Abstract

Training students to detect and address spatial inequities is a priority for many educators of urban design. Yet cultivating an ethos of care in the studio is particularly challenging when focusing on foreign cities, a trend that internationalisation pressures in higher education continue to encourage. Is there a theoretical framework that can support teachers in instructing justice-centred studios abroad? This paper examines authenticity as one such possible framework. Interpreting authenticity as a socially constructed lens that forges people's ideas of what is real and what is fake, the AuthentiCITY studio was held at the Liverpool School of Architecture and focused on Venice. Students were encouraged to explore how constructions of ‘the authentic’ contribute to the oppression of marginalised people and to propose urbanisms that could assist those people in removing barriers to their self-empowerment. Interviews with students and analyses of their projects reveal that authenticity can facilitate three progressive steps of inquiry: theoretical (increasing students’ awareness of spatial injustices), programmatic (pointing to critical themes and sites of intervention), and practice-oriented (forming students’ willingness to deploy design as a force for social change in the future). At the same time, however, methodological shortcomings, employability pressures, and aestheticising trends have estranged some students, reproducing privileges in the classroom. The paper concludes by suggesting authenticity as a valid ally for theoretically framing studios abroad, especially in cities suffering from over-tourism. At the same time, recommendations are made for instructors to always interrogate their methods, share vulnerability with students, and counter hidden curricula of exclusion.

Introduction

A city's form determines the kinds of services and opportunities people can — or cannot — access. In cities across the globe, built environments reproduce uneven relations of power, oppressing people along intersecting constructions of class, race, gender, age, body ability, and other vectors of discrimination. The days when architects and planners thought they could fix these issues through their work are over; most scholars now agree that urban design alone cannot solve systemic injustices. But while the limits of design are clear, a consensus is emerging among researchers that the transformation of built environments can, and should, assist oppressed groups in countering exclusion.Footnote1

Theorists and academics have urged professionals to embrace the always-political implications of design, putting their knowledge at the service of underserved people and supporting them in using or transforming spaces. Architects and planners have responded to this call, and perhaps more critically than scholars tend to concede.Footnote2 A justice-centred approach, however, has yet to impact the ways most professionals operate on the ground. May they flout the socio-political ramifications of their work, seek profit to survive in the creative industry, or engage in ‘bottom-up’ initiatives that end up reproducing inequities, architects and planners often become complicit in perpetuating, rather than erasing, spatial discriminations.Footnote3

Pedagogy can provide a critical means for reducing the tensions between justice-centred theories and market-driven practices of urban design. While socially engaged pedagogies are not new to design educators, growing inequities have reinvigorated efforts for justice-centred curricula.Footnote4 In this context, studios, the cornerstone of urban design education, have received attention as privileged laboratories for imagining more equitable urbanisms.Footnote5 In most cases, educators know well that highlighting entanglements of design and power in the studio is not nearly enough — advancing spatial justice requires dismantling asymmetric relations of power with deep roots, overturning physical and social orders that oppress people. Such a systemic restructuring must involve many more actors than designers alone, and pedagogical efforts can only contribute a small bit.Footnote6

With these limitations in mind, but determined to play their part in shaping more equitable futures, instructors have tried to cultivate ‘a capacity of care’ in the studio, exposing students to their social and political responsibilities as future professionals, and encouraging them to prioritise questions of justice. In Europe and North America, instructors have for example pushed students to address the needs of diasporic communities, accommodate informal practices, assist residents in post-disaster contexts, support memorialisations of contested pasts, and engage with non-human agents of ecological design.Footnote7

Foregrounding an agenda for justice in the studio is particularly challenging when focusing on cities abroad. A legacy of colonial dispossession looms over design education as a whole. Throughout the twentieth century, western powers standardised pedagogies in occupied territories in order to displace indigenous forms of knowledge. Academics from Europe and North America went teaching abroad ignoring local expertise, and students who travelled from developing countries to enrol in schools of the global west found no courses addressing challenges familiar to them.Footnote8 These old colonial tendencies have now taken new forms asneoliberal trends in higher education and pressures for internationalisation push schools to organise studios in distant places. It is often teachers and pupils from rich countries who visit — helicopter in — poorer contexts, fascinated by vernacular architectures and willing to ‘save’ ‘poor people.’Footnote9 Challenges persist even when instructors work hard to redress these power asymmetries. If issues related to brief engagement with communities are not alien to domestic courses, in the case of studios abroad, scarce familiarity with the context, restricted time, and linguistic barriers can further limit opportunities for students and instructors to centre locals’ needs.Footnote10

Yet studios abroad are not retiring any soon. If anything, trends in higher education will likely make them more central to architectural and planning curricula. These circumstances make it necessary for educators to find strategies for advancing a justice-centred agenda amidst the challenges of studying a city from afar. Is there a theoretical framework that can support this mission?

This paper reflects on an urban design studio that proposed authenticity as a framework to both study a distant city and try to address its inequities. Authenticity is an elusive concept to say the least. Scholars have tried to pin down what authenticity is — and what it does to how we use space — for decades, and have come to the conclusion that authenticity is best described as the socially constructed framework through which people negotiate ideas of what is real and what is fake. Even if different people perceive their surroundings differently, the socio-political context in which they live gives them a shared lens to distinguish between an ‘authentic’ thing, which usually retains positive associations, and a false one. Scholars have proved that the construct of authenticity forges social and physical environments, and have connected these processes to urban injustices. At times, constructions of consumable, authentic spaces facilitate the exclusion of underprivileged people, while at other times, it is oppressed groups who mobilise authenticity to claim legitimacy.Footnote11

While the spatial politics of authenticity have been exposed, we still need to understand how designers can use these politics to support underserved communities in shaping their own places. The AuthentiCITY design studio addressed this matter by focusing on Venice, a city where ideas of real and fake greatly impact people's lives. Through seminars, a one-week trip to Venice, and the development of design proposals, eleven students deployed a spatial lens of authenticity to understand, and possibly ease, spatial injustices.

After reviewing debates on the spatial politics of authenticity, the paper reflects on the successes and shortcomings of the studio. I draw from conversations, questionnaires, and interviews with students. All in all, the lens of authenticity proved to be fruitful from a theoretical standpoint (increasing students’ awareness of spatial discriminations), a programmatic one (pointing to critical themes and sites of intervention), and from a practice-oriented perspective (forming students’ willingness to deploy design as a force for social change in the future). At the same time, methodological shortcomings, employability pressures, and aestheticising trends reproduced privileges in the classroom, impinging the emancipatory aspects of the studio. Building on this experience, the paper concludes by acknowledging the validity of authenticity as a framework for engaged pedagogies while recommending educators to always interrogate their methods, share vulnerability with students, and fight ‘hidden curricula’ of exclusion.

Why authenticity?

Judgements on what is real and what is fake are subjective. Each of us may have different opinions about what objects or experiences we understand as authentic. Yet scholars have demonstrated that these opinions are influenced by values that we tend to perceive as objective: we decide what is real and what is fake based on the society we live in. This helps explain why commonly shared perceptions of authenticity have changed over time. At the onset of the twentieth century, when mechanical reproduction allowed copying items with unprecedented quantity and precision, thinkers like Walter Benjamin warned against what they thought would be a loss of authenticity in the modern world.Footnote12 Their view of a copy is always pejorative of the original informed western-centric preservation practices that continue to be prevalent today.Footnote13 In cultural studies, more relativist approaches to authenticity emerged through time. In the 1980s, scholars defined authenticity as a social construct, a culturally forged framework that powerful actors use to invent traditions, commodify history, and de-politicise everyday struggles.Footnote14 This premise has grounded recent explorations of authenticity and its links with capital accumulation. Wanting to feel ‘real’ in an era of shifting belongings, scholars have shown, the people pursue authenticity by, for instance, visiting historic places, tasting ethnic cuisines, or purchasing vintage objects.Footnote15

In other words, authenticity moves people and money around the world. And, importantly here, authenticity concretely impacts how cities look and function. Sharon Zukin was among the first to highlight authenticity as a force of urban exclusion. Competing in the global arena, Zukin argued, city administrators and developers brand places with the kinds of authentic buildings, signs, and sounds that people expect to see.Footnote16 These fabrications enable the exclusion of marginalised groups in multiple ways. Historic neighbourhoods are transformed to lure new affluent residents while neglecting the needs of old ones.Footnote17 Touristic and financial districts are maintained to banish ‘inauthentic’ users who conduct ‘inappropriate’ activities such as street vending or begging. Authenticity constructs also enable racist exclusion, for example, when patrolmen remove vendors of colour from historic downtowns, or when immigrant business owners feel compelled to perform stereotyped, ‘authentic’ versions of their culture in order to attract clients.Footnote18

Architects and planners are often complicit in using authenticity as a force of exclusion, for example, when preserving historic sites. If we know that places can become authentic in the beholder's eyes, we also know that, by conveying the history of a specific group as authentic and erasing that of others, built environments inevitably contribute to the normalisation of understandings of who belongs, and who does not belong, into a society. Preservationists end up reproducing exclusionary constructions of belonging, for example, when they selectively reconstruct historic sites after traumatic events (as it happened in post-earthquake Lijiang, China) or conceal the memories of marginalised people from the built environment (as in the US South, where African American people often see the traces of their history made invisible).Footnote19

The production of new, authentic spaces can exclude people as much as the conservation of old ones. While scholars have long argued that themed urbanisms amplify social and spatial inequities, the recent spread of large-scale ‘simulacrascapes’ has reignited these concerns.Footnote20 In rapidly urbanising regions such as China, gated communities that evoke authentic (preferably western) atmospheres spatialise the imperatives of capital accumulation and forward its exclusionary consequences. At the same time, commodified ethnic and indigenous neighbourhoods in the global west essentialise the authenticity of minoritised groups while masking their systemic oppression.Footnote21

Well-meaning, ‘tactical’ interventions can equally end up excluding on the basis of a perceived authenticity. Aimed to redistribute power and centre the voices of otherwise ignored city residents, short-term, participatory transformations of space have gained immense popularity over the past two decades. Yet, tactical urbanisms, and the rhetoric of authenticity that often lies within them, can easily end up reinforcing exactly the same injustices that designers wish to contest. This occurred, for instance, when celebrity street-artists were hired to decorate redeveloping areas of Detroit; when across the United States ‘gourmet’ farmers markets increased property values, displacing less trendy street vendors; or when archi-stars attempt to revive ‘dead’ public spaces across the globe by creating ‘feel-good urbanisms’ geared towards urban elites.Footnote22

Authenticity, however, is more than a ubiquitous dispositive of oppression. While scholars have primarily focused on how authenticity causes exclusion, some have analysed how underserved communities utilise ideas of ‘the authentic’ to claim legitimacy. At times, oppressed groups mobilise authenticity to negotiate a sense of place. Following an earthquake in South Taiwan, relocated residents decorated their new homes with stereotypical features of destroyed urban fabrics, constructing belonging amidst displacement.Footnote23 And, while theming generally contribute to exclusion, Erica Lehrer found that the Jewish visitors of Crakow's ghetto appreciated its stereotyped features which they believed help keep memories of persecution alive.Footnote24 At other times, marginalised people weaponise the politics of authenticity to fight exclusion, as it often happens in gentrifying neighbourhoods. When older residents in Vancouver's Chinatown advocated for preserving community-owned buildings, for instance, they used stereotypical assumptions of their culture for their own interests.Footnote25

People also counter power through ordinary, but nonetheless political, uses of authenticity. By performing ‘authentic’ rituals for tourists, for example, Mosuo residents of the Loku Lake in China implicitly redress uneven power relationships.Footnote26 In a British-themed village near Shanghai, migrant workers and low-income tourists occupy public spaces to perform Britishness and feel ‘at home’ against the will of affluent residents.Footnote27 When African street vendors sell ‘ethnic’ gadgets in Italian touristic centres, they exploit racialised constructions of authenticity and capitalise on their own visibility as Others.Footnote28

A lens for justice?

This scholarship demonstrates the enduring ambiguity and contradictory nature of authenticity. Whether we seek it in the places we visit or in the food we eat, authenticity remains multifaceted. The set of values conveyed by what we perceive as authentic can be used by powerful actors to perpetuate spatial injustice. The same set, however, can also be a framework that marginalised communities mobilise to assert their right to use and produce space. The AuthentiCITY studio intended to grapple with all of these contradictions. Building on the appeal that authenticity has on most people, which thrives on the very ambivalence of the term, the studio sought to equip students with an accessible lens to detect and address spatial discrimination.

The spatial politics of authenticity are particularly apparent in a city like Venice. The reader may be familiar with photographs of six-story cruise ships on the backdrop of the Grand Canal, of tourists bathing in the San Marco Square during high waters, or of the Rialto Bridge overwhelmed by selfie-taking people. These are only spectacular signs of a capillary touristification that began in the 1980s, when administrators and marketeers started targeting visitors’ needs at the expense of long-term residents. Defunding of public services, uncontrolled conversions of housing into short-term rentals, and privatisations have decimated permanent populations by two-thirds in four decades. And while long-standing communities see beloved services and businesses disappear, some thirteen million tourists every year can easily purchase cheap memorabilia in the mushrooming souvenir shops.Footnote29

Like other historic cities affected by over-tourism, then, Venice owes its economic survival to the ‘authentic’, iconic landscapes that people travel to visit. But that same authenticity makes life hard for those who cannot keep up with touristification — e.g. older residents, low earners, precariously housed, and migrants. Against this backdrop, the AuthentiCITY studio examined how ideas of the authentic shape Venice's landscapes and explored how designers can assist underserved residents in countering exclusion by using authenticity.

AuthentiCITY was one of five tracks of the larger M.Arch.4 studio titled ‘Venice: Contested Terrains’, a required course that involved 51 students and was held right before the COVID pandemic, in the fall of 2019. The M.Arch.4 Program at Liverpool has a tradition of focusing on a foreign city, which is highly encouraged by the University's internationalisation policies. As studio teachers, we had little choice but to follow this tradition, even if we were fully aware of the challenges associated with it. These circumstances exemplify the challenges exposed above, showing why it is critical for educators to elaborate strategies for advancing a justice-centred agenda in studios abroad.

Beyond tutorials, the M.Arch.4 studio included weekly lectures, a trip to Venice in week 4, and reviews with external examiners in weeks 6 and 12. Following the trip, students were first asked to produce a group critical response in the form of artifacts, video installations, collages, and the like. Each student then developed an individual project inclusive of a digital portfolio, a physical model, as well as canonical architectural drawings (plans, sections, and axonometries).Footnote30 AuthentiCITY was selected by eleven students who distributed across three pathways of spatial inquiry: (1) trespassing — asking how symbolic boundaries between real and fake help exclude ‘out of place’ users; (2) inhabiting — asking who are the people who inhabit Venice, and what are their needs; and (3) marketing — asking who has the right to profit from the image of Venice. Once students chose a pathway, they then decide on their focus area in Venice (either the historic island or Mestre).

AuthentiCITY was the only M.Arch.4 track that centred questions of justice. Given this focus, readings on ethnographic research and its ethical implications were assigned in the weeks preceding the field trip. Particular attention was given to rapid spatial ethnography, explaining techniques of engagement and discussing consent.Footnote31 As a preparatory exercise, in week two each student was tasked with finding an area of Liverpool where tensions around different ideas of authenticity existed, conducting spatial observations, informally chatting with people, and reporting in class through a short presentation. Students chose a variety of cases from the Anglican and Catholic cathedrals competing for their religious authority in the city, to diverse East Asian entrepreneurs marketing their ‘Chinese’ restaurants, to preservationists fighting developers against the demolition of historic buildings.Footnote32

While familiarising students with spatial ethnography, this training intended to avoid falling into two familiar traps of justice-centred studios. One refers to treating the equity lens as a fashionable or obligatory add-on which, just as it happens with other concepts like sustainability, is interpreted by students as a ‘must’ of the project addressed through aesthetic stratagems rather than as a thought-provoking framework for understanding how architects reproduce injustice. Relatedly, and particularly relevant to studios abroad, the second trap we wished to avoid was ‘design tourism’, an approach too often taken by students of privileged countries who travel to ‘poor’ areas, fetishise ‘authentic’ Others, and dream of fixing their lives.Footnote33

Once in Venice, through several lectures at the IUAV university, M.Arch.4 students met academics, city authorities, and environmental activists. In addition to these year-wide activities, I took the AuthentiCITY students to public meetings with housing advocates, an association defending immigrants’ rights, and a collective of artists, letting students chat with different activists and residents. Of course, as I explain below, these experiences could not overcome the brevity of the trip or language barriers. Yet they offered meaningful opportunities for encounter, complicating students’ assumptions and prompting projects based on residents’ needs.

What follows reflects on the AuthentiCITY studio by analysing students’ perceptions and work across the trespassing, inhabiting, and marketing sub-tracks. It is perhaps relevant to mention that this paper was not conceived a priori before the semester. It rather emerged frominformal conversations with students (quick chats in the corridors, during the fieldtrip, or at the end of class) that made me interested in exploring the effects of AuthentiCITY in more depth. Questionnaires, distributed in week eight of the semester and returned to me after final marks were submitted (week 14), included a mix of Likert-scale and open-ended questions asking opinions on the studio (satisfaction with the topic, the methods, and the tutor's approach). I held interviews after students received their final grades. Lasting 30 to 45 min, interviews took place in the school, cafes, or online. The scripts included five parts, investigating: why students chose the AuthentiCITY track; whether they were interested in justice questions (before and after the course); which aspects they thought worked in the studio; which limitations they found; and their professional plans for the future. A sixth, optional part asked students about their demographic and economic background. My role as the students’ instructor made relationships with respondents inherently hierarchical. If questionnaires enabled students to openly express their opinions, the same freedom might not have been perceived during interviews. At the same time, the range of students’ answers, including vivid critiques to both the studio and the instructor, suggests that interviewees tended to trust me with disclosing their opinions.

Increasing awareness

Most students joined AuthentiCITY without a particular interest in questions of justice, but because of a general intrigue on urban fakes. The lens of authenticity helped reverse this proportion. The syllabus assigned readings on both authenticity and spatial justice in the weeks leading up to the fieldtrip. The immediacy of concepts, such as real and fake, helped clarify entanglements of design and power: ‘I knew lots of people want authentic stuff, but it never occurred to me space is involved in that’, a student said on the first day of class; ‘and power is involved, too’, added another. In week two, each student was asked to associate a chosen reading to a place in Liverpool, considering how authenticity manifested in that space and who benefitted from it. This exercise helped students form groups based on shared interests, and trained them in the rapid ethnography methods they would use in Venice. Class discussions before the trip revealed students’ expectations on what Venice would look like. While some envisioned authentic Venice as the ensemble of multiple famous landmarks, others talked about sharp distinctions between ‘good’ and ‘real’ residents versus ‘bad’ tourists in search of a ‘fake’ Venice.

In Venice, the authenticity framework helped reveal far more complex dynamics than the students expected. If most locals invoked the protection of an ‘authentic’ Venice while talking to the students, what protection meant varied greatly from one person to the other. It became apparent that wealthy residents and administrators used a rhetoric of authenticity to marginalise precariously housed people, migrants, and labourers. Students also realised how built forms very much affect these dynamics. ‘I knew architecture had political implications, but I never thought I would care […] it is only thinking through authenticity that got me thinking through the political’, said a student. ‘Authenticity makes things visible, the more you are told the more you notice’, said another.

Some students experienced the injustices produced by authenticity more profoundly than others. Residents’ racism particularly hit a group of second-generation students in the marketing sub-track who chose to centre their project on Chinese migrants. Through chats with members of the community, students found that immigrants’ needs are systemically subsumed to the aesthetic imperatives of authenticity. Urban codes prevent Chinese shop signs to be ‘ostentatious’ and business owners avoid hiring Chinese migrants because they do not look Italian; additionally, licenses are often denied for ‘Chinese’ businesses such as karaoke bars or massage parlours. Feeling unwelcomed, most Chinese migrants socialise in quasi-private spaces (mostly restaurants), avoiding public spaces in groups.

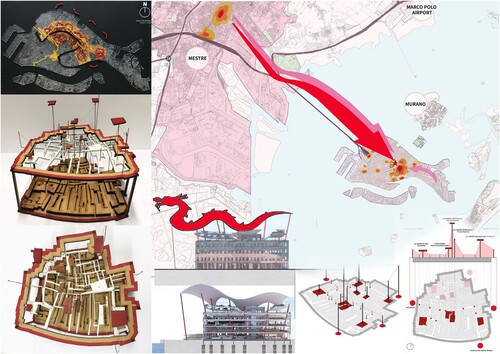

Students sought to reverse this trend by both accommodating the needs of Chinese migrants and making them more visible in space. They proposed a ‘Chinese market’ complete with a dragon-shaped roof. Standing in contrast with tourists’ expectations, the dragon was intended to break canons of authenticity by showing another Venice, one made by its growing, yet obscured Chinese community (). This operation did not assume that making a difference visible would automatically legitimise the Chinese community in the eyes of other city users, or ease discriminations inflicted to migrants through policies and spatial deprivations. Group discussions explored the risks of ethnic branding and acknowledged that members of minoritised groups may wish not to make themselves visible for multiple reasons.Footnote34

Figure 1. An analysis of the spatial practices of Chinese immigrants in Venice and the proposed ‘Chinese’ market with its dragon-shape inspired roof, seeking to disrupt dominant aesthetic canons by inserting a symbol of difference, image and project by Chi-Yao Lin, Kwan Yee Siu, and Tin Shing Tim Tsoi, University of Liverpool, 2019

The dragon-shaped roof was nonetheless questioned by some reviewers as well as by other students of East Asian origins. At the core of this critique was the problematic use of a symbol that reduces the complexity of Chinese culture, a stereotyped element that Chinese people may wish not to associate themselves with. At first, I also considered the dragon shape a superficial call for change which in fact essentialised Otherness. And I agreed when mid-term reviewers suggested that the students were proposing an aesthetic stratagem to avoid thinking about more sophisticated transformations of space.

While acknowledging the validity of these critiques, but the students counterargued that precisely the use of a stereotyped feature like the dragon would make the marginalisation of Chinese migrants known to the world. If symbols such as the gondola were used to market Venice, the students observed, why could another essentialising element not be weaponised to make as many people as possible aware of the injustices faced by Chinese migrants? I am admittedly still puzzled by the students’ point. While I remain convinced that the dragon-shaped roof is problematic, I also understand the argument that inserting an iconic symbol of difference in a city that economically thrives on an essentialised version of itself could tear apart dominant aesthetic canons. In this logic, what the dragon roof could potentially achieve is a kind of transformative representation which, embracing the limits but also the opportunities of symbolism as a political tool, would generate broader processes of recognition, supporting migrants in demanding just treatment.Footnote35

Authenticity gave other students an additional lens to investigate familiar questions. The only student who joined AuthentiCITY with a strong commitment to justice said that thinking through authenticity added a layer to her understanding of urban exclusion. Within the inhabiting theme, the student visited several housing occupations, met with activists, and chatted with residents of short-term shelters. Associating authentic Venice with the social ties of low-income residents, the student focused on serving precariously housed people and imagining a self-constructed housing complex that would provide opportunities to organise ().

Figure 2. Self-constructed housing complexes with collective facilities, image and project by Ioana Bucuroiu, University of Liverpool, 2019

At the end of the studio, most students expressed a deepened understanding of design — one that, thanks to the lens of authenticity, inevitably raised questions on power and justice. This leads to the suggestion that the authenticity framework enabled a transformative pedagogy characterised by progressive engagement — a process ‘where awareness becomes exposure, and exposure translates into active citizenship’.Footnote36 As explained below, part of this progressive engagement made students re-consider designers’ role more broadly.

Reflecting on designers’ role

The justice-oriented agenda of AuthentiCITY prompted reflections on what it means to be an architect. At the beginning of the course, most students saw architects as ‘expert’ protagonists in projects. Between 22 and 25 years old, all students were committed to pursuing a career in architecture and firmly believed that designers could improve people's lives. AuthentiCITY helped re-centre reflections on how designers’ position (often one of privilege) intervenes in shaping spaces. ‘Rather than only thinking about how to do things [, the studio taught me that,] we [architects] should think more about why we do that because we are people ourselves [… Am] I designing things because I want them, or because people really need them that way?’, remarked a student.

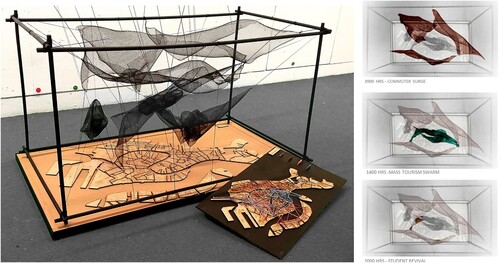

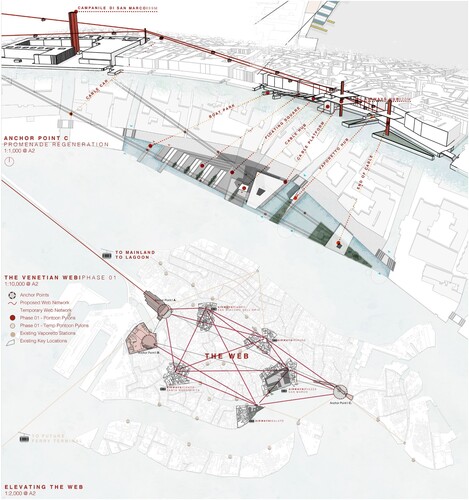

Questioning the role of designers led some students to interrogate their own purpose and impact. ‘At some point in the trip, I realised that I was thinking about my own expectations [of authentic Venice] before listening to what people had to say […] I guess architects do that a lot,’ said a student whose group in the trespassing sub-track interpreted authenticity as a fragile web of mobile relationships that embeds with Venice's urban fabric (). As conversations with locals revealed their frustration with overcrowded transportation infrastructures, another student designed a cable car system crossing above the city and dropping people at key locations (). ‘If I saw this project a few months ago, I would have thought it's crazy [… Would] I like to see cable cars above Venice? Of course not […] you cannot ruin Venice's skyline like that. But it makes sense now […] for residents, moving around is important’, said the student.

Figure 3. A web of social relations and its shifting spatialities during a typical day in Venice, image and project by Lauren Clancy, Emma Hartley, and Kate Johnstone, University of Liverpool, 2019

Figure 4. A suspended transportation system reserved to residents, image and project by Emma Hartley, University of Liverpool, 2019

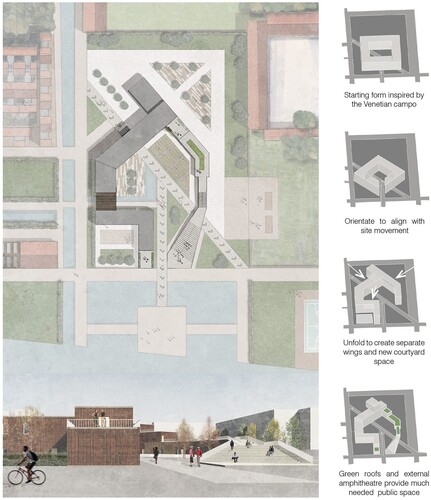

‘Authenticity explains much of what I saw working in practice […] this idea that people want to see certain things in a space […] and architects also do that, they preserve what they think they know it's best’, said a student with a background in preservation. Engaging with the inhabiting theme, the student designed service hubs to enable diverse residents (senior residents, youth, and activists) to remain in their homes, produce food locally, and organise protests (). ‘I would have not seen this as a preservation project a few months ago […] but people in Venice told me the city already had all they needed, they just needed spaces to continue doing what they do […] so my preservation project has become a new infrastructure for old needs.’

Figure 5. Community centre for young people, older residents, and activists, where a diverse range of groups can decide to remain separate or share space, image and project by Tolulope Ogunjimi, University of Liverpool, 2019

Over the course of the semester, then, students changed their perceptions of professional practice. The relation between architecture and the public became understood from ‘one of hierarchy to one of partnership’.Footnote37 The authenticity framework played a pivotal role in this introspection. Students started questioning their design plans when they realised that they were forwarding their own preferences for a ‘real’ Venice. Blurring the distinctions between ‘experts’ and ‘users’ sparked important conversations on the role of trained professionals in facilitating equitable transitions.

To be sure, while we recognise that architects must collaborate with communities to co-produce space, we should also be aware that dismissing the expertise gained through years of study would be detrimental to the profession. As scholars of Design Justice have explained, we should never assume that architects always know better than the general public, but we can concede that their technical knowledge can drive meaningful spatial transformations. What is critical, and what the studio sought to teach, is for architects to detach technical knowledge from the interests of oppressive forces, deploying that knowledge to work in tandem with local communities.Footnote38 These conversations challenged students’ views of designers as inherently entitled to bring their spatial visions to life without meaningful collaborations with communities. Such an awareness, however, constituted only a small step towards a more just praxis of urban design. Some reasons behind this shortcoming are explained below.

Questioning methods, and the instructor

The AuthentiCITY studio also let down students in several ways. In my first year in Liverpool, after moving from Los Angeles, I designed the syllabus with activities I considered ‘standard’ such as writing reading reflections and class debates. Not all students, however, were familiar with those activities. While I showed several examples of reading reflections at the start of the semester, and helped structure debates by asking students to prepare in teams, some students reported being both confused by those activities and unsure on how they would contribute to their design project. Intending to foster a student-centred learning environment, I failed to consider the specificities of the education context, ending up forwarding the same kind of universalising approach I had hoped to complicate.

The emphasis on justice assumed a normative character in the eyes of some students. ‘I am overall happy with my project’, said a student at the end of the course, ‘but at times I felt I had to go in the justice direction [… What] if I wanted to do luxury homes? I don't think you would have been fine with that.’ The studio's focus also estranged a few students who believed the class would not help them succeed in the professional world. Two people reported joining the studio with no interest in tackling inequities and leaving with the same feelings. ‘I am here to design buildings, not to save the world’, a student said, while a questionnaire reported: ‘I didn't like class presentations because people might copy me. As an architect, I will have to convince clients with MY idea. I don't think a “collaborative spirit” can help with that.’ (punctuation in original)Footnote39

Invertedly then, I established the justice-centred agenda of the studio as an inflexible paradigm. One may object that, being AuthentiCITY focused on questions of justice, students should have been restricted from pursuing non-related topics such as luxury housing. Indeed, educators cannot endlessly chase students’ preferences and clear course objectives are necessary. As mentioned however, most students joined AuthentiCITY due to their interest in urban fakes rather than in spatial justice. These circumstances prompted me to prioritise involving students in socially engaged conversations rather than imposing a rigid thematic agenda. Authenticity played an important role in attracting students and exposing them to debates that they would have hardly participated in otherwise. While such an approach aligned with critical pedagogies that ‘privilege persuasion over dialogue’, the testimonies of students who felt compelled to please my expectations reveal that the justice framework was still rigidly present in the classroom.Footnote40

Some students became frustrated with the elusiveness of authenticity as a concept. Authenticity was criticised as inadequate to address environmental challenges. ‘Authenticity is useful to get the social side of things, but it's kind of useless to look at climate change issues’, said a student, while another said: ‘[My] project was all about environmental impacts [… Authenticity] had nothing to do with that.’ To some extent, these critiques highlight the limits of the authenticity lens, which might indeed help capturing patterns of social exclusion better than question of environmental justice. But students’ comments also reveal how I avoided engaging with less familiar, environmental justice questions. This avoidance reveals my own failure in honouring critical pedagogy principles which require educators to embrace the limits of their expertise, sharing vulnerability in the classroom.Footnote41

Exposing broader challenges

Other shortcomings of AuthentiCITY reveal challenges that permeate design education more broadly. Several issues emerged out of the studio's ‘hidden curriculum’, or the set of unstated norms that condition the behaviours and expectations of studio's participants.Footnote42 AuthentiCITY might not have run the risks of other courses where students from privileged countries visit less privileged ones. Yet the focus on a foreign city (hardly avoidable to instructors because strongly encouraged by the University) enabled some problematic aspects of design tourism. All AuthentiCITY's students joined the trip, but this was not the case for four members of the larger M.Arch. cohort who could not afford the trip or leave the country because of visa issues. Obviously, not participating in the trip did not preclude students’ success in the studio; two of their projects were among the most highly graded across the year. Yet, it is undeniable that going abroad reproduced privileges within the student body.

The fact that students who did not participate in the trip produced equally valid, and at times better, projects than those who went to Venice ignites further questions on the necessity to travel abroad in the first place. While those students were in M.Arch.4 sub-tracks not as concerned with social aspects as AuthentiCITY was, we can fairly assume that focusing on our own city would have led my students to even more meaningful explorations. As mentioned, through the preparatory exercise preceding the trip, students found a wide range of possible projects related to authenticity in Liverpool. Exploring those projects would have perhaps avoided the lack of deep engagement with local people that inevitably characterised AuthentiCITY. Indeed, neither the good intentions of the studio nor the training in spatial ethnography could make up for the brevity of our stay, students’ lack of familiarity with Venice, and language barriers. While firmly based on field observations, conversations with locals, and scientific literature, students’ projects in Venice were still based on assumptions that a longer involvement with locals might have complicated or even reveal incorrect.

Aestheticising trends also conditioned students’ final outcomes. Toward the end of the semester, anxieties over employability pushed students and instructors alike to prioritise the aesthetic qualities of projects. Preparing a compelling portfolio of works to compete in the job market was a priority for most students, and one reinforced during midterm and final reviews. Responding to these dynamics, tutorials over the end of the studio became increasingly focused on how to represent projects, at the cost of reducing its social impacts. This happened, for example, when a student eliminated social housing units to make their project ‘overall more balanced’, or when another student took away facilities for older residents because they ‘looked bad’ in the 3D model.

Finally, while most students left the studio with heightened awareness of justice-related issues, only those from financially secure backgrounds expressed the intention to pursue justice-oriented careers. Others mentioned that they would hardly even try to work in engaged architectural firms due to low-paying jobs. This dilemma was particularly acute for students intending to remain in Liverpool, where the scarcity of small practices dedicated to social change translates to unstable contracts for recent graduates. AuthentiCITY invertedly reinforced trends in the practice world, where socially engaged explorations become an exclusive prerogative of established firms.Footnote43

Conclusions: lessons learned (and work to do)

Centring an ethos of care in urban design studios becomes particularly challenging when courses focus on cities abroad. Factors such as lack of familiarity with the context, language barriers, and time constraints make meaningful engagements with local people and places even harder than in domestic courses. Despite these hurdles, pressures for internationalisation, which one may see as a new iteration of colonial traditions in design pedagogy, continue to make studios abroad foundational to brand programs and attract students. For educators committed to forwarding design as a force for social change, finding ways for addressing the challenges of international studios becomes critical.

Is there a theoretical framework that can help educators navigate the difficulties of studios abroad? This paper examined the concept of authenticity as one such possible framework, utilising a studio focusing on Venice as a case study. Held at the University of Liverpool, the studio embraced the ambiguities imminent to the concept of authenticity in order to make students aware of the socio-political aspects of design. AuthentiCITY explored how constructions of authentic landscapes help exclude people in Venice, and how these people in turn mobilise authenticity to fight exclusion. Through readings, discussions, a fieldtrip to Venice, and the development of a design project, students proposed spatial transformations that could assist different communities in occupying and transforming the city (e.g. centring the needs of older residents, migrants, and precariously housed people).

The experience of the studio validates authenticity as a paradigm that can increase students’ awareness, providing a swift entry-point for understanding and addressing inequities in a distant city. Specifically, authenticity indicates three progressive steps of inquiry. The first is theoretical: as shown in the case of Venice, the immediacy of ‘real’ and ‘fake’ concepts attracted students to the studio and exposed them to entanglements of design and power. The second step is programmatic. Indeed, once students familiarised themselves with design justice discussions, authenticity enabled them to quickly grasp concrete issues and find areas of intervention in Venice. While other studios could have centred the needs of traditionally oppressed groups, authenticity helped individuate specific problems, providing a useful framework for engaging with local people and spaces. The third and final step of inquiry is practice-oriented. Reflecting on how they unintentionally promoted their own ideas of an ‘authentic’ Venice, students began to interrogate architects’ position in design processes and some expressed the will to build a career in critical design practice.

In addition to prompting theoretical, programmatic, and practice-oriented knowledge, a lens of authenticity helped make some problems evident. When the studio's emphasis on justice gained a normative character in the eyes of a few students, authenticity helped them voice their frustration. Other students felt that the authenticity lens did not give enough attention to environmental sustainability (although, admittedly, lack of emphasis on those topics primarily reflected the instructor's expertise), and the elusiveness of the authenticity concept helped illustrate their point.

To be sure, authenticity is not proposed here for instilling a critical ethos in every studio. Finding a universalising framework for advancing design justice would contradict critical pedagogies, and would simply be impossible. And the studio in Venice could not be repeated identically in any case. What the experience analysed here suggests, however, is that authenticity can be deployed for understanding a city from afar, in particular a historic city suffering with over-tourism, as well as other, nearer locations where ideas of real and fake impact people's lives. In these regards, AuthentiCITY's three categories of trespassing (how do symbolic boundaries between real and fake help exclude ‘out of place’ users of space?), inhabiting (who are the long-standing communities who inhabit a city, and what are their needs?), and marketing (who has the right to profit from the image of iconic cities?) could be useful to structure fruitful explorations.

Nor did authenticity prove able to solve broader challenges faced by design instructors in higher education. The case of Venice showed, for instance, that only students with privileged backgrounds are likely to seek jobs in socially engaged (but low-paying) design firms after graduating; that fieldtrips abroad reproduce distinctions between those who can travel and those who cannot; and that employability pressures push for ‘beautiful’ projects at the cost of reducing their social impact. These challenges have no easy solutions. But AuthentiCITY indicates three pathways for educators to navigate them more carefully. First, Interrogate Methods. Instead of treating the justice framework as an orthodoxy, instructors could begin by proposing traditional exercises and incrementally engage students in experimentation. They could offer alternative routes for students uninterested in justice-seeking explorations, fostering dialogue over persuasion. Second, Embrace Vulnerability. Teachers must resist staying within disciplinary comfort zones. Exposing the situatedness of their knowledge would help educators normalise doubt as vital to design processes. Finally, Beware of Hidden Curricula of Exclusion. there are practical steps that instructors can take to create a more equitable learning environment. Differential funding, rare in the European context, would make opportunities such as trips abroad available to more students. Moreover, rather than demanding only ‘finished’ design projects, tutors could prioritise ideas over their representation (which is often linked to a student's technological means and ability to spend time).

Authenticity is far from a ready-made solution to the challenges of studios abroad. It remains an ambivalent — and at times contradictory — concept that different people may interpret differently. What the case discussed here shows, however, is that despite (and perhaps because of) its multi-layered nature, authenticity can help tutors introduce a level of analysis that students may not encounter otherwise. Embracing the ambiguities of authenticity, educators can transform students’ approach to design from a theoretical, programmatic, and practice-oriented perspective. A whole range of other challenges embedded in higher education can hardly be addressed through the notion of authenticity. In this regard, the AuthentiCITY studio points out the need for engaged educators to interrogate their role more critically by sharing vulnerability in the studio and by acknowledging how pedagogies, including justice-centred ones, can reify canons of expertise. Making space for ambiguity in the studio, instructors can foster a culture of engagement towards more equitable cities.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to the students who shared their time and experience with me. I am also very grateful to colleagues at the University of Liverpool (particularly Dr. Aikaterini Antonopoulou who organised the M.Arch.4 Venice Contested Terrains studio) as well as at the IUAV University (particularly Professor Mariachiara Tosi who organised the seminars and lectures in Venice). I am equally grateful to the anonymous reviewers and to Prof. Deljana Iossifova for the insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 For an overview of debates on spatial justice and their applications in urban design, see Kian Goh, Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, and Vinit Mukhija, Just Urban Design: The Struggle for a Public City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2022); Dana Cuff, Architectures of Spatial Justice (MIT Press, 2023); and Francesca Piazzoni, Jocelyn Poe, and Ettore Santi, ‘What Design for Design Justice?’, Journal of Urbanism (2022), 1–22 <https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2022.2074522>.

2 Monika Grubbauer, ‘Postcolonial Urbanism Across Disciplinary Boundaries: Modes of (Dis)engagement Between Urban Theory and Professional Practice’, The Journal of Architecture, 22.4 (2019), 469–86. She explains that urban scholars tend to describe practioners as disinterested in (if not dismissive of) spatial-justice issues, neglecting important steps taken by professionals in advancing critical design practices.

3 The often questionable results of equity seeking design interventions are discussed by Fran Tonkiss, ‘Socialising Design? From Consumption to Production’, City, 21.6 (2017), 872–82.

4 The need for critical approaches to design education are introduce by Jeremy Till in ‘Solidarity and Freedom: Educating for Spatial Practices’ and by Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman in ‘Disruptive Praxix’, both in Spatial Practices: Modes of Action and Engagement with the City, ed. by Melanie Dodd (London: Routledge, 2020).

5 Danilo Palazzo, ‘Pedagogical Traditions’, in Companion to Urban Design, ed. by Tridib Banerjee and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris (London: Routledge, 2011), pp. 61–72. In Danilo Palazzo's review of the evolution of the urban design field since the 1950s, he explains how design studios gained a key role in curricula going hand in hand with the understanding of urban design as a social practice.

6 A special issue in 2016 of the Journal of Urban Design was dedicated to the emergence of new pedagogies in the field. See Carolyn Whitzman ‘“Culture Eats Strategy for Breakfast”: The Powers and Limitations of Urban Design Education’, Journal of Urban Design, 21.5 (2016), 574–6; and Alexander Cuthbert, ‘Emergent Pedagogy or Critical Thinking?’, ibid., 551–4. They explained the necessity for socially-engaged studios while also showing the limitations of urban design (with theories and practices inevitably depending on larger politicla and economic dynamics).

7 For each of these topics, see, respectively, Nadia Anderson, ‘Public Interest Design as Praxis’, Journal of Architectural Education, 68.1 (2014), 16–27; Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Vinit Mukhija, ‘Responding to Informality Through Urban Design Studio Pedagogy’, Journal of Urban Design, 21.5 (2016), 577–95; Kathy Velikov and Geoffrey Thün, ‘Fluid Territories: Cultivating Common Practices Through the Design of Water Redistribution’, Journal of Architectural Education, 74.1 (2020), 92–100; and Bülent Batuman, Deniz Altay Baykan, and Evin Deniz, ‘Encountering the Urban Crisis: The Gezi Event and the Politics of Urban Design’, Journal of Architectural Education, 70.2 (2016), 189–202.

8 Tridib Banerjee, ‘Environmental Design in the Developing World: Some Thoughts on Design Education’, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 5.1 (1985), 28–38. He explains how, when he moved from India to the US to study architecture in the 1960s, he realised that architectural education completely neglected the experiences of students coming form developing countries. For a broader summary of colonial legacies in design education, see Afroza Parvin and Steven Moore, ‘Educational Colonialism and Progress: An Enquiry into the Architectural Pedagogy of Bangladesh’, Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 28.1 (2019), 93–112.

9 Monika Grubbauer discusses the asymmetries of power intrinsic to studios abroad (and in particular how higher education institutions in richer countries offer students an ‘authentic’ experience in poorer ones); see Monika Grubbauer, ‘In Search of Authenticity: Architectures of Social Engagement, Modes of Public Recognition and the Fetish of the Vernacular’, City, 21.6 (2017), 789–99.

10 Bjørn Sletto, ‘Insurgent Planning and its Interlocutors: Studio Pedagogy as Unsanctioned Practice in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic’, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 33.2 (2013), 228–40. Reflecting on a studio that brought students from Texas to Santo Domingo, Sletto explains the challenges that emerged even in a course based on critical action research.

11 Ning Wang, ‘Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience’, Annals of Tourism Research, 26.2 (1999), 349–70. Wang offers a thorough review of scholarship on authenticity. While in the early twentieth century, ‘objectivists’ interpreted authenticity as a fixed quality (a material originality that things either have or not, and which cannot be copied), from the 1970s, ‘constructivists’ saw authenticity as a purely invented characteristic that people interpret depending on the context in which objects are presented. A third approach in the mid-1990s mediated through these views and accepted that, while authenticity rests in the eyes of the beholder, material originality plays an important role in forging our interpretation of it. Linking this epistemological evolution to the production of space, see Francesca Piazzoni, ‘Authenticity Makes the City: How ‘The Authentic’ Impacts the Production of Space’, in Planning for AuthentiCITY, ed. by Laura Tate and Brettany Shannon (London: Routledge, 2018), pp. 154–69. Here I explain how different approaches to authenticity have affected preservation and design practices.

12 Walter Benjiamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (London: Penguin, 2008), first publ. in 1936. Benjamin suggested that the aura of an original object could never be reproduced, and certainly not by then emerging tecnhologies such as photography and mechanical reproduction.

13 The Venice Charter of Restoration, which in 1964 formalised preservation guidelines across the global west, defined authenticity as an immanent, material property that determines the value of artefacts. Experts began to complicate this view in the 1990s, when the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) met in Nara, Japan, acknowledging how diverging approaches to authenticity informed preservation practices across the globe. For an overview of these debates, see Nara Conference on Authenticity: Proceedings, ed. by Knut Einar Larsen (Paris: UNESCO, 1995).

14 Foundational readings on the relativity of authenticity (its ‘invention’, so to speak) are Regina Bendix, In Search of Authenticity: The Formation of Folklore Studies (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997); and Umberto Eco, Travels in Hyper Reality: Essays (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986).

15 For an overview of authenticity and its relationship to consumerism, see Sara Banet-Weiser, AuthenticTM: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture (New York: NYU Press, 2012).

16 Sharon Zukin, ‘Consuming Authenticity: From Outposts of Difference to Means of Exclusion’, Cultural Studies, 22.5 (2008), 724–48.

17 Siobhan Gregory, ’Authenticity and Luxury Branding in a Renewing Detroit Landscape’, Journal of Cultural Geography, 36.2 (2019), 182–210. Gregory explains how marketeers use narratives of Detroit ‘coming back’ to its ‘authentic’ status (preceeding deindustrialisation) to sell luxury properties and goods.

18 The uses and users of public space, especially in historic towns, are expected to satisfy tourists’ expectations for ‘the authentic’. People whose appearance does not adhere to those expectations are banished. For an example on street vendors and performers, see Avi Astor, ‘Street Performance, Public Space, and the Boundaries of Urban Desirability: The Case of Living Statues in Barcellona’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43.6 (2019), 1064–84; and Miriam Stocka and Antonie Schmiz, ‘Catering Authenticities: Ethnic Food Entrepreneurs as Agents in Berlin's Gentrification’, City, Culture and Society, 18 (2019), 1–8. They explain how immigrant business owners simplify their own food-culture to market it as ‘authentic’ to white Germans.

19 For both types of exclusionary preservation, see, respectively, Xiaobo Su, ‘Heritage Production and Urban Locational Policy in Lijiang, China’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35.6 (2011), 1118–32; and Andrea Roberts, ‘When Does It Become Social Justice? Thoughts on Intersectional Preservation Practice’, 2017 <https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/bitstream/handle/1969.1/177539/When%20Does%20It%20Become%20Social%20Justice%20Thoughts%20on%20Intersectional%20Preservation%20Prac.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y> [accessed 30 January 2024].

20 The term ‘simulacrascapes’ is coined by Bosker in Bianca Bosker, Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2013). See also Michael Sorkin, Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 1992), who offers a foundational critique of the exlusionary implications of themed settings.

21 Francesca Piazzoni and Tridib Banerjee, ‘Mimicry in Design: The Urban Form of Development’, Journal of Urban Design, 23.4 (2018), 482–98. They explain the spread of themed residential environments in China through the lens of capital accumulation (operated by both private actors and the state). See also Annette Koh and Konia Freitas, ‘Is Honolulu a Hawaiian Place? Decolonizing Cities and the Redefinition of Spatial Legitimacy’, Planning Theory and Practice, 19.2 (2018), 27–30. They show how theming is used to suppress indigenous histories in the context of Hawaii's tourist attractions.

22 For each of these oppressive uses of authenticity, see, respectively, Lisa Berglund, ‘Excluded by Design: Informality versus Tactical Urbanism in the Redevelopment of Detroit Neighborhoods’, Journal of Cultural Geography, 36.2 (2019), 144–81; Julian Agyeman and Sydney Giacalone, The Immigrant-Food Nexus: Borders, Labor, and Identity in North America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020); and David Franco, ‘Tactical Urbanism as the Staging of Social Authenticity’, in Planning for AuthentiCITIES, ed. by Tate and Shannon, pp. 177–94.

23 Shu-Mei Huang and Jeffrey Hou, ‘Relocated Authenticity: Placemaking in Displacement in Southern Taiwan’, in Planning for AuthentiCITIES, ed. by Tate and Shannon, pp. 271–86.

24 Erica Lehrer, ‘Can There Be a Conciliatory Heritage?’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16.4/5 (2010), 269–88.

25 Leslie Shieh and Jessica Chen, ‘Chinatown, not Coffeetown: Authenticity and Placemaking in Vancouver's Chinatown’, in Planning for AuthentiCITIES, ed. by Tate and Shannon, pp. 36–56.

26 Lei Wei, Junxi Qian, and Jiuxia Sun, ‘Self-orientalism, Joke-work and Host-tourist Relation’, Annals of Tourism Research, 68 (2018), 89–99.

27 Maria Francesca Piazzoni, The Real Fake: Authenticty and the Production of Space (New York, NY: Fordham University Press, 2018).

28 Antonia Dawes, ‘The Struggle for Via Bologna Street Market: Crisis, Racial Denial and Speaking Back to Power in Naples Italy’, The British Journal of Sociology, 70.1 (2018), 377–94.

29 For an overview of over-tourism in Venice, see Seraphina Hugues, Paul Sheeranb, and Manuela Pilatoc, ‘Over-tourism and the Fall of Venice as a Destination’, Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9 (2018), 374–6; and Giacomo-Maria Salerno and Antonio Russo, ‘Venice as a Short-term City: Between Global Trends and Local Lock-ins’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30.5 (2022), 1040–59.

30 For the purpose of this article, students were asked to select the graphic materials that would best represent their own work. The figures that follow are the images selected by them.

31 Rapid ethnographic methods are explained in Sarah Pink and Jennie Morgan, ‘Short-Term Ethnography: Intense Routes to Knowing’, Symbolic Interaction, 36.3 (2013), 351–61. Galen Cranz introduced and systematised these methods in architectural education since the 1970; see Galen Cranz, Georgia Lindsay, Lusi Morhayim, and Hans Sagan ‘Teaching Semantic Ethnography to Architecture Students’, Archnet-IJAR, 8.3 (2017), 1–15. Annette Kim details the opportunities and challenges of using spatial ethnography for addressing spatial inequities in Anette Kim, Sidewalk City: Remapping Public Space in Ho Chi Minh City (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

32 These topics, as I explain later in the article, demonstrate the validity of authenticity in eliciting spatial inquiries well beyond the purview of studios abroad.

33 Ceridwen Owen, Kim Dovey, and Wiryono Raharjo, ‘Teaching Informal Urbanism: Simulating Informal Settlement Practices in the Design Studio’, Journal of Architectural Education, 67.2 (2013), 214–23. They explain the fashionable and problematic will of students based at schools in the global west to ‘save’ poor people without reflecting on deeper entanglement of design and power. Ulysses Segupta and Deljana Iossinova expose (and seek to reverse) the tendency to treat sustainability as another ‘must’ superficially addressed by students; see Ulysses Segupta and Deljana Iossinova, ‘Systemic Diagramming: An Approach to Decoding Urban Ecologies’, Architectural Design, 82.4 (2012), 44–51. With a particular focus on studios abroad, Grubbauer explains design tourism and its links to authenticity; see Grubbauer, ‘In Search for Authenticity’.

34 Engaging with Guatemalan immigrants living in Iowa, Gerardo Francisco Sandoval explains why minoritised people may wish to be or not to be visible in public space for different reasons; see Gerardo Francisco Sandoval, ‘Shadow Transnationalism: Cross-Border Networks and Planning Challenges of Transnational Unauthorized Immigrant Communities’, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 33.2 (2013), 176–93.

35 Focusing on the invisibility of Latinx skilled labourers who craft and maintain gardens across the US, Michelle Arevalos Franco explains the value of representation as a political device for emancipation; see Michelle Arevalos Franco, ‘Invisible Labor: Precarity, Ethnic Division, and Transformative Representation in Landscape Architecture Work’, Landscape Journal, 41.1 (2022), 95–111.

36 Karen Baptist and Nassin Hala, ‘Social Justice Agency in the Landscape Architecture Studio: An Action Research Approach’, Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 2.1 (2009), 91–103 (p. 92).

37 Nadia Anderson, ‘Public Interest Design as Praxis’, Journal of Architectural Education, 68.1 (2014), 16–27. Anderson uses these words to explain the change that public interest design provokes in the relationship between architecture and the public.

38 As discussed elsewhere, scholars of Design Justice have rejected traditional canons of expertise per which trained professionals have the right (or the ability) to design spaces that allegedly suit the needs of local groups. This rejection, however, can lead professionals to renounce proposing durable, large-scale transformations of space tout court, and instead solely support short-term projects (known as DYI, tactical urbanism, guerrilla urbanism, and the like). It has been suggested that, by continuing centring the needs of oppressed groups but at the same time moving beyond scattered interventions, trained professionals can recuperate architectural ambition and use their competence to elaborate more durable projects. In other words, practicing Design Justice is not about rejecting the idea that architects may have some technical knowledge that others may not have, but it is about detaching that knowledge from the interests of oppressive forces and use it to assist complex, truly emancipatory spatial interventions. See Piazzoni, Poe, and Santi, ‘What Design for Design Justice?’.

39 This affirmation reveals that some students still entertained the myth of architects as solitary geniuses, a myth perpetuated by magazines and blogs that glamourise buildings and their ‘author’ as if they operated in a void. While our department has tried to upend this misconception by requiring group collaborations and peer-to-peer reviews, these measures will likely remain inadequate until our studios (like those in most schools) will treat buildings, rather than process, as the primary focus of attention (and marking).

40 On architectural education that embraces dialogue as a mode of knowledge production, see Linda Groat and Sherry Ahrentzen, ‘Reconcptualizing Architectural Education for a More Diverse Future: Perceptions and Visions of Architectural Students’, Journal of Architectural Education, 49.3 (1996), 166–83.

41 Henry Giroux, Teachers as Intellectuals: Towards a Critical Pedagogy of Learning (Branby, MA: Bergin and Garvey Press, 1988).

42 Thomas Dutton, ‘Design and Studio Pedagogy’, Journal of Architectural Education, 41.1 (1987), 16–25.

43 The ways in which pursuing an urban justice agenda remains the domain of privileged architectural firms is explained in Aaron Cayer, Peggy Deamer, Shawhin Roudbari, and Manuel Schvartzberg, ‘Socializing Practice: From Small Firms to Cooperative Models of Organization’, in Spatial Practices: Modes of Action and Engagement with the City, ed. by Melanie Dodd (London: Routledge, 2020), pp. 245–55.