?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to examine leadership for learning practices across the world by establishing profiles of leadership at school and country levels. Consequently, the study brings to our attention the (ir)relevance of school and system features for leadership for learning. The paper contributes to the field through the use of an extensive exploratory approach across a varied set of school leadership measures collected from both teachers and principals and contextualized in 42 different educational systems participating in the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018. Consequently, this work has the potential to generate hypotheses regarding the understanding of the complex nature of school leadership worldwide. Surprisingly, the findings reveal that clusters at the country level primarily do not reflect countries with geographical, linguistic, or political proximity. Such clusters were expected, given the evidence found in the literature that shows leadership to largely be determined by contextual, societal, and cultural values. Nevertheless, the analysis identifies five profiles of leadership across schools, the majority of which can be found in most countries participating in TALIS.

Introduction

Most of the studies in the area of school leadership are conducted within individual educational systems or larger geographical areas that are characterized by some shared features (e.g. Asia, U.S.), resulting in only a few international comparative studies in this field (Herborn et al., Citation2017; Mango, Citation2018). This likely indicates that school leadership differs as a function of cultural dimensions and other contextual features (Brewer et al., Citation2020; Hallinger, Citation2018; Jacobson & Johnson, Citation2011; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], Citation2016). The claim that leadership practices are embedded in culturally sensitive values and worldviews is also supported by findings from other disciplines that are concerned with leadership, such as management as well as occupational and organizational psychology (House et al., Citation2004).

Sensitivity to how school leadership is culturally embedded and contextually dependent is crucial in order to improve teaching and learning in schools (Knapp et al., Citation2014; Slater & Teddlie, Citation1992). Successful leadership, in practice, frequently implies the integration of different leadership styles (Boyce & Bowers, Citation2018; Leithwood et al., Citation2008; Marks & Printy, Citation2003). Thus, leadership theories and models have been developing and adjusting to societal changes (Crow, Citation2006), consequently blurring clear boundaries between previously well-established leadership models (Brauckmann & Pashiardis, Citation2011). The relevant example referred to in this paper is the recent Leadership for Learning model, which integrates several precedent leadership frameworks – instructional leadership, transformational leadership, and distributed leadership (Hallinger, Citation2011; Murphy et al., Citation2007). The model is focused on learning at all levels and describes eight dimensions that encompass not only instruction and assessment but also organizational culture and social advocacy (Daniëls et al., Citation2019).

On the one hand, much of school leadership research focuses on associations between school leadership and other characteristics of schools (Krüger et al., Citation2007), teachers and classrooms (Boyce & Bowers, Citation2018; Printy, Citation2008; Tan et al., Citation2020), or students (Leithwood et al., Citation2010; Robinson et al., Citation2008). On the other hand, a person-centered approach to leadership is rarely employed. For instance, Urick and Bowers (Citation2014) examined different types of principals but only in the U.S. context. In addition, pioneering work on leadership typologies around the world using TALIS data has recently been conducted, where at least three different profiles were identified at school and teacher levels through latent class analysis (Bowers, Citation2020).

The present study aims to provide a descriptive summary of leadership for learning measures that originate from both teachers and principals, scrutinizing them jointly in a single analysis. Accordingly, we recognize that leadership for learning is achieved through joint endeavors of various school stakeholders, mainly teachers and principals. We first employ a series of descriptive/exploratory analyses in order to assess whether the data at the country level are appropriate for subsequent analytical steps. Since the variation at the country level is found to be rather low, applying to only four variables, we focus our analysis on the school level. To identify groups of schools with unique leadership profiles, we employ K-means clustering (Everitt et al., Citation2011). Thus, we identify school characteristics that account for similarities/differences between clusters. By identifying clusters of schools (patterns of similarity within clusters and patterns of dissimilarity across clusters) that are summarized at the country level (percentages of schools belonging to the same cluster within a country), the presented analysis describes the unique and robust features of leadership at the system level. Seen together, inferences at the country level enable us to examine the heterogeneity of leadership practices across educational systems.

To properly account for a holistic Leadership for Learning model, this study uses data collected from the teachers and principals who participated in the most recent cycle of the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS 2018). Similar studies that take a global comparative perspective on educational leadership are still limited, and our results will help improve understanding of how teachers and principals report about the broader characteristics of practices in schools. Moreover, these practices are reasonably assumed to reflect various theoretical dimensions of the Leadership for Learning framework. As such, our work aims to provide a basis for generating more targeted hypotheses for future research answering the following research questions:

To what extent can countries across the world be classified into groups based on leadership for learning practice as reported by teachers and principals?

To what extent can schools across the world be classified into groups based on leadership for learning practice as reported by teachers and principals?

How is group membership of schools associated to demographic characteristics of schools and principals?

Theoretical background

From instructional leadership to leadership for learning

Improving school leadership by focusing on learning, monitoring teaching, building safe and effective learning environments, supporting teacher collaboration, acquiring and allocating resources, has been a promising approach employed in the overarching endeavor to improve education in general (Blitz & Modeste, Citation2015). Improving school leadership imposes tremendous demands on school leaders, further resulting in leadership practices in which functions and responsibilities are, to a large extent, distributed within (school management teams, teachers) and outside (collaboration with other schools and local community) of schools (Pont et al., Citation2008). Historically, the model of instructional leadership was considered to be of great significance for the improvement of teaching and learning for all by relating leadership to the larger educational agenda (Hallinger, Citation2005, Citation2009; Robinson et al., Citation2008). A core feature of instructional leadership has been the improvement of instruction and learning through the principal’s direct engagement (Bossert et al., Citation1982; Hallinger & Murphy, Citation1985). Instructional leadership frameworks first emerged in the USA in the 1950s and has been a dominant construct of leadership grounded in practice (Hallinger, Citation2015). Principals were widely invited to become instructional leaders, which implied not only directly engaging with instruction as implemented in the classrooms, but also a focus on managerial, human resources, political, and institutional functions. This is frequently perceived as an unattainable ideal. Thus, this form of leadership had less and less sense and support in practice (Leithwood et al., Citation2012) and attention gradually shifted toward a shared instructional leadership perspective (Harris, Citation2004; Marks & Printy, Citation2003). Such perspectives were brought to the foreground by leadership frameworks such as distributed leadership (Gronn, Citation2002; Harris, Citation2009; Spillane et al., Citation2004) and transformational leadership (Day et al., Citation2016; Hallinger, Citation2003; Leithwood & Jantzi, Citation2006).

Leadership for learning frameworks appeared in the literature in the early 2000s. One group of authors, mainly coming from the U.S., used this term as a synonym for instructional leadership with some more detailed and broader description of what leadership practice entails while still keeping school improvement and effectiveness as a central objective (Hallinger, Citation2009; Murphy et al., Citation2007). Another group of authors, mainly from the UK, developed a leadership for learning framework characterized by different underlying assumptions and objectives (MacBeath, Citation2019), In common with instructional leadership this framework maintained a focus on learning, yet through a more collaborative perspective taking into account a wider range of leadership sources and broadening learning as something not only including the students, but the school as a whole (Townsend, Citation2019). Both conceptualizations of leadership were central in educational reforms that took place worldwide in the early 2000s with an increased emphasis on accountability. MacBeath (Citation2019) emphasizes the importance of terminology by explaining that ‘instruction’ place teacher, parent, or authority figure at the central stage, while ‘learning’ puts an emphasis on what learners do and how learning is made manifest. Thus, learning and leading are understood more as activities and not as roles, in which emotional and human aspects are emphasized. Thus, leadership for learning compared to instructional leadership emphasizes 1) capacity building of teachers and staff, 2) greater reliance on multiple forms of teacher leadership and teacher collaboration, as well as 3) more attention to school as a learning organization for all, not only students. Leadership for learning is more responsive to students, embraces a moral purpose of education, connects with agents outside of school, and neglects hierarchy (Dempster, Citation2019; Imig et al., Citation2019).

An operationalization of Leadership for Learning has been even more challenging and scholars did not agree on a single model to date. Following Bowers (Citation2020), we acknowledge various attempts to describe leadership for learning domains that are, to a great extent, congruent with one another but differ in how broadly they capture leadership practices (Boyce & Bowers, Citation2018; Hallinger, Citation2011; Halverson et al., Citation2014; Murphy et al., Citation2007). The first such attempt was a model described by Murphy (Citation2007), followed by subsequent models that share the same fundamental concepts. As a result, in this study, we focus on the model proposed by Murphy et al. (Citation2007).

This model consists of eight major leadership for learning dimensions, which are further defined by several domains. These dimensions are: vision for learning, instructional program, curricular program, assessment program, communities of learning, resource acquisition and usage, organizational culture, and social advocacy (Murphy et al., Citation2007). Vision for learning implies that a great deal of time is dedicated to the development, articulation, implementation, and stewardship of ambitious goals that are focused on learning and achievement and are easily interpretable and measurable. Instructional program refers to the involvement in instruction and teaching, staff support, and protection of instructional time. By establishing high standards and expectations and by coordinating curriculum materials and assessments, the curricular program dimension is covered. Similarly, the assessment program dimension is covered through the crafting, implementing, and monitoring of assessments at classroom and school levels. Professional development, a culture of collaboration, and fairness are emphasized through the learning communities dimension. The resource acquisition and usage dimension is oriented toward locating and securing additional resources for schools from the broader school community using both formal and informal channels. Resource deployment and use should clearly be linked to school mission and goals. Continuous focus on school development and on a safe and orderly learning environment, as well as an emphasis on personal and group achievements and recognition, are features of the organizational culture dimension. Finally, the social advocacy dimension covers four domains – environmental context, diversity, ethics, and stakeholder involvement. The presented model is nicely described by MacBeath and Townsend (Citation2011), who state that leadership for learning embraces much more than the improvement of student learning outcomes only – but that it is also concerned with teacher and leadership learning, creating a climate of creativity and growth by drawing attention to the dynamic connections, relationships, and mutual influences that shape both learning and teaching.

School leadership in the TALIS 2018 study

School leadership remains a top priority, according to the country ratings of the themes for inclusion in the TALIS 2018 study. The increasing interest in school leadership is recognized by the TALIS 2018 study, where richer measures for school environment can be found in both the school and teacher questionnaires (Ainley & Carstens, Citation2018). Since the first study, which was conducted in 2008, the thematic coverage of the subsequent TALIS surveys has changed in order to also reflect the recent trends and innovations in research on school leadership. As previously discussed, school leadership research has shifted its focus toward more distributed practices, involving stakeholders across all levels of the educational system. TALIS acknowledges the developments in the field by keeping the principal as a central character but also including a more collaborative perspective on leadership (Ainley & Carstens, Citation2018). Consequently, in addition to instructional leadership, which remains a main interest, two additional leadership conceptualizations are discussed in the TALIS 2018 conceptual framework: teacher leadership, where teachers take on leadership roles both within and outside of the classroom (Muijs & Harris, Citation2003), and system leadership, where principals take on leadership roles outside of the school. The latter brings the importance of the relation with the broader community to our attention (Ainley & Carstens, Citation2018; Schley & Schratz, Citation2011).

School leadership, as described by the TALIS 2018 conceptual framework, nicely encompasses all three important features of leadership for learning: the principal remains the central character (instructional leadership), the perspective on leadership is more collaborative and distributed (distributed leadership), and the broader social and system features are accounted for (system leadership).

The actual scales available in TALIS 2018 questionnaires, which directly deal with leadership, are the scales of school leadership and participation among stakeholders from the principal questionnaire and participation among stakeholders from the teacher questionnaire. However, other scales that are not exclusively described as school leadership scales can also be used to describe the school environment and the working conditions that are closely related to leadership for learning (e.g. academic pressure, team innovativeness, stakeholder involvement, and more). Conceptual mapping of the Leadership for Learning theory and the TALIS 2018 items from both teacher and principal questionnaires was performed by Bowers in a working paper about leadership typologies using the same data (Bowers, Citation2020).

provides a broad conceptual map of how the TALIS 2018 scales correspond with the dimensions of the Leadership for Learning framework. The left-hand side of the table lists the eight theoretically-defined dimensions from the Leadership for Learning framework, while the right-hand side identifies the TALIS 2018 scales that partly reflect certain aspects of these dimensions. It should be noted that some scales from the TALIS 2018 study are identified as reflecting more than one theoretical dimension and that one of the dimensions in the theoretical framework does not have a corresponding scale in the empirical data. Hence, provides a condensed picture of how TALIS 2018 represents a broad and coarse-grained operationalization of the core features of the Leadership for Learning framework. However, the table also serves to illustrate the fact that the match between the Leadership for Learning theory and TALIS is only a partial one. Accordingly, TALIS is a rather blunt – but nevertheless useful – instrument that can be used to map out the characteristics of school practices that reasonably reflect the Leadership for Learning framework.

Table 1. Conceptual mapping of the Leadership for Learning framework and TALIS 2018 scales

National and school contexts and their relevance for school leadership

It is likely not very useful to conceptualize school leadership as a universal phenomenon, independent of school context, educational policy, culture, national history, and values. Although weakly supported in the quantitative literature, the argument about the importance of cultural and national contexts for school leadership practices is widely accepted among practitioners and scholars (Clarke & O’Donoghue, Citation2016; Harris, Citation2020; Johnson et al., Citation2008). This claim is further supported by examples from practice in which, for instance, successful leaders in one environment did not necessarily succeed as leaders in another (Miller, Citation2018). Finally, research describes cases that illustrate how attempts to transfer educational policies for school governance and leadership from one educational system to another were unsuccessful (Harris, Citation2020; Hooge, Citation2020; Oplatka & Arar, Citation2017). Studies on how divergent national educational policies directly shape school leadership practices provide further evidence of cross-cultural differences (Hooge, Citation2020; Miller, Citation2018). Møller and Schratz (Citation2009) expand the argument further to the socio-cultural, historical, and political contexts by discussing the differences, similarities, and conditions in four different regions – England, Scandinavia, German-speaking countries, and Eastern European countries. They conclude that leadership is culturally embedded and socially constructed and that the difference is even greater when countries do not share linguistic and common cultural heritage. However, empirical evidence about the importance of system features for leadership practices is still limited. Therefore, the current study applies quantitative analysis to system-level representative data in order to answer what has, over the years, primarily been supported by evidence from case studies and literature reviews.

Moreover, strong evidence exists for the importance of culture for leadership practice at the micro (school) level. Values, norms and traditions that shape organizational culture within schools are found to be strongly associated with school leadership practice (DuPont, Citation2009; Hallinger & Leithwood, Citation1998; Kalkan et al., Citation2020; Karada & Öztekin, Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2021; Sahin, Citation2011). Together with the concept of school climate which refers to shared perceptions and behaviors (Ashforth, Citation1985; Hoy, Citation1990; Wang & Degol, Citation2016), school culture might be one of the closest and tightly related factors that could explain possible variation in leadership practice across schools. When it comes to specific school contexts – such as school and principal demographic variables – the literature is generally inconsistent (Hallinger, Citation2005, Citation2008; Opdenakker & Damme, Citation2007). In a review paper on this matter, with a focus on instructional leadership, Hallinger (Citation2008) concluded that school size, school performance rating, private schools, and level of the principal did not significantly account for differences in approaches to leadership, while gender and the number of years of experience of the principal were more frequently found to be significantly related to how instructional leadership is implemented. We were unable to identify similar studies that specifically refer to leadership for learning and therefore we examine to what extent 1) school demographics (such as school size, location, private/public, and number of students whose first language differs from the language of instruction) and 2) principal demographics (such as gender) are relevant for leadership.

Partially, the current study also responds to the criticism that much of the theoretical work on school leadership is derived from Western countries, predominantly from the U.S. This criticism calls for more studies to incorporate varied and globally relevant cultural, institutional, and economic settings (Hallinger, Citation2018; Oplatka & Arar, Citation2017; Walker & Dimmock, Citation2002). for learning practices.

Methods

Data and sample

This study used data from the third and currently last cycle of the TALIS study – the TALIS 2018 survey. TALIS is an international, large-scale survey that is concerned with teaching and learning conditions, learning environments, school leadership, and more (Ainley & Carstens, Citation2018). In TALIS 2018, 48 countries and economies took part in the core survey – that is, teachers and principals from the lower secondary level of education (ISCED Level 2).Footnote1 TALIS applied a two-stage sampling design. Within a country, a random sample of 200 schools was identified and invited to participate in the study during the first stage, followed by drawing a random sample of 20 teachers from each of the selected schools. More details about the sampling design and outcomes can be found in the TALIS technical report (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], Citation2018).

The total sample in this study included 7,427 schools from 43 countries.Footnote2 Six countries were excluded from the analysis due to a large amount of systematically missing data (10.25% of the total sample). provides an overview of the excluded countries as well as the reasons for their exclusion. For the remaining sample, listwise deletion was utilized. The effect of the listwise deletion varied between countries (from 0.68% to 35.94%) with an average of 11.86% of missing data per country.Footnote3 A large portion of missing data resulted from all data missing for the school level (17.94% of data missing from the total data after county exclusion) or all data missing for the teacher level (20.72% of data missing from the total data after country exclusion).

Table 2. Countries excluded due to missing data

Measures

Six scales from the principal questionnaire and six scales from the teacher questionnaire were used in the analysis (see ). The scales represent the factor scores calculated in the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) framework and already available as part of the TALIS database (OECD, Citation2018). TALIS conducted two types of CFA: 1) joint analysis of data from all participating countries and 2) separate analyses for each country’s economy. The final scale modeling accounted for invariance levels across countries and ISCED levels. Hence, the final scales were modeled using the multigroup CFA (MGCFA) framework from which factor scores are obtained.

Table 3. TALIS 2018 list of scales used in the analysis

One of the scales originating from the principal questionnaire, Instructional autonomy in schools, is not included in the publicly available dataset. We derived this scale for the purpose of this study, by following procedures very similar to how are the other scales in TALIS produced. A set of six items for which principals responded in relation to the question of who has a significant responsibility for the following tasks: choosing which learning materials are used, deciding which courses are offered, determining the course content, approving students for admission to the school, establishing student assessment policies, and establishing student disciplinary policies. These items were first recoded into an ordinal scale with three levels: full autonomy (if internal evaluators, such as the principal, other members of the school management team, teachers, or the school governing board, were checked), mixed autonomy (if both internal and external evaluators are checked), and no autonomy (if only external evaluators were checked). Then, these six variables with three levels were used to calculate the unique factor score that represents the school autonomy for instructional practices variable.Footnote4

The final school file consisted of scores for twelve scales originating from both the principal and teacher questionnaires. Prior to the cluster analysis, all scales were standardized with an international mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, using so-called senate weights to ensure that all countries contribute equally. Subsequently, teacher variables were aggregated to the school level. As shown in the last column in , the scales used in this analysis achieved a different level of measurement invariance. Measurement invariance (MI) refers to the property that an instrument should function equally across a range of conditions regarded to be irrelevant to the attribute being measured (e.g. language, culture, item understanding) (Millsap, Citation2012). If this condition is not satisfied, then there is no sound basis for a comparison of (latent) mean scores across groups. Establishing the MI across such a large number of groups has been challenging and, as some authors argue, may represent an unrealistic goal (Byrne & Vijver, Citation2010; Lubke & Muthén, Citation2004; Rutkowski & Svetina, Citation2014; Zieger et al., Citation2019). In the present study, we did not explicitly compare scales at the country level but, instead, the profiles of leadership for learning at the school level, which constitute a mitigating factor for the inclusion of scales that achieve a different MI level. Although we examined more than 40 educational systems, we also acknowledge the potential shortcomings that could result from scales that only achieve a configural level of invariance.

Statistical analysis

Data were first prepared using the IDB Analyzer 4.0, while the main analyses were conducted using the R studio (R Core Team, Citation2018; IMB Corp, Citation2017). The R package cluster (Maechler et al., Citation2019) was used for the cluster analyses, while the package factoextra was applied to extracting and visualizing the results (Kassambara & Mundt, Citation2020). Cluster analysis was regarded to be an appropriate method to use here, given the nature of the problem and the data. Furthermore, the fact that no prior hypothesis about the number and nature of the expected clusters could be reasonably stated suggested that a descriptive and exploratory approach is reasonable. Cluster analysis is a common label attached to a group of statistical techniques and it enables similar observations found in a dataset to be classified or grouped together. Simply stated, objects in the same cluster are similar to one other in relation to a set of characteristics, while objects in different clusters are dissimilar in terms of the same set of characteristics (Everitt et al., Citation2011). The starting point of cluster analysis is the calculation of a proximity/dissimilarity matrix, consisting of measures identifying the degree of similarity between objects. The choice of the proximity measure depends on the nature and scale of the data (Everitt et al., Citation2011). In this study, we wanted to identify clusters of schools with similar profiles across a set of leadership for learning characteristics. Accordingly, the Pearson correlation coefficient would be a proximity measure of choice. However, when data are standardized the results obtained from two proximity measures (Pearson correlation and Euclidian distance) are comparable. Thus, we used Euclidian distance as default measure with k-means (Kassambara, Citation2017). The procedure of clustering was similar to factor analysis but with two main differences: 1) cluster analysis groups objects based on the proximity of pairs or larger groups of objects (in our case, schools), while 2) factor analysis groups variables based on patterns of variations. Specifically, we used k-means clustering. In k-means clustering, each cluster is represented by its center (i.e. centroid), which corresponds to the mean profile of the objects assigned to the cluster. The main idea is that the total intra-cluster variation is minimized. This method clusters given data into a set of k groups, where k is the number of groups pre-specified by a researcher. Since we had no prior hypothesis about the number of clusters, the optimal number was selected based on 1) the elbow method that utilizes the total within-cluster sum of squares variation as a function of the number of clusters and on 2) the silhouette method that computes the average silhouette coefficient (sometimes referred to as silhouette width) for different values of k (Kassambara, Citation2017). In addition, a silhouette coefficient was used to validate the clustering solution – i.e. how well each object (in our case, school) is classified to the belonging cluster. Hence, each school was assigned a value that is referred to as the silhouette coefficient (Si).Footnote5 A silhouette coefficient can take a value from – 1 to 1. A silhouette coefficient near 1 indicates that observation is well clustered in the belonging cluster and is far away from other clusters. A negative silhouette coefficient might indicate that observation is also proximal to other clusters, and as such negative values identify objects which are not that well captured by the clustering solution. In evaluating the number of clusters, an optimum is found for the number of clusters resulting in the lowest average silhouette coefficient.

Results

Descriptive statistics

As a first step, we inspected the descriptive statistics for the variables included in the analysis. We ran unconditional three-level (teacher data) and two-level (principal data) models in order to scrutinize variance decomposition across levels – teachers in schools in countries (Snijders & Bosker, Citation1999). The intra-class correlation coefficients from the unconditional models for each variable are presented in . Given that the primary concern of this analysis, as stated in RQ1, was to explore phenomena that represent features of schools across countries, the expectation was that a meaningful variability in the data can be accounted for by countries. However, at the country level, only a few variables (school autonomy for instructional practices, effective professional development, team innovativeness, school leadership) showed significant and substantially meaningful variability across countries. However, a significant and substantially meaningful amount of variability was found for most teacher variables at the school level. This finding suggests that most of the variability in the variables of interest lies between schools rather than between countries. Consequently, the originally intended country-level cluster analysis was dropped. Instead, cluster analysis was conducted with schools as primary units.

Table 4. Variance decomposition at teacher, school, and country levels presented by intraclass correlations (ICC)

visualizes and presents additional details about the (lack of) variability between countries through box-plots that describe the dispersion in the country mean scores for all variables. The relatively large intraclass correlations (ICCs) for the ‘T3TEAM’ (Team innovativeness) and ‘AUTONOMY’ (Instructional autonomy in schools) variables are indicated by wide boxes (representing the values for the 25th and 75th percentiles). It is interesting to note that the high ICC for the ‘T3EFFPD’ (Effective professional development) variable relates to dispersion, where only a few countries have either extremely low or high scores. The box-plot also shows that the Organizational innovativeness (‘T3PORGIN’) and Participation among stakeholders, principals (‘T3PLEADP’) variables have close to zero variability at the country level, which is reassuring, given the fact that null models did not converge for these variables.

K-means clustering of schools: the five cluster solution

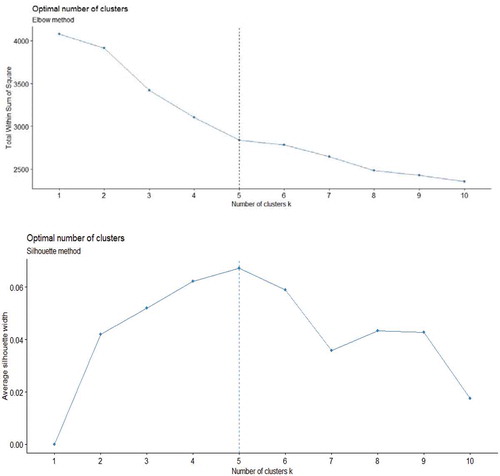

All variables from are used as indicators of leadership for learning at the school level. First, in order to determine the optimal number of clusters, we used the Elbow method and the Silhouette method, which are illustrated in . Both approaches suggested five clusters to be the optimal solution. The aim was to establish clusters that are distinct but also meaningful and interpretable. A manageable number of reasonably-sized clusters was also considered to be an advantage.

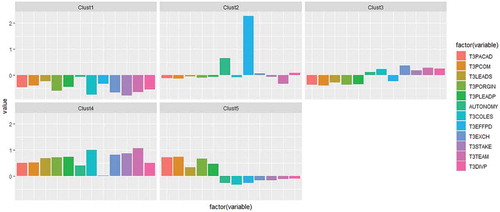

In response to the second RQ, we established five different leaderships for learning profiles across schools in 43 educational systems. presents the average values for each of the variables included in the analysis for each of the five clusters. In the following, we refer to these figures as cluster profiles. A first observation is that Cluster 1 and Cluster 4 have profiles that largely go in opposite directions. Cluster 1 is characterized by moderately low values for all variables, except for the school autonomy for instructional practices variable, while Cluster 4 has moderately high values for almost all variables, except for the professional collaboration in lessons among teachers variable. Cluster 3 and 5 profiles also represent mirror images. Cluster 3 is characterized by moderately low negative values for almost all variables reported by principals and by low positive values for most of the measures based on teacher reports. This is also the largest cluster, accommodating 28% of all schools in the sample. In contrast, Cluster 5 has moderately positive values for variables reported by principals and negative or neutral values for variables reported by teachers. It is interesting to note that in both Cluster 3 and Cluster 5, the reports about distributed leadership practice (i.e. participation among stakeholders) differ between teachers and principals. In cluster 3, principals reported lower distributed leadership (‘T3PLEADP’) while teachers at the same time reported somewhat higher distributed leadership (‘T3STAKE’). The opposite holds for Cluster 5. Thus, a potential gap in how leadership practice is perceived exists between teachers and principals. Note also that the school autonomy for instructional practices variable, reported by principals, moves together with the variables reported by teachers. Cluster 2 has a unique profile characterized by high values for the effective professional development and higher school autonomy for instructional practices variables. This cluster is the smallest in size, comprising 11% of all schools from the sample.

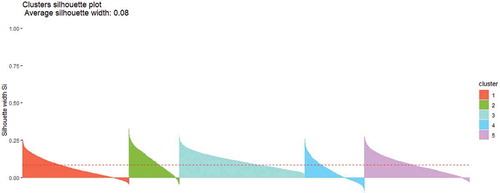

Cluster validation

shows the silhouette coefficients (silhouette widths) for each school as bars stacked next to one another, sorted from the school with the highest width to the left, for each of the five clusters, respectively. The red dotted line represents the average silhouette coefficient across the entire sample. Inspecting reveals that none of the schools in Cluster 3, the largest cluster, have negative widths. In total, 790 schools of the entire 7,427-school sample were identified with negative silhouette coefficients – 15% of the 1,769 schools in Cluster 1, 7% of the 833 schools in Cluster 2, 33% of the 993 schools in Cluster 4, and 7% of the 1,744 schools in Cluster 5. Across countries, NOR had the most schools with a negative silhouette coefficient, amounting to 19% of all its schools, followed by AUT, SAU, GEO, and LVA (see Appendix A for complete list and definitions of the abbreviations presented here) with more than 15% of schools having uncertain cluster membership. In both absolute and relative numbers, most of the uncertainties in classifications relate to Clusters 4 (all high) and 1 (all low). Although the five-clusters solution does not provide a perfect representation of the schools’ leadership profiles, the vast majority of schools can reasonably well be categorized into one of the five suggested clusters. The clustering accounts for 25.9% of the variability in school profiles. For further analyses, we excluded schools with negative silhouette coefficients. By doing this, we purified clusters and relied on well-clustered schools that represent typical schools that belong to specific clusters. In conclusion, even when such classification does not work as an informative diagnostic for every single school, the presented cluster solution provides a useful birds-eye view of school leadership practices across the countries that participate in TALIS. Again, it should be of interest to note that the variability in leadership practices, as reported by principals and teachers, is much larger within than it is across countries.

Dominant clusters within countries

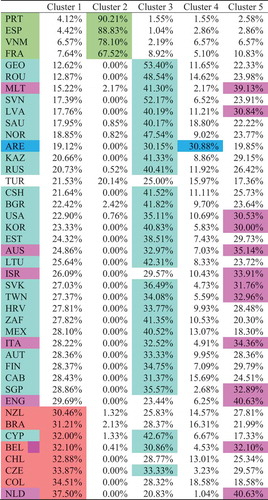

Although we were unable to directly explore clusters of countries based on leadership for learning practice due to low variability at the country level, in response to RQ1 we provided the frequencies of clusters established at the school level within each country (see Appendix B). represents a list of countries in which more than 30%Footnote6 of schools belong to respective clusters. Countries listed in italic font have more than 30% their schools in more than one cluster and, therefore, appear in more than one column.

Table 5. List of countries with more than 30% of schools in respective clusters

Note that the majority of countries have more than 30% of their schools in Cluster 3, which is the largest cluster. It is interesting to note that countries with more than 30% of schools in at least two clusters are primarily found in two contrasting clusters – Cluster 3 (low on principal, high on teacher variables) and Cluster 5 (high on principal, low on teacher variables) and these are AUS, ISR, ITA, MLT, LVA, USA, KOR, SVK, TWN, SGP, and BEL (see Appendix A for complete list and definitions of the abbreviations presented here). Some countries, such as PRT, ESP, VNM, and FRA, have the majority of their schools (more than 65%Footnote7) in Cluster 2, while GEO and SVN have more than 50% in Cluster 3. For these countries, we can say that leadership for learning practices are more homogeneous. In contrast, countries such as TUR, BEL, and MLT do not have a dominant leadership profile, meaning that leadership practices are more heterogeneous within these countries. Note that countries with a similar distribution of schools across clusters do not indicate countries that could easily be classified as representing geographically, linguistically, or politically proximal countries, with the possible exception of the four countries in which the majority of schools belong to Cluster 2.

Cluster composition

In order to describe schools within clusters and respond to our third RQ, we examined descriptive statistics regarding school background characteristics, including public vs. private schools, schools in urban vs. rural communities, percentage of students whose first language differs from the language of instruction, school size, and principal gender. shows the percentage of schools across clusters in relation to the various school and principal characteristics as well as the total percentage of schools in each category. The chi-square test did not reveal any substantial differences across clusters with respect to the background characteristics of schools and principals. This is in line with previous research on instructional leadership. Instead, all clusters reflected the overall distributions of these characteristics.

Table 6. The distribution of schools across school and principal background characteristics

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we established five distinct clusters of leadership for learning across schools that participated in TALIS 2018. Cluster 1 is characterized by weak leadership for learning practice at all levels where lower scores are obtained on all variables, reflecting the theoretical dimensions represented in the instruments. Countries such as BRA, CHL, COL, CYP, CZE, BEL, NZL, and NLD have more than 30% of their schools in this cluster. At the same time, in this cluster, 15% of all schools are uncertainly classified. Cluster 2 is characterized mostly by neutral leadership for learning practice with a substantial emphasis on school autonomy for instructional practices and teacher professional development. This is the smallest and most distinct cluster. Latin-speaking countries, such as ESP, FRA, and PRT, as well as VNM, have most of their schools in this cluster. Cluster 3 is characterized by the fact that the leadership for learning practices are balanced at the schools belonging to it, with all indicators being moderately represented. This is the cluster in which the majority of the schools are found for more than half of the countries in our sample. SVN and GEO, for example, have more than 50% of their schools in this cluster. Cluster 4 which describes strong leadership for learning practice at all levels is characterized by a stronger instructional/curricular/assessment program, stronger orientation toward learning, stronger organizational culture, and stronger social advocacy. This is also the smallest cluster in terms of the absolute number of schools globally. Accordingly, this cluster is not a dominant one, with ARE being an exception with more than 30% of its schools being in this cluster. Furthermore, this cluster contains 33.4% of all uncertainly classified schools, suggesting that this cluster is not perfectly empirically isolated from one or more of the other clusters. Cluster 5 is characterized by Leadership for learning practice that is oriented toward stronger dimensions related to instruction, curriculum, and assessment but balanced on organizational culture and communities for learning. English speaking countries ENG, USA, AUS, but also other countries such KOR, ITA, MLT have more than 30% schools in this cluster. It caught our attention that in the two biggest clusters (Cluster 3 and Cluster 5) principals and teachers reported differently about distributed leadership practice, creating a potential gap in how leadership is perceived within schools. This issue has been already investigated in the literature showing gaps in perceptions between teachers and principals not only when leadership is studied (Goff et al., Citation2014; Urick & Bowers, Citation2017) but also for other phenomena (Brezicha et al., Citation2019). Further research could investigate how such gaps in perception shape school dynamics and climate.

Taken together, we can say that the distribution of schools that belong to a specific cluster at the country level does not reflect easily identifiable geographical, linguistic, or cultural similarities, which is contrary to our initial expectations given the theoretical background (Hallinger, Citation2018; Printy & Liu, Citation20210; Walker & Dimmock, Citation2002). However, we do find that some countries have more homogeneous leadership practices – ESP, FRA, and PRT constitute one such cluster of countries, as already mentioned. At the other extreme of this spectrum countries such as TUR, SAU, ARE, BRA, BGR, and CYP are found, representing countries with very heterogeneous leadership practices and schools that are relatively evenly distributed across all clusters. Although we cannot relate these findings to specific previous literature on leadership in each of these countries, a study by David and Abukari (Citation2020) on school leadership in the United Arab Emirates provides an interesting example – concluding that there is a lack of robust national policies and strategies on school leadership in this country. This finding is consistent with the observed heterogeneous leadership practices in this part of the world.

In contrast to the qualitative literature, which shows that school leadership is dependent on wider societal norms (Harris, Citation2020; Møller & Schratz, Citation2009), we find that leadership for learning predominantly is a school-level phenomenon within each country. In the current study, this is first supported by our three-level analysis, which decomposed the variance across teachers, schools, and countries. For most variables, the proportion of variance between countries is very small. The relatively homogenous distribution across clusters in most countries in the sample further supports this finding. The two variables with marked between-country variance are related to the degree to which schools stimulate effective professional development and the extent to which teachers report having high instructional autonomy. Both of these characteristics are particularly prominent in the profile for Cluster 2. This cluster is also the only cluster completely dominated by only a few select countries that were previously categorized as Latin-speaking European countries. Furthermore, consistent with previous research, we do not find that local school context (private/public, urban/rural, etc.) is substantially related to cluster classifications. However, the substantial variability at the school level might be explained by other variables that are not examined in this study but have been proven of great importance for leadership practice, such as school climate and school culture. The scope of this paper and availability of data in the TALIS dataset did not allow for targeted analysis of school level factors that could account for the variability of school clusters. Moreover, the present study does not include student SES, student achievement, teacher experience and teacher effectiveness that are relevant factors when leadership is studied at the school level. Future international comparative studies of school leadership would benefit greatly from including empirical observations of such school characteristics.

In addition to the obvious issue of omitted variables, the limitations of this study primarily relate to the specific method applied, the mixture of teacher and principal scales in one joint single analysis, and the previously discussed issue of measurement invariance. Cluster analysis is a purely descriptive method and, as such, it only describes the data at hand by grouping unorganized observations into a specified number of clusters, including no prior hypothesis and no possibility to test the outcome according to model-based assumptions. Another issue with cluster analysis is its inability to handle missing data. Consequently, only observations without missing data are included in the final analysis. Yet, in our case, the sample size was not substantially affected. Alternatively, latent profile analysis (LPA) could have been employed using the same data. However, this is a model-based approach that comes with certain assumptions, such as local independence for outcome variables. Specifically, this assumption implies that the associations between manifest variables included in the model are completely explained by their relationships with a latent variable (Hagenaars & McCutcheon, Citation2002). When this assumption does not hold, the model requires additional classes to be introduced, which results in continuous model fit improvement as additional classes are introduced. This is the case with our data as well, where latent profile analysis resulted (not reported) in an absurd situation – the inclusion of ever more classes improves the relative model fit. Another limitation relates to the use of aggregates of teacher data at the school level. This approach made it possible for us to represent leadership as a joint teacher and principal phenomenon. However, this approach does not fully account for the multilevel data structure (teachers nested in schools).

Furthermore, it should be noted that TALIS is not primarily a leadership survey. Rather, this is a broadly scoped study representing policy makers and researchers’ diverse interests for studying a large set of school-related phenomena. This implies that the expert committees with the task to construct the questionnaires will have to make tough priorities of what to include or not in the final instruments. Therefore, the variables selected for inclusion in our analysis does not represent a rich and detailed perspective of one specific theory of leadership. Consequently, our analysis builds on data representing only a partial representation of the Leadership for Learning framework. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the specific solution presented in this paper is affected by omitting important variables. However, TALIS is currently the only study that collects this kind of data across a wide range of countries and, consequently, represents a unique source for studying leadership for learning worldwide.

Currently, comparative perspectives on how leadership is affected by cultural, ideological, and political values have largely been based on qualitative inquiry rooted in the analysis of policy documents and interviews with stakeholders. This literature presents interesting findings about how leadership is a culturally embedded practice. However, contrary to these findings, such patterns could not be identified in the unprecedentedly rich quantitative materials collected in the TALIS study, including data from more than 40 educational systems across the world. Instead, the five distinctly different leadership profiles, as reported collectively by teachers and principals, exist in almost all countries. Moreover, most countries are not dominated by only one or two of these profiles. This calls for additional and better-targeted research on educational leadership as a global phenomenon.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jelena Veletić

Jelena Veletić is a doctoral research fellow at the Centre for Educational Measurement, Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Oslo, Norway. Her project is a part of the European Training Network (ETN) OCCAM which is a sub-call in the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Innovative Training Networks (MSCA ITN) of the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 framework. Jelena’s research relates to school leadership with a focus on studying variations of school leadership practices across systems, time- and school-level characteristics using large-scale assessment data.

Rolf Vegar Olsen

Rolf Vegar Olsen is a professor at the Centre for Educational Measurement, Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Oslo, Norway. He has a portfolio of research relating to national and international large-scale assessments. A main focus in his current research activities is to study how stakeholders can make use of data to inform and improve practices in classrooms and schools.

Notes

1. International Standard Classification of Education

2. A complete list of participating countries can be found in Appendix A.

3. Countries with more than 20% of data missing: SVN, KOR, NOR, COL, VNM, SAU, ISR, GEO.

4. Factor scores were calculated at the school level using Mplus version 8.4. on the pooled sample of schools. TYPE = COMPLEX and school weight were used to account for non-independence of observations and unequal probability of selection. The WLSMV estimator was used because data were categorical with three categories.

5. ; where Di represents the average dissimilarity between each observation i and all other points within the same cluster; and Ci represents the dissimilarity between i and the cluster that is closest to i right after its own cluster.

6. The 30% cutoff point is a pragmatic choice. If all clusters were evenly distributed, each cluster would include 20% of the schools. Given that for some countries the number of schools can be as low as 150, a 95% confidence interval for the proportion 20% would span the interval from 13% to 27%. 30% is the next rounded number beyond this confidence interval, and hence, is chosen to indicate that a cluster is overrepresented in a country.

7. Full table with percentages available in Appendix B.

References

- Ainley, J., & Carstens, R. (2018). Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 conceptual framework (OECD Education Working Papers, No. 187). https://doi.org/10.1787/799337c2-en

- Ashforth, B. E. (1985). Climate formation: Issues and extensions. The Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 837–847. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4279106

- Blitz, M. H., & Modeste, M. (2015). The differences across distributed leadership practices by school position according to the Comprehensive Assessment of Leadership for Learning (CALL). Leadership and Policy in Schools, 14(3), 341–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2015.1024328

- Bossert, S. T., Dwyer, D. C., Rowan, B., & Lee, G. V. (1982). The instructional management role of the principal. Educational Administration Quarterly, 18(3), 34–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X82018003004

- Bowers, A. J. (2020). Examining a congruency-typology model of leadership for learning using two-level latent class analysis with TALIS 2018 (OECD Education Working Papers No. 219). https://doi.org/10.1787/c963073b-en

- Boyce, J., & Bowers, A. J. (2018). Toward an evolving conceptualization of instructional leadership as leadership for learning: Meta-narrative review of 109 quantitative studies across 25 years. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-06-2016-0064

- Brauckmann, S., & Pashiardis, P. (2011). A validation study of the leadership styles of a holistic leadership theoretical framework. International Journal of Educational Management, 25(1), 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513541111100099

- Brewer, C., Okilwa, N., & Duarte, B. (2020). Context and agency in educational leadership: Framework for study. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(3), 330–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1529824

- Brezicha, K. F., Ikoma, S., Park, H., & LeTendre, G. K. (2019). The ownership perception gap: Exploring teacher job satisfaction and its relationship to teachers’ and principals’ perception of decision-making opportunities. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(4), 428–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1562098

- Byrne, B. M., & Vijver, F. J. R. van de. (2010). Testing for measurement and structural equivalence in large-scale cross-cultural studies: Addressing the issue of nonequivalence. International Journal of Testing, 10(2), 107–132.

- Clarke, S., & O’Donoghue, T. (2016). Educational leadership and context: A rendering of an inseparable relationship. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(2), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2016.1199772

- Crow, G. M. (2006), “Complexity and the beginning principal in the United States: perspectives on socialization„. Journal of Educational Administration, 44(4), 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230610674930

- Daniëls, E., Hondeghem, A., & Dochy, F. (2019). A review on leadership and leadership development in educational settings. Educational Research Review, 27, 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.02.003

- David, S. A., & Abukari, A. (2020). Perspectives of teachers’ on the selection and the development of the school leaders in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Educational Management, 34(1), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-02-2019-0057

- Day, C., Gu, Q., & Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(2), 221–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X15616863

- Dempster, N. (2019). Leadership for learning: Embracing purpose, people, pedagogy and place. In T. Townsend (Ed.), Instructional leadership and leadership for learning in schools: Understanding theories of leading (pp. 403–421). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23736-3_16

- DuPont, J. P. (2009). Teacher perceptions of the influence of principal instructional leadership on school culture: A case study of the American Embassy School in New Delhi, India. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota. http://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/50822

- Everitt, B. S., Landau, S., Leese, M., & Stahl, D. (2011). Cluster analysis (5th ed.). Wiley.

- Goff, P. T., Goldring, E., & Bickman, L. (2014). Predicting the gap: Perceptual congruence between American principals and their teachers’ ratings of leadership effectiveness. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 4(26), 333–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-014-9202-5

- Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership. In K. Leithwood, P. Hallinger, G. C. Furman, K. Riley, J. MacBeath, P. Gronn, & B. Mulford (Eds.), Second international handbook of educational leadership and administration (pp. 653–696). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0375-9_23

- Hagenaars, J. A., & McCutcheon, A. L. (2002). Applied Latent Class Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Hallinger, P. (2003). Leading educational change: Reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Cambridge Journal of Education, 33(3), 329–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764032000122005

- Hallinger, P. (2005). Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4(3), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760500244793

- Hallinger, P. (2008, March). Methodologies for studying school leadership: A review of 25 years of research using the principal instructional management rating scale [Paper presentation]. Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York.

- Hallinger, P. (2009, September). Leadership for the 21st century schools: From instructional leadership to leadership for learning [Paper presentation]. Chair professors: Public lecture series, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, China. https://repository.eduhk.hk/en/publications/leadership-for-the-21st-century-schools-from-instructional-leader-3

- Hallinger, P. (2011). Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111116699

- Hallinger, P. (2015). The evolution of instructional leadership. In P. Hallinger & W.-C. Wang (Eds.), Assessing instructional leadership with the principal instructional management rating scale (pp. 1–23). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15533-3_1

- Hallinger, P. (2018). Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143216670652

- Hallinger, P., & Leithwood, K. (1998). Unseen forces: The impact of social culture on school leadership. Peabody Journal of Education, 73(2), 126–151. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327930pje7302_6

- Hallinger, P., & Murphy, J. (1985). Assessing the instructional management behavior of principals. The Elementary School Journal, 86(2), 217–247. https://doi.org/10.1086/461445

- Halverson, R., Kelley, C., & Shaw, J. (2014). A call for improved school leadership. Phi Delta Kappan, 95(6), 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171409500612

- Harris, A. (2004). Distributed leadership and school improvement: Leading or misleading? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 32(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143204039297

- Harris, A. (Ed.). (2009). Distributed leadership: Different perspectives. Springer.

- Harris, A. (2020). Leading school and system improvement: Why context matters. European Journal of Education, 55(2), 143–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12393

- Herborn, K., Mustafić, M., & Greiff, S. (2017). Mapping an experiment-based assessment of collaborative behavior onto collaborative problem solving in PISA 2015: A cluster analysis approach for collaborator profiles. Journal of Educational Measurement, 54(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12135

- Hooge, E. (2020). The school leader is a make-or-break factor of increased school autonomy. European Journal of Education, 55(2), 151–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12396

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. SAGE Publications.

- Hoy, W. K. (1990). Organizational climate and culture: A conceptual analysis of the school workplace. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 1(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532768xjepc0102_4

- IMB Corp. (2017) . IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 26) [Computer software].

- Imig, D., Holden, S., & Placek, D. (2019). Leadership for learning in the US. In T. Townsend (Ed.), Instructional leadership and leadership for learning in schools: Understanding theories of leading (pp. 105–131). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23736-3_5

- Jacobson, S. L., & Johnson, L. (2011). Successful leadership for improved student learning in high needs schools: U.S. Perspectives from the International Successful School Principalship Project (ISSPP). In T. Townsend & J. MacBeath (Eds.), International handbook of leadership for learning (pp. 553–569). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1350-5_31

- Johnson, L., Møller, J., Jacobson, S. L., & Wong, K. C. (2008). Cross‐national Comparisons in the International Successful School Principalship Project (ISSPP): The USA, Norway and China. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 52(4), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830802184582

- Kalkan, Ü., Altınay Aksal, F., Altınay Gazi, Z., Atasoy, R., & Dağlı, G. (2020). The relationship between school administrators’ leadership Styles, school culture, and organizational image. SAGE Open, 10(1), 2158244020902081. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020902081

- Karada, E., & Öztekin, O. (2018). The effect of authentic leadership on school culture: A structural equation model. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management, 6(1), 40–75. https://doi.org/10.17583/ijelm.2018.2858

- Kassambara, A. (2017). Practical guide to cluster analysis in R: Unsupervised machine learning (Multivariate Analysis I) (Vol. 1, 1st ed.). Statistical Tools For High-Throughput Data Analysis (STHDA). https://www.amazon.com/Practical-Guide-Cluster-Analysis-Unsupervised/dp/1542462703

- Kassambara, A., & Mundt, F. (2020). Factoextra: Extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyse (1.0.7) [Computer software]. Software.

- Knapp, M. S., Honig, M. I., Plecki, M. L., Portin, B. S., & Copland, M. A. (2014). Learning-focused leadership in action: Improving instruction in schools and districts. Routledge.

- Krüger, M. L., Witziers, B., & Sleegers, P. (2007). The impact of school leadership on school level factors: Validation of a causal model. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 18(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450600797638

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership & Management, 28(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701800060

- Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 201–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450600565829

- Leithwood, K., Jantzi, D., & Steinbach, R. (2012). Changing leadership for changing times. Open University Press.

- Leithwood, K., Patten, S., & Jantzi, D. (2010). Testing a conception of how school leadership influences student learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(5), 671–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X10377347

- Liu, Y., Bellibaş, M. Ş., & Gümüş, S. (2021). The effect of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Mediating roles of supportive school culture and teacher collaboration. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(3), 430–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220910438

- Lubke, G. H., & Muthén, B. O. (2004). Applying Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Models for Continuous Outcomes to Likert Scale Data Complicates Meaningful Group Comparisons. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11(4), 514–534. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1104_2

- MacBeath, J., & Townsend, T. (2011). Thinking and acting both locally and globally: What do we know now and how do we continue to improve? In T. Townsend & J. MacBeath (Eds.), International handbook of leadership for learning (pp. 1237–1254). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1350-5_66

- MacBeath, J. (2019). Leadership for learning. In T. Townsend (Ed.), Instructional leadership and leadership for learning in schools: Understanding theories of leading(pp. 49–75). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23736-3

- Maechler, M., Rousseeuw, P., Struyf, A., Hubert, M., & Hornik, K. (2019). Cluster: Cluster analysis basics and extensions (R package version 2.1.0.) [Computer software]. Software.

- Mango, E. (2018). Beyond leadership. Open Journal of Leadership, 7(1), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojl.2018.71007

- Marks, H. M., & Printy, S. M. (2003). Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 370–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X03253412

- Miller, P. W. (2018). The nature of school leadership. In P. W. Miller (Ed.), The nature of school leadership: Global practice perspectives (pp. 165–185). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70105-9_9

- Millsap, R. E. (2012). Statistical approaches to measurement invariance. Routledge.

- Møller, J., & Schratz, M. (2009). Leadership development in Europe. In J. Lumby, G. M. Crow, & P. Pashiardis (Eds.), International handbook on the preparation and development of school leaders (pp. 341–366). Routledge.

- Muijs, D., & Harris, A. (2003). Teacher leadership—Improvement through empowerment?: An overview of the literature. Educational Management & Administration, 31(4), 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263211X030314007

- Murphy, J., Elliott, S. N., Goldring, E., & Porter, A. C. (2007). Leadership for learning: A research-based model and taxonomy of behaviors. School Leadership & Management, 27(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701237420

- Murphy, J., Elliott, S. N., Goldring, E., & Porter, A. C. (2007). Leadership for learning: A research-based model and taxonomy of behaviors. School Leadership & Management, 27(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701237420

- Opdenakker, M.-C., & Damme, J. V. (2007). Do school context, student composition and school leadership affect school practice and outcomes in secondary education? British Educational Research Journal, 33(2), 179–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701208233

- Oplatka, I., & Arar, K. (2017). Context and implications document for: The research on educational leadership and management in the Arab world since the 1990s: A systematic review. Review of Education, 5(3), 308–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3096

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2018). TALIS 2018 technical report [PDF file]. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/education/talis/TALIS_2018_Technical_Report.pdf

- Pont, B., Nusche, D., & Moorman, H. (2008). Improving school leadership, volume 1: Policy and practice [Online]. OECD Library. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/improving-school-leadership_9789264044715-en

- Printy, S., & Liu, Y. (2021). Distributed leadership globally: The interactive nature of principal and teacher leadership in 32 countries. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(2), 290–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X20926548

- Printy, S. M. (2008). Leadership for teacher learning: A community of practice perspective. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(2), 187–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X07312958

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321509

- Rutkowski, L., & Svetina, D. (2014). Assessing the Hypothesis of Measurement Invariance in the Context of Large-Scale International Surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 74(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164413498257

- Sahin, S. (2011). The relationship between instructional leadership style and school culture (Izmir case). Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 11(4), 1920–1927. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ962681

- Schley, W., & Schratz, M. (2011). Developing leaders, building networks, changing schools through system leadership. In T. Townsend & J. MacBeath (Eds..), International handbook of leadership for learning (Vol. 25, pp. 267–295). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-007-1350-5_17

- Slater, R. O., & Teddlie, C. (1992). Toward a theory of school effectiveness and leadership. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 3(4), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/0924345920030402

- Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Sage.

- Spillane, J. P., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. B. (2004). Towards a theory of leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000106726

- Tan, C. Y., Gao, L., & Shi, M. (2020). Second-order meta-analysis synthesizing the evidence on associations between school leadership and different school outcomes. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 174114322093545. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220935456

- Townsend, T. (2019). Instructional Leadership and Leadership for Learning in Schools: Understanding Theories of Leading. Springer International Publishing.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2016). Leading better learning: School leadership and quality in the Education 2030 agenda. UNESCO. https://silo.tips/download/leading-better-learning-school-leadership-and-quality-in-the-education-2030-agen

- Urick, A., & Bowers, A. J. (2014). What are the different types of principals across the United States? A latent class analysis of principal perception of leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50(1), 96–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X13489019

- Urick, A., & Bowers, A. J. (2017). Assessing international teacher and principal perceptions of instructional leadership: A multilevel factor analysis of TALIS 2008. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 18(3), 249–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2017.1384499

- Walker, A., & Dimmock, C. (2002). Moving school leadership beyond its narrow boundaries: Developing a cross-cultural approach. In K. Leithwood, P. Hallinger, G. C. Furman, K. Riley, J. MacBeath, P. Gronn, & B. Mulford (Eds.), Second international handbook of educational leadership and administration (pp. 167–202). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0375-9_7

- Wang, M.-T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 315–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9319-1

- Zieger, L., Sims, S., & Jerrim, J. (2019). Comparing Teachers’ Job Satisfaction across Countries: A Multiple‐Pairwise Measurement Invariance Approach. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 38(3), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12254

AppendicesAppendix A

List of countries participating in TALIS 2018

Appendix B

In this table, countries are sorted with increasing proportions of schools in Cluster 1. Entries in the table that represent more than 30% of schools in one of the clusters are colored as follows: Cluster 1 in red; Cluster 2 in green; Cluster 3 in mint; Cluster 4 in blue; Cluster 5 in lilac. In addition, the cells providing the country labels are colored to identify the most frequent cluster in each country. The distribution of clusters within countries differs. Some countries have three or more equally frequent profiles (e.g. Turkey, Brazil, Belgium, Singapore, Chinese Taipei), while others have the majority of their schools within one cluster (e.g. Portugal, Spain, Vietnam, France). Only one country (United Arab Emirates) has more than 30% of schools in Cluster 4, characterized by higher values on all variables.