ABSTRACT

Children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) have a profoundly higher risk of death or injury than their peers when natural disasters occur. International policies call for inclusive disaster risk reduction education (DRRE) to help ameliorate this situation. This paper focuses on Indonesia, which has one the highest incidences of these disasters. A three-part structured literature review was undertaken regarding DRRE and children with SEND, followed by a questionnaire to in schools. Firstly, potential papers were screened against explicit criteria, yielding 23 papers for inclusion in the review. Secondly, these 23 papers were screened for identifiable DRR programmes, producing 12 items. Thirdly, evaluations of these 12 programmes were sought. The findings revealed that children with SEND were largely absent within the published research, the DRRE programmes, and all subsequent evaluations of the DRRE programmes. Questionnaire responses from 769 teachers from across Indonesia indicated that DRRE was often lacking, and that no programmes that were being used were accessible for all children. This is the first study to gain this insight and it concludes that there is a need for DRRE across mainstream, inclusive, and special schools, which has an inclusive and enagaing pedagogy that is accessible for all children.

Introduction

Global climate change is exacerbating the risk of extreme weather events, with the number of climate-related disasters tripling in the last three decades (Oxfam Citation2021). Indonesia sits within the Pacific region’s ‘ring of fire’ and is one of the nations that experiences most disasters each year through volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, earthquakes, and floods; between 1900 and 2022 a total of 582 disasters have been recorded, with 343 of these between 2000 and 2022Footnote1 (EM-DAT The International Disaster Database; Guha-Sapir, Below, and Hoyois Citation2022). Between 2000 and 2022 188,804 people lost their lives, making Indonesia the nation with the second highest death toll from disasters during this period, surpassed only by Haiti (EM-DAT The International Disaster Database; Guha-Sapir, Below, and Hoyois Citation2022). The Indonesian National Board for Disaster Management Agency (BNPB) reported 185 disasters the first three weeks of 2021 alone (ABC News Citation2021) and there has been at least one major event each month since the devastating 2004 tsunami (Mercy Corps Citation2020).

However, incidence of death, and injury from these events is not evenly distributed. As in other countries, the death and injury rate of disabled people/persons with disabilities is much higher than other people (USAID Citation2021) and the rate for children is ‘alarmingly high’ (Dyregrov, Yule, and Olff Citation2018), accounting for 30–50% of deaths (Amri et al. Citation2017). In Indonesia this risk is profoundly higher for children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) (Indriasari, Widyarani, and Kusuma Citation2018; Mubarak, Amiruddin, and Gaus Citation2019).

In seeking to respond to the increased risk for disabled people, international and government policies and conventions have foregrounded disabled people in relation to disaster risk reduction (for example as in the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 and the Incheon Strategy 2013–2022 cited in Calgaro, Villeneuve, and Roberts Citation2020). This recognition contains an explicit acknowledgment that the inclusion of disabled people within disaster risk reduction (DRR) programmes is a human right and these people must be afforded the same rights to this DRR as any other citizen (Calgaro, Villeneuve, and Roberts Citation2020). All Indonesian citizens have this right, within a legal framework (act no. 24 of 2007), to receive DRR education (Amri et al. Citation2017). Despite this explicit desire by policy makers, researchers have concluded that how this inclusion and ‘greater disaster justice’ might be achieved remains unclear (Calgaro, Villeneuve, and Roberts Citation2020).

These issues of representation and provision appear to be an issue within the field of researching and creating disaster risk reduction education for all children. A decade ago the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies concluded that there was ‘limited research on the ‘impact of education in the prevention of, response to’ natural disasters and complex emergencies (Global Education Cluster (GEC) Citation2012). However, subsequently there has been a growing evidence base showing the efficacy of DRRE in reducing the risk of death and injury of children (Mubarak, Amiruddin, and Gaus Citation2019; Proulx and Aboud Citation2019; Torani et al. Citation2019). The issue of ‘limited research’ appears to remain confined to evidence regarding the children who are most at risk, i.e. children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) (Ronoh Citation2017; Ronoh, Gaillard, and Marlowe Citation2015), and notably so in Indonesia, where these young people have profoundly higher risks of death and injury than their peers (Ha Citation2016; Stough and Kang Citation2015). It has been identifed that there is a research gap concerning DRR education and children with SEND, and that an overall picture of what research does exist is lacking (Ronoh, Gaillard, and Marlowe Citation2015; Mubarak, Amiruddin, and Gaus Citation2019).

Inclusive education and DRRE

Since 2009 the Indonesian government’s drive to create an inclusive education system (Ediyanto et al. Citation2017) has provided opportunities for children who might previously have been excluded from education, and therefore also lacked access to DRRE. Beginning at the same time, the government began piloting Sekolah Siaga Bencana, disaster-prepared schools (more recently called Sekolah Aman Benccana, disaster safe schools) and by 2013 there were over 25,000 such schools implementing DRRE (Amri et al. Citation2017). The majority of the ‘new’ pupils in the system have intellectual disabilities (Sunardi et al. Citation2011) and are likely to face challenges in accessing a standard school curriculum. However, it is rare for schools to modify their pedagogy or materials (Sheehy and Budiyanto Citation2015; Sunardi et al. Citation2011).

This suggests that there might be a lack of DRRE able to accommodate children with SEND. This is a longstanding issue. For example, in 2012 UNICEF carried out a major review: Disaster risk reduction in school curricula: case studies from thirty countries’ (UNICEF Citation2012). Within this landmark work, the term ‘ disability’ was mentioned only twice, in two case studies (Cambodia and The Philippines) that stated the need for developing pedagogical strategies that were effective for children with SEND. The Indonesian case study in this review noted the use of ‘hazard-specific textbooks’, for all levels, that address ‘disaster knowledge, preparedness and recovery’ (p.98). Because Indonesian schools develop local curriculum content, the potential was identified for DRRE curriculum developments that were sensitive to ‘the specific local needs and contexts in the world’s largest archipelago’ (p.98) (UNICEF Citation2012) and examples were given of teachers being encouraged to create their own localised textbooks. However, the issue of inclusive education was not considered, and the report concluded that there were no disability related ‘learning outcomes for disaster risk reduction education’ (p.53) (UNICEF Citation2012). Although DRRE was apparently incorporated into all levels of Indonesia’s national curriculum from 2009 (Amri et al. Citation2017), subsequent research found that Indonesian schools were ill-prepared pedagogically and might lack or not implement a curriculum on disaster education (Putri Citation2014). These findings suggested that DRRE curriculum activities might not be present in all schools or that, where they were present, then the access preferences (Garcia Carrizosa et al. Citation2020) of children with SEND were unlikely to be considered. The extent to which this might currently be the case in Indonesian remains unknown.

The UNICEF Indonesian case study also highlighted the importance, and challenges, of moving away from the ubiquitous transmissive teaching approaches, towards new participatory approaches (UNICEF Citation2012). There is some suggestion that this development has not yet happened. For example, with regard to accessible and inclusive DRRE for children with visual impairments (VI) and Deaf or hard of hearing (DHH) children, Nikolaraizi et al. (Citation2021) concluded that internationally

there is no research in relation to the education of children with VI or children who are DHH, while the existing research in relation to children with disabilities does not always involve them as active participants. (Nikolaraizi et al. Citation2021)

This research aimed to begin to address the existing research gap by (a) gaining a picture of Indonesian DRRE research and DRRE programmes that consider children with SEND and (b) collecting data regarding current materials, practices and needs.

Method

This study used a three-part review of research followed by an online survey.

Structured literature review

Several methods of literature review exist, each of which has different merits. Across these various approaches there is no agreed coherent review terminology, and much overlap and inconsistency exists (Grant and Booth Citation2009; Pham et al. Citation2014). Therefore, methods were assessed in relation to the aim of the current research. This sought to examine the research that existed in a way that would allow this examination to be repeated at a later date, to identify changes in the field or support comparative research. A systematic literature review would allow this as its pre-defined process is rigorous and ensures that the outcomes are reliable and meaningful. Other similar approaches were considered, such as a Scoping review (Pham et al. Citation2014). This broader approach is less clearly defined (Pham et al. Citation2014) but has merit in relation to identifying gaps in a research field where it is unclear what specific questions might be posed (Munn et al. 2019). Consequently, a structured literature review was carried out (). The term ‘structured’ (Armitage and Keeble-Allen Citation2008) is used rather than systematic, as this review did not require the full systematic review criteria such as assigning a weighting to the articles under review, as might be done with regard to reported effect sizes (Newman and Gough Citation2020; Karolinska Institutet Citation2017). This general method is well established for exploring education and inclusive research issues (Rix et al. Citation2020) and its transparency is helpful to other researchers in the field (Sheehy et al. Citation2019).

The core search was carried out using specified keywords to select and filter search results within the Scopus database. Scopus was chosen due to the interdisciplinary nature of DRRE. It is the world’s largest database of peer reviewed abstracts and covers a broad and comprehensive spectrum of research, which includes social, life, physical, and health sciences. The keywords used for this search were

Children.

Disability Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction

‘Disaster risk reduction education’

Disaster risk reduction’,

‘Disaster risk management’

Risk communication’

Hazard education’

‘inclusive’,

‘accessible’,

‘disability’

‘universal’

Special educational needs or disabilities or sensory/physical impairments.

Indonesia

The keyword searches utilised specific inclusion criteria:

Written in English language

Published between 2010 and April 2021

Contains keywords 1 and 13 (Children and Indonesia) and at least one of 2–6 and any of 7–12.

Concerned with children (children/youth/students/young people), but may be mediated through parents/ carers /teachers

NOT: duplicates, book chapters, conference papers, books, theses.

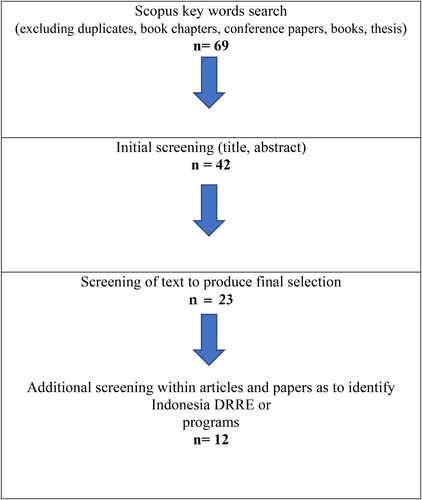

Abstracts that did not meet these inclusion criteria were excluded. If the abstract was ambiguous then the full article was screened. In addition, after selection, articles were screened to identify programmes running in Indonesian schools (see ).

To be included articles had to contain keywords 1 and 13 (Children and Indonesia) and at least one of 2–6 and any of 7–12. This yielded 69 potential research papers and after further screening 23 papers were selected (see online supplementary data Appendix 1). Within these papers 12 indicated DRRE programmes or interventions in Indonesia (See online supplementary data Appendix 2).

As illustrates the screening process identified 23 papers (see online supplementary data Appendix 1), and within these papers 12 indicated DRRE programmes or interventions in Indonesia (See online supplementary data Appendix 2). Evaluations of these 12 programmes were then sought (See online supplementary data Appendix 2).

Research questionnaire

An online survey was developed, consisting of 15 items (see online supplementary data Appendix 3). Besides collecting demographic and occupational data (Q1–Q4), it asked about Signalong Indonesia (Q5, Q6), a form of keyword signing to support curriculum access for pupils who might previously have been excluded from education (Rofiah et al. Citation2021a). This acted as an indicator of schools that used an identifiable inclusive strategy within their teaching. Respondents were subsequently asked about the presence of DRRE programmes in their schools (Q7-Q11), their accessibility for different groups of children, and the type of teaching approach that would work for them and children with special educational needs or disabilities (Q12, Q13). Lastly, participants were asked to respond to the statement ‘It is the teacher’s role to teach all children about natural disasters and what to do when they happen’, which was followed with space for optional further comments.

Questionnaire responses were collected using the Qualtrics platform and then downloaded to software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v25) for descriptive analysis. Given the nature of the analysis, cleaning the data was straightforward. The issue of including incomplete answers was considered. As participants were given the choice of answering or not any question, all items were retained for incomplete sets. Open ended questions were reviewed, for example to identify nonsense text, however, all answers were identified as appropriate.

The research was reviewed and given a favourable by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Open University (HREC/4097/Sheehy). A link to the questionnaire was posted during an international webinar on disaster risk reduction hosted by Universitas Negeri Surabaya in November 2021. Conference attendees could choose to read and anonymously complete the questionnaire.

Findings

Structured review: confirming a gap in Indonesian DRR research concerning children with SEND

Within the 23 selected papers, there were three systematic reviews that mentioned Indonesia. These were all identified through ‘children’ AND ‘disaster risk reduction education’ AND ‘Indonesia’. Only one of these studies considered disability, in relation to a need for ‘Access to safe places for people with disabilities’ (Mirzaei et al. Citation2019, 12). Seddigghi and colleagues’ international review (Seddighi et al. Citation2021) drew on two studies that mentioned disabilities but did not mention children with SEND within their review, and Rahiem and Rahim (Rahiem and Rahim Citation2020) did not consider the issue in their review of Folklore in Early Childhood Disaster Education. The conclusion from examining these three recent systematic reviews, which included Indonesia and drew together numerous studies in the field, is that children with SEND are entirely absent from these research findings or recommendations for future research. This suggests that not only are the most vulnerable children omitted from the area of research, but that this absence is not necessarily being identified by those evaluating research on DRRE and Indonesian children.

Of the remaining selected papers, one discussed children and disability (Pertiwi, Llewellyn, and Villeneuve Citation2020). This article focused on Indonesian DRR laws and disability. It highlighted the legislation that exists to support DRRE for all children, for example the ‘Guideline on Implementation of Safe School’ (BNPB Regulation 4 of 2012) which explicitly directs educators to provide for children with SEND in accordance with the principles of inclusiveness. Pertiwi et al conclude that whilst appropriate legislation exists, there is a need for the ‘development of technical guidelines on [the] implementation of disability-inclusive DRR’ (Pertiwi, Llewellyn, and Villeneuve Citation2020, 1).

The 23 selected articles were screened for indications of DRRE programmes or guidance documents and 12 were identified (see online supplementary data Appendix 2). Of these 12 articles, only one considered children with SEND, A Practical Guideline to Making School Safer from Natural Disaster for School Principals and School Committees (Indonesian National Agency for Disaster Management (BNPB Citation2014)). This document is a model of good DRRE practice for school development. Its focus is essentially structural in nature, with an emphasis on inclusive design to ensure that during a disaster there should be a suitable evacuation route for ‘disabled people’ to ensure that ‘All school members including people with special need/disable can do self-evacuation’ (81). The document makes some reference to pedagogy and sees children’s awareness and understanding being enabled though DRRE that is embedded throughout the curriculum in books.

reading materials such as books, guidelines on disaster risk reduction in school curriculum can be integrated into subjects such as geography, environment, and or extracurricular activities. (16)

This document offers sound DDR guidance, based on national Indonesian recommendations that reflect successful practice in other countries. However, within the suggested ‘non-structural’ curriculum activities, such as drill and simulated practice, the notion of inclusive pedagogy or the DRR curriculum access needs of pupils with SEND are not considered.

Many of the 12 programmes had been evaluated or researched further (see online supplementary data Appendix 2). Following up and reviewing these evaluations indicated that notions of disability and inclusive DRRE were absent, apart from one instance. An evaluation of Maena for Disaster Education mentions that ‘it is not evident whether this program could be effective for persons with disability’ (Shoji, Takafuji, and Harada Citation2020, 12). As with the three systematic reviews, children with SEND were not explicitly considered in subsequent programme evaluations. Consequently, programmes are unlikely to become more inclusive or accessible as a result of subsequent research. This finding supports Pertiwi’s identification (Pertiwi, Llewellyn, and Villeneuve Citation2020) of a need for guidance on how to develop and implement inclusive DRRE.

Whilst this gap might appear in published research, it is possible that this does not reflect what is happening ‘on the ground’ at school level and that, locally, DRRE is being delivered to children with SEND. Therefore, a questionnaire method was used to gain insights into this issue.

Questionnaire responses

The online questionnaire was completed by 769 participants from 17 Indonesian provinces (). The majority of participations were teachers or student teachers (74%). The remaining 26% included those who indicated their occupation as head teachers (n = 10), university lecturers (n = 8), administrators of a university support service for disabled students (n = 2), parents (n = 22), a therapist, one youth representative of a political party, with the remainder being (non-teaching) students.

The majority of participants (79%) were from Java, and 6.6% did not indicate their province.

Current use of DRRE programmes

The use of DRRE programmes in schools was reported by 172 teachers from 16 provinces.

A variety of programmes were named or described. Some of these were training courses that the respondents had undertaken. The most common course was the Psychology of Crisis and Disasters. This e-learning course from Universitas Islam Negeri Raden Intan Lamung discusses the handling of crisis and disaster conditions (Damyant Citation2021) and was indicated by 12 respondents. The acronym SMCC was given by five people, which probably refers to a centre at the Universitas Negeri Surabaya that supports disaster response training.

(This is ambiguous as it could also refer to the Strengthening Movement Coordination and Cooperation (SMCC) model (Awan et al. Citation2019) or, less likely, the Social Media Crisis Communication Model (Bukar et al. Citation2021) which looks at information distribution in crises situations). Six teachers reported attending courses on Crises and Disaster at a Crisis Centre Mitigation Unit, with others undertaking general training in relation to managing fires or floods.

More directly related to children’s learning were responses that indicated how DRRE was embedded into school curricula and activities. For example, ‘In early childhood learning at my institution there is a theme of the universe, where early childhood [pupils] is given an understanding of the dangers of natural disasters’. Integrating DRRE into this curriculum theme was mentioned by six respondents. Examples were also given of a variety of local practices, which represented their schools’ DRRE programme. This included simulation of earthquake, fire, flood and/or tsunami situations and how to respond (n = 7), and school greening, and anti-litter and fire prevention programmes (n = 7). Question 9 about disaster preparedness education in their schools was answered by 337 people. In 56% of these cases, it was integrated into the curriculum, and it was taught separately in 44% of cases.

Together these responses indicate that, where DRRE occurs, a variety of local practices exist, reflecting local situations and priorities, within Indonesia’s locally devolved curriculum (Putera Citation2018).

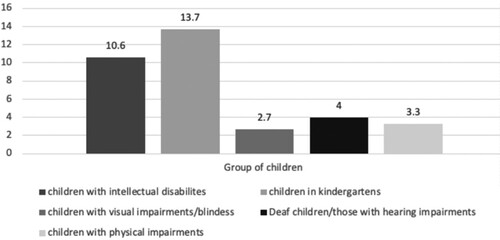

Question 10, regarding the accessibility of their DRRE programmes and activities, was responded to by 236 participants and is summarised in .

Figure 3. Percentage of DRRE programmes in participants’ schools that are accessible for different groups of children.

As indicates, the majority felt that the programmes they knew of were not accessible. Some were identified as accessible for some groups, ranging between 2.7% of respondents who felt that the programmes they knew were accessible to children with a visual impairment, and 10.6% of respondents regarding children with intellectual disabilities. Participants commenting on the same programme could have a different perspective on its accessibility and no programme was seen as accessible to all groups.

Questions about the use of Signalong Indonesia (SI), were used as a way of identifying schools that were developing inclusive approaches (Budiyanto et al. Citation2020). Across all the participants 29% had heard of keyword signing and 47% of this group, indicated that it was primarily used to support teaching and other activities. A small number used more recent SI materials such as Sign Supported Big Books (n = 21) (Rofiah et al. Citation2021a) or the Signalong Indonesia app (n = 6) (https://signalongindonesia.unesa.ac.id.). Signalong Indonesia was being used to support teaching in 104 mainstream schools, 12 inclusive schools and 2 special schools. Whilst schools may be developing inclusive pedagogies in other ways, these responses alone highlight that some mainstream schools are striving to be inclusive and accommodate a diverse range of pupils. Consequently, the accessibility of DRRE is not only relevant to special or designated inclusive schools.

Responses to Q14 revealed that the majority (86%) agreed that ‘It is the teacher’s role to teach all children about natural disasters and what to do when they happen’. This belief was common across teachers of children of different age ranges and from mainstream, inclusive, and special schools. Only a small number disagreed. For example, with regard to type of school, mainstream (8%), inclusive (5%) and special school teachers (6%) disagreed that it was their role. However, only 4% of all respondents felt the that their current approach worked and 92% thought that new accessible materials were needed. In terms of where this provision should occur, 48% felt that the provision of accessible materials to schools was needed and 47% preferred a community-based approach to their creation.

Discussion

The research produces several original findings and highlights factors that have an impact on the educational experiences and life risks of children with SEND in Indonesia.

The findings confirm the suggestions of other researchers (Ronoh Citation2017; Mubarak, Amiruddin, and Gaus Citation2019) that there is a paucity of research concerning DRRE in relation to children with disabilities. It reveals the absence of this group from the research agenda and goes beyond this to indicate, for the first time, that this absence applies not only to the research being undertaken, but also to research reviews undertaken by third parties. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, the same phenomenon was identified in the sample of Indonesian DRRE programmes and the evaluations of these programmes. This means that the DRRE programmes are unlikely to accommodate children with SEND and that subsequent evaluations of these programmes do not raise this issue or suggest how programmes might develop to be more accessible or inclusive. Calgaro, Villeneuve, and Roberts (Citation2020) highlighted that ‘People with disabilities are largely unseen, unheard and unaccounted for in all levels of disaster management’ (p321) and suggested that significant factors in this situation were structural, systemic and attitudinal barriers. The current research supports and extend their conclusions. The invisibility of inclusivity and access within Indonesian DRR research, education programmes, and evaluations suggests that there is a structural, systemic issue which will have a profound effect on the lives of children. The most vulnerable group, those most likely to be hardest hit by natural disasters, appear to lack a meaningful presence within the Indonesian DRRE research agenda.

A caveat to this is claim is that the research review only considered English language publications. However, nuanced support for this claim is provided by the questionnaire responses. Although DRRE might lacking for many children, with only 23% of participants reporting DRRE programmes within their schools, none were seen as being accessible for all children and only a small minority were accessible for some groups of children. Therefore, even though there may be programmes which were not identified in the review, for example being published in Indonesian language, the ‘on- the-ground’ reports of participants suggest that inclusion and accessibility are not prioritised with currently operational programmes. The use of Signalong Indonesia, although a relatively new approach (Budiyanto et al. Citation2017b) within mainstream schools suggests that creating inclusive and accessible DREE is relevant to all schools, not only the relatively smaller number of inclusive or special schools in Indonesia.

A social model perspective

Disability activists seeking to improve services for children often draw upon the social model of disability (Oliver Citation2013). This perspective foregrounds how social and environmental barriers, such as attitudes and professional discourses and practices, can be ‘disabling’. This has parallels with a perspective that the concept of a ‘natural disaster’ is misleading, as disasters to a large extent can be seen as the outcome of long term, lack of, planning and society's attitudes. As Kelman states

Disasters are caused by society and societal processes, forming and perpetuating vulnerabilities through activities, attitudes, behaviour, decisions, paradigms, and values. (p2) (Kelman Citation2019)

This has resonance with our findings. The absence of disabled children within Indonesian DRRE research and provision is the outcome of societal processes and decisions, which shape the vulnerability of this group of children when extreme environmental events occur. If we are to address this situation then there is a need for future research to explore these underpinning attitudes, processes, and decisions.

A way forward

The findings suggest that Indonesian DRRE research and practice do not foreground the needs of children with SEND. Thus, in a context where many schools do not implement DRRE, even those that do are unlikely to meet the needs of all children. This contrasts markedly with Indonesian policy aspirations that such provision should be developed and implemented (Hasan Dawi and Ahmad Citation2019). This raises the questions of the best way forward, what inclusive DRRE provision could look like, and how it might best be implemented in a context where there appears to be a general lack of implementation.

One useful starting point would be to identify existing best practices. Our findings show that some teachers identified current practices as being accessible for specific groups of children. Therefore, these examples should be sought out and explored further to examine what is happening in these schools and to identify the factors that have facilitated the implementation of these, at least partially, accessible classroom practices. This could be complemented with a review of Indonesian language publications and ‘grey’ literature. This strategy would complement recommendations that successful DRR ‘interventions’ are more likely to succeed if they can build on existing practices (Gianisa and Le De Citation2018) and that methodologies for developing DRRE should be participatory (UNICEF Citation2012). This is an important issue. Our findings show that the implementation of current DRRE programmes is not universal across the schools in our sample. This supports research in other countries showing that even where there are existing outreach and DRR educational initiatives, people commonly do not change their behaviours, beliefs or plans (Van Manen, Avard, and Martínez-Cruz Citation2015). This phenomenon is not confined to DDRE but is seen more generally. The ‘importation’ of extra-national approaches does not have a successful record of sustaining development within Indonesia (Allen et al. Citation2017). It is therefore important that interventions are developed within, and reflect, their cultural context (Tabulawa Citation2013; Budiyanto et al. Citation2017a). A rare example of this type of work at a local level used a community participatory approach to create and pilot a fun and engaging way to convey a disaster preparedness programme for young children by using song and dance as media of delivery, in the province of Aceh (Turnip et al. Citation2018). Although not focused on inclusion and access, the importance of fun emerged in overcoming barriers of uptake and implementation. This complements work in Indonesian kindergartens, where fun was found to be a key factor in teachers adopting an inclusive approach to storybooks (Rofiah et al. Citation2021b). Developing educational approaches that are fun would be in keeping with previous recommendations that new Indonesian DRRE pedagogies should offer an ‘effective and joyful approach’ (UNICEF Citation2012).

The participatory development of adult DRR initiatives has been an explicit goal in several international initiatives (Calgaro, Villeneuve, and Roberts Citation2020) and the need to involve children with SEND in a participatory approach to DRRE has been suggested in other countries (Seddiky, Giggins, and Gajendran Citation2020; Ronoh Citation2017) and there have been child-led DRR initiatives, albeit not with children with SEND (Wisner Citation2006; Benson Citation2007; Lu et al. Citation2021). This presents a challenge regarding how to support inclusive and accessible participatory research with children who are stigmatised within Indonesian society and often excluded from participation in education more generally (Murdianto and Jayadi Citation2020; Handoyo et al. Citation2021; Septian and Hadi Citation2021).

Conclusion

This research reveals the absence of children with SEND within DRRE research, evaluations, and school programmes in Indonesia. The findings show that there is a need for DRRE across mainstream, inclusive and special schools, and point towards the development of DRRE that has an inclusive pedagogy and is accessible for all children. Achieving this would be supported through participatory approaches that identify and build on existing good practices in schools, to create models of DRRE that are fun, engaging, and impactful for teachers and children.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (61.9 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kieron Sheehy

Kieron Sheehy researches within the field of inclusive education. Currently he is working on projects developing inclusive disaster risk reduction education, and understanding fun in learning.

Petra Vackova

Petra Vackova’s research is committed to issues of justice in education of young children, especially in relation to the arts. She has a keen interest in creative, post-qualitative methods and innovative methodologies

Saskia van Manen

Saskia van Manen works at the intersection of academic research and real-world practice to realise human-centred, sustainable and evidence-based disaster risk reduction initiatives. She holds a PhD in Volcanology, an MA in Product Design and Innovation and an M.Sci. in Geophysics.

Sherly Saragih Turnip

Sherly Saragih Turnip is a psychologist whose work addresses mental health. This includes using movement, songs and other fun activities with children and youth to positively impact on their understanding of, and response to, natural disasters.

Khofidotur Rofiah

Khofidotur Rofiah trains special education professionals and supervises educational research students. Her particular interests are developing the keyword sign system Signalong Indonesia and facilitating teachers’ competencies in inclusive education settings.

Alison Twiner

Alison Twiner is a research associate at the Open University and Hughes Hall, University of Cambridge. Her research interests focus on meaning making in the broadest sense, educational dialogue, and educational uses of digital technologies.

Notes

1 For a disaster to be included in the EM-DATA database at least one of the following criteria has to be met: (1) 10 or more people reported killed, (2) 100 or more people reported affected, (3) Declaration of a state of emergency and/or (4) Call for international assistance.

References

- ABC News. 2021. “Indonesia’s Latest Natural Disasters Are a ‘Wake-up Call’, Environmentalists Say -.” 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-01-22/indonesia-hit-by-series-of-disasters-in-the-first-weeks-of-2021/13075930.

- Allen, William, Mervyn Hyde, Robert Whannel, and Maureen O’Neill. 2017. “Teacher Reform in Indonesia: Can Offshore Programs Create Lasting Pedagogical Shift?” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education Online, 22–37. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2017.1355051.

- Amri, Avianto, Deanne K. Bird, Kevin Ronan, Katharine Haynes, and Briony Towers. 2017. “Disaster Risk Reduction Education in Indonesia: Challenges and Recommendations for Scaling Up.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 17 (4): 595–612. doi:10.5194/nhess-17-595-2017.

- Armitage, Andrew, and Diane Keeble-Allen. 2008. “"Undertaking a Structured Literature Review or Structuring a Literature Review: Tales from the Field Undertaking a Structured Literature Review or Structuring a Literature Review: Tales from the Field.” The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6: 103–114. . www.ejbrm.com.

- Awan, Ghulam Muhammad, Faisal Said, Juergen Hoegl, Louise McCosker, Siew Hui Liew, and Andreane Tampubolon. 2019. “Real-Time Evaluation Indonesia: Earthquakes and Tsunami (Lombok, Sulawesi) 2018,” no. January. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Indonesia_3.pdf.

- Benson, Lynn. 2007. “Lessons Learned from Child Led Disaster Risk Reduction Project - Thailand.”.

- Budiyanto, K. Sheehy, H. Kaye, and K. Rofiah. 2017a. “Developing Signalong Indonesia: Issues of Happiness and Pedagogy, Training and Stigmatisation.” International Journal of Inclusive Education. doi:10.1080/13603116.2017.1390000.

- Budiyanto, Kieron Sheehy, Helen Kaye, and Khofidotur Rofiah. 2017b. “Developing Signalong Indonesia: Issues of Happiness and Pedagogy, Training and Stigmatisation.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 1–17. doi:10.1080/13603116.2017.1390000.

- Budiyanto, Kieron Sheehy, Helen Kaye, and Khofidotur Rofiah. 2020. “Indonesian Educators’ Knowledge and Beliefs About Teaching Children with Autism.” Athens Journal of Education 7 (1): 77–98. doi:10.30958/aje.7-1-4.

- Bukar, Umar Ali, Marzanah A Jabar, Fatimah Sidi, Rozi Nor Haizan Nor, and Salfarina Abdullah. 2021. “Social Media Crisis Communication Model for Building Public Resilience: A Preliminary Study.” Business Information Systems July: 245–256. doi:10.52825/bis.v1i.55.

- Calgaro, Emma, Michelle Villeneuve, and Genevieve Roberts. 2020. “Inclusion: Moving Beyond Resilience in the Pursuit of Transformative and Just DRR Practices for Persons with Disabilities.” Natural Hazards and Disaster Justice: Challenges for Australia and Its Neighbours, 319–348. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-0466-2_17.

- Damyant, R. 2021. “Psikologi Krisis dan Bencana, Psikologi Krisis dan Bencana.” Accessed: 22 February 2022. https://elearning.radenintan.ac.id/course/info.php?id=1381.

- Dyregrov, Atle, William Yule, and Miranda Olff. 2018. “Children and Natural Disasters.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology, doi:10.1080/20008198.2018.1500823.

- Ediyanto, Ediyanto, Iva Nandya Atika, Norimune Kawai, and Edy Prabowo. 2017. “Inclusive Education in Indonesia from the Perspective of Widyaiswara in Centre for Development and Empowerment of Teachers and Education Personnel of Kindergartens and Special Education.” IJDS : Indonesian Journal of Disability Studies 4 (2): 04–116. doi:10.21776/ub.ijds.2017.004.02.3.

- Garcia Carrizosa, Helena, Kieron Sheehy, Jonathan Rix, Jane Seale, and Simon Hayhoe. 2020. “Designing Technologies for Museums: Accessibility and Participation Issues.” Journal of Enabling Technologies ahead-of-p (ahead-of-print). doi:10.1108/jet-08-2019-0038.

- Gianisa, Adisaputri, and Loic Le De. 2018. “The Role of Religious Beliefs and Practices in Disaster: The Case Study of 2009 Earthquake in Padang City, Indonesia.” Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 27 (1): 74–86. doi:10.1108/DPM-10-2017-0238.

- Global Education Cluster (GEC). 2012. “Disaster Risk Reduction in Education in Emergencies: A Guidance Note for Education Clusters and Sector Coordination Groups.” http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Disaster risk reduction in education in emergencies.pdf.

- Grant, Maria J, and Andrew Booth. 2009. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information and Libraries Journal, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

- Guha-Sapir, D., R. Below, and P. Hoyois. 2022. EM-DAT: The CRED/OFDA International Disaster Database – www.emdat.be – Université Catholique de Louvain – Brussels – Belgium.

- Ha, Kyoo Man. 2016. “Inclusion of People with Disabilities, Their Needs and Participation, into Disaster Management: A Comparative Perspective.” Environmental Hazards, doi:10.1080/17477891.2015.1090387.

- Handoyo, R. T., A. Ali, K. Scior, and A. Hassiotis. 2021. “Attitudes of Key Professionals Towards People with Intellectual Disabilities and Their Inclusion in Society: A Qualitative Study in an Indonesian Context.” Transcultural Psychiatry 50 (3): 379–391.

- Hasan Dawi, Amir, and Noor Aini Ahmad. 2019. “The Influence of Special Education Training on Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education: Case Study in Aceh Province.” Indonesia. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 8 (4): 1016–1027. doi:10.6007/IJARPED/v8-i4/6901.

- Indonesian National Agency for Disaster Management (BNPB). 2014. “Making School Safer from Natural Disaster.” Jakarta. Jl.Ir.H.Juanda No.36.

- Indriasari, Fika Nur, Linda Widyarani, and Prima Daniyati Kusuma. 2018. “Emergency Preparedness for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Yogyakarta.” Jurnal Keperawatan Soedirman 13 (3): 155. doi:10.20884/1.jks.2018.13.3.747.

- Karolinska Institutet. 2017. “Structured Literature Reviews.” Univerisity Library. 2017. https://kib.ki.se/en/search-evaluate/systematic-reviews/structured-literature-reviews-guide-students.

- Kelman, Ilan. 2019. “Axioms and Actions for Preventing Disasters.” Progress in Disaster Science 2: 100008. doi:10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100008.

- Lu, Yi, Lai Wei, Binxin Cao, and Jianqiang Li. 2021. “Participatory Child-Centered Disaster Risk Reduction Education: An Innovative Chinese NGO Program.” Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 30 (3): 293–307. doi:10.1108/DPM-03-2020-0066.

- Manen, Saskia Van, Geoffroy Avard, and Maria Martínez-Cruz. 2015. “Co-Ideation of Disaster Preparedness Strategies Through a Participatory Design Approach: Challenges and Opportunities Experienced at Turrialba Volcano, Costa Rica.” Design Studies 40 (August): 218–245. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2015.06.002.

- Mercy Corps. 2020. “The Facts: Indonesia Earthquakes, Tsunamis and Other Natural Disasters.” Mercy Corps. 2020. https://reliefweb.int/report/indonesia/facts-indonesia-earthquakes-tsunamis-and-other-natural-disasters.

- Mirzaei, Samaneh, Leila Mohammadinia, Khadijeh Nasiriani, Abbas Ali Dehghani Tafti, Zohreh Rahaei, Hossein Falahzade, and Hamid Reza Amiri. 2019. “School Resilience Components in Disasters and Emergencies: A Systematic Review.” Trauma Monthly 24 (5). doi:10.5812/traumamon.89481.

- Mubarak, A. F., R. Amiruddin, and S. Gaus. 2019. “The Effectiveness of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Training for the Students in Disaster Prone Areas.” In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Vol. 235. Institute of Physics Publishing. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/235/1/012055.

- Murdianto, M., and S. Jayadi. 2020. “Discriminative Stigma Against Inclusive Students in Vocational High School in Mataram, Indonesia.” International Journal of Multicultural and … 2015: 614–622. http://ijmmu.com/index.php/ijmmu/article/view/1325.

- Newman, Mark, and David Gough. 2020. “Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application.” In Systematic Reviews in Educational Research, 3–22. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7_1.

- Nikolaraizi, Magda, Vassilios Argyropoulos, Maria Papazafiri, and Christina Kofidou. 2021. “Promoting Accessible and Inclusive Education on Disaster Risk Reduction: The Case of Students with Sensory Disabilities.” International Journal of Inclusive Education, doi:10.1080/13603116.2020.1862408.

- Oliver, M. 2013. “The Social Model of Disability: Thirty Years On.” Disability and Society 28 (7): 1024–1026. doi:10.1080/09687599.2013.818773.

- O ‘Mara, Alison, Benedicte Akre, Tony Munton, Isaac Marrero-Guillamon, Alison Martin, Kate Gibson, Alexis Llewellyn, Victoria Clift-Matthews, Paul Conway, and Chris Cooper. 2012. “Curriculum and Curriculum Access Issues for Students with Special Educational Needs in Post-Primary Settings: An International Review.” Dublin. http://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Access_to_the_Curriculum_19_10_12-2.pdf.

- Oxfam. 2021. “5 Natural Disasters That Beg for Climate Action | Oxfam International.” Oxfam. 2021. https://www.oxfam.org/en/5-natural-disasters-beg-climate-action.

- Pertiwi, Pradytia, Gwynnyth Llewellyn, and Michelle Villeneuve. 2020. “Disability Representation in Indonesian Disaster Risk Reduction Regulatory Frameworks.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 45 (December 2019): 101454. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101454.

- Pham, Mai T., Andrijana Rajić, Judy D. Greig, Jan M. Sargeant, Andrew Papadopoulos, and Scott A. Mcewen. 2014. “A Scoping Review of Scoping Reviews: Advancing the Approach and Enhancing the Consistency.” Research Synthesis Methods 5 (4): 371–385. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1123.

- Proulx, Kerrie, and Frances Aboud. 2019. “Disaster Risk Reduction in Early Childhood Education: Effects on Preschool Quality and Child Outcomes.” International Journal of Educational Development 66 (April): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.01.007.

- Putera, R. E. 2018. “The Importance of Disaster Education in Disasterprone Areas Towards Disaster-resilient Indonesia.” INA-Rxiv Papers. doi:10.31227/osf.io/5p29t.

- Putri, Else Nungky Delisa. 2014. “PENDIDIKAN PENGURANGAN RISIKO BENCANA PADA ANAK PENYANDANG DISABILITAS UNTUK MENGURANGI KERENTANAN BENCANA DI SEKOLAH: SYSTAMTIC RIVIEW.” Paper Knowledge . Toward a Media History of Documents.

- Rahiem, Maila D.H., and Husni Rahim. 2020. “The Dragon, the Knight and the Princess: Folklore in Early Childhood Disaster Education.” International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 19 (8): 60–80. doi:10.26803/IJLTER.19.8.4.

- Rix, Jonathan, Helena Garcia-Carrizosa, Simon Hayhoe, Jane Seale, and Kieron Sheehy. 2020. “Emergent Analysis and Dissemination Within Participatory Research.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 44 (3): 287–302. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2020.1763945.

- Rofiah, Khofidotur, Kieron Sheehy, Sri Widayati, and Budiyanto. 2021a. “Fun and the Benefits of Sign Supported Big Books in Mainstream Indonesian Kindergartens.” International Journal of Early Years Education. doi:10.1080/09669760.2021.1956440.

- Rofiah, Khofidotur, Kieron Sheehy, Sri Widayati, and Budiyanto. 2021b. “Fun and the Benefits of Sign Supported Big Books in Mainstream Indonesian Kindergartens.” International Journal of Early Years Education Online Ear. doi:10.1080/09669760.2021.1956440.

- Ronoh, Steve. 2017. “Disability Through an Inclusive Lens: Disaster Risk Reduction in Schools.” Disaster Prevention and Management 26 (1): 105–119. doi:10.1108/DPM-08-2016-0170.

- Ronoh, Steve, J. C. Gaillard, and Jay Marlowe. 2015. “Children with Disabilities and Disaster Risk Reduction: A Review.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6 (1): 38–48. doi:10.1007/s13753-015-0042-9.

- Seddighi, Hamed, Homeira Sajjadi, Sepideh Yousefzadeh, Mónica López López, Meroe Vameghi, Hassan Rafiey, and Hamidreza Khankeh. 2021. “School-Based Education Programs for Preparing Children for Natural Hazards: A Systematic Review.” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness July: 1–13. doi:10.1017/dmp.2020.479.

- Seddiky, Md Assraf, Helen Giggins, and Thayaparan Gajendran. 2020. “International Principles of Disaster Risk Reduction Informing NGOs Strategies for Community Based DRR Mainstreaming: The Bangladesh Context.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 48 (April 2019): 101580. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101580.

- Septian, Eriando Rizky, and Ella Nurlaella Hadi. 2021. “Reducing Stigma of People with Disabilities: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Medical and Health Studies 2 (2): 31–37. doi:10.32996/jmhs.2021.2.2.3.

- Sheehy, K., and Budiyanto. 2015. “The Pedagogic Beliefs of Indonesian Teachers in Inclusive Schools.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 62 (5). doi:10.1080/1034912X.2015.1061109.

- Sheehy, K., H. Garcia-Carrizosa, J. Rix, J. Seale, and S. Hayhoe. 2019. “Inclusive Museums and Augmented Reality: Affordances, Participation, Ethics, and Fun.” International Journal of the Inclusive Museum 12 (4), doi:10.18848/1835-2014/CGP/v12i04/67-85.

- Shoji, Masahiro, Yoko Takafuji, and Tetsuya Harada. 2020. “Behavioral Impact of Disaster Education: Evidence from a Dance-Based Program in Indonesia.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 45 (August 2019). doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101489.

- Stough, Laura M., and Donghyun Kang. 2015. “The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and Persons with Disabilities.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6 (2): 140–149. doi:10.1007/s13753-015-0051-8.

- Sunardi, Sunardi, Mucawir Yusuf, Gunarhadi Gunarhadi, Priyono Priyono, and John L. Yeager. 2011. “The Implementation of Inclusive Education for Students with Special Needs in Indonesia.” Excellence in Higher Education 2 (1): 1–10. doi:10.5195/ehe.2011.27.

- Tabulawa, R. 2013. Teaching and Learning in Context: Why Pedagogical Reforms Fail in Sub-Saharan Africa. Dakar, Sengal: Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa.

- Torani, Sogand, Parisa Majd, Shahnam Maroufi, Mohsen Dowlati, and Rahim Sheikhi. 2019. “The Importance of Education on Disasters and Emergencies: A Review Article.” Journal of Education and Health Promotion 8 (1): 85. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_262_18.

- Turnip, Sherly Saragih, Karina Adistiana, M. Psi, and Drs Ribut Cahyono. 2018. “Finding A Fun and Engaging Media to Deliver Disaster Preparedness Messages for Younger Children in Indonesia.” International Conference on School’s Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience Education in Practice. - TW, Taipei, Taiwan, Province of China, 1–12.

- UNICEF. 2012. Disaster Risk Reduction in School Curricula. Disaster Risk Reduction in School Curricula: Case Studies from Thirty Countries. UNESCO and UNICEF. http://www.unicef.org/education/files/DRRinCurricula-Mapping30countriesFINAL.pdf.

- USAID. 2021. Disability Inclusive Get Ready Guidebook.

- Wisner, B. 2006. Knowledge in Disaster Risk Reduction. In ISDR System Thematic Cluster/ Platform on Knowledge and Education. Geneva.

![Figure 2. Distribution of questionnaire respondents. [Map data ©2021 Google, INEGI].](/cms/asset/8aced126-b293-4cee-940b-cd7fafca2a84/tied_a_2115156_f0002_oc.jpg)