ABSTRACT

Effective collaborative engagement between diverse stakeholders is vital to supporting the developmental and educational opportunities and outcomes of students with disability. While Australian policy and legislation mandates collaborative engagement between a teacher and other members of a student’s support network, the extent of data examining stakeholder experiences of fulfilling these obligations remained unknown. To close this gap, the current study employed a scoping review methodology to investigate how collaborative engagement between teachers and families and/or allied health therapists had been reported in the literature since the introduction of the Disability Standards for Education 2005 (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2006). A total of seven empirical articles were suitable for inclusion within the review. The findings address the existing span of literature into collaborative engagement between teachers and other stakeholders for students with disability, as well as the facilitators, barriers, and opportunities acknowledged. This article adds to the growing body of literature around the concept of collaborative engagement between stakeholders supporting students with disability. It further provides recommendations for researchers and policymakers to continue advancing knowledge and support of this critical practice.

Introduction

The goals of Australian education acknowledge the rights of all students to access and participate in quality learning programs, as well as the expectations of education providers to ensure that the impacts of student disadvantage are reduced (Education Council Citation2019). Further, Australia’s social justice and human rights model of education emphasises inclusion, and inclusive practices, for all (Department of Education and Training Citation2015). These are crucial considerations in the education of students with disability in Australian educational programs.

There is lack of specificity around the proportion of students with disability in Australia based on the way different government agencies measure and classify individuals with disability. For example, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) data only captures students with diagnosed disability (Citation2020); whereas, within the Nationally Consistent Collection on School Students with Disability (NCCD) students with both diagnosed and imputed disability are included in the statistics. Data from the AIHW (Citation2020) reveal that approximately 10% of students enrolled in Australian primary and secondary schools have a disability; however, data collated through the NCCD in 2020 demonstrate that 19.9% of students received an adjustment due to disability (Department of Education Skills and Employment Citation2021). While rates of primary and secondary school attendance for students with disability are comparable to the rate of attendance of students without disability (both recorded at 89%), post-secondary education enrolment is meaningfully lower for individuals with disability (n = 9.1%) compared with their peers without disability (n = 14.85%) (AIHW Citation2020). Understanding the educational circumstances of students with disability during compulsory education (i.e. primary and secondary school) is vital to recognising areas of strengths and others requiring improvement to ensure students are provided developmentally appropriate opportunities to promote their progress, independence, and agency; both within their education and into the workforce.

While collaborative partnerships are vital to the education of every student enrolled in school programs (Emerson et al., Citation2012), students with additional educational, social, emotional, or physical needs may benefit from the inclusion of external support workers involved in their development (Prior et al. Citation2011). A recent exploration of the collaborative experiences of teachers, parents, and allied health professionals (AHP) involved in the education of students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in Australian mainstream schools indicated that collaborative teamwork between the central stakeholders involved in a child’s development is not yet a consistent feature within the Australian education system (Vlcek, Somerton, and Rayner Citation2020).

The inherent right to equitable opportunities for individuals with disability in Australia is established in Commonwealth Law through the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA) (Australian Government Citation1992). The DDA makes it unlawful to discriminate against a person due to his or her disability, or the specific nature of disability (Australian Government Citation1992). It is unlawful for an educational institution to refuse admission, limit access, or exclude participation in curricular areas based solely on an individual’s disability (Australian Government Citation1992). Despite this, particular caveats allow admission of students with disability to be refused if their diagnosis does not align with an establishment designed intentionally for a population with a specific disability, or if an individual’s admission, or required adjustments, would cause ‘unjustifiable hardship’ to the educational provider (Australian Government Citation1992, 22).

Within the Disability Standards for Education 2005 (DSE) (Commonwealth of Australia [COA] Citation2006), every student with disability is entitled to an education ‘on the same basis as other students without disability’ (11), and to have their needs addressed in an equitable way. Educational providers are expected to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to ensure students with disability are able to achieve learning outcomes, participate in learning experiences, and have opportunities for independence (14). Further, educational providers are required to consult with the student with disability, or an advocate of the student, regarding potential adjustments to determine the appropriateness of an adjustment prior to implementation (COA Citation2006).

In recent years, there has been a substantial increase in literature that supports the benefits of home-school partnerships (see, for example, Bull et al., Citation2008; Ellis, Lock, and Lummis Citation2015; Epstein Citation2010; Farrington et al., Citation2012; Francis et al. Citation2016; Hall and Ed Citation2014; Henderson and Mapp Citation1998; Sormunen, Tossavainen, and Turunen Citation2011). At the school level, teachers at all qualification stages must demonstrate capacity to differentiate teaching to cater to the needs of all students (Standard 1.5), and to ensure the full participation of students with disability (Standard 1.6) (Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL] Citation2015). Teachers must also demonstrate their capacity to effectively engage families in their child’s education (Standard 3.7), and engage with families in a sensitive and confidential manner (Standard 7.3) (AITSL Citation2015).

The overarching policies within these guiding policies and Standards, reflect the view that students with disability should be treated in an equitable way alongside peers without disability. Further, families maintain a right to be actively involved in their child’s education (AITSL Citation2015; COA Citation2006). Despite this, understanding of how these mandates directly influence the support provided to Australian students at the school or classroom level has not been extensively addressed. It is, therefore, critical that stakeholder experiences of collaboration within the education of students with disability are examined. Paragraph: use this for the first paragraph in a section, or to continue after an extract.

Method

A scoping review methodology was employed to meet the exploratory objectives which were; to identify research published post implementation of the DSE involving parents and other stakeholders in the education of a child with disability. According to Khalil et al. (Citation2021), scoping reviews are appropriate to identify key concepts relating to a particular topic addressed in the literature. For the present study, the expectation of consultation mandated within the DSE (COA Citation2006) provided a relevant basis to explore how interactions between stakeholders involved in the education of students with disability following its introduction had been addressed in Australian research. It was anticipated that the review would provide policymakers and researchers with a deepened understanding of the purpose and practice of collaboration between current and emerging stakeholders involved in the education of students with disability at the school and classroom level.

Search strategy

A three-step review protocol was developed and employed to locate, evaluate, and report on literature involving stakeholder experiences of collaborative engagement for students with disability in Australia. Firstly, a systematic search was conducted to locate available literature within common education databases. Each article was published in English between 2006 and 2020, was peer-reviewed, with the full text available online. The search consisted of the following terms: (collab* OR communic* OR cooperat* OR consult* OR engag*) AND (education OR school) AND (disability) AND (Australi*). Terms with an asterisk allowed the database to search for inflected terms (for example, collab* would allow for the identification of collaboration/s, collaborative, collaborating, collaborate/s, or collaborated). Due of the scope of the study, articles that did not mention the locality of the participants, or where the locality was outside of Australia, were not included further.

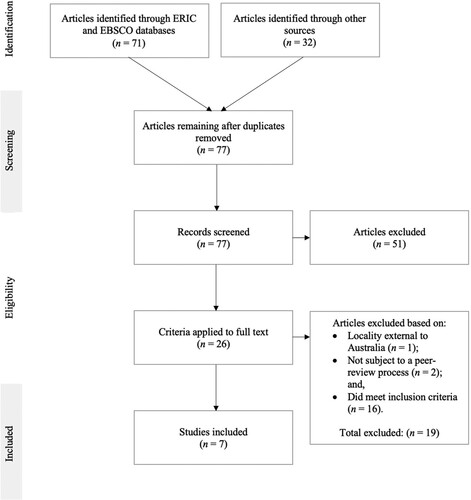

Subsequently, two members of the research team independently screened the abstracts of the studies located in the search. Articles that did not meet the search criteria were excluded. The same researchers then independently analysed each remaining article using the three-point coding system following Finkelstein et al.’s (Citation2021) classification system: a score of ‘1: irrelevant’ was allocated to an article that had a tentative alignment with the review’s focus, but did not meet one or more criterion. This related to articles where the authors might have addressed some of the criteria, such as parents and education, but not discussed anything related to this study specifically, such as the parent’s collaborative interactions with any other people involved in their child’s education. A score of ‘2: uncertain’ was allocated to an article that met the formal criteria for inclusion, but collaboration (or related interaction) was not the primary subject of the study and/or findings; and, a score of ‘3: relevant’ was allocated to an article that was highly relevant and suitable for inclusion in the formal review. The researchers compared results and discussed any discrepancies until consensus was reached. Articles that achieved a final rating of ‘3: relevant’ were included in the formal analysis. Finally, the reference list of each article included in the review was examined to identify other potential studies for inclusion. The researchers independently analysed these using the same coding and cross-referencing method described above to achieve a final decision on each article’s suitability for inclusion. displays a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart illustrating the article selection and inclusion process for this scoping review (Moher et al. Citation2009).

Data analysis

The analysis consisted of two stages. Initially, the broad topics addressed within the studies were identified and summarised. From this process, three topics related to collaboration were extracted: fulfilling professional responsibilities, times of transition, and identifying and supporting student needs. The articles were then analysed following an emergent thematic process (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Within this process, each article was re-read and leading words were manually highlighted. The words located were then collated and reviewed to ascertain dominant and recurring words that were then labelled as codes and grouped under categories. Each article was then reread to identify patterns across the dataset. This led to preliminary codes that were then evaluated to reveal overarching themes. Each of these themes were then sorted into broader categories (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). In total, seven themes emerged across three categories (displayed in ).

Table 1. Review categories and themes.

The results of the analysis are displayed according to the topics relevant to each article, and then the discussion unpacks the categories and themes that emerged from the results.

Results

A total of 26 articles met the criteria for a comprehensive evaluation. Of these articles, two articles were removed on the basis they were not peer reviewed, one article was removed due to a focus on participants located outside of Australia, and a further 16 articles were excluded due to a focus outside the scope of the present review. Seven articles were included in the review and are summarised in . References marked with an asterisk identify studies included in the present summary and analysis.

Table 2. Summary of study and participant characteristics included in the review.

The scoping review identified three topics that are summarised in the results, and the analysis identified three categories and seven themes that have been synthesised into the discussion.

Topic 1: times of transition

One of the most common topics regarding collaborative engagement was connected to times of transition. Four articles were specifically concentrated on transitions. One article focused solely on the transition between primary and secondary school (Tso and Strnadová Citation2017), another article focused solely on the transition between secondary and post-school life (Meadows, Davies, and Beamish Citation2014), and two articles focused on both transition circumstances (Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016; Strnadová and Cumming Citation2014).

Within three of the articles, collaborative engagement with parents throughout the transition process was identified as a critical element of the process. For example, within Tso and Strnadová’s (Citation2017) study, the authors found that parents appreciated home-school collaboration that was reciprocal, supported the transference of strategies from the school to home environment, and teachers willing to work collaboratively with AHPs. Conversely, the authors noted that parent participants were dissatisfied with home-school collaboration arrangements when they felt ignored by teachers, their ideas or concerns were dismissed, and when teachers were unwilling to learn more about the student at the centre of the support. The study also recognised the importance of home-school collaboration beyond a focus on schoolwork or situations of concern (Tso and Strnadová Citation2017).

Strnadová and Cumming (Citation2014) survey of primary and secondary school teachers addressed factors related to home-school collaboration benefits, opportunities, barriers, and perceptions of parents. The results found teachers typically identified individual education program meetings, general meetings, and direct phone and email contact as the common ways they collaborated with parents. The participants recognised that supporting the inclusion of parents in their child’s education could be improved, including through increasing involvement and training opportunities for parents. Interestingly, the results recognised that parental distrust, unrealistic expectations placed upon the school, personal circumstances, and staff overload were barriers to home-school collaboration during times of transition. Teacher participants also commented on a perception that parents expected teachers to ‘fix’ their children with disability (Strnadová and Cumming Citation2014, 329).

Strnadová et al.’s (Citation2016) findings did not explicitly mention the core features of beneficial collaborative engagement. Their study of parents and teachers found that open communication and support during times of transitions lead to beneficial outcomes for students with ASD and/or intellectual disability. The teacher participants further acknowledged that a ‘lack of time and poor communication’ were some of the difficulties with collaboration between primary school teachers and secondary school teachers during times of transition (Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016, 149). A key finding from the research acknowledged that involving students, and empowering parents to take an active role during transitional stages was necessary to best support students with disability during times of transition (Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016).

Unlike the previous three articles, Meadows et al.’s (Citation2014) research on transitions for students with disabilities focussed on interagency collaboration between high school transition teachers and post-school agencies. The findings determined that the teacher participants were hesitant to become involved with sources external to their schools. The results indicated that the participants were more likely to implement interagency collaboration when they could facilitate the process, rather than having the process facilitated at a regional or system level. The findings acknowledged the participants’ perception that they considered the system more broadly as unresponsive to their needs, creating a barrier to transition service delivery. Despite this, the participants explained that improving systemic and policy issues alongside professional development for regional or system level administrators would likely improve their ability to support students’ post-school transitions (Meadows, Davies, and Beamish Citation2014).

Topic 2: identifying and supporting student needs

Two articles reviewed cited collaboration as a process to increase teacher capacity to identify and support student needs. Vincent et al.’s (Citation2008) examination of school teachers’ perceptions of reports prepared by occupational therapists (OT) identified difficulties with current processes. While the participants reported that OT reports were predominantly intelligible, they also noted a disconnect between what was being addressed or suggested within the reports and what would be practical at the school or classroom level. Further, the participants identified concerns with a lack of direct communication and collaboration to discuss the report in the context of the student’s needs within their particular classroom. Overall, the participants recognised that the majority of strategies suggested might support the educational outcomes of students with disabilities; however, they wanted more direct opportunities to communicate and collaborate with specialists to develop targeted and realistic plans, as well as additional training to implement appropriate strategies (Vincent, Stewart, and Harrison Citation2008).

Ludicke and Kortman (Citation2012) examination of the perceptions of parent and teacher roles and responsibilities in learning partnerships, as well as how effective collaboration is conceptualised, identified similarities and differences amongst the parent ‘sets’ (160) and teacher participant cohorts. Both participant groups acknowledged that parental involvement played an important role in the educational outcomes for students with diverse needs. The participants in the parent set identified interactive activities, such as their support of home learning activities and attendance at meetings or during formal parent-teacher events, as their primary roles and responsibilities regarding involvement. Teacher participants, however, focussed more on participatory activities, such as following up on school-based events, providing important historical information about the student to the school, as well as participation in school events, when identifying involvement characteristics of parents in the learning process.

Ludicke and Kortman (Citation2012) reported that the teacher participants recognised school and system procedures, environmental arrangements, and resourcing as barriers to effective collaboration and participation. Suggestions from parent participants identified improvements to reciprocal communication and enacting suggested strategies at the classroom level as necessary advances to overcome current barriers; whereas, teacher participants highlighted the need for processes that expediated effective communication opportunities (Ludicke and Kortman Citation2012).

Topic 3: fulfilling professional responsibilities

Within the studies reviewed, only one article reported on final year pre-service teachers’ confidence in meeting their professional responsibilities. The findings of Hudson et al.’s (Citation2016) study indicated 69% of the 312 pre-service teacher participants reported feeling confident in their ability to engage parents and carers to support student learning: Standard 3.6 of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (APST) at the Graduate career stage (AITSL Citation2015). This result aligned with the participants’ confidence in their knowledge of using strategies to support the full inclusion of students with disability (Standard 1.6), reported at 62%, as well as their confidence in reporting on student learning to parents and carers, 64%. Despite these results, over 50% of the participants reported that their professional experience mentor teachers were not supportive of them interacting with parents and carers (Hudson et al. Citation2016).

Hudson et al. (Citation2016) suggested that limited opportunities to authentically practice engaging with parents and carers during pre-service teacher courses and professional placements likely contributed to the participants’ self-reported confidence levels. Further, the authors recognised that the same limitations regarding practical experience were believed to have influenced the participants’ confidence of using strategies to support learners with disabilities, and limited opportunities to authentically apply their knowledge was impacting overall confidence. Practical opportunities to explicitly engage with parents and carers during final professional experience placements, alongside explicit role-play opportunities within tertiary courses, were suggested to improve pre-service teachers’ confidence at meeting these standards towards the end of their education courses (Hudson et al. Citation2016).

Discussion

The main intention of this review was to synthesise research on collaborative engagement between current and emerging stakeholders involved in the education of students with disability since the release of the DSE. The following discussion addresses the categories and themes that emerged from the review (please see ), and concludes with an overview of the limitations of the present study.

Benefits of effective collaborative engagement

This Australian review identified that cross-environmental strategies and support, whereby approaches are implemented consistently across settings relevant to a student’s development (e.g. home and school environments), as one of the primary benefits of collaboration addressed within recent literature (Ludicke and Kortman Citation2012; Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016; Strnadová and Cumming Citation2014; Tso and Strnadová Citation2017). These results are consistent with national and international literature into effective home-school partnerships as a method for supporting student needs across their primary environments (see, for example, Epstein and Salinas Citation2012; Goldman et al. Citation2019; Rafferty, Grolnick, and Flamm Citation2012). While research has examined explicit interventions across home and school environments, such as conjoint behavioural consultation (CBC) (Clarke, Sheridan, and Woods Citation2014; Sheridan et al. Citation2011; Sheridan and Wheeler Citation2017), less targeted benefits have also been identified. Vlcek et al.’s (Citation2020) survey of teachers, parents, and AHPs involved in the education of students with ASD in Australia also identified combined supports for shared goals and collaborator development as benefits of collaborative teamwork (Vlcek, Somerton, and Rayner Citation2020).

Similar to the findings of this review, the benefits of environmental strategies and supports are consistently acknowledged across the literature, and specifically emphasise the impact on student outcomes. Research into the experiences and needs of students with disability, transitioning through different educational stages is well-established (see, for example, Fontil and Petrakos Citation2015; Leonard et al. Citation2016; Mandy et al. Citation2016; Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta Citation2000). The results of this review align with the findings of other research concerning the difficulties associated with transitions for students with disability, and recognise how collaborative engagement between the central stakeholders in a student’s education provides increased opportunities to support students through these uncertain times (Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016; Strnadová and Cumming Citation2014; Tso and Strnadová Citation2017). Ludicke and Kortman’s (Citation2012) findings emphasising the role of collaboration for supporting students’ educational outcomes, are also consistent with literature examining the benefits of home-school collaboration for both students with and without disability (see, for example, Epstein, Citation2011; Moll et al. Citation1992; Olvera and Olvera Citation2012; Rafferty, Grolnick, and Flamm Citation2012; Sormunen, Tossavainen, and Turunen Citation2011). The benefits of effective collaborative engagement established within this review demonstrates the importance of the practice in supporting the holistic development of students with disability.

Barriers to effective collaborative engagement

The current review identified participants’ concerns with current communication and collaboration methods (Ludicke and Kortman Citation2012; Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016; Strnadová and Cumming Citation2014; Tso and Strnadová Citation2017; Vincent, Stewart, and Harrison Citation2008). Parent participants in particular identified difficulties with establishing reciprocal communication processes (Ludicke and Kortman Citation2012; Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016). This finding is consistent with previous research which found differing motivations for collaboration across stakeholders negatively impact collaborator relationships, and, in turn, reduces provisions of support (Vlcek, Somerton, and Rayner Citation2020). In order to remedy these barriers to effective collaboration, developing reciprocal communication processes, whereby information is shared from and with stakeholders, is vital to meeting the diverse needs of students (Reupert, Depeler, and Sharma Citation2015). Variability in communication and collaboration structures across and within schools, as well as intended outcomes of these interactions at the school level, is an important consideration in order to achieve reciprocal communication. A greater emphasis on consolidating processes and focussing on supporting each collaborator to understand one another’s motivations, aspirations, capabilities, and opportunities is likely to improve collaborative engagement at the student level.

Time, funding, and resourcing constraints were also acknowledged as a barrier to effective collaborative engagement between key stakeholders (Hudson et al. Citation2016; Meadows, Davies, and Beamish Citation2014; Strnadová and Cumming Citation2014; Vincent, Stewart, and Harrison Citation2008). Limited time, funding, and resources to support collaboration with parents and other stakeholders involved in the education of students with disability have been identified as primary constraints by teachers in previous research (Lindsay et al. Citation2013; Vlcek, Somerton, and Rayner Citation2020). Beyond collaboration specifically, limited time, funds, and resources have been identified as a barrier to numerous inclusive and special education pursuits (Meijer and Watkins Citation2019). Concern for how resources are used to directly influence inclusive education priorities, such as for students with disability, has been also been identified in international literature (Sharma and Vlcek Citation2021). While changes to funding and resourcing arrangements are likely needed at a systemic level, it is imperative schools identify opportunities for allocating appropriate time, funds, and resources for teachers to adequately collaborate with key stakeholders involved in the education of their students with disability. Policy-makers and researchers are encouraged to examine necessary modifications at the system level to support schools in developing appropriate plans to minimise the impact of these constraints.

Opportunities to increase effective collaborative engagement

The need for increased professional development at all levels of the education system was noted by a range of participants across three studies (Hudson et al. Citation2016; Meadows, Davies, and Beamish Citation2014; Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016). This included, professional development for pre-service teachers, school teachers and employees, parents, as well as system level administrators. These results are consistent with Chrysostomou and Symeonidou’s (Citation2017) research which suggested that both professional development for pre-service teachers, as well as continuing professional development for in-service teachers, is a necessary feature of inclusive practices and support for the diverse needs of all students. They explain that professional development can be informal, and that collaboration between educators from different contexts allows each participant to share perspectives and ways of thinking and meeting the needs of students (Chrysostomou and Symeonidou Citation2017). Professional development emphasising clear collaborative processes has also been found to increase teachers’ understanding of the needs of students with disability, and strategies to support these at the classroom level (Ní Bhroin and King Citation2020). In this manner, effective collaborative engagement can both be a product of development through active professional immersion in the process and targeted professional development.

A finding embedded in this data pool acknowledged the wider system in which schools operate, and the direct and indirect impact of administration at a system level on collaborative engagement, teacher opportunities, and student support (Ludicke and Kortman Citation2012; Meadows, Davies, and Beamish Citation2014; Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016; Strnadová and Cumming Citation2014; Vincent, Stewart, and Harrison Citation2008). Within the Australian context, the two dominant schooling systems (government and Catholic) (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2020) within each state are directed by jurisdictional agencies that support the allocation of funding, programming, and compliance procedures. The findings of this review indicate that there is currently limited research into the role of school system agencies and administrators, and their direct or indirect impact on collaborative engagement between stakeholders of students with disability. Further research in this area is needed to ascertain the specific roles, responsibilities, and experiences of individuals working at this level to identify appropriate measures to increase opportunities for collaborative engagement at the school, classroom, and individual student levels.

Data provided within the studies reviewed also suggested concerns with inclusive practices more broadly (Strnadová, Cumming, and Danker Citation2016). Strnadová et al.’s (Citation2016) research identified that a proportion of teachers perceived student disability as a permissible reason to exclude students from activities provided to other students; in direct contradiction to Australian policy and legislation (see, for example, Australian Government Citation1992; COA Citation2006). Furthermore, while a high proportion (98%) of the pre-service teacher participants in Hudson et al.’s (Citation2016) study felt confident regarding their understanding of how students learn (Standard 1.2), only 62% of participants felt confident in their knowledge of using strategies to support the full inclusion of students with disability (Standard 1.6) (AITSL Citation2015). Similarly, the results identified only 72% of the participants felt confident in their ability to successfully teach students with diverse cultural backgrounds (Standard 1.3), and 60% felt they could engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students (Standard 1.4).

These results suggest a possible fracture in the relationship between general pedagogical knowledge and more specific knowledge of inclusive education legislation, policies, philosophy, and practice. Concerns regarding teachers’ and pre-service teachers’ understanding of inclusive practices, and the role of supporting students with disability, are well established in Australian and international literature (see, for example, Forlin et al. Citation2009; Forlina and Chambersb Citation2011; Obiakor et al., Citation2012; Round, Subban, and Sharma Citation2016; Savolainen et al. Citation2012; Schwab and Alnahdi Citation2020; Sharma, Loreman, and Forlin Citation2012; Vaz et al. Citation2015). Despite this, there remains an insufficient understanding for how this conceptual gap relates to teacher and pre-service teacher understanding of and experiences with collaboration between stakeholders in the education of students with disability. Further research in this area should examine the explicit relationship between inclusive practices, and support a broader process of monitoring and evaluation of adherence to legislative mandates (for example, the DDA and DSE), and collaborative engagement regarding the key individuals supporting students with disability.

Limitations

The small quantity of empirical studies that discussed collaborative engagement between key personnel in the education of students with disability has implications for the findings of this review. While various studies examine the benefits of collaboration for students with disability, there remains an insufficient base of literature to ascertain how collaboration is directly influencing the education of Australian students with disability. Further, inclusive education in Australia is recognised as a continuum of support for all students, not just students with disability. This has implications for the terms used in the literature search given that the term ‘disability’ might not be included within all articles relating to the education of Australian students with disability (Finkelstein, Sharma, and Furlonger Citation2021). Despite these limitations, we suggest this presents an opportunity for policy-makers and researchers to address this area further to ensure that the ideals of Australian policy and legislation (namely, the DDA, DSE, and APST) are implemented authentically in teaching practice. At an administrative level, clear parameters around collaborative engagement should be ascertained, and school processes regarding opportunities for collaborative engagement between teachers and other relevant stakeholders should be further evaluated. Additionally, formal and informal professional development opportunities should be explored to ensure all pre-service and in-service teachers have the necessary understanding and capacity to meet their professional obligations for engaging parents and carers in the learning process, and catering to the specific needs of students with disability.

Conclusion

This review has synthesised the available literature concerning collaborative engagement between current and emerging stakeholders involved in the education of Australian students with disability. The findings indicate that there are varied benefits of collaborative engagement between the core personnel involved in the development of children with disability. Directions for future research have also been suggested to ensure that collaborative engagement is a prominent feature in the education of students with disability and that current barriers are appropriately identified and removed. Policymakers and researchers are encouraged to examine collaborative practices further to promote the full inclusion of students with disability.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Samantha Vlcek

Samantha Vlcek is an associate lecturer in the School of Education at RMIT University, Australia. Sam has taught in both primary schools and at a tertiary level. Her research and teaching are concerned with inclusive education, collaboration, and supporting the students with diverse needs. Samantha has comprehensive knowledge of disability legislation and policy, as well as a deep understanding of implementing evidence-based practices to support student experience and outcomes.

Michelle Somerton

Dr Michelle Somerton is an Assistant Professor at the Graduate School of Education and Chair of the Special Learning Needs Committee. She holds a PhD, Graduate Certificate in Research, and a Bachelor of Education with Honours from the University of Tasmania. Her teaching concerns Inclusive Education in leadership, policy, pedagogy, and creating inclusive schools. He research interests are investigating educational inequity and barriers to education, educational technologies, and students with autism.

References

- Allied Health Professions Australia. n.d. Helping Children with Autism: Evidence-Based Assessment and Treatment – A Guide for Health Professionals. https://www.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/Autism-health-professional-booklet.pdf.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2020. Schools. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/schools/latest-release#data-download.

- Australian Government. 1992. The Disability Discrimination Act. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2016C00763.

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. 2015. Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. http://www.aitsl.edu.au/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers/standards/list.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2020. People with Disability in Australia 2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/ee5ee3c2-152d-4b5f-9901-71d483b47f03/aihw-dis-72.pdf.aspx?inline=true.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bull, A., K. Brooking, and R. Campbell. 2008. Successful Home-School Partnerships: Report to the Ministry of Education. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

- Chrysostomou, M., and S. Symeonidou. 2017. “Education for Disability Equality Through Disabled People’s Life Stories and Narratives: Working and Learning Together in a School-Based Professional Development Programme for Inclusion.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 32 (4): 572–585. doi:10.1080/08856257.2017.1297574.

- Clarke, B. L., S. M. Sheridan, and K. E. Woods. 2014. “Conjoint Behavioral Consultation: Implementing a Tiered Home-School Partnership Model to Promote School Readiness.” Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 42 (4): 300–314. doi:10.1080/10852352.2014.943636.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2006. Disability Standards for Education 2005: Plus guidance notes. https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/disability_standards_for_education_2005_plus_guidance_notes.pdf.

- Department of Education and Training. 2015. Planning for personalised learning and aupport: A national resource based on the disability standards for education 2005. https://www.dese.gov.au/swd/resources/planning-personalised-learning-and-support-national-resource-0.

- Department of Education Skills and Employment. 2021. Final report: 2020 review of the disability standards for education 2005. https://www.dese.gov.au/disability-standards-education-2005/resources/final-report-2020-review-disability-standards-education-2005.

- Education Council. 2019. Alice Springs (Mparntwe) education declaration.

- Ellis, M., G. Lock, and G. Lummis. 2015. “Parent-teacher Interactions: Engaging with Parents and Carers.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 40 (5): 160–174. doi:10.14221/ajte.2015v40n5.9.

- Emerson, L., J. Fear, S. Fox, and E. Sanders. 2012. Parental Engagement in Learning and Schooling: Lessons from Research. A Report by the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) for the Family-School and Community Partnerships Bureau. Canberra.

- Epstein, J. L. 2010. “School/Family/Community Partnerships: Caring for the Children We Share.” Phi Delta Kappan 92), doi:10.1177/003172171009200326.

- Epstein, J. L. 2011. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Im-Proving Schools. 2nd ed. Westview Press.

- Epstein, J. L., and K. C. Salinas. 2012. “Partnering with Families.” AJN, American Journal of Nursing 112: 11–19. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000421001.16760.b8.

- Farrington, C. A., M. Roderick, E. Allensworth, J. Nagaoka, T. S. Keyes, D. W. Johnson, and N. O. Beechum. 2012. Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners- The Role of Noncognitive Factors in Shaping School Performance: A Critical Literature Review. Chicago Consortium for School Research, University of Chicago.

- Finkelstein, S., U. Sharma, and B. Furlonger. 2021. “The Inclusive Practices of Classroom Teachers: A Scoping Review and Thematic Analysis.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 (6): 735–762. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1572232.

- Fontil, L., and H. H. Petrakos. 2015. “Transition to School: The Experiences of Canadian and Immigrant Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Psychology in the Schools 52 (8): 773–788. doi:10.1002/pits.21859.

- Forlin, C., T. Loreman, U. Sharma, and C. Earle. 2009. “Demographic Differences in Changing pre-Service Teachers’ Attitudes, Sentiments and Concerns About Inclusive Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 13 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1080/13603110701365356.

- Forlina, C., and D. Chambersb. 2011. “Teacher Preparation for Inclusive Education: Increasing Knowledge but Raising Concerns.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 39 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2010.540850.

- Francis, G. L., M. Blue-Banning, S. J. Haines, A. P. Turnbull, and J. M. S. Gross. 2016. “Building “our School”: Parental Perspectives for Building Trusting Family–Professional Partnerships.” Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth 60 (4): 329–336. doi:10.1080/1045988X.2016.1164115.

- Goldman, S. E., K. A. Sanderson, B. P. Lloyd, and E. E. Barton. 2019. “Effects of School-Home Communication with Parent-Implemented Reinforcement on off-Task Behavior for Students with ASD.” Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 57 (2): 95–111. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-57.2.95.

- Hall, B. R. A., and D. Ed. 2014. “A Case Study: Feeling Safe and Comfortable at School.” Journal for Leadership and Instruction 15 (2): 28–31.

- Henderson, A. T., and K. L. Mapp. 1998. A New Wave of Evidence the Impact of School, Family and Community Conections on Student Achievement. doi:10.1016/S0143-974X(98)80047-3.

- Hudson, S. M., P. Hudson, N. L. Weatherby-Fell, and B. Shipway. 2016. “Graduate Standards for Teachers: Final-Year Preservice Teachers Potentially Identify the Gaps.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 41 (9): 135–151. doi:10.14221/ajte.2016v41n9.8.

- Khalil, H., Peters, M. D., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Munn, Z. 2021. Conducting high quality scoping reviews-challenges and solutions. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 130, 156–160. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.009.

- Leonard, H., K. R. Foley, T. Pikora, J. Bourke, K. Wong, L. McPherson, N. Lennox, and J. Downs. 2016. “Transition to Adulthood for Young People with Intellectual Disability: The Experiences of Their Families.” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 25 (12): 1369–1381. doi:10.1007/s00787-016-0853-2.

- Lindsay, S., M. Proulx, N. Thomson, and H. Scott. 2013. “Educators’ Challenges of Including Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Classrooms.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 60 (4): 347–362. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2013.846470.

- Ludicke, P., and W. Kortman. 2012. “Tensions in Home-School Partnerships: The Different Perspectives of Teachers and Parents of Students with Learning Barriers.” Australasian Journal of Special Education 36 (Issue 2): 155–171. doi:10.1017/jse.2012.13.

- Mandy, W., M. Murin, O. Baykaner, S. Staunton, J. Hellriegel, S. Anderson, and D. Skuse. 2016. “The Transition from Primary to Secondary School in Mainstream Education for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Autism 20 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1177/1362361314562616.

- Meadows, D., M. Davies, and W. Beamish. 2014. “Teacher Control Over Interagency Collaboration: A Roadblock for Effective Transitioning of Youth with Disabilities.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 61 (4): 332–345. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2014.955788.

- Meijer, C. J. W., and A. Watkins. 2019. “Financing Special Needs and Inclusive Education – From Salamanca to the Present.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (7–8): 705–721. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1623330.

- Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, A. Liberati, and D. G. Altman. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/151/4/264.

- Moll, L. C., C. Amanti, D. Neff, and N. Gonzalez. 1992. “Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms.” Theory Into Practice 31 (2): 132–141. doi:10.1080/00405849209543534.

- Ní Bhroin, Ó, and F. King. 2020. “Teacher Education for Inclusive Education: A Framework for Developing Collaboration for the Inclusion of Students with Support Plans.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (1): 38–63. doi:10.1080/02619768.2019.1691993.

- Obiakor, F. E., M. Harris, A. Rotatori, and B. Algozzine. 2012. For Example (Vol. 35, Issue 3). King.

- Olvera, P., and V. I. Olvera. 2012. “Optimizing Home-School Collaboration: Strategies for School Psychologists and Latino Parent Involvement for Positive Mental Health Outcomes.” Contemporary School Psychology 16: 77–87. http://proxy.lib.sfu.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ978375&site=ehost-live%5Cnhttp://www.caspwebcasts.org/new/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=51&Itemid=60.

- Prior, M., J. Roberts, S. Rodger, K. Williams, and R. Sutherland. 2011. “A Review of the Research to Identify the Most Effective Models of Practice in Early Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Rafferty, J. N., W. S. Grolnick, and E. S. Flamm. 2012. “Families as Facilitators of Student Engagement: Toward a Home-School Partnership Model.” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, edited by S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie, 343–364. Springer. http://link.springer.com/10.1007978-1-4614-2018-7.

- Reupert, A. E., J. M. Depeler, and U. Sharma. 2015. “Enablers for Inclusion: The Perspectives of Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Australasian Journal of Special Education 39 (1): 85–96. doi:10.1017/jse.2014.17.

- Rimm-Kaufman, S., and R. C. Pianta. 2000. “An Ecological Perspective on the Transition to Kindergarten.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 21 (5): 491–511. doi:10.1016/S0193-3973(00)00051-4.

- Round, P. N., P. K. Subban, and U. Sharma. 2016. “‘I Don't Have Time to be This Busy.’ Exploring the Concerns of Secondary School Teachers Towards Inclusive Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 20 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1080/13603116.2015.1079271.

- Savolainen, H., P. Engelbrecht, M. Nel, and O. P. Malinen. 2012. “Understanding Teachers’ Attitudes and Self-Efficacy in Inclusive Education: Implications for pre-Service and in-Service Teacher Education.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 27 (1): 51–68. doi:10.1080/08856257.2011.613603.

- Schwab, S., and H. G. Alnahdi. 2020. “Do They Practise What They Preach? Factors Associated with Teachers’ use of Inclusive Teaching Practices among in-Service Teachers.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 20 (4): 321–330. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12492.

- Sharma, U., T. Loreman, and C. Forlin. 2012. “Measuring Teacher Efficacy to Implement Inclusive Practices.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 12 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01200.x.

- Sharma, U., and S. Vlcek. 2021. “International Perspectives on Inclusive Education.” In Resourcing Inclusive Education, 51–65. doi:10.1108/S1479-363620210000015006.

- Sheridan, S. M., L. Knoche, K. Kupzyk, C. Edwards, and C. Marvin. 2011. “A Randomized Trial Examining the Effects of Parent Engagement on Early Language and Literacy: The Getting Ready Intervention.” Journal of School Psychology 49 (3): 361–383. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2011.03.001.

- Sheridan, S. M., and L. A. Wheeler. 2017. “Building Strong Family–School Partnerships: Transitioning from Basic Findings to Possible Practices.” In Family Relations (Vol. 66, Issue 4, 670–683. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. doi:10.1111/fare.12271

- Sormunen, M., K. Tossavainen, and H. Turunen. 2011. “Home-school Collaboration in the View of Fourth Grade Pupils, Parents, Teachers, and Principals in the Finnish Education System.” School Community Journal 21 (2): 185–211.

- Strnadová, I., and T. M. Cumming. 2014. “The Importance of Quality Transition Processes for Students with Disabilities Across Settings: Learning from the Current Situation in New South Wales.” Australian Journal of Education 58 (3): 318–336. doi:10.1177/0004944114543603.

- Strnadová, I., T. M. Cumming, and J. Danker. 2016. “Transitions for Students with Intellectual Disability and/or Autism Spectrum Disorder: Carer and Teacher Perspectives.” Australasian Journal of Special Education 40 (2): 141–156. doi:10.1017/jse.2016.2.

- Tso, M., and I. Strnadová. 2017. “Students with Autism Transitioning from Primary to Secondary Schools: Parents’ Perspectives and Experiences.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (4): 389–403. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1197324.

- Vaz, S., N. Wilson, M. Falkmer, A. Sim, M. Scott, R. Cordier, and T. Falkmer. 2015. “Factors Associated with Primary School Teachers’ Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities.” PLoS ONE 10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137002.

- Vincent, R., H. Stewart, and J. Harrison. 2008. “South Australian School Teachers’ Perceptions of Occupational Therapy Reports.” Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 55 (3): 163–171. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00703.x.

- Vlcek, S., M. Somerton, and C. Rayner. 2020. “Collaborative Teams: Teachers, Parents, and Allied Health Professionals Supporting Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Australian Schools.” Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education 44 (2): 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2020.11.