ABSTRACT

This paper reports on the findings from a study based in England, within a new school that opened its doors to students in August 2015. The school, established under relatively recent UK legislation as a ‘Free School’, set out to be inclusive, aiming to achieve this through its architecture and design, admissions policy, mixed attainment class organisation and inclusive teaching practices. The research project tracked the school’s growth and examined the extent to which it developed as an inclusive school. One key strand of the research involved photovoice with young people. Photographs within the school, taken by the young people were used as the basis for interviews about their school and their space and to explore social relations and inclusion/exclusion at the school. Findings emphasise that children and young people’s lived experiences of different school spaces may not always coincide with the ideas of the adults who initially conceived them, and furthermore illustrate the importance of acknowledging children and young people’s diverse needs and preferences in order to construct the school as an inclusive space.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Schools provide important spaces for children’s interaction and inclusion, and their role as facilitators of social mixing has been studied extensively (Bagci et al. Citation2014; Hollingworth and Mansaray Citation2012; Joseph and Feldman Citation2009; Pagani, Robustelli, and Martinelli Citation2011; Verkuyten and Thijs Citation2013). It has been acknowledged that simply being in the same school does not automatically involve engaging with other children of different backgrounds, and that explicit teacher strategies are often needed to encourage mixing and facilitate inclusive school spaces (Grütter and Meyer Citation2014; Mendoza Citation2019; Hemming Citation2011). However, children may experience school spaces in different ways than the adults around them (Yarwood and Tyrell Citation2012), and may furthermore differ significantly amongst themselves in their views of different spaces (Christensen, Mygind, and Bentsen Citation2015) and their inclusive potential. This raises the question of how to explore and understand the complexities of children’s experiences of inclusion and space and how to develop and sustain inclusive school practices, taking into consideration the spatial preferences and experiences of different groups of children and young people.Footnote1

In this paper, we address these questions drawing on findings from a research project carried out at a newly opened secondary free school in England. From its inception, the participating school set out to be inclusive through an admissions policy, which brought together students from four different areas of the city, and teaching practices, which included mixed attainment teaching (no streaming or setting of students) and extended enrichment (activities in addition to the main curriculum). Furthermore, the school’s architecture and design explicitly sought to facilitate inclusion and social interaction through its open, permeable and flexible spaces. The research project tracked the school’s growth and examined the extent to which students, parents, teachers and governors found it developed as an inclusive school, particularly for children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND).

Free schools are a relatively new type of school, introduced in England in 2010 by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government. As of 2019, over 500 free schools had been set up in England, with a further 220 announced (Mills, Hunt, and Andrews Citation2019). Free schools are a sub-set of academy schools and resemble charter schools in the US and free schools in Sweden in that they enable parents, community organisations, charities and universities to set up their own schools, funded by the government, but entitled to decide on their own curriculum, staffing and admissions arrangements. Most of the academic literature on free schools in England has focused on the composition of their student populations, their location and admissions policies (Green, Allen, and Jenkins Citation2015; Morris Citation2014, Citation2015; West Citation2014). Much less is known about the actual practices of the schools and whether the freedoms they are granted under the free school legislation may be used to facilitate inclusion. As many of the free schools are newly built, there is furthermore an important need to explore their inclusive potential from a spatial perspective, considering whether their architecture and design facilitate social and educational inclusion for the students inhabiting them.

Definitions of inclusion have tended to focus on the placement of children in mainstream schools (Allan Citation2007; Slee Citation2011), with little regard for their social interactions or learning. Efforts to elucidate the elements of an inclusive environment (Booth and Ainscow Citation2011; Pathways to Inclusion Citation2012) have affirmed the importance of space and emphasised the important role of culture but have added little to our understanding of inclusion as a concept. The World Bank (Citation2019) provides an exception with its emphasis on improving the terms on which individuals can participate in society and aligning it with human rights. It may still, however, be difficult to decide whether and when spaces can be considered inclusive. In this paper, we focus specifically on the young people’s description of space and their perspectives of inclusion at the school, understood in its broad sense as a process ‘whereby all children and young people are included both socially and educationally in an environment where they feel welcomed and where they can thrive and progress’ (Lauchlan and Greig Citation2015, 70).

Space, social interaction and inclusion

The social dimension of space has been discussed and analysed by a range of scholars, often with reference to Henri Lefebvre's (Citation1991) seminal work The Production of Space. To Lefebvre, spaces are products of physical, mental and social elements and the physical cannot be seen in isolation from the social and relational. His triad model of space encompasses ‘spatial practice’ (the way spaces are physically perceived and practiced), ‘representations of space’ (how they are mentally conceived by ‘scientists, planners, urbanists, technocratic subdividers and social engineers') and ‘representational spaces’ (how they are directly lived by the people inhabiting or using them) (38).

Drawing on Lefebvre, Soja (Citation1996) applied a similar triadic approach to the study of space. He described space as a combination of first space (what is physically present), second space (what is imagined) and third space, combining the first and the second space but also opening up for counter-spaces, resistance and negotiation. Like Lefevbre, Soja acknowledged the role of power dynamics in the constitution of space. Both Lefebvre and Soja’s frameworks of space emphasise that not only do spaces provide a background for social contact and may as such shape or influence the interactions of the people inhabiting them, they are also themselves fundamentally shaped by the social relations taking place within them. This is similarly discussed by Massey (Citation2009, 17) who argues that space is always ‘under construction’, and as a ‘product of our on-going world … . always open to the future’.

In this paper, we draw on these insights, acknowledging that physical spaces cannot be seen in separation from the social relations taking place and being negotiated within them. While shared spaces may offer potential for social relations to emerge (Ijla Citation2012), they may also serve to divide and separate (D’Alessio Citation2012). The physical lay-out of schools and the way different school spaces are set out are illustrative of the way in which a given society views social relations within and between different groups in society (Armstrong Citation1999). As such, school spaces are a product of the wider political, social and ideological context (Cook and Hemming Citation2011; Thomas Citation2011) and dominant ideas about learning and in/exclusion. However, spaces are also a product of the way that actors perceive and live within them. School spaces may thus be very differently experienced by the actors inhabiting them (Brown Citation2017; Lim, O’Halloran, and Podlasov Citation2012), and their use of different school spaces may entail various degrees of social negotiation and resistance.

Holloway and Valentine (Citation2000), drawing on James, Jenks, and Prout (Citation1998), remind us of the key role of schools in the spatial disciplining of students, largely through formal and informal curricula, but also highlight the possibilities for resistance by children and young people. Thomas (Citation2011, 171) goes further in her study of girls’ experience of schooling to identify the ‘banal multiculturalism’ that encourage an espousal of humanistic values of similarity whilst remaining invested in racial, sexual and gender differences. Hemming (Citation2011, 69) illustrates the impact of efforts by schools to facilitate social cohesion among its pupils, through careful ‘emotion work’ and by actively addressing friendships, co-operation and conflict. Both Thomas and Hemming emphasise the ‘futuring’ role of schools, looking beyond the present ‘getting along’ (Thomas Citation2011, 175) towards building citizens with competent civil behaviour.

Modern school architecture is often characterised by open, flexible and transparent learning spaces, which can be adapted to different teaching practices and techniques (Imms, Cleveland, and Fisher Citation2016) and encourage twenty-first century skills such as flexibility, adaptability and fluidity (Benade Citation2017). Open, visible and flexible spaces are also often presented as facilitating easier or more equal interaction between students themselves and with staff (Willis Citation2017). However, convertible school spaces may reveal certain tensions between a wish to control pupils and empowering them (Dovey and Fisher Citation2014). The way their lay-out has been intended by the adults designing them may furthermore differ from how children experience them (Kellock and Sexton Citation2018), emphasising the importance of exploring children’s diverse experiences of space, using the most appropriate methodology.

Methodological approaches to children’s experiences of space

Childhood studies, and in particular children’s geographies, have explored the many ways in which children use the spaces around them and (re)imagine them ‘to create their own worlds’ (Yarwood and Tyrell Citation2012, 124). Holt (Citation2006, Citation2011), and Ruddick (Citation2007) are among those who have cautioned against an exclusive focus on children’s agency at the expense of attention to structural factors, familial contexts and the experiences of children who might lack autonomy or independence such as disabled children. Thomas (Citation2011, 178) encourages a focus on power relations and a spatialising of narratives ‘so that the vibrant paradox that many subjects live is remembered’.

A variety of methods have been used to study children’s experiences of space including off-line or on-line ‘place mapping’ (Islam Citation2012; Literat Citation2013a; Travlou et al. Citation2008), child led walk-and-talk (Horton et al. Citation2014), drawings (Bland Citation2018; Literat Citation2013b), participatory video (Lomax Citation2012), photo-elicitation (Leonard and McKnight Citation2015) and photovoice (Lee and Abbott Citation2009; Zuch et al. Citation2013). Methods employed to explore children’s experiences of urban surroundings can be grouped into children ‘seeing’ the city and children ‘doing’ the city (Christensen and O’Brien Citation2003, 3), although the two may be combined and interact, as for example in the case of ‘photo-walk’ (Pyyry Citation2015). Photovoice is an example of a method which predominantly focuses on the way people ‘see’ the spaces they inhabit.

Photovoice involves research participants capturing images that are of importance to them, with more or less direction with regards to the topic, and inviting them to describe and explain the images they have taken. It has been found to be a powerful tool to explore the way research participants see and experience their environment, and as we will argue in this paper, can usefully be applied to understand children and young people’s experiences of inclusion and space. By letting research participants decide on the images they wish to capture and describe them in ways that are meaningful to them, photovoice allows different perspectives to emerge and can both challenge popular stereotypes and provide a basis for user-led changes. Within community and health studies, photo-elicitation has been found to enhance community engagement, improve understandings of the community and increase individual empowerment of the people involved (Catalani and Minkler Citation2010). It has also been described as a useful method in school research and research with children more broadly, as it presents a flexible method which gives children significant control over the topics discussed, acknowledges them as active participants in their own lives (Cooper Citation2017; Torre and Murphy Citation2015), helps bridge the gap between researcher and researched, and elicits a range of views and perspectives, which may differ from common adult perceptions (Woolner et al. Citation2010; Burke Citation2005; Zuch et al. Citation2013).

However, as Lomax (Citation2012) reminds us, it is important not to assume that visual methods, such as photovoice are automatically inclusive and offer ‘better insight’ than other types of methods. While she argues that child-led creative methods ‘may offer important insights into the lived experiences of children’s social geographies and, within the study of social inequality can provide an important challenge to persistent negative stereotyping of poorer children’s lives’ (114), she also shows that hierarchies and power dynamics between children may lead to some children’s contributions being given higher value by their peers than others. Like other childhood researchers (e.g. Horgan Citation2017; Kellett Citation2010), she argues against the construction of the singular ‘child voice’ and acknowledges the ways in which children may differ from one another, not only in their experiences, but also in the particular resources and skills they bring to the research process.

The study

‘Our School: Our space’ was a project carried out in 2016–2018 at a newly built English secondary free school. Its architecture and design were conceived as inclusive as it consisted of wide, open, bright and visible spaces that all students (including those with disabilities) could access and interact within and which (according to a senior staff member interviewed for the project) prevented bullying, as students could be seen at all times. The aims of the project were to examine how the school grew and developed as an inclusive school. In this paper, we specifically explore this question in relation to space and the experiences of the students within the school.

The interviews with the students were carried out in the academic school year 2016/2017, at a time when the school only had two year groups, Year 7 and Year 12. By the time the research was completed (academic year 2017/2018), the school had grown to five year groups (Year 7, 8, 9, 12 and 13) and had a total of 718 students.Footnote2 The school intake was diverse in terms of ethnicity and social background of students, and Key Stage 3 (Year 7–9) had a relatively high proportion of students with SEND support (12.7%) and an above average percentage of students with an Education and Health Care plan (7.2%), signifying that they needed more support than available through SEND support.

The project as a whole included group interviews with five groups of students (in total 22) and semi-structured individual interviews with 12 teachers, 4 senior school staff,Footnote3 3 professional service staff, 3 governors and 10 parents. In this paper, we report on the findings from the group interviews with students which were carried out at the beginning of the project with the use of photovoice methods. Students were recruited through their form tutors and consent was sought for all, including those with special needs, through an information sheet that was accessible to all. Prior to the interviews, each participating student was given a handheld electronic device and asked to take at least five pictures within the school. They were given one week to complete the task. Given the project's broader focus on inclusion and social capital (Allan and Jørgensen Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Jørgensen and Allan Citation2020), they were asked to focus on places that made them think of friendships, relationships and wellbeing. To ensure the privacy of other students, they were instructed to avoid taking clear photos of people’s faces. Fifty four photographs were taken by the students, with some taking only one or two and few taking more than five. We suspect that this was because the students became invested in particular images, which they described with great interest and some pride. The photographs were subsequently discussed in group interviews, using a focus group approach, where the students described their photos, talking about the different spaces they depicted and how they experienced the spaces and the social relations within them, opening up for discussion of both inclusive and exclusive practices. One student with significant special needs was not present during the group interview because she was absent on that day. Nevertheless, the other students presented her photographs and sought to recall what she had been attempting to capture.

Prior to data collection, the project was approved by the University of Birmingham’s ethical committee. All research participants were informed about the purpose of the project and gave their written consent to being interviewed and audio-recorded. The student groups were recruited through form group tutors who distributed an invitation to all students to take part in research about their school. For the photovoice and group interviews, consent was sought from both the young people and their parents.

For the data collection, all interviews were transcribed and thematically analysed, drawing out first initial and broad areas and later more refined topics and themes. As this paper has as its main objective to discuss the young people’s experiences of space and inclusion, we focus specifically on the group interviews with the students and their narratives around particular spaces, which they identified as important for friendships, social relations and wellbeing.

provides an overview of the different photographs taken by students from the two year groups (year 7 and year 12). Based on the amount of pictures taken for each area and the content of what the young people were talking about in relation to the pictures, we developed the framework presented below, which includes analysis of five key ‘spaces’: (1) the atrium, (2) the outdoor courtyard, (3) the library, (4) passed-through areas and (5) senior school areas.

Table 1. List of photographs taken by Year 7 and Year 12 students according to area within the school.

Findings

The atrium

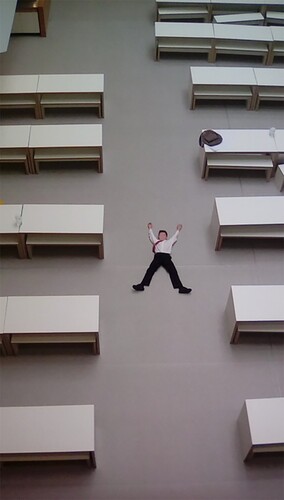

As with many newly built schools, the school featured a ‘flagship space’ (Kraftl Citation2012, 863) in the form of an atrium in the centre of the school. The atrium was a large open space, illuminated by overhead natural light and overlooked by all three floors of the school. Amongst students from both year groups, the atrium figured as a significant space, which was photographed seven times in total. When discussing the reasons for taking photos of the atrium, the young people often focused on the immense open space it provided, and its potential for socialising with your friends:

I decided to take the photo to highlight, because he's got his arms spread out, to show how much space there is. And you can sit anywhere really (, Year 7 Boy).

It’s just our tables that we sit on. That’s where we usually meet up. Its special to me, because I get to meet others and talk to them about how they are feeling and what their day has been like (, Year 7 Girl).

Girl: the boys always have this one.

Boy 1: and then you always have the table in front of us.

Boy 2: and I like this one because it's kind of mixed.

Girl: like (name of student) doesn't like sitting on our table.

Interviewer: so the boys have one at the top?

Boy 1: yeah that one or that one.

Girl: but our group is kind of mixed - it's both. Boys and girls.

Boy 2: you know like on Fridays, one of the form groups go and sit there (points to different table) so we go to a spare table, for example this one or this one.

Boy 1: and the teachers usually sit right at the very top.

Outdoor area

The outdoor area, consisting of two large basket/football courts, and an area with grass and trees also figured prominently in the photos taken by the young people. Students described the social potential of this space and made an important distinction between the indoor and the outdoor in terms of what they considered appropriate activities within the two :

I like the outdoor playground best, because you get to play football outside and you get to release all of your energy (Year 7 Boy).

I like the playground because when you are bored you can just go out there and have a run. Play anything which pretty much would be weird to do in school. You can make new friends on the playground (Year 7 Boy)

Year 7 Girl: like, sometimes they (Year 12) get bit annoyed because (another student) was joining in with one of the cricket games I think and they were getting a bit annoyed that the Year 7s were coming in. But normally most of the time they let us join in.

Year 7 Boy: often they'll take this space for their cricket and we'll take this space for our football.

Interviewer: so, outside there's a basketball court

Boy1: yeah usually we have the basketball court

Boy2: and then there's like a sneaky bit here.

Boy1: you're not exactly meant to go there but …

Girl: there was a log there and some people kept going and sitting on the log.

Interviewer: so are you allowed on the grass areas or just the tarmac?

All: no, you're not allowed on grass.

Library

The library, a large room on the top floor of the school building, was another space which provided an alternative to the busy environment of the school. Several of the students had taken photos of the physical structure of the library with its chairs, books etc. or of themselves reading books within the library. However, they explained that reading was only one function of the library. This was shown in the following quotation wherein a student tries to explain why another student (who was not present at the interview) had taken a photo of the library :

Interviewer: Do you know why she took this one?

Boy1: Yeah she likes reading

Boy2: Yeah it’s just sort of a nice place to relax.

Girl: They go round the tables and do each other’s hair and stuff.

Boy1: That’s my favourite book.

Boy2: And sometimes I play with my cards.

I like the library, because there is a time where you can be quiet and peaceful and if you like some quiet time by yourself … sometimes in the morning if my friends aren’t here, I go to the library to keep myself occupied till they come (Year 7 Boy).

‘Passed-through spaces’

The young people’s photos of ‘passed-through spaces' such as the locker areas and corridors, show that they saw them as equally significant to their social life at school, as well as to their sense of belonging and ownership and :

Year 7 Girl 1: Well, I took the picture of people opening their locker because it is like the end of the day or before the school day and people go to their lockers to get their stuff or hang with their friends, have conversations, everyone doing their thing

Interviewer: and are lockers quite important?

Year 7 Girl 2: actually, because we put our belonging there to keep them safe.

Year 7 Girl 3: you can also think it from a different point of view, because lots of us hang out around the lockers a lot. So then there is a lot more memories there.

[It is] one of the few personal spaces, which is just mine. My friends own the lockers next to me, so we have taken ownership of these three lockers (Year 12 boy).

Year 7 Girl: I just took this picture because it shows them having a laugh and messing about in the corridors.

Year 7 Boy: it was also the day me and [name] made a hand shake. Cause we were bored, so why not?

Senior school spaces

Several of the students in the Year 12 participant group had taken photos of the entrance to the sixth form block and their computer room. This reflected the amount of time they spent in there, but also and more importantly that it was a space they used for socialising :

[I took the photo of the computer room] … because I met most of my new friends in there and got to know everyone there (Year 12 girl)

We do a lot of work there and of course, the sixth form room is kind of our freedom area, because there aren’t a lot of instructions there (Year 12 girl).

Year 12 Girl 1: There is freedom, but restriction. There is freedom as in, no teachers are in there so we can do what we want, but within there, obviously people kind of abuse that sometimes. So, it is a bit noisy in there and you can’t always get done what you need to get done. So that’s the restriction part

Year 12 Girl 2: I think I agree about the sixth form block comment, because some people abuse the freedom that we’ve got. And so, it is not a very nice place to study. I think because of the noise level.

Year 12 Girl 1: Like, I don’t even like sitting there.

Interviewer: Really, how come?

Year 12 Girl 1: well, unless you are in that big group of kids that kind of rule it. It is kind not really for you, it’s kind of intimidating.

Year 12 Girl 2: It’s not like you’re totally scared to go in there, it is just that it is less comfortable.

Discussion

Our study has shown how children and young people often utilise spaces other than their classroom to socialise, make friends and as a source of wellbeing. As the photographs presented in this paper illustrate, the young people made use of the atrium, the outdoor area and quiet areas, such as the library, as well as informal, casual, transitional and seemingly insignificant spaces (Lomax Citation2012), such as corridors and locker areas, to interact, meet, and create social memories. The way the young people constructed the locker and corridor areas shows that these are spaces in constant development and negotiation (Massey Citation2009), with echoes of the epic study by Martha Muchow showing young people’s ‘attempts to make the terrain their turf’ (Behnken and Zinnecker Citation2015, 12). It also affirms the optimistic view of James, Jenks, and Prout (Citation1998) and Holloway and Valentine (Citation2000) regarding the potential for resisting the spatial disciplining that occurs within a school.

There appeared to be little emphasis on diversity by students when speaking about their use of school spaces – to meet your friends and/or escape the disciplinary gaze of adults. Elsewhere, these same students have described the value to them of the heterogeneity within the school and of welcoming the inclusivity of their environment (Allan and Jørgensen Citation2021a). Yet, their accounts of the school spaces seemed to reflect a certain preference for close friendship groups within the given spaces. The susceptibility of the spaces which have very little physical limitation (such as the atrium and the outdoors) to territorialisation further suggests a homogenising tendency. This apparent defaulting to similarity is concerning and lends weight to Thomas’s (Citation2011, 171) contention that, without interventions in relation to social relations, a ‘profound dysfunction’ whereby students are not educated about social difference will be maintained. Following Lefebvre (Citation1991), these spaces become constituted by the young people’s direct and lived experiences and not only do they often differ from the way such spaces were initially conceived (by adults); the spaces, as they are lived by the young people, are subverted by them (Shields Citation1999). The inclusive potential of school spaces depends on the extent to which students of all backgrounds are able to participate in the development and negotiation processes. Our findings, and those of Hemming (Citation2011) and Thomas (Citation2011), underline the importance of schools working to facilitate children’s participation in school spaces, including in seemingly insignificant ‘non-spaces’, such as corridors or locker areas, by facilitating social interaction and explicitly addressing friendships, co-operation and conflict through ‘emotion work’ (Hemming Citation2011, 68).

The findings suggest that the inclusive potential of school spaces has to be considered in relation to existing power dynamics, not only between students and teachers, but also between students themselves. In a study of social spaces of learning, Leander, Phillips, and Taylor (Citation2010) have criticised what they call a ‘container-approach’ to learning for focusing too much on the classroom and not acknowledging that ‘classrooms are intersections – not parking lots’ (366). This critique is instructive for our discussion of space and inclusion as it highlights the importance of exploring a variety of spaces and their inter-connections. The success of one space in fostering inclusive social relationships necessarily depends on the wider school ethos and what goes on in other spaces, including those outside of school. Power is a crucial element of such interconnections and the impact of broader social relations and developments. Consequently, these need to be considered in both the analysis of the data and in the methods used to obtain them.

Photovoice appeared to be a successful, and inclusive, way to approach children and young people’s experiences of space and their perceptions of social relations within interconnected spaces. Importantly, it also handed some of the power over to the students, to allow them and their photographs to direct the focus of the interviews. The competition and negotiation of space illustrated by some of the examples from our research highlights the key importance of diversity and representativeness in any creative process involving children, including those using photovoice. As participants for our study were recruited via their form tutor and self-selected, we cannot be certain that they were a representative sample of the school population. In fact, even though the purpose of the broader study was to study the inclusion of children with SEND, we did not actively seek to include pupils with SEND in our sample because we were asking pupils to volunteer to participate. Consequently only one of the children who volunteered to participate in the study had identified special educational needs. We subsequently arranged an additional group interview, which is not reported in this paper, but we acknowledge that the photovoice narratives analysed in this paper may only illuminate the experiences of a particular segment of the student body. Their varied narratives and the great span of photos seem, however, to suggest that some diversity was present and this provides a good starting point for understanding the experiences of space of students at the school.

The findings raise questions about the original design of the school and the explicit commitment to fostering interaction. Ogden et al. (Citation2010) have suggested that architects should pay close attention to how a building will be experienced by its end users, particularly in terms of how spaces can be transformed into ‘dwelling places’ (169), and it appears that this school would perhaps have benefited from greater foresight. Similarly, Kellock and Sexton (Citation2018) ask whether school spaces can be more flexible in how they meet functional and wider needs and suggest utilising children’s ideas to make more accessible, homely spaces. Birch et al. (Citation2017) have argued for an inter-generational dialogue between children and architects, which can become ‘a site for reciprocal learning and a sense of togetherness embodied in people’s interactions, relationships and shared meaning-making’ (233). The photovoice method in our study allowed for an exploration of the young people’s own perceptions and lived experiences of different spaces within the school and would potentially provide a promising approach to co-designing and/or co-developing inclusive school spaces. However, as Kellock and Sexton (Citation2018) point out, unless a proactive stance towards any suggested changes is adopted, any participatory activity is likely to be a tokenistic experience. This highlights the importance of acknowledging children’s experiences both in principle and in action.

Conclusion

The link between inclusion and space can be approached in different ways. One way is to focus on the access of children with SEND to a mainstream school space. Another, acknowledging a broader understanding of inclusion, is to look more closely at the social and educational inclusion of all students within a variety of school spaces. In this paper, we have adopted the latter approach, considering how the students in our study experienced and perceived the spaces they interacted within.

Photovoice offers a way of exploring children and young people’s experiences of inclusion and space. Its flexibility and creative child-led approach allows for an exploration of children’s own views of the various spaces they consider important for social interaction, friendships and wellbeing and enables alternative discourses to emerge with regards to spaces not traditionally considered socially significant. Lefebvre and Soja’s frameworks of space are helpful in understanding how the physical structure of spaces, the way they are conceived by (mainly adult) planners and practitioners and the lived experiences of children and young people interact, but may also contradict one another. Co-designing spaces with children may go some way to facilitate greater proximity between the conceptions and lived experiences of space, and photovoice may present one useful method of approaching this. As with other creative visual methods, the use of photovoice needs careful consideration of the power dynamics between children and adults and amongst children themselves to ensure that the voices of different groups of children can be heard and to avoid the reproduction of dominant conceptions of school spaces. In addition, researchers and practitioners need to consider how insights gained through the use of photovoice can be acted upon to avoid tokenistic involvement and to create spaces that are inclusive for all.

The data from this study have added weight to Lefebre’s and Soja’s assertion that ‘space matters’ (Soja Citation2010, 2) and, moreover, that judicious use of space can contribute to inclusion and belonging. Said (Citation1993) more forcefully contends that the battle for social justice is a battle for geography. Soja cautions us that the foregrounding of a spatial perspective does not mean a rejection of historical and sociological reasoning, but amounts rather to the flexing of interpretive muscles that have hitherto been unused in order to discover new insights and possibilities.

The depth of insight offered by the young people, through their choice of photographs and their narratives, suggest a significant degree of spatial competence and an ability to recreate apparently neutral, or transition spaces, such as the lockers and corridors into interactive, social spaces. At the very least, teachers might acknowledge this competence, but a more inclusive response could involve several additional elements: first a ‘looking away’ from those spaces that have been recreated by students (to allow interaction to flourish, unattended to by adults); second, some negotiated space within the more complex areas, such as the sixth form common room, whereby students were invited to develop protocols for using the space; and third, co-creation of space, involving students and teachers in reviewing the utilisation of the existing space and in the design of any future spaces. Such a response would acknowledge both the importance of space and the expertise that young people bring to it in order to live well within it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Clara Rübner Jørgensen

Clara Rübner Jørgensen is Assistant Professor in the Department for Disability, Inclusion and Special Needs at the School of Education, University of Birmingham. She is a social anthropologist with extensive experience in carrying out qualitative and ethnographic work in educational settings in the UK and internationally. Her research focuses on the educational experiences of different groups of children and young people, inclusive education and educational inequalities.

Julie Allan

Julie Allan is Professor of Equity and Inclusion at the University of Birmingham, UK, and was formerly the Head of the School of Education at Birmingham. Her research interests are in inclusion, equity and rights and she has provided expert advice to governments and published widely in these areas. Recent publications include the 2020 World Yearbook in Education: Schooling, Governance and Inequalities (Edited with Valerie Harwood and Clara R. Jørgensen and published by Routledge) and Psychopathology at School: Theorizing Mental Disorders in Education (written with Valerie Harwood and published by Routledge). Her new book, On the Self: Discourses of Mental Health and Education, written with Valerie Harwood, will be published by Palgrave.

Notes

1 In this paper, we use the term ‘children’ as a general category, when we talk about the school aged population, but refer to the participants in our study as ‘young people’, as they were all in secondary school and thus aged 11–18.

2 This was still far from its full capacity, which was reached in 2019/2020 when all year groups were recruited.

3 Including school managements and staff leading on a particular area of the school.

References

- Allan, J. 2007. Rethinking Inclusive Education: The Philosophers of Difference in Practice, Inclusive Education: Cross Cultural Perspectives. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Allan, J., and C. R. Jørgensen. 2021a. “Inclusion, Social Capital and Space Within an English Secondary Free School.” Children’s Geographies 19 (4): 419–431.

- Allan, J., and C. R. Jørgensen. 2021b. “Inclusive School Development: The First Years of an English Free School.” In Inclusion International: Global, National and Local Perspectives on Inclusion Education, edited by A. Köpfer, J. Powell, and R. Zahnd, 329–344. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

- Armstrong, F. 1999. “Inclusion, Curriculum and the Struggle for Space in School.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 3: 75–87.

- Bagci, S. C., M. Kumashiro, P. K. Smith, H. Blumberg, and A. Rutland. 2014. “Cross-Ethnic Friendships: Are They Really Rare? Evidence from Secondary Schools Around London.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 41: 125–137.

- Behnken, I., and J. Zinnecker. 2015. “Martha Muchow and Hans Heinrich Muchow: The Life Space of the Urban Child – The Loss and Discovery, Connections and Requisites.” In The Life Space of the Urban Child: Martha Muchow's Perspectives on a Classic Study, edited by G. Mey, and H. Gunther, 3–27. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Benade, L. 2017. “Is the Classroom Obsolete in the Twenty-First Century?” Educational Philosophy and Theory (49): 796–807.

- Birch, J., R. Parnell, M. Patsarika, and M. Šorn. 2017. “Participating Together: Dialogic Space for Children and Architects in the Design Process.” Children’s Geographies 15: 224–236.

- Bland, D. 2018. “Using Drawing in Research with Children: Lessons from Practice.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 41: 342–352.

- Booth, T., and M. Ainscow. 2011. The Index for Inclusion. Accessed January 12, 2021. http://www.csie.org.uk/resources/inclusion-index-explained.shtml.

- Brown, C. 2017. “‘Favourite Places in School’ for Lower-Set ‘Ability’ Pupils: School Groupings Practices and Children’s Spatial Orientations.” Children’s Geographies 15: 399–412.

- Burke, C. 2005. “'Play in Focus': Children Researching Their Own Spaces and Places for Play.” Children, Youth and Environments 15: 27–53.

- Catalani, C., and M. Minkler. 2010. “Photovoice: A Review of the Literature in Health and Public Health.” Health Education & Behavior 37: 424–451.

- Christensen, J. H., L. Mygind, and P. Bentsen. 2015. “Conceptions of Place: Approaching Space, Children and Physical Activity.” Children’s Geographies 13: 589–603.

- Christensen, P. M., and M. O’Brien, eds. 2003. Children in the City: Home, Neighbourhood and Community, Future of Childhood Series. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Cook, V. A., and P. J. Hemming. 2011. “Education Spaces: Embodied Dimensions and Dynamics.” Social & Cultural Geography 12: 1–8.

- Cooper, V. L. 2017. “Lost in Translation: Exploring Childhood Identity Using Photo-Elicitation.” Children’s Geographies (15): 625–637.

- D’Alessio, S. 2012. “Integrazione Scolastica and the Development of Inclusion in Italy: Does Space Matter?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 16: 519–534.

- den Besten, O., J. Horton, P. Adey, and P. Kraftl. 2011. “Claiming Events of School (Re)Design: Materialising the Promise of Building Schools for the Future.” Social & Cultural Geography (12): 9–26.

- Dovey, K., and K. Fisher. 2014. “Designing for Adaptation: The School as Socio-Spatial Assemblage.” The Journal of Architecture 19: 43–63.

- Green, F., R. Allen, and A. Jenkins. 2015. “Are English Free Schools Socially Selective? A Quantitative Analysis.” British Educational Research Journal 41: 907–924.

- Grütter, J., and B. Meyer. 2014. “Intergroup Friendship and Children’s Intentions for Social Exclusion in Integrative Classrooms: The Moderating Role of Teachers’ Diversity Beliefs: Social Exclusion in Integrative Classrooms.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 44 (7): 481–494.

- Hemming, P. 2011. “Meaningful Encounters? Religion and Social Cohesion in the English Primary School.” Social and Cultural Geography 12 (1): 63–81.

- Hollingworth, S., and A. Mansaray. 2012. “Conviviality Under the Cosmopolitan Canopy? Social Mixing and Friendships in an Urban Secondary School.” Sociological Research Online (17): 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.2561.

- Holloway, S., and G. Valentine. 2000. “Spatiality and the New Social Studies of Childhood.” Sociology 34 (4): 763–783.

- Holt, L. 2006. “Exploring Other Childhoods Through Quantitative Secondary Analysis of Large Scale Surveys: Opportunities and Challenges for Children's Geographies.” Children's Geographies 4 (2): 143–155.

- Holt, L. 2011. “Introduction: Geographies of Children, Youth and Families: Disentangling the Socio-Spacial Contexts of Young People Across the Globalizing World.” In Geographies of Children, Youth and Families: An International Perspective, edited by L. Holt, 1–8. London: Routledge.

- Horgan, D. 2017. “Child Participatory Research Methods: Attempts to Go ‘Deeper.’.” Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark) 24: 245–259.

- Horton, J., P. Christensen, P. Kraftl, and S. Hadfield-Hill. 2014. “‘Walking … Just Walking’: How Children and Young People’s Everyday Pedestrian Practices Matter.” Social & Cultural Geography 15: 94–115.

- Ijla, M. 2012. “Does Public Space Create Social Capital?” International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 4: 48–53.

- Imms, W., B. Cleveland, and K. Fisher. 2016. Evaluating Learning Enviroments: Snapshots of Emerging Issues, Methods and Knowledge. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Islam, M. Z. 2012. “Using Google Earth to Study Children’s Neighborhoods: An Application in Dhaka, Bangladesh.” Children, Youth and Environments 22: 93–111.

- James, A., C. Jenks, and A. Prout. 1998. Theorizing Childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Jørgensen, C. R., and J. Allan. 2020. “Education, Schooling and Inclusive Practice at a Secondary Free School in England.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 41 (4): 507–522.

- Joseph, M., and J. Feldman. 2009. “Creating and Sustaining Successful Mixed-Income Communities: Conceptualizing the Role of Schools.” Education and Urban Society 41: 623–652.

- Kellett, M., et al. 2010. “WeCan2: Exploring the Implications of Young People with Learning Disabilities Engaging in Their Own Research.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 25: 31–44.

- Kellock, A., and J. Sexton. 2018. “Whose Space is it Anyway? Learning About Space to Make Space to Learn.” Children’s Geographies 16: 115–127.

- Kraftl, P. 2012. “Utopian Promise or Burdensome Responsibility? A Critical Analysis of the UK Government’s Building Schools for the Future Policy.” Antipode 44: 847–870.

- Lauchlan, F., and S. Greig. 2015. “Educational Inclusion in England: Origins, Perspectives and Current Directions: Inclusive Education in England.” Support for Learning 30: 69–82.

- Leander, K. M., N. C. Phillips, and K. H. Taylor. 2010. “The Changing Social Spaces of Learning: Mapping New Mobilities.” Review of Research in Education (34): 329–394.

- Lee, J., and R. Abbott. 2009. “Physical Activity and Rural Young People’s Sense of Place.” Children’s Geographies 7: 191–208.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Leonard, M., and M. McKnight. 2015. “Look and Tell: Using Photo-Elicitation Methods with Teenagers.” Children’s Geographies 13: 629–642.

- Lim, F. V., K. L. O’Halloran, and A. Podlasov. 2012. “Spatial Pedagogy: Mapping Meanings in the Use of Classroom Space.” Cambridge Journal of Education 42: 235–251.

- Literat, I. 2013a. “Participatory Mapping with Urban Youth: The Visual Elicitation of Socio-Spatial Research Data.” Learning, Media and Technology 38: 198–216.

- Literat, I. 2013b. “'A Pencil for Your Thoughts': Participatory Drawing as a Visual Research Method with Children and Youth.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12: 84–98.

- Lomax, H. 2012. “Contested Voices? Methodological Tensions in Creative Visual Research with Children.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 15: 105–117.

- Massey, D. 2009. “Concepts of Space and Power in Theory and in Political Practice.” Documents D'Anàlisi Geogràfica 55: 15–26.

- Mendoza, M. 2019. “To Mix or Not to Mix? Exploring the Dispositions to Otherness in Schools.” European Educational Research Journal (18): 426–438.

- Mills, B., E. Hunt, and J. Andrews. 2019. “Free Schools in England - 2019 Report” Education Policy Institute. Accessed January 16, 2021. https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/free-schools-2019-report/.

- Morris, R. 2014. “The Admissions Criteria of Secondary Free Schools.” Oxford Review of Education 40: 389–409.

- Morris, R. 2015. “Free Schools and Disadvantaged Intakes.” British Educational Research Journal 41: 535–552.

- Ogden, H., R. Upitis, J. Brook, A. Peterson, J. Davies, and M. Troop. 2010. “Entering School: How Entryways and Foyers Foster Social Interaction.” Children, Youth and Environments 20: 150–174.

- Pagani, C., F. Robustelli, and C. Martinelli. 2011. “School, Cultural Diversity, Multiculturalism, and Contact.” Intercultural Education 22: 337–349.

- Pathways to Inclusion (P2i). 2012. Analysis of the Use and Value of the Index for Inclusion (Booth and Ainscow 2011) and other Instruments to Assess and Develop Inclusive Education Practice in Partner Countries. https://www.icevi- europe.org/enletter/issue51-09EASPD3.pdf.

- Pyyry, N. 2015. “‘Sensing With’ Photography and ‘Thinking With’ Photographs in Research Into Teenage Girls’ Hanging out.” Children’s Geographies 13: 149–163.

- Ruddick, S. 2007. “At the Horizons of the Subject: Neo-Liberalism, Neo-Conservatism and the Rights of the Child. Part One: From ‘Knowing’ Fetus to ‘Confused’ Child.” Gender, Place and Culture 14 (5): 513–527.

- Said, E. W. 1993. Culture and Imperialism. London: Chatto and Windus.

- Shields, R. 1999. Lefebvre, Love, and Struggle: Spatial Dialectics, International Library of Sociology. London: Routledge.

- Slee, R. 2011. The Irregular School: Exclusion, Schooling, and Inclusive Education. 1st ed. London, New York: Routledge.

- Soja, E. W. 1996. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-And-Imagined Places. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Soja, E. W. 2010. Seeking Spatial Justice, Globalization and Community Series. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Thomas, Mary E. 2011. Multicultural Girlhood: Racism, Sexuality and the Conflicted Spaces of American Education. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Torre, D., and J. Murphy. 2015. “A Different Lens: Changing Perspectives Using Photo-Elicitation Interviews.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 23: 111.

- Travlou, P., P. E. Owens, C. W. Thompson, and L. Maxwell. 2008. “Place Mapping with Teenagers: Locating Their Territories and Documenting Their Experience of the Public Realm.” Children’s Geographies 6: 309–326.

- Verkuyten, M., and J. Thijs. 2013. “Multicultural Education and Inter-Ethnic Attitudes: An Intergroup Perspective.” European Psychologist 18: 179–190.

- West, A. 2014. “Academies in England and Independent Schools (fristående skolor) in Sweden: Policy, Privatisation, Access and Segregation.” Research Papers in Education 29: 330–350.

- Willis, J. 2017. “Architecture and the School in the Twentieth Century.” In Designing Schools Space, Place and Pedagogy, edited by K. Darian-Smith, and J. Willis, 1–8. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Woolner, P., J. Clark, E. Hall, L. Tiplady, U. Thomas, and K. Wall. 2010. “Pictures are Necessary but not Sufficient: Using a Range of Visual Methods to Engage Users About School Design.” Learning Environments Research 13: 1–22.

- The World Bank. 2019. Social Inclusion. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/social-inclusion.

- Yarwood, R., and N. Tyrell. 2012. “Why Children’s Geographies?” Geography (sheffield, England) 97: 123–128.

- Zuch, M., C. Mathews, P. De Koker, Y. Mtshizana, and A. Mason-Jones. 2013. “Evaluation of a Photovoice Pilot Project for School Safety in South Africa.” Children, Youth and Environments 23: 180.