ABSTRACT

The meaning of the term ‘inclusion’ is often taken for granted and seldom defined. Empirical research on inclusive education is often normative since it is based on terms such as ‘justice’ and ‘democracy’. Such terms are challenging to translate into real practice because their meanings depend on a subjective evaluation related to the time and place where inclusion is supposed to happen. Inclusive education, therefore, is challenging to explore in research and to achieve in educational situations. This article explores the understanding of inclusive education through the lens of social system theory developed by Niklas Luhmann as well as theory of institutionalism. With the perspectives underlying mechanisms that create inclusion and exclusion in schools are identified at different institutional levels. Furthermore it is shown how subsystems include and exclude, i.e. what criteria apply to the access and rejection of a system. In this theoretical contribution to understanding inclusive education, we seek to intertwine Luhmann’s theory of inclusion and exclusion with the institutional theory of the social construction of reality to discuss how policy, management, teaching, student relationships, and everything within the context of education that involves communication can create institutionalised systems with mechanisms that form persistent exclusion for some students.

Introduction

The general focus on school inclusion can be traced back to The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education that was crafted in 1994 (UNESCO Citation1994). The Salamanca document features normative principles for inclusion that recognise institutions that include every student, highlight diversity as an asset, support learning, and respond to individual needs (UNESCO Citation1994, Citation2020). Beyond Salamanca, interest in inclusive education has risen in member states and organisations that signed the statement, politics, and research and educational organisations. However, the understanding and definition of the concept and development of inclusive practices differ in and between different countries and make researching inclusive education even more essential for understanding what inclusion is and how it can be achieved (Hernández-Torrano, Somerton, and Helmer Citation2020). Lately, several schools have produced systematic reviews on the concept of inclusion and have noted that the definition of inclusive education differs between theoretical approaches. Some believe that the core concept of inclusion only concerns specific groups or categories of people, whereas others maintain that inclusion involves everyone (Nilholm and Göransson Citation2017). Commonly, researchers who study inclusive education refer to the Salamanca statement to highlight the importance of social justice, democracy, and the elimination of all forms of exclusion and discrimination (Hernández-Torrano, Somerton, and Helmer Citation2020). However, inclusive education as a normative, based policy is challenging to explore in research and to achieve in specific educational situations because context and individuals differ from situation to situation (Caspersen et al. Citation2020; Halinen and Järvinen Citation2008).

This article aims to contribute to the theoretical understanding of inclusion to explore how inclusion and exclusion are continually ongoing processes that are constructed by communication at different levels in society. Few authors have discussed inclusion’s conceptual framework regarding schools using sociological perspectives (Felder Citation2018), and not many researchers have used Niklas Luhmann’s theory to discuss the theoretical aspects of the notion of inclusion in schools (Baraldi and Corsi Citation2017; Hilt Citation2017; Qvortrup and Qvortrup Citation2018). Because inclusive education is a complex process to study and achieve, we suggest using system theory and the concept of inclusion and exclusion to understand how students can be included and excluded by various forms of communication during a typical school day. Moreover, we try to integrate the systemically theoretical concepts of inclusion and exclusion with the social-constructionist perspective that was developed by Berger and Luckmann (Citation1966) to demonstrate how people in communication with each other socially construct everyday life and how such interactions can create systems for inclusion and exclusion. We also want to reveal how these systems form a construction in relation to the institutional environment.

In this article, we argue for the use of a combined theoretical model that utilises three useful perspectives and their associated conceptual frameworks. We will first describe existing research and interpretations of theories that relate to inclusive education. Then we will discuss some challenges related to achieving complete inclusion before demonstrating the usefulness of social-constructionist theory (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966; Meyer Citation2010). We will also utilise the theoretical perspective of Niklas Luhmann’s system theory (Luhmann Citation1995) and the concepts of inclusion and exclusion (Luhmann and Rasch Citation2002). Finally, we will argue for a theoretical framework that comprises concepts that can help researchers understand how persistently inclusion and exclusion are formed.

A brief review of the field

Research about inclusive education is extensive and complex. Inclusive education focuses on students with disabilities and every student; it also focuses on educational policies and organisations. Researchers have used different theoretical approaches and methods to explore and act. Because of the size of the field and the complexity of the concept, the research branches out in several directions. However, articles published in the field often present the political ideas contained in the Salamanca statement.

Researching inclusive education is important since it focuses on social justice and democracy (Hernández-Torrano, Somerton, and Helmer Citation2020). The Salamanca statement, which was signed by 92 member nations and 25 international organisations, places the responsibility for inclusive education onto governments and their educational organisations. The main goal of related policies is to counteract discrimination and exclusion that target diversity (Ainscow and Miles Citation2008; Ainscow, Slee, and Best Citation2019). However, the idea of inclusion refers not only to diversity in the form of ability: it also refers to other differences such as gender and cultural background or the ways that schools structure and address these differences (Sturm Citation2019). Because the concept has political implications, theoretical frameworks that deal with understanding the concept of inclusive education often refer to UNESCO or local policies.

Since the concept of inclusion is outlined according to a normative, political idea of democracy and justice, it is not surprising that the idea of inclusive education in research is hard to grasp. The concept is complex, broad, and ambiguous (Szumski, Smogorzewska, and Karwowski Citation2017); therefore, it is challenging to study and to construct (Ainscow and Sandill Citation2010; Forlin Citation2010). Researchers’ understandings of the key concepts and definitions that relate to inclusive education differ between scholars and countries (Brusling and Pepin Citation2003). Different definitions and complex perspectives affect the research on the topic, as well as the possibility of achieving inclusive education in practice (Göransson and Nilholm Citation2014). A vast array of interests is attached to the idea of inclusive education, and definitions of the concept differ around the world. Therefore, inclusive education is subjected to multiple definitions that problematise at least cross-national research on it (Hernández-Torrano, Somerton, and Helmer Citation2020). However, several reviews of the field have contributed to the overview of the different approaches.

Sorting out the ideas

When studying inclusive education, scholars have differed on the study objective. Some researchers have incorporated all forms of student diversity in their definitions of inclusive education (Florian, Young, and Rouse Citation2010), and others have referred to curricula, teaching and learning in their definitions (Westwood Citation2018). Other researchers have defined inclusion as relating to educational leadership (Randel et al. Citation2018). The concept varies from framing inclusion as relating to disabilities and special educational needs (Fasting, Hausstätter, and Turmo Citation2011; Vislie Citation2003, Citation2004) to framing inclusion as a normative principle in society (Van Mieghem et al. Citation2020). Differences in implementing inclusive education involve ideas about how education should be organised. Therefore, politicians, researchers and practitioners perceive inclusive education differently concerning what schools can and should do to help inclusive education succeed (Göransson and Nilholm Citation2014).

Inclusion is associated with diversity (Burner, Nodeland, and Aamaas Citation2018; Devarakonda and Powlay Citation2016; Loreman, Deppeler, and Harvey Citation2005), equity (Goodwin Citation2012; Shaeffer Citation2019), equality (Eklund et al. Citation2012; Lundahl Citation2016), citizenship (McAnelly and Gaffney Citation2019; Nutbrown and Clough Citation2009), and the universal right to sufficient and adapted education (Gran Citation2017; McAnelly and Gaffney Citation2019). In pedagogy and special pedagogy, the concept has been defined as a student’s belonging to a professional, social and cultural community, and inclusion also concerns participation quality, democratisation, and dividends in education (Solli Citation2010).

The degree of inclusion has also been discussed. Haug (Citation2016) identified four elements that he described as the degrees of inclusion: increasing the community, increasing participation, increasing democratisation, and increasing dividends. Inclusion has also been described as a program that helps schools adapt to the diversity of children. Children should be placed, received, or allowed to participate in a regular school setting, and the school, as much as possible, should realise the whole set of its objectives for all groups of students. One could hardly talk about inclusion if this is not the claim (Caspersen et al. Citation2020).

In their mapping of research on inclusive education after 1994, Hernández-Torrano, Somerton, and Helmer (Citation2020) defined four schools of research: systems and structures, special education, accessibility and participation, and critical research. In their review, they found a progressive and steady increase in publications on inclusive education that began in 2004 and continues today. Their analysis defined various themes, including higher education settings and issues related to accessibility, teachers’ education and attitudes about inclusive education, inclusion in teaching, collaboration and professional development, and practices and principles for inclusive schools and classrooms. In a thematic analysis of 26 reviews, Van Mieghem et al. (Citation2020) discovered five main themes: attitudes towards inclusive education, teachers’ professional development regarding the issue, inclusive educational practices, student participation and critical reflections on inclusive educational research.

Inclusion and exclusion – towards a theory of systems

The main goal of the educational system is to function as an integrational institution in society, and inclusive education is often seen as the way to reach this goal. In some cases, inclusion and integration are difficult to separate. Based on what has been written about inclusion and integration in Europe, Bricker (Citation1995, Citation2000) and Vislie (Citation2003, Citation2004) suggested that the two concepts could and should be separated because they have different focuses. When the concept of integration first came up in the 1960s and 1970s (Dockar-Drysdale Citation1966), researchers linked it to processes at the systemic level and reforms concerning all students’ right to education, including education in local schools for children with disabilities (Ewing Citation1962; O’Flanagan Citation1960; Wallin Citation1966) and the integration between special education and the regular school system (Ekstrom Citation1970). In comparison to integration, Vislie (Citation2003) argued that the concept of inclusion is considerably broader. The alternative term ‘inclusion’ was introduced to describe the quality of teaching offered to students with special needs in integrated contexts and to describe what teaching that includes all students with diverse needs should look like. The term ‘inclusion’ was further developed to include good praxis that includes every student.

The content of the term ‘inclusion’ must capture a wide range of school objectives (Caspersen, Smeby, and Olaf Aamodt Citation2017; Caspersen et al. Citation2020). However, practical research on inclusion is as much about counteracting exclusion as it is about creating the right conditions for inclusion and equal learning opportunities (Weiner Citation2003). Working with inclusion is not about creating inclusion for special groups: the goal is to transform the school into a long-term democratisation project that provides all children with good educations and reduces all forms of exclusion (Nevøy and Ohna Citation2014). Moreover, there is a gap between inclusion as rhetoric and praxis: ‘Uncertainty in the content of meaning is reflected in the relationship between ideal and practice. Diversity and inclusion are celebrated in the political rhetoric, but there are few concrete instructions on what it should mean in practice’ (Solli Citation2010, 30).

This article seeks to understand and explore inclusion and exclusion in education in a way that focuses on students in general. This article also aims to consider a broad spectrum of situations and institutional and organisational levels. The model we present is useful for both research and practice. The theoretical model developed in this article is useful for understanding how to determine the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion at different levels and in different situations concerning all students in the educational system. Moreover, we will include a way to explore the link between policy and praxis in our model by using the concepts of inclusion and exclusion. Even though a few researchers have claimed that inclusion is the other side of exclusion, it is difficult to leave the normative idea that inclusion is a form of social justice and a democratic project and move towards the idea that every child is included in some settings in school and excluded from others (Booth Citation2018; Popay Citation2010). Thinking in this way means that we must admit that most children are excluded from more areas than they are included in (Luhmann Citation1995), which is an argument that does not fit with most educational policies. Research on inclusive education often compares praxis with normative policies on global or local levels. The complicated link between policy and practice needs to be further explored, and theoretical concepts are needed to explain whether a policy is followed and why a policy does not work in practice (Azorín and Ainscow Citation2020). The process of translating policy into practice is complicated on micro and macro societal levels. Sometimes, contradictions between different policy goals that are related to inclusion create exclusion when they are translated into the field of practice; for example, one policy might require every child to work in the same classroom. but another policy might require them to use different curricula (Shawer Citation2017). In this scenario, a child could potentially be socially included but academically excluded (Hymel and Katz Citation2019). Furthermore, policies do not automatically make children socially included in a group just because they are physically included in classroom settings (Sokal and Katz Citation2017).

Theoretical frame

The theoretical framework that we suggest should be used to study inclusive education stems from sociology in system theory as well as social-constructionist theory. In social science, the concept of exclusion often appears with its conceptual partner, inclusion, which is linked to ideas that stem from integration and solidarity, which have political connections to the French 70s (Silver Citation1994). Aasland and Fløtten (Citation2010), as well as Qvortrup and Qvortrup (Citation2018), viewed exclusion as a multidimensional phenomenon in which different variables that are related to living conditions function as indicators of degrees of inclusion in and exclusion from educational rights, civil rights, the labour market, participation in civil society, and social arenas. Such an approach identifies social problems without examining the relationship between the problems and the reasons for exclusion, such as the mechanisms that govern why certain categories of people participate politically while others do not (Amin Citation2019; Rawal Citation2008; Syahra Citation2010). According to these ideas, exclusion in education often leads to exclusion in other areas of society due to the importance of education for inclusion, in among others, the labour market (Vanderstraeten Citation2020).

To study how a school works towards inclusion, one must consider the binary concept of exclusion; only then is it possible to explore what mechanisms are at work and understand how inclusion and exclusion take place and what criteria determine inclusion and exclusion in a specific context. Degrees of students’ inclusion that concern an unclear concept are difficult to identify and are, therefore, difficult for an organisation to manage. In the next part, we will discuss an alternative way to theoretically understand inclusive education.

System theory by Niklas Luhmann

System theory is sometimes used in research on inclusive education. For example, Qvortrup and Qvortrup (Citation2018) suggested in their article that an operational definition of inclusion that is differentiated according to three dimensions is needed to handle inclusion as a phenomenon that concerns all children. They suggested that we must define different levels of inclusion, different types of social communities where inclusion and exclusion can take place, and different degrees of inclusion and exclusion in different communities. In our theoretical framework, we explore the use of Luhmann’s system theory and the concepts of inclusion and exclusion.

Luhmann’s theory about society as a conglomerate of self-referential social systems investigates how these systems construct meaning and how these constructions affect inclusive and exclusive processes (Hilt Citation2017). We define the concept of inclusion as being inextricably intertwined with the notion of exclusion and strongly connected to the functional differentiation of society. Inclusion and exclusion are connected to systems of communication that interlink and define the operations that are included in the system (Luhmann Citation1995; Luhmann Citation1977; Vanderstraeten Citation2004). These social systems consist of meaningful contexts regarding social actions that refer to each other and delimit the outside world. The different systems respond to a complex environment and are built on the communication of needs, such as the need for adaptive education.

The concept of inclusion is inextricably intertwined with the functional differentiation of society (Luhmann and Rasch Citation2002). They claimed that it is no longer possible as a human being to be more or less integrated into society as a system since people are born into social classes in segmented societies that define their lives and conditions. In such societies, the order of inclusion follows the differentiation principle of society. Society, according to Luhmann and Rasch (Citation2002; Citation1995), consists of several socially inclusive and exclusive sub-systems such as politics, economics, religion, education, work, science, and so on. According to Qvortrup and Qvortrup (Citation2018), these sub-systems can be described as different communities in relation to educational inclusion. They suggested distinguishing between society, organisations and interactions, where inclusion and exclusion must be understood in relation to functional sub-systems. These systems are based on individual forms and principles that include one aspect of the outside world and exclude everything else (Luhmann Citation1995). The form inevitably arises when operations are interlinked and thus defines which operations are suitable for inclusion in the system (Luhmann Citation1995). At the societal level (Qvortrup and Qvortrup Citation2018), inclusion and exclusion take place in relation to specific social systems within society. Meaningful content acts as the internal node around which communication in the system is centred. Therefore, the activity in a classroom can create and consist of many different social sub-systems.

Communication, according to Luhmann (Citation1995), consists of information, messages, and understanding and is performed through linguistic and physical actions. Since a system produce the same communication that it is built around, it can be considered autopoietic. Different social systems can be seen as responses to a complex environment – they need to communicate a need. When a student in an educational system cannot follow along with regular teaching, they need something else that the broader educational system cannot provide. Once this is determined, several possibilities for systemic differentiation arise. According to policy, an inclusive system will differentiate in, for instance, adaptive teaching or special education in the classroom. However, system differentiation in a policy-compliant system can be exclusive in other ways; for example, it can be socially or academically exclusive.

The different systems base their communication on contingency – that is, the idea that things could have been different. Contingency relates to inclusion and exclusion. When actors within a system choose which types of communication to include, they also choose which types to exclude. Communication choices risk not contributing to maintaining a system (Luhmann Citation1995; Ritzer Citation2000). Inclusion is, in other words, the inner side of the form, while exclusion is the outer side.

Some principles in society are designed to ensure the integration of individuals. Civil rights and human rights are some examples of such principles. These principles are normative since they are based on a kind of justice policy and measure inclusion based on the same normative principles that society has created for itself. According to Luhmann, these principles only mean that people have equality in the right and freedom to enter into contracts with specific functional systems. However, that right and freedom are used differently by people, and the functional system determines the criteria for inclusion and exclusion. A functionally differentiated society can tolerate extreme differences in the distribution of public and private resources. Still, this idea presupposes equality in the law and freedom (i.e. the principles of inclusion for a given system can be legitimised by anyone who can achieve them, and exclusion can be seen as temporary and vulnerable to change) (Luhmann and Rasch Citation2002). The codes and legitimisation of different sub-systems in education are created through policies and are translated (Sahlin and Wedlin Citation2008) by schools’ employees. Binary codes and legitimisation are also socially constructed forms of communication that are used by individual actors in educational systems and are institutionalised as sub-systems within schools (Emmerich Citation2020). When it comes to education, ‘non-education’ does not always mean ‘non-education’ in a literal sense. The empirical correlation between overlaps and other societal systems is clear: education provides work, whereas non-education increases the risk of exclusion and marginalisation.

As illustrated previously, Luhmann’s theory of society is a theory about a system of systems in which several inclusive and exclusive mechanisms act. According to this perspective, inclusive and exclusive mechanisms are and will always be a reality that must be dealt with. It is unrealistic and conceptually impossible to think that everyone can be included in an organisation or an interactive system. Instead, we are dealing with a complex, sophisticated, and flexible system made of inclusions and exclusions. As illustrated, the inclusive and exclusive processes in schools correspond to or resemble the inclusive and exclusive processes in society to a great extent. This means that focusing on the complexities of inclusion is not only relevant as a prerequisite for managing the inclusion of all children, but it is also a way of preparing children for participation in society (Qvortrup and Qvortrup Citation2018). However, if social systems continually include or exclude communication that hinders inclusive education, is there anything that can be done about it? In the next part, we suggest that human beings who create norms and institutions that affect communication in social systems construct social systems.

System theory in a social-constructionist perspective

In developing a theoretical model useful to research inclusive education, we used institutional theory to interpret the concept of inclusion. In 1966, Berger and Luckmann described institutionalisation as ‘[t]he social construction of reality’ and claimed that people socially construct institutions through their everyday communication with each other. From the social-constructionist perspective, researchers have studied how the individual relates to the social constructions of history and culture (Sempowicz et al. Citation2018). Social constructionism has been used to interpret how inclusion theories and principles relate to early childhood education (Jamero Citation2019; Mallory and New Citation1994) and to define the conceptual framework of inclusion in the United States (Dudley-Marling and Burns Citation2014). It has also been used to interpret professional practices that follow the Vygotskyan concept of scaffolding (Armstrong Citation2019; Walker and Berthelsen Citation2008) and social norms and tools that reflect social-interactionist approaches and social constructionism in schools (Carrington et al. Citation2020; Joy and Murphy Citation2012; Sempowicz et al. Citation2018).

Berger and Luckmann (Citation1966) claimed that people socially construct institutions through their communication with each other. Their theory on social construction is rooted in Marx’s proposition that a person’s consciousness is determined by their sociality, which also includes what most people know as reality. Reality, therefore, is socially constructed according to a certain process. This process depends especially on language, which allows the individual to objectify and typify a subjective experience, to transcend the here-and-now, and to build up meanings and a social stock of knowledge that can be distributed and passed from generation to generation (Higgins and Ballard Citation2000).

All human activity is prone to becoming habitual. Institutionalisation exists in the initial stage of every social situation that takes place in time. Repeated actions often turn into patterns that are perceived as definitive patterns or ‘the way we do it.’ Creating institutions is beneficial. Norms enable us to save energy when we perform actions. The number of options related to certain actions is reduced through institutionalisation, so we do not need to think through every step. Habits replace drives since they constitute human control and specialisation (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966), and institutionalisation takes place when habitual actions are mutually typified. These typifications are available to all members of the social group in question. Institutions typify both individual actors and individual actions and always have a history of which they are a product. An institutional world is experienced as an objective reality. Therefore, we suggest that the rise of a social sub-system can be seen as a social construction that takes place between actors in the field such as policymakers, practitioners, and researchers (Schneider, Hastings, and LaBriola Citation2018).

Institutions simultaneously react to and create their environments (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966). This means that, besides actors’ individual contributions to institutionalisation in education, wider norms in society also affect communication and institutionalisation (Meyer Citation1977; Meyer and Rowan Citation1977). Neo-institutional theory explains how ideas travel and are received and translated into the institutional landscape (Meyer Citation2006). Institutional theorists have built new theories and arguments about the wider social conditions that affect and support such systems of actors in reaction to the predominant modern social theory that depicts society as being made up of autonomous and purposeful individual, organised actors (Meyer Citation2010). However, neo-institutional theory is seldom seen as a framework that connects to inclusion in education and it is not a pronounced theoretical perspective for researchers who study teachers’ professional development (Ramberg Citation2014) or comparative international education (Wiseman and Chase-Mayoral Citation2014). Nevertheless, neo-institutional theory recognises that the way we conduct inclusive education is influenced by organisations, ideas, and society in general.

The educational system is governed by various types of policies and controls that focus on inclusion in education. However, several researchers have revealed that formal organisations are often loosely coupled (Hawkins and James Citation2018) and structural elements are only loosely linked to each other and activities and rules; formal structures are generally constantly violated (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977)

Modern organisations are often complex and differentiated (Luhmann and Rasch Citation2002), which increases their need for coordination. Formally, coordinated work is considered to have competitive advantages since rationalised formal structures tend to develop within organisations (Brunsson Citation2014). For example, schools frequently work with several school development projects that are described and implemented by an organisation and are supposed to help establish common strategies and practices (Rapp Citation2018). This coordination tries to simplify, rationalise, control and legitimise the organisation’s logic. By sorting all complex tasks and trying to maintain a standardised and function-driven organisation with mechanical processes, one can (at least on paper) encompass and oversee the complex content of the organisation while meeting the varied demands of the institutional environment (Brunsson and Jacobsson Citation1998; Eriksson-Zetterquist Citation2009). This type of differentiation within the educational system might aid in the construction of several inclusive and exclusive programs and institutionalised practices (Rapp Citation2018). A known example of this is the educational system’s exams. Conflicting pressure is exerted on teachers’ pedagogical approaches when it comes to inclusion. A teacher must relate to the curriculum and individual students while simultaneously timing an expected exam. The exam formally excludes individuals because each student will either fail or succeed in taking the exam (Florian Citation2009).

Both individuals and other actors in the educational system, as well as the wider norms and ideas in society, guide institutionalised communication (Cornelissen et al. Citation2015). Therefore, institutionalisation (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966) can be perceived as the first form of a system. In other words, people construct systems using communication that relates to norms and policies. Communication shapes institutionalised norms over time. In terms of inclusion and exclusion, this shaping can be seen in systems that feature binary codes that determine whether someone is inside or outside the system. Therefore, inclusion and exclusion happen many times and in several ways in the educational system. Moreover, they occur frequently and in varied ways during each school day.

Concepts and theoretical model

The theories presented previously are all broad theories. In the theoretical model, specific concepts from the system- and social-constructionist theories will be addressed.

The concept of the social system is meaningful for investigating how inclusion and exclusion in education occur. A social system is created through social communication. Communication consists of information, messages, and understanding and is performed through linguistic and physical actions. Once a system is created, it communicates meaning. Meaning acts as the internal node around which communication in the system is centred, and it defines what types of communication and ideas are included in the system and what types are excluded. For example, activity in a classroom can communicate many different meanings and, therefore, consist of many different social sub-systems.

The environment puts pressure on a system by asking it to include different types of meaning. Because a system is built on a particular meaning, it cannot incorporate contradictions. Therefore, the system reacts by ignoring the pressure or differentiating into several sub-systems, which again strengthens the argument that educational systems consist of many social sub-systems. Moreover, the concept of socially constructed reality is important. This concept maintains that social interactions between human beings create norms and institutions that later on are a part of the further construction of reality.

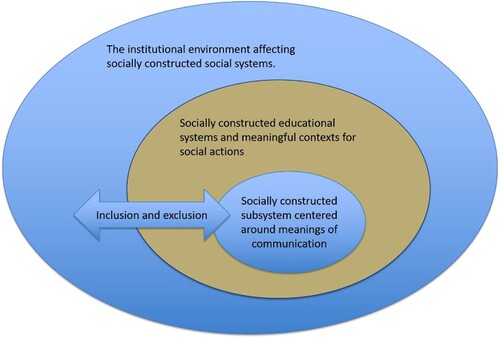

We suggest that social systems are socially constructed not only by human beings but also by norms and institutions such as laws, policies or general popular opinions. The latter understanding stems from neo-institutional theory, which maintains that ideas travel and are translated into educational systems, objectified into various types of policies, and are used to focus on inclusion in education. Formal institutions are often loosely coupled, and structural elements are loosely linked to each other. Talk, decisions and act is not always in line with the institutional rules; formal structures are constantly violated. In conjunction with inclusion, the social construction of institutions can appear on different levels. Hence, institutionalisation is not only a construction made by individuals who interact with each other but is also a process that depends on society ().

Figure 1. This theoretical model illustrates the concepts and how they operate in reality, as well as how to use them to inform research on inclusive education.

In the background of the presented theoretical frame, an empirical question concerning what type of social systems (and sub-systems) create inclusion and exclusion is presented. The question is relevant since sub-systems also depend on society, context, culture, schools, and groups of children. For example, a student who has an injury that prevents them from taking part in physical activities would be excluded from sport-related communication but included in communication about injuries. That type of exclusion sometimes also leads to social exclusion (Rapp Citation2006).

Discussion

The school is often called an institution (Berg Citation2007; Tyler Citation2011), and it has many functions. It is also obligated to ensure inclusive education (Corbett Citation1999). However, researchers have demonstrated that the opposite often happens: the institution creates exclusion.

In the theoretical framework, we introduced a model that addresses inclusion as the opposite of exclusion, which is a continually ongoing process that is constructed through communication at different institutional and organisational levels and creates gaps between policy and practice. Some of the following examples illustrate the use of our model.

First, we would like to explain that inclusion and exclusion in education are driven not only by the educational system but also by other systems at the societal level. Using our theoretical understanding on a macro level, one can see that the educational system is challenged not only by marginalised policies (Camilleri-Cassar Citation2014) and the neo-liberalisation of education but also by other systems like housing. In Nordic education, for example, local schools together with a free choice of schools were meant to support equity and inclusion. Although the educational system is coherent and built on meaningful communication, it is challenged by its environment because it is linked to housing, resulting in urban segregation (Musterd and Ostendorf Citation2013).

Second, educational support systems that relate to special education, healthcare and social services do not operate at the school level but instead operate at the municipal level. Because of that, the schools need to handle the pressure that is placed on the system. As our theoretical model suggests, most schools accomplish this by ignoring the pressure or by differentiating into several sub-systems (Luhmann Citation1995). We can examine how this works by examining how schools handle bullying. Ignoring bullying in a specific class is not an option because this would involve breaking the law. As explained by Rapp (Citation2018), the school as a social system differentiates into social sub-systems by implementing many programs that are supposed to help the school meet challenges and offset pressure in the environment. Problems arise when the school as an organisation loses control of how the implemented program works in relation to inclusion and exclusion.

Third, the theoretical model is useful for understanding what happens in a specific classroom. Communication is a constant ongoing phenomenon in social interaction. During a lesson in a specific classroom, several interactions and communications occur at the same time. Because inclusion and exclusion are connected to systems of communication (Luhmann Citation1995; Luhmann Citation1977; Vanderstraeten Citation2004), the people in the classroom constantly create systems that include and exclude the students (Burkholder, Sims, and Killen Citation2019). For example, some students might discuss their common leisure activities but might dismiss a conversation with another student because they do not engage in the same activity. Additionally, during a specific math lesson, some students might be unable to follow their teacher’s instructions because the level is difficult for them to understand. This does not mean that the teacher is not inclusive, nor does it mean that math is exclusive; it means that this teacher’s specific way of communicating excludes some students from participation. Every minute and every day, we create communication that is inclusive or exclusive for different people (Hilt Citation2017). This example highlights the importance of creating and using tools to study the different social systems that are constructed in the classroom and what they actually communicate.

When considering Berger and Luckmann’s theory, we can assume that several institutionalisation processes take place simultaneously within schools. When considering inclusion and exclusion, one could assume that some of the institutions created through the communication between different actors in the educational system could be inclusive and that some of them could be exclusive, particularly within the ability–disability dichotomy (Danforth and Rhodes Citation1997). Aspects such as test culture, homework and parental involvement, in addition to other parts of the school environment, often exclude students with lower socio-economic backgrounds (Ng Citation2003).

This theoretical approach can be used in research on inclusive education. Policy analyses, interviews with educational personnel, and classroom observations can identify meaningful, repetitive communication systems that inclusively and exclusively utilise binary codes. The theoretical perspective could help different actors in the educational system identify and reflect on how they are conversing and what types of communication they are constructing so that they can understand how these are inclusive for some students and exclusive for others.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Cecilia Rapp

Anna Cecilia Rapp is an associate professor in Sociology. Her research focuses on school, organisation, social inequality, inclusion/exclusion, upbringing conditions, school sport and physical activity. She is one of three leaders for the project Childhood, School and Inequality in the Nordic Countries (Unequal Childhood) and she is leading the connected project Nordic Unequal Childhood. Rapp wrote her PhD thesis on the ‘Organization of Social Inequality in School. A Study of Primary Schools’ Institutional Design and Practice in Two Nordic Municipalities’.

Anabel Corral-Granados

Anabel Corral is a postdoctoral research fellow engaged in the ‘Childhood, School and Inequality in the Nordic Countries (Unequal Childhood)’ project of the Department of Teacher Education (NTNU). In her PhD thesis from Anglia Ruskin University (UK), she explored conceptualisations of inclusion as well as understanding and implementation of inclusive ways to teach children with disabilities. She has in-depth competence in organisational theories, policy analysis and inclusive teaching. She has experience as a researcher at The European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education in both Brussels (Belgium) and Odense (Denmark). Corral has worked as an associate professor at the State University of Alicante, where she coordinated three different subjects on educational psychology and taught on children’s rights; educational psychology and international policy in education.

References

- Aasland, A., and T. Fløtten. 2010. “Ethnicity and Social Exclusion in Estonia and Latvia.” Europe-Asia Studies 53 (7): 1023–1049. doi:10.1080/09668130120085029.

- Ainscow, M., and S. Miles. 2008. “Making Education for All Inclusive: Where Next?” Prospects 38 (1): 15–34.

- Ainscow, M., and A. Sandill. 2010. “Developing Inclusive Education Systems: the Role of Organisational Cultures and Leadership.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (4): 401–416.

- Ainscow, M., R. Slee, and M. Best. 2019. “The Salamanca Statement: 25 Years on.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (7-8): 671–676.

- Amin, S. 2019. “Diversity Enforces Social Exclusion: Does Exclusion Never Cease?” Journal of Social Inclusion 10: 1.

- Armstrong, F. 2019. Social Constructivism and Action Research. Action Research for Inclusive Education: Participation and demoCracy in Teaching and Learning, 5.

- Azorín, C., and M. Ainscow. 2020. “Guiding Schools on Their Journey Towards Inclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (1): 58–76.

- Baraldi, C., and G. Corsi. 2017. Niklas Luhmann, Education as a Social System. 1–4. London: Springer.

- Berg, G. 2007. “From Structural Dilemmas to Institutional Imperatives: a Descriptive Theory of the School as an Institution and of School Organizations.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 39 (5): 577–596.

- Berger, P. L., and T. Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Penguin UK.

- Booth, T. 2018. “Mapping Inclusion and Exclusion: Concepts for all?” In Towards Inclusive Schools?, edited by C Clark, A Dyson, and A Millward, 96–108. London & New York: Routledge.

- Bricker, D. 1995. “The Challenge of Inclusion.” Journal of Early Intervention 19 (3): 179–194.

- Bricker, D. 2000. “Inclusion: How the Scene has Changed.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 20 (1): 14–19.

- Brunsson, N. 2014. “The Irrational Organization: Irrationality as a Basis for Organizational Action and Change.” M@ n@ Gement 17 (2): 141.

- Brunsson, N., and B. Jacobsson. 1998. Standardisering. Stockholm: Nerenius & Santérus.

- Brusling, C., and B. Pepin. 2003. Inclusion in Schools: Who is in Need of What? In. London: SAGE Publications Sage UK.

- Burkholder, A. R., R. N. Sims, and M. Killen. 2019. “Inclusion and Exclusion. Social Development in Adolescence Peer Relationships.” In The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development, 1–9. doi:10.1002/9781119171492.wecad401.

- Burner, T., T. S. Nodeland, and Å Aamaas. 2018. Critical Perspectives on Perceptions and Practices of Diversity in Education.

- Camilleri-Cassar, F. 2014. “Education Strategies for Social Inclusion or Marginalising the Marginalised?” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (2): 252–268.

- Carrington, S., B. Saggers, A. Webster, K. Harper-Hill, and J. Nickerson. 2020. “What Universal Design for Learning Principles, Guidelines, and Checkpoints are Evident in Educators’ Descriptions of Their Practice When Supporting Students on the Autism Spectrum?” International Journal of Educational Research 102: 101583.

- Caspersen, J., T. Buland, I. H. Hermstad, and M. Røe. 2020. På vei mot Inkludering? Sluttrapport fra evalueringen av modellutprøvingen Inkludering på alvor. Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning Mangfold og inkludering.

- Caspersen, J., J. C. Smeby, and P. Olaf Aamodt. 2017. “Measuring Learning Outcomes.” European Journal of Education 52 (1): 20–30.

- Corbett, J. 1999. “Inclusive Education and School Culture.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 3 (1): 53–61.

- Cornelissen, J. P., R. Durand, P. C. Fiss, J. C. Lammers, and E. Vaara. 2015. “Putting Communication Front and Center in Institutional Theory and Analysis.” Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor 40 (1): 10–27.

- Danforth, S., and W. C. Rhodes. 1997. “Deconstructing Disability: A Philosophy for Inclusion.” Remedial and Special Education 18 (6): 357–366.

- Devarakonda, C., and L. Powlay. 2016. “Diversity and Inclusion.” In A Guide to Early Years and Primary Teaching, edited by D Wyse and S Rogers, 185–204. London: Sage.

- Dockar-Drysdale, B. E. 1966. “The Provision of Primary Experience in a Therapeutic School.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 7 (3-4): 263–275.

- Dudley-Marling, C., and M. B. Burns. 2014. “Two Perspectives on Inclusion in the United States.” Global Education Review 1 (1): 14–31.

- Eklund, K., H. Berggren, L. Trägårdh, K. Persson, and B. Hedvall. 2012. The Nordic Way - Equality, Individuality and Social Trust.

- Ekstrom, I. 1970. Proceedings of the First International Seminar of Special Education and Rehabilitation of the Mentally Retarded (Malmo, Sweden, September 17–21, 1970).

- Emmerich, M. 2020. “Inclusion/Exclusion: Educational Closure and Social Differentiation in World Society.” European Educational Research Journal 1–15. doi:10.1177/1474904120978118.

- Eriksson-Zetterquist, U. 2009. Institutionell teori - idéer, moden, förändring. Malmö: Liber AB.

- Ewing, A. 1962. “Research on the Educational Treatment of Deafness.” Educational Research 4 (2): 100–114.

- Fasting, R., R. S. Hausstätter, and A. Turmo. 2011. “Inkludering og Tilpasset Opplæring for de Utvalgte?” Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift 95 (02): 85–90.

- Felder, F. 2018. “The Value of Inclusion.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 52 (1): 54–70.

- Florian, L. 2009. “Towards Inclusive Pedagogy.” In Psychology for Inclusive Education: New Directions in Theory and Practice, edited by P. Hick, R. Kershner, and P. Farrell, 38–51. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Florian, L., K. Young, and M. Rouse. 2010. “Preparing Teachers for Inclusive and Diverse Educational Environments: Studying Curricular Reform in an Initial Teacher Education Course.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (7): 709–722.

- Forlin, C. 2010. “Developing and Implementing Quality Inclusive Education in Hong Kong: Implications for Teacher Education.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 10: 177–184.

- Goodwin, A. L. 2012. Assessment for Equity and Inclusion: Embracing all our Children. New York: Routledge.

- Göransson, K., and C. Nilholm. 2014. “Conceptual Diversities and Empirical Shortcomings–a Critical Analysis of Research on Inclusive Education.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 29 (3): 265–280.

- Gran, B. K. 2017. “An International Framework of Children's Rights.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 13 (1): 79–100. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110615-084638.

- Halinen, I., and R. Järvinen. 2008. “Towards Inclusive Education: the Case of Finland.” Prospects 38 (1): 77–97.

- Haug, P. 2016. “Understanding Inclusive Education: Ideals and Reality.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 19 (3): 206–217. doi:10.1080/15017419.2016.1224778.

- Hawkins, M., and C. James. 2018. “Developing a Perspective on Schools as Complex, Evolving, Loosely Linking Systems.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 46 (5): 729–748.

- Hernández-Torrano, D., M. Somerton, and J. Helmer. 2020. “Mapping Research on Inclusive Education Since Salamanca Statement: a Bibliometric Review of the Literature Over 25 Years.” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–20. doi:10.1080/13603116.2020.1747555.

- Higgins, N., and K. Ballard. 2000. “Like Everybody Else? What Seven New Zealand Adults Learned About Blindness from the Education System.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 4 (2): 163–178.

- Hilt, L. T. 2017. “Education Without a Shared Language: Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion in Norwegian Introductory Classes for Newly Arrived Minority Language Students.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (6): 585–601.

- Hymel, S., and J. Katz. 2019. “Designing Classrooms for Diversity: Fostering Social Inclusion.” Educational Psychologist 54 (4): 331–339. doi:10.1080/00461520.2019.1652098.

- Jamero, J. L. F. 2019. “Social Constructivism and Play of Children with Autism for Inclusive Early Childhood.” International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education 11: 2.

- Joy, R., and E. Murphy. 2012. “The Inclusion of Children with Special Educational Needs in an Intensive French as a Second-Language Program: From Theory to Practice.” Canadian Journal of Education 35 (1): 102–119.

- Loreman, T., J. Deppeler, and D. Harvey. 2005. Inclusive Education: A Practical Guide to Supporting Diversity in the Classroom. New York: Psychology Press.

- Luhmann, N. 1977. “Differentiation of Society.” Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie 2 (1): 29–53.

- Luhmann, N. 1995. Social Systems. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Luhmann, N., and W. Rasch. 2002. Theories of Distinction: Redescribing the Descriptions of Modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Lundahl, L. 2016. “Equality, Inclusion and Marketization of Nordic Education: Introductory Notes.” Research in Comparative and International Education 11 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1177/1745499916631059.

- Mallory, B. L., and R. S. New. 1994. “Social Constructivist Theory and Principles of Inclusion: Challenges for Early Childhood Special Education.” The Journal of Special Education 28 (3): 322–337.

- McAnelly, K., and M. Gaffney. 2019. “Rights, Inclusion and Citizenship: a Good News Story About Learning in the Early Years.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (10): 1081–1094.

- Meyer, J. W. 1977. “The Effects of Education as an Institution.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (1): 55–77.

- Meyer, R. E. 2006. “Review Essay: Visiting Relatives: Current Developments in the new Sociology of Knowledge.” Organization 13 (5): 725–738.

- Meyer, J. W. 2010. “World Society, Institutional Theories, and the Actor.” Annual Review of Sociology 36: 1–20.

- Meyer, J. W., and B. Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–363.

- Musterd, S., and W. Ostendorf. 2013. Urban Segregation and the Welfare State: Inequality and Exclusion in Western Cities. London: Routledge.

- Nevøy, A., and S. E. Ohna. 2014. Spesialundervisning–bilder fra skole-Norge: en studie av spesialundervisnings dynamikk i grunnopplæringen.

- Ng, R. 2003. “Toward an Integrative Approach to Equity in Education.” In Pedagogies of Difference: Rethinking Education for Social Change, edited by P. P. Trifonas, 206–219. New York: Routlege.

- Nilholm, C., and K. Göransson. 2017. “What is Meant by Inclusion? An Analysis of European and North American Journal Articles with High Impact.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 32 (3): 437–451.

- Nutbrown, C., and P. Clough. 2009. “Citizenship and Inclusion in the Early Years: Understanding and Responding to Children’s Perspectives on ‘Belonging’.” International Journal of Early Years Education 17 (3): 191–206.

- O’Flanagan, H. 1960. “Resettlement of the Disabled in Britain.” Irish Journal of Medical Science 36 (2): 70–86.

- Popay, J. 2010. Understanding and Tackling Social Exclusion. London, England: SAGE Publications Sage UK.

- Qvortrup, A., and L. Qvortrup. 2018. “Inclusion: Dimensions of Inclusion in Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 22 (7): 803–817.

- Ramberg, M. R. 2014. “Teacher Change in an era of neo-Liberal Policies: a neo-Institutional Analysis of Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Professional Change.” European Educational Research Journal 13 (3): 360–379.

- Randel, A. E., B. M. Galvin, L. M. Shore, K. H. Ehrhart, B. G. Chung, M. A. Dean, and U. Kedharnath. 2018. “Inclusive Leadership: Realizing Positive Outcomes Through Belongingness and Being Valued for Uniqueness.” Human Resource Management Review 28 (2): 190–203.

- Rapp, A. C. 2006. Mitt i Steget mellan talang och elit. Trondheim: Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet.

- Rapp, A. C. 2018. Organisering av social ojämlikhet i skolan. En studie av barnskolors institutionella utformning och praktik i två nordiska kommuner. Trondheim: Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet.

- Rawal, N. 2008. “Social Inclusion and Exclusion: A Review.” Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 2: 161–180.

- Ritzer, G. 2000. Sociology Theory. Singapore: McGraw-Hill.

- Sahlin, K., and L. Wedlin. 2008. “Circulating Ideas: Imitation, Translation and Editing.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, edited by R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, and R. Suddaby. London: Sage.

- Schneider, D., O. P. Hastings, and J. LaBriola. 2018. “Income Inequality and Class Divides in Parental Investments.” American Sociological Review 83 (3): 475–507. doi:10.1177/0003122418772034.

- Sempowicz, T., J. Howard, M. Tambyah, and S. Carrington. 2018. “Identifying Obstacles and Opportunities for Inclusion in the School Curriculum for Children Adopted from Overseas: Developmental and Social Constructionist Perspectives.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 22 (6): 606–621.

- Shaeffer, S. 2019. “Inclusive Education: a Prerequisite for Equity and Social Justice.” Asia Pacific Education Review 20 (2): 181–192.

- Shawer, S. F. 2017. “Teacher-driven Curriculum Development at the Classroom Level: Implications for Curriculum, Pedagogy and Teacher Training.” Teaching and Teacher Education 63: 296–313.

- Silver, H. 1994. “Social Exclusion and Social Solidarity: Three Paradigms.” Int'l Lab. Rev 133: 531.

- Sokal, L., and J. Katz. 2017. “Social Emotional Learning and Inclusion in Schools.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.146.

- Solli, K.-A. 2010. Kunnskapsstatus som metodisk tilnærming i forskning om inkludering av barn med nedsatt funksjonsevne i barnehagen-refleksjon om oppsummering av kunnskap.

- Sturm, T. 2019. “Constructing and Addressing Differences in Inclusive Schooling–Comparing Cases from Germany.” Norway and the United States. International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (6): 656–669.

- Syahra, R. 2010. “Eksklusi Sosial: Perspektif Baru Untuk Memahami Deprivasi dan Kemiskinan.” Jurnal Masyarakat dan Budaya 12 (3): 1–34.

- Szumski, G., J. Smogorzewska, and M. Karwowski. 2017. “Academic Achievement of Students Without Special Educational Needs in Inclusive Classrooms: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Research Review 21: 33–54.

- Tyler, W. 2011. School Organisation: A Sociological Perspective (Vol. 201). London: Routledge.

- UNESCO. 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for action on special needs education: Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education; Access and Quality. Salamanca, Spain, 7–10 June 1994.

- UNESCO. 2020. Towards inclusion in education: status, trends and challenges: the UNESCO Salamanca Statement 25 years on.

- Vanderstraeten, R. 2004. “The Social Differentiation of the Educational System.” Sociology 38 (2): 255–272.

- Vanderstraeten, R. 2020. “How Does Education Function?” European Educational Research Journal 1474904120948979.

- Van Mieghem, A., K. Verschueren, K. Petry, and E. Struyf. 2020. “An Analysis of Research on Inclusive Education: a Systematic Search and Meta Review.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (6): 675–689.

- Vislie, L. 2003. “From Integration to Inclusion: Focusing Global Trends and Changes in the Western European Societies.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 18 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1080/0885625082000042294.

- Vislie, L. 2004. “Rammer og rom for en Inkluderende Opplæring.” Spesialpedagogikk 5: 16–21.

- Walker, S., and D. Berthelsen. 2008. “Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder in Early Childhood Education Programs: A Social Constructivist Perspective on Inclusion.” International Journal of Early Childhood 40 (1): 33–51.

- Wallin, J. W. 1966. “Training of the Severely Retarded, Viewed in Historical Perspective.” The Journal of General Psychology 74 (1): 107–127.

- Weiner, H. M. 2003. “Effective Inclusion: Professional Development in the Context of the Classroom.” Teaching Exceptional Children 35 (6): 12–18.

- Westwood, P. 2018. Inclusive and Adaptive Teaching: Meeting the Challenge of Diversity in the Classroom. London: Routledge.

- Wiseman, A. W., and A. Chase-Mayoral. 2014. “Shifting the discourse on neo-institutional theory in comparative and international education.” In Annual review of comparative and international education 2013., edited by A.W. Wiseman and E. Anderson, 99–126. Bingley: Emerald.