ABSTRACT

The topic of distributed pedagogical leadership has attracted researchers’ interest in early childhood education leadership. A growing body of research focuses on investigating leadership enacted between leaders and teachers in ECE settings. In this article, we focus on the enactment of distributed pedagogical leadership in Finnish ECE settings and their relations to teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership on staff teams. The study employed an explanatory sequential mixed methods design. Data on the perceptions of 130 ECE professionals, ECE center directors, ECE teachers, and child care nurses on the enactment of distributed pedagogical leadership and teacher commitment were collected with a survey. A qualitative inquiry included six ECE professional interviews. The results indicate that the studied ECE centers have adopted leadership approaches congruent with distributed pedagogical leadership and the implementation of distributed forms of leadership related positively with the ECE teacher’s ability to lead reflection and learning in their teams.

Introduction

The significance of this study arises from a global interest in investigating Early Childhood Education (ECE) leadership from distributed perspectives and especially teachers’ involvement in enacting pedagogical leadership in their teams (Aubrey, Citation2016; Boe & Hognestad, Citation2017; Waniganayake, Cheeseman, Fenech, Hadley, & Shepherd, Citation2017). Findings (Aubrey, Citation2016; Ho, Citation2011; Waniganayake et al., Citation2017; Waniganayake, Heikka, & Halttunen, Citation2018) indicate that responsibilities for pedagogical leadership are enacted between leaders and teachers, and these processes are influenced by sufficient implementation of distributed leadership as well as teachers’ skills and positions in enacting pedagogical leadership in their teams. However, research shows that ECE teachers are typically not well-prepared to lead pedagogical improvement in their teams (Heikka, Halttunen, & Waniganayake, Citation2016; Waniganayake, Rodd, & Gibbs, Citation2015).

Contemporary research suggests that distributed forms of leadership have a positive impact on teachers and can assist in reaching the goals set for ECE by enhancing the professional development of ECE staff, fostering informed curriculum reform in ECE settings, supporting pedagogical development and organizational change, and thereby improving the pedagogical functioning of multi-professional staff teams (Heikka, Waniganayake, & Hujala, Citation2013; Waniganayake et al., Citation2015). Despite notions of the critical role of ECE teachers in achieving these results through the implementation of distributed leadership, the research does not clearly address the relationships between the implementation of distributed leadership and teachers’ commitment to lead pedagogical improvement in their teams.

ECE teachers’ work is highly affected by local regulations and steering (Peterson et al., Citation2016). In the Finnish system, ECE is understood as education, teaching, and care, and it is accomplished in co-operation with a multi-professional (child care nurse and ECE teacher) staff team, which includes at minimum one pedagogically educated, university qualified ECE teacher (Bachelor of Early Childhood Education). The recent legislation reform has clarified the roles and responsibilities of the multi-professional staff team. ECE teacher has the pedagogical responsibility for planning, implementing, and assessing early childhood education in the child group and in individual children (Act 540/Citation2018) Teachers are relatively free to make decisions in their child groups (Rosemary & Puroila, Citation2002). In Finland, the work of ECE center directors is dependent on the decision-making and structures of the municipality. The center director’s work is typically separated from the teachers’ work with children, and teachers lack authority, power, and support for their leadership (Alila et al., Citation2014; Halttunen, Citation2009; Heikka, Citation2014). However, new findings indicate that teacher leadership is highly anticipated among ECE professionals in Finland (Heikka, Halttunen, & Waniganayake, Citation2018).

In Finland, ECE teacher operating environment is regulated by law and steered by curricula. ECE teachers work in ECE centers or preschools with children aged from 1 to 6 years. In the groups of children under three years, the adult/child ratio is 1/4. In groups with full-time children over three years, the adult/child ratio is 1/8, and in groups with part-time children, the ratio is 1/13 (Act 540/Citation2018). The Act on Early Childhood Education (Act 540/Citation2018) sets the goals for ECE and is steered by the National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care (Finnish National Agency for Education [EDUFI], Citation2018). Pre-primary education, which is one-year preschool for 6-year-old children, is legislated in the Basic Education Act (Act 680/Citation1998) and is steered by the Core Curriculum for Pre-primary Education (EDUFI, Citation2014). Municipal authorities prepare the local curricula in compliance with the core curricula. In addition, a personal ECE plan is drawn up by an ECE teacher for each individual child (EDUFI, Citation2018).

ECE services are mainly provided by municipalities. The multi-level municipality organizations in Finland set particular challenges in implementing ECE leadership. The framework of distributed pedagogical leadership (Boe & Hognestad, Citation2017; Heikka, Citation2014; Heikka et al., Citation2016, Citation2018) provides a useful lens through which to assess the pedagogical leadership enacted in municipality organizations. In these organizations, ECE leadership is distributed between diverse stakeholders, including center directors and ECE teachers working at ECE centers, in addition to municipal functions and state-level steering and policies. This complex organizational structure impedes the enactment of pedagogical leadership through diverse ECE stakeholders.

Distributed pedagogical leadership

In recent years, there has been considerable discussion about the concept of distributed pedagogical leadership (Boe & Hognestad, Citation2017; Male & Palaiologou, Citation2017; Sims, Forrest, Semann, & Slattery, Citation2015). For example, Boe and Hognestad (Citation2017) suggest that the concept of hybrid leadership (Gronn, Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2011) is more suitable for describing the leadership roles of teachers. Their argument draws from the notion that leadership is a combination of individual and collaborative work. This perception disregards the core elements of distributed leadership, that leadership is enacted by formal and informal leaders separately but interdependently and that leadership is distributed over the organization by means of both people and contexts (Spillane, Citation2006; Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, Citation2001). Interdependence between the leadership enactments by different leadership stakeholders is crucial for leaders and teachers to achieve common goals. For example, Sims et al. (Citation2015) emphasize that the essence of distributed leadership is the creation and development of the shared meaning of the organization by all staff members. In Finland, for example, leadership stakeholders work relatively individually in geographically dispersed locations. An ECE center director usually leads a cluster comprising 2‒3 centers. This is one reason for distributing pedagogical leadership and for emphasizing the role of ECE teachers as one of pedagogical leadership. In such contexts, a leadership approach that creates interdependence between leadership stakeholders through shared construction and enactment of visions and strategies is even more crucial.

Heikka (Citation2014) has identified five dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership in the ECE organization that create a zone of interdependence ().

Table 1. Dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership in the ECE organization (Heikka, Citation2014)

The first dimension, Enhancing shared consciousness of visions and strategies between the stakeholders, depicts pedagogical leadership as a dynamic process that involves ECE professionals within one municipality in a shared construction of the understanding of visions and strategies. This characteristic of leadership is conducive to enhancing interdependence between different professional groups within a municipal ECE organization.

Distributing responsibilities for pedagogical leadership can be promoted by focusing on the roles and responsibilities of the ECE teachers within pedagogical team processes. This dimension entails university qualified teachers taking responsibility for pedagogy and guiding the planning and assessment of pedagogical practices within their teams according to plans that are jointly formulated (EDUFI, Citation2018). Teachers’ involvement in leadership has recently been conceptualized within the framework of teacher leadership (Heikka et al., Citation2018, Citation2016; Ho & Tikly, Citation2012; Li, Citation2015; Wang & Ho, Citation2018). Teacher leadership means that the ECE teacher performs the functions and responsibilities expected of a leader (Harris, Citation2003). Teacher leadership functions and responsibilities discussed in global research studies include leading curriculum and pedagogy; organizing daily activities in the child groups; arranging the division of labor in the teams; coordinating collaboration with parents; enhancing pedagogical development; guiding teaching practices of nurses/assistants and supporting their professional learning. In addition to team-level leadership tasks, the teacher is to co-operate and participate in decision-making at the center level with the center director (Colmer, Waniganayake, & Field, Citation2015; Harris, Citation2003; Heikka et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Ho, Citation2011; Hognestad & Boe, Citation2014, Citation2015; York-Barr & Duke, Citation2004).

The third dimension, Distributing and clarifying power relationships between the stakeholders, includes enhancing center directors’ and teachers’ participation in decision-making about developmental proceedings in municipalities (Heikka & Hujala, Citation2013). The authority is shared as the teachers work independently but interdependently as pedagogical developers in their own child groups.

Distributing the enactment of pedagogical improvement within centers involves designing distributed leadership functions between center directors and teachers. In distributed leadership enactment, center directors and teachers have separate but interdependent responsibilities and tasks in pedagogical leadership. This involves teachers as active facilitators of pedagogical reflection, learning and development in their teams and at the center in a broad sense (Colmer et al., Citation2015). The National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care (EDUFI, Citation2018), also demands building a working culture in which all ECE professionals learn and develop pedagogical practice together. To develop pedagogy and working culture in a team, critical reflection is crucial (Brookfield, Citation2009, Citation1995). However, research (Heikka et al., Citation2018; Waniganayake et al., Citation2018) indicates that teams differentiate on how they reflect their pedagogical practices. Teachers have the power to inhibit or nourish pedagogical improvement in the team. ECE teachers differentiate in relation to their skills and commitment to lead the team to critical reflection and learning or to encourage the participation of child care nurses in planning and assessment. Waniganayake et al. (Citation2018) have noted that teachers’ abilities to listen to child care nurses’ observations of children enrich reflexivity in the team. Reflective practices are connected to a team’s ability to develop practices.

The final dimension, Developing strategy for distributed pedagogical leadership, is based on evidence that the enactment of distributed leadership should be well-planned, goal-oriented, and assessed and developed regularly (Heikka et al., Citation2013). The strategy for distributed pedagogical leadership makes leadership procedures and responsibilities explicit for professionals.

Based on the findings of our previous study, three main aims for the present study were identified. First, to investigate how the dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership are enacted in ECE. Second, as ECE teachers’ commitment to pedagogical leadership responsibilities is suggested to be crucial but to vary among individual teachers, the study aims to examine how ECE professionals perceive the commitment of ECE teachers to lead pedagogy in their staff teams. ECE teachers have the pedagogical responsibility to plan and assess pedagogy in child groups (EDUFI, Citation2018). Thus, the tendency of teachers to plan and assess pedagogy has been identified as one indicator for teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership in this study. Because this level of commitment to basic teacher duties does not implicitly fully accomplish the prerequisites for further practice development and the encouragement of child care nurse participation, this indicator was set to mark low-level teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership. Also based on previous research findings, high-level teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership was identified as an active leading of pedagogical development by enhancing reflection and learning in the teams of the teachers. Third, the study aimed to investigate the relation between the enactments of distributed pedagogical leadership and teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership. This relation has not been studied before in ECE contexts.

The research questions were as follows: How do ECE professionals, ECE center directors, ECE teachers, and child care nurses, perceive the enactment of distributed pedagogical leadership in their settings? How do ECE professionals perceive teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership in their settings and teams? What connections, if any, are there between the enactment of distributed pedagogical leadership and teacher commitment to leadership?

Methods

A mixed methods approach, and particularly the explanatory sequential design (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2018) was employed in this study. The research process began with a quantitative inquiry. Then, we wanted to know and understand the mechanisms that produce certain quantitative analysis results by using a qualitative inquiry. Such a methods design is sequential, i.e. one data set is collected and analyzed before another data set (e.g. Guest, Citation2013). The integration of quantitative and qualitative methodology allows the research to produce a more complete view of the phenomenon (Greene, Caracelli, & Graham, Citation1989), and interpret if both quantitative and qualitative results converge with each other (Lund, Citation2012). Subsequently, data sets are compared and their relationship with each other can be observed, e.g. whether or not they converge, diverge, contradict (Guest, Citation2013, p. 148). In this study, both data sets provided the opportunity to compare results based on convergence, and the qualitative analysis gave some new results.

The research was carried out in a middle-sized town in Finland between the years 2016 and 2018. The study participants represented 10 municipal ECE centers in the area. The data collection was completed as part of a research project specifically designed to support launching the new National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care (EDUFI, Citation2018) and its implementation.

In the quantitative inquiry, the data consisted of an online questionnaire completed by 130 ECE professionals in the selected municipality in Finland. The professional groups chosen for analysis consisted of ECE center directors (N = 8), ECE teachers (N = 52), and child care nurses (N = 70). Five-level Likert scale claims were developed based on the dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership (Heikka, Citation2014).

Three indicators describing different levels of ECE teacher’s commitment to pedagogical leadership were formulated based on contemporary research findings (e.g. Boe & Hognestad, Citation2017; Colmer et al., Citation2015; Heikka, Citation2014; Heikka et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Sims et al., Citation2015; Waniganayake et al., Citation2018). Respondents were asked to choose which of the provided examples best described the ECE teacher in their teams using a teacher commitment category: 1 = pedagogical responsibility of the ECE teacher is not manifest in the educator team; 2 = the ECE teacher plans and evaluates pedagogy but does not involve other educator team members in pedagogical evaluation and planning; 3 = the ECE teacher guides and encourages the educator team towards deep reflection and learning. Analysis was completed using the IBM SPSS 25 statistics program. Statistical analysis of the data shows that reliability measures, the so-called Cronbach alpha coefficients, varied between .81 and .87 in the five sum variables. contains information on each dimension of distributed pedagogical leadership: the number of items, the reliability coefficient, and one example item for each dimension.

Table 2. Reliability α values for five dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership

The data in the qualitative inquiry consisted of six semi-structured (Hirsjärvi & Hurme, Citation2010) theme interviews. Interviewed participants were selected purposefully to represent three different professional groups of ECE, namely ECE center directors, ECE teachers, and child care nurses. Two participants were interviewed from each group. The interview participants were selected to offer relevant information in relation to the research questions because, due to their long-term experience, they were assumed to be able to provide informed insights into staff and leadership practices in the centers. The participants represented three municipal ECE centers. Teacher 1, nurse 1, and center director 1 all represent one ECE center. Director 1 was also responsible for two other centers in the area. Teacher 2 and nurse 2 came from another ECE center, and director 2 represented a third ECE center.

Five interview themes were formulated based on the dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership (Heikka, Citation2014). The interviews were analyzed using deductive qualitative content analysis (Tuomi & Sarajärvi, Citation2018), where the categorization of participants’ original expressions are reflected in the framework of distributed pedagogical leadership (Heikka, Citation2014). The analysis consisted of three phases. An inquiry into substantive content was performed separately among the three professional groups in the first phase. The condensed data were grouped to make possible parallel investigations of professional group perspectives in the second phase. Finally, the analysis of the qualitative findings were compared with the quantitative findings to cross-examine the two data sets in the third phase.

Results

The research results are organized according to the three research questions. Each question is first identified in the study results from the quantitative data and is supported or complemented thereafter with the qualitative data findings.

Sufficient enactment of distributed pedagogical leadership

The results indicate that the professional groups perceive the dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership to be implemented sufficiently in the centers (mean average from 3.52 to 3.73), with the highest implementation of Enhancing shared consciousness of visions and strategies between stakeholders, and the lowest implementation of Distributing and clarifying the power relationships between the stakeholders ().Footnote1

Table 3. Descriptives of dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership by profession

The different professional groups had relatively similar views, i.e. no statistically significant differences were found (significance ranges from .38 to .77) ().

Table 4. One-way ANOVA results for comparisons between groups of professions

Interview findings offer some explanations of the unity of results in the quantitative data. The findings unanimously indicate that solid structures for regular pedagogical discussion and evaluation are perceived to give rise to the enhancement of a shared consciousness of a pedagogical vision. The role of the ECE center director in guiding the construction of shared consciousness and pedagogical proceedings was reported by all professional groups to be crucial in fostering shared understanding. However, one center director felt that there is substantial variation between ECE centers in terms of the extent and understanding of the pedagogical vision shared by all staff members.

ECE teachers and child care nurses perceived the teachers’ overall pedagogical responsibility to be clear and well enacted. The creation of structures for leadership and the clarity of roles and responsibilities were perceived by teachers and center directors as crucial for distributing responsibilities for pedagogical leadership. In addition, the new ECE law and national ECE curriculum were reported to have clarified roles and responsibilities by emphasizing the pedagogical responsibility of the teacher. Teachers perceived their pedagogical responsibility to be based on their education and to be inherently built into the teacher profession. Child care nurses reported that they understood and encouraged the pedagogical leadership of the teacher, as shown in the following excerpt:

‘I feel that I am equal (to them), but of course we have a different education, so I give it to them that they take care of the pedagogical planning, but they also listen to me really well and incorporate my thoughts into the proceedings. – We have weekly meetings for planning in teams and of course the teachers have the overall responsibility for that … – ‘. (Child care nurse 1.)

ECE teachers and child care nurses felt that efficient development of a strategy for distributed pedagogical leadership had enhanced the participation of staff in pedagogical development. The center directors included organizing teamwork, the responsibilities, and tasks of staff members, and support provided for teacher leadership in the strategy. The strategy was also to encompass regular assignments of reading pedagogical articles and about the ECE curriculum as knowledge of the curriculum was perceived to be somewhat weak among staff. Issues of workplace atmosphere were also to be addressed in the current center culture. In addition to a written strategy, directorial enactments of pedagogical leadership were perceived by the center director to be manifest in everyday discussions and interactions with staff members.

High teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership

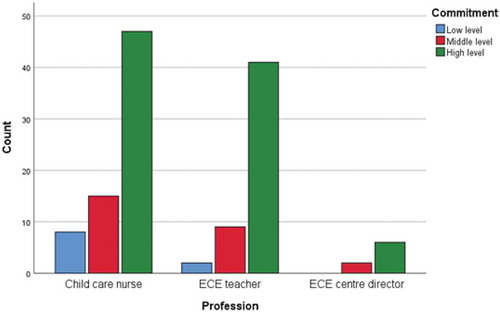

All the studied professional groups evaluated teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership to be mainly high. Cross-table methodology was employed to investigate the connection between the variables of the classification scale.Footnote2 According to the findings, occupation had no statistically significant relationship to how teacher commitment was perceived (χ2 = 3.82, df = 4, p > .05). The majority of each professional group gave the highest level of teacher commitment; ECE teacher guides and encourages educator team towards deep reflection and learning ().

Figure 1. View of commitment by profession. Low level = pedagogical responsibility of the ECE teacher is not manifest in the team; Middle level = the ECE teacher plans and evaluates pedagogy but does not involve other team members in pedagogical planning and evaluation; High level = the ECE teacher guides and encourages the team towards deep reflection and learning

Interview findings indicate that teachers were perceived to encourage pedagogical reflection in their teams in the weekly staff meetings, for example, by providing literature for discussion and documenting shared values and principles in the group, and guiding the pedagogical activities in the child group.

‘ … I think that giving an encouraging example, and not so much that you critically say something to your colleague like “don’t do it like that, but do it like this”, so that I’ve given some examples of what I’ve noticed to work well, so in some situations I might say that “in these situations I do this”’ (Teacher 1.)

The teachers were perceived to take ownership of the general pedagogical development in their child groups and to encourage the participation of child care nurses by inquiring about observations made by the nurses. In addition, teachers were perceived to take responsibility for the overall pedagogical planning.

Despite the findings of high teacher commitment, the center directors also revealed inconsistencies in the abilities of teachers to act as pedagogical leaders. One group of teachers was seen to have adopted a stronger take on consciously leading their teams and individual staff members to improve their work, but there was also a group of teachers whose leadership abilities were perceived by one director to be poor or lacking. Organizing and managing individual duties were seen a key to a coherently functioning team. Confusion and stress were seen to arise in situations where the teacher’s inability to organize teamwork and manage their own duties prevailed in the work culture. In addition, center directors reported of uneven competencies of the teachers’ to embrace new knowledge and accept pedagogical guidance. Teachers’ willingness to improve pedagogy was reported to have assisted in the formation of shared cognitive processes and mutual understanding on the pedagogical vision. ECE center directors considered that teachers who have strong professional identity and interest in developing pedagogical practices were able to foster a culture of pedagogical improvement in their teams. Enactments of teacher leadership were perceived by the directors to manifest in mutual discussions between teachers and other educators, in leading the team, taking responsibility for influencing others’ perceptions and intervening in situations where pedagogical guidance was perceived to be necessary. Teachers were perceived by directors to enact pedagogical leadership in their teams, where teachers enhance progress on pedagogical proceedings and issues.

Not only did the responses of center directors vary but also the way teachers perceived their role in leading their teams. One teacher perceived her main responsibility as producing ideas for the forthcoming pedagogical activities, asking simple questions about how things had progressed, and if there was something that could be done differently. In contrast, another teacher described in-depth teacher responsibilities for enhancing reflection. The teachers, on average, perceived their leadership role to call for active participation in developing the teams and improving together.

The strong relation between distributed pedagogical leadership and teacher commitment

The results indicate that sufficient enactment of distributed pedagogical leadership in ECE centers is connected to higher teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership ().

Table 5. Descriptives of dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership by view of commitment level

Distributed pedagogical leadership and the level of teacher commitment had a statistically significant connection (p < .00-.05), except for the fifth dimension ‘Developing strategy for distributed pedagogical leadership’ (p > .05) ().

Table 6. One-way ANOVA results between groups divided by view of commitment level

The results indicate that those respondents who evaluated teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership as low also rated the distributed pedagogical leadership dimension ‘Enhancing shared consciousness of visions and strategies between the stakeholders’ as insufficiently enacted. In contrast, if the respondent evaluated teacher commitment as high, this dimension was perceived to be implemented accordingly. The difference is not only statistically significant between low teacher commitment and high teacher commitment responses (p < .001) but also between the middle and high teacher commitment responses (p < .01). The same tendency is found in the second leadership dimension ‘Distributing responsibilities for pedagogical leadership. ’ The respondents who perceived an ECE teacher as committed to pedagogical leadership rated the second leadership dimension higher than the respondents who rated commitment to be low. The statistical significance remains in the ANOVA table boundary of .05. Detailed parity comparisons support that observation, meaning that statistically significant results cannot be achieved even though the tendency is very similar to the first leadership dimension.

The differences between the different groups of respondents were clear in the dimension ‘Distributing and clarifying power relationships between the stakeholders,’ (p < .001). If a respondent-perceived teachers as committed to leadership, he/she also rated the dimension to be implemented sufficiently at the center. Statistically clear differences were found not only between the low and high teacher commitment responses (p < .001) but also between the middle and high teacher commitment responses (p < .01).

For the dimension ‘Distributing the enactment of pedagogical improvement within centers,’ the commitment-level groups differs most clearly (p < .001). This research result is clearly outlined in all statistical comparisons between different teacher commitment respondent groups. As the commitment of the ECE teacher increases, the distribution of the pedagogical improvement also increases in the teams. There is a particularly clear difference between the high-level and the low-level teacher commitment responses (p < .001) as well as the middle and high-level teacher commitment responses (p < .001). As clear a difference was not found between the low and the middle commitment responses (p < .05). The levels of teacher commitment responses do not segregate similar to the other leadership dimensions in the ‘Developing strategy for distributed pedagogical leadership’ dimension (p > .05). A fairly clear distinction is made between the middle-level and a high-level teacher commitment responses in this dimension (p = .07). This leadership dimension is considered to be a fairly low level with low and middle teacher commitment. The respondents who evaluated the teacher commitment to be high felt that strategy for distributed pedagogical leadership was developed properly. However, there were no statistically significant differences in parity-based comparisons ().

Table 7. Multiple comparisons of dimensions of distributed leadership divided by view of commitment level (LSD)

The findings of the qualitative study support the quantitative findings presented above. The ECE professionals who perceived enactments of teacher leadership to be sufficient, reported more consistent enactments of the dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership. The teacher who perceived teacher commitment to comprise mainly of handing out ideas and instructions top-down to the child care nurses, also perceived that a pedagogical vision was not wholly shared in the center. Similarly, the teacher, who described in-depth responsibilities of teacher leadership also perceived that the pedagogical vision was shared at their center and that all dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership were enacted sufficiently. ECE directors responded that in the teams where enactments of teacher leadership were perceived to be efficient, the roles and responsibilities of different educator groups were also efficiently organized. At centers where teachers were perceived by directors to be proactive in developing pedagogical proceedings, the teachers were also perceived by directors to have a higher degree of shared values on pedagogical thinking. Likewise, the overall enactments of distributed pedagogical leadership were valued to be insufficient at an ECE center where the director perceived teacher leadership to be lacking or poor, especially in relation to a shared vision and values. In this way, the qualitative analysis supports the results from quantitative analysis, suggesting that sufficient implementation of distributed pedagogical leadership by leaders and center directors is crucial for teachers’ commitment to pedagogical leadership in their staff teams.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the enactment of distributed pedagogical leadership in ECE settings and teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership as perceived by the studied ECE professionals. The results indicated that sufficient enactment of distributed pedagogical leadership at ECE centers was connected to higher ECE teacher commitment to pedagogical leadership. The relationship between distributed pedagogical leadership and teachers’ commitment was found to be reciprocal. Implementing a leadership approach with long-term goal-oriented pedagogical development and information sharing, evidence-based reflection by all staff on concretizing pedagogical terms and phenomenon together as well as well-established leadership structures aid in aligning of pedagogical thinking in centers. Teachers’ skills, attitudes, and interest in the development and the ability to lead a team were statistically shown to be crucial. The results support previous findings (Heikka, Citation2014; Sims et al., Citation2015) about the importance of structures and tools for the efficient enactment of leadership provided by ECE center directors. In addition, this study extends the previous findings by evidencing that the teachers’ abilities and dispositions are significant for their commitment to pedagogical leadership, which is essential when implementing distributed pedagogical leadership in ECE contexts. In addition to shared construction of visions and strategies to be critical in fostering consciousness of pedagogical goals and a work culture based on the core elements of the ECE curriculum, clearly defined responsibilities for pedagogical leadership were found to be distinctive affirmative notes in the responses of all professionals, as has been noted in previous studies (Heikka, Citation2014; Hujala, Heikka, & Halttunen, Citation2017; Waniganayake et al., Citation2017).

Finnish ECE exists in an era of rapid policy and practice development. ECE pedagogy is currently under constant monitoring and development. The Act on Early Childhood Education (540/2018) support ECE practices with additional emphasis on the presence of university qualified ECE teachers in all child groups. The results of this study clearly indicate, that ECE teachers possess the potential to enhance and encourage shared pedagogical visions at ECE centers. Enhancing and encouraging shared pedagogical visions are fundamental elements for the continuous and uniform quality of ECE pedagogy and practices in ECE services across the board. The results of this study can enhance and support ECE teachers and their teams to understand the meaning of distributed leadership and mutual reflection for achieving shared visions and the enactment of meaningful professional learning and development. However, the results indicate the need to strengthen the capabilities of all ECE teachers to take responsibility for pedagogical leadership. This needs to be taken into account in developing teacher preparation in future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Limitations of the method. A parametric method, a variance analysis, was used to compare different professions. The distribution of the examined variables is visually symmetrical, but according to the normality test (Kolmogorov–Smirnov) the distributions differ from the normal distribution. However, it should be remembered that statistical tests reveal the slightest differences statistically significant (especially in large data). In this data, one group is also relatively small, i.e., center directors (n = 8). To ensure contentious results, analyzes were also carried out with the nonparametric counterpart of the variance analysis, Kruskal-Wallis. Its results are in substance and in the light of statistical indicators, essentially the same as the results of the analysis of variance.

2. Cross-table is an nonparametric method and is particularly well suited for situations where the connection between two (or one) categorical variables is studied. The number of frequencies expected in this study is not quite sufficient, so conclusions on the results must be taken with caution. However, based on qualitative analysis, the interview findings support the view of high enactments of teacher pedagogical leadership.

References

- Act 540/2018. Varhaiskasvatuslaki. [ Act on Early Childhood Education]. Retrieved from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2018/20180540

- Act 680/1998. Perusopetuslaki [ Basic Education Act]. Retrieved from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/1998/19980628

- Alila, K., Eskelinen, M., Estola, E., Kahiluoto, T., Kinos, J., Pekuri, H.-M., … Lamberg, K. (2014). Varhaiskasvatuksen historia, nykytila ja kehittämisen suuntalinjat. Tausta-aineisto varhaiskasvatusta koskevaa lainsäädäntöä valmistelevan työryhmän tueksi. Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriön työryhmämuistioita ja selvityksiä 2014: 12.[ The history, presence and the directions for the development. Survey for the early childhood education act working committee. Ministry of Education and Culture memorandums and surveys 2014:12]. Retrieved from http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-263-266-1

- Aubrey, C. (2016). Leadership in early childhood. In D. Couchenour & J. Kent Chrisman (Eds.), The sage encyclopedia of contemporary early childhood education (pp. 808‒810). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Boe, M., & Hognestad, K. (2017). Directing and facilitating distributed pedagogical leadership: Best practices in early childhood education. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(2), 133‒148.

- Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Brookfield, S. D. (2009). The concept of critical reflection: Promises and contradictions. European Journal of Social Work, 12(3), 293‒304.

- Colmer, K., Waniganayake, M., & Field, L. (2015). Implementing curriculum reform: Insights on how Australian early childhood directors view professional development and learning. Professional Development in Education -Special Issue: the Professional Development of Early Years Educators, 41(2), 203‒221.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (Third ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- EDUFI. (2014). Core curriculum for pre-primary education. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

- EDUFI. (2018). National core curriculum for early childhood education and care. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

- Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274.

- Gronn, P. (2008). The future of distributed leadership. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(2), 141‒158.

- Gronn, P. (2009). Leadership configurations. Leadership, 5(3), 381‒394.

- Gronn, P. (2011). Hybrid configurations of leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The sage handbook of leadership (pp. 437‒454). London: Sage.

- Guest, G. (2013). Describing mixed methods research: An alternative to typologies. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 7(2), 141‒151.

- Halttunen, L. (2009). Päivähoitotyö ja johtajuus hajautetussa organisaatiossa [ Day Care work and leadership in a distributed organization] (Doctoral dissertation). Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä. Retrieved from https://jyx.jyu.fi/dspace/bitstream/handle/123456789/22480/9789513937621.pdf

- Harris, A. (2003). Teacher leadership as distributed leadership: Heresy, fantasy or possibility. School Leadership & Management, 23(3), 313‒324.

- Heikka, J. (2014). Distributed pedagogical leadership in early childhood education (Doctoral dissertation). Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1392. University of Tampere, Tampere University Press, Tampere.

- Heikka, J., Halttunen, L., & Waniganayake, M. (2016). Investigating teacher leadership in ECE centres in Finland. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 5(2), 289‒309.

- Heikka, J., Halttunen, L., & Waniganayake, M. (2018). Perceptions of early childhood education professionals on teacher leadership in Finland. Early Child Development and Care, 188(2), 143‒156.

- Heikka, J., & Hujala, E. (2013). Early childhood leadership through the lens of distributed leadership. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 21(4), 568‒580.

- Heikka, J., Waniganayake, M., & Hujala, E. (2013). Contextualizing distributed leadership within early childhood education: Current understandings, research evidence and future challenges. Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 41(4), 30‒44.

- Hirsjärvi, S., & Hurme, H. (2010). Tutkimushaastattelu: Teemahaastattelun teoria ja käytäntö [ Research interview: Theory and practise of the theme interview]. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

- Ho, D. C. W. (2011). Identifying leadership roles for quality in early childhood education programmes. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 14(1), 47‒57.

- Ho, D. C. W., & Tikly, L. P. (2012). Conceptualizing teacher leadership in a Chinese, policy-driven context: A research agenda. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 23(4), 401–416.

- Hognestad, K., & Boe, M. (2014). Knowledge development through hybrid leadership practices. Nordisk Barnehageforskning, 8(6), 1‒14.

- Hognestad, K., & Boe, M. (2015). Leading site-based knowledge development: A mission impossible? Insights from a study from Norway. In M. Waniganayake, J. Rodd, & L. Gibbs (Eds.), Thinking and learning about leadership. Early childhood research from Australia, Finland and Norway (pp. 210‒228). NSW: CCCNSW.

- Hujala, E., Heikka, J., & Halttunen, L. (2017). Johtajuus varhaiskasvatuksessa [Leadership in early childhood education]. In E. Hujala & L. Turja Eds., Varhaiskasvatuksen käsikirja (pp. 287‒299). Jyväskylä: PS-kustannus.

- Li, Y. L. (2015). The culture of teacher leadership: A survey of teachers’ views in Hong Kong early childhood settings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43(5), 435–445.

- Lund, T. (2012). Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: Some arguments for mixed methods research. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(2), 155‒165.

- Male, T., & Palaiologou, I. (2017). Pedagogical leadership in action: Two case studies in English schools. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(6), 733‒748.

- Peterson, T., Veisson, M., Hujala, E., Härkönen, U., Sandberg, A., Johansson, I., & Kovacsne Bakosi, E. (2016). Professionalism of preschool teachers in Estonia, Finland, Sweden and Hungary. European Early Childhood Research Journal, 24(1), 136‒156.

- Rosemary, C. A., & Puroila, A.-M. (2002). Leadership potential in day care settings: Using dual analytical methods to explore directors’ work in Finland and the USA. In V. Nivala & E. Hujala (Eds.), Leadership in early childhood education. Cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 49‒64). Oulu: Oulu University Press. Retrieved from http://jultika.oulu.fi/files/isbn9514268539.pdf#page=51

- Sims, M., Forrest, R., Semann, A., & Slattery, C. (2015). Conceptions of early childhood leadership: Driving new professionalism? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 18(2), 149‒166.

- Spillane, J. P. (2006). Distributed leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Spillane, J. P., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. B. (2001). Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educational Researcher, 30(3), 23–28.

- Tuomi, J., & Sarajärvi, A. (2018). Laadullinen tutkimus ja sisällönanalyysi [ Qualitative research and content analysis]. Helsinki: Tammi.

- Wang, M., & Ho, D. (2018). Making sense of teacher leadership in early childhood education in China. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/13603124.2018.1529821

- Waniganayake, M., Cheeseman, S., Fenech, M., Hadley, F., & Shepherd, W. (2017). Leadership: Contexts and complexities in early childhood education (2nd ed.). South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Waniganayake, M., Heikka, J., & Halttunen, L. 2018. Enacting pedagogical leadership within small teams in early childhood settings in Finland – Reflections on system-wide considerations. In S. Cheeseman & R. Walker Eds.. Volume 1 in the series on Thinking about pedagogy in early education: Pedagogies for leading practice (pp. 147–164). A. Fleet & M. Reed (series editors). Oxon: Routledge.

- Waniganayake, M., Rodd, J., & Gibbs, L. (Eds.). (2015). Thinking and learning about leadership: Early childhood research from Australia, Finland and Norway. Sydney: Community Child Care Cooperative NSW.

- York-Barr, J., & Duke, K. (2004). What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from two decades of scholarships. Review of Educational Research, 74(3), 255‒316.