ABSTRACT

Within the healthcare sector, highly sensitive personal data, including data concerning health, is processed. The careless handling of such data can have a significant impact on the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons. It is central that data protection principles, including data protection by design, are followed by the healthcare sector. When these requirements are not met, it is crucial that enforcement action is taken to prevent personal data breaches. This article compares the enforcement carried out in the Netherlands and in the UK for breaches in the healthcare sector of the General Data Protection Regulation and the UK Data Protection Act 2018. The author reflects on whether more effective enforcement measures would lead to healthcare developments that are compliant with the data protection by design obligation (Article 25 of the GDPR). It is argued that in turn,compliance with this obligation can prevent personal data breaches and data protection complaints, rendering enforcement, and consequently recovery, superfluous.

1. IntroductionFootnote1

Within the healthcare sector, personal data related to the physical or mental health of natural persons, ‘health data’ for short, is processed. In accordance with Article 9(1) in conjunction with 4(15) of the GDPR, health data refers to special categories of personal data, which are in principle subject to a data processing ban, unless one of the exceptions listed under Article 9(2) of the GDPR applies to the data processing operations. This type of data is by its nature particularly sensitive in relation to fundamental rights and freedoms in which processing could create significant risks (recital 51 GDPR). The processing of health data by healthcare providers falls under one of the exemptions (Article 9(2)(c), (h) and (i) of the GDPR).

With the increase of digital applications and artificial intelligence in healthcare, the processing of health data has increased significantly. In addition to opportunities, this processing also entails certain risks, such as the risk of personal data breaches. In order to ensure the protection of personal data and prevent data breaches, both preventive and corrective measures are included in the GDPR (Dutch Centre Information Security and Privacy Protection Citation2017). On the one hand, it is compulsory to include data protection in the overall design process, i.e. when awarding the contract, development and use (please see data protection by design pursuant to Article 25 of the GDPR) (EDPB Citation2020). On the other hand, if it should appear that no or insufficient measures have been taken, it is vital ‘to reestablish compliance with the rules, and/or to punish unlawful behaviour’ (EDPB Citation2017b, p. 6). Pursuant to Articles 83 and 51(1) of the GDPR, this enforcement remit is delegated to the supervisory authority, which, in the Netherlands, is the Dutch Data Protection Authority (Section 6 of the GDPR Implementation Act) and the Information Commissioner (Section 114 of the Data Protection Act 2018) in the United Kingdom.Footnote2

This article examines the extent to which the enforcement options and associated legal remedies included in the GDPR contribute to the protection of personal data in the health sector in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. This involves a comparison of the implementation of enforcement by the Dutch Data Protection Authority (Dutch DPA) with that of the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), given that the latter has traditionally been known as an active regulator (Santifort Citation2019). The comparison focuses on the enforcement measures taken by the two authorities and reflects on whether more effective enforcement measures would lead to healthcare developments that are compliant with the data protection by design obligation (Article 25 of the GDPR). It is argued that, in turn compliance with the data protection by design obligation can prevent personal data breaches and data protection complaints, rendering enforcement, and consequently recovery, superfluous.

Although the UK has not been part of the EU since 1 January 2021 as a result of Brexit, it is nevertheless relevant to compare the implementation of enforcement action by the Information Commissioner with that of the Dutch Data Protection Authority. On 28 June 2021, the European Commission determined that the UK Data Protection Act ensures an adequate level of protection, as a result of which an adequacy decision has been issued to the United Kingdom (European Parliament and of the Council Citation2021). This means that a transfer of personal data may take place between data controllers and processor located in the EU and the UK where no specific authorisation is required (Article 45(1) of the EU GDPR). One of the requirements for issuing an adequacy decision is:

The existence and effective functioning of a supervisory authority with responsibility for ensuring and enforcing compliance with the data protection rules, including adequate enforcement powers, for assisting and advising the data subjects in exercising their rights and for cooperation with the supervisory authorities of the Member States. (Article 45(2)(b) of the GDPR)

This article sets out to compare the enforcement of data protection breaches in the healthcare sector in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. It then reflects on whether more effective enforcement measures would lead to healthcare developments that are compliant with the data protection by design obligation (Article 25 of the GDPR). To achieve this aim, this article will discuss the tasks and powers of the national supervisory authority of the Netherlands and the United Kingdom that arise from the GDPR in detail. Subsequently, an insight is provided into the jurisprudence on the application of the enforcement options and corresponding legal remedies in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. This jurisprudence will serve as input for the analysis when discussing problems experienced with regard to enforcement and the effect on the obligation of data protection by design.

2. Tasks and powers of the national supervisory authority of The Netherlands and the United Kingdom

Pursuant to Article 51(1) of the EU GDPR, each Member State shall provide for one or more independent public authorities to be responsible for monitoring the application of the EU GDPR. According to recital 117 of the EU GDPR and jurisprudence from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), the establishment of a national supervisory authority is regarded as an ‘essential component of the individual’s right to data protection’ (Hijmans Citation2020a, p. 867). In order to comply with this obligation, the Netherlands has established the Dutch Data Protection Authority (Dutch DPA) through national legislation that implements the EU GDPR in the form of the GDPR Implementation Act (UAVG). In the United Kingdom, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) is responsible for monitoring the application of the UK Data Protection Act (Article 51 UK Data Protection Act and Part 5 of the Data Protection Act 2018).

The tasks of both national supervisory authorities arise from Article 57(1) of the GDPR. These include: (1) promoting the awareness of controllers and processors of their obligations under the GDPR, (2) monitoring and enforcing the application of the GDPR and (3) handling complaints lodged by a data subject. Kuner et al. note that the national supervisory authorities therefore exercise a dual role: they act both as advisers on data protection issues and as enforcing bodies for data protection laws (Hijmans Citation2020b, p. 933).

In order to be able to perform these tasks, the national supervisory authority has a number of advisory, investigative and corrective powers. These include advising the controller in accordance with the prior consultation procedure or data protection impact assessments (DPIA) pursuant to Article 36 GDPR. With regard to its investigative and corrective powers, the national supervisory authority may (1) order the data controller/processor to provide it with any information it should require for the performance of the task, (2) to issue warnings/reprimands and (3) to impose a temporary or definitive limitation (including a ban on processing) and administrative fines. In addition, pursuant to Article 57(6) of the EU GDPR, each Member State may provide by law that its supervisory authority shall have additional powers. In the Netherlands, the additional powers of the Dutch DPA are fleshed out and implemented in the aforementioned UAVG. In the United Kingdom, the additional powers of the ICO are set out in the UK Data Protection Act 2018.

2.1. Advisory powers

Article 25 of the GDPR requires healthcare providers, as controllers, to take ‘appropriate technical and organisational measures’, which are designed to implement data protection principles in an effective manner and to integrate the necessary safeguards into the processing in order to meet the requirements of the GDPR and protect the rights of data subjects. The EU GDPR/UK Act does not provide any further definition of the terms ‘appropriate technical and organisational measures’ and ‘necessary safeguards’. According to the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), this includes all methods and means that a controller can involve in the processing (EDPB Citation2020).

According to Burton in Kuner et al., the risk of the data processing must first be identified in order to be able to establish what methods or means are indeed appropriate (Burton Citation2021). Hooghiemstra and Nouwt (Citation2020) add that this relates to an objective risk, meaning, in other words, that it should concern a generally recognised risk. The security measures to be taken thereafter must limit this risk and are, moreover, subject to an obligation regarding reasonable efforts having been made rather than to an obligation in respect of results (Burton Citation2021).

The measures to be taken for the healthcare sector in the Netherlands are set out in the international standards ISO 27001, ISO 27002 and ISO 27701. The Royal Netherlands Standardization Institute (NEN) has established additional standards for the Dutch healthcare sector, namely: NEN 7510, NEN 7512, NEN 7513 and NTA 7516 (NEN, Citationn.d.). For example, pursuant to NEN 7510 healthcare providers are required to take technical measures to ensure access for authorised users and to prevent unauthorised users (9.2 NEN 7510-2) and ensure that the login process must consist of at least two factors of authentication (9.4.1. NEN 7510-2), so-called ‘two-factor authentication’.

In the UK, in addition to the aforementioned ISO standards, the 10 National Data Guardian (NDG) standards apply to data security (NHS, Citationn.d.-b). The NDG for health and social care ‘advises the health and adult social care system in England to help ensure that people's confidential information is kept safe and used properly’ (NDG, Citationn.d.). The role of the NDG is laid down in Section 1 of the Health and Social Care (National Data Guardian) Act 2018 and equally sets out that the NDG is authorised to issue official guidelines with regard to data processing in health and adult social care in England. The NDG therefore does not qualify as a regulator, but will cooperate the ICO in the UK if necessary. The 10 NDG standards inter alia include rules on ‘managing data access’ whereby personal confidential data may only be accessible to employees who need the data for their current position and access must immediately be blocked where this is no longer the case, which should, where possible, involve the use of multifactor authentication (4.3.1.–4.5.5. NDG) (NHS Digital Citation2022). As the (NHS) healthcare provider, an online self-assessment tool, i.e. the Data Security and Protection Toolkit (DSPT), is used to ensure compliance with the NDG’s 10 data security standards (NHS, Citationn.d.-a).

Identification of the risks by the healthcare provider takes place by conducting a DPIA. If the DPIA shows that the processing would result in a high risk in the absence of measures taken to mitigate the risk, then the healthcare provider is obliged to consult the national supervisory authority regarding this matter (Article 36(1) of the GDPR). If the national supervisory authority believes that the intended processing will infringe upon the GDPR, it will provide a written opinion on the issue within eight weeks following receipt of the request.

2.2. Investigative and corrective powers

Failure to comply with the obligation of data protection by design during the design process may lead to personal data breaches (Article 4(12) EU GDPR/UK Act). According to Tosoni in Kuner et al., this definition consists of three parts: ‘(1) the breach is the result of a violation of the security measures that the controller or processor has implemented, or should have implemented, (2) the security incident must lead to the accidental or unlawful destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorised disclosure of, or access to, (3) personal data. This includes both incidents that occurred intentionally and inadvertently’ (Tosoni Citation2020, p. 191 and 192; Tosoni Citation2021, p. 49).

Where a healthcare provider ‘has a reasonable degree of certainty that a security incident has occurred that has led to personal data being compromised’, it is obliged to report this incident to the national supervisory authority as a personal data breach without unreasonable delay and, if possible, within 72 h of becoming aware of the incident (EDPB Citation2017a).

The national supervisory authority cannot only be informed of a breach by way of a personal data breach notification. The data subject, or a non-profit organisation authorised by the data subject of which the statutory objective is the protection of personal data in the public interest, has the right to lodge a complaint if it infringes upon the GDPR (Article 77(1) of the GDPR and recital 142 of the GDPR).

The Dutch DPA distinguishes between two types of data protection complaints, namely between ‘tips’ and ‘complaints’. A tip can be submitted anonymously and need not relate to a breach by an organisation in respect of the personal data of the data subject, which is the case for a complaint (Dutch DPA, Citationn.d.-f). Furthermore, the data subject can request that the Dutch DPA take enforcement action in the complaint. In this situation, the complaint is a ‘request for enforcement action’ pursuant to Section 1:3(3) of the General Administrative Law Act (Algemene Wet bestuursrecht, Awb) (Dutch DPA Citation2018a). An objection and appeal may be lodged against the dismissal of such a request (Section 1:3(1) in conjunction with 1:5 of the General Administrative Law Act) in accordance with Article 78 of the EU GDPR and recital 143 of the EU GDPR. If the complaint relates to a decision of a legal person under public law (administrative body), the data subject must first submit an objection to the relevant government organisation or lodge a relevant appeal with the administrative court (Section 1:5 of the General Administrative Law Act). The difference between ‘tips’ and ‘complaints’, potentially involving a request for enforcement, does not exist for the UK’s ICO.

If the infringement has arisen due to non-compliance with the requirements of the GDPR, the national supervisory authority has various corrective measures at its disposal (Article 58(2) of the GDPR). These include issuing a warning or reprimand, imposing a temporary or definitive limitation, including a ban or an administrative fine. Pursuant to the guidelines of the EDPB, any administrative fine that is imposed must be (1) effective, (2) proportionate and (3) dissuasive. In addition, the purpose of the fine must serve to ‘reestablish compliance with the rules, or to punish unlawful behaviour’ (EDPB Citation2017b, p. 6). The level of the administrative fine depends inter alia on the nature, gravity and duration of the infringement (Article 83(2)(a) of the GDPR). A maximum fine of 10,000,000 euro or 2% of total worldwide annual turnover (Article 83(4)(a) of the EU GDPR) applies to infringements of data protection by design (and data breaches).

In respect of its enforcement, the Dutch DPA takes a risk-based approach, meaning that it devotes particular attention to potential personal data breaches that could affect large groups of people (Dutch DPA Citation2018b). In the 2018–2019 period, it focused primarily on the security of medical data within the healthcare sector. In the 2020–2023 period, its focus was on ‘data trade’, which also included data protection by design and eHealth (Dutch DPA Citation2018b). The vision of the Dutch DPA remained ‘risk-based supervision’ (Dutch DPA Citation2018b). However, the publicly accessible position papers and policy documents do not show exactly how enforcement takes place and do not include a clear escalation strategy.Footnote3

However, the Dutch DPA has drawn up policy rules for the prioritisation of the investigation of complaints and in relation to determining the level of administrative fines (Dutch DPA Citation2018a). Article 2(3) of the Policy Rules on Prioritising the Investigation of Complaints (Beleidsregels Prioritering klachtenonderzoek) sets out in which cases the Dutch DPA will proceed with a further investigation following receipt of a data protection complaint. The policy rules on fines (boetebeleidsregels) include a categorised classification with the corresponding bands for the administrative fines to be imposed (Dutch DPA Citation2019). Hooghiemstra and Nouwt (Citation2020) observe that administrative fines can likewise be imposed on administrative bodies and that it is not intended for them to receive different treatment from the private sector.

In addition to the corrective measures that arise from the EU GDPR, the Dutch DPA has the option of imposing a penalty for non-compliance (Article 58(6) of the EU GDPR, Section 16(1) of the UAVG and Section 5:32(1) of the Awb). A penalty for non-compliance consists of a remedial sanction, comprising: (a) an order to fully or partial rectify the violation, and (b) the obligation to pay a sum of money if the order is not carried out or is not carried out on time (Section 5:31(d) of the Awb).

The UK’s ICO has its escalation strategy with regard to enforcement laid down in its Regulatory Action Policy 2018 (RAP 2018). The RAP 2018 has since been updated with the RAP 2021, supplemented with the ‘DRAFT Statutory guidance on our regulatory action’, which was submitted for public consultation between December 2021 and March 2022 (UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-d).

The RAP inter alia stipulates in which situations the Information Commissioner’s Office will issue an ‘(urgent) information notice’ (formal request to provide the ICO with information to assist their investigation), ‘assessment notice’ (a notice to allow them to investigate compliancy with the UK Data Protection Act) or a ‘penalty notice’ (UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-d, p. 15-19). The criteria with regard to the next steps are likewise included, alongside tools to determine the level of any penalty.

On 3 January 2022, a new Information Commissioner was appointed in the United Kingdom (UK’s ICO Citation2022c). Not long after taking office, the new Information Commissioner introduced the ‘ICO25 strategic plan’, outlining what the ICO wants to have achieved by 2025 (UK’s ICO Citation2022b). ICO25 was submitted for public consultation between 14 July 2022 and 22 September 2022. The ICO received a total number of 52 responses to the survey, with the majority indicating that they supported the contents of the ICO25 (UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-h).

The new policy means that from January 2022 the UK’s ICO will also publish reprimands, which previously was not the case (UK’s ICO Citation2022a). In addition, the ICO25 includes a ‘revised approach for public sector fines and enforcement’, meaning the ICO will take a restrained approach to fining public sector organisations (UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-f). As of January 2022 therefore, the decision on fines for public sector organisation includes an indication of the level of the fine when a fine was considered by the ICO but a reprimand was ultimately imposed (UK’s ICO Citation2022a).

3. Implementation of enforcement in The Netherlands and the United Kingdom

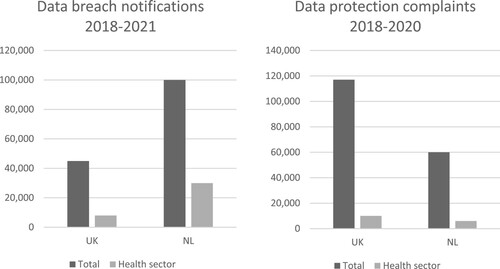

Between 2018 and 2021, the Dutch DPA received approximately 100,000 data breach notifications, spread across nine sectors (Dutch DPA, Citationn.d.-b). By far the most data breach notifications, in the region of 30,000, originated from the healthcare sector, which includes pharmacies, general practitioners, hospitals, healthcare foundations, population screening programmes, healthcare insurance companies, youth care, mental health institutions, addiction treatment clinics and other healthcare providers such as occupational health and safety services. In the same period, the ICO in the UK received a total of around 45,000 data breach notifications, of which roughly 8,000 notifications originated from the healthcare sector (UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-b).

In addition, between 2018 and 2020, the Dutch DPA received a total of around 60,000 data protection complaints of which approximately 6,000 related to the healthcare sector.Footnote4 Most complaints related to the handling of the rights of data subjects by organisations and the transfer of personal data to other organisations (Dutch DPA, Citationn.d.-b). Between 2018 and 2020, the number of data protection complaints received by the ICO was around 117,000, of which around 10,000 related to the healthcare sector (for a schematic representation please see ) (UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-b). This high number of data breach notifications and data protection complaints immediately illustrates the importance of data protection by design in the healthcare sector: if data protection is taken into account in the eHealth design process from inception, this can prevent personal data breaches. Furthermore, healthcare providers are better able to process requests in respect of rights of data subjects due to the digital application rendering this technically possible.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of data breach notifications received between 2018 and 2021 and data protection complaints 2018–2020 received between 2018 and 2020.

shows that the Dutch DPA received more data breach notifications from the healthcare sector than the ICO in the UK. The ICO, however, received more data protection complaints than the Dutch DPA. A comparison shows the following: the population of the United Kingdom totals around 67 million whereas the Netherlands has around 18 million inhabitants (ONS, Citationn.d.; CBS, Citationn.d.). This means that the United Kingdom has approximately 3.7 times as many inhabitants as the Netherlands.

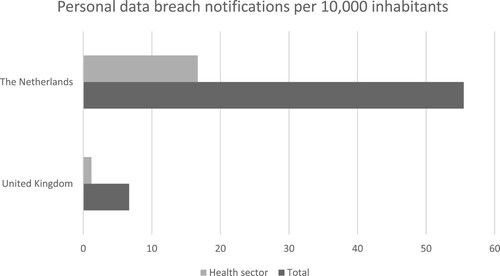

The foregoing means that the Dutch DPA received a total of 55.5 personal data breach notifications and 16.7 notifications from the healthcare sector per 10,000 inhabitants between 2018 and 2021. However, the ICO in the UK received a total of 6.7 and 1.2 notifications from the healthcare sector per 10,000 inhabitants over a comparable period. In total, the Dutch DPA therefore received more than 8 times as many notifications as the ICO. This significant difference is clearly reflected in .

Figure 2. Schematic overview comparison of the number of personal data breach notifications per 10,000 inhabitants.

In 2020, the budget of the Dutch DPA amounted to nearly 25 million euros and employed 189 employees (179 FTE) (Dutch DPA, Citationn.d.-e). The ICO, by contrast, had a budget of 61 million pound sterling (equivalent to approximately 70 million euros) at its disposal and employed 822 employees (744 FTE) (UK’s ICO Citation2020; UK’s ICO Citation2021). Unlike the Dutch DPA, the ICO is not only a regulator in the domain of data protection, but its remit, for example, also covers the Freedom of Information Act. It is, however, unclear exactly how many employees it relies on to handle personal data breach notifications and data protection complaints (DCMS Citation2020; UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-b).

In relation to the data shown above, it should be noted that the Netherlands is somewhat further ahead in terms of digitisation compared to the United Kingdom, as shown by the World Digital Competitiveness (WDC) Ranking 2022: the United Kingdom ranks 16th with a score of 86.45, whereas the Netherlands takes 6th place with a score of 97.85.Footnote5 In terms of digitisation in the healthcare sector, the Netherlands scores almost the same as the United Kingdom as regards availability, maturity and use of (key national) health datasets (Oderkirk Citation2021; Socha-Dietrich Citation2021). In the Netherlands (100%) and the United Kingdom (99%), (nearly) all primary care physician offices make use of electronic medical records (OECD, Citationn.d.).

It will be examined to what extent enforcement action was ultimately taken in respect of these data breaches and data protection complaints and what the underlying reasons were. The focus is on the issue of whether the technical and organisational measures taken have been restored for the relevant eHealth application as a result of the enforcement action carried out. The following section will first discuss the corrective measures imposed by the Dutch DPA, followed by the enforcement action taken by the ICO in the UK.

3.1. Corrective measures of the Dutch data protection authority

Between 2018 and 2022, the Dutch DPA issued a total of one warning, one reprimand, one processing ban, nine penalties for non-compliance and fourteen administrative fines.Footnote6 Looking specifically at the healthcare sector, the figures above relate to five penalties for non-compliance and three administrative fines (Dutch DPA, Citationn.d.-a). contains a schematic overview of the various sanctions imposed within the healthcare sector by the Dutch DPA between 2018 and 2022.

Table 1. Schematic overview of enforcement action of the Dutch data protection authority 2018–2022.

One striking aspect that should be noted is the small number of sanctions imposed in relation to the number of data breach notifications and data protection complaints submitted. In its 2020 annual report, the Dutch DPA itself notes that this is due to the fact that the handling of reports and complaints is very time consuming and that it has limited (Dutch DPA, Citationn.d.-e). As a result, the Dutch DPA was not able to deal with a large number of data breach notifications and data protection complaints. The National Ombudsman of the Netherlands has stated that the Dutch DPA may not rely on this as an excuse (Dutch National Ombudsman Citation2021).

A review of the basis of the funding of the Dutch DPA has showed that a number of key functions of a supervisory authority are absent in the annual report, including a risk assessment, and impact assessment, strategy and policy (Dutch Minister for Legal Protection Citation2020; KPMG Citation2020). Consequently, it is unclear whether the allocation of employees and funding is leading to the most effective implementation.

The same report shows that the Dutch DPA has been granted a relatively high budget compared to the other 31 national supervisory authorities (KPMG Citation2020). Moreover, it is undergoing strong growth terms of its budget and therefore in terms of personnel. Only the supervisory authorities of Finland and Ireland show stronger growth on both fronts. At the same time, the Dutch DPA generally receives many more data breach notifications and data protection complaints per 100,000 inhabitants compared to the supervisory authorities of other Member States.

The jurisprudence review carried out also shows that nearly all cases of enforcement involved the same infringements, namely the absence of: (1) technical measures for authorisations, (2) two-factor authentication and (3) logging (control). This mainly relates to measures that must be taken in accordance with the Dutch standard NEN 7510, for which healthcare providers are dependent on their supplier. For example, it appears that the Dutch DPA took enforcement action against two major health insurance companies (VGZ and Menzis) concurrently, where the same (type of) infringements appeared to be taking place. The text of the two enforcement decisions is virtually identical.

Finally, it appears that the Dutch DPA did not impose the same corrective measures in every enforcement case. As shown in , the Dutch DPA only imposed an administrative fine on two occasions and only imposed a penalty for non-compliance on four occasions, and imposed a combination of both on a single occasion. The fact that only an administrative fine was imposed in two cases can be accounted for by the fact that the required improvements had already been implemented. However, it is unclear why in four cases no administrative fine was imposed in addition to a penalty for non-compliance.

The absence of an escalation strategy has likewise been noted by the Dutch research firm Pro Facto in its research into the evaluation of the GDPR Implementation Act (UAVG), which has caused a great deal of ‘misunderstanding, annoyance, frustration and anger’ among those under supervision (Winter 2022). The research shows that organisations would like to receive more guidance from the Dutch DPA regarding the interpretation of the standards of the EU GDPR and their application.

3.2. Corrective measures of the ICO in the UK

Between 2018 and 2022, the ICO in the UK took enforcement action in 128 cases, whereas the Dutch DPA took enforcement action on 26 occasions. In total, the ICO issued 31 reprimands, 38 enforcement notices, 58 monetary penalties and initiated one prosecution (UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-c). Out of the total of 128 cases, five related to the healthcare sector. The ICO issued 3 reprimands, 1 monetary penalty and initiated a single prosecution within this sector. shows a schematic overview of the various sanctions imposed within the healthcare sector by the ICO between 2018 and 2022.

Table 2. Schematic overview of the enforcement action of the UK’s information commissioner’s office 2018–2022

Like the Dutch DPA, the ICO received thousands of personal data breach notifications and data protection complaints between 2018 and 2022 but only took enforcement action in five cases. It may be that the ICO has imposed more reprimands in the past than shown in . However, this information was not publicly available, given that any reprimands imposed have only been published since January 2022.

Unlike the Dutch DPA, the ICO does have a clear escalation strategy with regard to its enforcement due to the fact that it has laid down this strategy in various protocols that are accessible to the public. However, a consultation by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) to reform the data protection regime in the United Kingdom shows that the ICO has encountered problems with the implementation of its policies: in the past, for example, it did not receive timely and detailed information that it requested during its investigations and a number of individuals refused to cooperate (DCMS Citation2021).

Although the ICO is more transparent in respect of its enforcement, there has also been criticism of the way it functions. The Open Rights Group (ORG) believes that ‘the ICO is failing to use their powers and responsibilities to deliver GDPR’s regulatory expectations’ (Killock Citation2020). The ORG states that the administrative fines imposed by the ICO are primarily aimed at personal data breaches and not at systematic gross breaches that are legally complex. The ORG is also critical of the policy applied in respect of government organisations and has called on the DCMS to investigate how effective the ICO actually is, given that according to the ORG many people are disappointed in its enforcement action.

The fact that the enforcement action taken by the ICO leaves something to be desired has likewise been observed by Erdos (Citation2022), who inter alia refers to the fact that between 2021 and 2022 the ICO did not issue any GDPR enforcement notices and only imposed four administrative fines. Furthermore, he notes that there is a lack of effective holistic scrutiny on the part of the DCMS, which is an aspect likewise suggested by Hewson and Tumbridge (Citation2020), who believe that there is insufficient research into the performance of the ICO.

4. Analysis of the implementation of enforcement in The Netherlands and the United Kingdom

The right to respect for private and family life is included in the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (Article 8), EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (Article 7) and UK’s Human Rights Act 1998 and is a human right that has been fleshed out in the GDPR. The aim of the GDPR is ‘to harmonise the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons in respect of processing activities and to ensure the free flow of personal data between Member States’ (recitals 3 and 9 of the GDPR). In order to provide a consistent level of protection, the GDPR includes obligations for controllers/processors, including data protection by design (prevention) and requires consistent relevant supervision by the national supervisory authority (correction) (recital 13 of the GDPR).

Underlying research shows that since 2018 approximately 30,000 data breach notifications and 6,000 data protection complaints were submitted to the Dutch DPA from the healthcare sector. The ICO received 8,000 notifications and 10,000 complaints over a comparable period. Only in a handful of cases did the Dutch DPA (a total of seven) and the ICO in the UK (a total of five cases) take enforcement action. Due to the fact that not all complaints and notifications are processed, eHealth applications are still being used that are known not to comply with data protection by design.

Dutch users do not feel heard by the Dutch DPA and have expressed their dissatisfaction to the National Ombudsman of the Netherlands (2021). The 200 + complaints mainly concerned the processing time, provision of information and treatment by the Dutch DPA. In addition, there were regular complaints about the decision of the Dutch DPA not to conduct any further investigation. This problem is likewise extant in the United Kingdom, where the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (Citation2021) received a total number of 425 complaints about the ICO between 2019 and 2021.

Underlying research also shows that virtually the same infringements took place in the Netherlands, which, however, were not subjected to the same corrective measures. Due to the lack of an escalation strategy, there cannot be said to be ‘consistent monitoring of the processing of personal data, and equivalent sanctions’ as required by the EU GDPR. In 2021, the European Parliament (EP) likewise expressed its concern regarding the irregular and absence of enforcement of the EU GDPR by national supervisory authorities (European Parliament Citation2021).

Unlike the Dutch DPA, the ICO in the UK does have a clear escalation strategy, which is fleshed out in the RAP. Although the policies used by the ICO may be fully documented, it has had a different policy in place for public sector organisations since 2022. In principle, the Dutch DPA, on the other hand, makes no such distinction (see the UWV case).Footnote7 The ICO has been criticised by the ORG for this two-sided policy. In that respect, the ICO also lacks ‘equivalent sanctions’ as prescribed by the UK Data Protection Act.

The absence of consistent supervision by the Dutch DPA has a direct impact on the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons: without consistent oversight, there is no incentive to be GDPR compliant and to ensure that eHealth complies with data protection by design (Winter 2022). The evaluation study carried out by Pro Facto shows that Dutch data protection officers (DPOs) of controllers/processors are therefore reluctant to report personal data breaches due to the fact that the probability of enforcement action is low if incidents are not report, whereas reporting a personal data breach may lead to an administrative fine or to reputational damage for the organisation (Winter 2022).

In addition to the corrective task of handling complaints, monitoring and enforcement, under Article 57(1) of the EU GDPR, the national supervisory authority has the advisory task of making controllers and processors better acquainted with their obligations arising from the EU GDPR. The Dutch DPA currently only carries out this advisory role to a limited extent: organisations and DPOs can submit general questions about the EU GDPR, but the Dutch DPA will not issue opinions on specific situations (Dutch DPA, Citationn.d.-d; Dutch DPA, Citationn.d.-c). However, such a restriction does not arise from the (recital of the) GDPR. Pro Facto shows that in the Netherlands there is a need for advice on specific situations (Winter 2022).

The ICO in the UK, by contrast, does provide organisations with the opportunity to ask questions about the application of the UK Data Protection Act, whether by phone, email or via a live chat (UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-a; UK’s ICO, Citationn.d.-e). The ICO even offers small organisations with fewer than 50 employees the opportunity to take part in a ‘free online advisory check-up’. In addition, (NHS) healthcare providers are able to use the Data Security and Protection Toolkit: the online self-assessment tool that is offered by the NDG. It may be that this preventive approach in the UK has led to significantly fewer data breach notifications and data protection complaints per 10,000 inhabitants than the number received by the Dutch DPA in the period we examined.

5. Conclusion

This research shows that the advisory and corrective tasks of the national supervisory authority are intertwined and that it is vital that both tasks are performed adequately in order to ensure data protection in a healthcare context. This is particularly relevant when one considers that clear corrective measures taken up in the ‘design’ of improved healthcare services/applications (as defined in Article 25 of the GDPR) improves the future compliance of the same healthcare services/applications.

In addition, advice (by the national supervisory authorities) on data protection throughout the entire design process can ensure that only healthcare services/applications are used that comply with the data protection by design obligation: taking appropriate technical and organisational measures by the healthcare provider can prevent personal data breaches and embedding the necessary guarantees to be able to carry out requests regarding the rights of data subjects can prevent data protection complaints.

At present the Dutch DPA receives thousands of personal data breach notifications and data protection complaints from the healthcare sector. Regrettably, it only took enforcement action in a handful of comparable cases. When the Dutch DPA does act in relation to a case, there is no escalation strategy, as a result of which there is no incentive in the Netherlands to be GDPR compliant. This has a direct impact on the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons. The Dutch DPA will therefore have to focus on (1) shorter processing times, (2) more consistency in its enforcement by applying an escalation strategy and (3) intensifying enforcement in respect of infringements of data protection by design in order to be able to ensure data protection in the healthcare sector.

Given that the cases largely relate to the same types of breaches, it makes sense that, like the ICO in the UK, the Dutch DPA should focus more on information provision and advice in respect of data protection by design. Between 2018-2022, the ICO in the UK has demonstrated that a preventive approach is indeed effective: during this period, it received significantly fewer personal data breach notifications per 10,000 inhabitants than the Dutch DPA.

This limited enforcement strategy, in the Netherlands and in the United Kingdom, regrettably, does not lead to a structural improvement of data protection rights of data subjects. A more active advisory and corrective enforcement approach by national supervisory authorities directed towards the responsibility of controllers in the design of healthcare services and applications can in turn prevent additional personal data breaches and data protection complaints and better protection for data subjects.

Acknowledgement

This research was conducted as part of the Cybersecurity Noord Nederland project, which project has receivedfunding from the Ruimtelijk Economisch Programma (REP) of the Province of Groningen.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 On 17 March 2023, an article was published in the Nederlands Juristenblad (Netherlands Law Journal) that focuses specifically on the situation in the Netherlands (please see Hof, Jessica P., and Petra A.T. Oden. 2023. ‘Inbreuken op data protection by design in de zorgsector. Leidt handhaving tot verbetering van eHealth?’ Nederlands Juristenblad 2023/676: 770-778). Any literature, laws and regulations published after 1 June 2023 has or have not been incorporated in the text.

2 In the Netherlands, the EU GDPR has been implemented in detail in the GDPR Implementation Act (Uitvoeringswet Algemene Verordening Gegevensbescherming, UAVG). The relevant and equivalent UK legislation is the Data Protection Act 2018.

3 All position papers made available to the public by the Dutch DPA (twelve in total) and policy documents (five in total), were examined for this purpose: Dutch DPA, ‘Documents. Here you find all public documents of the Dutch Data Protection Authority from 25 May 2018’, https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/documenten.

4 At the time of writing, only the data breach reports up to and including 2021 and the complaint reports up to and including 2020 had been published.

5 IMD. Citationn.d. ‘IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking 2022.’ IMD. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://imd.cld.bz/Digital-Ranking-2022/18/. The WDC ranking ‘analyses and ranks the extent to which countries adopt and explore digital technologies leading to transformation in government practices, business models and society in general’’ (quote p. 30).

6 The structured jurisprudence review only involved consultation of autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl, due to the fact that it explicitly states that it includes an overview of all fines and sanctions imposed by the Dutch DPA since 2018.

7 This remains doubtful due to the lack of a clear escalation strategy and therefore transparency. In particular, given that a large-scale data breach was brought to light at the Dutch Municipal Health Service (GGD GHOR) in 2021 as a result of the systems having been insufficiently secure. At the time, the Dutch DPA did not impose any corrective measures. Please see Dutch DPA, ‘Eindbrief onderzoek beveiliging persoonsgegevens ‘GGD GHOR en GGD’ van 8 November 2021’: https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/sites/default/files/atoms/files/onderzoek_beveiliging_ggd_corona.pdf.

References

- Burton, Cédric. 2021. “Chapter IV - Controller and Processor: Article 32. Security of Processing.” In The EU General Data Protection Regulation: A Commentary. Update of Selected Articles, edited by Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave, and Christopher A. Docksey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- CBS. n.d. “Bevolkingsteller.” CBS. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-bevolking/bevolkingsteller.

- DCMS. 2020. “Explanatory Framework for Adequacy Discussions Section G: The Role of the ICO and Redress. Government.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/explanatory-framework-for-adequacy-discussions.

- DCMS. 2021. “Data: A new direction.” Government. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1022315/Data_Reform_Consultation_Document__Accessible_.pdf.

- Dutch Centre Information Security and Privacy Protection. 2017. “Grip op Privacy: Handleiding Privacy by Design.” CIP Overheid. https://www.cip-overheid.nl/media/cbubjt3f/20170507-handleiding-privacy-by-design-v3_0.pdf.

- Dutch Council of Public Health & Society. 2020. “Zorg op afstand dichtbij? Digitale zorg na de coronacrisis.” Rijksoverheid. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/e-health/documenten/rapporten/2020/09/28/zorg-op-afstand-dichterbij.

- Dutch DPA. 2018a. “Beleidsregels Prioritering klachtenonderzoek.” Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/sites/default/files/atoms/files/beleidsregels_prioritering_klachtenonderzoek.pdf.

- Dutch DPA. 2018b. “Toezichtkader Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens: Uitgangspunten voor toezicht 2018-2019. Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens.” https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/documenten/toezichtkader-autoriteit-persoonsgegevens-2018-2019.

- Dutch DPA. 2019. “Boetebeleidsregels Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens 2019.” Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0041994/2019-03-15.

- Dutch DPA. n.d.-a. “Boetes en Andere Sancties.” Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/nl/publicaties/boetes-en-sancties.

- Dutch DPA. n.d.-b. “Datalekrapportages en Klachtenrapportages.” Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/nl/publicaties/rapportages-klachten-en-datalekken.

- Dutch DPA. n.d.-c. “Functionaris Gegevensbescherming (FG).” Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/nl/onderwerpen/algemene-informatie-avg/functionaris-gegevensbescherming-fg#hoe-kan-ik-als-fg-de-ap-een-vraag-stellen-over-privacy-7147.

- Dutch DPA. n.d.-d. “Informatie- en Meldpunt Privacy.” Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/nl/contact-met-de-autoriteit-persoonsgegevens/informatie-en-meldpunt-privacy.

- Dutch DPA. n.d.-e. “Jaarverslag 2020.”Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/sites/default/files/atoms/files/ap_jaarverslag_2020.pdf.

- Dutch DPA. n.d.-f. “Klacht Melden bij de AP.” Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/nl/zelf-doen/gebruik-uw-privacyrechten/klacht-melden-bij-de-ap.

- Dutch Minister for Legal Protection. 2020. “Kamerstukken II 25268 en 32761, nr. 192.” Overheid. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-25268-192.html.

- Dutch Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport. 2020. “Kamerstukken II 27529, nr. 2018.” Overheid. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-27529-218.html.

- Dutch National Ombudsman. 2021. “Voor een Dichte Deur. Een Onderzoek Naar hoe de Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens Omgaat met Ongenoegen van Burgers Over de Behandeling van Privacyklachten.” Nationale Ombudsman. https://www.nationaleombudsman.nl/system/files/bijlage/Nationale%20ombudsman%20-%20Rapport%20Autoriteit%20Persoonsgegevens%20Voor%20een%20dichte%20deur.pdf.

- EDPB. 2017a. “Guidelines on Personal data breach notification under Regulation 2016/679 Under Regulation 2016/679.” EDPB. https://edpb.europa.eu/our-work-tools/our-documents/guidelines/guidelines-personal-data-breach-notification-under_en.

- EDPB. 2017b. “Guidelines on the Application and Setting of Administrative Fines for the Purposes of the Regulation 2016/679.” EDPB. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/article29/items/611237.

- EDPB. 2020. “Guidelines 4/2019 on Article 25 Data Protection by Design and by Default. “EDPB. https://edpb.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/file1/edpb_guidelines_201904_dataprotection_by_design_and_by_default_v2.0_en.pdf.

- Erdos, David. 2022. Towards Effective Supervisory Oversight? Analysing UK Regulatory Enforcement of Data Protection and Electronic Privacy Rights and the Government’s Statutory Reform Plans. University of Cambridge Faculty of Law Research. pp. 1-37. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4284602.

- European Parliament. 2021. “European Parliament Resolution of 25 March 2021 on the Commission Evaluation Report on the Implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation two Years After its Application (OJ 2021, C 494/132).” European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/NL/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2021:494:FULL&from=EN.

- European Parliament and of the Council. 2021. Commission Implementing Decision of 28.6.2021 Pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Adequate Protection of Personal Data by the United Kingdom. European Union. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dec_impl/2021/1772/oj.

- Hewson, Vicoria, and James Tumbridge. 2020. Who Regulates the Regulator? No. 1: The Information Commissioners Office. London: IEA. https://iea.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Who-regulates-the-regulators_.pdf.

- Hijmans, Hielke. 2020a. “Chapter VI Independent Supervisory Authorities (Articles 51–59): Article 51. Supervisory Authority.” In The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): A Commentary, edited by Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave, and Christopher A. Docksey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hijmans, Hielke. 2020b. “Chapter VI Independent Supervisory Authorities (Articles 51–59): Article 57. Tasks.” In The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): A Commentary, edited by Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave, and Christopher A. Docksey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hof, Jessica P., and Petra A. T. Oden. 2023. “Inbreuken op Data Protection by Design in de Zorgsector. Leidt Handhaving tot Verbetering van EHealth?” Nederlands Juristenblad 676: 770–778.

- Hooghiemstra, Theo F. M., and Sjaak Nouwt. 2020. SDU Commentaar AVG: Editie 2020. Den Haag: Sdu.

- IGJ and Dutch DPA. 2021. “Eerstelijn moet visie ontwikkelen op gebruik e-health.” Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/sites/default/files/atoms/files/factsheet_e-health.pdf.

- IMD. n.d. “IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking 2022.” IMD. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://imd.cld.bz/Digital-Ranking-2022/18/.

- Killock, Jim. 2020. “Parliament must hold the ICO to account.” ORG. https://www.openrightsgroup.org/blog/parliament-must-hold-the-ico-to-account/.

- KPMG. 2020. “Onderzoek taken en financiële middelen bij AP.” Rijksoverheid. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2020/11/19/tk-bijlage-eindrapportage-kpmg-20201102.

- NDG. n.d. “About us.” Government. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/national-data-guardian/about.

- NEN. n.d. “NEN 7510: Informatiebeveiliging in de Zorg: Alles Over NEN 7510.” NEN. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.nen.nl/zorg-welzijn/ict-in-de-zorg/informatiebeveiliging-in-de-zorg.

- NHS Digital. 2022. “Data Security Standard 4 - Managing data access.” NHS Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/cyber-and-data-security/guidance-and-assurance/data-security-and-protection-toolkit-assessment-guides/guide-4-managing-data-access.

- NHS Digital. n.d.-b. “Data Security and Protection Toolkit assessment guides.” NHS Digital. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://digital.nhs.uk/cyber-and-data-security/guidance-and-assurance/data-security-and-protection-toolkit-assessment-guides.

- NHS. n.d.-a. “Data Security and Protection Toolkit.” NHS. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.dsptoolkit.nhs.uk/.

- Oderkirk, Jillian. 2021. OECD Health Working Papers No. 127 Survey Results: National Health Data Infrastructure and Governance. OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/55d24b5d-en.pdf?expires=1686819610&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=3D33A6331FB45D998E482CED5A464CB2.

- OECD. n.d. Digital Health. Proportion of Primary Care Physician Offices Using Electronic Medical Records, 2012 and 2021. OECD. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/08cffda7-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/08cffda7-en.

- ONS. n.d. “Population Estimates.” ONS. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates.

- Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman. 2021. “Complaints to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman, 2019-20 and 2020-21.” Ombudsman. https://www.ombudsman.org.uk/publications/complaints-parliamentary-and-health-service-ombudsman-2019-20-and-2020-21.

- Santifort, Robbert P. 2019. “Naar een Meer Genuanceerde Benadering van ‘Pseudonimisering’ in het Privacyrecht.” Privacy & Informatie 5: 195–204.

- Socha-Dietrich, Karolina. 2021. OECD Health Working Papers No. 129. Empowering the Health Workforce to Make the Most of the Digital Revolution. OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/37ff0eaa-en.pdf?expires=1686819408&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=BE4B34CFBC55095228A0DC9B6FF60624.

- Tosoni, Luca. 2020. “Chapter I General Provisions (Articles 1–4): Article 4(12). Personal Data Breach.” In The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): A Commentary, edited by Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave, and Christopher A. Docksey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tosoni, Luca. 2021. “Chapter I - General Provisions: Article 4(12). Personal Data Breach.” In The EU General Data Protection Regulation: A Commentary. Update of Selected Articles, edited by Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave, and Christopher A. Docksey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- UK’s Department of Health & Social Care. 2022. Policy Paper. A Plan for Digital Health and Social Care. Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care.

- UK’s ICO. 2020. Information Commissioner’s Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019-20. ICO. https://ico.org.uk/media/about-the-ico/documents/2618021/annual-report-2019-20-v83-certified.pdf.

- UK’s ICO. 2021. Information Commissioner’s Annual Report and Financial Statements 2020-21. ICO. https://ico.org.uk/media/about-the-ico/documents/2620166/hc-354-information-commissioners-ara-2020-21.pdf.

- UK’s ICO. 2022a. How the ICO enforces: a new strategic approach to regulatory action. ICO. https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/media-centre/news-and-blogs/2022/11/how-the-ico-enforces-a-new-strategic-approach-to-regulatory-action/.

- UK’s ICO. 2022b. John Edwards’ speech introducing ICO25. ICO. https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/media-centre/news-and-blogs/2022/07/john-edwards-speech-introducing-ico25/.

- UK’s ICO. 2022c. New UK Information Commissioner begins term. ICO. https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/media-centre/news-and-blogs/2022/01/new-uk-information-commissioner-begins-term/.

- UK’s ICO. n.d.-a. Advice services for large businesses and organisations. ICO. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://ico.org.uk/global/contact-us/contact-us-large-organisation/contact-us-organisation-advice/.

- UK’s ICO. n.d.-b. Annual reports. ICO. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/our-information/annual-reports/.

- UK’s ICO. n.d.-c. Enforcement action. ICO. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://ico.org.uk/action-weve-taken/enforcement/.

- UK’s ICO. n.d.-d. DRAFT Statutory guidance on our regulatory action. ICO. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://ico.org.uk/media/about-the-ico/consultations/2618333/ico-draft-statutory-guidance.pdf.

- UK’s ICO. n.d.-e. Get help and support from the ICO. ICO. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/sme-web-hub/contact-us-sme/.

- UK’s ICO. n.d.-f. “ICO25. Revise Approach for Public Sector Fines and Enforcement.” ICO. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/our-information/our-strategies-and-plans/ico25-strategic-plan/annual-action-plan-october-2022-october-2023/empower-responsible-innovation-and-sustainable-economic-growth/.

- UK’s ICO. n.d.-g. Regulatory Action Policy. ICO. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://ico.org.uk/media/about-the-ico/documents/2259467/regulatory-action-policy.pdf.

- UK’s ICO. n.d.-h. Responses to the ICO's Consultation on the ICO25 Plan. ICO. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/responses-to-the-icos-consultation-on-the-ico25-plan/.

- Winter, Heinrich, Thijs Drouen, Marlies van Eck, Lisanne Kramer, Bieuwe Geertsema, Jeanne Cazemier, and Chantal Ridderbos-Hovingh. 2022. “Onderzoek Voor het WODC.” In Bescherming Gegeven? Evaluatie UAVG, Meldplicht Datalekken en de Boetebevoegdheid. Groningen: Pro Facto. https://www.pro-facto.nl/images/Bescherming_gegeven_-_Evaluatie_UAVG_meldplicht_datalekken_en_boetebevoegdheid.pdf.