ABSTRACT

A growing movement towards inclusive education worldwide means more children with autism are being educated in mainstream classrooms. However, integration does not equate to inclusion, and peer stigmatisation of autism is commonplace. This systematic review explores the merit of school-based peer education interventions targeting the stigmatisation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Relevant records published from 1994 were identified through systematic searches of five electronic databases: EBSCO, Medline, PsychInfo, PsychArticles and ERIC. Thirty-one documents pertaining to 27 studies met the pre-specified eligibility criteria and were included for data-extraction. A narrative synthesis highlighted significant flaws in the available literature, most notably poor methodological quality and a narrow research focus with regards to age, the gender of target child and implementation methods. Nevertheless, this study reports on evidence tentatively supporting the efficacy of ASD de-stigmatisation interventions when targeting ignorance and prejudice. Although no one approach can be determined as most effective, manualised programmes combining different types of information about ASD and delivered using various mediums seem to hold the most promise.

Introduction

The publication of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Salamanca Statement represents a clear shift away from the acceptance of segregated education. This influential document has made inclusive education central to human rights, and a policy objective in most countries (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation Citation1994). Since there has been an increasing worldwide social impetus to educate those with disability/disabilities alongside their peers without disabilities in mainstream education settings. Yet, inclusion policy has to date focused predominantly on the promotion and facilitation of integration (i.e. a physical presence in mainstream education settings).

As an example, in response to the Salamanca Statement, the Irish government passed the 1998 Education Act (Government of Ireland Citation1998) which obliged schools to cater for the educational needs of all children in Ireland. Later, the Education for Persons with Special Needs Act (Government of Ireland Citation2004) made several specific provisions for the education of Irish children with disability/disabilities including the right to be educated in a mainstream school. However, full inclusion remains to be realised. A withdrawal model of additional support (or integrated segregation), involving the removal of children with disability/disabilities from their regular education classroom for one-to-one/small group work is commonplace in Ireland (Ware et al. Citation2011). Similarly, UK research suggests that only 32% of children with disability/disabilities fully attend their regular mainstream class (Croll Citation2001). In addition, and counter to the inclusion movement, the use of segregated classrooms (or ‘units’) attached to mainstream schools is increasing in Ireland. Student enrolment in these settings has almost doubled from 2004 to 2018 (Department of Education and Skills Citation2019). Therefore, despite a legislative shift towards inclusion, educational practices would appear to be more in line with integration.

It is argued that, in addition to a physical presence, full inclusion encompasses acceptance (by both teachers and peers), participation (quality experiences of the social, emotional and academic aspects of education within the school community), achievement (academic progress and improvements in social and emotional skills), and prevention of ‘integrated segregation’ (e.g. the use of withdrawal classes; Booth and Ainscow Citation1998). While children with disability/disabilities have increased opportunity for physical integration into mainstream schools, there is no certainty of experience of this broader conceptualisation of inclusion.

This is particularly true of individuals with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD),Footnote1 the characteristics of which can impede social inclusion in general education settings (Humphrey and Symes Citation2011). Autistic individuals universally experience difficulties with social communication and in social development, and often display ritualistic and stereotypical behaviours, resistance to change, and sensory sensitivities (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013). These social, communication, and behavioural difficulties place this population at an increased risk for social exclusion compared to children with none and/or other disabilities (Campbell et al. Citation2017; Hebron, Humphrey, and Oldfield Citation2015; Humphrey and Symes Citation2010, Citation2011; J. Schroeder et al. Citation2014a).

Research suggests a high prevalence of stigmatisation of children with ASD by their peers in integrated mainstream school settings. Stigma encompasses three elements: (1) ignorance (inaccurate knowledge); (2) prejudice (negative attitudes); and (3) discrimination (negative behaviours or behavioural intent; Thornicroft et al. Citation2007). Although peer awareness of autism is reportedly growing with increasing numbers of autistic children being educated in mainstream schools, studies suggest this awareness is basic (e.g. self- reporting that they know what autism is, or what the term autism means; Campbell and Barger Citation2011; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Dillenburger et al. Citation2017). Although aware of autism, peers continue to have inaccurate knowledge of autism: being unable to accurately define what autism means (Campbell and Barger Citation2011; Campbell et al. Citation2004, Citation2005; Dillenburger et al. Citation2017; Magiati, Dockrell, and Logotheti Citation2002); and are ignorant of autism as a disability associated with social communicative and behavioural difficulties (Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell Citation2017).

Misinterpretation and misattribution, stemming from this ignorance, of behavioural manifestations of autism can result in negative attitudes towards autistic peers and discrimination in the form of social exclusion. Indeed, compared with their typically developing peers, research suggests that autistic students have reduced social interactions, spend less time in cooperative activities and more time in solitary activities, and have significantly fewer high-quality friendships (Bauminger et al. Citation2008; Humphrey and Symes Citation2011; Kasari et al. Citation2011; J. J. Wainscot et al. Citation2008b). Reflecting this, students with ASD in mainstream classes have been found to self-report fewer friendships, lower levels of social support, high rates of loneliness and low social acceptance (Bauminger et al. Citation2008; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Chamberlain, Kasari, and Rotheram-Fuller Citation2007; Connor Citation2000; Humphrey and Symes Citation2011; Osler and Osler Citation2002; Symes and Humphrey Citation2010).

Of concern is that low social acceptance increases the risk of victimisation in the neurotypical population (Godleski et al. Citation2015; Veenstra et al. Citation2007, Citation2010); and research suggests that for children with autism there is a four-fold likelihood of experiencing bullying (Campbell et al. Citation2017; J. Wainscot et al. Citation2008a), and an increased likelihood relative to other disability groups (e.g. dyslexia; Rowley et al. Citation2012; Symes and Humphrey Citation2010). The consequences of bullying for the autistic population are serious, with research suggesting it is associated with negative academic, social, and psychological outcomes (J. H. Schroeder et al. Citation2014b).

While the use of school-based interventions targeting the social communication difficulties of autism has had undoubted benefits for these children (see Sutton et al. Citation2019 for a systematic review of existing literature), their effectiveness will always be limited given inevitable residual socialisation difficulties. Despite some social skill improvement within the autistic individual, social interaction requires the acceptance of another. Thus, the degree to which children with autism are stigmatised by their peers within mainstream school settings is cause for concern and has led many to suggest the focus of intervention should be widened beyond the individual with ASD to include their peers and the larger school system (Sutton et al. Citation2019).

In response, the development and evaluation of school-based interventions aimed at reducing the stigmatisation of children with ASD have gathered momentum. Peer-directed educational approaches generally include the provision of all, or a combination of descriptive information designed to promote likability by highlighting similarities between a student with ASD and the peer group; explanatory information to provide attribution for deviant behaviour; directive information which provides suggested behaviours to better include autistic peers; and ASD facts providing information about the characteristics of ASD. A review of the theory underlying each of these forms of information has been outlined in previously published works (see for example Ranson and Byrne Citation2014). Thus, these educational interventions are intended to target stigma through the provision of accurate, age-appropriate and relevant information about ASD, as well as explicit strategies to better understand and interact with individuals with ASD (Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell Citation2017).

Research aims

This systematic review of the available literature aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the merit of school-based educational approaches to de-stigmatisation of ASD through the exploration of the following questions:

How are experimental evaluations of peer-directed ASD de-stigmatisation interventions applied to school settings? Specifically, what interventions are used, how are they implemented, and what research design is used to evaluate their merit?

What is the overall quality of identified studies that have both included and evaluated an ASD de-stigmatisation element to intervention as measured by published quality rating scales?

Do the results of identified studies support the use of peer education to target the stigma experienced by schoolchildren with ASD?

Methods

We performed a systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. The methods were predetermined and specified in a protocol submitted to the PROSPERO database of systematic reviews in October 2019.

Search strategy

Relevant records were identified through systematic searches of five electronic databases: Academic Search Complete (EBSCO), Medline, and the PsychInfo, PsychArticles and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) databases through the Proquest platform. With input from a social sciences librarian, the PICOS framework was used to help structure and identify relevant terms for searches. In all databases, the following search term combinations were entered in the subject terms (SU) field: (Autis* OR pervasive OR Asperger*) AND su(stigma* OR accept* OR attribution* OR attitude* OR prejud* OR knowledge OR ignoran* OR discriminat* OR aware* OR initiation* OR contact* OR misperce* OR perception* OR belief* OR bully* OR victim* OR friend* OR intent* OR view* OR judgement*) AND su(intervention* OR programme* OR educat* OR train* OR inform*) AND su(school* OR preschool* OR mainstream* OR primary OR secondary OR kindergarten OR elementary OR crèche OR Montessori OR early year* OR classroom*) AND su(peer* OR child* OR adolescen* OR student* OR pupil*). No ‘language of publication’ or ‘publication type’ limiters were applied. In line with the study aims, when possible, database searches were limited by population (human), age (to include those individuals 18 years or younger) and limited to documents published from 1994 (following the publication of the UNESCO Salamanca Statement).

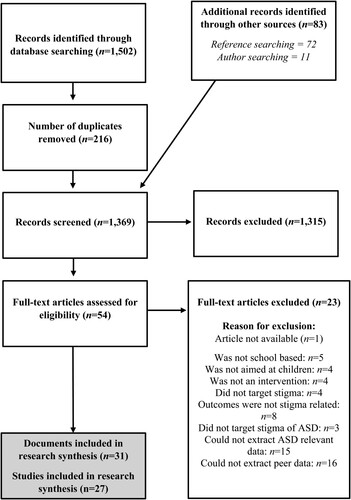

After removing duplicates, all retrieved documents were screened independently for relevance against the eligibility criteria by ?.?(first author) and ?.? (third author), first by title and abstract and then when indicated by full-text. There was substantial agreement (98%; Cohen’s κ = .687) between screeners for title and abstract, and perfect agreement (100%; Cohen’s κ = 1) for full-text screening. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and shared consensus. To identify additional relevant publications, electronic searches were supplemented by the manual search of reference lists of included studies and all their authors. This was an iterative process until no more eligible documents were sourced. This method of document identification is depicted by the PRISMA flow diagram in . Searches of databases, reference-lists and author publications occurred between October 2019 and January 2020 and were conducted by SM. Covidence software was used to manage references and record progress (Covidence systematic review software).

Eligibility criteria

To be included in this review, studies were required to meet a set of pre-determined inclusion criteria. Requirements for inclusion were: (1) population – must target peer stigmatisation of children with ASD. Given the search period (1994 onwards), acceptable population descriptive terms included autism, autistic disorder, high functioning autism, low functioning autism, Asperger’s syndrome, atypical autism and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, to reflect the varying diagnostic labels used over time (American Psychiatric Association Citation1980, Citation1994, Citation2013); (2) intervention – must describe the provision of stigma related information to peers (to include one/a combination of descriptive, explanatory, directive, and/or ASD facts); (3) comparison and study – explores, using any comparison (including subjective reports) and using any methodology, the impact of this intervention on peer stigma; (4) outcome – reports on the impact of intervention on stigma variables, including knowledge, attitudes and/or social behaviours (intended or actual); and (5) delivers the intervention through a school/classroom catering for children under 18 years of age (including pre-schools, primary and secondary schools).

Additionally, studies were excluded if: (1) data relating to the impact on peers could not be isolated and extracted (i.e. the outcomes measured change in the ASD population only); (2) data relating to the stigma of individual(s) with ASD specifically could not be isolated and extracted if the intervention targets stigma of disability/difference more generally; (3) the intervention targeted stigma in a different population other than peers (e.g. teachers); and (4) interventions were delivered through third level institutions. When possible, authors of included studies were contacted to obtain information that would support a study’s inclusion e.g. to source autism specific data from a study which published data on a general disability population.

Assessment of methodological quality

Relevant outcomes (for this review) for each of the included studies were rated for methodological quality using published rating scales. Outcomes assessed using qualitative methodologies were judged for rigour using the NICE quality appraisal checklist for qualitative studies (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Citation2012b). Each study’s methodology was judged to be either of high, low or unclear quality for each of the domains: theoretical approach, study design, data collection, trustworthiness, data analysis, ethics, and overall assessment. For quantitative outcomes, methodological quality was assessed using the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklist for quantitative intervention studies (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Citation2012a). This checklist evaluated each study’s internal and external validity as either high, medium and low risk by appraising: characteristics of the participants, the definition of and allocation to study conditions, outcomes over time, and methods of analyses. This tool provided well-defined instructions on how to rate each criterion and allowed for the systematic evaluation of studies with a range of quantitative experimental designs. Risk of bias was further assessed using the Cochrane recommended tool ‘Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions’ (ROBINS-I; Sterne et al. Citation2016). Using the checklist guidelines, each study assessing a quantitative outcome was appraised for risk of bias in the following domains: confounding, participant selection, classifications of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, selection of reported results, and overall bias. This process of double assessment of quantitative outcomes ensured that each study was assessed consistently, which limited reviewer bias in the assessment of quality.

Data extraction

When a study was described by more than one included report, data was extracted from all documents for that study. Records meeting all inclusion criteria were coded to extract data relating to population (e.g. sample size, participant demographics, target ASD child characteristics), key characteristics of intervention (e.g. content, delivery), evaluation design, outcome measures, and results.

Analysis

There was significant methodological and clinical heterogeneity between included studies. A meta-analysis of quantitative data was viewed as inappropriate and a descriptive approach to synthesis was employed. Observed patterns of similarity and difference between study populations, methodologies and results were critically appraised. Studies rated as high methodological quality were analysed to assess the utility of peer targeted ASD de-stigmatisation interventions and to identify factors that are likely to support or hinder effectiveness.

Results

Study identification

depicts a PRISMA flow diagram detailing the results of the literature search. The searches retrieved 1,502 documents, 1,286 following the removal of duplicates, which were screened for title and abstract. A list of excluded documents is available from the first author by request. A total of 47 documents were subject to a full-text screen for eligibility, of which 23 were excluded (reasons for exclusion at this phase are included in ). Supplementary searches of the reference lists and authors of all included studies resulted in the identification of an additional seven studies. A total of 31 identified documents met eligibility criteria describing 27 studies: Campbell et al. (Citation2005) and Campbell et al. (Citation2004) were articles describing the same intervention with the same participants; while the pairings of Ezzamel (Citation2016) and Ezzamel and Bond (Citation2017), Sreckovic (Citation2015) and Sreckovic, Hume, and Able (Citation2017), and Swaim (Citation1998) and Swaim and Morgan (Citation2001) were all combinations of a published thesis and a peer reviewed article.

How are experimental evaluations applied in terms of approach to intervention and research design?

reports on the characteristics of the 27 studies included in the final review, and summarises these key characteristics. Most documents were peer-reviewed journal articles (80.7%), with the remainder published theses. Studies were conducted in the USA (55.6%), the UK (25.9%), Australia (7.4%), Greece (7.4%) and in Israel (3.7%). All studies focused on stigma in ASD specifically, with the exception of Frederickson, Warren, and Turner (Citation2005) which focused on disabilities more generally but ASD data could be isolated and extracted.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies assessing school-based peer targeted ASD stigma interventions.

Table 2. Number of studies (and percentages) reporting the listed characteristics.

Participants

Data on a number of peer participants (non-ASD) was reported in 22 of the included studies. These studies collected data on stigma related outcomes for 3,619 peers of children with ASD (range of participants per study 3-576; M = 164.5, SD = 179.64). From these 22 studies, 16 reported on gender: 1,587 males and 1,388 females. The age of participants was difficult to determine. Mean/average age was reported in 12 of the 27 studies (range 6.7–15.3; overall M = 11.13, overall SD = 2.3).

The types of school settings in which the intervention was delivered are summarised in . For some studies, school type was not reported but could be deduced from the country paired with reported participant grades and ages (reported in brackets in ). As the type of school could be established for most of the included studies (n = 26), it is likely a more accurate reflection of the age range of participants represented in this review. The number of studies conducted in each school setting is elementary/primary schools (approximate ages 5–11), n = 15; middle schools (approximate age range 11–14), n = 4; lower secondary schools (approximate age range 11–15), n = 5; high schools (approximate age range 14–18), n=3; upper secondary schools (approximate age range 15–18), n = 1; non-mainstream schools, n = 1; and unknown, n = 1.

Participant inclusion criteria for the 17 studies which reported this is summarised in . Studies assessing stigma towards familiar autistic children regularly recruited those with desirable characteristics such as: likely to engage and comply with the intervention e.g. interest in group work, regular attendance and good social skills (Collet-Klingenburg, Neitzel, and LaBerge Citation2012; Cook Citation2017; Ezzamel Citation2016; Ezzamel and Bond Citation2017; Gardner et al. Citation2014; Houston Citation1998; Hughes et al. Citation2013; Owen-DeSchryver et al. Citation2008; Sreckovic Citation2015; Sreckovic, Hume, and Able Citation2017); previously demonstrated interactions with the target child (Collet-Klingenburg, Neitzel, and LaBerge Citation2012); and judged likely to engage with the target child (Gardner et al. Citation2014; Hughes et al. Citation2013; Sreckovic Citation2015; Sreckovic, Hume, and Able Citation2017). Studies often required participants to be in the same class as the target child (Collet-Klingenburg, Neitzel, and LaBerge Citation2012; Cook Citation2017; Ezzamel Citation2016; Ezzamel and Bond Citation2017; Hughes et al. Citation2013).

In contrast, participants in studies assessing stigma without a target child or towards unfamiliar peers with ASD were often those shown to be unknowing about autism (either from never having heard of autism, or an inability to provide a reasonable description/definition) and/or in a school classroom that did not have any autistic children (Campbell et al. Citation2004, Citation2005; Fleva Citation2014, Citation2015; Morton and Campbell Citation2008; Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell Citation2017; Silton and Fogel Citation2012; Swaim Citation1998; Swaim and Morgan Citation2001). In one case those classes with higher numbers of children with ASD were allocated to control conditions (Staniland and Byrne Citation2013).

Target children with ASD

Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell (Citation2017) assessed change in knowledge of autism, and was the only study that did not include at least one target child with ASD as part of the intervention delivery and/or assessment. There were 52 familiar target students from 16 studies (59.3%; per study M = 3.31, SD = 3.67). Gender information was available for 44: 38 males and 6 females. Information relating to age was reported in various formats (see for details per study), with an estimated mean age of 11.56 (range 5–18) derived from available information. A total of 11 unfamiliar target children were used across nine studies (33.3% of the sample). All were hypothetical children described using vignettes. The gender was unreported for two (Mavropoulou and Sideridis Citation2014; Silton and Fogel Citation2012). Most were male (n = 8; Campbell Citation2007; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Campbell et al. Citation2004, Citation2005; Fleva Citation2014, Citation2015; Morton and Campbell Citation2008; Silton and Fogel Citation2012; Swaim Citation1998; Swaim and Morgan Citation2001), and there was one female (Silton and Fogel Citation2012). From the data reported, the mean age of unfamiliar target children was 12.71. Two studies (Ranson and Byrne Citation2014; Staniland and Byrne Citation2013) had participants complete outcome measures with reference to ‘their peers with autism’ so the level of familiarity could not be categorised. Further descriptions of all target ASD children are reported by a study in .

Methods

summarises the methods used in each of the included studies, and provides a summary. Attitudes were assessed in 88.9% of included studies, behavioural intentions in 37%, actual behaviour in a third of all included studies (33.3%), and a measure of knowledge of autism was included in just over a quarter (25.9%). Five studies assessed three outcomes (Campbell Citation2007; Gus Citation2000; Mavropoulou and Sideridis Citation2014; Ranson and Byrne Citation2014; Staniland and Byrne Citation2013), and nine reported data for a single outcome: attitudes (Cook Citation2017; Frederickson, Warren, and Turner Citation2005; Gardner et al. Citation2014; James Citation2011; O’Connor Citation2016; Reiter and Vitani Citation2007); actual behaviour (Houston Citation1998; Owen-DeSchryver et al. Citation2008); and knowledge (Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell Citation2017). Of the remaining 13 studies, six assessed both attitudes and intended behaviour (Campbell et al. Citation2004, Citation2005; Fleva Citation2014, Citation2015; Morton and Campbell Citation2008; Silton and Fogel Citation2012; Swaim Citation1998; Swaim and Morgan Citation2001), six assessed both attitudes and actual behaviour (Collet-Klingenburg, Neitzel, and LaBerge Citation2012; Ezzamel Citation2016; Ezzamel and Bond Citation2017; Hughes et al. Citation2013; Simpson and Bui Citation2016; Sreckovic Citation2015; Sreckovic, Hume, and Able Citation2017; Whitaker et al. Citation1998), and one assessed knowledge and attitudes (Campbell et al. Citation2019).

All but three of the included studies employed a quantitative methodology for at least one outcome of interest (group design, n = 19; and single-subject design, n = 5). Eight studies used a qualitative approach to assess at least one relevant outcome. Within each of these broad methodologies, there was great variability in the approaches taken to evaluate the impact of interventions (all listed in ). In the group designs, a follow-up maintenance assessment was included in seven of the studies, ranging from one-week to 23-weeks.

Reflecting the larger number of quantitative studies included in the current review, standardised pen and paper measures were the most frequently used method of assessment. All were self-report measures. The Shared Activities Questionnaire (Morgan et al. Citation1996) was used in 10 of the included studies as a measure of participants’ behavioural intentions towards a peer with ASD. The Adjective Checklist (Siperstein Citation1980; Siperstein and Bak Citation1977) was the tool favoured to assess attitudes and used in a third of all included studies. The Chedoke-McMaster Attitudes Towards Children with Handicaps (Rosenbaum et al. Citation1986), or a modified version, was an alternative self-report measure of attitude used in three studies.

Four different knowledge of autism questionnaires were used across five studies: a bespoke measure in Campbell (Citation2007) and an adapted version of this tool (developed by Campbell and Barger Citation2011) was used in Campbell and colleagues’ 2019 study; Mavropoulou and Sideridis (Citation2014) used the ‘Adapted Knowledge of Autism Questionnaire’ (Ross and Cuskelly Citation2006); and the bespoke Autism Knowledge Questionnaire, developed and used by Staniland and Byrne (Citation2013), was also used in Ranson and Byrne’s study (Citation2014). Both Gus (Citation2000) and Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell (Citation2017) used qualitative methods to explore the impact of the intervention on knowledge of autism.

Focus groups with participants (Collet-Klingenburg, Neitzel, and LaBerge Citation2012; Ezzamel Citation2016; Ezzamel and Bond Citation2017) and participant interviews (Cook Citation2017; Hughes et al. Citation2013; Simpson and Bui Citation2016; Whitaker et al. Citation1998) were the qualitative methods employed to explore the impact of the intervention on peer attitudes and/or subjective behavioural change towards an autistic peer. Other studies assessing actual behaviour change (rather than behavioural intent; n = 7) used direct observations of participant behaviours as a method of measurement.

Interventions

A summary of the interventions employed by all studies is reported in and summarised in .

Table 3. Intervention characteristics and evaluation results of included studies.

Table 4. Summary of intervention characteristics of included studies.

Within interventions, descriptive information was the most provided information type (81.5%), followed by explanatory (70.4%). Equal numbers of studies (n = 18) provided participants with directive information and ASD facts. The majority included more than one type of information, with 14.8% using only one. Most used three pieces of information in their intervention (28.2%), and just over a quarter used all four types. This information was delivered mostly by researchers (74.1%), with school staff involved 40.7% of the time.

There were eight different approaches to intervention. Vignettes about hypothetical children with ASD were used in just over a quarter of studies (Campbell Citation2007; Campbell et al. Citation2004, Citation2005; Fleva Citation2014, Citation2015; Morton and Campbell Citation2008; Silton and Fogel Citation2012; Swaim Citation1998; Swaim and Morgan Citation2001). These interventions involved participants receiving information about ASD paired with either a PowerPoint of pictures, or a video of actors portraying an autistic child. All explored the effects of providing descriptive, explanatory and ASD specific information on outcomes, with most comparing conditions to explore the unique impact of information type. Silton and Fogel (Citation2012) also assessed the impact of directive information (i.e. all four types of information). These interventions were all single sessions ranging in length from <3 min to 22 min, and exclusively targeted stigmatisation of ASD using peer education.

Two included studies evaluated the impact of bespoke ASD education programmes on stigma related variables (Mavropoulou and Sideridis Citation2014; Owen-DeSchryver et al. Citation2008), while another nine evaluated one of three manualised programmes: ‘Kit for Kids’, ‘Understanding Our Peers’, and ‘Circle of Friends’. The ‘Kit for Kids’ intervention (Organization for Autism Research Citation2012) is a single-session programme consisting of a lesson plan, an educational poster, and peer handouts that provide information using all four information types. Two studies in this review evaluated this programme (Campbell et al. Citation2019; Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell Citation2017), while a further two evaluated the adolescent ‘Understanding Our Peers’ (Staniland and Byrne Citation2013) programme (Ranson and Byrne Citation2014; Staniland and Byrne Citation2013). The latter uses a combination of descriptive, explanatory, and directive information with the provision of ASD facts through direct, video and online content.

‘Circle of Friends’ (Pearpoint, Forest, and Snow Citation1992) was the most evaluated intervention in this review (18.5% of included studies). It is an educational approach that facilitates inclusion through the development of a peer network for an isolated individual. An initial whole class meeting involves providing descriptive and explanatory information about a target child, including a discussion of strengths and challenges. Peers are asked to brainstorm ways of supporting the child in the school environment (directive information). From this meeting, 6–8 volunteers agree to form the target child’s ‘circle’ and meet regularly to problem-solve coping with inappropriate behaviours. Two studies used adapted versions: Frederickson, Warren, and Turner (Citation2005) included ASD descriptive, explanatory and directive information in their whole class meeting along with facts about ASD; and Gus (Citation2000) used a shortened model (only the whole-class meeting) and included all four types of information.

Several interventions described as either Peer Networks (Gardner et al. Citation2014; Sreckovic Citation2015; Sreckovic, Hume, and Able Citation2017) or peer-mediated interventions (with a focus on social behaviours; Collet-Klingenburg, Neitzel, and LaBerge Citation2012; Ezzamel Citation2016; Ezzamel and Bond Citation2017; Houston Citation1998; Hughes et al. Citation2013) employed a similar approach to ‘Circle of Friends’. In these studies, participants were provided with ASD education and/or information on a target autistic child (sometimes as a whole class, and sometimes limited to a small group), and a peer group met frequently to problem-solve barriers to inclusion (through training and/or group discussion). Behavioural change in both the peers and the target child were a focus in these studies. In addition, two peer-mediated interventions aimed at improving the academic attainment in the target child, but which also provided stigma related data exploring the impact of the education session on network peers, were included (Cook Citation2017; Simpson and Bui Citation2016).

Reiter and Vitani (Citation2007) were alone in this review in evaluating a mediation programme aimed at decreasing burnout in the peers of those with ASD. Of note is that material/activities from Carol Gray’s Sixth Sense (2002) programme were used in five studies (Collet-Klingenburg, Neitzel, and LaBerge Citation2012; Houston Citation1998; Mavropoulou and Sideridis Citation2014; Ranson and Byrne Citation2014; Staniland and Byrne Citation2013). Descriptions of interventions for each included study are reported in .

What is the overall quality of identified studies?

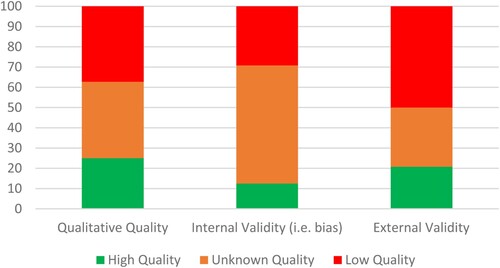

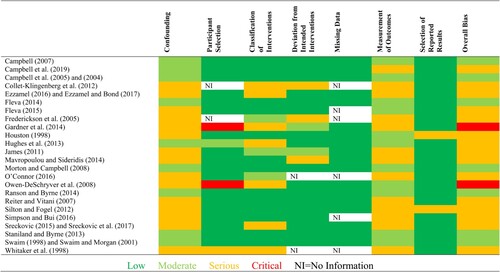

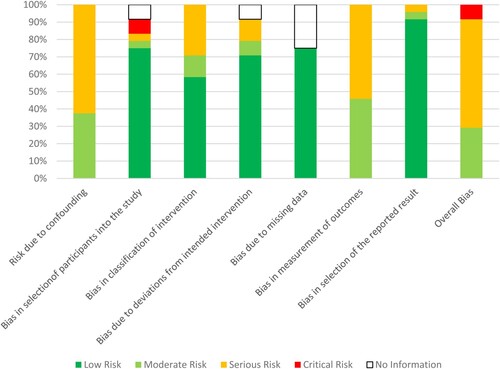

Details of quality appraisals for each study, as judged by each measure, are reported in (NICE quality appraisal checklist – qualitative) and (NICE quality appraisal checklist – quantitative; summarised in ), and and (ROBINS-I).

Figure 2. Quantity of studies rated as being of low, unknown and high quality for the assessment of outcomes of interest using the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Studies (n = 8) and the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklist for Quantitative Intervention Studies (internal and external validity; n = 24).

Figure 3. Quality appraisal of quantitative outcomes of included studies as judged using the ROBINS-I.

Figure 4. Quantity of studies (n = 24) rated as being of low, moderate, serious and critical risk of bias for the assessment of quantitative outcomes of interest using the ROBINS-I risk of bias tool.

Table 5. Quality appraisals of the qualitative outcomes of included studies as judged using the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklist – Qualitative Studies.

Two of the studies reporting qualitative outcomes of interest demonstrated congruity between their theoretical approach, study design, methods of data collection, trustworthiness, ethics, and analysis of the data, although failed to provide a clear statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically in the study (Ezzamel Citation2016; Ezzamel and Bond Citation2017; Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell Citation2017). All other studies were rated as unclear or low in quality, mostly owing to unsystematic data collection and/or analysis procedures, and poor study design (see ).

Regarding quantitative outcomes, across both assessment tools measurement of outcome was identified as a common risk of bias, due (in-part) to the over-reliance on self-report measures and/or unblinded observations of behaviour. Information bias was high for knowledge outcomes, in particular, owing to the use of bespoke measures. Confounding was the greatest source of bias identified by the ROBINS-I (see ). None of the included studies adequately described/reported both randomisation and allocation concealment, and most failed to control for confounders either through study design or data analysis. This was particularly true of baseline confounding (or selection bias), with the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklist also identifying this as an issue. Only five studies reported recruiting from a representative source population. Most selected participants were unrepresentative of the class/school: recruiting based on desirable characteristics that likely bias the outcome away from the null hypotheses. Nine studies sought participants that would make engagement and compliance with the intervention more likely, and four studies recruited based on a proven, or likely, ability to engage in positive social interactions with the target child(ren). This selection bias impacted negatively on the external validity scores as judged by this tool (see ).

Across studies, intervention status was generally well defined and various methods were used to enhance consistency of delivery. A member of the research team was involved in intervention delivery 74.1% of the time, and fidelity checklists and manuals for implementation were frequently used. In addition, most of the studies did not omit important outcome data in their reports, and (from those that adequately reported) data were available for all/almost all participants at the study conclusion.

Overall the most methodologically robust studies were the qualitative study conducted by Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell (Citation2017), the qualitatively informed results from the mixed-method study reported in Ezzamel (Citation2016) and Ezzamel and Bond (Citation2017), and the quantitative studies of Fleva (Citation2014), Swaim (Citation1998), Swaim and Morgan (Citation2001), Byrne and colleagues (Ranson and Byrne Citation2014; Staniland and Byrne Citation2013), and several from Campbell independently or with colleagues (Campbell Citation2007; Campbell et al. Citation2004, Citation2005, Citation2019; Morton and Campbell Citation2008).

Is there support for the use of peer education to target ASD stigma?

To ensure rigour in the interpretation of results, assessment of intervention effects was limited to those studies deemed to have good methodological quality (results for all included studies are reported in and summarised in ). There were 10 studies meeting these criteria, and comprised those that: evaluated single-session vignette interventions with children unfamiliar with ASD (Campbell Citation2007; Campbell et al. Citation2004, Citation2005; Fleva Citation2014; Morton and Campbell Citation2008; Swaim Citation1998; Swaim and Morgan Citation2001); explored the utility of the ‘Kit for Kids’ programme (Campbell et al. Citation2019; Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell Citation2017); and the adolescent ‘Understanding Our Peers’ programme (Ranson and Byrne Citation2014; Staniland and Byrne Citation2013); and qualitatively explored the effects of a peer mediated intervention (Ezzamel Citation2016; Ezzamel and Bond Citation2017). Interventions effects will be summarised for impact on knowledge, attitudes and behaviours.

Knowledge

An evaluation of the single-session ‘Kit for Kids’ programme was found to be more effective than a control condition at increasing fourth- and fifth-grade students’ knowledge of autism, an effect which maintained over a 1-week period (Campbell et al. Citation2019). Similar significant differences between control and experimental conditions were found following both a six-session (Staniland and Byrne Citation2013) and eight-session (Ranson and Byrne Citation2014) ‘Understanding Our Peers’ programme with eighth-graders. These gains were maintained at a 3-month follow-up. In a qualitative evaluation of ‘Kit for Kids’, participants aged 10–15 described only a general awareness of autism as a type of problem, disorder, or disability before the intervention, and post-interviews could recall specific content from the programme materials about autism-related behavioural difficulties and sensory sensitivities (Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell Citation2017). In contrast, Campbell (Citation2007) found that no information condition (descriptive, explanatory, and combined descriptive and explanatory) was significantly better at improving knowledge of ASD over time compared to a non-information control condition (mean participant age 13.07).

Attitudes

Qualitative data from Ezzamel and Bond’s (Citation2017) peer mediation intervention, with children aged 7/8, suggests attitudinal shifts towards a familiar child with ASD as a consequence of receiving a combination of descriptive, explanatory and directive information. Participants reported increased understanding, and recognition of similarities. Regarding vignette evaluations, Swaim and Morgan (1998, Citation2001), Campbell (Citation2007) and Fleva (Citation2014) all reported no significant benefit of pairing explanatory information with descriptive information in self-rated attitudes towards a hypothetical autistic child (all using the Adjective Checklist). Campbell (Citation2007) also found no benefit of providing any type of information (descriptive, explanatory, or both combined) over a control no-information condition. Yet, both the six- (Staniland and Byrne Citation2013) and eight session (Ranson and Byrne Citation2014) ‘Understanding Our Peers’ programmes were found to significantly improve attitudes (also using the Adjective Checklist) of participants in the intervention condition compared to controls, which maintained at 3-month follow-up.

Campbell (Citation2007) also reported that for participants who had never heard of autism before, attitudes in the descriptive condition were significantly worse than control and combined conditions (which did not differ significantly). Yet, Campbell and colleagues (Citation2019) found that the ‘Kit for Kids’ intervention significantly improved the attitudes of novice participants compared to controls and those who had previously heard of autism (as measured by the Children’s Attitudes Toward Children with Handicaps-Modified tool). Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell (Citation2017) qualitative exploration of the same programme on the attitudes of participants’ (who did not have a child with ASD as a classmate) towards a hypothetical ASD peer had mixed findings. While some students described the peer as incapable of doing things, others expressed understanding.

A part-replication of Swaim and Morgan’s (1998, Citation2001) study with increased statistical power, reported by Campbell et al. (Citation2004, Citation2005), found that younger participants (those in the third- and fourth-grade) in the combined explanatory and descriptive condition showed improved attitudes towards ASD compared to a descriptive only condition. No such effect was observed for older fifth-grade participants. Morton and Campbell (Citation2008) further found that fifth-graders’ attitudes are significantly improved when the educational intervention is delivered by a teacher as opposed to a parent of a hypothetical child with ASD. Fleva (Citation2014; participants aged 10–16) later found that attitudes are improved when information is delivered by a friend as opposed to a teacher.

Behaviours

Evaluations of the adolescent ‘Understanding Our Peers’ suggest the six-week (Staniland and Byrne Citation2013) and eight-week (Ranson and Byrne Citation2014) programmes were ineffective at improving behavioural intentions towards a hypothetical peer over time compared to controls. Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell (Citation2017) qualitative evaluation of the ‘Kit for Kids’ programme similarly found that only a few participants could describe action they could take to modify their own behaviours to improve the integration of students with ASD.

Evaluating vignettes, Swaim and Morgan (1998, Citation2001), Campbell (Citation2007) and Fleva (Citation2014) reported no significant added benefit of explanatory information when paired with descriptive information in self-rated behavioural intentions using the Shared Activities Questionnaire (and in the case of Campbell a control condition). A part-replication of Swaim and Morgan’s (1998, Citation2001) reported by Campbell et al. (Citation2004, Citation2005), found participants in the combined explanatory and descriptive condition showed improved behavioural intentions towards a hypothetical child with ASD compared to a descriptive only condition (with no control comparison). Results suggested females were influenced more than males by combined information (particularly for academic intentions; Campbell et al. Citation2004), as were socially rejected children when compared to other sociometric groups (particularly for social intentions; Campbell et al. Citation2005).

When in receipt of combined information, Morton and Campbell (Citation2008) found significantly improved behavioural intentions for fifth-graders when the information was delivered by an extra-familial source (i.e. a teacher or ‘doctor’ as opposed to parent of a child with ASD), and for fourth-graders when provided by a mother of a hypothetical child. Although Fleva (Citation2014) found that academic intentions are improved when the teacher delivers a combined educational message as opposed to descriptive only, across both conditions behavioural intentions were higher when the message was delivered by a friend of the hypothetical child as opposed to a teacher.

With regards to actual behaviour change, Ezzamel and Bond’s (Citation2017) focus group evaluation of a peer-mediated intervention reported that although one friendship formed from intervention, participants largely reported difficulty with engaging with their ASD peer. One participant appeared to socially reject the target child, reporting they lacked the confidence/competence to engage. Participants in this study expressed a need for more explicit instruction and information on how to cope with challenging behaviours (i.e. more directive information). A request for additional information to support connection was also made by participants in Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell (Citation2017) qualitative study.

Table 6. Quality appraisals of quantitative outcomes of included studies as judged using the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklist – Quantitative Studies.

Discussion

This review identified and summarised 27 studies that delivered a peer-directed educational intervention (including all or a combination of descriptive, explanatory, directive or factual information about autism) in a school-setting, and evaluated the impact of this intervention on at least one stigma-related outcome (knowledge of ASD, attitudes towards autistic peers, and actual/intended behaviours towards these peers). Summaries of these studies highlighted a variety in approach to intervention, including peer-mediated, peer network, vignettes, bespoke educational lessons, mediation, and manualised programmes. Methodologies also varied, with a mix of qualitative, single-subject, and group designs represented in included studies. Given the heterogeneity in interventions and methodologies across (and within) studies, a narrative approach to synthesis was used.

With regards to the methodological quality of the included studies, there were few examples of reliable and valid evaluations of intervention. It must be acknowledged that several studies eligible for inclusion in this review did not set out to deliver an ASD de-stigmatisation intervention. Many had a primary focus on change within the autistic individual (e.g. increased social skills), and peer data (although reported) was not a primary outcome. Nevertheless, regardless of the study aim, there were pervasive methodological flaws identified across studies in this review. There was a paucity of randomised control studies, and few employed appropriate control conditions or other means of controlling for confounding variables within and across groups (by design or analysis).

Selection bias was also identified as a pervasive concern. For several studies involving small groups/networks of participants, recruitment was biased towards those with desirable characteristics to increase engagement with the intervention (e.g. compliance, good social skills and academic performance, regular attendance), and not uncommonly a likelihood and/or expressed willingness to develop a relationship with a target child with ASD. In one included study, some participants were replaced during the intervention phase to increase the intervention effect (Owen-DeSchryver et al. Citation2008). By recruiting participants most likely to display the outcomes of interest, results in these studies were likely biased away from the null hypothesis.

Selection bias was also a concern in larger group designs, which frequently recruited only those unfamiliar with autism and/or from classrooms without autistic peers (i.e. autism novices) to explore the impact of the intervention on the stigmatisation of a hypothetical autistic peer. Preliminary findings from those studies that included participants both with and without previous ASD knowledge and/or contact found these populations differed in how they responded to different types of intervention (Campbell Citation2007; Campbell et al. Citation2019). Although the impact of the intervention is important to assess with novice populations, research is also required to evaluate these interventions in integrated/inclusive classrooms. Further, research focused exclusively on hypothetical rather than real peers raises questions of ecological validity. Future research should focus on exploring effects on both familiar and unfamiliar peers with autism.

There is insufficient data to establish the merit of peer education when targeting the stigma experienced by schoolchildren with ASD. To give confidence to the findings of this review, the 10 studies appraised for intervention effects were those rated as having the highest methodological quality from the sample of included studies. Even within this sample, the majority did not include a no-information control group in their design. There was one randomised control trial (randomisation process not reported) which found no effect of vignette intervention (regardless of information type used) on knowledge, attitudes or behavioural intentions (Campbell Citation2007). Studies that supported short single-session vignette type interventions were post-test only designs, without a control condition, and used self-report measures directly after implementation. A significant difference on a self-report measure directly following intervention is unsurprising, and without a no-information autism condition it is unclear if gains can be attributed to the intervention.

Campbell et al. (Citation2019), Staniland and Byrne’s (Citation2013) and Ranson and Byrne’s (Citation2014) pseudorandomised repeated measures control group designs found a positive effect of intervention for knowledge and attitudes, which maintained at follow-up. There was a non-significant effect of intervention on behavioural intentions towards ASD. These findings provide preliminary evidence that longer, or multi-session education programmes, which provide all four types of information, and delivered through a variety of mediums can reduce ignorance of and prejudice towards peers with ASD. However, these studies also relied on self-report, and the extent to which children’s actual behaviour can be predicted through self-reported behavioural intentions remains to be empirically verified. Future research should address this limitation by including more objective measurements of change, and by conducting high-quality research with actual behaviour as an outcome.

Further qualitative studies could prove invaluable when exploring the processes driving change in stigma. In the current review, Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell (Citation2017) qualitative exploration of the ‘Kit for Kids’ intervention found that despite participants reporting attitudinal and behavioural shifts towards an autistic peer, a theme of difference between children with and without autism, or an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ attitude, emerged. This seems detrimental to the aims of the intervention (Scheil, Bowers-Campbell, and Campbell Citation2017). Similarly, Whitaker et al. (Citation1998) criticised the ‘Circle of Friends’ approach (and similar peer network interventions) as deficit-based, and which places autistic children in the role of helpless support recipient. Thus, although interventions may reduce victimisation, prejudice and discrimination remain.

Three additional limitations of design common across included studies also warrant discussion. Firstly, in most studies a researcher or an expert delivered the educational component of the intervention, raising questions of ecological validity. This is an important variable to consider given that research from this review suggests ‘teacher’ versus ‘other’ delivery impacts intervention outcomes (Fleva Citation2014; Morton and Campbell Citation2008). Secondly, those studies judged most methodologically robust neglected to assess intervention effects with both the youngest and oldest schoolchildren. Across all studies, the mean age of participants (from the information reported) was 11 years, with their ASD target peers of a similar age. None of the included studies targeted pre-school/pre-kindergarten children, and infant schoolchildren (kindergarteners). Considering children begin to develop playmate preferences based on a growing awareness of difference at around three years of age (Rubin et al. Citation2005), interventions aimed at preventing stigmatisation of ASD in younger school-aged children should be developed and evaluated longitudinally for impact as a matter of priority. Finally, although there was a good gender balance of participants across studies, a potential confounding variable was the gender of the target child which was biased towards males. Current estimates of prevalence suggest the male-to-female ratio of autism is close to 3:1 (Loomes, Hull, and Mandy Citation2017), highlighting a considerable underrepresentation of autistic females in the reported research: only 13.6% and 12.5% of familiar and unfamiliar targets respectively. This limitation of the design is not uncommon in the ASD literature (Stedman et al. Citation2019), but clearly needs to be addressed in future research.

Limitations and conclusion

Some limitations of this review are worthy of acknowledgement. The review was limited to published evaluations of interventions. There are many examples of known toolkits, media, and campaigns designed to address the stigmatisation of autism in children who have not been empirically investigated, and thus were not considered in the current review. Stigma is also a broad term and the search parameters may not have been sufficient to identify all relevant literature. Related, the heterogeneity of included studies limited synthesis of the data, and a meta-analysis to assess the impact of the intervention was not possible. Furthermore, few studies were returned assessing ignorance (knowledge) as an outcome, and no studies rated as high in methodological rigour quantitively assessed actual behaviour change in participants. This limited interpretation.

Despite these limitations, this review provides some initial insight into the breadth of approaches used to target the stigmatisation of autism in school-aged peers. Limitations such as biased participant selection, the absence of control comparisons, a reliance on post-test only and self-report measurement, and variability in approach to intervention all make it difficult to draw firm conclusions. A critical appraisal of those 10 studies identified as the most robust in design provide some preliminary evidence for both benefit and feasibility of targeting ignorance and prejudice in school-age children, but as of yet not discrimination.

No one approach to intervention for this population can be determined as most effective, but results did highlight some positive findings for change in knowledge and attitudes when using longer programmes, combining all four types of information, delivered using a variety of mediums (i.e. ‘Kit for Kids’ and ‘Understanding Our Peers’). The results of this review also tentatively suggest the effectiveness of intervention could be improved by adapting delivery and content for different audiences (e.g. the person delivering the message). There is a need for further high-quality research to establish the utility of peer education de-stigmatising interventions for the inclusion of autistic classmates, and to determine what components of the intervention are most effective at improving stigma across domains. The results of the current review will hopefully inform these endeavours and future practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

S. Morris

Dr. S. Morris is a clinical psychologist working in child and adolescent mental health services.

G. O’Reilly

Dr. G. O'Reilly is the course director of the doctorate in clinical psychology programme University College Dublin.

J. Nayyar

Ms. J. Nayyar is a Ph.D. candidate in Psychology, University College Dublin.

Notes

1 The authors acknowledge the current debate in the literature regarding the language of describing individuals who meet criteria for autism spectrum disorder and how language may accentuate stigma (e.g. Gernsbacher Citation2017; Kenny et al. Citation2016; Robison Citation2019). This paper alternates between the use of person-first (e.g. person with autism) and identity-first (e.g. autistic person) language for those with and without autism, and between the terms autism and autism spectrum disorder.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 1980. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association. 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-V. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Bauminger, N., M. Solomon, A. Aviezer, K. Heung, L. Gazit, J. Brown, and S. J. Rogers. 2008. “Children with Autism and their Friends: A Multidimensional Study of Friendship in High-functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 36 (2): 135–150. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9156-x.

- Booth, T., and M. Ainscow. 1998. From Them to Us: An International Study of Inclusion in Education. London: Routledge.

- Campbell, J. 2007. “Middle School Students’ Response to the Self-introduction of a Student with Autism: Effects of Perceived Similarity, Prior Awareness, and Educational Message.” Remedial and Special Education 28 (3): 163–173. doi:10.1177/07419325070280030501.

- Campbell, J., and B. Barger. 2011. “Middle School Students’ Knowledge of Autism.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 41 (6): 732–740. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1092-x.

- Campbell, J., E. Caldwell, K. Railey, O. Lochner, R. Jacob, and S. Kerwin, Eckert Tanya. 2019. “Educating Students About Autism Spectrum Disorder Using the Kit for Kids Curriculum: Effects on Knowledge and Attitudes.” School Psychology Review 48 (2): 145–156. doi:10.17105/SPR-2017-0091.V48-2.

- Campbell, J., J. Ferguson, C. Herzinger, J. Jackson, and C. Marino. 2004. “Combined Descriptive and Explanatory Information Improves Peers’ Perceptions of Autism.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 25 (4): 321–339. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2004.01.005.

- Campbell, J., J. Ferguson, C. Herzinger, J. Jackson, and C. Marino. 2005. “Peers’ Attitudes Toward Autism Differ Across Sociometric Groups: An Exploratory Investigation.” Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 17 (3): 281–298. doi:10.1007/s10882-005-4386-8.

- Campbell, M., Y. Hwang, C. Whiteford, J. Dillon-Wallace, J. Ashburner, B. Saggers, and S. Carrington. 2017. “Bullying Prevalence in Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Australasian Journal of Special Education 41 (2): 101–122. doi:10.1017/jse.2017.5.

- Carter, E., J. Redding, K. Bottema-Beutel, H. Fan, K. Gardner, M. Harvey, and A. Stabel. 2014. Peer network facilitator manual.

- Chamberlain, B., C. Kasari, and E. Rotheram-Fuller. 2007. “Involvement or Isolation? The Social Networks of Children with Autism in Regular Classrooms.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 37 (2): 230–242. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0164-4.

- Collet-Klingenburg, L., J. Neitzel, and J. LaBerge. 2012. “Power-PALS (Peers Assisting, Leading, Supporting): Implementing a Peer-mediated Intervention in a Rural Middle School Program.” Rural Special Education Quarterly 31 (2): 3–11. doi:10.1177/875687051203100202.

- Connor, M. 2000. “Asperger Syndrome (Autistic Spectrum Disorder) and the Self-reports of Comprehensive School Students.” Educational Psychology in Practice 16 (3): 285–296. doi:10.1080/713666079.

- Cook, M. 2017. Peer Support Arrangements in the Inclusive Middle School Setting: An In-depth Look from Observations, Work Samples and Participant Perspectives. University of Michigan – Flint]. Michigan. Covidence systematic review software. In. Veritas Health Innovation. www.covidence.org.

- Croll, P. 2001. “Children with Statements in Mainstream Key Stage Two Classrooms: A Survey in 46 Primary Schools.” Educational Review 53 (2): 137–145. doi:10.1080/00131910120055561.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2019. Education Indicators for Ireland: October 2019. https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Statistics/Key-Statistics/education-indicators-for-ireland.pdf.

- Dillenburger, K., J. A. Jordan, L. McKerr, K. Lloyd, and D. Schubotz. 2017. “Autism Awareness in Children and Young People: Surveys of Two Populations.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 61 (8): 766–777. doi:10.1111/jir.12389.

- Elig, T. W., and I. H. Frieze. 1979. “Measuring Causal Attributions for Success and Failure.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37 (4): 621–634. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.4.621.

- Ezzamel, N. 2016. Peer-mediated Interventions for Pupils with ASD in Mainstream Schools: A Tool to Promote Social Inclusion. Manchester: University of Manchester.

- Ezzamel, N., and C. Bond. 2017. “The use of a Peer-mediated Intervention for a Pupil with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Pupil, Peer and Staff Perceptions.” Educational and Child Psychology 34 (2): 27–39.

- Fleva, E. 2014. “Attitudes and Behavioural Intentions of Typically Developing Adolescents Towards a Hypothetical Peer with Asperger Syndrome.” World Journal of Education 4 (6): 54–65. doi:10.5430/wje.v4n6p54.

- Fleva, E. 2015. “Imagined Contact Improves Intentions Towards a Hypothetical Peer with Asperger Syndrome But not Attitudes Towards Peers with Asperger Syndrome in General.” World Journal of Education 5 (1): 1–12. doi:10.5430/wje.v5n1p1.

- Frederickson, N., and B. Graham. 1999. Social Skills and Emotional Intelligence: Psychology in Education Portfolio. Windsor: NFER-Nelson.

- Frederickson, N., L. Warren, and J. Turner. 2005. “Circle of Friends”: An Exploration of Impact Over Time.” Educational Psychology in Practice 21 (3): 197–217. doi:10.1080/02667360500205883.

- Gardner, K. F., E. W. Carter, J. R. Gustafson, J. M. Hochman, M. N. Harvey, T. S. Mullins, and H. Fan. 2014. “Effects of Peer Networks on the Social Interactions of High School Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 39 (2): 100–118. doi:10.1177/1540796914544550.

- Gernsbacher, M. 2017. “Editorial Perspective: The Use of Person-First Language in Scholarly Writing May Accentuate Stigma.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 58 (7): 859–861. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12706.

- Godleski, S. A., K. E. Kamper, J. M. Ostrov, E. J. Hart, and S. J. Blakely-McClure. 2015. “Peer Victimization and Peer Rejection During Early Childhood.” Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 44 (3): 380–392. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.940622.

- Government of Ireland. 1998. Education Act. Dublin: The Stationary Office.

- Government of Ireland. 2004. Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act. Dublin: The Stationary Office.

- Gray, C. 2002. The Sixth Sense II. Michigan: Future Horizons Inc.

- Gus, L. 2000. “Autism: Promoting Peer Understanding.” Educational Psychology in Practice 16 (4): 461–468. doi:10.1080/713666109.

- Hebron, J., N. Humphrey, and J. Oldfield. 2015. “Vulnerability to Bullying of Children with Autism Spectrum Conditions in Mainstream Education: A Multi-Informant Qualitative Exploration.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 15 (3): 185–193. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12108.

- Houston, F. 1998. Combined Interventions: Using Social Skills Training and Peer-mediated Interventions in an Integrated Group Setting to Facilitate the Development of Social Skills in Students with Autism. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama.

- Hughes, C., M. Harvey, J. Cosgriff, C. Reilly, J. Heilingoetter, N. Brigham, L. Kaplan, and R. Bernstein. 2013. “A Peer-Delivered Social Interaction Intervention for High School Students with Autism [Article].” Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 38 (1): 1–16. doi:10.2511/027494813807046999.

- Humphrey, N., and W. Symes. 2010. “Perceptions of Social Support and Experience of Bullying among Pupils with Autistic Spectrum Disorders in Mainstream Secondary Schools.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 25 (1): 77–91. doi:10.1080/08856250903450855.

- Humphrey, N., and W. Symes. 2011. “Peer Interaction Patterns among Adolescents with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) in Mainstream School Settings.” Autism 15 (4): 397–419. doi:10.1177/1362361310387804.

- James, R. 2011. An Evaluation of the ‘Circle of Friends’ Intervention Used to Support Pupils with Autism in their Mainstream Classrooms. Nottingham: University of Nottingham.

- Kasari, C., J. Locke, A. Gulsrud, and E. Rotheram-Fuller. 2011. “Social Networks and Friendships at School: Comparing Children with and Without ASD.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 41 (5): 533–544. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x.

- Kenny, L., C. Hattersley, B. Molins, C. Buckley, C. Povey, and E. Pellicano. 2016. “Which Terms Should Be Used to Describe Autism? Perspectives from the UK Autism Community.” Autism 20 (4): 442–462. doi:10.1177/1362361315588200.

- Keating-Velasco, J. 2007. A is for Autism F is for Friend: A Kid's Book on Making Friends with a Child who has Autism. Kansas: Autism-Asperger Publishing Company.

- Loomes, R., L. Hull, and W. Mandy. 2017. “What is the Male-to-female Ratio in Autism Spectrum Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 56 (6): 466–474. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013.

- Magiati, I., J. E. Dockrell, and A.-E. Logotheti. 2002. “Young Children's Understanding of Disabilities: The Influence of Development, Context, and Cognition.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 23 (4): 409–430. doi:10.1016/S0193-3973(02)00126-0.

- Mavropoulou, S., and G. D. Sideridis. 2014. “Knowledge of Autism and Attitudes of Children Towards Their Partially Integrated Peers with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44 (8): 1867–1885. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2059-0.

- Morgan, S. B., M. Walker, A. Bieberich, and S. Bell. 1996. The Shared Activities Questionnaire. Memphis: University of Memphis.

- Morton, J., and J. Campbell. 2008. “Information Source Affects Peers’ Initial Attitudes Toward Autism.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 29 (3): 189–201. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2007.02.006.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2012a. Methods for the Development of NICE Public Health Guidance (Third Edition): Appendix F Quality Appraisal Checklist – Quantitative Intervention Studies. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/appendix-f-quality-appraisal-checklist-quantitative-intervention-studies.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2012b. Methods for the Development of NICE Public Health Guidance (Third Edition): Appendix H Quality Appraisal Checklist – Qualitative Studies. NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/appendix-h-quality-appraisal-checklist-qualitative-studies.

- Newton, C., G. Taylor, and D. Wilson. 1996. “Circles of Friends.” Educational Psychology in Practice 11 (4): 41–48. doi:10.1080/0266736960110408.

- O’Connor, E. 2016. “The use of ‘Circle of Friends’ Strategy to Improve Social Interactions and Social Acceptance: A Case Study of a Child with Asperger's Syndrome and Other Associated Needs.” Support for Learning 31 (2): 138–147. doi:10.1111/1467-9604.12122.

- Organization for Autism Research. 2012. What's up with Nick? Arlington, VA: Organization for Autism Research.

- Osler, A., and C. Osler. 2002. “Inclusion, Exclusion and Children's Rights: A Case Study of a Student with Asperger Syndrome.” Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 7 (1): 35–54. doi:10.1080/13632750200507004.

- Owen-DeSchryver, J. 2002. The Boy in My Class. Allendale, MI: Grand Valley State University.

- Owen-DeSchryver, J., E. Carr, S. Cale, and A. Blakeley-Smith. 2008. “Promoting Social Interactions between Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Their Peers in Inclusive School Settings.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 23 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1177/1088357608314370.

- Pearpoint, J., M. Forest, and J. Snow. 1992. The Inclusion Papers: Strategies to Make Inclusion Work. Toronto: Inclusion Press.

- Ranson, N. J., and M. K. Byrne. 2014. “Promoting Peer Acceptance of Females with Higher-Functioning Autism in a Mainstream Education Setting: A Replication and Extension of the Effects of an Autism Anti-Stigma Program.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44 (11): 2778–2796. doi:10.1007/s1083-014-2139-1.

- Reiter, S., and T. Vitani. 2007. “Inclusion of Pupils with Autism: The Effect of an Intervention Program on the Regular Pupils’ Burnout, Attitudes and Quality of Mediation.” Autism 11 (4): 321–333. doi:10.1177/1362361307078130.

- Robison, J. E. 2019. “Talking about Autism: Thoughts for Researchers.” Autism Research 12 (7): 1004–1006. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2119.

- Rosenbaum, P. L., P. L. Rosenbaum, R. W. Armstrong, R. W. Armstrong, S. M. King, and S. M. King. 1986. “Children's Attitudes Toward Disabled Peers: A Self-Report Measure.” Journal of Pediatric Psychology 11 (4): 517–530. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/11.4.517.

- Ross, P., and M. Cuskelly. 2006. “Adjustment, Sibling Problems and Coping Strategies of Brothers and Sisters of Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 31 (2): 77–86. doi:10.1080/13668250600710864.

- Rowley, E., S. Chandler, G. Baird, E. Simonoff, A. Pickles, T. Loucas, and T. Charman. 2012. “The Experience of Friendship, Victimization and Bullying in Children with an Autism Spectrum Disorder: Associations with Child Characteristics and School Placement.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 6 (3): 1126–1134. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2012.03.004.

- Rubin, K., R. Coplan, X. Chen, A. Buskirk, and J. Wojslawowicz. 2005. “Peer Relationships in Childhood.” In Developmental Science: An Advanced Textbook, edited by M. Bornstein, and M. Lamb, 469–512. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Scheil, K., J. Bowers-Campbell, and J. Campbell. 2017. “An Initial Investigation of the Kit for Kids Peer Educational Program.” Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 29 (4): 643–662. doi:10.1007/s10882-017-9540-6.

- Schroeder, J., C. Cappadocia, J. Bebko, D. Pepler, and J. Weiss. 2014a. “Shedding Light on a Pervasive Problem: A Review of Research on Bullying Experiences among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44 (7): 1520–1534. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-2011-8.

- Schroeder, J. H., M. C. Cappadocia, J. M. Bebko, D. J. Pepler, and J. A. Weiss. 2014b. “Shedding Light on a Pervasive Problem: A Review of Research on Bullying Experiences Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44 (7): 1520–1534. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-2011-8.

- Shally, C., and D. Harrington. 2007. Since We're Friends: An Autism Picture Book. Hong Kong: Awaken Speciality Press.

- Silton, N. R., and J. Fogel. 2012. “Enhancing Positive Behavioural Intentions of Typical Children Towards Children with Autism.” Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies 12 (2): 139–158.

- Simpson, L. A., and Y. Bui. 2016. “Effects of a Peer-mediated Intervention on Social Interactions of Students with Low-functioning Autism and Perceptions of Typical Peers.” Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 51 (2): 162–178.

- Siperstein, G. N. 1980. Development of the Adjective Checklist: An Instrument for Measuring Children's Attitudes Towards the Handicapped. Boston: University of Massachusetts.

- Siperstein, G. N., and J. J. Bak. 1977. Instruments to Measure Children's Attitudes Towards the Handicapped: Adjective Checklist and Activity Preference List. Boston: University of Massachusetts.

- Sreckovic, M. A. 2015. Peer Network Interventions for Secondary Students with ASD: Effects on Social Interaction and Bullying Victimization. Chapel Hill: University of Nottingham.

- Sreckovic, M. A., K. Hume, and H. Able. 2017. “Examining the Efficacy of Peer Network Interventions on the Social Interactions of High School Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 47 (8): 2556–2574. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3171-8.

- Staniland, J. J., and M. K. Byrne. 2013. “The Effects of a Multi-component Higher-functioning Autism Anti-stigma Program on Adolescent Boys.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 43 (12): 2816–2829. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1829-4.

- Stedman, A., B. Taylor, M. Erard, C. Peura, and M. Siegel. 2019. “Are Children Severely Affected by Autism Spectrum Disorder Underrepresented in Treatment Studies? An Analysis of the Literature.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 49 (4): 1378–1390. doi:10.1007/s10803-018-3844-y.

- Sterne, J. A. C., M. A. Hernán, B. C. Reeves, J. Savović, N. D. Berkman, M. Viswanathan, D. Henry David, et al. 2016. “ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in non-Randomised Studies of Interventions.” BMJ 355: i4919. doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919.

- Sutton, B. M., A. A. Webster, and M. F. Westerveld. 2019. “A Systematic Review of School-Based Interventions Targeting Social Communication Behaviors for Students with Autism.” Autism 23 (2): 274–286.

- Swaim, K. F. 1998. “Children's Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions Toward a Peer Presented As Having Autism: Does a Brief Educational Intervention Have an Effect?” Doctor of Philosophy, The University of Memphis, Memphis.

- Swaim, K. F., and S. B. Morgan. 2001. “Children's Attitudes and Behavioural Intentions Toward a Peer with Autistic Behaviors: Does a Brief Educational Intervention Have an Effect?” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 31 (2): 195–205. doi:10.1023/A:1010703316365.

- Symes, W., and N. Humphrey. 2010. “Peer-group Indicators of Social Inclusion among Pupils with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in Mainstream Secondary Schools: A Comparative Study.” School Psychology International 31 (5): 478–494. doi:10.1177/0143034310382496.

- Taylor, G. 1996. “Creating a Circle of Friends: A Case Study.” In Peer Counselling in School, edited by H. Cowie, and S. Sharp, 73–86. London: David Fulton.

- Taylor, G. 1997. “Community Building in Schools: Developing a Circle of Friends.” Educational and Child Psychology 14: 45–50.

- Thornicroft, G., D. Rose, A. Kassam, and N. Sartorius. 2007. “Stigma: Ignorance, Prejudice or Discrimination?” The British Journal of Psychiatry 190 (3): 192–193. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025791.

- Turner, J. 1999. Circle of Friends. Buckinghamshire, UK: Buckinghamshire County Council Educational Psychology Service.

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation. 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Paris: UNESCO.

- Veenstra, R., S. Lindenberg, A. Munniksma, and J. K. Dijkstra. 2010. “The Complex Relation Between Bullying, Victimization, Acceptance, and Rejection: Giving Special Attention to Status, Affection, and sex Differences.” Child Development 81 (2): 480–486. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01411.x.

- Veenstra, R., S. Lindenberg, B. J. H. Zijlstra, A. F. De Winter, F. C. Verhulst, and J. Ormel. 2007. “The Dyadic Nature of Bullying and Victimization: Testing a Dual-Perspective Theory.” Child Development 78 (6): 1843–1854. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01102.x.

- Wainscot, J., P. Naylor, P. Sutcliffe, D. Tantam, and J. Williams. 2008a. “Relationships with Peers and use of the School Environment of Mainstream Secondary School Pupils with Asperger Syndrome (High-Functioning Autism): A Case-control Study.” International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy 8 (1): 25–38.

- Wainscot, J. J., P. Naylor, P. Sutcliffe, D. Tantam, and J. V. Williams. 2008b. “Relationships with Peers and Use of the School Environment of Mainstream Secondary School Pupils with Asperger Syndrome (High-Functioning Autism): A Case-control Study.” International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy 8 (1): 25–38.

- Ware, J., C. Butler, C. Robertson, M. O'Donnell, and M. Gould. 2011. Access to the Curriculum for Pupils with a Variety of Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Classes: An Exploration of Young Pupils in Primary Schools. NCSE. https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/AccesstotheCurriculum_1.pdf.

- Whitaker, P., P. Barratt, H. Joy, M. Potter, and G. Thomas. 1998. “Children with Autism and Peer Group Support: Using Circles of Friends.” British Journal of Special Education 25 (2): 60–64. doi:10.1111/1467-8527.t01-1-00058.