ABSTRACT

As teachers of disability studies, working with students from the health and psychological sciences, we tackle some of our pedagogical challenges and offer productive possibilities. We begin by introducing the offerings of disability studies and then consider our first question: how might we invite disability into our teaching? We introduce a Spanish tale – Por cuatro esquinitas de nada – that, while aimed at children and not explicitly engaged with a disability, permits us to engage in inter-textual analyses of disability. We find that students move through different stages of what we term distinction, idealisation and invisibility/concealment. We then address our second question – what does it mean to teach disability? We answer this with reference to the generative practices of two teaching methodologies: disposal and disavowal. We conclude the paper by considering the importance of generating critical theories of disability.

Introduction

Our pedagogical work is best defined as interventionist: we introduce disability studies into curricula that are predominantly geared up for the training of healthcare practitioners, medics and educational psychologists. Unlike tailored disability studies programmes, we convene distinct modules (Karim) and classes (Dan), that are minor parts of programmes focused on the health and psychological sciences. While, of course, health and psychology disciplines are not monolithic, our teaching contexts are entrenched with positivistic epistemologies and individualistic models of ontology. These approaches create the perfect conditions for the germination of individual model approaches to disability; perspectives that pathologise, individualise and medicalise the disability experience (Oliver Citation1990). Teaching disability poses a number of challenges for us and our students; not least in relation to how we might introduce alternative conceptualisations of disability that are set in direct opposition to the dominant knowledge practices of our own and students’ academic settings. Here, of course, we are thinking of social oppression and minority perspectives that sociologise and politicise the disability category (Thomas Citation2004). Like other pedagogues, we draw on a variety of teaching methods including workshops, seminars, lectures, experiential and reflexive sessions in which we seek to reflect critically upon our knowledge of disability. And in these classes we adopt a number of methods, not least, methods of inter-textuality where we use existing cultural texts to interrogate them to reveal, unlock and unfold existing and counter narratives of disability.

Our approach to our own scholarship is fundamentally informed by disability studies. This transdisciplinary space emerged in direct response to the political activism of disabled people and their social movements. In terms of the Global North, from the 1970s onwards a number of social, cultural and minority models of disability emerged in the United Kingdom, Europe and North America (Goodley Citation2016) These perspectives sought to politicise, enculturise and sociologise the phenomenon of disability. Consequently, academics engaged with generating new forms of interpretation of what this phenomenon meant for society at large. For some, especially disabled academics, their agendas of work and research reflected personal experiences of disablism: the exclusion of people with impairments from mainstream life (Thomas Citation2007). For others, disability studies permitted scholars to consider questions of community living, co-existence and inclusion (Allan and Slee Citation2008). Studies of disability seek to understand the lived experiences of disability in a word constituted primarily for and by non-disabled people (Titchkosky Citation2011). Disability studies interrogates inequality, calls out differentiation that pathologises some while reifying others and contemplates the ways in which disability’s difference is too easily associated with abnormality (Baker Citation2002). Attempts to define disability are always complicating; excluding some and including others. And as Finkelstein (Citation2001) has argued defining disability will never explain disability in the here and now, the everyday, the personal and political. We believe that addressing the meaning of disability is not a descriptive task like that associated with defining some inanimate object, entity or artefact. Any understanding of disability will inevitably draw in the subjectivities of human beings who are engaged in generating such understandings (Michalko Citation2002). One of the key tasks of producing disability knowledges is to contest taken-for-granted definitions of disability and, instead, offer more relational, subjective and nuanced understandings (Tøssebro Citation2004; Thomas Citation2004; Shakespeare Citation2006). In short, any study of disability is always an encounter with human relationships. So, how can we discover understandings of disability that allow us to contemplate and create and re-create forms of being and belonging in the world? Rather than categorising disability as something out there – an object to be discovered through the practices of rationality, science and measurement – how might we think of disability as a key element of our human relationships and diverse humanities? And, further to this, what kinds of disability knowledge already exist in the world that might already be limiting how we might think of our shared humanities? These questions – and our responses to them – are made ever more complex when we consider the dominant epistemological, ontological and methodological priorities that dominate our immediate academic, teaching and learning contexts.

Our pedagogical contexts

Previous attempts to integrate disability studies approaches into the disciplines of social work, psychology and special education have been articulated (Goodley and Lawthom Citation2006; Meekosha and Dowse Citation2007; Seelman Citation2007; Oliver, Sapey, and Thomas Citation2012). We refer specifically to these disciplines because they have historically been held in opposition to the more politicised and sociological conceptualisations of disability offered by disability studies scholars. We have also chosen this literature because of its resonance with our own contexts. It is fair to say that disability or, to be more clear, at least specific versions of disability are already very much present in our immediate academic contexts. For Karim, as we shall demonstrate below, disability appears as an object of study for health and medicine in her University in Colombia. Her task involves getting students to think more critically – and sociologically and culturally – about disability. The title of her module Disability and Society clearly outlines her ambitions and aims to work with students who will be studying to become medics and healthcare practitioners. Dan also has his work cut out! He teaches into a module entitled Psychology and Learning Communities in which undergraduate students from educational and psychological studies make up the study body. A number of these students plan to pursue careers in Educational Psychology and this practitioner role is often alluded to in teaching sessions. In Educational Psychology, disability often appears as a diagnosis and a collection of labels and signifiers used by educators and psychologists. Before students even begin their first days of study with us, they already have strong senses of what (they think) disability is. These presumptions are heightened by an engagement with the imagined expertise associated with the disciplines of education and psychology; that seek to remediate, rehabilitate, treat, cure and fix students ‘damaged’ by their disabilities (Oliver Citation1990).

These a priori knowledge schemes of the authors’ student groups – which we explore later and understand as forms of medicalisation and psychologisation – are already powerfully shaping how students start their studies and frame their relationships with particular kinds of stories of disability. We already have a lot of work to do with pre-existing and very persuasive disability narratives and we are not even in the classroom together yet! From the outset, in our work with students, both of us have in mind a number of questions about our pedagogical practices:

How might we make disability appear differently in our work with students?

And in making disability appear in our classes, in particular ways, what are the pedagogical possibilities of disability?

To be part of the health sciences, for (Karim), is to feel involved in a social reality determined by a set of ideals, interests and projections, all associated with the desire to contribute to the welfare of people. That sense of implication then, alludes to occupying not only a specific place in the arena of knowledge, but also of action. A clear heritage of medicine and its healthcare approach historically has been demarcated by forms of associaiton with health and, by contrast, disease. At the heart of this thinking is the denotation of patient; the core subject to whom attention is directed where the functioning of the human body is paramount. And the meaning of treatment is often associated with recovery to a normal state. Most health disciplines arose from the needs of patients (often as the consequences of conflict and poverty) and their professionalisation has been shaped by the multidimensional ways in which human performances have been interpreted, studied and treated. In so far as health disciplines declare a direct relationship with a sense of physical and emotional well-being of people they do so, largely, by not disturbing the wider status quo. It is often presumed that it is not the role of the medic to change nor unsettle the wider socio-political status quo. That said, for Imrie (Citation2004), more simplistic, narrow and limited medicalized understandings of disability continue to be enshrined in supranational, documents such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) which lead to:

an objectification of the functioning of the human body, the urgency to highlight taxonomies or classification forms among human beings centred on physical, cognitive or emotional limitations, the distinction between the biological and social human being that ‘limit its capacity to educate and influence users about the relational nature of disability’ (Imrie Citation2004, 291)

Education and healthcare disciplines – or at least particular versions and specific forms of knowledge production – threaten to maintain power differentials between disabled people and non-disabled practitioners. While social discourses of disability centred on human rights, human development and emancipation are readily and enthusiastically supported by medical, psychological and educational students, their disciplinary communities of practice are paradoxically set up around strong tropes of rehabilitation, remediation and cure. We clearly have work to do.

Disability studies recognises the dominance of medicalised and special educational knowledge in relation to disability. We are interested too in the certainties, truth claims and empirical evidence that medical, psychological and educational sciences reproduce through an alliance with positivism (Goodley and Lawthom Citation2006). And, in contrast, we seek to urgently involve other forms of understanding about disability that are created in the social world. Hence, Karim’s course is entitled Disability and Society while Dan’s course is entitled Psychology and Learning Communities. Both emphasis the individual in the social world. Each invite an engagement with social understandings of disability.

Karim’s course Disability and Society implies the convergence of different disciplinary views, as well as the theoretical controversies that animate the debate, the constant emergence of forms of understanding, the challenge of unravelling their historical roots and the requirement to challenge normalising tendencies and the status quo pathologization of disability as a lack of autonomy. Her course works with students to promote a critical thinking as a possibility of influence in the construction of societies for all. Dan’s Psychology and Learning Communities module seeks to deindividualise understandings of learning; to reposition learning in social, cultural and political imaginaries. Disability studies becomes a necessary resource; for considering the ways in which disability categories are always constituted in educational settings as a direct response to the ways in which schools, colleges and universities work. Learning disabilities are understood not simply as a problem within particular learners but as educational sticky labels denoting learners who do not match up to the educational perogatives or the educational settings in which their learning takes place.

As teachers, we position the human being in the social world and therefore posit disability as a social scientific phenomenon. When we think about the contents and the structuring of our courses, we value pedagogical mediations that destabilise and decentralise dominant imaginaries and representations of disability. However, we do not think of pedagogical mediation as a one-way didactic communication mechanism between teachers and students. We consider pedagogy as a series of events that occur between students and, crucially, between students and teachers. And it to these examples of our pedagogy that we now turn.

How might we invite disability into our teachings? Distinction, idealisation and invisibility/concealment

A teaching method employed by Karim involves identifying intertextualities with audio-visual resources to promote a critical reasoning with undergraduate students as a condition before being exposed to a scientific literature. This means bringing in existing cultural texts that already exist the world. Many of these texts might have nothing to explicitly do with a disability but, implicitly, speak to and about disability. We are inspired by Garland-Thomson (Citation2005) methodology of retrieval; where we draw in cultural texts that have the potential for narrative recuperation. While these texts might not explicitly announce themselves as disability studies texts per se they might, nevertheless, capture some elements of the disability experience. By using these texts outside of disability studies we are, we hope, inviting students to consider disability as an intersectional concept an element of human diversity that has connections with other identities such as gender, sexuality, class, race and age. And by delving into wider cultural texts we are saying that disability is so much more than dominant texts associated with medicine, education and psychology.

Let us now turn to a story that Karim uses in her teaching with medical and healthcare students on her Disability and Society course. This story is part of her introductory workshops that seek to open dialogues around the meaning of disability .

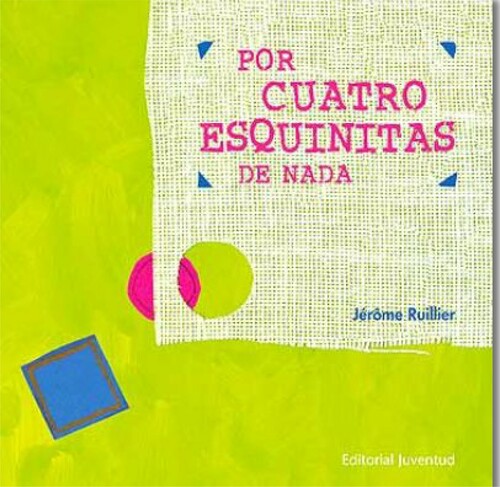

‘Por cuatro esquinitas de nada’- ‘Because of four little corners of nothing’ (Ruillier Citation2014) – is an animated book available on the web and a popular one in Spanish speaking countries. It is described as ‘A book about the friendship, the difference and the exclusion with a graphic proposal very original’. The digital version of this book https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IikZuOFfar4 came into Karim’s hands shared by friends who knew about (Karim)’s interest in disability studies. The subject of the message emailed from a friend read: ‘A very beautiful video that talks about the value of inclusion’. When we start to view the digital story, the emotions that its audiovisual proposal produces are indisputable. However, since the production of the video, a sense of contradiction has occurred; the content of the video presents exactly the antithesis of what we could represent as ‘inclusion’.

Just because the text is problematic in relation to disability does not mean that it is unhelpful. That is, this experience is configured as a possibility to produce new forms of meaning, through intertextuality (Lechte Citation1990, 58) interrogating existing cultural texts to consider how they play out with, work against, rub up against and illuminate various texts associated with, in this case, disability and inclusion.

Let us take you, the reader, through the story of ‘Por cuatro esquinitas de nada’- ‘Because of four little corners of nothing’ as deployed by Karim –.

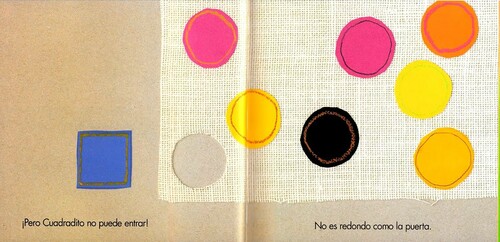

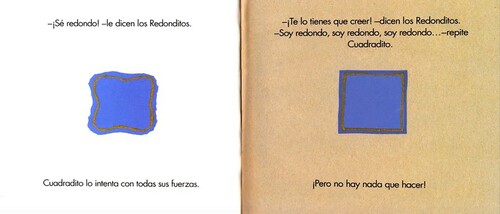

Figure 7. Page 6: Get round! – the little circles said. Little Square tried with all his might. Believe in yourself!- the little circles said. – I’m round, I’m round, I’m round- said the little square again. But nothing can be done.

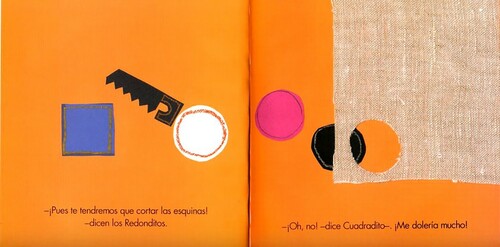

Figure 9. Page 8: Well, we have to cut the corners! The little circles said. Oh, no! – said little square – that would be really painful!.

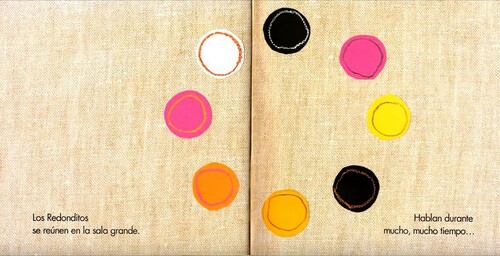

Figure 10. Page 9: The little circles have a meeting in the big room. They talk for a long, long time.

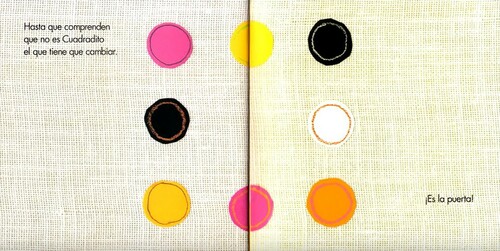

Figure 11. Page 10: They talk until they realise it is not little Square who has to change, it is the door!.

This story permits us to develop intersectional readings as a key feature of disability studies (Goodley Citation2013, 632), an opportunity to consider diverse ideologies (Barani and Wan Citation2012, 143) and to recognise pedagogical resources that can help us generate new ways of reasoning from abjection. This invites us challenge what (Rudge Citation2015) terms the stability of the sense of certainty that is often associated with traditional pre-existing meanings associated with disability (Worton and Still Citation1990, 15). Further, ‘Por cuatro esquinitas de nada’ provokes a conversation about disability, exclusion and inclusion. This story presents a dialogue between the little circles that seek to resolve with an intentional way the situation of a little square that plays with them, but when entering a house, a dilemma occurs, only the little circles can enter to the house. However, the circles note that little square wants to enter and is trying different ways to do this, but the square does not succeed, so they decide to explore other possible alternatives so that the little square can enter and they get it. It is useful to reflect, at this stage, on two pedagogical considerations. In terms of intertextuality: we recognise in this story a text that offers the possibility of putting into dialogue and in relation its statements with those of the reader and at the same time, it can give rise to new texts from that interaction. We also value the construction process of disability meaning as a product of social and cultural practices. In addition to the interaction between the story with the reader, forms of intrapersonal communication are activated and allow discovering other forms of interpretation. In terms of multimodal approaches. We recognise the role of communication dynamics in the construction of meanings and in the interaction of the variables of Field, Tenor and Mode in the attribution of meanings for social interpretation of disability.

Field, understood as the social activity, in our case, disability;

Tenor, understood as the nature of the relationship between the objects involved and;

Mode, understood as the channel or channels used in communication (Unsworth Citation2008, 2).

We also believe in the possibility of ‘expanding, expelling or modifying meanings’ (Bezemer and Jewitt Citation2010, 181) in relation to disability through communication channels such as image, sound and written word. And we recognise the role of the subjectivity of the reader as a source of transformation of meanings in combination with different semiotic channels (linguistic, visual, audio, among others). Karim regular presents ‘Por cuatro esquinitas de nada’ story to students of health sciences. This experience has been replicated for several years with different groups of students. The students are invited to relate to this story with disability (that is to say, to confront it with their imaginaries and representations). And once their projection is finished they are asked to react towards the content of the story. Karim asks the students: would you agree with the message presented by the story in relation to the way in which the little circles relate to the square? The first reactions that occur most frequently by students are paraphrased by us below:

It's a story that seems for children, but that would also serve for adults to raise awareness about the treatment of a person with a disability.

The story demonstrates the solidarity that society must have to include the different. The little square represents a disabled person who wants to look for a space in society like normal people.

The little circles represent society, that is to us and invite us to include them (in this case a little square that represents a disabled person).

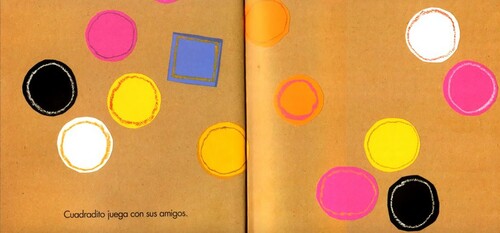

About distinction In students’ statements, the sine qua non association between the little square and a person with disability is striking and highlights the attribute of maintaining a distinction between one and the other to produce explanations about disability, in terms of what Price (Citation2007, 54) described as the constant invocation between ‘us and them’. According to the sequence of images presented in this story, we will concentrate on two of them to illuminate how Karim encourages students to interpret relationships between the circles and the square.

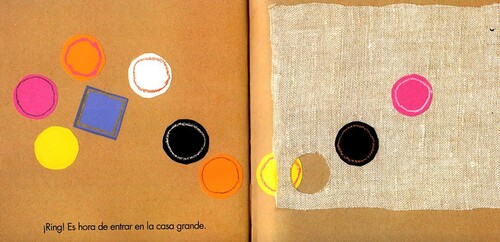

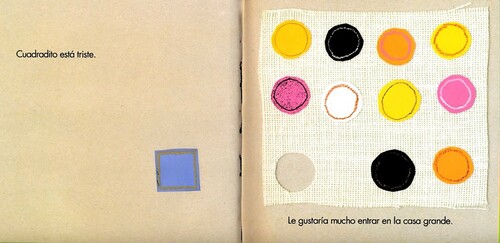

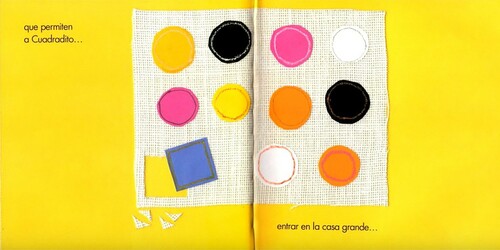

shows a spontaneous or random location of several circles and a square and a way of representing diversity through the use of different colours contained in each of these figures. However, at the same time, it is evident that one of these figures in turn is presented as ‘different’, only one, the square. shows this distinction through signalling belonging to certain places, the little circles as a whole belong each other, the little square is represented in an undetermined place. Connections can be made to social model interpretations of distinction and contrasting approaches that tend to dominate associated with the individual model.

About Idealisation - the active voices of this story are personified by the little circles, which in their discourse represent on the one hand the relationship between normality and society, as a form of idealisation of the human being and on the other the tendency for comparison.

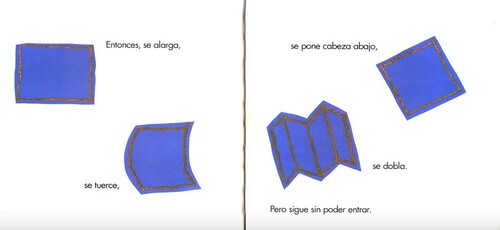

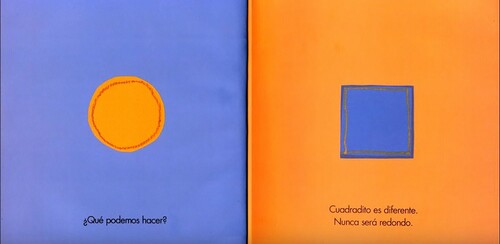

shows a relation of comparison, where little circles identify the little square as lacking in relation to the idealisation of the circle. brutally captures a curative response.

About invisibility/concealment - the tacit or passive perception that is given to the affiliation of the little square with the person with disability hides its presence at the moments of decision making and their presence is not attributed to a broader sense of participation or dialogue.

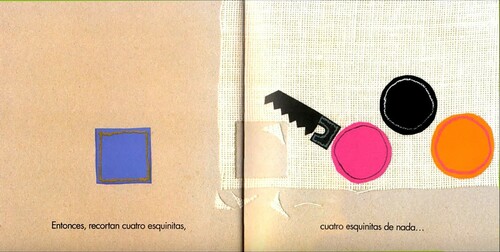

shows how the little circles that, in terms of the students, represent society, meet together to make decisions without the presence of little square. This experience induces us to think about the continuous rhetoric that is present in the discourses on disability, which advocate inclusion, equalitybut at the same time maintains a status quo of concealment or denial. When, on a daily basis, disabled people are left out of key decisions about legislation, governance, policy and practice. After these reflections with the students, where it is possible to mark different places of analysis, there were numerous reactions. Again, based on the Karim’s teaching diaries, we have paraphrased these reactions:

With this experience my brain was blown.

I feel ashamed of myself, for not noticing from the beginning that exclusion can be present and hidden at the same time through the ways in which language is communicated or used’.

As a student of health sciences, I learned that the analysis of disability is much deeper than a matter of clinical intervention to a person’.

What does it mean to teach disability? Disability, disposal and disavowal

Our second approach to disability pedagogy, provided by Dan, seeks to historicise disability. Specifically, in relation to working with students of education and psychology, it is imperative to recognise the potency of medicalising frames of disability that populate educational and psychological spaces. The task here, like the one outlined above, is to consider what it means to teach disability? Too often special educational framings will emphasise the psychological ‘realities’ of childhood disabilities. Special education is, after all, a dominant way in which disability is known. A common tactic is the ‘shopping list’ approach to introducing disability – dedicating teaching sessions to specific diagnoses and then taking each teaching session to outline these diagnoses category by category, label by label, impairment by impairment. A different approach is offered by suggesting that to teach disability is to teach the history of scientific knowledge. And specifically we might ask; how is disability’s history intimately intertwined with the histories of medicine and psychology?

Dan often draws on Michel Foucault’s classic Birth of the Clinic which details the ways in which the identification of illness, impairment and pathology was intimately tied to the generation of medical knowledge and medical practitioners. Dan poses a number of thinking points for students throughout the teaching sessions including:

Consider this: to teach medicine is to teach the history of knowledge.

The history of disability is intertwined with the history of medicine.

Ask yourself: could there be a disability without medicine?

The discovery of disability has relied heavily, in modern times, on the practices of medical practitioners such as doctors, midwives and nurses. The European renaissances of the fourteenth and the seventeenth centuries transformed the ways in which human beings conceptualised their worlds. Put simply, an unquestioned adherence to religion and rule of the monarchy flipped to a celebration of rational science and opportunities proffered by democracy. Science gifted us medicine. And as medicine hunted (and continues to hunt) for illness it does so in the search of solutions: including cure and rehabilitation (Michalko Citation2018). How we know disability today is often framed as a problem (Titchosky Citation2018). And answers to this problem are offer by health, psychological and educational sciences. Physical, sensory and cognitive impairments became known and constituted through the specialisms of psychiatry, genetics, paediatrics and neurology. At this stage it would help to consider a specific example and Dan would focus in on the label of Down Syndrome. The student group would be reminded of the racist signifier of ‘mongolism’ which was a term applied to people with Down Syndrome. Here there would be an opportunity to consider the intersections of race and disability. Then, offering a more contemporary reading, Down Syndrome would be framed in terms of trisomy 21: an additional chromosome 21. It is framed as

as a known genetic condition that causes life-long learning disabilities: a cognitive impairment also associated with physiological differences including: fine, straight hair, fissures of eyes are oblique, short, flat nose … flat knape of neck; short limbs and alterations to the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrenteric and immunitary systems (Mafrica and Fodale Citation2007, 439).

Venn (Citation1984)

1. What is it that psychology constructs?

2. What is psychology’s functioning in the social?

3. How does psychology understand its subject?

4. What knowledge foundation does psychology occupy?

1. The individual

2. Sciences of the subject – like psychology – ‘function as discourses that participate positively in the construction of the social’ (Venn Citation1984, 122)

3. As a unitary, rational subject, with a sovereign self

4. Psychology – the science that speaks of the individual;

In answering these questions through Venn Dan seeks to explore responses with students.

This brief engagement with the critical psychology of Venn reveals the science of psychology’s individualism: a science that if taken up in everyday life and practice will reproduce itself. And this reproduction of the institutional and discursive power of psychology is better known as psychologisation. Now, when psychologistion and medicalisation become the only stories told about disability then, as Michalko (Citation2018) puts it, we are in trouble. Disabled people become (i) constituted as the objects of medicine and psychology (impaired phenomena that are measured, assessed, tested and discovered through medicine and psychology) and, perhaps more worryingly, (ii) made to understand themselves only through the language of medicine and psychology. This constitution of disability as the objects and subjects of medicalisation and psychologisation requires a pedagogical intervention. Dan’s work, like Karim’s, draws on his research. For examples, Dan’s current commitment to challenging the pathologisation of disabled people is acutely informed by an ongoing research project where he is working with academic colleagues Kirsty Liddiard and Katherine Runswick-Cole alongside a group of co-researchers of disabled young women.Footnote1 This research necessitates a different way of teaching that contrasts with the medicalising tendencies of typical pedagogies of disability. In teaching disability, then, Dan suggest two strategies: disposal and disavowal.

In accordance with the interest to continue developing ways of understanding disability and to look for other places to learn together Dan proposes disposal as a useful methodology. We are encouraged to find new theoretical understandings of disability that do not rely so heavily on the dominant tropes of disability-as-limitation. In repositioning disability as a social phenomenon we immediately recognise the complexity of disability. This is a big move – for some a leap of faith – because disability as a medical or psychological problem is a well-worn story that dominates our cultural imaginaries. We seek to challenge students and ourselves to dispose of these taken-for-granted and often built from the experiences of teaching disability. We remind ourselves that regardless of the interventions of educators, psychologists or medics, the exclusion of disabled people remains a reality. Our teaching seeks to create other ways of making disability appear. We often start from the suspicion that one of the reasons why discourses and social practices that continue to be replicated to a greater or lesser extent in situations involving disability have been based on the established forms of meaning that subjects make about the disability. And these established social representations have been anchored mainly in the distinctions made between human beings. One of the latent problems in common conceptions of disability, is that disability is taken for granted, that it is determined already as a consequence of some impairment of the body or mind. It is therefore imperative to dispose of this taken for granted knowledge – these tacit models, typologies, stereotypes, tropes and stories of disability – to abandon what we think we already know already about disability. This practice of disposal is especially important in spaces of educational, health and psychological sciences because the kinds of stories being told about disability have long histories: so long that old, well-worn stories now mascaraed as truth claims. Experience shows us that through the teachings on disability, when you achieve an intra-subjective confrontation (within the person) with the form in which the meanings of disability are produced, you can achieve a dismantling process that allows disability to appear in other forms, to search for other forms of relating, other narratives or even to discover how representations of oppression, exclusion, discrimination or invisibility continue to be hidden under the veil of discourse that is ‘socially constructed’. This can be verified in academic documents, awareness-raising videos, policies, laws, publicity campaigns, among others.

Alongside disposal we also offer the strategy of disavowal. In previous writing one of us has spoken about the potency of thinking around the disavowal of disability (Goodley Citation2016). Often this is used as a synonym for denial or repudiation. However, in a social psychoanalytic sense, disavowal refers to the simultaneous desire of and disgust with a given object. To disavow another is to stare at them whilst staring through them; to be drawn to and the very same time one is repulsed; to want and to reject some entity in equal measure. This ambivalent relationship with another can be used to explain the competing ways in which disabled people are responded to by non-disabled culture. Disabled people are often the objects of another’s (non-disabled) stare (Garland-Thomson Citation2009). It is not simply the case that disabled people are rejected, ignored, marginalised (though this of course is a common disabling practice): disabled people report being treated as objects of curiosity, fascination and interest on the part of others. In our disability teaching, we would want to identify and unpack everyday examples of disavowal. Here are some that Dan has already collected which are shared with students;

You get that all the time people stare, people comment, or people … I would rather people said to me, ‘What’s wrong?’ rather than just stare. Then you can hear them as soon as you walk past, [whisper sounds]. (Jemma, mother of a disabled child) reported in (McLaughlin et al. Citation2008).

When people comment on my impaired experience I am shocked, amused and angered all at once (Hewitt Citation2004)

‘Why did you not have a test before you had your child’ (A stranger’s question to the mother of a disabled child).

‘What happened to you then?’ (A stranger’s question to a disabled woman in a supermarket).

‘Well, are you going to do something funny, or what? (Question asked of a disabled activist researcher with restricted growth).(Goodley Citation2016)

In each of these examples, there is the risk that just as disability is responded to as an object of curiosity it simultaneously risks being erased by the commentary or reactions of the non-disabled social actors. This contradictory practice is something that we want to promote in the thinking of our medical and healthcare students. We would want these students to consider the ways in which they disavow disability through their desire to know disability through the very medical and health discourses that they have been trained to utilise. We want them to ask: What is it that attracts you to disability at the very same time that your knowledge risks denigrating disability? One pedagogical possibility here would relate to a series of statements that are not uncommon in medicalising discourses of disability:

The desire for diagnosis inevitably lead to a search for cure.

The identification of autism within an individual means that from the moment of diagnosis any behaviour, whim or ambition of that individual is understood as a symptom of autism.

Deaf people want to hear.

The door is adjusted for Little Circle to enter the room but Little Circle remains conspicuous in his Otherness.

Conclusion: Promoting critical theories of disability

The pedagogical moments outlined above hopefully lay down some foundations for the development of critical awareness on the part of students as they contemplate disability (Garzón-Díaz Citation2015, 72). We hope too that disability discourses that functioning as truth are contested while new interpretations are given space and time to emerge. It is only through critically addressing knowledge claims around disability that our students will develop critical faculties. Moving forward in the processes of theorising about disability is to produce new interpretations, and reconfigure mental models to boost transformative actions in the social. We seek to decentralise traditional ways of disability representation in society to produce new meanings.

Teaching Disability is configured as a process through which mental models are staged through the expansion of communication channels. These modes of communication take place in a learning environment or ‘sensory field’ (Marchetti and Cullen Citation2015a) that provokes different emotions, forms of reasoning and discovers many contradictions and correspondences. In other words, critical theories of disability can be developed as a consequence of a relational dynamic in which students and teachers learn to discover but also to deconstruct (Álvarez and Álvarez Citation2012). To contest the certainties of medicine and psychology inevitably leads to a position of relativism: where the anchored and fixed truths of science give way to be replaced by a thousand stories of many theorists. But this relativism should not be confused with nihilism nor a rejection of important counter-narratives. In contrast, by contesting health, psychological and educational sciences, we are left with an awareness of the power of stories to make sense of – or mystify – our lives.

Telling our stories or being part of the audiences of the stories of others, allows us to communicate, relate and react from different places we occupy. To produce reflections that can configure praxis or critical awareness in front of a reality. Through mediations and communication resources such as multimodal ones described above, studies in disability activate and mobilise the thinking of audiences to produce another style of meanings, which even challenge traditional forms of communication and even language, flexible relations between teacher and students and between peers (Marchetti and Cullen Citation2015b). This might increase trust when participating in share learning communities and bring together students from different disciplinary settings to converge on the study of disability.

In our particular case, we want to highlight the value and influence of mediations and pedagogical processes in the way of disability reasoning is represented, because they allow us to broaden and controvert the ways of understanding about it from the perspective of the direct experience of the audiences in relation to the pedagogical experience. In other words, the human dispositions that are bring into play in a pedagogical experience could be configured as determinants in the ways in which social ideas and practices around disability are socially constructed or deconstructed.

Acknowledgements

Dan would like to thank and acknowledge the Economic and Social Research Council for their funding of the ES/P001041/1 Life, Death, Disability and the Human: Living Life to the Fullest that has informed the writing of this paper. https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=ES%2FP001041%2F1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The project Dan refers to Life, Death, Disability and the Human: Living Life to the Fullest is a live project being undertaken in the UK. More details of the research can be found here: https://livinglifetothefullest.org/

References

- Allan, J., and R. Slee. 2008. Doing Inclusive Education Research. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Álvarez, G., and G. Álvarez. 2012. “Análisis de ambientes virtuales de aprendizaje desde una propuesta semiótico integral.” Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa 14 (2). https://redie.uabc.mx/redie/article/view/311.

- Baker, B. 2002. “The Hunt for Disability: the new Eugenics and the Normalization of School Children.” Teachers College Record 104 (4): 663–703. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9620.00175

- Barani, F., and Y. Wan. 2012. Critical Theories and Polyphony: Towards a Great Global Dialogue, 143–150.

- Bezemer, J., and C. Jewitt. 2010. “Multimodal Analysis: Key Issues.” In Research Methods in Linguistics, 180–197. London; New York: Continuum.

- Finkelstein. 2001. A Personal Journey into Disability Politics. https://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/library/finkelstein-presentn.pdf.

- Garland-Thomson, R. 2005. “Feminist Disability Studies.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 30 (2): 1557–1587. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/423352.

- Garland-Thomson, R. 2009. Staring: How we Look. Oxford . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Garzón-Díaz, K. 2015. “De la inclusión a la convivencia: las narrativas de niños y niñas en diálogo con políticas públicas en discapacidad.” Revista de La Facultad de Medicina 63: 67–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v63n3sup.49343.

- Goodley, D. 2013. “Dis/Entangling Critical Disability Studies.” Disability & Society 28 (5): 631–644. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.717884.

- Goodley, D. 2016. Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Goodley, D., and R. Lawthom, eds. 2006. Disability and Psychology: Critical Introductions and Reflections. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hewitt, C. 2004. “Sticks and Stones.” In Queer Crips: Disabled Gay Men and Their Stories, 117–120. New York: Harrington Park Press.

- Imrie, R. 2004. “Demystifying Disability: A Review of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.” Sociology of Health & Illness 26 (3): 287–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2004.00391.x.

- Lechte, J. 1990. Julia Kristeva. London: Routledge.

- Mafrica, F., and V. Fodale. 2007. “Down Subjects and Oriental Population Share Several Specific Attitudes and Characteristics.” Medical Hypotheses 69 (2): 438–440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.043.

- Marchetti, L., and P. Cullen. 2015a. “A Multimodal Approach in the Classroom for Creative.” CASALC Review 1: 39–51.

- Marchetti, L., and P. Cullen. 2015b. “A Multimodal Approach in the Classroom for Creative Learning and Teaching.” CASALC Review 5 (1): 39–51.

- McLaughlin, J., D. Goodley, E. Clavering, and P. Fisher. 2008. Families Raising Disabled Children ;Enabling Care and Social Justice. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Meekosha, H., and L. Dowse. 2007. “Integrating Critical Disability Studies Into Social Work Education and Practice: An Australian Perspective.” Practice 19 (3): 169–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09503150701574267.

- Michalko, R. 2002. The Difference That Disability Makes. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Michalko, R. 2018. Teaching Disability Studies and Disability as Teacher. Presented at the Storying Disability: Wrecking Disability, iHuman University of Sheffield. http://ihuman.group.shef.ac.uk/storying-disability-wrecking-disability/.

- Oliver, M. 1990. The Politics of Disablement. https://ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/login?url=https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20895-1.

- Oliver, M., B. Sapey, and P. Thomas. 2012. Independent Living and Personal Assistance, 74–97.

- Price, M. 2007. “Accessing Disability: A Nondisabled Student Works the Hyphen.” College Composition and Communication 59 (1): 53–76.

- Rudge, T. 2015. “Julia Kristeva: Abjection, Embodiment and Boundaries.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Social Theory in Health, Illness and Medicine, edited by F. Collyer, 504–519. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137355621_32

- Ruillier, J. 2014. Por Cuatro Esquinitas de Nada. Barcelona: Juventud.

- Seelman, K. 2007. “Trends in Disability: Transition From a Medical Model to an Integrative Model.” In Encyclopedia of Special Education, edited by C. R. Reynolds and E. Fletcher-Janzen, 2060–2062. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Shakespeare, T. 2006. Disability Rights and Wrongs. New York: Routledge.

- Thomas, C. 2004. “How is Disability Understood? An Examination of Sociological Approaches.” Disability & Society 19 (6): 569–583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759042000252506.

- Thomas, C. 2007. Sociologies of Disability and Illness: Contested Ideas in Disability Studies and Medical Sociology. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Titchkosky, T. 2011. The Question of Access: Disability, Space, Meaning. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Titchosky, T. 2018. The Educated Sensorium & the Surprise of Disability Studies. Presented at the Storying Disability: Wrecking Disability, iHuman University of Sheffield. http://ihuman.group.shef.ac.uk/storying-disability-wrecking-disability/.

- Tøssebro, J. 2004. “Introduction to the Special Issue: Understanding Disability.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 6 (1): 3–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15017410409512635.

- Unsworth, L. 2008. “Multimodal Semiotic Analyses and Education.” In Multimodal Semiotics: Functional Analysis in Contexts of Education, 1–14. London; New York: Continuum.

- Venn, C. 1984. “The Subject of Psychology.” In Changing the Subject, edited by J. Henriques, W. Hollway, C. Urwin, C. Venn, and V. Walkardine, 119–152. London: Methuen.

- Worton, M., and J. Still. 1990. Intertextuality: Theories and practices. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/35932/.