ABSTRACT

Educational psychologists face challenging decisions around ethical dilemmas to uphold the rights of all children. Due to finite government resources for supporting all learners, one of the roles of educational psychologists is to apply for this funding on behalf of schools and children. Tensions can emerge when unintended ethical dilemmas arise through decisions that compromise their professional judgement. This paper presents the findings from an exploratory study around educational psychologists’ understandings and concerns around ethical dilemmas they faced within New Zealand over the past 5 years. The study set out to explore how educational psychologists manage the ethical conflicts and inner contradictions within their work. The findings suggest that such pressures could influence evidence-based practice in subtle ways when in the course of decision making, practitioners experienced some form of ethical drift. There is seldom one correct solution across similar situations. Although these practitioners experienced discomfort in their actions they rationalised their decisions based on external forces such as organisational demands or funding formulas. This illustrates the relational, contextual, organisational and personal influences on how and when ‘ethical drift’ occurs.

Introduction

Educational psychologists face difficult, complex and atypical situations in their working lives. Consultation, collaboration and partnership (with children, schools and families, and community) are integral to their work (e.g. Miller and Colebrook Citation2020; Verlenden et al. Citation2020). This includes understanding the child’s culture and views that will bring new understandings and may challenge definitions of what the ‘problem’ is, and what the ‘solution’ might be.

Faced with uncertainty with regard to the ‘right’ decision to make, educational psychologists need to balance the child’s perspectives and enable their rights, while working within a system that holds the key to resources, funding and support for both child and the school. Therefore, educational psychologists inevitably face ethical challenges when making decisions that impact the lives of learners. Such challenges will differ, be context specific, can be unanticipated, and vary in severity. While educational psychologists have a professional Code of Ethics to guide their practice, the day-to-day nuanced dilemmas they face, require sophisticated thinking, and complex problem-solving skills. All educational psychologists are Registered Psychologists and must adhere to the New Zealand Psychologist Board Code of Ethics (Citation2012). This Code is principle based, with four core principles of: respect for the dignity of persons and people; responsible caring; integrity in relationships and social justice; and responsibility to society. It requires professional competencies to balance many decisions and course of actions that could be taken when a dilemma arises. In conjunction with this, educational psychologists need to balance their work-based organisational contexts that have clear policies, guidelines and criteria for resource applications.

As educational psychologists and academics working in the training of educational psychologists we (the authors) experienced practitioners in education (e.g. teachers, educational psychologists, specialist teachers, learning support teachers) who expressed some discomfort in working through ethical dilemmas in practice when supporting children and young people gain resources and funding support for their learning needs. These ethical dilemmas always included options for action, but caused conflict for the practitioners between core values. An ethical dilemma is defined as ‘a situation an individual encounters in the workplace for which there is more than one possible solution, each carrying a strong moral justification. A dilemma requires a person to choose between two alternatives, each of which has some benefits but also some costs’ (Feeney and Freeman Citation1999, 24).

We were curious to learn of the occasions where educators had two or more courses of action each requiring strong moral justification, and the ethical decisions they made with regard to the inclusion of children and young people. The examples that came to our attention included the manipulation of assessment data (i.e. removal of scores if it would detract from success in gaining additional resource), and where a teacher was explicitly asked by a senior manager to ‘curtail’ a child’s learning opportunity before the funding grant was developed and accepted. We heard of children being taken out of school for part of the day if teacher-aide support was reduced, or that the results of a child’s basic mathematics tests, when a second-time attempt removing distracting side material attracted a higher grade, was not accepted by the principal. On almost every occasion the right of the child was weighed against both what was perceived as ‘good’ for the child (by an adult) and what the system would accept. It is at these points that ethical decision making waivered causing tension for practitioners, and at times requiring them to re-calibrate their original position.

These decisions are all based on what is ‘good’ for the child, but each teacher or practitioner was required to weigh up their professional judgement and ethical position to determine what was the ‘right’ thing to do. These decisions also happened in the context of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, Citation1989) which New Zealand signed up to in 1993. The relevance of UNCRC in the daily work of educational psychologists is imperative. As noted by Nastasi and Naser (Citation2020), psychologists working in schools have ‘daily opportunities to advocate for the child’s full range of rights reflected in the Convention’; they give an assessment example that ‘when conducting assessments, they can ensure best interests, nondiscrimination, and child participation’ (33).

The challenge for those working in the best interests of the child is often the structural processes within which they work, that might inadvertently work against the child. The educational psychologist, therefore, often weighs up several possible courses of action taking into account both individual and organisational variables. In our work, we recognised that in determining the action educational psychologists or specialist teachers would subsequently take, these practitioners found they drifted off their ideal course of action to develop an application that would have the best chance of being accepted; a phenomenom known as ethical drift (Kleinman Citation2006).

Similarly, ‘ethical fading’ has been identified as a process where people may adjust their moral compass when competitive pressures ‘prompt the trampling of ethical considerations’ (Chang and Fraser Citation2017). While this may influence the outcome of decisions, educational psychologists do not become either immoral or unjust; rather they shift their positions subtly in the quest for targeted and finite resources and support for children. Chang and Fraser (Citation2017) argue that ethical fading tends to occur when competition is a factor in decision making, and that in the health context, for example, this tends to lead to further inequities and social injustice. When a general discomfort occurs for practitioners between their own, and their professional codes of ethics, and run counter to organisational or resource capture demands, they may make choices they feel obligated to do and that over time become more ‘normalised’. We refer to ethical drift in these instances. Ethical drift involves ‘an incremental deviation from ethical practice that goes unnoticed by individuals who justify the deviations as acceptable and who believe themselves to be maintaining their ethical boundaries. Ethical drift escalates imperceptibly until even major breaches are rationalised as reasonable’ (Kleinman Citation2006, 73).

The New Zealand context

In New Zealand, the rights of all children and young people to attend, belong and participate in their local school are protected through legislation (NZ Education and Training Act Citation2020). Around 99.5% of children with learning support needs attend their local school (New Zealand Government Citation2019). The Ministry of Education (Citation2021) gives meaning to inclusive education when:

all children and young people are engaged and achieve through being present, participating, learning and belonging. It means all learners are welcomed by their local early learning service and school, and are supported to play, learn, contribute and participate in all aspects of life at the school or service.

The number of non-included or excluded children, even for days or partial days in schools, remains a concern for families, educators and professionals working on behalf of these young people (Bevan-Brown Citation2015; Bevan-Brown et al. Citation2015; Kearney Citation2016). However, it is unlawful for schools to impose reduced hours or part-time attendance without a special exemption from the Ministry of Education. There are formal ways that children can be excluded. Clause 80 of the Education and Training Act (Citation2020) enables principals to stand down or suspend students for gross misconduct, continual disobedience or for reasons of safety for others. Suspensions can result in exclusion from the school. Formal exclusion processes disproportionally impact Māori and Pacific students (Bourke, Butler, and O’Neill Citation2021), signalling that cultural attitudes remains a critical issue in New Zealand, as ‘Māori children with special education needs are often being neglected, overlooked, inadequately provided for, and even excluded’ (Bevan-Brown Citation2015, 15).

Educational psychologists typically have psychological, cultural and educational knowledge of children and young people, systems’ level knowledge of the home, social and educational contexts of these children, of learning, assessment, behaviour and development stages. In New Zealand, they have bicultural understandings that are foundational to upholding the Treaty of Waitangi, and critically, knowledge of the rights of the child under UNCRC. The Treaty of Waitangi is a founding document in New Zealand that is the basis for partnership between Māori and Pākeha (NZ Europeans). In education systems, it means the importance of practitioners to understand Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview) including ‘understanding Te Ao Māori values and beliefs’ (Ritchie and Rau Citation2010, 3).

While every child has the right to attend their local school irrespective of need, any additional resource to support their learning, belonging and presence at school requires an application for specific resourcing. Practitioners work within strict criteria to determine these children’s eligibility. This places educational psychologists as ‘gatekeepers’ to resources due to their role in completing the resource applications. Arguably it is through these processes that practitioners encounter ethical dilemmas and potential ethical drift.

UNCRC informs the educational landscape in New Zealand. The Convention outlines 54 Articles that identify the rights of the child across their educational, social, living and political contexts, and clearly positions the child as central to decision making and being involved in matters that affect them directly. Typically for professionals working in education (teachers, psychologists, specialists) this involves finding ways to listen to children and their views, and to understand how to best meet their needs. As Wisby (Citation2011) has argued, these ‘dialogic models of student voice’ can be transformational for young people and are founded on the rights of the child in shared decision making and social inclusion. Increasingly, there is a strong imperative for practitioners to actively uphold the rights of the child, and to listen to the voice of children and young people in both policy and practice across social services and educational agencies internationally (see Nastasi, Hart, and Naser Citation2020). The New Zealand Children’s Commissioner, Judge Andrew Becroft, noted that more individuals, agencies and practitioners in New Zealand were aware of the rights of the child to be heard on matters that affect them: ‘I sense a sea-change in attitudes to consulting with and listening to children’ (Becroft Citation2018, viii).

The Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) affords persons with disabilities the same rights as outlined under the human rights convention and provides ways for societies to overcome barriers people may face to access their rights. The most recent New Zealand Disability Strategy (Citation2016–Citation2026) ensures that people with disabilities are treated fairly, can participate in their community, are able to have control over their lives and lead a meaningful life. These policies and legislation position both the Child’s Rights as a child to live, learn and play, and the right to access education to be educated regardless of need, and to be listened to and have their views acted on.

Educational psychologists in New Zealand

Education is one of the formal Scopes of Practice that psychologists in New Zealand can register under through The New Zealand Psychologists Board (NZPB). The training of educational psychologists emphasises evidence-based practice, ecological or holistic assessment approaches, ethical and culturally competent practice, working collaboratively, using a strength-based approach where the child’s natural abilities and capabilities are used to support an intervention, and facilitation of problem solving to support the wellbeing and inclusion for all children and young people. The Ministry of Education is the main employer of educational psychologists. Their focus is to work collaboratively with families and schools to enact inclusion in education for all children. As noted above, a large part of their role is the completion of resource applications for students who have significant additional needs.

An earlier study on the assessment practices of educational psychologists in New Zealand identified that these practitioners experienced ethical dilemmas in assessment given the context of work they were required to engage in (Bourke and Dharan Citation2015). This mainly arose when they encountered tension between their preferred method of practice (solution focused and ecological models of working) with a requirement to work within a different paradigm from external sources such as the requirement of including psychometric test data (Bourke and Dharan Citation2015). Another ethical issue in assessment involves ‘grade pollution’ which occurs within an assessment context where teachers or specialists may misrepresent a mark or grade to gain additional resources or to protect the child from undue treatment (e.g. see Bourke Citation2017; Ehrich et al. Citation2011; Pope et al. Citation2009).

Understanding the conceptual demands on practitioners

The focus on inclusion and inclusionary practices, and the rights for a child to equity in education, is often explored through the policies and practices of educational institutions and those that work within them. As part of understanding professional practice, educational psychologists must be aware of the conceptual demands that underpin their decisions. This section explores the concepts of moral compass and ethical demands that lead to ethical drift in decision making.

Professionals working in health and education typically use their ‘moral compass’, described as ‘the inner voice that tells us what we should and should not do in various circumstances’ (Moore and Gino Citation2013, 55) to determine the best course of action when ethical dilemmas arise in the workplace. However, when organisational or policy constraints influence what and how they practice, individuals may adjust their practice to ‘fit’ the system or the outcomes they require (e.g. additional resources, funding or equipment). Kleinman (Citation2006) identified how work constraints can compromise practitioners’ values (in a nursing context for example). When there are competing priorities within the workplace (e.g. the managers or clinical directors, versus the professionals) an ‘ethos gap’ may arise; creating a disjuncture between what decisions can be made, and when.

Tensions arise in a professional workplace when ‘the role requires individuals to be consistent and firm for the sake of equity and transparency, whilst common decency and empathy desires flexibility or even unprincipled leniency’ (Hellawell Citation2015, 121, emphasis added). Therefore, while consistency is critical for fair allocation of resources, so too is being flexible around decisions when empathy is required. This is reflected in an authentic example outlined through the present exploratory study in Scenario 1 below. The dilemma between organisational and child’s needs is evidenced across the literature (Hellawell Citation2015; Moore and Gino Citation2013).

When ethical dilemmas are unresolved there is a greater likelihood of ‘burn-out’ and the experience of practitioners identifying organisational shifts from ‘ethics to efficiency’. The ethical gaps that appear slowly but subtly and ones that can be easily rationalised may mean practitioners do not see the incremental steps that lead to the drifting of their espoused ethical stance (Kleinman Citation2006). The gradual ebbing of standards, that occurs without conscious awareness has been likened to a boat floating at sea (Sternberg Citation2012), and where practitioners get to the point ‘where they simply stop questioning their actions’ (Bourke Citation2017, 225). Knapp et al. (Citation2013) referred to the ‘dark side of professional ethics’ and explored the notion that even when psychologists might think they are acting ethically, an evaluation of their behaviour and actions and peer review determine the behaviour to be on the margins of acceptability.

Exploratory study

An online 20-item survey based on three practice-based scenarios was developed. These practice-based scenarios were developed from collective experience between the three researchers and prior discussions with education professionals. All scenarios represented authentic ‘real-world’ tensions and issues expressed by teachers, special education advisors or psychologists, and were designed to highlight the tensions between resource allocation and availability and practice decisions that educational psychologists may encounter in practice.

Educational psychologists were asked to gauge the frequency that they came across, or observed the scenario, using a 4-point Likert scale where participants could indicate – Never, Seldom, Occasionally, and Often. It is typical that Likert scales provide five responses options to choose from, with the optimum number between four and seven response (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2018; Croasmun and Ostrom Citation2011). For this pilot study, we opted for a 4-point scale to enable participants to take an active stance rather than a fall-back position of ‘don’t know’ (Krosnick Citation1991), which can be used by participants as a genuine category and best avoided as ‘the inclusion of this category might compromise the quality of the data and this might apply particularly if sensitive questions are being asked where socially undesirable response categories are included’ (Krosnick and Presser Citation2010, 287).

Although Likert scales are the dominant method used to identify attitudes (Scholderer Citation2011), they have been critiqued for the often context-free nature of the questions (Safrudiannur Citation2020). We felt it appropriate to use this approach on this occasion given the scenarios provided the context for each question. The even-numbered four-point scale also ensured neutral responses would be avoided. Participants were asked if they would support the decision outlined in the scenario. This was done by indicating Yes, No, Dependent on other information around the case. If participants selected the option ‘dependent on other information around the case’, they were then prompted to identify what further information they would want to know. If participants noticed a tension, they were asked to identify the main constraints they could see for their practice, and also to identify what solutions may be helpful. The final question asked participants to briefly outline if they have experienced an ethical dilemma or had to make a decision that left them feeling uncomfortable to access resource or support. This survey was assessed as low risk by Massey University Ethics Committee. Ethics Notification 4000022026.

The survey link was sent to the Institute of Education and Developmental Psychology who circulated to their membership in a regular newsletter (approx. 170 members). The survey was also disseminated to the psychology networks of the researchers, who reached out using personal email addresses and requested this be further passed on throughout their networks.

Responses to scenarios

The following section presents the three scenarios, based on actual practice in the field as reported to us by practitioners who expressed concern at the time that they or their colleagues had needed to enact, and then the participants’ responses to these. Across all scenarios, there is clearly tension between holding a firm ethical position and justifying actions, and being faced with a complicated and multi-faceted set of circumstances, within an organisational versus individual scenario that led them to questioning their original position.

Scenario 1: application for resources

In the first scenario, the educational psychologist is faced with meeting the needs of the child (through gaining additional resources and support) while noting that the slightly higher score in one subtest of the psychometric assessment may jeopardise the application’s success. It becomes a struggle as to whether ‘ethical centred practice’ and indeed we would argue, evidence-based practice, takes priority over ‘ethically defensible practice’. At what point, does the educational psychologist move towards another position of ‘what is right?’ without debating the position, and creates a new normative understanding around decisions of practice.

SCENARIO 1

You have been asked to complete an assessment to support a funding application for a 5-year-old child who has complex needs and has been at school for 2 months without support. Your assessment will be used to inform a school-based application for a specific funding pool that provides targeted resources and support. Although you would not typically use a cognitive assessment early on, after several observations you note the child has complex cognitive delay, and your assessment has implications for the type of resourcing the child will access to support her learning. You complete a cognitive assessment [psychometric test] and find that while the majority of the scores reflect your observations and other assessments of the child in the classroom, there are some areas the child scores higher on. In writing the report, you decide to leave out the higher scores, so that the child’s application will be stronger.

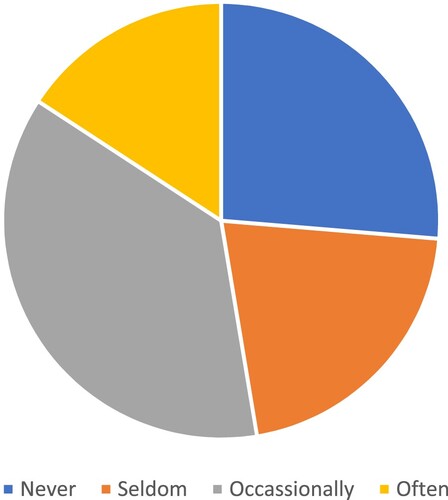

There were 19 respondents to this scenario. Of these, five indicated that they had never come across this situation. Three had ‘often’ come across this, 7 occasionally, and 4 seldom. This suggests that although these practitioners knew of the type of scenario, it was not a common or typical practice to leave out test scores when reporting data (see ), and so have avoided ethical drift in their decision making. Of the 14 that reported this situation does happen in practice, they indicated that they personally would not support the decision. Therefore, this suggests that ethical drift is being recognised in practice.

Although one response gave a definitive stance on the issue ‘I think that biasing a report in that way is not ethical or best practice’ (P6), others took a more nuanced view to the issues underpinning the decision. This suggests that there is a fine line between knowing the right thing to do, and understanding the complex context that may justify an amendment to their original strongly held stance. In general, the psychologists identified that they are aware of this happening but would not support the decision themselves. Participants reported organisational or resourcing constraints that could influence professional decisions. They also commented on the incongruence that resulted between ways of practice (e.g. strength-based) versus the use of data for applying for specific resources (e.g. deficit orientation).

In response to the scenario, several issues were raised by the respondents, and these qualitative responses provided insight into the tensions faced. Therefore although the educational psychologists may not have engaged with the scenario as described, they had experienced the tensions underpinning the example: access to resources, and securing the support for the child. To do this, invariably terms such as ‘deficit-based’, labels, ‘fudge results’ were used when referring to the Ongoing Resourcing Scheme (ORS) which is a contestable funding scheme for students with very high needs. For example, one participant noted:

Access to funding is very difficult, and I have had ORS [Ongoing Resourcing Scheme] applications declined. I want to help children to access services and support, and often that only happens if the applications for said support are as deficit-based as possible. However, I was trained and practice in a strengths-based way which creates tension. (P1)

However, in the systems in which we currently operate in NZ, it is difficult for children to get the amount of support they need without these labels and I've had experience writing ORS [Ongoing Resourcing Scheme] applications in a strengths-based way and having them rejected for one of the strengths of the child. (P2)

Tension between professional ethics and a system that seems to produce imbalanced acceptance. I remain mystified why some students are accepted when others, who appear to me to be more needy, miss out. It doesn’t seem right to ‘fudge’ results in order to get the child the help I thinks/he needs. (P3)

The way the systems are set up to access resourcing require reporting of the child's difficulties much more than their strengths, and it is true that reporting on strengths can cause the child to be seen as not requiring additional support, or not being prioritised. In the case of a cognitive assessment the results should be reported in full and if not, an explanation given in the report as to why some areas are missing. (P14)

I also have strong feelings about a written report from a psychologist being used after the fact by other professionals to justify abdicating responsibility (e.g. he's got such challenges, it's easier for him to just do something in the corner with the teacher's aide). What we write about children can stick to them for a long time. (P1)

I am hesitant doing cognitive assessments in the first place because of the labels that people can apply to children, and sometimes the consequences of teachers or support people believing that they have a cognitive disability and therefore lowering their standards/expectations (or giving their education and oversight over to a Teacher's Aide) which reduces access to quality education for that child. (P2)

From my perspective, I see the tension being that the practitioner has a professional responsibility to accurately represent the data collected and to be honest and transparent in the knowledge that they have. However, in this case, it means that the practitioner has knowledge that may restrict the young person from accessing funding support that might provide them with opportunities that they would otherwise not have access to, and they may benefit from. In addition to this, the pressure from schools and families to create a successful application would also be quite significant. This creates an ethical dilemma. (P5)

Scenario 2: multiple stakeholders

In the second scenario, the educational psychologist is faced with balancing the rights of the child and access to education, with the wider needs of the school, and the maintenance of relationships. Similar to the previous scenario, it looks at key stages when practitioners potentially move away from ‘ethically defensible practice’ to achieve the best outcomes for the child, school and family in this situation.

SCENARIO 2

The school made a recent decision to reduce a student’s attendance to part time due to resourcing constraints. Your professional opinion is that the student should be able to continue with full-time attendance, however, you agree that additional resourcing would support the student to be present and participate full time. This view is shared by the student and their family. Despite this the school has informed the parents that the child must be picked up at lunchtime. You choose not to challenge this as you need to maintain collegial relationships with staff given that you support several other students at the school.

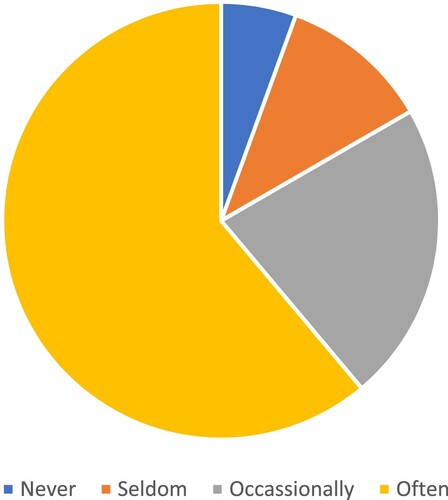

In this scenario, 18 educational psychologists responded and 11 of these participants reported they often came across this scenario. Four participants responded they occasionally came across this, with only two reporting they seldom came across this and one reporting they never have come across this. This shows that educational psychologists do come across the ethical dilemma of supporting the exclusion of a child for part of their day when resources are not available, to maintain the working relationship with the school and other children the educational psychologist supports (i.e. 17 of the 18 responses), and 11 that commonly experience this (see ). Twenty respondents to the next stage of this question showed only 2 practitioners supported the decision outlined in the scenario, with 8 participants indicating they did not support it, and 10 participants reporting their decision would be dependent on other information around the case.

Although the small scale nature of this exploratory study means it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions, it is interesting to note the range of responses from supporting to not supporting the decision within the scenario. This highlights how psychologists vary in their responses to reduced hours for child attendance at school when there is limited resource to support the child being included. Participants who identified they would require additional information before making a decision indicated they would want more information around two key areas: (i) evidence of a transition plan back to full-time attendance and (ii) management of safety (for child, peers and teachers). The complexity that psychologists consider around these situations is represented in the following response:

Does the school intend for this to occur for the duration of the student’s school year or is there a graduated transition plan to get the student back into the classroom? What are the needs of the student and the school’s capabilities to meet these needs? The scenario spoke of additional resourcing being seen as useful but might not be feasible so what else could be put into place? What collegial support the practitioner had with this matter; as the role of advice and guidance can only stretch so far before someone with greater sway would need to be involved. What is the school’s motivation for doing this and what alternatives could be thought of/ have previously been thought of? (P9)

I believe it should be the right for a child and the child's family to engage in education and be supported in whatever ways are needed. (P10)

The tension is that the practitioner’s role is to work collaboratively with BOTH the family and the school, and that the practitioner may have other students in that school that they are supporting which could prove difficult if their relationship with key school staff becomes fractured over this other student. The role of the practitioner (from experience) would be to provide ‘advice and guidance’ to school teams and so verbalising that the student should be attending full time may not make any difference to their actions. The school’s barriers also make it difficult to implement any intervention plans because of limited attendance and the school’s stance on inclusion. (P10)

The student’s legal right to attend school vs knowing the school doesn’t have the resources to cope, and what may result because of this. I think, as psychologists, it is our role to challenge what we see, and have difficult conversations. However, there are solution focused ways to achieve positive outcomes. (P11)

Scenario 3: access to education, without meeting the needs of the child

SCENARIO 3

A student has been referred to you for a psycho-social assessment for enrolment with an online remote school (known in New Zealand as Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu, or ‘Te Kura’ The Correspondence School). Through your assessment, you identify that the home is safe with suitable supervision available. There is a long-term history of non-attendance and anxiety. After discussion with key stakeholders you realise that the option to attend mainstream education is not going to be viable. There is no other obvious way to support this young person and in view of this you recommend enrolment in this school. In your professional opinion, you feel it is not the preferred option and the likelihood of any engagement in learning and accessing support for anxiety and mental health is unlikely. Your rationale for this is that at least the student will no longer be considered truant and will be enrolled in an education facility.

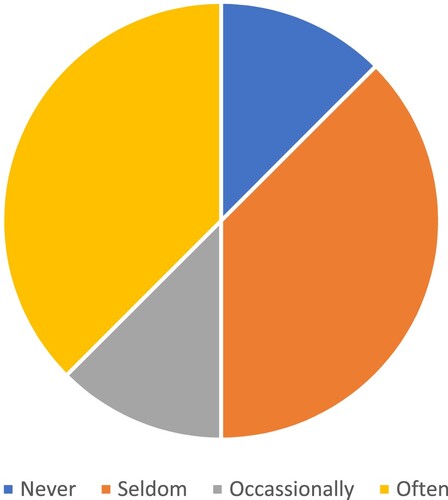

In the third scenario, 14 of the 16 educational psychologists who responded to this question had encountered this situation at some stage over the past 5 years. Six participants reported they often came across this scenario. Two participants responded they occasionally came across this, with six reporting they seldom came across this and two reporting they have never come across this (see ). From these participants’ experiences, this suggests that enrolling children in a correspondence-type or online school situation is being used as a means of access to education while recognising that this is not the best option for the young person’s specific needs. Fifteen responded to the question whether they would support this decision, and from these only two did not support this decision. Nine wanted more information around the circumstances leading to this decision. Respondents reported that further information required would include understanding the risks, community agencies that could be included, possibility of home-schooling, suggested early exemption of suitable age, and whether the student agreed with the decision. In other words, practitioners wanted to know what other agencies or schooling options were available, the voice of the child, and what other options could be explored to meet the needs of the young person (Figure 3).

The responses to this scenario suggest that even the practice of accessing children’s ‘correspondence enrolment’ at a remote learning school (for New Zealand this is the Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu, Correspondence School), potential dilemmas arose because while it ensured the child’s right to education, it was not considered the preferred option for meeting the child’s social, emotional and psychological wellbeing needs. The remote learning school is not the issue for the psychologist, but rather the question being asked is: what social environment would the child, who is often already isolated, thrive in? For educational psychologists, the holistic nature of the child’s rights to education, health and wellbeing, were constantly being juggled.

[These] applications almost always come with ethical dilemmas. Usually a forced-choice scenario where our systems and schooling options fall short of what is needed. It would be great to have some mainstream high school options that had smaller populations, less changes in teacher and room, to allow for better student-teacher relationships and greater consistency, and high schools with particular interest focuses. Usually not recommending [this option as it] would result in less support and isolation as the young person is usually out of school. (P14)

Tension is that sometimes one has to make a decision based on ‘the lesser of the two evils’. On balance, the correspondence school enrolment would at least put the student and work together, and it is then up to the student and whānau [family] to make the efforts needed. School hasn't worked, so education in a different format may be the answer. The work output is monitored by the correspondence school so if things aren't working a rethink may be in order, however, giving it a chance to work would be my approach in the above scenario. I'm sure that school attendance is not the answer, I'm uncertain if [this] will work. Best idea would be to give it a go, and monitor. (P12)

Ethical decision making in practice

Although the educational psychologists recognised the ethical decision making in their practice did at times lead to ethical drift, in general they did not agree the course of action was the ‘right thing to do’. In their explanations and discussions across the survey, it was clear that for many ‘tensions are that issues cannot just be around the child and not seen in isolation’ (P10). The educational psychologists explained how they navigated tensions through a solution focused, strength-based approach and in collaboration with others. As one noted, this required: Open korero [discussion], positive facilitated pathways. Structured and supported for both sides – school and whānau [family] (P3).

The responses demonstrated that psychologists often considered and weighed up multiple solutions, and worked with a range of agencies, and members within a school community, and the child and family. Tensions may arise within the school context, such as between the principal’s view on the course of action, and that of the teacher, or between the teacher and the teacher-aide. Educational psychologists constantly navigated these views and tensions, while always maintaining the rights of the child were central to working through a solution. Across the three scenarios, when faced with ethical dilemmas, psychologists were always looking for other options to consider, resources that were available. They needed the skills to navigate the system within which they worked, and accessed their knowledge of multiple sources of resources, and across agencies.

Responses reflected the significance and weight on the educational psychologist’s own wellbeing, when making decisions or when supporting others to make a decision. They also took on more responsibility for their actions, for example, some psychologists appeared to take responsibility for the child’s attendance at school, despite not being the key stakeholder in such a decision. They felt an accountability towards the actions of those around the child, and wanted to both contribute into, and hold to account, the team who was responsible for the decisions that impacted on the child. Working across systems is part of this approach, and educational psychologists throughout their responses indicated how they attempted to mitigate any issues.

Solutions generated by the respondents indicated the large amount of background work the psychologist undertakes to enable solutions to occur. This suggests that as psychologists do not feel comfortable with reduced hours, they work to mitigate this while maintaining relationships with all parties as best as possible, while at the same time recognising the complexity of the layers of systems they work within:

In my personal experience I have had to accept that ingrained culture takes time and is a big process to change. The best I can do is continue advising and encouraging the schools to look at building up students’ time at school where they are independent - without a TA [teacher-aide] and reminding them that I can support the teacher with strategies and use of other resources. If the parents are unhappy with the school's choice I would probably be more vocal and push to look for a compromise. I have often found senior management staff are on the same page as me around this but it also takes time for them to change a culture where teachers and parents have become reliant on 1:1 TA time for students, particularly as this is often used more like a babysitting service and relieves teachers of responsibility. (P6)

If I believe the child would better benefit from being at school full-time, I would represent that idea to the school, in a nice way so that I am not being antagonistic, but I will be positively assertive to represent the child's needs. If more resources are required to meet these I would advocate for these resources. There are many unused pots of funding within the Ministry of Education and within the school, and sometimes one needs to think outside the box to meet the needs of the child and placate the system at the same time. (P9)

I tend to remind schools of the UNCRC rights of the child to full time education. I also ask schools for how long this plan is going to be in place for, and given the child's right to full time education, what's their plan for increasing the time again, and when do they plan on doing that. I ask them what skills they feel the child needs to be able to be in the classroom, and then ask them how they’re going to teach the child those skills as part of their curriculum. (P4)

Until clear landmarks are identified, practitioners may not even be aware they have gone ‘off course’ ethically or morally. In part this is because they attempt to justify their choices to create a balance of moral stability, but also because the organisational constraints create a culture of just getting on with it – there are targets to meet, outcomes to be delivered, and financial resources are tight. Subtle compromises may result in the evidence-based practice environment of (i) using best evidence in research, (ii) the practitioner’s expertise and knowledge, and (iii) the young person’s cultural and social context and their right to form and provide their views.

Ingram (Citation2013) reported on the ethical challenges faced by educational psychologists when they include children’s views in reports. For example, if a child reports something negative about a teacher, would this view be included in a report or in a meeting with the child and teacher, or would the child’s views be sanitised? This may occur in part to ensure their safety, but perhaps also because children’s views are re-interpreted by the psychologist who makes decisions about what aspect of the child’s voice is to be heard. This is an interesting dilemma, given UNCRC Article 12 clearly stipulates the rights of the child to be heard, but professionals may determine ‘what aspect of their voice’ will be represented to be heard. This phenomenom of ethical drift has also been documented in research with children (Enochsson and Hultman Citation2019).

Conclusion

There is a fine, almost imperceptible line for the practitioner working through an ethical dilemma, and the ethical drift that arises through this process. By taking into account, the child’s rights and needs, the context, the resources, the assessment and intervention, and colleagial supervision required of a psychologist, the nuanced ‘what is the right decision to make?’ can shift subtly depending on what aspect is taken to the fore. After decades of children being given free and fair access to attend their local school, the context within which their education and learning take place is far from clear. When placement in classrooms does not guarantee inclusion and belonging, when assessment practices may be neither culturally neutral nor fair, and when educational psychologists are bound by the constraints of organisational parameters, these issues will continue. As identified by Shriberg, Brooks, and de Oca (Citation2020), ‘the ethical issue of acquiescence, which … is giving in to systemic pressure that is not in the best interest of the student.’ (46) is a very real scenario faced by educational psychologists.

Therefore, it is critical that contentious ethical dilemmas, and the situations that arise to create these for organisations and individuals, are ‘aired’. Ethical dilemmas and the subsequent decisions that create inner conflict are often not articulated with colleagues so there is critical importance that there are discussions around these to learn from them and create solutions to support the resolution of these (e.g. Biesta Citation2009). Key strategies to address ethical drift in decision making include reflect, review and reconsider (Kleinman Citation2006). Supporting ethical decision-making processes and developing competencies to work within a principle-based Code of Ethics means sharing dilemmas with others, and educating colleagues about specific issues (Ehrich et al. Citation2011); this paper opens the conversation of an area that is an authentic and real challenge for many professionals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Roseanna Bourke

Dr. Roseanna Bourke is a Professor of Learning and Assessment at Massey University. She is a registered psychologist, and the Director of the Educational and Developmental Psychology programme. She researches in the areas of learning, informal learning, student voice, Child Rights and assessment.

Ros Pullen

Ros Pullen is a registered educational psychologist and is Senior Professional Clinician for the Massey University Educational and Developmental Psychology Internship programme. Her professional interests include training and teaching in educational psychology, intern and professional supervision, assessment, ethics and professional practice.

Nicole Mincher

Nicole Mincher is a registered educational psychologist and lecturer at Massey University. Her research interests include educational psychology practice, equity in education and school disciplinary processes.

References

- Becroft, Andrew. 2018. “Foreward.” In Radical Collegiality through Student Voice. Educational Experience, Policy and Practice, edited by Roseanna Bourke, and Judith Loveridge, i–xii. Singapore: Springer.

- Bevan-Brown, Jill. 2015. “Introduction.” In Working with Māori Children with Special Education Needs: He Mahi Whakahirahira, 3–30. NZCER Press.

- Bevan-Brown, Jill, Mere Berryman, Huhana Hickey, Sonia Macfarlane, Kirsten Smiler, and Tai Walker. 2015. Working with Māori Children with Special Education Needs: He Mahi Whakahirahira. NZCER Press.

- Biesta, Gert. 2009. “Values and Ideals in Teachers’ Professional Judgment.” In Changing Teacher Profesisonalism: International Trends, Challenges and Ways Forward, edited by Sharon Gewirtz, Pat Mahony, Ian Hextall, and Alan Cribb, 184–193. London: Routledge.

- Bourke, Roseanna. 2017. “Untangling Optical Illusions: The Moral Dilemmas and Ethics in Assessment Practices for Inclusive Education.” In Ethics, Equity and Inclusive Education, edited by Agnes Gajewskim, and Chris Forlin, 215–238. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Bourke, Roseanna, Philippa Butler, and John O’Neill. 2021. Students with Additional Needs. Final Report to the NZEI, PPTA and Ministry of Education Accord. Unpublished report.

- Bourke, Roseanna, and Vijaya Dharan. 2015. “Assessment Practices of Educational Psychologists in Aotearoa/New Zealand: From Diagnostic to Dialogic Ways of Working.” Educational Psychology in Practice 31 (4): 369–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2015.1070709.

- Chang, Wei-Ching, and Joy Fraser. 2017. “Cooperate! A Paradigm Shift for Health Equity.” International Journal for Equity in Health 16: 12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0508-4.

- Lawrence, Louis Manion, and Keith Morrison. 2018. Research Methods in Education (8th ed.). London: Routledge Falmer.

- Croasmun, James, and Lee Ostrom. 2011. “Using Likert-Type Scales in the Social Sciences.” Journal of Adult Education 40 (1): 19–22.

- Education and Training Act. 2020. (New Zealand) https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2020/0038/latest/whole.html.

- Ehrich, Lisa, Megan Kimber, Jan Millwater, and Neil Cranston. 2011. “Ethical Dilemmas: A Model to Understand Teacher Practice.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 2: 173–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.539794.

- Enochsson, Ann-Britt, and Annica Löfdahl Hultman. 2019. “Ethical Issues in Child Research: Caution of Ethical Drift.” In Challenging Democracy in Early Childhood Education, Engagement in Changing Global Contexts, edited by Valerie Margrain, and Annica Löfdahl Hultman, 27–39. Singapore: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7771-6.

- Feeney, Stephanie, and Nancy Freeman. 1999. Ethics and the Early Childhood Educator Using the NAEYC Code. Washington: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Hellawell, Beate. 2015. “Ethical Accountability and Routine Moral Stress in Special Educational Needs Professionals.” Management in Education 31 (3): 119–124. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020615584106.

- Ingram, Rachel. 2013. “Interpretation of Children’s Views by Educational Psychologists: Dilemmas and Solutions.” Educational Psychology in Practice: Theory, Research and Practice in Educational Psychology 29 (4): 335–346. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2013.841127.

- Kearney, Alison. 2016. “The Right to Education: What is Happening for Disabled Students in New Zealand?” Disability Studies Quarterly 36: 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v36i1.4278.

- Kleinman, Carole. S. 2006. “Ethical Drift. When Good People Do Bad Things.” JONA’S Healthcare Law, Ethics, and Regulation 8 (3): 72–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00128488-200607000-00004.

- Knapp, Samuel, Mitchell Handelsman, Michael Gottlieb, and Leon VandeCreek. 2013. “The Dark Side of Professional Ethics.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 44 (6): 371–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035110.

- Krosnick, Jon. A. 1991. “Response Strategies for Coping with the Cognitive Demands of Attitude Measurement in Surveys.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 5 (3): 213–236.

- Krosnick, Jon. A., and Stanley Presser. 2010. “Questionnaire Design.” In Handbook of Survey Research (Second Edition), edited by J. D. Wright, and P. V. Marsden. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

- Miller, Gloria, and Jessica Colebrook. 2020. “The Promotion of Family Support.” In International Handbook on Child Rights and School Psychology, edited by Bonnie K. Nastasi, Stuart N. Hart, and Shereen C. Naser, 361–376. Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Ministry of Education. 2021. Inclusive Education. https://www.education.govt.nz/school/student-support/inclusive-education/#sh-inclusive%20education.

- Moore, Celia, and Francesca Gino. 2013. “Ethically Adrift: How Others Pull our Moral Compass from True North, and How We Can fix it.” Research in Organizational Behavior 33: 53–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2013.08.001.

- Nastasi, Bonnie, Stuart N Hart, and Shereen Naser. 2020. International Handbook on Child Rights and School Psychology. Switzerland: Springer.

- Nastasi, Bonnie, and Shereen Naser. 2020. “Conceptual Foundations for School Psychology and Child Rights Advocacy.” In International Handbook on Child Rights and School Psychology, edited by Bonnie Nastasi, Stuart Hart, and Shereen Naser, 25–36. Switzerland: Springer.

- New Zealand Disability Strategy. 2016-2026. https://www.odi.govt.nz/nz-disability-strategy/about-the-strategy/new-zealand-disability-strategy-2016-2026/read-the-new-disability-strategy/.

- New Zealand Government. 2019. Korero Matauranga: Learning Support Action Plan 2019-2025. Retrieved from https://conversation.education.govt.nz/assets/DLSAP/Learning-Support-Action-Plan-2019-to-2025-English-V2.pdf.

- New Zealand Psychologists Board. 2012. Code of Ethics for Psychologists Working in Aotearoa/New Zealand. https://www.nzccp.co.nz/assets/Uploads/Code-of-Ethics-English.pdf.

- Pope, Nakia, Susan Green, Robert Johnson, and Mark Mitchelle. 2009. “Examining Teacher Ethical Dilemmas in Classroom Assessment.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (5): 778–782. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.11.013.

- Ritchie, Jenny, and Cheryl Rau. 2010. “Poipoia te Tamaiti kia tū Tangata: Identity, Belonging and Transition.” First Years/Ngā Tau Tuatahi 12 (1): 16–22.

- Rutherford, Gill. 2012. “In, out or Somewhere in Between? Disabled Students’ and Teacher Aides’ Experiences of School.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 16 (8): 757–774. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2010.509818.

- Rutherford, Gill. 2021. “Teacher Education: Doing Justice to UNCRPD Article 24?.” International Journal of Inclusive Education. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1882054.

- Safrudiannur, S. 2020. Measuring Teachers’ Beliefs Quantitatively. Criticizing the Use of Likert Scale and Offering a New Approach. Springer Spektrum. https://doi-org.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-30023-4.

- Scholderer, Joachim. 2011. “Attitude Surveys.” In Encylopedia of Consumer Culture, edited by Dale Southerton, 70–71. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Shriberg, David, Keeshawna Brooks, and Jessie Montes de Oca. 2020. “Child Rights, Social Justice, and Professional Ethics.” In International Handbook on Child Rights and School Psychology, edited by Bonnie Nastasi, Stuart Hart, and Shereen Naser, 37–48. Switzerland: Springer.

- Sternberg, Robert. 2012. “Ethical Drift.” Liberal Education 98 (3): 58–60.

- United Nations. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/4aa76b319.pdf.

- Verlenden, Jorge, V. Emiliya Adelson, Shereen C Naser, and Elizabeth Carey. 2020. “Application of Child Rights to School-Based Consultation.” In International Handbook on Child Rights and School Psychology, edited by Bonnie K. Nastasi, Stuart N. Hart, and Shereen C. Naser, 391–406. Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Wisby, Emma. 2011. “Student Voice and New Models of Teacher Professionalism.” In The Student Voice Handbook: Bridging the Academic/Practitioner Divide, edited by Gerry Czerniawski, and Warren Kidd, 31–44. Bradford: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.