ABSTRACT

In this paper, we consider the impact of COVID-19 on Korean cosmetics firms. The research framework (i.e. OEM/ODM Business Model) shows sensing customer requirements, translating them through a fusion complex design lab, digital technologies (e.g. Big Data, AI, Supply Chain Technologies), and applying manufacturing capabilities for achieving sustainable competitive outcomes. It examines how digital technologies influence the ODM business model. The research methods include a literature review, an analysis of internal documents, and field interviews with top executives. It also focuses on the model’s response to the Fourth Industrial Revolution opportunities such as the IoT/AI. The case study covers both prior to the COVID-19 and post pandemic world contexts. We propose propositions based on our research model and discuss relevant lessons to other industries in terms of designing cross-functional creativities, implementing organizational flexibility, and achieving market expansion through operational speed and network partnerships.

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, growing business opportunities in East Asia are likely to continue with the expanding segments of the middle class. The post-pandemic world is characterized by an increasing emphasis on individualized self-care, green technology, the digital market, and an influx of venture firms. Accordingly, there might be a greater level of human innovation that meets the quality life aspiration of the growing middle class in the world (Alexandri and Janoschka Citation2020; Beane and Brynjolfsson Citation2020; Kochhar Citation2020). Emerging creative firms provide the reasons for optimism in the post-pandemic world (Dharmani, Das, and Prashar Citation2021; Goldberg and Reed Citation2020; Hong and Park Citation2020).

In the post-pandemic world, the growing middle class would choose their value priorities for beauty-cleanness goals, nutritional choices, and health care development needs (Byun and Shin Citation2017; Gardner Citation2021; Kaiser et al. Citation2021; Leach et al. Citation2021). The growth rates of Asian economies were slowed down during the COVID-19 pandemic and yet their growth opportunities would not be constrained (Dieppe Citation2021; Maliszewska, Mattoo, and Van Der Mensbrugghe Citation2020). Diverse industries – the cosmetic industry in particular – address the needs of these growing segments in Asia. In keeping up with the leading business trends, cosmetics firms also leverage big data and build their brand partnerships across industries and apply the Internet-of-Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) for their product and process development (Faria-Silva et al. Citation2020; Nguyen, Masub, and Jagdeo Citation2020; Čirjevskis Citation2020).

The vast amounts of big data gathered through IoT devices are now being used to improve entire value chain operations, creating a digital thread through the global value chain (GVC). Real world data are increasingly available to create new services and develop an innovative business model for global firms (Frederick, Bamber, and Cho Citation2018; Baines and Lightfoot Citation2013; Demil and Lecocq Citation2010). Kano, Tsang, and Yeung (Citation2020) suggest that research concerning GVCs and digitization is one of the essential subjects among several future research topics. Though previous extant studies have addressed the impact of new technologies on GVC configurations, future studies can answer the broader question of how digital technologies have transformed the basic governance structure of GVCs (Foster and Graham Citation2017; Foster et al. Citation2018).

In addition, fruitful research is noted in the areas of digital value chains, business model innovation, GVC governance, digital ecosystem development (Kano, Tsang, and Yeung Citation2020; Li, Frederick, and Gereffi Citation2019; Li et al. Citation2019; Kano Citation2018; Foster and Graham Citation2017; Foster et al. Citation2018; Jarvenpaa and Leidner Citation1999). Even so, much remains unknown in regard to Asian cosmetics firms that appeal to the growing Asian middle class.

As of 2021, according to Statista, the top ten global cosmetics manufacturers are: four from the U.S.A (Proctor and Gamble, Estée Lauder, Coty, and Johnson & Johnson), four from Europe (L’Oréal, Unilever, LVMH, and Beiersdorf-two from France and the UK and Germany one each) and two from Japan (Shiseido and Kao). Global cosmetics market share by region suggests that the Asia region is the largest (39.28%), followed by Western Europe (25.96%), North America (22.1%), Eastern Europe (5.47%), Latin America (5.1%), and Africa/Middle East (2.09%). A real challenge for the cosmetic industry is about how to develop and implement its own unique business model in rapidly changing market environments (Morea, Fortunati, and Martiniello Citation2021; Spieth et al. Citation2019).

In this context, this study aims to explore how cosmetics firms meet the changing customer demands and become technology-enabled beauty companies. For this purpose, it presents a research framework of the Original Design Manufacturer (ODM) business model. The case study of COSMAX identifies key success factors of this hidden champion. For future research, lessons are summarized, and the theoretical and managerial implications are discussed.

Evolving business model of cosmetic industry

Business model evolution reflects the new strategic emphasis of firms and industries in dynamic market contexts (Demil and Lecocq Citation2010; Jacobides and Reeves Citation2020; Chang et al. Citation2021). Recently, digital technologies have had a tremendous impact on the evolution of business models and ecosystems (Park Citation2017; Foster et al. Citation2018). Broadly speaking, the IoT is a system consisting of networks of sensors, actuators, and smart objects whose purpose is to interconnect all things, including every day and industrial objects, in such a way as to make them intelligent, programmable, and more capable of interacting with humans and each other. Recently, the rise of big data gathered through IoT devices makes it possible for after-sales data-driven knowledge services in GVC to be the most valued segment in the near future.

In addition to these specific value chain segments, throughout global value chains, there are a variety of services undertaken at each stage, including R&D, product design, procurement, production, and marketing activities (Frederick et al. Citation2017; Low and Pasadilla Citation2016). While these activities can be contained within a single firm or divided among different firms, these have generally been carried out by inter-firm networks on a global scale in the context of globalization (Gereffi and Fernandez-Stark Citation2016). Thus, the IoT is creating numerous challenges and opportunities for a new business model. The success of the IoT depends strongly on standardization, which provides interoperability, compatibility, reliability, and effective operations on a global scale.

Contemporary products tend to add complexity to the system, while consumers’ demands increase uncertainty, diversity, and sophistication in the business processes (Park and Hong Citation2012; Park Citation2017). Increasingly, managing complexity is becoming a huge challenge for the manufacturers of mechanical products such as automobiles, digital devices, and precision machines (Fujimoto and Park Citation2012; Reeves et al. Citation2020). The process industry, such as cosmetics, is no exception because realistic customer experiences require additional IoT and AI applications to the existing complex design and manufacturing processes. The closed system business model is not appropriate to deal with such complex requirements. Instead, the digital ecosystem environment necessitates more open, holistic, and adaptive business models (Liu, Tong, and Sinfield Citation2021; Park Citation2017).

In the cosmetic industry, it is common for a single company to manage all value creation processes through vertical integration which is to process and deliver products from development to logistics. Such has been the case of supply chain management practices of the cosmetic industry. A typical business model of Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) and ODM in the 1990s was similar to what Apple applied to Taiwan’s Foxconn (Hong and Park Citation2014). As shown in the relation between Apple and Foxconn, manufacturers in a wide range of industries are turning to specialized service providers to complete different functions in their chains. While electronic manufacturing service (EMS) firms in the OEM business model are some of the most prominent examples, this externalization extends to a host of other activities including raw materials procurement, production planning, marketing, logistics, and inventory maintenance (Frederick et al. Citation2017; Low and Pasadilla Citation2016). It is to use modularity of product architecture to promote the collaborative relationship of global value and supply chains in these products (Park and Hong Citation2012; Hong and Park Citation2014; Park Citation2017; Seyoum Citation2021).

Different from assembled manufacturing products, cosmetics products use highly integrated processes. Their integral product architecture makes it challenging to delegate cosmetics product design know-how and manufacturing processes (Park Citation2017; Lim and Fujimoto Citation2019; Park, Hong, and Shin Citation2019). During the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been increasing online sales in the cosmetic industry as customers stop visiting cosmetics stores in the offline market (Kwon Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has also accelerated wellness-related micro-trends, with the societal emphasis on health and safety as a top priority (Gardner Citation2021; Kwon Citation2020; Nordin et al. Citation2021).

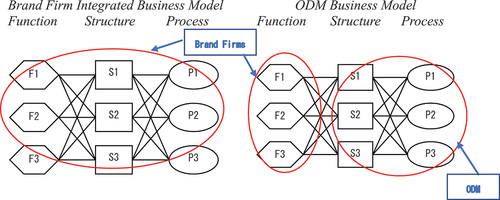

shows the evolution of the process architecture of the cosmetic industry. The processes are denoted as Fn (1,2,3) (front-end R&D-marketing-design function), Sn (1,2,3) (mid-end product structure) and Pn (1,2,3) (back-end processes) of product lines (n). Brand firms (e.g. L’Oréal, Johnson & Johnson, Shiseido) have maintained their overall control through vertical integration through their supply chains. This is what is called the brand firm integrated business model function structure process. In contrast, the ODM business model is noted for concentration of Fn (1,2,3) (R&D-marketing-design) by brand firm and Sn (1,2,3) (mid-end product structure) and Pn (1,2,3) (back-end processes) of product lines (n) by the ODM firm (e.g. COSMAX in 1992). Such separation and delegation of work are to better facilitate the increasing customer complexity expectations and scaling requirements.

Figure 1. Evolution of process architecture of cosmetic industry.

The complexity of product architecture under increasing customer needs, evolving GVC in the Industry 4.0, and technological advances such as digital platforms, affect business model change of the cosmetic industry as well as other industries. For example, with the growth of online platforms, global cosmetics sales are likely to grow from $420 billion (2018) to $716.3 billion (2025) (Global Cosmetic Market Research Report 2021). With such an extraordinary level of offline and online market growth prospects, the industry invests more in comprehensive digital channel development by strengthening new platform entry strategies and offering purchasing options through smartphone apps. In Korea, rapid delivery services, online orders fulfilled within 3 hours, are tested and implemented on a large scale (Kwon Citation2020).

Korean cosmetic industry: a historical overview

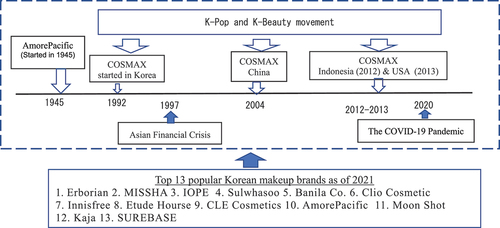

Recently, there has been the growing popularity of K-pop and K-beauty in global markets (Wang and Lee Citation2019; Seo, Cruz, and Fifita Citation2020). An overview of the history of Korea’s cosmetic industry suggests that it achieved rapid growth in the 1990s. In between 2000–2020, there was an average annual growth rate of 13.4% (Kim and Ryou Citation2016; Park and Yoo Citation2016; Lim et al. Citation2020). By 2018, Korea’s cosmetics exports reached about $6.3 billion, rising to fourth place in the world, and then reaching $6.5 billion in 2019 and $7.2 billion in 2020, an average annual growth rate of 4%. As a result, the cosmetic industry is regarded as one of the new growth industries for Korean exports along with bio-health, rechargeable batteries, and agricultural and fishery products (Kwon Citation2020). It increased from .54% to 1.04% in 2018 and is becoming a new growth engine and export industry (Lim et al. Citation2020).

The introduction of OEM and ODM into the Korean cosmetic industry began in 1990 when Kolmar Japan launched a joint venture in Korea. At first, Kolmar Korea only did the OEM business, but two years later, COSMAX also started a joint venture with a Japanese firm. From 2004, COSMAX invested about 5% of its sales in R&D to develop its expertise as an ODM company. In 2015, it became the largest ODM company in the world surpassing the sales of Intercos (Song Citation2016). As of 2021, it still maintains the top competitive position. After the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, there was a rapid turning point in the Korean cosmetics OEM and ODM industry. As value-conscious consumers flocked to mid- to low-priced cosmetics brands, OEM and ODM companies showed enormous growth with the increasing large scale of outsourcing work orders. Numerous start-up cosmetics firms with limited capital and distribution networks outsourced their manufacturing functions to ODM firms like COSMAX and Kolmar Korea (Byun and Shin Citation2017; Lim et al. Citation2020). However, brand cosmetic firms such as AmorePacific and LG Household & Healthcare in Korea maintained their own speciality stores (Lim et al. Citation2020).

First, the growth of OEM and ODM resulted in structural changes in the cosmetics value chain (Park and Yoo Citation2016; Lim et al. Citation2020). Before 2003 there was the separation between brand firms and their distribution channels. After 2004, brand firms developed and integrated their distribution channels. This deepened the differentiation battles between rival companies. Until 2002, large and mid-sized companies experienced similar patterns of growth. However, the growing popularity of the speciality stores and brand shops (e.g. Missha and Face Shop) of large companies almost wiped out the sales opportunities of mid-sized companies. In response, mid-sized companies seeking a new sales breakthrough switched to the OEM and ODM businesses to take advantage of their accumulated technology capabilities and production facilities.

Second, COSMAX provided Face Shop, one of the major brand shops, with more than 300 cosmetics items in the fourth quarter of 2004. Key characteristics of such a brand shop are: ① very trendy and fast product replacement cycle, ② outsourcing all its products, and ③ low entry barriers for competitors who have capital and network relationships. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the growth of these brand shops in Korea.

Third is the growth of the Korean cosmetic industry. shows that the history of the Korean Cosmetic industry is relatively short. AmorePacific, the first modern Korean cosmetics firm, started its operations in 1945, the same year when Korea became independent from Japan. COSMAX was founded in 1992. During the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, many Korean firms filed for bankruptcy. COSMAX was no exception with serious financial hardships. However, after putting its domestic operations in order, COSMAX expanded its operations to China (2004) and the U.S.A (2013). With the growing popularity of K-pop, the K-beauty movement also facilitated the growth of Korean cosmetics firms. As of 2021, there are 13 cosmetics brands that are associated with Korean K-beauty. COSMAX is partnering with many of these firms in promoting their brands in global markets beyond Korea.

The next section presents a case study of COSMAX. It examines the evolution of business models. We discuss how COSMAX utilizes digital technology in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. We further consider how it overcomes and thrives in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Case study

Selection criteria

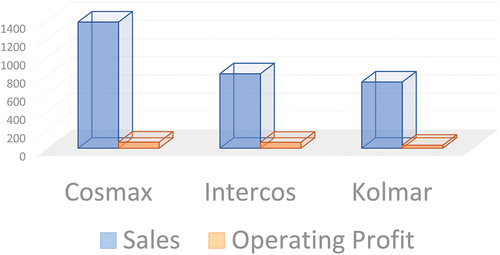

We selected COSMAX as our case firm, which is a rapidly growing hidden champion in the industry of Korea and a leading ODM cosmetics firm. The reason why we selected COSMAX is that it is a Korean ‘hidden champion’ company. Established in 1992 with four employees, it has made a breakthrough, employing 6,556 people in 2020 and boasted $2.173 billion in group sales ($1.383 billion in cosmetics sales) in 2020 (Note: 1$ USD = 1,000 Korean Won), making it the No. 1 ODM firm globally (). By 2020, the average annual growth rate in the last 17 years has been 35%. In 2021, the annual production capacity is 1.85 billion units. In 2021, it drives its strategic direction into differentiated development, customization and personalization of product through digital technologies.

Case study methods

For our research design, we followed the methodology of the intensive case study (Mees-Buss, Welch, and Westney Citation2019; Sayer Citation1992, Citation2000). Sayer (Citation2000) describes an intensive case study as a process of discovery to uncover the patterns and drivers of change in a single case to build a theoretical explanation. Our use of a single case is also consistent with others who have studied global value chains and business model processes in global firms (Mees-Buss, Welch, and Westney Citation2019; Jonsson and Foss Citation2011; Burgelman Citation2011). Through a single case study of Unilever, Mees-Buss, Welch, and Westney (Citation2019) assert that the quality of the contribution of an intensive case study does not depend on the number of cases studied, but on the insights that the single case studied in depth can reveal about the phenomena under study.

For the rigorous case study, we consider internal and external validity, and reliability requirements (Eisenhardt Citation1989; Gibbert, Ruigrok, and Wicki Citation2008; Easton Citation2010). First, for external validity, we use the theory of product architecture as an overarching theory base (Fujimoto and Park Citation2012; Park Citation2017; Reeves et al. Citation2020) and present original brand manufacturer (OBM) and ODM business models. For reliability, we adopt case study processes that support external and internal process integrity through recording and careful documentation for all interviews. For the internal validity, we conducted multiple executive interviews with founders and senior executives of COSMAX. In addition to internal firm documents, we conducted multiple field visits (e.g. R&D centre and factories). We reviewed internal documents (e.g. Annual Reports) and industry reports for cross-validation. Finally, we examined the strategic and operational practices and compared them with their performance outcomes (e.g. financial reports).

Case analysis

COSMAX is a Korean ‘hidden champion’ company. It was established in 1992 with four employees. In 2004, it became the first Korean ODM company in China. Since then, it has achieved an average annual growth rate of 35%. It is positioned as the indisputable leader of ODM companies in China. It became the global No. 1 ODM firm from 2015. COSMAX’s subsidiaries and factories are located in six cities in five countries (Korea, China, the United States, Indonesia, and Thailand). Based on the annual production capacity, the total annual capacity is 1.85 billion units, including 410 million units in Korea, 210 million units in the United States, 990 million units in China, 140 million units in Indonesia, and 90 million units in Thailand as of 2021. It achieved $2,173 million in group sales ($1,383 million in cosmetics sales) in 2020.

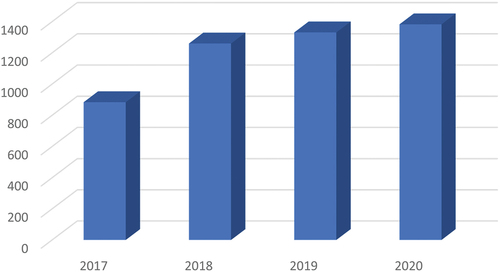

After successfully making inroads into China, it opened COSMAX U.S.A in 2013. The US plant acquired facilities from L’Oréal, the largest cosmetics company in the world, after acquiring the Ohio Solon plant, and transformed it to produce diverse product lines that satisfy US customers. With the establishment of a local Research and Innovation (R&I) Centre in New Jersey, it focused on meeting the changing requirements of American consumers with Korean innovativeness through collaboration with the R&I Centre in Korea. It is currently developing or producing about 50 brands of products, including Estee Lauder and Stila. As shown in , its cosmetics sales achieved $884 million in 2017 and $1,383 million in 2020.

Figure 4. 2017–2020 cosmetics sales of COSMAX (million USD) (Source: COSMAX).

COSMAX is making efforts to strengthen its customer focus to become the best ODM company in the United States. As part of that, it acquired NuWorld in November 2017, the third largest colour cosmetics ODM company in the United States. Through the acquisition of NuWorld, COSMAX is operating its existing Ohio factory as a skin care factory and enhancing efficiency by utilizing the Nuworld factory as a colour factory. In addition, it has secured a new customer base so that it can continue to grow in the US market.

In addition to China and the US, it also expanded into Southeast Asian markets. COSMAX Indonesia, which was established in Jakarta in 2012, started its operations in 2014, while the Jakarta plant is pioneering Southeast Asian markets such as Indonesia and Malaysia. Furthermore, COSMAX Thailand has been established and is in operation to open up markets such as Thailand, Myanmar, and Vietnam. COSMAX’s production capacity has been greatly increased to 1,150 million at the end of 2016 from 750 million at the end of 2015. Furthermore, in 2021, it reports more than 1,850 million production volumes.

Beauty scientists for innovative ODM business model

What has led COSMAX to the top of the global beauty industry is its unparalleled focus on research and innovation. In 2021, there are over 720 researchers at COSMAX R&I centres in five countries – Korea, China, the USA, Indonesia, and Thailand, accounting for over 25% of total manpower. In pursuit to be the best in the world, its researchers are relentless in exploring, experimenting, and developing new products and formulas harnessing patented novel materials and technologies exclusive to COSMAX. Thinking outside the box is the term that best describes COSMAX R&I centres. Breaking from convention, the R&I centre in Pangyo in Korea restructured the entire organization in 2015. Its goal was to break the walls between skincare and makeup. It now has 3 R&I centres and 9 labs that join together skincare and makeup categories that share similar and complementary fundamental technologies.

Industry 4.0 and ODM business model

As a leading global cosmetics firm, COSMAX pays attention to the innovative opportunities associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution using the IoT and AI. COSMAX has three keywords: pre-emption, connection, and concentration. COSMAX aims to accelerate its speed and flexibility to stay ahead of its rivals (Kim and Lee Citation2018). It creates innovation through forwarding linkage with affiliated companies, partners, and academia. It implements organizational innovation for selection and concentration and building a system that can deliver value to customers. In view of the Fourth Industrial Revolution opportunities, in 2014 COSMAX initiated the culture of ‘Be innovative’, ‘Stay simple’, and ‘Aspire to be Industry No.1’ through various pilot projects (Kim and Lee Citation2018). Chairman Kyung-soo Lee thought that new technologies were necessary for consumers to recognize the innovation of COSMAX. A new technology also offers new experiences. Thus, he says enthusiasm and creativity are important to COSMAX. In order to be creative, it has made efforts to remove communication barriers. For example, project participants are encouraged to share their opinions when they are in meetings.

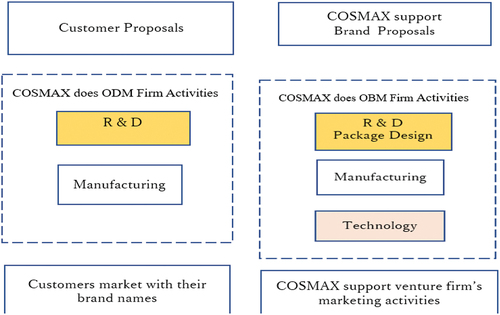

shows two different business models of COSMAX. For the first one, COSMAX works with as an ODM with traditional cosmetics brand OEM firms with existing brand names. COSMAX supports global brand firms to overcome their vertical integration bottleneck by providing whatever specific functional services they need. COSMAX helps develop new products based on brand firm customer proposals and delivers the products as OEM’s brand products. In the second one, COSMAX positions as the OBM with venture firms without established brand names. This is a customized service for venture firms that have the innovative concept and business ideas but lack value proposal experiences and marketing activities. For both models, COSMAX does R&D, manufacturing, and technology functions. For the OBM model, COSMAX also helps package design because their venture firms have no established brand names. COSMAX as an OBM offers multiple levels of functional support to customers that need to create and market their own new brand value. It supports small and medium-sized firms from emerging economies without established brands. COSMAX works with venture firms with innovative ideas but no manufacturing and marketing capabilities.

Second, speed is essential in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Chairman Kyung Soo Lee uses the catchphrase to ‘Be the First Mover’. The current competitive market environment is characterized by high volatility and great uncertainty (Kim and Lee Citation2018). COSMAX’s reputation among global brand firms (e.g. L’Oréal) is in its quality control capability and successful fast-cycle product delivery. COSMAX also conducts quality inspections (through an open network development system) to ensure product stability, brand compatibility, and micro-organism innovativeness that meet or exceed the standards of the L’Oréal Institute. Considering the high customer-sensitive characteristics and competitive market requirements of the cosmetic industry, COSMAX aims to excel in quality, flexibility, and fashionability. COSMAX utilizes IoT technology to shorten the product development cycle from 18–24 months to 6–9 months.

COSMAX also implements the SAP as an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system to fulfil the speed requirements. The SAP standardizes the business processes among subsidiaries in Korea, China, and the United States. Furthermore, it builds IT infrastructure to support reliable information flows for real-time business development among each business unit. Once the SAP system is adopted, it provides profit and loss information for each product, since the total profit and loss statement can be aggregated every five days on a monthly basis. Multi-dimensional sales, cost, and profit analysis become possible, and online based business will enable various management information to be shared, allowing for a pre-emptive response to future environmental changes.

Third, flexibility is crucial in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. COSMAX is responding flexibly from the perspective of brand companies, not to that of producers (Kim and Lee Citation2018). COSMAX cooperates with customers for this goal. Customers from emerging economies like China appreciate the speed and flexibility performance of COSMAX. Since COSMAX entered China in 2004, it operated as a customized ODM, not an OEM. It was fundamentally different from the way Japanese companies and Italian companies operated in China. These firms made product offerings in China in the minimum delivery period of three months. In contrast, COSMAX supplied its products in 1.5 to 2 months while satisfying the quality requirements of customers. This has become a big success factor in the Chinese market. The Chinese local cosmetics brand firms were very impressed with COSMAX’s performance and there was a huge increase in their order volumes. Soon COSMAX China became the No. 1 ODM company in China.

COSMAX also used the concept of functional headquarters (FHs) for product production, quality control, logistics, and purchasing. By integrating these FHs into ERP, they actively respond to real-time requests with their client firms on various fronts. Naturally, process productivity and functional efficiency showed drastic improvement.

Fourth, another key initiative is to enhance linkage competence (network capability) (Park and Hong Citation2012; Hong and Park Citation2014; Park Citation2017). COSMAX has cooperative partnerships with more than 600 strategic customers in Korea and overseas with whom it pursues open innovation network practices. It also develops proprietary raw materials and new products through collaboration with more than 200 raw material component providers and carries out joint development projects with prominent global cosmetics companies. It shares customer progress with orders, enhancement status, and production schedule with customers, and holds meetings to share the vision with partner companies and build a mutual growth base to strengthen cooperation management.

The COSMAX R&I Centre operates a variety of industry-university cooperation programs for its competitiveness as a research-oriented company where speed and flexibility are important. It is responsible for the future technology strategy of COSMAX.

COVID-19 impact and response

The COVID-19 pandemic dictates the global cosmetics firms to change their business practices. Globally, demand for cosmetics declined due to overall consumption contraction and mask-wearing shortly after COVID-19. However, because of skin problems caused by wearing a mask, demand for skin care products has started to recover, and demand for colour products is rapidly recovering along with the expansion of vaccination. With the prolonged constraints of outside activities and a decrease in travel demand, large offline brand companies have been severely hit, and online channels have been rapidly expanded instead. As such, COVID-19 has had a great impact on the Korean and Chinese cosmetics markets through 2020–2021 and has brought about many changes in the industry.

Cosmetics firms diversify their distribution channels from offline to online. COSMAX is concentrating its efforts on OBM services to provide customer service to meet these changes in the distribution market. In the future cosmetics market, where the market becomes diverse, it is inevitable to expand the service from the ODM business model to the OBM business. COSMAX is making more efforts to respond to market changes faster than online channel specialists such as Amazon and Alibaba.

With the COVID-19 challenges, cosmetics demand temporarily decreased but is recovering from the latter part of 2021. COSMAX, despite its rapid growth as an ODM/OBM business model, was no exception. There was an obvious sales slowdown from the beginning of 2020 to the beginning of 2021.

Here, we summarize the specific COSMAX response strategies. It identified the needs of small and medium-sized online brand customers entering the market in line with the expansion of online channels. Recognizing that the core needs of these small and medium-sized online brand customers are Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ) and short lead time-sensitive to trends, COSMAX utilized digital strategies to lower the market entry barriers of these customers. In other words, online data was used to help small and medium-sized online brand companies enter online channels. Specifically, by providing various contents to customers using live commerce and real-time communication information between sellers and buyers, it acquired valuable big data of customers.

Based on relevant data analysis, there were appropriate and timely product proposals. To shorten the product development cycle time, it conducted consumer trend analysis, customized online channel proposals, and preliminary review of raw material stability. It reduced the supply and demand requirements of raw and subsidiary materials (management of raw material delivery time, fostering strategic partners, etc.), and developed a predicting system for content-packaging material compatibility. In addition, by introducing OCR (Optical Character Reader), they reviewed regulations and advertising texts in advance to help online brand companies. Small and medium-sized brands also shared the lessons from their customer claims with the R&I centre of COSMAX. This further helped to design the risk management rules to mitigate risks associated with consumer claims after-sales.

COSMAX adopted several new strategic practices to shorten the supply and demand cycle of raw materials and improve the supply chain disruptions. First, COSMAX shortened the delivery period through pre-emptive management of raw materials with a long delivery period. It extended the operation cycle of the development stage of purchasing business and fostered close communication and collaboration between the management of strategic partners.

Second, it introduced pre-order manufacturing, established a production plan based on the expected delivery date of subsidiary materials, and conducted out-going inspections of partners. As a result, the existing lead time was reduced from 9 weeks ((1) laboratory & design process (base confirmation/subsidiary material confirmation/advertising text writing) (3 weeks) + (2) subsidiary material supply (4.5 weeks) + (3) production (1.5 weeks)) to 7 weeks ((1) laboratory & design process (3 weeks) + (2) subsidiary material supply and production (4 weeks)). It also helped small and medium-sized brands enter the market more easily by lowering the MOQ to 1/10 (from 10,000 to 1000). As a result of this agile response to COVID-19, COSMAX expects the proportion of Chinese online channel customers to rise from 38% in 2019 to 59% in 2020 and 74% in 2021.

Third, COSMAX focused on research and development by selecting major strategic products by category/region of customers and conducting collaborative projects with MZ generation beauty creators through direct communication with end-users. Product development was carried out in response to these new needs. Reflecting these consumer needs, in the first half of 2021, 50 vegan products were launched, and more than 30 promotions were conducted. An eco-friendly package roadmap was established and led the packaging trend. The development of the multi-innovative formulation suggested an alternative for colour cosmetics-oriented customers. The results of implementing these innovative practices resulted in the huge success of Chinese lip tint and Korean multi-balm, and COSMAX and small- and medium-sized online brands have achieved growth together.

Discussion

This case study suggests the role of leadership to facilitate a successful business model strategy utilizing digital technology. In view of the growing business opportunities, COSMAX revised its mission in 2014. The following goals to reform its organizational culture are ‘Be innovative’, ‘Stay simple’, ‘Aspire to be Industry No.1’ in the era of Industry 4.0. It has also applied these clear goals through various pilot projects to build its ODM/OBM business model. It also utilizes technologies (e.g. IoT, AI, SAP) as a key differentiator for cosmetics brand firms (e.g. L’Oréal).

Theoretical implications

First, this study shows how the ODM/OBM business model is being implemented in the cosmetic industry to manage the rapid growth requirements in the global cosmetic industry. ODM can be defined as front-end design-based and functional-specific work to support major global OEMs (brand firms) in the cosmetic industry. However, OBM can be defined as an Original Brand Manufacturer and cross-functional diverse work to provide integrated business process services for top brand firms and new venture firms. For both models, COSMAX demonstrates how it applies market research-intensive product concepts plus its design/manufacturing capabilities.

Second, this study extends GVC research in the digital contexts. The GVC study is one of the crucial topics in international business study. Laplume, Petersen, and Pearce (Citation2016) suggest that the diffusion of 3D printing technology in an industry is associated with development towards shorter and more dispersed global value chains. Kano, Tsang, and Yeung (Citation2020) reviewed the rapidly growing domain of GVC research by analysing several highly cited conceptual frameworks. Relating to digitalization, future studies could answer the broader question of how digital technologies have transformed the basic governance structure of GVCs (Foster and Graham Citation2017; Foster et al. Citation2018; Hanelt et al. Citation2021; Vial Citation2019).

In some industries, the new manufacturing technology is likely to pull manufacturing value chains in the direction of becoming more local, and closer to the end-users and the digital technology induces the engagement of a wider variety of firms (local and online print shops), as well as households, in manufacturing. The rise of big data gathered through IoT devices causes after-sales services as well as production in GVC to be the most valued segments. There are a variety of services undertaken at each stage, including R&D, product design, procurement, production, and marketing activities (Frederick et al. Citation2017; Low and Pasadilla Citation2016). While these activities can be contained within a single firm or divided among different firms, these have generally been carried out by inter-firm networks on a global scale in the context of globalization (Gereffi and Fernandez-Stark Citation2016).

Digital platforms and associated ecosystems in GVCs offer new values for multifaceted innovation and value creation, and for transferring value across borders with added efficiency and flexibility. Thus, digital technology-enabled platformization or the shift from individual products or services to platforms as the basis for offering value has considerable implications for GVCs such as connectedness among different groups of actors around the world in fundamentally new ways (Nambisan, Zahra, and Luo Citation2019; Stallkamp and Schotter Citation2019; Coviello, Kano, and Liesch Citation2017). Furthermore, digitization also allows MNEs to quickly change their business models by adding or subtracting network units, adjusting multi-sided platforms, or modifying existing links and interactions (Kano, Tsang, and Yeung Citation2020). COSMAX is a successful model in terms of business model change from OEM to ODM and OBM utilizing digital technology.

Third, this study illustrates the enabling roles of the IoT and supply chain technology in the post-pandemic context. It is to integrate front-end business processes (e.g. sensing market trends by using Big Data technology/AI/IoT/CRM), mid-end operational processes through global supply chain technologies (e.g. SAP, SCM and Blockchain) for global information, integration, and logistical support, back-end manufacturing and distribution processes by building online platform (e.g. SCM, Supplier Relationship Management and online platform) and integrated package design/manufacturing service by simulation and development of prototype (e.g. computer simulation and CAD design).

COSMAX has achieved time reduction in new product development. In partnership with L’Oréal, COSMAX utilized its IoT technology to shorten the period of new product development, from 18–24 months to 6–9 months. It has also introduced the SAP system to make decisions that respond to the speed of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. It has achieved productivity through standardization. The SAP system standardizes the business processes among subsidiaries in Korea, China, and the United States. It also builds IT infrastructure to support information standardization for real-time business development among each corporation. It also accelerates E-business through business analytics utilizing AI in COVID-19. Multi-dimensional sales, cost, and profit analysis become possible, and e-Biz will enable various management information to be shared, allowing for pre-emptive response to future environmental changes.

Furthermore, in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, COSMAX adopted a new business model, breaking away from the traditional distribution structure. For example, by using the COSMAX online platform, it expanded the online marketplace and accelerated the information exchanges between the company and customers around the world. By utilizing such an extended global online platform, it provided customers with optimal brand experiences and customized products that reflect changing consumer needs in the COVID-19 pandemic era.

In 2021, COSMAX established a digital business headquarters. It also recruited AI experts. Senior managers from COSMAX and its strategic suppliers participated in Google’s machine learning boot camp to train AI experts for the first time in the cosmetic industry. In the future, in order to respond to the trend of the cosmetics market, which is rapidly changing with the focus on consumer experience, the cosmetic development process will be digitally connected, so that not only global customer companies but also single influencers who are interested in cosmetic development will be customized end-to-end. The strategy is to further expand the market by building an end platform.

presents the different types in response to Added Economic Value (AEV) of Global Value Chain (GVC) and degree of Digital Technology Utilization (DTU) as the two axes. Based on our findings, we suggest propositions with two axes.

The first and second patterns are Analogue OEM Model (P1A) and Analogue ODM/OBM Model (P1B), which represent OEM and ODM/OBM business model patterns in the era of analogue. Shih (Citation1996) observed that in the personal computer industry, both ends of the value chain command higher values added to the product than the middle part of the value chain. In many manufacturing industries, the two ends of the value chain such as conception, research, and development at the starting end, and branding and marketing at the finishing end command higher value per worker when added to the product than does the middle part of the value chain such as manufacturing (Shih Citation1996; Mudambi Citation2007, Citation2008). In other words, the value-added per head of the activities at the two ends of a GVC is higher than that in the middle, which can be depicted using a smile curve. In the same analogue business model, according to Shih (Citation1996), the ODM/OBM model seems to be higher value-added than the OEM model. As shown in the case study of COSMAX, it started the OEM business model in 1992 and evolved its business model into an ODM business model strengthening R&D investment. Hence it is able to have captured high value-added in the era of analogue.

In sum, we anticipate the degree of value-added differently from the way set forth by the traditional smile curve approach. It can be applicable to business model evolution in the era of digital transformation. Therefore, we posit:

Proposition 1A and 1B:

Analogue ODM/OBM Model seems to be higher value-added than Analogue OEM Model in analogue technology.

The third and fourth patterns are the Digital OEM Model (P2A) and Digital ODM/OBM Model (P2B), which show types of Added Economic Value of Global Value Chain utilizing digital technologies. As shown in the case study of COSMAX, from 2014 it adopted a new business model, breaking away from the traditional distribution structure responding to the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Recently, by using the COSMAX online platform, it expanded the online marketplace and accelerated the information exchanges between the company and customers around the world. By utilizing such an extended global online platform, it provided customers with optimal brand experiences and customized products that reflect changing consumer needs in the COVID-19 pandemic era.

Thus, as proposed above, we posit:

Proposition 2A and 2B:

The Digital ODM/OBM Model seems to be higher value-added than the OEM model.

Managerial implications

This case study suggests an example of best practices of digital transformation of cosmetics firms in the post COVID-19 world (e.g. hybrid – on/offline global market – advanced and emerging markets).

First, COSMAX has provided new customer experiences through innovative product development and, as a result, has become a differentiator (e.g. speed, cost competitiveness, flexibility). This case shows how firms from Asia may rise and thrive even in the post COVID-19 era. The crucial element is to expand their dynamic capabilities by assuming hybrid roles as an R&D-marketing-manufacturing integrator and design-manufacturing coordinator (Lim and Fujimoto Citation2019; Teece Citation2018).

Second, COSMAX has built a global supply chain collaboration network with a cooperative partnership for open innovation (e.g. 600 strategic customers in Korea and overseas), developed proprietary raw materials and new products (e.g. 200 raw material component providers), carried out joint product development with most of the major global brand firms and provided package design support (e.g. global logistics). In the post-pandemic world, the roles of the global supply chain network are re-examined and yet, they are not going to diminish. Instead, firms require a great deal of agility in organizing their regional market basis (e.g. Northeast Asia, North America, Europe, and Southeast Asia) with greater autonomy and at the same time flexible connectivity (Shih Citation2020).

Conclusion

This study suggests how to pursue post-pandemic business opportunities through the case study of COSMAX. We examined how IoT technologies influence the ODM business model. Through field interviews with top executives, we examine its response to the Fourth Industrial Revolution opportunities such as the IoT/AI. Since 2014, COSMAX is noted for implementing strategic initiatives for innovativeness, simplicity, and industry competitive leadership throughout its business units. We report how it achieves the outcomes of cross-functional creativity, operational speed, organizational flexibility, and utilizing a fusion complex lab to realize the growing global market potentials.

The research framework (i.e., OEM/ODM Business Model) starts with sensing customer requirements and translating them through a fusion complex design lab, IoT Technologies (e.g. Big Data, AI, Supply Chain Technologies), and manufacturing capabilities. Through the case study of COSMAX, we defined, tested, and validated the ODM/OBM business model company. Lessons and implications of this case study are relevant in the post-pandemic world beyond the cosmetic industry in that it shows how to achieve cross-functional creativity, operational speed, and organizational flexibility in a growing global market expansion through network partnerships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Young Won Park

Young Won Park is a Professor at the Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Saitama University and an Associate Professor of Project of Manufacturing Management Research Centre, Faculty of Economics at The University of Tokyo, Japan. His articles have been published extensively in journals including International Journal of Production Economics, International Journal of Information Management, Management Decision, International Journal of Technology Management, and Business Horizons. His research interests are in technology management and Japanese manufacturing systems and information system strategy.

Paul Hong

Paul Hong is a Distinguished University Professor of Global Supply Chain Management and Asian Studies at the University of Toledo, USA. His articles have been published extensively in journals, including Journal of Operations Management, Journal of Supply Chain Management, International Journal of Production Economics, Journal of Business Logistics, Corporate Governance: An International Review, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Service Management, and European Journal of Management. Several books with Dr. Young Won Park include Rising Asia and American Hegemony (2020, Springer), Creative Innovative Firms (Citation2019, Springer), Building Network Capabilities in Turbulent Competitive Environments (2012 and 2014, CRC-Taylor Francis). His research interests are in global supply chain management, entrepreneurial innovation, and interfaces of ToP and BoP.

Geon-Cheol Shin

Geon-Cheol Shin is a Professor of the School of Management at Kyung Hee University in Seoul, Korea. He currently serves as country director of Korea for the Academy of International Business. His articles have been published in journals including Korean Management Review, Korean Journal of International Business, Industrial Marketing Management, International Marketing Review, Journal of Product Innovation Management, International Business Review, Journal of Brand Management, Journal of Global Marketing, Journal of Global Academy of Marketing Science, International Journal of Technology Management, Global Economic Review, and the European Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management. His research interests are in the areas of marketing strategy and global business strategy.

References

- Alexandri, G., and M. Janoschka. 2020. “Post-Pandemic Transnational Gentrifications: A Critical Outlook.” Urban Studies 57 (15): 3202–3214. doi:10.1177/0042098020946453.

- Baines, T., and H. Lightfoot. 2013. “Servitization of the Manufacturing Firm: Exploring the Operations Practices and Technologies That Deliver Advanced Services.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 34 (1): 2–35. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-02-2012-0086.

- Beane, M., and E. Brynjolfsson. 2020. “Working with Robots in a Post-Pandemic World.” MIT Sloan Management Review 62 (1): 1–5.

- Burgelman, R. A. 2011. “Bridging History and Reductionism: A Key Role for Longitudinal Qualitative Research.” Journal of International Business Studies 42 (5): 591–601. doi:10.1057/jibs.2011.12.

- Byun, J. H., and J. S. Shin. 2017. From Cosmetic Companies Without Faces to Beauty and Health Groups: Kolmar Korea. Seoul: Asan Entrepreneurship Review, The Asan Nanum Foundation. (In Korean).

- Chang, L.-C., X. Wang, S.-Q. Zhang, C.-B. Chen, Z.-H. Yuan, X.-J. Zeng, J.-Q. Chu, and S.-B. Tsai. 2021. “User-Driven Business Model Innovation: An Ethnographic Inquiry into Toutiao in the Chinese Context.” Asia Pacific Business Review 27 (3): 359–377.

- Čirjevskis, A. 2020. “Managing Competence-Based Synergy in Acquisition Processes: Empirical Evidence from the ICT and Global Cosmetic Industries.” Knowledge Management Research & Practice 18 (4): 1–10. doi:10.1080/14778238.2020.1801362.

- Coviello, N., L. Kano, and P. W. Liesch. 2017. “Adapting the Uppsala Model to a Modern World: Macro-Context and Microfoundations.” Journal of International Business Studies 48 (9): 1151–1164. doi:10.1057/s41267-017-0120-x.

- Demil, B., and X. Lecocq. 2010. “Business Model Evolution: In Search of Dynamic Consistency.” Long Range Planning 43: 227–246. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2010.02.004.

- Dharmani, P., S. Das, and S. Prashar. 2021. “A Bibliometric Analysis of Creative Industries: Current Trends and Future Directions.” Journal of Business Research 135: 252–267. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.037.

- Dieppe, A. 2021. Global Productivity: Trends, Drivers, and Policies. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/34015

- Easton, G. 2010. “Critical Realism in Case Study Research.” Industrial Marketing Management 39 (1): 118–128. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.06.004.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academic Management Review 14 (4): 532–550. doi:10.2307/258557.

- Faria-Silva, C., A. Ascenso, A. M. Costa, J. Marto, M. Carvalheiro, H. M. Ribeiro, and S. Simoes. 2020. “Feeding the Skin: A New Trend in Food and Cosmetics Convergence.” Trends in Food Science & Technology 95: 21–32. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2019.11.015.

- Foster, C., and M. Graham. 2017. “Reconsidering the Role of the Digital in Global Production Networks.” Global Networks 17 (1): 68–88. doi:10.1111/glob.12142.

- Foster, C., M. Graham, L. Mann, T. Waema, and N. Friederici. 2018. “Digital Control in Value Chains: Challenges of Connectivity for East African Firms.” Economic Geography 94 (1): 68–86. doi:10.1080/00130095.2017.1350104.

- Frederick, S., P. Bamber, L. Brun, J. Cho, G. Gereffi, J. Lee, and J. Cho. September 2017. Korea in Global Value Chains: Pathways for Industrial Transformation. Durham: Duke GVCC.

- Frederick, S., P. Bamber, and J. Cho. 2018. The Digital Economy, Global Value Chains in Asia. Durham: Duke GVCC.

- Fujimoto, T., and Y. W. Park. 2012. “Complexity and Control: Benchmarking of Automobiles and Electronic Products.” Benchmarking: An International Journal 19 (4–5): 502–516. doi:10.1108/14635771211257972.

- Gardner, K. 2021. Beauty During a Pandemic: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Cosmetic Industry. Doctoral dissertation, Tennessee: University Honors College Middle Tennessee State University.

- Gereffi, G., and K. Fernandez-Stark. 2016. Global Value Chain Analysis: A Primer. 2nd ed. Durham, North Carolina, USA: Duke University Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness (Duke CGGC). http://www.cggc.duke.edu/pdfs/Duke_CGGC_Global_Value_Chain_GVC_Analysis_Primer_2nd_Ed_2016.pdf

- Gibbert, M., W. Ruigrok, and B. Wicki. 2008. “What Passes as a Rigorous Case Study?” Strategic Management Journal 29 (13): 1465–1474. doi:10.1002/smj.722.

- Goldberg, P. K., and T. Reed. 2020. “The Effects of the Coronavirus Pandemic in Emerging Market and Developing Economies: An Optimistic Preliminary Account.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2020: 161–235. doi:10.1353/eca.2020.0009.

- Hanelt, A., R. Bohnsack, D. Marz, and C. Antunes Marante. 2021. “A Systematic Review of the Literature on Digital Transformation: Insights and Implications for Strategy and Organizational Change.” Journal of Management Studies 58 (5): 1159–1197. doi:10.1111/joms.12639.

- Hong, P., and Y. W. Park. 2014. Building Network Capabilities in Turbulent Competitive Environments: Practices of Global Firms from Korea and Japan. Boca Raton: CRC Press: Taylor & Francis Company.

- Hong, P., and Y. W. Park. 2020. Rising Asia and American Hegemony: Case of Competitive Firms from Japan, Korea, China, and India. Singapore: Springer.

- Jacobides, M. G., and M. Reeves. 2020. “Adapt Your Business to the New Reality.” Harvard Business Review 98 (5): 74–81.

- Jarvenpaa, S. L., and D. E. Leidner. 1999. “Communication and Trust in Global Virtual Teams.” Organization Science 10 (6): 791–815. doi:10.1287/orsc.10.6.791.

- Jonsson, A., and N. J. Foss. 2011. “International Expansion Through Flexible Replication: Learning from the Internationalization Experience of IKEA.” Journal of International Business Studies 42 (9): 1079–1102. doi:10.1057/jibs.2011.32.

- Kaiser, M., S. Goldson, T. Buklijas, P. Gluckman, K. Allen, A. Bardsley, and M. E. Lam. 2021. “Towards Post-Pandemic Sustainable and Ethical Food Systems.” Food Ethics 6 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1007/s41055-020-00084-3.

- Kano, L. 2018. “Global Value Chain Governance: A Relational Perspective.” Journal of International Business Studies 49: 684–705. doi:10.1057/s41267-017-0086-8.

- Kano, L., E. W. K. Tsang, and H. W. Yeung. 2020. “Global Value Chains: A Review of the Multi-Disciplinary Literature.” Journal of International Business Studies 51: 577–622. doi:10.1057/s41267-020-00304-2.

- Kim, J. H., and K. S. Lee. 2018. COSMAX Story 2. Maeil Economic Newspaper Publishing. (In Korean)

- Kim, E., and H. S. Ryou. 2016. ”A Case Study on Kolmar Korea Inc. in Cosmetic OEM⋅ODM Industry.” Korean Business Education Review: Korea Association of Business Education 31 (2): 279–285. In Korean.

- Kochhar, R. 2020. “A Global Middle Class is More Promise Than Reality.” In Suter, C., S. Madheswaran, B.P. Vani. (eds) The Middle Class in World Society: Negotiations, Diversities and Lived Experiences, 15–48. New Delhi: Routledge India.

- Kwon, D. December 2020. 2020 Cosmetic Industry Analysis Report. Korea Health Industry Development Institute. (In Korean)

- Laplume, A. O., B. Petersen, and J. M. Pearce. 2016. “Global Value Chains from a 3D Printing Perspective.” Journal of International Business Studies 47 (5): 595–609. doi:10.1057/jibs.2015.47.

- Leach, M., H. MacGregor, I. Scoones, and A. Wilkinson. 2021. “Post-Pandemic Transformations: How and Why COVID-19 Requires Us to Rethink Development.” World Development 138: 105–233. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105233.

- Li, F., S. Frederick, and G. Gereffi. 2019. “E-Commerce and Industrial Upgrading in the Chinese Apparel Value Chain.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49 (1): 24–53.

- Lim, C., and T. Fujimoto. 2019. “Frugal Innovation and Design Changes Expanding the Cost-Performance Frontier: A Schumpeterian Approach.” Research Policy 48 (4): 1016–1029. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.014.

- Lim, B. Y., J. H. Park, Y. C. An, and M. J. Kim. 2020. ”Growth of Cosmetic OEM⋅ODM Companies and Industrial Roles.” Journal of Society of Cosmetic Science of Korea 46 (2): 167–177. In Korean.

- Liu, J., T. W. Tong, and J. V. Sinfield. 2021. “Toward a Resilient Complex Adaptive System View of Business Models.” Long Range Planning 54 (3): 1020–1030. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2020.102030.

- P. Low and G. Pasadilla, edited by. 2016. Services in Global Value Chains: Manufacturing-Related Services. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing for Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Secretariat.

- Maliszewska, M., A. Mattoo, and D. van der Mensbrugghe. 2020. “The Potential Impact of COVID-19 on GDP and Trade: A Preliminary Assessment.” Policy Research Working Paper 9211. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/33605

- Mees-Buss, J., C. Welch, and D. E. Westney. 2019. “What Happened to the Transnational? the Emergence of the Neo-Global Corporation.” Journal of International Business Studies 50: 1513–1543. doi:10.1057/s41267-019-00253-5.

- Morea, D., S. Fortunati, and L. Martiniello. 2021. “Circular Economy and Corporate Social Responsibility: Towards an Integrated Strategic Approach in the Multinational Cosmetics Industry.” Journal of Cleaner Production 315: 128–232. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128232.

- Mudambi, R. 2007. “Offshoring: Economic Geography and the Multinational Firm.” Journal of International Business Studies 38 (1): 206–210.

- Mudambi, R. 2008. “Location, Control and Innovation in Knowledge-Intensive Industries.” Journal of Economic Geography 8 (5): 699–725. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn024.

- Nambisan, S., A. Zahra, and Y. Luo. 2019. “Global Platforms and Ecosystems: Implications for International Business Theories.” Journal of International Business Studies 50 (9): 1464–1486. doi:10.1057/s41267-019-00262-4.

- Nguyen, J. K., N. Masub, and J. Jagdeo. 2020. “Bioactive Ingredients in Korean Cosmeceuticals: Trends and Research Evidence.” Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 19 (7): 1555–1569. doi:10.1111/jocd.13344.

- Nordin, F. N., A. Aziz, Z. Zakaria, and C. W. J. Wan Mohamed Radzi. 2021. “A Systematic Review on the Skin Whitening Products and Their Ingredients for Safety, Health Risk, and the Halal Status.” Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 20 (4): 1050–1060. doi:10.1111/jocd.13691.

- Park, Y. W. 2017. Business Architecture Strategy and Platform-Based Ecosystems. Singapore: Springer.

- Park, Y. W., and P. Hong. 2012. Building Network Capabilities in Turbulent Competitive Environments: Practices of Global Firms from Korea and Japan. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Park, Y. W., P. Hong, and G. C. Shin. 2019. “Internet of Things and Original Design Manufacturing Business Model: Case Study of COSMAX.” In 2019 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), 5 (August 25-29, Hilton Portland Downtown Portland, Oregon, USA), 1–5.

- Park, J. D., and M. S. Yoo. 2016. Cosmetics ODM Third Wave: Global Brand. Seoul: Hana Financial Investment Co. Ltd. In Korean.

- Reeves, M., S. Levin, T. Fink, and A. Levina. 2020. “Taming Complexity.” Harvard Business Review 98 (1): 112–121.

- Sayer, A. 1992. Method in Social Science: A Realist Approach. London: Routledge.

- Sayer, A. 2000. Realism and Social Science. London: Sage.

- Seo, Y., A. G. B. Cruz, and I. M. Fifita. 2020. “Cultural Globalization and Young Korean Women’s Acculturative Labor: K-Beauty as Hegemonic Hybridity.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (4): 600–618. doi:10.1177/1367877920907604.

- Seyoum, B. 2021. “Product Modularity and Performance in the Global Auto Industry in China: The Mediating Roles of Supply Chain Integration and Firm Relative Positional Advantage.” Asia Pacific Business Review 27 (5): 651–676. doi:10.1080/13602381.2020.1763583.

- Shih, S. 1996. Me-Too is Not My Style: Challenge Difficulties, Break Through Bottlenecks, Create Values. Taipei: The Acer Foundation.

- Shih, W. C. 2020. “Global Supply Chains in a Post-Pandemic World.” Harvard Business Review 98 (5): 82–89.

- Song, J. 19 January 2016. COSMAX Became the World’s Number One ODM Company. Money Today. (In Korean)

- Spieth, P., S. Schneider, T. Clauß, and D. Eichenberg. 2019. “Value Drivers of Social Businesses: A Business Model Perspective.” Long Range Planning 52 (3): 427–444. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2018.04.004.

- Stallkamp, M., and A. Schotter. 2019. “Platforms Without Borders? the International Strategies of Digital Platform Firms.” Global Strategy Journal 11 (1): 58–80. doi:10.1002/gsj.1336.

- Teece, D. J. 2018. “Business Models and Dynamic Capabilities.” Long Range Planning 51 (1): 40–49.

- Vial, G. 2019. ““Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda.” The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 28 (2): 118–144. doi:10.1016/j.jsis.2019.01.003.

- Wang, L., and J. H. Lee. 2019. “The Effect of K-Beauty SNS Influencer on Chinese Consumers’ Acceptance Intention of New Products: Focused on Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM).” Fashion & Textile Research Journal 21 (5): 574–585. doi:10.5805/SFTI.2019.21.5.574.