ABSTRACT

In this paper, the utility of instruments for evaluating how well preservice teachers are being prepared for teaching students with intellectual disability in inclusive classrooms are explored. This included an investigation using an instrument to assess the attitudes of first-year preservice teachers (PSTs) toward individuals with intellectual disability (n = 96) and to measure changes in PSTs’ attitudes after participating in a supplementary fieldwork experience that involved tutoring young adults with intellectual disability (n = 39). Results revealed that PSTs held generally positive attitudes, particularly those who had previous experience with people with intellectual disability. Involvement in the tutoring programme contributed further to promoting productive attitudes among PSTs by decreasing levels of discomfort when interacting with people with intellectual disability, but counterintuitively tempered their endorsement of inclusion in schools. While more opportunities for PSTs to work alongside students with intellectual disability in authentic contexts are needed to prepare them for the reality of being inclusive educators, our findings suggest that the current ways these opportunities are designed and assessed need further investigation.

A challenge facing initial teacher education programmes is to prepare preservice teachers (PSTs) for inclusive classrooms at a time when practicums in schools may not provide the types of successful experiences needed to advance exemplary inclusive practices (Aprile and Knight Citation2020). For example, many teachers are concerned about their own professional competency when it comes to teaching children with intellectual disability (ID) (Forlin, Keen, and Barrett Citation2008; Engelbrecht et al. Citation2003) and exhibit less positive attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ID than they do towards students with other disabilities (Avramidis and Norwich Citation2002; de Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert Citation2010). To meet this challenge, a number of teacher education institutions have designed and coordinated their own supplementary fieldwork experiences. This paper is focused on evaluating the impact of such fieldwork experiences in terms of preparing PSTs to teach students with disability in inclusive classrooms.

Evaluating the impact of teacher education programmes

In terms of assessing the impact teacher education programmes have on preparing PSTs for working with students with disability in inclusive classrooms, studies incorporating the use of repeated measures to assess change (i.e. utilising pre- and post-programme assessments) have dominantly used instruments to measure PSTs’ attitudes towards inclusion (including measures of confidence or concerns with orchestrating inclusive practices), and, to a lesser extent, PSTs’ attitudes towards interacting with (or level of comfort with) people with disabilities. In a systematic review, Lautenbach and Heyder (Citation2019) found 23 studies where changes in PSTs’ attitudes towards inclusion had been measured, including four studies where changes in PSTs’ attitudes towards interacting with a person with disability were also measured. Likewise, in a systematic review of Australian and US-based literature, Tristani and Bassett-Gunter (Citation2020) found 27 studies aimed at evaluating the impact of teacher education programmes involving specific interventions to prepare service teachers for teaching in inclusive classrooms: 20 of these studies employed repeated measures and 13 of these involved measuring PSTs’ attitudes towards inclusion and/or interacting with people with disabilities.

A broad appraisal of these two reviews covering the evaluation of initial teacher education programmes indicates that the evidence base is dated. Since 2013 (i.e. over the last ten years), only seven studies using repeated measures were identified in each review. Our own search uncovered additional studies but these too were dated. Searching the most recent literature we found two evaluation studies (Chakravarthi and White-McNulty Citation2020; Kisbu-Sakarya and Doenyas Citation2021) but neither had included the use of repeated measures.

A nuanced appraisal of studies where changes in PSTs’ attitudes have been measured reveals differences in findings depending on the nature of the initiatives being evaluated. Among studies that have evaluated changes in PSTs’ attitudes towards inclusion, coursework programmes have been found to increase PSTs’ endorsement of the principles and practices of inclusive education (e.g. Killoran, Woronko, and Zaretsky Citation2014; McWhirter et al. Citation2016; Shade and Stewart Citation2001), as has coursework coupled with fieldwork experiences. For example, Stella, Forlin, and Lan (Citation2007) found significant positive changes in PSTs’ attitudes towards inclusion after completing a coursework unit and fieldwork experience involving students from a special school visiting the campus and partaking in a day of ‘fun activities’ (165) that were organised and led by PSTs. Swain, Nordness, and Leader-Janssen (Citation2012) found that a unit on special education and a 20-hour fieldwork experience observing and working with students with disabilities in mainstream and special education settings produced positive changes in PSTs’ attitudes towards inclusion.

On the other hand, programmes incorporating coursework and field-based experiences have not always achieved the desired effect. For example, Forlin and Chambers (Citation2011) found no significant changes in attitudes towards inclusion after PSTs completed an inclusive education unit incorporating a voluntary social experience. Similarly, Woodcock (Citation2012) found no significant changes in PSTs’ levels of concern about inclusion after completing an inclusive education unit linked to a practicum. Van Laarhoven et al. (Citation2007) found PSTs were more likely to disagree with some items supporting inclusion after completing coursework and a field-based experience that involved them observing lessons and then teaching a lesson in an inclusive classroom. Avaraz McHatton and Parker (Citation2013) evaluated the impact of coursework coupled with a co-teaching placement in an inclusive school for one or two days, where a PST majoring in elementary teaching was paired with a PST majoring in special education. Using repeated measures before and after the initiative, they found improvements in attitudes towards inclusion among elementary majors but not among special-education majors (who had very positive attitudes to begin with). They assessed both groups again, towards the end of their degree, and noted a pattern of decreasing attitudes towards inclusion among special-education majors.

Among studies where changes in PSTs’ attitudes towards interacting with people with disability have been evaluated, findings have also differed. For example, Tait and Purdie (Citation2000) found statistically significant, but small, improvements in attitudes after PSTs completed a coursework unit on inclusion. Similarly, Carroll, Forlin, and Jobling (Citation2003) reported small but significant improvements in attitudes after PSTs completed coursework that was coupled with opportunities for each PST to socially interact with a student with disability at a school site (i.e. in a buddy system arrangement). Studies investigating the impact of more extensive practical experiences have produced mixed findings. Sharma, Forlin, and Loreman (Citation2008) compared the impact of four teacher education programmes and found the programme that produced the largest gain in preparing PSTs to interact positively with people with disability also provided the most extensive experience in a social environment (i.e. a buddy support, recreational programme encompassing 25 h). On the other hand, Lancaster and Bain (Citation2010) found the benefits of a field-based placement requiring PSTs to support or mentor a student with difficulties learning for 11 h in a regular class setting, did not exceed the benefits of a well-designed coursework unit in terms of positively influencing PSTs’ beliefs about their ability to interact with people with disabilities.

To advance evidence-based practices in initial teacher education, two broad implications can be drawn from these findings. First, given the positive change in attitudes found in response to coursework components and inconsistent findings in response to fieldwork experiences, ongoing efforts need to target the evaluation of fieldwork experiences in particular, and these experiences need to be sufficiently detailed to allow for comparisons to be explored. Ideally, it would be helpful to evaluate the impact of fieldwork experiences apart from coursework components (e.g. Golmic and Hansen Citation2012). Second, it seems important to trial more targeted assessments when evaluating fieldwork experiences, since it is possible that previous findings uncovering no (or small) changes to PSTs’ attitudes towards people with disability (e.g. Carroll, Forlin, and Jobling Citation2003; Tait and Purdie Citation2000) arise from the lack of instrument sensitivity to measuring change, rather than programmes lacking power to bring about such change. For example, given people vary in their attitudes towards people with different disabilities (Barr and Bracchitta Citation2015; Scior Citation2011), it may be more appropriate to use an instrument relating specifically to people with ID when it is relevant to do so, rather than an instrument relating to people with disability in general. Both these suggestions were tackled in the current study.

The current study

The aim of the current study was to evaluate an initiative called the Keep on Learning (KoL) programme and in doing so, contribute to the development of evidence-based practices for preparing beginning teachers for inclusion. The KoL programme came about due to concerns about the capacity of school-based placements to prepare PSTs for inclusive classrooms, and, in particular, with teaching students with ID. We (the authors) wanted to ensure PSTs were given practical and positive experiences of working with students with ID but could not guarantee this would occur if we relied on practicum arrangements with mainstream schools. We initiated discussions with the CEO of a local disability-support provider to explore ways of working together to better prepare beginning teachers for working in inclusive classrooms. The KoL programme evolved to include first-year preservice teachers, who were studying to become primary and secondary teachers (henceforth referred to as KoL tutors), working in pairs to tutor a young adult with ID from the local community in literacy or numeracy (henceforth referred to as KoL students).Footnote1

The KoL programme was one of a number of supplementary fieldwork programmes offered to PSTs in their first year of study, but it was the only one that specifically targeted inclusion and working with students with disability. In the first semester, PSTs who elected to be involved the KoL programme initially took part in three, one-hour, workshops that prepared them to work with young adults with ID. These workshops focussed on familiarising them with the structure of the KoL sessions and a sequence of learning activities for developing money skills (for details see Hopkins and O’Donovan Citation2019) and for building reading fluency (for details, see Hopkins and Round Citation2018).

In the second semester, KoL students travelled by bus from the disability-support organisation to the university campus. KoL students were mostly between the ages of 18–23 and had mild to moderate ID. After coming together for morning tea as a large group, two tutors worked with the same student for an hour each week for 10 weeks. The focus of the tutoring sessions (money or reading) was chosen by the student at the start of the programme. At the end of each weekly session, KoL tutors came together to reflect on and discuss their experiences with each other and the programme designers/coordinators (authors), and to share ideas for differentiating (adapting) the money or reading activities to suit their students’ level of knowledge, interests and disposition.

In order to build upon the existing body of research in the field, the Attitudes Toward Intellectual Disability (ATTID) questionnaire (Morin, Crocker et al. Citation2013) was utilised to investigate changes in PSTs’ attitudes toward persons with ID as a result of participation in the KoL programme. There were a number of advantages for utilising the ATTID questionnaire in the current study. The ATTID is considered a useful instrument for examining teachers’ attitudes towards people with ID (Arcangeli et al. Citation2020). It includes a measure of (dis)comfort when associating with persons with ID (referred to as the Discomfort Scale), which is similar to scales used by others to evaluate fieldwork experiences, except that it refers specifically to people with ID. The instrument also includes a measure of an individual’s inclination towards interacting with people with ID in workplace, community and educational settings (referred to as the Interaction Scale). This scale is somewhat similar to scales used by others in the field to measure attitudes towards inclusion, except that it specifically relates to people with ID and applies more broadly (i.e. not just to educational settings). It does, however, include two items that refer specifically to the inclusion of students with ID in regular classrooms: ‘Children with ID should have the opportunity of attending a regular elementary school’, and, ‘Adolescents with ID should have the opportunity of attending a regular secondary school’.

The ATTID questionnaire includes three additional scales: knowledge of the capacities and rights of people with ID (Capacities and Rights Scale); knowledge of the causes of ID (Knowledge of Causes Scale); and, sensibility toward persons with ID (Sensibility Scale). In addition to these five scales, the ATTID includes items relating to previous experience with people with ID, frequency of contact, and perceived quality of those relationships.

Research questions

The current study is one of only a few that have used an instrument specifically relating to attitudes towards people with ID to assess the impact of an applied experience in an initial teacher education programme (See McWhirter et al. Citation2016 for another). We therefore sought to investigate PSTs’ attitudes more broadly in Part 1 of the study, and how PSTs attitudes changed after participation in the KoL programme in Part 2 of the study. Importantly, Part 2 also included a control group of PSTs who volunteered to complete a second assessment, but who did not take part in the KoL programme, allowing us to specifically assess the impact of the fieldwork experience.

Data were collected and analysed to address four specific research questions relating to PSTs who were enrolled in the first year of study in an initial teacher education programme.

How do PSTs’ attitudes towards people with ID compare with the general (adult) population?

How does previous contact influence PSTs’ attitudes towards people with ID?

How do PSTs’ attitudes change as a result of tutoring a young person with ID (i.e. participating in the KoL programme)?

How do these changes, if any, compare to changes in attitude of PSTs who did not take part in the KoL programme?

Method

Participants

All first-year students (N = 143) who were enrolled in an undergraduate teacher education course at one suburban campus in a major Australian city were invited to be involved in Part 1 of the study. Of these, 96 PSTs took up the offer, representing 67% of first-year students of which 86 were female (90%) with the majority (92%) aged between 17 and 29 years of age. All were enrolled in education degrees to become qualified teachers but in three different areas of specialisation: 61 were enrolled in the primary/secondary specialisation; 11 in the early-years/primary specialisation; and, 23 in the primary/secondary (special education) specialisation. Data were missing for one respondent.

Part 2 of the study involved a smaller group of the same participants at a later point in time. This group included 39 PSTs enrolled in the primary/secondary specialisation, 18 of whom had volunteered as KoL tutors, and 21 who had not participated in the KoL programme and formed the control group.

Instrument

The ATTID questionnaire (Morin, Crocker et al. Citation2013) consists of 67 items with five Likert-type scale anchors ranging from totally agree to totally disagree. Around half the items refer to two characters, Dominique who has a moderate ID, and Raphael who has a more severe ID. The ATTID asks respondents to indicate how they would react if they encountered these individuals in different situations, with higher scores on the various items representing more negative attitudes toward people with ID (Morin, Crocker et al. Citation2013). Using a large random sample of Canadian adults (N = 1605), the ATTID was reported to have good construct validity, fair to very good internal consistency, and good test-retest reliability (Morin, Rivard, et al. Citation2013).

Data from all five scales were used in Part 1 to compare PSTs’ attitudes toward people with ID with the ATTID adult population benchmarks. Scores for the Discomfort Scale and the Interaction Scale were also examined in relation to PSTs’ previous experiences, and subsequently used in Part 2 to evaluate the impact of the KoL tutoring programme. Additionally, two single items from the Interaction scale were used to assess changes in PSTs’ attitudes towards inclusive education more specifically. Although not commonly used, single items have been shown to represent a psychometrically sound approach for assessing motivational-affective constructs (Gogol et al. Citation2014) and have been used in studies to evaluate changes in teachers’ willingness to teach in inclusive classes after training (e.g. Kisbu-Sakarya and Doenyas Citation2021).

Procedure

The research design and methods were approved by the ethics committee of the participating university (ID 6082). All PSTs involved in the study had received an explanatory statement and had provided written consent to have their data included. Questionnaires were completed by PSTs in the second week of their first semester at university prior to the start of the KoL programme, and again in the final weeks of their second semester, immediately after the KoL programme had been completed.

Data analysis

Each of the scale scores on the ATTID were calculated for individual participants according to the developers’ instructions (Morin, Crocker et al. Citation2013). Missing data were checked and handled using pairwise deletion (scores for each scale were calculated using the mean score of associated items with available data). This process resulted in a missing score for one person on the Sensibility Scale. Cronbach’s Alpha scores indicated that the overall internal consistency of the collected data was sound. Scale reliability scores were as follows: Discomfort (α = .91); Capacity and Rights (α = .89); Knowledge of Causes (α = .75); Interaction (α = .92); and, Sensibility (α = .75).

In Part 1, participants’ scores were compared with mean scores reported by Morin, Rivard, et al. (Citation2013), which were treated as estimates for the adult population. In Part 2, a repeated-measures design was utilised to compare scores from the Discomfort Scale and the Interaction Scale for KoL tutors as well as for PSTs who had not participated in the KoL programme. It should be noted that participants were in their first year of study and had not yet completed a specific coursework unit on inclusion (which was scheduled for their second year); however, inclusive content may have been infused in some first-year coursework units. As both groups were enrolled in the same coursework units, differences in outcomes between the KoL and control cohorts could fairly be attributed to participation in the KoL programme as it was the substantive difference in their course experiences.

Results

Part 1: investigating the attitudes of PSTs toward people with ID

Out of 96 participants enrolled in their first year of undergraduate teacher education course, 10 PSTs (10.4%) indicated they had never had contact with a person with ID. Of the remaining participants who had had some contact (89.6%), these interactions most commonly had occurred at school (64.1%), as a result of participating in leisure or sporting activities (53.8%), through volunteer work (32.5%), and/or through relationships with extended family members (27.5%). Overall, mean scores for the five factors of the ATTID suggested PSTs had relatively positive attitudes toward people with ID for Factors 1, 2, and 3, and moderately neutral attitudes for Factors 4 and 5 (see ).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for ATTID factors for PSTs and comparison group.

Compared to the ATTID adult sample, these PSTs exhibited more positive attitudes on three scales, including a medium effect on the Capacity and Rights Scale [t(95) = −4.79, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.4], a small effect on the Sensibility Scale [t(94) = −2.82, p < .01, Cohen’s d = 0.3], and a medium effect on the Knowledge of Causes Scale [t(95) = −6.41, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.6]. PSTs exhibited less positive attitudes on the Discomfort Scale (i.e. they felt more uncomfortable around people with ID) with a small effect size [t(95) = 2.47, p < .05, Cohen’s d = 0.3]. Differences were not significant for the Interaction Scale [t(95) = −1.30, p = .20].

Scores for the Discomfort Scale and the Interaction Scale were compared across participants according to two background variables: frequency of contact with people with ID; and, perceived quality of relationships with people with ID. Data pertaining to quality of relationships were available for 82 participants, with four participants having missing data, nine participants responding ‘not applicable’ due to having not previously met a person with ID, and one participant recording ‘very bad’ relations.

Assumptions for normality were met for participants’ scores for the Interaction factor, but not for the Discomfort factor. In particular, a marked floor effect was evident for the Discomfort factor, with 15 respondents (15.6%) receiving a score below 1.2, indicating very positive attitudes (with 1.0 being the lowest, most positive score possible). Where appropriate, an ANOVA with Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis was conducted to compare the mean scores for each factor with respect to the background variables; elsewhere non-parametric tests were conducted alongside parametric tests and the results compared. As these comparisons did not yield different results, only results from parametric testing are reported here. Summary statistics are reported in .

Table 2. Attitudes in relation to ATTID factors and background variables.

With regard to frequency of previous contact with people with ID, significant differences were evident showing medium effect sizes for the Discomfort factor [F(3,92) = 4.76, p < .01, η2p = .13] and the Interaction factor [F(3,92) = 3.54, p < .05, η2p = 0.10]. Post hoc tests indicated that there were significant variations on both scales between participants who indicated that they had never or sometimes interacted with a person with ID, compared to participants who had contact very often. With regard to perceived quality of relationships with people with ID, significant differences were evident showing medium effect sizes for the Discomfort factor [F(2,79) = 3.93, p < .05, η2p = .09 ] and the Interaction factor [F(2,79) = 5.28, p < .01, η2p = 0.12]. Post hoc analyses indicated that on both scales, participants who perceived their relationships to be excellent showed more positive attitudes compared to those who perceived them to be neutral. These findings provide converging evidence of the validity of the Discomfort and Interaction scales.

Part 2: investigating changes in attitudes

Pre- and post-programme data were collected from 39 participants, some of whom had experienced being KoL tutors for ten weeks (n = 18), while the remainder had not (n = 21). Descriptive statistics for the two ATTID factors are shown in .

Table 3. Attitudes towards People with ID in Relation to ATTID Factors by Group and Time.

Assumptions of normality were checked for differences in factor scores for both groups. When these assumptions were met, a paired t-test was employed to compare factor scores at Time 1 and Time 2. When these assumptions were not met, an equivalent non-parametric test (Wilcoxon) was also conducted and results from both tests were compared. As these comparisons yielded similar results, only the results of the parametric tests are reported here.

A paired t-test indicated there was a significant decrease with a medium effect size over time on the Discomfort scale for the KoL group [t(17) = 2.76, p < .05, Cohen’s d = 0.5] and not for the control group [t(20) = −0.02, p = .99]. This finding indicates that participation in the KoL programme was effective in decreasing PSTs’ discomfort when interacting with people with ID with a medium effect size.

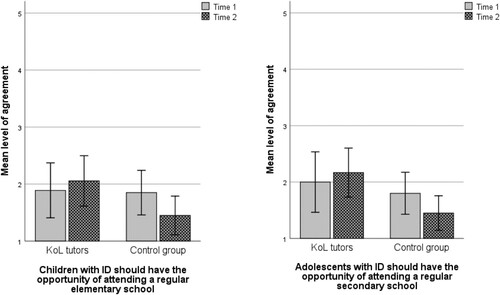

Differences in scores on the Interaction scale were not significant for the KoL group [t(17) = 0.16, p = .87] or the control group [t(20) = 0.13, p = .90]. However, given the context of PST respondents, their responses to two items within this Factor were examined (see ). These items related to the inclusion of students with ID in regular classrooms: ‘Children with ID should have the opportunity of attending a regular elementary school’; and, ‘Adolescents with ID should have the opportunity of attending a regular secondary school.’

Figure 1. Bar charts showing mean scores for KoL tutors and control group on two items. Note. Lower scores signify higher agreement as presented in the ATTID (1 = totally agree, 5 = totally disagree). Error bars show ± 2.

At the start of the year, no significant differences were evident between KoL tutors and PSTs in the control group, in relation to the elementary school item [t(37) = 0.11, p = .92] or the secondary school item [t(37) = 0.61, p = .55]. After participation in the KoL programme, significant differences were evident indicating KoL tutors were less likely to endorse these statements, suggesting a medium effect size for the elementary school item [t(36) = 2.20, p < .05, Cohen’s d = 0.7] and a large effect size for the secondary school item [t(36) = 2.73, p < .05, Cohen’s d = 0.9]. One person in the control group had missing data for both items. Participants’ response patterns indicated that after completing their first year of a teaching degree, KoL tutors were less likely to agree with statements pertaining to inclusion in schools, whereas PSTs in the control group were more likely to agree (see ).

Discussion

The first part of this study involved an investigation into PSTs’ attitudes toward individuals with ID. Few studies have specifically compared PSTs’ attitudes towards people with ID with those of the general public. PSTs’ attitudes were compared with those reported by Morin, Rivard, et al. (Citation2013) for a large sample of Canadian adults. The results indicated that PSTs generally held similar or more positive attitudes than this benchmark group, with one exception; PSTs expressed more discomfort at the idea of interacting with a person with ID. This finding could reflect the fact that PSTs were generally younger and perhaps less socially confident than the benchmark cohort. Since nearly 90% of PSTs had reported previous contact with people with ID, it was unlikely to result from a lack of encounters. Further investigation found that PSTs who had more frequent contact with people with ID and considered their relationships with people with ID of higher quality, were more comfortable with, and more inclined towards, interacting with people with ID. These findings are similar to those reported by McManus, Feyes, and Saucier (Citation2010), and Barr and Bracchitta (Citation2015), who investigated attitudes among undergraduate students studying psychology.

In the second part of this study, a repeated-measures design was utilised to evaluate the impact of a fieldwork experience that was unique in many ways, as it required teaching a person with ID over a sustained period of time (10 weeks). This contrasts with many of the fieldwork experiences evaluated in the literature that are dated and are based on social experiences rather than teaching experiences; or on very limited teaching experiences (e.g. one lesson). As a result, the findings, which are elaborated below, make a significant contribution to the field in as much as they represent an evaluation of a contemporary ‘hands-on’ fieldwork experience.

Findings from the second part of the study indicated participation in the KoL programme decreased the level of discomfort PSTs reported when interacting with a person with ID. While this was a positive outcome for the KoL programme, it was noted that many PSTs started their teaching degree with very positive attitudes towards interacting with people with ID. Thus, measuring this attribute of PSTs resulted in floor effects in the data (indicating highly positive attitudes) thereby restricting differences in scores and the types of analyses that could be employed. The problem of finding instruments that provide suitable variations in scores (Forlin and Chambers Citation2011; Tait and Purdie Citation2000) is one that continues to hamper the field.

The subsequent collection of PSTs’ responses to the same questionnaire towards the end of the first year meant that participants had been exposed to equivalent course content, with some involved in the KoL programme and the non-KoL participants acting as an effective control group. An unexpected finding was that PSTs who participated in the KoL programme were less inclined to support the idea of inclusive education for children and adolescents with ID; whereas, the opposite trend was noted for PSTs who had not participated in the programme.

This finding could reflect a weakness in the KoL programme itself – its design and/or delivery. However, an analysis of qualitative data based on interviews with KoL tutors (in a separate study) revealed PSTs were overwhelmingly positive about their involvement in the programme (see Hopkins, Round, and Barley Citation2018). PSTs had valued working together with a peer and debriefing with other tutors at the end of each session, and had enjoyed the rapport that had developed with students. They had learned strategies for differentiating the learning activities, which they felt had been successful in promoting motivation and task engagement, and improving learning outcomes to meet the individual needs of their student. As one PST remarked, what they had learned was transferrable to all students they would be teaching:

In every mainstream school there’s going to be students with intellectual disabilities, there’s going to be students with different learning needs, whether or not they’re classified as being intellectually disabled … When you’re in a mainstream school you will be dealing with students with such a diverse range of needs. It’s prepared us for that. (Hopkins, Round, and Barley Citation2018, 11)

Alternatively, the finding that PSTs were less inclined to support the idea of inclusive education after partaking in the KoL programme (and the opposite for PSTs in the control group), might be suggestive of a difference in expectations arising from course-based education experiences versus practical teaching experiences. Van Laarhoven et al. (Citation2007) also found that teacher candidates who were exposed to course content agreed with similar inclusive statements more readily than teacher candidates who were exposed to the same course content but also had experience teaching in an inclusive setting. It is, perhaps, a phenomenological truism that course content alone is not able to convey the nature of the (surmountable) difficulties involved in teaching children of all abilities. Whereas, when PSTs have first-hand experience of teaching students with ID, their original agreeableness towards inclusion may be tempered by a better understanding of the complexity of teaching in an inclusive classroom. However, while course content and supplementary fieldwork experiences that underemphasise the difficulties of inclusion are likely to underprepare PSTs for inclusive classrooms, experiences that ‘over prepare’ PSTs may also be counterproductive. Participating PSTs may have felt that, in mainstream schools, they would not have the time to individualise learning like they did in the KoL programme. A similar point was made by Avarez McHatton and Parker (Citation2013) to explain why special education majors were less likely to endorse inclusion over time. There is little discussion in the literature about whether preparing beginning teachers for inclusion includes preparing them to provide (design, orchestrate, assess etc.) individualised learning plans. We would welcome more discussion and further investigation into how practical experiences might be designed to suitably prepare PSTs for individualised learning.

There are at least three limitations of the present study that require noting. First, PSTs were Australian university students and the ATTID was tested with a Canadian adult population. It is possible that cultural differences make comparisons between the two groups difficult. However, in broad terms, Australia and Canada overlap in many important cultural ways such as language, civic structures, and Anglo-European histories. Furthermore, the observed reliability scores suggest that overall the survey performed in a way similar to the reliability observed by the developers, so it seems reasonable to assume that the results are plausibly comparable. Second, only the ATTID instrument was utilised for assessing PSTs’ attitudes towards people with ID. It may be that other instruments for assessing PSTs’ attitudes are more suitable for measuring the impact of fieldwork experiences. Third, the size of the intervention group and control group were small and the groups were not matched on factors such as age or previous contact with people with ID. These factors may have had some bearing on the findings.

Despite these limitations, findings from the current study indicate that assessing changes in PSTs’ attitudes may not be the most useful way of evaluating the impact of fieldwork experiences. The utility of other instruments used for assessing change will need to be investigated, including, for example, assessments of self-efficacy (e.g. O’Neill Citation2016; Peebles and Mendaglio Citation2014). It may be that new instruments are needed. If so, these instruments will need to provide sensitive measures of PSTs’ awareness of students’ special needs (Paris, Nonis, and Bailey Citation2018), their recognition of the unique capabilities of students with disability (Chakravarthi and White-McNulty Citation2020), and their knowledge and skills associated with differentiating curriculum materials for students with ID (Kandimba, Mandyata, and Simalalo Citation2023; Van Geel et al. Citation2019).

In closing, it is important to highlight the pivotal role that teachers play in influencing the community at large by promoting productive attitudes towards people with ID. PSTs in this study had most commonly encountered people with ID previously at school (64.1%) – presumably, the school they had attended – or perhaps a school at which their own children attend. These encounters appeared to have contributed to positive attitudes overall, and these PSTs were preparing to enter the teaching profession where they too would have opportunities to play a role in promoting positive relations between people of all abilities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sarah Hopkins

Sarah Hopkins has many years of experience in primary and secondary teacher education. Her research interests include teacher education, assessment design and testing, mathematics education and computational fluency.

Richard O’Donovan

Richard O'Donovan is an experienced secondary teacher and co-founded Hands on Learning Australia - an NFP organisation specialising in helping schools engage vulnerable students. His research interests include Rasch analysis, mathematics education and hope in education.

Pearl Subban

Pearl Subban researches in the field of inclusive education, differentiated instruction and student diversity. Her teaching experience spans both higher education and secondary school education.

Penny Round

Penny Round has been working in the area of students with special needs for 25 years. Her research interests include teacher education, students with special needs and gifted education.

Notes

1 The KoL Programme ran for five consecutive years (2015-2019) but stopped due to COVID-19 and has not yet recommenced. To date, the program has involved over 170 tutors and 80 KoL students.

References

- Aprile, K. T, and B. A. Knight. 2020. “Preservice Teachers’ Perceptions of Inclusive Education: The Reality of Professional Experience Placements.” Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education 44 (2): 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2020.7.

- Arcangeli, L., A. Bacherini, C. Gaggioli, M. Sannipoli, and G. Balboni. 2020. “Attitudes of Mainstream and Special-Education Teachers Toward Intellectual Disability in Italy: The Relevance of Being Teachers.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (19): 7325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197325.

- Avaraz McHatton, P., and A. Parker. 2013. “Purposeful Preparation: Longitudinally Exploring Inclusion Attitudes of General and Special Education pre-Service Teachers.” Teacher Education and Special Education 36 (3): 186–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413491611.

- Avramidis, E., and B. Norwich. 2002. “Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Integration / Inclusion: A Review of the Literature.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 17 (2): 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250210129056.

- Barr, J. J., and K. Bracchitta. 2015. “Attitudes Toward Individuals with Disabilities: The Effects of Contact with Different Disability Types.” Current Psychology 34 (2): 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9253-2.

- Carroll, A., C. Forlin, and A. Jobling. 2003. “The Impact of Teacher Training in Special Education on the Attitudes of Australian Preservice General Educators Towards People with Disabilities.” Teacher Education Quarterly 30 (3): 65–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/23478441.

- Chakravarthi, S., and L. White-McNulty. 2020. “Let's Have Lunch: Preparing pre-Service Teachers to Support Students with Disabilities via Authentic Social Interactions.” International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 32 (2): 240–250. http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/.

- de Boer, A., S. J. Pijl, and A. Minnaert. 2010. “Regular Primary Schoolteachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education: A Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 15 (3): 331–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903030089.

- Engelbrecht, P., M. Oswald, E. Swart, and I. Eloff. 2003. “Including Learners with Intellectual Disabilities: Stressful for Teachers?” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 50 (3): 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912032000120462.

- Forlin, C., and D. Chambers. 2011. “Teacher Preparation for Inclusive Education: Increasing Knowledge but Raising Concerns.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 39 (1): 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.540850.

- Forlin, C., M. Keen, and E. Barrett. 2008. “The Concerns of Mainstream Teachers: Coping with Inclusivity in an Australian Context.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 55 (3): 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120802268396.

- Gogol, K., M. Brunner, T. Goetz, R. Martin, S. Ugen, U. Keller, A. Fischbach, and F. Preckel. 2014. ““My Questionnaire is Too Long!” The Assessments of Motivational-Affective Constructs with Three-Item and Single-Item Measures.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 39 (3): 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.04.002.

- Golmic, B. A., and M. A. Hansen. 2012. “Attitudes, Sentiments, and Concerns of Pre-Service Teachers After Their Included Experience.” International Journal of Special Education 27 (1): 27–36.

- Hopkins, S., and R. O’Donovan. 2019. “Using Complex Learning Tasks to Build Procedural Fluency and Financial Literacy for Young People with Intellectual Disability.” Mathematics Education Research Journal, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-019-00279-w.

- Hopkins, S., and P. Round. 2018. “Building Stronger Teacher Education Programmes to Prepare Inclusive Teachers.” In Re-imagining Professional Experience in Initial Teacher Education, edited by A. Fitzgerald, G. Parr, and J. Williams, 55–66. Springer.

- Hopkins, S., P. Round, and K. Barley. 2018. “Preparing Beginning Teachers for Inclusion: Designing and Assessing Supplementary Fieldwork Experiences.” Teachers and Teaching 24 (8): 915–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1495624.

- Kandimba, H. C., J. Mandyata, and M. Simalalo. 2023. “Teachers’ Understanding of Curriculum Adaptation for Learners with Moderate Intellectual Disability in Zambia.” European Journal of Special Education Research 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.46827/ejse.v9i1.4653.

- Killoran, I., D. Woronko, and H. Zaretsky. 2014. “Exploring Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (4): 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2013.784367.

- Kisbu-Sakarya, Y., and C. Doenyas. 2021. “Can School Teachers’ Willingness to Teach ASD-Inclusion Classes Be Increased via Special Education Training? Uncovering Mediating Mechanisms.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 113:103941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103941.

- Lancaster, J., and A. Bain. 2010. “The Design of Pre-Service Inclusive Education Courses and Their Effects on Self-Efficacy: A Comparative Study.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 38 (2): 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598661003678950.

- Lautenbach, F., and A. Heyder. 2019. “Changing Attitudes to Inclusion in Preservice Teacher Education: A Systematic Review.” Educational Research 61 (2): 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1596035.

- McManus, J. L., K. J. Feyes, and D. A. Saucier. 2010. “Contact and Knowledge as Predictors of Attitudes Toward Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 28 (5): 579–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510385494.

- McWhirter, P. T., J. A. Brandes, K. L. Williams-Diehm, and S. Hackett. 2016. “Interpersonal and Relational Orientation among pre-Service Educators: Differential Effects on Attitudes Toward Inclusion of Students with Disabilities.” Teacher Development 20 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2015.1111930.

- Morin, D., A. G. Crocker, R. Beaulieu-Bergeron, and J. Caron. 2013. “Validation of the Attitudes Toward Intellectual Disability – ATTID Questionnaire.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 57 (3): 268–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01559.x.

- Morin, D., M. Rivard, A. G. Crocker, C. P. Boursier, and J. Caron. 2013. “Public Attitudes Towards Intellectual Disability: A Multidimensional Perspective.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 57 (3): 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12008.

- O’Neill, S. C. 2016. “Preparing Preservice Teachers for Inclusive Classrooms: Does Completing Coursework on Managing Challenging Behaviours Increase Their Classroom Management Sense of Efficacy?” Australasian Journal of Special Education 40 (2): 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2015.10.

- Paris, L. F., K. P. Nonis, and J. Bailey. 2018. “Pre-service Arts Teachers’ Perceptions of Inclusive Education Practice in Western Australia.” International Journal of Special Education 33 (1): 3–20.

- Peebles, J. L., and S. Mendaglio. 2014. “The Impact of Direct Experience on Preservice Teachers’ Self-Efficacy for Teaching in Inclusive Classrooms.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (12): 1321–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2014.899635.

- Scior, K. 2011. “Public Awareness, Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 32 (6): 2164–2182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.07.005.

- Shade, R. A., and R. Stewart. 2001. “General Education and Special Education Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Inclusion.” Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth 46 (1): 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459880109603342.

- Sharma, U., C. Forlin, and T. Loreman. 2008. “Impact of Training on Pre-Service Teachers’ Attitudes and Concerns About Inclusive Education and Sentiments About Persons with Disabilities.” Disability & Society 23 (7): 773–785. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590802469271.

- Stella, C. S. C., C. Forlin, and A. M. Lan. 2007. “The Influence of an Inclusive Education Course on Attitude Change of pre-Service Secondary Teachers in Hong Kong.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 35 (2): 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660701268585.

- Swain, K. D., P. D. Nordness, and E. M. Leader-Janssen. 2012. “Changes in Preservice Teacher Attitudes Toward Inclusion.” Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth 56 (2): 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2011.565386.

- Tait, K., and N. Purdie. 2000. “Attitudes Toward Disability: Teacher Education for Inclusive Environments in an Australian University.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 47 (1): 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/103491200116110.

- Tristani, L., and R. Bassett-Gunter. 2020. “Making the Grade: Teacher Training for Inclusive Education: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 20 (3): 246–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12483.

- Van Geel, M., T. Keuning, J. Frèrejean, D. Dolmans, J. van Merriënboer, and A. J. Visscher. 2019. “Capturing the Complexity of Differentiated Instruction.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 30 (1): 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1539013.

- Van Laarhoven, T. R., D. D. Munk, K. Lynch, J. Bosma, and J. Rouse. 2007. “A Model for Preparing Special and General Education Preservice Teachers for Inclusive Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 58 (5): 440–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487107306803.

- Woodcock, H. K. (2012). “Does Study of an Inclusive Education Subject Influence pre-Service Teachers’ Concerns and Self-Efficacy About Inclusion?” Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37 (6): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2012v37n6.5