ABSTRACT

The research on Early Childhood Education and Care leadership has mainly focused on the kindergarten manager’s perspectives. However, to fully understand leadership in ECEC settings, the middle-management level of pedagogical leaders must be included. The distributed framework is applied to investigate how the pedagogical leaders at the middle-management level enact and understand their leadership role. This study demonstrates that pedagogical leaders’ enactments emerge differently and manifest as three distinctive leadership types categorized as the administrative-, equality-, and reflective leader. This paper builds on data collected using the qualitative methodological framework of semi-structured group interviews, participatory observation, and a stepwise thematic analysis. It discusses how contextual factors impact the development of different leadership enactments. Findings challenge the notion of leadership in ECEC as highly democratic, flat in structure, weak, and demonstrate variations in leadership enactments. The conclusions drawn from the results suggest that a deeper insight into contextual factors is needed to understand the leadership’s complexity fully.

Introduction

Management and leadership concepts have gained an increasingly stronger foothold in educational research and practice, both in schools and early childhood education and care (ECEC).Footnote1 Due to a new norm introduced in 2018,Footnote2 in today’s Norwegian ECECs, a more significant proportion of staff is educated as kindergarten teachers (Kunnskapsdepartementet, Citation2018). The increased number of educated kindergarten teachers has led to various work structures, distributions of responsibility and tasks, and changes in pedagogical leaders’Footnote3 role enactments (Eide & Homme, Citation2019). However, until this millennium, research on leadership in ECEC has internationally been limited and dominated by a few scholars (Bloom, Citation1997, Citation2000; Bloom & Sheerer, Citation1992; Rodd, Citation1996). The trends in the research field of leadership in ECEC in Norway are similar, with only a few scattered research contributions before 2010 (Mordal, Citation2014). Additionally, the research on leadership has focused mainly on kindergarten managersFootnote4 and kindergarten owners (Børhaug et al., Citation2011; Børhaug & Lotsberg, Citation2014; Hard & Jónsdóttir, Citation2013; Jónsdóttir & Coleman, Citation2014; Lundestad, Citation2012; Skogen et al., Citation2009; Sønsthagen & Glosvik, Citation2020). The research situation in other Nordic countries and other parts of the world show similar trends (Halttunen et al., Citation2019; Hard, Citation2006; Hard & Jónsdóttir, Citation2013; Jónsdóttir, Citation2012; Strehmel et al., Citation2019). However, ECEC today has found its place globally as an essential part of educational institutions (Hujala et al., Citation2013). The increased interest and importance of leadership in ECEC is also evident in the growing body of research in the field over the past five to eight years (OECD, Citation2012; Hannevig et al., Citation2020; Hognestad & Boe, Citation2015; Waniganayake et al., Citation2012). With the support of management theory, Børhaug and Lotsberg (Citation2014) argue that understanding ECEC leadership’s nature must include both the organization’s top leader and other staff members. This growing interest in leadership in education also impacts the organizational learning and pedagogical function of multi-professional teams (Waniganayake et al., Citation2015). Besides, leadership and governance are an essential part of New Public Management (NPM) reforms, impacting the ECEC sector. (Børhaug et al., Citation2011; Børhaug & Lotsberg, Citation2010, Citation2016; Christensen & Lægreid, Citation2002).

The current study’s significance arises from the global and national interest in developing the notion of ECEC leadership and the need for more research in this area, especially regarding the middle-management level of pedagogical leaders. The following research questions are prepared and discussed in this paper: What characterizes middle management leadership of pedagogical leaders in ECEC? How do pedagogical leaders understand and construct leadership? This paper aims to investigate leadership at the middle-management level in Norwegian ECEC from the perspective of the pedagogical leaders’ practices and understandings, and are analyzed according to a distributed leadership approach that focuses on interactions, leadership practices, and contextual factors that impacts the distribution of power-relations and authority (Gronn, Citation2002; Spillane, Citation2012; Spillane et al., Citation2004). Recent research and theory development within the field of ECEC link leadership with distributed leadership (Heikka, Citation2014). This perspective may shed light on how pedagogical leaders cooperate with staff and on the tools and organizational routines they use in their leadership practices, as well as provide an insight into how leadership is designed as a foundation for developing and redesigning leadership practices (Spillane, Citation2012; Spillane et al., Citation2011).

The study aims to identify leadership practice and characteristics and look for variations in role enactment and leadership understandings. The analysis shows three categories of different leadership enactment and understandings. Based on the data, the leadership enactments are empirically developed. The leadership actions and understandings are characterized by specific leadership enactment, which connects to contextual factors. The findings presented in this paper show leadership actions and enactments as a collaborative and interdependent effort between multiple levels and participants, and not solely among those of the highest rank in an organization (Hujala et al., Citation2013; Spillane, Citation2012; Spillane et al., Citation2004). Also, the findings indicate that leadership enactment is complex and varied, and both collaborative and hierarchical by nature.

This paper is structured as follows: First, leadership in ECEC is contextualized, followed by the theoretical framework and the methodological approach. Then, a presentation and analysis of the findings are provided, followed by a discussion of the results. Finally, I offer some conclusions based on the study presented in this paper together with its implications.

Contextualizing early childhood education

The increased attention paid to leadership and management in Norwegian ECEC settings, reflects the overarching policy documents, local regulations and steering, and an increased formalized hierarchical structure and less democratic staff involvement (Børhaug, Citation2016). NPM trends have also increased the pedagogical leaders’ responsibilities as middle-management leaders in decision-making and operationalizing the pedagogical work (Børhaug & Lotsberg, Citation2014; Larsen & Slåtten, Citation2014). The implementation of Norwegian ECEC into the education system in 2005 has also created tensions in the educational expectation of ECEC, between learning, care, and play, and underscoring the perspective of learning (Engel et al., Citation2015; Ministry of Education and Research.; Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2017). Similar trends appear in international education and research and the OECD’sFootnote5 21st-century skills and competencies for the millennium (Kamerman, Citation2000; Mahon, Citation2010).

The Norwegian ECECs differ in size and organizational structure. The municipality governs the service with both private and municipal ownership as providers. The owner has an overall responsibility for ensuring that the ECEC center operates following prevailing laws and regulations. The kindergarten manager’s responsibility is to ensure that the ECEC center’s pedagogical practices comply with the national Kindergarten Act and the Framework Plan for Kindergarten (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2017). The pedagogical leaders may be responsible for one to two assistants and one kindergarten teacher, leading multi-professional teams, and 9–18 children, depending on their age.Footnote6

The formal education that gives the middle managers of the pedagogical leaders’ authority externally is weakened within a work culture characterized by democratic equality, close relationships, and equal distribution of labor (Helgøy et al., Citation2010). Limited division of labor is said to be explained by the ECECs strong emphasis on the practical rather than theoretical knowledge and kindergarten teachers’ weak professional competence and primary focus on care and ‘niceness’ (Steinnes & Haug, Citation2013).

In the Nordic countries, pedagogical leaders’ assignments and mandates are based on their societies’ values and institutional structures (Hujala, Citation2013). The formal role of pedagogical leaders in Norway is formulated in the current legislation and underpins the core tasks and enactment of their role (Hannevig et al., Citation2020; Ministry of Education and Research.; Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2017). Contextual factors, such as the size, location, ownership, structure, and organizational culture in the ECEC centers, are significant, as they underlie pedagogical leadership performance.

Distributive perspective on leadership

Democratic leadership and democratic participation are essential concepts in the Norwegian work culture that affect the public sector, especially the ECEC. Leadership in ECEC in Norway is exercised in close interaction with the staff. Theories of leadership that enhance cooperation are therefore relevant. Busch et al. (Citation2010, p. 324) divide leadership approaches into 1) leadership through others and 2) leadership with others through binding interaction. The latter approach is said to be characteristic of the Scandinavian democratic model of leadership. The theoretical perspective taken in this paper is leadership as interaction and as democratic processes. However, the distribution of authority and power is also a relevant aspect of leadership.

In the research literature in ECEC, the concept of distributed leadership was first introduced by Ebbeck and Waniganayake (Citation2002), valuing the collective understanding created through the knowledge that individual educators bring to the organization. Further, distributive leadership builds on the notion that leadership is socially constructed (Harris, Citation2003, Citation2008, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Harris & Jones, Citation2019b) and relational (Spillane & Coldren, Citation2011). These studies aimed to capture the multiple spheres of influence reflected in the ECEC setting (Waniganayake et al., Citation2012). The increased interest in the concept of distributed leadership in ECEC settings the recent years has also led to debates by several scholars (Bøe & Hognestad, Citation2017; Harris & Jones, Citation2019a; Male & Palaiologou, Citation2017; Sims et al., Citation2015). Building on Gronns’ (Citation2009) perspective, Bøe and Hognestad (Citation2017) argued that middle-management leadership is a hybrid leadership practice characterized by individual and collective work. Leadership is enacted by both formal and informal leaders, both separately and interdependently. More recent research on distributed leadership also enhances distributive or collaborative leadership’s importance as a catalyst for change in leadership practices (Azorín et al., Citation2020; Harris & Jones, Citation2019a).

Leadership is spread over the organization by people and context (Gronn, Citation2002; Heikka, Pitkäniemi et al., Citation2021; Spillane, Citation2012). According to Sims et al. (Citation2015), distributed leadership is the organization’s staff members’ construction and development of shared meaning. The Norwegian Framework Plan for kindergarten states that kindergarten managers and the pedagogical leaders’ have a professional obligation to ensure that their team has shared meaning and understanding of the ECEC mandate and are manifested in the teams’ pedagogical practices (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2017). Due to kindergarten’s framework plan, kindergarten managers have gained more responsibilities to different stakeholders and closer cooperation with the owners. The kindergarten managers, therefore, distribute leadership responsibilities to the pedagogical leaders. Developing interdependence between leadership stakeholders through shared construction and enactment is crucial (Heikka, Hujala et al., Citation2019). Heikka (Citation2014) found five dimensions of distributed pedagogical leadership where interdependence develops: (1) Enhancing shared consciousness of visions and strategies, (2) Distributing responsibilities for pedagogical leadership, (3) Distributing and clarifying power relationships between the stakeholders, (4) Distributing enactment of pedagogical improvement within centers, and (5) Developing a strategy for distributed pedagogical leadership. The key findings of Heikka, Hujala et al. (Citation2019) was that sufficient enactment of distributed leadership in ECEC settings was connected to pedagogical leaders’ commitment.

The practices of distributed leadership also relate to planning leadership enactment and are dependent on leaders’ active engagement (Harris, Citation2008; Mascall et al., Citation2009; Muijs & Harris, Citation2007). Scholars have also argued that distributed leadership significantly impacts outcomes for a group or an organization such as a school or an ECEC (Gronn, Citation2000; Harris, Citation2008; Harris & Jones, Citation2019a; Spillane et al., Citation2001). When pedagogical leaders tend to work at the same level as their assistants instead of raising the standards by acknowledging different roles, they may face difficulties assuming their leadership (Bøe & Hognestad, Citation2014; Hard & Jónsdóttir, Citation2013). The latest revision of distributed leadership framework by Gronn (Citation2011) has become more fruitful to understand the leadership enactment of the pedagogical leaders in ECEC because it reflects the combination of individual and collaborative leadership complexity. This way, researchers can integrate emergent leadership activities from hierarchical and democratic positions into a cohesive conceptual framework.

Although the literature on distributed leadership is extensive and the increased body of leadership studies is from ECEC settings, few empirical studies illustrate how leadership practices are enacted and develop and how situational factors seem to foster different leadership performances. The research presented in this paper provides empirical knowledge of the enactment of leadership practices showing both positional and distributive actions, depending on the context and relations it occurs, acknowledging distributed leadership as fruitful to capture the complexity and dual nature of leadership actions. I argue that the concept of distributive leadership opens to analyze the nature of leadership actions and understandings of pedagogical leaders in the ECEC and captures the complexity and dual essence of leadership enactment, both the distributive and solo efforts of leaders performing both collective and hierarchal leadership actions.

Further, the distributed leadership’s perspective opens to analyze the nature of leadership actions and the pedagogical leaders’ interpretations of their formal role described in legislation and work routines in the ECEC. The distributed leadership framework is considered relevant for analyzing how leadership is spread among all ECEC organization members, focusing on practices, relationships, and interactions between people in a specific context and how leadership enactments emerge differently. Moreover, how values and situational factors affecting their leadership actions and execution (Azorín et al., Citation2020; Bryman, Citation2011; Gronn, Citation2011; Halttunen et al., Citation2019; Hard, Citation2006; Heikka, Citation2014; Jónsdóttir & Coleman, Citation2014; Kallio & Halverson, Citation2020).

Methodology

This paper is based on participatory observation in four different ECEC organizations, group interviews with pedagogical leaders, and individual interviews with kindergarten managers. I spent between one to two weeks in each ECEC center, was present for full days each week, and participated in all daily activities and meetings.

The research process and the perspective on data collection are grounded in the specific theme or themes to be illuminated and the research questions. (Kvale, Citation2009). Methodological triangulation of participatory observation and semi-structured interviews was best suited to ensure validity in the research and to capture social relations, processes, and the informants’ constructions (Kvale et al., Citation2018). Further, the researcher’s impact or connection with the data should be minimized to ensure reliability in the research. As a researcher, I strived to distance myself from the data collected to ensure that the findings were based on actual circumstances and not assembled subjective discretion or unexpected events in the research process (Wadel, Citation2014).

The reflectivity and positioning in the field you study are essential when conducting participative observation (Fangen, Citation2010; Wadel, Citation2014). I gradually went from being perceived as a ‘visitor’ to be recognized more as a ‘staff member’. This role and position were somewhat similar across all the ECECs in the sample, which may have raised the research’s reliability. Also, a guide to focus the observation was used in all the ECEC. During fieldwork, I was attentive not to be seen as a researcher but rather as an equal colleague. I tried to facilitate conversations about everyday matters and asked questions as a new employee, thus avoiding deliberate professional topics. The latter proved to be particularly difficult and may have impacted both the participants’ actions, expressions, and perspectives.

The interviews with pedagogical leaders were conducted in groups and individually with kindergarten managers. As this study aims to capture the subjective perspective of each informant and obtain empirical material consisting of the interviewee’s descriptions (Fog, Citation2004, p. 11), the research interviews – individually and in groups – provide access to the complexity, detailed knowledge, and breadth of the pedagogical leaders’ experience beyond the participatory observation observations. The group interviews’ strengths and advantages are the opportunity to uncover understandings and beliefs and minimize power relations between the researcher and formats included in the current study (Brandth, Citation1996; Thagaard, Citation2018). Interviewing a socially natural group of pedagogical leaders in each ECECs opens up to capture the social context in which beliefs are formed (Brandth, Citation1996, pp. 159–169).

The sample

The ECEC-centers included in the study were strategically selected based on the inquiry’s relevance and the research questions (Grønmo, Citation2016). The four ECECs differ in ownership and geography; two are urban with private ownership, and two are rural with municipal ownership. This selection was also based on previous research that indicates that location may have implications for the quality of the pedagogical work, especially regarding cultural diversityFootnote7 (Andersen et al., Citation2011). Also, researchers have argued that leadership is vital to enhance the quality of pedagogical work and leadership in ECEC (Børhaug et al., Citation2011). The sample further consists of semi-structured interviews from 20 pedagogical leaders and four kindergarten managers in the same ECEC centers as follows:

The data from interviews with pedagogical leaders (PL) and the observational data serve as the primary data source. In contrast, the interviews with kindergarten managers (KM) are supplementary and enrich and contextualize the data. The informants and the ECECs are given pseudonyms, as shown in above.

Table 1. Sample overview – ECEC centers and the informants

Ethical considerations

The study has been prepared according to Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD) ethical guidelines. The ethical aspects of the research project were ensured by written approval from all the informants. All informants could also withdraw their consent at any time before publication. The duty of confidentiality is guaranteed by the safe storage of notes and audio recordings. All the transcribed data are anonymized, and the audio files will be deleted once the research is completed and approved. The names of informants and the ECECs have been anonymized to prevent recognition.

Data analysis

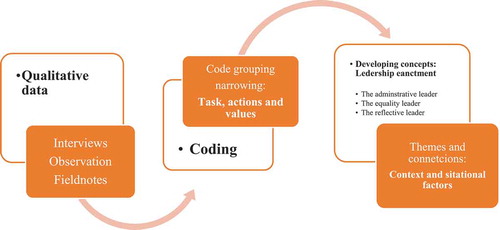

Using a stepwise analysis process inspired by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), six analysis phases were conducted. The first phase embraced reading the transcripts and noting all themes of interest, independently of analytical levels: leadership actions, understandings of ‘good leadership’, interactions and relations with staff, daily tasks and practices, collaboration, professional development, power relations, and more. The NVIVO software helped to systematize and structure the data material in coding and narrowing codes into concepts. After coding, the second step focused on the informants’ actions and practices and identified collaborative and hierarchical leadership actions. Although the data showed variations in the informants’ leadership actions, the interviews revealed common themes in their understandings and values of ‘good leadership’. Step three focused on the codes produced relating to ‘good leadership’ and ‘leadership actions’, including all the data. In phase four, the codes were further analyzed by critical assessment and evaluation. All transcripts were read several times to check whether anything had eluded the researcher’s attention. Phase five involved grouping the codes according to broader themes, narrowing them into larger code groups, developing leadership categories and concepts. The contracting, comparing, and grouping of codes across the entire population led to three types of leadership enactment: 1) the administrative leader, 2) the equality leader, and 3) the reflective leader. The categories were developed using an inductive method. The sixth phase of the analysis presents the findings of themes, actions, and leadership enactments in the following text sections. The findings cannot be generalized statistically, but discussions of the results against the background of theoretical concepts and relevant research raise questions of theoretical validity and reliability and may be transferable and applicable to similar situations and contexts (Simons, Citation2009; Tjora, Citation2019).

Empirical findings

The findings are analyzed according to above. The analysis shows both differences and similarities in the pedagogical leaders’ understandings and leadership enactment. Their actions as leaders, their tasks, and the values connected to leadership are shared. Further, the analysis of their leadership actions, tasks, values, and leadership understandings shows differences between the ECECs in the sample. These differences appear as three unique leadership types outlined above and are developed into concepts of leadership enactment. In the following text, the findings are presented as follows: 1) leadership tasks and actions, 2) leadership understandings and values, and 3) leadership enactment and constructions.

Leadership tasks and actions

The analysis shows common themes connected to pedagogical leadership and how leadership impacts the work in their team. Overall, the participants described ‘good leadership’ as the leader’s ability to facilitate co-determination and co-responsibility, the authority to lead their teams, contribute to motivation, cooperation, and a good working atmosphere. Their views are also related to organization and communication skills.

Analyzing the participants’ actions – what they do – identified the following categories of tasks and actions: 1) planning and organizing, 2) information and communication, 3) guidance and support, and 4) nurture and care. Further sorting and analysis resulted in two categories connected to leadership: tasks and nature of the leadership actions shown in below.

Table 2. Tasks and nature of leadership actions

According to the action’s nature, analysis of the tasks outlined in the table above identified two distinct leadership actions: collaborative and hierarchical, categorized as positional and distributive. Positional leadership actions are typical for leadership as a hierarchical position with responsibilities and objectives to ensure that an organization’s vital functions are maintained. Positional leadership actions include guidance and pedagogical knowledge development, resource allocation, adjustment of plans, and ad hoc decision-making when a situation changes due to unforeseen circumstances. Distributive leadership actions characterize leadership that is collaborative and democratic and spread among individuals beyond the leader, in line with distributive leadership’s theoretical approach.

Distributed leadership actions include information dialogue, joint decision-making, collaboration, and teamwork. Pedagogical leaders consider assistants in a unit to be equal coworkers who perform pedagogical tasks simultaneously. They highlight their leadership position in collaboration with assistants. Several scholars claim that work in ECEC is characterized by cooperation, interaction, and the distribution of tasks and resources within a nonhierarchical structure, which may seem accidental and less professional, having a minor emphasis on leadership (Børhaug, Citation2013; Hannevig et al., Citation2020; Hard & Jónsdóttir, Citation2013; Heikka, Citation2014; Løvgren, Citation2012). Rapid changes and many simultaneous activities characterize the work dynamics, schedule, and structure of ECEC. Pedagogical leaders need to plan activities that can easily be changed and justify their professional choices and actions. This work characteristic implies that the nature of pedagogical leaders’ work is both dual and complex, both positional and distributive in a rapidly changing work milieu.

Values: authority, trust, and democratic participation

Without exception, pedagogical leaders portray values of openness, inclusion, listening, trust, responsibility, and authority in their constructions of ‘good leadership’. Several also emphasize support and guidance as being essential to leaders. The excerpts from the informants’ statements in the table below illustrate common themes in the pedagogical leaders’ understandings and values regarding ‘good leadership’ across the population. The statements are grouped with actions and analyzed, and the category values are added as illustrated in below:

Table 3. Leadership constructions and nature of actions

Despite differences in the ECECs organization, ownership, and location, educational backgrounds, and work experiences, the pedagogical leaders’ (and the kindergarten managers’) have a shared understanding of ‘good leadership’ and ‘a good leader’ in all four ECEC centers. The pedagogical leaders and kindergarten managers, without exception, highlight cooperation, trust, and equality between leaders and staff as most vital to being ‘a good leader’, as well as control, responsibility, structure, and authority:

A good leader can work in close cooperation with their colleagues at the unit and in their team. At the same time, you must be able to cooperate with your parents. So, I also think it is fundamental to act based on the core values, to be tolerant of different cultures, people, and opinions (Monica, PL in Fjellgard).

However, results reveal that their constructions and understandings of leadership do not necessarily coincide with their leadership enactment. To get the work done smoothly and to ensure safety and the quality of nurture and care, and the pedagogical assignment, it is vital for pedagogical leaders to develop a reliable and robust team with trust and collaboration: ‘I think, as a leader, you must inspire your whole staff. That is vital. Also, we must have trust in each other. You are not alone. We have to pull the load together’ (Oline, PL in Parken).

In their daily routine, a ‘democratic structure’ and values of equality between all staff members find expression in a seemingly weak division of labor. No matter their position, all staff participates and does the same tasks: cleaning, changing diapers, dressing, or playing with children. However, the pedagogical leaders’ enactment in the daily routine shows that they perform various leadership tasks and activities, which implies leading pedagogical work with both children and staff and to ensure professional development while simultaneously performing the same practical cleaning and nurturing tasks. They conduct professional reflection, staff guidance, solicitation, and justifications of their leadership actions control, instructions, and task distribution within their team. These work relations ensure that daily tasks being done without problems, difficulties, or misunderstandings and ensure safety and sufficient care. A working atmosphere characterized by trust, motivation, and humor fosters good communication and cooperation, an essential prerequisite to the pedagogical leaders’ work. However, the nature of the close working relationships between staff and pedagogical leaders inevitably lead to some tension from time to time:

After breakfast, when the pedagogical leader, Grete, and the assistant are cleaning up, the pedagogical leader instructs the assistant to make the unit “letter of the month” (information letter to the parents). After 15 minutes, he returns with three pages of text and pictures. The pedagogical leader is not satisfied and tells him to do it again, explaining to him why. Grete’s comments of the assistant actions were unsolicited: “Maybe I was unclear in my communication. I felt a bit unkind, but there is a good reason for it. Besides, I find it vital that the assistant develop, and therefore they need to get used to being corrected and guided if they do things wrong.” (PL, in Solbakken).

Therefore, pedagogical leaders need to invest time and energy into creating a work culture with a high level of well-being, motivation, and trust. A democratic view and a tendency to emphasize equality between themselves and the unskilled staff enhance teamwork, joint decision-making, cooperation, and equality among all staff members, manifested as distributive leadership. Pedagogical leadership involves initiating, facilitating, and leading development processes related to learning and change in ECEC. However, there is no clear-cut distinction between distributed and positional leadership action as they will often appear simultaneously and intertwined.

As shown, the pedagogical leaders highlight the significance of professional competence and reflection in performing their role according to their mandate. Not surprisingly, however, their leadership practices are not always in line with this, as people tend to portray the ideal or the script of a formal organizational routine rather than how they behave in practice. According to this argument, relevant questions for further analysis are as follows: Are the leadership practices described as clear and robust, or are they more indistinct, focusing on joint decisions and equality? Furthermore, do the pedagogical leaders emphasize day-to-day activities, professional reflection, and knowledge development at the forefront? From an organizational routines’ perspective, leadership can be expressed as either positional or distributive or performative or ostensive actions and beliefs. The ostensive aspect is manifested through the informants’ perceptions of ‘good leadership’, role description, and the framework plan responsibilities. Their performative aspect is their leadership practices and actions, as observed through fieldwork.

The different leadership enactments differ but seem similar within each of the ECECs, indicating that contextual factors may impact the leadership enactment. The three leadership types are categorized based on the pedagogical leaders’ primary focus in their role enactment and understanding of leadership: 1) the administrative leader, 2) the equality leader, and 3) the reflective leader. The informants’ various actions combine interaction and positional capacity and are expressed through their leadership roles’ multiple tasks and aspects.

Leadership enactment: contextual and situational factors

To fully understand the pedagogical leaders’ enactment, the context of leadership actions is essential. The context is seen as the pedagogical assignment the pedagogical leaders are expected to work according to, i.e. values and institutional structures (Hujala, Citation2013, p. 53). The legislation lays the foundation of the pedagogical leaders’ work, and the ECEC owners translate and formulate their tasks and obligations as they wish within organizational instructions and other guidances. Institutional conditions, such as size, structure, and organizational culture within the ECECs, the context forms the basis for pedagogical leadership enactment.

The findings show that the leadership enactment differs across the different ECEC centers but that each ECEC seems to be dominated by one of the three leadership types. In Parken, the administrative leader dominates. The equality leader is most evident in Nordlys, while in Solbakken and Fjellgard, the most prominent leadership type is the reflective leader. The various pedagogical leaders show their understandings and actions as middle-management leaders in the different ECEC, both through their leadership actions as observed during fieldwork and their leadership constructions expressed in interviews and field conversations. The separate leadership enactment manifested through practice indicates a connection to the working culture and situational and contextual factors. In the following section, a deeper description of the three types of leadership enactment will be given.

The administrative leader- daily tasks, nurture, care, and information

It is one o’clock on Tuesday, and the meeting is about to start. Mona, the kindergarten manager, starts informing those present about sick leave and changes due to this: “Anne is a substitute this week.” Christine, one of the pedagogical leaders, replies that she will be away for an hour or two the next day due to a dentist appointment. The kindergarten manager also informs the pedagogical leaders of her absence on the coming Friday due to a municipal meeting. She asks the group if they have cases to tell or to discuss, to which they all reply that they have nothing to discuss and run off to their units (team meeting in Parken).

The administrative leader is mainly concerned with short-term activities and how to get ‘the day go smoothly’ and primarily concentrates on joint or distributive leadership among all the staff, receiving and giving information, and dialogue with staff. The structure of staff and pedagogical leaders is ‘democratic’, with less stress on positional leadership actions. The pedagogical leaders in Parken emphasize daily activities and administrative and practical tasks such as having enough staff, who is absent or on sick leave, who will prepare meals and change diapers, and more. Less time and priority are spent on pedagogical and professional development and staff guidance, as illustrated in the case above. Moreover, if they spend their time on pedagogical and professional development, it is accomplished somewhat invisibly and without being articulated. Limited time is spent reflecting on the framework plan’s content and interpretation or discussing plans with a longer time perspective. The translation of the Framework Plan for Kindergarten is read more like a script: ‘The Framework Plan tells us what to do in kindergarten and how to do it; it is our Bible’ (Oline, PL in Parken). In Parken, meetings had an informative purpose, and a tacit professional language characterizes discussions. The conversations I observed outside of formal meetings in Parken mostly revolved around practicalities, such as cleaning, diaper changing, sleeping call, having a lunch break, and outside playing with the kids. Only once during fieldwork did I hear the pedagogical leaders discuss professional development and the guidance of staff.

The equality leader- democracy, cooperation, and participation

In line with equality as an essential cultural value in Norwegian society and the Framework Plan for Kindergarten of 2017, the equality leader has a strong focus on sameness and equality. The reflective leader always puts the child at the forefront when faced with dilemmas in decision-making such the pedagogical leader, Karin in Nordlys, describes when facing and assessing a dilemma:

As a pedagogical leader, I acknowledge that my colleagues, the kindergarten manager, the owner, the parents, and the children have different needs that I must try to fulfill. Sometimes I feel frustrated because the municipality (the owner) puts pressure on us and imposes strict guidelines for our work while reducing financial resources and the time for cooperating and discussing essential issues. When faced with such dilemmas, I think that what is best for the child must always be at the forefront. The children must always be our main priority.

As Karin’s statement above illustrates, the equality leader focuses less on pedagogical development and guidance for their staff when faced with a lack of time or dilemmas. The equality leader stresses teamwork and joint decisions and does not stress their position as leaders, as demonstrated by the following quote in which Silje (PL) in Nordlys reflects on her role as a leader:

As a leader, you must be open and listen to what your staff thinks, and through thorough discussion, the whole team agrees. Thus, I think you can include the people you work with within most decisions regarding inclusion. Moreover, it is vital whether to go on day trips, daily activities, or other related issues, that all staff feels included in these decisions.

The equality leader accentuates sameness and equality. Furthermore, it is considered vital that the staff can participate and influence decisions. Also, in observing Ingrid (PL), it was hardly evident that she was the unit’s pedagogical leader. At first, I thought that one of the assistants was the pedagogical leader. When asked to reflect upon her leadership role, Ingrid (PL, in Nordlys) elaborated:

It is not essential, at least not to me, to come across as a leader. I mean, I do not have that role with the kids. Maybe, uh, not so much towards the parents either. However, at the same time, some parents are asking for it. Who is the pedagogical leader at the unit? Ehm, and then there are some situations, I feel I must appear as a more distinct leader, although my dedication as a leader promotes equality and cooperation and a sense of community. I am aware of this dilemma but think that a strong team is a team where all are acknowledged and equal. I am somewhat unsure how I convey my role to others.

As Ingrid, Karin, and Silje (all PL) in Nordlys emphasize, they acknowledge the sense of community, cooperation, and joint decisions as more vital than the performance as a formal and hierarchical leader. Observations of leadership actions in the daily routine and team meetings also confirm this.

The reflective leader – guidance, support, planning, and organizing

The reflective leader regards awareness of their professional justification as an essential part of their leadership role; Grete (PL) in Solbakken claims that this enables meaningful preparation for encountering criticism or different values and cultural understandings. Instructing the staff and presenting ‘practice stories’ at team meetings serve as documentation of pedagogical work and guidance and knowledge development. Also, the reflective leadership enactment focuses on the justifications according to the framework plan:

“The framework plan gives us justifications and guidance in our work. In team meetings, I use to enhance and pinpoint this to understand my leadership practices’ justifications to develop their professional practice. The assistants are often reluctant to use their plan because they do not want me to give them pedagogical assignments. However, I want them to push forward and develop professionally” (Sigrid, PL in Fjellgard).

In this context, the pedagogical leader has the function, both as a professional role model, providing unskilled staff with a professional language to support their knowledge development, and serve as facilitators and tutors. Moreover, as professionals, it allows them to guide the unskilled staff, and critically evaluate plans from stakeholders. In Solbakken, Knut (KM) enhances this approach as such:

Everyone must develop a “trained eye.” Observation and documentation are an essential part of what we do. We must discuss and build our “professional eye.” I tell my staff to practice observation and the skill of being concrete in their descriptions when documenting. I also stress the importance of professionalism and critical reflection on what we do, which means that we need professional justifications for what we do. Our professional justifications are essential to all the staff, not only the pedagogical leaders. I tell the pedagogical leaders to help guide those who are not.

In Solbakken and Fjellgard, the professional reflection level was high compared to the other two ECEC institutions in the sample, Nordlys and Parken. Moreover, leadership issues and the content of the Framework Plan for Kindergarten were discussed in team meetings on several occasions. In this respect, the kindergarten manager indirectly influences pedagogical work as required by legislation. In Solbakken, the pedagogical leaders (and kindergarten teachers) are encouraged to obtain more education, discuss leadership issues, and actively use their professional language. During meetings in Solbakken, I observed discussions of how to interpret the content of the Framework Plan for Kindergarten and issues to enhance pedagogical development in the ECEC:

It is Tuesday, and the weekly meeting between the pedagogical leaders and the kindergarten manager is about to start. The main item on the agenda today is how to improve the quality of “the meeting hour.” The group of pedagogical leaders suggests different solutions and reflects on why it is difficult. Maja, one of the pedagogical leaders, puts it this way: “It may be challenging to remember to use professional language and be explicit in everyday routine and unit meetings so that the assistant and unskilled staff learn and develop. I try to involve them in decision-making and express the justifications behind my actions. I also feel the need for more time to read and develop professionally, but that means less time with the children and the staff and more work for the staff.” Knut, the kindergarten manager, replied: “Even though taking time to read and do pedagogical planning and development may cause some burden on the staff in your units, I think, in the long run, it is valuable, both for your professional development and as pedagogical development for the staff and ECEC. After all, the framework plans tell us to ensure good pedagogical content, quality, and professional development.”

As the case above shows, there is a high level of professional reflection during meetings in Solbakken. However, putting professional issues on the agenda and discussing them contributes to knowledge development and awareness of their role as a leader. When Silje acknowledges the challenge of using professional language, she emphasizes the importance of staff participation in decision-making. At the same time, the importance of expressing her reasons for the staff, is a manifestation of the reflective leader type. Knut’s evaluation of the significance of professional updating by reading and emphasizes pedagogical planning as means for professional development also shows leadership enactment as a reflective leader. Discussions of professional and pedagogical issues from a long-term and future perspective are evident in the reflective leader category. Besides, the reflective leader emphasizes critical thinking and challenges, critically questions what the framework plan tells them, is open to be discussed and negotiated, and is eager to learn and develop leadership skills.

Discussion

This paper’s research questions address how pedagogical leaders in the Norwegian ECEC setting understand, construct, and enact their leadership roles. As shown, the informants have shared views and constructions of ‘good leadership’. Their leadership actions are shared, characterized by the dual nature of distributive and positional leadership actions. The leadership enactment is expressed in the various ECECs differently and manifests as three leadership enactments. Moreover, leadership enactments seem to be connected to contextual factors. In the following, shared leadership features are first discussed, followed by discussing the factors that influence the emergence of the different leadership enactment.

Shared characteristics of leadership

Research has shown that pedagogical leaders have gained increased responsibility as leaders carrying out their role with authority and providing professional development (Bøe, Citation2016; Bøe & Hognestad, Citation2017; Børhaug & Lotsberg, Citation2014; Larsen & Slåtten, Citation2014). The increased responsibility and a broader scope of choice may challenge how we conceptualize middle-management leadership in ECEC. Harris and Gronn (Citation2008) claim that both distributed and solo perspectives on leadership, when operating as approaches alone, are limited because they do not capture the dual nature of leadership actions as distributed and positioned. Considering this tension, Spillane (Citation2012) approach to leadership as generated in interaction with others (followers) in a specific context, supports a potential to understand pedagogical leaders’ middle-management role in a more fruitful way.

ECEC work is characterized by co-occurring, spontaneous, and preplanned activities. As the findings illustrate, the pedagogical leaders’ actions appear complex and two-fold, identified as positional and distributive actions, alternating throughout the day. Also, the pedagogical leaders’ obligation to ensure the pedagogical quality and their responsibilities of both the staff and group of children implies tensions between priorities and choices in their daily work. For some pedagogical leaders, the children’s needs always come first, as Karin stated when reflecting on what she finds most important in her role as a pedagogical leader. However, the pedagogical leaders may also ignore or undermine the professional development and positional leadership actions, as shown in both the equality and the administrative leadership enactment category.

The kindergarten managers are responsible for ensuring the fulfillment of all core functions of the ECEC organization. Still, they may leave it to others to make sure this happens. As outlined initially, an essential prerequisite for this perspective is that leadership actions are enacted by formal leaders and other staff members (Spillane, Citation2012; Spillane & Diamond, Citation2007; Strand, Citation2007). As the pedagogical leaders cannot be present in all situations, they are dependent on the delegation of tasks and responsibilities. Therefore, creating a solid and responsible team with shared values and understandings of the tasks and obligations, is vital. Accordingly, the pedagogical leaders need to build a team characterized by trust and openness and enhance staff motivation.

As shown, some pedagogical leaders will stress equality and under-communicate their role as formal leaders, focusing on practical tasks, whereas others enhance their professional role as leaders. What functions and tasks they prioritize, highlight, and put their energy in, vary depending on the type of leadership enactment.

Leadership as situated enactment

As indicated, the Framework Plan for Kindergarten formulates specific demands and expectations for pedagogical leaders. They are responsible for implementing the core values and pedagogical work, supervise and offer guidance. Further, planning, documenting, and assessing the work for children and staff implies a range of tasks and assignments at different levels and complexities (Ministry of Education and Research. Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2017). However, in their day-to-day work, care for the children, daily routines, and ensuring care, nurture, and safety must always be at the forefront. Professional development requires time and space. As argued, in a distributed leadership framework, leadership is seen as being generated in the interaction between manager and staff, time, and situation; i.e. context plays an essential role in understanding what characterizes leadership at the middle-management level in ECEC (Diamond & Spillane, Citation2016; Spillane, Citation2012). Consequently, different situational and contextual factors influence leadership actions and enactment: lack of time, a high level of sickness leave, work relations and organizational culture, the kindergarten manager’s leadership enactment, the parent group, competition between different ECEC, and the need to recruit vacant spaces. Comparing the various pedagogical leaders’ and the kindergarten managers’ educational backgrounds across all four ECECs shows no one in Parken had additional education.

In contrast, many of the pedagogical leaders and the kindergarten managers in Solbakken and Fjellgard had additional education, whereas three of five of the pedagogical leaders and the kindergarten manager in Nordlys had additional education (see ). The kindergarten managers’ leadership enactment, competition, and additional education in the staff, seem to impact the emergence of leadership enactment in the different ECECs: additional education, kindergarten managers as visible role models, and higher professional reflection and language. In Nordlys, the kindergarten manager was less visible than in Fjellgard and Solbakken; equality, nonhierarchical and flat structure was in Nordlys the prominent feature of the work relations and structure. In Parken, all the staff does the same tasks and mainly focusing on ‘making the day go smoothly’. The pedagogical leaders in Parken perform a leadership role with a lack of authority.

In comparison, contextual factors such as size, ownership, and location do not seem to influence the emergence of leadership enactment. Surprisingly, ownership does not seem to be a crucial factor in the emergence of leadership enactment. In the reflective leader category, the two ECEC ownership is both municipal and private. This finding contrasts studies that claim private ownership to a greater extend streamline and undermine reflection, freedom to use different methods, and critical professional thinking (see, for example, Dahle, Citation2020).

The pedagogical leaders have leadership responsibilities toward different types of staff, from skilled kindergarten teachers to inexperienced assistants, which has led to a pedagogical leadership role and work environment consisting of differentiated relations (Eide & Homme, Citation2019). According to Bøe and Hognestad (Citation2014), the pedagogical leaders’ enactment must be recognized as a hybrid. The hybrid enactments further imply that pedagogical leaders are members and professional leaders in the practice community (i.e. the team). Simultaneously, the pedagogical leader functions as a bridge-builder between objectives, the core values of pedagogical leadership, and learning in the teams. I argue that the core of the distributive leadership framework is that actions are both distributed and positional by nature and not hybrid, as Bøe and Hognestad (Citation2014) argue. In addition to the dual nature of leadership actions, findings also show variations in leadership enactments in the different ECEC manifested as administrative, equality, and reflective leaders. The reflective leaders come across as stronger leaders who are less afraid of decision-making and discussion than the administrative leaders and equality leaders. However, the different leadership enactments are not ranked hierarchically; they represent different interpretations and performances of the core responsibilities of the pedagogical leadership role and focus on various aspects of their leadership position. Besides, I argue that contextual factors play an essential role in how leadership enactments have emerged differently in the four ECECs.

The complexity and variety of leadership enactments tell us that although organizational routines are similar, and the legislation setting out the obligations and responsibilities in the practice of leadership is shared, people interpret and develop their roles and enact differently according to context, situation, and time. Leadership enactment is generated in the interaction between leaders, followers, and the situation: each element is essential to leadership practice (Spillane, Citation2012; Spillane et al., Citation2011).

‘We are equal, but I am the leader’: the complex role of pedagogical leaders

The findings presented in this paper show that the pedagogical leaders’ authority and enactments vary. These findings align with Lundestad (Citation2012) study of Norwegian pedagogical leaders’ work in ECEC settings. Researchers have also argued that pedagogical leaders and kindergarten teachers have a weak sense of leadership, lack of robusticity in their professional identity (Oberhuemer, Citation2005). Also, that the work structure in ECEC is characterized as democratic and ‘niceness’ and ‘sameness’ discourses (Hard & Jónsdóttir, Citation2013; Lazzari, Citation2012; Woodrow, Citation2008). As found in both Parken and Nordlys, ‘sameness’ and ‘niceness’ still is apparent but are not the work characteristics of all the ECECs in the study. A more authoritative leadership enactment is also evident, as the leadership characteristics of Solbakken and Fjellgard. More hierarchy and a more decisive leadership corresponds with more current research of ECEC leadership in Scandinavian countries and also internationally (Børhaug, Citation2013; Gotvassli & Vannebo, Citation2016; Hard, Citation2006; Hard & Jónsdóttir, Citation2013; Jónsdóttir & Coleman, Citation2014). Jónsdóttir (Citation2012) study of preschool teachers has a participatory and collaborative structure that is in line with distributed leadership (Harris, Citation2013b; Harris & DeFlaminis, Citation2016; Spillane et al., Citation2004) and is related to a more feminine leadership style (Schein, Citation2007).

However, the enactments and understandings of leadership presented in this paper show few indications of gender-specific leadership. Instead, leadership enactment seems to prevail from interacting with a range of contextual conditions in a given situation, which underpins the perspective of distributed leadership framework (Azorín et al., Citation2020; Harris & DeFlaminis, Citation2016; Spillane, Citation2012). The findings partly support previous research that points to the emergence of a more prominent leading role in practice. This case study of four kindergartens, twenty pedagogical leaders, and four kindergarten managers does not provide a basis for generalizing. However, the study underpinned by recent research shows that pedagogical leaders perform democratically and distributed leadership and more hierarchically positioned leadership enactment (Ebbeck & Waniganayake, Citation2002). Focusing on what the pedagogical leaders do, their interactions with ‘followers’, and the implication of contextual factors in which the leadership actions occur will provide a deeper meaning of pedagogical leaders’ role. Bøe and Hognestad (Citation2017) argue that the concept of hybrid management is fruitful when attempting to understand the complexity of the role because it involves individual engagement and cooperation and a mixture between solo and democratic leadership in line with Gronn’s (Citation2002) approach. However, Heikka, Pitkäniemi et al. (Citation2021) claim that Bøe and Hognestad’s perception of leadership as a hybrid disregards distributed leadership’s core elements. As interdependent members of the (ECEC) organization, formal and informal leaders perform leadership actions. Therefore, to achieve common goals interdependence between leadership stakeholders for leaders and staff is crucial (Heikka, Pitkäniemi et al., Citation2021).

Consequently, from this perspective, leadership can be performed in many ways and may develop differently, despite a shared framework, legislation, and similar work structure. Through interaction, the pedagogical leaders build good relationships and teams in their unit, underpinned by research that indicates that pedagogical leaders attach importance to forging close ties with assistants (Børhaug & Lotsberg, Citation2014). However, the desire for equality can lead to weaker leadership and an undermining of communication in their different roles, making it harder for them to take a strong leadership position (Hard & Jónsdóttir, Citation2013). Similar characteristics of leadership performance are found in both the administrative and the equality leader. However, the reflective leader performs a leadership role with more authority, emphasizing the professional development of teams and the assistants, and may indicate a shift in leadership practice.

Nevertheless, ‘the discourse of niceness’ and equality between the staff and pedagogical leaders remain evident, as the category of equality leader shows. ‘Niceness discourse’, combined with leadership responsibilities, makes the pedagogical leadership role more complex and dual. Further, as pointed in this paper, vital factors such as education, rural or urban location, private or municipal ownership, competition between the ECECs, and the kindergarten’ managers’ leadership enactment influence the leadership enactment of the pedagogical leaders. The governmental reform that increased educated staff in ECEC by 50%, wanted to heighten the quality and streamline the ECECs nationally. However, Eide and Homme (Citation2019) evaluation of this reform found a high variation in work structure and relations between units in the same ECEC and between ECECs with the same owner. Eide and Homme (Citation2019) findings support my argument that a shared formal framework does not necessarily result in the same work structure relations and leadership enactments, but allows different interpretations of leadership and variations in structures and work ties to develop.

Leadership has since 1998 been an essential part of kindergarten teachers’ education: those who have been recently educated are more likely to focus on reflection and academic justification. Also, in Solbakken and Nordlys, two ECECs in the sample, have established an introductory program for graduated kindergarten teachers and pedagogical leaders. Many have participated and have been encouraged to receive further education, which is likely to affect academic reflection. However, as these two ECECs are categorized by different leadership enactments, respectively, as reflective and equality leaders, other factors may also impact the emergence of leadership performance, focus, and priorities. This perspective supports recent findings of emergent leadership in ECEC and underpins the importance of including contextual and situational factors when analyzing leadership (Halttunen et al., Citation2019; Harris & Jones, Citation2019b).

Conclusions and implications

This paper aimed to show how leadership practice and role enactment, through interactions and relations, are distributed, shaped, and developed based on different contextual elements, and asked the following research questions: What characterizes middle management leadership in Norwegian ECEC? How do pedagogical leaders understand and construct leadership? As shown, leadership is understood through and rooted in democratic values and group-oriented, collaborative, and participative work relations in line with the distributed leadership approach. Besides, the pedagogical leaders’ actions also show positional leadership in a more hierarchical structure, in line with Hognestad and Bøe (Citation2016). As demonstrated in this paper, the pedagogical leaders lead their teams, focusing on guidance and professional development, resulting in a more complex and diverse professional leadership role. I have argued that the distributive leadership approach focusing on relations and interactions offers an insight into how leadership actions and leadership enactment emerge in the interaction between contextual factors and activities performed by the pedagogical leaders.

Further, the findings have shown that the pedagogical leaders’ participation in leadership processes and their leadership enactments vary, and dual leadership actions line with research in the field (Bøe & Hognestad, Citation2017; Børhaug & Lotsberg, Citation2010; Heikka, Pitkäniemi et al., Citation2021; Larsen & Slåtten, Citation2014). By practicing tasks in interaction with staff, parents, and children, the pedagogical leaders contribute to implementing political decisions, using tools and organizational routines to ‘design’ and ‘redesign’ their leadership practice and enactment in different ways (Feldman & Pentland, Citation2003; Spillane et al., Citation2011). Thus, leadership actions result from both people and relationships in action (Harris & DeFlaminis, Citation2016; Harris & Jones, Citation2019a; Spillane, Citation2012; Spillane et al., Citation2004). I have argued in favor of focusing on what leaders do, i.e. the pedagogical leaders’ practice, in line with the distributed leadership framework and their leadership perceptions to give a richer understanding of the characteristic of middle-management in ECEC.

Using the distributive framework to understand leadership in ECEC has provided empirical insight into the nature of leadership as situated practice and enactment. The result of this study has shown the complexity of pedagogical leaders’ roles, enacting with both authority and equality, and variations between the different ECEC organizations, underscoring the need for contextualization to understand the pedagogical leadership role’s characteristics fully. As argued, contextual and situational factors are vital to understanding the emergence of leadership practices and enactment in different contexts. More empirical research from different ECEC settings and contexts will contribute to gain a fuller and deeper understanding of the nature and characteristics of pedagogical leaders in ECEC.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hilde Hjertager Lund

Hilde Hjertager Lund is a doctoral candidate at The Faculty of Education, Sport and Art, Department of Pedagogy, Religion and Social Studies, Western Norway University of Applied sciences, Contact: Inndalsveien 28 5063 Bergen, Norway. Her research interest’s early childhood leadership and educational research, cultural diversity, cultural capital, migration, and ethnographic studies in education research.

Notes

1. The acronym ECEC (Early Childhood Education and Care) will be used in this paper for when referring to kindergarten. Norwegian ECEC is mostly for social pedagogical purposes. The municipalities are responsible for ECEC in Norway. There are both private and public providers. Children between the ages of one and five can attend ECEC. ECEC is financially subsided, but parents must pay a fee.

2. The Kindergarten Act states that kindergarten managers and pedagogical leaders must be educated as kindergarten teachers or have other tertiary-level education that leads to a qualification for working with children and pedagogical expertise. Kindergarten teacher education is a three-year university/university college course leading to a bachelor’s degree. According to the regulations there must be one pedagogical leader for every seven children under the age of three and one for every 14 children over the age of three. Pedagogical leaders work in teams with assistants to provide for groups of children. In addition to the regulation for child-to-teacher ratios, there is a regulation for the child-to-staff ratio. According to regulations, there are to be a maximum three children per staff member when the children are under three years of age and a maximum of six children per staff member when the children are over three years of age. Assistants either receive vocational training as childcare and youth workers at the upper-secondary level or are unskilled (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2005).

3. The term pedagogical leader is the formal position of middle – management leaders in Norwegian ECEC. The term pedagogical leader will be used throughout the text describing middle -mangers position. The pedagogical leaders have leadership responsibilities for the staff and children in their unit and are given the responsibility for implementing and directing the educational and pedagogical work in line with good professional judgment. The pedagogical leader shall guide and ensure that the Kindergarten Act and the framework plan are fulfilled through the pedagogical work. Further the pedagogical leader has the responsibility to lead the work on planning, implementation, documentation, assessment, and development of the work in the children’s group or within the areas he/she is set to lead.

4. The kindergarten manager has responsibility for the entire staff and is the manager at the top level of the ECEC organization. The kindergarten manager is to enable staff to put its expertise to practice and has overall responsibility for ensuring pedagogical content and quality in line with legislation.

5. The OECD is an international cooperative organization and a network for the purpose of discussing political issues. The goal is to promote economic growth, free trade, and capitalist development. In 1996, the Council of Ministers adopted the motion that kindergarten and education should be one of the OECD areas of interest. This has resulted in three reports from the member states, which are often referred to in Norwegian governance documents, and research on kindergarten internationally.

6. The Norwegian ECEC divides children in age groups: 0–2 years, 3–4 years, and 5–6 years. This enables age-differentiated pedagogical content and activities.

7. This study is part of a lager research project that investigates middle management leadership and cultural diversity in Norway. This paper focuses on the issue of leadership, whereas another paper, focuses upon cultural diversity and is not included in this paper (Author, Citation2021). The same observation guide was used, including both themes. Also, the interview guide was divided in two with questions of 1) cultural diversity 2) leadership. The data used in this paper is the connected to leadership enactments.

References

- Andersen, C. E., Engen, T. O., Gitz-Johansen, T., Kristoffersen, C. S., Obel, L. S., Sand, S., & Zachrisen, B. (2011). Den flerkulturelle barnehagen i rurale områder: Nasjonal surveyundersøkelse om minoritetsspråklige barn i barnehager utenfor de store byene. Høgskolen i Hedmark Rapport nr. 15 – 2011

- Azorín, C., Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2020). Taking a distributed perspective on leading professional learning networks. School Leadership & Management, 40(2–3), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1647418

- Bloom, P. J. (1997). Navigating the rapids: Directors reflect on their careers and professional development. Young Children, 52(7), 32–38. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42727440

- Bloom, P. J. (2000). How do we define director competence?Child care information exchange, 13–15.

- Bloom, P. J., & Sheerer, M. (1992). The effect of leadership training on child care program quality. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 7(4), 579–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/0885-2006(92)90112-C

- Bøe, M. (2016). Personalledelse som hybride praksiser: Et kvalitativt og tolkende skyggestudie av pedagogiske ledere i barnehagen(Doctoral Thesis). NTNU, Trondheim.

- Bøe, M., & Hognestad, K. (2014). Knowledge development through hybrid leadership practices. Nordic Early Childhood Education Research Journal 8(6), 1–14.

- Bøe, M., & Hognestad, K. (2017). Directing and facilitating distributed pedagogical leadership: Best practices in early childhood education. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(2), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2015.1059488

- Børhaug, K. (2013). Democratic early childhood education and care management? The Norwegian case. In Researching leadership in early childhood education in Researching Leadership in Early Childhood Education (pp. 145–162). Tampere: Tampere University Press 2013.

- Børhaug, K. (2016). Barnehageleiing i praksis. Samlaget.

- Børhaug, K., Helgøy, I., Homme, A., Lotsberg, D. Ø., & Ludvigsen, K. (2011). Styring, organisering og ledelse i barnehagen. Fagbokforlaget.

- Børhaug, K., & Lotsberg, D. Ø. (2010). Barnehageledelse i endring. Nordisk Barnehageforskning [Elektronisk Ressurs], 3, 79–94. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.277

- Børhaug, K., & Lotsberg, D. Ø. (2014). Fra kollegafellesskap til ledelseshierarki? De pedagogiske lederne i barnehagens ledelsesprosess. Nordisk Barnehageforskning, Institutt for barnehagelærerutdanning ved Fakultet for lærerutdanning og internasjonale studier, Høgskolen i Oslo og Akershus. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.628

- Børhaug, K., & Lotsberg, D. Ø. (2016). Barnehageleiing i praksis. Samlaget.

- Brandth, B. (1996). Gruppeintervju: Perspektiv, relasjoner og kontekst. In H. Holter & R. Kalleberg (Eds.), 1997: Kvalitative metoder i samfunnsforskning (pp. 145–165). Universitetsforlagets Metodebibliotek.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryman, A. (2011). Research methods in the study of leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The Sage handbook of leadership (pp. 15–28).

- Busch, T., Dehlin, E., & Vanebo, J. (2010). Organisasjon og organisering [Organisation and organising]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (2002). New public management: The transformation of ideas and practice. Ashgate Pub Limited.

- Dahle, H. F. (2020). Barns rett til lek og utdanning i barnehagen. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Pedagogikk Og Kritikk, 6, 100–114. https://doi.org/10.23865/ntpk.v6.2055

- Diamond, J. B., & Spillane, J. P. (2016). School leadership and management from a distributed perspective: A 2016 retrospective and prospective. Management in Education, 30(4), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020616665938

- Ebbeck, M., & Waniganayake, M. (2002). Early childhood professionals: Leading today and tomorrow. Elsevier.

- Eide, H. M., & Homme, A. D. (2019). Jo flere vi er sammen …. En undersøkelse av organisering og arbeidsdeling i åtte barnehager med økt andel pedagoger. Research report, NORCE, Norwegian Research centre AS.

- Engel, A., Barnett, W. S., Anders, Y., & Taguma, M. (2015). Early childhood education and care policy review. OECD.

- Fangen, K. (2010). Deltagende observasjon. Fagbokforlaget.

- Feldman, M. S., & Pentland, B. T. (2003). Reconceptualizing organizational routines as a source of flexibility and change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(1), 94–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/3556620

- Fog, J. (2004). Med samtalen som udgangspunkt: Det kvalitative forskningsinterview [Conversation as the key point: The qualitative research interview]. Copenhagen, Denmark: Akademisk Forlag.

- Gotvassli, K.-Å., & Vannebo, B. (2016). Utvikling av barnehagen som lærende organisasjon–den pedagogiske lederfunksjonen. In K. H. Moen, K.-Å. Gotvassli, & P. T. Granrusten (Eds.), Barnehagen som læringsarena. Mellom styring og ledelse (pp. 255–272). Universitetsforlaget.

- Grønmo, S. (2016). Samfunnsvitenskapelige metoder (2 ed.). Fagbokforlaget.

- Gronn, P. (2000). Distributed Properties. A new architecture for leadership. Educational Management & Administration, 28(3), 317–338.

- Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(4), 423–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00120-0

- Gronn, P. 2009. Hybrid leadership (pp. 35–58). Routledge.

- Gronn, P. (2011). Hybrid configurations of leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The Sage handbook of leadership (pp. 437–454).

- Halttunen, L., Sims, M., Waniganayake, M., Hadley, F., Bøe, M., Hognestad, K., & Heikka, J. (2019). Working as early childhood centre directors and deputies – Perspectives from Australia, Finland and Norway. In M. Waniganayake, J. Heikka, P. Strehmel, E. Hujala, & J. Rodd (Eds.), Leadership in Early Education in Times of Change (1 ed., pp. 231–252). Verlag Barbara Budrich.

- Hannevig, L., Lundestad, M., & Skogen, E. (2020). Pedagogisk leder i barnehagen: Samhandling, organisering og dialog (1. utgave ed.). Fagbokforlaget.

- Hard, L. (2006). How is leadership understood and enacted within the field of early childhood education and care. Queensland University of Technology.

- Hard, L., & Jónsdóttir, A. H. (2013). Leadership is not a dirty word: Exploring and embracing leadership in ECEC. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 21(3), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2013.814355

- Harris, A. (2003). Teacher leadership as distributed leadership: Heresy, fantasy or possibility? School Leadership & Management, 23(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363243032000112801

- Harris, A. (2008). Distributed leadership: According to the evidence. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(2), 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230810863253

- Harris, A. (2013a). Distributed leadership matters: Perspectives, practicalities, and potential. Corwin Press.

- Harris, A. (2013b). Distributed school leadership: Developing tomorrow’s leaders. Routledge.

- Harris, A., & DeFlaminis, J. (2016). Distributed leadership in practice: Evidence,misconceptions and possibilities. Management in Education, 30(4), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020616656734

- Harris, A., & Gronn, P. (2008). The future of distributed leadership. Journal of educational administration, 141–158. Bradford, England.

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2019a). Leading professional learning with impact. School Leadership & Management, 39(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2018.1530892

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2019b). Teacher leadership and educational change. School Leadership & Management, 39(2), 123–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1574964

- Heikka, J. (2014). Distributed pedagogical leadership in early childhood education. Tampere University Press.

- Heikka, J., Hujala, E., Rodd, J., Strehmel, P., & Waniganayake, M. (2019). Leadership in early education in times of change – An orientation. In J. Heikka, E. Hujala, J. Rodd, P. Strehmel, & M. Waniganayake (Eds.), Leadership in Early Education in Times of Change (1 ed., pp. 13–16). Verlag Barbara Budrich.

- Heikka, J., Pitkäniemi, H., Kettukangas, T., & Hyttinen, T. (2021). Distributed pedagogical leadership and teacher leadership in early childhood education contexts. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 24(3), 333-348. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2019.1623923.

- Helgøy, I., Homme, A., & Ludvigsen, K. (2010). Mot nye arbeidsdelingsmønstre og autoritetsrelasjoner i barnehagen. Tidsskrift for Velferdsforskning, 13(1), 43–57.

- Hognestad, K., & Boe, M. (2015). Leading site-based knowledge development: A mission impossible? Insights from a study from Norway. In M. Waniganayake, J. Rodd, & L. Gibbs. (Eds.), Thinking and learning about leadership. Early childhood research from Australia, Finland, and Norway (pp. 210–228).

- Hognestad, K., & Bøe, M. (2016). Studying practices of leading–Qualitative shadowing in early childhood research. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(4), 592–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2016.1189725

- Hujala, E. (2013). Contextually defined leadership. In E. Hujala, M. Waniganayake, & J. Rodd (Eds.), Researching Leadership in Early Childhood Education (pp. 47–60). University of Tampere.

- Hujala, E., Waniganayake, M., & Rodd, J. (2013). Researching leadership in early childhood education. University of Tampere.

- Jónsdóttir, A. H. (2012). Professional roles, leadership and identities of Icelandic Preschool Teachers: Perceptions of stakeholders (Doctoral Theisis), University of London. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11815/7280

- Jónsdóttir, A. H., & Coleman, M. (2014). Professional role and identity of Icelandic preschool teachers: Effects of stakeholders’ views. Early Years, 34(3), 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2014.919574

- Kallio, J. M., & Halverson, R. (2020). Distributed leadership for personalized learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 52(3), 371–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1734508

- Kamerman, S. B. (2000). Early childhood education and care: An overview of developments in the OECD countries. International Journal of Educational Research, 33(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(99)00041-5

- Kunnskapsdepartementet. (2018) . Forskrift om endring i forskrift om pedagogisk bemanning og dispensasjon i barnehager.

- Kvale, S. (2009). Det kvalitative forskningsintervju (2. utg. ed.). Gyldendal akademisk.

- Kvale, S., Brinkmann, S., Anderssen, T. M., & Rygge, J. (2018). Det kvalitative forskningsintervju (Vol. 4. oppl., 3. utg. ed.). Gyldendal akademisk.

- Larsen, A. K., & Slåtten, M. V. (2014). Mot en ny pedagogisk lederrolle og lederidentitet? Tidsskrift for Nordisk Barnehageforskning, 7, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.541

- Lazzari, A. (2012). Reconceptualising professionalism in early childhood education: Insights from a study carried out in Bologna. Early Years, 32(3), 252-2. [Abingdon, Oxfordshire].

- Løvgren, M. (2012). I barnehagen er alle like. In B. Aamotsbakken (Ed.). Ledelse og profesjonsutøvelse i barnehage og skole.(pp. 37–49). Universitetsforlaget.