 62). This risk includes possibly alienating the audience, those who listen to the speech activity. Foucault contrasts parrhesia from rhetoric where the speaker takes no risk. She can say what she does not believe. In parrhesia, there is a close and necessary bond between the speaker and what she says (Foucault Citation2011, 13).

Chris Kramer likewise expands on Foucault’s parrhesia by arguing that the latter has overlooked its humorous element. It may not be useful for the “play” between the parrhesiastic humourist and her audience to be agonistic as this will lead to rupture rather than “a change to a different register” (Kramer Citation2020, 36) . That is, truths are probably very difficult to swallow as a bitter pill. Kramer offers the example of 19th century American abolitionist and former slave Frederik Douglass as one who has managed to combine “the fury and the funny” allowing him to “control the rage, while not stifling it” (Kramer Citation2020, 37). Much like the stand-up comic of today, Douglass’ use of humour functioned as social commentary, but delivered with irony, mockery or sarcasm. Humour could accomplish what reason or argumentation could not – cultivating at least an openness to be convinced or persuaded through play, where laughter “allow[s] us to manipulate otherwise abstract logical or moral states of affairs [and] render concrete the lived experience of others” (Kramer Citation2020, 28).

The relationship which the humorous parrhesiast attempts to cultivate among her interlocutors, her audience, is one premised on implicit solidarity – to laugh at the joke means one gets the joke. One understands the context and the intention of the joke-teller. As such, humour creates in-groups and out-groups – between those who find something funny and those who do not. It therefore creates identities based on shared experiences, or at least an understanding of what those experiences are and what they entail (Adler-Nissen and Tsinovoi Citation2018, 9; Chernobrov Citation2022, 282; Downe Citation1999, 72; Kutz-Flamenbaum Citation2014, 300; Smith Citation2009, 160). When those in the audience fail to laugh, it is not because they have no sense of humour. It may simply be that they do not possess the means necessary to get the joke. When I showed a video of two migrant domestic workers dancing to peers at a workshop recently, they looked at me with puzzlement as I smiled in amusement. Clearly, I am in the in-group and they are not.

After daily tasks, the second most common activity portrayed in videos is workers dancing. They do so in what looks to be their own private rooms, in the living room, in the kitchen, during what appears to be leisure time, in the middle of a task, alone or with other domestic workers (colleagues) in the household. There is only one video showing a worker dancing with her care recipients – two toddlers. Where dancing is purely about having fun, workers mix portrayals with humorous choreography or situations. For example, one video shows two workers in the living room - both wearing what appears to be plastic bags fashioned as underwear worn outside their uniforms. One has removed her right slipper and has put it on her arm. She wears what appears to be sunglasses, with one of the lenses missing. Both are dancing in sync to Michael Jackson’s “Billy Jean” with silly moves and facial expressions that are clearly meant to elicit laughter from the viewer. They knowingly gaze into the camera as we, the audience, chuckle to the comic track. Here, in these precious few seconds, we, the audience, share this moment of levity, both together and apart as allowed by the socio-technics of the platform .

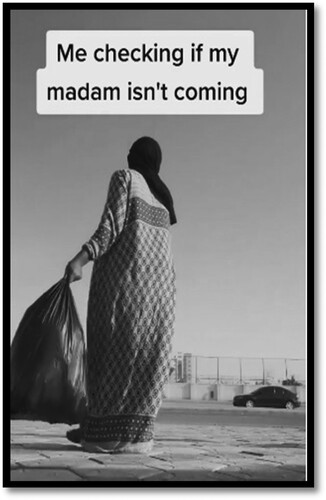

The videos which show workers in the middle of performing a task are either lively, sombre or show full contradiction. The first two are unambiguous and are meant to communicate either happiness or sadness. The lively videos are accompanied by upbeat music and sometimes dancing (choreographed, improvised or in a silly manner). There are also in-jokes. For example, one worker who appears to be outside the household to take out the trash, gazes off at the distance with the caption “Me checking if my madam isn’t coming”. It appears the mobile phone is placed close to the ground as vehicles pass by in the background. The laugh track is meant to communicate that we are supposed to find this funny .

Other shagalas or kadamas might know why, but the uninitiated will probably need more context. The “Madam”, or the female employer, is really the only figure of authority to which workers most frequently gesture. In this video the worker is anticipating whether her employer is about to arrive, interrupting either her daily task, her momentary access to the outside (freedom), or both. Another lively video shows a worker bathing a dog in the bathtub. The caption reads “God bless the work of my hands”, as “Wendi” by Ugandan musician Bobi Wine, blazes in the background. While she appears quite content with her task, some commenters admonish her for bathing an animal (this being outside the scope of her duties), while others helpfully suggest she use gloves. There are also words of encouragement, even though the video does not seem to solicit this. “Be strong dear”, “Hard working pays, be strong dia (love)”, “It’s ok sweet, we need money”, “Keep on until you get what you want dear God sees you through”.

The straight-forward sombre videos usually have a sad background music track, or no music at all. Two videos feature a voice clip with a sad music overlay, perhaps something that is taken from a movie, TV series or radio show:

Ako’y OFW sa bansang Arabo. Nakikipagsapalaran para sa pamilya ko. Hirap at pagod ay aking dinanas. Lahat ay kinaya para sa pamilyang nasa Pilipinas". (I am an Overseas Filipino Worker in an Arab country. Taking chances for my family. I have experienced hardship and exhaustion. I have overcome it all for my family in the Philippines).

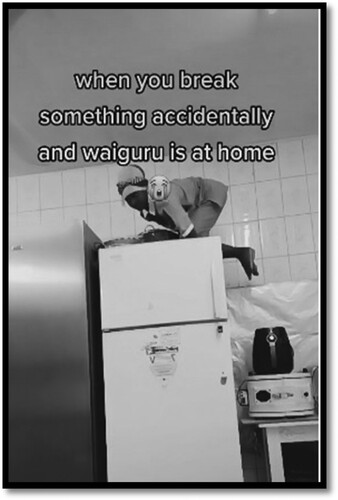

The videos that show contradiction combine two or more contrasting elements. The emotions elicited from viewers are a mix of levity, concern, sadness, even anger. Videos that feature Madam are almost always overlaid with a laugh track and lively music. One video features a worker with a big smile, looking directly into the camera, and mouthing the lyrics of Post Malone’s “Congratulations” - “Patient, oh I was patient. Now I can scream that we made it”. The caption reads “When Madam finally give[s] me a day off in a week … ” Another video is sped up a bit, similar to those early black and white Charlie Chaplin movies. The worker enters from left-of-screen carrying a big bowl, and then immediately falls to the ground as the laugh track kicks in. The caption reads “when you break something accidentally and waiguru (boss) is at home”. She gets up, surveys the broken dish on the ground and then quickly scrambles up the sink to get to the top of the refrigerator next to it. She secures her crouching position, and gives the camera a quick look before the video ends .

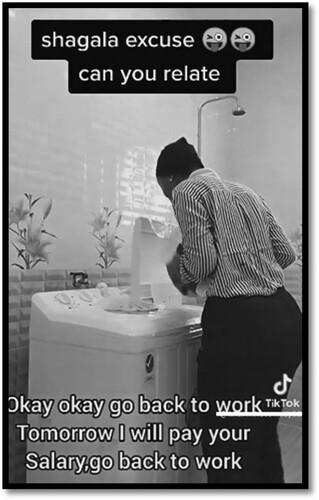

A more elaborate portrayal involves a dialogue exchange between a worker in the middle of doing the laundry and her “Madam” just off-screen. It is clear that she is using her own spoken voice for these two “roles”, instead of a movie audio clip. The exchange goes:

Kemi!!!

Yes

How’s your family doing in Nigeria?

No madam (funny sound effect)

Is your mother doing good?

She’s not doing good madam (alarm sound effect, laugh track kicks in)

Is your baby doing good?

All of them are not doing good

Why all are not good?

They’re in need of money

Okay, okay, go back to work. Tomorrow I will pay your salary. Go back to work

Most of the videos that reference labour exploitation – for example having no sleep or rest, always being available or on call, working after midnight and physical exhaustion – are portrayed tongue-in-cheek, and have a sarcastic or ironic tone. Videos that show a response to these include workers pretending to clean the toilet but are in fact taking the opportunity to rest. In another role-play, a worker tells her “Madam” (off-screen) calling her after midnight - “I’m tired”. Her speaking voice is distorted for comedic or theatrical effect. In fact, very rarely do the videos use workers’ actual speaking voice. In the instances that they do, the videos have a serious tone, often to give practical advice, to issue a warning and address the audience directly without the ruse of a joke, mockery or role-play.

The sixty or ninety seconds of temporary levity are not only to share a laugh or make light of shared common experiences and hardships, but work to recoup what is depleted – mental, emotional and physical resources. The videos also directly produce not only alternative “fields of visibility” (Death Citation2010, 242) – showing us scenes, happenings, and emotions which transpire in the hidden abode of the household, but workers’ own account of their reality. They are authors and authorities of these stories, in which they tell us, the audience, how to feel about what we are being asked to witness. Contrary to public transcripts in which domestic workers are victims of super-exploitation, trafficking, physical and psychological abuse, and sometimes violent deaths, these videos never ask us to feel pity. As we bear witness to what are objectively very difficult living and working conditions of migrant domestic workers under kafala, we are asked, first and foremost, to laugh.

The act of creating a video in itself is time spent on creativity and leisure, a way for workers to do something other than being available to the demands of the household they serve. The content of these videos portray a hidden transcript in which the workers poke fun at their employers, demonstrate techniques to refuse labour expropriation or make light of the their daily hardships, which not only produce a different reality, but also only ever depict a protagonist – one who is at least capable of telling stories to each other about themselves.

These videos may certainly be seen as “the carnivalesque”, functioning as a “safety-valve” while reinforcing authoritarian bonds (Dentith Citation1995, 71). But the critique that these momentarily dissipate tensions does not preclude the possibility of domestic workers doing conventional politics if there were the possibility to do so, as the literature demonstrates (Cherubini, Geymonat, and Marchetti Citation2018; Pape Citation2016). The puzzle is to try to understand what these videos are for. Principally, the paper argues that the creation of these videos in itself is a practice of counter-conduct – notably at its most intense – the freedom of the worker to do what she wills with her time, that is, what distinguishes work from slavery. The fact that these videos exist delimits the hours in which the worker renders labour or standby time – for the “use” of the household. To reiterate, the creation of this counter-culture is clearly not meant to supplant broad structural changes that may be achieved with conventional politics.

Commiseration, audience and community

“To make light” of the situations described above means making the burden bearable, in part because they are seen countless times on the platform, in which the target audience - other shagalas and kadamas – respond with affirmative comments, commiserate and even make response videos. This shared vision creates a sense of community in which “only shagala can understand”. The videos which explicitly state this latter expression refer to the challenge of servicing a household during Ramadan, the pressure of being a breadwinner and providing for the family left behind, going to the toilet to rest, having to sneak or squirrel food away, the stress of being always on-call to employers, how making TikTok videos relieves stress, and taking an Arabic language test. Other videos directly ask viewers whether they can “relate”, a rhetorical question which invites the viewers to see themselves in a similar situation. “Only shagala can understand” or whether they can “relate” serve to forge a common identity, as the expressions, and their various referents, become “memefied”, taken up and passed along .

The videos have different levels of audience engagement. They may directly address the viewers – to give advice on how to deal with employers, eating well to stay healthy and how to maintain an optimistic mindset. Some would film themselves without looking at the camera, while others would look at the phone, perhaps to check if they are filming correctly. There is an explicit understanding that there is an audience watching. There are videos directly addressing the audience that simply share feelings or thoughts. There are a few videos in which workers turn on their phone camera, hit record, and then cry.

There is one that explicitly asks the audience for their opinion on a situation. This is a worker from Kenya who is wondering why Filipinos “do not want to go home”, and commenters offer their own thoughts – they have big families and responsibilities, they send all their money back home, they are probably poorer than Kenyans. One commenter said they knew a Filipino who has been in the region for 27 years. The migration corridor from the Philippines and the Gulf has of course been a permanent feature of the region’s development since the late 1970s (Ling Citation1984). Employment contracts for migrant domestic workers typically have a duration of only two years. And there is a common discourse, usually from recruitment and employment agencies who deploy these workers abroad, that this type of migration should only be temporary - a stop-gap measure for workers who may find themselves in economic distress to earn a quick buck (Findlay et al. Citation2013; Rahman Citation2012; Samantroy Citation2014). The reality, however, is that migrant domestic workers get stuck in a cycle of deployment-return-redeployment, because they are trapped in debt, financial burdens and responsibilities increase, and where policies in both sending and receiving countries actually structure this phenomenon to make a pool of flexible labour permanently available (Parreñas et al. Citation2019). So indeed, Filipinos “have not gone home” and this Kenyan is probably wondering what the future holds for her, her co-nationals, and indeed their own country.

As mentioned previously, these videos where workers look directly at the camera and are addressing their audience usually use the worker’s own spoken voice instead of a modified one (for comedic effect) or a plug-in audio clip from a dialogue in a movie or TV show. They tend to be giving advice and practical tips on contract-related issues, romantic relationships, well-being (e.g. eating well, how to feel well), and to look out for employment-related risks - e.g. how to detect a camera that employers may have surreptitiously installed for surveillance, and intentionally planting money in clothes to “tempt” the worker to commit theft (which would result to automatic dismissal and repatriation). Many are also about giving encouragement, and to remember that domestic work is a decent way to make a living and to provide for one’s family. From an Indonesian: “Hard workers don’t get tired for rupiah and why sweat is salty because there is nothing sweet about struggle. Keep up the spirit for all of us, may our tiredness be a blessing, amen”. From a Ugandan:

“To all kadamas who got famous on this site, many people criticize what we post, what we put on and how we live our lives. They say maalo we are villagers. Trying to put us down. But no matter what, we run this app”. Being proud of one’s job and living a dignified life, as well as the memefied expression “proud kadama” are fairly common across nationalities. They counter the discourses about the low status of domestic work, these women’s place in a racialised hierarchy, and boundary work that create and reinforce class distinctions.

The constant repetition of this hidden transcript on the platform, shared and circulated by both those who recognise themselves as being part of the kadama community and the general public, serve to remind everyone that domestic work is decent work. And while these videos do not speak the language of “rights”, are not making rights claims or even be recognisably political, they are irreverent and test boundaries. It is a kind of politics that is “no more or less than that which is born with resistance to governmentality, the first uprising, the first confrontation” (Foucault Citation2007a). Solidarity is built among those in-the-know, those who get the jokes. It is nourished by those who laugh at themselves or jointly laugh at a common target, most often Madam. When laughter is shared in this way, it is easier to transgress boundaries, to “flout the norms of serious discourse” (Smith Citation2009, 160). In the minor politics of these cramped spaces, the habitués of #shagalalife have managed to craft windows into which we are invited to witness them transform themselves and each other, and perhaps even for us the audience to share their vision.

Conclusion: TikTok as “third space”

Many migrant domestic workers, especially those residing in the Gulf, spend most of their waking hours in the confines of the private domain of the household. Where the regular employee is happy to retreat to the privacy of her home on weekends, the lucky domestic worker who has days off spends the weekend in public spaces for leisure and to meet friends. For the most part, those who are allowed to hold on to their mobile phones in their employers’ homes use social media to access the outside world.

In Hong Kong’s more liberal regime (in 2014), Facebook was the main vehicle to mobilise advocacy groups following the torture and abuse of Indonesian Erwiana Sulistyaningsih (Allmark and Wahyudi Citation2016). Filipinos have also turned to social media for online peer support – both emotional and practical (Cheng and Vicera Citation2022). Fellow migrants who pass away are mourned “digitally” on Facebook in Israel (Babis Citation2021). Domestic workers in Singapore use social media to maintain family ties back home and make new friends in their host country (Malik and Kadir Citation2011; Mintarsih Citation2019). The case of migrant construction workers in Singapore demonstrates how TikTok became a vehicle through which workers showed their increased precarity and surveillance during the Covid pandemic (Kaur-Gill Citation2022). In some cases, livestreaming on Facebook as a cry for help can literally save a worker’s life (The New Arab Staff Citation2021). In other words, social media and access to the internet has become an important space in which migrant workers live their multi-spatial, multi-temporal lives.

Migrant domestic workers’ liminal breach of the public/private divide is conditioned by their liminal, conditional access to the public sphere – in both literal and metaphorical senses. Some of the reasons why this type of work is so little regulated and is held separate or different from other parts of the economy is founded on the separation the public – the space of masculine labours of productivity, and the private – the space of feminine labours of reproduction (Chinkin Citation1999; Gal Citation2002; Landes Citation2003). While the public/private divide has long been a feminist point of inquiry, in neoliberal times the nature of the divide has mutated in a way well-described by Robin Goodman: “the private has become a substitution for the public and the state, no longer just a barrier to the state and public life defined through domestic women’s work (Goodman Citation2010, 2)”. In a paradoxical way, while women have crossed over to fill traditionally masculine roles in the so-called formal economy, the latter has increasingly become “feminised”, that is, informalised or “housewifised” (Mies Citation2014). This means these activities are increasingly exempt from the regulatory power of public state apparatuses, all in the name of market freedom. So, just as women have arrived to occupy the public sphere, public power has become increasingly enfeebled by neoliberal policies.

In many ways, the public/private nature of migrant domestic workers’ performances on TikTok demonstrate the very specific way that these workers can make any claim to the public, and therefore the social and political. They test the boundaries of what counts as political when they exist in limbo as not-quite-worker, not-quite-family and non-citizen. In this sense, the socio-technics afforded by new media, acutely demonstrated by migrant domestic workers, expand on the repertoires of political participation through “play” (Vijay and Gekker Citation2021). This “third space” (Wright Citation2012) is a contrast to Habermas’ elite discourse, in which reason, argumentation and deliberation found the democratic ethos. In these counter-conducts, there is song and dance, satire, and a humorous reimagination of force relations.

To conclude, the kind of resistance that arises out of these specific circumstances is one that is not directed towards the usual targets of politics “proper” – parliaments, parties, civic groups or even the streets. Instead, they are aimed at other migrants and the public, in which they tell us who and what they are, and remind us of the value of their work. The creative act of making TikTok videos – their scripting, editing, and performance – embodies the redirection of their time and efforts to craft new subjectivities and new selves capable of thinking and doing otherwise. The various actions they not only portray but actually do or enact – e.g. going to the toilet to rest – is itself an act of limiting exploitation, domination and subjection. The very act of producing these videos goes against the rationalism that inhibits workers in Singapore from taking a day off. They are the very incarnation of counter-conduct, a resistance to the “three types of struggles” in Foucauldian genealogies. It is one that emerges from the specificity of migrant domestic workers’ lives in the Gulf, the socio-technics of TikTok, and the more-than-human sociality that was crafted in pandemic times and which continues to this day.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the participants and organisers of the workshop “Politics and Poetics of Strike” at the University of Groningen – particularly Judith Naeff, Senka Neuman Stanivuković and Ksenia Robbe. A special thank you to Caitlin Ryan for the lovely email afterwards. I would also like to thank Birsen Erdogan, Phyllis Livaha, Fulya Hisarlioglu, Julian Schmid, and Jungmin Seo for their engagement with the draft I presented at European Workshops in International Studies. Thank you to the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of the manuscript. This paper is made possible by funding from the EU’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement 101065330 KnowingDOM.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Liberty Chee

Liberty Chee is currently a Marie Sklodowska-Curie fellow at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. Her research examines migrant domestic work through the interdisciplinary lenses of feminist political economy, migration studies and international relations theory. Previously, she has investigated the role of recruitment agencies who deploy domestic workers in global migration governance. Her latest project looks into the International Labour Organisation as a site in which knowledge about domestic work is co-produced.

Notes

1 The research was conducted while I was a lecturer at the VU Amsterdam. The research design was such that it would clear the Research Ethics Review Committee's Online-Self Check without needing further review. The two elements that exempt the research from further review are that data are in the public domain and that the research would not result in harm to the subjects or the researcher.

References

- Adler-Nissen, R., and A. Tsinovoi. 2018. “International Misrecognition: The Politics of Humour and National Identity in Israel’s Public Diplomacy.” European Journal of International Relations 25 (1): 3–29. doi:10.1177/1354066117745365

- Allmark, P., and I. Wahyudi. 2016. “Female Indonesian Migrant Domestic Workers in Hong Kong: A Case Study of Advocacy Through Facebook and the Story of Erwiana Sulistyaningsih.” In The Asia Pacific in the Age of Transnational Mobility: The Search for Community and Identity on and Through Social Media, 19–40. London and New York: Anthem Press.

- Anderson, B. 2000. Doing the Dirty Work: The Global Politics of Domestic Labour. New York: Zed Books.

- Babis, D. 2021. “Digital Mourning on Facebook: The Case of Filipino Migrant Worker Live-in Caregivers in Israel.” Media, Culture & Society 43 (3): 397–410. doi:10.1177/0163443720957550

- Barrett, J. 2020. “Counter-conduct and its Intra-Modern Limits.” Global Society 0 (0): 1–25. doi:10.1080/13600826.2019.1705252.

- Barua, P., H. Haukanes, and A. Waldrop. 2016. “Maid in India: Negotiating and Contesting the Boundaries of Domestic Work.” Forum for Development Studies, July, 1–22. doi:10.1080/08039410.2016.1199444.

- Cadman, L. 2010. “How (not) to be Governed: Foucault, Critique, and the Political.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (2): 539–556. doi:10.1068/d4509.

- Caliandro, A. 2018. “Digital Methods for Ethnography: Analytical Concepts for Ethnographers Exploring Social Media Environments.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 47 (5): 551–578. doi:10.1177/0891241617702960.

- Chee, L. 2020. ““Supermaids”: Hyper-Resilient Subjects in Neoliberal Migration Governance.” International Political Sociology 14 (4): 366–381. doi:10.1093/ips/olaa009

- Cheng, Q., and C. Vicera. 2022. “Online Peer-Support Group’s Role in Addressing Filipino Domestic Workers’ Social Support Needs: Content and Social Media Metrics Analysis.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (15), Article 15. doi:10.3390/ijerph19159665.

- Chernobrov, D. 2022. “Strategic Humour: Public Diplomacy and Comic Framing of Foreign Policy Issues.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 24 (2): 277–296. doi:10.1177/13691481211023958

- Cherubini, D., G. G. Geymonat, and S. Marchetti. 2018. “Global Rights and Local Struggles: The Case of the ILO Convention N. 189 on Domestic Work.” Partecipazione e Conflitto 11 (3): 717–742. doi:10.1285/i20356609v11i3p717.

- Chin, C. 1998. In Service and Servitude: Female Domestic Workers and the Malaysian “Modernity” Project. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Chinkin, C. 1999. “A Critique of the Public/Private Dimension.” European Journal of International Law 10 (2): 387–395. doi:10.1093/ejil/10.2.387.

- Constable, N. 2007. Maid to Order in Hong Kong: Stories of Migrant Workers . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801460463.

- Davidson, A. 2011. “In Praise of Counter-Conduct.” History of the Human Sciences 24 (4): 25–41. doi:10.1177/0952695111411625.

- Dean, J. 2005. “Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Foreclosure of Politics.” Cultural Politics 1 (1): 51–74. doi:10.2752/174321905778054845.

- Death, C. 2010. “Counter-conducts: A Foucauldian Analytics of Protest.” Social Movement Studies: Journal of Social, Cultural and Political Protest 9 (3): 235–251. doi:10.1080/14742837.2010.493655

- Death, C. 2011. “Counter-conducts in South Africa: Power, Government and Dissent at the World Summit.” Globalizations 8 (4): 425–438. doi:10.1080/14747731.2011.585844

- Deleuze, G. 1989. Cinema 2: The Time Image. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dentith, S. 1995. Bakhtinian Thought: An Introductory Reader. London & New York: Routledge.

- Downe, P. 1999. “Laughing When it Hurts: Humor and Violence in the Lives of Costa Rican Prostitutes.” Women’s Studies International Forum 22 (1): 63–78. doi:10.1016/S0277-5395(98)00109-5

- Dreyfus, H., and P. Rabinow. 1982. Michel Foucault Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ellerman, M. L. 2017. “The Power of Everyday Subordination: Exploring the Silencing and Disempowerment of Chinese Migrant Domestic Workers.” Critical Asian Studies 49 (2): 187–206. doi:10.1080/14672715.2017.1299341.

- Elyas, N., and M. Johnson. 2014. “Caring for the Future in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Saudi and Filipino Women Making Homes in a World of Movement.” In Migrant Domestic Workers in the Middle East: The Home and the World, edited by B. Fernandez and M. de Regt, 141–164. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fernandez, B. 2014. “Degrees of (Un)Freedom: The Exercise of Agency by Ethiopian Migrant Domestic Workers in Kuwait and Lebanon.” In Migrant Domestic Workers in the Middle East: The Home and the World, edited by B. Fernandez, and M. de Regt, 51–74. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fernandez, B. 2019. Ethiopian Migrant Domestic Workers: Migrant Agency and Social Change. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Findlay, A., D. McCollum, S. Shubin, E. Apsite, and Z. Krisjane. 2013. “The Role of Recruitment Agencies in Imagining and Producing the “Good” Migrant.” Social and Cultural Geography 14 (2): 145–167. doi:10.1080/14649365.2012.737008.

- Fornet-Betancourt, Raúl, Helmut Becker, Alfredo Gomez-Müller, and J. D. Gauthier. 1987. “The Ethic of Care for the Self as a Practice of Freedom: An Interview with Michel Foucault on January 20, 1984.” Philosophy & Social Criticism 12 (2–3): 112–131. doi:10.1177/019145378701200202.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin Books.

- Foucault, M. 1978. The History of Sexuality: Volume I An Introduction. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. 1982. “The Subject and Power.” Critical Inquiry 8 (4): 777–795. doi:10.1086/448181

- Foucault, M. 2007a. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France 1977-1978. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. 2007b. The Politics of Truth. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

- Foucault, M. 2008. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at College de France 1978-1979. Basingstoke, Hampshire & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. 2010. The Government of Self and Others: Lectures at the College de France, 1982-1983 (Lectures at the Collège de France). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire & New York: : Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. 2011. The Courage of Truth: The Government of Self and Others II. Basingstoke, Hampshire & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. 2013. Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth: The Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984 Vol. I. New York: The New Press.

- Fox, K. 2018. “Humitas: Humour as Performative Resistance.” In Comedy and Critical Thought: Laughter as Resistance, 83–99. London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Gal, S. 2002. “A Semiotics of the Public/Private Distinction.” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 13 (1): 77–95.

- Goodman, R. 2010. Feminist Theory in Pursuit of the Public: Women and the “Re-Privatization” of Labor. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Greaves, M. 2015. “The Rethinking of Technology in Class Struggle: Communicative Affirmation and Foreclosure Politics.” Rethinking Marxism 27 (2): 195–211. doi:10.1080/08935696.2015.1007792.

- ILO. 2015. ILO Global Estimates on Migrant Workers: Results and Methodology, Special Focus on Migrant Domestic Workers. Geneva: ILO Labour Office.

- ILO. 2016. “Social Protection for Domestic Workers: Key Policy Trends and Statistics.” Paper 16, Social Protection Policy Paper.

- ILO. 2022. “Making the Right to Social Security a Reality for Domestic Workers the Right to Social Security a Reality for Domestic Workers: A Global Review of Policy Trends, Statistics and Extension Strategies.”

- Jiang, Z., and M. Korczynski. 2019. “The art of Labour Organizing: Participatory art and Migrant Domestic Workers ‘ Self-Organizing in London.” Human Relations 74 (6): 842–868. doi:10.1177/0018726719890664

- Johansson, A., and S. Vinthagen. 2016. “Dimensions of Everyday Resistance: An Analytical Framework.” Critical Sociology 42 (3): 417–435. doi:10.1177/0896920514524604.

- Kaur-Gill, S. 2022. “The Cultural Customization of TikTok: Subaltern Migrant Workers and Their Digital Cultures.” Media International Australia, 1–19. doi:10.1177/1329878X221110279.

- Kayoko, U. 2009. “Strategies of Resistance among Filipina and Indonesian Domestic Workers in Singapore.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 18 (4): 497–517. doi:10.1163/9789004258082_011.

- Kramer, C. 2020. “Parrhesia, Humor, and Resistance.” Israeli Journal for Humor Research 9 (1): 22–46.

- Kutz-Flamenbaum, R. 2014. “Humor and Social Movements.” Sociology Compass 8 (3): 294–304. doi:10.1111/soc4.12138

- Lan, P. C. 2003. “Negotiating Social Boundaries and Private Zones: The Micropolitics of Employing Migrant Domestic Workers.” Social Problems 50 (4): 525–549. doi:10.1525/sp.2003.50.4.525.

- Landes, J. B. 2003. “Further Thoughts on the Public/Private Distinction.” Journal of Women’s History 15 (2): 28–39. doi:10.1353/jowh.2003.0051.

- Liebelt, C. 2014. “The “Mama Mary” of the White City’s Underside Reflections on a Filipina Domestic Workers’ Block Rosary in Tel Aviv, Israel.” In Migrant Domestic Workers in the Middle East: The Home and the World, edited by B. Fernandez and M. de Regt, 95–115. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Light, B., J. Burgess, and S. Duguay. 2018. “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps.” New Media and Society 20 (3): 881–900. doi:10.1177/1461444816675438.

- Lindio-McGovern, L. 2010. “The Global Structuring of Gender, Race, and Class: Conceptual Sites of Its Dynamics and Resistance in the Philippine Experience.” In Social Change, Resistance and Social Practices, edited by D. Fasenfest, 191–204. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

- Ling, L. H. M. 1984. “East Asian Migration to the Middle East: Causes, Consequences and Considerations.” International Migration Review 18 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1177/019791838401800102

- Malik, S., and S. Z. Kadir. 2011. “The Use of Mobile Phone and Internet in Transnational Mothering among Migrant Domestic Workers in Singapore.” Available at SSRN 1976210.

- Malmvig, H. 2014. “Free Us from Power: Governmentality, Counter-Conduct, and Simulation in European Democracy and Reform Promotion in the Arab World.” International Political Sociology 8: 293–310. doi:10.1111/ips.12055.

- Malmvig, H. 2016. “Eyes Wide Shut: Power and Creative Visual Counter-Conducts in the Battle for Syria, 2011–2014.” Global Society 30 (2): 258–278.

- Mies, M. 2014. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour. London: Zed Books.

- Mintarsih, A. R. 2019. “Facebook, Polymedia, Social Capital, and a Digital Family of Indonesian Migrant Domestic Workers: A Case Study of The Voice of Singapore’s Invisible Hands.” Migration, Mobility, & Displacement 4 (1): 65–83. doi:10.18357/mmd41201918971

- Moukrabel, N. 2009. Sri Lankan Housemaids in Lebanon: A Case of “Symbolic Violence” and “Everyday Forms of Resistance”. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- The New Arab Staff. 2021, August 11. “Kuwaiti Authorities Rescue Filipina Domestic Worker. https://English.Alaraby.Co.Uk/; The New Arab.” https://english.alaraby.co.uk/news/kuwaiti-authorities-rescue-filipina-domestic-worker.

- Nişancıoğlu, K., and M. Pal. 2016. “Counter-Conduct in the University Factory: Locating the Occupy Sussex Campaign.” Global Society 30 (2): 279–300.

- Odysseos, L., C. Death, and H. Malmvig. 2016. “Interrogating Michel Foucault ‘ s Counter- Conduct: Theorising the Subjects and Practices of Resistance in Global Politics.” Global Society, 1–6. doi:10.1080/13600826.2016.1144568.

- Pande, A. 2012. “From “Balcony Talk” and “Practical Prayers” to Illegal Collectives: Migrant Domestic Workers and Meso-Level Resistances in Lebanon.” Gender and Society 26 (3): 382–405. doi:10.1177/0891243212439247.

- Pande, A. 2014. “Forging Intimate and Work Ties: Migrant Domestic Workers Resist in Lebanon.” In Migrant Domestic Workers in the Middle East: The Home and the World, 27–49. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pape, K. 2016. “ILO Convention C189—A Good Start for the Protection of Domestic Workers: An Insider’s View.” Progress in Development Studies 16 (2): 189–202. doi:10.1177/1464993415623151

- Parreñas, R. S., R. Silvey, M. C. Hwang, and C. A. Choi. 2019. “Serial Labor Migration: Precarity and Itinerancy among Filipino and Indonesian Domestic Workers.” International Migration Review 53 (4): 1230–1258. doi:10.1177/0197918318804769

- Rahman, M. M. 2012. “Bangladeshi Labour Migration to the Gulf States: Patterns of Recruitment and Processes.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 33 (2): 214–230. doi:10.1080/02255189.2012.689612.

- Ritter, C. S. 2021. “Rethinking Digital Ethnography: A Qualitative Approach to Understanding Interfaces.” Qualitative Research. doi:10.1177/14687941211000540.

- Roces, M. 2022. “Sunday Cinderellas Dress and the Self-Transformation of Filipina Domestic Workers in Singapore, 1990s – 2017.” Internatiojnal Quarterly for Asian Studies 531 (1): 121–142. doi:10.11588/iqas.2022.1.18828.

- Rossdale, C., and M. Stierl. 2016. “Everything Is Dangerous: Conduct and Counter-Conduct in the Occupy Movement.” Global Society 30 (2): 157–178.

- Samantroy, E. 2014. “Regulating International Labour Migration: Issues in the Context of Recruitment Agencies in India.” Contemporary South Asia 22 (4): 406–419. doi:10.1080/09584935.2014.979763.

- Schumann, M. F., and A. M. Paul. 2021. “The Giving up of Weekly Rest-Days by Migrant Domestic Workers in Singapore: When Submission is Both Resistance and Victimhood.” Social Forces 98 (4): 1695–1718. doi:10.1093/SF/SOZ089.

- Scott, J. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

- Smith, M. 2009. “Humor, Unlaughter, and Boundary Maintenance.” The Journal of American Folklore 122 (484): 148–171. doi:10.1353/jaf.0.0080

- Sokhi-Bulley, B. 2016. “Re-reading the Riots: Counter-Conduct in London 2011.” Global Society 30 (2): 320–339.

- Thoburn, N. 2003. Deleuze, Marx and Politics. London & New York: Routledge.

- Tondo, J. 2014. “Sacred Enchantment, Transnational Lives, and Diasporic Identity: Filipina Domestic Workers at St. John Catholic Cathedral in Kuala Lumpur.” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 62 (3–4): 445–470. doi:10.1353/phs.2014.0021

- Vijay, D., and A. Gekker. 2021. “Playing Politics: How Sabarimala Played Out on TikTok.” American Behavioral Scientist 65 (5): 712–734. doi:10.1177/0002764221989769.

- Vinthagen, S., and A. Johansson. 2013. ““Everyday Resistance”: Exploration of a Concept and its Theories.” Resistance Studies Magazine 1: 1–46.

- Wilkie, I. 2017. “Interview with Kate Fox – Stand-up Poet.” Comedy Studies 8 (2): 217–220. doi:10.1080/2040610X.2017.1344019.

- Wright, S. 2012. “From “Third Place” to “Third Space”: Everyday Political Talk in Non-Political Online Spaces.” Javnost - The Public 19 (3): 5–20. doi:10.1080/13183222.2012.11009088.