ABSTRACT

This paper explores education professionals’ interpretations of national school exclusion policy in England and the different ways in which schools use and do school exclusion. Drawing on semi-structured interview data collected as part of my DPhil research into the enactment of school exclusion policy in one local authority in England, I investigate the extent to which national policy is understood as a clear set of imperatives or open to interpretation, and the perceived need for consistency versus flexibility in its application. I also explore how accountability frameworks and other national and local policies, including behaviour, safeguarding, and special educational needs and disability policies, are seen to interact with and influence how decisions around school exclusion are made – specifically what and when mitigating factors are considered – and highlight other contextual dimensions (situated, professional, material and external), which are seen to weave together and influence a school’s position towards school exclusion and their sense- and decision-making. In so doing, I reveal how national school exclusion policy becomes variously recontextualised and translated into practice at the local level.

Introduction

Recent reports have drawn attention to variations in school exclusion practice in England with schools being found to adopt widely differing thresholds for issuing fixed periodFootnote1 (short-term suspensions) and permanent exclusions (Kulz Citation2015; Timpson Citation2019). Timpson (Citation2019, 11) states that ‘what will get a child excluded in one school may not be seen as grounds for exclusion in another.’ In some ways this is unsurprising given the discretionary regime underpinning the governing statutory provision for school exclusions, in which decision-makers exercise ‘supported autonomy’ (Ferguson Citation2019, 7). When conducting the current study, the 2017 statutory guidance on school exclusion was in place and made clear that ‘[t]he Government supports head teachers in using exclusion as a sanction where it is warranted’ (Department for Education (DfE) Citation2017, 6). The guidance set out that the decision to permanently exclude can only be made by the headteacher on ‘disciplinary grounds’ (DfE Citation2017, 8) and ‘should only be taken:

in response to a serious breach or persistent breaches of the school’s behaviour policy; and

where allowing the pupil to remain in school would seriously harm the education or welfare of the pupil or others in the school’ (DfE Citation2017, 10).Footnote2

The guidance also outlined that the decision to permanently exclude must be made in line with administrative law and ‘should only be used as a last resort’ after all other options have been exhausted (DfE Citation2017, 6). Moreover, headteachers must not discriminate and must comply with the Equality Act Citation2010 and with their statutory duties in relation to Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) under the SEND Code of Practice (DfE and Department of Health (DoH) Citation2015), including making reasonable adjustments.

The statutory guidance includes guides to the law, which outline the legal requirements that must be met and followed in the school exclusion process, and statutory guidance which those involved in the exclusion process must have regard to. In this context, the phrase ‘must have regard’ ‘does not mean that the sections of statutory guidance have to be followed in every detail, but that they should be followed unless there is a good reason not to in a particular case’ (DfE Citation2017, 3 emphasis added).Footnote3

Ferguson and others have explored how the discretion afforded to headteachers plays out in how they interpret and apply the law. Ferguson (Citation2019) suggests that the discretionary regime has resulted in cases of headteachers disregarding or circumventing particular formal positions and adopting alternative policies and practices, ‘principally if they consider that the “best interests” of the affected pupil and others in the school lie elsewhere’ (Ferguson and Webber Citation2015, 38). Kulz (Citation2015), Ferguson (Citation2019) and Timpson (Citation2019) have also argued that the lack of clarity in the statutory guidance, and join-up between policies, has led to confusion and the playing off of different policy priorities and legal requirements. This lack of join-up, Ferguson (Citation2019, 19) argues, has ‘made it harder for non-lawyers to consistently and justifiably exercise their legally-bounded decision-making, such as determining what qualifies as a ‘serious breach’ or ‘persistent breaches’ of the school’s behaviour policy’ and has resulted in the existence of ‘numerous grey areas’ (Kulz Citation2015, 6) where it is questionable whether permanent exclusion is genuinely being used as a ‘last resort’.

Reflecting on the potential reasons lying behind the varying thresholds adopted by schools, Kulz (Citation2015) and Timpson (Citation2019) have suggested the possible impact of school leadership, behaviour management systems, school behaviour policies and the levels of deprivation and need in different schools. Many authors, including Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson (Citation2006) in an earlier paper published in this journal, and others in this current special issue, have also drawn attention to the ways in which conflicting policy agendas (e.g. standards versus inclusion; equity versus excellence) and motives underpinning, for example, school league tables, inspection regimes, the reduction of specialist services and a lack of accountability around exclusion, may in practice form ‘perverse incentives’ for schools to formally and informally exclude pupils, with increasing attention being paid to issues of unlawful exclusion and off-rollingFootnote4 (Children’s Commissioner Citation2013, 47; see also Daniels, Thompson, and Tawell Citation2019; Done, Knowler, and Armstrong Citation2021; Ferguson Citation2019; Gazeley Citation2020; Partridge et al. Citation2020).

While the above studies provide helpful insights into lay professionals’ understandings of school exclusion legislation and potential reasons behind the adoption of different exclusion thresholds in schools in England, less is known about how different contextual factors weave together in complex assemblages to inform how national school exclusion policy is enacted at the local level in and across different settings. Building on concepts from the theory of policy enactment developed by Ball, Maguire, and Braun (Citation2012) as well as Cole’s (Citation1996, 143) understanding of context as something that ‘weaves together’, and interview data collected as part of my ESRC funded DPhil study on the enactment of school exclusion policy, I provide a nuanced and situated account of how national school exclusion policy is interpreted, translated, recontextualised and enacted by education professionals in one Local Authority (LA) in England, and the contextual dimensions that influence decision-making around school exclusion, including competing policy priorities. My overarching research questions were:

How is national school exclusion policy interpreted, translated, recontextualised and enacted at the local level in and across different settings?

What contextual factors influence the enactment of school exclusion policy?

Conceptual framework

This study is situated within the tradition of policy enactment research (Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012), in which policies are understood to be ‘interpreted and translated by diverse policy actors as they engage in making meaning of official texts for specific contexts and practices’ (Singh, Thomas, and Harris Citation2013, 466). Interpretation refers to initial, mainly rationalistic, readings, decodings and sense-makings, whereby actors ask of a text ‘what does this mean to us?’ These interpretations are then instantiated, elaborated and translated as strategies in various recontextualising contexts, including for example, LAs, schools and multi-agency meetings (Ball et al. Citation2011; Singh, Thomas, and Harris Citation2013). Singh, Thomas, and Harris (Citation2013, 466) argue that ‘[t]he discursive communities of these specific contexts regulate which aspects of policy texts are privileged and/or ‘filtered out’.’ In other words, Maguire, Braun, and Ball (Citation2015, 490) argue, ‘where you stand depends on where you sit.’ In this paper, I draw on the above concepts to answer my first research question and explore the extent to which national school exclusion policy is understood as a clear set of imperatives or open to interpretation by education professionals.

To answer my second research question, I utilise Braun et al.’s (Citation2011, 588) following four contextual dimensions to explore what contextual factors influence the enactment of school exclusion policy:

Situated contexts: The historical and locational aspects of context, including school intake and setting.

Professional contexts: School and teacher values, commitments, experiences and school policy management.

Material contexts: The physical, material and visual aspects of a school including buildings and budgets, levels of staffing, available technologies and surrounding infrastructure.

External contexts: The degree and quality of LA ‘support, pressures and expectations from [the] broader policy context, such as Ofsted ratings, league table positions, legal requirements and responsibilities.’

While separating the four contextual dimensions is analytically helpful, in this paper, I take the position that context is something that ‘weaves together’ (Cole Citation1996, 143) and it is the complex assemblage of different factors which results in variation in how national school exclusion policy becomes enacted at the local level.

Research design

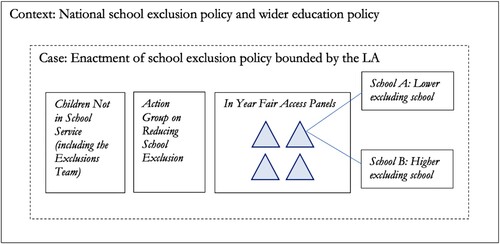

Given that a central adage of the theory of policy enactment is the need to ‘take context seriously’ (Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012, 19), an exploratory case study design was chosen for the current study. The data drawn on in this paper are from my DPhil study in which I sought to explore a process – the enactment of national school exclusion policy – bounded within one LA in England. The specific LA in which the current study is bounded was chosen because reducing rates of exclusion had become a priority focus for the LA following a recent inspection, which provided opportunities to explore how school exclusion policy was being enacted across different settings. During the course of my fieldwork, I identified a number of embedded units in which the enactment of school exclusion policy was taking place, and therefore adapted Yin’s (Citation2009) embedded single-case design (see ).

Data collection

Data collection involved unstructured ethnographic observations in the different embedded units depicted in over a 16-month period (May 2019–September 2020)Footnote5, i.e. LA offices, Action Group meetings, In Year Fair Access Panels (IYFAPs)Footnote6 and two schools (one identified as a higher excluding school and the other as a lower excluding school), alongside semi-structured in-depth interviews with a range of key stakeholders from across the different embedded units (n = 60) and document analysis. The interview questions were informed by the literature on policy enactment as well as my observations of different activities and were constructed using open-ended questions to allow interviewees to respond in their own terms and conducted in a conversational style (Kvale Citation1996). In this paper, I draw on interview data from headteachers (n = 7) and teachers (n = 27) working in 16 mainstream secondary schools (including the two embedded schools) and two alternative provision (AP) settings, the majority of whom were members of their school’s Senior Leadership Team (SLT). One of the interviews was a paired interview. The interviewees were asked to reflect on the national and LA policies on school exclusion as well as their own school’s policy, factors influencing the use of school exclusion and, where relevant, their involvement in the IYFAPs and Action Group meetings.

Ethical clearance was granted by the Department of Education, University of Oxford Departmental Research Ethics Committee (Reference: ED-CIA-19-063) and all interviewees gave consent prior to being interviewed. The interviews were conducted in schools, AP settings and latterly online due to Covid-19 restrictions, and the majority were audio recorded. All conversations were transcribed or written up following the interviews. Identifying information has been removed to ensure anonymity and names of people, services and groups have been replaced with pseudonyms.

Coding process

For the analysis presented in this paper, I used an eclectic coding method (Saldaña Citation2016) and followed Srivastava and Hopwood’s (Citation2009) practical iterative framework for qualitative data analysis where I moved back and forth between the data and theory. In this way, the coding was both deductive, drawing on the theoretical concepts outlined in the conceptual framework section of this paper, and inductive or data driven.

Findings

The following section presents three themes identified from the analysis: 1. Is it black and white? 2. ‘Where you stand depends on where you sit’ and 3. Contradictions, perverse incentives, unintended consequences and trade-offs, as well as their related subthemes.

Is it black and white?

Discussions of whether the national school exclusion policy, specifically the 2017 statutory guidance, is and should be ‘black and white’ were recurrent in the interviews. On the one hand, a number of the interviewees felt that the guidance provided ‘real clarity’ (Teacher 22, SLT, School M) in terms of the headteacher’s right to exclude, and the legal requirements around school exclusion that schools had to ‘conform to’ (Teacher 11, SLT, School F) and ‘abide by’ (Teacher 8, School P), as well as the roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders:

… on the whole I think it’s pretty straightforward. It’s pretty black and white. (Teacher 17, SLT, School C)

… I think that is where there's a weakness in the policy because it pretty much just says permanent exclusions exist … you know this is the legal remit for a permanent exclusion. But then there isn't really anything within that policy to suggest that actually there is stuff that should happen to make it less likely that another permanent exclusion happens. (Headteacher 3, School G)

I think the difficulty is the persistent disruptive behaviour, define that. It's a catch all for anything in school … it's the one that is the most woolly for anybody to try and interpret … because my definition of disruptive behaviour will be different to somebody else's. (Teacher 10, SLT, School H)

You have to see shades of grey

While some teachers talked about how their schools had adopted zero tolerance policies whereby certain incidents involving for example, drugs or weapons would warrant a permanent exclusion, others described how their schools had taken a more contextualised approach:

… some schools are very [pause] you know yeah … zero tolerance … if you cross that it's black and white, you're out. Other people would look at it and go well, actually, there's a context behind this, let's look at that, investigate it, and then we'll make a decision. (Teacher 10, SLT, School H)

It's pretty much zero tolerance [for drugs]. Yeah. I mean … I think in every situation you have to be prepared to see shades of grey, so … it isn't without any understanding of what was the context. It's the same for … weapons, same for knives as well. (Teacher 24, SLT, School B)

A number of respondents also spoke about needing to take into consideration responsibilities set out in other national and school policies and legislation when making the decision to exclude, for example, the requirement to make reasonable adjustments for children with SEND (Equality Act Citation2010; DfE and DoH Citation2015). Many schools had processes in place whereby the decision to suspend or permanently exclude was reviewed by key members of staff, including, for example, the Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO), Designated Safeguarding Lead and members of staff with particular responsibilities for Looked After Children:

… we have some certain … processes that we would go through … if a child is SEN or if a child has a pupil profile, or if a child is [Pupil Premium; PP] … So, everything is looked at [at] an individual level, there is no set a fire alarm off, get a three-day fixed term exclusion. Punch someone in the face, get a five-day fixed term exclusion. It just doesn't work like that whatsoever, it's all down to discretion. (Headteacher 3, School G)

So, I would say in our school, no. But I know other schools where it would … I'm a firm believer that you are trying to bring up children to be moral citizens … of the country, so therefore wrong is wrong in my eyes even if you've got a special need, you still need to make … sure that child understands that what they've done is wrong, so therefore I don't feel that you know there … should be any lesser consequence for them. (Teacher 3, School A)

Safeguarding policy was also seen to inform the use of school exclusion, with some schools stating that they would not exclude a student if they knew that there were problems at home, that the student would be unsupervised, or there were known safeguarding risks in the community (e.g. risk of exploitation):

I think the other part as well for us would be with a child who's maybe particularly on Child Protection, or part of a Child in Need Plan or even a TAF [Team Around the Family], and I think that has an influence on our decisions around exclusion for a young person … and I think that's right. Because no matter what's happening here, we know we're possibly excluding them to somewhere that's unsafe. (Teacher 23, SLT, School A)

Returning to the discussion around the importance of consistency versus flexibility, by seeing shades of grey and considering individual circumstances in their decision-making, respondents were more likely to adopt practices that aligned with what Whitaker (Citation2021, 55) termed ‘flexible consistency,’ or as Teacher 4 (SLT, School O) described: ‘a flexible boundaried approach’.

Overall, it was felt that the nature of the national school exclusion policy meant that it could be interpreted in different ways and could be read selectively to achieve particular ends:

Some schools are evidently more inclusive than others … and I think that's potentially a weakness of the document. I think that it allows some people to hold it very black and white and say right actually this student stepped over the line therefore they're excluded. Other people will say ok, well they're there, however we have a moral responsibility to keep that student in school and educate them and you know that depends which side you sit on that I guess. (Teacher 10, SLT, School H)

‘Where you stand depends on where you sit’

Drawing on the phrase ‘where you stand depends on where you sit’ used by Maguire, Braun, and Ball (Citation2015, 490) in their study of the social construction of policy enactments in the (English) secondary school, in this section, I unpick the situated, professional, material and external contexts that education professionals identified as influencing how school exclusion policy is done.

Situated context

In terms of situated factors, school type and intake and ‘catchment and context’ (Teacher 5, SLT, School B) were seen to influence the enactment of national school exclusion policy at the local level, and a school’s tolerance level or threshold for permanent exclusion:

… the thing that leads schools to a permanent exclusion is what’s going on in the makeup of the school in the first place as to kind of where your tolerance level for all of these things sits. (Teacher 17, SLT, School C)

… we are a mainstream school. And I think that's where some of the issues perhaps that we have around exclusion come out because we have more children presenting us with challenging behaviours … than we have alternative provision to cope with. (Teacher 24, SLT, School B)

Where a school is on their improvement journey

Alongside demographic factors such as levels of need in the local community, school factors such as Ofsted ratings and leadership stability were seen to influence rates of exclusion:

I think that often high excluding schools would be in areas of need such as ours where there's deprivation. They are often schools that have suffered turbulence in leadership as well … I think Ofsted category makes a massive difference because once you get into category [Inadequate] it's very difficult to get out and once you're in category it's very difficult to appoint staff or to get good staff so our behaviour issues will all come from this, from where the teaching is not as good as it should be … It'll be schools where there are high levels of PP. High levels of SEN as well. Those are the schools that will have more exclusions because it's more challenging. (Teacher 23, SLT, School A)

… it's whether individual schools, whether that meets your threshold and also whether it meets your threshold for … where your school is at that particular point in time as well, because maybe that wouldn't have met their threshold two years ago, but it does now.

… a school might be at a point where things are out of control … and you have to implement something quick. A quick fix to try and get some levels of control … It kind of evolves, doesn't it? When you're in a place where you feel, you know … when Ofsted came [to this school] … they said, they just cannot believe how calm it is when you walk around lessons. So … we're at a stage where we can say ok, in that calmness we're going to talk to you about relationships.

Depends what a school’s trying to develop or address at the time … you know are we taking a hard stance on language and verbal abuse type comments towards staff? … And I guess it comes down to … priorities and then back to the interpretation of the guidance and what meets your threshold and your policies and then ultimately, I guess the work of governors and the headteachers and their vision and what they’re trying to do.

Professional context

In terms of the professional context, school ethos as well as the values, commitments and previous experience of school leaders and their understandings of behaviour, responsibility, and the purpose of exclusion, were seen to inform approaches to school exclusion.

Leadership and school ethos

In contrast to Teacher 23’s (SLT, School A) comment above about what a higher excluding school might look like, Headteacher 3 (School G) explains that it is not necessarily the case that schools in similar locations with comparable student profiles will adopt similar stances towards school exclusion, but rather it depends on the school leadership’s position and ethos:

… look at the levels of exclusion and fixed term exclusion between those two very similar based schools in [Town], they’re poles apart. And why are they poles apart? Leadership I would suggest and different ethos. Absolutely.

… that doesn’t sit very well with me, and I think that schools that just go oh yeah … they’ve had this amount of fixed period exclusions we’re now permanently excluding them is … not ok and that’s how we kind of sit as a school, that actually you should have done something before you’ve got to that point. (Teacher 17, SLT, School C)

… it comes down to what different schools’ expectations are, and what they've seen in the previous year, and … what their focus is and for us, we've got this real focus about … defian[ce], so that our fixed term exclusion numbers are higher on that than they were previously, because that's what we've been focusing on.

While in many ways school level exclusion policies were seen to largely mirror the statutory guidance and were seen as ‘quite prescriptive’ (Teacher 23, SLT, School A), Teacher 23 (SLT, School A) explains that ‘ … it's [the] behaviour policies of schools that would look quite different.’ It is within the behaviour policy that the school’s understanding of and approach to behaviour is outlined and can be based on different approaches, policy influencers and trends, for example, a more behaviourist approach based on the application of rewards and sanctions, or a relational approach based on nurture, restorative practices, and building positive relationships, or a combination of the above (see Deakin and Kupchik Citation2016; Deakin and Kupchik Citation2018). In many ways, not least because ‘a serious breach or persistent breaches of the school’s behaviour policy’ is included in the two-limb test for exclusion (DfE Citation2017, 10), you cannot disentangle the enactment of school exclusion policy from the enactment of a school’s behaviour policy.

Understandings of behaviour and locus of responsibility

The way that behaviour is understood predisposes people to particular responses (Hallett and Hallett Citation2021). In the current study, whether a pupil was seen as being the problem, or having a problem, was seen to be based on moral, philosophical and political perspectives:

And I guess it’s how does one see life? Does one see life as a case of when things don’t work that’s because someone’s needs have not been met? Or do you see [it] as they’re a bad person … they’re just not accepting responsibility. They have to pay for their actions. And the truth is probably somewhere in the middle, isn’t it? … and depending on your philosophical or political outlook, you’re going to fall more or less to one side of that line. (Teacher 5, SLT, School B)

… if you say that something … in which there are choices that you’re unable to affect is failure, that the system is failing, you’re placing responsibility in the wrong place … it’s the child’s or the parent’s or whatever’s failure … to respond in a way, that’s … reasonable. (Headteacher 2, School H)

… my philosophy now on knife crime is knife crime’s a cry for help, so … if we think about it differently, so we don’t think about it as they’re committing a crime, if we think about it as they’re asking for help, we will think about and intervene differently, and we may then not permanently exclude a child who’s got a knife. (Teacher 27, SLT, Alternative Provision B)

At the local level, there had been attempts to recontextualise the national policy through the creation of a framework for practitioners, which encouraged them to adopt a relational understanding of behaviour as communication and think differently about school exclusion and how to prevent it. While this was largely seen as a positive move, some felt that whilst they were being supported to think differently, without investment in additional material resources, they were not going to be able to respond differently.

Linked to the discussion around the situated context, the framing of young people as ‘not mainstream’ (Teacher 24, SLT, School B) also featured in some of the interviews. Invoking this category and logic of deficiency worked to individualise the problem, with the child being seen to need to fit within the constraints of the ‘mainstream,’ rather than the ‘mainstream’ needing to adapt to the child, which in turn was seen to influence what support a school felt they could and should provide.

Relatedly, there were varying opinions on what the role of a teacher is and the extent to which they can and should be working to address wider issues:

Some people will think that everything is their responsibility. Others will think that that's not their responsibility … [t]hat’s social care's job or that's somebody else's job. (Teacher 27, SLT, Alternative Provision B)

As well as understandings of behaviour and the locus of responsibility, decisions to use either fixed period or permanent exclusions were also linked to what the purpose of exclusion was understood to be, and the difference exclusion might make.

Purpose of exclusion

Six different purposes of school exclusion were identified from the interview data. The majority of the respondents talked about the purpose being; 1. to safeguard and protect the school community. Many of the respondents also spoke about exclusion as a way to; 2. send multiple messages – to the pupil and their parent(s), other pupils and their parents, as well as staff – about what will and will not be tolerated in the school and to deter or change behaviour. The focus here was on being seen to maintain authority and the school’s reputation, as well as preparing pupils for ‘the big wide world’ (Teacher 6, SLT, School J). A smaller number of respondents also described the purpose of exclusion as: 3. providing some breathing space for the school and pupil (in the case of fixed period exclusions) which gave schools time to put in additional support; 4. providing a fresh start through moving to a new school following a permanent exclusion, though some interviewees noted that in reality a new school did not always result in a new start with some young people being seen to ‘come with baggage’ (Headteacher 4, School L); and 5. to meet needs, with schools seeing the exclusion process as a way to help pupils access support from different services. Contrastingly, some teachers believed that school exclusion, particularly for persistent disruptive behaviour, simply ‘moves the problem on’ (Teacher 6, SLT, School J) and while exclusion may serve the school’s needs, it may not help to meet the needs of the pupil. The final and least mentioned purpose was 6. to punish. While one interviewee from the AP sector thought that some schools may see exclusion as a punishment, this was reflected in very few of the mainstream (head)teacher interviews. For some interviewees, exclusion was seen as a ‘consequence’ (Teacher 10, SLT, School H) rather than a punishment and linked to both deterrence and restoration.

Having explored the situated and professional contexts that may influence the enactment of school exclusion policy, I will now turn to look at the material and external contexts.

Material context

School budgets and buildings, along with staffing levels and setup, were identified as material factors influencing the enactment of school exclusion policy. Many of the teachers spoke about insufficient funding for supporting pupils with SEND in particular. Teacher 19 (SLT, School E) suggested that for schools with fewer resources:

… to potentially support those really high, vulnerable students, you're going to end up at a decision to permanently exclude quicker because you haven't got endless supplies of resources and provisions to put in place and some schools have more than others.

Moreover, while some schools had access to different types of AP, others due to their geographical location, the age of the pupil, or restricted budgets did not. The cost of AP for some schools was simply too high and they felt they had to prioritise spending in other areas:

We're absolutely … on a shoestring. But you have to prioritise and for us, the priority isn't spending £100 a day at an alternative provision. (Teacher 11, SLT, School F)

External context

Many of the education professionals spoke about the knock-on effects of austerity and sustained underfunding across local services, including social care, the police, and Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, with schools feeling that ‘they’ve had to pick up the pieces where wider society … has shrunk’ (Teacher 26, SLT, Alternative Provision A). Participants spoke about struggling to support pupils with their mental health due to long waiting lists and a lack of outreach workers. Others spoke of ‘social services … closing cases too early or trying to close cases, which they may have previously kept open, just because they're stretched and they are having to prioritise’ (Teacher 5, SLT, School B), and having to ‘hit very high threshold[s]’ (Teacher 4, SLT, School O) in order to access support. Funding cuts had resulted in reduced capacity, with the closure of early help services such as Sure Start Children’s Centres, and the changing role of the LA against a backdrop of academisation had led to cuts to LA support teams, including behaviour support services, and changing relationships and communication between schools and the LA Exclusions Team. Some services, for example Educational Psychology, had also been privatised and become traded meaning schools had to be strategic about when they were going to buy in support. Changes to commissioning models and a shortage of AP and special school places in the LA were also identified as placing pressure on mainstream schools, with teachers describing how supply was unable to keep up with demand (as discussed in the situated context section).

External pressures and expectations from the broader policy context were other aspects of the external context that were seen to influence the enactment of school exclusion policy and lead at times to policy contradictions, perverse incentives, unintended consequences and trade-offs.

Contradictions, perverse incentives, unintended consequences and trade-offs

In the you have to see shades of grey section, I discussed how responsibilities set out in other national and school policies, including SEND and safeguarding policies, informed the enactment of school exclusion policy. However, some teachers felt that these policies were ‘not closely coordinated’ (Teacher 21, SLT, School N) and were sometimes contradictory:

So sometimes the exclusion policy I guess contradicts your safeguarding that's around keeping these children safe. (Teacher 23, SLT, School A)

… you can have one individual for whom your decision is going to potentially wreck their education, but the alternative is to have X number of hundreds of students who are being affected daily in a much smaller way, which is really hard to measure … and then there is the massive intangible of the fact that if your school has a reputation for poor behaviour … that is the single biggest deciding factor in terms of parents choosing schools.

In similarity to Power and Taylor’s (Citation2021) findings from their paper on school exclusions in Wales, attainment, attendance and exclusion targets were all mentioned as having unforeseen effects. Local targets to reduce school exclusion for example were seen to influence practice and the adoption of creative solutions and alternatives to exclusion, such as the use of internal exclusion and being asked to rescind permanent exclusions and instead negotiate managed moves through the IYFAP. While seen as positive alternatives by many as they helped to keep an exclusion off the school’s and pupil’s record, some noted how these practices could themselves have unintended consequences (see also Power and Taylor Citation2020). For example, Teacher 18 (School B) believed, from his experience, that having a permanent exclusion on a child’s record could move them ‘up the ladder … to be able to access specialist provision’ whereas with a managed move ‘they wouldn't flag up high enough needs to warrant a specialist place’.

Others felt that while they may want to try alternatives or put in place bespoke packages for pupils, there were a number of trade-offs that they had to navigate. For example, the benefits of sending a pupil to a part-time AP placement or vocational college course were weighed against the cost of the provision and the knock-on effect that entering the pupil for fewer qualifications would have on the school’s attainment figures.

Some respondents also felt pressure not to use certain alternative measures, for example, reduced timetables. Discussing the LA’s focus on reducing the use of reduced timetables, Teacher 21 (SLT, School N) suggested that:

… [there needs to be a less] judgmental, critical approach and more of an understanding … of … the complexities that we're dealing with day-to-day and just understanding that schools are working hard to address some of the needs that students have. And it's not always clear cut. It absolutely is not black and white.

Grey exclusions: best interests of the school and/or best interests of the child?

As described at the start of this paper, the decision to permanently exclude can only be made on disciplinary grounds. Therefore, it would be unlawful for schools to permanently exclude for non-disciplinary reasons such as a pupil ‘having additional needs or a disability that the school feels it is unable to meet’ (DfE Citation2017, 9). Yet, in line with Ferguson and Webber’s (Citation2015) earlier work, and linked back to the fifth understanding of the purpose of exclusion outlined in this paper, Headteacher 5 (School B) explained how formal positions may at times be disregarded when it is seen to be in the best interests of the child:

Interviewer

… So, would the decision to permanently exclude ever be because you can’t meet need?

Headteacher 5

It shouldn’t be, but yes. If … as in a cry for help? … Absolutely. You know, once we’ve exhausted absolutely every avenue that we think we can … explore, then that child is still being failed by us, but also by the system, and often the only way to get that child into a specialist provision is to permanently exclude them … And, you know, headteachers, colleagues, they would all agree with that, I think. They may not publicly acknowledge it – they certainly wouldn’t publicly acknowledge it, but …

Conclusion

This paper has explored the enactment of national school exclusion policy at the local level in one LA in England. While it was felt that the statutory guidance was in many ways procedurally clear, doing school exclusion policy was not seen to be black and white. The interview data revealed how schools negotiated complex considerations and contextual factors when enacting school exclusion policy and in making decisions to exclude. The need to ‘take context seriously’ (Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012, 19) appeared to have a double application when it came to the enactment of school exclusion policy, with a number of interviewees talking about the need to see shades of grey and consider individual circumstances and wider contexts when deciding on exclusion, as well as describing how different contextual factors weave together in complex assemblages to inform a school’s approach to school exclusion or in other words where they sit. ‘[I]nformal, less visible and undocumented policy practices’ were also seen to sit alongside ‘official enactments’ (Maguire, Braun, and Ball Citation2015, 487) with schools being seen to disregard or circumvent particular formal positions due to perverse incentives and prioritising the best interests of the school, but also in some circumstances under the (mis)perception that doing so was in the best interests of the child. While the findings are based on interviews with education professionals working in only one LA in England, the themes discussed highlight important factors to be explored further in larger scale studies. Multiple case studies could also be conducted to map how different contextual factors weave together to influence formal and informal exclusion rates in different schools (types and stages) over time. With new statutory guidance (DfE Citation2022) having recently been issued, which includes new roles for social workers and virtual school heads to provide advice on whether the welfare, safeguarding needs and risks of pupils who either have a social worker or who are looked-after were considered prior to exclusion, and guidance on the use of different preventative measures, it will be interesting to explore in future research the extent to which these national changes mediate practice and influence the enactment of school exclusion policy at the local level.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all of the participants who took part in this study, and to the reviewers for their helpful feedback on this paper. Thank you also to my DPhil supervisors, Professor Harry Daniels and Professor Rachel Condry. This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council grant ES/J500112/1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alice Tawell

Alice Tawell is a DPhil Candidate at the Department of Education, University of Oxford. Her research, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), focuses on the enactment of school exclusion policy in England. She is co-supervised by Professor Harry Daniels at the Department of Education and Professor Rachel Condry at the Centre for Criminology. Alice is also Co-Investigator on the four-year ESRC funded Excluded Lives project: The Political Economies of School Exclusion and their Consequences.

Notes

1 In 2019, fixed period exclusions were renamed suspensions by the DfE (see DfE Citation2019). However, as fixed period remains the term used in legislation (see Education Act Citation2002), and reflects the term used when I began my fieldwork, I have chosen to refer to fixed period exclusions throughout this paper.

2 Updated statutory guidance was published by the DfE in September 2022. While the two-limb test remains the same, ‘such as staff or pupils’ has been added after ‘others’ in the second limb (see DfE Citation2022, 13).

3 There has been a slight change to the terminology used in the 2022 guidance (see DfE Citation2022).

4 ‘Off-rolling is the practice of removing a pupil from the school roll without using a permanent exclusion, when the removal is primarily in the best interests of the school, rather than the best interests of the pupil’ (Owen Citation2019).

5 Data collection moved online while Covid-19 restrictions were in place.

6 ‘Every local area is required to have a Fair Access Protocol in place which ensures that access to education is secured quickly for children who find themselves without a place outside the normal admissions round’ including young people who have been permanently excluded (Child Law Advice Citation2022).

7 Following concerns raised around the ‘other’ category lacking clarity, it was removed as a reason code in 2020 (The Centre for Social Justice Citation2018; Timpson Citation2019).

8 The EBacc is an accountability measure in England (see Cultural Learning Alliance Citation2022).

References

- Ainscow, M., T. Booth, and A. Dyson. 2006. “Inclusion and the Standards Agenda: Negotiating Policy Pressures in England.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 10 (4-5): 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110500430633.

- Ball, S., K. Hoskins, M. Maguire, and A. Braun. 2011. “Disciplinary Texts: A Policy Analysis of National and Local Behaviour Policies.” Critical Studies in Education 52 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2011.536509.

- Ball, S. J., M. Maguire, and A. Braun. 2012. How Schools do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary School. London: Routledge.

- Braun, A., S. J. Ball, M. Maguire, and K. Hoskins. 2011. “Taking Context Seriously: Towards Explaining Policy Enactments in the Secondary School.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32 (4): 585–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2011.601555.

- The Centre for Social Justice. 2018. Providing the Alternative: How to Transform School Exclusion and the Support That Exists Beyond. London: The Centre for Social Justice.

- Child Law Advice. 2022. “Fair Access Protocol”. Child Law Advice. Accessed November 10 2022. https://childlawadvice.org.uk/information-pages/fair-access-protocol/.

- Children’s Commissioner. 2013. Always Someone Else’s Problem”: Office of the Children’s Commissioner’s Report on Illegal Exclusions. London: Children’s Commissioner for England.

- Cole, M. 1996. Cultural Psychology: A Once and Future Discipline. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cultural Learning Alliance. 2022. “What is the EBacc?” Cultural Learning Alliance. Accessed November 10 2022. https://www.culturallearningalliance.org.uk/briefings/what-is-the-ebacc/.

- Daniels, H., I. Thompson, and A. Tawell. 2019. “After Warnock: The Effects of Perverse Incentives in Policies in England for Students with Special Educational Needs.” Frontiers in Education, https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00036.

- Deakin, J., and A. Kupchik. 2016. “Tough Choices: School Behaviour Management and Institutional Context.” Youth Justice 16 (3): 280–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225416665610.

- Deakin, J., and A. Kupchik. 2018. “Managing Behaviour: From Exclusion to Restorative Practices.” In In The Palgrave International Handbook of School Discipline, Surveillance, and Social Control, edited by J. Deakin, E. Taylor, and A. Kupchik, 511–527. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Department for Education. 2017. Exclusion from Maintained Schools, Academies and Pupil Referral Units in England: Statutory Guidance for Those with Legal Responsibilities in Relation to Exclusion. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education. 2019. The Timpson Review of School Exclusion: Government Response. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education. 2022. Suspension and Permanent Exclusion from Maintained Schools, Academies and Pupil Referral Units in England, Including Pupil Movement: Guidance for Maintained Schools, Academies, and Pupil Referral Units in England. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education and Department of Health. 2015. Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0 to 25 Years: Statutory Guidance for Organisations Which Work with and Support Children and Young People who Have Special Educational Needs or Disabilities. London: Department for Education.

- Done, E. J., H. Knowler, and D. Armstrong. 2021. “‘Grey’ Exclusions Matter: Mapping Illegal Exclusionary Practices and the Implications for Children with Disabilities in England and Australia.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 21: 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12539.

- Education Act. 2002. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2002/32/contents.

- Equality Act. 2010. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents.

- Ferguson, L. 2019. “Children at Risk of School Dropout.” In Oxford Handbook of Children and the Law, edited by J. G. Dwyer, 635–664. Oxon: Oxford University Press.

- Ferguson, L., and N. Webber. 2015. School Exclusion and the law: A Literature Review and Scoping Survey of Practice. Oxford: Department of Education.

- Gazeley, L. 2020. “Exclusions, Barriers to Admission and Quality of Mainstream Provision for Children and Young People with SEND: What Can Be Done?” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 20 (2): 172–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12487.

- Hallett, F., and G. Hallett. 2021. “Disciplinary Exclusion: Wicked Problems in Wicked Settings.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 21 (1): 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12541.

- Kulz, C. 2015. Mapping the Exclusion Process: Inequality, Justice and the Business of Education. London: Communities Empowerment Network.

- Kvale, S. 1996. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Maguire, M., A. Braun, and S. Ball. 2015. “‘Where you Stand Depends on Where you Sit’: The Social Construction of Policy Enactments in the (English) Secondary School.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 36 (4): 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2014.977022.

- Owen, D. 2019. “What is off-Rolling, and how Does Ofsted Look at it on Inspection?” GOV.UK, May 10. Accessed November 10 2022. https://educationinspection.blog.gov.uk/2019/05/10/what-is-off-rolling-and-how-does-ofsted-look-at-it-on-inspection/.

- Partridge, L., F. Landreth Strong, E. Lobley, and D. Mason. 2020. Pinball Kids: Preventing School Exclusions. London: RSA.

- Power, S., and C. Taylor. 2020. “Not in the Classroom, but Still on the Register: Hidden Forms of School Exclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (8): 867–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1492644.

- Power, S., and C. Taylor. 2021. “School Exclusions in Wales: Policy Discourse and Policy Enactment.” Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 26 (1): 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2021.1898761.

- Saldaña, J. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Singh, P., S. Thomas, and J. Harris. 2013. “Recontextualising Policy Discourses: A Bernsteinian Perspective on Policy Interpretation, Translation, Enactment.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (4): 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.770554.

- Slee, R. 2015. “Beyond a Psychology of Student Behaviour.” Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 20 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2014.947100.

- Srivastava, P., and N. Hopwood. 2009. “A Practical Iterative Framework for Qualitative Data Analysis.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8 (1): 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800107.

- Stanforth, A., and J. Rose. 2020. “‘You Kind of Don’t Want Them in the Room’: Tensions in the Discourse of Inclusion and Exclusion for Students Displaying Challenging Behaviour in an English Secondary School.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (12): 1253–1267. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1516821.

- Timpson, E. 2019. Timpson Review of School Exclusion. London: Department for Education.

- Whitaker, D. 2021. The Kindness Principle: Making Relational Behaviour Management Work in Schools. Carmarthen: Independent Thinking Press.

- Ydesen, C. 2016. “Crafting the English Welfare State-Interventions by Birmingham Local Education Authorities, 1948-1963.” British Educational Research Journal 42: 614–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3223.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.