?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Several studies have examined the positive impact of inclusive, heterogeneous learning environments and parental involvement on student achievement. However, for children with special educational needs, exclusionary processes due to labelling and insufficient support for parental involvement often remain unresolved. Considering this, our research seeks to present the perspective of teachers on the involvement of parents raising children with special educational needs. To explore this, we conducted semi-structured, in-person interviews with practicing teachers who have extensive experience in teaching children with special education needs (SEN), as well as maintaining contact with their students’ parents. Data collection was carried out within the framework of the MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group. The 21 interviews were subjected to text analysis applying constructivist grounded theory (CGT). Our main results show that family involvement is influenced by individual, organisational, and social factors, with teachers’ integration approach playing a crucial role. Our results could be useful in deepening the understanding of the relationship between schools and parents of children with special educational needs and in preparing and supporting teachers accordingly.

Sustainable Development Goals:

Introduction

The paradox of inclusion describes that special educational needs (SEN) and individual abilities and skills may lead to special treatment in education, often resulting in exclusion (no label, no resources) (Biklen Citation2010). Labelling in education sets off a two-way discourse: on the one hand, it is a bureaucratic, retrograde remnant; on the other hand, support and resources would be inaccessible without it, as the pedagogical diagnosis enables families and professionals involved in education to access additional services and benefits through intervention programmes (Anderson and Boyle Citation2015; Green et al. Citation2005; Haslam, Rothschild, and Ernst Citation2002). Pedagogical diagnosis is a systematic way of examining and identifying children's specific educational needs, capabilities, strengths, and challenges. This approach entails collecting and analysing extensive data on a student's cognitive, academic, social, emotional, and behavioural functioning in order to guide instructional and support measures. Pedagogical diagnosis seeks to identify the particular features that may influence a student's learning and development, aiding educators in developing personalised educational interventions and accommodations to improve their learning results and general well-being. At the same time, the labelling process is influenced by current education policy and social and ideological trends, which, in turn, shape professional guidelines, diagnoses, and educational practices in relation to SEN (Arishi, Boyle, and Lauchlan Citation2017).

In Hungary, between 2010 and 2020, the number of students with SEN (Special Educational Needs) in primary education increased from 6.7% to 7.7%. Concurrently, in a secondary education setting, this rose from 3.9% to 6.2%, displaying a significant increase. This is partly due to greater awareness of developmental disorders in the media and education, resulting in both parents and teachers becoming increasingly aware and noticing the signs earlier. Accordingly, there has been an improvement in diagnostics, resulting in more timely and accurate diagnoses for children. In Hungary, 72% of SEN students can be educated together with other students based on assessment and diagnostic criteria, meaning that they receive integrated education at school (Varga Citation2022). The steeply rising incidence of SEN and the associated integration pose a major challenge for schools and the families where the children are raised. In this respect, the Hungarian education system is not unique. Although the definition of SEN varies from country to country, all education systems are characterised by an increasing number of students with the SEN label, often presenting the challenge of inclusion for schools (Brussino Citation2020). The intersectionality between SEN and other dimensions of diversity is a major challenge for educational institutions. One such dimension is socio-economic status. The literature suggests that the inclusion of disadvantaged SEN students is beset by several difficulties, such as the recognition of SEN, cultural biases, or learning, emotional, and behavioural difficulties due to social background (Brussino Citation2020; Kvande, Belsky, and Wichstrøm Citation2018). Research shows that children from different social backgrounds are overrepresented in different SEN categories, which has implications for their inclusive education. Findings by Kvande, Belsky, and Wichstrøm (Citation2018) show that disadvantaged students are less likely to be diagnosed with learning disabilities and more likely to be segregated in education, a trend that is observed worldwide. The aim of this study is to examine the social network that develops around a child with special educational needs, with a specific focus on the teachers’ presence and their relationship with the parents. Therefore, in our qualitative analysis, we approached the topic from the perspective of teachers. We processed and conducted text analysis on material from 21 interviews with teachers who instruct SEN students in an inclusive way. The questions concentrated on teachers’ relationship with parents, which is the focus of our research. Grounded theory provides the theoretical foundation for our research; we interviewed teachers about parent-school relationships through semi-structured interviews. The analysis of the interviews highlighted the problematic areas emphasised by teachers.

In the first part of this study, we review existing literature about the conditions of an inclusive education system, since our interviews revealed that teachers face the greatest challenges when these conditions are not being fully met. Next, we outline the theoretical framework of the study, namely the contextual systems model (CSM). After a detailed description of the research methodology, the results are presented. The codes employed in the study are grouped according to five topics. In the discussion, we compare the data with the theoretical framework and make recommendations based on our results.

Conditions for inclusion

In Hungary, segregated education emerged when SEN students were first involved in compulsory public education in 1993 (Perlusz Citation2010). Since then, education policy has attempted to reverse the process of segregation, which can be traced back even earlier than at school. The socio-cultural and infrastructural disparities between regions and settlements are so vast that segregation is almost inevitable in the schools of certain settlements. In almost all countries, a legal framework for inclusion has been created, with a great variety in the number of dedicated resources. Generally, the education system needs to support a much more heterogeneous mix of students than two decades ago, meaning that a significant number of teachers are facing novel challenges within the school environment. This is something older teachers (who completed their education prior to this demographic shift) were not trained for and younger teachers often only encounter this issue at a theoretical level, while short, continuing training courses may not provide sufficient preparation (Horvat, Weininger, and Lareau Citation2003). The issue is complex due to the number of students in integrated education being high, so teachers may encounter students with various challenges in the classroom; class might have students with sensory impairment as well as children with learning disabilities. There is considerable variation between countries in the proportion of children who are taught outside mainstream education. According to 2022 data by the European Agency, this proportion varies between 0.1 and 7 percent. This may be due to differences in the definition of SEN, but other significant differences across countries are likely (Brussino Citation2020; Lénárt, Lecheval, and Watkins Citation2022). In Hungary, for example, the proportion of SEN students in inclusive education at ISCED levels 1–2 ranges between 3–10.5 percent, while the proportion of students in special education ranges between 1–3.5 percent (Varga Citation2022). The effectiveness of education is proportional to teachers’ experience in schools in heterogeneous or segregated settlements (Szumski, Smogorzewska, and Karwowski Citation2017). The presence of SEN students often cause challenges in the classroom. When the number of SEN students within a group is above average, it may hinder effective teaching and worsen (who’s?) performance (Rouse and Florian Citation2006). When examining this problem, the proportion of SEN students and the class size are often not taken into account, despite their significant impact on teachers’ and parents’ experiences with inclusion (Elkins et al., Citation2003; Gaad and Khan Citation2007; Szumski, Smogorzewska, and Karwowski Citation2017).

Several studies suggest that teachers are not adequately trained to teach SEN children. Teacher education prepares for transferring knowledge to students without SEN (Koutsoklenis and Papadimitriou Citation2021). Teachers whose training is inadequate to teach students with diverse backgrounds, abilities, and knowledge often attribute educational failures to reasons outside the classroom (e.g. blaming parents) (Silva and Morgado Citation2004). The drive for inclusion in schools implies that regular teachers increasingly need to be able to educate SEN and BESD (behavioural, emotional and social difficulties) students, with the additional responsibility of nurturing children’s mental health (Rothì, Leavey, and Best Citation2008). This phenomenon could easily create tensions for teachers because the obligation to support students with difficulties in inclusive education could be accompanied by the frequent feeling of being ill-equipped for this role. Hattie’s (Citation2008) synthesis of 800 meta-analyses concludes that a varied methodology is essential when there is a SEN student in the classroom (for example, a neurodivergent student), resulting in an increased achievement of up to 30% for the class as a whole.

Inclusive education has a positive impact that is far reaching, having implications beyond only SEN students. There is scientific evidence that all students are affected by teachers’ attitudes towards SEN students. Jordan’s (Citation2018) longitudinal (20 + years) research, conducted in inclusive classrooms, reveals that teacher attitudes are crucial concerning effective inclusive teaching. The most striking finding from the study is that teachers who considered it their responsibility to integrate SEN students were more effective in teaching both SEN and non-SEN students (Jordan Citation2018).

What support do teachers need? Reflexive inclusion views the practice of inclusive education as a cross-disciplinary task involving educational science, pedagogy, special education, and specialised methodology (Budde and Hummrich Citation2015). Research by Müller and Hoffmann (Citation2019) points out that inclusive schools require interprofessional collaboration between teams in the school and with partners outside the school. The benefits of collaboration are apparent from both practical examples and the literature. It is easier for teachers to focus on their primary role of teaching when they are assisted by professionals specifically responsible for overseeing the well-being of a SEN student(s), as they have the assurance that their students are looked after by well-trained professionals. This approach can reduce teacher burnout and significantly improve the quality of inclusive education (Rothì, Leavey, and Best Citation2008).

School management is decisive in terms of the degree of inclusion at an institution. School management can influence the atmosphere in the school and provide the conditions to support teachers in their work (López-López, Romero-López, and Hinojosa-Pareja Citation2022). At the same time, inclusion poses a major challenge to school management, as they also may need to face the problem of parents withdrawing their children from the school as the number of inclusively educated students increases (Poon-Mcbrayer Citation2017).

The parent-teacher relationship

In Hungary, parental involvement is also an important pillar in narrowing the achievement gap, which is especially prevalent among disadvantaged students. The positive effect is particularly strong if the relationship between parents and schools is supported by factors such as religiosity, which, even after controlling for other variables, has a significant positive effect on parental actions and their perceived effectiveness (Pusztai and Fényes Citation2022). However, for SEN children, findings show that schools are not able to support parental involvement adequately. Examining the issue from the perspective of parents suggests that more extensive communication with parents of SEN children, as compared to other parents, does not fully translate into better student achievement (Hrabéczy et al. Citation2023).

Family-school collaboration may be impeded by the hierarchical division of the relationship between the two parties, as well as the one-dimensionality of the educational work performed by each in cases when teachers and parents act separately and independently, forming a division between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ (Braley Citation2012; Taylor, Smiley, and Richards Citation2015). The process of cooperation in education can be constructed by reinterpreting relational factors, roles, and responsibilities (Carlisle, Stanley, and Kemple Citation2005; Epstein Citation2010; Epstein Citation2018). Several studies highlight the importance of school-family collaboration, the relevance of constant dialogue, joint efforts and information sharing, and effective and meaningful collaborative practices (Christenson and Sheridan Citation2003; Crouter et al. Citation2004; Welch Citation1998). A foundation for teacher-parent relationships is an environment of trust directed toward mutual support and understanding (Unger et al. Citation2001).

To establish a good partnership, teachers must acknowledge the work performed by parents, recognising that parents of SEN children have greater responsibilities at home as their children require more assistance. However, teachers can also rely on parents of SEN children, as by the time the child starts school, parents have become experts on their child’s needs and can provide valuable insight and support (Blackman and Mahon Citation2016; Jigyel et al. Citation2020; Karisa, McKenzie, and De Villiers Citation2021). Although they are committed to their child’s care and education, the level of parental involvement at school may vary greatly due to characteristics of the parents themselves, such as having special needs or not speaking the official language of the country.

Typically, teachers are eager to involve parents of SEN students, build on shared experiences, and establish common goals. However, they may find that parents are not as involved as expected. This could be because parents of SEN students have already had negative experiences and are more likely to be disengaged (Balli, Citation2016). Research findings suggest that parents of SEN children need increased support, acceptance, and encouraging communication to become involved, especially if they face social or language-related barriers (Wilt and Morningstar Citation2018). Involving parents is instrumental as it positively influences students’ motivation and, consequently, their achievement (Bariroh Citation2018). Klicpera and Gasteiger Klicpera (Citation2004) showed that parents whose child was enrolled in an inclusive institution were more likely to report being overburdened. At the same time, these parents were disproportionately positive about their child’s social skills development, accompanied by increased satisfaction with their choice of institution (Klicpera and Gasteiger Klicpera Citation2004). However, it is often a problem that parents must help an integrated student at home because he or she does not receive enough support at school (Heimdahl Mattson, Fischbein, and Roll-Pettersson Citation2010).

Theoretical framework

The contextual systems model (CSM) classifies the relationship between school and family and the role of parental involvement into a specific model (Pianta and Walsh Citation2014). The ecological approach enables the construction of the examined data with respect to horizontal structural factors. The present analysis includes both individual perspectives from the interviews as well as multidimensional levels. Our research questions are formulated based on everyday educational practice. However, we also aim to gain further insight into the various perspectives on parental involvement, ranging from the narrow school context and different teacher roles to the wider institutional context, towards systemic problems and solutions (micro-, meso-, and exo-systems). To understand the various levels of parental involvement in different contexts, we examined the relevant social and ecological factors as well as the socio-cultural contexts in which separations occur. We also examined the individual, organisational, and social determinants of inclusion and highlighted both the challenges and possible solutions. This approach is necessary to support the inclusion of families with SEN children as partners. The factors of CSM interact at all levels. Student, family, school, and socio-cultural contexts constitute the four basic elements of the system, which jointly define relational factors. The child–parent relationship is the central focus when examining the structure of the system, with the family-school relationship built around it. The school and family environments are not separate, but depend on and interact with each other. The family-school relationship is a crucial element of the CSM model, operating as an open system with continuous feedback and feedforward loops ().

Table 1. Contextual Systems Model (Pianta and Walsh Citation2014).

Methodology and data collection

The research project underlying this study was conducted by the MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group in September – October 2022 The focus was on (1) the teachers’ personal life path, (2) views on parenting, (3) school-parent relationship, (4) patterns and fault lines of relationships (at teacher level), (5) issues related to parents of SEN students, (6) good practices (school level), (7) composition of knowledge on parent-teacher contact, and (8) impact.

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, which were audio-taped and transcribed. The interviews were conducted in the eastern region of Hungary, which has a lower economic development level than the national average. The proportion of SEN students is significantly higher than the national average in primary and secondary vocational schools located in underdeveloped, small settlements of this region. The interviews for this study were conducted with teachers from primary and secondary schools located in various settlements representing different social backgrounds. 21 interviews were subjected to in-depth text analysis.

Our main research question asked about teachers’ relationship with parents of students with special educational needs. The research questions that guided the study were the following:

What challenges do teachers face while teaching in inclusive classrooms?

From a teacher’s perspective, what role does parental involvement play in raising children with special educational needs?

How does a social network develop around a child with special educational needs?

Research participants

The research participants were primary and secondary school teachers. The characteristics of the interviewees and their schools are presented in .

Table 2. Interviewees and their schools.a

Our study was guided by a primary criterion focused on the analysis of text, following the principle of non-interventional studies (Babbie Citation1986; Sántha Citation2015c). Specifically, in the content analysis of the interviews, our goal was to identify the number of words and specific codes used. To achieve this, we opted for a structuralist approach, while interpretive analysis was only used to identify concepts and theory-based categories. This involved grouping the raw data obtained from the text corpus into predefined categories based on existing theories from the literature, using deductive logic.

Data were quantified and collated using Microsoft Excel, while the interviews were coded and analyzed using Atlas.ti 22.2.5 Student version software. Authors BAD, TSZ, and RSÁ conducted the thematic analysis, following the qualitative methodology of Sántha’s (Citation2009; Citation2011; Citation2015a) recommendations. The stages of coding were divided into 5 phases following the constructivist (CGT) line of the grounded theory (GT) (Charmaz Citation2017; Sebastian Citation2019). In phases 1 and 2, authors BAD, TSZ, and RSA familiarised themselves with the interview texts and performed semantic open coding. In phase 3, considering the samples of codes, author BAD classified codes into categories (Vaismoradi et al. Citation2016). In creating the categories, the researchers analyzed the concepts which emerged during coding by continuously comparing and filtering the raw data, following a selective coding process based on the similarity and dissimilarity of the codes (Bryant and Charmaz Citation2012; Harper and Thompson Citation2011). In phases 4 and 5, the analysis cycles were repeated to revise and refine how codes were classified into categories. To ensure the reliability and validity of the coding process, personal triangulation, including the inter-coder technique, was used. Authors AH, GR, and DK repeated steps 1, 2 and 3, then reviewed the results, examining the validity of the codes and the answers to the research questions. After that, AH calculated the reliability score of the coding with the formula of the intra – and inter-coder method explained below. Following multifaceted and reflective consideration, the analysis focused on the relevant factors of inclusive education processes, using the ‘triangulation typologies’ of qualitative analysis (Sántha Citation2015b).

To ensure the internal reliability of our research, we focused on the reliability of the coding process, which in turn contributes to the overall reliability of the analysis (Sántha Citation2012). As previously mentioned, we followed the grounded theory (GT) principle of open, axial, and selective coding by generating a priori and in-vivo codes. To assess the reliability of the coding process, we adapted the intra – and inter-coder reliability metrics in line with the GT methodology (Dafinoiu and Lungu Citation2003). Personal triangulation, including the inter-coder technique, was employed to ensure the reliability of the coding process. Specifically, the coding was performed twice by each one, independently, by RG and KD. HA compared the results produced in the two coding rounds and calculated the reliability index. In the first round of coding for the 21 interviews, a total of i = 604 codes were generated, while in the second round, j = 442 codes were produced. Of these, n = 364 coding decisions were identical in both rounds. We used the formula of the intra – and inter-coder method to perform the reliability calculation, as shown below:

There is no uniform methodological standard for the threshold of acceptability for the km value but, based on Sántha (Citation2012), it is considered adequate above 0.6. In light of this, the value km = 0.696, which indicates the reliability of our coding, is within the acceptable range.

Our analysis of the interviews can contribute significantly to the existing literature on inclusive education, particularly in the Hungarian context. We shed light on educational practices related to special treatment by seeking answers to specific questions within this context ().

Table 3. Main topics, quantified data on their associated sub-topics, with code frequencies and percentages, and relevant interview excerpts.

Results

The relationship between teacher characteristics and codes was examined using Atlas.ti 23. We compared the number of codes mentioned in each category.

From our 21 participants, two identified as male. Their opinions do not differ from those of female teachers. However, there is a significant difference between the length of the interviews and the number of codes discussed. The codes represent themes that were characteristically salient to our topic and were produced during the inductive coding process. The average number of codes mentioned in an interview is 30.9. However, in comparison, the number of codes mentioned by the two male interviewers is only 16 and 8, the two lowest among the interviews.

In Hungary, teacher education and school degrees are mostly associated, as teachers at ISCED 1–2 level have BA degrees, while teachers at ISCED 3 level have MA degrees, typically, including our interviewees. Among our interviewees, 16 were primary school teachers, and five were secondary school teachers. School type was a significant determinant of differences in mental health problems (of the teacher?), e.g. anorexia, depression, and autoaggression. In 10 of the 21 interviews, these problems are mentioned by elementary school teachers and half by secondary school teachers. Talent management also appears proportionally more frequently in almost all interviews with secondary school teachers (6 out of 13 mentions). However, some code gaps are also evident. The codes ‘inclusive approach’ and ‘superficial contact’ are not spoken at all by teachers, but codes describing contact characteristics are equally proportionally less frequent.

Looking at professional experience, we found no significant difference between senior and experienced teachers. Two early career (P5 and P14) teachers, both of whom teach in low Socioeconomic status (SES) schools, were interviewed. In both cases, problem-related codes are more frequently mentioned than other codes. Fear was also explicit in the case of P14, who reported physical aggression from parents. This suggests that difficulties were more pronounced in the experiences of novice teachers, as discussed during interviews.

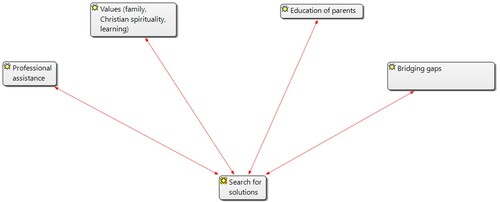

School size and school location had no direct effect on the different codes. However, the school's social background influenced the factors mentioned in the interviews more than any other factor. In absolute terms, difficulties, problems, strained relations with parents, and parental disinterest were more prevalent in low SES schools than in average or high SES schools. For example, 85 of the mentions of systemic problems (127 in total) occurred in low SES schools. Thus, 67% of the mentions of systemic problems were mentioned by our interviewees teaching in low SES schools, who represent 47% of the subjects. In contrast, only 39% of the codes classified in the code family ‘search for solutions’ are associated with the same group of teachers.

Based on several sub-topics and considering the coding patterns of the text corpus, five main topics were highlighted. The topics and sub-topics are presented in .

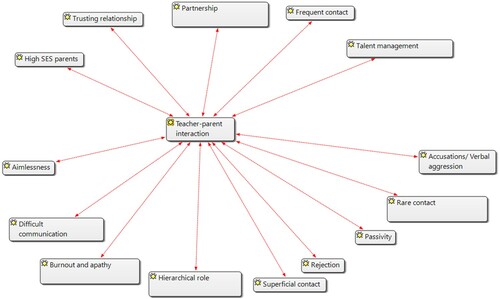

The first main topic features the most critical elements since teacher-parent interaction patterns are analyzed from both negative and positive perspectives (). This is the most varied topic, with 14 sub-topics associated. By observing the distribution of sub-topics, we can identify the two opposite poles of the first main topic. The negative elements include aimlessness, difficulties in communication, superficial and infrequent contact, rejection, and passivity:

I don’t really know the children’s parents. Although … I’ve had one parent stop me before, but then I asked him to tell me who the child that, … , belonged to him was. So I don’t really have any contact with them, that is, personal contact. P2 2:8

Unfortunately, we cannot count on them in this aspect, at least not on most of them. P5 5:12

When a teacher comes into the schoolyard, or a parent starts yelling at the teacher because the child is telling a lie. We have had examples of that. P2 2:30

But … if the child gets caught up in some scheme or gets hurt, we get told that we’re the teachers and should pay attention. P14 14:3

Aimlessness typically becomes problematic from the educational attitude towards the child’s future, which highlights the risk of burnout and meaningless educational goals, as well as early school leaving:

Nothing, it absolutely does not interest [the student]. Most of it is ignored. No, he doesn’t care. So it’s a pain for the parent to come to school. But that’s because they don’t care about their own child, they don’t educate him, obviously if they come to school, the teacher can’t say anything nice or good about their child, but only negative things or potential problems, and they don’t want to hear that, close their ears, so they won’t come in, don’t care. So … they won’t face any … inconvenience. Well, how unpleasant for him to have his child spoken ill of; he’d rather not hear it. P2 2:44

There is still extensive evidence of hierarchical teacher-parent roles, both in everyday interactions and in the systemic and bureaucratic structure of the school:

Well, that’s not good. The teachers there are, erm, erm, extremely divided, erm, I think the atmosphere is not really, not really, erm, good, there’s a lot of cliquishness even among the few people who are there, so erm, the people who go there, well, they have a very difficult time in that respect, but as I only go there for one day, I think it’s, erm, entirely bearable. … P2 2:3

not everyone dares to contact me P16 16:12

The other pole includes a series of positive texts, which provide a reason for optimism as regards the aims of education and positive collaboration processes. Positive factors include trust, partnership, frequent contact, and talent management:

He … well, what needs to be improved … Maybe that, erm … , those parents who are, erm, how shall I put it, less active or less adaptable, to involve them more in school life. So those parents should also come to an open day, to a particular event, to, erm … , church services. Because somehow it’s always the case that they somehow don’t, don’t always participate. Maybe here we could reach out to them to get them a little bit more involved in school life somehow. Obviously, this would be most important for their children. P1 1:35

Parents who want to pay attention to their child, and I see them as a partner, that we want the same thing, then I’ll let them know and inform them if there’s any little tiny problem. P8 8:17

Although there are perhaps fewer people here with higher education, nevertheless, erm, even after three months, I still find that they are cooperative, so they come to the parent-teacher conference. Erm, they respond to everything I write to a particular parents’ group. They are supportive. P1 1:8 ()

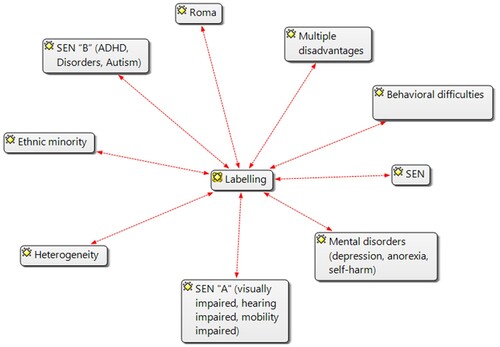

One of the defining issues of inclusive education is diagnostic classification. The degree and extent of this classification determine whether the child can receive optimal developmental support and assistance in accordance with personalised educational goals. In this context, labels support inclusive education processes. The interviews show that, to date, teachers have a vague understanding of the concept of SEN and often use confused terminology to describe educational diagnoses:

It is a difficult and very sensitive area. P10 10:19

The father loved the child very much, but the little girl had problems because she was hyperactive, so the father took her to developmental programs. Nevertheless, the girl had many problems in first grade; she had a hard time fitting in, walking around and dancing in class, and things like that … P11 11:12

… dys-, dys-, dyslexia, dysgraphia, whatever … P17 17:8

… there is this little boy with SEN; the problem is that when there are problems, the boy becomes a bit aggressive … P14 14:25

Further, the interviews reveal the desperation of the teachers, who, in many cases, fall short of understanding the heterogeneity of their students, as they have not been taught how to address it. Basic teacher training does not equip teachers with the appropriate range of understanding and skills needed to care for and educate children with SEN:

It is frightening how at a parent-teacher conference, various medical diagnoses land on the table, and lactose and gluten intolerances, they are nothing special nowadays, so it’s absolutely evident that the poor food server in the canteen does not even know under which counter to get everyone’s lunch and other meals. But this is now just a minor thing. Unfortunately, this is a characteristic feature of our class, we have children suffering from anger outbursts, brain disorders, motor coordination problems, autism, and mutism, and in this class of 27, we even have a hearing-impaired child, and this is certainly the cause why there are so many students with special educational needs. P10 10:18

A supportive school environment and teachers with the right professional qualifications are essential for inclusive education to be effective:

… since one of our classes has become inclusive, it's a great mix because we have a special needs teacher for children with special educational needs, a special needs assistant, a teaching assistant, a development teacher, a school nurse, and a school doctor, the doctor is there once a week, the nurse is there twice a week, if I remember well. I haven’t mentioned that there’s a full-time school psychologist, who came from the university, worked there and is now employed full-time. P11 11:3 ()

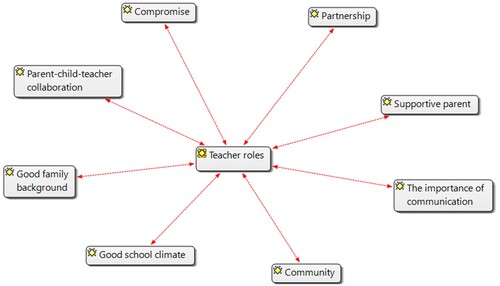

The third main topic presents the segments of teacher roles the interviewed teachers consider important values in inclusive education.

Among the eight related sub-topics, the importance of communication, the role of community, and parent–child-teacher collaboration were prominent.

I think it’s very important to have this parent–child-teacher, this triad; it’s very important. So that we don’t talk past each other. I might say something; the child might say something different at home, so we always have to clarify things; it’s very important. P1 1:29

I think communication with parents is very important, so constant conversation, discussion, providing information, that’s one of my goals, and I think that’s the only way we can work together and move forward. P4 4:22

In addition, a high proportion of the interviewed teachers mentioned the inclusive approach in their schools and the view that a good school climate contributes greatly to the proper education and development of children.

On this, I think that we as teachers, knowing that we work in such a disadvantaged community, we do what we can for the children and their families, whoever is a partner in this can be shaped and helped, but whoever is not a partner, whether it’s a child or a parent, I think it’s much more difficult to cope with. P9 9:11

The children are generally peaceful, and the environment provides such a relaxed atmosphere for the students. P15 15:1

In the other interviews, teachers identified the added values families could provide regarding education and parenting. These include, in this case, parents’ acceptance of their child’s education at school and their partnership with school professionals. They create a harmonious, community environment for their child.

So they wanted to be (partners) with me, yes, they were partners, they were partners in this. P16 16:26

There are families in our class that stand out, who have a better financial background, where both parents are working, or they seem to want to break out of this poverty. P14 16:6 ()

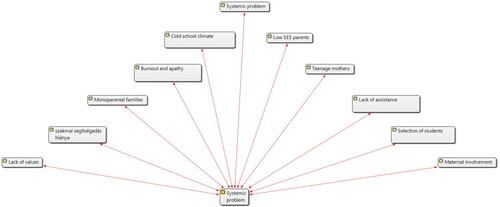

The fourth main topic addresses systemic problems. It is a significant topic with 11 sub-topics. All but three sub-topics (cold school climate, lack of assistance, selection of students) appear frequently in the interviews. Some problems are primarily related to families, others to the school.

Problems and difficulties in families are important because they have a significant impact on children’s situation, opportunities, and performance at school. Families with low SES may also have difficulties in providing basic conditions. Often this is exacerbated by a lack of values. Special care and attention at home would be of paramount importance for these children. However, difficulties are common:

‘And it’s simply not possible for parents to help a child even if they would like to because … either they are not following the child’s studies or they are simply unable to do these tasks or provide help, so their abilities are also limited.

As in Hungary, divorces are increasingly frequent, and single-parent families can cause additional problems which may affect children’s psychological development, school behaviour, and academic performance.

In solving problems and difficulties at school, it is the mother whom teachers can contact most often:

… In these large families, it’s usually observed that the man is away in another town, and I even know of some who work abroad, and the mother usually takes care of the family’s affairs, including contact with the school, so this is very, very often the case.

Teachers’ well-being has a major impact on the quality of education, therefore it is essential to identify the factors which make their work difficult. Tension over administrative burdens is a systemic problem, which can be exacerbated by deadlines, a cold school climate, cliquishness, and conflicts over unresolved issues.

All this can lead to burnout, a common phenomenon among teachers today. This can also have serious consequences for children. Children find it difficult to work with a teacher who applies poor methodology and is impatient, tired, and unmotivated. Several conflicts may arise in the teacher-student-parent relationship. The situation of teachers working with children with special educational needs is also hindered by the lack of qualified professionals, which prevents them from providing the necessary support and development for children. Unfortunately, teachers also tend to ignore the statutory requirements for treatment and attention, which can often lead to further conflict ().

There are several ways to tackle systemic problems. It is important to establish a connection between the school, children, and parents and to find solutions together. This can be achieved by providing professional help, assisting children in catching up and involving and educating parents. The presence of professionals in the school who are able to help is crucial:

Since one of our classes has become inclusive, it's a great mix because we have a special needs teacher for children with special educational needs, a special needs assistant, a teaching assistant, a development teacher, a school nurse, and a school doctor, the doctor is there once a week, the nurse is there twice a week, if I remember correctly. I haven’t mentioned that there’s a full-time school psychologist, who came from the university, worked there and is now employed full-time.

In addition to helping children develop, assisting them in bridging any potential gaps is also key: ‘There is a separate textbook for him, we hold catch-up sessions with colleagues for him with other methods, but he really needs individual treatment and attention'.

Whether parents can help their children at home is crucial to student progress. It is, therefore, worth focusing on the education of parents.

We have events for them, lectures on hygiene, healthy eating, so there are events at school where we invite parents … And we also have joint events for the entire school where parents can ask questions and get help, for example, on how to deal with their adolescent child and what limit they can allow. A nurse usually comes to the school and gives them a presentation through the program, which is related to the university, so they also contact the university students in the Let’s Teach Program. They have a very good relationship, and I have seen in three years that it’s not only necessary for learning, but they also talk about their problems.

As education often presents challenging situations, religious support in church-run schools can be helpful.

Well, according to our educational program, we educate children in a parent-teacher-church framework. The focus of all these is the child, so they have the same goal. That’s why we think it’s very important to have relationships within the institution because parents enroll their child here while they want their child to have a Christian education, and the teacher implements that here in the school, and we have the church supporting us, which also helps our work through its principles.

Discussion

In Category 1 of the typology, the interviewed teachers outlined a classic pattern of teacher-parent interactions. This features a polarised way of thinking, expressed through codes corresponding to opposite poles: the negative and the positive, the discussion based on the distinction between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ (Braley Citation2012; Taylor, Smiley, and Richards Citation2015). Despite the emphasis of contemporary inclusive education policies on the importance of collaboration and its positive returns (Christenson and Sheridan Citation2003; Crouter et al. Citation2004; Welch Citation1998), current practice distinguishes between good and bad partnership in relation to the social, cultural, and economic space surrounding schools. While aimlessness, difficult communication, superficial and infrequent contact, rejection, and passivity often result in aggressive conduct, interpretations in positive directions emphasise the importance of trusting relationships and the strengthening of teacher-parent partnerships. In many cases, polarisation is present to such an extent that the commonalities between ‘us’ and ‘them’ are completely ignored, and extreme differences of opinion are highlighted. The school-family relationship may thus evolve into alienating and intolerant roles. Mutual respect and knowledge transfer can be strengthened by involving families, sharing good practices, and enabling joint dialogue (Unger et al. Citation2001). Schools aim to create an inclusive educational environment that offers all children valuable and equitable educational opportunities. Without qualified professionals and methodological tools, however, achieving the goals of providing the necessary conditions for the inclusive education of children with SEN and disadvantages or multiple disadvantages is impossible.

The pedagogical diagnoses in the second main category, which are the basis for the right to access special treatment services, are presented in the form of labelling (Biklen Citation2010). Pedagogical diagnoses are essential assessments used to determine the appropriate interventions and support services that students with disabilities or special needs require to receive a high-quality education. These assessments help identify individual students’ unique learning profiles, challenges, and strengths. However, it is crucial to understand that these diagnoses are often given as labels such as specific learning difficulties, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and so on. It is important to be aware of this labelling and to focus on addressing individual students’ needs based on their unique learning profiles, as opposed to their formal diagnostic label. In several cases, the interviewed teachers provided vague concepts and explanations when describing the diagnoses which define their students’ special educational needs. Students’ atypical ability profiles were mostly labelled as behavioural problems, and teachers were often unaware of or misused the categories of SEN classification in the literature. Creating an inclusive school environment, based on a change in pedagogical culture and methodological approach, focuses on meeting individual needs (Swaans et al. Citation2014). However, the analysis reveals that the inclusive approach, which may apply in theory, has a rudimentary scope in practice. Due to significant differences across schools, teachers in segregated schools tend to focus on what stands out from the average, whereby heterogeneity is associated with the tiresome additional workload, as in many cases, there is a lack of supporting professionals and interdisciplinary teamwork based on a team model.

In the third main category, we identify responsibilities which teachers highlighted in the interviews as important elements for the effectiveness of inclusive education. According to the teachers, adequate and regular communication with parents is essential for joint education and aligning school and family values (Pianta and Walsh Citation2014). A cohesive community formed by parents and teachers alike, which is characterised by being willing and able to cooperate, was identified as a fundamental pillar for the success of joint education. Teachers also stressed that, in addition to these two factors, children should also be considered an integral part of the collaboration, whereby the parent-teacher–child relationship is understood as a three-fold alliance to support a smooth teaching and learning process. The corpus on parent–child-teacher partnership shows teachers’ views on the added value parents may bring to this collaboration. These include the ability to work in partnership with school staff, a stable family background, and parents’ ability to listen to advice and be willing to incorporate it into their parenting. In addition, schools could provide the conditions for an inclusive approach to education. Participants indicated this means the attempt to teach with consideration to students’ individual needs while also differentiating and grading according to individual abilities. The success of all these practices can be enhanced if the atmosphere of an educational institution favours inclusion, ensures acceptance, and supports students. This endows students with space for social and emotional development to thrive more easily among their peers (Casale and Hennemann Citation2019).

The fourth main category relates to systemic problems. A broad spectrum of difficulties affecting society as a whole has been identified, some of which are primarily linked to families and others to schools. However, all have a significant impact on children’s performance at school and on their quality of life. The low socio-economic status of families determines children’s school careers. They are more risk averse and more concerned with immediate results, and therefore do not value learning and investing in the future (Boudon, Citation1998). The Hungarian school system further increases social disparities (Széll, Citation2020), and the lack of values and support at home also set back children’s development. The high divorce rate in Hungary is a trend that affects the entire country, creating further difficulties for families and children. The open and permissive world, cultural background, and customs of national and ethnic minorities, which differ from those of the majority, often lead to the issue of teenage motherhood. These social challenges are compounded by the lack of financial and moral recognition for teachers, the lack of qualified professionals to support their work, the inability to cope with daily challenges, and the lack of supervision for teachers in challenging environments, which can easily lead to burnout. Feelings of powerlessness, lack of qualified professionals, administrative workload, tensions in schools, and the resulting stressful and tense environment have a profound impact on teachers’ well-being and sense of vocation. In response to frustrating working conditions, teachers may also ignore expert advice and fail to meet the statutory requirements for treatment and attention to students, making it even more difficult for them to progress.

In the fifth main category, we have compiled a list of possible solutions to the problems. It is clear that solutions require active participation and cooperation from all stakeholders. If the corresponding education policy strategy addresses the problem in a relevant way, the school and the institution can provide professional support staff and individual attention to children with special educational needs while also offering opportunities for the development and training of parents so that this system can lay the foundations for children’s progress (Pianta and Walsh Citation2014). Another contributing factor may be religious support, which can have an impact on how both children and their parents cope with challenges.

Conclusion

In summary, this study has followed the contextual systems model, looking for systemic problems and solutions in the narrower school context and the wider institutional educational environment. The results show that individual, organisational, and social factors (micro-, meso-, and exo-system) are prominent in determining family involvement in a child’s education. The qualitative nature, the difficult accessibility of the target group, and the complex nature of social status and SEN diagnosis in Hungary are limitations of the study. It also emerged from the previous results that, in the case of most of the teachers, there is a significant lack of knowledge regarding specific educational needs, so when formulating our conclusions, we made sure to keep in mind that what the teachers said only their personal interpretations and perceptions of their own experiences. However, our results prove to fill a gap, because we could investigate further into the deep structures of this difficult-to-investigate area with the help of qualitative research.

The results also identified several gaps in teachers’ knowledge about neurodiversity, as well as in the sensitive stages of the intersection between their practical and theoretical knowledge. However, this study analyzed the inclusive approach not in terms of legislation and regulations but in terms of everyday educational practices. The results of the interview analyses suggest that raising awareness of the true content and importance of inclusive pedagogy should be the basis for ongoing professional training and dialogue. Only true understanding and objective insight can create an accepting community of teachers. In special education, defining common objectives is essential for cooperation between families and schools. At the same time, the results underscore that students’ interests are often only represented by uncertain actors or a scarce supply of professionals in individual school environments and, in many cases, throughout the school system. Furthermore, families’ low SES and teachers’ cold-integration mentality may also lead to serious tensions. Inclusive education can be successful through a substantial investment of resources, complemented by the design and implementation of ongoing collaboration strategies. The interviewed teachers describe and comment on their actual current situation. These are collaborative processes that could potentially create a kind of creative synergy. However, in the current situation, the professional foundation of inclusive education is, unfortunately, at the very end of education as protocols.

Acknowledgments

The research on which this paper is based has been implemented by the MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group and with the support provided by the Research Programme for Public Education Development of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Beáta Andrea Dan

Beáta-Andrea Dan (BAD) is a PhD student at the Department of Doctoral Program on Educational Sciences, University of Debrecen, Hungary, and a SEN teacher at Bonitas Special Education Centre, Romania. Research Focus: special education set, attachment-based education, equity in education, marginalised groups, poverty, inclusive education, and people with disabilities. Faculty of Arts, University of Debrecen, Institute of Educational Studies and Cultural Management, Egyetem Sqr. Debrecen, H-4032, Hungary, [email protected]

Tímea Szűcs

Tímea Szűcs is an assistant professor at the University of Debrecen, Faculty of Humanities, Institute of Educational Studies and Cultural Management, and a researcher of the MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group. She specialises in how music learning can influence students’ academic effectiveness and the manner in which social background affects student performance. Faculty of Arts, University of Debrecen, Institute of Educational Studies and Cultural Management, Egyetem Sqr. Debrecen, H-4032, Hungary, [email protected]

Regina Sávai-Átyin

Regina Sávai-Átyin (RSÁ) is a PhD student at the Department of Doctoral Program on Educational Sciences, University of Debrecen, Hungary, and a researcher of the MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group. Her research focuses on the people and factors which influence the achievement of students with learning and behavioural difficulties. Faculty of Humanities, University of Debrecen, Institute of Educational Studies and Cultural Management, Egyetem Sqr. Debrecen, H-4032, Hungary, [email protected]

Anett Hrabéczy

Anett Hrabéczy (AH) is an assistant lecturer at the University of Debrecen, Faculty of Humanities, Institute of Educational Studies and Cultural Management, and a researcher of the MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group. Her research focuses on higher education students with special educational needs, their academic success, and inclusion in higher education. Faculty of Arts, University of Debrecen, Institute of Educational Studies and Cultural Management, Egyetem Sqr. Debrecen, H-4032, Hungary, [email protected]

Karolina Eszter Kovács

Karolina Eszter Kovács (KEK), PhD, is a psychologist and senior lecturer at the University of Debrecen, Faculty of Humanities. Her research focus is on health behaviour and sports habits of various groups, e.g. students and teachers. Institute of Psychology, Faculty of Arts, University of Debrecen, Egyetem Sqr. 1., Debrecen, H-4032, Hungary, [email protected]

Gabriella Ridzig

Gabriella Ridzig (GR) is a teacher education student at the University of Debrecen, Faculty of Humanities, and a trainee at the MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group. She focuses on higher education students with special educational needs, their academic success, and their inclusion in higher education. Faculty of Humanities, University of Debrecen, Institute of English and American Studies, Egyetem Sqr. Debrecen, H-4032, Hungary, [email protected]

Dávid Kis

Dávid Kiss (DMK) is a teacher education student specialising in History and IT at the University of Debrecen and a research intern in the CHERD internship programme. His research focuses on the Let’s Teach for Hungary Mentor Program and ICT tools in education. Faculty of Informatics, University of Debrecen, 26 Kassai Road, H-4028 Hungary, [email protected]

Katinka Bacskai

Katinka Bacskai (KB), PhD, is a sociologist and lecturer at the University of Debrecen, Faculty of Humanities, Institute of Educational Studies and Cultural Management, and a researcher of the MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group. Her research focuses on teacher effectiveness and characteristics of teachers in public and private schools. Faculty of Arts, University of Debrecen, Institute of Educational Studies and Cultural Management, Egyetem Sqr. Debrecen, H-4032, Hungary, [email protected]

Gabriella Pusztai

Gabriella Pusztai (GP) is a D.Sc. habil., professor at the University of Debrecen, Faculty of Humanities, and the head of the Doctoral School of Human Sciences, the Center for Higher Educational Research and Development (CHERD-H), and MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group. Her main research interests relate to cultural and religious groups’ representation in education. Faculty of Arts, University of Debrecen, Institute of Educational Studies and Cultural Management, Egyetem Sqr. Debrecen, H-4032, Hungary, [email protected]

References

- Anderson, J., and C. Boyle. 2015. “Inclusive Education in Australia: Rhetoric, Reality and the Road Ahead.” Support for Learning 30 (1): 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12074.

- Arishi, L., C. Boyle, and F. Lauchlan. 2017. “Inclusive Education and the Politics of Difference: Considering the Effectiveness of Labelling in Special Education.” Educational and Child Psychology 34 (4): 9–19. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2017.34.4.9.

- Babbie, E. R. 1986. The Practice of Social Research. 4th ed. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth Pub. Co.

- Balli, D. 2016. “Importance of Parental Involvement to Meet the Special Needs of Their Children with Disabilities in Regular Schools.” Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 5 (1): 147–152.

- Bariroh, S. 2018. “The Influence of Parents’ Involvement on Children with Special Needs’ Motivation and Learning Achievement.” International Education Studies 11 (4): 96. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v11n4p96.

- Biklen, D. 2010. Schooling Without Labels: Parents, Educators, and Inclusive Education. Temple University Press.

- Blackman, S., and E. Mahon. 2016. “Understanding Teachers’ Perspectives of Factors That Influence Parental Involvement Practices in Special Education in Barbados.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 16 (4): 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12083.

- Boudon, R. 1998. “Limitations of Rational Choice Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 104 (3): 817–828.

- Braley, C. 2012. Parent-Teacher Partnerships in Special Education. Honors Projects Overview. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/65. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1066&context=honors_projects.

- Brussino, O. 2020. Mapping Policy Approaches and Practices for the Inclusion of Students with Special Education Needs. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 227. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/600fbad5-en.

- Bryant, A., and K. Charmaz. 2012. “Grounded Theory and Psychological Research.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, edited by H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher, 39–56. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Budde, J., and M. Hummrich. 2015. “Inklusion aus erziehungswissenschaftlicher Perspektive [Inclusion from an Educational Science Perspective].” Erziehungswissenschaft 26 (2): 13–14. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:11569.

- Carlisle, E., L. Stanley, and K. M. Kemple. 2005. “Opening Doors: Understanding School and Family Influences on Family Involvement.” Early Childhood Education Journal 33 (3): 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-005-0043-1.

- Casale, G., and T. Hennemann. 2019. “Schulklima und Pädagogik bei Gefühls- und Verhaltensstörungen. Aktueller Forschungsstand und erste Ergebnisse bei Schülerinnen und Schülern mit Symptomverhalten [School Climate and Pedagogy in Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Current Research and Initial Findings in Students with Symptomatic Behavior].” Emotionale und soziale Entwicklung in der Pädagogik der Erziehungshilfe und bei Verhaltensstörungen: ESE 1 (1): 56–72. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:25183.

- Charmaz, K. 2017. “Constructivist Grounded Theory.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 12 (3): 299–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262612.

- Christenson, L., and M. Sheridan. 2003. “School and Families: Creating Essential Connections for Learning. New York: The Guilford Press. 246 pp. $32. 00.” Psychology in the Schools 40 (4): 444–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10101.

- Crouter, A. C., M. R. Head, S. M. Mchale, and C. J. Tucker. 2004. “Family Time and the Psychosocial Adjustment of Adolescent Siblings and Their Parents.” Journal of Marriage and Family 66 (1): 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00010.x-i1.

- Dafinoiu, I., and O. Lungu. 2003. Research Methods in the Social Sciences / Metode de cercetare în ştiinţele sociale. https://www.peterlang.com/document/1095417.

- Elkins, J., C. E. Van Kraayenoord, and A. Jobling. 2003. “Parents’ Attitudes to Inclusion of Their Children with Special Needs.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 3 (2): 122–129.

- Epstein, J. L. 2010. “School/Family/Community Partnerships: Caring for the Children we Share.” Phi Delta Kappan 92 (3): 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171009200326.

- Epstein, J. L. 2018. “School, Family, and Community Partnerships in Teachers’ Professional Work.” Journal of Education for Teaching 44 (3): 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1465669.

- Gaad, E, and L. Khan. 2007. “Primary Mainstream Teachers' Attitudes towards Inclusion of Students with Special Educational Needs in the Private Sector: A Perspective from Dubai.” International Journal of Special Education 22 (2): 95–109.

- Green, S., C. Davis, E. Karshmer, P. Marsh, and B. Straight. 2005. “Living Stigma: The Impact of Labeling, Stereotyping, Separation, Status Loss, and Discrimination in the Lives of Individuals with Disabilities and Their Families.” Sociological Inquiry 75 (2): 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.2005.00119.x.

- Harper, D., and A. R. Thompson, eds. 2011. Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners. 1st ed. Oxford: Wiley.

- Haslam, N., L. Rothschild, and D. Ernst. 2002. “Are Essentialist Beliefs Associated with Prejudice?” British Journal of Social Psychology 41 (1): 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466602165072.

- Hattie, J. 2008. Visible Learning. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Heimdahl Mattson, Eva, Siv Fischbein, and Lise Roll-Pettersson. 2010. “Students with Reading Difficulties/Dyslexia: A Longitudinal Swedish Example.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (8): 813–827. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110902721662.

- Horvat, E. M., E. B. Weininger, and A. Lareau. 2003. “From Social Ties to Social Capital: Class Differences in the Relations Between Schools and Parent Networks.” American Educational Research Journal 40 (2): 319–351. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040002319.

- Hrabéczy, A., T. Ceglédi, K. Bacskai, and G. Pusztai. 2023. “How Can Social Capital Become a Facilitator of Inclusion?” Education Sciences 13 (2): Article 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020109.

- Jigyel, K., J. A. Miller, S. Mavropoulou, and J. Berman. 2020. “Benefits and Concerns: Parents’ Perceptions of Inclusive Schooling for Children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in Bhutan.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (10): 1064–1080. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1511761.

- Jordan, A. 2018. “The Supporting Effective Teaching Project: 1. Factors Influencing Student Success in Inclusive Elementary Classrooms.” Exceptionality Education International 28 (3): Article 3. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v28i3.7769.

- Karisa, A., J. McKenzie, and T. De Villiers. 2021. “‘Their Status Will be Affected by That Child’: How Masculinity Influences Father Involvement in the Education of Learners with Intellectual Disabilities.” Child: Care, Health and Development 47 (4): 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12864.

- Klicpera, C., and B. Gasteiger Klicpera. 2004. “Vergleich zwischen integriertem und Sonderschulunterricht: Die Sicht der Eltern lernbehinderter Schüler [Comparison between Integrated and Special Education: The Perspective of Parents of Pupils with Learning Disabilities].” Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie 53 (10): 685–706. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:2712.

- Koutsoklenis, A., and V. Papadimitriou. 2021. “Special Education Provision in Greek Mainstream Classrooms: Teachers’ Characteristics and Recruitment Procedures in Parallel Support.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 28 (5): 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1942565.

- Kvande, M. N., J. Belsky, and L. Wichstrøm. 2018. “Selection for Special Education Services: The Role of Gender and Socio-Economic Status.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 33 (4): 510–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1373493.

- Lénárt, A., A. Lecheval, and A. Watkins. 2022. “European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education 2022.” In 2018/2019 School Year Dataset Cross-Country Report, edited by The European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education (EASIE), 7–196. Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/EASIE-2018-2019-cross-country-report.

- López-López, M. C., M. A. Romero-López, and E. F. Hinojosa-Pareja. 2022. “School Management Teams in the Face of Inclusion: Teachers’ Perspectives.” Journal of Research on Leadership Education 19, https://doi.org/10.1177/19427751221138875.

- Müller, K., and S. Hoffmann. 2019. “Interprofessionelle Kooperation in der inklusiven Beschulung von Schülerinnen und Schülern mit emotional-sozialem Förderbedarf [Interprofessional Cooperation in Inclusive Schooling for Students with Emotional-Social Support Needs].” Emotionale und soziale Entwicklung in der Pädagogik der Erziehungshilfe und bei Verhaltensstörungen: ESE 1 (1): 198–208. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:25193.

- Perlusz, A. 2010. A hallássérült gyermekek integrációja. [Integration of Hearing Impaired Children]. Budapest: Fogyatékosok Esélye Közalapítvány.

- Pianta, R., and D. Walsh. 2014. High-Risk Children in Schools: Constructing Sustaining Relationships. Oxford: Routledge.

- Poon-Mcbrayer, K. F. 2017. “School Leaders’ Dilemmas and Measures to Instigate Changes for Inclusive Education in Hong Kong.” Journal of Educational Change 18 (3): 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-017-9300-5.

- Pusztai, G., and H. Fényes. 2022. “Religiosity as a Factor Supporting Parenting and Its Perceived Effectiveness in Hungarian School Children’s Families.” Religions 13 (10): Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100945.

- Rothì, D. M., G. Leavey, and R. Best. 2008. “On the Front-Line: Teachers as Active Observers of Pupils’ Mental Health.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (5): 1217–1231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.09.011.

- Rouse, M., and L. Florian. 2006. “Inclusion and Achievement: Student Achievement in Secondary Schools with Higher and Lower Proportions of Pupils Designated as Having Special Educational Needs.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 10 (6): 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110600683206.

- Sántha, K. 2009. Bevezetés a kvalitatív pedagógiai kutatás módszertanába [Introduction to Qualitative Pedagogical Research Methodology]. Budapest: Eötvös József Könyvkiadó.

- Sántha, K. 2011. Abdukció a kvalitatív kutatásban [Abduction in Qualitative Research]. Budapest: Eötvös József Könyvkiadó.

- Sántha, K. 2012. “Numerikus problémák a kvalitatív megbízhatósági mutatók meghatározásánál [Numerical Problems in the Determination of Qualitative Reliability Indicators].” Iskolakultúra 25 (3): Article 3. https://doi.org/10.17543/ISKKULT.2015.3.3.

- Sántha, K. 2015a. “Kvalitatív Komparatív Analízis a pedagógiai térábrázolásban [Qualitative Comparative Analysis in Pedagogical Perspective].” Iskolakultúra 25 (3): 3–14. https://doi.org/10.17543/ISKKULT.2015.3.3.

- Sántha, K. 2015b. Trianguláció a pedagógiai kutatásban [Triangulation in Pedagogical Research]. Budapest: Eötvös József Könyvkiadó.

- Sántha, K. 2015c. “Beavatkozás nélküli vizsgálatok. [Non-Interventional Tests].” Új Pedagógiai Szemle 57: 7–8. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00035/00115/2007-07-ta-Santha-Beavatkozas.html.

- Sebastian, K. 2019. “Distinguishing Between the Strains Grounded Theory: Classical, Interpretive and Constructivist.” Journal for Social Thought 3 (1): 1–9. https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/jst/article/view/4116.

- Silva, J. C., and J. Morgado. 2004. “Support Teachers’ Beliefs About the Academic Achievement of Students with Special Educational Needs.” British Journal of Special Education 31 (4): 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00356.x.

- Swaans, K., B. Boogaard, R. Bendapudi, H. Taye, S. Hendrickx, and L. Klerkx. 2014. “Operationalizing Inclusive Innovation: Lessons from Innovation Platforms in Livestock Value Chains in India and Mozambique.” Innovation and Development 4 (2): 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2014.925246.

- Széll, K. 2020. “Iskola a társadalomban – társadalom az iskolában [School in Society - Society in School].” Új Pedagógiai Szemle 70 (5–6): 88–98.

- Szumski, G., J. Smogorzewska, and M. Karwowski. 2017. “Academic Achievement of Students without Special Educational Needs in Inclusive Classrooms: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Research Review C (21): 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.02.004.

- Taylor, R. L., L. R. Smiley, and S. Richards. 2015. Exceptional Students: Educating all Teachers for the 21st Century. Second edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Unger, D. G., C. W. Jones, E. Park, and P. A. Tressell. 2001. “Promoting Involvement Between low-Income Single Caregivers and Urban Early Intervention Programs.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 21 (4): 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/027112140102100401.

- Vaismoradi, M., J. Jones, H. Turunen, and S. Snelgrove. 2016. “Theme Development in Qualitative Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis.” Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 6 (5): 100. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v6n5p100.

- Varga, J., ed. 2022. A közoktatás indikátorrendszere 2021 [2021 Indicator System for Public Education]. Budapest: Közgazdaság- és Regionális Tudományi Kutatóközpont.

- Welch, M. 1998. “Collaboration: Staying on the Bandwagon.” Journal of Teacher Education 49 (1): 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487198049001004.

- Wilt, C. L., and M. E. Morningstar. 2018. “Parent Engagement in the Transition from School to Adult Life Through Culturally Sustaining Practices: A Scoping Review.” Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 56 (5): 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-56.5.307.