ABSTRACT

This exploratory qualitative study problematises how Pakistan’s public-school education shapes female identities, employing compulsory school textbooks. Drawing on Foucault’s Discourse Analysis and other selected notions, the study also analyses 12 teachers’ and 424 students’ perspectives on this. The findings highlight Pakistani females’ disproportionate and gendered stereotypical social representations in textbooks, which the teachers further reinforce through teaching/social practices in schools. Discursively constructed, most students identify with these and reproduce them when conceptualising an ideal Pakistani woman. The study also underlines how an education system, apparently promising equity and inclusiveness, can be incredibly exclusive, ‘guiding’ the country’s 50% female population to make homemaking their destiny. This education perpetrates social othering, encourages self-righteousness and privileges men over women. Social ramifications of this education entail exclusion and disempowerment of Pakistani women as a social category. This has serious implications for certain sustainable development goals SDGs, 2030, inter alia.

Introduction

The relationship between gender and education is largely discussed in the context of gender equality and social factors preventing women’s uninterrupted access to educational sites (see UNESCO Citation2018). However, the issue of gender equality is far too intricate. Given complex social dynamics embedded in power relations, it needs to be viewed from various other vantage points as well, for instance, ideological. Camouflaged with the common educational parlance of equity and inclusivity, a public-school education system can also be used to constitute particular gendered identities for political reasons, as seen in the case of Pakistan (see Qazi and Shah Citation2019). Notshulwana and Lange (Citation2019, 107) hold that ‘[i]n a school setting hegemonic notions of femininity and masculinity are often reified by both teachers and learners … which perpetuates the status quo’.

This exploratory qualitative study conducts a thematic analysis of Pakistan’s compulsory national curriculum school textbook discourses for years 9–12 to problematise how these represent girls/women for students to conceptualise a model Pakistani woman. Taking a holistic view, it also aims to study the participants’ social world experiences of these in Pakistan’s public schools located in Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan. Therefore, guided by the emerging themes from textbook data, it first draws on teachers’ perspectives to examine how they teach these discourses to students in classrooms. Then, it records the students’ reactions to understand the conforming/contesting strategies they use to position themselves vis-à-vis their discursively constructed positioning.

In the next two sections, we will outline our conceptualisation of gender identity. Similarly, while identifying the research gap in the context of Pakistan, we shall explore the links between gender identity and public-school education and the way the latter has been used for constituting female identities globally.

The notion of gender identity and education

Generally, gender identity can be defined as how an individual perceives herself/himself as a female or male irrespective of their biological sex. Unlike the latter, gender is an unstable social category and numerous factors contribute to its conceptualisation (see Butler Citation2006). These include ‘the multiplicity of cultural, social, and political intersections in which the concrete array of ‘women’ are constructed’ (Butler Citation1999, 19–20). Illuminating social practices involving the construction of women, feminists generally take ‘the patriarchal structure of society’ as a starting point where ‘the term “patriarchal” refers to power relations in which women’s interests are subordinated to the interests of men’ (Weedon Citation1993, 2). Weedon (Citation1993, 2) further argues that ‘in the patriarchal discourse, the nature and social role of women are defined in relation to a norm which is male’. Similarly, women are considered ‘naturally equipped’ for the role of ‘wife and mother’ as they are thought to possess those qualities which are ‘naturally feminine’ such as ‘patience, emotions and self–sacrifice’ (Weedon Citation1993, 3). On the other hand, ‘the “aggressive” worlds of management, decision-making and politics call for masculine qualities’ (Weedon Citation1993) even in women.

Since the second wave of feminism in the West in the 1970s, education-system-actors have become conscious of gender stereotyping and women’s underrepresentation in curricula (see Brunell and Burkett Citation2019). However, as Notshulwana and Lange (Citation2019, 107) argue, ‘in spite of the attention gender and education have received since the 1970s in Western countries … existing inequalities have not been eradicated’. The school textbooks in many parts of the world still underrepresent women and reinforce gendered stereotypes. For example, Mayer (Citation2000, 110) argues, Northern Ireland, to maintain its unionist identity, ‘draws heavily on warrior symbols, thus reflecting the staunchly patriarchal values of unionism … and its exclusion of women from political leadership’. Chege’s (Citation2006) study unpicks the ideological re-workings of teachers’ perceived notions about African men and women and the role they play in the construction of girls’ sexualised identity. Thus, they not only construct them as ‘inferior to boys but also, as objects of sexual ridicule’ (Chege Citation2006, 25).

The case of gender identity construction in Pakistan, employing school textbooks, is rather intriguing. Given Islam is Pakistan’s overarching national identity, the state instumentalises the religion to serve ‘as a major ideological vantage point that influences all other textbooks-based national identity signifiers’ (Qazi Citation2020, 243). This includes gender, amongst others. Qazi (Citation2020) argues that, historically, Islam has been employed in textbooks as a ‘technology of power’ (Foucault Citation1977) for the ‘official surveillance and moral policing for those Muslim females who do not conform to the religiously prescribed propriety standards’ (Qazi Citation2020, 258). Agha, Syed, and Mirani (Citation2018) examine Sindhi language textbooks of grades 1–5, being taught in the Sindh province. The ‘pictorial and textual analysis’ of their study ‘confirms the salient features of patriarchal ideology being reproduced through the textbooks’ (Agha, Syed, and Mirani Citation2018, 17). Similarly, the study of Jabeen, Chaudhary, and Omar (Citation2014) examines years 1–5 textbooks, taught in the Punjab province, to identify areas of gender stereotyping. They conclude that the literature being taught in these books ‘reflects male chauvinism’ (55) where women are represented as men’s subordinate. The findings of Ullah and Skelton’s (Citation2013, 183) study of years 1–8 textbooks, taught in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province, argues that ‘ideologically driven’ these textbooks are ‘embedded with gender biased messages and stereotypical representations of males and females … – and contribute to the perpetuation of gender inequality’.

Notwithstanding several pieces of research in the area of gender studies that emerged from Pakistan in the last few years, this study is still relevant. It is in many ways different from the studies conducted earlier. As shown above, they were generally limited to a single province of the country with a focus on the evaluation of textbooks only. Similarly, the textbooks sampled were taught at years 1–8. This study, on the other hand, analyses all compulsory textbooks being taught at years 9–12, mandated under the latest National Education Policy, 2017. It is conducted in schools that fall under the jurisdiction of the Federal Capital of Pakistan Islamabad, where students from all provinces of Pakistan study (see next section). This study is holistic as it is not limited to the study of textbooks only. It also problematises the role of other education-system-actors including the school as a structure, teachers and the students themselves in constituting students’ gendered national identities. Similarly, the study will investigate if the Government of Pakistan, being a signatory of Education for All (EFA), could achieve the goal of eliminating gender stereotyping/bias, as promised in the current National Education Policy, 2017. Moreover, this study examines the issue of gender in light of the United Nation’s Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 2030.

Data analysis and theoretical framing

The data presented in this paper was collected from three boys’ and three girls’ public schools located in Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan. First, the study drew on the textual data collected from three compulsory textbooks, namely English, Urdu and Pakistan Studies for grades 9–12. The purpose was to understand how these represent girls/women for students to conceptualise a model Pakistani woman. These textbooks are published by the National Book Foundation of Pakistan (see http://www.nbf.org.pk/) and Punjab Curriculum and Textbook Board (see https://pctb.punjab.gov.pk/). The board is a public body which describes itself as an institution with a ‘vision of nation building through quality textbooks’ (ibid.). The selection of these subjects is purposive and is based on my background knowledge of these as a teacher educator. The analysis of these textbooks unpicked consistent patterns emerging from their discourses with the potential to perpetuate gender stereotypes. These were coded using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006, 79) advice that involves ‘identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) in the data’. The emerging patterns were categorised following the principle of integration and aggregation. The process involves putting together those individual bits of information from the coded data that are similar in meaning, and creating new thematic categories (see Given Citation2008). We applied the same principles during the thematical categorising of textbook data. In addition to that, the notion of female representation was determined quantitatively, considering their numerical pictorial representation in textbooks and as textbook authors.

A thematic analysis of emerging themes from the sampled textbook discourses afforded a guideline to collect teachers’ and students’ perspectives on women. This was done by employing semi-structured interviews with teachers and focus-group interviews and participatory tools with students of grades 9–12 (see the next paragraph for full detail). These data tools were implemented on the sampled population located in 6 public schools in Islamabad. The selection criteria for schools and students considered the fact that Islamabad is the capital city of Pakistan, and, therefore, its schools are expected to broadly represent all of Pakistan. Also, in terms of social class, the population of the selected schools represents the middle/lower middle class of the country which makes up the representative majority of the country. Notwithstanding the medium of instruction, this class of Pakistani students studies the same national curriculum textbooks in the same public-school system. These count 196,998 in total and facilitate 28.68 million students across the country (Government of Pakistan, Pakistan Education Statistics 2015–16, 2017, 5). Notwithstanding the selected schools and participating students are located in the urban setting, both were randomly selected. The issue of access to rural schools prevented their inclusion in the sampled data. However, as discussed earlier, all urban and rural schools under the jurisdiction of the Federal Capital Islamabad follow the same education system. The rural schools teach the same national curriculum textbooks as the urban ones. Therefore, the probability of obtaining substantially different data from rural schools was rather slim. The rationale to collect data from the students of grades 9–12 from the sampled schools, and not others, is purposive. It lay in the fact that these students were the senior-most and had undergone a relatively long experience of ‘structured becoming’ (Jenks Citation2005, 11) in these schools. Likewise, the teachers’ selection was also purposive as only those teachers were selected who taught the students the sampled subjects, for the reason discussed earlier.

The total teacher study-participants were 11 (5 male and 6 female), representing Punjabi, Sindhi Urdu-speaking, Pathan and Kashmiri ethnicity. They all had a master’s degree in the relevant subjects with a service span of 7–29 years. The whole sampled student population for participatory tools activities, from all six schools, included 209 boys and 215 girls. Of these, 56 students also participated in focus group interviews. These students came from most major ethnic groups living in Pakistan and could be said to be broadly representing their actual population in the country: Punjabi 51%, Pashtuns 25%, Hindco/Pahari seven percent, Saraiki from South Punjab three percent, Hindco people from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa five percent, Urdu from Sindh two percent, Sindhi from Sindh five percent, Baluchi from Baluchistan one percent, and Shina and Balti from Gilgit-Baltistan one percent (see Pakistan Bureau of Statistics Citation2020).

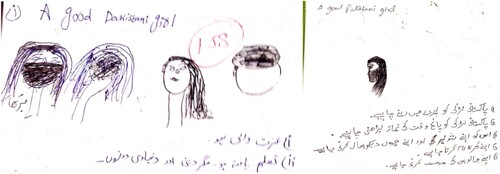

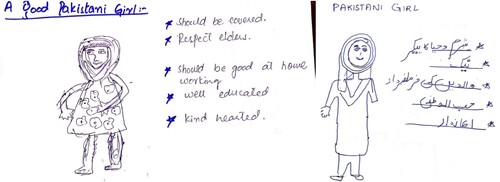

For teachers’ interviews and students’ focus group interviews, a semi-structured interview guide was constructed focusing primarily on how teachers and students imagine an ideal Pakistani representative woman. The teachers were interviewed individually, whereas students were divided into seven focus groups. The population of each focus group ranged from seven to nine. Participants were free to use either English or Urdu – Pakistan’s national language. The interviews were audiotaped, and it took 15 days to collect the complete field data. Before the implementation of data tools, the BERA’s (Citation2011) guidelines were followed. These mandate student participants’ and their parents’ informed consent, participants’ and institutions’ anonymity and assurances regarding the use of data solely for research purposes. For the analysis of the field data, the same procedure of integration/aggregation of information for thematic coding/sub-coding of categories, as in the case of sampled textbooks, discussed above, was employed. To substantiate findings drawn from students’ focus-group interviews, the participatory tools method was implemented. This method involves drawing images (animate/inanimate symbols/objects), sketching or outlining a problem tree to express feelings/reactions, etc (see Punch Citation2002). O’Kane (Citation2001, 126–127) thinks that participatory techniques ‘can enable children and young people to talk about the sorts of issues that affect them’. Participatory tools required all 424 student-participants to draw images of a Pakistani girl/woman who in their opinion represents/not-represents Pakistan and label the images with desirable/undesirable characteristics they expect to see/not see in a model Pakistani woman.

The data in this study were analysed using the lens of Foucault’s Discourse Analysis (Citation1980, Citation1987, Citation1988, Citation1993) and particularly his notions of the ‘subject’ constitution including ‘technologies of power and self’, ‘regime of truth’, ‘subject’ constitution and ‘agency’. Foucault (Citation1987, 18) argues that technologies of power ‘determine the conduct of individuals and submit them to certain ends or domination, [leading to] an objectivising of the subject’. On the other hand, technologies of the self ‘permit individuals to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and the way of being, so as to transform themselves’ (Foucault Citation1987). Foucault views both these technologies as functioning in coordination for making the individuals into subjects. In order to analyse how a subject is constituted, Foucault insists we must consider ‘the interaction between those two types of techniques – techniques of domination and techniques of the self’ (Citation1993, 203). To understand that, Foucault maintains, we need to investigate the networks of knowledge, historical conditions, socio-cultural and political processes and the conduct/agency of individuals who act within these structures. These networks constitute the ‘regime of truth’ (Foucault Citation1980, 131), and the individuals negotiate their positions operating within its constraints. Foucault’s subject is therefore context-dependent and is socially constructed through ‘a body of determined practices and discourses’ (Foucault Citation1987, 49). It is an individual transformed under the effects of external events (social, political, cultural etc.) as well as his/her own approach/actions vis-à-vis these events which make him/her a subject. This is a fascinating insight which this study operationalises in the context of this study to understand (a) how Pakistan’s ‘regime of truth’ through the ‘production of truth’ (Foucault Citation1980, 93), contained in national textbooks, and its dissemination in schools, under the supervision of subject teachers, transforms the students, (b) to what extent the students allow the teacher-mediated textbook ‘truths’ to influence themselves resulting in their subjectivation and (c) to what extent the students are able to challenge the surrounding networks of ‘legitimate knowledge’ (Apple Citation2004), wielding their ‘agency’. Similarly, I conceptualise the school as a structure where the interplay of both the technologies of power (textbooks, teachers and school) and technologies of the self (students’ conforming/contesting strategies to the propagated ideas) occurs to transform the individuals (the students) into subjects. The collaboration of technologies of power and technologies of the self can also be conceptualised as an interaction between structure and agency which ‘determine [the] conduct of individuals [the Pakistani students in this context]’ (Foucault Citation1988, 18). Similarly, it is the study of the interplay of both these technologies within the constraints of school. It is the place of the circulation of the ‘true’ statements amongst students. These statements are generated by employing the national textbooks by the ‘authorised’ people (education system actors). These are then disseminated by the schoolteachers in school classrooms for students’ gendered national identity construction/s of Pakistan.

Study findings

In the following sections, the findings from the textbooks of English, Urdu and Pakistan Studies of grades IX-XII are presented. These are followed by the presentation of field-data results collected from the teachers and students of the sampled schools.

Textbook findings

A thematic analysis of the sampled textbook data points to Pakistani education-system- actors’ gendered approach towards women. This is notwithstanding the fact that the textbooks were mandated under the National Education Policy 2017, which in one of its stated objectives aims ‘[t]o achieve gender parity, gender equality and empower women and girls within the shortest possible time’ (13). This study identifies three areas of female marginalisation in textbooks. These include her (a) underrepresentation as a textbook author, (b) inequitable pictorial representation in textbook pages and (c) gendered representation through stereotypical domestic or supportive roles. Furthermore, her choice of clothes is flagged as a marker of her propriety and faithfulness to Pakistan and its Islamic identity.

Authorship

There are two English textbooks for grade XI with 38 literary segments altogether i.e. poetry, plays, and short stories. Interestingly, all the works included in these textbooks have been written by male authors. The English textbook for grade XII has 15 lessons; of which 14 are authored by male authors. Similarly, all lessons included in the Urdu textbook for grade IX are written by male writers; whereas, in the textbook of grade X, just 2 out of 25 are written by female writers. Urdu textbooks for grades XI and XII together have 70 lessons and follow a similar pattern. Except 11, all have male authors. The Pakistan Studies textbooks for the sampled grades, on the other hand, do not have authors but compilers. A review of these shows that of 11 compilers, only 1 is a female.

Pictures

A study of the pictorial representation of women in these textbooks conveys a similar message. The total human images appearing in the English textbooks for grade IX-XII count 32. Interestingly, only 7 of these are women. Even these 7 images figure in the textbooks of grade IX and X, signalling the higher the grades the more the invisibility of women. All 11 human images showing in the Urdu textbooks (IX-XII) are men. Similarly, in the Social Studies textbooks (IX-XII), only 2 out of 11 are women.

Social roles

All sampled textbooks (IX–XII) appear to reproduce gender stereotypes by representing women predominantly in domestic or supportive roles. In the English textbook for grade IX, a lesson titled Hazrat Asma (32–45) discusses an Islamic icon from the history of Islam for students to emulate. It represents her mainly in a domestic role involving food preparation and delivering it to her father (33). Similarly, lesson 9, All is Not Lost (93–103), presents the story of a female nurse. She is presented as fully covered in Pakistan’s national dress Shalwar Kameez and Dupatta. The descriptive words used to portray her character include ‘perseverance’, ‘docile’ and ‘caring’ (94). She is shown in the supportive role of a nurse helping a male doctor. However, grade IX, unit three, Media and its Impact (21–31), presents one Miss Ayesha in the professional role of a teacher. She appears to be encouraging students to participate in classroom discussions on the topic Role of Media and its Impact (22). This is notwithstanding a career in teaching is traditionally considered more suited to women. There is no lesson in the English textbook for grade 10 which might represent women in vocational roles.

The social roles in which the Urdu textbooks present women are strictly domestic/supportive. In the lesson, Nasooh and Saleem ki Guftagu (A Conversation between Saleem and Nasooh) (28–34), a mother is depicted as enamoured with the patriarchal role of her husband. Advising her son, she insists ‘talk to him [your father] very politely, showing utmost respect’ (30). The father is portrayed as a family patriarch in a ‘rightful’ authoritative role, who is fully supported by his wife. Similarly, the lesson, Araam –o–Sakoon (Peace and Comfort 47–55), presents a woman who is very kind, docile, and caring towards her husband. Another lesson, Paristan ki Shahzadi (The Princess of the Fairyland 29–40), in grade 10 Urdu textbook presents an old woman named Sayyadani Bi. She is being commended for her exceptional prowess in stitching and darning. So much so that ‘even the city’s social elite (Begmat/ madams) are impressed by her’ (29). She is also exemplified as a person who after having deteriorated her eyesight is now focusing on transferring her ‘prized domestic skills’ to the younger generation. This aspect is discussed as follows: ‘in the afternoon she teaches them the art of sewing and darning and trains them in the art of embroidery. In the evening she teaches them food recipes in the kitchen’ (30). The story, Akbari ki Himaqtain (Stupidities of Akbari 26–33), is about a newlywed woman. She is portrayed as ‘foolish’ because she is not good at handling domestic affairs and refuses to live with her in-laws. On the other hand, her husband Muhammad Aaqil is portrayed as a man of vision and manners: ‘if Aaqil were short-tempered, they would have divorced. But he always used his wisdom’ (32). These discourses demarcate gender roles in Pakistani society and are used to construct particular gender identity.

Pakistan Studies textbooks (IX–XII) offer self-contradictory and confusing narratives on the potential of Pakistani women. The textbook for grade IX in the lesson Population of Pakistan (143–158) regrets the fact that ‘Pakistani women make up only 2.02% of the total workforce of the country and that their contribution to the economy of the country is just 13.5%’ (145). On the other hand, the textbook of grade X rejoices on Pakistani women’s lower birth-rate stating the ‘rate of birth of males in Pakistan is more than that of females. These facts can be declared to be very suitable for economic development and activities’ (96–97). To consolidate the existing patriarchal structures, chapter 6 of grade XI1 textbook refers to a survey conducted in the UK maintaining ‘98% of the women expressed an earnest desire to return to their family life but found themselves helpless because neither the husband nor the father was ready to welcome them back’ (122). The notion of ‘family life’, in this context, suggests women being limited to household chores without a career in any field. Interestingly, the textbook does not provide a reference to the survey, thus school education is being used only to consolidate patriarchal values. It also presents Pakistani society as an Islamic society and highlights the rights of women in Islam:

The head of the family is an elderly man, women are honoured.

Women are eligible to get their share from their father’s and husband’s inheritance.

The majority of women is chaste and observe ‘purdah’

Shalwar Kameez is the common woman attire, with dupatta and chadar worn on the head.

She can design her house (121)

Thus, she is represented as a dependent body who can rejoice in the honour which men accord her in the name of religion and traditions.

The findings drawn from the thematic analysis of the sampled textbooks show that they completely lack in representing Pakistani women in powerful/successful female role models for students to emulate in life. These mostly represent them in stereotypical domestic roles, thus constructing a conventional gendered identity. Other modes of marginalisation include their underrepresentation as a textbook author and in the pictorial display of female images. Even when women’s images appear, they are represented in stereotypical domestic/supportive roles. Their overall representation as a textbook author and in pictures, in comparison with men, is 15% (30/199) and 20% (11/54), respectively. The study confirms that textbooks constructed under the new National Education Policy 2017 are hardly any different from the textbooks constructed under previous policies. Similarly, it confirms that the element of gender stereotyping/patriarchy is as much present in these textbooks as in those being taught in Sindh, KPK and Punjab as found by other scholars, mentioned earlier (see Agha, Syed, and Mirani Citation2018; Jabeen, Chaudhary, and Omar Citation2014; Ullah and Skelton Citation2013). This female representation in the textbooks has far-reaching implications for Pakistani society (see Discussion). In the following sections, we shall problematise teachers’ and students’ positions on the question of gender.

Gender in teachers’ perspectives

Responding to the question of how a true Pakistan girl/woman should be like in their opinion, both male and female teachers were found preoccupied with the idea of an ‘appropriate/inappropriate’ female outfit. They said that they had always taught students the importance of proper dressing. Male teachers’ perspectives are as follows: TG: ‘First dressing – [it] should be decided on demands of religion … and then comfortability [being comfortable]’. Teacher H strongly related morality with the way women dress up, ‘A woman should be a role model … she should have good morality and ethics’. On probing further as to what he meant by ‘good morality’, he replied, ‘[o]ur morality originates from our religion … there should not be any vulgarity in dressing’. Explaining ‘vulgarity’ further, he maintained, ‘body parts should not be visible. They [women] should not accentuate them [wearing tight dresses]’. TL strictly associated women dressing with Pakistaniat [the true spirit of being Pakistani] arguing, ‘how can a girl who wears Jeans or T-shirt be a representative of Pakistan?’

All male teachers told the researcher that they inculcate Islamic values in relation to dressing, as stated above, into students in classrooms, and most students agree to these.

All female teachers subscribed to the above-stated notions. They also attached a very high value to women’s outfits relating them to their morality and sexual correctness, as expressed below:

Pakistani girls should wear Shalwar Kameez. And if she wore trousers it must not intersect with her niswaniat [femininity/women-ness]. Her dressing should also be in line with Islamic injunctions.

They must put on a shawl. If they wear burqa or abaya it must not be for the namesake, like [as observed] their eyes throw coquettish/ flirtatious looks [towards men] but otherwise they are veiled; every contour of their body is dancing provocatively … though they are ostensibly wrapped in an all-encompassing robe.

We also sought teachers’ perspectives about gender representation in textbooks inquiring if in their opinion both women and men had been given nearly equal space in textbooks. To this, I found quite a mixed response. A female teacher first held that it was balanced ‘keeping in view their [women’s] contribution’ (TA). Then she contradicted her own statement stating that she had not seen any ‘encouragement in this regard in the curriculum’ (ibid.). Similarly, two female teachers TB and TK and one male teacher TL said that women had been underrepresented in textbooks. Two female teachers TC and TH contended that the situation was really bad earlier, but after the promulgation of the new educational policy (2017), it had improved. Two male teachers TE and TI, and a male teacher TF were of the opinion that both genders were equally represented.

Interestingly, some teachers, including two women (TH and TB), justified women’s underrepresentation in the name of Islam: ‘Allah (God) has accorded superiority to man and He has correctly done so’ (TB).

In spite of the awareness among teachers about women’s underrepresentation in textbooks, no efforts were made to address/redress this situation in the classroom. The teachers informed the researcher about this when probed.

In summary, most teachers used the school classrooms to reinforce textbook promoted gendered values on women. Foucault (Citation1977, 97) suggests that we should inquire ‘how things work at the level of on-going subjugation … which subject our bodies, govern our gestures, [and] dictate our behaviours etc’. Thus, the teachers used their positions in power to reproduce gender stereotypes. The study found them overly concerned about women’s outfits. They spoke of these in relation to their morality and sexual rectitude. Similarly, they emphasised the importance of religion and family traditions for regulating girl students’ conducts in schools. In the following section, the data collected from the students is presented.

Gender in students’ perspectives

The students’ perspectives on gender were collected using two data tools, namely focus group interviews with 56 contributors (29 girls and 29 boys), and participatory tools with 224 participants (209 girls and 215 boys), as discussed in the methodology section.

Replying to a focus-group interview question as to how a true Pakistani girl should be like, most boy-participants’ conversation centred on what they think women should wear to look decent and respectable. This rather appeared to be a defining inclusion/exclusion criterion for a woman to be a true Pakistani. Other notions included haya (coyness), Sharam (modesty) and Izzat (chastity/probity). Twenty-four (83%) boys maintained that women must be fully covered including the face. Most of them were of the opinion that this would not only make them good Muslims but also good Pakistanis. Three boys explicitly advocated the idea of male guardianship and insisted if women were not fully covered (which is like, as they said, wearing improper clothes), they were highly likely to spread immorality in the society. Selected interview extracts are presented below.

She should put on a niqab [face-cover] on her face, abstain from making friends with boys and must not go out unless accompanied by parents.

She must not dress provocatively.

Girls should not become a vehicle to spread immorality by being improperly dressed up.

A girl is a thing of a home, so she must stay indoors, covered in proper clothes.

Boys’ participatory tools data further reinforced the ideas they had expressed in interviews, discussed above. Of the two-hundred-fifteen boy-participants, ninety-seven (45%) drew the image of a girl with a veil to represent Pakistan or Pakistan’s ‘us’. In addition, fifty-eight (27%) students assigned the labels of ‘chastity’ and ‘practicing Muslims’ to the veiled image of an ‘ideal’ Pakistani girl. Another important aspect that received very high attention was that of obedience, as ninety boys (41%) assigned this character to the image of an ideal Pakistani female. It suggested female obedience to all family patriarchs included father, brother or husband. To one hundred and fifteen boys (53%), domestic management (cooking, cleaning and raising children) was strictly a female domain (see ). However, the figures given herein (ninety or 41% and one hundred and fifteen or 53%) do not suggest that the rest of the students do not consider ‘obedience’ as a desirable trait in women. They, on the other hand, assigned other traits of similar social values (e.g. chastity, veiling, practicing Muslim) that supported female obedience to male patriarchs.

Girl students’ focus group responses, however, signalled some level of resistance to certain ideas expressed by the teachers and male students, presented above. Of the twenty-nine girl-participants, fifteen (52%) spoke strongly in favour of Abaya, and the rest fourteen (48%) argued that Abaya was not necessary. However, they agreed that Pakistani girls should ideally cover their heads and wear either a shawl or dupatta. Interestingly, none of the participants were found in favour of face-covering/veiling. To a vast majority of them (80%), such characteristics as adherence to Islamic sharia and being confident, educated, hardworking, and competitive were important to become good Pakistanis. Selected excerpts from girl-participants’ conversation given below show how Muslimness and Pakistaniness intensely conflate, making it complicated to tell one from the other:

We must cover our heads as Pakistani; we must maintain our Islamic identity.

Purdah is a Muslim woman’s Jihad. We must cover our heads.

We must wear Abaya.

In Islam, it is imperative for women to observe Purdah, but at the same time it supports us to work in the field, not just rest at home.

At home, we get to learn that boys should be given preference in all matters. When a girl is born, the mother faces taunts and scoffs from relatives.

In our society women are divorced if they produce female babies.

People are afraid of girls’ destinies.

In sum, instructed mainly on teacher-mediated textbook discourses, the findings from the students’ data (both male and female) suggest that Pakistani women’s dressing/clothes type are of utmost importance to them. They perceive these outfits as significant makers of Pakistaniness and Muslimness. However, on issues like women’s representation in the textbooks, unlike boys and most male teachers, a dominant majority of girl-participants and some female teachers strongly criticised Pakistan’s education managers for underrepresenting women, thus displaying agency (see Foucault Citation1988). The girl-participants even expressed strong resentment against the discriminatory social practices of according preferential treatment to boys over girls at home. Interestingly, a few of them criticised Islam arguing that Islam accords supremacy to men over women. However, the use of Islam as a technology of power (Foucault Citation1988) served in a way that the resistance emerged from within their own ranks as some girls opposed the idea of criticising Islam and justified their underrepresentation on Islamic grounds.

Discussion

This study explored Pakistan’s national curriculum textbooks and the role of teachers in teaching these textbooks to students in public-schools for shaping a particular female identity of Pakistani women. It problematised both the textbooks and the teachers as two significant technologies of power (Foucault Citation1988). Similarly, it analysed the role of the school as a structure where the interplay of both these technologies took place to make individuals into subjects. The study highlighted the social and institutional embeddedness of gender constructions and showed how Pakistani high school textbooks, teachers, and students reproduced gendered stereotypes about Pakistani women. Similarly, it showed how most textbooks are authored by men, and women rarely appear in images. The study also confirmed that the textbooks mandated under National Education Policy 2017 feature similar gender-biased content as those constructed under previous education policies. In the following sections, it analyses the social implications of the gendered construction of Pakistani women through textbooks and social practices in schools. It explores how this erects boundaries within the Pakistani society at three levels, namely man vs. women; within the ranks of Muslim women; and Muslim women vs. non-Muslim women. The study also examines how the prescription of a particular dress-code for the Pakistani female stands contrary to the rudimentary principles of parliamentary democracy of which Pakistan is a claimant.

By representing a Pakistani woman mainly in domestic performative roles and prescribing particular dressing for her, the textbooks erect gendered boundaries between her and Pakistani men. Therefore, these roles as soldiers, religious leaders, scientists, police, judges and national players appear ‘naturally’ to belong to Pakistani men. Similarly, an emphasis on a particular dressing can cause potential social issues for those women who refuse to conform. These representations of Pakistani women can similarly encourage to perceive her as men’s ‘other’ in certain sections of the Pakistani society, as reflected in the teachers’ and students’ perspectives. Nash (Citation2000, 655) argues that ‘[g]ender does not exist outside its “doing” but its performance is also a reiteration of previous “doings” that become naturalised as gender norms’. Aside from the active participation of women of a particular social class, during the Pakistan movement, and similarly in the post-independence period,Footnote1 the above-mentioned gender ‘doings’ are deeply ingrained in the social structure of Pakistani society. Authored in the nineteenth century, Baheshti Zewar (Heavenly Ornaments), by Thanvi (Citation1999), still makes an integral part of brides’ dowry in many parts of Pakistan. Arguably, one of the most influential works of its time, the book contains an advice manual on almost every aspect of a Muslim woman’s life for her ‘moral guidance’ and ‘character-building’. Being an influential religious ideologue and a staunch supporter of the Pakistan Movement, the influence of his work on the discourses of the textbooks, analysed herein, might well not be completely overruled.

The textbook representation of an ideal Pakistani woman in a shalwar kameez and dupatta and an emphasis on these create boundaries within Pakistani Muslim women and Muslim versus non-Muslim Pakistani women. Contemporarily, a headcover/dupatta is mostly associated with Muslim Pakistan women and is not an inseparable part of non-Muslim Pakistani women. The presentation of this dress in relation to Pakistan and its Islamic identity, thus, excludes the non-Muslim women from Pakistan’s national belonging. Equally, it also excludes those Muslim Pakistani women who are Muslims but are not interested in wearing Shalwar Kameez and Dupatta. Butler (Citation1989, 603), maintains that ‘body is directly involved in a political field; [and] power relations have an immediate hold upon it’. In Pakistan, the regularisation of women’s conduct was done to reinforce the ‘claim to nationhood and to political destiny distinct from that of its predominantly Hindu neighbour, India’ (Mullally Citation2005, 344). Though it is rooted in the genealogy of Pakistan, an overemphasis on it took roots during General Zia’s dictatorial rule as part of his Islamic drive to consolidate power (see Jeffery and Basu Citation1998; Saigol Citation2005). Hence, the institutionalised gendered crafting of women through the textbook generated ‘games of truth’ (Foucault Citation1987, 121) and the systematic dissemination of these ideas through social practices in public schools cannot be isolated from the overall power scheme.

Pakistan is a nation-state that proclaims a parliamentary democracy to be its governing system (see The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 1973 (Citation2012)). In principle, a nation-state is territorially limited (Anderson Citation1983) and believes in the equal rights of its citizens, irrespective of gender, creed, colour and faith. Fostering a particular dress-code for the female is a typical religious valueFootnote2 that stands contrary to the elementary principles of democracy. The emphasis on it, as observed, can encourage moral policing from the state, society, the religious right, and the family, allowing the above-referred structures to subject the Pakistani female to their perceived ‘moral’ standards. These structures jointly reinforce the idea that ‘in order to belong, to be seen as part of an Islamic-Pakistani-community. … women must dress in a certain manner and conform to cultural, social, sexual norms that permeate Pakistani society’ (Rouse Citation1998, 58). In Foucauldian terms, a prescriptive dress code can perform ‘the administrative functions of management, the policing functions of surveillance, the economic functions of control and checking, [and] the religious functions of encouraging obedience and work’ (Foucault Citation1977, 173–174). Similarly, Pakistani women’s invisibility from the textbook pages is an official refusal to acknowledge her status as an equal right bearing citizen of Pakistan. Also, the observed female stereotyping in relation to women’s outfits and the projection of gendered social roles through state-sanctioned education can disempower them as a social category with immense political and economic implications. This can also consolidate the existing exclusionary traditional mindset, as reflected in both the teachers’ and schoolchildren’s thinking patterns.

Conclusion

This study highlights Pakistani women’s disproportionate underrepresentation in the national curriculum textbooks and their use as strong ‘technologies of power’ (Foucault Citation1988) to institute her identity through gendered social roles. To subject a Pakistani women’s body and regulate her conduct, they prescribe strict dress-codes. Similarly, to reinforce particular gender stereotypes meta-narratives of Islam are also employed. These ideologies are imparted to the students in the tightly structured environment of the school under the teachers’ supervision. The study also identified the teachers as ‘vehicles of power’ (Foucault Citation1980, 98) that further the national scheme of consolidating patriarchal ideologies. All these ‘technologies of power’ (Foucault Citation1988) constitute a robust ‘regime of truth’ (Foucault Citation1980) and the students negotiate their identities functioning within these constraints. Surrounded by these ‘officially’ approved structures, the majority of schoolchildren, except some girl-students on one particular aspect, strongly identify with the gendered notions about women. Overall, this situation highlights the power of public-school education and the embeddedness of Pakistan’s national identity which is being shaped as much by meta Islamic discourses as the patriarchal values of Pakistani society. Similarly, it shows how Pakistani women’s interests are subordinated to those of Pakistani men, maintaining existing patriarchal power relations. The study highlights the challenges involved in the provision of holistic inclusive education in an ‘ideological state’. It also underscores how an education system assumedly promising equity and inclusiveness can be exclusionary, encouraging a 50% population of the country to make homemaking their life-long goal. Similarly, the study highlights the social implications of such an approach which include constituting profound divisions within its citizenry on multiple levels and fostering self-righteousness and ethnocentric attitudes towards women. This also has the potential for exclusion and disempowerment of Pakistani women as a social group which will have consequences for both Pakistan and global sustainable development goals (SDGs), 2030, inter alia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

M. Habib Qazi

M. Habib Qazi holds a Ph.D from the University of Leicester, UK and is a Fellow of the HEA, UK. His research interests include critical discourse analysis, discourse analysis and public education with a focus on the national curriculum, national identity construction, power discourses, faith, culture and gender. Habib has published in several prestigious peer-reviewed journals.

Choudhary Zahid Javid

Choudhary Zahid Javid is currently a Professor of Applied Linguistics in the Department of Foreign Languages, Taif University Saudi Arabia (TURSP 2020/133). His research interests include curriculum development, material development, ESP, CALL, ELT. He has authored two ESP textbooks and more than 40 research articles.

Notes

1 This includes Miss Fatima Jinnah, Begum Raana Liaquat Ali Khan, Begum Fida Hussain, Begum Shaista Ikram Ullah and Begum Jahan Ara Shahnawaz- the last two became the members of Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly in 1948. Benazir Bhutto was elected Pakistan’s prime minister twice.

2 ‘O Prophet! Tell your wives and your daughters and the women of the believers to draw their cloaks (veils) all over their bodies’ (Quran 33:59).

References

- Agha, N., G. K. Syed, and D. A. Mirani. 2018. “Exploring the Representation of Gender and Identity: Patriarchal and Citizenship Perspectives from the Primary Level Sindhi Textbooks in Pakistan.” Women's Studies International Forum 66: 17–24.

- Anderson, B. 1983. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Apple, M. W. 2004. Ideology and Curriculum. New York: Routledge.

- BERA. 2011. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. http://www.bbk.ac.uk/sshp/research/sshp-ethics-committee-and-procedures/BERA-Ethical-Guidelines-2011.pdf.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Brunell, L., and E. Burkett. 2019. Feminism. https://www.britannica.com/topic/feminism#ref216011.

- Butler, J. 1989. “Foucault and the Paradox of Bodily Inscriptions.” The Journal of Philosophy 86 (11): 601–607.

- Butler, J. 1999. Gender Trouble. London: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 2006. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” In The Routledge Falmer Reader in Gender and Education, edited by M. Arnot, and M. Mac Ghaill, 61–71. New York: Routledge.

- Chege, F. 2006. “Teachers Gendered Identities, Pedagogy and HIV/AIDS Education in African Settings Within the ESAR.” Journal of Education 38 (1): 25–44.

- The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 1973. 2012. http://www.na.gov.pk/uploads/documents/1333523681_951.pdf.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Foucault, M. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. New York: Pantheon.

- Foucault, M. 1987. The Use of Pleasure. The History of Sexuality. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Foucault, M. 1988. “Technologies of the Self.” In Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault, edited by L. Martin, H. Gutman, and P. Hutton, 16–49. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press.

- Foucault, M. 1993. “About the Beginning of the Hermeneutics of the Self: Two Lectures at Dartmouth.” Political Theory 21 (2): 198–227.

- Given, L. M., ed. 2008. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. London: Sage.

- Jabeen, S., Chaudhary, and Omar, S. 2014. “Gender Discrimination in Curriculum: A Reflection from Punjab Textbook Board.” Bulletin of Education and Research 36 (1): 55–77.

- Jeffery, P., and A. Basu. 1998. Appropriating Gender: Women's Activism and Politicized Religion in South Asia. New York: Routledge.

- Jenks, C. 2005. Childhood. London: Routledge.

- Mayer, T. 2000. “Gender Ironies of Nationalism.” In Gender- Ironies of Nationalism: Sexing the Nation, edited by M. Tamer, 1–24. London: Routledge.

- Mullally, S. 2005. “‘As Nearly as May Be’: Debating Women's Human Rights in Pakistan.” Social and Legal Studies 14 (3): 341–358.

- Nash, C. 2000. “Performativity in Practice: Some Recent Work in Cultural Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 24 (4): 653–664.

- Notshulwana, R., and N. D. Lange. 2019. “‘I’m me and that is Enough’: Reconfiguring the Family Photo Album to Explore Gender Constructions with Foundation Phase Preservice Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 82: 106–116.

- O’Kane, C. 2001. “Facilitating Children’s Views about Decisions Which Affect them.” In Research with Children Perspectives and Practices, edited by P. Christensen, and A. James, 136–159. London: Routledge.

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 2020. Population Census | Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. www.pbs.gov.pk.

- Punch, S. 2002. “Research with Children: The Same or Different from Research with Adults?” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 9 (3): 321–341.

- Qazi, M. H. 2020. “National Identity in a Postcolonial Society: A Foucauldian Discourse Analysis of Pakistan’s National Curriculum Textbooks and their Social Practices in Schools for Shaping Students’ National Belonging.” Doctoral Dissertation. University of Leicester.

- Qazi, M. H., and S. Shah. 2019. “Discursive Construction of Pakistan’s National Identity Through Curriculum Textbook Discourses in a Pakistani School in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates.” British Educational Research Journal 45 (2): 275–297.

- Rouse, S. 1998. “The Outsider(s) Within: Sovereignty and Citizenship in Pakistan.” In Appropriating Gender: Women's Activism and Politicised Religion in South Asia, edited by P. Jeffery and A. Basu, 53–70. New York: Routledge.

- Saigol, R. 2005. “Enemies Within and Enemies Without: The Besieged Self in Pakistani Textbooks.” Futures 37 (9): 1005–1035.

- Thanvi, A. A. 1999. Heavenly Ornaments: Baheshti Zewar. Karachi: Zam Zam Publishers.

- Ullah, H., and C. Skelton. 2013. “Gender Representation in the Public Sector Schools Textbooks of Pakistan.” Educational Studies 39 (2): 183–194.

- UNESCO. 2018. https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-and-gender-equality.

- Weedon, C. 1993. Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory. London: Blackwell.