ABSTRACT

Providing quality education for all pupils requires cooperation from members of the entire school community. One group of professionals is school assistants, who, together with teachers, play an important role in supporting pupils and inclusive education. Due to pupils’ diverse needs, the responsibilities of school assistants in schools have broadened; yet, their role in the school community has rarely been studied. This study focuses on school assistants’ experiences and addresses the following research question: How is belonging argumented in school assistants’ narratives at their work? The data comprise free writings (N = 52) and interviews (N = 9) of school assistants’ work. The narratives are analysed using categorical-content analysis. The results yield three experiences of belonging: stories of belonging, stories between belonging and non-belonging and stories of non-belonging. The study data reveal how a school as an institution can be based on conventional practices, where relationships are often formed through hierarchies, old-fashioned work roles and exclusive meeting policies. The study’s conclusion encourages the recognition of structural inequalities in school communities.

Introduction

Providing quality education for all pupils and promoting inclusion requires cooperation between staff and involves interdependencies whereby structural, social, and emotional dimensions are interlinked (Nikula, Pihlaja, and Tapio Citation2021). In this study, inclusion is seen as appreciation and respect for all people in the community. It is the process of improving participation in society, particularly for people who are disadvantaged, by enhancing opportunities and enabling access to resources (United Nations Citation2016). The definition of inclusion can be found by reflecting on Professor Slee’s (Citation2001, 116) questions: Who’s in? and Who’s out? In the answer, we can find the reasons or factors that limit participation and belonging. Inclusion is about removing barriers to participation.

Kovač and Vaala (Citation2021) argue that the idea of inclusion is not a straightforward process where people simply belong to various social settings. It is important to notice that people regularly identify, categorise and evaluate placing themselves and others automatically in ‘in-groups’ and ‘out-groups’. People are thus selective when it comes to personal relations and social attachments. However, belonging can be seen as closely related to the concepts of inclusion and exclusion (Antonsich Citation2010; Kovač and Vaala Citation2021; Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2016). Belonging can function as a resource that constructs, claims, justifies or resists socio-spatial inclusion and exclusion (Antonsich Citation2010). Belonging can be viewed from at least two perspectives: the sense of belonging and politics of belonging (Antonsich Citation2010; Yuval-Davis Citation2006), to which we return later.

Belonging is an important concept when working as a team member in a school (Jardí, Petreñas, and Puigdellívol Citation2022). Removing learning barriers and providing quality education for all pupils with different support needs requires close cooperation from members of the entire school community (Bennett et al. Citation2021; Saloviita Citation2020). One group of professionals working at school with teachers are school assistants, also called paraprofessionals, educational assistants, special-needs assistants, teaching assistants or learning mentors (Köpfer and Böing Citation2020; Zhao, Rose, and Shevlin Citation2021). The terms used vary among countries (Lederer, Breyer, and Gasteiger-Klicpera Citation2021). This article uses the term school assistant, which refers to an educated person who works in a school with the main task of assisting all pupils, including those with special needs. School assistants, together with teachers, play an important role in supporting pupils and inclusive education (Bennett et al. Citation2021; Finnish Basic Education Act Citation826/Citation1998; Lakkala et al. Citation2021; Lederer, Breyer, and Gasteiger-Klicpera Citation2021; Saloviita Citation2020; Zhao, Rose, and Shevlin Citation2021). Recently, the number of school assistants has grown both internationally and in Finland due to the increased number of students with special needs ( Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016; O’Connor et al. Citation2021).

Bennett et al. (Citation2021) revealed that successful cooperation between teachers and school assistants requires planning and seeing the teacher and school assistant as a team. In her research, Takala (Citation2005, Citation2007) found that the teacher and school assistant seldom have a common planning time or an agreed work division. These results were supported by Riitaoja (Citation2013), who showed that school assistants’ possibility of being heard is lower than that of other school professionals, which indicates their low status. Conboy (Citation2021), in turn, noted that lower status might also affect opportunities to receive information. Sometimes, school assistants are not seen as important professionals in delivering information about pupils’ education. In addition to these information flow challenges, school assistants often experience violence or threats in their work (Bruckert, Santor, and Mario Citation2021; Finnish Institute of Occupational Health Citation2021).

Due to pupils’ diverse needs, school assistants’ responsibilities in schools have broadened (Bennett et al. Citation2021; Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016). Nevertheless, too little attention has been paid to the school assistants’ role and status in the school community (Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016; O’Connor et al. Citation2021). In this study, we focus on school assistants’ experiences and how they describe belonging at their work. The results are reviewed through the theory of politics of belonging (Yuval-Davis Citation2006). In the Finnish context, school assistants’ work has seldom been studied. So far, school assistants’ work in schools has not been studied internationally in the context of politics of belonging. Nevertheless, the curriculum and politics of belonging have been studied, and the central role of belonging in education has been proven (Piškur et al. Citation2021).

Politics of belonging

Belonging and connection to others form an important part of the wellbeing of every human being, and a lack of belonging and attachment induces multiple negative effects on health (Baumeister and Leary Citation1995). Belonging can be defined as emotional attachment, feeling at home and feeling safe (Antonsich Citation2010; Yuval-Davis Citation2006). However, Lähdesmäki et al. (Citation2016) argued that although the concept of belonging is person-centred, it does not refer only to individual feelings but comprises both emotions and external relations. It also includes a political aspect and relation to the norms, restrictions and regulations that enable or hinder belonging (Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2016). The politics of belonging can be traced to legislation and regulating documents (Yuval-Davis Citation2006).

Yuval-Davis (Citation2006) uses the concept ‘politics of belonging’, which describes belonging as a relational, multilevel and dynamic phenomenon. She shared belonging to three main inter-related analytical levels in which politics of belonging is constructed as (1) social locations, (2) individuals’ identifications and attachments to various collectivities and groupings and (3) ethical and political value systems. Level 1 refers to categories such as age group, gender, race, profession and economic locations. However, many of these categories also have a position in the power axel (Yuval-Davis Citation2006). Level 2 constructs people’s narratives about themselves and others, and about who they are and who they are not. Often, these stories tell what it means to be part of a certain group or collectivity (Yuval-Davis Citation2006, Citation2010). Level 3, ethical and political values, combines different levels and refers to how these levels are valued and judged and how boundaries are drawn in society (Yuval-Davis Citation2006).

Belonging is bound up with everyday practices, which are often taken for granted and can be unconscious (May Citation2011). According to Yuval-Davis (Citation2006, 204), the politics of belonging ‘is all about potentially meeting other people and deciding whether they stand inside or outside the imaginary boundary line of the nation and/or other communities of belonging, whether they are “us” or “them”’. Membership (to a group) and ownership (of a place) are the key factors in the politics of belonging, and if one feels rejected or not welcomed to a group, their sense of belonging would inevitably be spoiled (Antonsich Citation2010).

Kuurne and Vieno (Citation2021) further developed the concept of belonging and studied belonging in the work community by using the concept of ‘belonging work’. They conceptualised belonging work as relational work concerned with shaping situational interactions, networks of relationships and social boundaries and materials as dimensions of belonging. According to Kuurne and Vieno (Citation2021), belonging work actively shapes social relationships and practices, which can be done intentionally, routinely or even subconsciously. Some workers belong almost automatically in workplaces, while others have to work hard to achieve belonging. Some workers are not even in a position to try to achieve belonging if their social position has been pre-stigmatized and marginalised. The concept of belonging work not only turns the gaze towards what actors do to accomplish belonging but also sensitises us to the structural inequalities at various workplaces (Kuurne and Vieno Citation2021).

School assistants’ education and work

School assistants have various vocational education levels, and the legal regulations defining their duties vary throughout Europe (Lederer, Breyer, and Gasteiger-Klicpera Citation2021). In Citation2010, the Finnish National Board of Education confirmed further vocational qualifications for school assistants who often work as instructors in morning and afternoon activities before or after school days. The examination of school assistants is a competence-based qualification. Before the examination, many students complete a year of education for work as a school assistant. Despite this examination, there are no legal qualification requirements for school assistants working in Finland, and each community can define its qualifications when hiring school assistants (Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016).

School assistants work in schools as either personal or class-specific assistants. Several school assistants can also work in the same class, depending on the support required by the students (Takala Citation2016). In the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (Finnish National Board of Education Citation2016, 74), school assistants’ job description is defined as follows: ‘The assistant guides and supports the pupil in carrying out learning and schooling tasks in daily situations as directed by the teacher or other support professionals’. Takala (Citation2005, Citation2007) found in her study that school assistants’ work in Finland includes various tasks, such as assisting pupils, assisting teachers, guiding small groups or individual students according to the teacher’s instructions, carrying out basic treatment and guiding pupils’ behaviour.

A school assistant holds the position of an employee in relation to the teacher (Conboy Citation2021; Riitaoja Citation2013), and there is a professional boundary between the teacher and school assistant (Paju Citation2021). However, sometimes the blurred roles between teachers and school assistants can result in unclear situations. For example, disciplinary responsibilities (Webster and Blatchford Citation2014) are often transferred to an assistant from the teacher. Previous studies (Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016; Jardí, Petreñas, and Puigdellívol Citation2022; Wiggs et al. Citation2021) have shown that school assistants in Finnish schools and abroad often receive the role of discipline-keeper at class to provide the teacher a peaceful environment to teach. Some studies (Paju et al. Citation2016; Sharma and Salend Citation2016; Yates et al. Citation2020) have also shown that responsibilities in planning and teaching increase, especially when school assistants work as personal assistants for one pupil. However, school assistants do not have pedagogical or disciplinary responsibility in their work profile in Finland or internationally (Paju Citation2021; Sharma and Salend Citation2016; Webster and Blatchford Citation2014).

Paju and colleagues (Citation2016) described that school assistants get used to adapting to varying situations, which can be called ‘moment-to-moment pedagogy’. Everyday school situations include many complex issues. However, if the teacher and school assistant do not have a common vision of what to demand from pupils, the school assistant might feel uncertain about handling the situation. School assistants, who often also follow pupils during breaks, see pupils in situations that teachers never do. This means that assistants have more opportunities to face pupils individually than the teacher, who is responsible for the whole class and for the fulfilment of the curriculum goals (Paju et al. Citation2016).

The (Finnish) school assistants’ situation in schools is contradictory. On one hand, they are seen as an important part of the school system, and on the other hand, they seldom participate in planning and are outsiders in many situations (Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016). Moreover, their tasks at school are still unclear to themselves and to the teachers, and the tasks vary considerably from assisting roles and teacher-type duties (Jardí, Puigdellívol, and Petreñas Citation2021; Paju Citation2021) to a person supporting inclusive education (Zhao, Rose, and Shevlin Citation2021). Low salary and work suspension for the summer are also problematic for school assistants and show an understatement internationally (Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016; Zhao, Rose, and Shevlin Citation2021).

For these reasons, it is important to determine school assistants’ experiences in the school community. The present study explores school assistants’ role and belonging in the school community using the theory of politics of belonging (Yuval-Davis Citation2006, Citation2010) as a framework for review. Political values, social locations, identifications and emotional attachment affect belonging. Therefore, we primarily focus on school assistants’ experiences and address the following research question: How do Finnish school assistants describe belonging at their work?

Materials and methods

The data comprised two different materials: free writings and interviews of school assistants’ work, which were obtained through Facebook’s closed Finnish School Assistants group in the spring of 2021. The Facebook group had 4753 members, of which 77 school assistants responded. The link to the query was shared in the group, and the participants were asked to write and share their work experiences. The school assistants were provided with the following questions to help them start writing: What kind is your workday and what does it all entail? What types of thoughts and feelings does your work evoke? What type of work community are you working in, and how does it influence the way you work? A possibility to sign up for an interview was also an option if writing was a challenge or if the participants preferred to share their experiences. In addition, the respondents were asked four background questions: What school level are you working at? Are you working in a special school? Do you have an education for work as a school assistant? How long have you been working as a school assistant?

The first researcher who gathered the data and interviewed participants had worked before as a special education teacher. She had prior knowledge of the work of school assistants, which could be seen especially during the interview. However, an effort was made to deliberately eliminate the effect of previous knowledge.

Writings about school assistants’ work

From the writings, we analysed the answers of the school assistants who had five to twenty years or more of work experience. We excluded those who did not work in compulsory education and those who had only recently started working as assistants. Within this framework, we received 52 responses. The length of the writings varied from a few lines to half a page of text.

Almost all the school assistants (N = 50) held school assistants’ work qualifications. Most respondents worked in a pre- or primary school (), working both in general and special education, often part of the day in general and part in special education. Nine (N = 9) school assistants worked in special schools.

Table 1. School level of assistants who responded to the questionnaire.

Interviews

Fifteen school assistants participated in the interviews. The recorded theme interviews were conducted in May 2021 through phone or videoconferencing (due to Covid-19 restrictions) as preferred by the participants. The following themes were used: personal work history, basic information of current school, description of a normal workday, job-related tasks at school, challenges and possibilities at work and possible collaboration in school. The total duration of the interviews was 4 h and 20 min, with each interview lasting approximately 30 min. The data amounted to 62.5 pages of transcriptions (Times New Roman 12, spacing 1).

We chose nine interviewees for this study (). We excluded school assistants who worked in a hospital school or university training school and those who were not currently working. We focused on compulsory education, and interviewees with more than five years of experience were accepted.

Table 2. Background information on the nine interviewed school assistants.

Analysing the data

In this qualitative study, the researchers understood the materials (i.e. writings and interviews) as a narrative through which participants share their experiences of school assistants’ work. According to Baumeister and Newman (Citation1994, 676), people’s efforts to understand their experiences often construct narratives (stories) out of them. People create narrative descriptions for themselves and for others about their past actions and develop storied accounts that give sense to the behaviour of others (Hännikäinen Citation2008; Polkinghorne Citation1988). Narratives describe aspects of individual experiences, emotions and thoughts (Baumeister and Newman Citation1994; Holstein and Gubrium Citation2012; Polkinghorne Citation1995). However, the stories are usually constructed around a core of facts or life events yet allowing wide freedom of individuality and creativity in the selection, addition to, emphasis on, and interpretation of these ‘remembered facts’. (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber Citation1998).

The perception of the materials as a narrative is also related to the theory of the politics of belonging (Yuval-Davis Citation2006), because one level of belonging focuses on how people describe themselves and others. Often, these stories describe what it means to be part of a certain group. As individuals tell their stories, they are not independent of the context. In contrast, the individuals in question are irreducibly connected to their social, cultural and institutional settings (Holstein and Gubrium Citation2012; Moen Citation2006).

In this study, all data, both from interviews and the writings, were analysed using categorical-content analysis (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber Citation1998), also called content analysis. According to Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber (Citation1998), content analysis is a classical method for analysing narrative materials. Before the actual analysis, all three researchers read the data independently as a whole and then explored how belonging was discussed (if discussed) in the writings and interviews. This is called ‘the holistic reading approach’ (van Manen Citation1990). The responses included many materials about collaboration, working alone, belonging and non-belonging. After reading all received materials, the final research question was formulated through discussions.

For the second phase, we selected the subtext in which the above-named themes were discussed. The researchers read the text again independently by breaking it into relatively small content units (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber Citation1998). The basic unit of analysis was a sentence, description of a meaningful event, an idea or an emotional experience (Vetoniemi and Kärnä Citation2019); these units were discussed together. According to Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber (Citation1998), researchers’ collaboration creates higher sensitivity to the text and its meaning. Through this phase, the researchers found similarities and differences among the materials, and the preliminary themes showed that belonging and non-belonging were represented in the data. A closer look at these themes showed that they included eight sub-themes: school culture, information flow, cooperation, hierarchies among staff members, blurred work descriptions, appreciation, vocation for the work and meaning/importance/role/relation to/of pupils. Based on these themes and sub-themes, the researchers constructed stories of school assistants’ belonging to the school community. After constructing the stories, the researchers looked at them through the chosen theoretical background.

Results

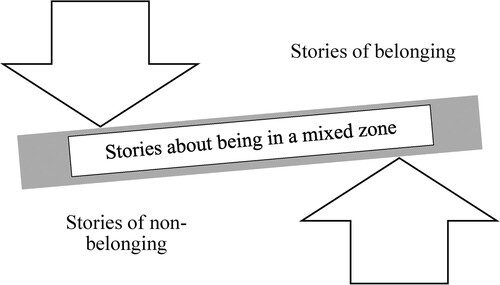

The eight sub-themes can be seen through belonging and non-belonging. In addition, there was an area in-between them, about being in a mixed zone, whose final situation could turn into either belonging or non-belonging. This is why the results are presented in three parts: those representing belonging to the school community, those in the in-between areas, and those representing the opposite (i.e. experiences of non-belonging) (). We call these three different views ‘stories’, which are now open. These stories described the school assistants’ work, position and experience of belonging in a school community. Underlying these three stories, it was possible to notice the three interrelated levels: social locations, identifications and attachments, and ethical and political value systems (Yuval-Davis Citation2006). In some stories, they had a major impact, and minor in others. Sometimes, the quotes are shortened with … to protect the participant’s anonymity.

Stories of belonging

The stories of belonging describe an ideal situation in which a school assistant is a valued employee and an important school community member. Membership is one of the key factors in the politics of belonging (Yuval-Davis Citation2006). The school assistants, together with the teachers, were supporters of pupils and collaborators in inclusive education (Lakkala et al. Citation2021; Lederer, Breyer, and Gasteiger-Klicpera Citation2021). The school assistants’ stories of belonging brought out the stories which tell what it means to be a part of a certain collectivity (see Yuval-Davis Citation2006). A major factor affecting the sense of belonging experienced by Finnish school assistants was that the school principal and teachers trusted them and appreciated their work. Therefore, they could propose their ideas and implement them freely. Julie described her situation as follows:

Preventing bullying, this small campaign for the 6th graders … I also include social media and have a small campaign … I can implement my own thoughts and ideas, as I don’t need to think that we do just what the teacher says. I find this to be a job where I can use my creativity.

Some schools emphasised the equality of staff members, and the name of the teachers’ room was changed to staffroom. Through this name change, efforts were made to reduce the division of staff members into different professional categories and remove the division between ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Yuval-Davis Citation2006). Sense of community was highlighted by a school assistant’s statement about how the whole work community ‘pulled together’ (text 8). The staff members had a clear vision that the whole school community works together and that no one is left working alone. This attitude helped the assistants’ work with challenging pupils, because support was available for their work. The schools’ everyday practices are important shapers of belonging (Kuurne and Vieno Citation2021) and in these schools, the practices had been intentionally made to enhance cooperation.

Cooperation, open interaction between a school assistant and teacher and the feeling of being a valued member of the class team were important for belonging. Moreover, daily interaction ensured the flow of information about the school and class happenings. The school assistants described how easy collaboration with teachers was and felt as part of the class team.

We have a team meeting every week with teachers, school assistants and special education teachers. In our work community, everyone’s work is valued, and there is a strong focus on teamwork. I think it is important that we can work as one team. I get a lot of strength from my work community for my daily work. We have a very relaxed, open and encouraging atmosphere. (text 21)

In some stories of belonging, a somewhat blurred work description between teachers and school assistants was the reality. Among other things, the school assistants said they were planning and teaching students, although teaching should not be part of their work (Paju Citation2021; Webster and Blatchford Citation2014). Acting as a teacher seemed to reinforce the school assistants’ experience of belonging.

Stories about being in a mixed zone

The stories about being in a mixed zone revealed how blurry one’s position in the school community could be and how the experience could change according to the situation, work practices, people and professional title. As Nina explained, even ambiguity in the professional title increased uncertainty about one’s place.

Well, for example, if the name we are called would be the same. We are called assistants, helpers, school helpers, supervisors and so on, so sometimes I wonder that I do not belong to any caste.

In staff meetings, artificial participation and belonging were experienced at the institutional school level, as only one school assistant could participate. Their responsibility was to inform others about the issues discussed in the meetings. This caused challenges in information flow and was experienced as an unequal way of decision-making. Exclusion from meetings can also be interpreted as a lack of appreciation (Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016) or as a sign of routine practices (Kuurne and Vieno Citation2021) that produce inequalities among professionals. Having only one school assistant in a meeting was explained by the meetings being held when the school assistants had to be in another place (e.g. on a break with pupils). In addition, the school assistants’ short work hours limited their participation in meetings. In many cases, they had no opportunity to be heard at all, as Nina said in her interview:

We will not be able to participate (in meetings). One school assistant will attend, and she reports all the key information in the school assistants’ WhatsApp group.

Well, what if there are situations where the school assistants should give their opinion of something?

Have never been asked any opinion.

Some teachers showed their appreciation, and the cooperation was smooth. However, many school assistants experienced that the principals often tried to break down existing hierarchies. The principals and administrators were told to have an important role in supporting the school assistants’ work and position, as well as in promoting teacher cooperation in the school community (Biggs, Gilson, and Carter Citation2016).

Collaboration with the teachers at the class level was often experienced as rewarding, especially in situations where a teacher and school assistant worked together and had a regular meeting time during which the teacher discussed upcoming issues and pupils with the assistant. Rachel said,

We always have a meeting every Monday when the pupils have left home. So then we hear if there is anything extra coming up. And if the teacher has any written statements (related to three-tiered support), which always need to be made, she usually gives them to us to read. And if we disagree on something, we can tell her.

If the school assistants worked with several teachers in both primary and secondary schools, their experiences of belonging varied. Some teachers indicated a hierarchy between their positions and those of the school assistants, reducing their sense of belonging. Moreover, some teachers, especially in secondary schools, did not know the school assistants’ work descriptions; thus, they did not know how to work with them.

I think that special educators really understand the value of school assistants, but subject teachers in general classes do not. They do not understand how the assistant could be useful in lessons, and they feel they manage without an assistant. In practice, I have noticed at least in one case … that the presence of the assistant might have softened the symptoms of one pupil. I like my job, and I experience it important, but I have noticed that the attitudes of some teachers make me feel inferior. (text 42)

Stories about non-belonging

In some stories, the work of school assistants was neither valued nor recognised by teachers or even principals. These stories tell about being ignored and marginalised from the community, where the school assistants’ work description was unclear for most teachers and for some school assistants themselves. There were clear boundaries between the school staff (Yuval-Davis Citation2006) which could not be crossed. The school assistants felt like ‘a dog’s body’ (text 23) that could be assigned any task in the school at any time. Some school assistants thought they were responsible for all work, from making coffee, copying papers, helping the teacher and often teaching. Sometimes, they felt that they were assistants for the teachers, not the pupils. However, school assistants’ work focus should be on pupils (Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014).

The challenges of information flow showed underestimation of the profession in the opinion of school assistants. As a result, school assistants were excluded from class and school staff meetings. Interruptions in information flow were common, and the school assistants said that they had to constantly ask what was happening and that they heard much essential information from the pupils. This led to a strategy in which they operated according to the prevailing situation, as Ann explained:

I never know what will happen. I know when all different issues will happen. When I go to work in the morning. I see, well, we do not have this, but we have a special day. I never know. I receive no letters or messages which the parents and pupils get.

There were also stories about jealousy and competition among the school assistants. Some school assistants said that they could not trust collegial support. They did not receive support from each other, even when facing a violent pupil, which affected their coping at work. In addition, some assistants talked about competition among the school assistants regarding their positions in class.

In my current job … I am often left outside, as the teachers and the other assistant have acted as a pair in their previous school. I am often forgotten and receive information suddenly. The other assistant is afraid of a violent pupil, and that's why it is me who … . The other assistant turns a blind eye and does not come to help. I have acted as a barrier so the kick does not catch the teacher. I am beginning to get exhausted in my current job. (text 13)

These stories of ignoring and non-belonging included experiences of burnout and thoughts about changing their careers. Neither the structures created at the school nor the school staff supported the school assistants in their work. The next quote concludes with the school assistants’ experience of non-belonging:

Some teachers value us, but for some teachers, we are just jerks who can only copy papers. Often, these teachers see the school assistant as their personal assistant … The salary is ridiculous … during the summer, no salary. We are an excluded worker category who do not participate in any everyday planning nor groups. Legally, we do not exist. No right to keep discipline, but on the other hand, no responsibility of anything. (text 3)

Nevertheless, these three stories have something in common. Even if the school assistants felt non-belonging to the school community, they also felt that the pupils were at the core of their work. All three stories involved the school assistants’ narratives of how they ‘love’ their work due to the pupils. Supporting pupils was the reason behind their work, although there were several challenges, often with adults and the school culture. These challenges led to feelings of inferiority and worthlessness. Nevertheless, most school assistants felt that they belonged to pupils.

Discussion

In Finland as well as internationally school assistants are important persons in supporting inclusive education in schools (Bennett et al. Citation2021; Finnish Basic Education Act Citation826/Citation1998; Lakkala et al. Citation2021; Lederer, Breyer, and Gasteiger-Klicpera Citation2021; Saloviita Citation2020; Zhao, Rose, and Shevlin Citation2021). In this study, inclusion has been seen as a broad concept as the process of improving participation in society for all people who are disadvantaged, through enhancing opportunities, voice and respect for rights (United Nations Citation2016). We see that belonging can function as a resource that constructs, claims, justifies or resists inclusion and exclusion (Antonsich Citation2010; Kovač and Vaala Citation2021). In this qualitative research, we wanted to find out Finnish school assistants’ own views on belonging with the question: How do school assistants describe belonging at their work? The theoretical basis was provided by the theory of the politics of belonging (Yuval-Davis Citation2006).

In this study, the experience of Finnish school assistants’ belonging was divided into three parts: stories of belonging, being in a mixed zone and non-belonging. The three levels of the politics of belonging (social locations, identifications and attachments, ethical and political value systems, see Yuval-Davis Citation2006) influenced school assistants’ belonging. In the stories, the school assistants’ social location and identification changed. In stories of belonging, school assistants were a valuable part of the entire school community. The stories of being in a mixed zone talked about being between belonging and non-belonging. Some partially belonged to their class team or to other school assistants’ groups, but they did not feel like being a member of the whole school community or member of the class team, but they were longing for it. Hierarchies between teachers and school assistants, but also between some assistants existed in these stories. Some school assistants did not feel that belonging was important – they were ‘just doing their job’. The concept of belonging also comprises the possibility of non-belonging (Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2016). However, most school assistants experienced belonging in relation to their pupils, and the pupils were the reason why they worked as school assistants (also Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016). The belonging was experienced in different relationships within the school context and was bound up with everyday practices (May Citation2011). In this study, belonging comprised experiences of being recognised as a community member and being part of us (the school staff), not outsiders (Yuval-Davis Citation2006).

The external factors (ethical and political value systems) affected a school assistant’s work and belonging. The indeterminacy of the professional image of school assistants in Finnish law contributed to the ambiguity of the job description. Political systems and values affected, for example, school assistants’ employment contracts and possibilities to participate in, for example, school meetings.

This study has several limitations. It has a strong regional focus and thus it cannot be directly transferred to another school system. The data were gathered from a Finnish Facebook group for assistants in which the first researcher was one of the members. When applying for membership in the group, the researcher openly told administrators of her intention to conduct the study through this Facebook group. Also, the participants were informed about the purpose and data protection of the study. We assume that collecting data in a group limited the number of participants. Perhaps only the most active school assistants responded. In the future, one could do participatory ethnographic research for a certain period, thus catching up better with everyday life. Many school assistants are busy and tired and not able to answer the questionnaire or participate in interviews. The voices of teachers, principals and pupils remained unheard in our study. However, the study results agreed with the previously obtained results (e.g. Conboy Citation2021; Eskelinen and Lundbom Citation2016; Zhao, Rose, and Shevlin Citation2021), highlighting the instability of the role of school assistants in school.

The study data revealed how a school as an institution can be based on conventional practices, where relationships are often formed through hierarchies, old-fashioned work roles and exclusive meeting policies. Although people identify and categorise others and themselves automatically creating belonging and non-belonging (Kovač and Vaala Citation2021) this study encourages the recognition of structural inequalities and exclusion of certain professional groups in school communities. When multi-professional work is studied, issues related to identity, power, territory and expertise are relevant and need to be discussed (Rose Citation2011). The analysis therefore suggests that schools as institutions need to develop collaborative, social and pedagogical skills of the staff if they wish to promote belonging and, through it, inclusion. The achievement of belonging and inclusion is an active process (Ainscow and Messiou Citation2018; Kovač and Vaala Citation2021; Kuurne and Vieno Citation2021). However, the role of staffs’ belonging in supporting inclusion in schools has been less explored and via this study, we also want to bring out this question. Can the school be inclusive if there is an exclusive work practice, and the staff do not belong?

In the future, the school assistant’s role in a school, especially in collaboration with a teacher, needs to be clarified at the Finnish policy level. The responsibilities of school assistants and the information they require to work also need to be clarified. The importance of school assistants in an inclusive school has been proved, and cooperation between teachers and school assistants should be taught and practised in teacher education both in Finland and internationally. Also, the meaning of belonging to the staff in supporting inclusion should be discussed internationally.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture for financing the HOHTO project.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

R. Sirkko

Riikka Sirkko, PhD, works as a university lecturer in special education at the University of Oulu. Before her university career, she worked for several years as a special education teacher in a primary school. Her research interests focus on inclusive education at all educational levels and the education of pupils with intellectual disabilities. She is currently participating in HOHTO, a joint research and developmental project with six universities in Finland that aims to develop teacher education. The Ministry of Education and Culture finances it

K. Sutela

Katja Sutela, PhD, is a university lecturer in music education at the University of Oulu. Before her university career, she taught music to children with special needs for 10 years in a special education school. Her research interests focus on marginalised individuals and communities, theories of embodiment and music education. She is also an active singer-songwriter and has released two albums. She is currently participating in the HOHTO project

M. Takala

Marjatta Takala, works as a professor of special education at the University of Oulu, Finland. Her research interests include special and comparative education, inclusion, curriculum design, hearing impairment and teachers’ professional development. She is currently participating in the HOHTO project. She is also a research partner in two projects with Umeå University in Sweden, one studying inclusion in sport associations and the other focusing on the internationalisation of higher education. She has edited several books related to special education, with the latest about inclusion in Finland.

References

- Ainscow, M., and K. Messiou. 2018. “Engaging With the Views of Students to Promote Inclusion in Education.” Journal of Educational Change 19: 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10833-017-9312-1.

- Antonsich, M. 2010. “Searching for Belonging – An Analytical Framework.” Geography Compass 4 (6): 644–659. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.x.

- Baumeister, R. F., and M. R. Leary. 1995. “The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation.” Psychological Bulletin 117 (3): 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

- Baumeister, R. F., and L. S. Newman. 1994. “How Stories Make Sense of Personal Experiences: Motives That Shape Autobiographical Narratives.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20 (6): 676–690. doi: 10.1177/0146167294206006

- Bennett, S., T. Gallagher, M. Somma, and R. White. 2021. “Transitioning Towards Inclusion: A Triangulated View of the Role of Educational Assistants.” Journal of Research Special Educational Needs. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12508.

- Biggs, E. E., C. B. Gilson, and E. W. Carter. 2016. “Accomplishing More Together: Influences to the Quality of Professional Relationships Between Special Educators and Paraprofessionals.” Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 41 (4): 256–272. doi:10.1177/1540796916665604.

- Bruckert, C., D. Santor, and B. Mario. 2021. In Harm’s Way: The Epidemic of Violence Against Education Sector Workers in Ontario. The University of Ottawa. http://educatorviolence.net/.

- Conboy, I. 2021. “‘I Would Say Nine Times out of 10 They Come to the LSA Rather Than the Teacher’. The Role of Teaching Assistants in Supporting Children’s Mental Health.” Support for Learning 36: 380–399. doi:10.1111/1467-9604.12369.

- Eskelinen, T., and P. Lundbom. 2016. “Koulunkäynninohjaajat: itseymmärrys ja kamppailu merkityksestä.” [School Assistants: Self-Understanding and Struggle for Meaning]. Kasvatus ja aika 10 (4): 44–61. http://www.kasvatus-ja-aika.fi/dokumentit/a3_1601171059.pdf.

- Finnish Basic Education Act. 826/1998. https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1998/en19980628.

- Finnish Institute of Occupational Health. 2021. Työelämätieto. Kunta-alan työ ja työhyvinvointi. Työstressi ja väkivalta ammattialoittain [Working life information. Municipal Work and Well-Being at Work. Work-Related Stress and Violence by Profession]. https://www.tyoelamatieto.fi/#/fi/dashboards/kunta10.

- Finnish National Board of Education. 2010. Koulunkäynnin, aamu- ja iltapäivätoiminnan ohjaajan ammattitutkinto [Further Vocational Qualification for School Assistants and Instructors in Morning and Afternoon Activities]. https://eperusteet.opintopolku.fi/#/fi/esitys/216546/naytto/tiedot.

- Finnish National Board of Education. 2016. Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf.

- Hännikäinen, V. 2008. “Narratiivisen tutkimuksen eettiset haasteet.” [The Ethical Challenges of Narrative Research]. In Multidisciplinary Ethics. Discussion and Questions, edited by A.-M. Pietilä and H. Länsimies-Antikainen, 121–137. Kuopio University Publications F. University Affairs 45.Kuopio.

- Heikkinen, H. L. T., J. Utrianen, I. Markkanen, M. Pennanen, M. Taajamo, and P. Tynjälä. 2020. “Attractiveness of Teacher Education. Final Report.” Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. Publications 2020:26. Helsinki. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/162423/OKM_2020_26.pdf.

- Holstein, J. A., and J. F. Gubrium. 2012. “Introduction: Establishing a Balance.” In Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by J. A. Holstein and J. F. Gubrium, 1–12. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Jardí, R. W., C. Petreñas, and I. Puigdellívol. 2022. “Building Successful Partnerships Between Teaching Assistants and Teachers: Which Interpersonal Factors Matter?” Teaching and Teacher Education 109: 103523. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2021.103523.

- Jardí, A., I. Puigdellívol, and C. Petreñas. 2021. “Teacher Assistants’ Roles in Catalan Classrooms: Promoting Fair and Inclusion-Oriented Support for All.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 (3): 313–328. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1545876.

- Köpfer, A., and U. Böing. 2020. “Students’ Perspectives on Paraprofessional Support in German Inclusive Schools: Results from an Exploratory Interview Study with Students in Northrhine Westfalia.” International Journal of Whole Schooling 16 (2): 70–92.

- Kovač, V. B., and B. L. Vaala. 2021. “Educational Inclusion and Belonging: A Conceptual Analysis and Implications for Practice.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 (10): 1205–1219. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1603330.

- Kuurne (née Ketokivi), K., and A. Vieno. 2021. “Developing the Concept of Belonging Work for Social Research.” Sociology. doi:10.1177/00380385211037867.

- Lähdesmäki, T., T. Saresma, K. Hiltunen, S. Jäntti, N. Sääskilahti, A. Vallius, and K. Ahvenjärvi. 2016. “Fluidity and Flexibility of ‘Belonging’: Uses of the Concept in Contemporary Research.” Acta Sociologica 59 (3): 233–247. doi:10.1177/0001699316633099.

- Lakkala, S., A. Galkienė, J. Navaitienė, T. Cierpiałowska, S. Tomecek, and S. Uusiautti. 2021. “Teachers Supporting Students in Collaborative Ways—An Analysis of Collaborative Work Creating Supportive Learning Environments for Every Student in a School: Cases from Austria, Finland, Lithuania, and Poland.” Sustainability 13: 2804. doi:10.3390/su13052804.

- Lederer, J., C. Breyer, and B. Gasteiger-Klicpera. 2021. “Concept of Knowledge Boxes – A Tool for Professional Development for Learning and Support Assistants.” Improving Schools 24 (2): 137–151. doi:10.1177/1365480220950568.

- Lieblich, A., R. Tuval-Mashiach, and T. Zilber. 1998. “Categorical-Content Perspective.” In Narrative Research, edited by A. Lieblich, R. Tuval-Mashiach, and T. Zilber, 112–138. Sage.

- May, V. 2011. “Self, Belonging and Social Change.” Sociology 45 (3): 363–378. doi:10.1177/0038038511399624.

- Moen, T. 2006. “Reflections on the Narrative Research Approach.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5: 56–69. doi:10.1177/160940690600500405.

- Nikula, E., P. Pihlaja, and P. Tapio. 2021. “Visions of an Inclusive School – Preferred Futures by Special Education Teacher Students.” International Journal of Inclusive Education. doi:10.1080/13603116.2021.1956603.

- O’Connor, U., F. Hasson, C. McKeever, and J. Finlay. 2021. “It is Changed Beyond all Recognition: Exploring the Evolving Habitus of Assistants in Special Schools.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 21 (2): 146–155. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12506.

- Paju, B. 2021. “An Expanded Conceptual and Pedagogical Model of Inclusive Collaborative Teaching Activities.” PhD diss., University of Helsinki.

- Paju, B., L. Räty, R. Pirttimaa, and E. Kontu. 2016. “The School Staff’s Perception to Their Ability to Teach Pupils with Special Educational Needs in Inclusive Settings in Finland.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 20 (8): 801–815. doi:10.1080/13603116.2015.1074731.

- Piškur, B., M. Takala, A. Berge, L. Eek-Karlsson, S. M. Ólafsdóttir, and S. Meuser. 2021. “Belonging and Participation as Portrayed in the Curriculum Guidelines of Five European Countries.” Journal of Curriculum Studies. doi:10.1080/00220272.2021.1986746.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. 1988. Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences. Albany: Sunny Pree.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. 1995. “Narrative Configuration in Qualitative Analysis.” In Life History and Narrative, edited by J. A. Hatch and R. Wisniewski, 5–23. London: Falmer Press.

- Riitaoja, A.-L. 2013. Toiseuksien rakentuminen koulussa. Tutkimus opetussuunnitelmista ja kahden helsinkiläisen alakoulun arjesta. Helsinki: University of Helsinki, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, Department of Teacher Education, Research Report 346.

- Rose, J. 2011. “Dilemmas of Inter-Professional Collaboration: Can They be Solved?” Children & Society 25: 151–163. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00268.x.

- Saloviita, T. 2020. “Teacher Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Students with Support Needs.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 20 (1): 64–73. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12466.

- Sharma, U., and S. J. Salend. 2016. “Teaching Assistants in Inclusive Classrooms: A Systematic Analysis of the International Research.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 41 (3): 118–134. doi:10.14221/ajte.2016v41n8.7.

- Slee, R. 2001. “‘Inclusion in Practice’: Does Practice Make Perfect?” Educational Review 53 (2): 113–123. doi:10.1080/00131910120055543.

- Takala, M. 2005. Koulunkäyntiavustajan työn sisältö ja haasteet [The Classroom Assistant Work Content and Challenges]. The University of Helsinki, The City of Helsinki, The Board of Education. https://docplayer.fi/7590002-Koulunjayntiavustajan-tyon-sisalto-ja-haasteet-marjatta-takala-2005.html.

- Takala, M. 2007. “The Work of Classroom Assistant in Special and Mainstream Education in Finland.” British Journal of Special Education 34 (1): 50–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.2007.00453.x

- Takala, M. 2016. “Koulunkäynninohjaajat – mahdollistajia [School Assistants – Enablers].” In Erityispedagogiikka ja kouluikä [Special Education and School Age], edited by M. Takala, 126–136. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

- United Nations. 2016. Identifying Social Inclusion and Exclusion. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/rwss/2016/chapter1.pdf.

- van Manen, M. 1990. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. London: Althouse Press.

- Vetoniemi, J., and E. Kärnä. 2019. “Being Included – Experiences of Social Participation of Pupils with Special Education Needs in Mainstream Schools.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 (10): 1190–1204. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1603329.

- Webster, R., and P. Blatchford. 2014. “Who has Responsibility for Teaching Pupils with SEN in Mainstream Primary Schools? Implications for Policy Arising from The ‘Making a Statement’ Study. Research in Special Needs and Inclusive Education: The Interface with Policy and Practice.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 14: 196–199. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12070.

- Wiggs, N. B., L. A. Reddy, B. Bronstein, T. A. Glover, C. M. Dudek, and A. Alperin. 2021. “A Mixed-Method Study of Paraprofessional Roles, Professional Development, and Needs for Training in Elementary Schools.” Psychology in the Schools 58: 2238–2254. doi:10.1002/pits.22589.

- Yates, P. A., R. V. Chopra, E. E. Sobeck, S. N. Douglas, S. Morano, V. L. Walker, and R. Schulze. 2020. “Working With Paraeducators: Tools and Strategies for Planning, Performance Feedback and Evaluation.” Intervention in School and Clinic 56 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1177/1053451220910740.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2006. “Theorising Identity: Beyond the ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ Dichotomy.” Patterns of Prejudice 44 (3): 261–280. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2010.489736.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2010. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice 40 (3): 197–214. doi:10.1080/00313220600769331.

- Zhao, Y., R. Rose, and M. Shevlin. 2021. “Paraprofessional Support in Irish Schools: From Special Needs Assistants to Inclusion Support Assistants.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 36 (2): 183–197. doi:10.1080/08856257.2021.1901371.