ABSTRACT

Research focusing on schools are often permeated by the assumption that leadership plays an important role when it comes to school development and success. This article contributes to the field by offering a scoping review of the literature on middle-level leadership in secondary schools from 2002 to 2021. The overall goal is to provide an overview of organizational research on this topic and thereby to discuss new paths informed by a behavioral and complex systems perspective. After an initial search which identified 1047 abstracts and three screening phases, 32 articles were selected for analysis with the goal of answering seven research questions covering: geographical location, research methods, definitions of middle-level leadership, theoretical perspectives, organizational objectives, relationships between middle-level leadership with decision-making processes and central themes. Findings indicate a wide variety of definitions of middle-level leadership, theoretical perspectives, research methods and central themes approached in the article. There is a complex interplay between organizational processes that either facilitate or restrain the variation necessary to match the complexity of the environment. The discussion of findings paves the way for a reflection on new directions for research in this field, informed by a behavioral and complex systems perspective.

Introduction

Different waves of reform in educational policy in the past 20 years in most Western countries have aimed at making schools more publicly accountable for student performance (Day et al., Citation2020). This development has raised a discussion of the relationship between school leadership and educational outcomes. School leadership is usually regarded as a central element of school improvement and effective functioning (Blandford, Citation1997; K. Leithwood et al., Citation2008; Lipscombe et al., Citation2021; Turner & Bolam, Citation1998). Despite the variety in terms of theoretical perspectives in this field, most literature on educational leadership emphasizes the role of school principals in leading change and improvement processes (Daniëls et al., Citation2019; Lipscombe et al., Citation2021). There is a widespread assumption that leadership has an impact on school effectiveness (Daniëls et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the role of school leaders is often seen as intersecting the space between policy and practice (Day et al., Citation2020). In this regard, middle leaders occupy an interesting position as a crossing point among the different processes that take place in schools. However, recent reviews have pointed out that the very concept of middle leadership in schools is difficult to define, and its activities involves a series of paradoxical and contextual factors. The present scoping review narrows the discussion from educational leadership in a broader perspective to an investigation of middle-level leadership in secondary school settings.

This study aims to contribute to organizational research on middle leadership in schools by presenting a scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Horsley, Citation2019) of peer-reviewed articles on this topic between 2002 and 2021. As described by Munn et al. (Citation2018), scoping reviews provide overviews of the main evidence that has emerged in a defined area of research, identifying possible gaps and spaces for further development rather than focusing on narrowly defined research questions as in the case of systematic reviews. Furthermore, this study articulates a conceptual framework that applies concepts of complexity theory to its discussion of research findings (Bento, Citation2011a, Citation2021; Byrne & Callaghan, Citation2013; Morrison, Citation2010; Mowles, Citation2021; Sandaker, Citation2009; Stacey, Citation2009).

The present study aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1:

Where were the studies conducted? (country)

RQ2:

What research methods were applied?

RQ3:

How has middle leadership been defined?

RQ4:

What theoretical perspectives are applied and/or discussed?

RQ5:

What organizational objectives have been articulated?

RQ6:

What is the role of middle leaders/managers in the decision-making process in schools?

RQ7:

What are the central themes related to middle-level leadership?

The contribution of the present study in relation to previous literature reviews on school middle management is three-fold. First, it raises overall research questions that are different from other reviews. Although questions related to roles and definitions (RQ3 in this study) have been approached by other reviews in this field (De Nobile, Citation2018, Citation2021; Lipscombe et al., Citation2021), other important aspects of organizational life such as adaptive processes (RQ5) and decision-making (RQ6) have not been addressed. Furthermore, previous reviews did not explore the diversity in terms of research methods in this field and by doing so, this study aims at opening the space for the discussion about possible methodological developments aiming at grasping complex organizational phenomena such as school leadership. Second, it highlights a complexity and behavioral conceptual perspective that informs the analysis of the findings. The choice of the frame of reference of complex systems is here justified as this presents conceptual tools that allow for understanding system adaptation, emergence deriving from local processes of interaction (often treated as the main analytical unit) and non-linearity in more central and elaborated manner than most other theoretical perspectives in this field. Third, this study narrows down the discussion to the specific case of secondary schools. This delimitation derives from the recognition that secondary schools usually have larger organizational structures than primary schools. Having more staff and increased interdependencies indicates higher levels of complexity (Siegenfeld & Bar-Yam, Citation2020), which further highlights the need to examine middle-level leadership not only in terms of positions in formal structures but also in relation to emergent and complex webs of interactions. The study does not depart from an initial statement about who middle leaders are but opens the space for different understandings of middle level leadership to be explored mainly by RQ3, RQ5 and RQ6.

In many parts of this article and in the analyzed literature, the terms ‘leadership’ and ‘management’ are used interchangeably. This is because, although the two concepts carry important differences in meaning, complex organizational reality usually means that the two processes are organically intertwined and, therefore, it is often difficult to understand them separately from each other. As Alvesson and Sveningsson (Citation2003) observed, a mythologization of leadership as something ‘special’, in contrast to management as something closely associated with bureaucracy and stability, can limit our ability to understand complex emergent phenomena in organizational settings. Our discussion of middle-level leadership in relation to different organizational contingencies from a selectionist perspective (Sandaker, Citation2009) further elaborates on this discussion.

The first part of the article is dedicated to a presentation of school leadership as an area of study and the articulation of a frame of reference of complexity theory to discuss learning and change in organizations. RQ1 (countries) and RQ2 (methods) have an exploratory logic and therefore not informed by the conceptual dimension of this study in this part of the study. However, the structure of first part of the article relates to and follow the same order of research questions from three to seven. The second part describes the scoping review process across literature search, screening, and analysis. Then, the article proceeds to the presentation and categorization of findings. In this part, a bibliographical analysis in the form of a network visualization of the co-occurrence of keywords is presented. The discussion of findings and conclusion present recommendations for further research and reflections on practice and leadership development.

Conceptual dimension

The conceptual dimension of this study is articulated in three subsections: previous research on middle-level leadership, school leadership as a field of study and the relation between complexity and middle-leadership.

Previous research on middle-level leadership

The following conceptual review highlights the importance and paves the way for the analysis of findings related to research question three (RQ3) focusing on different understandings of the concept of middle-level leadership. The first problem that we encountered when reviewing middle-level leadership in school is related to the very definition of the concept (Lipscombe et al., Citation2021). The narrative synthesis provided by Lipscombe et al. (Citation2021) demonstrates that many studies have tended to define middle leadership in terms of positionality by identifying individuals who operate between senior leaders and teaching staff and exercise leadership by belonging to both groups. On the other hand, it seems that teachers with formal leadership responsibilities fit the most common description of middle-level leadership. De Nobile (Citation2021) noted that a considerable share of studies has claimed that teachers that do not occupy formal leadership positions may still engage in leadership roles. This notion poses limits to purely positional definitions of middle leadership. In this regard, even the definition of middle leadership in terms of formal positions may not be a straightforward one. For instance, should deputy principals be regarded as senior leaders while coordinators are considered middle leaders? Given the complex and multifaceted reality of the school setting, De Nobile (Citation2021) presents a more nuanced definition of middle leadership:

In light of all this it might be prudent to conceptualize middle leaders as individuals who may or may not be in formal promoted positions but nevertheless have responsibility for an aspect of school organization, and middle leadership as the behaviour of individuals that influences aspects of school functioning and influences other staff members. In other words, middle leadership is not just about positions of authority or hierarchy, but the influences people have in the space between senior leadership at one end and teachers and other staff (including junior or emergent leaders) at the other. (p. 5)

Although this definition identifies both individuals in formal positions and individuals who influence the running of the school and the behavior of others, this still leaves open questions with regard to the roles and the relationship between middle leadership and decision-making processes. Prior studies have considered deputy principals as middle leaders (Cranston et al., Citation2004; Khumalo & Van der Vyver, Citation2020; Lipscombe et al., Citation2021; Shore & Walshaw, Citation2016, Citation2018). Despite the difficulty in defining middle leadership and little evidence of its impacts, most studies seem to agree that it directly or indirectly affects teaching, organizational change and professional development (Lipscombe et al., Citation2021). The review conducted by De Nobile (Citation2021) also highlights that there is little consensus in terms of what constitutes the roles, inputs and outputs of middle leadership. This reflection on definitions and roles informed research question three (RQ3) and six (RQ6) in this study.

School leadership as field of study

This subsection presents some important perspectives applied in the field of school leadership and informs the formulation of research question four (RQ4). Most research on school leadership is explicitly motivated to identify leadership behavior and practices that can be associated with organizational success. The quest for ‘what works’ is thus highly emphasized in most organizational studies about school leadership (Day et al., Citation2020). The review of the field provided by Daniëls et al. (Citation2019) identified four main leadership theories that have permeated most debate about school development: instructional leadership, situational leadership, transformational leadership and distributed leadership. This is an evolving field, with new theories often emerging in response to perceived weaknesses in existing ones, but also allowing for the investigation of different aspects of school leadership.

Instructional leadership is highly centered on the activities of the school principal and their impact on teaching and learning (Hallinger, Citation2003, Citation2005). It is often presented as a top-down approach by emphasizing the principal’s role in coordinating and influencing teaching. Hallinger (Citation2003) further articulated the concepts on three main axes: curriculum coordination, programs management and school learning climate consolidation. As Daniëls et al. (Citation2019) described, instructional leadership emphasizes the following constructs: mission/vision/goals, mission communication, professional development, and a top-down approach.

A further focus on contextuality has permeated the concept of situational leadership (Thompson & Glasø, Citation2015), which claims that employee behavioral patterns and formal and informal organizational structures greatly influence leadership behaviors and outcomes. The concept assumes that there is no single best practice, as leadership phenomena are highly dependent on environments and context. Successful leaders have the capacity to adapt to both individuals and groups that they are trying to influence. This leadership model was adapted to school settings following an overall discussion about the relationship between leadership and contexts in organizational studies in the 1970s (Hersey et al., Citation1979). Daniëls et al. (Citation2019) place the focus of situational leadership on the following constructs: context and characteristics of the organization.

Transformational leadership theory emerged in the 1980s and identified capacity-building and promoting higher levels of personal commitment to organizational objectives as the main tasks of school leaders (K. Leithwood & Sun, Citation2012). As K. Leithwood and Jantzi (Citation1999) described it, the transformational leadership model is articulated throughout six leadership dimensions and four management dimensions. The leadership dimensions are ‘building school vision and goals; providing intellectual stimulation; offering individualized support; symbolizing professional practices and values; demonstrating high expectations for performance; and developing structures to foster participation in school decisions’ (p. 454). The management dimensions include ‘staffing, instructional support, monitoring school activities, and community focus’ (p. 454). Daniëls et al. (Citation2019) claim that transformational leadership differs from instructional leadership in at least two aspects: It is a shared and bottom-up model in contrast to the top-down nature of instructional leadership, and it places a higher priority on change rather than only management and control in relation to defined organizational goals. The transformational leadership concept is often presented as valid in a variety of organizational and cultural settings and, therefore, the importance of context is de-emphasized compared to the situational leadership model (Yu et al., Citation2002). The main constructs here are the following: mission/vision/goals, mission communication, a bottom-up approach, and motivating staff toward achievement and self-actualization (Daniëls et al., Citation2019).

As the field evolved, the claim that improvement in educational institutions could be achieved by exceptional visionary leaders turned out to be unrealistic and disconnected from complex organizational realities (Timperley, Citation2005). The concept highlights the collective as its main analytical focus, moving from the leader’s individual behaviors to the processes taking place in everyday interactions (Bento, Citation2011b). Bennett et al. (Citation2003) highlighted some central premises of distributed leadership: an emerging property of a group of interacting individuals, the openness of the boundaries of leadership, and the idea that various forms of expertise are distributed across the many, not the few. Spillane (Citation2006) claims that distributed leadership indicates that leadership is a shared process and that activities take place in the context of the interactions of multiple and emerging leaders, not all of whom necessarily occupy formal management positions. It is expected that different individuals can play a role as leaders depending on the context and tasks at hand (Gronn, Citation2002). The main constructs articulated in the literature about distributed leadership include the following: mission/vision/goals, mission communication, bottom-up approach, context, collaboration, and leadership by multiple individuals, teams and groups (Daniëls et al., Citation2019).

More recently, leadership for learning has represented an integration of different constructs and assumptions of previously existing leadership concepts (Daniëls et al., Citation2019). The explicit goal orientation on student achievement is a central aspect of leadership for learning (Hallinger, Citation2011). This goal will most likely be promoted by sustaining learning in every aspect of school life, including teaching, assessment, curriculum development, management and finance (Murphy et al., Citation2007; Townsend et al., Citation2013). Leadership for learning integrates elements of previous school leadership concepts. For instance, it shares a focus on leadership beyond formal management positions and incorporates a team orientation like distributed leadership. Moreover, it recognizes organizational contexts as in situational leadership (Hallinger, Citation2011).

The question (RQ4) that arises is as follows: How many of the main education leadership concepts presented here (if any) have been applied to the study of middle-level leadership in schools? Before answering this question in the light of this scoping review, we will narrow the subject down from school leadership from a wider perspective to the specific field of middle leadership in schools.

Complexity and middle-level leadership

The recognition of complexity and its relation to school leadership highlights the importance of research questions five, six and seven (RQ5, RQ6 and RQ7). Rather than seeing schools as static entities, a complex systems perspective would examine educational institutions in terms of webs of interactions and the flow of resources within the surrounding environment (Morrison, Citation2010). Preiser (Citation2019) highlights important characteristics of complex adaptive systems. These include emergent network structures, adaptation as structures and functions change over time (as consequences of both internal interactions and environmental change), negative and positive feedback loops, the flow of resources within the environment, contextuality and complex (non-linear) causality. Schools present several features of complex adaptive systems (Aouad & Bento, Citation2020; Bento, Citation2011a). In schools, formal structures co-exist with emergent webs of interaction across and among pupils, teachers, managers and parents. In other words, such systems are constituted relationally. There are formal and informal communication processes through which agents constantly enable and constrain each other (emergence and feedback loops). There is an interplay of multiple factors, such as interests from different stakeholders and the need for adaptation to environmental changes (open boundaries and flow of resources). This indicates a multifaceted reality that needs to be understood at different levels of analysis while considering the emergence of new patterns of behavior and non-linearity.

In complex science, the main analytical focus is always on interrelations and emergent outcomes rather than on individual parts. The application of the concepts of complexity theory to the study of management in organizations brings an important contribution by focusing on interaction processes, adaptation and the emergence of novelty. First, there is an opportunity to re-conceptualize leadership in organizations (Mowles, Citation2021; Stacey, Citation2009). Second, there is a need to understand how changes in environmental contingencies may favor variability and affect different behavior patterns in organizations (Sandaker, Citation2009).

Stacey (Citation2009) discusses the role of leaders in terms of complex responsive processes. He states that, rather than being pre-defined, the role of the leader emerges from and is continuously constructed in a process of social recognition. People working in organizations engage in communicative interactions and power relations, thereby evoking and provoking responses from each other. As he describes it, leaders both enact and are acted on by social interactions; they are acting in unknown circumstances like anyone else. In this regard, he defines the responsibility of effective leaders as the need ‘to widen and deepen communication between members of a group through exercising skills of conversation that keep opening up the possibility of new meaning rather than closing down on further exploration’ (Stacey, Citation2009, p. 215). However, Stacey discusses leadership and management from a broad perspective without narrowing it down to the role of middle management.

Sandaker (Citation2009) describes how different dynamics in the processes of production bring changes to the selection of an organizational perspective. From a selectionist perspective, changes in society and working life pose implications for the ‘acquisition, change and extinction of behavioral patterns’ (Sandaker, Citation2009, p. 277). In this way, knowledge-based organizations encourage internal variation when facing the challenges of an increasingly complex and interconnected environment. This contrasts with organizations in early industrial societies, which were characterized by constraining organizational behavior, interaction restricted to lines of command and the selection of a limited assortment of behavior patterns. Instead, modern knowledge-based organizations face the challenge of matching the complexity of the environment (Siegman & Bar-Yam, Citation2020) and, therefore, there is a need to facilitate variation and interaction beyond formal hierarchical structures and thereby create a sufficient basis for selection in response to an ever-changing environment. This development brings important implications for middle-level management, as highlighted in Sandaker et al. (Citation2014). In organizations looking for standardized processes and products, middle management tends to assume a primarily controlling function in which they have limited exposure to external contingencies from both senior management and users. On the other hand, in organizations aimed at matching the complexity of the environment, middle-level management creates a smooth communication channel between the strategic character of top management and individuals working on the core business of the organization. In many ways, middle-level management reduces the control span for strategic leadership usually exercised by those in top-management positions. This role is mainly concerned with open communication and the emergence of new practices and knowledge in response to environmental changes.

This brief review of the complexity perspective of organizations informs a central question of this study: What roles do middle-level leaders assume in terms of the selection of organizational behavior? Thus, the recognition of organizational complexity underpinned the formulation of research question five (RQ5) in this study.

Recognizing complexity has implications for how we observe decision-making in organizational settings and how such processes always involve uncertainty. Furthermore, there is a shift here from a dominant perspective on decision-making in terms of autonomous individuals in a rational manner often presented as a programmatic activity (Stacey, Citation2007). In complex systems, decision-making is regarded as processes that involve uncertainties and paradoxes taking placed in the context of non-linear processes and emergent process of interactions. Such recognition raised the formulation of research question six (RQ6) in this study and the importance of understanding if and how different studies investigate possible relations between the role of middle-leaders and decision-making processes. Research question seven (RQ7) is embedded by the complexity and multifaceted dimensions of leadership. As claimed by Stacey (Citation2007), organizational life can be observed in terms of emerging themes which may be identified and articulated by leaders in ways that either facilitate or restrain adaptive processes. Therefore, the formulation of RQ7 identifies in an exploratory manner the central themes articulated in the different articles.

Methods

The literature search was conducted in December 2021, and the following databases were utilized: Academic Search Ultimate, ERIC, Education Source and Scopus. The selection of databases involved focusing on two important sources in the field of education (ERIC and Education Source) in which this study is located and two important multidisciplinary ones (Scopus and Academic Search Ultimate). The main search terms were (S1) middle leadership OR deputy principal* and (S2) school×. Some decisions in relation to selection of keywords had to be made. For instance, the term ‘teacher leadership’ which usually denotes educators who assume administrative tasks outside teaching activities was not included for the sake of precision as this activity may be not regarded as middle level leadership or management in all contexts. The first line aims at taking into account linguistic differences as in some countries, the term deputy principal is used, while it is not in other countries. The truncation * was used to select both singular and plural usages of the terms. The search terms were combined with the Boolean term ‘AND’. In all databases, the search covered titles, abstracts and keywords. The search was restricted to peer scholarly reviewed articles published in English between 2002 and 2021.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included empirical studies presenting interventions at the school level, conceptual studies aiming at grasping definitions and theoretical developments in the field of educational leadership and review studies. Furthermore, we did not limit our search to any geographical area. On the other hand, the literature search had two main delimitations. First, it included only studies that had a primary focus on middle-level leadership. This means that articles that discussed educational leadership at a broad level without presenting a specific focus on middle-level leadership were not included. Second, we selected studies that investigated or discussed middle leadership at the secondary education level. This is mainly because secondary schools usually have larger organizational structures than primary and pre-schooling institutions.

Search results

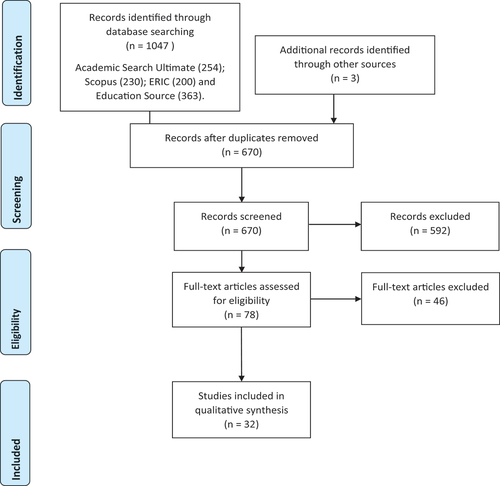

The following flowchart () illustrates the processes of identification, screening, and selection of articles:

The search results in the four databases included the following: 363 on Education Source, 254 on Academic Search Ultimate, 230 on Scopus and 200 on ERIC. A total of 1047 articles were initially imported to EndNote, and after 377 duplicates were removed, a total number of 670 unique entries were assessed with Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). The first two authors independently screened abstracts and assessed these in relation to the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. After the blind review option was removed, the two assessments were compared, and conflicts between these were resolved in communication with the third author. At this stage, 78 (n = 78) articles were selected for further screening by the three authors. The second screening search stage consisted of reading and appraising full-text articles for eligibility. This is the stage when 45 (n = 45) articles were excluded, mainly due to not being specifically about secondary education.

Data extraction and analysis

The data extraction and analysis involved both data-driven and theory-driven processes (Gibbs, Citation2002). This means that in some cases, data categorization had an emergent logic with labels being generated from the data itself, while in other cases, coding was informed by previous developments in the field.

The categorization of data related to RQ1 and RQ2 had an emergent logic, meaning that geographical location and research methods were extracted from the articles. Highlighting the definition of middle leadership (RQ3) in the selected literature followed a non-linear approach. The categories emerged through in-depth reading of each text to identify (1) an explicit definition of middle leadership within the research context and (2) areas of the texts that highlight the roles and responsibilities of middle leaders in their school contexts. Four categories emerged after the in-depth reading: Category 1: deputy principals who are part of the school’s top management team and are without teaching responsibilities; Category 2: a head of a department within the school who is without teaching responsibilities; Category 3: a subject head or head of a department who has teaching responsibilities in addition to their leadership roles; Category 4: roles where middle leadership is not clearly defined, and roles and responsibilities are not explicit enough to infer a definition.

The categorization of theoretical perspectives (RQ4) also followed a data-driven approach, meaning that the leadership theories and concepts identified in each article became empirical codes in themselves. On the other hand, the categorization of organizational objectives (RQ5) followed a theory-driven strategy, meaning that the findings were coded according to the selectionist conceptualization provided by Sandaker (Citation2009) and Sandaker et al. (Citation2014). This stage had an interpretive dimension, meaning that the categories ‘standardized processes and outcomes’ and ‘matching the complexity of the environment’ were operationalized in the context of middle-level school leadership. Thus, words that indicate restricting organizational variation, such as ‘rules’, ‘standards’, ‘procedures’ and ‘control’, were labeled in the first category. Terms that indicate facilitating variation, innovation, exploration of new possibilities and communication across formal structures were categorized as ‘matching the complexity of the environment’.

Similar to the categorization process adopted for RQ3, the categories for RQ6, which was aimed at identifying the role of middle leaders in the decision-making process within the school management structure, emerged following an in-depth analysis of references to decision-making in the selected literature. Six categories emerged from the analysis: Category 1: middle leaders who have the autonomy to make local decisions in their respective departments or subject areas with reporting responsibilities to the schools’ top management; Category 2: middle leaders who are part of the decision-making team or part of the schools’ senior management team; Category 3: middle leaders not part of the schools’ decision-making team; Category 4: middle leaders responsible for facilitating consensus within the school community as part of the decision-making process; Category 5: the middle leaders’ role in the decision-making process within the school was not specified; Category 6: due to the expanding workload of middle leaders and the lack of structured training for the role, the need for middle leaders to be involved in the decision-making process is questioned. The categorization of findings related to RQ7 followed a data-driven logic, meaning that after three rounds of analysis, the following seven categories were identified: influence/authority/effects/impact of middle leadership, career trajectories/transitions, leadership development, tensions/challenges, roles/practices/behaviors of middle leaders, responses to policy reform and leadership skills.

In many ways, this analysis process had an interpretive logic. However, open communication and cross-checking among the three researchers aimed to reduce possible biases and inconsistencies.

Findings

depicts empirical findings by highlighting data extracted from the selected articles in relation to each research question:

Table 1. Overview of included articles.

RQ1: geographical distribution

The above table provides a summary of the main characteristics of the articles included in the present scoping review. The descriptive information of each study is presented, which includes country, research methods, definitions, theoretical perspectives, organizational objectives and decision-making processes. This scoping review yielded studies conducted in nine different countries. The most researched country of the studies was the United Kingdom (n = 10). The second most cited country was New Zealand (n = 6), followed by Australia (n = 5), Hong Kong (n = 4) and South Africa (n = 3). We also included studies conducted in mainland China (n = 1), Lesotho (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1) and Singapore (n = 1).

RQ2: research methods

The bulk of the articles reviewed were qualitative studies. The most common research design choice described a qualitative approach (n = 18) working with different kinds of data and methods, but mostly based on interviews. The second most frequently used research methodology in the selected articles was the quantitative approach (n = 8) mostly consisting of collecting data through surveys. Three studies utilized the mixed method design, which included a case study and Delphi method and both a survey and interview for collecting the data (n = 3). Two (n = 2) of the articles did not explicitly state the data collection and analysis technique(s) used, followed by one systematic review (n = 1).

RQ3: definitions of middle-level leadership

The analysis of definitions of middle leadership, as presented in the above table, reveals different understandings about who was classified as a middle leader within the schools’ management and leadership structures where the studies were conducted. Middle leaders are mostly defined in the selected literature (n = 20) as subject heads or heads of departments who also have teaching responsibilities in addition to their role within the school leadership structure. Another definition that emerged from the selected literature (n = 4) was the classification of middle leaders as heads of departments who have no teaching responsibilities. However, literature (n = 1) indicates that both subject heads and heads of departments who have teaching responsibilities and those without may also be classified as middle leaders within a school leadership structure. While middle leadership was not clearly defined in some of the selected literature (n = 2), some studies (n = 6) classified the deputy principal (without teaching responsibilities) as part of the school’s top management team.

RQ4: theoretical perspectives

The analysis of theoretical perspectives revealed a relative diversity. By far, the most frequently referenced concept was distributed leadership (n = 14). Other established school leadership concepts were also referenced: instructional leadership (n = 7), transformational leadership (n = 2) and situational leadership (n = 1). While most studies referred to theory in one way or another, four studies (n = 4) did not. These articles referred to and related their data to previous research findings without explicitly applying or discussing theory or leadership concepts. However, many theories and concepts that did not originally derive from research on school leadership were either applied as part of conceptual frameworks guiding empirical work or discussed at some point in the articles: practice architecture (n = 1), institutional theory (n = 1), structure agency (n = 1), practice architecture (n = 1), learning communities (n = 1), teacher-centered education (n = 1), institutional transformational theory (n = 1), three-skill theory (n = 1), post-positivism (n = 1), market management performance (n = 1), path-goal theory (n = 1), career anchorage (n = 1), job choice theory (n = 1) and educational leadership for inclusion (n = 1).

RQ5: organizational objectives

The analysis of articles in relation to organizational objectives and the selection of organizational behavior demonstrated that in most articles (n = 21), it was possible to identify both elements of standard processes/outcomes and evidence of matching the complexity of the environment. In such studies, either findings and conceptual perspectives seemed to indicate a co-existence and an organic relationship between features of organizational contexts that either restrained or facilitated variation. One example is the article by Au et al. (Citation2003), which examines both ‘facilitative enabling’ and ‘formal structuring’ as aspects of middle leadership. The first aspect is described as ‘enabling teachers to rethink ideas, providing new ways to look at things, thinking about old problems in new ways, developing a vision, getting teachers to share in the development of the vision, motivating teachers to use creative skills and having a clear vision for the department’ (Au et al., Citation2003, p. 484). On the other hand, formal structuring is related to “matters such as supervising teachers, expecting teachers to follow rules and regulations, requiring teachers’ performance of the highest standard, leading formal discussions on student achievement, providing teachers with feedback on their performance and to formal planning” (Au et al., Citation2003, p. 484). In some articles (n = 7), the focus on standard processes/outcomes was further emphasized over an adaptive process. This is exemplified by Bassett (Citation2016, p. 105), who stated that ‘whilst most middle leaders in this research emphasized the leadership aspect of their role, in practice their time was dominated with managerial compliance tasks’. In only two (n = 2), the main focus was on exploratory processes related to matching the complexity of the environment. One of these is the article by Grootenboer and Edwards-Groves (Citation2020), in which the following finding is presented: ‘relatedly, our research has shown ways that middle leading is a communicative and responsive practice that facilitates active learning and participation in discussions about complex and often challenging educational issues. So, for the middle leader, negotiating and facilitating professional learning with teachers in schools, necessitates dialogic participation’ (p. 27). In two studies (n = 2), it was not possible to identify the organizational objectives being articulated.

RQ6: relation between middle-level leadership and decision-making processes

The analysis of the above table reveals diverse relationships between middle-level leadership and the decision-making processes in schools. Four studies (n = 4) indicated that middle leaders have the autonomy to make decisions in their respective departments or subject areas with reporting responsibilities to the schools’ senior management team, while 12 studies (n = 12) considered middle leaders as part of the decision-making team or part of the schools’ senior management team. However, two articles (n = 2) in the selected literature portray middle leaders as both having the autonomy to make decisions in their respective departments while also being part of the schools’ decision-making team or senior management. One of the arguments that emerged from the analysis was the questioning of the need for middle leaders’ involvement in the decision-making processes as part of the schools’ decision-making team or senior management. Considering the expanding workload of middle leaders in schools and the lack of structured training for the role, one study (n = 1) questioned the need for middle leaders’ involvement in the decision-making process. One study (n = 1) referenced middle leaders’ roles as facilitators of consensus within their respective departments or subject areas as part of the school decision making process, another article (n = 1) indicated that middle leaders are not part of the decision-making team, and in other articles (n = 11), the role of middle leaders in the decision-making process was not specified.

RQ7: central themes

Almost half the studies (n = 15) had an explicit objective of identifying the roles, practices and behaviors of middle leaders. The next most common theme was leadership development (n = 12). The influence, authority, impact and/or effect of middle leadership were investigated in five (n = 5) articles, while tensions and challenges were a central concern in four (n = 4). Other less frequently investigated topics were leadership skills (n = 2), career trajectories and transitions (n = 2) and responses to policy reform (n = 1).

Bibliographical analysis

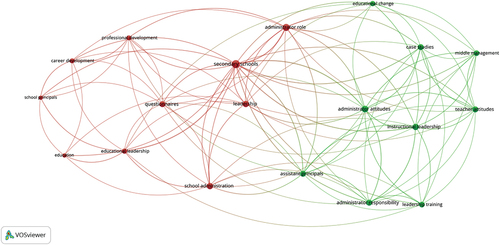

provides a visualization of the heterogeneity in the 32 selected articles. The analysis was performed using VOSviewer v.1.6.16 (Copyright © 2009–2020 Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2010), which is a software package for visualizing the connections between terms and creating and exploring maps based on network data. The program identified 21 keywords that met the three minimum appearance threshold. Then information regarding countries was removed as it was not a common practice among authors to include location among the keywords. It returned 19 items out of a total of 159 and divided them into two clusters with 101 links; the total link strength was 170. Link strength is a calculation of the proximity of keywords to each other. In other words, a high link strength indicates a closer network with structural proximity to other keywords.

depicts how different keywords are related to each other and thereby form connection clusters. Not surprisingly, the keyword ‘secondary schools’ (18 links) occupied a central position in this network and linked 19 keywords across all clusters. Cluster 1 (in red) shows that the terms ‘educational leadership’ (9 links), ‘schools principals’, ‘professional development’, ‘administrator role’ and ‘career development’ tended to be related to each other in the articles. Cluster 2 (in green) shows the centrality of ‘instructional leadership’ (12 links) and ‘administrator attitudes’ (13 links), which grouped terms such as ‘leadership training’ ‘middle management’, ‘educational change’, ‘teacher attitudes’ and ‘middle management’.

Discussion

The present study is a scoping review of literature on middle-level leadership in secondary schools. In this study, we wanted to capture the definitions of middle-level leadership, the theoretical perspectives, and the organizational objectives. We also examined the decision-making process and the central themes of middle-level leadership. The selected articles were drawn from sources worldwide and were not limited to any individual country. We had 32 articles in our final selection, which originated from eight different countries (RQ1). The studies were conducted in the UK, Asia, Africa, New Zealand and Australia. It is important to observe that none of the selected studies were conducted in the Americas or in other European countries. There may be various reasons for that, such as the choice of keywords used in the article searching phase. It is possible that studies conducted in such regions focused on middle-level leadership through a broader perspective rather than focusing on secondary schools, to which this review was limited. We regard this as a limitation of our study and highlight the need to research middle leadership in other regions.

The selected articles have used various research methods, tools, and data extraction techniques (RQ2). Most of the articles demonstrated a preference for the qualitative research design and study methods and used qualitative interviews, questionnaires, case studies, surveys and reports for assembling the data. Most articles in this study had an empirical character aimed at understanding middle leadership roles, behaviors and challenges through either quantitative or qualitative approaches. Nevertheless, understanding organizational complexity and behavioral contingencies related to middle-level leadership may require methodological developments in the field that involve grasping both structural dynamics and experiential accounts. For instance, a combination of social network analysis (Borgatti et al., Citation2009) with narrative analysis is a promising approach (Tsoukas & Hatch, Citation2001). Social network analysis can uncover the position of middle leaders, not in terms of formal hierarchies but in relation to informal and emergent everyday interactions with both internal and external agents. This spatial perspective could be further enriched by the time dimension of narrative analysis with its focus on personal experiences, non-linearity and temporal causality.

The difficulty in arriving at an all-encompassing definition of middle leadership in secondary schools or a definition broad enough to include the multiple and somewhat divergent roles of middle leaders in secondary school internationally is often highlighted by the differences in school contexts, school cultures, education systems, and the complex balancing acts of negotiating managerial responsibilities, leadership roles and collegiality within a school (RQ3). However, a consensus in the literature is the centrality of middle leadership in improving student performance, overall school improvements and the functioning of the school as a complex organization (Blandford, Citation1997; K. Leithwood et al., Citation2008; Lipscombe et al., Citation2021; Turner & Bolam, Citation1998). The shift from attributing organizational success to leadership strategies deployed by a single person with leadership and managerial authority to a more distributed model that focuses on the day-to-day processes both at individual and departmental levels and perceives group success as a collective effort (Au et al., Citation2003; Bento, Citation2011a) further highlights the importance of the role of middle leaders in achieving organizational success. The current review identifies middle leaders as individuals within a school who occupy positions such as subject heads or heads of departments or units, who may or may not have teaching responsibilities in addition to their leadership role.

An important factor in middle leadership is the ability to influence others (De Nobile, Citation2021). Most of the day-to-day challenges middle leaders face in schools are specific to their particular contexts. However, there are some challenges that are common across contexts, which include the lack of comprehensive formal training programs to prepare middle leaders for the complexities of the job, the challenge of negotiating both their managerial and leadership roles, and maintaining necessary collegial relationships, the increasing workload due to the fact that some middle leaders have teaching responsibilities in addition to their leadership roles, and the challenge of balancing whole-school interests and departmental needs and interests. In order for middle leaders to maintain their central role in the day-to-day processes within the school and navigate both context-specific challenges and common challenges associated with their role, their ability to exert influence on others, which is built on professional and social relationships and networks, is therefore paramount. It is through these forms of influence that leadership authority becomes effective, and it underpins the capacity of the middle leader to maintain good collegial relationships and carry out professional responsibilities. Therefore, middle leaders are individuals within a school occupying middle leadership positions, which are either formally named position or a position occupied as a result of staff’s personal interests or circumstances within the school, and through influence, which is based on professional and social relationships, facilitates, supports and lead a team, department or unit in a school.

The analysis of findings related to RQ4 highlights diversity in terms of theoretical perspectives, including conceptual tools that do not originally derive from the study of school leadership. This can be interpreted as a positive aspect of this field, as leadership itself is a complex phenomenon that may not be fully described by any single theory. The review of school leadership theories provided by Daniëls et al. (Citation2019) has indeed depicted an evolving field in which theories emerged in response to the perceived limitations of previous theories, highlighting different aspects but leaving other central questions unanswered. In this regard, further communication with the broad field of organizational theory may be a necessary development. Almost half of the articles either referred to or applied the theory of distributed leadership. This concept is an attempt to grasp complexity in organizational settings, as it addresses leadership as a process that takes place beyond formal hierarchical structures (K. A. Leithwood et al., Citation2009). However, distributed leadership may have limitations in understanding power relations and is often introduced in a way that becomes a top-down process of delegating tasks in educational settings rather than effectively dispersing leadership behaviors (Bento, Citation2011b).

The conceptual framework that informed the formulation of RQ5 offers a different perspective on complexity by highlighting processes and interactions from which system-level adaptation may emerge. From a complexity perspective, establishing the management/leadership distinction is less important than understanding the environmental contingencies around individuals in both formal and informal leadership positions as they relate to feedback loops that can either restrain or facilitate (variation) adaptation at the system level. Middle-level leadership behaviors and network structural positions may be conceptualized and researched under such terms. By doing so, researchers may then move the field in a new direction. The categorization of organizational objectives in RQ5 shows that in most studies (n = 21), it is possible to observe both organizational processes that facilitate (matching the complexity of the environment) and restrain variation (standard processes/outcomes). This idea needs to be further investigated empirically. Such meta-observation from this scoping review indicates that rather than being mutually exclusive, there is an organic co-existence in schools of different organizational processes that may enhance or limit each school’s capacity to match the complexity of its environment. As Sandaker et al. (Citation2014) claim, complex systems need to establish a fine balance between standards and behavioral variation. Investigating schools as complex systems requires understanding what this balance means in practice and what behavioral contingencies would impact the role of middle leaders.

The characterization of leadership approaches in literature, which includes decision-making processes (RQ6), can sometimes seem overly simplistic and somewhat naïve in the context of the day-to-day realities in schools. These include, among other things, the politics of decision making in schools and the place of middle leaders in the decision-making process. The analysis of the literature reveals that middle leaders play an important role in the distributed nature of the day-to-day decision-making processes within schools. They have dual roles within the school’s management structure, serving both as a voice for and representative of teaching staff as part of the management team, as well as being a representative of the management team in a department with responsibility to the school’s management structure. The capacity to navigate these dual allegiances underscores the importance of middle leadership in the successful running of a school and improving student performance. This review also shed light on the role of middle leaders in facilitating consensus within departments as part of a whole school decision-making process and in making operational decisions within departments.

Almost half of the studies (n = 15) analyzed in this review departed from an interest in identifying school middle leadership roles and behaviors (RQ7). Leadership development, middle-leadership impact and tensions were also among the investigated topics. These topics occupy a place in the context of complex responsive processes (Stacey, Citation2009) and interlocking behavioral contingencies, in which the behavior of an individual may constitute both antecedents and consequences of the behavior of other individuals. From a complex systems perspective, organizations can be understood in term of ongoing emergent themes in complex responsive processes. With this idea in mind, the behavioral and system approach directs future research in at least two empirical paths. The first concerns the network structural position of middle leaders and how this affects behavioral contingencies and learning opportunities at the individual level. Researchers may therefore inquire whether the increasing bureaucratization of the education sector in recent years has reduced middle-level leaders’ interactions with their surrounding environment, thereby reducing opportunities to learn from interactions with students and external stakeholders. Second, it is important to understand the role played by middle leaders in relation to informal and emergent webs of interaction, and its impact at the system level. A question that may be raised here concerns the role of middle leaders in schools as they relate to feedback loops (Krispin, Citation2017) that can be either positive or negative in relation to behavioral variation and the exploration of new possibilities. One of such behaviors is related to if and how leaders articulate emerging themes.

The network bibliographical analysis of keywords reveals the emergence of two main clusters of terms, each connected to main keywords: educational leadership (cluster 1), instructional leadership/administrator attitudes (cluster 2). Central themes identified in the analysis of RQ7 were expressed in the articles in the form of keywords such as ‘tensions’ and ‘challenges’ related to school-level leadership; however, these terms were not presented in the articles as keywords. However, it is still possible to identify possible trends. For instance, educational leadership seems to be linked to challenges that relate to professional and career development, while administrator responsibility and attitudes seem to be related to leadership training. This difference in terminology may be the result of local linguistic differences or indicate different tacit assumptions about the character of middle leaders either as ‘trained administrators’ (Cluster 2) or ‘leaders under development’ (Cluster 1). In Cluster 2, instructional leadership has a structurally central position, indicating a research interest in understanding the role of leaders in influencing teachers’ attitudes and promoting educational change. However, training is more emphasized in this cluster than development in a time perspective.

The main focus of this study is on secondary education, and it may therefore be difficult to point out how the results presented here differ from other educational levels. Secondary schools are usually larger institutions presenting a higher level of complexity than other school forms. It may be the case that middle-level leadership assume different forms either more bureaucratic or more as facilitators of adaptive changes in smaller schools. However, we hope that the conceptual framework that is presented here can also be applied in other settings providing the space for comparisons across different school levels.

Conclusion

The present scoping review contributes to research on middle-level leadership in schools by addressing different questions than previous reviews and suggesting a frame of reference of complexity to recommend developments in the field of school leadership. While this study narrowed the analysis to secondary school leadership, it was observed that this is a very diverse field in terms of definitions, theoretical perspectives, research methods and assumptions regarding organizational objectives and topics. The process of understanding complex organizational phenomena, such as school leadership, is always enriched by methodological and conceptual diversity. The different articles analyzed here highlight different aspects of organizational reality while leaving other questions unanswered. By offering a behavioral frame of reference for complexity, the goal here is not to provide a full meta-narrative of middle leadership in schools, but to recognize their structural and temporal positions in complex systems that are evolutionary, non-linear, historical and contextual. This perspective informs new paths for research on school leadership but can also provide information for the purposes of training and practice.

As pointed out here, middle-level leadership involves tensions and a complex interplay between behaviors that either facilitate or restrain organizational variation. A fine balance between these two organizational dimensions may assume different forms in different contexts, but the central idea is that middle leadership in schools should contribute to organizational adaptation to ever-changing environments. With this idea in mind, it is possible and necessary to think about leadership practices that facilitate the communication process and variation necessary to match the complexity of the environment. This means moving from purely control and supervisory roles to activities that both expose middle leaders themselves to different learning contingencies and facilitate communication about challenges and innovative processes in school settings. This certainly introduces an implication for middle leadership training, as it cannot be restricted to sets of replicable administrative tasks and regulations. Training programs should also provide opportunities to learn about the dynamics of continuity and change in schools. It is also important to promote reflection on how to facilitate open communication about challenges and innovative practices as experienced by teachers, other members of the school community and middle leaders themselves.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fabio Bento

Fabio Bento, Ph.D., is an associate professor at Oslo Metropolitan University. His research interests cover learning and change in different kinds of organizational settings.

Tayo Adenusi

Tayo Adenusi, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick, and his research interests are school ledership and pre-colonial education in Africa.

Puspa Khanal

Puspa Khanal, M.Ed., contributed to this article as a guest researcher at Oslo Metropolitan University. Her research interest is on education.

References

- Alvesson, M., & Sveningsson, S. (2003). Managers doing leadership: The extra-ordinarization of the mundane. Human Relations, 56(12), 1435–1459. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035612001

- Aouad, J., & Bento, F. (2020). A complexity perspective on parent–teacher collaboration in special education: Narratives from the field in Lebanon. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6010004

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Au, L., Wright, N., & Botton, C. (2003). Using a structural equation modelling approach (SEM) to examine leadership of heads of subject departments (HODs) as perceived by principals and vice-principals, heads of subject departments and teachers within “school based management” (SBM) secondary schools: Some evidence from Hong Kong. School Leadership & Management, 23(4), 481–498.

- Bassett, M. (2016). The role of middle leaders in New Zealand secondary schools: Expectations and challenges. Waikato Journal of Education, 21(1), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v21i1.194

- Bassett, M., & Robson, J. (2017). The two towers: The quest for appraisal and leadership development of “middle” leaders online. Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning, 21(2), 20–30.

- Bennett, N., Wise, C., Woods, P., & Harvey, J. (2003). Distributed leadership [A review of literature carried out for NCSL]. National College for School Leadership Website. http://forms.ncsl.org.uk/mediastore/image2/bennett-distributed-leadership-full.pdf

- Bennett, N., Woods, P., Wise, C., & Newton, W. (2007). Understandings of middle leadership in secondary schools: A review of empirical research. School Leadership & Management, 27(5), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701606137

- Bento, F. (2011a). The contribution of complexity theory to the study of departmental leadership in processes of organisational change in higher education. International Journal of Complexity in Leadership and Management, 1(3), 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJCLM.2011.042549

- Bento, F. (2011b). A discussion about power relations and the concept of distributed leadership in higher education institutions. The Open Education Journal, 4(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874920801104010017

- Bento, F., Giglio Bottino, A., Cerchiareto Pereira, F., Forastieri de Almeida, J., & Gomes Rodrigues, F. (2021). Resilience in higher education: A complex perspective to lecturers’ adaptive processes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 11(9), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090492

- Blandford, S. (1997). Resource management in schools. Effective and practical strategies for self-managing schools. Pitman.

- Borgatti, S. P., Mehra, A., Brass, D. J., & Labianca, G. (2009). Network analysis in the social sciences. Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, 323(5916), 892–895. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1165821

- Bryant, D. A. (2019). Conditions that support middle leaders’ work in organisational and system leadership: Hong Kong case studies. School Leadership & Management, 39(5), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2018.1489790

- Byrne, D., & Callaghan, G. (2013). Complexity theory and the social sciences: The state of the art. Routledge.

- Cardno, C., & Bassett, M. (2015). Multiple perspectives of leadership development for middle-level pedagogical leaders in New Zealand secondary schools. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 30(2), 30–38.

- Cardno, C., & Robson, J. (2016). Realising the value of performance appraisal for middle leaders in New Zealand secondary schools. Research in Educational Administration and Leadership, 1(2), 229–254. https://doi.org/10.30828/real/2016.2.3

- Crane, A., & De Nobile, J. (2014). Year coordinators as middle-leaders in independent girls’ schools: Their role and accountability. Leading & Managing, 20(1), 80–92.

- Cranston, N., Tromans, C., & Reugebrink, M. A. J. (2004). Forgotten leaders: What do we know about the deputy principalship in secondary schools? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 7(3), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120410001694531

- Daniëls, E., Hondeghem, A., & Dochy, F. (2019). A review on leadership and leadership development in educational settings. Educational Research Review, 27, 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.02.003

- Day, C., Sammons, P., & Gorgen, K. (2020). Successful school leadership. Education Development Trust. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED614324

- De Nobile, J. (2018, December). The “state of the art” of research into middle leadership in schools [Paper presentation]. Annual International Conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education, Sydney, Australia.

- De Nobile, J. (2021). Researching middle leadership in schools: The state of the art. International Studies in Educational Administration, 49(2), 3–27.

- Forde, C., Torrance, D., McMahon, M., & Mitchell, A. (2021). Middle leadership and social justice leadership in Scottish secondary schools: Harnessing the delphi method’s potential in a participatory action research process. International Studies in Educational Administration, 49(3), 103–121.

- Gibbs, G. (2002). Qualitative data analysis: Explorations with NVivo. Open University Press.

- Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(4), 423–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00120-0

- Grootenboer, P., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2020). Educational middle leading: A critical practice in school development. Leading & Managing, 26(1), 23–30.

- Gurr, D., & Drysdale, L. (2013). Middle‐level secondary school leaders: Potential, constraints and implications for leadership preparation and development. Journal of Educational Administration, 51(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231311291431

- Hallinger, P. (2003). Leading educational change: Reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Cambridge Journal of Education, 33(3), 329–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764032000122005

- Hallinger, P. (2005). Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4(3), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760500244793

- Hallinger, P. (2011). Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111116699

- Harvey, J. A., & Beauchamp, G. (2005). “What we’re doing, we do musically”: Leading and managing music in secondary schools. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 33(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143205048174

- Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., & Natemeyer, W. E. (1979). Situational leadership, perception, and the impact of power. Group & Organization Studies, 4(4), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/105960117900400404

- Horsley, T. (2019). Tips for improving the writing and reporting quality of systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 39(1), 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000241

- Irvine, P., & Brundrett, M. (2016). Middle leadership and its challenges: A case study in the secondary independent sector. Management in Education, 30(2), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020616643158

- James, C., & Hopkins, J. A. (2003). The leadership authority of educational “middle managers”: The case of subject leaders in secondary schools in Wales. International Studies in Educational Administration, 31(1), 50–64.

- Jarvis, A. (2008). Leadership lost: A case study in three selective secondary schools. Management in Education, 22(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020607085627

- Khumalo, J. B., & Van der Vyver, C. P. (2020). Critical skills for deputy principals in South African secondary schools. South African Journal of Education, 40(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n3a1836

- Khumalo, J. B., Van Der Westhuizen, P., Van Vuuren, H., & van der Vyver, C. P. (2017). The professional development needs analysis questionnaire for deputy principals. Africa Education Review, 14(2), 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2017.1294972

- Krispin, J. (2017). Positive feedback loops of metacontingencies: A new conceptualization of cultural-level selection. Behavior & Social Issues, 26(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v26i0.7397

- Leaf, A., & Odhiambo, G. (2017). The deputy principal instructional leadership role and professional learning: Perceptions of secondary principals, deputies and teachers. Journal of Educational Administration, 55(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-02-2016-0029

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership & Management, 28(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701800060

- Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (1999). Transformational school leadership effects: A replication. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 10(4), 451–479. https://doi.org/10.1076/sesi.10.4.451.3495

- Leithwood, K. A., Mascall, B., & Strauss, T. (Eds.). (2009). Distributed leadership according to the evidence. Routledge.

- Leithwood, K., & Sun, J. (2012). The nature and effects of transformational school leadership: A meta-analytic review of unpublished research. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(3), 387–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X11436268

- Li, S. C., Poon, A. Y., Lai, T. K., & Tam, S. T. (2021). Does middle leadership matter? Evidence from a study of system-wide reform on English language curriculum. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 24(2), 226–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1529823

- Lipscombe, K., Tindall-Ford, S., & Lamanna, J. (2021). School middle leadership: A systematic review. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 51(2), 270–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220983328

- Morrison, K. (2010). Complexity theory, school leadership and management: Questions for theory and practice. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(3), 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143209359711

- Mowles, C. (2021). Complexity: A key idea for business and society. Routledge.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Murphy, J., Elliott, S. N., Goldring, E., & Porter, A. C. (2007). Leadership for learning: A research-based model and taxonomy of behaviors. School Leadership & Management, 27(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701237420

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Perry, J. (2021). How are heads of English responding to policy changes in the English school system? English in Education, 55(4), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/04250494.2021.1873069

- Preiser, R. (2019). Identifying general trends and patterns in complex systems research: An overview of theoretical and practical implications. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 36(5), 706–714. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2619

- Ribbins, P. (2007). Middle leadership in schools in the UK: Improving design—A subject leader’s history. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 10(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120600934061

- Saleem, A., Aslam, S., Yin, H. B., & Rao, C. (2020). Principal leadership styles and teacher job performance: Viewpoint of middle management. Sustainability, 12(8), 3390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083390

- Sandaker, I. (2009). A selectionist perspective on systemic and behavioral change in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 29(3–4), 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608060903092128

- Sandaker, I., Andersen, B., & Ree, G. (2014). Byråkrati, variasjon og læring. Norsk Tidsskrift for Atferdsanalyse, 41(1), 33–43.

- Shore, K., & Walshaw, M. (2016). The characteristics and career trajectories of career assistant/deputy principals in New Zealand secondary schools. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 31(1/2), 121–134.

- Shore, K., & Walshaw, M. (2018). Assistant/Deputy principals: What are their perceptions of their role? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 21(3), 310–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2016.1218550

- Sibanda, L. (2018). Distributed leadership in three diverse public schools: Perceptions of deputy principals in Johannesburg. Issues in Educational Research, 28(3), 781–796.

- Siegenfeld, A. F., & Bar-Yam, Y. (2020). An introduction to complex systems science and its applications. Complexity, 2020, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6105872

- Spillane, J. (2006). Distributed leadership. Jossey-Bass.

- Stacey, R. D. (2007). Strategic management and organisational dynamics: The challenge of complexity to ways of thinking about organisations. Pearson Education.

- Stacey, R. D. (2009). Complexity and organizational reality: Uncertainty and the need to rethink management after the collapse of investment capitalism. Routledge.

- Szeto, E., Sin, K. F., & Volante, P. (2021). Middle teacher leadership practice for social justice: Young people’s career development in senior secondary education. International Studies in Educational Administration, 49(3), 82–102.

- Tay, H. Y., Tan, K. H. K., Deneen, C. C., Leong, W. S., Fulmer, G. W., & Brown, G. T. (2020). Middle leaders’ perceptions and actions on assessment: The technical, tactical and ethical. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1582016

- Thompson, G., & Glasø, L. (2015). Situational leadership theory: A test from three perspectives. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 35(1), 527–544. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-10-2013-0130

- Thorpe, A., & Bennett-Powell, G. (2014). The perceptions of secondary school middle leaders regarding their needs following a middle leadership development programme. Management in Education, 28(2), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020614529808

- Timperley, H. S. (2005). Distributed leadership: Developing theory from practice. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(4), 395–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270500038545

- Tlali, T., & Matete, N. (2021). The challenges faced by heads of departments in selected Lesotho high schools. School Leadership & Management, 41(3), 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1851672

- Townsend, T., Acker-Hocevar, M., Ballenger, J., & Place, A. W. (2013). Voices from the field: What have we learned about instructional leadership? Leadership and Policy in Schools, 12(1), 12–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2013.766349

- Tsoukas, H., & Hatch, M. J. (2001). Complex thinking, complex practice: The case for a narrative approach to organizational complexity. Human Relations, 54(8), 979–1013. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726701548001

- Turner, C., & Bolam, R. (1998). Analysing the role of the subject head of department in secondary schools in England and Wales: Towards a theoretical framework. School Leadership & Management, 18(3), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632439869565

- Turner, C., & Sykes, A. (2007). Researching the transition from middle leadership to senior leadership in secondary schools: Some emerging themes. Management in Education, 21(3), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020607079989

- Van Eck, N., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

- Yu, H., Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2002). The effects of transformational leadership on teachers’ commitment to change in Hong Kong. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(4), 368–389. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210433436

- Zhang, X., Wong, J. L., & Wang, X. (2021). How do the leadership strategies of middle leaders affect teachers’ learning in schools? A case study from China. Professional Development in Education, 48(3), 444–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1895284